Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 21

April 6, 2016

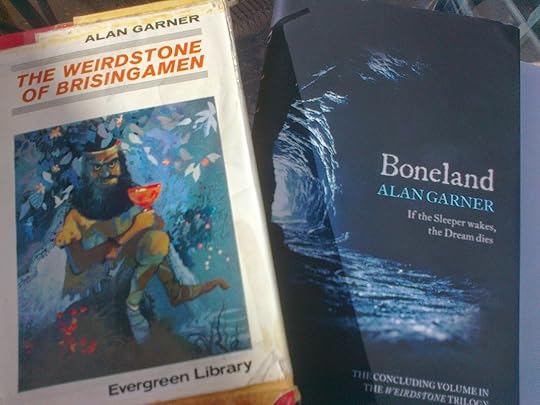

Folklore snippets: The River-Man

‘A Strömkarl sings…’ One of the many strange creatures in Alan Garner's wonderful children's fantasy 'The Weirdstone of Brisingamen' is the strömkarl which the children and the dwarfs hear playing on the Goldenstone as they emerge from the constrictive darkness of the Earldelving:

He was less than three feet high; his skin lustrous as a pearl; his hair rippling to his waist in green sea-waves. And the sad melody ran beneath his fingers like the song of water over pebbles.

Of course I didn't know, when I first read that as a child, that 'strömkarl' simply means 'river man'. He is one of the river-spirits of Scandinavia, who are as numerous and varied as the rivers themselves. Strömkarls and Neckans often sing beautifully, or play on harps, and the latter is sometimes heard grieving that he will never have eternal life. The Neckan or Nökken has a tendency to call to people and lure them into the water. The River-horse or Bäck-hästen is similar to the Scottish kelpie: once you mount on his back, he will dash into the water and try to drown you.

Fittingly, all these creatures are fluid: they shape-change. The Nök sometimes takes River-horse form, or may appear in the shape of a little, bearded man: the Strömkarl may assume the likeness of your lover or friend.

The River-Man (the Strömkarl or Neckan)

Like the trolls and the wood-fairies, the river-man belongs to the fallen angels, and like these he also desires to play wicked pranks on mankind, so he changes his shape at pleasure. A story is told of a young girl who engaged herself to an agreeable young man, and the two were in the habit of meeting beside a stream. The river-man took advantage of this, put on the shape of her betrothed, and met the girl several times. She found, however, that he behaved differently from his usual conduct, and complained to her parents. These suspected mischief, and told her that the next time she met him, she should pretend to be very friendly with him, and so get out of him the way to protect herself against the river-man. She took their advice, and he was foolish enough to say to her, that whoever carried on their person, ‘wall-stone, sausage-bone, and the white under ground,’ would be safe from him. The girl then searched for a stone from a clay-covered house wall, a bone-splinter from a meat-sausage, and a garlic-root; these she carried about with her, and so put an end to his tricks.

The river-man plays music in the rivers and streams. His music is wondrously beautiful to hear, but dangerous to listen to, for one can lose their senses by standing and hearing the dance to the end. Many village musicians have been known,who have learned from him to play this elf-dance, and have sometimes played the first parts of it at Christmas parties and elsewhere. This might be done without any danger to themselves or to the dancers, but if the player had not sense enough to stop at the end of the third part, but began the fourth and last , then it was too late. At the third part both old and young danced like mad, but now the musician and tables and benches dances as well, and could not stop so long as life was in the people, unless someone from outside entered the room and cut all the strings of the violin across with a knife.

Scandinavian Folk-Lore, ed. William Craigie, 1896

In one of the most famous stories, the river-man is rebuked by a passing priest who jeers at him, 'How can you play such music, knowing you have no soul? Sooner shall this stick of mine burst into flower than the Neckan receive God's mercy and eternal life.' Weeping bitterly, the poor Neckan throws his harp aside: within a few paces, however, the priest's staff bursts into sudden blossom and, shamed by the miracle, the priest confesses that God's mercy extends to all his creatures. In this poem the Victorian poet Matthew Arnold (who seems to have loved Scandinavian folklore) imagines the Neckan's response. (Turning this particular Neckan into a Sea King who has married a mortal woman, Arnold has blended it with the ballad of Agnete and the Merman which inspired his long poem 'The Forsaken Merman'.)

In summer, on the headlands,The Baltic Sea along,Sits Neckan with his harp of gold,And sings his plaintive song.

Green rolls beneath the headlands,Green rolls the Baltic Sea;And there, below the Neckan’s feet,His wife and children be.

He sings not of the ocean,Its shells and roses pale;Of earth, of earth the Neckan sings,He hath no other tale.

He sits upon the headlands,And sings a mournful staveOf all he saw and felt on earthFar from the kind sea-wave.

Sings how, a knight, he wander’dBy castle, field, and town—But earthly knights have harder heartsThan the sea-children own.

Sings of his earthly bridal—Priest, knights, and ladies gay.“—And who art thou,” the priest began,“Sir Knight, who wedd’st to-day?”—

“—I am no knight,” he answered;“From the sea-waves I come.”—The knights drew sword, the ladies scream’d,The surpliced priest stood dumb.

He sings how from the chapelHe vanish’d with his bride,And bore her down to the sea-halls,Beneath the salt sea-tide.

He sings how she sits weeping‘Mid shells that round her lie.“—False Neckan shares my bed,” she weeps;“No Christian mate have I.”—

He sings how through the billowsHe rose to earth again,And sought a priest to sign the cross,That Neckan Heaven might gain.

He sings how, on an evening,Beneath the birch-trees cool,He sate and play’d his harp of gold,Beside the river-pool.

Beside the pool sate Neckan—Tears fill’d his mild blue eye.On his white mule, across the bridge,A cassock’d priest rode by.

“—Why sitt’st thou there, O Neckan,And play’st thy harp of gold?Sooner shall this my staff bear leaves,Than thou shalt Heaven behold.”—

But, lo, the staff, it budded!It green’d, it branch’d, it waved.“—O ruth of God,” the priest cried out,“This lost sea-creature saved!”

The cassock’d priest rode onwards,And vanished with his mule;But Neckan in the twilight greyWept by the river-pool.

He wept: “The earth hath kindness,The sea, the starry poles;Earth, sea, and sky, and God above—But, ah, not human souls!”

In summer, on the headlands,The Baltic Sea along,Sits Neckan with his harp of gold,And sings this plaintive song.

Picture credits:

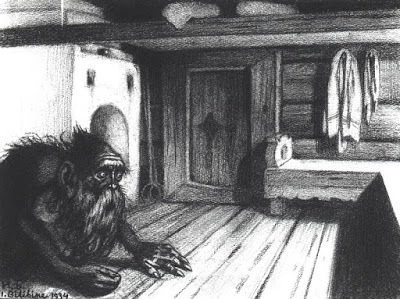

The Noekken or Nix by Theodor Kittelsen, Wikimedia Commons

Boy on White Horse, by Theodor Kittelsen, Wikimedia Commons

Agnete and the Sea King, John Bauer

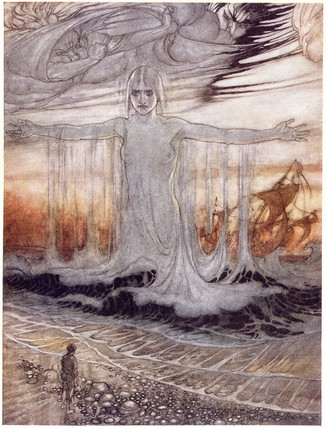

A Crowned Merman, by Arthur Rackham, private collection, Wikimedia Commons

Published on April 06, 2016 01:06

March 24, 2016

House Spirits

Talking with a group of Girl Guides a while ago, we fell (as you do) into a discussion about house spirits. The best known example, annoyingly enough, is Dobby the house-elf from J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series. I say ‘annoyingly’ because I have a soft spot for house spirits, and for me Dobby isn’t the best ambassador for the breed. Rowling’s approach to magical creatures from folklore is cavalier: she takes the names and happily reinvents the creatures. Her Boggart, for example, resembles not so much the boggarts of folklore, but a nursery bogeyman. ‘Boggarts’, declares Professor Lupin in ‘The Prisoner of Azkaban’, ‘like dark, enclosed spaces. Wardrobes, the gap beneath beds, the cupboards under sinks. …So, the first question we must ask ourselves is, what is a Boggart?’ Of course Hermione comes up with the answer:

‘It’s a shape-shifter,” she said. “It can take the shape of whatever it thinks will frighten us most.’

This certainly isn’t what a boggart from folk-lore does, although they are sometimes able to take the shape of animals such as black dogs. More about boggarts below. But to return to Dobby, the down-trodden house-elf of the Malfoy family. Dobby is a slave. He lives in terror, forced to punish himself whenever he criticizes his master. It’s a great twist of reinvention, but hardly representative of house spirits in general. From English brownies, boggarts, lobs and hobs, to the Welsh bwbach, from Scandinavian nisses and tomtes and German kobolds, to the Russian domovoi, most house spirits are independent, mischievous, strong-minded characters. And although Rowling employs the folklore motif best known from the Grimms’ fairy tale ‘The Elves and the Shoemaker’ that a gift of clothes will set the creature free (Dobby has to wear a pillowcase instead of clothes), many folk-tales make it clear that far from longing for this gift, many house spirits are perversely and deeply offended by it.

'It was indeed very easy to offend a brownie,' writes the folklorist Katherine Briggs in ‘A Dictionary of Fairies’ (1976):

It was indeed very easy to offend a brownie, and either drive him away or turn him from a brownie into a boggart, in which the mischievous side of the hobgoblin was shown. The Brownie of Cranshaws is a typical example of a brownie offended. An industrious brownie once lived in Cranshaws in Berwickshire, where he saved the corn and thrashed it until people began to take his services for granted and someone remarked that the corn this year was not well mowed or piled up. The brownie heard him, of course, and that night he was heard tramping in and out of the barn muttering:

“It’s no weel mowed! It’s no weel mowed!Then it’s ne’er be mowed by me again:I’ll scatter it ower the Raven staneAnd they’ll hae some wark e’er it’s mowed again.”

Sure enough, the whole harvest was thrown over Raven Crag, about two miles away, and the Brownie of Cranshaws never worked there again.

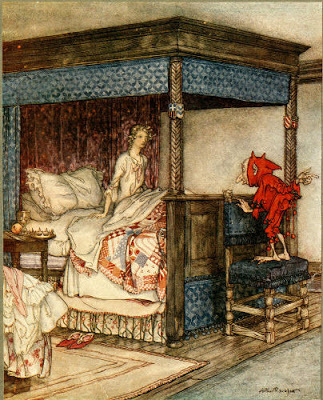

In folk-lore there’s never any suggestion that humans have a say in whether a brownie comes to work for them or not. Often they seem simply to belong in the house, to have been there for generations, such as the house spirit Belly Blin or Billy Blind in the illustration above, who comes to warn Burd Isabel that her betrothed, Young Bekie, is about to be forced to marry another woman.

‘Ohon, alas!’ says Young Bekie, ‘I know not what to dee; For I canno win to Burd Isbel, An’ she kensnae to come to me.’

XIV

O it fell once upon a day Burd Isbel fell asleep, And up it starts the Billy Blind, And stood at her bed-feet.

XV

‘O waken, waken, Burd Isbel, How can you sleep so soun’, Whan this is Bekie’s wedding day, An’ the marriage gaïn on?

Taking the hob's advice, Burd Isabel sets out with the Billy Blind as her helmsman, to cross the sea, find her lover and prevent the marriage. There's no great sense that she's surprised at this supernatural warning: rather, the Billy Blind (whose name like Puck's may have been generic, as it appears in other ballads too) seems to have been a known household inhabitant who could be expected to offer help when needed.

Some hobs may live locally in a pond, river or hollow, and come to the farm to work. They offer their services freely, and will stay for so long as they are treated with respect and a dish of cream or oatmeal is left out for them. Katherine Briggs writes of another such creature, a hobthrust:

There is a tale of a hobthrust who lived in a cave called Hobthrust Hall and used to leap from there to Carlow Hill, a distance of half a mile. He worked for an innkeeper called Weighall for a nightly wage of a large piece of bread and butter. One night his meal was not put out and he left for ever.

Briggs, by the way, wrote her own story about a hobgoblin. ‘Hobberdy Dick’ (1955), set in 17th century Oxfordshire, is one of the most delightful children’s books ever and glows with genuine folk-lore magic. Here, Hobberdy Dick scampers up to the Rollright Stones on May Eve, to greet his friends:

‘I’m main pleased to see ye, Grim,’ said Dick, greeting with some respect a venerable hobgoblin from Stow churchyard. ‘…These be cruel hard times. I never thought to see so few here on May Eve; but ‘tis black times for stirring abroad now.’ ‘Us never thought the like would happen again,’ said Grim. ‘Since the old days when the men in white came, and built the new church, and turned I out into the cold yard, I’ve never seen its like for strange doings. First I thought old days had come again, for they led the horses into the church in broad day; but the next day they led them out again. …And then they broke the masonry and smashed up the brave windows of frozen air… and these ten years there’s not been so much as a hobby-horse nor a dancer in the town.’ The Taynton Lob joined them – a small, good-natured creature with prick ears and hair like a mole’s fur on his bullet head. ‘It may be quiet in Stow,’ he said, ‘but there’s more going on than I like in Taynton churchyard.’ ‘What sort?’ said Hobberdy Dick. ‘Women,’ said the Lob half-evasively, ‘and things that feed on ‘em, and counter-ways pacing, and blacknesses.’

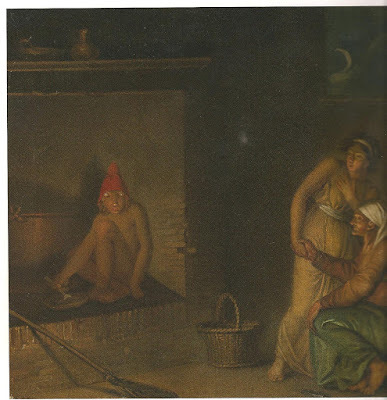

The Scandinavian Nisses are my personal favourites among house spirits. The painting above is by the 18th century Danish painter Nicolai Abraham Abildgaard, and I was once contacted by a New York auction house who asked me to confirm that the subject is indeed a Nisse. As you can see, he wears a red cap and is sitting by the fireside with his broom, eating groute, or buckwheat porridge - but the women of the household are startled and uneasy in his presence. Where the painting is now I do not know, but hope the lucky owner will not object to my sharing the image, considering I lent a hand in identifying the subject. I first met Nisses in Thomas Keightley’s 1828 compendium ‘The Fairy Mythology’, and made use of some of the legends in my own ‘Troll’ books (now available, if you will excuse the quick puff, in one volume under the title ‘West of the Moon’.) I was charmed by their mischief, vanity, naïvety, their occasional bursts of temper and their essential goodwill.

There lived a man at Thrysting, in Jutland, who had a Nis in his barn. This Nis used to attend to the cattle, and at night he would steal fodder for them from the neighbours. One time, the farm boy went along with the Nis to Fugleriis to steal corn. The Nis took as much as he thought he could well carry, but the boy was more covetous, and said, ‘Oh, take more; sure we can rest now and then?’ ‘Rest!’ said the Nis; ‘rest! and what is rest?’ ‘Do what I tell you,’ replied the boy; ‘take more, and we shall find rest when we get out of this.’ The Nis then took more, and they went away with it. But when they were come to the lands of Thrysting, the Nis grew tired, and then the boy said to him, ‘Here now is rest,’ and they both sat down on the side of a little hill. ‘If I had known,’ said the Nis as they were sitting there, ‘if I had known that rest was so good, I’d have carried off all that was in the barn.’

Here is my own Nis (in ‘Troll Fell’, book one of ‘West of the Moon’) disturbing the sleep of young hero Peer Ulffson as he lies in the hay of his uncles’ barn.

A strange sound crept into Peer’s sleep. He dreamed of a hoarse little voice, panting and muttering to itself, ‘Up we go! Here we are!’ There was a scrabbling like rats in the rafters, and a smell of porridge. Peer rolled over. ‘Up we go,’ muttered the hoarse little voice again, and then more loudly, ‘Move over, you great fat hen. Budge, I say!’ This was followed by a squawk. One of the hens fell off the rafter and minced indignantly away to find another perch. Peer screwed up his eyes and tried to focus. He could see nothing but black shapes and shadows. ‘Aaah!’ A long sigh from overhead set his hair on end. The smell of porridge was quite strong. There came a sound of lapping or slurping. This went on for a few minutes. Peer listened, fascinated. ‘No butter!’ the little voice said discontentedly. ‘No butter in me groute!’ It mumbled to itself in disappointment. ‘The cheapskates, the skinflints, the hard-heared misers! But wait. Maybe the butter’s at the bottom. Let’s find out.’ The slurping began again. Next came a sucking sound, as if the person – or whatever it was – had scraped the bowl with its fingers and was licking them off. There was a silence. ‘No butter,’ sulked the voice in deep displeasure. A wooden bowl dropped out of the rafters straight on to Peer’s head.

Our personal Nis, based on Abildgaard's, sits by our fire...

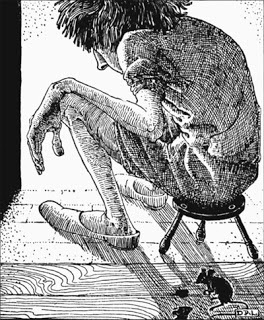

Our personal Nis, based on Abildgaard's, sits by our fire...In Russia, the house spirits are named domovoi, often given the honorific titles of ‘master’ or ‘grandfather’. According to Elizabeth Warner in ‘Russian Myths’ (British Library, 2002) the domovoi looked like a dwarfish old man, bright-eyed and coverred with hair, who dressed in peasant clothes and went barefoot. ‘Sometimes he took on the shape of a cat or dog, frog, rat or other animal. By and large, however, he remained invisible, his presence revealed only be the sounds of rustling or scampering.’ Like nisses and brownies, domovoi often busied themselves with household tasks, or with looking after animal in the stables. Sometimes they would befriend a particular cow or horse, which would flourish under their care. But they could also be mischievous, pinching the humans black and blue at night, or throwing dishes and pans about like a poltergeist. One last duty of the domovoi was to foretell ill events. ‘When a family member was awakened in the middle of the night by the touch of a furry hand that was cold and rough, some disaster was likely to occur.’

Temperamental, unpredictable, generous, hard-working, sometimes dangerous, the house spirit is reminiscent of the household gods of the Bible, the teraphim which Rachel stole from her father Laban (Genesis 31, 34), and of the Lares and Penates of the Romans. Better to have your own, humble little household spirit who could be pleased with a dish of cream or a bowl of porridge, folk may well have thought, than to try and gain the attention of the greater gods. And so the house spirit became a member of the family, helping and hindering in his own inimitable way.

Picture credits:

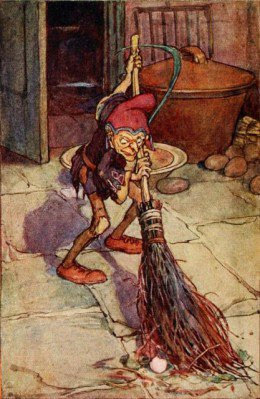

Brownie by Arthur Rackham

Billy Blind and Burd Isbel by Arthur Rackham Wikipedia

Lob Lie By the Fire by Dorothy P Lathrop: 'Down-a-down-derry,' Fairy Poems by Walter de la Mare 1922 Nisse by Nicolai Abrahan Abilgaard Domovoi by Ivan Bilibin - Wikimedia Commons Lararium: shrine of household gods from Pompei: photo by Claus Ableiter - https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

Published on March 24, 2016 01:46

March 14, 2016

Folklore snippets: The Slimy Lindworm

Pictured above is one of the 'head posts' from the famous Oseberg ship, which may well have been how the Vikings imagined the Lindorm or Lindworm, a slimy and poisonous and usually wingless Northern dragon. Ormr means snake, serpent, worm. Miðgarðsormr the Midgard Serpent, which lies beneath the sea and is so large it encircles the earth, biting its own tail, is the largest and most famous of the breed. Norse and even Northern English legends include many lesser Lindorms. Here are a few of them. First, a tale from Aarhus, in Denmark, which may well be the only story ever to feature a heroic glazier!

The Lindorm and the Glazier

It happened once many generations ago, that the bodies which were laid in Aarhus Cathedral disappeared time after time, without anyone knowing what the cause of this could be. It was then discovered that a lindorm had its hole under the church, and went in by night and ate the bodies. It was also found out that it was undermining the church, so that it would soon be liable to fall into ruins, and against this danger help was sought for in vain. At last there came a wandering glazier to Aarhus, who on learning the straits into which the town had come, gave his promise that he would help them. He made for himself a chest of mirror-glass, with only a single opening in it, and that only large enough for him to thrust out his sword through it. He had the chest placed on the floor of the church during the day time, and when midnight came, he kindled four wax candles, one of which he placed at each corner. The lindorm now came creeping through the choir-passage, and on seeing the chest and beholding its won image in the glass, it believed it to be its mate, but the glazier thrust his sword through its neck, and killed it at once. The poison and blood, however, which flowed from the wound, were so deadly, that the glazier perished in his chest.

From: Scandinavian Folk-Lore, ed. William Craigie, 1896

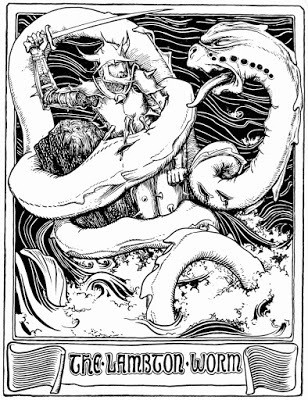

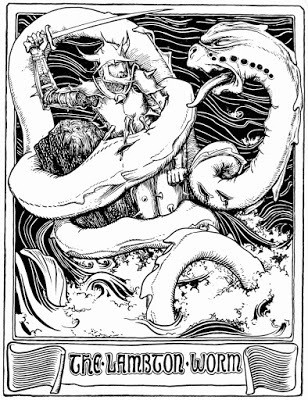

Folklore is full of stories about people who find and raise baby lindworms, which then proceed to grow until they menace the entire countryside. In County Durham there's the Lambton Worm which young John Lambton caught in the River Wear and - disgusted with its looks - carelessly tossed into a well before heading off to the Holy Land on crusade. In his absence the creature grew and grew, first poisoning the well, then crawling out and wrapping itself around an entire nearby hilltop, where it spent its days gobbling up livestock and unlucky passers-by. The Lord of Lambton Castle, John's father, attempted to keep the creature quiet by feeding it enormous quantities of milk daily, in a stone trough. When John finally returned from the crusades he tackled the worm, covering his armour with spikes on the advice of a Wise Woman. There was one proviso:

"If thou slay the Worm, swear that thou wilt put to death the first thing that meets thee as thou crossest again the threshold of Lambton Hall. Do this, and all will be well with thee and thine. Fulfil not thy vow, and none of the Lambtons, for generations three times three, shall die in his bed. Swear, and fail not."

The ruse worked: as the slimy worm cast its coils around young John and squeezed, the spikes pierced its sides and it fell writhing into the river and died. However, the first thing to meet the hero as he returned home was not his hunting dog, as he had planned, but his own aged father. As he was now clearly unable to fulfill the condition of the Wise Woman, the curse descended on the Lambtons as she had foretold.

I once read an entertaining book, 'The Great Orm of Loch Ness' by F.W. Holiday (1968), which claimed that the Loch Ness Monster not only exists, but is an enormous mollusc. The author pointed out that many accounts of sea-serpents and lake monsters describe them as possessing hairy manes: 'Virgil had never heard of the Loch Ness Orm, yet he wrote: "Look, from Tenedos there come down through the quiet sea two serpents in enormous coils, moving through the sea, and together they direct themselves to the strand, their chests held up between the waves and their blood-red manes are held up above the waves." ' Holliday suggests the revulsion which people who've 'seen' the LNM claim to have felt could be explained if the creature were in fact a giant mollusc. He continues, 'Some sea-slugs do in fact have a substance resembling hair or fur. It is known as cerata.' Hmmm! Be that as it may, I quite like the idea of 'Nessie' as perhaps our last surviving slimy Lindworm. Here's another Danish tale, about a maned serpent.

The King of the Vipers

A man in the district of Silkeborg once found a viper-king. It was a tremendously big serpent, with a mane like a horse. He killed it, and took it home with him, and boiled the fat out of it. This he put into a bowl and set aside in a cupboard, as he knew that the first person who tasted it would become so clear-sighted that they would be able to see much that was hid from other people; but just then he had to go out to the field, and thought that he could taste it another time. He had however a daughter who found this bowl with the fat in it, while her father was out in the field. She thought it was ordinary fat, which she was very fond of, so she spread some of it on a piece of bread, and ate it. When the man came home, he also spread a piece of bread with it, and ate it, but he could not discover that he could see any more than he did before. In the evening when the cows were being driven home, the girl came out and said, ‘Look, father, there’s a big red-speckled bull-calf in the black-faced cow.’ He could see well enough then that she had tasted the fat of the viper-king before him, and had thus got all the wisdom, in place of himself.

Scandinavian Folk-Lore, ed. William Craigie, 1896

Picture Credits:

Headpost from Oseberg Ship: Wikipedia

Lindworm from Swedish runestone: Wikipedia

The Lambton Worm: John Batten

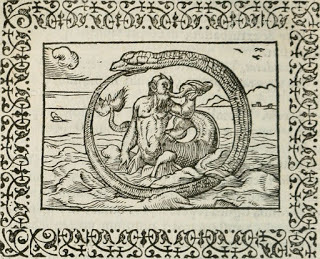

Sea Serpent: Andreas Alciati, c. 1583 - Wikimedia Commons

Published on March 14, 2016 04:47

Folkore snippets: The Slimy Lindworm

Pictured above is one of the 'head posts' from the famous Oseberg ship, which may well have been how the Vikings imagined the Lindorm or Lindworm, a slimy and poisonous and usually wingless Northern dragon. Ormr means snake, serpent, worm. Miðgarðsormr the Midgard Serpent, which lies beneath the sea and is so large it encircles the earth, biting its own tail, is the largest and most famous of the breed. Norse and even Northern English legends include many lesser Lindorms. Here are a few of them. First, a tale from Aarhus, in Denmark, which may well be the only story ever to feature a heroic glazier!

The Lindorm and the Glazier

It happened once many generations ago, that the bodies which were laid in Aarhus Cathedral disappeared time after time, without anyone knowing what the cause of this could be. It was then discovered that a lindorm had its hole under the church, and went in by night and ate the bodies. It was also found out that it was undermining the church, so that it would soon be liable to fall into ruins, and against this danger help was sought for in vain. At last there came a wandering glazier to Aarhus, who on learning the straits into which the town had come, gave his promise that he would help them. He made for himself a chest of mirror-glass, with only a single opening in it, and that only large enough for him to thrust out his sword through it. He had the chest placed on the floor of the church during the day time, and when midnight came, he kindled four wax candles, one of which he placed at each corner. The lindorm now came creeping through the choir-passage, and on seeing the chest and beholding its won image in the glass, it believed it to be its mate, but the glazier thrust his sword through its neck, and killed it at once. The poison and blood, however, which flowed from the wound, were so deadly, that the glazier perished in his chest.

From: Scandinavian Folk-Lore, ed. William Craigie, 1896

Folklore is full of stories about people who find and raise baby lindworms, which then proceed to grow until they menace the entire countryside. In County Durham there's the Lambton Worm which young John Lambton caught in the River Wear and - disgusted with its looks - carelessly tossed into a well before heading off to the Holy Land on crusade. In his absence the creature grew and grew, first poisoning the well, then crawling out and wrapping itself around an entire nearby hilltop, where it spent its days gobbling up livestock and unlucky passers-by. The Lord of Lambton Castle, John's father, attempted to keep the creature quiet by feeding it enormous quantities of milk daily, in a stone trough. When John finally returned from the crusades he tackled the worm, covering his armour with spikes on the advice of a Wise Woman. There was one proviso:

"If thou slay the Worm, swear that thou wilt put to death the first thing that meets thee as thou crossest again the threshold of Lambton Hall. Do this, and all will be well with thee and thine. Fulfil not thy vow, and none of the Lambtons, for generations three times three, shall die in his bed. Swear, and fail not."

The ruse worked: as the slimy worm cast its coils around young John and squeezed, the spikes pierced its sides and it fell writhing into the river and died. However, the first thing to meet the hero as he returned home was not his hunting dog, as he had planned, but his own aged father. As he was now clearly unable to fulfill the condition of the Wise Woman, the curse descended on the Lambtons as she had foretold.

I once read an entertaining book, 'The Great Orm of Loch Ness' by F.W. Holiday (1968), which claimed that the Loch Ness Monster not only exists, but is an enormous mollusc. The author pointed out that many accounts of sea-serpents and lake monsters describe them as possessing hairy manes: 'Virgil had never heard of the Loch Ness Orm, yet he wrote: "Look, from Tenedos there come down through the quiet sea two serpents in enormous coils, moving through the sea, and together they direct themselves to the strand, their chests held up between the waves and their blood-red manes are held up above the waves." ' Holliday suggests the revulsion which people who've 'seen' the LNM claim to have felt could be explained if the creature were in fact a giant mollusc. He continues, 'Some sea-slugs do in fact have a substance resembling hair or fur. It is known as cerata.' Hmmm! Be that as it may, I quite like the idea of 'Nessie' as perhaps our last surviving slimy Lindworm. Here's another Danish tale, about a maned serpent.

The King of the Vipers

A man in the district of Silkeborg once found a viper-king. It was a tremendously big serpent, with a mane like a horse. He killed it, and took it home with him, and boiled the fat out of it. This he put into a bowl and set aside in a cupboard, as he knew that the first person who tasted it would become so clear-sighted that they would be able to see much that was hid from other people; but just then he had to go out to the field, and thought that he could taste it another time. He had however a daughter who found this bowl with the fat in it, while her father was out in the field. She thought it was ordinary fat, which she was very fond of, so she spread some of it on a piece of bread, and ate it. When the man came home, he also spread a piece of bread with it, and ate it, but he could not discover that he could see any more than he did before. In the evening when the cows were being driven home, the girl came out and said, ‘Look, father, there’s a big red-speckled bull-calf in the black-faced cow.’ He could see well enough then that she had tasted the fat of the viper-king before him, and had thus got all the wisdom, in place of himself.

Scandinavian Folk-Lore, ed. William Craigie, 1896

Picture Credits:

Headpost from Oseberg Ship: Wikipedia

Lindworm from Swedish runestone: Wikipedia

The Lambton Worm: John Batten

Sea Serpent: Andreas Alciati, c. 1583 - Wikimedia Commons

Published on March 14, 2016 04:47

March 7, 2016

Pele the volcano goddess and her golden hair

I’d heard of Pele’s Hair but never seen any till, on a visit a few months ago to the Museum of Natural History in Kensington, I came across some in their Geological section. I was fascinated. But before I show you what it looks like, you need to know the story – or one of the many stories! Pele is a volcano goddess who inhabits the Halemaumau Crater of Kilauea, the most active of the five volcanoes from which Hawaii is formed. (The others are Mauna Kea, Mauna Loa, Hualalai and Kohala.) According to the folklorist William D. Westervelt's 1916 book ‘Hawaiian Legends of Volcanoes’, the Hawaiians told how Pele came from far away with her little sister Hiiaka, and drove out an older volcano god, Ai-laau, to establish her home on Hawaii.

Here is a story, told to Westervelt in 1905, of what happened when the young chiefs of Kahuku met the fiery and voluptuous goddess. It is a legend which explains the origin of a particular, ancient lava flow from which ‘two symmetrical mounds rise from the rugged splintered rocks. These are marked on the maps of the large island as “Na Puu o Pele” – the hills of Pele’.

Kahuku, the land now under past and present lava flows, was at one time luxuriant and beautiful. The sugar cane and taro beds were bordered with flowers and shaded by trees. Two of the young village chieftains excelled in the sports and athletic feats popular in those days. Wherever there was a grassy hillside and steep enough slope, holua races were carried on. Holua were very narrow sleds with long runners.

Maidens and young men vied with each other in mad rushes over the holua courses. Usually the body was thrown headlong on the sled as it was pushed over the brink of the hill at the beginning of the slide. The more courageous would kneel on the sled, while only the very skilful dared stand upright during the swift descent.

Holua sled reproduction

Holua sled reproduction Pele, the goddess of fire, loved this sport and often appeared as a beautiful and athletic princess. She came to Kahuku’s holua course, carrying her sled, and easily surpassed all the women in grace and daring. When the two handsome young chiefs saw her, they challenged her to race with them, and soon began competing for her love. As the days passed, however, they found her so capricious and hot-tempered that they began to suspect their companion must be Pele herself, come from her home Halemaumau ('The continuing house') of the volcano Kilauea on the other side of the island, able to wield the terrible power of underworld fires wherever she went. The young men spoke privately about their fears, and tried to draw away from their dangerous visitor. But Pele made it hard for them. She continually called them to race with her.

Then the grass began to die. The soil became warm and the heat intense. Small earthquakes rippled the ground, and the surf crashed in violence on the shore. The two chiefs became afraid. Pele saw it, and was overcome with anger. Her appearance changed. Her hair floated out in tangled masses, her arms and limbs shone as if wrapped with fire. Her eyes blazed like lightning and her breath poured forth in volumes of smoke. In terror, the chiefs rushed towards the sea.

Pele struck the ground with her feet. Again and again she stamped in anger, and earthquakes swept the lands of Kahaku. Then the fiery flood burst from the underworld and rushed down over Kahaku. Surfing the crest of the molten lava came Pele, her fury flashing in great explosions above the flood. The two young chiefs tried to flee northwards, but Pele hurled the fiercest torrents beyond them to turn them back. Then they fled southwards, but again Pele forced them back upon their own lands.

With the molten lava at their heels they raced for the beach, hoping to leap into their canoes and take to the sea. At top speed Pele came after them, shrieking like a hurricane, tearing out her hair and throwing it away in bunches. The floods of lava, obeying the commands of their goddess, spread out all over the lands of the two chiefs – who sped on, drawing nearer and nearer to the sea.

But Pele leaped from the flowing lava and threw her burning arms around the nearest of her former lovers. In a moment, his lifeless body was thrown to one side and the lava piled up around it, while at Pele’s command a new gush of lava rose from a fresh crater and swallowed all that was left.

As the other chief stood petrified by fear and horror, Pele seized him too, and called for another outburst of lava which rose rapidly around them. Thus the lovers of Pele died and thus their tombs were made: to this day they are called the Hills of Pele and are still to be seen as markers by the ocean side.

This is such a wonderful story, such an intense personification of the fiery and unpredictable volcano! As for the moment when Pele rushes after the two young chieftains, shrieking and tearing out her hair ‘in bunches’ – well, this is Pele’s Hair:

It looks exactly like hair – like the wad of hair you might tease from an over-used hair-brush.

These tangled golden filaments are made of volcanic glass. They are formed when drops of extremely hot, liquid lava – the sort commonly produced by ‘shield volcanoes’ like those of Hawaii – are hurled up in fountains and teased out by the wind into into hair-thin strands of basaltic glass – just as when you stretch hot toffee into brittle strands! – light enough to float away and catch like straw in treetops, fence-poles and telegraph wires. A marvel of nature, spun by Hawaiian storytellers into the hair of their terrifying, unpredictable goddess.

Picture credits

Halemaumau Crater: Hawaii Volcano Observatory, USGS - http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/kilauea/update..., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

Hawaiian Coastal landscape: Apua Point: By Lisa Eidson from Greenough, MT, USA - Hawaii Volcanoes Wilderness, Puna Coast Trail, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

Holua sled: Reproduction of a Hawaiian Holualoa sled, a sport involving sliding down lava rock courses into the ocean. On display in the Keauhou museum. W Nowicki

Pele's lava entering the sea: Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

Pele's Hair - Katherine Langrish; personal photos

Published on March 07, 2016 09:02

December 24, 2015

Troubadour Song

Due to personal matters I've had to neglect this blog for the last few months. Apologies. I hope to be back, perhaps with good news, in the New Year. In the meantime here's an unseasonal medieval song (though for some reason, medieval songs always feel Christmassy to me.) The author is anonymous, the approximate translation is mine; the music is by the Follorum Ensemble. A happy Christmas or winter holiday to you all!

Voulez vous que je vous chanteUn son d’amours avenant?Vilain nel fist mie,Ainz le fist un chevalierSous l’ombre d’un olivierEntre les bras s’amie.

Would you like me to sing youA fine song of love?By no peasant was it made:But a gentle knight who layWith his true love in his armsIn an olive tree’s shade.

Chemisete avoit de lin

Et blanc peliçon hermin

Et bliaut de soie

Chauces ot de jaglolaiEt solers de flours de maiEstroitement chauçade

Her chemise was of linenAnd her white pelisse of ermineOf silk was her dress.Her stockings were of iris leavesAnd her slippers of mayflowersHer feet to caress.

Ceinturete avoit de feuilleQue verdist quant li tens meuille,D’or est boutonadeL’aumosniere estoit d’amourLi pendant furent de floursPar amours fu donade.

Her belt was of leavesWhich grow green when it rains,Her buttons of gold so fine.Her purse was a gift of love,And it hung from flowery chainsAs it were a lovers’ shrine.

Et chevauchoit une muleD’argent ert la ferruereLa sele ert dorade;Sus la croupe par derriersAvoit plante trois rosiersPour faire li ombrage.

And she rode on a muleThe saddle was of gold,All silver were its shoes;Behind her on the crupperTo provide her with shadeThree rose bushes grew.

Si s’en va aval la preeChevaliers l’ont encontreeBeau l’on saluade:“Belle, dont estes vous nee?”“De France sui la louee,De plus haut parage.”

As she passed through the fieldsShe met gentle knightsWho begged courteously:“Fair one, where were you born?”“From France am I come,And of high family.

“Li rossignol est mon pereQui chant sor la rameeEl plus haut boscage.La seraine est mon mereQui chante en la mer saleLi plus haut rivage.”

“The nightingale is my fatherWho sings from the branches Of the forest’s highest tree.The mermaid is my motherWho sings her sweet chantOn the banks of the salt sea.”

“Belle, bon fussiez vous nee!Bien estes emparenteeEt de haut parage.Pleüst á Dieu nostre pereQue vous ne fussiez doneeA femme esposade.”

“Fair one, well were you born!Well fathered, well mothered,And of high family.If God would only grant That you might be givenIn marriage to me!”

Picture credits:

Lovers: The Maastricht Hours, http://britishlibrary.typepad.co.uk/d...

Lady riding: Gerard Horenbout, 16th century, Wikipedia

May: Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry - Wikipedia

Maastricht Hours, Southern Netherlands (Liège), 1st quarter of the 14th century - See more at: http://britishlibrary.typepad.co.uk/d...

Maastricht Hours, Southern Netherlands (Liège), 1st quarter of the 14th century, Stowe 17, f. 273 - See more at: http://britishlibrary.typepad.co.uk/d... Hours, Southern Netherlands (Liège), 1st quarter of the 14th century, Stowe 17, f. 273 - See more at: http://britishlibrary.typepad.co.uk/d... Hours, Southern Netherlands (Liège), 1st quarter of the 14th century, Stowe 17, f. 273 - See more at: http://britishlibrary.typepad.co.uk/d...

Mermaid: Besançon - BM - ms. 0069, detail of p. 458. Breviary, use of Besançon. Rouen, before 1498.

Published on December 24, 2015 05:01

June 25, 2015

Water Spirits

Water. You can touch it, but you can’t hold it. It runs between your fingers. It flows away in streams, in rivers, talking to itself. ‘Still glides the stream, and shall forever glide.’ In both its transience and its endurance it’s a metaphor for time. Rivers change every moment, but they are old – in some cases literally older than the hills. They were flowing before we were born; they will still be flowing long after we are gone.

Water reflects things – trees, the sky – but upside down, distorted and fluid. Peer over the brink and your own face peeks up at you: like yet unlike, pale and transparent. That image could be another you, living in another world. Maybe in the Other World; after all, you can’t breathe water. So who is that?

Modern mirrors show perfect reflections. Each one of us knows what we look like (or believe we do: mirrors still pull that sly trick of showing us ourselves in reverse.) But for most of history and prehistory mirrors were rare or non-existent. People saw one another’s faces but not their own. Only the reflecting surface of still water could offer the chance, but how could you be sure that the face looking up was truly yours? Maybe it was an ancestor’s face, or a spirit’s. Maybe it had a message to give you. (But better not bend too close.)

Modern mirrors show perfect reflections. Each one of us knows what we look like (or believe we do: mirrors still pull that sly trick of showing us ourselves in reverse.) But for most of history and prehistory mirrors were rare or non-existent. People saw one another’s faces but not their own. Only the reflecting surface of still water could offer the chance, but how could you be sure that the face looking up was truly yours? Maybe it was an ancestor’s face, or a spirit’s. Maybe it had a message to give you. (But better not bend too close.)A clear puddle after rain is a window into the ground. You can look down vertically into a deep underworld. A far, bright sky flashes below the upside-down trees. Could it be the world of the dead, who are buried in the ground? In the spring or early summer of the year 2049 BCE (it makes me shiver to write that, but we know the precise date from tree-ring dating), at least fifty people with bronze axes gathered on a salt marsh to construct a wooden circle with an upside-down oak stump planted at its centre, roots in the air, crown in the ground. This was the circle now called Seahenge, and surely the inverted tree was intended to grow in the Other World - a real and solid version of the ghostly reflections of trees which can be seen in any pool.

Reflections in water show us three worlds, the sky above us, the surface which is touchable and level with the world we walk upon, and the strange depths beneath. If you plunge a straight stick or rod into water, it appears broken, but you can draw it out again unharmed. We know it's because of the refraction of light; but the effect must have seemed mystical and magical to people down the ages. Is that what prompted the custom of ritual damage to swords and spears - bending, snapping and breaking them - before they were offered to the underwater world? As if the water itself was showing what needed to be done? In her book The Gods of the Celts Dr Miranda Green tells of two Iron Age sacred lakes into which important people threw important offerings: Llyn Fawr in South Glamorgan and Llyn Cerrig Bach on Anglesey.

Llyn Fawr is the earlier, the date of deposition of the objects lying around 600BC. Here a hoard was found in a peat-deposit that had once been a natural lake; find include two sheet-bronze cauldrons… socketed axes and sickles. The material [at Llyn Cerrig] ranges in date from the second century BC to the first century AD. The finds come from the edge of a bog at the foot of an eleven foot high sheer rock cliff which provided a good vantage point for throwing offerings. In the Iron Age the lake would have extended to [the foot of the cliff] and the uncorroded condition of the metalwork shows that it sank immediately into the water. The offerings are of a military/aristocratic nature: weapons, slave chains, chariots and harness fittings.

King Arthur’s sword Excalibur comes from under the water.

They rode till they came to a lake, that was a fair water and broad, and in the midst of the lake Arthur was ware of an arm clothed in white samite, that held a fair sword in that hand.

Merlin and Arthur are advised by a ‘damosel’ (the Lady of the Lake) to row a boat towards the arm:

And when they came to the sword that the hand held, Sir Arthur took it up by the handles… and the arm and the hand went under the water.

At the very end of the Morte D’Arthur, at Arthur’s command Sir Bedivere manages (on the third attempt) to hurl Excalibur into the lake again:

And he threw the sword as far into the water as he might; and there came an arm and a hand above the water and met it, and caught it, and shook it thrice and brandished, and then vanished away the hand with the sword in the water. So Sir Bedivere came again to the king and told him what he saw.“Alas”, said the king, “help me hence, for I dread me I have tarried over-long.”

Only now may Arthur depart for the Isle of Avalon in a barge full of queens and ladies clad in black. So the sword which conferred upon Arthur a kind of supernaturally-awarded status must be relinquished, returned to its mysterious Otherworldly keeper, before he can commence his journey to the land of death and rebirth in the watery Somerset fens. I wonder if some of those Celtic offerings were also funeral rites?

Water is necessary to life. It has many practical uses. You can drink water, wash in it, cook with it, irrigate your fields. It turns your mill wheel to grind your corn, but it can also drown you or your children, or rise up in floods and sweep your house away. Homely, treacherous, necessary, strange, elemental: no wonder that we populated it with spirits. Goddesses like Sabrina of the Severn, or Sulis of the hot springs in Bath – loreleis, ondines, naiads, nixies – sly, beautiful, impulsive but cold-hearted nymphs whose white arms pull you down to drown.

Then again, rivers can be gods, such as Father Tiber or TS Eliot’s ‘strong brown god’, the Thames. Or Stevie Smith’s ‘River God’:

I may be smelly and I may be old,Rough in my pebbles, reedy in my pools,But where my fish float by I bless their swimmingAnd I like the people to bathe in me, especially women.But I can drown the foolsWho bathe too close to the weir, contrary to rules.And they take a long time drowningAs I throw them up now and then in the spirit of clowning.Hi yi, yippety-yap, merrily I flow,Oh I may be an old foul river but I have plenty of go…

Male, female or animal, water spirits are dangerous and tricksy. Scottish kelpies or waterhorses used to linger by the banks of lochs in the gloaming, tempting people to climb upon their backs - upon which they would gallop into the water. The 19thcentury folklorist William Craigie tells how, in Scandinavia:

The river-horse (bäck-hästen) is very malicious, for not content with leading folk astray and then laughing at them, when he has landed them in thickets and bogs, he, being Necken himself, alters his shape now to one thing and now to another, although he commonly appears as a light-grey horse.

It is certain that the river-horse still exists, for it is no more than a few years back that a man in Fiborna district, who owned a light-grey horse, was coming home late one night and saw, as he thought, the horse standing beside Väla brook. He thought it strange that his man had not taken in Grey-coat, and proceeded to do so himself, but just as he was about to lay hold of it it went off like an arrow and laughed loudly. The man turned his coat so as not to go astray, for he knew now who the horse was.

In Kristianstad there was a well, from which all the girls took drinking water, and where a number of the boys always gathered as well. One evening the river-horse was standing there, and the boys, thinking it was just an old horse, seated themselves on its back, one after the other, till there was a whole row of them, but the smallest one hung on by the horse’s tail. When he saw how long it was he cried, “Oh, in Jesus’ name!” whereupon the horse threw all the others into the water.

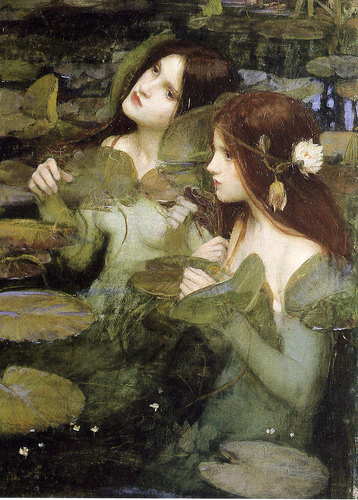

Even today people throw coins into fountains and wishing wells – ‘for luck’. In my novel Dark Angels , the 12th century castle La Motte Rouge has a well haunted by a mournful White Lady. I revisited her, and her friend the hearth-hob, in a story called By Fynnon Ddu which I wrote for the Sussex Folklore Centre’s journal Gramarye (Summer 2014, Issue 5). I wanted to contrast the transience of humanity with the deep time in which such creatures live. In this story, the castle is just being built, yet both the hob and the water spirit are already ancient. Here’s an extract.

The hob hugged his tattered rabbitskin around him and peered into the well. It was a long, narrow pool, lined with leaning mossy stones. At one end a spring bubbled up under a rough rocky arch and trickled out at the other into a little deep-cut brook, and the dark water was full of weeds, cress and frogspawn. A small frog plopped into the pool and pushed through the skin of the water in a series of fluid kicks. The hob stiffened all over like a hunting cat. He shot out a hairy arm.There was a swirl and a heave in the depths. The spring gushed up in a burst of fierce bubbles. The frog vanished in a fog of sediment. “What did you do that for?” yelped the hob. A face looked up through the brown water-glass, framed in drifting clouds of hair which spread away in filmy tendrils. The eyes were great dark blurs, the pale-lipped smile both shy and wild. “You doesn’t even eat,” the hob groused on. “You doesn’t know what ‘tis to have an empty belly.”The water spirit slipped upwards. Her head emerged from the water, glistening. In air and daylight she was difficult to see: a slanting glimmer, like a risen reflection. She propped narrow elbows on the brink and offered him a handful of cress. “Lenten fare. That an’t going to put hairs on me chest,” said the hob sulkily, but he stuffed it into his mouth and chewed. A bout of hammering battered the air. The water spirit flinched, and the hob nodded at her. “Yus. Men. They’m back again at last.”She pushed her dripping hair back behind one ear and spoke in a voice soft as a dove cooing in a sleepy noon. “Who?”The hob snorted, spraying out bits of green. “Who cares who? S’long as they has fires, and a roof overhead, and stew in the pot –”“Is it the Cornovii?”“You allus asks me that.” The hob glanced at her with wry affection and shook his head. “They’m long gone,” he said gently. “They don’t come back. Times change and so do men.”“Was it such a long time?” She was teasing a water-beetle with a tassel of her hair. “I liked the Cornovii. They used to bring me toys.”“Toys?”“Things to play with.” She looked up at him through half-shut eyes. “Knives and spearheads, brooches and jewels. Girls and boys. I’ve kept them all.”“Down at the bottom there? How deep do it go?” Hackles bristling, but fascinated, the hob craned his neck and tried to peer past his own scrawny reflection.“Come and see.” She reached out her hands with an innocent smile, but he drew hastily back. “No thanks!”

In Frederick de la Motte Fouqué’s ‘Undine’ (1807), a knight marries Undine, a river spirit, and swears eternal faithfulness to her. However his previous mistress, Bertalda, sows suspicion of Undine in his mind and he comes to regard her unbreakable bond with the waterspirits – especially her terrifying uncle Kuhlborn, the mountain torrent – with fear and disgust. He repudiates his union with Undine and prepares to marry Bertalda instead. In a spine-tingling climax, the castle well bubbles uncontrollably up to release the veiled figure of the Undine, who walks slowly through the castle to the knight’s chamber. In my 1888 translation:

The knight had dismissed his attendants and stood in mournful thought, half-undressed before a great mirror, a torch burnt dimly beside him. Just then a light, light finger knocked at the door; Undine had often so knocked in loving sportiveness. “It is but fancy,” he said to himself; “I must to the wedding chamber.” “Yes, thou must, but to a cold one!” he heard a weeping voice say. And then he saw in the mirror how the door opened slowly, slowly, and the white wanderer entered, and gently closed the door behind her. “They have opened the well,” she said softly, “And now I am here and thou must die.”

Ignore the force of water at your peril.

Picture credits

Nokke (Water spirit) by Theodor Kittelsen

Reflection - Katherine Langrish, personal photo

Seahenge: Norfolk Museum

Sir Bedivere by Aubrey Beardsley University of Rochester

Hylas and the Nymphs by Frederick Waterhouse (detail)

Nokke as White Horse by Theodor Kittelsen

Cover of Gramarye with Arthur Rackham illustration of the Frog Prince

Undine by Arthur Rackham

The Shipwrecked Man of the Sea by Arthur Rackham

Published on June 25, 2015 04:54

June 16, 2015

The Naming of Dark Lords (a Difficult Matter)

It isn't just one of your fantasy games...

Aged nine or so, one of my daughters co-wrote a fantasy story with her best friend. By the time they’d finished it ran to sixty or seventy pages, a wonderful joint effort – they’d sit together brainstorming and passing the manuscript to and fro, writing alternate chapters and sometimes even paragraphs. There were two heroines (one for each author) and sharing their adventures was a magical teddybear named Mr Brown who spoke throughout in rhyming couplets. Transported to a magical world on the back of a dove called Time – who provided the neat title for the story: ‘Time Flies’ – the trio find themselves battling a Dark Lord of impeccable evil with the fabulous handle of LORD SHNUBALUT (pronounced: ‘Shnoo-ba-lutt’.) The two young authors had grasped something crucial about Dark Lords. They need to have mysterious, sonorous, even unpronounceable names.

Imagine you’re writing a High Fantasy. You’ve got your world and you’ve sorted out the culture: medieval in the countryside with its feudal system of small manors and castles; a renaissance feel to the bustling towns with their traders, guilds and scholar-wizards. The forests are the abode of elves. Heroic barbarians follow their horse-herds on the more distant plains. Goblins and dwarfs battle it out in the mountains.

And lo! your Dark Lord ariseth. And he requireth a name.

Let’s take an affectionate look at the names of a few Dark Lords. The first to come to mind is of course Tolkien’s iconic SAURON from The Lord of the Rings. A name not too difficult to pronounce, you’d think – except that when the films came out I discovered I’d been getting it wrong for years. I’d always assumed the ‘saur’ element should be pronounced as in ‘dinosaur’, and ‘Saw-ron’, with its hint of scaly, cold-blooded menace, still sounds better to me than ‘Sow-ron.’ I was only 13 when I first read The Lord of the Rings, and although I was blown away, and keen enough to wade through some of the Appendices, I never got as far as Appendix E in which Tolkien explains that ‘au’ and ‘aw’ are to be pronounced ‘as in loud, how and not as in laud, haw.’ But who reads the Appendices until they’ve read the entire book? - by which time I’d been getting it wrong for months and my incorrect pronunciation was fixed. Still, there it is. Peter Jackson got it right and I was wrong.

Not content with one Dark Lord, Tolkien created two - three, if you count the otherwise anonymous Witch-King of Angmar, leader of the Nazgul and the scariest of the bunch if you want my opinion. In The SilmarillionMelkor is given the name MORGOTH after destroying the Two Trees and stealing the Silmarils. In Sindarin the name means ‘Dark Enemy’ or ‘Black Foe’, but Tolkien must have been aware that its second element conjures the 5thcentury Goths who sacked Rome and that, additionally, the name carries echoes of MORDRED, King Arthur’s illegitimate son by his half-sister Morgan le Fay. Of course Mordred is not a high fantasy Dark Lord, but he’s certainly a force for chaos and darkness. Though the name is actually derived from the Welsh Medraut(and ultimately the Latin Moderatus), to a modern English ear it suggests the French for death, ‘le mort’, along with the English ‘dread’: a pleasing combination for a villain. Mordred and Morgoth are names redolent of fear, death and darkness, and the ‘Mor’ element appears again in Sauron’s realm of ‘Mordor’, the Black Land.

The name of JK Rowling’s LORD VOLDEMORT is also suggestive of death and borrows some of the dark glamour of Mordred, but the circumlocutory phrase HE-WHO-MUST-NOT-BE-NAMED (used by his enemies for fear of conjuring him up) certainly owes something to H. Rider Haggard’s Ayesha, SHE WHO MUST BE OBEYED. Interestingly, males become Dark Lords but females are never Dark Ladies – which doesn’t have the same ring at all*. They turn into Dread Queens, such as Galadriel might have become if she had succumbed to temptation and taken the Ring from Frodo:

In place of the Dark Lord you will set up a Queen. And I shall not be dark, but beautiful and terrible as the Morning and the Night! Fair as the Sea and the Sun and the Snow upon the Mountain! Dreadful as the Storm and Lighting! Stronger than the foundations of the earth. All shall love me and despair!

Coming down to us from many an ancient goddess, Dread Queens are usually beautiful, sexual women of great power and cruelty, like T.H. White’s MORGAUSE, Queen of Orkney from The Once And Future King, busy – on the first occasion we meet her – boiling a cat alive. In his notes about her, T.H. White wrote:

She should have all the frightful power and mystery of women. Yet she should be quite shallow, cruel, selfish…One important thing is her Celtic blood. Let her be the worst West-of-Ireland type: the one with cunning bred in the bone. Let her be mealy-mouthed: butter would not melt in it. Yet also she must be full of blood and power.

Blood, power (and racism): White is clearly very frightened of this woman. He didn’t find her character in Le Morte D’Arthur: Malory’s Morgawse is a great lady whose sins are adulterous rather than sorcerous – but her half-sister MORGAN LE FAY is an enchantress whose name is derived from the Old Welsh/Old Breton Morgen, connected with water spirits and meaning ‘Sea-born’. A final example from Celtic legend is Alan Garner’s ‘MORRIGAN’, a name variously translated as Great Queen or Phantom Queen, depending this time on whether the ‘Mor’ element is written with a diacritical or not. Enough already!

Not every Dark Lord’s name works as well as Sauron and Voldemort. I’m underwhelmed by Stephen Donaldson’s ‘LORD FOUL THE DESPISER’ from The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, Unbeliever. Donaldson seems jumpily aware of the long shadow of Tolkien. He struggles to produce convincing names (for example the Cavewight ‘Drool Rockworm’ whose name to my mind belongs not in the Land, but in the Discworld). I've always thought that to call a Dark Lord ‘Lord Foul’ is barely trying, and tagging ‘the Despiser’ on to it doesn’t help. (‘He’s foul, I'm telling you! He’s really foul! I’ll prove it – he despises things too!’) Tacking an adjective or adverb on to a fantasy name often only weakens it, as in the case of the orc-lord AZOG THE DEFILER whom Peter Jackson introduced to the film version of The Hobbit. Azog is to be found in Appendix A of The Lord of the Rings, where Tolkien writes in laconic prose modelled on the Icelandic sagas, of how Azog killed Thrór, hewed off his head and cut his name on the forehead (thus indeed defiling the corpse).

Then Nár turned the head and saw branded on it in Dwarf-runes so that he could read it the name AZOG. That name was branded in his heart and in the hearts of all the Dwarves afterwards.

Just ‘Azog’, you see? The name on its own is quite enough.

Donaldson is trying to emulate Tolkien’s linguistic density, in which proper names from different languages pile up into accumulated richness like leafmould: Azanulbizar, the Dimrill Dale, Nanduhirion. But we cannot all be philologists. Lord Foul’s various sobriquets, which include ‘The Gray Slayer’, ‘Fangthane the Render’, ‘Corruption’, and ‘a-Jeroth of the Seven Hells’, only suggest to me an author having a number of stabs at something he knows in his heart he isn’t quite getting right. ‘Fangthane’? A word which means ‘sharp tooth’ attached to a word which means ‘a man who holds land from his overlord and owes him allegiance’? It could work for a Gríma Wormtongue, but not for a Dark Lord.

Dark Lords are a strange clan. Why anyone over the age of eighteen would wish to dress entirely in black and live at the top of a draughty tower in the midst of a poisoned wasteland is something of a mystery, unless perhaps Dark Lords are younger than we think. If they’re actually no older than Vyvyan from The Young Ones, it could totally explain their continuously bad temper, their desire to impress, their attacks on mild mannered, law-abiding citizens (aka parents), their taste in architecture (painting the bedroom black and decorating it with heavy metal posters) and their penchant for logos incorporating spiderwebs, fiery eyes, skulls, etc.

It probably also explains their peculiar names. Most teenage boys at some point reject the names their parents picked for them and go in for inexplicable nicknames like Fish, Grazz, or Bazzer… Anyway, the all-out winner of the Dark Lord Weird Name competition has got to be Patricia McKillip, whose beautiful fantasies are written in prose as delicate and strong as steel snowflakes (Ombria In Shadow is one of my all-time favourites). But the Dark Lord in her early trilogy The Riddle-Master rejoices in (or is cursed with) the altogether unpronounceable and eye-boggling GHISTELWCHLOHM. He wins hands down. Lord Schnubalut, eat your heart out.

*The pun was unintentional.

Picture credits:

Cover detail from The Fellowship of the Ring, George Allen and Unwin (author's possession)

Melkor, Wikimedia commons, http://www.aveleyman.com/ActorCredit.aspx?ActorID=5137

Morgan le Fay by Frederick Sandys (1864)

Adrian Edmonson as Vyvyan Basterd from The Young Ones http://www.aveleyman.com/ActorCredit.aspx?ActorID=5137

Published on June 16, 2015 07:54

May 7, 2015

Last Train From Kummersdorf - and the Bremen Town Musicians

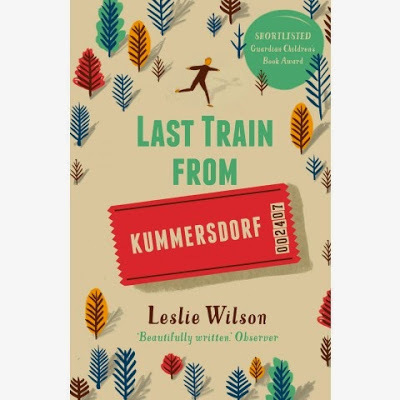

Some time ago I was talking about fairytales with my friend Leslie Wilson, whose two books for teenagers are realistic fiction set in Nazi Germany, and was struck when she remarked, ‘There are fairytale motifs in my books, too, you know.’ Realising it was true, I immediately asked if she would write a post about the fairytale elements in her YA novel, Last Train from Kummersdorf – which has been released in a new edition today.

‘Last Train From Kummersdorf’ was shortlisted for the Guardian Fiction Prize, and much of the emotional truth of the narrative stems from the traumatic wartime experiences of Leslie's own mother.On the run from the advancing Russian army in 1945, two young people, Effi and Hanno, join forces on the road, teaming up to defend and help each other from the dangers they meet along the way. In this extract, Russian planes have strafed a column of refugees, killing the horses who’ve been pulling the wagons.

…Ida looked at the horses. They were both dead now, but for the life of her she couldn’t face chopping them up for meat. She scolded herself for weakness. Anyway, Magda was going to do it. But when Magda got to the horses she hesitated, wondering how to start. Then Herr Hungerland walked over to stand beside her, putting out his hand for the knife. ‘Let me,’ he said, ‘I have some knowledge of physiology. I am a doctor.’

That a doctor - whose skills are for healing - should find his main utility in this situation the ability to butcher a dead horse, makes a terrible and ironic point about the nature of war.

Here’s Leslie herself, talking about the fairytale analogue to ‘Last Train From Kummerdorf’:

THE BREMEN TOWN MUSICIANS

When my novel Last Train from Kummersdorf was published, my brother read it and then said to me: ‘It’s not at all a realistic novel, is it?’ And indeed, it isn’t, though I’m not sure how many people have noticed.

It is a novel very much in the German tradition: and at first glance it is close to other German novels and short stories about the Second World War and ‘Die Flucht’ – which means ‘The Flight’, meaning the escape from the advancing Russian army. Most of these are realist. But as I wrote it I knew I was in the German romantic/gothic tradition, like Storm’s Schimmelreiter (The Rider on the White Horse), or Gotthelf’s The Black Spider. Less unequivocally so, perhaps, than Grass’s Tin Drum. (A novel which made it hard, at first, to write Kummersdorf, because Grass seemed to have said it all so brilliantly.) But then I began to see that I had things to say that hadn’t already been said, and dared to go forward.

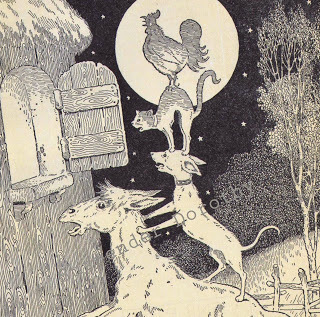

That tradition is deeply rooted in folklore, and so am I. I spent years of my childhood reading folktales from all over the world. But it was when I was doing my degree in German that I read the whole way through the three-volume 1900 jubilee edition of Grimm that I was lucky enough to be given in childhood – and found my mind going clicketty-clack, categorising the stories, seeing that certain basic plots came up over and over again, with variations – and once a motif from the Nibelungenlied, the medieval Lay of the Nibelungs, in The Two Brothers: the sword put between a man masquerading as his twin brother and his sister-in-law when they have to sleep together. Siegfried puts a sword between himself and Brünhilde when he beds her in the guise of his brother-in-law-to be, Gunther. Maybe the Nibelungenlied draws from popular folklore, maybe the folk story has picked up part of the epic. In any case, it was deeply important to me to read the collection then, one of those things that one knows one has to do, even if one doesn’t know why. What it taught me is what others have said before me: there are only a limited amount of plots. The other realisation was also important: that stories are interdependent and feed each other. When – many years later - I started to write Kummersdorf, I quickly realised the influence, in my story, of The Bremen Town Musicians.

The Brothers Grimm were undoubtedly motivated by a desire to establish an authentic ‘German’ voice; a project rooted in the dubious one of German unification by force, rather than through the liberal impulse of revolution. That hope was dashed in 1948. As for the ‘authentic German voice’, that was a stupid idea. Folktales are international; carried along trade routes, they flit from country to country. Some of the Grimm stories came from Perrault. Maybe nursemaids picked them up in the houses of the francophile German aristocracy and middle class, and took them back into their own humble homes to tell to their own children. At that point other motifs infiltrated them, which is why Aschenputtel is different from Cendrillon. The other thing that the Grimm brothers did was to edit the stories – but I am quite certain that they still retain much of the authentic vernacular voice.

I think the value of myth and fairy stories is that they mitigate the dreadful things that happen to human beings. Stories of heroes, of magical rescues, of the world turned upside down, give us courage to face a harsh world. The savagery of the revenge sometimes taken expresses people’s deep inner anger; an anger too often bitten back in a world where injustice and callous exploitation were – and still are - rife. The Bremen Town Musicians is about old animals, worked-out, threatened with various brutal ends because they’re no use to their masters any longer. They find a robbers’ house in the forest and frighten the robbers away from it and their booty simply by making their various noises – music, according to them – so then they are able to live at their ease for the rest of their lives. I think the story reflects the reality of the lives of story-telling grandparents, who were similarly regarded as useless – except to keep the children quiet. It’s a story about Grey Power. Or just about the powerless who manage – just for once – to turn the tables. And, significantly, when the robber comes back to see if the band can repossess their house, the voice that finally terrorises him is that of the cockerel who he interprets as a judge’s voice, calling out: ‘Bring the rogue to me!’

Last Train from Kummersdorf is about civilians, and civilians who end up facing the incoming army. As a child, I always noticed the value that’s placed in wartime on soldiers’ lives over those of civilians. I resented it, because from an early age I’d heard from my mother just what defeat means. When the soldiers are dead, it’s the old people, the youngsters and children who are in the front line. Many of the Russian soldiers entering Germany in 1945 behaved the way conquering soldiers have always done. They behaved that way even in the Slav countries they came to first, so it wasn’t, as many people have said, just a revenge-taking for the dreadful things the German soldiers had done in Russia. Members of the Red Army raped, tortured, murdered and looted, with Stalin’s blessing. The innocent suffered along with the guilty. ‘Deutsche Frau ist deutsche Frau,’ a Russian soldier said when it was pointed out to him that the woman he was about to rape was Jewish. ‘German woman is German woman.’ My mother got away from a Russian by the skin of her teeth, ran away into the forest and the mountains and almost died there. That, along with the expulsion of many of her family from their homes in Silesia, is the ‘core narrative’ I was working with.

If you sleep rough, it very quickly starts to do things to your perception of reality: dossers and refugees live a different kind of reality from ours, in our houses, where we can shut the door on danger. I think when you’re in constant danger of your life, then some fundamental, mythic perceptions probably kick in. My mother, wandering the mountains in April, was living out a fundamental folkloric story of pursuit, only it was Russian soldiers, rather than enraged witches, she was escaping from. Hanno and Effi, in Kummersdorf, are trying to escape from the Russians too, but they have a Quest, too: to get to the West, where the boy Hanno’s mother is, and where the girl Effi is firmly convinced she’ll find her father. The teenagers pick up other people, rag-tag refugees; it was at that point that I said to myself: ‘This story is like The Bremen Town Musicians!’

But my refugees don’t find the baddies in a house: the baddies are on the run, too, and the kids pick some of them up and have to schlepp them along willy-nilly; the old crazy doctor who’s murdered disabled children in the ‘euthanasia’ programme; the rabid Nazi police officer who nurses a strange hatred for the boy Hanno. But there’s someone else: the little man Sperling (which means sparrow) with his dog Cornelius and his magic cart which he makes over to the kids after a Russian air attack kills him. When the kids play a game with the railway tickets in the cart, when Effi teases the adults with the fantasy they’ve cooked up – when suddenly the other refugees start believing the alluring fantasy of a train that can carry them out of danger – this is story taking people over, altering their perceptions of reality. And the train itself, when it half-magically appears, becomes a location where the truth comes out about the refugees’ pasts. Though it’s no means of escape for them, so the story doesn’t end there.

My novel, like so many fairy-tales, and especially the Musicians, takes place in the German ‘Wald’, the forest, the location where so many German folk tales play off. I knew the German forest from an early age, though not the Brandenburg forest of the novel. My grandfather had a house on the eastern shore of the Rhine. My brother and I used to go off into the Wald and explore it, but it felt dangerous; full of wild boar for one thing, who might attack us in the breeding season. Once, when I was a baby, my mother was on her own in the house at night – my grandparents had gone out together – and she heard a snuffling and thumping against the door, a huge animal apparently trying to break in. She was terrified. In the morning, there was blood on the grass outside, and the adults realised it must have been a wounded boar. It wasn’t really a danger to us, of course, but the story of that inchoate menace in the night coming out of the Wald stayed with me. When the stags were rutting, the clash of their antlers echoed and filled the valley in front of the house; they were almost as loud as thunderclaps.

The road from Opa’s house led to a little clearing in the woods where a flame flickered, day and night. I was told that a child had been lost out there once, and its desperate mother promised the Virgin Mary that if her child was found, she’d set a flame there to burn to help other travellers who might be lost. The flame marked the place where the child was safely found. I don’t know if it’s still there. I can picture it now, at a place where two paths met, in a part of the forest planted with conifers; the dusty path scattered with needle-mess and resinous cones, and the dimness among the trees. Mirkwood. The forest went on and on, it seemed enormous. I knew the witches and wolves and robbers were in there; you only had to go far enough. And so it became part of my psyche and so I had to write about it.

Last Train from Kummersdorf, by Leslie Wilson, Faber & Faber, May 7th 2015

Published on May 07, 2015 04:43

March 27, 2015

Alan Garner at Jodrell Bank

The Lovell Telescope, Jodrell Bank

The Lovell Telescope, Jodrell BankThe lecture ‘Powsells and Thrums’, delivered by Alan Garner at Jodrell Bank on Wednesday night, was the first of a series designed to consider the nature of creativity and its importance to what Garner maintains is an arts/science spectrum – not two cultures, as CP Snow suggested, but a continuity. Powsells and thrums, he explained, are old words for the oddments of thread and scraps of cloth left over from weaving and kept for personal use: metaphors for the scraps of story and oddments of meaning which can be woven and pieced together to create something new. Which is exactly what he did in his lecture.

I’m not going to try and deliver a comprehensive report of the evening. Alan Garner spoke with wit, humour and quiet eloquence for a full hour, and I hope and trust the lecture will eventually appear in print. With many omissions, these are merely some of my impressions and memories of it – powsells and thrums, snippets and fragments which you can turn about and reshape for yourselves.

He began with a story from the introduction to Dylan Thomas’s Collected Poems. Thomas tells the story of a shepherd who, asked why he made, from within fairy rings, ritual observances to the moon to protect his flocks, replied: ‘I’d be a damned fool if I didn’t!’ Thomas adds, ‘These poems are written for the love of man and in praise of God, and I’d be a damned fool if they weren’t.’

Mow Cop

Mow CopHow does a story come into being? In 1956, ‘rummaging in a dustbin’, Garner saved a fragment of newspaper containing the story of two lovers who quarrelled. The boy threw a tape at the girl and stormed off. A week later he killed himself. Then she listened to the tape: it was an apology but also a threat: if she hadn't cared enough to listen to it within a week, he would conclude she didn’t love him… Nine years later, Garner heard a local story – dislocated from history – of Spanish slaves being marched north to build ‘a wall’, who ran away and found refuge on Mow Cop. Could this be a folk memory of the vanished Spanish Legion, the Ninth Hispana? Then there was the chilling history of the Civil War massacre at Barthomley Church, and finally in 1966 some graffiti at Alderley Edge station: two lovers' names and beneath them, written in silver lipstick: ‘Not really now, not any more.' Powsells and thrums: ‘Why should those words bring together all the other items? They come looking for us, or that’s the feeling.’ And so: ‘Red Shift’.

It’s not mysterious, Garner insisted. Creativity, he said, requires intelligence, which is linear and deals with the here and now – but also intuition, which is not under conscious control. Creativity is not polite: ‘It comes barging in and leaves the intellect to clean up the mess.’ Creativity, he said, is risk, and ‘without risk we can only stay as we are.’ What he proposed to give us would therefore be a collection of oddments, powsells and thrums: ‘stories rather than lecture, but woven to an end.’

‘Art interprets the inexplicable.’ The age of the universe is thirteen and a half thousand million years. How do we understand such numbers? The intellect cannot help. We must turn to stories, such as this: Far, far away there is a diamond mountain, two miles high, two miles wide and two miles deep. Every hundred years a little bird comes and sharpens its beak on the top of it, with two little strokes: whet, whet! and flies away. When by this process the entire mountain has been worn away to the size of a grain of sand – then, the first second of eternity will be at an end.

In 1957 Alan sat in his ancient farmhouse, Toad Hall, looking across the fields at Jodrell Bank’s recently completed Lovell Telescope and turning a ‘black pebble’ in his hand – a 500,000 year-old stone axe. ‘The telescope was moving – alert. It was watching a quasar… I needed to know the telescope.’ He went to see Bernard Lovell, taking with him another axe, three and a half thousand years old, beautifully polished and shaped with a hole bored through it for the haft. (Where did he find these axes? I should love to know.) With the words ‘I have something to show you,’ he dropped the axe on Lovell’s desk. ‘Thisis the telescope.’

Sir Bernard gave him a pass, understanding what he meant.

The axe is the forerunner of the telescope.