Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 26

December 7, 2013

Heroines

Some time ago, out of interest, I pulled a list of ‘Children’s Classics’ off Wikipedia. There were 66 titles, and Aesop’s Fables headed the list with William Caxton’s edition of 1484. Apart from a couple of obscure titles - at least, I have never heard of ‘A Token for Children’ by James Janeway, and ‘A Pretty Little Pocket Book’ by John Newbery - I can hand on heart say that I encountered most of them during my own childhood. 'Robinson Crusoe’, ‘Ivanhoe’, ‘The Swiss Family Robinson’, ‘The Coral Island’, ‘Journey to The Centre of the Earth’, ‘Uncle Remus’,‘Black Beauty’, ‘Treasure Island’, ‘The Happy Prince’. Tick, tick, tick. And so on.

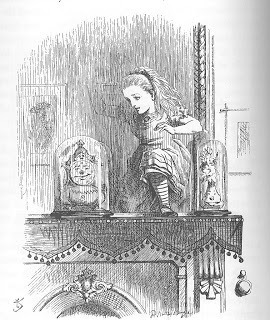

What strikes me now is the extreme scarcity of heroines in these books. Fairytales apart, there are only 12 stories out of the entire 66 in which the main character is female: they are ‘Little Goody Twoshoes’ (1765), ‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’ (1865) and ‘Through the Looking Glass’ (1871), ‘Little Women’ (1868), ‘What Katy Did’ (1873), ‘Heidi’ (1884), ‘The Wonderful Wizard of Oz’ (1900), ‘Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm’ (1903), ‘Pollyanna’ (1913), ‘A Little Princess’ (1905), ‘Anne of Green Gables’ (1908), and perhaps Mary Lennox of ‘The Secret Garden’. There are some deceptive titles which sound as though they are going to be about heroines, such as ‘Lorna Doone’ (1869) and ‘The Princess and the Goblin’ (1871) but these are really more about the male protagonists, John Ridd and Curdie.

Even though the last book on the list was published in 1918, many – in fact most – of these titles formed part of my reading a full half century later. As a child growing up in the sixties, I can’t say I consciously noticed the absence of strong female characters, since naturally I identified with the hero, whoever he might be. I swam lagoons with Jack, Ralph and Peterkin, roistered and swashbuckled with D’Artagnan, escaped across the heather with Alan Breck, roamed the jungle with Mowgli – but I did notice the rare occasions when the main character was a strong heroine. This, I think, is why so many of us loved – loved – Katy Carr, Jo March and Anne of Green Gables. We were resigned to encountering girly girls in books. And by girly girls, I mean girls filtered though a conservatice male imagination. Girls who needed to be rescued, who swooned on manly breasts, like Lorna Doone. Girls who were sweetly domestic, decorative, helpless and good like David Copperfield’s Dora. Girls who were ill-treated victims like Sara Crewe. Or else girls who simply were not there at all. It was a literary world in which boys were allowed to be Peter Pan but girls were condemned to be Wendy.

Even though the last book on the list was published in 1918, many – in fact most – of these titles formed part of my reading a full half century later. As a child growing up in the sixties, I can’t say I consciously noticed the absence of strong female characters, since naturally I identified with the hero, whoever he might be. I swam lagoons with Jack, Ralph and Peterkin, roistered and swashbuckled with D’Artagnan, escaped across the heather with Alan Breck, roamed the jungle with Mowgli – but I did notice the rare occasions when the main character was a strong heroine. This, I think, is why so many of us loved – loved – Katy Carr, Jo March and Anne of Green Gables. We were resigned to encountering girly girls in books. And by girly girls, I mean girls filtered though a conservatice male imagination. Girls who needed to be rescued, who swooned on manly breasts, like Lorna Doone. Girls who were sweetly domestic, decorative, helpless and good like David Copperfield’s Dora. Girls who were ill-treated victims like Sara Crewe. Or else girls who simply were not there at all. It was a literary world in which boys were allowed to be Peter Pan but girls were condemned to be Wendy.So we were thrilled when Katy lost her temper, disobeyed her aunt and swung in that swing; all the Victorian stuff about becoming an invalid and the heart of the family hardly seemed to count in comparison. Some of Susan Coolidge's writing is still extremely funny. You can sense her delight in her heroine's realistically child-like outbursts. Here's Katy inventing a break-time game:

…Katy’s unlucky star put it into her head to invent a new game, which she called the Game of Rivers. It was played in the following manner: - each girl took the name of a river and laid out for herself an appointed path through the room, winding among the desks and benches, and making a low roaring sound, to imitate the noise of water. Cecy was the Plate; Marianne Brooks, a tall girl, the Mississippi; Alice Blair, the Ohio; Clover, the Penobscot, and so on. They were instructed to run into each other once in a while because, as Katy said, ‘rivers do’. As for Katy herself, she was ‘Father Ocean’, and, growling horribly, raged up and down the platform where Mrs Knight usually sat. Every now and then… she would suddenly cry out, ‘Now for a meeting of the waters!’ whereupon all the rivers bouncing, bounding, scrambling, screaming, would turn and run towards Father Ocean, while he roared louder than all of them put together, and made short rushes up and down, to represent the movement of waves on a beach.

Naturally they get into trouble, but anyone can see it's worth it to have had so much fun. And Jo March, too, could lose her temper, and acted – in boots! – and wrote stories, and did things. While as for Anne – impulsive, rebellious, outspoken Anne –

Naturally they get into trouble, but anyone can see it's worth it to have had so much fun. And Jo March, too, could lose her temper, and acted – in boots! – and wrote stories, and did things. While as for Anne – impulsive, rebellious, outspoken Anne – “How dare you call me skinny and ugly? How dare you say I’m freckled and red-headed? How would you like to have such things said about you? How would you like to be told that you are fat and clumsy and probably hadn’t a spark of imagination in you? I don’t care if I do hurt your feelings by saying so! I hope I hurt them. You have hurt mine worse than they were ever hurt before even by Mrs Thomas’s intoxicated husband. And I’ll never forgive you for it, never, never!”

Such girls seemed to be going places. The trouble was that there wasn’t really anyplace for them to go. I don’t know why the imaginations of the women who created them could come up with so few goals in an era that was producing strong women by the bucketload: in the States, the early suffragists like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton; in Britain reformers like Florence Nightingale, Josephine Butler, the Pankhursts. Writing and teaching figured largely. Anne of Green Gables becomes Anne of Ingleside, a teacher, marries Gilbert Blythe and has children. Jo marries Professor Bhaer not Laurie (this we could hardly forgive, though it may be more realistic!); she does become a writer, but then goes all matriarchal and nurturing and 'womanly'. Katy travels to Europe and marries a young naval officer who is attracted to her because of her – wait for it – selfless nursing skills. No one becomes a doctor or a politician or a reformer.

So the vigorous rushing rivers of Katy’s game end up flowing decorously into the great calm land-locked sea of wife-and-motherhood. Still, at least these books gave expression, release, validation to the passion and energy of growing girls. Nowadays we take it for granted. My own daughters were never very interested in Little Women or Anne of Green Gables. They didn’t find Jo an exciting rebel but a prissy homebody taking covered baskets of Christmas dinner to the poor, selflessly selling her hair. (Her hair? What? Why?)

In Enid Blyton’s ‘Famous Five’, how I and my schoolfriends identified with the tomboy George, who cut her curly hair, wore shorts, owned a dog, told the truth at all costs and was brave and passionate. How much better she was than sissy Anne (who wore a plaid skirt and a hairslide)! And yet, and yet – that cry of hers, “I’m as good as a boy any day” – is the very mark of inequality. Why should a girl have to masquerade as a boy to be taken seriously? Why should bravery, independence and action be seen as masculine qualities?

In Enid Blyton’s ‘Famous Five’, how I and my schoolfriends identified with the tomboy George, who cut her curly hair, wore shorts, owned a dog, told the truth at all costs and was brave and passionate. How much better she was than sissy Anne (who wore a plaid skirt and a hairslide)! And yet, and yet – that cry of hers, “I’m as good as a boy any day” – is the very mark of inequality. Why should a girl have to masquerade as a boy to be taken seriously? Why should bravery, independence and action be seen as masculine qualities? We shouldn’t be complacent. I can think of plenty of independent, strong heroines in modern children’s fiction – Joan Aiken’s Dido Twite would come top of my personal list, and Harriet of ‘Harriet the Spy’, Lyra in ‘The Golden Compass', and Garth Nix's gallant Sabriel and Lirael. These girls aren’t trying to prove that they are as good as or better than boys. They simply get on with life and grapple with its problems. But there are many books for teenagers in which the heroines need – rely on – yearn for – the strong arms and love of some idealised boy. Compare Bella of 'Twilight' to Katy Carr or Jo March. It's hard to imagine either of them languishing after 'perfect' Edward.

Of all the girls in all the titles on this list of classic books for children, the most independent of all is Lewis Carroll’s Alice, who calmly steers her way through the looking glass wonderlands of her own imagination. Alice never feels in the least inferior to any male character. She stands up for herself in her own very feminine way, experimenting, chopping logic, lecturing herself and others, refusing to be snubbed, insulted or put in her place. At the end of each book when her imaginary world threatens her, she pulls it down about her ears like Samson pulling down the pillars of the temple in Gaza. She is extraordinary – and the creation of a man. But she is pre-adolescent: what does the world really hold for ‘alices when they are jung and easily freudened’? Carroll’s Alice touches a kind of bedrock: a certainty of self-worth that may be felt by many little girls in stable and happy families – but which is still all too easily lost as the teens commence.

Published on December 07, 2013 02:25

November 23, 2013

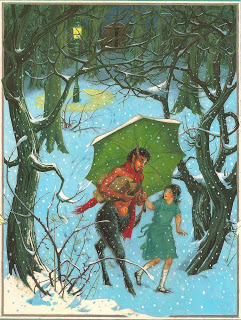

The Magical World of Narnia

This is the text of an address I gave at the Adderbury Literary Festival on Friday November 22nd, to mark the 50th anniversary of CS Lewis's death.

When I was a little girl living near Ilkley in Yorkshire, an exciting rumour ran around my primary school. A famous author was coming to live nearby! But when we heard who it was, my friends and I were rather disappointed. It was only Enid Blyton – and even though we’d all read masses of Enid Blyton’s books, and the news was interesting, we couldn’t help wishing it had been someone different. We couldn’t help wishing it could have been CS Lewis. We didn’t realise it was already too late for that. He had died on the 22nd of November 1963.

It’s hard to believe fifty years have passed since CS Lewis's death. But his books live on. The Seven Chronicles of Narnia are among the best-selling children’s books in the world; they have sold over 100 million copies worldwide and been translated into 47 languages; they’ve been broadcast on radio at least twice, they’ve been made into a BBC TV series, they’ve been turned into films and even videogames. Not bad for seven children’s books written by a middle-aged Oxford professor between 1949 and 1954.

It’s impossible to exaggerate the effect that the Narnia books had on me when I discovered them as a child. I adored them. I was super-possessive about them. I regarded Narnia as my own, private, secret kingdom – so much so that when my mother, who read aloud to us every night, suggested she might read The Lion, The Witch & the Wardrobe to me and my brother, I made such a fuss about it that she gave in. I didn’t want my brother to get into Narnia. I wanted to have it all to myself! I was in fact quite horribly selfish about it, and I shudder to think what Aslan would have had to say, but that was how passionate I felt.

Because you see, it was myNarnia. Even though the Narnia books have been read by so many people, each and every child who picks up a copy of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and begins to read it, gets into Narnia by themselves. In spite of all those millions of readers, it’s not a crowded place. If I could have understood that, perhaps I would have realised that sharing Narnia with my brother wouldn’t make any difference to the magic.

Well, at least here, tonight, I can make up for my selfishness a little – by sharing Narnia with all of you.

I’d like to talk first about my own experience of discovering Narnia, and then a bit more broadly about some of the sources CS Lewis drew upon and about some of the stories behind the books. Finally, the Narnia stories have become controversial in recent years. They’ve been criticized by several modern commentators, notably Philip Pullman, for what is regarded as Christian propaganda, racism, and misogyny – accusations that would have made me burn with indignation as a child, if I could have understood them. Whether I now agree with them or not, there is a case to be answered and I will try my best to do so.

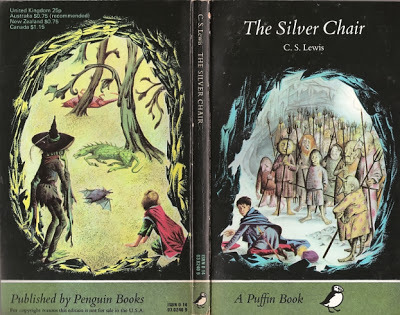

The first time I ever saw one of the Narnia books was one Christmas Day when I was about seven or eight years old. My mother had bought it for me as a Christmas present, along with about six other books (all I ever wanted was books). It was The Silver Chair, and I didn’t like the look of it.

The cover picture, one of Pauline Baynes marvellous illustrations, shows a gloomy-looking cavern with lots of grotesque little gnomes, and I’m sorry to say it put me right off. I had no idea what the book might be about; I had never heard of Narnia or CS Lewis, but this looked downright sinister to me, and it reminded me of Gollum, in The Hobbit, which had given me the creeps – and, worse still, of a truly ghastly Grimms’ fairytale ‘The Hobyahs’.

So I put off reading it as long as I could. I read all my new Enid Blyton books, and – I seem to remember – Elizabeth Goudge’s The Little White Horse, and then I was stuck with nothing new to read but this one, and as I was the sort of child who would read the back of cornflakes packets if there was nothing better to hand, I rather reluctantly opened it and began. And it started quite manageably, after all:

It was a dull autumn day and Jill Pole was crying behind the gym.

It seemed a school story. But almost immediately, the narrator went on to say, ‘This not going to be a school story’ – and then Eustace Scrubb comes along and tells Jill there’s this chance of escaping the bullies of Experiment House by getting ‘right outside this world’ – and then, ah then, in almost no time, Jill and Eustace find themselves on a high mountain – at the top of a cliff.

Imagine yourself at the top of the very highest cliff you know. And imagine yourself looking down to the very bottom. And then imagine that the precipice goes on below that, as far again, ten times as far, twenty times as far. And when you’ve looked down all that distance, imagine little white things that might at first glance be mistaken for sheep, but presently you realise they are clouds – not little wreaths of mist but the enormous white, puffy clouds that are themselves the size of mountains. And at last, in between those clouds, you get your first glimpse of the real bottom, so far away that you can’t make out whether it’s field or wood, or land or water: further below those clouds than you are above them.

Well, Jill shows off and Eustace falls over the cliff – and a lion appears and blows them both to Narnia ‘blowing out as steadily as a vacuum cleaner sucks in’ –

And there I was in this adventure, full of old castles and dying kings, forlorn hopes and bright colours, and snowy moors and talking owls, and Puddleglum the Marshwiggle, gloomy but brave – and the beautiful belle-dame–sans-merci-type Green Witch – and those gnomes who seemed so sinister turned out to be just fine in the end – with time running out to save Prince Rilian from that terrible, magical engine of sorcery, the Silver Chair itself.

And I was hooked. It was about the best story I’d ever read. More than that: there was more to itthan any story I’d ever read. After all, there was such a lot to think about. It was Lewis, not any scientist, who introduced me to the concept of the multiverse – the idea there could be many worlds, many universes besides ours. He also introduced me – little as I realised this at the time – to the Platonic parable of the cave. Just as much as Christianity, the ancient Greek philosopher Plato was one of CS Lewis’s touchstones: he even gets a mention in The Last Battle: “It’s all in Plato – all in Plato,” says the Professor, Diggory. “Bless me, what do they teach them in these schools?” In The Republic, Plato suggests that human lives can be compared to the lives of prisoners chained up in a cave, whose only knowledge of the reality which lies outside is gained from the shadows flung on to the cave wall from the world beyond. That is what lies behind this passage, in which the Green Lady, the witch, is trying to persuade the children and the Prince that there is no such place as Narnia:

“What is this sun that you speak of? Do you mean anything by the word?”“Yes, we jolly well do,” said Scrubb.“Can you tell me what it’s like?” asked the Witch (thrum, thrum, thrum, went the strings).“Please it your Grace,” said the Prince, very coldly and politely. “You see that lamp. It is round and yellow and gives light to the whole room; and hangeth moreover from the roof. Now that thing which we call the sun is like the lamp, only far greater and brighter. It giveth light to the whole Overworld, and hangeth in the sky.”“Hangeth from what, my lord?” asked the Witch, and then, while they were all still thinking how to answer her, she added, with another of her soft, silvery laughs, “You see? When you try to think out clearly what this sunmust be, you cannot tell me. You can only tell me that it is like the lamp. Your sun is a dream; and there is nothing in that dream that was not copied from the lamp. The lamp is the real thing; the sun is but a tale, a children’s story.”

Some might call this a bit of Christian propaganda. And it certainly can be interpreted that way: but first and foremost it is a neat reversal of Plato’s image. Here it’s the Green Lady who inhabits – mentally as well as literally – the underground cave. She wants to restrict the children’s reality. She wants to keep them with her, prisoners – just as the dwarfs at the end of The Last Battle are prisoners of their own scepticism, refusing to emerge from the rank stable of their own senses. What is real? Lewis asks. Is it only the evidence of our immediate senses – what we can touch and taste and see? Then what about the imagination? What about poetry and religion and philosophy?

But the children know Narnia is real, and Lewis hints at how impoverished the witch’s worldview is by showing us layer upon layer of rich reality: the glimpse of the brilliant land of Bism far down in the depths of the earth:

“Down there,” said Golg, “I could show you real gold, real silver, real diamonds.” “Bosh,” said Jill rudely. “As if we didn’t know that we’re below the deepest mines even here.”“Yes,” said Golg. “I have heard of those little scratches in the crust that you Topdwellers call mines. But that’s where you get dead gold, dead silver, dead gems. Down in Bism we have them alive and growing. There I’ll pick you bunches of rubies that you can eat, and squeeze you a cup full of diamond juice. You won’t care much about fingering the cold dead treasures of your shallow mines after you have tasted the live ones of Bism.

What is real? Our world? Fiction? Narnia? Aslan’s country? All of them…?

With such questions hanging in the Narnian air, no wonder that I, along with many other children, felt a passionate half-belief that Narnia was real. And we longed to go there. The American writer Laura Miller writes of this in her wonderful ‘The Magician’s Book, A Skeptic’s Adventures in Narnia’:

In one of the most vivid memories from my childhood, nothing happens. On a clear, sunny day, I’m standing near a curb in the quiet suburban California neighbourhood where my family lived, and I’m wishing, with every bit of myself, for two things. First, I want a place I’ve read about in a book to really exist, and second, I want to be able to go there. I want this so much I’m pretty sure the misery of not getting it will kill me. For the rest of my life, I will never want anything quite so much again. The place I longed to visit was Narnia.

I understand that so well. When my friend Frances and I were about ten, we confessed to one another our fragile belief that Narnia was real – had to be real. We invented a code name for it – ‘The Garden’ – so that we could talk about it and other people wouldn’t know. (That jealous secrecy again!) And I remember shyly telling my mother that I ‘almost felt as though Narnia is real’. “I think you’re supposed to,” was all she said, and did not elaborate. I’ve always been grateful. Enchanted and swept away, I read all the other books as fast as I could, gobbling them up in random order one after another as they were given to me for birthday or Christmas presents, or borrowed from the library. The order you read them in didn’t really seem to matter. The day I finished the series with ‘The Voyage of the Dawn Treader’ was a memorable day for me. My little brother was in hospital recovering from an emergency operation, and my parents knew that a present of the book I’d been longing for would keep me happily tucked up in an armchair for a couple of hours while they went visiting. I can still almost feel the chair’s bristly upholstery against my bare legs as, quite unconcerned about my poor little brother, I curled up and began to read.

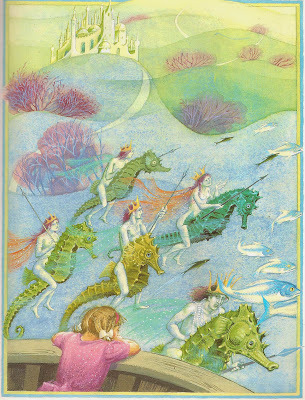

‘The Voyage of the Dawn Treader’ swept me away into an open-air world full of light. Light pervades the book: the light of sunrise over the sea, the sunlit quiet passages of the Magician’s House, sunbeams penetrating the green waters of the undersea world beneath the ship, the birds that come flying out of the rising sun to the table of the Three Sleepers, the almost painful light of the Silver Sea.

...when they returned aft to the cabin and supper, and saw the whole western sky lit up with an immense crimson sunset, and thought of unknown lands on the Eastern rim of the world, Lucy felt that she was almost too happy to speak.

For me, age ten, the island-hopping voyage of Caspian and his friends to the End of the World seemed completely original, but I now know that, as authors do, C.S. Lewis was borrowing. (We all do this all the time, by the way.) You only have to stop for a second to see how much the White Witch in The Lion the Witch & the Wardrobe owes to Hans Christian Andersen’s The Snow Queen: the tall, icy queen, the sledge, the reindeer, and the little boy whom she seduces and steals away. I can also now see the parallels between ‘The Silver Chair’ and the medieval English poem ‘Gawain and the Green Knight’ – especially the snowy winter journey over rough countryside, and the supernatural Green Lady who echoes the Green Knight of the early poem.

CS Lewis was of course immensely well-read, a medieval scholar to his fingertips, and you could say he raided his store–cupboard of magical delights and passed them on to children. The Voyage of the Dawn Treader echoes some very old Irish voyage tales known as immrama, in which a hero or saintsset out for some kind of Otherworld, stopping at a number of fantastic or miraculous islands along the way. Written in the Christian era, they hark back to older pre-Christian Celtic voyage tales, and may also have been consciously influenced by the classical tales of the Odyssey and Argonautika.

In ‘The Voyage of the Dawn Treader’, King Caspian and his friends are hoping to find ‘Aslan’s own country’: just as the Irish St Brendan sets out to find the coast of Paradise. And they succeed, in spite of Lucy’s question, ‘But do you think… Aslan’s country would be that sort of country – I mean, the sort you could ever sailto?’

The answer of the immrama is always: ‘Yes! Although you may not always get back.’ The hero Bran set out in his skin boat or curragh to search for the wondrous Isle of Women where no one is ever sick or dies. On arrival, Bran’s boat is drawn into port by a ball of magical thread which the queen of the island tosses to him. The sailors remain there happily, unaware of how much time is passing in the real world, until homesick Bran decides to return home. The queen warns against it, and especially against setting foot on land, but Bran insists – but when they reach Ireland, so many years have passed that Bran’s name is only an ancient legend, and when one man leaps out of the curragh, he crumbles to dust. Seeing this, Bran and his companions sail away, never to be seen in Ireland again.

In just the same way, the heroic Talking Mouse Reepicheep sails over the edge of the world in his coracle, “and since that moment no one can truly claim to have seen Reepicheep the Mouse. But my belief is that he came safe to Aslan’s country and is alive there to this day.”

The islands in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader – the dragon island, the Dark Island where dreams come true, the Island of the Dufflepuds, the island of The Three Sleepers – these are deliberate echoes of those the Irish hero Maeldune visits: thirty or so marvellous islands and a variety of other wonders, including the Isle of Ants – ‘every one of them the size of a foal’; the Island of Birds; an island where demon riders run a giant horse race; an island of a miraculous apple tree whose fruit satisfy the whole crew for ‘forty nights’; an island of fiery pigs, an island of a little cat; an island where giant smiths strike away on anvils and hurl a huge lump of red-hot iron after the boat (surely a volcanic eruption?) so that ‘the whole of the sea boiled up’.

Here’s an excerpt from The Voyage of Maeldune:

The Very Clear Sea They went on after that till they came to a sea that was like glass, and so clear it was that the gravel and the sand of the sea could be seen through it, and they saw no beasts or monsters at all among the rocks, but only the clean gravel and the grey sand. And through a great part of the day they were going over that sea, and it is very grand it was and beautiful.

Surely this influenced C.S. Lewis’s ‘Silver Sea’! ('How beautifully clear the water is' said Lucy to herself as she leaned over the port side early in the afternoon...'I must be seeing the bottom of the sea; fathoms and fathoms down.'

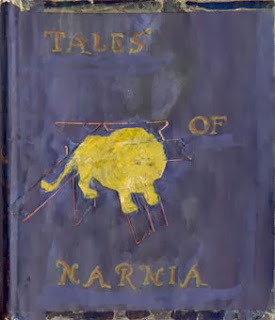

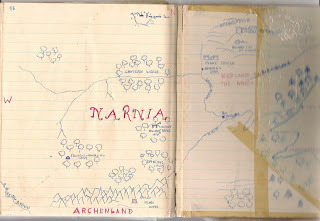

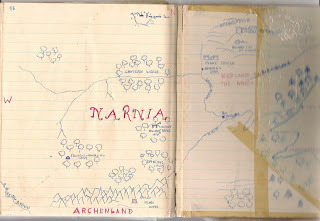

Having gobbled up the last of the Narnia books, I was so desperate to read another one that I began writing my own. It was the next best thing to getting there. “Tales of Narnia”, I called it, and filled an old hardbacked exercise book with stories and pictures based on hints Lewis had left in the Seven Chronicles: “The Story of King Gale”, “Queen Camillo”, “The Seven Brothers of Shuddering Wood”, “The Lapsed Bear of Stormness”. This was the beginning of my life an author. For one thing, it taught me the difference between reading and writing. I think I began these stories hoping to re-renter Narnia, but I found that as a creator, my own work hardly satisfied me. Guess what? I couldn’t write as well as CS Lewis! It was the beginning of a long journey.

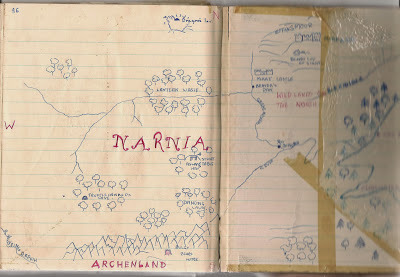

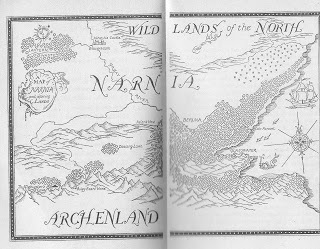

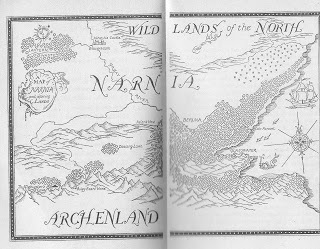

And I copied out Pauline Baynes’ map of Narnia in loving detail. There it all was, as if looking down from an eagle’s eyrie: the indented east coast with Glasswater Creek and Cair Paravel; Archenland to the south; Dancing Lawn and Aslan’s Howe and Lantern Waste in the centre of the map; Harfang and Ettinsmoor to the north.

Looked at in realistic terms, I suppose the map is really pretty sparse, but it didn’t matter. Narnia isn’t the sort of fantasy world in which one worries about economics, transport, coinage, or supply and demand. In fact, as soon as any of the characters start thinking in those terms themselves (King Miraz, for example, or the governor of the Lone Islands) they get into trouble. (“We call it ‘going bad’ in Narnia,” as Caspian magnificently remarks.) Narnia self-corrects in that respect: it will allow the existence of a Witch Queen who rules over a century of winter, but it will not permit the existence of taxation and compulsory schooling.

This can hardly be because Lewis disapproved of taxation and compulsory schooling. It’s because Narnia is a child’s world, and no ideal world for children is going to include anything so dull.

People talk a lot nowadays about the Narnia stories as religious allegories. They really aren’t. There is Christian symbolism in the books, but that is not at all the same thing. And it went clean over my head as a child. It was invisible to me – at least until The Last Battle more or less rubbed my face in it. And then I did my excellent best to forget about it. Indeed, talking to some teenage Muslim girls a year or two ago, I got surprised looks when I mentioned the Christian elements in the Narnia stories. They hadn’t noticed them either; I had to explain why, how Aslan is a parallel to Christ. I think Lewis, who only came to Christianity through stories, actually minded far more about the story than the allegory.

It is perfectly natural for a child to read “The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe” and to see Aslan as no more and no less than the literal account makes him: a wonderful, golden-maned, heroic Animal. I know, because that’s the way I read it, and that is why I loved him. Though the death of Aslan at the hands of the White Witch is the heart of the book, that ‘deep magic from the dawn of time’ works just as well on a simpler non-Christian level. A beautiful, icy queen: a golden lion. “When he shakes his mane, we shall have spring again…” Of course Aslan comes back to life! Who can kill summer?

As for “The Last Battle”, in which the Christian parallels become more explicit, it is far less popular with children, because everything goes wrong, and Narnia ceases to be, and Aslan turns into Someone Else: “And as He spoke, He no longer seemed to them like a lion...” What? What? I didn’t want the new heaven and the new earth and the new, improved Narnia, thank you very much. I wanted the old one, and Aslan the Lion, and things to go on as they always had.

So what – if anything – is wrong with Narnia? The writer Philip Pullman is not alone in disliking the books – and Lewis – intensely. For example, what about the wholesale deaths of all the child characters in an unseen railway accident at the end of The Last Battle:

“To solve a narrative problem by killing one of your characters is something many authors have done,” Pullman remarks in a 1998 article for The Guardian entitled ‘The Dark Side of Narnia’. “To slaughter the lot of them, and then claim they’re better off, is not honest storytelling: it’s propaganda in the service of a life-hating ideology. But that’s par for the course. Death is better than life, boys are better than girls, light-coloured people are better than dark-coloured people; and so on. There is no shortage of such nauseating drivel in Narnia, if you can face it.”

These are serious accusations which deserve serious consideration. The first, that Lewis feels ‘death is better than life,’ I feel is an over-statement, although I agree that The Last Battle is a difficult and flawed book. Philip Pullman is quite right to complain about sleight-of-hand. Lewis glosses over the railway accident deaths to the point of artistic dishonesty. It’s not shown. There’s no pain, no suffering, no horror. Lewis should have known better: he did know better. The death of Aslan in The Lion the Witch & the Wardrobe is tremendously moving, because it is taken seriously. The railway accident in The Last Battle is an invisible afterthought with no emotional credibility. The children don’t even know they’ve died. And I never believed in any of it for a moment.

So: one strike against him. But I don’t agree that Lewis was saying that ‘death is better than life’. The whole point of The Last Battle is that death is a doorway to more life. However, he didn’t succeed in convincing this child that anywhere could be better than the old Narnia.

‘Boys are better than girls’. Here we’re on firmer ground. I’m sorry, Mr Pullman, but this is twaddle. People who say this tend, I suspect, to be thinking of ‘the problem of Susan.’ But I was a little girl reading the Narnia books, and I knew for certain that the main character, the undoubted heroine of the first three books, is Lucy. She’s courageous, honest and steadfast – and Lewis quite obviously cares far more for her than he does for any of the boys. Peter and Susan are ciphers in the way that older children often are in family stories of that era. Like John and Susan in Arthur Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons, their main role seems to be that of surrogate parents to their younger siblings. But Lucy stands out. Lucy discovers Narnia. Lucy befriends the faun, Mr Tumnus. Lucy and Susan, not the boys, are the witnesses to Aslan’s death and resurrection. In Prince Caspian, Lucy is the one who can see Aslan when no one else can. In The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, it’s through Lucy’s eyes that we see the nightmare terrors of the Dark Island as they threaten to overwhelm the crew: it’s Lucy who sees the light in the darkness, it’s Lucy who climbs the stairs and walks down the silent corridor to the Magician’s chamber. Lucy shines.

And in The Silver Chair, it’s Jill Pole, not Eustace, who is the viewpoint character. We see Narnia through her eyes, and she has common sense, courage and obstinacy. Yes, she pushes Eustace off a cliff – but anyone might do that. She and Eustace are quite definitely equal partners. It’s Jill who discovers that the giants of Harfang mean to eat the children and the Marshwiggle for the Autumn Feast – and in The Last Battle, Jill is an actual combatant, who stands alone in front of King Tirian’s small group of supporters to shoot her arrows at the Calormene army. Even the female villains in Narnia have incomparably more energy, style and flair for wickedness than the male ones do. Compare Queen Jadis, driving the hackney carriage like Boadicea in her chariot, with creepy, snivelling Uncle Andrew; compare the White Witch with King Miraz. There is no way that boys are better than girls in the Narnia stories.

But – those Calormenes. ‘Narnia and the North’ is all very well, a stirring battle cry, but there’s no getting away from the fact that the brown-skinned people of the land called Calormen, south of Archenland, don’t come out of it very well. There are exceptions – the brave and proud Aravis from The Horse and His Boy, and the gentle and courteous Calormen knight Emeth in The Last Battle – but these remain exceptions. Calormen is depicted as a southern kingdom bordering a desert, ruled by fat, cruel, corrupt, dissolute, slave-owning aristocrats, and if you feel tempted to shrug and say ‘well, but it’s only a story’, imagine trying to explain to a Muslim child why the people of this land which so closely resembles that of The Arabian Nights worship a foul, cruel, stinking, four-armed, vulture-headed god called Tash? As a medievalist, Lewis must have been perfectly familiar with those prejudiced medieval romances which depicted Muslims as worshippers of an idol called Mahound – than which nothing can be further from the truth – and he should have known better than to take this propaganda and develop it into something even worse. The truth is, Lewis had little sympathy with or knowledge of Islam and he intensely disliked The Arabian Nights. It is seldom wise to write about something you hate. And so the charge of racial prejudice, I am afraid, does stick. Two strikes out of three.

Is it possible, then, to love the Narnia books in spite of all this? Of course it is. If we were only allowed to love what is perfect, there wouldn’t be very much left to love at all. If I no longer love them quite as much as I used to, if I now see faults where once I saw perfection, this is because I’ve grown up. Narnia is a child’s paradise: snowy woods, sunlit glades, talking animals, fauns who make you tea and buttered toast, bright waves, singing mermaids, and evil which can always be vanquished. A world in which there’s no school, no taxes, no economy: nothing boring at all. All of it presided over not by some adult ruler but by a gorgeous golden lion who comes and goes, but who is totally reliable and will always save the day.

Like Susan, I can no longer get back into Narnia, but I don’t see this as the tragedy my ten-year old self would have thought it. It’s because I’ve grown. And Narnia was part of my growing. It’s always there in my past, and it’s still there now, today, tomorrow, for any child who wants to open the wardrobe door and push past those fur coats…

“This must be a simply enormous wardrobe!” thought Lucy, going still further in…. Then she noticed there was something crunching under her feet. “I wonder is that more mothballs?” she thought, stooping down to feel it with her hand. But instead of feeling the hard, smooth wood of the bottom of the wardrobe, she felt something soft and powdery and extremely cold. “This is very queer,” she said, and went on a step or two.

Next moment she found that what was rubbing against her face and hands was no longer soft fur but something hard and rough and even prickly. And then she saw that there was a light ahead of her; not a few inches away where the back of the wardrobe ought to have been, but a long way off. Something cold and soft was falling on her. A moment later she found that she was standing in the middle of a wood at night-time with snow under her feet and snowflakes falling through the air.

Published on November 23, 2013 08:20

November 15, 2013

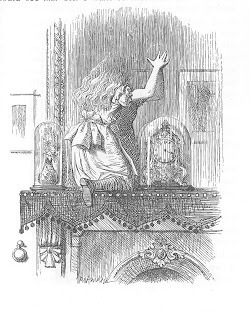

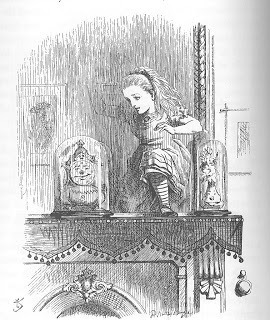

Ideas come from Looking Glass Land

I was sitting in my upstairs writing-room (the spare bedroom) when I saw one of our cats trot purposefully down my opposite neighbour’s drive and disappear into the hedge.

I found myself wondering what tales a cat could tell. For they lead lives very different to ours. They barely even inhabit the same house. From down there on the floor, the kitchen looks utterly different. (Try it.) The functions of objects are not the same for my cats and me. I don’t sleep on the table, and neither should they. But they do.

I’ve never felt desperate to lose myself in the garage. I'm not interested in what’s going on under the kitchen sink. When I go out the back or front door, I don’t tense and look carefully about for enemies. I have no idea what my cats get up to when they go out, but I suspect it’s adventurous and epic, with dangers everywhere. Cats who can go outdoors are never bored. And what must it be like to climb trees the way they do? We were pruning the apple tree a few weeks back, and I realised how very much higher it feels at the top of the ladder than it seems from the ground; and how very different the garden looks from up there.

Do you remember how it was all the black kitten’s fault that Alice went through the Looking Glass? It simply wouldn’t fold its arms properly, and she held it up to the mirror

‘that it might see how sulky it was –

‘and if you’re not good directly,’ she added, ‘I’ll put you through the Looking Glass-House…

‘Now… I’ll tell you all my ideas about the Looking-glass House. First, there’s the room you can see through the glass – that’s just the same as our drawing room, only the things go the other way. I can see all of it when I get upon a chair – all but the bit just behind the fireplace. Oh! I do so wish I could see that bit. I want so much to know whether they’ve a fire in the winter: you never can tell, you know, unless our fire smokes, and then smoke comes up in that room too – but that may be only pretence, to make it look as if they had a fire. Well then, the books are something like our books, only the words go the wrong way; I know that, because I’ve held up one of our books to the glass, and then they hold one up in the other room.’

Stop for a moment and just reflect (sorry!) on Alice’s chatter. She's clearly been thinking about that looking glass for quite a while, and she's come up with the convincingly child-like (and extremely creepy) notion that the people in it are different from us - and that they may be deliberately deceiving us. It's not Alice's own reflection who holds up the book in the mirror, but a mysterious ‘they’ - and this is a very good piece of observation. The looking glass is on the high mantelpiece. Alice, as a little girl, is not tall enough to see herself in it: if she holds a book up over her head she can see only the reflected book and not the person holding it, who might therefore be... anyone...?

Alice continues: ‘You can see just a little peep of the passage in Looking-glass House, if you leave the door of our drawing room wide open: and it’s very like our passage as far as you can see, only you know it may be quite different on beyond.’

Alice continues: ‘You can see just a little peep of the passage in Looking-glass House, if you leave the door of our drawing room wide open: and it’s very like our passage as far as you can see, only you know it may be quite different on beyond.’

And, of course, it is. ‘What could be seen from the old room was quite common and uninteresting, but all the rest was as different as possible. For instance, the pictures on the wall next the fireplace seemed to be all alive, and the very clock on the chimney piece…had got the face of a little old man, and grinned at her.’

Adults as well as children often ask writers the dreaded question, ‘Where do you get your ideas from?’ It’s so very difficult to answer, because a lot of the time, we simply don’t know. But I’ve evolved an answer. Fittingly, it’s in the shape of a story. Some years ago on a book tour I stayed in a Manchester hotel, and my room overlooked the windows of a derelict building across the street. Because I'm a storyteller, I immediately imagined a face in one of the broken windows, looking back at me. Whose might it be? A ghost? A fugitive? A murderer? A drug-smuggler? Somebody from the past? An alternative me? Any one of those choices would lead to a different story.

To be a storyteller - or a reader - is to see the world from someone else's point of view. Ideas come from that hop across the street, that quantum jump that takes you out of yourself into a different place, a place from which you see the world at a fresh, different, slewed angle.

© Katherine Langrish

I found myself wondering what tales a cat could tell. For they lead lives very different to ours. They barely even inhabit the same house. From down there on the floor, the kitchen looks utterly different. (Try it.) The functions of objects are not the same for my cats and me. I don’t sleep on the table, and neither should they. But they do.

I’ve never felt desperate to lose myself in the garage. I'm not interested in what’s going on under the kitchen sink. When I go out the back or front door, I don’t tense and look carefully about for enemies. I have no idea what my cats get up to when they go out, but I suspect it’s adventurous and epic, with dangers everywhere. Cats who can go outdoors are never bored. And what must it be like to climb trees the way they do? We were pruning the apple tree a few weeks back, and I realised how very much higher it feels at the top of the ladder than it seems from the ground; and how very different the garden looks from up there.

Do you remember how it was all the black kitten’s fault that Alice went through the Looking Glass? It simply wouldn’t fold its arms properly, and she held it up to the mirror

‘that it might see how sulky it was –

‘and if you’re not good directly,’ she added, ‘I’ll put you through the Looking Glass-House…

‘Now… I’ll tell you all my ideas about the Looking-glass House. First, there’s the room you can see through the glass – that’s just the same as our drawing room, only the things go the other way. I can see all of it when I get upon a chair – all but the bit just behind the fireplace. Oh! I do so wish I could see that bit. I want so much to know whether they’ve a fire in the winter: you never can tell, you know, unless our fire smokes, and then smoke comes up in that room too – but that may be only pretence, to make it look as if they had a fire. Well then, the books are something like our books, only the words go the wrong way; I know that, because I’ve held up one of our books to the glass, and then they hold one up in the other room.’

Stop for a moment and just reflect (sorry!) on Alice’s chatter. She's clearly been thinking about that looking glass for quite a while, and she's come up with the convincingly child-like (and extremely creepy) notion that the people in it are different from us - and that they may be deliberately deceiving us. It's not Alice's own reflection who holds up the book in the mirror, but a mysterious ‘they’ - and this is a very good piece of observation. The looking glass is on the high mantelpiece. Alice, as a little girl, is not tall enough to see herself in it: if she holds a book up over her head she can see only the reflected book and not the person holding it, who might therefore be... anyone...?

Alice continues: ‘You can see just a little peep of the passage in Looking-glass House, if you leave the door of our drawing room wide open: and it’s very like our passage as far as you can see, only you know it may be quite different on beyond.’

Alice continues: ‘You can see just a little peep of the passage in Looking-glass House, if you leave the door of our drawing room wide open: and it’s very like our passage as far as you can see, only you know it may be quite different on beyond.’And, of course, it is. ‘What could be seen from the old room was quite common and uninteresting, but all the rest was as different as possible. For instance, the pictures on the wall next the fireplace seemed to be all alive, and the very clock on the chimney piece…had got the face of a little old man, and grinned at her.’

Adults as well as children often ask writers the dreaded question, ‘Where do you get your ideas from?’ It’s so very difficult to answer, because a lot of the time, we simply don’t know. But I’ve evolved an answer. Fittingly, it’s in the shape of a story. Some years ago on a book tour I stayed in a Manchester hotel, and my room overlooked the windows of a derelict building across the street. Because I'm a storyteller, I immediately imagined a face in one of the broken windows, looking back at me. Whose might it be? A ghost? A fugitive? A murderer? A drug-smuggler? Somebody from the past? An alternative me? Any one of those choices would lead to a different story.

To be a storyteller - or a reader - is to see the world from someone else's point of view. Ideas come from that hop across the street, that quantum jump that takes you out of yourself into a different place, a place from which you see the world at a fresh, different, slewed angle.

© Katherine Langrish

Published on November 15, 2013 03:03

November 8, 2013

What is YA fiction?

Here, in order from the left, are Delia Sherman, Susan Cooper, Garth Nix, Neil Gaiman (at the back, heading towards his seat), Will Hill and Holly Black, taking part in a panel at the World Fantasy Conference 2013, which as you probably know was held in Brighton over last weekend. What they were discussing provoked a good deal of passionate comment from the audience, both agreement and disagreement – most of which remained pretty much inaudible, as for some unknown reason the massive conference hall floor was not provided with roving mikes.

The subject under discussion was: "The Next Generation: Are All the Best Genre Books Now YA?" and the explanation ran: "Over the past decade the young adult market has seen a huge boom in genre titles and readers, in no small way helped by the Harry Potter series, The Hunger Games and the works of Philip Pullman and Neil Gaiman. What has caused this surge amongst younger readers, and can it be used to keep them reading into adulthood?" However, as these things tend to do, the discussion veered away into a conversation about the nature of YA fiction: what it is and what it isn't, and what makes it what it is.

So when is a book YA? It's not easy to say. Perhaps it's simply when the protagonist is a teenager or young adult. So does that make 'The Catcher in the Rye' a YA book? Discuss... But is 'To Kill a Mocking Bird' a children's book, just because Scout, the point of view character, is a child? Clearly not: so it's not as straightforward as that.

Moreover, is YA fiction a new phenomenon? Other members of the panel were in broad agreement with Neil Gaiman when he said - I paraphrase - that YA is a new genre, and that in his youth and that of most of us, we sprang from reading children's books straight into adult fiction, especially genre fiction. Teenagers were not especially catered for.

Deep in discussion - CJ Busby and Elizabeth Wein; Kathleen Jennings listening behind

Deep in discussion - CJ Busby and Elizabeth Wein; Kathleen Jennings listening behindSome of the people sitting around me wanted to question or at least qualify this - but it's difficult to make a nuanced point while effectively yelling from the fifteenth row. Elizabeth Wein, sitting behind me, pointed out that maybe the perceived absence of YA fiction in the 60's and 70's is more about categorisation than actual fact. She pointed to books such as KM Peyton's Flambards series (in which the heroine grows up, elopes, marries, is widowed, remarries twice, has a child, loses a child...), Rosemary Sutcliff's historical novels, published as children's books, but always with young adult heroes - and Ursula K Le Guin's Earthsea novels in which the main characters start out as young adults and eventually even grow old.

So if ‘Young Adult’ is a new category, maybe this is only true in the sense that the idea been newly created: the books were always there.

Of course Neil Gaiman is correct to say that we also moved into ‘adult’ genre fiction. Of course we did – to Agatha Christie and Dorothy Sayers, John Buchan, Isaac Asimov, Arthur C Clarke, Jack Schaeffer, Georgette Heyer. But what about Alan Garner’s ‘The Owl Service’? Is that a children's book? Is ‘Red Shift’? What about TH White’s ‘The Once and Future King’? Also available were many non-genre (for want of a better word) novels which were both accessible and attractive to teenage readers and which dealt specifically, many of them, with the pains and challenges of growing up: Rumer Godden’s ‘The Greengage Summer’, Dodie Smith’s ‘I Capture the Castle’, Jane Gardam’s ‘A Long Way From Verona’, and ‘Bilgewater’, and ‘The Summer After the Funeral’. Some of these were labelled adult books, some children’s: for better or worse, all would be marketed as YA today. Labels or no labels, they existed.

These were the books I pulled off my parents’ shelves, or found for myself in the libraries as I – never left children’s books behind, I never stopped reading them – but as I hacked my own paths through the uncharted jungle that lay beyond the children’s shelves.

Elizabeth Goudge’s novels are a case in point. She may be best known today for her children’s novel ‘The Little White Horse’, which JK Rowling’s praise probably helped back into print. It is indeed a lovely book, and so are her other children’s novels, especially my favourite, ‘Linnets and Valerians’- but she was, in the main, a writer of adult novels. At age 14, I found depth and complexity in her adult fiction – a thoughtfulness, a slower narrative pace, a concern for the difficulties of relationships, and a delight in abstract concepts of philosophy and religion which opened my horizons. There were nearly always children in these books, but the children interacted with adults and their concerns in an un-children’s-book-like way. Goudge wrote of terror and horror and mental illness. The sensitive child Ben, in ‘The Bird in the Tree’, is haunted by a sketchbook he has found which contains pictures of dead and decomposing bodies. He becomes terribly afraid of death for himself and for those he loves – but he doesn’t tell, or not for a long time. The story is not about Ben, but about a love affair between his mother Nadine and his cousin David, which threatens to break up his parents’ marriage and split his family. Ben and his brother and sister are not in control, but they are still affected by the actions of the adults in their lives.

Is this is what makes ‘The Bird in the Tree’ adult fiction? This lack of centrality for the child or teenage characters? What we now term YA fiction places the young person in the focus of the action, in the learning, decision-making centre. So Cassandra in ‘I Capture the Castle’ grows and learns, watches and experiences, and makes in the end the wise and sad decision not to accept an offer of love which is largely pity. But the boy Leo, in LP Hartley’s ‘The Go-Between’, although the point-of-view character, is on the edge of the action. He doesn't understand what he's doing. Like Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird, he needs his adult self to narrate, to mediate, to understand, to explain. The child Leo has a minor part in adult lives. He is collateral damage, manipulated and used.

Finally, the panel and I think the floor agreed with Holly Black that the perennial attraction of Young Adult fiction - whether it was first published with that tag or not - is its freshness of perception. When adult fiction deals with childhood and adolescence, it tends to concentrate on loss of innocence, on damage and disillusion. YA fiction is all about rites of passage - first love, first kiss, first independence - and the thrills and spills of growing up.

Published on November 08, 2013 03:36

October 30, 2013

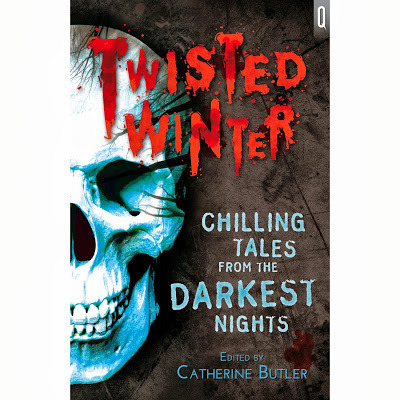

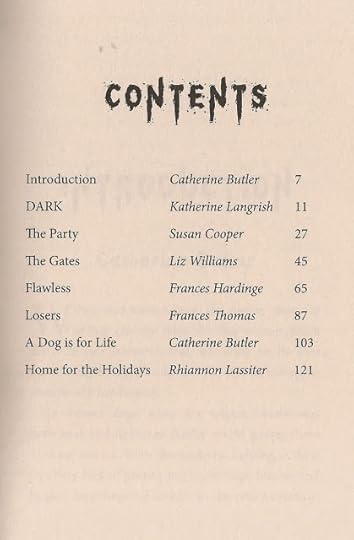

Twisted Winter

I’m not afraid of the dark. It’s streetlights I don’t like, especially those glaring orange sodium lights. Have you noticed how strange they make people look, on the street at night? How their faces go pale and bloodless, and their clothes turn a dark, dirty grey, no matter what colour they really are? Have you noticed how hard it is even to see people properly – because the streetlights make them the same no-colour as everything else - as if they aren’t really there at all, just moving shadows? There’s no such thing as colour. All those bright reds and blues and greens we see in daytime are only wavelengths. What shows up under the orange streetlights is just as real as what you see in daylight.

Maybe more real.

So begins my story "DARK", in this new anthology well-received by Amanda Craig in the Times last Saturday as 'a haunting, well-written collection of spooky short stories edited by Catherine Butler'. As you're reading this, I'm heading down to Brighton for the World Fantasy Convention. In the meantime, if you feel like some Hallowe'en tales, here's a look at the contents page.

My favourite may just be Frances Hardinge's beautifully creepy take on the Snow Queen - but then there's Susan Cooper's terrifying costume party, and Frances Thomas's eerie water spirit, and Liz Williams' poignant mix of Egyptian myth and dank English countryside - and Cathy Butler's very odd dog story, and Rhiannon's retelling of the Persephone myth - and - well, see for yourselves.

Happy Hallowe'en!

Published on October 30, 2013 11:25

October 24, 2013

Other Worlds (3)

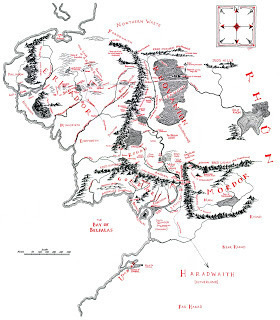

My first of these three posts discussed the three classic fantasy worlds I grew up reading and loving: Narnia, Middle Earth and Earthsea. In my second, last week, I talked about a variety of more recent fictional worlds. In this post I want to ask the simple question: why? What’s it all about? Why bother to invent a world, anyway? And are all fantasies equal, or are some more equal than others?

For aren’t fantasy worlds merely the fictional equivalent of theme parks? Places where you can go to see the dragons? Easy options on the writers? All you need is a few mountains – let’s call them the Eversnow Range; a deep and dark forest – Dimhurst, perhaps, or Tanglewood; a city on a hill – Goldthrone, or Valiance – oh, and a river to join them all together – and you’re away. You people the place with a pseudo-medieval society operating on feudal principals, with peasants, thieves, soldiers, lords and a king – shake in supernatural creatures of your choice, and stir.

Unfair? Yes, terribly; and no, not at all. This is the generic world Diana Wynne Jones christened Fantasyland. And if any of you have missed out on her brilliantly witty and razor-sharp book mapping out the many, many clichés of fantasy – why, for example, the place is infested with leathery-winged avians, why visits to taverns nearly always involve brawls, and why so much stew is consumed – you need to read it. It’s called ‘The Tough Guide to Fantasyland’: strap on your sword, pull on your boots and don that cloak: your quest is to go out and find it – now. (At the very least, if you are a writer, it will encourage you to provide your characters with a more varied diet.)

I’m thinking aloud here. A fantasy world can have some or all of these components and be brilliant – or it may be really stale and clichéd. These things by themselves are not what fantasy is really all about. They are only the trappings of fantasy, and often pretty threadbare too.

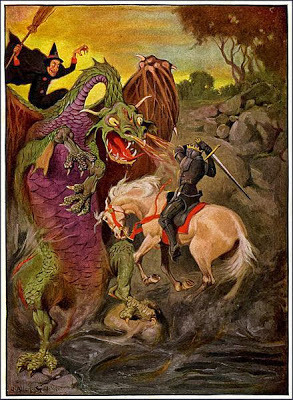

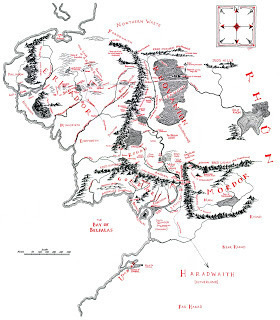

Why should most fantasies describe medieval-style worlds? I'm not saying they shouldn't: but why? Is it some kind of nostalgia? Why should swords be considered more picturesque than guns, when both are designed for killing people? If ‘picturesque’ is really all we are aiming for, we have no business writing fantasy at all. The medievalism of most modern fantasy worlds is due to the influence of Lewis and Tolkien – both medieval scholars, both steeped in the worlds of Malory’s Morte D’Arthur, Spenser’s Faerie Queene, and the Norse mythologies – heavily filtered through late Victorian romanticism. (Of course they could both read the Eddas in the original, but we know of Lewis in particular that he first encountered the Norse legends as a boy, probably in a book looking something like the one pictured above - wonderful, isn't it?) And the Morte D’Arthur and the Faerie Queene are themselves exercises in nostalgia and romantic yearning for a golden age of chivalry that never was. Malory was writing at a time of fierce civil war in England – the Wars of the Roses – and there’s a picturesque name for a nasty conflict. Arthur unifies Britain, then things fall apart: treachery overtakes the Round Table: Arthur dies.

Yet some men say in many parts of England that King Arthur is not dead, but had by the will of our Lord Jesu into another place; and men say that he will come again, and he shall win the holy cross. I will not say that it shall be so, but rather I will say, here in this world he changed his life. But many men say that there is written upon his tomb this verse: HIC IACET ARTHURUS, REX QUONDAM REXQUE FUTURUS.

This must have been cathartic stuff, back in the bloodstained fifteenth century. It still is! And then Edmund Spenser was as much engaged in national myth building as telling a story: Queen Elizabeth I as Gloriana: Tudor England as a European power. And Wagner’s Ring cycle was part of 19th century German nationalism... Smaug owes so much to Fafnir.

I really have nothing against medievalism in fantasy per se: my own first three fantasies, the 'Troll' trilogy, are set Viking Scandinavia; and the fourth, Dark Angels, is set in the late 12th century. I loved and love Malory, Tolkien, Lewis, the Eddas, The Faerie Queene, The Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia, the Narnia stories, almost anything by Robin McKinley, and so on and on. But these are stories, these are writers, who have something to say: something they throw their hearts into, something worth listening to even if in the end we don’t agree: because it’s sincere. Medievalism by itself is not enough.

There are badly written, badly conceived fantasy novels – just as there bad novels in other areas of fiction – which have given the genre a reputation for puerility, superficiality, escapism. The ingredients are the sword and sorcery clichés: blond warriors with bulging muscles and magical swords, scantily clad nubile princesses, evil dark lords, bald executioners, battles to save the universe or at least the world, yawn, yawn… together with a giveaway coarseness of imagination, a lack of subtlety and moral depth: a readiness to assume that one side is right and the other wrong regardless of how they actually behave. Thus in some fantasies, ‘heroes’ can perform feats of sadistic violence which readers are invited to admire – so long as the victims are labelled evil.

It may seem harmless, but I find this type of fantasy with its warped values especially disturbing when aimed at children and young adults, and it seems to me that the fantasy setting is used as an excuse. “It’s not real,” we might imagine the author and publisher arguing: “it’s just a fantasy!” The same kind of thinking takes children to visit the London Dungeon, a tourist attraction which makes entertainment out of ancient instruments of torture. Because it seems ‘old fashioned’ and long ago, it’s somehow not real. The owners wouldn’t dream of lining up busloads of schoolkids to see tableaux of waterboarding or electric wires being attached to the genitals – but thumbscrews and racks are all right, apparently. Because no one really believes. No one uses their imagination sufficiently to understand that these things aren’t quaintly historical, but instruments of appalling cruelty.

So when shouldn’t we write about fantasy worlds? Well, we shouldn't be writing fantasy if we think using heroes and dark lords and dragons is an easier option than coming up with living, breathing characters. We shouldn't be writing fantasy if we think it's an easier proposition than researching a genuine historical period. (It may be harder, coming up with a coherent world, from scratch!) Fantasy shouldn't be fancy-dress.

And when should we be writing fantasy? When that is the way the truth shows us it wants to appear. When, as in poetry, there is no better way of saying what needs to be said. When a story needs a dragon, not as a tired plot device or something for the hero to slay, but as a being which incorporates beauty, terror, greed, destruction, ancient knowledge – or even, as in Chinese legend, good fortune, harmony, the Tao - when this that dragon appears in all his fiery glory, we will apprehend something about the world in a more vivid, more complete way than we ever could without him. Symbols are not there to be reduced to their meanings, they are there to enhance meanings, to help us understand the world more fully and to see it anew. And this, to my mind, is what fantasy is for, too.

Picture credits:

Knight fighting dragon: Frontispiece to chapter 12 of 1905 edition of J. Allen St. John's The Face in the Pool, published 1905 Wikimedia Commons

Asgard & the Gods, photo, personal possession of Katherine Langrish

St Margaret with dragon: detail: Schaezlerpalais Predella mit Heiligen, Bartolomeus Zeitblom, Wikimedia Commons

Published on October 24, 2013 03:23

October 19, 2013

Other Worlds (2)

Earthsea, Narnia, Middle Earth – the three classic fantasy worlds I talked about last week – are distinctive places. Most children – most people you meet – will have a pretty clear picture of at least the last two. If you were dropped at random into one of these worlds, you would soon be able to guess which one it was.

There has been a great deal of fantasy written since these worlds were created, but not much that competes with them in iconic status and recognisability. Try thinking of names of other worlds, and “Discworld” is the one that springs most readily to my mind. At the borders where fantasy and science fiction blur, there may be others – "Dune", maybe - but what in fact are modern writers doing with fantasy worlds? Is sub-creation, as Lewis called it, their primary concern?

First of all there are the fantasy worlds which offer a slightly different version of our own. One example is Joan Aiken’s wonderful alternative Georgian England – not Georgian at all, of course, because the Stuart kings are still in power, and instead of Bonnie Prince Charlie, we have ‘Bonnie Prince Georgie’ and a whole series of wonderfully bizarre Hanoverian plots to bump off the reigning monarch and put him on the throne. We know we are not going to get historical accuracy, so we play a happy game of follow-my-leader through the wildest places. Pink whales (“Night Birds on Nantucket”), a sinister overweight fairy queen in a South American Welsh colony (“The Stolen Lake”), a plot to roll St Paul’s Cathedral into the Thames in the midst of a royal coronation (“The Cuckoo Tree”), foiled by tent-pegging it down from the back of a galloping elephant… That one initial twist, parting her fantasy world from history, gave Aiken permission to let her imagination loose. And her imagination was powerful, joyous, puckish. Her books are always full of energy, but they can also be eerie, sad. It’s a long walk in the dark/on the blind side of the moon, a character sings in one of her short stories; and it’s a long day without water/when the river’s gone…

First of all there are the fantasy worlds which offer a slightly different version of our own. One example is Joan Aiken’s wonderful alternative Georgian England – not Georgian at all, of course, because the Stuart kings are still in power, and instead of Bonnie Prince Charlie, we have ‘Bonnie Prince Georgie’ and a whole series of wonderfully bizarre Hanoverian plots to bump off the reigning monarch and put him on the throne. We know we are not going to get historical accuracy, so we play a happy game of follow-my-leader through the wildest places. Pink whales (“Night Birds on Nantucket”), a sinister overweight fairy queen in a South American Welsh colony (“The Stolen Lake”), a plot to roll St Paul’s Cathedral into the Thames in the midst of a royal coronation (“The Cuckoo Tree”), foiled by tent-pegging it down from the back of a galloping elephant… That one initial twist, parting her fantasy world from history, gave Aiken permission to let her imagination loose. And her imagination was powerful, joyous, puckish. Her books are always full of energy, but they can also be eerie, sad. It’s a long walk in the dark/on the blind side of the moon, a character sings in one of her short stories; and it’s a long day without water/when the river’s gone…

Diana Wynne Jones followed Aiken’s lead: many of her books are set in alternative universes that closely parallel our own except for one crucial difference: the existence of magic. She goes so far as to suggest that the absence of magic in this world is something of an aberration. Each world diverges from the next in its series because of a different outcome to some historical event – Napoleon winning the Battle of Waterloo, for example. ( I suspect that Susanna Clarke, of "Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell", read Joan Aiken as a child: her marvellously convincing magical Regency England does seem to owe something, in the best possible sense, to Aiken's lively tales.) And the ‘In-Between Place’ in Diana Wynne Jones's "The Lives of Christopher Chant" owes something in concept, though not in presentation, to CS Lewis’s ‘Wood Between the Worlds’ in 'The Magician’s Nephew': a neutral space, a jumping-off ground between universes.

Fascinating, fun, and sometimes thought-provoking, these books are not high fantasy in the classical sense. They don't offer self-contained Secondary Worlds like Middle Earth, or Narnia. But they share a purpose with the next one I’m coming to: Terry Pratchett’s ‘Discworld’.

Discworld has grown enormously over the series. It began – in “The Colour of Magic” as a spoof, a comic take on popular sword-and-sorcery novels. With characters like the incompetent wizard Rincewind and the warrior Cohen the Barbarian, it was brilliant comedy, spot on the mark. But Pratchett was too good a writer to remain content with such an easy target. The books rapidly became more serious of purpose (though still extremely entertaining). Discworld fits all the criteria for an instantly recognisable, self-contained imaginary world. It is carried through space by four elephants standing on the back of a giant turtle. It has a consistent geography, with its central mountain range at the Hub, the Ramtops, the city of Ankh-Morpork, the cabbage fields of Sto Lat; its directions (hubwards and rimwards rather than north and south ). There is nowhere quite like it... except that nearly everything in it is a deliberate borrowing from our own Earth, viewed through a distorting fantasy lens that paradoxically allows us to see it rather more clearly. I don’t know of a more passionate advocate than Pratchett for racial and sexual equality. We might be reading about dwarves and trolls, but we’re not fooled. When Commander Vimes employs trolls, werewolves, dwarves, zombies and vampires in the City Watch, it’s not because they all live together in Ankh Morpork like one big happy family. Read "Feet of Clay", read "Equal Rites". Discworld, like the worlds of Aiken and Wynne Jones, sets Pratchett free to say exactly what he wants in a way quite different but not less seriously intended than so-called ‘realistic’ fiction.

And so we move on to wholly self-contained invented worlds. (I’m still excluding Elfland, which seems to me a different kettle of fish, and I’ll explain why some other time.) Some have been created for the sheer delight of experiencing something fantastical and other: but in the best fantasy that is never the be-all and end-all. They still have something to say. Katherine Roberts’ Echorium Sequence is a good example: it reminds me of the Earthsea books. In the first volume, "Song Quest":

And so we move on to wholly self-contained invented worlds. (I’m still excluding Elfland, which seems to me a different kettle of fish, and I’ll explain why some other time.) Some have been created for the sheer delight of experiencing something fantastical and other: but in the best fantasy that is never the be-all and end-all. They still have something to say. Katherine Roberts’ Echorium Sequence is a good example: it reminds me of the Earthsea books. In the first volume, "Song Quest":

The day everything changed, Singer Graia took Rialle’s class down the Five Thousand Steps to the west beach. They followed her eagerly enough. A Mainlander ship had broken up on the reef in the recent storms, and the Final Years were being allowed out of the Echorium to search for pieces of the wreck.

Already the reader has picked up hints of reservations about the culture which treats a shipwreck as an excuse for a class outing. The task of the Singers on the Island of Echoes is to spread healing and harmony; they are the diplomats of their world, and are able to talk with the Half-Creatures, such as the Merlee who live in the sea and are trawled for by sailors who sell their eggs as delicacies. The boy, Kherron running away and picked up by fishermen, is told:

“You wait right over there with your bucket. When we draw them in, there’ll be lots of wailing and shrieking. Don’t you take no notice. Soon as we toss you one of the fish people, you get right in there with your knife. No need to wait for ‘em to die first. They ain’t got no feelings like we humans do. Got that?”

Kherron does – but soon:

Soon he was surrounded by flapping rainbow tails, coils of silver hair tangled in seaweed, gaping mouths and gills, reaching hands, wet pleading eyes – and those terrible, terrible songs.

“Help us,” they seemed to say.

He shook his head. “I can’t help you,” he whispered... [He] watched his hand fumble in a pool of green slime and closed on the dagger. He began to hum softly. Challa, shh, Challa makes you dream...

The creatures’ struggles grew less violent. One by one their arms and tails flopped to the deck, and their luminous eyes closed. Kherron opened their guts as swiftly as her could and scooped out handfuls of their unborn children. It helped if he didn’t look at their faces. That way he could pretend they were just fish.

This is strong stuff, and Roberts is clearly interested in the differences between a superficial adherence to peace and harmony – the soothing songs of the Singers, the diplomatic missions – and the blood and guts reality that it may not be possible even literally to keep your hands clean. Colourful adventures in imaginary places don’t have to be anodyne: even heroes and heroines may do some very bad things. But in YA fiction, the learning process is usually what counts, and hope is never forgotten.

John Dickinson’s fantasy trilogy – beginning with ‘The Cup of the World’ (2004) – is a more downbeat series. You could almost call it a teenage 'Game of Thrones' - plenty of Machiavellian politics, less sex and violence. It’s set in a claustrophobic medieval-style kingdom, in a world pictured as held in a vast cup and circled by a snake or cosmic serpent. All of the characters are flawed: civil war is rife, and the main characters are themselves descendants of invaders from over the sea. Long ago, their ancestor Wulfram led his sons against the indigenous hill-people, whose goddess Beyah still weeps for the death of her son. It’s an intricate story which no brief summary can do justice: but the narrative is dark and fatalistic, with a gloom bordering at times on pessimism. This trilogy is a great corrective to the notion that fantasy is all about crude oppositions of good and bad, white and black. The main characters’ best intentions can lead to disaster, and often their intentions are selfish anyway. The descriptions of the world are lovingly detailed and rich, the writing is beautiful, and these are books I greatly admire.

John Dickinson’s fantasy trilogy – beginning with ‘The Cup of the World’ (2004) – is a more downbeat series. You could almost call it a teenage 'Game of Thrones' - plenty of Machiavellian politics, less sex and violence. It’s set in a claustrophobic medieval-style kingdom, in a world pictured as held in a vast cup and circled by a snake or cosmic serpent. All of the characters are flawed: civil war is rife, and the main characters are themselves descendants of invaders from over the sea. Long ago, their ancestor Wulfram led his sons against the indigenous hill-people, whose goddess Beyah still weeps for the death of her son. It’s an intricate story which no brief summary can do justice: but the narrative is dark and fatalistic, with a gloom bordering at times on pessimism. This trilogy is a great corrective to the notion that fantasy is all about crude oppositions of good and bad, white and black. The main characters’ best intentions can lead to disaster, and often their intentions are selfish anyway. The descriptions of the world are lovingly detailed and rich, the writing is beautiful, and these are books I greatly admire.

Last, and more recent, Patrick Ness’s trilogy “Chaos Walking” is set on another planet. The border between sci-fi and fantasy is fuzzy at best. Is this a fantasy trilogy? Why not? There is no reason other than convention why a fantasy world has to be medieval. The books ask: is there ever an excuse for violence? And there isn’t a clear answer: Todd, the adolescent main character, has a good heart and wants to do the right thing. But how do you know what the right thing is? Can you trust your own judgement? Are people what they seem? Can even first love – the most intense of experiences – sometimes be a selfish excuse for doing harm to others? Like Katherine Roberts’ Kherron, Todd learns that you can’t always keep your hands clean.

I enjoyed “Chaos Walking” immensely, but began to feel towards the end that I could have done with just a little less non-stop, breathless action, and a little more world-building. This is a trilogy which takes the moral choice to the level of a sixty-a-day habit. I loved the first book the best, maybe because there was more leisure to examine Todd and Viola’s (and Manchee’s) surroundings:

The main bunch of apple trees are a little ways into the swamp, down a few paths and over a fallen log that Manchee always needs help to get over…

The leap over the log is where the dark of the swamp really starts and the first thing you see are the old Spackle buildings, leaning out towards you from shadow, looking like melting blobs of tan-coloured ice cream except hut-sized. No one knows or can remember what they were ever s’posed to be…

… I start walking all slow-like up to the biggest of the melty ice-cream scoops. I stay outta the way of anything that might be looking out the little bendy triangle doorway… and look inside.

What will we see?

The accusation that fantasy is escapism has always seemed strange to me. Far from being away with the fairies, what fantasy writers do is to take that little step sideways out of this dimension so that they can turn around and take a really good look at this one. At its best, fantasy offers perspective, the chance to run thought experiments, the chance to alter history and see what might have happened. A chance to look at serious issues with the heat off: Terry Pratchett can tell stories about dwarfs and golems and trolls and really he's talking all the time, quite clearly, about race relations. And nobody accuses him of writing allegory, or preaching, either. And it's all fabulously entertaining.

Next week I want to ask: Why do we do it? And what are the pitfalls? When shouldn’t you be writing fantasy?

What’s it all for?

There has been a great deal of fantasy written since these worlds were created, but not much that competes with them in iconic status and recognisability. Try thinking of names of other worlds, and “Discworld” is the one that springs most readily to my mind. At the borders where fantasy and science fiction blur, there may be others – "Dune", maybe - but what in fact are modern writers doing with fantasy worlds? Is sub-creation, as Lewis called it, their primary concern?