Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 18

May 18, 2017

Song of the Winter King

Song of the Winter King

1

Hair of crystal and hands of iceThe snow sieves down above him,He shakes in his palm two silver diceAnd whoever sees him loves him.

Now one of the dice is marked with a cross,The other is marked with a ring –And the cross is the seal of paradiseWhere the holy angels sing,

But the ring is the seal of the fairy queen,Queen Morgan is her name,Who dresses in red and elfin greenWho rules in fair Elfhame.

She and her train come riding byIn cloaks as red as blood:She lashes her seamed and grunting sowWith a switch of elder wood,

‘O young snow king, shake down your dice,Find what the chance shall be!’He shakes them once, he shakes them twice,He shakes them three times three –

O silver, silver fall the moonAnd golden fall the sun –The nine bright planets in the skyLeaped as Queen Morgan won.

Hair of crystal, hands of ice,The white snow falls about him.He drops from his palm the silver dice,Queen Morgan cannot doubt him.

She leads him up, she leads him downOver the Seven DaysWhere toothed heads grin from every pool And quickfire beacons blaze,

She leads him up, she leads him downOver the Seven DaysWhere toothed heads grin from every pool And quickfire beacons blaze,Under the hill, the hollow hill,The peaty darkness waits:She leads him down the fairy roadBehind the narrow gates,

She seats him by a dropping poolWhere ghostly fishes glide,‘And here you’ll stay for evermoreBy the dark fountain side.’

Hair of crystal and hands of ice,He counts the fishes’ scales,He strokes their armoured, slimy sides,Tickles their filmy tails.

2

Now Mary Queen of ParadiseOne day came riding byHer robe was made of fine new woolThe colour of the sky,

Light as a loaf she sat uponA milky-mouthed young lambAs big as any dappled horseThat pulls the plough for man.

She saw the double land lie warmUnder the standing sun – All the white spires of Castle CloudIn the blue distance shone.

Long, long the heath before her stretched,The clear miles shook with heat,Anemones like drops of bloodSprang up beneath her feet,And where she passed, the grinning headsPlopped back into the water.Said she, ‘I would the Queen of FaysWere one of Heaven’s daughters,’And all the harebells rang for her.She left the lamb to graze,Went strolling on the hollow hillsBehind the Seven Days And spied the dice like burning ice,Smoking where they lay.

Swift through the golden grate she stepsAnd down the golden stair:All the white daisies craned their necks To see her enter there;

Under the hollow hills she passed And called the young king’s name.Before the echoes copied her,The fairy challenge came: Queen Morgan as a cloud of bees,Then a red bitch, but lame:Last as a lady tall and proudTo rival Mary’s fame.

‘Why have you come, you Queen of HeavenWithin this land of mine?You may not steal the silver king,For he is none of thine.

‘He shook the dice and fell to me,Body and life and soul,And here he’ll sit for evermoreBy the dark fountain’s bowl.

‘He shook the dice and fell to me:I won the winter king.He shall be mine for evermore,Till these dumb fishes sing.’

‘You won his life but not his soul,’Tall Mary answered free, ‘For that was bought with iron cold Upon a hawthorn tree.

‘Keep what you can, but for my part,What I can do, I will’ – Shakes in her hand the crossways diceThrice, thrice beneath the hill –

And shadows fly, and blazing lightLeaps for the young king’s sake:‘Until the fishes sing, you sleep,But then you shall awake.’

Hair of crystal, hands of iceThe snow sieves down above him.Stone in the crystal cave he lies, And nobody sees or loves him,

And he dreams no dream, but the fishes dreamOne day they will wake the kingWhen they poke their red snouts out of the pool,And open their mouths and sing.

© Katherine Langrish 2017

Illustrations

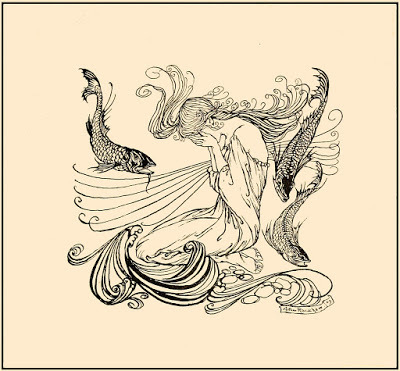

Knight in pen and ink by Aubrey Beardsley, illustration from the Morte d'Arthur, 1909, V&A

Other illustrations by Aubrey Beardsley: facsimile edition of his Morte d'Arthur, Dent 1990.

Published on May 18, 2017 01:06

April 27, 2017

The Magical SATOR Square

In Lady Wilde’s ‘Ancient Legends of Ireland’ there’s a story about a young man, a poet, who attempts to seduce a farmer’s daughter. He’s used to having his wicked way with girls, for we're told that Irish poets were known for possessing ‘the power of fascination by the glance … so that they could make themselves loved and followed by any girl they liked.’

With this particular girl, however, the power doesn’t seem to work very well at first. The poet arrives at her farm and begs for a drink of milk, but the young woman happens to be on her own in the house – the maids are busy churning in the dairy – so she refuses to let him in. Annoyed by this, the poet takes action. Lady Wilde continues:

The young poet fixed his eyes earnestly on her face for some time in silence, then slowly turning round left the house and walked towards a small grove of trees just opposite. There he stood for a few moments resting against a tree, and facing the house as if to take one more vengeful or admiring glance, then went his way without once turning round.

The young girl had been watching him from the window, and the moment he moved she passed out of the door like one in a dream, and followed him slowly, step by step, down the avenue.

As the girl passes through the farmyard, the dairymaids notice her entranced state. They raise the alarm and her father comes running from his work, shouting for her to stop, but his daughter doesn’t seem able to hear. The poet does, though,

…and seeing the whole family in pursuit, quickened his pace, first glancing fixedly at the girl for a moment. Immediately she sprang towards him, and they were both almost out of sight, when one of the maids espied a piece of paper tied to a branch of the tree where the poet had rested. From curiosity she took it down, and the moment the knot was untied, the farmer’s daughter suddenly stopped, became quite still, and when her father came up she allowed him to lead her back to the house.

Recovering, the girl tells her family how she’d felt impelled to follow the young man ‘wherever he might lead’, only coming to her senses when the spell was broken. But what was the spell?

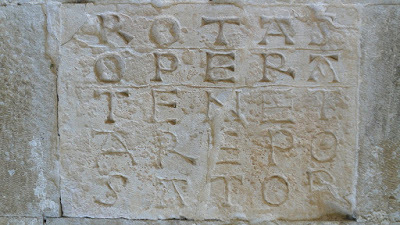

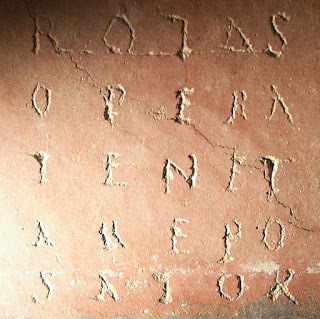

The paper, on being opened, was found to contain five mysterious words written in blood, and in this order:SatorArepoTenetOperaRotas

These letters are so arranged that read in any way, right to left, left to right, up or down, the same words are produced; and when written in blood with a pen made of an eagle’s feather, they form a charm which no woman (it is said) can resist…

(In a sceptical aside, Lady Gregory adds, ‘but the incredulous reader can easily test the truth of this assertion for himself.’)

The Sator, Rotas, or Rotas Sator Square as this acrostic is called, is both very old and tantalisingly obscure; at any rate, no one has yet succeeded in explaining to everyone else’s satisfaction exactly what it means. Carved in stone or painted on walls, it crops up all over the place, at sites in Italy, Britain, Sweden and even Syria, ranging in date from Roman to medieval to near-modern. The words are obscure in themselves and have given rise to various tortuous interpretations (explored in this interesting article by Duncan Fishwick MA, "An Early Christian Cryptogram?"), which range from the reassuringly rural though still opaque, ‘The sower Arepo works the wheels with care’ – to Satanic invocations. AREPO is a nonsense word, and it seems that the rest, though they may resemble Latin words, are so ungrammatical as to be pretty much nonsense too.

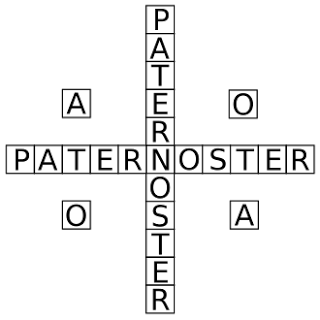

However, back in the 1920s two German scholars discovered (or re-discovered) that the Square hides an anagram: it can be arranged as the word PATERNOSTER written twice in a cruciform order which uses the N only once, and leaves four letters over: two As and two Os – Alpha and Omega.

There’s really no chance that this is not deliberate, but to assume a Christian solution is problematic. The earliest known examples of the SATOR square are two graffiti from Pompeii which predate the Vesuvian eruption of AD 79. Duncan Fishwick summarises the difficulties thus: there's no convincing evidence of any Christians in Pompeii before it was destroyed; the Cross is not found as a Christian symbol before about AD 130; Christians of the First Century used Greek not Latin for teaching and liturgy; the Christian use of Alpha and Omega as symbols for God was inspired by verses of the Apocalypse, which by AD 79 had not yet been written; finally, ‘cryptic’ Christian symbols first appear only ‘during the persecutions of the third century’ when overt Christianity had become politically unsafe.

There was however a Jewish population in and around Pompeii, as various graffiti testify, and Fishwick suggests that rather than Christian, the Sator Square may have been Jewish in origin. The Alpha and Omega may derive their significance from Old Testament passages such as Isaiah 44, 6 in which God declares, ‘I am the first and the last’, while as for the Paternoster anagram, Fishwick explains that, ‘Far from being a Christian innovation this form of address [eg: 'Our Father'] has its roots in Judaism’, citing various Judaic prayers. He concludes that the Square may likely have been a charm constructed by Latin-speaking Jews, the magic of which resides in its satisfying symmetry and the concealed invocation which, revolving around the single letter N, hints at the unspoken nomen or name of God. Another scholar, Rebecca Benefiel, points out in a fascinating article, "Magic Squares, Alphabet Jumbles, Riddles and more: The culture of word-games among the graffiti of Pompeii," that the Sator Square is only one of many different word-squares found at Pompei.

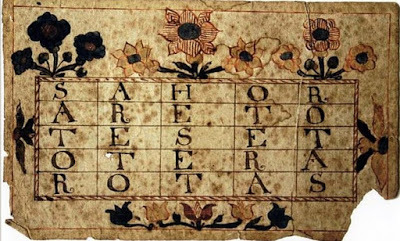

Even if not Christian in origin, the Square was soon adopted as a Christian charm and invested with more specifically Christian symbolism: a belief arose that the five 'words' of the palindrome were the names of the five nails which fastened Christ to the cross. And it went on from there to enjoy a long subsequent history as a potent magical spell. It was used in the 12th century, according to medieval scholar Monica Green (quoted by Sarah E. Bond in a post, 'Power of the Palindrome', in her blog History from Below), as a charm which could be written on butter and eaten, to help women who had miscarried. At some time in the 18th century the Sator Square was brought from Germany to America: in the Pennsylvanian Dutch example shown below, dated circa 1790, you can see that mistakes have been made in the lettering, so that it becomes simply a piece of magical gibberish. One wonders how early any awareness of the Paternoster anagram had vanished.

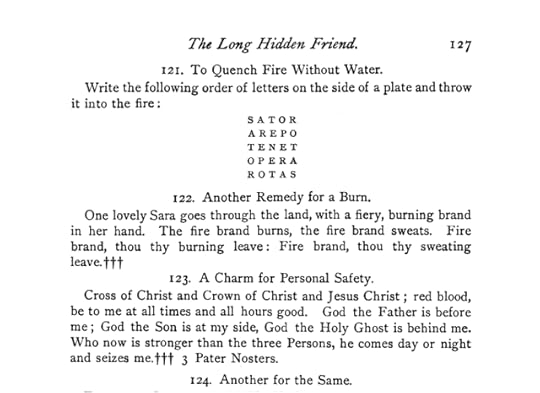

In 1820 printer and chapbook seller, Pennsylvanian John or Johann Hohman published German and English versions of a book of spells, charms and remedies called 'The Long Lost Friend' or 'The Long Hidden Friend'. On the page reproduced below, we find in charm number 121 the Sator Square, used 'To Quench Fire Without Water':

It's clear that people tried it. The photo above, from the Oberhausmuseum in Passau, Bavaria, shows 'a plate with magic inscription, used as a fire fighting device to expel the evil spirits of fire.' Perhaps people prepared them in advance? I suppose it might even have worked to damp out a very small fire, but one hopes those who tried this charm were busy stamping out the flames at the same time. (At least it's fairly brief, unlike the elaborate spell Hohman provides for 'Preventing Conflagration' which involved throwing into the fire a bundled-up sheet stained either with the menstrual blood of a chaste virgin, or the blood from child-birth.)

A charm written on wood, intended to put out fires

A charm written on wood, intended to put out firesIn fact 'The Long-Hidden Friend' itself had a long history as a popular folk-magic text: as late as 1904, Carlton F. Brown wrote in The Journal of American Folk-lore (Vol. 17, No. 65, Apr. - Jun., 1904, pp 89-152) that 'in eastern Pennsylvania whole communities, even whole counties, firmly believe in the realities of "hexing", and protect themselves from its influence by the charms and incantations of witch doctors.' Subsequent investigation by the Berks County Medical Society into the practices of the witch doctors showed that 'the principal source of the charms which they were using was this very book of Hohman's.' And they charged high prices for their services.

Who would have thought that a word puzzle dating from at least as early as first century Pompeii would still be in use as a popular charm in 19th century America, and appear in a 19th century Irish folk tale? Whether Judaic or Christian, Roman or medieval, European or American – whether religious symbol, magical aid for women in childbirth, a charm to put out fires or a spell to lure young Irishwomen away – the Sator Square will surely continue to puzzle and intrigue.

Picture credits

Fair Rosamund, by Arthur Hughes, 1854. (So no real connection with Lady Wilde's story, but a sweet young woman in a summer garden with something doomful looming.)Rotas square from St Peter ad Orotarium, Capestrano, photo by Poecus, at Wikimedia CommonsRotas square from Cirencester, photo by ThrowawayHack, at Wikimedia CommonsPennsylvania Dutch talisman c. 1790, Wikimedia Commons Plate from Passau, Bavaria, with Sator charm against fire, photo by Wolfgang Sauber at Wikimedia Commons Sator square from Freistadt, Austria: Mühlviertler Schlossmuseum: Magic formula against fire, photo by Wolfgang Sauber, Wikimedia Commons

Published on April 27, 2017 04:17

April 6, 2017

'The Museum of Shadows and Reflections' by Claire Dean: Review

Claire Dean’s fairy stories are for adults, not because anything in them is inappropriate for children, simply because most children would find them difficult to understand. Much is left hanging in the air, hinted yet unsaid. I was already familiar with a few of the stories which have previously appeared in various new fairy tale journals, and the words I’d have used to describe them would have been ‘beautiful', 'airy', 'delicate’. Now, ‘delicate’ is a word that isn’t always welcome: it can signal ‘slight’; surely ‘delicate’ rules out ‘powerful’? Well, Hans Christian Andersen could write beautiful, airy, delicate fairy tales which have the emotional kick of a mule. At her best so can Dean, and this collection showcases a very talented writer whose work is getting better and better. The illustrations by Laura Rae perfectly complement the text.

‘You have to catch their coats while they’re young’ is the mantra of a faded and nameless north-country village where most of the locals are married to or descended from swan maidens. In ‘Feather Girls’ a man makes an habitual visit to the local pub to share a couple of pints and a packet of crisps with the swan-maid whom, unlike the other village men, he has refused to trap. In Dean’s elegant, sharp writing the ‘feather girl’ comes to life, ‘tall and slight in her downy white under dress, and she compulsively twiddled her fingers, as though when she had them she couldn’t bear not to be using them’. And ‘she plucked at the crisps … as though her fingers became her beak and her long thin arm took the place of her graceful neck’. It’s a story about love, loneliness and the price of freedom: it’s also perhaps a story about the way custom turns the strangest things into the quotidian. But I was left asking myself why the feather girl would join the man at all? How far should gratitude for not being enslaved take you? Is she sorry for him? Are there no feather men in the lake?

People in Dean’s stories tend to be nameless: often only the subsidiary characters have names. In traditional fairy tales it’s usual for the main character to be ‘the boy’, ‘the maiden’, ‘the king's daughter’, and so universal rather than particular. Dean takes this further towards anonymity by referring to her characters with simple pronouns: ‘he’, ‘she’. It usually works I think, but occasionally the anonymity can get a little characterless. The opening story, ‘Raven’, is based on another animal transformation tale, ‘The Raven’ from the Brothers Grimm. An exhausted mother wishes her restless child would change into a raven and fly away. In the traditional fairy tale this is the beginning of magical adventures out in the forest. Dean shows the interaction of raven-child and mother within doors, within the domestic setting. The bird-baby is active, full of energy, curiosity, boldness; the mother is passive: she copes better with the raven than she did with the child, but is emotionally numb:

I watched her watch the flock of ravens as they flew out of sight over the terraced roofs, chasing wind-torn scrags of cloud. I was still holding my arms as though to cradle her and support her head.

It’s very dreamlike. ‘I watched her’; ‘I was still holding my arms as though to cradle her’ – such physical stiffness and inability to react seem at odds with the vigorous, lively descriptions of the first-person narration. The mother seems to feel neither surprise nor responsibility for her daughter’s transformation, though maybe that too is the point: the baby has always felt alien to her.

In ‘Growing Cities,’ a little girl visits the greenhouse where her Granddad grows cities from seed. A woman who works in the seaside ‘Museum of Shadows and Reflections’ takes an unexpected revenge when she is overlooked for a position. In the lovely ‘Chorlton-under-Water’ a resident clings on to life in her own home even after it’s been submerged in the new reservoir, and ‘A Book Tale’ is a charming, topsy-turvy, inside-out story reminiscent of traditional fairy tales in which girls travel east of the sun, west of the moon to rescue their lovers, or fall down wells into fairy kingdoms. These are all delightful, and there are many more.

I did occasionally wish Dean had drawn with bolder strokes: when she does, the effect is electrifying. The best stories in the collection are also the most recent. ‘The Sand Ship’ is a splendidly weird tale about the power of imagination, narrated by a bossy, rather unpleasant little boy as he plays with his sister on a toy ship in a playground. It’s tough and funny and I loved the sudden, surreal ending. In ‘The Stone Sea’, the growing, miniature stone seafront (complete with stone funfair) in Rivalyn’s living room seems to parallel the gradual petrification and loss of her memory. Finally, ‘Glass, Bricks, Dust’ is outstanding: a softly sinister tale of a boy playing alone on a mound of rubble by a demolition site: ‘At the top of the mound he was king.’ On summer evenings he stays out late, making play cities from bits of broken glass, ‘balancing roofs on them, building towers’. As dusk is falling,

He heard nine chimes of the town hall clock. For a moment, the lamppost looked like a tall thin man wearing a large black hat. When the man turned towards him, he looked like a lamppost… face to face with the boy with his feet still planted in the pavement.

Dark and utterly assured, this story has the strength and coherence of Neil Gaiman’s ‘Coraline’ and is a terrific achievement. ‘The Museum of Shadows and Reflections’ is a collection of beautiful, disturbing stories which will bear reading and rereading. I unreservedly recommend it and look forward to whatever this author does next.

THE MUSEUM OF SHADOWS AND REFLECTIONS by Claire Dean, illustrated by Laura Rae, is published by Unsettling Wonder and available from Amazon (click here)

Read more about it, and other publications, at Unsettling Wonder's website (click here)

Published on April 06, 2017 01:36

March 30, 2017

Here Be Griffins!

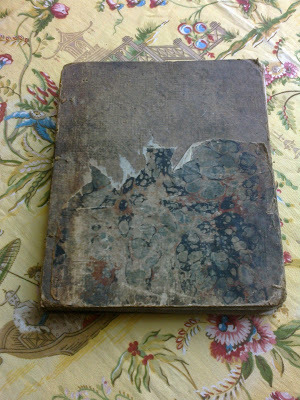

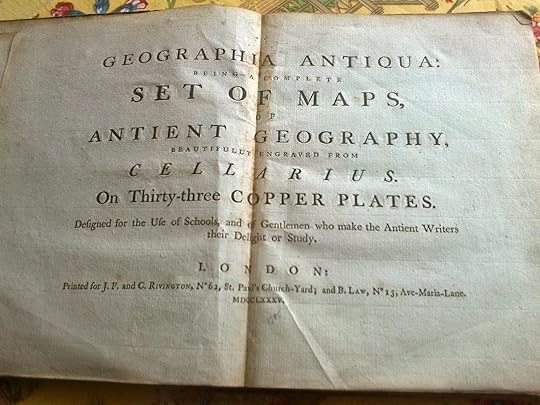

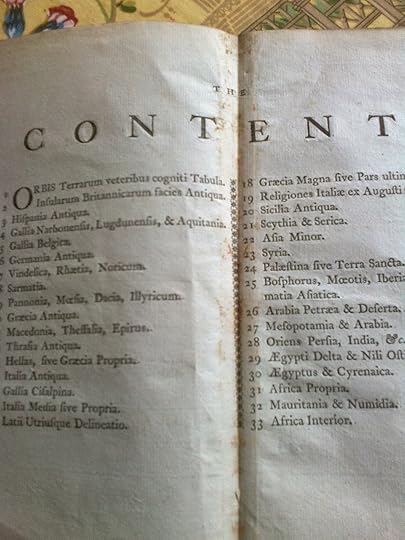

Some years ago my mother handed over to me this book, which had been my grandfather's. I suppose it must have been given to him by someone else - in fact, it must have been handed down for generations.

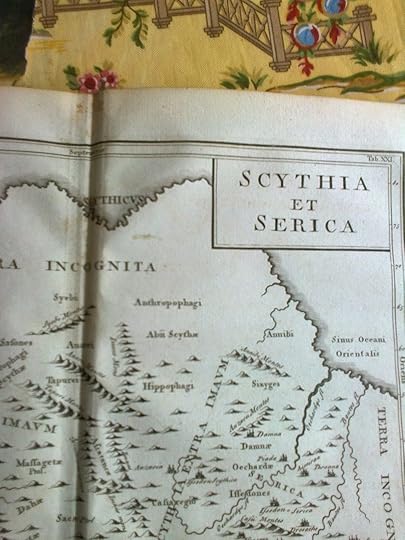

It's an atlas of the classical world dated 1785, 'Designed for the Ufe of Schools, and of Gentlemen who make the Antient Writers their Delight or Study.' The maps cover all areas which such Gentlemen might wish to consult while following the journeys of Herodotus, or perhaps the campaigns of Alexander, or the Gallic Wars.

Of course the maps are deliberately limited to those parts of the world known to ancient geographers, but they aren't themselves 'Antient'. They're drawn to an eighteenth century knowledge of the shapes of coasts and continents.

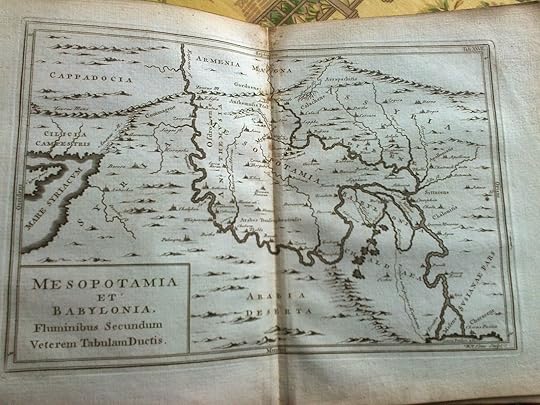

Like any historical atlas of today, they fit the old stories into what was then a modern frame. Here for example is Mesopotamia, with squiggly rivers, the Tigris and the Euphrates. A graceful line of mountains (the Taurus range, somewhat attenuated) drapes itself across the top of the map like a paper-chain.

I wanted to look for griffins, though (or gryphons, griffons, spell as you please), and in a way I found them. In Book Two of Paradise Lost, Milton describes how Satan launches himself out on his 'Sail-broad Vannes' into the abyss of Chaos:

As when a Gryfon through the Wilderness

With winged course ore Hill or moarie Dale,

Pursues the Arimaspian, who by stelth

Had from his wakeful custody purloin’d

The guarded Gold...

All right: who were the Arimaspians? It turns out they come into the first century 'History of Alexander the Great' by Quintus Curtius Rufus: they were also known as the Euergetae, the Benefactors, whose kindness once saved the army of Cyrus the Great of Persia. Alexander, a fan of Cyrus, respected these people for assisting his hero, and he was also impressed by their laws and customs which the 2nd century historian Arrian reports 'had as good a claim to fairness as the best in Greece.' Nothing, sadly, about stealing gold from griffons. That's left to Herodotus, in Book 4 of his History: 'Aristeas ... son of Caystrobius, a native of Proconnesus, says

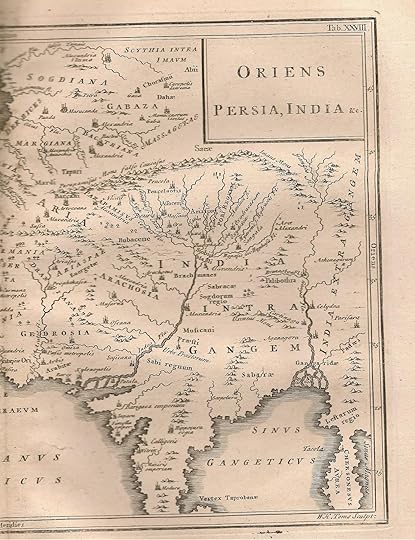

Wow. They have only one eye and still succeed in stealing gold from griffins? But here they are, if you can make out the name: the ARIASPAE [sic] and Euergetae, halfway down the map on the left-hand side. By that way, that graceful curve of mountains just below the legend at the top is named as the Parapamisus Mons and Imaus Mons. That's the Hindu Kush.

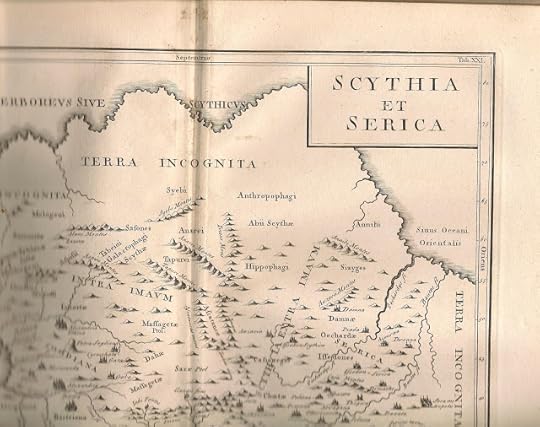

I went hunting for more. Here, at the top of the map of Scythia and Serica (peppered with cities called Alexandria) on the very verge of 'Terra Incognita' - thrilling to see - are the Anthropophagi, Eaters of Men, while below them, fittingly a little less distant, a little less uncivilised, we encounter the Hippophagi, eaters of horseflesh.

Further north, lots of almost ruler-straight lines of mountains are scattered across the map. We really do seem to be somewhere in Middle-earth!

Pliny the Elder describes how the Anthropophagi, 'whom we have previously mentioned as dwelling ten days' journey beyond the Borysthenes, according to the account of Isigonus of Nicæa were in the habit of drinking out of human skulls, and placing the scalps, with the hair attached, upon their breasts, like so many napkins."

It doesn't sound utterly impossible, but I feel that Pliny's next source, Ammianus Marcellinus, may have been embroidering at little when he adds: "And these men are so avoided on account of their horrid food, that all the tribes which were their neighbours have removed to a distance from them. And in this way the whole of that region to the north-east, till you come to the Chinese, is uninhabited." Although that's the China Sea, there, at the eastern edge of the map...

I've always had a soft spot for the Anthropophagi since first meeting them in T.H. White's The Sword in the Stone: Robin Hood explains:

‘Now, men... Tonight the Anthropophagi are holding one of their feasts of sacrifice and it behoves us to slay them at it. You know how many varieties they have. The Scythians, who wrap themselves in their ears, can hear a twig break half a mile away. The Pitanese, who live by smell, can detect a man upwind for three miles. The Nisites, with three or four eyes, can distinguish the faintest movement anywhere. All these men, or beast if you prefer to call them so, are ... armed with poison arrows. Our chances are small.’

Sir John Mandeville knew of creatures like these, living in the Island of Dodyn - not to be found anywhere in my maps, alas - and he had more to say on griffins, this time from Bactria, north of the Arimaspians:

'In that land are trees that bear wool, as it were sheep, of which they make cloth. In this land are ypotains that dwell sometimes on land, sometimes on water, and are half a man and half a horse, and they eat naught but men, when they may get them. In this land are many gryffons, more than in other places, and some say they have the body before as of an Egle, and behind as a Lyon, and it is trouth, for they be made so, but the Griffen hath a body greater than viii Lyons and ... worthier than a hundred Egles. For certainly he will bear to his nest flying, a horse and a man upon his back... for he hath long nayles on his fete, as great as it were hornes of Oxen, and of those they make cups there to drink of, and of his rybes they make bowes to shoot with.'

Ypotains are hippos, I suppose? And the wool growing on trees, might that be cotton, or even silkworm cocoons? Since things so strange turn out really to exist, then why on earth not griffins?

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi...

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi...Marco Polo too had something to say about griffins, which he located - possibly - on the island of Madagascar. In this wonderful early 15th century illustration, we see a number of gentlemen looking on with calm disapproval as a griffin gobbles up a sheep or goat in the background. I love the little white pygmy elephants - which appear to live in burrows? Marco Polo writes:

''Tis said that in those other Islands to the south, which the ships are unable to visit because this strong current prevents their return, is found the bird Gryphon, which appears there at certain seasons. The description given of it is however entirely different from what our stories and pictures make it. For persons who had been there and had seen it told Messer Marco Polo that it was for all the world like an eagle, but one indeed of enormous size; so big in fact that its wings covered an extent of 30 paces, and its quills were 12 paces long, and thick in proportion. And it is so strong that it will seize an elephant in its talons and carry him high into the air, and drop him so that he is smashed to pieces; having so killed him the bird gryphon swoops down on him and eats him at leisure. The people of those isles call the bird Ruc, and it has no other name. So I wot not if this be the real gryphon, or if there be another manner of bird as great. But this I can tell you for certain, that they are not half lion and half bird as our stories do relate; but enormous as they be they are fashioned just like an eagle.'

Such fun for the eighteenth century Gentleman to muse on all this as he sat in his library, drinking his port.

Published on March 30, 2017 01:44

March 8, 2017

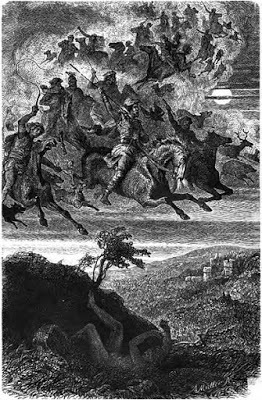

Women who lead the Wild Hunt

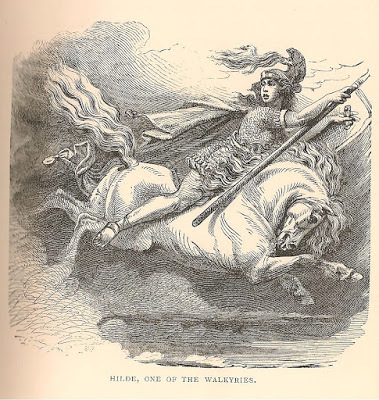

As an appropriate post for International Women's Day, fortuitously following on from my last post - are there any female leaders of the Wild Hunt? The answer is yes, which shouldn’t surprise anyone who’s ever heard of a Valkyrie. Njal’s Saga tells of a man in Caithness named Dorrud, who on Good Friday sees ‘twelve people riding together to a women’s room’ who disappear inside. Looking in, he sees these twelve women working a loom. They are using severed heads for the weights, and intestines for the thread. As they wind the finished cloth on to the loom beam, the women chant a poem known as ‘The Song of the Spear’ which includes these lines:

Valkyries decidewho dies or lives.[…]Let us ride swiftlyon our saddle-less horseshence from herewith swords in hand.

Njal’s Saga, tr. Robert Cook (Penguin Classics)

The women then pull down the cloth and tear it to pieces; each keeping a torn piece in her hand, they climb on their horses and ride away, six to the south and six to the north.

In Gods and Myths of Northern Europe, Hilde Ellis Davidson cites an Old English charm known as Wið færstice (‘Against sudden pain’ – probably cramp or stitch), which visualises the pain as ‘caused by the spears of certain supernatural women’:

Loud were they, lo, loud, riding over the hill.They were of one mind, riding over the land,Shield thyself now, to escape from this ill.Out, little spear, if herein thou be.Under shield of light linden I took up my standWhen the mighty women made ready their powerAnd sent out their screaming spears…

Davidson thinks this may once have been a battle-spell, though the charm addresses supernatural causes of pain – elf-shot, witch-shot, gods’-shot – rather than human. (Cramps do seem to come out of nowhere…) In another Old English charm a swarm of bees is addressed as sigewif, ‘victory-women’. This implies that Anglo-Saxons correctly assumed worker bees to be female, which was neither obvious nor scientifically proved until the late 18th century. At any rate, the image conjured up is a flying host of warrior women, armed of course with stings.

Gold plaques embossed with bee goddesses, 7th C Rhodes. British Museum

Gold plaques embossed with bee goddesses, 7th C Rhodes. British MuseumIn England, at least one Wild Hunt still possesses a female leader. In Shropshire, the Lady Godda rides the hills forever with her partner Wild Edric at the head of their troop. First found in the late 12thcentury account of Walter Map, the tale tells how the lord of the manor of Ledbury North, Edric Salvage (a real person named in Domesday Book) snatches an unnamed fairy woman he has found dancing with her sisters in a cottage in the woods. She marries him on condition he must never reproach her with her fairy origin: when he breaks this prohibition she vanishes and Edric dies. However, as Katharine Briggs remarks in ‘A Dictionary of Fairies’, ‘Tradition restored him to his wife, and they rode together over the Welsh borders for many centuries after his death.’ To see them was unlucky. Charlotte Burne in ‘Shropshire Folklore’ (1883) knew a servant girl who as a child had seen them with her own eyes: by this time, the fairy lady had acquired a name:

It was in 1853 or 1854 or, just before the Crimean War broke out. She was with her father, a miner, at Minsterley, and she heard the blast of a horn. Her father bade her cover her face, all but her eyes, and on no account speak, lest she should go mad. Then they all came by; Wild Edric himself on a white horse at the head of the band, and the Lady Godda his wife, riding at full speed over the hills.

Hold that thought please, and read this account from Jacob Grimm.

There was once a rich lady of rank named frau Gauden; so passionately she loved the chase, that she let fall the sinful word, ‘could she but always hunt, she cared not to win heaven’. Four-and-twenty daughters had dame Gauden, who all nursed the same desire. One day, as mother and daughters in wild delight hunted over woods and fields and once more that wicked word escaped their lips, that ‘hunting was better than heaven,’ lo, suddenly before their mother’s eyes the daughters’ dresses turn into tufts of fur, their arms into legs, and four-and-twenty bitches bark around their mother’s hunting car, four doing duty as horses, the rest encircling the carriage; and away goes the wild train into the the clouds, there betwixt heaven and earth to hunt unceasingly as they had wished, from day to day, from year to year.

They have long wearied of the wild pursuit, and lament their impious wish, but they must bear the fruits of their guilt till the hour of redemption comes. Come it will, but who knows when? During the twölven* (for at other times we sons of men cannot perceive her) frau Gauden directs her hunt towards human habitations; best of all she loves on the night of Christmas eve or New Year’s eve to drive through the village streets, and wherever she finds a street door open, she sends a dog in. Next morning a little dog wags his tail at the inmates, he does them no other harm but that he disturbs their night’s rest by his whining. He is not to be pacified or driven away. Kill him, and he turns into a stone by day, which, if thrown away, comes back to the house by main force and is a dog again at night. So he whimpers and whines the whole year round, brings sickness and death upon man and beast, and danger of fire to the house; not till the twölven comes round again does peace return to the house.

* twölven: the twelve nights of Yule or Christmas

Frau Gauden and the Lady Godda are both supernatural wild huntresses and the names are surely too similar to be coincidence. But who was Frau Gauden? Grimm continues with another story.

Frau Gauden and the Lady Godda are both supernatural wild huntresses and the names are surely too similar to be coincidence. But who was Frau Gauden? Grimm continues with another story. Better luck befalls those who do dame Gauden a service. It happens at times that in the darkness of night she misses her way and comes to a crossroad. Crossroads are to the good lady a stone of stumbling: every time she strays into such, some part of her carriage breaks, which she cannot herself rectify. In this dilemma she was once when she came, dressed as a stately dame, to the bedside of a labourer at Böck, awaked him and implored him to help her in her need. The man was prevailed on, followed her to the crossroads, and found one of her carriage wheels was off. He put the matter to rights, and by way of thanks for his trouble she bade him gather up in his pockets sundry deposits left by her canine attendants during their stay at the crossroads, whether as the effect of great dread or of good digestion. The man was indignant at the proposal … incredulous, yet curious, he took some with him. And lo, at daybreak, to his no small amazement, his earnings glittered like gold, and in fact it was gold. He was sorry now that he had not brought it all away.

Notable here (apart from the enjoyable comic element) is that though like the Valkyries, Godda rides a horse, Frau Gauden travels in a wagon, which seems a cumbersome thing to go hunting in.

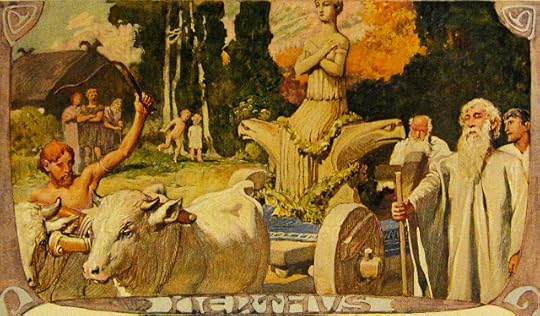

But here is a goddess or priestess riding on a wagon. It’s made of bronze and was found in a cremation grave of the 7th century BC, near Strettweg in Austria. The female figure in the middle who supports an offering bowl towers above a crowd of smaller figurines, male and female, some on horses. Facing outwards at both the front and back is a stag flanked by figures of indeterminate sex who are holding its antlers. There is of course no knowing for sure what all this may have meant, or of connecting it in any direct way to the Wild Hunt or to the wagons of Frau Gauden or Frau Holle. But deities in wagons are certainly known from prehistory. The Norse gods called the Vanir presided over fertility and the domestic arts: the two most powerful were brother and sister Freyr and Freyja – titles which mean simply ‘Lord’ and ‘Lady’, and from which the word ‘Frau’ is derived.

If a sly story told in the 14thcentury Icelandic Flateyjarbòk (the ‘Flat Island Book’) has any truth in it, an image of Freyr used to be taken about the Swedish countryside in a wagon accompanied by a priestess: the wagon gets stuck in a snowstorm and all the attendants desert it except the priestess and a young man called Gunnar. The two keep each other warm in the time-honoured way: a few months later when the priestess is discovered to be with child, the worshippers are delighted at the fertility of their ‘god’. It’s quite possible that Freyr’s sister Freyja also travelled in a wagon. A beautifully carved ceremonial wagon was placed in the Oseberg ship, itself the burial-place of two high-status women who may have been priestesses. Carefully dismantled wagons have been found in Danish bogs, presumably cult offerings.

The Roman historian Tacitus (AD 56-120) tells of a Danish goddess, Nerthus, who represented ‘Mother Earth’ and whose occasional dwelling was a sacred wagon in a grove of trees on an island:

One priest, and only one, may touch it. It is he who becomes aware when the goddess is present in her holy seat; he harnesses a yoke of heifers to the car, and follows in attendance with reverent mien. Then are the days of festival, and all places which she honours with her presence keep holiday. Men lay aside their arms and go not to war; all iron is locked away … until the priest restores her to her temple, when she has had enough of her converse with mortals. Then the car and the robes and (if we choose to believe them) the goddess herself are washed in a mystic pool. Slaves are the ministers of this office, and are forthwith drowned in the pool. Dark terror springs from this, and a sacred mystery surrounds those rites which no man is permitted to look upon.

Tacitus, Germania, 40, tr. RB Townshend, 1894

Wagons are associated with another supernatural woman, Frau Holda. Grimm suggests she is originally a sky deity associated with the weather – and therefore able to move through the air. She appears in the Grimms fairytales as the kindly but powerful Mother Holle (KHM 24) whose country the heroine arrives at by jumping down a well.

At last she came to a little house, out of which an old woman peeped; but she had such large teeth that the girl was frightened, and was about to run away. But the old woman called out to her, ‘What are you afraid of, dear child? Stay with me; if you will do all the work in the house properly, you shall be the better for it. Only you must take care to make my bed well, and to shake it thoroughly till the feathers fly – for then there is snow on the earth. I am Mother Holle.’

'The Old Woman is plucking her geese' was the phrase my mother used when I was small... In a story very similar to the one about Frau Gauden, Mother Holle needs the linchpin of her wagon mended, and rewards the helpful peasant with the woodshavings left from his work: these too turn to solid gold.

But Holda had her dark side. ‘At other times,’Jacob Grimm continues, ‘Holda, like Wotan, can also ride on the winds, clothed in terror, and she, like the god, belongs to the ‘wütende heer’ [furious army]. From this arose the fancy, that witches ride in Holle’s company … in Upper Hesse and the Westerwald, Holle-riding, to ride with Holle, is equivalent to the witches’ ride.’ The souls of unbaptised infants were held to join Holle’s wild company.

The unnamed author of a 9thcentury document called the Canon Episcopi denounces the the wicked folly of those who believe in witches and their power. ‘Have you shared in a superstition to which some wicked women have given themselves?’ he demands. ‘Fooled by demonic phantasms, they believe themselves in the hours of the night to ride with Diana the pagan goddess, with Herodias and with innumerable other women, mounted on the backs of animals and travelling great distances in the silence of the night.’

Diana or Artemis is an obvious Wild Huntress. Nor is it surprising that a cleric should place Herodias in the witches' wild hunt, though it’s worth noting his main point is that witches don’t exist, not that they do. (It took a long time for the church to pass from this relatively healthy scepticism to the crazed witchhunts of later centuries). Herodias is the name given in the Middle Ages to the girl who danced before Herod and asked him for the head of John the Baptist. Though known today as Salome, that name is not in the Gospels; some Greek versions read ‘Herod’s daughter Herodias’, while in the Latin she is named only ‘the girl’ or ‘the daughter of Herodias’ - who was her mother. Jacob Grimm suggests that Herodias ‘was dragged into the circle of night-women … because she played and danced, and since her death goes booming through the air as the “wind’s bride”.’ Medieval poets really went to town on Salome/Herodias’ fate; Grimm quotes from a medieval Latin poem which tells how

From midnight to first cock-crow she sits on oaks and hazel-trees, the rest of her time she floats through the empty air. She was inflamed by love for John which he did not return: when his head is brought in on a charger she would fain have covered it with tears and kisses, but it draws back and begins to blow at her; she is whirled into empty space and there she hangs forever.

Frau Gauden and Frau Holle both have connections with crossroads. One of the many titles of the Greek goddess Hecate was ‘She of the crossroads’, and she was represented as three bodied, able to face in all directions. Dogs were sacred to her, and she presided over thresholds and crossing-places, including the threshold between life and death. The dog is of course the guard-dog of the threshold into the underworld. According to Everyman’s Classical Dictionary Hecate was probably ‘a pre-Hellenic chthonian deity’ and Hesiod represents her as able, like the Norse Vanir, to gift mankind with wealth and all the blessings of daily life. With her troop of ghosts and hell-hounds she visited crossroads where offerings of meat, eggs and fish were left for her. And in the 3rd century BC Argonautica, Medea tells Jason to sacrifice a ewe to Hecate, pour honey over the offering and leave without looking back – even if he hears the sound of footsteps or the baying of hounds. (Argonautica Book III lines 1020-1040)

Finally, what about the Breton legend of the Ankou who drives about the countryside in a cart, picking up souls? ‘At night,’ says Sabine Baring-Gould, ‘ a wain is heard coming along the road with a creaking axle. It halts at the door, and that is the summons.’ The Ankou is a male figure, but as Baring Gould points out:

The wagon of the Ankou is like the death-coach that one hears of in Devon and Wales. It is all black, with black horses drawing it, driven by a headless coachman. A black hound runs before it, and within sits a lady – in the neighbourhood of Okehampton and Tavistock she is supposed to be a certain Lady Howard, but she is assuredly a personification of Death, for the coach stops to pick up the spirits of the dying.

This seems to bring us back to the valkyries again – the choosers of the slain.

It’s hardly possible or even desirable to come up with a single explanation for stories of the Wild Hunt, but it does seem to me that its female leaders are even more complex in origin than the males. The leaders of most British Wild Hunts have assumed the names and characters of local heroes such as Edric Salvage, Hereward, King Arthur, Sir Francis Drake, a tendency which makes them somehow easier to grasp, more comprehensible. But the only remaining British Wild Huntress, Lady Godda, has a name similar to the German Frau Gauden, stories of whom include items – wagons, dogs, crossroads – reminiscent of ancient goddesses such as Nerthus and Hecate who held sway over domestic affairs such as fertility and farming, which literally implies over life and death. And since the Wild Hunt has always been associated with death, its appearance in tales from Germany and Scandinavia also suggest the weaving in of a separate strand of bloody battle-spirits. Hilda Davidson thinks the valkyries may originally have been believed to devour the dead of the battlefield, rather than merely, as later, to escort them to Valhalla.

Herodias, whirling in the windy blast from the lips of John the Baptist’s severed head – Frau Gauden with her carriage and her dogs and their golden poo – Lady Godda riding on her white horse in her green gown like many a later Queen of Elfland – the phantasmal spear-women galloping over the hill while drops of blood shake from their horses’ manes – the lady in the black death-coach – these are wonderfully various stories which deserve to be better known.

Picture credits

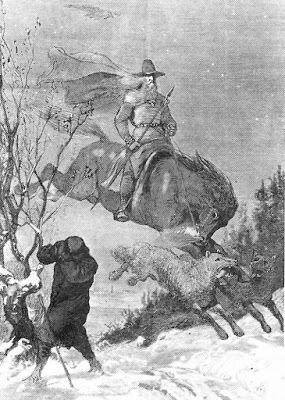

Hilde, one of the valkyries, by Ludwig Pietsch, 1894

Frigga or Frau Gode hunting, by Ludwig Pietsch, 1894

Gold plaques embossed with winged bee goddesses, perhaps the Thriai, found at Camiros Rhodes, dated to 7th century BCE (British Museum)

Strettweg cult wagon, photo by Thilo Parg, Wikimedia Commons

Nerthus in her wagon, by Emile Doepler (1855-1922)

Goldmarie shaking Mother Holle's bedding, by Herman Vogel (1854-1921)

The Wild Hunt, by Peter Nicolai Arbo, 1831-1892

Salome dancing before Herod, by Gustave Moreau, Wikimedia Commons

Valkyries leading the slain to Valhalla, by Ludwig Pietsch, 1894

Published on March 08, 2017 02:39

February 16, 2017

Wodan and the Peasant

There is a great story about the Wild Hunt in Jacob Grimm’s ‘Teutonic Mythology’:

That the wild hunter is to be referred to as Wôdan, is made perfectly clear by some Mecklenburg legends. Often of a dark night the airy hounds will bark on open heaths, in thickets, at cross-roads. The countryman well knows their leader Wod, and pities the wayfarer who has not reached his home yet; for Wod is spiteful, seldom merciful. It is only those who keep in the middle of the road that the rough hunter will do nothing to; that is why he calls out to travellers: ‘midden in den weg!’

A peasant was coming home drunk one night from town, and his road led him through a wood; there he hears the wild hunt, the uproar of the hounds and the shout of the huntsman up in the air: ‘midden in den weg!’ cries the voice, but he takes no notice. Suddenly out of the clouds there plunges down, right before him, a tall man on a white horse. ‘Are you strong?’ says he, ‘here, catch hold of this chain, we’ll see which can pull the hardest.’ The peasant courageously grasped the heavy chain, and up flew the wild hunter into the air. The man twisted the end round an oak that was near, and the hunter tugged in vain.

‘Haven’t you tied your end to the oak?’ asked Wod, coming down. ‘No,’ replied the peasant, ‘look, I am holding it in my hands.’ ‘Then you’ll be mine up in the clouds,’ cried the hunter as he swung himself aloft. The peasant hurriedly knotted the chain around the oak again, and Wod could not manage it. ‘You must have passed it around the tree!’ said Wod, plunging down. ‘Not I,’ said the peasant, who had deftly disengaged it, ‘here I have it in my hands.’ ‘Were you heavier than lead, you must up to the clouds with me!’ He rushed up quick as lightning, but the peasant managed as before. The dogs yelled, the waggons rumbled and the horses neighed overhead; the tree crackled to its roots and seemed to twist round. The man’s heart began to sink, but no, the oak stood its ground.

‘Well pulled!’ said the hunter, ‘many’s the man I have made mine, you are the first that ever held out against me, you shall have your reward.’ On went the hunt, full cry: hallo, holla, wol, wol! The peasant was slinking away, when from unseen heights a stag fell groaning at his feet and there was Wod, who leaps off his white horse and cuts up the game. ‘Thou shalt have some blood, and a hindquarter to boot.’ ‘My lord,’ stammered the peasant, ‘thy servant has neither pot nor pail.’ ‘Pull off thy boot,’ cries Wod. The man did so. ‘Now walk, with blood and flesh, to wife and child.’

At first, terror made the load seem light, but presently it grew heavier and heavier and he had hardly strength to carry it. Bent double and bathed in sweat at last he reached his cottage and behold! – the boot was filled with gold, and the hindquarter was a leather pouch full of silver.

‘Teutonic Mythology’ Book III p924

I love the humour in this story: first that the powerful and terrifying hunting god is still too simple to realise that the peasant is tricking him; then the unwelcome gift of raw flesh and blood, of supernatural and uncertain origin, which the peasant must lug painfully home. (In other stories, the Hunt pursues harmless little creatures called woodwives, and sometimes a quartered woodwife will be hung up as a horrifying gift beside a helpful peasant's door.) One feels this peasant thoroughly deserves its fairy transformation into silver and gold once Wodan's little joke is over.

In a very excellent book, ‘European Paganism’ (Ken Dowden, Routledge 2000) provides a comprehensive, fact-based overview of just about everything that is actually known about pagan Europe. At one point Dowden, an academic at the University of Birmingham, discusses a type of Gaulish priest described by the Greek writer Poseidonius as wateis (specifically distinguished from druids or bards). Dowden explains the meaning of the term:

Wateis is evidently the same as the Latin vates, a rather olde-worlde word denoting a prophet or seer, but in any case implying some inspiration: the Gothic word is wods, ‘frenzied or possessed’, as in the German Wodan or the daemonic Wütende Heer [furious army] that is let loose at Yule.

European Paganism, p236

In English, the meaning of ‘wode’ or ‘wood’ as ‘mad’ survived at least into the late 16th century. In ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ Demetrius exclaims that he’s crazy for love of Hermia:

And here am I, and wood within this woodBecause I cannot meet my Hermia. Act 2 Sc 1

The word can been traced back all the way to proto-Indo-European where it’s been reconstructed as *weh₂t- with the meanings ‘excited, inspired’, ‘possessed, raging’. So Wodan or Odin is an inspired, prophetic, raging, furious god, and this is certainly how he appears as one – maybe even the first, who knows? – of the many leaders of the European-wide Wild Hunt. Ken Dowden tentatively connects this phenomenon with ancestor worship, and pagan festivals of the dead which were often held at the end of the year:

Evidence for Yule as a pagan religious festival may be slender, but it is so very suggestive that this is the period when the Wild Hunt (Wilde Jagd, or the ‘Raging Army’, Wütende Heer) flies through the air, a spectral army corresponding to the ancestors once worshipped in ritual. Does this awareness of the dead survive in the custom of Serbian coledari (derived from the Latin Kalendae), a sort of masked Christmas-carol group who include in their visits houses where there has been a death during the year, and ‘intone funeral chants and bring news from the departed’? Have they taken on the character of the dead themselves?

European Paganism, p266

Whatever the truth of it, the Wild Hunt has a very long history.

Picture credits:Johann Wilhelm Cordes: Die Wilde Jagd, Wikimedia Commons Friedrich Wilhelm Heine: Wodan's Wild Hunt, Wikimedia Commons August Malmstrom: Odin, Wikimedia Commons Lorenz Frolich:Odin riding Sleipnir with the ravens Huginn and Munin, Wikimedia Commons

Published on February 16, 2017 00:43

January 26, 2017

Folklore and Memory

This is the text of a talk I gave at the University of Warwick, 25th January 2017.

I’m here to talk to you about folklore and memory. What I’m really going to do is tell you a lot of stories, and when we get on to the discussion part of this, I hope you’ll feel able to tell some stories to me. First of all, though, it would be helpful to define some terms. I’m going to assume we have some kind of collective agreement of what memory is or at least what it feels like. Memory is about personal identity: we depend on memories, however fragmentary, for our sense of who we are – which is why it’s so awful when we lose them. But what, please, is folklore?

I want to suggest that folklore can be a form of memory and that memory actually is a form of folklore. Both are fascinating, both can be highly unreliable, and I think both are unreliable-but-powerful forms of history. I’ll try and explain why, as I go on.

Let’s start with family folklore – personal tales passed down to us from our parents and grandparents. Perhaps there was a family tragedy or a wartime adventure, or some memorable act of generosity or betrayal. Most of us know several stories about our parents – anecdotes about their childhood, the story of how they met. We probably know fewer about our grandparents, and quite possibly none at all about our great-grandparents, but family folklore seems to provide a sense of identity. We like to ‘know where we came from’. It gives us roots. One of my grandmothers was brought up in India, where she was born in 1886. She was a great raconteur and extremely pretty even as an old lady. Here she is, aged about eighteen.

Many if not most of her stories involved men whose attentions she had to evade or fight off. Whether consciously or not, she told stories which emphasised her own attractiveness, courage and resource. There was one about encountering four soldiers as she came home from playing tennis (‘All I had with me was my tennis racket, Katherine!’) and another which involved an amorous male in a railway carriage, from whom she escaped with the assistance of an old lady and a parrot. I wish I could remember it, but I was only sixteen or so when she was telling me these stories, and hadn’t really been paying attention. Only the most striking of family tales survive three generations.

Most of the stories of most the people in all the generations before us have been lost. Some are simply forgotten, some are deliberately suppressed. Successful stories by definition are the ones we continue for some reason to value and therefore to tell. Before I go on, let me just say that folklore is a massively inclusive genre. It is quite literally the stuff people tell to one another, from useful stuff such as how to to treat a cough or get bloodstains out of linen, to how to keep on the right side of the fairies or the gods, or God. (Also useful!) Folklore includes myths and legends, songs, skipping rhymes and lullabies – ghost stories and fairy tales and jokes – family history, local history, natural history… All these categories shade into one another. Let’s get some of them out of the way.

First off, I’m not going to be talking today about myths or legends. Myths attempt to make emotional sense of the world and our place in it. (So the story of Persephone’s abduction by Hades is a religious, poetic exploration of the mysteries of winter and summer, death and birth.) Legends recount the deeds of heroes, like Achilles or King Arthur. There are often whole cycles of legends about single outstanding figures.

I’m not going to be talking much about fairy tales either. The difference between folk tales and fairy tales is that fairy tales don’t ask to be believed. They are set far away and long ago. No one’s ever thought there was an historical Little Snow White or tried to point out the ruins of the Sleeping Beauty’s castle. Fairy tales are quite definitely fiction.

A folk tale is a humbler, more local affair. (By the way, as I’m talking today I’m going to be using the terms folk taleand story more or less interchangeably.) A folk tale’s protagonists may be well-known neighbourhood characters or they may be anonymous, but specific places become important. Folk tales happen in real, named landscapes. Green fairy children are found near the village of Woolpit in Suffolk. In Dorset an ex-soldier called John Lawrence sees a phantom army marching ‘from the direction of Flowers Barrow, over Grange Hill, and making for Wareham’. Local hills, lakes, stones and even churches are explained as the work of giants, trolls or the Devil. Folk tales often also involve legendary heroes, because everyone wants to be close to fame.

All over Britain, from Tintagel to Edinburgh and beyond, there are places associated with King Arthur. This is Arthur’s Stone near Dorston, Herefordshire – a Neolithic chamber tomb which according to various stories was either built by Arthur, or was his burial place, or was a place where he fought and buried a rival king. I said that fairy tales don’t ask to be believed. Well, folk tales do. Often – not always, but often – they tug at our sleeves, hinting they contain some kind of truth. We know there wasn’t ever a real Sleeping Beauty. But was there ever a real King Arthur? Was there a real Robin Hood?

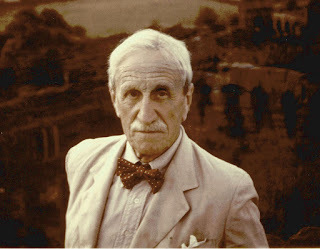

Well, was there? Do folk tales ever preserve ‘genuine’ folk memories? As in, historical truths? Here’s a man who thought not.

This grim-but-dapper-looking gentleman is Fitzroy Richard Somerset, 4th Baron Raglan (1885-1964), amateur anthropologist and one-time President of the Folklore Society. In his 1936 book The Hero: A Study in Tradition, Myth and Drama, he provides a delightfully sceptical example of the way in which a tradition may become attached to a place:

1: ‘This house dates from Elizabethan times, and since it lies close to the road which the Virgin Queen must have taken when travelling from X to Y, it may well have been visited by her.’

2: ‘This house is said to have been visited by Queen Elizabeth on her way from X to Y.’

3: ‘The state bedroom is over the entrance. It is this room which Queen Elizabeth probably occupied when she broke her journey here on her way from X to Y.’

4: ‘According to local tradition, the truth of which there is no reason to doubt, the bed in the room over the entrance is that in which Queen Elizabeth slept when she stayed here on her way from X to Y.’

This is very shrewd and funny. All the same, such a story is going to be hard to kill in any individual case, because the Queen undoubtedly did spend the night in a great many different English country houses, and absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. The owner of the house, who takes pride in this story, is not going to listen to Lord Raglan, casting cold water. The owner wants to believe it.

Stories grow in the telling, too. Here’s another tale. A couple of years ago, BBC Radio 4 ran a series called ‘A History of the World in 100 Objects’. It was organised and written by the British Museum’s director Neil McGregor, and of course there was also a book. Ranging from a 2 million year old African handaxe to a modern solar powered Chinese lamp, McGregor used artefacts in British Museum as the focus for a hundred thoughtful essays on the cultures and circumstances which produced them. Number 19 in the series is this.

It’s a gold cape, it dates from between 1900 to 1600 BC, and it was found near Mold in North Wales in 1833. Here’s how McGregor introduces it:

For the local workmen, it must have seemed as if the old Welsh legends were true. They’d been sent to quarry stone in a field known as Bryn yr Ellyllon, which translates as the Fairies’ Hill or the Goblins’ Hill. Sightings of a ghostly boy, clad in gold, a glittering apparition in the moonlight, had been reported frequently enough for travellers to avoid the hill after dark. As the workmen dug into a large mound, they uncovered a stone-lined grave. In it were hundreds of amber beads, several bronze fragments, and the remains of a skeleton. And wrapped around the skeleton was a mysterious crushed object – a large and finely decorated broken sheet of pure gold.

McGregor goes on to tell how the workmen ‘eagerly shared out chunks’ of the gold, with ‘the tenant farmer taking the largest pieces’, and that it was only ‘three years after the spoils had been divided’ that the BM bought from the tenant farmer ‘the first and largest of the fragments of gold which had been his share of the booty’.

It’s quite a story. I blogged about it myself back in 2013. I wrote:

The mound those workmen were digging into was in a field called Bryn yr Ellyllon, the Hill of the Elves; and the legend of the hill was that it was haunted by a ghostly boy, clad all in gold. Isn’t it possible that the sight of a young man being laid to rest in his shimmering golden cape so impressed and touched the onlookers that for nearly four thousand years if a child said, ‘Mother, who’s buried in that hill?’ the answer was ‘a boy all dressed in gold?’

When my friend the writer Susan Price expressed some scepticism about all this, I did some checking, and unfortunately for me and Mr Neil McGregor, I discovered some problems, even some inaccuracies in this romantic account. The discovery was originally made public on December 17th 1835 when John Gage, FRS, exhibited the flattened remains of the cape to the Society of Antiquaries of London. The cape had been dug up two years and two months previously, on 11th October 1833 (which seems to me like speedy work for the early 19th century) and the tenant farmer – Mr John Langford – had been corresponding with antiquaries about it as early as January 1835, so to represent him as a treasure hunter interested only in ‘booty’ is rather unfair. A further letter of the same year written by the Vicar of Mold, Charles Butler Clough, provides the fullest account.

A short time before the discovery of the Corselet, workmen had … made a considerable pit for some yards into the adjoining field. A new tenant, Mr John Langford … employed persons to fill in the hole by shovelling down the top of the bank. While so employed … about four feet from the top of the bank and without doubt upon the original surface, they perceived the Corselet.

The Vicar goes on to describe the burial in detail and then provides the only evidence for the ghost story.

Connected with this subject, it is certainly a strange circumstance that an elderly woman, who had been to Mold to lead her husband home late at night from a public house, should have seen or fancied, a spectre “of unusual size, and clothed in a coat of gold, which shone like the sun” to have crossed the road before her to the identical mound of gravel, and that she should tell the story next morning many years ago, amongst others to the very person, Mr John Langland, whose workmen drew the treasure out of its prison-house. Her having related such a story is an undoubted fact. I cannot, however, learn that there was any tradition of such an interment having taken place; though possibly this old woman might have heard something of the kind in her youth, which still dwelt upon her memory … associated with the common appellation of the Bank, the Fairies’ or Goblins’ Hill, and a very general idea that the place was haunted.

So there hadn’t been ‘frequent sightings’, plural, of a ‘glittering apparition’ of a ‘golden boy’: the Vicar of Mold never says if the old woman thought the figure was male or female, young or old. And she saw it only once. But no one can resist a ghost story, can they? And they get embroidered. If you google ‘Mold Gold Cape’ today you’ll come across references to ‘numerous past sightings’ of a ‘ghostly, giant warrior in golden armour’ who even used to ‘beckon travellers’ towards his burial place. However all that can be said for sure is that this spot, like many another in Wales, was named ‘Hill of the Elves’ before the finding, and was believed to be haunted. Since the vicar couldn’t turn up any other accounts of a golden ghost or a golden burial, bang goes the ‘information preserved in folklore’ theory, in this instance at least. If the old woman’s vision truly predated the finding of the cape, it was probably a coincidence.

It’s all very sad. If you’re anything like me, you’d love to believe at least SOME folktales preserve real folk memories. A percentage of them may, perhaps, but which ones and how could it be verified? The author Adam Nichols, in his recent book about Homer, ‘The Mighty Dead’ (read it, it’s wonderful) tells an interesting story. In 1953, just 8 years after the end of the War, an American-Greek professor of ethnography, James Notopoulos, travelled to the Cretan province of Sfakia. Everywhere he went, men were singing songs about the War, the cruelty of the Germans, the burning of villages, the heroism of the defenders. The professor recorded many of these songs.

One of the most daring acts of the war on Crete had been the successful kidnapping of Crete’s German commander, General Kreipe, by two British officers, Patrick Leigh Fermor and Billy Moss, who were embedded in the Cretan resistance. They impersonated German soldiers, intercepted the general’s car, killed the driver, held a knife to the general’s throat and drove him through 22 German checkpoints before abandoning the car and taking to the mountain paths, where they hid up in the day and travelled by night for the next 20 days while the Germans combed the area for them. Finally they bundled the General on to a British Navy launch and took him to Alexandria.

The professor was surprised he hadn’t yet heard any songs about this feat, and said as much to one of the local bards, a gifted young man called Andreas Kafkalas. Kafkalas agreed, and said he thought he could compose a song about it right now, ‘to fulfil the obligations of Cretan hospitality’. He began at once, using ‘the traditional Cretan fifteen syllable line’, and the professor recorded it. The story had changed almost beyond recognition.

In Kafkalas’ version, the two English officers are replaced by an unnamed English general who arrives in Crete and summons before him a local Sfakian hero, Lefteris Tambakis - who did exist, but who had no connection with this operation. The English general ‘draws himself up to his full height, weeps over the cruelties being done by the Germans to the people of “desolate Crete” and reads out the order to the Sfakian people that Kreipe be captured, dead or alive [all untrue – no such order existed].’ Next, Tambakis recruits a beautiful girl who sacrifices her ‘woman’s honour’ by seducing Kreipe (renamed “Kaiseri", which I assume means something like ‘the big boss’) who tells her all his plans. She passes these to Tambakis, who, riding a beautiful horse, intercepts the general’s car. ‘No horses were involved,’ Nicols tells us, ‘but they always are in old Cretan songs. The Cretan fighters strip the general naked [they didn’t] and he begs for mercy [he didn’t, but this is a motif that usually appears at these moments in Cretan poetry].’ Finally, after the journey over the mountains, a submarine takes the general away to Egypt. Hitler is in despair, and ‘Never before in the history of the world has such a deed been done.’

‘If this is what could happen to a modern story in nine years,’ Nichols asks, ‘how could anyone hope that anything true might survive in the Iliad of the Odyssey?’

Well, in this folk version of the story, at least the core event remains - the successful kidnapping by Resistance fighters of a German General in occupied Crete during the Second World War. None of the other details are true, and though the reason Kafkalas changed them may partly be due to the formulaic structure of traditional songs, it seems obvious the main reason must be that he wasn’t emotionally invested in a story about two English heroes. He has transformed this true and dramatic event – far too good to forget - into a Cretan patriotic epic. National pride demanded no less.

Pride trumps history.

The story that ‘Queen Elizabeth slept here’ means a lot to the man who owns the house; not much to anyone else. We are all most invested in what is closest to us, belongs to us. I grew up in Ilkley, Yorkshire, ‘knowing’ – and I don’t know who told me – that fairies were once seen splashing about in the well-preserved Roman Baths on Ilkley Moor, known as White Wells. The caretaker opened the door one morning and saw them ducking and splashing in the water, and when they saw him they rushed past him out of the door screaming like swallows.

I didn’t believe the story but I knew the place, and I think I was proud of the fact that such a striking tale belonged to my town. But such local folk tales are unimportant or unknown to people living ten miles away (who have their own). There’s always the chance they’ll be lost. A storyteller dies. A family moves away. New people arrive. And no one remembers any more.

And sometimes, stories die because a deliberate effort has been made to erase them. Here’s an example. My third book, Troll Blood, is the final volume of a fantasy trilogy set in the Viking Age, incorporating a lot of Scandinavian folklore about trolls and other supernatural creatures. In this last book, my young hero and heroine set sail in a Viking ship to cross the North Atlantic and arrive in America as described in the ‘Greenlanders’ Saga’ and which we now know from archeological evidence the Vikings actually did.

Because the book is a fantasy I wanted also to introduce, as players on the North American scene, creatures in some way parallel to the trolls with whom my Norse characters shared their world. A folk belief in trolls is part of one people’s way of apprehending the world which defines and differentiates them from another group, for example one which believes in nymphs. (Trolls are rougher-edged, with snow on their boots.) I wanted to use stories from Native American folklore because I felt that to leave out any reference to the belief systems of the people I was writing about would be to lose a dimension. In travelling to North America, my Norse characters would have to meet Native Americans, and it was important that the latter should have a voice. For reasons I won’t go into here I chose to investigate the folklore of the Mi’kmaq of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, whose ancestors at least could have encountered the Norse voyagers. (No one really knows.) I spent at least six months, probably more, going through ancient copies of the Journal of American Folklore in the Bodleian, tracking down primary sources wherever I could, especially stories taken down verbatim from named individuals. One of these was a story collected in the mid 1920s by the anthropologist Elsie Clews Parsons from a Mi’kmaw woman called Isabelle Googoo Morris.

THE HAMAJA’LU

These are very small beings, no larger than two finger joints. There are thousands of them who live along the shore. Water-worn, pitted stones are associated with them, “they have chewed in them, picked in them”. Once when some men landed on the shore for a short time, before they took to their boat again they saw a model of themselves and their boat made in stones by the hamaja’lu. They work very fast.

Elsie Clews Parsons, ‘Micmac Folklore’, p94, J. of A. F, V.38, 1925

I thought this was charming, and the hamaja’lu went into my story. When the book was finished I sent it to be vetted to Dr Ruth Holmes Whitehead, an expert in Mi’kmaq studies who kindly set me right on a number of important points. But I was rather dismayed when she asked me to correct ‘the hamaja’lu’ to ‘the wiklatmuj’ik’, a far more difficult word to read and pronounce. (My editor was certainly not going to like it!) So I asked her ‘Why? After all, the word ‘hamaja’lu’ is there, written down in a verbatim account.’ And she wrote back, ‘Because there is no ‘h’ in modern Mi’kmaq, and this word is obsolete. The word used today is the one I have given you.’ I wanted to be sensitive, yet felt I had to express surprise. How could it be that a word used so freely in the 1920’s – there were several stories about the ‘hamaja’lu’ – could have died out? Back came the reply: ‘You would not find it so surprising if you were aware that, during the course of the 20thcentury, generations of Mi’kmaq children were taken from their parents, put into homes, taught European ways, and punished – beaten, shut in cupboards, thrown down stairs – for speaking their own language.’

This sorry pattern of dominant Western culture imposing itself on the cultures of indigenous peoples has been repeated many times. Even though stories about the hamaja’lu were written down in the 1920s, they’re not told any more. (The wiklatmuj’ik aren’t really the same.) Such tales are more than curiosities. In many, many ways, folk tales make us. They define us as individuals, as families, clans and nations. Though the now-forgotten hamaja’lu may never have had objective reality, they were once part of a wider story, a belief system, part of the truth of Mi’kmaq identity. That was what the Canadian Government was trying to eradicate.

Lord Raglan was a real hard-liner about folk tales. He didn’t believe that any of them preserved any historical information at all. He defines history like this: History is the recital in chronological sequence of events which are known to have occurred. Insisting that history depends entirely on written chronology, he claimed that since (what he termed) ‘the savage’ cannot write, ‘…the savage can have no interest in history.’

I’ll let you gasp. He goes on,

Since interest in the past is induced solely by books, the savage can take no interest in the past; the events of the past are in fact completely lost.

Pause for another gasp. One more quote if you can stand it.

When we read of the Irish blacksmith who said that his smithy was much older than the local dolmen … or of the English rustic who said that the parish church (13thC) was very old indeed, it was there before he came into the parish, and that was over 40 years ago – we are apt to suppose the speaker exceptionally stupid or ignorant, but their attitude towards the past is similar to that of the Australian black who began a story with: ‘Long long ago, when my mother was a baby, the sun shone all day and all night’, and is the inevitable result of illiteracy. (my italics)

You know what? A man who poured scholarly scepticism on traditional tales about Queen Elizabeth, has no right to take these other tales at face value. He can’t have it both ways. Breaking his own rule, Raglan does not even source the first two anecdotes, which appear to be racist shaggy dog stories. In the third example, Raglan makes a category error. The Aboriginal storyteller is clearly opening a traditional story with the type of formulaic phrase found all over the world – a nonsense phrase which places it firmly in the land of long ago and far away. In other words, a fairytale.

‘Long long ago, when my mother was a baby, the sun shone all day and all night.’

Compare with this, from the Brothers Grimm:

Once upon a time, when wishing stll helped one, there was a king who had three daughters.

Or with this super-exuberant opening from Romania:

Once upon a time, long long ago (and if this story were not true, it would never have been told), when all the poplar trees were covered with pears, and the willows with nuts, when bears switched their tails like cows, when wolves and lambs loved each other like brothers, when fleas with ninety-nine pounds of iron on their backs hopped high in the sky and brought back wonderful stories, when flies wrote rhymes like this on the wall - ‘A tap on the nose for all who doze/Who doubts my lore shall hear no more’ – once upon a time, then, there was a powerful emperor who had three sons.

Or even this:

Long long ago, in a galaxy far, far away…

None of these are naïve. The Aboriginal storyteller and her audience know perfectly well there never was a time when the sun shone all day and night. That’s the whole point. The concept is deliberately, joyfully surreal. Far from from making any claim to be true, fairy tales openly delight in their unbelievability.

How does Raglan miss all this? Partly because his sense of privilege and superiority blinds him to the sophistication of illiterate narrators. And in my view he misunderstands folk narratives. What he really wants to do with folklore is to prove that ‘All traditional narratives originate in ritual’, which is a very 1930s thing to think. Take the widespread folk motif of ‘The Faithful Hound’. The best-known British version is about Gelert, favourite wolfhound of the Welsh prince Llewellyn. The only thing Llewellyn loves better than his dog is his own baby son. Coming home from hunting one day, he’s horrified when Gelert, whom he’d left guarding the child, bounds to greet him, jaws and muzzle covered in blood. He rushes into the castle hall to find the baby’s cradle overturned, the sheets bloodied, the child nowhere in sight. ‘Faithless hound,’ he cries. ‘You have murdered my son!’ and drawing his sword, strikes Gelert dead. Then he hears a baby chuckle, and behind the cradle finds the child tugging at the fur of a huge dead wolf – which Gelert has clearly fought and slain. In deep remorse, the prince buries Gelert and raises a stone in memory of his faithful friend.

Lord Raglan tries to convince the reader that this well-known tale-type preserves, as if in aspic, references to a type of ritual drama going back to the days of Abraham and Isaac when child sacrifice was replaced by animal substitutes. This is as much baseless conjecture as any ‘Queen Elizabeth Slept Here’ story.

Now, OK, this is a guy writing in 1936: do we need to listen to his outmoded theories about what is and what isn’t history? Well, I think it’s salutary, I think it can provoke thought, because here’s where he goes wrong. He thinks, and a lot of people still think, history is all facts and dates and dated events, and being able to prove conclusively that certain things happened and where they happened, and when. Of course that’s essential. But another view of history could be that it’s what goes on inside people’s heads. It’s what we remember and what we forget, it’s what we’ve been taught and what we’ve never had a chance to learn. And it’s shaped and driven by all sorts of inconvenient emotions such as pride and shame and patriotism and nationalism.

This is a book called ‘OUR ISLAND STORY, a History of England for Boys and Girls’, by H.E. Marshall, first published in 1904.

The opening chapter, ‘Albion and Brutus’, tells how Neptune and Amphitrite had a lovely little boy called Albion. They wanted to give him an island all of his own, so they sent the mermaids far and wide to find somewhere good enough, till at last one pretty little mermaid came back with news of an island ‘like a beautiful gem in the blue water’. So Albion ruled over this island for seven years, until he was killed in a fight with Hercules, and then Brutus arrived from Troy and fought and killed various giants who lived here, and finally, when Neptune retired as a god, because he had loved Albion so much he gave his sceptre to the islands now called Britannia – ‘For we know – Britannia rules the waves.’

Now that’s clearly a fairy tale, even if parts of it are based on Geoffrey of Monmouth’s 12th century History of the Kings of Britain, which itself, as you’ll know, is almost entirely fiction. The author, who was Australian, winds up the chapter like this, loading it with nostalgia for the imagined past.