Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 15

September 17, 2019

Tales of Kismet, Fate and Doom

Originally published as 'Inevitable Tales' in 'Unsettling Wonder' Issue 6, September 2017

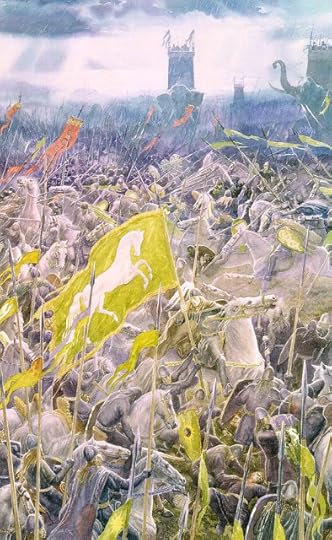

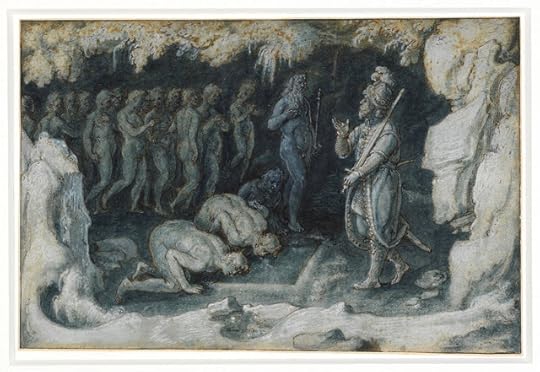

Nothing, they say, is sure but death and taxes. By creating a comic equivalence between two such different but universally unpopular processes, the maxim succinctly acknowledges the trials of life and the inevitability of death. It's a bleak lookout - and so there are many traditional stories in which the impotence of humanity in the face of what seems a hostile or indifferent world is mitigated by endowing the universe with purpose. Kismet – fate, destiny, quadr, karma, doom, wyrd – across the world these similar yet subtly different concepts have sprung up as responses to the same anxiety. They reassure that whatever good or evil may befall us is somehow meant to be, intended, written in the stars. Kismet is the opposite of luck. Luck is happenstance, the random fall of the dice. Kismet is destiny ordained by a higher power. In ‘The Lord of the Rings’ Gandalf tells Frodo it is so unlikely that the Ring would abandon Gollum only to be picked up by Bilbo from the Shire, that some mysterious purpose must be involved:‘Behind that there was something else at work, beyond any design of the Ring-maker. I can put in no plainer than by saying Bilbo was meant to have the Ring, and not by its maker. In which case you also were meant to have it. And that may be an encouraging thought.’Possession of the Ring is a calamity. When times are bad, it helps to hold on to the idea that there is meaning behind it all, but how, or whose? Answers vary according to the ways different cultures, philosophies and religions express their world-views. According to the Oxford English Dictionary the word ‘kismet’ is derived from the Arabic kisma(t), meaning ‘portion, division, lot’. From the outset then, kismet implies something received, not chosen: your allotted measure, your just deserts. One of the neatest tales of kismet is to be found in the Babylonian Talmud, c. 500 CE. In sukkah 53a, 7-16, Rabbi Johanen tells a story to illustrate the saying: A man’s feet are responsible for him; they lead him to the place where he is wanted. King Solomon had two Cushite scribes, Elihoreph and Ahyah. One day the King noticed that the Angel of Death was looking downcast. ‘Why are you so downcast?’ he asked. ‘Because the lives of your two scribes have been demanded of me,’ replied the Angel. In order to save the scribes, Solomon spirited them away to the district of Luz, where both men immediately died. On the following day the Angel of Death was in a cheerful mood, and again Solomon asked him why. ‘Because,’ said the Angel, ‘you sent your scribes to the very place where I was meant to slay them.’ The story shows that there is no escaping what God has ordained, for although he is not directly mentioned it cannot doubted that it is God’s demand which the Angel of Death is bound to fulfil. Other stories of kismet begin at a child’s birth and concern themselves with prophecies of his or her future. Despite or even because of efforts to prevent them, prophecies in stories always come true. In the Grimms’ fairy tale ‘The Devil With The Three Golden Hairs’ (KHM 29), a prophecy is made at the birth of a poor boy that he will grow up to marry the king’s daughter. Learning of this, the king persuades the parents to give him the child, promising to adopt him, but instead places him in a box and throws him into a river to drown.

The baby is rescued, however, and brought up by poor but kindly millers: when he is grown the king discovers him and tries again to have him killed by sending him to the queen with a sealed letter ordering his execution. On the way, robbers shelter the boy, examine the letter and alter it to command the boy’s immediate marriage to the princess. And so the king’s efforts to confound the prophecy actually bring it to pass. This kind of story is Aarne-Thompson Tale Type 930, ‘Prophecy’. Closely related to it is the tale of Oedipus (AT 931). Laius, King of Thebes, learns from the Delphic Oracle that his son will murder him. According to different versions of the myth, Laius either pierces his baby son’s feet and exposes him on Mount Cithaeron, or seals him in a chest and casts him into the sea. In either case the child is adopted by the queen of Corinth, who pretends to have given birth to him. Growing up ignorant of his parentage, Oedipus kills Laius in an altercation on the road and marries his mother Jocasta. Once again the prophecy is fulfilled through the king’s very efforts to avert it. Much of the fascination of tales of this kind comes from watching the machinery of destiny inexorably at work.

If prophecies predict the future, can they be said to cause it? The answer to that depends very much on context. The Delphic Oracle spoke for the god Apollo, but there is no sense that Apollo takes a personal interest in Oedipus’ misfortunes. For the God of the Old Testament the case is less clear. The story of Joseph in the Book of Genesis is thick with prophetic dreams: not just those of Joseph himself but of Pharoah too, and his baker and butler. Joseph famously dreams that while binding sheaves in the field, his sheaf of corn stands upright while those of his eleven brothers bow down to him; also that ‘the sun, the moon and the eleven stars’ bow down before him. And he told it to his father and to his brethren: and his father rebuked him and said unto him […] Shall I and thy mother and thy brethren indeed come to bow down ourselves to thee to the earth?’Genesis 37, 10To prevent the prophecy from coming true, Joseph’s brothers sell him as a slave into Egypt, a course of action which initiates his rise to power as Pharoah’s most trusted servant and governor of all the land; when famine strikes, Joseph’s brothers journey to Egypt in search of grain and do indeed bow down before him.

There seems no particular reason why any of the characters in the stories we have looked at so far should be singled out by fate. None are especially good or bad. We are told nothing about the characters of Elihoreph and Ahyah, we only see that their time has come. Oedipus did not want or intend to murder his father or marry his mother. For the young hero of ‘The Devil With The Three Golden Hairs’, it’s not so much that he deserves to succeed as that the wicked king deserves to fail, and the same is true of Joseph and his brothers. Joseph’s story is in style, and affect, a fairy tale. He reports his dreams, and correctly interprets those of others, but he is not required to act upon them. His father Jacob was touched by holiness: spoke to God, even wrestled with him – but Joseph has no one-on-one relationship with God, and his qualities remain those of a fairy tale hero: ordinary morals and a good work ethic. He does not earn his destiny, it is bestowed upon him, unfolding as a consequence of the actions of others and the mysterious will of God. A story which does require some action on the part of the dreamer is ‘The Pedlar of Swaffham’, an English tale first recorded in the 17th century. A pedlar of Swaffham in Norfolk dreams that if he travels to London and stands upon London Bridge, he will hear good news. At first he doubts the dream, but after its third repetition he puts it to the test. Arriving in London he stands day after day on the bridge, but nothing happens. Finally a curious shopkeeper asks the pedlar what he is doing, the pedlar explains his dream and the shopkeeper bursts out laughing.‘I’ll tell thee, country fellow, last night I dreamed I was in Swaffham, where me thought behind a pedlar’s house in a certain orchard and under a great oak tree, if I digged, I should find a vast treasure! Now think you,’ says he, ‘that I am such a fool as to take such a long journey on the instigation of a silly dream? No, no, I’m wiser.’Naturally the pedlar hurries home, digs a hole in his own orchard and finds the treasure. Significantly, while the pedlar dreams only of unspecified ‘good news’, the shopkeeper’s dream contains every detail needed to find the treasure. The pedlar however, trusts in and acts upon his dream, while the shopkeeper’s scepticism and failure to act deprives him of the treasure and brings the pedlar his reward. The town of Swaffham celebrates the story to this day:

The story certainly is not asking us to believe that God was concerned in enriching the Pedlar of Swaffham. (Unless, as I sometimes wonder, it began life as a sixteenth-century pulpit parable, with the good news turning out to be the Gospels and the treasure explained as salvation.) At any rate, in the form we have it the tale sends a more general and cautious message: ‘Trust, and all will be for the best’. But trust in what, or in whom? Need providence be a personal Providence? To put it another way, do we live in a moral universe? What about karma? Karma may be a bit of a sixties buzz-word, but its original Sanskrit meaning refers to a spiritual principle of cause and effect: the events of a person’s life, good or bad, are the consequence of his or her actions and intentions in previous lives and are therefore quite literally earned or deserved. In one of the Buddhist Jatakas a princess, Rujā, explains to her father King Angati why it is that in spite of appearances Alāta, a general, is in a worse moral state than Bījaka, a slave:I will tell thee a parable, O king. As the ship of merchants, heavy through taking in too large a cargo, sinks overladen into the sea, so a man, accumulating sin little by little, sinks overladen into hell … Formerly Alāta’s deeds were righteous, and it is as their result that he enjoys this prosperity. That merit of his is being spent, for he is all intent upon vice…As the balance properly hung in the weighing house causes the end to swing up when the weight is put in, so does a man cause his fate at last to rise if he gathers together every piece of merit little by little, like that slave Bījaka intent on merit.Jataka 544, tr. E.B. Cowell and W.H.D. Rouse, 1907So… is anyone in charge, or is this just how the universe works? It’s not entirely clear. The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad (7thcentury BCE), speaking of the self or soul, explains: ‘As is its desire, so is its resolution; and as is its resolution, so is its deed; and whatever deed it does, that it reaps.’ What goes around comes around: the idea that karma means reaping what you sow has proved attractive to Western audiences accustomed by Christianity to ideas of judgement, reward and retribution. Less easy to grasp is the tranquil assertion that follows these lines: in order to escape the world and be united with the non-personal ultimate reality, Brahman, the self must be free from all desires, good or bad. Brahman is a difficult metaphysical concept. It must be distinguished from the Hindu creator god Brahma, who – scholars suggest – may have emerged from it at a later date, a personification people found easier to engage with, and more comprehensible. In a story collected by G. R. Subramiah Pantalu in ‘Folk-Lore of the Telegus’ (1905) not only is karma inevitable, but Brahma seems to control it. The god Siva and his wife Parvati see a poverty-stricken Brahmin priest making his way home. Parvati wishes to gift him with gold, but Siva tells her that Brahma has not written that the Brahmin should enjoy wealth in this life. To test this, Parvati throws a thousand gold coins on the path, but as the Brahmin approaches he finds himself suddenly wondering whether he could walk along like a blind man. So, closing his eyes, he passes the coins and never sees them… Perhaps it’s always easier for people to believe in a directed, personal fate than an impersonal one. For in this unfair and difficult world of ours, don’t we yearn for good deeds to be rewarded, evil deeds to be discovered and punished? ‘The Cranes of Ibycus’, a story found in the 10th century Byzantine Encyclopaedia, tells of the murder of Ibycus, a Greek poet:

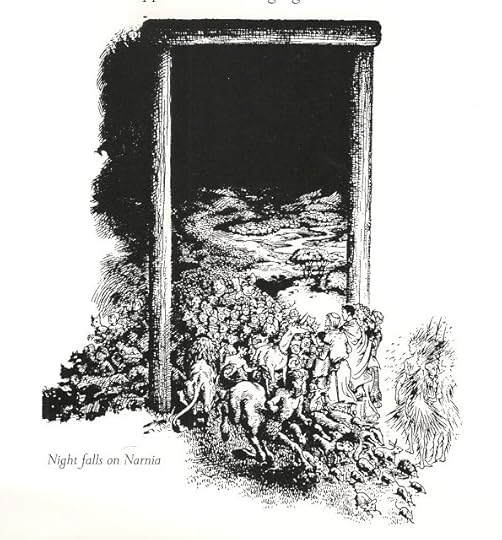

Captured by bandits in a deserted place he declared that the cranes which happened to be flying overhead would be his avengers; he was murdered, but afterwards one of the bandits saw some cranes in the city and exclaimed, ‘Look, the avengers of Ibycus!’ Someone overheard and followed up his words: the crime was confessed and the bandits paid the penalty; whence the proverbial expression ‘the cranes of Ibycus’. Trans. David CampbellIn this story there is no supernatural intervention: the birds do not speak and their flight over the city might be providence or coincidence, but here – at least in the sense the West understands it – we find karma’s cause and effect at work in the space of a single life-time. The satisfactory neatness of the murderer revealed by his own involuntary exclamation might belong to a modern detective story – a genre which itself relies on and reinforces our yearning for justice and right to prevail. Precisely because fairy tales are not meant to be realistic, they can satisfy that yearning for justice. In the make-belief world of fairy tales everyone gets what they deserve. Many are the stories in which a simple youngest brother or orphaned maiden shows pity to some animal, injured or trapped, or shares a last crust with some poor old woman. In ‘The White Snake’ (KHM 17) a kind-hearted prince who understands the speech of animals returns three stranded fish to the water, avoids trampling on an ant-hill, and feeds some starving ravens (by killing his horse, which may seem rather to undo the good deed, but in this tale the horse must be regarded as an extension of himself). In gratitude, the animals help him in a number of difficult tasks. Generous acts in fairy tales are almost always rewarded. In the Grimms’ tale ‘Mother Holle’ (KHM 24) the pretty, hardworking girl who jumps down the well into Mother Holle’s otherworldly land behaves with courtesy and kindness even to the inanimate objects which plead for her help. She takes bread out of an oven so that it won’t burn, and shakes down apples from an apple tree so the branches won’t break, and she works so diligently and well for old Mother Holle that her reward is a shower of gold which covers her from head to foot. Karma brings like for like, however. The lazy, ugly stepsister who ignores the pleas of the oven and the apple tree and refuses to work for Mother Holle is showered with pitch, not gold. In fairy tales truth always comes to light and evil deeds are discovered and punished. ‘The Singing Bone’ (KHM 28) tells how two brothers go out to find and kill a dangerous boar. The younger boy, whose heart is ‘pure and good’, kills the boar, but his jealous elder brother murders him. Burying the body under a bridge, he takes the credit for killing the boar and marries the King’s daughter.‘But as nothing remains hidden from God, so this black deed also came to light. Years afterwards, a shepherd was driving his flock over the bridge and saw lying in the sand beneath, a snow-white little bone...’The shepherd makes the bone into a mouthpiece for his horn, and when he blows on it the bone begins to sing and denounce the brother for his murder. The rest of the skeleton is found and the guilty man is put to death, while ‘the bones of the murdered man were laid to rest in a beautiful tomb in the churchyard.’

In fairy tales, helping a dead man is the most unselfish of acts, for surely the dead can never repay you? Hans Christian Andersen’s story ‘The Travelling Companion’ tells of young Johannes who gives away all his money to prevent evildoers from abusing the corpse of a man who was in debt to them. Shortly afterwards he is joined on the road by the ‘travelling companion’ of the title who befriends and guides him, and helps him to marry a princess whose luckless suitors must answer three riddles or die. Reading the tale as a child I was thrilled when the wicked princess flies out of the castle on black wings to visit her lover, a troll king… During the course of the story the travelling companion teaches Johannes how to answer the riddles, and succeeds in killing the troll and disenchanting the princess. When Johannes thanks him and begs him to stay with them for ever, he replies:‘No, I must go. I have but paid my debt. Do you remember the dead man whom you protected from wicked men in the church? You gave all you had so he might rest in his grave. I am that dead man.’ And with that he vanished.A similar tale is ‘Beauty of the World’, told to William Larminie by Patrick Minahan of Mainmore, County Donegal and reproduced in ‘West Irish Folktales’ (1893). A king’s son gives all the money in his purse so that a body can be buried, and soon after is joined by a red-haired man who helps in his quest to find the beautiful woman on whom his heart is set. After many adventures the woman is won and the ‘red man’ declares:It was I that was in the coffin that day. When I saw you starting on your journey I went to you to save you … Health be with you and blessing. You will set eyes on me no more.Stories of the Grateful Dead (AT 506) have antecedents going back as far as the apocryphal Book of Tobit. They proclaim that good actions will always be rewarded, sometimes by God, sometimes by the less explicit workings of a mysterious yet morally weighted universe. As people have thought about fate or destiny, different metaphors have emerged. Your deeds may be weighed in scales to determine your fate in the next life. Or destiny may be something measured out to you like grain: your portion or lot in life. In the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew, 7:2), Jesus combines measurement and judgement with the words, ‘with what judgement ye judge, ye shall be judged, and with what measure ye mete, it shall be measured to you again.’ He speaks also of ‘the reaper drawing his pay and gathering a crop for eternal life’ (John 4, 36). Like ‘kismet’, it seems the Arabic term al-quadr, ‘divine fore-ordainment’ or ‘predestination’ is also derived from a root which means ‘to measure out’. Implicit in these metaphors is an imagery of field-workers or servants judged worthy or not worthy of their hire. In a patriarchal society the one who decides on and doles out the wages is perceived as the ultimate Master, and so this metaphor mirrors the unequal relationship between the human and the divine.But there’s another equally ancient metaphor for fate and it comes not from field-work, but from house-work. It compares the course of a human life to a thread which is first spun, and then woven into cloth, and ultimately cut with shears. Weaving was a woman’s work, and the Weavers of destiny were women.

The Greek Moirae or ‘Apportioners’ were envisaged as three old women, Clotho, ‘the spinner’, Lachesis, ‘the measurer’, and Atropos, ‘she who cannot be turned’. Clotho spun the thread of a person’s life on her distaff, Lachesis measured it with her rod, and Atropos cut it with her shears. In her book on the prehistory of weaving, ‘Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years’ (1994) Elizabeth Wayland Barber points out a stock couplet that appears ‘almost verbatim’ twice in the Iliad and once in the Odyssey and which is probably older than either:He shall endure all that his destiny and the heavy SpinnersSpun for him with the thread at his birth, when his mother bore him.Odyssey Book 7, 197-98; Iliad Book 20, 127-28 & Book 24, 210, tr. R. LattimoreAn imagery of spinning and weaving produces a different effect from one of harvest, wages and worth. Judgment and payment are performed at the end of a task, but spinning and weaving are tasks: dynamic, creative, ongoing processes. Yes, the weaver holds the pattern of the cloth in her mind, but she is free at any point to change it and do something different. Moreover, there is no place in the weaving metaphor for blame or judgment. The woven pattern is what it is: it is simply ‘what happens’. It cannot easily be made to represent reward or punishment.

In Norse mythology the Norns are three maidens who sit under Yggdrasil the World Tree, and ‘shape the lives of men’. Their names are Urðr (‘that which has come to pass’), Verðandi (‘that which is happening’) and Skuld (‘that which is owed’). The Poetic Edda tells of them setting up a huge loom, with threads that stretch across the sky, to weave the destiny of a prince. In her book ‘Roles of the Northern Goddess’ (1998) Hilda Ellis Davidson provides a translation: It was night in the dwelling. The Norns came, those who shaped the life of the prince. They foretold him to be the most famed of warriors, who would be reckoned the best of rulers.They twisted firmly the threads of fate…Set in place the strands of gold,held fast in the midst of the hall of the moon.East and west they hid the ends…while Neri’s kinswoman knotted a cordfast to the north, and forbade it to break.The northern valkyries too, the ‘choosers of the slain’, were known as weavers of destiny. ‘The Saga of Burnt Njal’ tells of a man of Caithness named Dorrud, who on Good Friday saw twelve valkyries working on a warp-weighted loom, using severed heads for the weights and intestines for the thread. As they wound the finished cloth on to the loom beam, the women chanted a battle poem called ‘The Song of the Spear’ including the lines ‘Valkyries decide/who lives or dies.’ They then pulled down their cloth, tore it in pieces and each holding a piece in her hand climbed on their horses and rode off – presumably to war.When in Old English poetry we meet the concept of ‘wyrd’ – ‘fate’ – there is often an interesting tension between it and the idea of a Christian Providence. Though the Old English poem Beowulf is likely the product of an 8th century Christian court, it harks back to the heroic and pagan past, and much of its material probably existed in earlier oral forms. Wyrd oft nereð/Unfaégne eorl ƿonne his ellen déah.Fate often spares a man not fated to die, when his courage is strong.Beowulf, 572-3 The modern English translation of this line appears to produce a tautology. Two different terms are translated as ‘fate’. ‘Unfaégne’ means ‘not fated to die’. But if a man isn’t fated to die, why is the state of his courage even relevant? ‘Wyrd’ is not the same as ‘unfaégne’ however. Wyrd is the Old English cognate of the Norse Urðr, the first of the Norns: not an abstraction but a personification who might choose to spare a man. (Shakepeare’s Weird Sisters are ‘wyrd’ not because they are strange, but because they can show Macbeth his future.) I sense that for the Beowulf poet, destiny was not unalterably written in the stars, but something much more like a real-time decision that Wyrd might make. The Norns do not foretell destiny, they weave it, so a display of courage might influence them to change the pattern… In the same poem, Hrothgar complains of the misery that the monster Grendel has inflicted on him and his war-band: Is min fletwerod/wighéap gewaned; hie wyrd forsweop/on Grendles gryre. God éaƿe maeg/ƿone dolsceaðan daéda/getwaefan.[My hall-companions fail me, my war-band wanes; fate has swept them into Grendel’s grip. God may easily put an end to the deeds of this deadly foe.]Here, wyrd – again translated as fate – is used by Hrothgar to describe things that have already happened, not things yet to come. His dead warriors were doomed to die: whatever has happened in the past was clearly ‘meant to be’: yet God if he wishes can easily alter the course of future events. And in contrast to kismet and karma, there isn’t any sense that Hrothgar’s warriors deserve their fate. Wyrd is ‘what happens’; it is not transactional, not linked to personal morals. ‘Cattle die, kinsmen die,’ says Odin in the poem Hávamál in the Poetic Edda: Every man is mortal,But the good name never diesOf one who has done well. Tr. Paul Taylor and W.H. AudenIn the Norse world you had better behave well, because good behaviour wins you fame – but in the end nothing can ward off wyrd. Wyrd/Urðr arises from a world-view that believed even the gods would eventually perish at the hands (or teeth) of monsters on the day of Ragnarok.

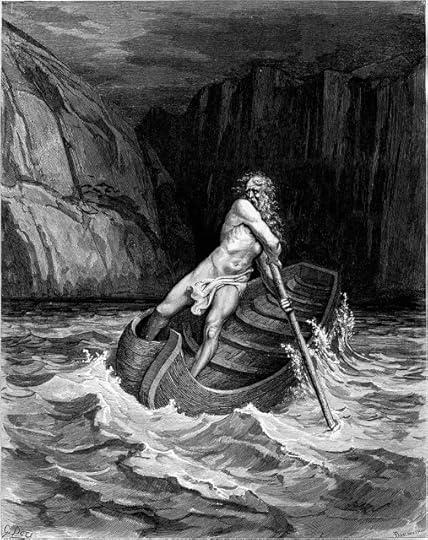

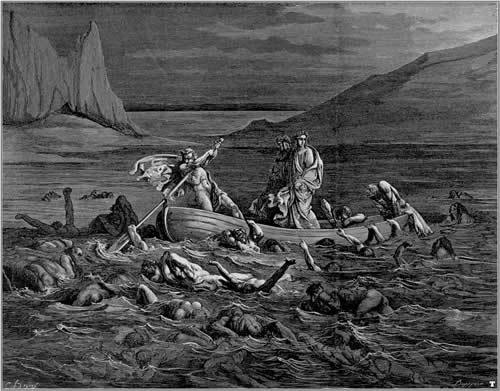

Finally: that word doom. We now think of doom as a terrible fate lying in wait for us, but the word was originally without its modern connotations of disaster. It is derived from Old Norse dómr, a law or sentence. A kingdom is a land subject to the doom or law of a king. God, however, is Lord and King of all Christendom, and as Christianity spread to the Anglo-Saxons, the day of final judgement became known in England as ‘Domesday’ or the Day of Doom. For those whose Last Day was to have been Ragnarok, I can see the attraction of one in which God’s wrath would be softened by mercy towards repentant sinners. In this new context wyrd became archaic and finally obsolete, its meaning swallowed by Biblical concepts of measurement and justice. It seems to me that concepts of kismet and karma, destiny and fate, have been driven by two things. One is a desire to make narrative sense of our time in the world and reconcile ourselves to inevitable death. If the Fates or Moirae or Norns spin the web of our lives, we know there must be a pattern even if we can’t see it. And stories such as the Rabbi Johanen’s parable, with which I began, make the point that since Death is bound to come, there’s no sense worrying about when: moreover, as the personified servant of God, endowed with human emotions such as sadness and cheerfulness, he loses some of his terror. The other driver is a very human desire for fairness and justice in a demonstrably unfair world. Fairy tales provide us with make-belief utopias in which the innocent and generous are rewarded and the wicked punished. In an exactly balanced moral universe, karma delivers perfectly measured consequences for all our actions – if not in this life, at least in our next incarnation. Meanwhile, in a harsh northern world, wyrd urges sturdy acceptance of life’s hardships. I will leave you with a short story by Somerset Maugham which has resonances of Rabbi Johanen’s parable with which I began. ‘The Appointment in Samarra’ comes at the end of Maugham’s 1933 play ‘Sheppey’. It epitomises the blend of humour, grace and resignation with which Tales of Kismet approach our mortality. The eponymous Sheppey is a kind-hearted barber who wins the Irish Lottery and gives all his money away over the course of the three acts. In the final scene a woman enters who looks like Bessie Legros, a prostitute whom he has helped, but really she is Death. She and Sheppey have a long conversation. Towards the end Sheppey asks, ‘You ain’t come here on my account?’. ‘Yes,’ says Death. ‘You’re joking,’ says Sheppey. ‘I thought you’d just come here to ‘ave a little chat … I wish now I’d gone down to the Isle of Sheppey when the doctor advised it. You wouldn’t ‘ave thought of looking for me there.’ And Death replies:There was a merchant in Baghdad who sent his servant to market to buy provisions, and in a little while the servant came back, white and trembling, and said, ‘Master, just now when I was in the market-place I was jostled by a woman in the crowd, and when I turned I saw it was Death who jostled me. She looked at me and made a threatening gesture. Lend me your horse, and I will ride away from this city and avoid my fate. I will go to Samarra, and there Death will not find me.’ The merchant lent him his horse, and the servant mounted it, and he dug his spurs in its flanks and as fast as the horse could gallop he went. Then the merchant went down into the market-place and he saw me standing in the crowd and he came to me and said, ‘Why did you make a threatening gesture to my servant when you saw him this morning?’ ‘That was not a threatening gesture,’ I said, ‘it was only a start of surprise. I was astonished to see him in Bagdad, for I had an appointment with him tonight in Samarra.’

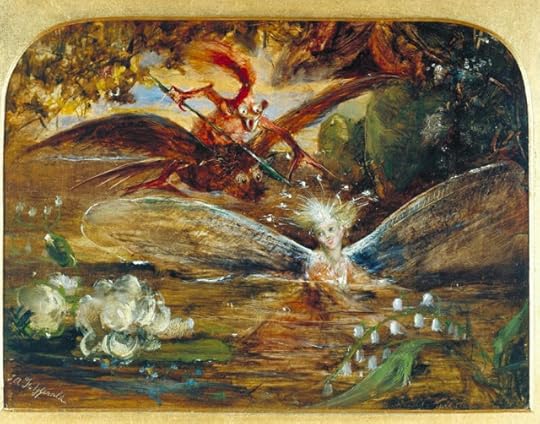

Picture credits:

The Angel of Death by Evelyn de Morgan, 1881, wikipedia Moses in his basket [the Child Cast Adrift] by Charles Foste: public domain, via blog Under the InfluenceThe Murder of Laius by Oedipus by Joseph Blanc wikipediaJoseph Recognised by his Brothers by Léon Pierre Urbain Bourgeois wikipedia Pedlar of Swaffham Town Sign wikipedia The Cranes of Ibycus by Heinrich Schwemminger wikimedia commons The Princess Flies on Black Wings by Anne Anderson, The Mammoth Book of Wonders, author's possessionA Golden Thread [The Moirae] by John Melhuish Strudwick, wikipedia

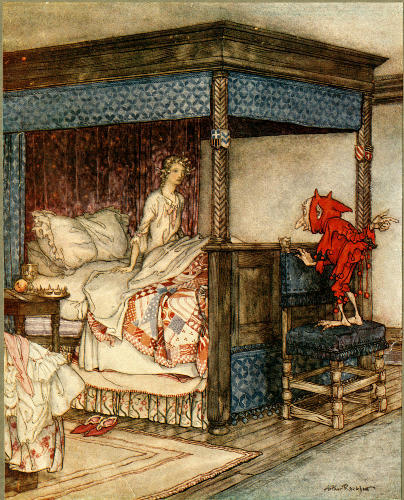

The Norns by Arthur Rackham wikipedia

Odin and Fenriswolf, Freyr and Surt by Emil Doepler, 1905 wikipedia

Published on September 17, 2019 02:38

June 18, 2019

Maid Maleen: a fairytale study of trauma?

This essay was originally published nearly two years ago in the 12th issue of Gramarye, Winter 2017

(It will take you a while to read!

(It will take you a while to read!

Published on June 18, 2019 05:27

May 17, 2019

Sisters with Swords

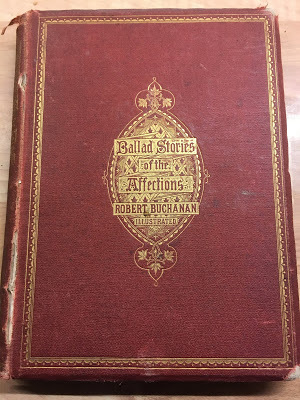

I have a very old book of Scandinavian ballads, ‘Ballad Stories of the Affections’, edited and translated by Robert Buchanan. There’s no date of publication, but in Christmas 1887 (or 1881?) the book’s first owner, one GA Williams of ‘Spring Villa, Hanwell’, wrote his name and the date on the inside cover. I rather like the blue and gold book plate, too - although as it seems to say 'IG - his book', it may have been pasted in by a subsequent owner.

The ballads ‘emanate’, as Buchanan says in his introduction, ‘from the storm-tost shores of Denmark and the wild realm of the eternal snow and midnight sun … where the Ocean Sprite flashes, icy-bearded, through the rack and cloud of the storm.

‘Nothing can be finer’ (he goes on) ‘than the stories they contain, or more dramatic than the situations these stories entail; but no attempt is made to polish the expression or refine the imagery. They give one an impression of intense earnestness… That the teller believes heart and soul in the tale he is going to tell, is again and again proved by his dashing at once into the catastrophe –

‘It was the young Herr Haagen,He lost his sweet young life!’

And all because he would not listen to the warnings of a mermaid, but deliberately cut her head off.’

Hagen is a character from the Nibelungenlied (and indeed fromWagner's Ring cycle). In the former, he steals the clothes of three nixies or waterspirits as they bathe in the Danube, but his cutting off a water-maid's head must be a later piece of folklore and – annoyingly – Buchanan does not include it here. However, I thought you would enjoy reading some of these ballads and I’ll be choosing a few to show you. They all have refrains, which if the ballads were sung would probably be repeated in every verse: you can imagine how the repetition multiplies the fatalism, the sense of gathering doom.

Here then is ‘The Two Sisters’. It tells how the daughters of a wronged knight take revenge on his murderer – whose thick-skinned bonhomie and sense of entitlement somehow reminds me of Boris Johnson, I can't think why.

Through the 19th century diction you can see quite well what Robert Buchanan means about ‘intense earnestness’. He adds that ‘the adventurous nature burns fierce as fire and the heroes sweep hither and thither, bright as the sword-flash.’ I’ll go with that.

At the foot of the ballad you'll find an illustration of the young women arming themselves and cutting off their hair. Éowyn and these two shieldmaidens share a similar heritage!

THE TWO SISTERS

One sister to the other spake,The summer comes, the summer goes!‘Wilt thou, my sister, a husband take?’On the grave of my father the green grass grows!

‘Man shall never marry meTill our father’s death avenged be.’

‘How may such revenge be planned? – We are maids, and have neither mail nor brand.’

‘Rich farmers dwell along the dale;They will lend us brands and shirts of mail.’

They doff their garb from head to heel;Their white skins slip into skins of steel.

Slim and tall, with downcast eyes,They blush as they fasten swords to their thighs.

Their armour in the sunshine glaresAs forth they ride on jet-black mares.

They ride unto the castle great;Dame Erland stands at the castle gate.

‘Hail, Dame Erland!’ the sisters say;‘And is Herr Erland within today?’

‘Herr Erland is within indeed;With his guest he drinks the wine and mead.’

The maidens in the chamber stand;Herr Erland rises with cup in hand.

Herr Erland slaps the cushions blue,‘Rest ye, and welcome, ye strangers two!’

‘We have ridden many a mile,We are weary and would rest a while.’

‘Oh tell me, have ye wives at home?Or are ye gallants that roving roam?’

‘Nor wives nor bairns have we at home,But we are gallants that roving roam.’

‘Then, by our Lady, ye shall tryTwo bonnie maidens that dwell hard by –

‘Two maidens with neither mother nor sireBut bosoms of down and eyes of fire.’

Paler, paler the maidens turn;Their cheeks grow white, but their black eyes burn.

‘If they indeed so beauteous be,Why have they not been ta’en by thee?’

Herr Erland shrugged his shoulders upLaughed, and drank of a brimming cup.

‘Now, by our Lady, they were wonWere it not for a deed already done;

‘I sought their mother to lure away,And afterwards did their father slay!’

Then up they leap, those maidens fair;Their swords are whistling in the air.

‘This for tempting our mother dear!’Their red swords whirl, and he shrieks in fear.

‘This for the death of our father brave!’Their red swords smoke with the blood of the knave.

They have hacked him into pieces, smallAs the yellow leaves that in autumn fall.

Then stalk they forth, and forth they fare;They ride to a kirk and kneel in prayer.

Fridays three they in penance pray; The summer comes, the summer goes!They are shriven, and cast their swords away. On the grave of my father the green grass grows!

Published on May 17, 2019 01:06

March 12, 2019

Haunted by Heads

On a brief trip to visit friends and relations in Yorkshire and Manchester last October, I began encountering an unsettling number of severed heads.

Not real ones of course. Stone heads, with an archaic, Celtic vibe. The one pictured above I've known for years, set in a wall beside my friend's house in Malhamdale. It had been found in the ruins of a chapel somewhere up on the tops and her uncle, a builder, salvaged it and built it into the wall as – well, what? Decoration? For luck? To watch over those who pass by? Perhaps all of those things? Visiting my friend again, I wondered as I’d done before, how old it might be. Medieval at least, surely - but might it be older?

On the same day, heading out of the Dales for Manchester, we stopped to look into the church of St Michael the Archangel at nearby Kirkby Malham. I regard this as my church, the one whose walls I helped whitewash back in the 70’s, the one I was married in, the one where we held my father’s funeral. And looking up I noticed as if for the first time (though I must surely have seen them before) two more archaic or Celtic-looking stone heads placed between the arches. What?!

The church dates back to the 12th century but it was rebuilt in about 1490. The stone heads are described as ‘Celtic’ in various accounts of the church, and they certainly look very old with their slit-like mouths, wedge-shaped noses, lentoid eyes and blank, grim expressions. But you can’t carbon-date stone, so there’s no way to know. Placed where they are, however, they must be at least as old as the 1490 reconstruction of the church. I took some photos... and that evening in Manchester, we went for a drink at the Church Inn, Prestwich, which is a characterful 17th century building set on a quiet street next door to the 17th century church of St. Mary the Virgin. Finding a seat at a quiet table I glanced casually down to my right, to see lying on its side near the fireplace yet another stone head!

I was beginning to feel haunted. Three lots of stone heads in a single day? And this one so up close and personal?

As far as I've been able to discover, most genuine Celtic stone heads are carved in the round, whereas this one, as the Malham ones must be, is carved on the end of a block of masonry that could be keyed into a wall. We asked in the bar where the head had come from and were told it had been found during an archeological dig in the beer garden adjoining the churchyard (which dates to the 12th century), and that other bits and pieces from the dig could be found in the garden. I went to look, and found a couple of medieval gargoyles and other carved stones, but nothing else that looked nearly as old and strange as this simple stone head.

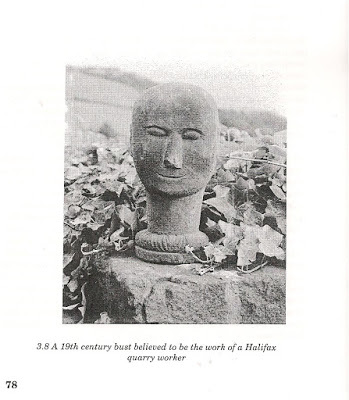

Back home I consulted a book: ‘Investigating Celtic and other Stone Heads’ (Capell Bann 1998) by John Billingsley of Bradford University. Billingley had become intrigued by the very large number of archaic-style stone heads scattered about the north and north-west of England - a survey by the Manchester Museum had clocked up over a thousand. They were found on buildings, built into drystone walls, even used as garden ornaments, but few could be safely dated. As he investigated, Billingsley unearthed evidence for what seemed to be an on-going tradition of carving archaic-style heads in stone. Some heads might, indeed, be ancient, but the majority were medieval or post-medieval; several turned out to be modern. For example, the photo below, from Billingsley's book, shows a 19th century stone head 'believed to be the work of a Halifax quarry worker'.

And, as is well known, the stone face at the Wizard’s Well on Alderley Edge in Cheshire was carved by Alan Garner’s stonemason great-great-grandfather Robert, with the inscription: DRINK OF THIS AND TAKE THY FILL FOR THE WATER FALLS BY THE WIZHARDS WILL.

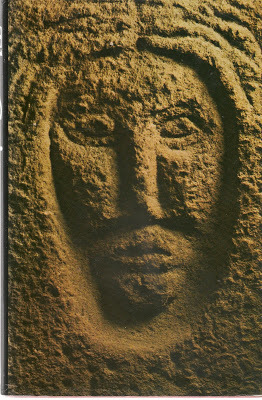

Alan Garner’s 1975 book of trickster tales, ‘The Guizer’, displays a full cover photograph of a stone face on both front and back of the jacket, positive on the front, negative on the back. It's attributed on the inner flap as "Celtic stone head, circa 1st century AD’, copyright Alan Garner." There's nothing about where this head is to be found though, and considering it’s on the cover of a book about tricksters, I have to wonder…

Reflecting on the endurance of the archaic tradition down the centuries, Billingsley points out that although the archaic head may appear crude, it possesses a ‘silent depth’ which more sophisticated, naturalistic representations lack:

The value of a symbol is that it conveys a complex of meaning from only a minumum of information. The rudimentary and skull-like features of the archaic head – eyes, mouth, nose – relate to human faces everywhere, whether living or dead. On the other hand, classical faces narrow the range of affinity to the point where portraiture disqualifies any claim to universality and anchors the image in one time and one space. The remote yet recognisable features of the archaic head thus become the natural vehicle for a symbol relating to both human and otherworldly beings, and this is the role in which stylised faces such as the archaic head are constantly encountered.

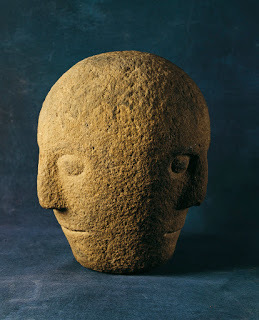

Celtic stone head in the Craven Museum, Skipton

Celtic stone head in the Craven Museum, SkiptonIn her book ‘The Celtic Myths’ (Thames and Hudson 2015) Miranda Aldhouse-Green writes:

The theme of supernatural disembodied human heads may have its roots in prehistoric ritual and belief. People in Iron Age Ireland, Britain and Europe appear to have accorded the human head special reverence. Archeological evidence provides clues as to how such veneration was expressed: by carving images of heads in stone and wood; by including head-symbols on decorated Iron Age metalwork and by repeatedly depositing real human heads in special places: wells, rivers, pits and temples.

Regarding the three-faced Corleck Head from Co. Cavan, Ireland (4th-1st century BCE), Green suggests that:

The dual symbolism of the head itself and its triple face contributed to an Iron Age cosmological code in which sacred power was both expressed and enabled by this highly charged object. It might depict a deity but it might equally have been used almost like one of Tolkien’s palantirior ‘seeing stones’ (used to gain knowledge of places or events far away in time or space), giving immense predictive magical potency to … those who could read it and interpret its messages.

I like that idea, for the three faces see in all directions at once, just as the two-faced ‘Janus’ of Roman tradition, who gives his name to January, stares backwards into the old year and forwards into the yet-unknown new one. In legend and folklore, severed or disembodied heads are important magical objects which can speak and deliver wisdom and counsel. In the Second Branch of the Mabiogion the hero Brân, stabbed in the foot with a poisoned spear, tells his men to cut his head off.

‘And take the head,’ he said, ‘and carry it to the White Mount in London, and bury it with its face towards France. And you will be a long time on the road. In Harlech you will be feasting seven years, and the birds of Rhiannon singing to you. And the head will be as pleasant company to you as ever it was when it was on me.’

The burial of Brân’s head was one of the Three Happy Concealments, and its disinterment (by King Arthur) one of the Three Unhappy Disclosures, for while it remained under the White Mount it protected the Island of Britain from evil.

There are many other talking heads: medieval literature is full of references to magicians and alchemists, like Roger Bacon, who construct oracular heads of brass or bronze which will answer questions - though usually only with ‘yes’ or ‘no’. In the 14th century poem the eponymous Green Knight picks up his head after it has been struck off by Sir Gawain, and challenges his adversary to a return match at the ‘Green Chapel’ in a year’s time. On his winter journey to keep the appointment Gawain rides through North Wales, turns up the coast with the island of Anglesey to his left, ‘fares over the fords’ by ‘Holy Head’, and passes into the ‘wild Wirral’. This is so specific that Holy Head has been identified as modern Holywell, site of St. Winifride’s Well. Winifride was a 7th century Welsh princess whose head was struck off by a prince, Caradog, whom she refused to marry. It rolled downhill and a spring of healing water burst from the ground where it halted. St Bueno restored Winifride’s head to her body and she became a nun - while the wicked suitor fell down dead. The site of this miracle is one of the oldest shrines in Wales, so Gawain might well have taken it for an encouraging sign that he should pass this scene of beheading and restoration on the way to his own encounter.

One-eyed Odin

One-eyed OdinHeads are often associated with springwater and wells. In Norse mythology the giant Mimir is guardian of the spring (or well) of wisdom that rises from under the roots of the World Tree, and every day he drinks from its waters. Odin once asked Mimir for a drink, but had to sacrifice an eye in payment. (Has this any significance for the few stone heads which have one eye closed as if blind?) In other tales Mimir is killed by the Vanir who cut off his head, but it is preserved at the well and Odin visits it there to ask for counsel.

Stone head with blind (pupil-less) right eye

Stone head with blind (pupil-less) right eyeIn Christian legends like Winifride’s, the severed head is rejoined to the body and does not remain in the well, but the holy spring which emerges at the place of martyrdom retains miraculous properties. In some tales that may channel older traditions, disembodied heads actually inhabit wells. A Scottish story from Fife, ‘The Wal at the Warld’s End’ (a very old tale, namechecked in the 1548 ‘Complaynt of Scotland’ though misspelt as ‘The Wolf of the Warldis End’) tells how a king’s daughter is sent by her stepmother to fetch a bottle of water from, yes, the well at the world’s end. The girl goes on and on till she comes to a tethered pony which asks her to ‘flit’ him (set him loose) for he’s been tethered seven years and a day. ‘Ay, I will, my bonnie pownie, I’ll flit ye.’ So the pony gives her a ride over ‘a moor of hecklepins’. (I thought ‘hecklepins’ might be something like the ‘seven miles of steel thistles’ which gave me the name for this blog. In that West Irish tale, otherwise not much like this one, a magical talking pony leaps over the steel thistles with the hero on his back. Hecklepins turn out to be not thistles but sharp steel pins up to nine inches long, packed together like a bed of nails, used for teasing out the fibres of flax or wool. So even nastier!)

Arriving at the well at the world’s end, the girl finds it too deep to dip her bottle in, but as she wonders what to do, she sees ‘three scaud men’s heads’ looking up at her. (‘Scaud’ means scalded or burned; it may mean the heads are bald and blackened.) The heads say together, ‘Wash me, wash me, my bonnie May/And dry me with your clean linen apron.’ When the girl obliges, they fill her bottle with water and give her three gifts: to be ten times bonnier than before, for jewels to fall from her mouth every time she speaks, and for her to be able to comb gold and silver out of her hair. (Her rude and careless stepsister of course fares badly.) Similar requests and rewards (even to the association of combing gold from hair) are found in George Peele’s 1597 play ‘The Old Wives’ Tale’, when two heads rise from a well to the accompaniment of voices singing:

Gently dip but not too deepFor fear you make the golden beard to weep,Fair maid, white and red,Stroke me smooth and comb my headAnd thou shalt have some cockle bread.

Gently dip but not too deep For fear you make the golden beard to weep,Fair maid, white and red,Comb me smooth and stroke my headAnd every hair a sheaf shall be,And every sheaf a golden tree.

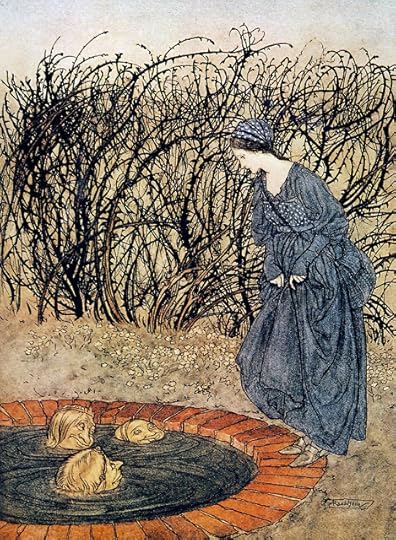

The Three Heads in the Well In the English fairytale ‘The Three Heads of the Well’ an old man advises a princess how to get through a thicket of thorns. Hidden beyond it is a well. ‘Sit down on the brink, and there will come up three golden heads, which will speak, and whatever they require, that do.’ The heads sing:

The Three Heads in the Well In the English fairytale ‘The Three Heads of the Well’ an old man advises a princess how to get through a thicket of thorns. Hidden beyond it is a well. ‘Sit down on the brink, and there will come up three golden heads, which will speak, and whatever they require, that do.’ The heads sing:Wash me and comb meAnd lay me down softlyAnd lay me on a bank to dryThat I may look prettyWhen somebody passes by.

In all these stories the heads want attention, they want to be combed and made to look presentable, they want to be shown the sort of honour due to the dead, to the severed head of a hero.

In the Grimms’ tale ‘Mother Holle’ although there are no floating heads, a girl throws herself into a well and finds Mother’s Holle’s magical otherworld at the bottom. Mother Holle was originally the goddess Holde: Jacob Grimm suggests she was a sky deity associated with the weather, who could at times like Wotan "ride on the winds, clothed in terror, and she, like the god, belongs to the ‘wütende heer’ [the furious army]." The souls of unbaptised infants were believed to join Holle’s wild company: she may have ridden through the sky, but clearly she was also a goddess of the dead, and as Mother Holle her country is underwater - at the bottom of a well.

So! We have accounts of real severed heads placed in rivers and wells as offerings in prehistory. Legends about heads that can be rejoined to their bodies; beheaded saints ditto. Severed or disembodied oracular heads in legends and fairytales which can speak, protect or punish, bring good fortune and convey prosperity. Prehistoric stone heads, modern stone heads. Wells and springs as entrances to the otherworld. Sacred wells believed to have healing properties. Stone heads set above doorways and in medieval churches and on the central spans of bridges. Twentieth and probably twenty-first century stonemasons still carving archaic heads. It’s all very suggestive, but where does it get us? To be honest I’m not sure. Perhaps the best we can say is that while the primitive or archaic stone head has clearly had meaning for – and evoked responses from – many generations of people, it’s likely those meanings have morphed over time. Maybe looking into the face of a stone head is a bit like looking into a crystal ball, or else an old mirror, or else watching shapes in the clouds as they go strolling across the summer sky, continuously changing, negligent that any shape may look as if it's meant, slowly forming and deforming and reforming, while the human mind races after, trying to make sense of them. John Billingsley says,

Plato, in Timaeus, states that ‘the human head is the image of the world, by which may be understood that it is the primary point of our perception of the world external to us and simultaneously, paradoxically, contains the world within it.

Many years ago, looking at the stone face on the cover of Alan Garner’s book of trickster tales, I wrote a poem which ended:

Junctions in meaningSeldom come on the long ruled road between past and future.You stare and are silent. That is all I can see.

Picture credits

Top photo: copyright Caroline Chappell.

Next four photos: copyright Katherine Langrish

Photo from the book 'Stony Gaze' by John BillingsleyWizard's Well, Alderley Edge: by

Published on March 12, 2019 02:14

February 12, 2019

House Spirits - Brownies, Nisse, Boggarts...

Talking with a group of Girl Guides a while ago, we fell (as you do) into a discussion about house spirits. The best known example, annoyingly enough, is Dobby the house-elf from J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series. I have a soft spot for house spirits, and for me Dobby isn’t the best ambassador for the breed. Rowling takes a freehand approach to creatures from folklore: she happily reinvents the creatures. Her Boggart, for example, resembles not so much the boggarts of folklore, but a nursery bogeyman. ‘Boggarts’, declares Professor Lupin in ‘The Prisoner of Azkaban’, ‘like dark, enclosed spaces. Wardrobes, the gap beneath beds, the cupboards under sinks. …So, the first question we must ask ourselves is, what is a Boggart?’ Of course Hermione comes up with the answer:

"It’s a shape-shifter,” she said. “It can take the shape of whatever it thinks will frighten us most.’

This certainly isn’t what a boggart from folk-lore does, although they are able to take the shape of animals such as black dogs. More about boggarts below. But to return to Dobby, the down-trodden house-elf of the Malfoy family. Dobby is a slave. He lives in terror, forced to punish himself whenever he criticizes his master. It’s a great twist of reinvention, but hardly representative of house spirits in general. From English brownies, boggarts, lobs and hobs, to the Welsh bwbach, from Scandinavian nisses and tomtes and German kobolds, to the Russian domovoi, most house spirits are independent, mischievous, strong-minded characters. And although Rowling employs the folklore motif best known from the Grimms’ fairy tale ‘The Elves and the Shoemaker’ that a gift of clothes will set the creature free (Dobby has to wear a pillowcase instead of clothes), many folk-tales make it clear that far from longing for this gift, many house spirits are perversely and deeply offended by it.

'It was indeed very easy to offend a brownie,' writes the folklorist Katherine Briggs in ‘A Dictionary of Fairies’ (1976):

It was indeed very easy to offend a brownie, and either drive him away or turn him from a brownie into a boggart, in which the mischievous side of the hobgoblin was shown. The Brownie of Cranshaws is a typical example of a brownie offended. An industrious brownie once lived in Cranshaws in Berwickshire, where he saved the corn and thrashed it until people began to take his services for granted and someone remarked that the corn this year was not well mowed or piled up. The brownie heard him, of course, and that night he was heard tramping in and out of the barn muttering:

“It’s no weel mowed! It’s no weel mowed!Then it’s ne’er be mowed by me again:I’ll scatter it ower the Raven staneAnd they’ll hae some wark e’er it’s mowed again.”

Sure enough, the whole harvest was thrown over Raven Crag, about two miles away, and the Brownie of Cranshaws never worked there again.

In folk-lore there’s never any suggestion that humans have a say in whether a brownie comes to work for them or not. Often they seem simply to belong in the house, to have been there for generations, such as the house spirit Belly Blin or Billy Blind in the illustration above, who comes to warn Burd Isabel that her betrothed, Young Bekie, is about to be forced to marry another woman.

‘Ohon, alas!’ says Young Bekie, ‘I know not what to dee; For I canno win to Burd Isbel, An’ she kensnae to come to me.’

XIV

O it fell once upon a day Burd Isbel fell asleep, And up it starts the Billy Blind, And stood at her bed-feet.

XV

‘O waken, waken, Burd Isbel, How can you sleep so soun’, Whan this is Bekie’s wedding day, An’ the marriage gaïn on?

Taking the hob's advice, Burd Isabel sets out with the Billy Blind as her helmsman, to cross the sea, find her lover and prevent the marriage. There's no great sense that she's surprised at this supernatural warning: rather, the Billy Blind (whose name like Puck's may have been generic, as it appears in other ballads too) seems to have been a known household inhabitant who could be expected to offer help when needed.

Some hobs may live locally in a pond, river or hollow, and come to the farm to work. They offer their services freely, and will stay for so long as they are treated with respect and a dish of cream or oatmeal is left out for them. Katherine Briggs writes of another such creature, a hobthrust:

There is a tale of a hobthrust who lived in a cave called Hobthrust Hall and used to leap from there to Carlow Hill, a distance of half a mile. He worked for an innkeeper called Weighall for a nightly wage of a large piece of bread and butter. One night his meal was not put out and he left for ever.

Briggs, of course, wrote her own story about a hobgoblin. ‘Hobberdy Dick’ (1955), set in 17th century Oxfordshire, is one of the most delightful of children’s books, full of folk-lore magic plus a few moments of cold terror as well. Here, Hobberdy Dick scampers up to the Rollright Stones on May Eve, to greet his friends:

‘I’m main pleased to see ye, Grim,’ said Dick, greeting with some respect a venerable hobgoblin from Stow churchyard. ‘…These be cruel hard times. I never thought to see so few here on May Eve; but ‘tis black times for stirring abroad now.’ ‘Us never thought the like would happen again,’ said Grim. ‘Since the old days when the men in white came, and built the new church, and turned I out into the cold yard, I’ve never seen its like for strange doings. First I thought old days had come again, for they led the horses into the church in broad day; but the next day they led them out again. …And then they broke the masonry and smashed up the brave windows of frozen air… and these ten years there’s not been so much as a hobby-horse nor a dancer in the town.’ The Taynton Lob joined them – a small, good-natured creature with prick ears and hair like a mole’s fur on his bullet head. ‘It may be quiet in Stow,’ he said, ‘but there’s more going on than I like in Taynton churchyard.’ ‘What sort?’ said Hobberdy Dick. ‘Women,’ said the Lob half-evasively, ‘and things that feed on ‘em, and counter-ways pacing, and blacknesses.’

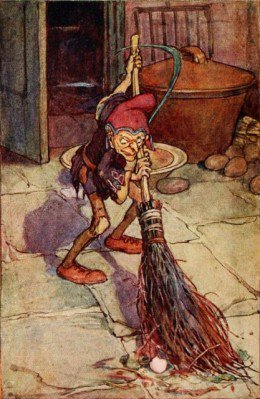

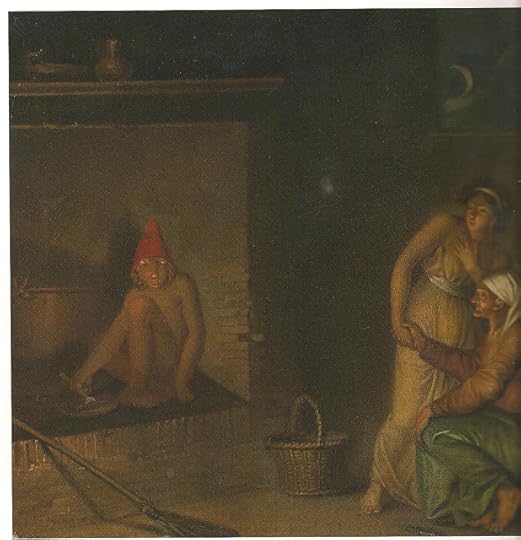

The Scandinavian Nisses are my personal favourites among house spirits. The painting above is by the 18th century Danish painter Nicolai Abraham Abildgaard, and I was once contacted by a New York auction house who asked me to confirm that the subject is indeed a Nisse. As you can see, he wears a red cap and is sitting by the fireside with his broom, eating groute, or buckwheat porridge - but the women of the household are clearly startled and uneasy in his presence. Where the painting is now I do not know, but hope the lucky owner will not object to my sharing the image since I lent a hand in identifying the subject. I first met Nisses in Thomas Keightley’s 1828 compendium ‘The Fairy Mythology’, and made use of some of the legends in my own ‘Troll’ books (available, if you will excuse the quick puff, in one volume under the title ‘West of the Moon’.) I was charmed by their mischief, vanity, naïvety, their occasional bursts of temper and their essential goodwill.

There lived a man at Thrysting, in Jutland, who had a Nis in his barn. This Nis used to attend to the cattle, and at night he would steal fodder for them from the neighbours. One time, the farm boy went along with the Nis to Fugleriis to steal corn. The Nis took as much as he thought he could well carry, but the boy was more covetous, and said, ‘Oh, take more; sure we can rest now and then?’ ‘Rest!’ said the Nis; ‘rest! and what is rest?’ ‘Do what I tell you,’ replied the boy; ‘take more, and we shall find rest when we get out of this.’ The Nis then took more, and they went away with it. But when they were come to the lands of Thrysting, the Nis grew tired, and then the boy said to him, ‘Here now is rest,’ and they both sat down on the side of a little hill. ‘If I had known,’ said the Nis as they were sitting there, ‘if I had known that rest was so good, I’d have carried off all that was in the barn.’

Here is my own Nis (in ‘Troll Fell’, book one of ‘West of the Moon’) disturbing the sleep of young hero Peer Ulffson as he lies in the hay of his uncles’ barn.

A strange sound crept into Peer’s sleep. He dreamed of a hoarse little voice, panting and muttering to itself, ‘Up we go! Here we are!’ There was a scrabbling like rats in the rafters, and a smell of porridge. Peer rolled over. ‘Up we go,’ muttered the hoarse little voice again, and then more loudly, ‘Move over, you great fat hen. Budge, I say!’ This was followed by a squawk. One of the hens fell off the rafter and minced indignantly away to find another perch. Peer screwed up his eyes and tried to focus. He could see nothing but black shapes and shadows. ‘Aaah!’ A long sigh from overhead set his hair on end. The smell of porridge was quite strong. There came a sound of lapping or slurping. This went on for a few minutes. Peer listened, fascinated. ‘No butter!’ the little voice said discontentedly. ‘No butter in me groute!’ It mumbled to itself in disappointment. ‘The cheapskates, the skinflints, the hard-heared misers! But wait. Maybe the butter’s at the bottom. Let’s find out.’ The slurping began again. Next came a sucking sound, as if the person – or whatever it was – had scraped the bowl with its fingers and was licking them off. There was a silence. ‘No butter,’ sulked the voice in deep displeasure. A wooden bowl dropped out of the rafters straight on to Peer’s head.

Our personal Nis, based on Abildgaard's, sits by our fire...

Our personal Nis, based on Abildgaard's, sits by our fire...In Russia, the house spirits are named domovoi, often given the honorific titles of ‘master’ or ‘grandfather’. According to Elizabeth Warner in ‘Russian Myths’ (British Library, 2002) the domovoi looked like a dwarfish old man, bright-eyed and covered with hair, who dressed in peasant clothes and went barefoot. ‘Sometimes he took on the shape of a cat or dog, frog, rat or other animal. By and large, however, he remained invisible, his presence revealed only by the sounds of rustling or scampering.’ Like nisses and brownies, domovoi often busied themselves with household tasks, or with looking after animals in the stables. Sometimes they would befriend a particular cow or horse, which would flourish under their care. But they could also be mischievous, pinching the humans black and blue at night, or throwing dishes and pans about like a poltergeist. One last duty of the domovoi was to foretell ill events. ‘When a family member was awakened in the middle of the night by the touch of a furry hand that was cold and rough, some disaster was likely to occur.’

Temperamental, unpredictable, generous, hard-working, sometimes dangerous, the house spirit is reminiscent of the household gods of the Bible, the teraphim which Rachel stole from her father Laban (Genesis 31, 34), and of the Lares and Penates of the Romans. Better to have your own, humble little household spirit who could be pleased with a dish of cream or a bowl of porridge, folk may well have thought, than try to gain the attention of the greater gods. And so the house spirit became a member of the family, helping and hindering in his own inimitable way.

Picture credits:

Brownie by Arthur Rackham

Billy Blind and Burd Isbel by Arthur Rackham Wikipedia

Lob Lie By the Fire by Dorothy P Lathrop: 'Down-a-down-derry,' Fairy Poems by Walter de la Mare 1922 Nisse by Nicolai Abrahan Abilgaard Domovoi by Ivan Bilibin - Wikimedia Commons Lararium: shrine of household gods from Pompei: photo by Claus Ableiter - https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

Published on February 12, 2019 09:34

December 20, 2018

In Search of Janet, Queen of the Fairies

The village of Malham in the Yorkshire Dales is set in a landscape of remarkable natural beauty which includes the great curved cliff of Malham Cove and the dramatic narrow gorge of Gordale Scar. Turner painted Malham Cove (see above) and Wordsworth wrote a sonnet about Gordale, 'terrific as the lair/Where lions crouch', and imagined it haunted by the deity of the waterfall 'with oozy hair and mineral crown'. Romantic notions like these may well have shaped a local legend, as we shall see.

You can walk to the Scar along the road from the village, but it’s prettier to take the path by the side of Gordale beck. (A gore or geir is an ancient name for an angular or triangular piece of land, an appropriate term for the ever-narrowing valley which leads into the gorge.) The streamside walk leads through flat pastures into a wooded limestone ravine called Little Gordale, in springtime full of the starry white flowers of wild garlic, the beck tumbling ever down over stones at your right hand. Before you get to Gordale Scar itself, in fact at about the half-way point, the winding up-and-down path brings you to the brink of a deep pool at the foot of a small waterfall – Janet’s Foss. Over on the far side of the pool is a shallow cave tucked under a ledge of rock, and if you cross the natural stepping stones that dam the pool, and clamber up the rockface to the right of the fall, you may – if the water isn’t roaring down too hard – wriggle your way into a much smaller cave that’s actually hidden behind the waterfall itself. It’s pretty damp. But this is the home of Janet, the local fairy queen.

Everyone in Malham knows this. But though I lived in the village for years and my parents lived there for decades, I was never able to find out any more about Janet the fairy queen. No one local ever seemed to have heard any stories about her. And I recently started wondering … well, is she a genuine piece of folklore? Or could she have been invented relatively recently, perhaps as a tourist attraction? All I had to go on was what Arthur Raistrick wrote in his 1947 book “Malham and Malham Moor”:

Foss is the old Norse name for a waterfall, and Janet was believed to be the queen of the local fairies … The fall is not high, but is remarkable for the beautiful tufaThat’s it. He has nothing more to add. Could Janet be traced further back in time? I decided to find out.

My first port of call was an 1891 book called “Through Airedale from Goole to Malham”, written by one Harry Speight under the pseudonym ‘Johnnie Gray’. Writing of the various walks to be had around Malham, he provides both a factual and a fanciful description of ‘Janet’s Cave’:

About a quarter of a mile above the last houses on the Gordale road a step-stile on the right (opposite a row of thorns) leads down fields towards a barn, near which a foot-bridge crosses the Gordale beck… By keeping this side of the stream, a walk of little more than half a mile conducts through the wooded ravine of Little Gordale to Janet’s Cave, a charming sylvan retreat of which, in the words of Milton, we may justly exclaim, In shadier bower More sacred and sequestered, though but feigned, Pan or Sylvanus never slept, nor Nymph Nor Faunus haunted.A small cascade set within a living framework of moss and foliage; in Autumn the scarlet berries of the rowan or witch-tree contrasting beautifully with the white foam, renders the scene exceedingly attractive. And what more fit and abiding place for Queen Janet and her airy little people, whose humble dwelling, guarded by the oft-swollen stream, we see in the rock above! Imagination alone is left to picture the lone witching hour when the moon-silvered waterfall pours forth its music to the dance of the fairies!

It’s striking that this late Victorian writer turns what’s really a set of walking instructions (‘take the right-hand stile opposite the row of thorn-bushes’) into something more picturesque. Gray wants to remind us that a rowan is a ‘witch-tree’; he brings in classical nymphs and fauns; ‘airy little’ fairies dance in the silver moonlight of the ‘witching hour’ – before the prosaic conclusion:

Emerging from this cool and shady recess the visitor descends a field path to a small gate, whence the return to Malham may be made l. by the high-road; or r. to Gordale Scar.

Flowery as it is, this account demonstrates that a tradition of a fairy queen named Janet was already associated with the spot by 1895, though her name is attached to the cave rather than to the ‘foss’ or waterfall itself. “Jennet’s Cave” is also the name marked on the 1853 Ordnance Survey map of the area (six inches to the mile), proving that the name at least was current a good forty years before Johnnie Gray’s book.

Delving further into the past, in 1839 a schoolteacher named Robert Story, ‘of Gargrave, Craven’ (a village about eight miles from Malham) published a remarkable play in Shakespearian blank verse, dedicated to “Miss Currer of Eshton Hall”. Miss Frances Richardson-Currer was an accomplished woman who collected historical manuscripts and rare printed works, and Eshton Hall was one of the most important houses around, situated in parkland a mile outside Gargrave on the Malham road. Story, who was born at Wark, Northumberland, in 1795, and whose father was a farmhand, had worked as a shepherd and a gardener before discovering a love of poetry. He became a schoolteacher and moved to Gargrave in 1820, where he gained a reputation as ‘the Craven poet’. His play – so far as I know, never performed – is called “The Outlaw”. It’s set in and around Malham and Goredale – most particularly in the mysterious “Gennet’s Cave”, renowned habitation of the fairy queen.

“The Outlaw” is great fun, an extravagant, fast-moving melodrama, and the poetry’s not bad. Knowing the local area as well as she must have done, I can see how much pleasure it must have given Miss Currer to read the play, especially since in his letter of dedication, Robert Story flatteringly explains that his heroine Lady Margaret Percy is based upon herself! Henry the Outlaw (of course he is a disguised nobleman) leads a band of merry robbers in the style of Robin Hood. We first meet him carousing on the Abbot of Sawley’s stolen ale at a friendly inn under Kilnsey Crag, and singing a defiant song:

At Malham there is flowing beerBut few to drink it but the elves,And those prefer the gelid waveThat from the Fall leads out its line,But when we sit in Gennet’s Cave,Our choice is still the Abbot’s wine.

So little Malham is the home of elves who love cold water, and Gennet’s Cave is the hideout of an outlaw band! Of course it never happened, and in any case the author exaggerates. You would be hard put to cram more than a couple of outlaws into either of the caves at Janet’s Foss, still less roast ‘savoury haunches’ of venison there on open fires. It’s hard to stand up even in the larger cave, and the smaller one is barely more than a crawl space. But, poetic licence. Anyway. We never meet any actual fairies in this play, but they are frequently spoken of as Henry, now disguised as a monk, escorts beautiful Lady Margaret, with whom he is in love, through the wild landscape – whilst his ‘secret enemy’ Norton, another outlaw, plots against him. And there's an obligatory ‘cottage girl’, Fanny Ashton from nearby Kirkby Malham, who is in love with Henry herself and runs mad when Norton tells her of Henry’s attachment to Margaret. True to genre, her madness takes the form of hanging around graveyards and singing mournful songs about lost love, flowers and moonlight.

Sketch: Gordale Scar, James Ward, 1811

Sketch: Gordale Scar, James Ward, 1811The scheming Norton disguises himself as Henry disguised as a monk – impersonating him in order to frame him, if you follow me – and sets up an ambush for the Lady Margaret at Gordale Scar, where she has come to view the chasm. There’s some vivid Romantic scene painting here:

All gaze in silenceNORTONYour silence moves no wonder. Gordale hath,In its first burst of unexpected grandeurA spell to awe the soul and chain the tongue.How great its Maker then! LADY MARGARET… it might seem a towerWhose architects were giants, did yon streamMar not the fancy. RODDAMOr a cavern hewnFrom out the solid rock by genii! LADY EMMAOr fairy palace, by enchantment raisedTo hold the elfin court in! LADY MARGARET‘Tis a sceneToo stern and gloomy for those gentle beings,That love the green dell and the moonlight ring.I like my first impression.

Gordale Scar is indeed not the sort of place you would associate with skipping fairies, but each and every one of the characters is determined to apply some fanciful simile to the landscape. The play is supposed to be set in the time of Henry VIII, but the characters are so unashamedly Romantic that Lady Margaret is reluctant to tear herself away from Gordale even as a thunderstorm looms. “It were a sin ‘gainst taste,” she cries, “So soon/To quit this scene of wild sublimity”! Oh that word ‘taste’, so redolent of 18th and early 19thcentury aesthetics when the appreciation of sublime landscapes became a fashionable and almost a spiritual duty! I can’t resist quoting the remainder of Lady Margaret’s speech, since it really does conjure up the impression the Scar makes on visitors:

The shadows deepen, as the clouds o’ersweepThe almost-meeting crags above our head,Until the cataract, that whitely fallsAs if from heaven, becomes its only light – Seeming, indeed, a gush of moonlight pouredThrough a rent cloud, when all besides is gloom.

Like Lady Margaret, people visiting the Lakes or the Dales – not yet an easy journey in the early 1800s – were determined to get their money’s worth out of the experience. Writing at the more hard-headed end of the century, Johnnie Gray points out that some early accounts almost double the true heights of some hills, representing Whernside and Pen-y-ghent as mountains well over 5000 feet high, for instance. This tendency to exaggerate and romanticize local attractions means we cannot assume, when the lovelorn Fanny talks about the Fairy Queen Gennet, that her words are based on genuine folklore.

This is the Fairy’s cave. Hast seen her, Norton? But she ne’er shows herself, except to eyes That soon must close in death.

Just possibly this may be a remnant of a once-held belief that to meet the fairy Gennet was an omen of death. Or it may be Robert Story’s invention, since poor Fanny is about to be stabbed in the heart and die (after breathing twenty-two lines of farewell) in Henry’s arms. There’s no way to know.

Not every visitor was prepared to rhapsodise about fairies and elves. Two years previously, in 1837, amateur botanist Samuel King of Halifax was touring the Dales with an eye to rare plants and set out from Malham to visit “Jenny’s Cave”. But he never got there: having left the excursion too late in the day he turned back as it grew dark, sensibly avoiding the risk of a sprained ankle or a tumble into the beck. And he did not mention any fairies; perhaps as a man of science he took no interest. All the same, they were there.Thomas Hurtley was a native of Malham. He was the village schoolmaster, and Johnnie Gray knew of him, writing:

Hurtley died about 1835 and was buried in Kirkby churchyard. His granddaughter, Miss Hurtley, lives at Malham now [ie: in 1891]. She is an active, chatty old dame, (in her 80th year) and keeps a small lodging and refreshment house on the Gordale road.’

In 1786 Thomas Hurtley published a book about Malhamdale called ‘A Concise Account of some Natural Curiosities, in the Environs of Malham, in Craven, Yorkshire’. His intention was to praise the ‘beauties and Topography’ of his own region:

Born in the midst of these romantic Mountains, where his Ancestors once enjoyed a happy independence;– his mind naturally impressed with admiration of the magnificent worlds of the Supreme Architect;– remote from the hurry of business, and partly secluded from any knowledge of the world except what he has collected from a few books, the Author of the following sheets entertains a hope that his talents may not have been uselessly employed in endeavouring to describe a Country, which seems in his (perhaps partial) estimation to have been hitherto unaccountably neglected.

He really does his utmost. Gordale, for example, is a ‘stupendous Pavilion of sable Rock apparently rent asunder by some dreadful although inscrutable elementary Convulsion’; it is ‘tremendous and umbrageous’, a ‘gloomy Cavern’. But Hurtley also adds charming personal touches, telling how the last time he ‘paid his vows’ to the ‘Genius’ of the Scar, one of the ‘haggard Goats’ which roamed the cliffs ‘stood and scratched an ear upon a shelf where I would not have stood stock still “For all beneath the Moon.”’ I love that! The book is of general interest to anyone who knows Malham: but concerning Janet’s Foss, Hurtley tells us that ‘GENNET’S CAVE’ is

…so called from the Queen or Governess of a numerous Tribe of Fairies which a still prevalent tradition assures us anciently infested it. It is a spacious and not inelegant Cavern, having a dry tessellated Floor, arched over with solid Rock resembling an Umbrella, surrounded and encircled with a verdant Arbour.

Whether any of these imaginary Beings ever frequented this Ivy-circled Mansion is needless to dispute, but in later times it has been occupied by a much more profitable tenantry;– the Smelters of a valuable Mine of Copper from Pikedaw in the Manor of West-Malham, then belonging to the Lambert Family… To this day there is the evident Ruins of a Smelt Mill.

That phrase, ‘a still prevalent tradition’, suggests that some folk-belief in a fairy ‘infestation’ (gorgeous word!) of Janet’s Foss was old, though perhaps fading, by 1786. And here history fails us. I have found no earlier record. But I would like to speculate a little.

Why ‘Janet’? Janet – or Jennet, Jenny, Gennet, however you spell it – the name appears consistently in all accounts spanning 230 years. It’s not as though someone suddenly names the fairy queen in the middle of the record. The small cave behind the waterfall has been Jennet’s home as far back as she can be traced.

Now it so happens that across the north of England, particularly in Lancashire but also in Yorkshire, there are folk tales about a malevolent water spirit or nixie who goes by the name of ‘Jenny Greenteeth’. (Variants include ‘Ginny’,‘Jeannie’, etc.) In 1870 John Higson, a correspondent to the journal ‘Notes and Queries’To restrain their children from venturing too near the numerous pits and pools which were found in every fold and field, a demoness or guardian was stated to crouch at the bottom. She was known as ‘Jenny Greenteeth’, and was reported to prey upon children...

Similar stories were told at Walton-le-Dale, at Warrington, and at Fairfield near Buxton in Derbyshire as well as Manchester, where in about 1800 a stream called ‘Shooter’s Brook’ passed in a culvert under the aqueduct which carried the Manchester and Ashton-under-Lyme canal over Store Street, near the London Road Station:

At that period there existed an opening or break left in the culvert forming a dangerous spot for children to play beside, and yet they often selected it. Their mothers tried to destroy the fascination by stating that Jenny Greenteeth laid in wait at the bottom to ‘nab’ children playing there.

Higson claims not to know of any Yorkshire examples of the story, but John Nicholson, in ‘Folk Lore of East Yorkshire’ (1890) tells of a hole like ‘a dry pond’ near Flamborough in which a girl committed suicide (presumably by drowning before the pond dried) and became a dangerous spirit:

It is believed that any one bold enough to run nine times around this place will see Jenny’s spirit come out, dressed in white; but no one has yet been bold enough to venture more than eight times, for then Jenny’s spirit called out,‘Ah’ll tee on me bonnet,An’ put on me shoe,An if thoo’s nut off,Ah’ll seean catch you!’A farmer, some years ago, galloped around it on horseback, and Jenny did come out, to the great terror of the farmer, he put spurs to his horse and galloped off as fast as he could, the spirit after him. Just on entering the village, the spirit, for reasons unknown, declined to proceed further, but bit a piece clean out of the horse’s flank, and the old mare had a white patch there to her dying day.

The pool and waterfall at Janet’s Foss might well be considered a dangerous place for children to play, especially when the beck runs high after rain, and with those tempting caves to scramble up and explore. It’s true that Gennet is supposed to live in the cave behind the fall, rather than in the pool itself, but the Stockport manifestation of ‘Jenny Greenteeth’ perches in the tops of trees! Given all this, and given the chance, however slight, that Robert Story is repeating a genuine piece of folklore when he suggests that people see the fairy of Gennet’s Cave only when they are at the brink of death, I put forward the tentative suggestion that she may originally have been another incarnation of Jenny Greenteeth – the bogywoman conjured by mothers in an attempt to keep their children safe. When the gentrified classes began visiting the Dales in the late 1700s and asked the locals about the ‘Gennet’ of Gennet’s Cave, the simplest answer was probably to shrug and say ‘a fairy’. And the fairies which visitors could most easily and pleasantly imagine were the romantic, tiny, dancing-by-moonlight kind. Not a lurking monster with ‘sinewy arms’, as Higson describes her, waiting to drag children to their deaths.

Näcken (Water Spirit) by Ernst Josephsen