Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 11

October 13, 2020

Goddesses, Queens and Witch-Queens

Here we are in October with Hallowe'en coming up in only a couple of weeks, and it seems a good time to write a post about witches. (In fact, maybe two posts. Maybe three.)

‘Witch’ is not a neutral word. There can be good wizards or bad wizards, it seems, so that when you encounter a fictional wizard you cannot be certain at first which way he leans. Gandalf is good, Saruman was good once and then turned out to be bad. But the default option for any fictional witch is wickedness unless qualifying adjectives are used, such as ‘white’ (or possibly 'hedge'). Why? After all, wizards and witches both use magic, so why the gender-based difference? In later posts I want to consider some of the many witches who appear in children’s literature. But there’s some interesting background to cover first.

Off the top of my head, the earliest witch I can think of is the Witch of En-dor in the Hebrew Bible (1 Samuel 28: you see her, pictured below). In fact the Bible never describes her as a witch, but the inference down the centuries has been that since she has a familiar spirit and can communicate with the dead, that’s what she must be. Nowadays she'd probably be called a medium, but the column header of my 1810 Bible states quite definitely: ‘Saul confulteth a witch’. In spite of having banished from the land all who have trafficked with ghosts and spirits, King Saul – desperate because he's got a Philistine army mustering on his borders and God is ignoring him – visits the woman secretly in disguise and asks her to call up the spirit of the prophet Samuel, whom he hopes will give him counsel. (Imagine if Aragorn had tried to summon up the ghost of Gandalf after his plunge into the abyss – it might not have been the best plan.) With extreme reluctance, the woman obliges, and though it’s not clear from the Bible account if Saul ever sees Samuel at all, the woman does: she describes him rising from the earth ‘like an old man coming up, wrapped in a cloak’. Of course it ends in disaster for Saul, as the displeased Samuel foretells his death.

The narrative is critical of Saul’s hypocrisy in banning consultations with the dead and then employing them himself, but it’s hard not to feel some sympathy with the hard-pressed king. It’s a time of bloody conflict: Samuel informs Saul that one reason the Lord has ‘torn the kingdom from your hand and given it to … David’ is that Saul has ‘not obeyed the Lord or executed his judgement on the Amalekites’. For which read: hasn't massacred them. But the Bible account isn't especially critical of the woman herself. While Saul collapses in terror at Samuel’s words, she first scolds him – ‘I listened to what you said and I risked my life to obey you’ – and then cooks him a much-needed meal. Saul has put her in an awkward position, and she did what he asked, that’s all. She really doesn't deserve to go down in history as a wicked witch.

Then why in popular culture, are witches nearly always women? To put it another way, why has women’s wisdom over the past couple of millennia so often been distrusted as likely to be ungodly in origin and therefore evil? In one sense it’s obvious: by their nature polytheisms may be (they aren’t always) relaxed about other gods, able to welcome or absorb them. But a monotheistic religion, if it is to remain so, must insist that rival gods are evil or null. The Christian martyrs suffered because of a head-on collision between a system that was uninterested in private faith but required a public gesture of submission to the Roman State by a sacrifice to its gods, especially the reigning emperor – and a system that absolutely forbade submission to any but One.

And monotheisms seem to centre on gods, male gods. There seems no special reason why there couldn't be a monotheistic religion centred on a goddess but I'm not aware that such a thing has ever existed. Of course, to say that God is male or female makes no sense if he/she/they is pure spirit, but people naturally anthropomorphise. An inscription dated circa 800 BCE found on a large storage jar in north-east Sinai reads in part: ‘May you be blessed by Yahweh and his Asherah’, while another at a site a few miles from Hebron reads: ‘Uriah the rich has caused it to be written: Blessed be Uriah by Yahweh and his Asherah: from his enemies he has saved him.’ This, says Rafael Patai in his book The Hebrew Goddess , suggests with other evidence that ‘the worship of [the goddess] Asherah as the consort of Yahweh … was an integral element of religious life in ancient Israel prior to the reforms introduced by King Josiah in 621 BCE.’

Ivory box-lid depicting Asherah

Ivory box-lid depicting Asherah representing the Tree of Life feeding a pair of goats. Though a God who could be symbolically addressed as King, Lord of Hosts, Master of the Universe and so on may have been a good fit for a patriarchal, warlike Iron Age society, Asherah was very important too. Patai explains:

"For about six centuries [after the arrival of the Israelite tribes in Canaan]; that is to say, down to the destruction of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar in 586 BCE, the Hebrews worshipped Asherah (and next to her also other, originally Canaanite gods and goddesses) in most places and most times. Only intermittently, although with gradually increasing intensity and frequency, did the prophetic demand for the worship of Yahweh as the one and only god make itself be heard and was heeded by the people and their leaders." Asherah, who is named many times in the Bible, was the top Canaanite mother-goddess right back to the 14thcentury BCE. As ‘Lady Asherah of the Sea’ or simply Elath (‘goddess’) her husband was the chief god El (‘god’) who ruled the sky, Baal (‘lord’) was their son, and the war-goddess Anat was their daughter. Asherah’s worship in the form of a cultic image, a pole or pillar, was introduced into the temple by Rehoboam circa 928 BCE: in following centuries such pillars, set up in hilltop shrines, were being destroyed by reforming Yahwistic kings like Hezekiah and Josiah. Despite these struggles her cult and that of her daughter Anat/Astarte remained popular right down to the fall of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Temple in 586 BCE. When the prophet Jeremiah told the people that the calamity of the Exile had been Yahweh’s punishment for their wicked idolatry, they rejected it. In fact they claimed it was the other way around, that their troubles were all due to having neglected the goddess who used to care for them.

"We will not listen to what you tell us … We will burn incense to the Queen of Heaven and pour libations to her as we used to do, we, our fathers, our kings and our princes, in the cities of Judah and the streets of Jerusalem. For then we had plenty of food and were content; no calamity touched us. But since we stopped burning incense and pouring libations to her, we have been in great want and have fallen victim to sword and famine. And the women said, ‘It was not we alone who burned incense to the Queen of Heaven, and poured libations to her. Our husbands knew very well that we were making cakes marked with her image, and pouring libations to her.’ " [Jeremiah, 44, 15-19] It must have been troubling to give up (and risk offending) such a powerful protector. Asherah was the home-town goddess worshipped by the princess of Sidon, Jezebel, daughter of the ruler of the Phoenician empire, who married the Israelite king Ahab (873-852 BCE). It was usual for princesses marrying abroad to retain their own religious customs, so Ahab made a shrine for Jezebel where she could worship Baal and Asherah. This went down badly with the Yahwist prophet Elijah and his supporters, and Jezebel wasn’t the conciliatory sort. A religious tit-for-tat ensued, in which both sides destroyed the others' shrines and slaughtered their priests. It couldn't end well.

How much of this really happened is debatable: the scholar and archeologist Israel Finkelsteinwrites that the Biblical narrative of Jezebel and Ahab contains so many inconsistencies and anachronisms that it should be regarded as ‘more of a historical novel than an accurate historical chronicle’. But I’ve always liked Jezebel's courage and style as she defies her last enemy Jehu – frankly a thug: a king’s officer whom Elijah’s protegée and successor Elisha hand-picked to kill the king and take his place. Ahab is dead by now, and the new king is Jezebel’s son-in-law Jehoram. Seeing Jehu driving furiously towards the city of Jezreel in his chariot, Jehoram sends out messengers to enquire his purpose; when Jehu ignores them, he comes out to meet him himself. ‘Is it peace, Jehu?’ he optimistically enquires. Jehu responds, ‘Do you call it peace when your mother Jezebel keeps up her obscene idol-worship and monstrous sorceries?’ As Jehoram wheels around to flee, Jehu bends his bow and shoots him in the back.

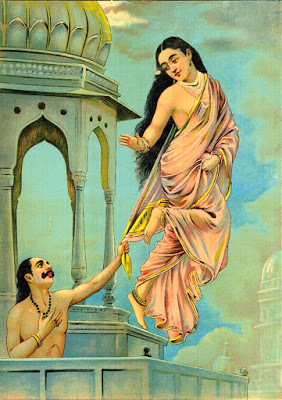

Hearing this news, Jezebel must have known she was a dead woman. She reacts like Shakespeare’s Cleopatra (‘Give me my robe, put on my crown. I have/Immortal longings in me…’) as with her hair dressed and her eyes painted, she stands royally visible in the window of the palace, looking down. As Jehu enters the gate below her, she calls a deliberately provocative challenge: ‘Is it peace, you Zimri, you murderer of your master?’ Zimri was a chariot commander who decades before had murdered his lord King Elah of Judah, after which he lived only seven days. For her to use his name as an insult suggests his treachery had become a byword: to call someone ‘Zimri’ may have been very like calling them ‘Judas’ now.

Jehu looked up at the window and said, ‘Who is on my side, who?’ Two or three eunuchs looked out, and he said, ‘Throw her down.’ They threw her down, and some of her blood splashed on the wall and the horses, who trampled her underfoot. Then he went in and ate and drank. ‘See to this accursed woman,’ he said, ‘and bury her, for she is a king’s daughter.’ But when they went to bury her they found nothing of her but the skull, the feet, and the palms of the hands.

Jehu claims that Jezebel's end fulfills Elijah’s prophecy that dogs would devour her and no one would be able to say where she was buried. Maybe so, but her splendidly arrogant defiance lives on. She was certainly no angel – the story says she ordered Naboth’s murder so that her husband Ahab could take his vineyard – but it hardly compares with the violence and cruelty of Jehu who continues his service to Yahweh by having all seventy princes of the house of Ahab slain and their heads piled in two heaps on either side of the city gate. He follows this deed with yet more massacres, and is praised by Yahweh for doing well. Then as now, atrocities are only committed by the other side.

Queen Jezebel was not a witch queen, but she might as well have been one. Her name is now practically synonymous with a wicked, glamorous, dangerous woman. What is a witch queen but a stereotype of feared and disapproved-of female power? The violence of Jezebel's death, along with the contempt and hatred which Jehu expresses towards her, testifies to the violence of feeling among Yahweh’s extremist followers: the effects of that far-off struggle persist to this day. Calling a woman a witch is never complimentary, but neither is it entirely without positive implications. A witch is a woman whose enemies perceive her as (illicitly) powerful, inspiring their fear and envy. A witch is a woman who cannot be ignored.

Next time: Witch Queens and Women's Power in YA & children's literature.

Picture credits:

Morgan le Fay - by Frederick Sandys, 1864 The Witch of Endor (detail from "The Endorian Sorceress Invokes the Shade of Samuel") by Dmitry Nikiforovich Martynov, 1857Ivory box-lid found at Ugarit (1300 BCE) depicting Asherah representing the Tree of Life, feeding a pair of goats.Jezebel - by John Liston Byam Shaw (1872 - 1919)

Published on October 13, 2020 05:36

October 6, 2020

Envoi to Strong Heroines: MAID MALEEN, a study of endurance through trauma

This essay was originally published in the 12th issue of Gramarye, Winter 2017

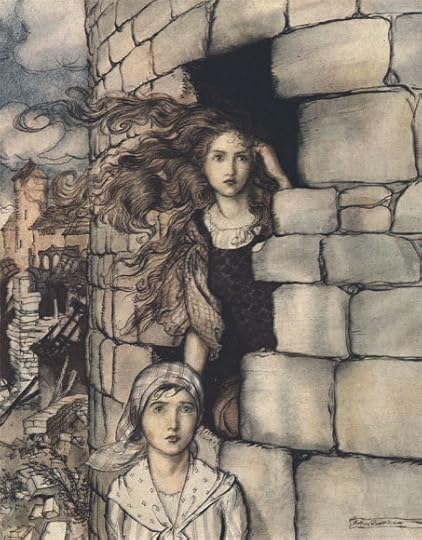

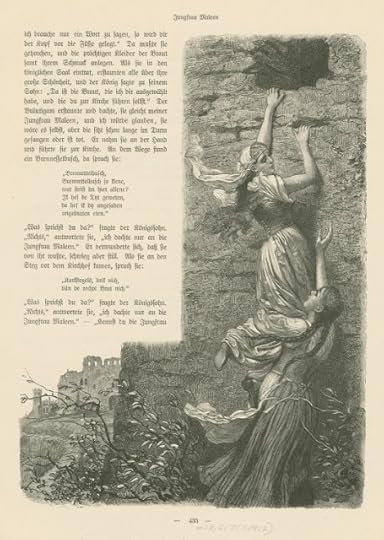

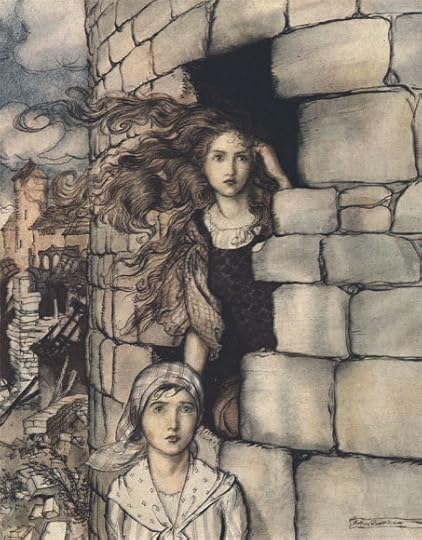

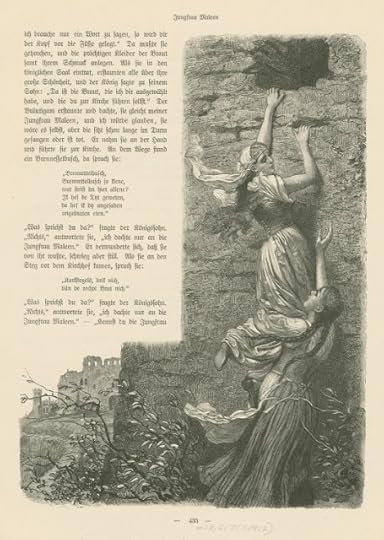

To round off my series of thirty fairytales which feature strong heroines, I'd like to repost an essay I wrote a couple of years ago about a fairy tale heroine whom many might not consider strong. For how can a girl who spends seven years imprisoned in a dark tower be an example of strength? Especially one who then seems to sink into a dark pit of post-traumatic depression? I argue that she is indeed an example of strength, and that our culture's focus on the kind of physical courage expressed in fighting and action leads us to forget or underestimate other forms of bravery. There isn't very much fighting in fairy tales! Often what they celebrate is the mental and spiritual courage all of us need to persist, endure, carry on in the face of pain, hardship, rejection, persecution. And this form of courage is often the courage of women. You can read Maid Maleen in full at this link, but I paraphrase it below. Though included in the Grimms' fairy tales (KHM 198), it's never been popular. It was first published as Jungfer MaleenSeven lang years I served for thee The glassy hill I clamb for theeThe bluidy shirt I wrang for theeAnd wilt thou no wauken and turn to me?

The time passed by, and by the decline of food and drink they knew that the seven years were coming to an end. They thought the moment of their deliverance was come; but no stroke of the hammer was heard, no stone fell out of the wall. All that prisoner-passivity and patience turns out to have been useless. The two women now seek actively to escape. They could have done so at any time before, but the weight of the king’s sentence, and their belief in it, lay upon them. Here Müllenhoff, emphasing the girls’ self-reliance, writes, ‘So they had to help themselves.’ (‘So mussten sie sich denn selber helfen.’) In the Grimms’ version Maid Maleen takes charge of their destiny but her words hint at the desperation she feels: ‘Maid Maleen said, “We must try our last chance, and see if we can break through the wall.”’ (‘Da sprach die Jungfrau Maleen: “Wir müssen das letzte versuchen und sehen, ob wir die Mauer dürchbrechen.”) Taking turns with a bread knife Maid Maleen and her maid scrape away the mortar between the stones and after three days of ‘great labour’ they push out a block and break through. Light rushes in. At last they can see the sky and breathe fresh air, but a new shock awaits: Her father’s castle lay in ruins, the town and villages were, so far as could be seen, destroyed by fire, the fields far and wide laid to waste, and no human being was visible.

At this point Müllenhof repeats the purposeful phrase, ‘So they had to help themselves.’ In the Grimms’ tale the crushing effect of the discovery is conveyed by a rhetorical question, ‘But where were they to go?’ (‘Aber wo wollten sie sich hinwenden?’) During their imprisonment the world has changed. Huge events have taken place, of which they in their isolation were completely unaware. How is a prisoner to adjust, adapt? New-born into this empty, post-apocalyptic land, their hard-won freedom brings no joy. They can only wander, starving, living on handfuls of nettles, till they cross the border into a country ruled by that very King whose son was Maid Maleen’s lover. And he is about to marry another woman. At this point in other ‘lost bridegroom’ tales there is a sense of great purpose: the girl’s arrival at the place where her lover resides is the pinnacle of her journey, and she is full of determination to win him back. By contrast Maid Maleen’s wanderings have been aimless. She’s not aspiring to find and marry her sweetheart, she’s simply trying to survive. Even when she finds work as a kitchenmaid in the palace and is employed in carrying meals to the chamber of the royal-bride-to-be, she seems stunned, passive, futureless. When forced under threat of death to impersonate the false bride, she suffers it as another indignity rather than seizing the opportunity to reveal herself to the prince. Nothing could be further from the confident resolve of the heroine of The Black Bull of Norroway, or the mutually beneficial alliance of the two brides in The Girl Clad in Mouse-Skin. Significantly at this point, as if to emphasise Maid Maleen’s degradation, her own maid disappears from the story. Maid Maleen is the servant now. And so on her way to the church, dressed as the princess she used to be and holding her true love’s hand, Maid Maleen sees a nettle growing by the wayside and it triggers a crisis. I once ate nettles raw. Can I really be Maid Maleen? Who am I? ‘Do you know Maid Maleen?’ the prince asks eagerly as she murmurs the name. And she denies it. ‘No, how should I know her? I have only heard of her.’ Is she testing him? Is this a secret reproach? I don’t think so. Maid Maleen has been a princess, a prisoner and a beggar. Her father forgot her. Her lover forgot her. The world forgot her. Now she is a kitchen-maid impersonating a princess, a pretender and cheat. ‘I am not the true bride,’ she repeats, afraid that the honest world will reject her, the foot-bridge break under her step, the church door split as she passes through. ‘I am not the true bride.’ In no other fairy tale I know of does this rejection of self occur. Maid Maleen is the true bride, but dispossessed, traumatised, damaged. There is a poignancy in her behaviour which I find deeply moving. The world has broken under her and she cannot trust it, cannot trust herself. Her loss of identity is such that she will do nothing to reinstate herself, will not speak another word. It is up to the prince to put the false bride to the test as, unable to answer his questions, she tacitly admits her deceit: I must go out unto my maid Who keeps my thoughts for me. Should we feel sorry for the ugly bride? That would be a very modern reaction. Fairy tales operate by particular rules. Youthful beauty almost always signifies goodness, ugliness its opposite: what you see is what you get. Nevertheless Heather Robbins, to whom I owe the translation of Jungfer Maleen, has made the interesting point that unlike, say, the troll bride of The Black Bull of Norroway, this particular false bride knows she is ugly, and that when she repeats Maid Maleen’s words to the prince, she is being forced to utter the truth about herself: ‘I am not the true bride’. Is it an elaborate trap? Can Maid Maleen be deliberately tricking her? In another tale she might. It’s a ruse I can imagine Tatterhood (#15 in this series) or the Mastermaid (#7) or any number of other ingenious heroines might employ. It could even be true of Müllenhoff’s tale, but the Grimms’ story just doesn’t feel like that – at least to me. In The Girl Clad in Mouse-Skin, the mirror-opposite situation of the two brides works to their advantage. In Maid Maleen, the heroine and the false bride are so strikingly alike in their low self-esteem that on a psychological level the ugly false bride may even be Maid Maleen. In a powerful painting, False Bride Maleen, Edouard Manet makes manifest the darkness of the fairytale: the black fan guarding the face, the black dress, colour of death, the secrecy.

In another tale she might. It’s a ruse I can imagine Tatterhood (#15 in this series) or the Mastermaid (#7) or any number of other ingenious heroines might employ. It could even be true of Müllenhoff’s tale, but the Grimms’ story just doesn’t feel like that – at least to me. In The Girl Clad in Mouse-Skin, the mirror-opposite situation of the two brides works to their advantage. In Maid Maleen, the heroine and the false bride are so strikingly alike in their low self-esteem that on a psychological level the ugly false bride may even be Maid Maleen. In a powerful painting, False Bride Maleen, Edouard Manet makes manifest the darkness of the fairytale: the black fan guarding the face, the black dress, colour of death, the secrecy.

The truth comes out. The prince wishes to see the mysterious maidservant. In a final effort the false bride sends her servants to kill Maid Maleen. This shock of sudden physical danger at last provokes a reaction: Maid Maleen screams so loudly that the prince rushes to her aid. Here the Grimms’ telling of the tale diverges significantly from that of Müllenhoff, in whose version the prince’s eyes are opened ‘and he saw that she was no other than his former beautiful true bride that he had quite forgotten, that Maid Maleen was the same woman she herself had spoken about on the way to church.’ (‘…und er sah, dass sie auch keine andre sei als seine ehemalige Braut, die er ganz vergessen hatte, das die Jungfer Maleen selber sei, von er sie immer auf dem Kirchwege gesprochen’). With that, the story ends. Without more ado the prince orders Maid Maleen to be taken to a fine room, and the false bride’s head to be struck off. The patriarchy disposes. Maid Maleen herself says nothing. The Grimms do a lot more with this. First, before he actually recognises her, the prince acknowledges Maid Maleen as ‘the true bride who went with me to the church,’ confirming her as someone of great importance to him whoever she is. Only after that does he tentatively explore further: ‘On the way to the church you did name Maid Maleen, who was my betrothed bride; if I could believe it possible, I should think she was standing before me – you are like her in every respect.’ ‘You are like her in every respect.’ Following this proclamation of her worth, Maid Maleen finds her voice. Now she herself speaks out: at last comes the ‘seven long years I served for thee’ moment, the moment when, by restating her experiences, she reclaims her identity, a moment more poignant for the real suffering which has preceded it. There has been no assistance for this girl from the sun, moon and stars, no golden and silver dresses or magical gifts to barter with. No magic at all. ‘I am Maid Maleen, who for your sake was imprisoned seven years in the darkness, who suffered hunger and thirst, and has lived so long in want and poverty. Today, however, the sun is shining on me once more. I was married to you in the church, and I am your lawful wife.’ This fairy tale is a remarkable account of psychological trauma inflicted by suffering, all the more effective because of the other narratives with which it can be compared. There are many fairy tales in which a girl sets out to find a lost lover, but though her quest may be arduous she is always confident of her identity and what she is trying to achieve. When Maid Maleen escapes from her tower however, the empty landscape through which she wanders is her internal landscape, a waste land devoid of sustenance. There is nothing familiar in it, no one left who knows her, and she no longer knows herself. Physical survival is not enough. Unlike the heroines of other ‘lost bridegroom’ tales she is too unsure of herself to claim her lover and her place at his side.‘I am not the true bride.’ Not until at some deep level the prince recognises her does she recover her voice and, in telling her story, claiming her experiences and linking them together, reaffirms her identity and emerges from darkness. ‘Today the sun is shining on me once more.’ There can be little more to say. In true fairy-tale fashion the lovers live happily for the rest of their lives and the false bride has her head struck off. The story ends with a nursery rhyme which Müllenhoff places at the end of Jungfer Maleen – not as part of the tale, but as an interesting note or cross-reference. The Grimms, however, build the rhyme into the narrative so that it becomes a wonderfully evocative coda, distancing and mythologising Maid Maleen as she disappears from memory into children’s rhymes and games:

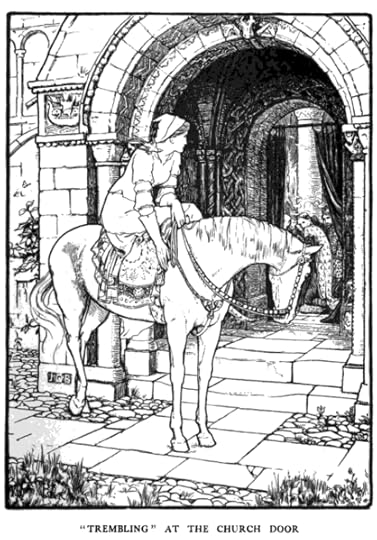

Maid Maleen - Arthur RackhamMaid Maleen - R. LeinweberThe False Bride Maleen - Edouard Manet via the website Wonderlit (I have been unable otherwise to source this)Irish Tower - Arthur Rackham

To round off my series of thirty fairytales which feature strong heroines, I'd like to repost an essay I wrote a couple of years ago about a fairy tale heroine whom many might not consider strong. For how can a girl who spends seven years imprisoned in a dark tower be an example of strength? Especially one who then seems to sink into a dark pit of post-traumatic depression? I argue that she is indeed an example of strength, and that our culture's focus on the kind of physical courage expressed in fighting and action leads us to forget or underestimate other forms of bravery. There isn't very much fighting in fairy tales! Often what they celebrate is the mental and spiritual courage all of us need to persist, endure, carry on in the face of pain, hardship, rejection, persecution. And this form of courage is often the courage of women. You can read Maid Maleen in full at this link, but I paraphrase it below. Though included in the Grimms' fairy tales (KHM 198), it's never been popular. It was first published as Jungfer MaleenSeven lang years I served for thee The glassy hill I clamb for theeThe bluidy shirt I wrang for theeAnd wilt thou no wauken and turn to me?

The time passed by, and by the decline of food and drink they knew that the seven years were coming to an end. They thought the moment of their deliverance was come; but no stroke of the hammer was heard, no stone fell out of the wall. All that prisoner-passivity and patience turns out to have been useless. The two women now seek actively to escape. They could have done so at any time before, but the weight of the king’s sentence, and their belief in it, lay upon them. Here Müllenhoff, emphasing the girls’ self-reliance, writes, ‘So they had to help themselves.’ (‘So mussten sie sich denn selber helfen.’) In the Grimms’ version Maid Maleen takes charge of their destiny but her words hint at the desperation she feels: ‘Maid Maleen said, “We must try our last chance, and see if we can break through the wall.”’ (‘Da sprach die Jungfrau Maleen: “Wir müssen das letzte versuchen und sehen, ob wir die Mauer dürchbrechen.”) Taking turns with a bread knife Maid Maleen and her maid scrape away the mortar between the stones and after three days of ‘great labour’ they push out a block and break through. Light rushes in. At last they can see the sky and breathe fresh air, but a new shock awaits: Her father’s castle lay in ruins, the town and villages were, so far as could be seen, destroyed by fire, the fields far and wide laid to waste, and no human being was visible.

At this point Müllenhof repeats the purposeful phrase, ‘So they had to help themselves.’ In the Grimms’ tale the crushing effect of the discovery is conveyed by a rhetorical question, ‘But where were they to go?’ (‘Aber wo wollten sie sich hinwenden?’) During their imprisonment the world has changed. Huge events have taken place, of which they in their isolation were completely unaware. How is a prisoner to adjust, adapt? New-born into this empty, post-apocalyptic land, their hard-won freedom brings no joy. They can only wander, starving, living on handfuls of nettles, till they cross the border into a country ruled by that very King whose son was Maid Maleen’s lover. And he is about to marry another woman. At this point in other ‘lost bridegroom’ tales there is a sense of great purpose: the girl’s arrival at the place where her lover resides is the pinnacle of her journey, and she is full of determination to win him back. By contrast Maid Maleen’s wanderings have been aimless. She’s not aspiring to find and marry her sweetheart, she’s simply trying to survive. Even when she finds work as a kitchenmaid in the palace and is employed in carrying meals to the chamber of the royal-bride-to-be, she seems stunned, passive, futureless. When forced under threat of death to impersonate the false bride, she suffers it as another indignity rather than seizing the opportunity to reveal herself to the prince. Nothing could be further from the confident resolve of the heroine of The Black Bull of Norroway, or the mutually beneficial alliance of the two brides in The Girl Clad in Mouse-Skin. Significantly at this point, as if to emphasise Maid Maleen’s degradation, her own maid disappears from the story. Maid Maleen is the servant now. And so on her way to the church, dressed as the princess she used to be and holding her true love’s hand, Maid Maleen sees a nettle growing by the wayside and it triggers a crisis. I once ate nettles raw. Can I really be Maid Maleen? Who am I? ‘Do you know Maid Maleen?’ the prince asks eagerly as she murmurs the name. And she denies it. ‘No, how should I know her? I have only heard of her.’ Is she testing him? Is this a secret reproach? I don’t think so. Maid Maleen has been a princess, a prisoner and a beggar. Her father forgot her. Her lover forgot her. The world forgot her. Now she is a kitchen-maid impersonating a princess, a pretender and cheat. ‘I am not the true bride,’ she repeats, afraid that the honest world will reject her, the foot-bridge break under her step, the church door split as she passes through. ‘I am not the true bride.’ In no other fairy tale I know of does this rejection of self occur. Maid Maleen is the true bride, but dispossessed, traumatised, damaged. There is a poignancy in her behaviour which I find deeply moving. The world has broken under her and she cannot trust it, cannot trust herself. Her loss of identity is such that she will do nothing to reinstate herself, will not speak another word. It is up to the prince to put the false bride to the test as, unable to answer his questions, she tacitly admits her deceit: I must go out unto my maid Who keeps my thoughts for me. Should we feel sorry for the ugly bride? That would be a very modern reaction. Fairy tales operate by particular rules. Youthful beauty almost always signifies goodness, ugliness its opposite: what you see is what you get. Nevertheless Heather Robbins, to whom I owe the translation of Jungfer Maleen, has made the interesting point that unlike, say, the troll bride of The Black Bull of Norroway, this particular false bride knows she is ugly, and that when she repeats Maid Maleen’s words to the prince, she is being forced to utter the truth about herself: ‘I am not the true bride’. Is it an elaborate trap? Can Maid Maleen be deliberately tricking her?

In another tale she might. It’s a ruse I can imagine Tatterhood (#15 in this series) or the Mastermaid (#7) or any number of other ingenious heroines might employ. It could even be true of Müllenhoff’s tale, but the Grimms’ story just doesn’t feel like that – at least to me. In The Girl Clad in Mouse-Skin, the mirror-opposite situation of the two brides works to their advantage. In Maid Maleen, the heroine and the false bride are so strikingly alike in their low self-esteem that on a psychological level the ugly false bride may even be Maid Maleen. In a powerful painting, False Bride Maleen, Edouard Manet makes manifest the darkness of the fairytale: the black fan guarding the face, the black dress, colour of death, the secrecy.

In another tale she might. It’s a ruse I can imagine Tatterhood (#15 in this series) or the Mastermaid (#7) or any number of other ingenious heroines might employ. It could even be true of Müllenhoff’s tale, but the Grimms’ story just doesn’t feel like that – at least to me. In The Girl Clad in Mouse-Skin, the mirror-opposite situation of the two brides works to their advantage. In Maid Maleen, the heroine and the false bride are so strikingly alike in their low self-esteem that on a psychological level the ugly false bride may even be Maid Maleen. In a powerful painting, False Bride Maleen, Edouard Manet makes manifest the darkness of the fairytale: the black fan guarding the face, the black dress, colour of death, the secrecy. The truth comes out. The prince wishes to see the mysterious maidservant. In a final effort the false bride sends her servants to kill Maid Maleen. This shock of sudden physical danger at last provokes a reaction: Maid Maleen screams so loudly that the prince rushes to her aid. Here the Grimms’ telling of the tale diverges significantly from that of Müllenhoff, in whose version the prince’s eyes are opened ‘and he saw that she was no other than his former beautiful true bride that he had quite forgotten, that Maid Maleen was the same woman she herself had spoken about on the way to church.’ (‘…und er sah, dass sie auch keine andre sei als seine ehemalige Braut, die er ganz vergessen hatte, das die Jungfer Maleen selber sei, von er sie immer auf dem Kirchwege gesprochen’). With that, the story ends. Without more ado the prince orders Maid Maleen to be taken to a fine room, and the false bride’s head to be struck off. The patriarchy disposes. Maid Maleen herself says nothing. The Grimms do a lot more with this. First, before he actually recognises her, the prince acknowledges Maid Maleen as ‘the true bride who went with me to the church,’ confirming her as someone of great importance to him whoever she is. Only after that does he tentatively explore further: ‘On the way to the church you did name Maid Maleen, who was my betrothed bride; if I could believe it possible, I should think she was standing before me – you are like her in every respect.’ ‘You are like her in every respect.’ Following this proclamation of her worth, Maid Maleen finds her voice. Now she herself speaks out: at last comes the ‘seven long years I served for thee’ moment, the moment when, by restating her experiences, she reclaims her identity, a moment more poignant for the real suffering which has preceded it. There has been no assistance for this girl from the sun, moon and stars, no golden and silver dresses or magical gifts to barter with. No magic at all. ‘I am Maid Maleen, who for your sake was imprisoned seven years in the darkness, who suffered hunger and thirst, and has lived so long in want and poverty. Today, however, the sun is shining on me once more. I was married to you in the church, and I am your lawful wife.’ This fairy tale is a remarkable account of psychological trauma inflicted by suffering, all the more effective because of the other narratives with which it can be compared. There are many fairy tales in which a girl sets out to find a lost lover, but though her quest may be arduous she is always confident of her identity and what she is trying to achieve. When Maid Maleen escapes from her tower however, the empty landscape through which she wanders is her internal landscape, a waste land devoid of sustenance. There is nothing familiar in it, no one left who knows her, and she no longer knows herself. Physical survival is not enough. Unlike the heroines of other ‘lost bridegroom’ tales she is too unsure of herself to claim her lover and her place at his side.‘I am not the true bride.’ Not until at some deep level the prince recognises her does she recover her voice and, in telling her story, claiming her experiences and linking them together, reaffirms her identity and emerges from darkness. ‘Today the sun is shining on me once more.’ There can be little more to say. In true fairy-tale fashion the lovers live happily for the rest of their lives and the false bride has her head struck off. The story ends with a nursery rhyme which Müllenhoff places at the end of Jungfer Maleen – not as part of the tale, but as an interesting note or cross-reference. The Grimms, however, build the rhyme into the narrative so that it becomes a wonderfully evocative coda, distancing and mythologising Maid Maleen as she disappears from memory into children’s rhymes and games:

Maid Maleen - Arthur RackhamMaid Maleen - R. LeinweberThe False Bride Maleen - Edouard Manet via the website Wonderlit (I have been unable otherwise to source this)Irish Tower - Arthur Rackham

Published on October 06, 2020 04:34

September 29, 2020

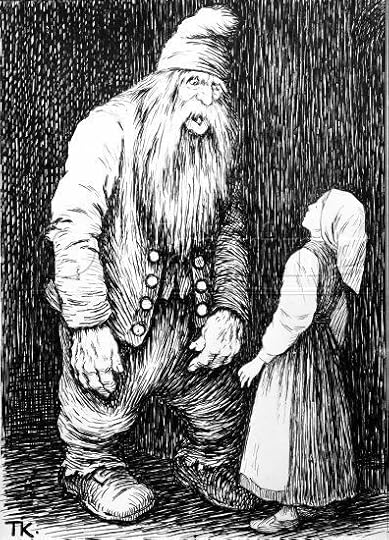

Strong Fairy Tale Heroines #30: VASILISA THE PRIEST'S DAUGHTER

This Russian tale from the collection of Aleksander Afanas’iev, translated by Norbert Guterman, brings my series of traditional fairy tales with strong heroines to a close. There are many Vasilisas in Russian fairy tales, and most of them are strong. In the well-known story of Vasilisa the Beautiful, for example, a young woman is sent to borrow fire from the witch Baba Yaga, while Vasilisa the Wise (#17 in this series) is a magic-worker who rescues the prince from her father the Sea King.

Vasilisa the Priest's Daughter works no magic of any kind. She simply uses wits and nerve to out-smart and rebuke an impertinently curious king. Her preferred way of life – dressing and behaving as a young man – is accepted by her father and raises no eyebrows among her neighbours, and she easily evades the efforts of the king – and the witch who advises him – to discover her real gender. I particularly like the trumphant note she sends him, at the end, where she compares him to a raven and herself to a falcon. That's telling him!

Those of you who've been following the series will remember similar attempts by the king and his pet lion in Grimms’ The Twelve Huntsmen #27 – and by a genie and his mother in the Romanian tale The Princess in Armour #3. (Don't you love the infinite variations on themes in fairy tales?) Naturally all such ingeniously contrived tricks are doomed to fail, and why? Because they rely upon crude and inadequate stereotypes of the character and capacities of women. This is a deliberate narrative choice: we are absolutely expected to enjoy seeing the heroines of these stories run rings around their often ridiculous male adversaries.

Still, the women of fairy tales have no real need to impersonate men, any more than the male heroes of fairy tales often resemble warriors with swords. Far more frequently, fairy tales celebrate humble protagonists, underdogs who succeed beyond their wildest dreams through chutzpah, kindness, endurance and luck. Girls and women in fairy tales are no less energetic, witty, clever, brave and persistent than the brothers and lovers they often rescue. In fact, they are often more so! My next post will examine one more story in close detail, before I move on to a different subject.

Witches!

In a certain land, in a certain kingdom, there was a priest called Vasily who had a daughter named Vasilisa Vasilyevna. She wore man’s clothes, rode horseback, was a good shot with a rifle and did everything in a quite unmaidenly way, so that only a very few people knew that she was a girl: most people thought she was a man and called her Vasily Vasilyevich, all the more so because she was very fond of vodka. This is, as is well known, entirely unbecoming to a maiden…

One day, King Barkhat – for the was the name of the king of the country – went hunting game and he met Vasilisa Vasilyevna. She was riding horseback in men’s clothes and was also hunting. When he saw her, King Barkhat asked his servants, ‘Who is that young man?’ One servant answered him, ‘Your majesty, that isn’t a man but a girl; I know for sure that she is Vasilisa Vasilyevna, the daughter of the priest Vasily.’

As soon as the king returned home he wrote a letter to the priest Vasily asking him to permit his son Vasily Vasilyevich to visit him and eat at the king’s table. Meanwhile, he himself went to the little old backyard witch and began questioning her as to how he could find out whether Vasily Vasilyevich was really a girl.

The little old witch said to him, ‘Hang up an embroidery frame on the right side of your chamber, and on the left side hang up a gun: if she is really Vasilisa Vasilyevna she will notice the embroidery frame first; if she is Vasily Vasilyevich she will notice the gun.’ The king followed the little old witch’s advice and ordered his servants to hang up an embroidery frame and a gun in his chamber.

As soon as the king’s letter reached Father Vasily and he showed it to his daughter, she went to the stable, saddled a grey horse with a grey mane, and went straight to King Barkhat’s palace. The king received her; she politely said her prayers, made the sign of the cross as is prescribed, bowed low to all four sides, graciously greeted King Barkhat, and entered the palace with him. They sat together and began to drink heady drinks and eat rich viands. After dinner, Vasilisa Vasilyevna walked with King Barkhat through the palace chambers; as soon as she saw the embroidery frame she began to reproach the king: ‘What kind of junk do you have here, King Barkhat? In my father’s house there is no trace of such womanish fiddle-faddle, but in King Barkhat’s house, womanish fiddle-faddle hangs in the chambers!’ Then she politely said farewell and rode home, and the king was none the wiser as to whether she was really a girl.

And so two days later – no more! – King Barkhat sent another letter to the priest Vasily, asking him to send his son Vasily Vasilyevich to the palace. As soon as Vasilisa Vasilyevna heard about this she went to the stable, saddled a grey horse with a grey mane, and rode straight to King Barkhat’s palace. She graciously greeted him, politely said her prayers to God, made the sign of the cross as is prescribed and bowed low to all four sides. King Barkhat had been advised by the little old backyard witch to order kasha cooked for supper, and to have it stuffed with pearls. The little old witch had told him that if the youth was really Vasilisa Vasilyevna, he would put the pearls in a pile, and if he was Vasily Vasilyevich, he would throw them under the table.

Supper time came. The king sat at table and placed Vasilisa Vasilyevna on his right hand, and they began to drink heady drinks and eat rich viands. Kasha was served after all the other dishes, and as soon as Vasilisa Vasilyevna took a spoonful of it and discovered a pearl, she flung it under the table together with the kasha and began to reproach King Barkhat. ‘What kind of trash do they put in your kasha?’ she said. ‘In my father’s house there is no trace of such womanish fiddle-faddle, yet in King Barkhat’s house, womanish fiddle-faddle is put in the food!’ Then she politely said farewell to King Barkhat and rode home. Again the king had not found out whether she was really a girl, though he badly wanted to know.

Two days later, upon the advice of the little old witch, King Barkhat ordered that his bath be heated; she had told him that if the youth really was Vasilisa Vasilyevna he would refuse to go to the bath with him. So the bath was heated.

Again King Barkhat wrote a letter to the priest Vasily, telling him to send his son Vasily Vasilyevich to the palace for a visit. As soon as Vasilisa Vasilyevna heard about it, she went to the stabel, saddled her grey horse with the grey mane, and galloped straight to King Barkhat’s palace. The king went out to receive her on the front porch. She greeted him civilly and entered the palace on a velvet rug; having come in, she politely said her prayers to God, made the sign of the corss as is prescribed, and bowed very low to all four sides. Then she sat at table with King Barkhat and began to drink heady drinks and eat rich viands.

After dinner the king said, ‘Would it not please you, Vasily Vasilyevich, to come with me to the bath?’

‘Certainly, your Majesty,’ Vasilisa Vasilyevna answered. ‘I have not had a bath for a long time and should like very much to steam myself.’ So they went together to the bathhouse. While King Barkhat undressed in the anteroom, she took her bath and left. So the king did not catch her in the bath either. Having left the bathhouse, Vasilisa Vasilyevna wrote a note to the king and ordered the servants to hand it to him when he came out. And this note ran:

‘Ah, King Barkhat, raven that you are, you could not surprise the falcon in the garden! For I am not Vasily Vasilyevich, but Vasilisa Vasilyevna.’ And so King Barkhat got nothing for his trouble, for Vasilisa Vasilyevna was a clever girl, and very pretty too!

Picture credits:As there seem to be no illustrations of this fairy tale, I have chosen to use 'A prince arrived' by John Bauer.

Published on September 29, 2020 02:15

September 22, 2020

Strong Fairy Tale Heroines #29: PRINCE HLINI AND SIGNY

This Icelandic tale was collected by Jón Árnason (1819 – 1888) whose six volumes of folk tales and fairy stories were edited and published in Reykjavik between 1954-61. The translation is from Icelandic Folk and Fairy Tales, selected and translated by May and Hallberg Hallmundsen, Iceland Review Library, 1987. In their introduction they comment that ‘every child in Iceland’ recognises ‘Jón Árnason’s Folktales’ – and no wonder, for they are robust and remarkable.

‘They are written,’ say the translators, ‘in the everyday spoken Icelandic of the time when they were recorded, many of them taken down word for word as told by the storytellers – farmers, laborers, housewives, maids. … The best way to render such narratives into English, we concluded, would be in plain unadorned prose that was faithful to the meaning if not to every word of the story. So, wherever the original text is bumpy or awkward – and it is in many places – we tried to smooth it over and we did not hesitate to reshape of switch sentences around if we thought it was inducive to a clearer understanding or a more straightforward narrative.’ I have taken the occasional similar liberty with their translation: for example, sometimes changing reported speech into dialogue.

This story needs almost no introduction: it speaks for itself – but I will say that Signý’s rescue of a prince from an enchanted sleep is an interesting role reversal of the Sleeping Beauty!

Once upon a time there was a king and a queen in their kingdom. His name was Hringur, but the queen’s name is not known. They had one son called Hlini. He was a promising lad who grew up to be a great champion, and the story has it that there was a crofter and his wife living near the palace grounds. They had a daughter named Signý.

One day the prince was out hunting with some of his men, and when they had felled a few animals and several birds and were preparing to go home, a fog descended upon them, so dense that the men lost sight of their prince. After searching in vain for a very long time they went back to the palace and told the king they had lost Hlini and couldn’t find him anywhere. This sad news greatly affected the king, and the next day he sent out a large party of men to look for his son. They searched until evening without finding him, and this went on for three days; Hlini was nowhere to be found. Sick with grief, the king took to his bed and let it be known throughout his land that whoever could find his son would be rewarded with half his kingdom.

When Signý heard of this, she told her parents about it, asked them for food and new shoes – which they gave her – and immediately set off. She walked for the better part of a day, and towards evening she came upon a cave. Entering it, she saw two beds, one embroidered with silver and the other with gold. When she drew closer, there was the prince lying asleep in the gold-embroidered one, and she tried to wake him but she couldn’t. Then she took a better look around her and saw that there were runes scored into the wooden heads of the beds, spelling out words she didn’t understand. So she went and hid herself in the nook behind the cave door.

No sooner was she hidden than she heard a great rumble and saw two very large-featured jötunns, or giantesses, coming. As they stepped into their cave, one of them said, ‘Fy, fo, there’s a smell of humans in here.’

‘It’s only Prince Hlini,’ said the other.

They went up to the bed where the prince was sleeping and said,

Sing, sing, my swans Sing Prince Hlini awake.

The swans sang, and Hlini woke up. The younger giantess asked him if he wanted something to eat, and he said no. Then she asked if he wanted to marry her, and he said no. Hearing that, she shouted out,

Sing, sing, my swans Sing Prince Hlini asleep.

They sang and he fell asleep. The two giantesses then took their clothes off and went to sleep in the silver-embroidered bed.

When they rose the following morning, they roused Hlini and offered him food, which he rejected. Then the younger one asked again if he would marry her. He said no, and with that they put him to sleep the same way as before, and left.

When she was sure they had gone, Signý crawled out ofher nook and said:

Sing, sing, my swans Sing Prince Hlini awake.

The prince woke up. He greeted her with joy and asked for the news and what was happening. She told him everything she knew and then asked what had happened to him. ‘After I was parted from my men in the mist,’ he said, ‘two giant women found me and brought me here, and one of them is trying to make me marry her.’

Signý said, ‘You should agree to marry her on condition that she tells you what the carved runes on the beds mean, and what the two of them get up to all day.’

The prince said he would do as she advised. Then he took a chessboard that was there, and asked Signý to play with him. They played until evening, but when dusk began to fall she told him to get back on the bed. Then she said:

Sing, sing, my swans Sing Prince Hlini asleep.

The prince fell asleep, and Signý hid herself back in her nook. Very soon afterwards, she heard the giantesses coming. They slouched into the cave, monstrous-looking as they were, and while the eldest one cooked a meal, the youngest went over to the bed, woke Hlini and asked if he would eat. This time he accepted. When he had finished his meal, the giantess asked if he would marry her. He replied that he would, provided that she tell him the meanings of the runes on the two beds. ‘Easily done,’ she said, and told him that they meant:

Glide, glide, my good bed, Wherever I want to go.

That was all fine, he said, but she would have to tell him one thing more – namely, what did the two of them do in the woods all day?

‘We go hunting for birds and animals,’ said the giantess, ‘and when we are resting we sit beneath an oak tree and toss our life-egg back and forth between us.’

Prince Hlini asked what would happen if it broke. That would never happen, the giantess told him, but if it did, they would both die. Hlini told her he was well pleased she had confided in him, but now, he said, he was tired and wanted to rest till morning.

‘As you wish,’ said the giantess.

Next morning she woke the prince for breakfast, which he accepted. Then she offered to let him come out into the woods with them, but he told her he preferred to stay home. So the giantess put him to sleep and left with her companion.

Once Signý was sure they had gone, she crept out of hiding to wake the prince. ‘Now let us go out into the woods where the giantesses are,’ she said. ‘Take your spear, and when they start tossing their egg, throw the spear at it and be sure not to miss, for your life depends on it!’

The prince agreed to this plan, and they stood together on the bed, saying:

Glide, glide, my good bed, Out into the woods.

The bed took off at once and didn’t stop until they reached a huge oak tree deep in the woods. There, Signý and Hlini heard roars of laughter. Signý told the prince to climb down into the branches. He did, and there below him he saw the two giantesses, one of them holding a golden egg in her hand. She tossed it to the other, and at the same time Hlini flung his spear. It struck the egg, breaking it, and the giantesses fell to the earth and died.

Then the prince climbed down from the oak, and he and Signý returned to the cave. They collected everything of value, loaded it on to the beds and flew straight to Signý’s cottage with all the treasure. The crofter and his wife welcomed the couple with joy, and Prince Hlini stayed at the cottage that night.

Early next morning, Signý went to the palace, stood before the king and hailed him. ‘Who are you?’ the king asked, and she told him she was just the crofter’s daughter from outside the grounds, and asked him what he would say if she brought back his son. The king replied that the question was not worth an answer, she would hardly be able to find his son, ‘since none of the men in my kingdom have been able to.’ Signý asked again whether he would reward her in the same way as he had promised the others, if she brought the prince home. The king said he would.

With that, Signý went back to the cottage and bid the prince come with her to the king’s palace, where she led him before his father. The king rejoiced to see his son, and asked what had happened to him since the time he was parted from his men. Sitting down on a throne, Hlini invited Signý to sit beside him, and told all his story just as I have done here. He added that he owed his life to Signý and he begged his father’s permission to marry her. The king gave his consent and a great feast was prepared. The wedding lasted a week, all the noblest people in the country were invited, and the prince and Signý loved each other long and well. So ends the story!

Picture credits:

Young man and misty woods ('The Hulder That Vanished') - by Theodor Kittelsen

Signý Enters the Trolls' Cave - Artist unknown

Troll wife cooking - by John Bauer

Published on September 22, 2020 01:41

September 15, 2020

Strong Fairy Tale Heroines #28: 'THE HEN IS TRIPPING IN THE MOUNTAIN'

'Will you be my sweetheart?'

'Will you be my sweetheart?'This story was collected by Jørgen Moe in Ringerike, eastern Norway, and published in Asbjørnsen & Moe’s Norske Folkeeventyr in 1852; it’s a good example of ATT Type 311, Rescue by the Sister. In this type of tale, three sisters set out on some adventure, the two eldest fail and the youngest rescues them: the Welsh Romany tale, The Three Sisters, #2 in this series is a striking and unusual example. In this kind of story princes do not feature, and there is rarely any wedding at the end.

The best-known example is probably the Grimms’ tale Fitcher’s Bird(KHM 46), a dark and curious tale which goes like this: a wizard kidnaps one of three sisters to be his wife, and like Bluebeard forbids her to open a particular door in his house. He also gives her an egg which she must carry about and keep with her. When the wizard is out, the girl looks into the forbidden room and finds a basin of blood and human body parts. She drops the egg and gets blood on it which she cannot remove. The wizard returns and kills her.

The same thing happens to the second sister; the third sister, however, is clever enough to put the egg safely away before looking into the forbidden room. There, finding her sisters dead and in pieces, she gathers the parts together and brings them back to life. The returning wizard believes he has been obeyed (seeing no sign of blood on the egg) and wants her for his bride. From now on he has no power over her.

She tells him to carry a basket of gold to her parents’ house as a dowry, but hides her sisters under the gold (feasibility has no place in fairy tales), ordering him not to rest or sit down on the way, for she will be watching him from the window. The wizard toils under the burden, but each time he tries to rest one of the sisters calls out. Certain that his betrothed is watching him, he carries the sisters and the gold to their home. Back at his house, the girl prepares a marriage feast and invites the wizard’s friends. She sets a skull in the window, wreaths it with bridal flowers, smears herself with honey and rolls in feathers till she looks like ‘a wondrous bird’, and sets off home. On the way she meets the arriving guests who greet her in rhyme as ‘Fitcher’s Bird’ coming from ‘Fitcher’s house’; the disguised girl tells them that all is ready and the bride is peeping from the window. As soon as the wizard and all his friends are in the house, her brothers and kinsmen arrive (warned by her sisters), barricade the doors and burn it down with the wizard and his crew inside.

The Hen Tripping in the Mountain is a lot more rustic and comical than Fitcher’s Bird, and the troll is so simple and stupid and cowardly that it’s hard not to feel a tiny bit sorry for him.

There was once an old woman who lived with her three daughters way up under a mountain ridge. She was so poor she owned nothing but a hen, the apple of her eye. It was always cackling at her heels and she was always running after it. Well one day, the hen vanished. The old woman went round and around the cottage searching and calling, but the hen was gone, and there was no finding it.

So the woman told her eldest daughter, ‘You’ll have to go out looking for our hen. We have to get it back – even if we have to dig it out of the the hill.’

The daughter went off looking and calling for it. She went all over, here and there, but no trace of the hen could she find, till just as she was about to give up, she heard someone calling from over by the cliffs,

Your hen is tripping in the mountain! Your hen is tripping in the mountain!

So she headed that way to see what it was, but right by the cliff foot she fell through a trap door, deep, deep down into an underground vault. At the bottom she made her way through many rooms, each finer than the first, but in the innermost room a big ugly mountain troll came up to her and said, ‘Will you be my sweetheart?’

‘No I won’t!’ she said, ‘not at any price!’ She wanted to get back above ground at once, and find her lost hen. Then the mountain troll was so angry he took her up and wrung off her head, and threw her head and her body down into the cellar.

While this was going on, her mother sat at home waiting and waiting, but no daughter came back. She waited a while longer, and then told her middle daughter to go our and call for her sister, and, she added, ‘you can call for our hen at the same time.’

So the second sister went out, and the same thing happened to her; she went about calling and looking, and she too heard a voice from the rock face saying,

Your hen is tripping in the mountain! Your hen is tripping in the mountain!

This was very strange, she thought, so she went to see what it could be, and she too fell through the trap door, deep, deep down into the vault. Then she went through all the rooms to the innermost one, where the mountain troll came up to her and asked if she would be his sweetheart? No, she would not! All she wanted was to get above ground again and look for her hen which was lost. So the troll got angry and wrung her head off, and threw head and body down into the cellar.

Well, when the old woman had sat and waited seven lengths and seven breadths for her second daughter, and no sign of her was to be seen or heard, she said to the youngest, ‘Now you really will have to go out after your sisters. It was bad enough to lose the hen, but it would be much worse to lose both your sisters, and you can always give the hen a call or two at the same time.’

Off went the youngest girl, and she went up and down hunting for her sisters, and calling the hen, but neither saw nor heard anything of any of them until at last shecame up to the cliff face and heard how something said:

Your hen is tripping in the mountain! Your hen is tripping in the mountain!

She too went to see what it was and fell down through the trap door, deep, deep down into the vault. When she reached the bottom she went from room to room, each one grander than the other, but she wasn’t at all scared and took good care to look around her, and she spotted the cellar door and looked through it and there were her sisters lying dead! And the moment she got the door shut, the mountain troll came up to her.

‘Will you be my sweetheart?’ he asked.

‘Yes, certainly!’ said she, for she could see quite well what had happened to her sisters. And when the troll heard that, he gave her the finest clothes in the world and anything else she asked for, he was so glad that anyone would be his sweetheart.

But after she’d been there for a while, there came a day when she was very downcast and silent. The troll asked why she was moping.

‘Oh,’ said the girl, ‘it’s because I can’t get home to my mother. She’ll be hungry and thirsty, I’m sure, and there’s no one to stay with her either.’

‘Well you can’t go to her,’ said the troll, ‘but put some food in a sack and I’ll carry it to her.’

Well she thanked him for this, and said she would. But she put lots of gold and silver at the bottom of the sack, and laid just a little food at the top, and gave the sack to the troll and told him not to look into it. The troll promised he wouldn’t, and set off, but the girl peeped after him through the trap door and saw that when he had gone just a little way, the sack was so heavy he put it down to untie the neck and look inside it. Then she called out,

I see what you’re up to!I see what you’re up to!

'I can still see you!'

'I can still see you!'‘Those are damn sharp eyes you’ve got in your head,’ said the troll, and he didn’t dare to try it any more.

When he reached the widow’s cottage he threw the sack in through the door. ‘Here’s some food from your daughter. She lacks for nothing!’ he said.

Now one day, when the girl had been in the hill for a good while longer, a billy goat fell down through the trap door. ‘Who said you could come in, you shaggy-bearded beast?’ said the troll in a fury, and he took the goat and wrung its head off and threw it into the cellar.

‘Oh! What did you do that for?’ said the girl. ‘I could have had that goat to play with; it’s dull enough down here.’

‘Well don’t sulk about it,’ said the troll. ‘I can soon bring it back to life, I can,’ and he took a flask which hung on the wall, put the goat’s head back on, smeared it with some ointment out of the flask, and up sprang the billy-goat as frisky as ever.

‘Oh ho,’ thought the girl, ‘that flask is worth something, it is!’ So she waited for a day when the troll was out, then took her eldest sister and put her head back on. She rubbed her with ointment from the flask, the way she’d seen the troll do to the billy-goat, and her sister came back to life at once. Then the girl stuffed her into a sack, covered her up with a layer of food, and said to the troll when he came back,

‘My dear friend, it’s time to take some food to my mother again. Poor thing, she must be hungry and thirsty, and with no one to look after her! But you mustn’t look in the sack.’

The troll was willing to take the sack, all right, but when he had got a bit on the way it was so heavy that that he thought he would see what was in it. ‘No matter how sharp her eyes are, she won’t see me from here,’ he thought. But as he set the sack down to look in it, the girl who was sitting inside called out,

I see what you’re up to!I see what you’re up to! ‘Those are damn sharp eyes you’ve got!’ said the troll, who thought it was the girl in the mountain who was calling. He didn’t dare try looking inside any more, but carried it to her mother’s house as fast as he could, and when he got there he threw the sack in through the door, bawling out, ‘Here’s meat and drink from your daughter! She has everything she wants!’

Well, the girl waited a while longer, and then she did the same thing with her other sister. She set her head back on her shoulders, smeared her with ointment and stuffed her into the sack along with as much gold and silver as would fit. Then she covered everything with a thin layer of food and asked the troll to take it to her mother. This time the sack was so heavy he could barely stagger along under it, so he put it down and was just going to untie the string and look in, when the girl inside shouted:

I see what you’re up to!I see what you’re up to!

‘The deuce you do!’ said the troll. ‘I never knew anyone with such damn sharp eyes!’ and he dared not take another peep, but staggered along to the old woman’s house, threw the sack in through the door and roared, ‘More food from your daughter! You see – she wants for nothing!’

A few days later when the troll was going out for the evening, the girl pretended to be poorly. ‘There’s no use you coming home any time before twelve midnight,’ she said. ‘I simply won’t be able to get supper ready till then, I’m feeling so sick and feeble.’ But when the troll had gone out, she stuffed some of her clothes with straw and stood this straw girl up in the corner by the hearth with a stirrer in her hand, so it looked as if she were standing there herself. After that she hurried off home and hired a hunter to come with her and stay with them in her mother’s cottage.

So when it was twelve midnight, the troll came home. ‘Bring me my food!’ he said to the straw maiden, but she didn’t move or answer.

‘Bring me my food, I say!’ said the troll again, ‘I’m starving!’ Still she didn’t answer.

‘Bring the food!’ yelled the troll. ‘Listen to what I say and do what you’re told, or I’ll give you such a wake-up, that I will!’ But the girl just stood there. Then he flew into a terrible rage and gave her such a kick that the straw flew up to the ceiling, and he saw he had been tricked. He searched high and low until he came to the cellar and found both the girl’s sisters were gone. Now he understood what had happened and ran down to the cottage crying, ‘I’ll pay her out for this!’ but when they saw him coming, the hunter fired. The shot banged out, and the troll mistook it for thunder. He turned in fright and ran for home as fast as his legs would carry him, but just as he reached his trap door, what do you think! – the sun rose, and he burst into pieces.

Oh, there’s plenty of gold and silver down under that trap door still – if we only knew how to find it!

Picture credits: Art by Theodor Kittelsen

Published on September 15, 2020 01:46

September 8, 2020

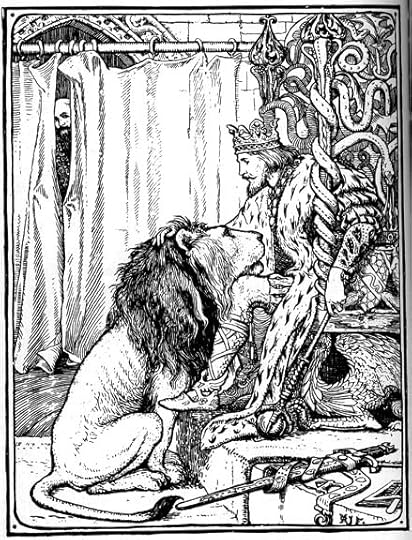

Strong Fairy Tale Heroines #27: THE TWELVE HUNTSMEN

If we approach fairy tales expecting nothing but sexist stereotypes, we will miss the irony, the inflections; we won’t get the jokes. In this tale of the Brothers Grimm, a princess dresses herself and eleven ladies-in-waiting as huntsmen and goes to work for her lover, a king who has promised his dying father to marry a different woman.

This king has a talking lion. (As you do.) The lion suspects the twelve young huntsmen of being women. He sets traps to get them to betray themselves – such as an array of twelve spinning wheels which he assures the king these ‘women’ will be unable to resist. You have to imagine this story being told aloud in mixed company, at a time when spinning was a woman’s repetitive, endless work. It’s as if, in a modern version, the lion had set out a line of twelve vacuum cleaners! Readers who take it at face value are missing the comedy of the princess’s satirical aside to her followers as they stride past: ‘Hold back, girls, don’t give those spinning wheels a glance…’

It is all too easy to misinterpret a tale when it’s pinned to the page like a dead butterfly – still more so when the original transcript is over two centuries old and even the English translation was made over 130 years ago. The classic translation of the Grimms’ tales into English is the one by Margaret Hunt (published 1884), whose clear, unadorned style now unavoidably feels somewhat stiff. I’ve stuck quite closely to her version for this post, I didn’t want to change it much; but I have loosened it up a little. It’s best to regard ‘the story on the page’ in much the same way as we regard sheet-music: it requires performance – the voice of the story-teller – to bring it to multi-dimensional life. But the information on the page still has to be examined and respected. Like some others in the Grimms’ collection, The Twelve Huntsmen directs sly, subversive humour at male assumptions about female ability, and if we fail to notice when a story is inviting us to laugh, it’s we who are naïve.

Once upon a time, a king’s son was betrothed to a woman he loved very much. One day when they were sitting together, and very happy, news came that the prince’s father lay on his deathbed and wanted to see his son once more before the end. So the prince said to his beloved, ‘Though I have to leave you, I give you this ring to remember me by, and when I am king I will return for you.’

Away he rode, but when he came to his father’s bedside the old man was desperately ill and near death. ‘My dear son,’ said he, ‘now that I see you, promise me that you will marry as I advise,’ and he named another king’s daughter to be his bride. The son was too distraught to think what he was doing and said, ‘Yes dear father, yes, whatever you wish shall be done.’ On hearing these words the old king closed his eyes and died.

So after the son had been proclaimed king and the period of mourning was over, he felt compelled to keep the promise he had made to his father, and he sent for permission to court the other king’s daughter’s, and permission was granted. When his lover heard of this she was so unhappy she nearly died. Her father said to her, ‘Dear child, what makes you so sad? Tell me what you want; anything in my power to grant shall be yours.’ The young woman thought for a moment and said, ‘My dear father, I wish for eleven girls just like myself in face, figure and height.’ So her father searched throughout his kingdom until eleven young women were found who were just like his daughter in face, figure and height.

When they were assembled, the king’s daughter had twelve suits of huntsmen’s clothes made, all alike, and she and the eleven girls put them on and rode away together to the court of her former lover, where she asked if he would take twelve fine huntsmen into his service. The king did not recognise her, but the huntsmen were all such handsome fellows he said, yes, willingly he would hire them! And so they became the king’s royal huntsmen.

Now the king had a lion, and this lion knew everything. Nothing could be kept from him, and one evening he said to the king, ‘You think you have twelve huntsmen?’

‘Of course I have twelve huntsmen!’

‘You are wrong,’ said the lion, ‘they are twelve girls.’

The king couldn’t believe this, so the lion told him to throw handfuls of dried peas over the floor of the antechamber: ‘And then you’ll see! Men tread firmly, so the peas won’t move when they step on them, but girls trip and skip and slide their feet, and the peas will roll in all directions.’ The king liked this idea, so he ordered the peas to be thrown on the floor.

But one of the king’s servants who was friendly with the huntsmen had overheard what the lion said, so he ran to them with the news. ‘The lion wants to make the king think you are girls!’ The king’s daughter thanked him. When he had gone she said to her women, ‘Time to show your strength, girls! Make sure you tread firmly on those peas!’ And next morning when the king called the twelve huntsmen before him, they walked into the antechamber with such a strong, sure tread that not a single pea rolled or even shifted.

After they had left, the king turned on the lion: ‘What you told me was false! They walk just like men.’ The lion replied, ‘They were pretending. Someone must have warned them! But here’s an idea: bring twelve spinning wheels into the antechamber. Then you’ll see! They’ll be so thrilled they won’t be able to resist going over and examining them. No man would do that!’ This advice pleased the king, and he had the spinning wheels placed in the antechamber.

But the servant who was friendly to the huntsmen told them about this plan too. ‘Hang on to yourselves, girls!’ said the king’s daughter to her eleven women. ‘Don’t give those spinning wheels a glance!’ So when the king summoned them, the twelve huntsmen strode through the antechamber without so much as turning their heads to look at the spinning wheels. And the king said to the lion, ‘You’ve been proved false again. They’re men! They showed no interest in the spinning wheels.’

‘They knew we were trying to trick them,’ said the lion, ‘that’s why they restrained themselves.’ But the king no longer trusted the lion’s opinions. The twelve huntsmen became his companions whenever he went out hunting, and he valued them more and more.

One day as they were out riding in the forest, news came that the king’s new bride-to-be was approaching with her retinue. When his true lover heard this, her heart hurt so much she fell fainting to the ground. Seeing the accident that had befallen his dear huntsman, the king ran to help him, grasped his hand and drew off the glove that covered it. Then he saw the ring he had given his first beloved, and looking again in her face, he recognised her. His heart was so touched that he kissed her, and said as she opened her eyes, ‘You are mine and I am yours, and no one in the world can change that.’ He sent a messenger to the other bride, begging her to return to her own kingdom, for he had a wife already and someone who has found an old key doesn’t need a new one. So their wedding was celebrated, and the lion was vindicated and taken back into favour – for after all, he had got one thing right.

Picture credits: The Twelve Huntsmen by HJ Ford, illustration from The Green Fairy Book.

Picture credits: The Twelve Huntsmen by HJ Ford, illustration from The Green Fairy Book.

Published on September 08, 2020 02:24

August 27, 2020

Strong Fairy Tale Heroines #26: KATE CRACKERNUTS

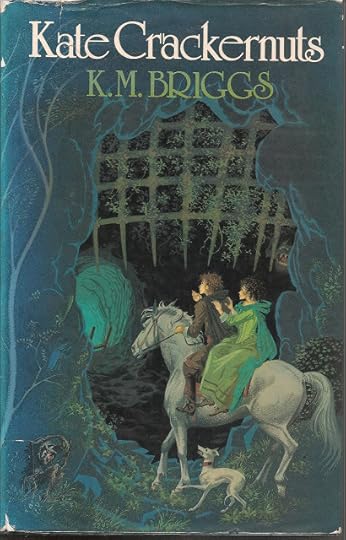

Kate Crackernuts is the same story type as the Norwegian Tatterhood (#15 in this series) in which two sisters or stepsisters stick together through thick and thin, and the plain or ugly sister rescues the pretty one from a witch’s spell and manages things so that in the end they both marry princes (whether the prince wants to or not). Kate Crackernuts in this tale rescues her prince as well.

The story was first collected by Duncan J Robertson (1860-1941) – poet, naturalist, County Clerk of Orkney for over 50 years and some time owner of Eynhallow, a small and now deserted island in Eynhallow Sound between Rousay and Mainland Orkney. (The island is said to have been first inhabited by the Finfolk or mer-people, who were driven out bythe first human settler, the Goodman of Thorodale.)

Anyway, Robertson published Kate Crackernuts in Longmans Magazine, vol xiii (1888/9). I wasn't able to consult this version, since the only online edition is unavailable to anyone outside the United States. But Andrew Lang republished the story in Folklore, Sept. 1890 (vol 1, no. iii) and it’s probably safe to assume he made few if any changes, since the narrative is quite fragmented. It keeps dropping in and out of a Scots, not Orcadian dialect – which suggests to me that it may not in fact have been collected on Orkney – and various chunks of the story are told in a rather stilted summary. For example: ‘In consequence, the answer at the henwife’s house was the same as on the preceding day’, or ‘A magnificent hall is entered, brightly lighted up, and many beautiful ladies surround the prince,’ etc. To make it flow and be enjoyable to read or listen to, it absolutely has to be expanded and partly rewritten. This I have done – and Joseph Jacobs did so too when he included it in his famous (somewhat misnamed) English Fairy Tales of 1890. He complained that the tale was ‘very corrupt, both of the girls being called Kate’, and renamed one of them Anne, doubtless to prevent child readers getting muddled. I don’t personally think this was necessary, and I believe the two Kates are likely to be authentic and not a mistake at all.

Katharine Briggs seems to have agreed, for she kept the two Kates in her lovely 1963 novel Kate Crackernuts in which she gives the fairy tale a local habitation and a date in 17th century Scotland at Auchenskeoch, Dumfries and Galloway, near the Solway Firth. And in her lightly rewritten version of the fairy tale in the 1976 Dictionary of Fairies, she calls the girls ‘the King’s Kate and the Queen’s Kate’, but follows Joseph Jacobs in making the all-night fairy dancing the cause of the prince’s illness. The Robertson/Lang version says nothing about this at all, but it makes good narrative sense.

Food is important in the story. Just a mouthful of bread or a handful of peas can protect the king’s Kate from her minnie’s (stepmother’s) wiles and the henwife’s spells. Bread was often blessed by having a cross cut into it, and perhaps the peas are given to her with a blessing, too? Then of course there are the nuts – probably hazel nuts – which Kate not only eats herself but uses as a medium of exchange for the fairy wand and bird. In Celtic legend the hazel is the tree of knowledge or divination, which may be why hazel rods are still used by water diviners. Hazel trees with crimson nuts were believed to grow around the pools at the source of Irish rivers. The nuts which fell into the water fed the Salmon of Knowledge, and anyone who ate the flesh of the salmon would in their turn become wise.

One sleepy afternoon two years ago I visited the deep, peaty pool at the source of the Shannon. The steep banks were sprinkled with flowers: gnats and mayflies rose and sank in the air, and although the trees leaning over it and dropping the occasional lazy leaf were willows, I could well imagine the Salmon of Knowledge swimming unseen in the brown water.

I wonder if Kate’s handful of hazel nuts brought her the wisdom and luck to succeed?

Once upon a time there was a king and a queen, as in many lands have been. The king had a daughter, Kate, and the queen had one too, but the king’s Kate was bonnier than the queen’s Kate, and the queen was jealous of her and cast about for a way to spoil her beauty. So she took counsel of the henwife, and the henwife told her to ‘send the lassie to me in the morn, fasting.’

So on the next morn, the queen sent the king’s Kate down to the henwife for eggs, but the lassie was hungry and snatched up a piece of bread before she went out. When she came to the henwife’s, she asked for the eggs as she’d been told to, and the henwife told her to ‘lift the lid of the pot there, and see.’ Well the lassie lifted the lid and up rose the steam, but nothing happened for all that. ‘Gae hame to your minnie, and tell her to keep her larder door better steekit,’ said the henwife. Then the queen knew that the lassie had had something to eat. Next morning she watched her, and sent her out fasting, but as the lassie went to the henwife’s she saw some country folk picking peas by the roadside, and spoke to them, and they gave her a handful of the peas which she ate by the way. So once again when she lifted the lid of the pot and the steam rose, no harm came to her, and the henwife said, ‘Tell your minnie the pot winna boil if there’s nae fire under it.’

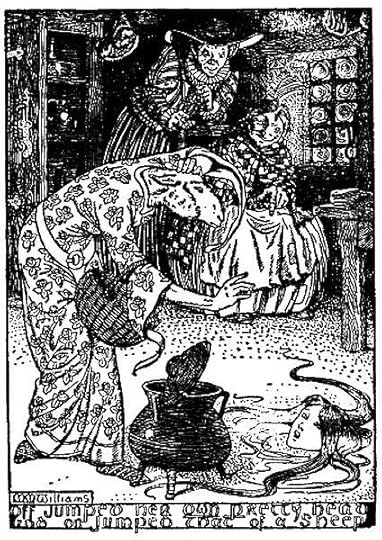

On the third day, the queen takes the king’s Kate by the hand and herself leads her to the henwife. And now when the lassie lifts the lid of the pot and the steam rises, why, off jumps the princess’s ain bonnie head, and on jumps a sheep’s head!