Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 28

July 5, 2013

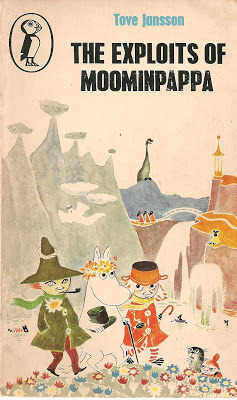

Magical Classics: 'The Exploits of Moomipappa' by Tove Janssen

Catherine Butler enjoys the wisdom, joy and occasional melancholy of the gentle Moomins

Catherine Butler enjoys the wisdom, joy and occasional melancholy of the gentle MoominsThe Exploits of Moominpappa (1952)

I came rather late to the Moomins, reading Tove Jansson’s books for the first time only when my own children were small, but I have the zealotry of the convert. For those who have not come across them, a quick way to convey something of their quality might be “Winnie-the-Pooh as written by Jean-Paul Sartre”. Like Pooh, Moomintroll and his friends – who include a wide variety of creatures, not just the hippo-like Moomins themselves – inhabit a rural arcadia of sorts. Their adventures are amusing and apparently inconsequential, although those that take place in Moominvalley tend to be more dramatic and (on occasion) magical than those in the Hundred Aker Wood. The Moomins are given to philosophizing on family, freedom, happiness, friendship and other important topics, but this is an arcadia that can show a bleaker face than Milne’s, one subject not only to floods and snow but to comet strikes, in which depression (not just Eeyore-ish lugubriousness) is a felt presence, and in which even death casts a bony shadow. If you are familiar with Jansson’s writing for adults, such as The Summer Book, you will find the same poetic, lapidary wisdom in Moominvalley, as well as the same setting on the Gulf of Finland, where midsummer days last round the clock and midwinter barely sees the sun.

'The birds, the worms, the tree-spirits and the mousewives...'

'The birds, the worms, the tree-spirits and the mousewives...'Most Moomin fans have their favourite character. For many it is Snufkin – the placid and self-sufficient friend of young Moomintroll, who likes to spend the summers with his friends in Moominvalley but is also happy in his own company, and roused to anger only by petty displays of authority (park keepers and Keep Out signs being particular bugbears). For others it will be the minute but indomitable Little My, an atom of energetic, unsentimental feistiness. I too love Snufkin, and Littly My hangs (in plush form) from my rear-view mirror, but I also have a particular fondness for Moominpappa, the top-hatted patriarch of the Moomin family. Like several middle-aged males in children’s literature (think Bilbo Baggins, think Ratty with the Old Sea Rat) Moominpappa is perpetually torn between the instinct for domesticity (he cannot settle anywhere long without building a Moominhouse) and the call to the open sea and adventure, epitomized in his desire to join the mysterious and mute Hattifatteners in their endless ocean journeying.

In the early Moomin books Moominpappa watches benignly over the family’s adventures, leaving most of the work to the preternaturally accommodating Moominmamma; later, in Moominpappa at Sea, he succumbs to depression and something of a mid-life crisis. The Exploits of Moominpappa* (first published 1952) sits somewhere between these two phases. Set in high summer, is a retrospective book that nevertheless shows Moominpappa in festive mood, with an ending (I will not give it away) that absurdly and triumphantly redeems the time of his youth. Unlike the other Moomin books this is told largely in the first person, with Moominpappa sitting down to write his life-story up to the moment of his fateful meeting with Moominmamma, and stopping occasionally to read chapters to his son Moomintroll, Snufkin and their friend, the anxious and querulous Sniff.

As a narrator, Moominpappa has something of Boswell’s bumptiousness and hunger for praise, combined with the blithe lack of self-awareness of an Oswald Bastable. We follow him as he escapes from the orphanage where he has been raised by a humourless Hemulen (aren’t they all?), and watch as he gathers a collection of friends as eccentric as himself, including practical, taciturn Hodgkins; Hodgkins’ flighty nephew, the button-collecting Muddler; and the free-spirited Joxter. Together they travel the ocean on a houseboat which (being both a house and a boat) combines Moominpappa’s contrary desires in one. Their journey takes in adventures with snout-devouring Niblungs, the icy and fearsome Groke, the gigantic but slightly less fearsome Edward the Booble, a Hemulen Aunt with a passion for multiplication contests, an Autocrat addicted to practical jokes, and a domesticated ghost who delights in talk of bones and dire revenges.

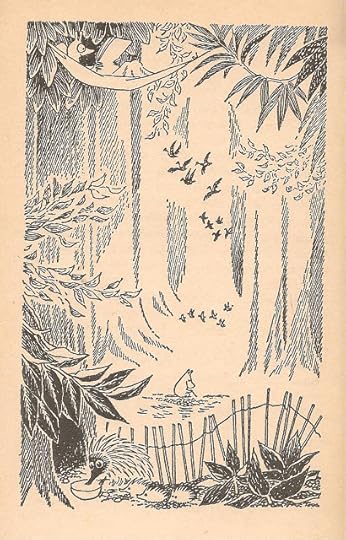

'A million billion fishes came swimming from everywhere...'

'A million billion fishes came swimming from everywhere...'Exploits is not the place to begin with the Moomin books: for that I would recommend Moominsummer Madness or Finn Family Moomintroll, where you will be introduced to the major characters and get a more general feeling for Jansson’s world. However, if you prefer the Odysseyto the Iliad, or if The Voyage of the Dawn Treader is your favourite Narnia book, then this journey too will hold a special place in your heart, and I can only echo what Moominpappa writes in his foreword:

I believe many of my readers will thoughtfully lift their snout from the pages of this book every once in a whi

* There is a later version of this book called Moominpappa’s Memoirs, which differs from Exploits in some small but – for Jansson completists – significant respects. Both, however, are well worth reading!

Catherine Butler is the author of some half dozen fantasy novels for children and young adults, as well as being Associate Professor of English Literature at the University of the West of England, where she specializes in children's literature. She has lived in Bristol since 1990, has two children (one grown up and one well on the way), and is currently trying to learn the piano and Japanese, though not in combination. Her edited collection of spooky winter stories, Twisted Winter , will be published by A&C Black in September 2013.

Picture credits: All artwork by Tove Jansson

Published on July 05, 2013 01:40

June 28, 2013

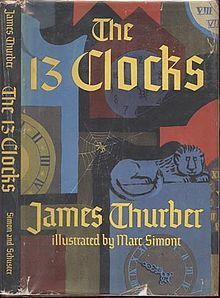

Magical Classic: 'The Thirteen Clocks' by James Thurber

Guggle and Zatch: An Appreciation, by Jane Yolen

If those words—guggle and zatch—resonate for you, I don’t have to spell out the delicious power of one of my favorite (short) magical books. You already know which one I mean. For the rest of you, hie yourself down to your nearest second-hand book store and seek out James Thurber’s wonderful The Thirteen Clocks. Or find the fairly newly reprinted version (which I haven’t seen but have had reliably reported as containing the delightful original illustrations by Marc Simont, not the later ones by the usually delightful Ronald Searle, but he didn’t get the book the way Simont did.) This addition has an added bonus—an appreciative introduction by the ever-ready battery known as Neil Gaiman. You can thank me later. It is a smart and sophisticated little book full of lovely turns of phrases, complex and enjoyable word plays, and bits that worm their way into your ear and vocabulary forever. Like guggle and zatch. (Well, Thurber did write for the New Yorker and drink with the tony lit crowd in New York after all, or rather he drank them all under the table, and my father was one of the designated bring-him-home-on-his-shield-or-in-a-taxi guys.) And the magical creatures are all wonderfully scary (like the Todal) or deliciously evil (like the wicked duke), or decidedly enigmatic (like the Golux), or sadly mysterious (like Hagga), or strangely bi-loyal (like Hark). The story feels like an old-fashioned fairy tale with a decided kink. The princess Saralinda in danger, her rescuer the prince-turned minstrel in even more danger. Yet nothing is what we think it is and everything happens exactly as we want it to, even if we don’t realize it at the beginning. And the prose might as well be a long poem but isn’t, because it has this complex meter and internal rhyme and play on words and all that good stuff. Two Christmases ago, I gave a rubbed and pre-loved copy to my then eight-year-old twin granddaughters and promptly sat down and read them the first two chapters. (We love to read aloud.) And they asked for one more chapter. And then one more. And I fell in love with the book all over again as they were doing for the first time. We sat reading in the fading Charleston light and finished just as dinner was on the table. We would have missed dinner, all three of us, just to hear the rest of the book. But we’d timed it perfectly. As does Thurber, all the way through this perfect (and picture perfect as well, thanks to Simont) magical book.

Warm thanks to Jane Yolen, who needs very little introduction from me. Her many books (over 300 to date) are on shelves all over the world, and range from picture books for little children, to magical adventures and fairytales for middle-graders, to teenage and adult fantasies, to academic essays. Her awards include the Caldecott Medal, two Nebula Awards, the World Fantasy Award, three Mythopoeic Awards, the Jewish Book Award, and the World Fantasy Association Lifetime Achievement Award. Six colleges and universities have given her honorary doctorates, and last year she was the first woman to deliver the prestigious Andrew Lang lecture at the University of St Andrews, adding to a rollcall of many notable names including those of John Buchan and JRR Tolkien.

Picture credit: Marc Simont artist: cover of 'The Thirteen Clocks' by James Thurber, Simon and Schuster 1950: sourced from Wikipedia

Published on June 28, 2013 00:03

June 21, 2013

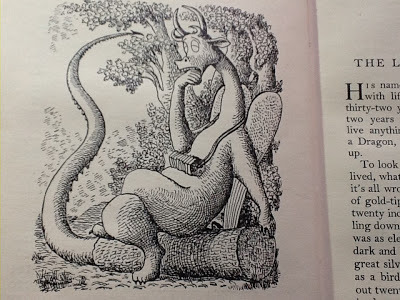

Magical Classics: 'The Last of the Dragons' by A. de Quincey

Lucy Coats and the mysterious A. de Quincey's vegetarian dragon:

In Book IX of the History of Animals, Aristotle states:

"When the draco has eaten much fruit, it seeks the juice of the bitter lettuce."

Fruit? Lettuce? Dragons? Some mistake, surely, O Venerable Greek Philosopher? Well no. Not if you're A. de Quincey, author of the favourite fantasy of my childhood - The Last of the Dragons.

Perhaps you may never have thought of a dragon as a vegetarian sort of creature. Perhaps you have always seen it as a creature of blood and gore, rending sacrificed virgin princesses from limb to limb and crunching armoured knights like lobsters. I suppose I thought like that too until I met De Quincey's Ajax.

This is how de Quincey describes him:

"He was as handsome a creature as ever lived, what with his soft and satiny dark-green skin...and the row of gold-tipped spines that ran down his back.... On his head were two pairs of horns, one shorter and the other longer, like a snail's; but they were for adornment and not for fighting or anything of that sort. His teeth were beautifully regular, and neither too large nor too small. He had a most engaging smile."

In addition to all this handsomeness, Ajax can blow double smoke rings, tell a great story, draw, play the concertina (with extra twiddles because of his six fingers and two thumbs), sniff out treasure and fly "as fast as a Spitfire". He is also, as mentioned above, a vegetarian, liking grass, leaves, fruit, nuts and, most especially, mushrooms and truffles. However, he has a problem. Ajax is the last of his kind - and he's dead bored of his own company, so decides to find a job with "the next most intelligent creatures to Dragons" - ie us humans, with varying results.

The tale which follows is as entrancing to me now as it was when I was eight. I've just read it again for about the fiftieth time in order to try and work out what it is about this particular fantasy which has drawn me in and held me for all those decades. Is it the grumpy and ghastly Fairy Frowniface, with her wand "made for magical purposes by King Solomon himself'? Is it the mean, green-eyed slinking stinker of a cat, Mrs Maul? Is it the polite would-be dragon-slayer, Prince George of Hesperia, with his insouciant air of bravery, and rat-generalling skills? Is it villainous, black-bearded Baron Terrible and his rough and tumble henchmen, who repent after being turned into an embarrassed frog and a squiggle of tadpoles? Or is it Ajax himself - the dragon from Venus whose King is the legendary Phoenix?

It's all of these and more. While De Quincey's authorial voice has a delightfully old-fashioned tone akin to E. Nesbit and E. Goudge, it's also surprisingly modern in attitude - I think there are few books from that period (1947) which are so respectful of Islamic traditions, or even mention them. But apart from the great storytelling and characterisation, the thing I like best is the rich and uniquely satisfying descriptive prose, which then and now satisfies my inner reader's desire to know what things look like, where they come from, and how they got there.

Who A.de Quincey was is a mystery. He (or she) only wrote one other book - The Little Half-Giant - which I have just managed to track down a copy of on AbeBooks. The Last of the Dragons was illustrated by Brian Robb, who lectured at the Chelsea College of Art, (inspiring a generation of fantastic illustrators such as Quentin Blake), and later took over from Edward Ardizzone as head of illustration at the Royal College of Art. Blake says of him: "Robb's work had a humane, wry, almost teasing character that makes me wish he had set his hand to more children's books than he did" and I would agree with that. The slightly fuzzy but endearing black-and-white illustrations are a big part of the book's charm for me. But of this particular de Quincey's life and times I can find no trace, despite it being a literary name of some renown in a sphere other than children's books. If anyone knows more about A. de Quincey, I'd love to hear from you. We fans of Ajax are few and far between, but devoted to the last. If only Hamish Hamilton would bring him back into print....

Lucy Coats is reads, writes and blogs magic, myth and fantasy – as you might expect from someone who remarks: ‘I was born in a shrubbery nearly half a century ago and have been looking for fairies in the trees ever since.’ She has written over 25 titles for children, including her Greek Beasts and Heroes series, published by Orion, Hootcat Hill, a fantasy for older children, and her new picturebook, Bear's Best Friend has recently featured on CBeebies Bedtime Stories. Lucy's website is http://www.lucycoats.com/

and she currently blogs at http://lucycoats.tumblr.com/

Published on June 21, 2013 00:35

June 14, 2013

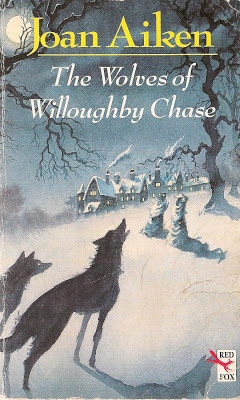

Magical Classics: 'The Wolves of Willoughby Chase' by Joan Aiken

Katy Moran explores Joan Aiken's disturbing yet entrancing classic

A grand house, a pack of hungry wolves and two brave and resourceful girls – this is the opening to one of the most magnificent children’s books ever written: a tapestry of skulduggery and deception, petty forgery and outrageous bravery, woven together with shining golden threads of thought-provoking fantasy. It’s also a tale of innocence and experience that William Blake would have been proud of.

Within seconds of the first meeting between Bonnie Green and her terrifying new governess, it is clear that Miss Slighcarp intends to rule Willoughby Chase with an iron rod. Bonnie’s days of ice-skating in the frozen park and bouncing on the window-seat cushions in a cosy, firelit nursery are unmistakeably numbered. It is no surprise, then, that Bonnie dreads the moment her parents will leave home to embark on their ocean voyage, but she must take comfort in the hope that a friendlier climate might improve her mama’s health, and in the knowledge that soon her cousin will soon arrive from London to keep her company.

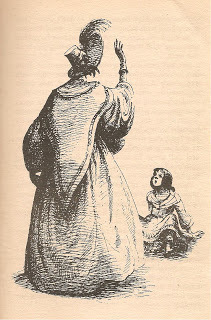

Miss Slighcarp

Miss SlighcarpEnsconced in the chilly carriage of a train hurtling north, ever closer to Willoughby Chase, Sylvia Green has problems of her own as – horror of horrors – she is joined in the carriage by a fellow passenger, the alarmingly genial and kind Mr Grimshaw. His very presence means that genteel Sylvia cannot even nibble one of the hard, tiny bread rolls her dear Aunt Jane packed for the journey, and propriety certainly forbids accepting one of the oozing violet cream pastries Mr Grimshaw is so eager to press upon her. But outside the train carriage a fiercer danger stalks the snow and ice, for the wolves are baying with hunger and desperate enough to attack, and it quickly becomes clear that Mr Grimshaw is not quite what he seems. Joan Aiken is tremendously skilled at pinpointing the very real fears of children: Sylvia’s anguish at having to share her train carriage with a jovial and chatty stranger struck a deep chord with me when I was a child, and was a more frightening notion than Miss Slighcarp and the wolves combined. Mr Grimshaw’s dripping, sugary cakes were especially disturbing – so tempting, and yet every child knows never to accept food from strangers. Oddly, I didn’t find the wolves attacking the carriage scary at all.

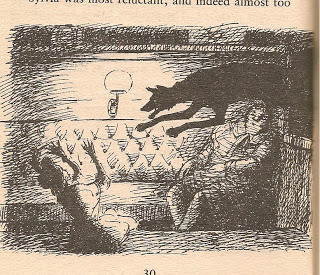

The wolf attacks

The wolf attacksThe Wolves of Willoughby Chase is not only a classic, it represents a new beginning, and I think it may contain one of the first examples of steampunk in children’s literature. I first discovered the novel when I was about ten or eleven years old, but I had no idea that I was encountering the first flowering of a genre that was to rule children’s fiction in later years. I do remember being fascinated by a matter-of-fact foreword explaining that the action takes place in a Jacobean period of history that “never happened”, with a fictional King James III on the throne, and a newly opened Channel Tunnel the unintended conduit of hungry wolf-packs from mainland Europe. The real Channel Tunnel was still under construction when I first read the novel, and I still remember trying to picture what it would be like filled with horses and carriages. In fact, one of the first things I loved about The Wolves of Willoughy Chase is the way Joan Aiken renders the real world just a little bit strange and unusual. The grandeur and opulence of Bonnie’s home is already an exciting contrast to the genteel poverty of the life Sylvia has just left behind, as well as the more humdrum world of most children reading the book, but of course it doesn’t end there. There are wolves. This just doesn’t feel like fantasy of the same ilk as the wonderful novels by Tamora Pierce that I gobbled each week at the library, because of course it’s not. In truth, Aiken’s flights of fantasy are perhaps more strictly magic realism – they are always used to make a point, to escalate a moment of fear. The wolves of Willoughby Chase come to embody the danger gathering around Bonnie and Sylvia as Miss Slighcarp destroys their world piecemeal – it’s as if the wolves and the steampunk Channel Tunnel that allow them to exist in the novel actually represent the girls’ loss of innocence, and perhaps also a loss of innocence on a wider, social level as the action moves from the rural grandeur of Willoughby Chase to the harsh, dark world of industrial Blastburn.

Joan Aiken’s use of fantasy and steampunk is a lesson in kind for any author – she uses these elements with such obvious pleasure, but the wolves and the other touches of fantasy don’t exist purely for their own sake – they lend wings to the story as a whole, intensifying emotion and crystallising moments of tension with the kind of authorial magic that is utterly compelling, and which only emerges once or twice in a generation. I’m delighted to have made the discovery that The Wolves of Willoughby Chase was just the first in an entire series. I only wish I had known the rest of the books as a child – still trailing clouds of glory, as William Wordsworth might have said, more or less, anyway. It really is no exaggeration to say that I would give this book to any child.

Katy Moran is the author of several YA historical fantasies including Bloodline and Bloodline Rising , set in Britain and Constantinople in the Dark Ages, and Spirit Hunter , a tale of danger and forbidden love along the ancient and mysterious Silk Road. Katy has also published Dangerous To Know, a modern love story for the festival-going generation. Her latest YA novel Hidden Among Us (Walker 2013) is a compelling faerie fantasy set in contemporary Britain, and I can highly recommend it.Picture credits: cover and artwork from 'The Wolves of Willoughby Chase', copyright Pat Marriot 1962.

Published on June 14, 2013 01:02

June 7, 2013

Magical Classics: "The Three Royal Monkeys" by Walter de la Mare

As far as I'm aware, this is Walter de la Mare’s only full length book for children. Published in 1910, its original title ‘The Three Mullar-Mulgars’ was - presumably - so unhelpfully baffling even by early twentieth century standards, that by the time I read it in the 1960’s, it had been given a new and more explanatory title. Even so, I think it’s not particularly well known. Which is a pity. As a child I was entranced by it , and I still think it’s wonderful.

To explain the impression it made on me, here is a bit of personal history. I began seriously writing stories when I was ten. I’d read all the Seven Chronicles of Narnia, and I knew there wouldn't be an eighth. (‘The Last Battle’ was such a betrayal. The end of Narnia? Noooooooooo! And I wasn’t fooled by all that ‘heaven is Narnia, but better’ stuff, either. There was no better place than Narnia.)

So my first 'book' was called ‘Tales of Narnia’: fan-fic before the term was invented. My second – a full-length effort – was an historical novel which owed something to those of Mary Renault. Then, from age 13 to 15 or so, I wrote another ‘book’ of short stories which I called ‘Mixed Magic’ (it really was mixed; some quite good, some terrible), derived mainly from two more beloved writers, E. Nesbit and Elizabeth Goudge. Round about age 15 to16 my fourth m/s was heavily influenced by early Alan Garner (children encounter mysterious stranger in dripping English woods, pursued by minions of the triple Moon Goddess; standing stones and indifferent golden-faced elves figure largely…) – but my fifth, written in my late teens and early twenties, by which time I was beginning to find my own voice, owes a great deal to the enchantment I found in de la Mare’s ‘The Three Royal Monkeys’. I called it 'The Magic Forest' (and went on to write a sixth full-length m/s, also unpublished, before eventually getting myself into print with ‘Troll Fell. And I enjoyed every minute of all of it.)

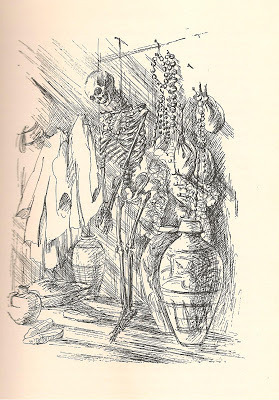

The Portingal in his hut

The Portingal in his hutThe quality I found in ‘The Three Royal Monkeys’ which I was trying to reproduce in my fifth opus, was a rich, exotic beauty, tinged with pathos and melancholy, relieved by sure touches of comedy. This is how it opens:

On the borders of the Forest of Munza-Mulgar lived once an old grey Fruit Monkey of the name of Mutta-Matutta. She had three sons, the eldest Thumma, the next Thimbulla, and the youngest, who was a Nizza-neela, Ummanodda. And they called each other for short, Thumb, Thimble and Nod. The rickety, tumble-down old wooden hut in which they lived had been built 319 Munza years before by a traveller, a Portugall or Portingal, lost in the forest 22,997 leagues from home.

After the Portingal dies, a Mulgar or monkey comes to live in the hut, where he finds:

... all manner of strange and precious stuff half buried – pots for Subbub; pestles and basins for Manaka-cake, etc.; three bags of great beads, clear, blue and emerald; a rusty musket; nine ephelantoes’ tusks; a bag of Margarita stones; and many other thing, besides cloth and spider-silk and dried-up fruits and fishes. He made his dwelling there and died there. This Mulgar, Zebbah, was Mutta-Matutta’s great-great-great grandfather. Dead and gone were all.

But one day a royal traveller arrives, Seelem, ‘own brother to Assasimmon, Prince of the Valley of Tishnar’, accompanied by his servant. Seelem becomes Mutta-Matutta’s husband, but after thirteen years he leaves her, returning to his heritage in the beautiful valleys of Tishnar. Seven years later, on her deathbed, she urges her sons to follow their father.

It was hot and gloomy in the tangled little hut, lit only by the violet of the dying afterglow. And when she had rested a little while to recover her breath she told them … they were, as best they could, bravely to follow after him. In time they would perhaps reach the Valleys of Tishnar, and their uncle, Prince Assasimmon, would welcome them.

“His country lies beyond and beyond,” she said, “forest and river, forest, swamp and river, the mountains of Arrakkaboa – leagues, leagues away.” And as she paused, a feeble wind sighed through the open window, stirring the dangling bones of the Portingal, so that with their faint clicking, they too, seemed to echo, “leagues, leagues away.”

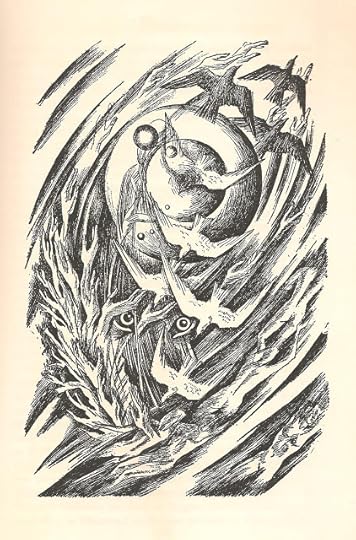

The rest of the book follows the brothers’ difficult and magical journey. Nod, the youngest, is ‘a Nizza-Neela, and has magic in him’; and he is the possessor of the marvellous Wonder-Stone, which if rubbed when they are in great danger, will bring the aid of Tishnar to them.

Nod and the Wonder-Stone

Nod and the Wonder-StoneAnd who is Tishnar? There are many mysteries in this book, and she is one of them, with a whole chapter at the end dedicated to her. She is ‘the Beautiful One of the Mountains’; ‘wind and stars, the sea and the endless unknown’. She it is who instils in the heart a sense of longing; she brings peace and dreams and maybe, in her shadow form, death.

At any rate, the brothers’ journey is precipitated when Nod accidentally sets fire to the hut. In the fairytale tradition of the foolish yet wise younger brother, he makes many mistakes, but he is also the one who saves his brothers from the many predicaments they find themselves in, as they trek through the deep moonlit snow of the winter forest – escaping the flesh-eating Minnimuls, tricking the terrifying hunting-cat Immanâla, riding striped Zevveras, the Little Horses of Tishnar, finding friends and losing one another, quarrelling and making up.

It’s a deeply serious quest, an epic journey with no hint of tongue in cheek despite the fact that the protagonists are monkeys. Delicately, de la Mare explores the transience of beauty, the poignancy of loss, the immanence of death: and his characters blaze all the more brightly in their course across the impermanent world. There’s a lovely chapter in which Nod meets, and loses his heart to a beautiful Water Midden (water maiden) to whom he entrusts his Wonder-Stone. Here is the song he overhears her singing ‘in the dark green dusk’ beside a waterfall:

Bubble, Bubble,Swim to see Oh, how beautifulI be,

Bubble, Bubble,Swim to see Oh, how beautifulI be,Fishes, fishes,Finned and fine,What’s your goldCompared with mine?

Why, then, hasWise Tishnar madeOne so lovely,One so sad?

Lone am I,And can but makeA little song,For singing’s sake.

If you haven’t read this book before, and if you’re looking for something at least as good as The Hobbit, this is for you.

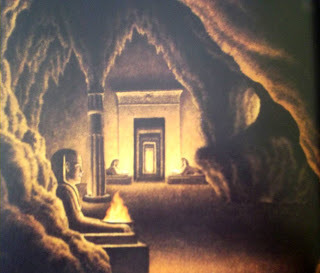

Tishnar

TishnarPicture credits: all illustrations by Mildred E Eldridge for 'The Three Royal Monkeys'

Published on June 07, 2013 00:56

May 31, 2013

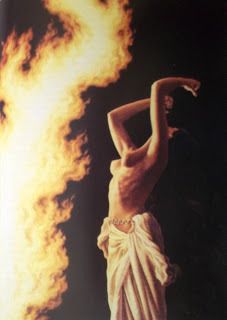

Magical Classics: SHE, by H Rider Haggard

Katherine Roberts on the eternal fascination of She

I first read this book when I was about 10 or 11, after discovering it on my mum’s secret bookshelf. I’d outgrown pony stories and wanted something a bit more exciting. I was halfway through the story by the time Mum found out I had the book, by which time she was too late to stop me from reading the rest… I was too wrapped up in the fascinating tale of “She Who Must Be Obeyed” and had fallen in love with H Rider Haggard’s rather-too-old-for-me but still heart-throbbingly handsome hero Leo, believed by She to be the reincarnation of her long dead ancient Egyptian lover.

“It’s a bit of a horror story,” warned my mum. “But a good adventure, I suppose.”

I’d already worked that out for myself! The golden Leo and his Uncle Holly, accompanied by their faithful manservant Job, had already left boring old England for Africa, where they had been shipwrecked, shot big game (the story was first published in 1887, when these things were less politically incorrect), been kidnapped by the People Who Place Pots on the Heads of Strangers, and taken to the lost land of Kôr, where they meet the enigmatically veiled Queen Ayesha, known to the local tribes only as “She Who Must Be Obeyed”. Along the way, our hero Leo nearly drowns, is rescued from the jaws of a giant crocodile, gets eaten alive by mosquitoes, is wounded in a fight, and gains a tribal wife called Ustane… and that’s only a quarter of the way through the story!

The early chapters back in England promised even greater magic, according to a script translated from a shard of an ancient Greek vase:“Then She did take us, and lead us by terrible ways, by means of dark magic, to where a great pit is, and showed to us the rolling Pillar of Life that dies not… and there did She stand in the flames and come forth unharmed, and yet more beautiful.”And also it seems, immortal, although her attempt to persuade her beloved Kallikrates to join her in the fire fails, since he is in love with another woman. So Ayesha kills him in a fit of passion, after which she is doomed to live alone for two thousand years until she finds his reincarnation in the flesh… none other than our young hero, Leo!

How could I not read on?

Ayesha keeps herself veiled because she fears the effect her beauty might have on the mortal men she rules. She unveils only in private, when she curses the mortal woman who doomed her to two thousand years of loneliness:“Curse her, daughter of the Nile, because of her beauty…Curse her, because her magic has prevailed against mine…Curse her, because she held my beloved from me…”This turns her into a proper storybook villainess, which she soon demonstrates by sentencing the People Who Place Pots on the Heads of Strangers to death for attempting to cook and eat Leo and his friends, instead of bringing them safely to her as she ordered. She also punishes Ustane when the girl tries to nurse Leo after he falls sick, at first merely scaring the girl by turning her hair white, but eventually seeing her as a dangerous rival for his love. Poor Ustane cannot fight Ayesha’s magic and is eventually killed by her in fit of temper. (I cried at that part, and kept expecting Ustane to come back to life at some point, but of course this is an adult story so she didn’t – though I later wrote my own happy ending, where Ustane gets to crawl into the Pillars of Life and comes back to fall into Leo’s arms!)

Freed from Ustane’s love, Leo is at the mercy of Ayesha, until the final test when she asks him to step into the fire and join her in immortality. Leo hesitates, and so Ayesha (thinking to reassure him the flames will not harm him) steps into the fire for the second time… with horrific results.

The spectacle of the fabulously beautiful queen turning into an ancient crone in the space of a few heartbeats must be the “horror” my mum referred to – as a girl, I shuddered a bit, but did not really have much sympathy for the cruel Ayesha, who had killed the innocent Ustane. Now I can see more clearly the tragedy of the ancient queen’s long, loveless life, and her desire to hold on to her power to the bitter end.

As they journey to the secret cavern that contains the Pillars of Life, she explains her plan to accompany Holly and Leo back to England and rule there, brushing aside their objections that England already has a Queen and its own laws that do not include placing pots on the heads of strangers and eating them:“The Law! Canst thou not understand, O Holly, that I am above the law? Does the wind bend to the mountain, or the mountain to the wind?”But like many powerful rulers, she takes this a step too far and compares herself to the goddess of Kor, called Truth:“There is no man born of woman who may draw my veil and live… By Death only can thy veil be drawn, O Truth!”

The truth in Ayesha’s case is a harsh one, as her words turn out to be prophetic. So the villainess expires in her own fire, and the hero survives to fight another day. And, like all the best horror stories, with her last breath Ayesha promises to come again, leaving the way open for the sequels “The Return of She” and “She and Allan”.

SHE, besides being a bit of a horror story and a good adventure, is packed full of deeper meanings that can be found in all the best fantasy. Aged 11, many of them passed over my head – I particularly remember skipping some of the early chapters, when the men are discussing the origins of the clues that send them on their quest, impatient to get on with the adventure! But I’m pretty sure they lodged somewhere in my subconscious, to emerge many years later in my own stories in the form of quests for immortality, such as Alexander the Great’s journey to the edge of the known world in search of the water of life to save his horse, and Rhianna’s quest to bring her father King Arthur back from the dead with the legendary Grail of Stars. Maybe proving that the most powerful themes live on in fantasy fiction for all ages, which makes our genre a lot more adult than many non-fantasy readers believe it to be.

Many thanks to Katherine Langrish for inspiring me to revisit this great story! If you haven’t read any of H Rider Haggard’s work yet, then it’s well worth seeking out SHE as a starting point. And if you’re already a fan, the H Rider Haggard omnibus edition containing all of his 60 novels and short stories is now available as an ebook… one of the first downloads on my Kindle!

***Katherine Roberts gained a first class degree in mathematics from Bath University, and went on to work as a mathematician, computer programmer, racehorse groom and farm labourer - before her first novel, ‘Song Quest’, won the Branford Boase Award in 1999. Since then, she has written many works of fantasy and historical fantasy for young readers. 'Grail of Stars', the fourth book of The Pendragon Legacy, a series about Rhianna Pendragon, King Arthur's daughter, will be published by Templar, October 2013. Find out more at Katherine's website, www.katherineroberts.co.uk , visit her blog http://reclusivemuse.blogspot.comor follow her on Twitter: @AuthorKatherine

Picture credits: All artwork by Michael Embden, from the 1981 edition of “She” published by Dragon’s Dream. Michael Embden's website is http://www.michaelembden.com

Published on May 31, 2013 00:43

May 24, 2013

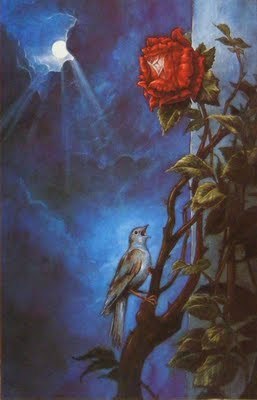

Magical Classics: 'The Nightingale and the Rose' by Oscar Wilde

'The Nightingale and the Rose' by PJ Lynch

'The Nightingale and the Rose' by PJ LynchMary Hoffman writes about a poignant tale of love and sacrifice:

My copy of The Works of Oscar Wilde (Collins 1948, 1960 edition) has my name and “Newnham” written on the flyleaf so I must have had it at university. But we never studied Wilde on my Eng. Lit. course and I know I fell in love with him while still at school so I think I think I had it then and must have put my stamp on it when I left home.

It would have been typical of me to pack my Oscar Wilde when heading off for the adventure of university because it had by then become a bit of a comfort blanket, the one book I would have saved in a fire. The plays, including Salome, for which Aubrey Beardsley did those splendid illustrations, The Picture of Dorian Grey, the fabulous Portrait of Mr W. H. and above all the Fairy Tales, were my absolute ideal of what writing should be.

Everyone knows The Happy Prince and The Selfish Giant, many have heard of The Canterville Ghost and Lord Savile’s Crime but I have never seen anything written about The Nightingale and the Rose.

It’s a short story – no more than four and a half pages in my Complete Works – and takes the form of a parable:

A Student is madly in love with the daughter of a professor, who has agreed to dance with him at the Prince’s Ball if he brings her a red rose. But all the roses in the Student’s garden are white or yellow; the only red rose is frostbitten and will bear no flowers that summer.. The Nightingale overhears the Student’s plaint.

“Here at last is a true lover,” said the Nightingale. “Night after night have I sung of him, though I knew him not: night after night have I told his story to the stars and now I see him. His hair is dark as the hyacinth-blossom, and his lips are as red as the rose of his desire; but passion has made his face like pale ivory, and sorrow has set her seal upon his brow.”

The bird decides to help him and, after seeking easier ways, chooses the bitter path of sacrifice. The red rose tree tells her that she must construct a blossom out of her music by moonlight, through singing with her breast against a thorn. The thorn will pierce her heart and her life’s blood flow into the rose-tree and produce one perfect flower.

“Death is a great price to pay for a red rose,” cried the Nightingale, “and Life is very dear to all .....Yet Love is better than Life, and what is the heart of a bird compared to the heart of a man?”

The Student can’t understand the Nightingale’s passionate song in which she tells him he will have his rose; he makes notes on her music – “ she is like most artists; she is all style without any sincerity. She would not sacrifice herself for others.”

But of course that’s just what she does, singing all night of love with the thorn against her breast. A pure white rose springs from the frozen tree and the Nightingale sings on in her agony until the thorn pierces her heart and the perfect flower is stained crimson.

At noon (realistic detail) the Student looks out of his window and sees the red rose, thanking his good luck, while the Nightingale’s body lies cold in the long grass, the thorn still in her heart. He plucks the rose, runs to the Professor’s house and proffers it to the beautiful daughter, claiming his dance.

But the girl frowned. “O am afraid it will not go with my dress,” she answered; “and, besides, the Chamberlain’s nephew has sent me some real jewels, and everybody knows that jewels cost far more than flowers.”

The Student throws the rejected rose into the street, where it falls into the gutter and it run over by a cartwheel.

“What a silly thing Love is!” is the Student’s conclusion and he resolves to study Philosophy and Metaphysics instead, taking down a dusty book.

Why did this tragic story mean so much to a teenage girl? The unrequited love theme (both Student and Nightingale) was bound to appeal and now that I look back on it, the failure to recognise or appreciate the sacrifice made is the same as in my other favourite Fairy Tale: Hans Andersen’s The Little Mermaid.

The Student is just as unknowing and ungrateful as the Prince. But at least the mermaid gets to live on in the foam of the sea while the small brown bird with the glorious voice rots unseen in the long grass. It broke my heart and it breaks it all over again to read it for this blog post.

Maybe I thought that was what love would be like? That it always involved pain and the willing giving up of the self for the beloved? After all this time, who knows? The writing style is over-flowery in places; Oscar loved his pomegranates and rubies throughout his life. And there is no place here for the dry humour of there being no cucumbers available in the market, “not even for ready money.”

But as a teenager who had already experienced the pangs of many “crushes,” I preferred the sensuous and tragic to the warm and funny.

And now I think it was prophetic, part of Oscar’s own self-destructive streak that brought about his downfall. (He didn’t have to prosecute the Marquess of Queensberry (see below) and his friends begged him not to, knowing the risk of Oscar’s – at that time illegal – homosexual practices being exposed).

Oscar’s years picking hemp in jail were the sacrifice he made for Bosie, who, although he lived with his older lover in France in the latter part of 1897, later repudiated him and married an heiress. Maybe Constance, Oscar’s wife, too would have seen herself in the role of Nightingale with Oscar as Student and Bosie as the Professor’s daughter.

I’m glad to say it wasn’t prophetic of my own later life: no trampled roses there. But it still speaks to me with an incredible poignancy and I wouldn’t swap it for any more robust story with a happy ending.

Oscar Fingall O’Flahertie Wills Wilde was born in Dublin in 1856. His father was a surgeon and his mother, “Speranza,” a hostess both Society and Political. After studying at Trinity College, Dublin, Oscar won a scholarship to Magdalen, Oxford, where he took Firsts in Mods and Humanities and won the Newdigate Prize for his poem, Ravenna.

Although an avowed Aesthete at Oxford, he was of powerful build with hands like hams. So when some Hearties decided to dunk him in the Cherwell as a punishment for effeminacy, they came off rather worse. In 1884 he married Constance Lloyd, who bore him two sons. In 1888, he published The Happy Prince and Other Tales. The last decade of the 19th century was enormously productive for him: his only novel, The Picture of Dorian Grey (1890); Lady Windermere’s Fan (1892); An Ideal Husband and The Importance of Being Earnest (1895).

1895 also saw his imprisonment with hard labour for two years for the crime of gross indecency, resulting from his unwise decision to prosecute the Marquess of Queensberry for libel, the Marquess being the father of Oscar’s lover Lord Alfred Douglas (“Bosie”). In prison Oscar wrote the Ballad of Reading Gaol (1898) and De Profundis, published posthumously. Oscar Wilde died, a broken man, in 1900.

Mary Hoffman is the author of numerous books including the best-selling picturebook Amazing Grace (1991) , and the well known ‘Stravaganza’ series for young adults, beginning with ‘City of Masks’, Bloomsbury 2002, which are set partly in our modern world and partly in an alternate universe’s 16th century Italy. She has also written YA historical fiction like the highly acclaimed ‘Troubadour’. Her website is http://www.maryhoffman.co.uk/, her personal blog is The Book Maven and she is the founder of the collective blog The History Girls

Picture credits:

'The Nightingale and the Rose', copyright PJ Lynch, is shown here by kind permission of the artist. More of his lovely work can be seen at pjlynchgallery.blogspot.co.uk

'Single red rose' by Kate Greenaway, at Wikimedia Commons

Published on May 24, 2013 00:53

May 17, 2013

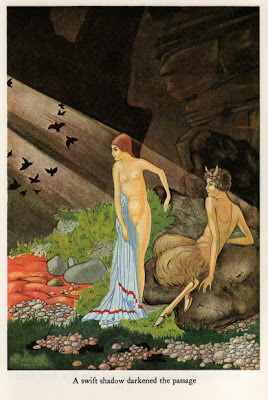

Magical Classics: ‘The Crock of Gold’ by James Stephens

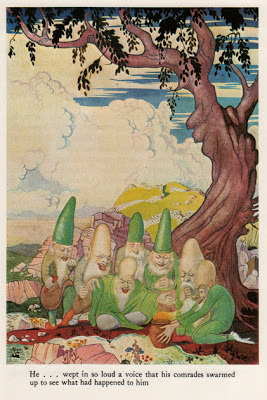

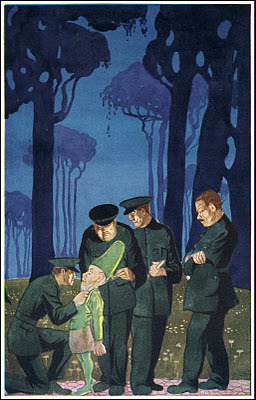

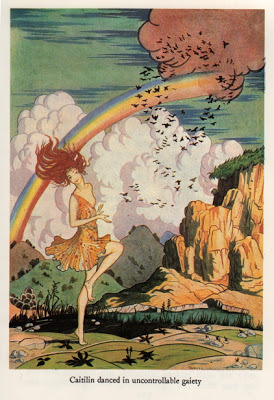

This is an enchanting and also completely lunatic book by the poet James Stephens, a friend of Yeats and James Joyce - who asked for his collaboration in finishing 'Finnegan's Wake', although this never actually happened. It was published in 1912, and a later edition was apparently to have been illustrated by Arthur Rackham, which would have been wonderful, but sadly Rackham died before it could come to pass.

The book begins with the tale of two Philosophers ‘wiser than anything in the world except the Salmon who lies in the pool of Glyn Cagny into which the nuts of knowledge fall’. The Philosophers live in the depths of a pine wood and are uncomfortably married to The Grey Woman of Dun Gortin and the Thin Woman of Inis Magrath (both women of the Sidhe), by whom they have two children: one boy, Seumas, and one girl, Brigid. These Philosophers answer all the questions of anyone who passes by, until one day, one of them decides to die - on the grounds that he now knows everything and ‘it is all bosh’.

So saying, the Philosopher arose and removed all the furniture to the sides of the room so that there was a clear space left in the centre. He then took off his boots and his coat, and standing on his toes he commenced to gyrate with extraordinary rapidity. In a few moments his movement became steady and swift, and a sound came from him like the humming of a swift saw; this sound grew deeper and deeper, and at last continuous, so that the room was filled with a thrilling noise. In a quarter of an hour the movement began to noticeably slacken. In another three minutes he was quite slow. In two more minutes he grew visible as a body, and then he wobbled to and fro, and at last dropped in a heap on the floor. He was quite dead, and on his face was an expression of serene beatitude.

This should give you an idea of the sort of book it is. The Grey Woman laments her husband: 'Who will gather pine cones now when the fire is going down, or call my name in the empty house, or be angry when the kettle is not boiling?'

Which also gives an idea of the sort of book it is… The Grey Woman follows her husband’s example and spins herself to death, after which the Thin Woman ‘smacked the children and put them to bed, next she buried the two bodies under the hearthstone, and then, with some trouble, detached her husband from his meditations.’

Next day, a neighbour, Meehawl MacMurrachu, comes to ask the remaining Philosopher about the whereabouts of a missing washboard, and – after a surreal conversation on the subject of washing in general (‘Cats are a philosophic and thoughtful race, but they do not admit the efficacy of water or soap… There are exceptions to every rule, and I once knew a cat who lusted after water and bathed daily; he was an unnatural brute and died ultimately of the head staggers’) – is advised to look for it in the hole belonging to the Leprechauns of Gort na Cloca Mora. Meehawn does so, and finds not a washboard, but a crock of gold. “‘There’s a power of washboards in that,’ said he.” And he takes it.

Which deeply annoys the Leprechauns, who therefore steal away the children. (‘A community of Leprechauns without a crock of gold is a blighted and merriless community.’) And in the meantime, Meehawl’s beautiful daughter Caitlin runs away with the god Pan…and the Philosopher sets out on a journey to find the god Angus Mac an Óg who may be able to persuade her home – and the Leprechauns lay ‘an anonymous information at the nearest Police Station showing that two dead bodies would be found under the hearthstone in the hut of Coille Doraca, and the inference to be drawn… was that these bodies had been murdered by the Philosopher for reasons very discreditable to him’ – and the Police therefore set out after him, to the general terror– and it’s all utterly wonderful.

If you can read this book aloud in an Irish accent, do so: if not, at least try to imagine one. It’s a bit like an Irish ‘Wind in the Willows’ for grown-ups – that's if you like ‘The Piper at the Gates of Dawn’ (as I do) as well as the comic tricks of Toad. There’s wisdom and laughter and pathos and joy, and Stephens doesn’t at all mind going over the top, and all in all you won’t find any other book quite like it. One last quote: a man who’s been sacked and lost everything, describes himself watching a young couple out in the rain:

There was a big puddle of water close to the kerb, and the girl, stepping daintily, went round this, but the young man stood for a moment beyond it. He raised both arms, clenched his fists, swung them, and jumped over the puddle. Then he and the girl stood looking at the water, apparently measuring the jump. They were bidding each other goodbye. The girl put her hand to his neck and settled the collar of his coat, and while her hand rested on him the young man suddenly and violently flung his arms around her and hugged her; then they kissed and moved apart. The man walked to the rain puddle and stood there with his face turned back laughing at her, and then he jumped straight into the middle of the puddle and began to dance up and down in it, the muddy water splashing over his knees. She ran over to him crying, “Stop, silly!”

When she came into the house, I bolted my door and I gave no answer to her knock.

Picture credits: James Mackenzie, from the 1928 Macmillan edition, which can be viewed and read online here: http://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/s/stephens/james/crock/

Published on May 17, 2013 00:04

May 10, 2013

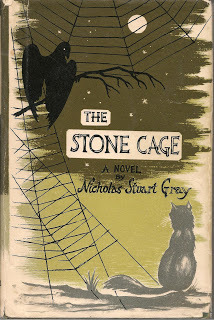

Magical Classics: 'The Stone Cage' by Nicholas Stuart Gray

Kate Forsyth writes about a much-loved childhood classic:

I first read Nicholas Stuart Gray’s novel The Stone Cage when I was about eleven. It was an utter revelation to me.

The Stone Cage is a retelling of the Rapunzel fairy tale, told from the point of view of the witch’s cat. It was the first fairy tale retelling I had ever read, and I remember being amazed that a writer could take an old, well-known story and turn it into something utterly new and surprising.

I was also utterly enchanted by the story itself, and particularly by the characters of Tomlyn the cat, and Marshall, the witch’s raven. One was sleek, self-assured, coolly amused, and tantalised by the bewitching power of sorcery. The other was hunched and tattered and miserable, with a great heart. What I remember most about The Stone Cagewas the absolute assurance of the voice. It sounded exactly how I imagined a cat would speak:

‘My name is Tomlyn. I am very beautiful. Marshall says I am spiteful and wicked and a barbarian to boot. He’s jealous of my thick grey fur, my white chin and breast, and the snowy end of my tail. I suppose he can’t help being envious, the great rusty-black thing! He’s got a big, blunt beak, and stubby wings, and tiny little eyes... He’s old and stupid and a coward; with an endless flow of long words that he can’t possibly understand.’

I had always been fascinated by ‘Rapunzel’, and reading The Stone Cage made me want to write my own retelling of the tale. I even had a go at it, when I was in my mid-teens. And, yes, my story had a cat in it too. Many years later, I did write my own retelling of the tale, though my novel Bitter Greens is very, very different.

Nicholas Stuart Gray was born on 23 October 1922, in Scotland. From a young age, he made up stories and plays to amuse his brothers and sisters, and to try and escape his unhappy childhood. He described his mother as ‘beautiful and terrifying’.‘She was a megalomaniac,’ he said in an interview in 1973. ‘We grew up terribly unsure of ourselves and doubtful of other people, always prepared to be cut down … We were always ugly, stupid, gullible, useless people in her eyes.’

Gray admitted that the character of the witch in his play The Wrong Side of the Moon (1966) is ‘almost a biography’ of his mother and I wonder if she influenced the character of the witch in The Stone Cage, who was utterly egocentric and had no feelings of remorse for any of her actions. ‘The sad thing about people like (my mother) is they are completely alone,’ Gray said in the same interview.

Gray left home at the age of fifteen, finding work as an actor and stage manager. His first play was produced before he was twenty years old, and he turned to writing for children in 1949 after seeing a hundred or more children queuing up for the cinema and wondering why there was no comparable entertainment for them in the theatre. He wrote the play Beauty and the Beast as a result, and it was shown at the Mercury Theatre in London in 1950.

Gray wanted, he said, ‘to give the children a sense of magic. Nobody attends to this enough. They give them too much realism. They can see it all on the box, they can see frightful things there. But they’re not being given a world to escape to … the world of the imagination. Children must have an escape line somewhere.’His first novel, Over the Hills to Fabylon, waspublished in 1954. It is about a city that can fly away across the mountains any time the king feels his home is in danger.

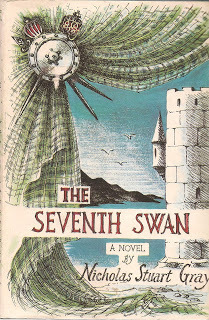

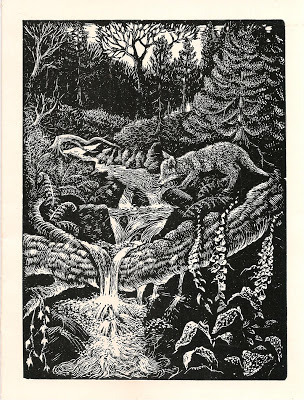

Other important works include The Seventh Swan, which tells what happened to the boy left with one swan wing instead of an arm; Down in the Cellar, an eerie story of a family of children who find a gateway to another world in their basement; Grimbold's Other World, about a black cat that teaches a boy about the world of the night; The Apple Stone, which tells of the adventures of a family of children who find a magic stone, and, of course, The Stone Cage, published 50 years ago this year.Gray’s story line follows the basic plot of the well-known Grimm fairy tale, which had been translated into English in 1882 by Lucy Crane. Her translation was based upon the 1857 edition of the Grimm’s Kinder-und-Hausmärchen, in which the character of Rapunzel is at its most passive and childlike. There is no mention of any sex, or pregnancy, or birth of twins in that tale, and Rapunzel betrays herself to the witch (rather stupidly), by complaining how much heavier she is to pull up than the prince. Within the narrow confines of that tale, Gray created a story that celebrates the redemptive power of love. Tomlyn the cat and Marshall the raven – natural enemies and rivals for the witch’s rare expressions of affection – are united in their desire to save Rapunzel. They protect her from the witch, an old, ugly and malicious woman who craves power. The story begins when the witch tricks a woodcutter into giving up his newborn daughter. He asks her what she intends to do with the baby. ‘Mother Gothel answered the man’s question in a small and faraway voice: “I will teach her my craft. Teach her to be the greatest and wickedest witch in all the world.”’ However, her plans are thwarted when Tomlyn and Marshall lay a spell on the little girl so that she was unable to work magic. Rapunzel grows to maturity, frustrating and angering the witch in her inability to remember even the simplest of spells. Then the two conspirators bring a young man to the witch’s garden in the hope he would rescue Rapunzel, but unwittingly she betrays him and he is cast down from the tower and blinded. Again, the cat and the raven work to bring Rapunzel and the prince together again, even though Rapunzel has been banished to the dark side of the moon. In the final confrontation, the raven tells the witch he no longer fears her. Rapunzel agrees, ‘very clearly and gently: ‘I’m not afraid of Mother Gothel, either.’ ‘The witch gave a shrill cry … “You must fear me! You must! Sorcery can only thrive on fear.’

Other important works include The Seventh Swan, which tells what happened to the boy left with one swan wing instead of an arm; Down in the Cellar, an eerie story of a family of children who find a gateway to another world in their basement; Grimbold's Other World, about a black cat that teaches a boy about the world of the night; The Apple Stone, which tells of the adventures of a family of children who find a magic stone, and, of course, The Stone Cage, published 50 years ago this year.Gray’s story line follows the basic plot of the well-known Grimm fairy tale, which had been translated into English in 1882 by Lucy Crane. Her translation was based upon the 1857 edition of the Grimm’s Kinder-und-Hausmärchen, in which the character of Rapunzel is at its most passive and childlike. There is no mention of any sex, or pregnancy, or birth of twins in that tale, and Rapunzel betrays herself to the witch (rather stupidly), by complaining how much heavier she is to pull up than the prince. Within the narrow confines of that tale, Gray created a story that celebrates the redemptive power of love. Tomlyn the cat and Marshall the raven – natural enemies and rivals for the witch’s rare expressions of affection – are united in their desire to save Rapunzel. They protect her from the witch, an old, ugly and malicious woman who craves power. The story begins when the witch tricks a woodcutter into giving up his newborn daughter. He asks her what she intends to do with the baby. ‘Mother Gothel answered the man’s question in a small and faraway voice: “I will teach her my craft. Teach her to be the greatest and wickedest witch in all the world.”’ However, her plans are thwarted when Tomlyn and Marshall lay a spell on the little girl so that she was unable to work magic. Rapunzel grows to maturity, frustrating and angering the witch in her inability to remember even the simplest of spells. Then the two conspirators bring a young man to the witch’s garden in the hope he would rescue Rapunzel, but unwittingly she betrays him and he is cast down from the tower and blinded. Again, the cat and the raven work to bring Rapunzel and the prince together again, even though Rapunzel has been banished to the dark side of the moon. In the final confrontation, the raven tells the witch he no longer fears her. Rapunzel agrees, ‘very clearly and gently: ‘I’m not afraid of Mother Gothel, either.’ ‘The witch gave a shrill cry … “You must fear me! You must! Sorcery can only thrive on fear.’ Rapunzel’s courage – and the bravery of her animal friends – together overcome the witch, who is transformed by the raven’s magic into a bare and lifeless-looking tree. There she must stay, ‘dead and dried, till a heart may grow inside.’

Rapunzel and her prince return to the human world, but the raven and the cat stay with the witch on the dark side of the moon, to look after her until she returns to being human. In the final scene, Tomlyn the cat pours a few drops of water on the tree’s roots, and a small, green leaf uncurls from a bare twig. In this way, Nicholas Stuart Grey shows how the animals’ faithfulness and compassion to the witch, despite her wickedness, hold out the hope of her redemption.

Gray’s dramatic training shows in the swift, graceful pace, and the quick, vivid character sketches – not a word is ever wasted. The dialogue is brilliantly done, being clever, witty and poignant in turns. Tomlyn the witch’s cat steals every scene. He speaks and acts and thinks just like a cat should, and I was not at all surprised to discover that Gray is most probably the only person ever to write a biography of his own cats (The Boys,1968). I also have a deep affection for Marshall the raven, and sympathise with his yearning to read, and his longing to love and be loved.

Haunting, whimsical, funny and heart-breaking, The Stone Cage is one of the most beautiful and profound books ever written for children. At its heart, The Stone Cage tells us that love, compassion and courage will win out over hatred, cruelty and cowardice, and that is a lesson that cannot be taught often enough.

Kate Forsyth's adult fantasy 'Bitter Greens', based on the fairytale 'Rapunzel', is published in the UK by Allison & Busby. Kate is the bestselling author of more than twenty books, ranging from picture books to poetry to novels for both children and adults. She has won numerous awards and been published in fourteen countries around the world. She lives by the sea in Sydney with her husband, three children, a rambunctious Rhodesian Ridgeback, a bad-tempered black cat, and many thousands of books. Her new novel, 'The Wild Girl', about the love affair between Wilhelm Grimm and Dortchen Wild, is to be published in the UK in 2013, and you can visit her website at www.kateforsyth.com.au

Published on May 10, 2013 00:37

May 3, 2013

Magical Classics: ‘The Strange Journeys of Colonel Polders’ by Lord Dunsany

This is the first of a series by me and a number of guests about magical never-to-be-forgotten books. The idea is to celebrate some wonderful older fantasy titles - with a wide definition of fantasy! Some will be familiar, others I hope will be unfamiliar (so we can go and search them out!) The series is called 'Magical Classics' and there are only two criteria: each title will be at least 50 years old and it will have meant much to the person who has chosen it. Here is my opening piece, and I hope you will forgive a little autobiography...

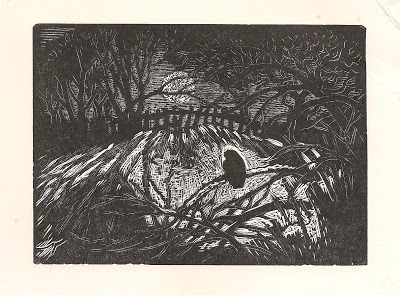

Simpson's Cat - by Bill Wild

Simpson's Cat - by Bill WildWhen I was about sixteen, we moved to a small village in Yorkshire, to live in a wonderfully rambling house with twenty rooms, three staircases and no electricity. In winter, frost coated the insides of delicate windowpanes scrawled with the diamond-engraved names of previous inhabitants. We couldn't afford to heat the house properly - indeed, apart from open fires, I don't suppose anyone had ever tried. Draughts whistled under the doors, and the only warm place was the kitchen.

In summer, the doors and windows stood open to let cats in, and stray bees, and the sounds of sheep bleating and curlews calling. One day I brought my pony into the stone-flagged living room. One night a bat flew into my bedroom through the open window and whirled around and around before finding its way out again. Outside in the dark, I could hear the beck flowing quietly down the dale to join the Aire, and owls shrieking in the trees.

I was at that happy age when one is almost independent, yet with few responsibilities. I was writing stories, about which I was blissfully uncritical. And I could spend nearly all the rest of my time reading. One day I borrowed from Skipton Public Library (yes, it’s still there) a drab, insignificant-looking little black cloth-bound book called ‘The Strange Journeys of Colonel Polders’ by Lord Dunsany, published in 1950.

I can’t remember now whether this was the first book by Lord Dunsany that I had read. I may have already come across his full length fairytale ‘The King of Elfland’s Daughter’ (to which Neil Gaiman pays graceful tribute in ‘Stardust’). At any rate, ‘The Strange Journeys of Colonel Polders’ turned out to be something quite different: difficult to categorise: not your average fantasy at all. I read it, adored it, borrowed and re-borrowed it, and then one day it disappeared. I never saw it in the library again. Perhaps it had been stolen by some less scrupulous fan. And it was only a few years ago, decades later, that I finally tracked down another copy. (Thank you, abebooks.com!)

It begins in that most Edwardian of settings, a gentleman’s club. The eponymous hero, Colonel Polders, objects to the election of a new member, Pundit Sinadryana, ‘on the grounds that he was by several thousand miles outside the circle that was intended by the original founders…’ The colonel is stiff, racist, conservative, and aggressively disbelieving of the Pundit’s claim to possess the power of transmigration, to send a spirit travelling ‘to other lives’.

“I should like to see you do it,” said the colonel…“I will show you,” said Pundit Sinadryana. And after what the colonel had just said it was difficult for him to decline the invitation; much as he wished to do so, not from any fear of the adventure, but because he did not like Pundit Sinadryana. “When?” said the colonel. “Tonight, if you like,” said the Pundit.

The experiment is tried. The Pundit burns various powders, and chants a spell ‘low and musical right into the colonel’s face, of which we heard no clear word, nor did we wish to… “Well”, said the colonel, “I don’t seem to be doing much travelling.”’

But the next moment he falls asleep. And shortly after that he’s snoring. And when, moments later, he wakes up: ‘he stood up at once and walked out of the room without saying a word.’

By Janet's Foss - by Bill Wild It’s left to the narrator and his friends, with the aid of many a glass of Malmsey wine and many a cigar, to coax from Colonel Polders the stories of the lives he has lived during the space of those few moments. The poor colonel has been a fish, a fox, a dog, a moth, a pig, an eel, a tiger. He has been a cat, a butterfly, a flea, a goose: a bat, an antelope and a mouse. At the end of each life, the colonel has died in his animal form, only to be reincarnated in the next. In each life he has experienced sensory revelations, which of course are lost to him now he has returned to his own body. And he recounts his experiences with a mixture of rapture and resentment at ‘that damned fellow Sinadryana’, that is both lyrical and extremely funny. As a pig, he explains: “…I couldn’t see very well what was going on, because of the high walls of the sty, but fortunately I had a very wet nose.” “A very wet nose?” exclaimed Charlie Meakin. “Yes,” said the colonel. “One cannot smell anything without a good wide area that is always damp… No, it is very ample life that is led by a pig.”

By Janet's Foss - by Bill Wild It’s left to the narrator and his friends, with the aid of many a glass of Malmsey wine and many a cigar, to coax from Colonel Polders the stories of the lives he has lived during the space of those few moments. The poor colonel has been a fish, a fox, a dog, a moth, a pig, an eel, a tiger. He has been a cat, a butterfly, a flea, a goose: a bat, an antelope and a mouse. At the end of each life, the colonel has died in his animal form, only to be reincarnated in the next. In each life he has experienced sensory revelations, which of course are lost to him now he has returned to his own body. And he recounts his experiences with a mixture of rapture and resentment at ‘that damned fellow Sinadryana’, that is both lyrical and extremely funny. As a pig, he explains: “…I couldn’t see very well what was going on, because of the high walls of the sty, but fortunately I had a very wet nose.” “A very wet nose?” exclaimed Charlie Meakin. “Yes,” said the colonel. “One cannot smell anything without a good wide area that is always damp… No, it is very ample life that is led by a pig.”As a fox, he lies in his earth waiting for evening, when he can hunt:

“And it is a curious thing, and you may possibly not believe me, but I waited without impatience. One can hardly imagine waiting two or three hours for one’s dinner when one is hungry, without any impatience whatever. But such was the case. “I lay there just enjoying the sound of the wind going by, and the quality of the air that I breathed, and the rounded shape of the smoothed earth where I was lying, which was so exactly suited to my needs… A fern grew at the edge of the earth, and whenever the wind blew, it waved over across my view of the sky. I watched it doing that while the sky’s colour changed slowly; and I felt no impatience with time.”

And as a hummingbird hawk-moth, he beats against a window:

“The glory of that light…was calling to me with music as well as beauty. I darted towards it, and there was no barrier, no window I mean: nothing between me and that unearthly light glowing amongst melodies and irresistible calls.” “And it was a candle?” asked Charlie Meakin.

“The Strange Journeys of Colonel Polders’ is a supremely happy book that celebrates the marvellous diversity of life. Dunsany writes as though he knows himself what it’s like to be an eel or a moth or a pig. I don’t suppose for a moment that a book like this could be published today. It breaks all structural rules. There is only the slightest of plots, with one little twist at the end to round things off. The book is barely more than a linked series of short pieces. But in this case, for me, it doesn’t matter. It’s the journeys that count, along with the semi-comical insights of the poor colonel, forever exiled from the abundant delights he has known.

For years and years, while the book was lost to me, I remembered the image of the Colonel as a fox curled in his lair, watching ‘the white light at the end of that long earth turn to a glowing blue…’

I read this story at a golden age, and for me it is a golden book.

Moonlight in the Dale - by Bill Wild

Moonlight in the Dale - by Bill WildAll artwork by Bill Wild (1903-1983) whom I knew. He lived and worked for many years in Malhamdale. Copyright: St Michael the Archangel, Kirkby Malham.

Published on May 03, 2013 01:42