Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 25

February 15, 2014

Magical Classics: ROOM 13 by Robert Swindells

When vampires were vampires! Sally Nicholls, and the delights of being scared out of your wits.

There was one in the corner of every classroom. A bookcase on wheels, with shelves on either side, filled with books. The books were supposed to get more difficult to read as we went up the school, but there were a few titles which cropped up in classroom after classroom. Roald Dahl, of course. (It was the early 90s). Anne Fine. Dick King Smith. Carbonel the Witch’s Cat, and Noel Stretfeild’s The Circus is Coming. These were the books were supposed to borrow and write lists of in our reading journals. They were the books we read in Silent Reading every Friday, and from which our class readers were chosen.

Most of my class weren’t great readers, but since Friday came round as surely as the moon, we all borrowed books from the bookcase, and inevitably favourites developed. In Year Seven, our classroom favourites were Beverley Naidoo’s Journey to Jo’berg, which didn’t click for me, and Vivien Alcock’s The Cuckoo Sister; a wonderful, wonderful book which any publishers reading this blog should go and bring back into print immediately.

But in Year Six our classroom favourite was Room 13 by Robert Swindells.

Room 13 was about a vampire. Not a sexy vampire, but a vampire who was slowly murdering one of the girls on a school trip to Whitby. The hotel the class were staying in didn’t have a room 13, except in the middle of the night, when it did, because that’s where the vampire lived.

The vampire was frightening. That’s why we all loved the book. We didn’t want to date him, we wanted to murder him, as the children in the novel have to, with a stick of rock sharpened to a point, a large rock to hammer in the point, and a crucifix made from the crossed sticks of a plastic kite. (I think there may have been something else they used, but I’m deliberately not looking up the plot because I’m fascinated by how much I can remember of a novel I read once twenty years ago, when I was ten. Quite a lot, is the answer. Much more than I can remember of the Enid Blytons I read and read and read at the same time.)

Oh, a torch! They had a torch as well.

I didn’t have much opportunity to be scared when I was ten. There was Point Horror, about which I was somewhat snobbish, and were anyway mostly American and never managed to frighten me. My mother never censored my reading, but she did censor my viewing – I remember not being allowed to watch Labyrinth, and she was even a bit doubtful about The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe, which went out on the BBC when I was six. I don’t remember actually being that scared of Room 13, but I remembered the thrill of reading something which didn’t patronise its audience, that included dark nights, and hidden rooms, and children with agency, and villains who were unashamedly evil. We felt respected by Room 13 in a way I rarely felt respected by Point Horror or Goosebumps. It was also a great story.

When writing my first ghost novel for children, Close Your Pretty Eyes, I never considered toning down the terror. I was more worried about making it frightening enough. I wanted the child reader to feel respected. I wanted to appeal to the sort of child who enjoyed novels like Coraline, or the scarier Doctor Who episodes. Doctor Who may cut down the blood or gore, but it rarely worries about being too frightening. I wanted a genuinely murderous villain, like the vampire in Room 13, and child characters with the agency to defeat her.

I was a little unprepared for the adults who read Close Your Pretty Eyes and professed themselves ‘too frightened’, who questioned whether it was a children’s book and read it with the lights left on. I am sure there will be children who will be too young for this book, and will not want to read it.

But when I was ten, I wanted to be frightened.

Sally Nicholls, courting danger. In the act of being swallowed by a mad tree.

Sally Nicholls, courting danger. In the act of being swallowed by a mad tree.Sally Nicholls was born in Stockton, just after midnight, in a thunderstorm. Her father died when she was two and she and her brother were brought up by her mother. She has always loved reading and spent most of her childhood trying to make life work like it did in books. After school, she worked in Japan for six months and travelled around Australia and New Zealand, then came back and did a degree in Philosophy and Literature at the University of Warwick. In her third year she enrolled in a Master in Writing for Young People at Bath Spa University. It was here at the age of twenty-two that she wrote Ways to Live Forever , her first novel, which went on to win the Waterstones Children’s Book Prize 2008. She was also named Glen Dimplex New Writer of the Year in 2008. Sally’s later work includes Season of Secrets, All Fall Down and the really rather terrifying ghost story Close Your Pretty Eyes.

Published on February 15, 2014 01:36

February 12, 2014

Review: PUREHEART by Cassandra Golds

This has to be the most heartbreakingly beautiful book I have read in years.

It begins with a reunion. Soon after attending her grandmother’s funeral, a young girl, Deirdre, looks out of the window of Corbenic, the rambling, near-derelict block of flats which is her home. She sees a young man waiting huddled under the streetlight and recognises him as Gal, the love of her life. She runs out to meet him.

Since they were five years old, Gal has always loved and defended Deirdre. As little children they played together and created a brief space of love and warmth before Deirdre’s manipulative grandmother separated them. Later, at school, Gal saved Deirdre from being burned when a bout of playground bullying went too far. Once more they were separated. Although she loves Gal entirely, Deirdre has never had the confidence or the self-esteem to believe she deserves to be loved back. But now her grandmother is dead, and Gal has returned.

“Break free,” he whispered. She touched him lightly on the arm, meaning to draw him back across the street with her, but he flinched, as if she had touched something sore. Or as if her touch was so cold it shot arrows of ice through his veins. Or as if he had not been touched for a very long time. “Have you remembered?” he said.She knew immediately what he was talking about. It was the most important thing in both their lives. “No,” she said. “Have you?”

For there is something Deirdre and Gal must find – something they once saw as children but can barely remember. In search of it, they must explore the dusty, cracked passages of Corbenic, the residential hotel which her great-grandfather built and her grandmother kept extending. Corbenic, whose corridors and stairways open on to infinite dimensions. Corbenic, which is haunted by the terrible, shrill presence of a malevolent ghost-child.

‘Pureheart’ is a reworking of the legend of the Holy Grail. Gal’s full name is Galahad, the pure-hearted knight of the Morte D’Arthur, and the derelict, multi-dimensional block of flats is a version of the Grail castle, home of the wounded Fisher King. That’s not to say the correspondences are exact. They’re not meant to be. But Corbenic is and has been the home of wounded, un-whole people. And Deirdre and Gal will never be whole and free until they find the forgotten thing at Corbenic’s hidden heart.

Cassandra Golds’ characters operate under immense psychological pressure. They are like creatures of the ocean deeps, so used to living and functioning under tons of black water that they accept it as normal. Oddly, this isn’t depressing: her heroines may seem fragile but they are brave and true as steel, and there is always hope. Her books celebrate love and the power of love, acknowledging that it can be difficult to find but affirming that in the end, it is the one thing worth having.

As they crossed the misty street together it was as if they were wading into that ancient subterranean river – the one that flows through all of us, so close to the surface and yet so impossibly deep – that marks the border between the present and the past, the land of forgetting and the land of remembering.

When I try to think of anyone whose work is remotely similar to Cassandra’s, the only writer I can think of is Hans Christian Andersen. There is the same mix of strength and lightness, beauty and melancholy, the same ability to write apparently simple fables which resonate long in the mind. It’s also an utter joy to read such beautiful prose. Golds is an artist. There are few authors of this calibre writing for anyone, anywhere, anytime. Unfortunately, it’s difficult to get hold of her books outside Australia - although they can be ordered via this website: Fishpond - so if any US or British publisher is reading this, here is an opportunity not to be missed.

Visit Cassandra's website: http://www.cassandragolds.com.au/

Published on February 12, 2014 01:06

February 7, 2014

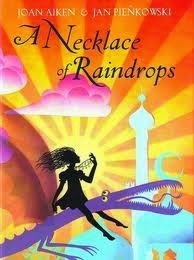

Magical Classics: "A Necklace of Raindrops" by Joan Aiken

Jo Cotterill reflects on the enduring magic of Joan Aiken's marvellous fairytales.

I don’t know how old I was when I read A Necklace of Raindrops. I only know that it caused a tremendous longing in my soul for such a necklace. I was a girly child, fond of tutus and fairy wings, and a desperate desire for my own unicorn. The Necklace fitted perfectly into my romantic visions.

One dark and stormy night (yes, one of those beginnings!), Mr Jones, recently a father, finds the North Wind, personified as a tall man, stuck in his holly tree. On helping him get free, Mr Jones is rewarded by a necklace of three raindrops which the North Wind hands over as a present for his new baby daughter. ‘I will be the baby’s godfather’ he says imperiously. He promises to bring the girl a new raindrop every year on her birthday (the necklace starts life with three raindrops) and each raindrop will confer a new magic power. By the time she has the full set of ten raindrops (on her seventh birthday) she will be able to swim any river, go unharmed in the worst storm, and make it start and stop raining, among other things.

But as always there is a catch. The little girl, named Laura, is not allowed to take off the necklace, otherwise, the North Wind says vaguely, ‘it might bring bad luck’. What kind of a warning is that?

Anyway, Laura grows into a nice little girl who loves her necklace and dutifully wears it all the time – until she begins to attend school. Another girl, Meg, is jealous of Laura’s pretty necklace and so she tells the teacher that Laura is wearing jewellery. The teacher makes Laura remove the necklace, but Meg steals it from its safe place and takes it home. Laura is distraught – all the more so because it’s her birthday soon and her godfather is due to bring the tenth and final raindrop. Meg soon finds that crime doesn’t pay because the necklace doesn’t work for her, and her father takes it away. He sells it and soon it is on a ship, destined as a present for the princess of Arabia.

Laura cries desperately over the loss of her necklace, but in a Disney-like fashion, birds and animals pop up and offer to help her find it. Apparently, she has been kind to them in the past (though the story makes no mention of it up to now – an editor these days would demand earlier references!) and now they become her personal spies, sniffing out information.

Before long, Laura is on the trail of the necklace and has to take a ride on a friendly dolphin (since she can no longer swim) to Arabia where she begs the princess to return her necklace. In the ensuing argument, the North Wind arrives with the final raindrop. Annoyed that his god-daughter has taken off his present (after nearly seven years!) he lets the raindrop fall onto the grass where it is lost. The princess takes pity on Laura and hands over the necklace, whereupon one of Laura’s tears falls onto the necklace and becomes the final raindrop.

As a child, I was fascinated by the romance in Joan Aiken’s stories. Magic was referred to in such a practical way that it was taken for granted that buses could fly, unicorns could arrive on your lawn, and raindrops could hang from a necklace without falling off. It was the fantastical element that appealed, along with the stunning illustrations by Jan Pienkowski, my favourite ever illustrator.

It is interesting to me that as a writer, I shy away from fantasy now. It was such an enormous part of my childhood, and yet I don’t write fantasy at all. I hardly read it now either, and again I can’t explain why. Perhaps the practical, cynical side of me that says magic isn’t real has shouted down the inner romantic?

And yet…and yet…as I grow older, I find myself seeking out stories with magical elements. Not necklaces or unicorns, but real life experiences that defy rational explanation. And I am more and more attracted to fiction with a romantic edge: not necessarily a falling-in-love one, but a slightly rose-tinted one where people get the happy endings they deserve.

I do think that having children has had something to do with this. I have two young daughters, and for them, every day is magical in the smallest ways. My eldest licks frost from the tree. My youngest echoes the ‘beep’ from the microwave. I have begun to look at the world in fresh ways, noticing the beaded cobwebs in the garden and feeling so disappointed if there is no one to share them with.

And now I am sharing the necklace of raindrops with my eldest. At five and a half, this is the first story that she has eagerly wanted to read for herself. I read it to her, and then she wanted to read it to me. It took us four bedtimes to get through it, but she finished it in the end and the delight on her face was beyond words.

As if I needed any more proof of the power of this fairytale, she presented me with her Christmas list. Under ‘pink mobile phone, Rapunzel Barbie and chocolate coin maker’ she had written ‘necklace of raindrops’.

Here is the 'necklace of raindrops' that I made for my daughter this Christmas. She was very excited to find it in her stocking on Christmas morning!

Jo Cotterill has been an actor, musician and teacher and now writes books at her home in Oxfordshire. She has published 21 books for young people and teenagers, including the critically acclaimed ‘Red Tears’ (as Joanna Kenrick) and her light romance series ‘Sweet Hearts’. Her new book, ‘Looking at the Stars’, a story of inspiration and imagination among refugees, has just been published by Bodley Head.

Jo Cotterill has been an actor, musician and teacher and now writes books at her home in Oxfordshire. She has published 21 books for young people and teenagers, including the critically acclaimed ‘Red Tears’ (as Joanna Kenrick) and her light romance series ‘Sweet Hearts’. Her new book, ‘Looking at the Stars’, a story of inspiration and imagination among refugees, has just been published by Bodley Head.

Published on February 07, 2014 01:00

February 1, 2014

"Happily Ever After"

Oral storytelling necessitates a framework. Anyone who’s tried singing or storytelling or in any way performing, for that’s what it is, in a crowded space, knows that you have to call for attention before you can begin. That’s why Shakespeare’s plays often begin with a prologue – a man standing on the stage to deliver a speech about the background to the drama, or a couple of minor characters loudly joking and quarrelling, or a shipwreck with lots of dramatic sound effects – something that won’t matter if you miss half of it, something to shut the audience up and make them settle down and pay attention.

A song will begin with a chord or a run of notes upon the harp or guitar, and the beginning of a story is signalled by a stock phrase: ‘Once upon a time’. It’s a device to arrest the listener, and to locate the story, placing it in a mythic but relevant past. ‘ Il était une fois ’, or ‘Es war einmal…’or ‘It wasn’t in my time, or in your time, but once upon a time, and a very good time it was…’

The device is common to so many languages, I think people must have been beginning stories in this way since paleolithic times. I'm told classical Arabic stories begin: There was, oh, what there was or what there wasn’t, in the oldest of days and ages and times…’ North American Mi’kmaq stories begin, ‘Long ago, in the time of the Old Ones…’ Czech and Hungarian stories begin, ‘Once there was, once there wasn’t…’

And this sort of opening phrase sends a subtle but distinct message to listeners. It says: ‘Pay attention!’; but it also says: ‘Though this is going to be amusing or stirring or exciting, it’s probably not true.’ It says, ‘This is a story. Sit back and listen.’

And so the room hushes, the people attend, the storyteller spins her tale. There’s a real physical element to listening to a story. It’s like going on a roller coaster. It’s not like reading, where everything happens at exactly your own pace, and you can glance ahead, or turn back to check on something, or put the whole book down for ten minutes to make a cup of coffee. Listening to a story, you are in the power of the storyteller. You must keep still and listen carefully not to miss a word. You watch her face as she frowns or smiles. The flash of her eyes, her gesturing hands. You don’t know what is coming next, or even how long the story is going to be. For she on honey-dew hath fed, and drunk the milk of paradise. Everything is a surprise.

Some stories are very short. Some are very long. Some divide into almost separate segments, picaresque narratives in which one thing follows upon another with the most tenuous of links. The princess and the prince are married, they become king and queen. The audience draws breath - but that’s not the end. The storyteller is still speaking. The king goes to war, leaving the young queen in the care of his old mother. But the old woman hates her, and so, when the queen gives birth to her first child, the old woman orders it to be killed and the blood smeared over the queen’s clothes so that everyone will think she has killed her own child…

No, it’s not the end yet.

And so, when the end does come, it is often signalled with another stock phrase, to show that the show is over. Puck delivers the epilogue; Rosalind steps out of the framework of the play to flirt with the audience about their beards. Fairytales conclude with the words ‘and they all lived happily ever after’ – or sometimes, ‘they all lived happily till they died’ – or even, ‘if they haven’t died yet, they are living there still’…

It’s getting more conscious and ironic, isn’t it?

Fairytales, contrary to what people suppose, are not naïve. Their very existence floats in the relationship between narrator and audience. Indeed it is naïve to imagine that ‘happy ever after’ – much derided as a banal or smug or thoughtless conclusion – was ever intended as much more than the signal that the story is over. The bite of narrative has been chewed and swallowed: the show is done. The listeners can get on with drinking beer, eating, bargaining, gossiping, telling rude jokes, or heading off outside for a piss, or trudging home to their own difficult wife, husband or parent. Beginnings are important, endings less so, because the stock phrases that signal the end of a fairytale do not call for attention, but dismiss it. They don’t place the story in the mythic past, they undermine it. ‘If they haven’t died yet, they are living there still’ (but how likely is that?). And so fairytale endings are far more varied than beginnings: in fact they can be purposely surreal and disconnected.

‘They found the ford, I the stepping stones. They were drowned, and I came safe.’

‘This is a true story. They are all lies but this one.’

‘There runs a little mouse. Anyone who catches it can make himself a fine fur cap!’

‘Snip, snap, snout – this is the end of the adventure.’

‘And when the wedding was over, they sent me home in little paper shoes over a causeway covered in broken glass’.

After

After the wedding

the prince and the goosegirl

rode off to spend their lives in a hall of mirrors.

After the wedding

roses sprang from the graveside, white and red,

and twined their way to the very top of the steeple.

After the wedding

little white doves flew down

to peck out the eyes of the two jealous sisters.

After the wedding

the soldier shouldered his rifle

and returned to the wars.

After the wedding

the orphan child limped home in paper-thin shoes

over a pavement clinking with broken glass.

© Katherine Langrish

Published on February 01, 2014 02:50

January 24, 2014

Sea Lion Woman: A Selkie Story for a New Millennium - by Laura Marjorie Miller

Harbor seal at Seal beach, La Jolla, California. © Ralph Pace

Harbor seal at Seal beach, La Jolla, California. © Ralph Pace I am delighted to welcome Laura Marjorie Miller to the blog. Laura writes about travel, Yoga, magic, myth, fairy tales, photography, marine conservation, and other soulful subjects. She is a regular columnist at elephantjournal.com , contributing editor at Be You Media, and public-affairs writer at UMass Amherst, and has a feature forthcoming in Yankee magazine. Her work has appeared at Tripping, GotSaga, and Dive News Network, in the Boston Globe and Parabola. She is based in Massachusetts, where she lives with a cat named Huck.

In this thoughtful piece, Laura considers the tragic beauty of the selkie legends, and wonders if it's time to find a new way of retelling and interpreting them. The wonderfully moody photographs appear by kind permission of Ralph Pace, http://www.ralphpacephotography.com/ and the magical illustrations are courtesy of Scottish artist Kate Leiper www.kateleiper.co.uk. Many thanks to both.

My favorite place in all of Boston is outside the harbor seal habitat at the New England Aquarium. The seals, shining silver-grey, their thick oily coats spattered with inky speckles, glide back and forth by the glass. Sometimes they barrel-roll to soar on their backs, navel slits to the sky, flippers folded like wings. Sometimes they bob vertically in the water like corks, serene expressions on their faces.

Every time I’m in Boston, no matter where in town I am, I’m aware of their presence. I am pulled to them, the shredded iron filings of me to the steady strong magnet of them. One doesn’t even have to pay admission to the aquarium to watch the seals, but can view them from outside, so once I park my car, I race there along the pavement of the harbor wharf. It is all I can do in public not to break into sobs at their beauty. I stand by the glass, weeping silently with longing, undried tears coating my cheeks with a rime of salt water, but also smiling with unaccountable joy. I want to be with them. I am a river running to their ocean.

I love seals, and because I am a woman who loves seals, and loves mythology and folktales, merfolk and sea songs, I love selkies. I love them not for the tragic nature of their stories but because they are both human and seal.

Part of the utter core of the traditional selkie story is that the selkie, in the end, leaves. So naturally, my boyfriend, knowing I love both selkies and stories, started to become alarmed, thinking that I would leave him the same way. I told him our story was different, because I choose to be with him.

And that was when I realized that we all need a new selkie story, that our myths can guide us but not lock us: that there can be a new, variant myth, not to replace the old, but to give a sense of possibility, both for the relationships between lovers, and also humans and animals: to shine in the world in its newness.

The old selkie story has a basic, archetypal framework. Details swirl around and modify these fundamental components: a fisherman sees a mysterious woman emerge from a sealskin, at night on a beach, perhaps to dance with her kin under the moonlight or perhaps in her own private reverie. He falls in love with the sight and idea of her, and knowing by lore that she is a selkie, a seal woman, he knows that if her pelt is in his possession then she is under his rule. Without her skin she cannot return to the sea. So he steals and stashes her skin.

When she realizes her skin is missing she is distraught. He then reveals himself to her. She follows him home to be his wife. She apparently has no choice. Whether the woman is attracted to the fisherman or not, we are never told. He begets children on her, and they live a pleasant enough existence, but there is always something melancholy about her, an absence, a way of gazing yearningly towards the sea. One day, one of her children will discover something like an oilskin raincoat in a trunk in the attic, or stuffed into a notch in the eaves. Her son or daughter will ask her what it is. Her eyes will go wild with joy, and she will snatch her skin from him, clutch it to her breast, and say hasty farewells as she races to the beach. She cannot run fast enough for herself.

A Selkie Story © Kate Leiper 2009

A Selkie Story © Kate Leiper 2009Sometimes afterwards the selkie will keep watch on her family from the water, following their boats in the form of a seal: generations of descendants with webbed phalanges and distant expressions. Sometimes she is gone forever from the story, her husband pining away in regret.

But what if there were a new selkie story? One in which she chooses the man? One in which the man courts her, makes himself loveable to her, that she wants to come to him; that he loves her for being what she is, part seal, and knowing that, loves the wild part of her? And when she needs to, she runs to the ocean, pulls her skin back around her, swims with her family. She comes to back to land. Back and forth, as seals do anyway. While she is gone, he does man things.

The story has drama, just not the inevitability of failure. The crux of the new story is its inner quarrel, the bit of resistance in the man, her uncertainty with him, and the back-and-forthing within them that gives way to purer love. Such would be a new possibility, and a new way.

The old selkie story is both about the relationship between lovers, and our relationship to the wild. In the way that sometimes humans in our weakness try to control our loved ones, through manipulation, through emotional blackmail, sometimes even through abuse and coercion, because we fear that their independence means they will leave and betray us, or that their self-sovereignty implies faithlessness, in the same way we have been doing things wrong in regards to animals, and so have trapped ourselves: keeping animals in tanks, in enclosures, jars, bowls, corrals. We seldom do this out of purposeful cruelty, or even sheer profitable callousness, but so much oftener out of misguided love. So since the story is made of love, it is malleable, it can be reoriented, rewritten, redeemed.

What we love in wild animals is their wild nature, their otherness, but for some reason that is the first thing we want to take away from them. In our infancy, both historical and personal, we wanted to contain it. I don’t think we always took animals from distant lands and kept them in iron enclosures with concrete floors solely to display our dominance over the exotic and oriental: maybe that was part of it, but not all. Knowing what I know of humans, I suspect it is because we wanted to marvel at their beauty, and have it close by, without fully understanding that separating them from their environment would eventually kill them. A child who puts a mantis in a jam jar does not do that out of an impulse to dominate: she does it because she loves it, she wants to keep it, to behold its angular alien elegance under the holes she has punched in the jar lid. She does not know otherwise; her curiosity is ignorant of consequences, and she wants to hold the moment of that joy forever. She does not want it to be over.

We fear the moment the creature leaves us. We fear we will be left behind, that it will not choose us.

So instead of courting the selkie as a decent man would, the fisherman traps her. He takes away her ability to choose him and so his story ends tragically, because he stole her life. But if he had taken a chance of not being chosen, of being patient, of allowing her to come and go, she may actually have come to love him, and he would have continued to behold her in her true nature, not in a diminished form.

A Selkie Story © Kate Leiper 2009

A Selkie Story © Kate Leiper 2009Compelling is bad magic no matter how it’s done. Any savvy and sensitive magic-user knows that love-spells, with their undertones of binding, come with a price: which is their success. Their success is their curse. If you get what you think you want, you will never know whether you are freely loved, whether that person would have chosen you if you had not forced them. Forever, while you are with them, something gnaws at the underneath of you, the wrongness of what you have done, taken their free will, stowed their skin, and stolen a love that should have by rights been freely given. Although in my life I seem to insist on learning things the hard way, this sounds so utterly miserable for both parties that I have never even been tempted to test it. I have heard enough tell of those who have.

Forcing something against its nature is the dark side of tameness. If you have seen the children’s-book-like French movie Le Renard et l’Enfant, The Fox and the Child, you know that it is very frank about wildness versus tameness, and arguably the opposite of the fox-taming discussion in The Little Prince. The little girl grows to befriend and love a wild fox, but over the course of the movie you feel the dread of the inevitable drawing nearer, as the girl’s affections start to close in on the fox, like the collar-like scarf she puts around the fox’s neck. We sense what will happen when the protagonist finally lures the fox in her house. But again, like the fisherman in the selkie story, the girl does what she does out of yearning, out of wanting to keep.

In our culture, we used to collect nature without an afterthought, to stick it in iron cages, to make its sensitive and articulated paws walk on flat concrete surfaces, so that we could possess it. Increasingly, to do this seems so absurd, as though we are suddenly shaking ourselves awake: ‘What are we doing?’

In the last several years, and rising faster and faster, there has been an upwelling of consciousness, through the movies The Cove and Blackfish, about the high cost of keeping marine mammals in captivity: in human casualties and injuries, but also, quite spectacularly, awareness of the cost to the animals themselves: the trauma to their families, emotionally bonded in ways that we can only begin to comprehend, so much that their families are their very selves and taking someone out of the unit is like ripping off a body part, an unspeakable psychic torture that goes on and on. The collapse of their mighty Yet I sense that something is changing, and rapidly so. I don’t know quite what caused it, this waking-up, this critical mass, but something is indeed happening that can’t be denied anymore, or stopped: human people have begun to care more about animals for the animals’ own sake, through recognition of their intelligence and consciousness, and the implications of those. We are seeing them increasingly as other peoples, their own and different tribes, with their own perceptions and languages. A zoo mentality is giving way to a sanctuary mentality, a rehabilitation mentality. There is an urgency and impatience now for change. The change has already happened, and like the River Isen when the Ents break its dam in The Lord of the Rings, and release the river, consciousness comes rampaging through and cannot be re-contained. What has seen cannot be unseen, and what is known cannot be unknown.

All that remains is for reality to catch up with it. Rachel Clark, in a stunning essay in Psychology Today calls Blackfish a bellwether presaging “more than cetacean freedom. It foreshadows an urgent global uprising to set things right everywhere. We are seeing an international frenzy for justice.”

The selkie story calls out to us for justice in territories of personal and natural concerns, in both cases about power. And that is why we need a new story. One that explodes the old model of grabbing and holding and stealing life and freedom just because one wants it. One that celebrates the sovereignty of other beings, human or non-human. One that is a ballad of justice.

Myths live in us, in response to us. So the new selkie story is this: that we trust whom we love. That we try to win their love so that through their own agency they choose to be with us. That we be brave enough to gamble our fear of loss. That we accept that just because we want to possess a being, no matter how badly we want to keep it, its right to be sovereign over its own life will always outweigh our desire to possess it. That freedom will always trump desire. That we are responsible for protecting that freedom in one another, that it is never ours to take, by any means.

We can write a new selkie story, to coexist with the old. The old will continue to exist as an instruction manual of what not to do, a sorrow, a caution. We can chant this new one by driftwood fires, and the seals in their wildness can spyhop to listen, dark eyes regarding us from the night ocean. Or they can ignore us altogether, as is their right. But one thing is sure: except for their own private and tribal reasons, seals should never be sorrowful.

As I am standing by the seal tank, a little girl next to me says to her mother, ‘What are they dreaming about in there?’ Her mother answers, ‘I don’t know; what do you think?’ ‘I think they are dreaming of being back in the ocean,’ the little girl says firmly.

The new selkie story is already being written. The new world has already begun.

Harbor seal, © Ralph Pace

Harbor seal, © Ralph Pace Postscript: A song for pinnipedal people, seal and soul, clan and clade, Otariidae, Odobenidae, Phocidae, for all who have an ancestor who grabbed her sealskin and ran toward the waves. For women and men, and all other wild creatures:

Feist, ‘Sea Lion Woman’

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1l7xfuu8ja8http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Chcc_Ci36Vw

Published on January 24, 2014 00:46

January 20, 2014

Perilous seas in faerie lands forlorn

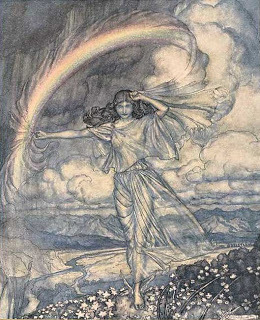

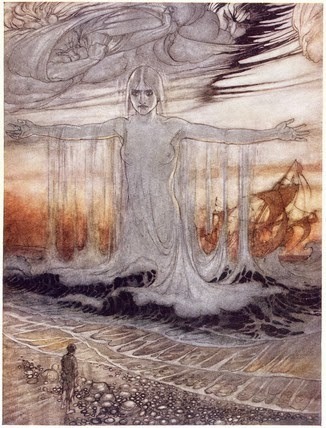

In this fabulous picture, Arthur Rackham depicts the beauty, vastness and terror of the sea as a white storm-goddess. There's a shipwreck behind her, and before her, dwarfed on the strand, is a bedraggled mariner who looks as though he very much ought to flee. She's the embodiment of the terrifying waves we've all been seeing photographed in the news over the last few weeks, like this one from the BBC website http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-25618080

It's at times like these that we're reminded of what our ancestors always knew: the sea is dangerous. We can walk along its edges, we can set out across it in our frail boats; we can even swim and dive in it, but always with a risk. We don't belong there, we can't live there. And so we're fascinated by the animals that do: we tell tales about them. The seals, so like ourselves: warm-blooded breathing mammals - surely they must be magical creatures, to be able to inhabit this place we can't survive in? We follow them in imagination into their strange underwater world. We make myths of mermaids and selkies.

Mermaids and selkies represent the Other – they look like humans but they aren’t, or perhaps they are only half human. In all the folklore I’ve read about mermaids, they have no souls, and sometimes they mourn this and sometimes they don’t care… Hans Andersen’s little mermaid will disappear like foam on the sea if she doesn’t win a soul: but when she does gain a soul, she stops being a mermaid. She becomes a spirit of the air, a sort of angelic Christian spirit – and so in either case she ceases to be, or at least loses her identity...

Most mermaid stories are sad. Some mermaids are actively dangerous. One Greek legend tells of a giant mermaid who rises out of the sea to demand of passing ships, ‘What news of King Alexander?’ Unless she receives the response, ‘He lives, and reigns, and conquers the world!’ she wrecks the ship in her fury. So mermaids are also a metaphor for the beauty and danger of the sea, which has the power to wreck ships and take men’s lives. There’s a lot going on in mermaid stories.

All fiction is affected by contemporary concerns. Hans Christian Andersen’s ‘Little Mermaid’ was concerned with salvation because he wrote in a highly Christian century. Nowadays, in our multi-cultural, multi-faith, multi-everything society, I think writing about mermaids offers an opportunity to explore issues of trust and communication between individuals who may look different from one another, who may appear to come from different worlds. What is it to be ‘human’? How do we define it? How do we recognise similarities and reconcile differences? In very different ways, Liz Kessler’s 'Emily Windsnap' books and Helen Dunmore’s ‘Ingo’ and its sequels explore these questions, as well as issues of pollution and climate change. In 'Ingo', merfolk and humans were once one people, who have diverged and now live in separate worlds - except that each race still impacts the other. Liz Kessler's 'Emily Windsnap' is a little girl who herself bridges the gap: her father is mer, her mother human. To which world does she belong? Is it always necessary to choose?

And what about the original legends, such as the Cornish Mermaid of Zennor or the Scottish selkie and kelpie stories? The legends are tremendously inspiring - but you have to think about them, find out what they are saying to you. I wrote about the selkies, the shape-shifting seal people, in ‘Troll Mill’, the second part of my trilogy ‘West of the Moon’. The legend is of a fisherman who sees the selkies dancing on the moonlit beach in the form of lovely women, and he snatches up one of their discarded sealskins so that the selkie girl can’t escape into the sea. She has to marry him and bear his children, but one day she finds where he’s hidden the sealskin. At once she throws it on, returns to the sea and abandons him and her human (half-human?) children forever.

For me, this legend seemed to be about the difficulty of understanding one another, even in a bond as close as marriage – in a sense, one’s partner is always the Other. It speaks of the power struggle between couples – and the grief of a failed partnership – and, very strongly I thought, about the new mother’s plunge into post-natal depression. And that was how I used it in my book, though keeping the magic and lyricism. In my short mermaid book ‘Forsaken’, the human-mer partnership is the other way around, based on an old Scandinavian ballad about a Mer-king who marries a mortal woman, and one day she hears the church bells ringing above the sea, and goes back to the land and leaves him forever. Rarely in folklore do these stories end happily. But I read the legend, and my spine tingled, and I wanted to see what would happen if one of the half-mer children went looking for her mother… Would the ending be different?

Margo Lanagan, in ‘The Brides of Rollrock Island’ (Australian title 'Sea Hearts') has found something quite different in the selkie legends (see her post and my review). In her book, the seals are manipulated and transformed in a way which denies their nature and damages the wrongdoers. It’s a marvellous book which will keep me thinking for – I suspect – years. The beautiful women who step out of the seal carcasses appear, to the rough island men who have obtained them like mail-order brides, to be the culmination of delight: but they and their sons must live year in, year out, bearing the guilt of the seal women’s ever-present mild but steadfast grief.

Franny Billingsley’s ‘The Folk Keeper’ is another story which is concerned with questions of identity and belonging, a wonderfully creepy take on the selkie legend. And Gillian Philip’s ‘Firebrand’ and ‘Bloodstone’ include not only selkies, as sinister death-omens, but her heroes of the Sithe, the Scottish faeries, ride kelpies too (water horses from the lochs): sleek and dangerous and man-eating. Kelpies appear again in Maggie Stiefvater’s wonderful ‘The Scorpio Races’, an evocative and thrilling story of racing the savage water horses on a wild Scottish island. Should men take and attempt to tame these otherworldly creatures? Is it courage or cruelty? Should they, perhaps, be left to their own world and their own nature?

These are all strong, wonderfully written books. If you feel like taking a plunge into the perilous seas of fairyland, do try them! And on Friday, the blog will continue to explore the selkie theme with a guest post from Laura Marjorie Miller.

Published on January 20, 2014 02:24

January 10, 2014

Faerie cities

This wonderful little city stands as if sprung from the soil, in a neighbour's garden. It reminds me of the medieval French city of Carcassonne, whose name was used by Lord Dunsany for a faerie city in one of his tales; though rather oddly he seems to have picked the name from a reference in a friend's letter and never to have known it is the name of a real place.:

Some had heard of it in speech or song; some had read of it and some had dreamed of it. ...Far away it was, and far and far away, a city of gleaming ramparts rising one over the other, and marble terraces behind the ramparts, and fountains shimmering on the terraces. To Carcassonne the elf-kings with their fairies had first retreated from men, and had built it on an evening late in May by blowing their elfin horns. Carcassonne! Carcassonne!

This little fairy city - for me - irresistably conjures a beautiful poem of Kipling's, from 'Puck of Pook's Hill'.

CITIES and Thrones and Powers

Stand in Time's eye,

Stand in Time's eye,Almost as long as flowers,

Which daily die:

Which daily die:But, as new buds put forth

To glad new men,

To glad new men,Out of the spent and unconsidered Earth,

The Cities rise again.

The Cities rise again.This season's Daffodil,

She never hears,

She never hears,What change, what chance, what chill,

Cut down last year's;

Cut down last year's;But with bold countenance,

And knowledge small,

And knowledge small,Esteems her seven days' continuance

To be perpetual.

To be perpetual.So Time that is o'er-kind

To all that be,

To all that be,Ordains us e'en as blind,

As bold as she:

As bold as she:That in our very death,

And burial sure,

And burial sure,Shadow to shadow, well persuaded, saith,

"See how our works endure!"

"See how our works endure!"

Published on January 10, 2014 01:30

January 4, 2014

In The Library of Imaginary Books

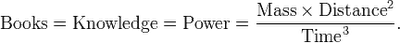

Deep in the enclaves of Unseen University (in Terry Pratchett’s Discworld novels, in case anyone reading this doesn’t already know) is the University Library, where the presence of so many books has warped space into a mysterious form called L-space (or Library-space) expressed by the equation:

Books are entrances into other worlds: in UU Library this is not a metaphor. And, a consequence of the properties of L-space, the shelves contain every book ever written, unwritten or yet to be written. Terry Pratchett's UU Library is thus - probably - different from Jorge Luis Borges' Biblioteca de Babel, in which the books additionally contain every possible combination of the letters of the alphabet - and are therefore mostly gibberish.

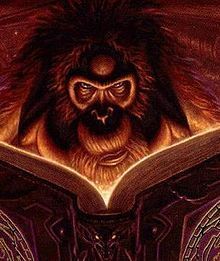

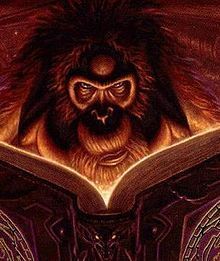

Librarian of the Discworld as he appears in

The Discworld Companion

, illustrated by Paul Kidby

Librarian of the Discworld as he appears in

The Discworld Companion

, illustrated by Paul Kidby

The Babel library would be a bad place to work. I would like, therefore (if I have the Librarian’s permission), to take you on a small tour of UU library, concentrating on a section I often like to visit: the section for Imaginary Books. These, of course, are books which exist only between the covers of other books and are therefore fictional to the power two: fiction². I’ve delighted in many such titles over the years, so let’s tiptoe past the chained, uneasily-slumbering grimoires of UU Library’s extensive magical sections, and I’ll show you my favourites.

The first is ‘The Orange and the Apple’, which exists between the covers of Arthur C Clarke’s ‘A Fall of Moondust’, the story of a ‘moon-bus’ full of passengers which plunges into the deep soft dust of the Sea of Tranquillity following a moon-quake. During the desperate rescue operation which ensues, the trapped passengers organise an entertainment to keep their minds off claustrophobia and the fear of death. It may not be one of Clarke’s best-known novels, but it contains some good character sketches and is often very funny. The passengers take turns reading aloud the only two novels on board, Jack Schaefer’s classic western ‘Shane’ and a ‘new historical romance’ ‘The Orange and the Apple’, featuring an affair between Sir Isaac Newton and Nell Gwynne. Let me reach it down from the shelf for you: a cheap paperback with a lurid cover and a cracked spine:

The author certainly wasted no time. Within three pages, Sir Isaac Newton was explaining the law of gravitation to Mistress Gwynne, who had already hinted that she would like to do something in return.

…“Forsooth, Sir Isaac, you are indeed a man of great knowledge. Yet, methinks, there is much that a woman might teach you.”

“And what is that, my pretty maid?”

Mistress Nell blushed shyly.

“I fear,” she sighed, “that you have given your life to the things of the mind. You have forgotten, Sir Isaac, that the body, also, has much strange wisdom.”

“Call me ‘Ike’,” said the sage huskily, as his clumsy fingers tugged at the fastenings of her blouse.

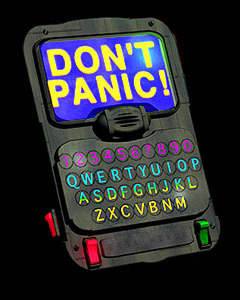

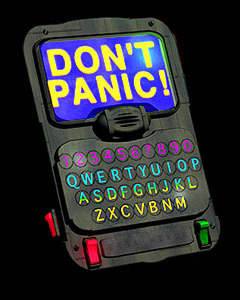

Close beside this on the shelves is an array of titles from Douglas Adams’ ‘The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy’. There’s the Guide itself, of course, clearly an e-book on an e-reader:

…a device which looked rather like a largish electronic calculator. This had about a hundred tiny press buttons and a screen about four inches square on which any one of a million ‘pages’ could be summoned at a moment’s notice. It looked insanely complicated, and this was one of the reasons why the snug plastic cover it fitted into had the words DON’T PANIC printed on it in large friendly letters.

That was written in the late 1970’s, so you can see the power of L-space right there. Next to the Guide is an entire bookcase sagging beneath the weight of the many volumes of the Encyclopaedia Galactica. Oh, and here are a couple of paperbacks which look to have been much thumbed by the wizards of Unseen University - so long as they’re sure no other wizard is watching: Eccentrica Gallumbits’ ‘The Big Bang Theory, A Personal View’, and ‘Everything You Never Wanted to Know About Sex But Have Been Forced To Find Out’. Next on the shelf - in a far more pristine condition - is Oolon Colluphid’s galaxy-rattling series of popular theological texts: ‘Where God Went Wrong’, ‘Some More of God’s Greatest Mistakes’, ‘Who Is This God Person Anyway?’ and ‘Well That About Wraps It Up For God’.

If you’re not interested in science, or philosophy, we can move on to the literary biographies. Here's one I’ve always wanted to read: ‘Pard-Spirit: A Study of Branwell Brontë’ by one Mr Mybug - nestling within the pages of Stella Gibbons’ ‘Cold Comfort Farm’. It’s a handsome looking hardback. I suspect he had to pay for its publication, but he made sure there was a large and arty black and white photograph of himself on the back of the dust jacket.

‘It’s goin’ to be dam good,’ said Mr Mybug. ‘It’s a psychological study, of course, and I’ve got a lot of new matter, including three letters he wrote to an old aunt in Ireland, Mrs Prunty, during the period when he was working on Wuthering Heights.’ He glanced sharply at Flora to see if she would react.

‘It’s obvious that it’s his book and not Emily’s. No woman could have written that. It’s male stuff… Secretly, he worked twelve hours a day writing Shirley and Villette - and of course, Wuthering Heights. I’ve proved all this by evidence from the three letters to old Mrs Prunty. His letters to her are little masterpieces of repressed passion. They’re full of tender little questions… he asks her how is her rheumatism… has her cat, Toby, “recovered from the fever”… … how is Cousin Martha (and what a picture we get of Cousin Martha in those simple words, a raw Irish chit, high-cheekboned, with limp black hair and clear blood in her lips!) …’

Delicious!

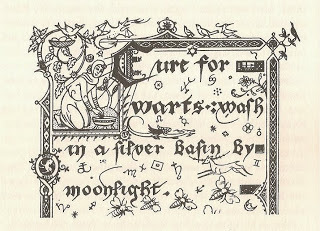

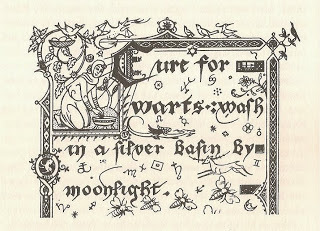

Oh look - here, bound in leather and lying on a slanting wooden stand, is the Magician's Book from the 'The Voyage of the Dawn Treader'! I flick back the two lead clasps which hold it shut, and lift open the cover to reveal beautiful illuminated vellum pages filled with spells -

cures for warts (by washing your hands by moonlight in a silver basin) and toothache and cramp, and a spell for taking a swarm of bees...

... how to find buried treasure, how to remember things forgotten, how to forget things you wanted to forget, how to tell whether anyone was speaking the truth...

Dangerous stuff, all of it. I can see you're taking a little bit too much interest, so I close the cover and fasten the clasps (the book tingles and buzzes under my fingers as I do so) and we move on.

Ah! Here, sticking quite a long way out from the shelf and leaning slantwise to fit, is a tall folio manuscript bound in a red leather cover. The catalogue label coming unstuck from the spine reads: 'Travel: Imaginary'. I pull it tenderly out. Odd though it may seem, this could be the most valuable book in the entire section. It's written 'in a wandering hand' in spiky black ink with lots of curlicues. The title page has many titles on it, crossed out one after another: so:

My Diary. My Unexpected Journey. There and Back Again. And What Happened After. Adventures of Five Hobbits. The Tale of the Great Ring, compiled by Bilbo Baggins from his own observations and those of his friends. What We Did in the War of the Ring.

Here Bilbo's hand ends, and Frodo has written:

THE DOWNFALL OF THE LORD OF THE RINGS AND THE RETURN OF THE KING'.

Bilbo and Frodo's own autobiographical account! I know you'd love to stand here and leaf through it, but today I'm just showing you what's on the shelves, and we haven't time. You can come back by yourself another day.

How do you fancy Victorian poetry? Courtesy of A S Byatt’s ‘Possession’, allow me to pull out this stout green book, the ‘Collected Poems of Randolph Henry Ash’ including of course ‘The Garden of Proserpina’ and ‘Ask to Embla’ -

No? Then how about my own preference, this slim volume in limp violet suede, with faded spine and curling corners, whose embossed gold title reads simply ‘The Fairy Melusine’ by Christabel LaMotte, a writer who owes a clear debt to Emily Dickinson. As we pluck it from the shelf, out flutters a loose manuscript sheet with a poem on it:

It came all so still

The little Thing -

And would not stay -

Our Questioning -

A heavy Breath -

One two and three -

And then the lapsed Eternity -

A Lapis Flesh

The Crimson - Gone -

It came as still

As any Stone -

Is there anything you'd like to see that I haven't shown you? It'll be here. Just let me know...

Books are entrances into other worlds: in UU Library this is not a metaphor. And, a consequence of the properties of L-space, the shelves contain every book ever written, unwritten or yet to be written. Terry Pratchett's UU Library is thus - probably - different from Jorge Luis Borges' Biblioteca de Babel, in which the books additionally contain every possible combination of the letters of the alphabet - and are therefore mostly gibberish.

Librarian of the Discworld as he appears in

The Discworld Companion

, illustrated by Paul Kidby

Librarian of the Discworld as he appears in

The Discworld Companion

, illustrated by Paul KidbyThe Babel library would be a bad place to work. I would like, therefore (if I have the Librarian’s permission), to take you on a small tour of UU library, concentrating on a section I often like to visit: the section for Imaginary Books. These, of course, are books which exist only between the covers of other books and are therefore fictional to the power two: fiction². I’ve delighted in many such titles over the years, so let’s tiptoe past the chained, uneasily-slumbering grimoires of UU Library’s extensive magical sections, and I’ll show you my favourites.

The first is ‘The Orange and the Apple’, which exists between the covers of Arthur C Clarke’s ‘A Fall of Moondust’, the story of a ‘moon-bus’ full of passengers which plunges into the deep soft dust of the Sea of Tranquillity following a moon-quake. During the desperate rescue operation which ensues, the trapped passengers organise an entertainment to keep their minds off claustrophobia and the fear of death. It may not be one of Clarke’s best-known novels, but it contains some good character sketches and is often very funny. The passengers take turns reading aloud the only two novels on board, Jack Schaefer’s classic western ‘Shane’ and a ‘new historical romance’ ‘The Orange and the Apple’, featuring an affair between Sir Isaac Newton and Nell Gwynne. Let me reach it down from the shelf for you: a cheap paperback with a lurid cover and a cracked spine:

The author certainly wasted no time. Within three pages, Sir Isaac Newton was explaining the law of gravitation to Mistress Gwynne, who had already hinted that she would like to do something in return.

…“Forsooth, Sir Isaac, you are indeed a man of great knowledge. Yet, methinks, there is much that a woman might teach you.”

“And what is that, my pretty maid?”

Mistress Nell blushed shyly.

“I fear,” she sighed, “that you have given your life to the things of the mind. You have forgotten, Sir Isaac, that the body, also, has much strange wisdom.”

“Call me ‘Ike’,” said the sage huskily, as his clumsy fingers tugged at the fastenings of her blouse.

Close beside this on the shelves is an array of titles from Douglas Adams’ ‘The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy’. There’s the Guide itself, of course, clearly an e-book on an e-reader:

…a device which looked rather like a largish electronic calculator. This had about a hundred tiny press buttons and a screen about four inches square on which any one of a million ‘pages’ could be summoned at a moment’s notice. It looked insanely complicated, and this was one of the reasons why the snug plastic cover it fitted into had the words DON’T PANIC printed on it in large friendly letters.

That was written in the late 1970’s, so you can see the power of L-space right there. Next to the Guide is an entire bookcase sagging beneath the weight of the many volumes of the Encyclopaedia Galactica. Oh, and here are a couple of paperbacks which look to have been much thumbed by the wizards of Unseen University - so long as they’re sure no other wizard is watching: Eccentrica Gallumbits’ ‘The Big Bang Theory, A Personal View’, and ‘Everything You Never Wanted to Know About Sex But Have Been Forced To Find Out’. Next on the shelf - in a far more pristine condition - is Oolon Colluphid’s galaxy-rattling series of popular theological texts: ‘Where God Went Wrong’, ‘Some More of God’s Greatest Mistakes’, ‘Who Is This God Person Anyway?’ and ‘Well That About Wraps It Up For God’.

If you’re not interested in science, or philosophy, we can move on to the literary biographies. Here's one I’ve always wanted to read: ‘Pard-Spirit: A Study of Branwell Brontë’ by one Mr Mybug - nestling within the pages of Stella Gibbons’ ‘Cold Comfort Farm’. It’s a handsome looking hardback. I suspect he had to pay for its publication, but he made sure there was a large and arty black and white photograph of himself on the back of the dust jacket.

‘It’s goin’ to be dam good,’ said Mr Mybug. ‘It’s a psychological study, of course, and I’ve got a lot of new matter, including three letters he wrote to an old aunt in Ireland, Mrs Prunty, during the period when he was working on Wuthering Heights.’ He glanced sharply at Flora to see if she would react.

‘It’s obvious that it’s his book and not Emily’s. No woman could have written that. It’s male stuff… Secretly, he worked twelve hours a day writing Shirley and Villette - and of course, Wuthering Heights. I’ve proved all this by evidence from the three letters to old Mrs Prunty. His letters to her are little masterpieces of repressed passion. They’re full of tender little questions… he asks her how is her rheumatism… has her cat, Toby, “recovered from the fever”… … how is Cousin Martha (and what a picture we get of Cousin Martha in those simple words, a raw Irish chit, high-cheekboned, with limp black hair and clear blood in her lips!) …’

Delicious!

Oh look - here, bound in leather and lying on a slanting wooden stand, is the Magician's Book from the 'The Voyage of the Dawn Treader'! I flick back the two lead clasps which hold it shut, and lift open the cover to reveal beautiful illuminated vellum pages filled with spells -

cures for warts (by washing your hands by moonlight in a silver basin) and toothache and cramp, and a spell for taking a swarm of bees...

... how to find buried treasure, how to remember things forgotten, how to forget things you wanted to forget, how to tell whether anyone was speaking the truth...

Dangerous stuff, all of it. I can see you're taking a little bit too much interest, so I close the cover and fasten the clasps (the book tingles and buzzes under my fingers as I do so) and we move on.

Ah! Here, sticking quite a long way out from the shelf and leaning slantwise to fit, is a tall folio manuscript bound in a red leather cover. The catalogue label coming unstuck from the spine reads: 'Travel: Imaginary'. I pull it tenderly out. Odd though it may seem, this could be the most valuable book in the entire section. It's written 'in a wandering hand' in spiky black ink with lots of curlicues. The title page has many titles on it, crossed out one after another: so:

My Diary. My Unexpected Journey. There and Back Again. And What Happened After. Adventures of Five Hobbits. The Tale of the Great Ring, compiled by Bilbo Baggins from his own observations and those of his friends. What We Did in the War of the Ring.

Here Bilbo's hand ends, and Frodo has written:

THE DOWNFALL OF THE LORD OF THE RINGS AND THE RETURN OF THE KING'.

Bilbo and Frodo's own autobiographical account! I know you'd love to stand here and leaf through it, but today I'm just showing you what's on the shelves, and we haven't time. You can come back by yourself another day.

How do you fancy Victorian poetry? Courtesy of A S Byatt’s ‘Possession’, allow me to pull out this stout green book, the ‘Collected Poems of Randolph Henry Ash’ including of course ‘The Garden of Proserpina’ and ‘Ask to Embla’ -

No? Then how about my own preference, this slim volume in limp violet suede, with faded spine and curling corners, whose embossed gold title reads simply ‘The Fairy Melusine’ by Christabel LaMotte, a writer who owes a clear debt to Emily Dickinson. As we pluck it from the shelf, out flutters a loose manuscript sheet with a poem on it:

It came all so still

The little Thing -

And would not stay -

Our Questioning -

A heavy Breath -

One two and three -

And then the lapsed Eternity -

A Lapis Flesh

The Crimson - Gone -

It came as still

As any Stone -

Is there anything you'd like to see that I haven't shown you? It'll be here. Just let me know...

Published on January 04, 2014 02:14

December 21, 2013

The Girl Who Followed the North Star

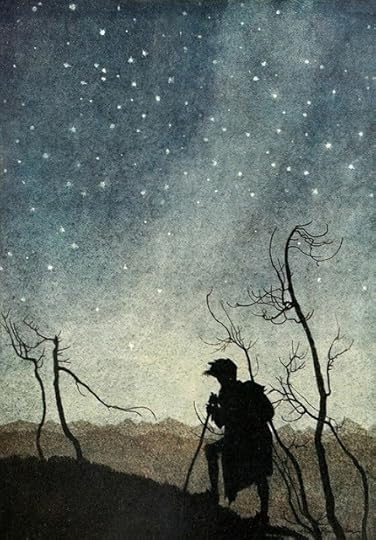

It is a northern land, a hard place where the trees bend always to a cold, flowing wind. At night the north star flashes and beckons, a jewelled finger. The skies turn like a dial, so big and remote… A child lived there who thought how huge everything was, and was afraid of the emptiness between stars and beyond stars. But her grandmother whispered, “There’s nothing to be afraid of. Don’t you know the whole universe is knotted up in a handkerchief in God’s pocket?” So the child grew up fearless. Often she spent her nights wandering on the high moors with a stick of yew in her hand, calling the owls, who would whirr down in a soft blur of feathers and clutch her arm, turning their black brilliant eyes here and there. But as sunrise streaked the sky she would be back at the cottage to blow the fire aflame and put the kettle on the hob and kiss her grandmother awake. Then her grandmother died and was buried. After the funeral, the young girl sat alone in the cold cottage and cried. “Grandmother, where have you gone? Why have you left me? How can I find you?” And each night she wandered further and further afield, following the bright beckoning of the North Star, axle of the sky, till she came to the country where it is always dark and day is no more than winter twilight, even at noon. Underfoot was heather, and black bilberries, and withered bracken. One night she came over a ridge and saw a lake lying beneath her. Its waters were still and dark and very cold, and it lapped a shore of granite pebbles that glinted in the starlight. And, straining her eyes, she thought she saw the dim loom of an island far out in the lake, and at once she was overcome with longing to set foot on it, but there were no boats on the shore, and the water was too cold to enter. It would have frozen her heart. And it seemed the North Star shone directly over the island, tugging her towards it. Three times the stars wheeled overhead as she walked along the shore, watching the dark shape of the island sleeping on the water, and in all this time she saw no more than a quick meteor threading the high heaven, and heard no more than the crunch of her own footsteps and the knock of her staff striking the shingle. At last she came to a beach where, scattered here and there in the rough gravel, were round pebbles that glowed like tiny moons; and an old man sat huddled on the shore beside his boat, a patched old leather coracle. He was staring at the ground, but when he heard the young woman coming he scrambled up, crying, “Go away, go away. All this is mine!” “What do you mean? I only want you to lend me your coracle so that I can cross over to the island.” “Island? What island?” asked the old man. Then he looked cunning, and counted on his fingers, and mumbled to himself, and said, looking up, “You must pay me for the use of my coracle.” “I have no money,” she said. “But I will work for you.” The old man set her to pick up all of the glowing pebbles and heap them near the coracle. Under the turning sky the girl went back and forth, collecting the stones till her hands were cold and bruised, but although the pile grew higher and higher, the old man was never satisfied. Soon all the shingle close by was dull, while the pile beside the coracle shone like a white beacon. She was so stiff she wondered if she would ever be able to straighten up again, but still she had to go to and fro, and each time she asked for the coracle, the old man shook his head. Finally she went back and threw the last stones on the high pile. “I have done enough.” “Not yet, not yet,” said the old man, groping in the heap. “Yes; if you do not give me the boat now, I will take it – I have earned it! – and I will crack your head into the bargain.” The old man turned to her then and put two stones into her hand – but at the last moment he snatched one back – saying, “The coracle leaks and will not float. These are opals. Take your fee and go.” “Row me over,” the girl demanded, throwing the jewel down. But because the old man moaned and clutched at his dead heap she lowered her stick, saying, “You would do better as an honest fisherman, I think,” and dragged the coracle into the water, which lapped her foot and seeped into her shoe, so cold that she gasped. She climbed in and poled off with her stick, then took up the paddle and began to make her way towards the darkness that lay on the centre of the water, just showing an island’s shape against the star-prickled sky. The leather sides of the coracle were cracked and dry, and the cold water welled in so that she had to stop paddling and bail with cupped hands till they stung and ached with cold. At last the leather swelled with the moisture and the cracks were closed. Then she picked up the paddle and went on. Slowly the island drew nearer, and larger, until she was working into a little bay where small, gnarled trees grew right against the water and leaned out above it. She grasped their branches and pulled herself out of the boat, and they shook bitter bark down into her face and hair, and her fingers were sticky with resin. Slowly she hobbled inland with bent back and frozen hands, and she blundered in the darkness, for gall and bark were stinging her eyes. But she dragged herself uphill, tearing her skin on brambles, till she reached a high mound in the centre of the island, free from trees and bushes, covered with short, dry grass. At the top of the mound she drove her staff into the turf and sat down beneath it and wept in the cold air, and the tears washed the bark from her eyes and splashed warm on her hands, watering the ground with salt. And when she looked up there was the north star, straight overhead, brighter than she had ever seen it.And the stick at her back rooted, and put out dark leaves and small white flowers.

Copyright Katherine Langrish 2013

Illustration by Arthur Rackham: 'The Wilderness Under the Stars' (cabinetparticulier: via seirinko-deactivated20130402)

Published on December 21, 2013 04:16

December 13, 2013

How To Develop A Story (by Lewis Carroll)

This is something I've always wanted to share with you. It's a piece called 'Photography Extraordinary' written by Lewis Carroll for one of the home-made family newspapers he wrote and illustrated, The Rectory Umbrella and Mischmasch. It was published in the Illustrated News of Jan 28 1860, five years before the publication of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland - when Carroll was twenty-eight.

It's very funny. I recognise both his satirical claim that writing a novel could, via some technical advance, become a mere 'mechanical labour' - and the comment about the first example being 'utterly unsaleable in the present day'. Plus ça change. In amongst the fun, however, are several lessons for the aspiring writer. For example, the same plot elements can be worked very differently. And if your work is dull, you may need to develop it...

Getting into the spirit of the the thing, I thought I should use different intensities of colour to highlight his point. Allow me to reproduce, without further ado, Lewis Carroll's

Photography Extraordinary!

The recent extraordinary discovery in Photography, as applied to the operations of the mind, has reduced the art of novel-writing to the merest mechanical labour. We have kindly been permitted by the artist to be present during one of his experiments.

The operator began by stating that the ideas of the feeblest intellect, when once received on properly prepared paper, could be ‘developed’ up the highest intensity. He … summoned a young man from an adjoining room, who appeared to be of the very weakest possible physical and mental powers. … The machine being in position and a mesmeric rapport established between the mind of the patient and the object glass … [he] at once commenced the operation.

After the paper had been exposed for the requisite time, it was removed and submitted to our inspection; we found it to be covered in faint and almost illegible characters. A closer scrutiny revealed the following:-

“The eve was soft and dewy mild; a zephyr whispered in the lofty glade, and a few light drops of rain cooled the thirsty soil. At a slow amble, along a primrose-bordered path, rode a gentle-looking and amiable youth, holding a light cane in his delicate hand; the pony moved gracefully beneath him, inhaling as it went the fragrance of the roadside flowers: the calm smile, and languid eyes, so admirably harmonising with the fair features of the rider, showed the even tenor of his thoughts. With a sweet, though feeble voice, he plaintively murmured out the gentle regrets that clouded his breast:

‘Alas! She would not hear my prayer!Yet it were rash to tear my hair;Disfigured, I should be less fair.

She was unwise, I may say blind;Once she was lovingly inclined;Some circumstance has changed her mind.’

There was a moment’s silence; the pony stumbled over a stone in the path, and unseated his rider. A crash was heard among the dried leaves; the youth arose; a slight bruise on his left shoulder, and the disarrangement of his cravat, were the only traces that remained of this trifling accident.”

“This,” we remarked as we returned the papers, “belongs apparently to the Milk and Water School of Novels.” “You are quite right,” our friend replied, “and, in its present state, it is of course utterly unsaleable in the present day: we shall find, however, that the next stage of development will remove it into the strong-minded or Matter-of-Fact School.” After dipping it into various acids, he again submitted it to us: it had now become the following: -

“The evening was of the ordinary character; barometer at ‘change’: a wind was getting up in the wood, and some rain was beginning to fall; a bad look-out for the farmers. A gentleman approached along the bridle-road, carrying a stout knobbed stick in his hand, and mounted on a serviceable nag, possibly worth some £40 or so; there was a settled business-like expression on the rider’s face, and he whistled as he rode; he seemed to be hunting for rhymes in his head, and at length repeated, in a satisfied tone, the following composition:-

‘Well! so my offer was no go!She might do worse, I told her so;She was a fool to answer ‘No’.

However, things are as they stood;Now would I have her if I could,For there are plenty more as good.’

At this moment the horse set his foot in a hole, and rolled over; his rider rose with difficulty; he had sustained several severe bruises, and fractured two ribs; it was some time before he forgot that unlucky day.”

We returned this with the strongest expression of admiration, and requested it might now be developed to the highest possible degree. Our friend readily consented, and shortly presented us with the result, which he informed us belonged to the Spasmodic or German School. We perused it with indescribable sensations of surprise and delight.

“The night was wildly tempestuous – a hurricane raved through the murky forest – furious torrents of rain lashed the groaning earth. With a headlong rush – down a precipitous mountain gorge – dashed a mounted horseman armed to the teeth – his horse bounded beneath him at a mad gallop, snorting fire from its distended nostrils as it flew. The rider’s knotted brows – rolling eyeballs – and clenched teeth – expressed the intense agony of his mind – weird visions loomed upon his burning brain – while with one mad yell he poured forth the torrent of his burning passion:-

‘Firebrands and daggers! hope hath fled!To atoms dash the double dead!My brain is fire – my heart is lead!

Her soul is flint – and what am I?Scorch’d by her fierce relentless eye,Nothingness is my destiny!’

There was a moment’s pause. Horror! his path ended in a fathomless abyss - *** A rush – a flash – a crash – all was over. Three drops of blood, two teeth and a stirrup were all that remained to tell where the wild horseman met his doom.”

Our friend concluded with various minor experiments, such as working up a passage of Wordsworth into strong, sterling poetry: the same experiment was tried on a passage of Byron, at our request, but the paper came out scorched and blistered by the fiery epithets thus produced.

Picture credit:Lewis Carroll, self portrait, circa 1856 Wikimedia Commons

Published on December 13, 2013 03:53