Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 13

May 19, 2020

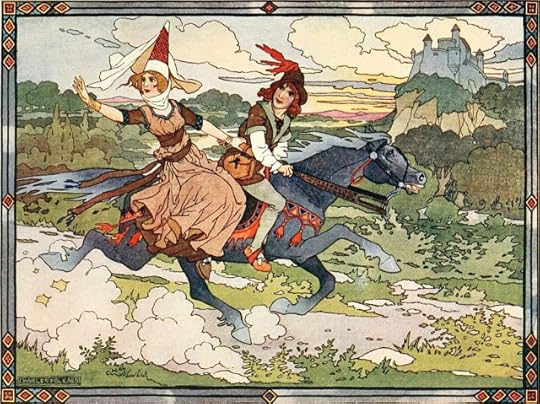

Strong Fairy Tale Heroines #13: THE NETTLE SPINNER

THE NETTLE SPINNER

Another dark fairy tale: this is a Flemish story, 'La Fileuse d’Orties', from ‘Contes du roi Cambrinus’ (1872) collected by Charles Deulin. The English translation was made by Leonora Blanche Alleyne (Mrs Andrew Lang) for ‘The Red Fairy Book’, and it's a strange, sinister story which takes the old theme of the girl who weaves nettle shirts, and stands it on its head. You'll remember tales such as Hans Andersen's 'The Wild Swans' and the Grimms’ ‘The Twelve Brothers’ in which the heroine spins and weaves nettle shirts to disenchant the brothers she loves. (A similar healing magic is performed by 'Gilla of the Enchantments': #6 in this series.) But when the heroine of this story tells a wicked count that she prefers marrying her sweetheart to succumbing to his wiles, the count effectively responds, ‘Over my dead body!’ and orders her to perform what he assumes will be the impossible tasks of weaving a nettle wedding-gown for herself, and for himself, a nettle shroud. Of course it isn't impossible, and as she steadily spins the nettles and weaves the shroud, he begins to sicken…

Renelde is one of those strong, long-persisting heroines who keep their eyes firmly fixed on what they've decided is right. You'll note that while the women in this story are active agents, the men are ultimately ineffectual. Neither the count nor Renelde's fiance Guilbert can persuade her to act differently from her principles. Her behaviour is so consistent and so quietly inexorable that one almost begins to feel sympathy for the wicked count.

Almost. Not quite.

I

Once upon a time there lived at Quesnoy in Flanders a great lord whose name was Burchard, but whom the country people called Burchard the Wolf. Now Burchard had such a wicked, cruel heart that it was whispered he used to harness his peasants to the plough and force them by blows from a whip to till his land with naked feet.

His wife, on the other hand, was always tender and pitiful to the poor and miserable. Every time she heard of another of his misdeeds, she would secretly go to repair the evil, so that she was blessed throughout the whole countryside. This countess was loved as much as the count was hated.

II

One day when he was out hunting the count passed through a forest and at the door of a lonely cottage he saw a beautiful girl spinning hemp. “What is your name?” he asked. “Renelde, my lord.” “Aren’t you tired of living in such a lonely place?” “I’m used to it my lord, and I never get tired of it.” “If you come to the castle, I’ll make you a lady’s maid to the countess.” “I can’t do that, my lord. I have to take care of my grandmother, who is very helpless.”

“Come to the castle, I tell you. Be there this evening,” and he went on his way. But Renelde knew very well not to trust him, and she was betrothed to a young woodcutter called Guilbert, and besides, she did have her grandmother to look after.

Three days later the count rode by again. “Why didn’t you come?” he asked the pretty spinner.

“I told you, my lord, I have to look after my grandmother.”

“Come tomorrow and I will make you lady-in-waiting to the countess,” and he went on his way. But his offer had no more effect than the last, and Renelde did not go to the castle. “If you will just come,” said the count, the next time he rode by, “I will put the countess aside and marry you.” But two years before when Renelde’s mother was dying of a long illness, the countess had helped them and been very kind to them, so even if the count had really meant to marry Renelde, she would still have refused.

III

A few weeks passed, and Renelde hoped she had got rid of him, but one day the count stopped at the door, his duck-gun under one arm and his game-bag on his shoulder. This time Renelde was spinning not hemp, but flax.

“What’s that you’re spinning?” he asked roughly. “My wedding shift, my lord.” “You’re going to be married, are you?” “Yes my lord, by your leave.” For at that time no peasant could marry without his master’s permission.

“I will give you leave on one condition. Do you see those tall nettles that grow on the graves in the churchyard? Go and gather them, and spin them into two fine shifts. One shall be your bridal gown, and the other shall be my shroud, for you shall be married the day I am laid in my grave.” And with a mocking laugh, the count turned away.

Renelde trembled. No one in all Locquignol had heard of such a thing as spinning nettles. And besides, the count seemed made of iron and was very proud of his strength, often boasting that he should live to be a hundred.

Every evening when his work was done, Guilbert came to visit his bride-to-be; this evening he came as usual, and Renelde told him what Burchard had said.

“Shall I watch for the Wolf and split his skull with a blow of my axe?”

“No!” Renelde answered, “there must be no blood upon our bridal. And – we must not hurt the count. Remember how good the countess was to my mother.”

An old, old woman now spoke up, she was the mother of Renelde’s grandmother, and was more than ninety years old. All day long she sat in her chair nodding her head and never saying a word. “My children,” she said now, “in all the years I have lived, I have never heard of a shift spun from nettles. But what God demands of us, we will have the strength to do. Why shouldn’t Renelde try it?”

IV

Renelde did, and to her great surprise found the nettles, crushed and prepared, gave a good thread, supple and light and firm. Quite soon she had finished the first shift, which was for her wedding. She wove it and cut it out at once, hoping the count would not force her to begin the other. Just as she finished sewing it, Burchard the Wolf passed by.

“Well,” said he, “how are the shifts getting on?”

“Here is my wedding gown, my lord, “ Renelde answered, holding up the shift, which was the whitest and finest ever seen. The count went pale, but he replied roughly, “Very good. Now begin the other.”

The spinner set to work. As the count returned to the castle a cold shiver passed over him; he felt, as the saying goes, that someone had walked over his grave. He tried to eat his supper but could not; he went to bed shaking with fever. He did not sleep, and in the morning he could not rise.

Such a sudden illness, which was becoming worse, made him very uneasy. He was sure Renelde’s spinning wheel was doing it. Was it necessay that his body, as well as his shroud, should be ready for burial? So Burchard sent a message to Renelde to stop spinning and put away her wheel. She obeyed, but that evening Guilbert asked her, “Has the count agreed to our marriage?”

“No,” said Renelde. “Continue your work, sweetheart. It’s the only way of gaining his consent. He told you so himself."

V

Next morning, the girl sat down to spin. Two hours later, two soldiers arrived and when they saw her spinning they seized her, tied her arms and legs and carried her to the river, which was swollen with rain. They flung her in like a dog and left her to drown. But Renelde rose to the surface, her bonds fell away and she struggled to land.

As soon as she got home she sat down and began to spin.

Again the soldiers came to the cottage and seized her. They carried her to the river, tied a stone around her neck and threw her into the water. But the moment their backs were turned the stone untied itself. Renelde waded to the ford, returned to the hut and sat down to spin.

Now the count resolved to go to Locquignol himself, but he was so weak he had to be carried in a littler. And still the spinner spun. As soon as he saw her he fired a shot at her, but the bullet rebounded without hurting her – and still she spun on.

Burchard fell into such a rage it almost killed him. He smashed the spinning wheel into a thousand pieces and fell to the ground in a faint. He was carried back to the castle unconscious, but the next day the spinning wheel was mended and the spinner sat down to spin. The count ordered her hands to be tied, but the cords fell away. He ordered every nettle to be uprooted for miles around, but no sooner had they been torn from the soil than they grew again thicker than before, and they even grew up through the cottage floor and sprang to the distaff ready for spinning.

And every day Burchard the Wolf grew worse and watched his end approaching.

VI

Moved by pity for her husband, the countess at last found out the cause of his illness, and begged him to consent to Renelde’s marriage. But the count in his pride refused more than ever to do so.

So without his knowledge the lady went herself to pray for mercy from the spinner, and in the name of the girl’s dead mother she begged her to spin no more. Renelde gave her promise, but in the evening Guilbert arrived at the cottage, and seeing no progress in the cloth from the day before, he asked the reason. Renelde confessed that the countess had pleaded for her husband’s life.

“Has he agreed to our marriage?” “No.” “Let him die, then. The countess will understand that it is not your fault. The count alone is guilty of his own death.” “Let us wait a little. Perhaps his heart may soften.”

They waited for one month, for two, for six, a year. The spinner spun no more. The count had ceased to persecute her, but still he refused his consent to the marriage. Guilbert became impatient. “Let us have done with it!” he cried.

“Wait a little still,” pleaded Renelde, but the young man grew weary. He came more rarely to Locquignol, and then he did not come at all. News came that he had left the country. Renelde felt her heart would break, but she held firm and another year went by.

VII

Then the count became more ill. The countess thought Renelde, tired of waiting, ahd begun her spinning again, but when she came to the cottage to find out, the wheel stood silent in the corner.

But the count grew worse and worse. The doctors had given him up, the passing bell was rung and he lay expecting Death to come for him. But Death was not so near as the doctors thought, and still he lingered, getting neither better nor worse. He could neither live nor die; he suffered horribly and called aloud on Death to put an end to his pains.

In this extremity he remembered what he had said to the little spinner long ago. If Death was so slow in coming it was because he was not ready to follow him, having nor shroud for his burial.

He sent for Renelde, placed her by his bedside and ordered her at once to go on spinning his shroud, and as soon as she began the count felt his pain begin to lessen. At last his heart melted and he was sorry for all the evil he had done in his pride, and he begged Renelde to forgive him. So she forgave him, and went on spinning night and day.

When the thread was all spun she wove it with her shuttle, and then she cut the shroud and began to sew it. And as she sewed the count felt the life sinking within him, and when the needle made the last stitch he gave his last breath. VIII

At that same hour Guilbert returned to the country. He had never stopped loving Renelde, and eight days later they were married. He had lost two years of happiness, but comforted himself by thinking that his wife was a clever spinner – and what was far better, a brave and good woman.

More on fairy tales and folklore in "Seven Miles of Steel Thistles" available here and here.

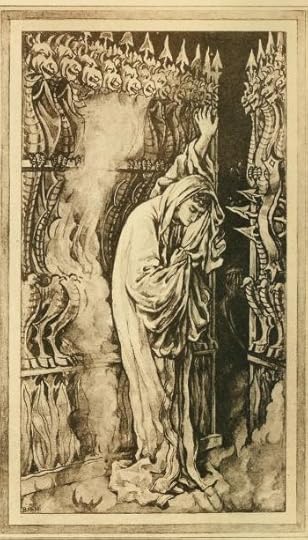

Picture credits:Illustrations to The Nettle Spinner by HJ Fordfor The Red Fairy Book

Published on May 19, 2020 03:14

May 12, 2020

Strong Fairytale Heroines #12: THE WOMAN WHO WENT TO HELL

The next three fairy tales in the series take a darker turn. This story of a young woman who goes down into the underworld to save her lover was narrated in Gaelic some time around 1885 by Patrick Minahan, of Malinmore, Glencolumkill, Co. Donegal, to William Larminie who translated and published it in ‘West Irish Folk-Tales’, (Camden Library, 1893). Larminie - one of those excellent 19th century collectors who named and respected their oral sources - says of Minahan: “I obtained more stories from him than from any other one man. He said he was eighty years old; but he was in full possession of all his faculties. He also had a holding on which he still worked industriously. … His style, with its short, abrupt sentences, is always remarkable, and at its best I think excellent.”

Of the tale itself, Larminie has only this to say, but it’s to the point: “This touching tale has a curious far-away resemblance to certain classical legends. A good deal must [have been] lost, and in consequence the long struggle of the young man with the devil has much that requires explanation. It is unique among Celtic stories.”

I can’t be sure what classical stories Larminie had in mind – Persephone’s sojourn in Hades, perhaps, for it’s not really the young man’s struggle so much as that of the young woman who becomes his wife! Myself, I'd like to note that the restorative fire in which the dead man asks the young woman to burn him to ashes reminds me of the fire of roses in George Macdonald's 'The Princess and Curdie' – and that her return home, worn and almost unrecognisable, reminds me of the return of Homer's Odysseus.

The story begins when the devil tricks a woman into promising him her 'burden', which she assumes means the cabbages she is carrying. In fact it is her unborn son. The boy is born, grows up and dies suddenly aged 18. When a young woman enters the chapel where his body lies coffined, the dead young man arises and persuades her to help him. By burning his corpse she restores him to a kind of spirit life, and he sires a son on her. But the devil claims him - unless someone else will go to Hell in his place. His lover volunteers.

The young woman's descent into Hell and her subsequent ascent reminds me of a story older even than Homer's - that of Inanna of Sumer, Queen of Heaven and Earth, the goddess of love and of the morning and evening star, whose descent to the realm of Ereshkigal Queen of the Dead is chronicled on clay tablets dating back to 2000 BCE.

In summary, it goes like this: Inanna abandons her temples and palaces in heaven and earth and goes down to the underworld. Her journey seems to be a rite of passage rather than an attempt to rescue a friend or lover such as those of Gilgamesh and Orpheus. In order to pass through the underworld’s seven gates she must relinquish at each one a part of her 'mes' (roughly her power), signified by regalia of crown, beads, robe, ring, breastplate, measuring rod and line. At last, naked and powerless she enters the throne room of Ereshkigal where the goddess strikes her dead and hangs her body – now nothing but ‘a piece of rotting meat’ – from a stake. But, following Inanna’s previous orders, her faithful servant Ninshibur persuades Enki, god of wisdom, to save her. He creates two sexless creatures from the dirt under his fingernails, furnishes them with the food and water of life, and sends them to the underworld to ask for Inanna’s corpse. Sprinkling the corpse with the food and water, the creatures restore it to life, but the judges of the underworld decree another must take her place. As Inanna ascends, the 'galla' or small demons of the underworld cling to her side and rise with her. They ‘know not food, they know not water, they know not sprinkled flour,’ but their purpose is to seize and bring back the one who will die for her. Her loving servant Ninshibur and her own sons offer themselves, but Inanna refuses to give them up. She chooses instead her husband Dumuzi, who has not even risen from his throne to welcome her home! Dumuzi is taken to the underworld. After his death, Inanna weeps for him, and later in the tale she allows his faithful sister to take his place for six months of every year.

This myth has cast a long shadow. Sumerian Inanna and Dumuzi became the Akkadian Ishtar and Tammuz, and the Egyptian goddess Isis perhaps shares some of Inanna’s attributes. It predates the Greek myth of Persephone and Hades, first noted in Hesiod's Theogony, by one and a half millennia. Now, obviously there can't be any direct connection, but I feel there’s still a faint trace of it in this Irish story – in the young woman’s voluntary descent, and in the touching moment when the lost souls cling to her, clotted in her hair.

There was a woman coming out of her garden with an apron-full of cabbage. A man met her. He asked her what she would take for her burden. She said it was not worth a great deal, she would give it to him for nothing. He said he would not take it, but would buy it. She said she would only take sixpence. He gave her the sixpence, and she threw the cabbage towards him. He said that was not what he had bought, but the burden she was carrying. Who was there but the devil? She was troubled then.

She went home and she was weeping. It was a short time till her young son was born, and he was growing till he was eighteen years old. Then he was out one day and fell, and never rose up till he died. When they were going to bury him, they took him to the chapel and left him there till morning.

There was a man among the neighbours who had three daughters. He took out a box of snuff to give the men a pinch, and the last man to whom the box went round left it on the altar. They all went home, and when the man was going to bed he looked for his box. The box was not to be got; it was left behind in the chapel. He said he could not sleep that night without a pinch of snuff. He asked one of his daughters to go to the chapel and bring him the box that was on the altar. She said there was loneliness on her. He cried to the second girl, would she go? She said she would not go, that she was lonely. He cried to the third, would she go? And she said she would go, that there would be no loneliness on her in the presence of the dead.

She went to the chapel, she found the box, she put it in her pocket. When she was coming away she saw a ring at the end of the coffin. She caught hold of it till it came to her. The end came from the coffin. The man that was dead came out. He begged her not to be afraid.

“Do you see that fire over yonder? If you are able, carry me to that fire.” “I am not able,” said she. “Be dragging me along with you as well as you can.”

She put him on her back. She dragged him till they came to the fire. “Draw out the fire,” said he, “and put me lying in the middle of it; fix up the fire over me. Anything of me that is not burnt, put the fire on it again.”

He was burning till he was all burnt. When the day was coming she was troubled on account of what she had seen in the night, and when the day grew clear there came a young man, who began making fun with her.

“I have not much mind for fun on account of what I have seen during the night.” “Well, it was I who was there,” said the young man. “I would go to heaven if I could get an angel made by you left in my father’s room.”

Three quarters of a year from that night she dressed herself up as if she was a poor woman. She went to his father’s house, and asked for lodging till morning. The woman of the house [the young man's mother] said that they were not giving lodging to any poor person at all.

She said she would not ask for more than a seat by the fire. The man of the house told her to stay till morning. They both went to lie down. She sat by the fire. In the course of the night she went into the room and there she had a young son. Her husband came in at the window in the shape of a white dove. He dressed the child, the child began to cry, and the woman of the house heard the crying. She rose to get out of her bed. Her husband told her to lie quiet and have patience. She got up in spite of him. The door of the room was shut. She looked in through the keyhole and saw him standing on the floor; she perceived it was her son who was there. She cried to him, was it he that was there? He said it was.

“One glance of your eye has sent me for seven years to hell.”“I will go myself in your place,” said his mother.

She went then to hell. When she came to the gate, there came out steam so hot that she was burned and scalded, and had to return. “Well,” said the father, “I will go in your place.” He had to return too. The young man began to weep. He said he must go himself, but the mother of the child said she would go.

“Here is a ring for you,” said he. “When thirst comes on you, or hunger, put the ring in your mouth; you will feel neither thirst nor hunger. This is the work that will be on you – to keep down the souls: they are stewing and burning in the boiler. Do not eat a bit of food there. There is a barrel in the corner, and all the food that you are given, throw into the barrel.”

She went to hell then. She was keeping down the souls in the boiler. They were rising in leaps out of it. All the food she got she threw on the barrel till the seven years were over. She was making ready to be going then. The devil came to her; he said she could not go yet awhile till she had paid for the food she had eaten. She said she had not eaten one morsel of his: “All that I got, it is in the barrel.” The devil went to the barrel, and all that he had given her was there for him.

“How much will you take to stay seven years more?”“Oh, I am long enough with you,” said she; “if you give me all that I can carry, I can stay with you.”

He said he would give it. She stopped. She was keeping down the souls during seven more years, she was shortening the time as well as she could till the seven years were ended. Then she was going. When the souls saw her going they rose up with one cry, lest one of them should be left. They went clinging to her; they were hanging to her hair, all that were in the boiler. She moved on with her burden.

She had not gone far when a lady in a carriage met her.“Oh! great is your burden,” said the lady, “will you give it to me?”“Who are you?” said she. “I am the Virgin Mary.”“I will not give it to you.”

She moved on with herself. She had not gone far when a gentleman met her. “Great is your burden, my poor woman’; will you give it to me?”“Who are you?” said she“I am God,” said he.“I will not give my burden to you.”

She went on with herself another while. Another gentleman met her. “Great is the burden you have,” said the gentleman; “will you give it to me?”“Who are you?” said she.“I am the King of Sunday,” said he.“I will give my burden to you,” said she. “No rest had I ever in hell except on Sunday.” “Well, it is a good woman you are; the first lady you met, it was the devil was there; the second person you met, it was the devil was there, trying if they could get your burden from you back. Now,” said God, “the man for whom you have done all this is going to be married tomorrow. He thought you were lost since you were in that place so long. You will know nothing till you are at home.”

She knew nothing till she was at home. The house was full of drinking and music. She went to the fire. Her own son came up to her.

She was making him wonder, she was so worn and wasted. She told the child to go to his father and get a glass of whisky for her to drink. The child went crying to look for his father. He asked his father to give him a glass of whisky. His father gave it. He came down where she was by the fire. He gave her the glass. She drank it, there was so much thirst on her. The rinf that her husband gave her she put in the glass.

“Put your hand over the mouth of the glass; give it to no one at all till you hand it to your father.”

The lad went to his father. He gave him the glass, The father looked into it, and saw the ring. He recognised the ring.

“Who has given you this?” said he.“A poor woman by the fire,” said the lad.

The father raised the child on his shoulder that he might point out to him the woman who had given him the ring. The child came to the poor woman. “That is the woman,” said he, “who gave me the ring.”

The man recognised her then. He said that hardly did he know her when she came so worn and wasted. He said to all the people that he would never marry any woman but this one; that she had done everything for him; that his mother sold him to the devil, and the woman had earned him back; that she had spent fourteen years in hell, and now she had returned

This is a true story. They are all lies but this one.

More on William Larminie's "West Irish Folk-Tales" in my book of essays on folklore and fairytales, "Seven Miles of Steel Thistles"

Picture credits: The Woman Who Went To Hell - (artist unknown) frontispiece to "The Woman Who Went To Hell: and other ballad and lyrics" by Dora Sigerson (Mrs Clement Shorter), De la More Press, 1902

Published on May 12, 2020 02:47

May 5, 2020

Strong Fairy Tale Heroines #11: FUNDEVOGEL

FUNDEVOGEL, or BIRD-FOUNDLING

This sweet story is one of the Grimms’ ‘Children’s and Household Tales’. translated by Margaret Hunt in 1884. The Grimms note that it comes “from the district of Schwalm in Hesse. It is also told that the cook was the wicked wife of the forester, and the question and answer are differently given: for instance, ‘You should have gathered the rose and the bush would have followed you.”’ Like 'The Mastermaid', this tale is is Aarne–Thompson type 313A, 'the girl helps the hero flee' - which I reckon ought to be renamed 'the heroine rescues the boy'!

It’s a simple but satisfying tale: Lina, who has magical skills, is the boy’s foster sister and he her adopted brother. The pair are only children, but the tenderly repeated refrain, ‘Never leave me and I will never leave you’ suggests they may marry later on, as happens in another of the Grimms’ tales, ‘Sweetheart Roland’, to which it is related. This type of tale is very different from those darker stories in which sisters endure hardship and suffering for the sake of their brothers.

The extorted promise with which the wicked cook binds little Lina is a standard feature, as is the wickedness of the cook in the first place (fairy tales are built of standard features - we accept them as we accept the construction of a sonnet), but in this story the bond between the children proves stronger than the promise.

There was once a forester who went into the forest to hunt, and as he entered it he heard a sound of screaming, as if a little child were there. He followed the sound and it led him to a high tree, and at the top of this tree a little child was sitting – for a bird of prey had seen it, flown down and snatched it away, and dropped it into the tree.

The forester climbed up and brought the child down. He thought, “I’ll take him home, and he shall grow up with our Lina.” So he took it home and the two children grew up together, and they named the boy who was found in the tree Fundevogel, since a bird had carried him away. And Fundevogel and Lina loved each other dearly.

Now the forester employed an old woman to cook for him. One evening she took two pails and kept going back and forth to the brook, fetching more and more water. Lina saw this and asked, “Old Sanna, why are you fetching so much water?”

“If you will never repeat it to anyone, I will tell you.” So Lina said no, she would never repeat it to anyone, and then the cook said, “Tomorrow morning when the forester is out hunting I will heat the water, and when it is boiling, I will throw Fundevogel in, and boil him to death.”

Early next morning the forester got up and went out hunting while the children were still in bed. Then Lina said to Fundevogel, “If you will never leave me, I will never leave you.” Fundevogel said, “Never will I leave you – not now, nor ever!” Then said Lina, “Then I will tell you. Last night old Sanna carried so many buckets of water into the house that I asked her why she was doing it, and she said that she would tell me, if I promised not to tell anyone, so I promised, and she said that early in the morning when father was out hunting, she would boil the water in the big kettle and throw you in. So let us get up quickly, dress, and go away together.”

So the children dressed themselves quickly and went away. When the water in the kettle was boiling, the cook went to the bedroom to find Fundevogel, but both the children were gone. The cook was now terribly alarmed. “What shall I say now when the forester comes back?” she said to herself. “The children must be caught and brought back home,” and she sent three servants running after them.

When the children looked back from the edge of the forest and saw the three servants running after them, Lina said to Fundevogel, “Never leave me and I will never leave you.” Fundevogel said, “Neither now, nor ever will I leave you.” Lina said, “Then you shall become a rose tree and I the rose upon it.”

When the servants came to the forest, there was nothing to be seen but a rose tree with one rose on it; the children were nowhere. “Nothing to be done here,” said they, and returned to the old cook and told her they had seen nothing but a rose tree with a single rose.

How the cook scolded! “You simpletons! You should have cut the rose bush in half and broken the rose off and brought it to me: go and do it at once!”

Off went the servants for a second time, but again the children saw them coming. Lina said, “Fundevogel, never leave me and I will never leave you.” “Neither now, nor ever,” said Fundevogel, and Lina said, “Now you shall become a church, and I’ll be the chandelier in it.”

So when the three servants came, nothing was to be seen but a church with a fine chandelier hanging inside it. “What can we do here?” they said to each other. “We will have to go home.” So they went home, and told the cook they had seen nothing but a church with a chandelier in it. “Fools!” scolded the cook. “You should have knocked the church to pieces and pulled down the chandelier and brought it back with you.” And now the old cook herself set off with the three servants in pursuit of the children.

When the children looked back this time and saw the old cook waddling after them, Lina said, “Fundevogel, never leave me and I will never leave you.” And Fundevogel said, “Neither now, nor ever!” Then said Lina, “You shall be a fishpond and I will be the duck on it.”

Well, the old cook caught up with them, and she saw the pond, and lay down beside it so that she could drink it all dry. But the duck swam smartly up to her. It seized her head in its beak and pulled her into the water, and there the old witch was drowned. Then the children were heartily delighted and went home together, and if they have not died they are living there still.

More on fairy tales and folklore in "Seven Miles of Steel Thistles" available at these links: here and here.

Picture credits:

Fundevogel - the child in the tree - by Mercer MayerFundevogel: The cook goes back and forth to the well: Arthur Rackham

Fundevogel - The children see the three servants - Artist unknown

Published on May 05, 2020 02:43

April 28, 2020

Strong Fairy Tale Heroines #10: WHUPPITY STOORIE

Illustration by Kate Leiper: www.kateleiper.co.uk/Instagram:kate_leiper_artist

Illustration by Kate Leiper: www.kateleiper.co.uk/Instagram:kate_leiper_artistThis Scottish tale is included in Robert Chambers’ ‘Popular Rhymes of Scotland’ (1841 edition) and comes from the manuscript of Chambers’ friend Charles K. Sharpe. It’s presented as if narrated by one ‘Nurse Jennie’ of Annandale whose Lowland Scots tongue is so vivid and racy (whether she actually existed or not!) that it would be a shame to anglicize it. So I have simply added a variety of explanatory notes, some within the text and some footnotes. I'm sure we Sassenachs can manage!

The heroine of the story is ‘the goodwife o’ Kittelrumpit’. The narrator suggests this place may be situated “somewhere amang the Debatable Ground”. In fact I think it’s a joke, a made-up name with a comic and mildly rude meaning;‘Tickle-arse’ would be my best bet, though I’m no Scots scholar, so if anyone knows better, do let me know. The Debatable Ground does exist: it is the much fought-over area between Scotland and England which, in the 16th century, was the haunt of the Border Reivers.

The tale is one of the many variants of the Rumpelstiltskin story, but a lot funnier and livelier. The goodwife and the green fairy woman are splendidly-matched antagonists – two energetic, determined women with sharp tongues in their heads: but the goodwife wins hands down when she turns the tables on her foe. The lovely illustration is by Scottish artist Kate Leiper and you can see more of her beautiful work by clicking the link below the picture: also here: http://kateleiper.co.uk/

The story begins when the goodwife’s husband goes off to the fair one day and never comes back: he was “a vaguing sort of body” anyway and not to be depended upon. Left to fend for herself – “A’body said they were sorry for her but naebody helpit her, whilk’s a common case, sirs,” – she has nothing left but her cottage – a “sookin’ lad bairn” (that's a baby boy still at the breast) – and her pride and joy, a “soo” (sow) which is about to give birth to piglets. If all goes well, the goodwife’s stock will be much increased. But one day she goes to the pigsty to fill the sow’s trough, and shock! horror! what should she find but the sow “lying on her back, grunting and groaning and ready to gie up the ghost”?

Read on!

I trow this was a new stoon [blow] to the goodwife’s heart; she sat doon on the knocking-stane

Noo, the cot-hoose of Kittlerumpit was built on a brae

Aweel, when the goodwife saw the green gentlewoman near her, she rose and made a curtsie; and “Madam,” quo’ she, weeping, “I’m the maist misfortunate woman alive.”

“I dinna wish to hear pipers’ news and fiddlers’ tales,” quo’ the green woman. “I ken ye’ve lost your goodman – we had waur losses at the Shirra Muir

“Onything your leddyship’s madam likes,” quo’ the witless goodwife, never guessing who she had to deal with.

“Let’s wet thumbs on that bargain

She glowers at the soo for a lang time, and then begins to mutter to herself what the goodwife couldna well understand; it soundit like “Pitter patter, Haly watter.” Then she took oot of her pouch a wee bottle wi’ something like oil in it, and rubs the soo with it around the snout, behind the lugs and on the tip o’ the tail. “Get up, beast,” quo’ the green woman, and nae sooner said than done – up bangs the soo wi’ a grunt and awa’ to her trough for her breakfast.

The goodwife o’ Kittelrumpit was a joyful goodwife noo, and wad hae kissed the very hem o’ the green madam’s gown-tail, but she wadna let her. “I’m no fond o’ demonstrations,” said she, “noo that I hae righted your sick beast, let’s finish our bargain. Ye’ll no find me an unreasonable, greedy body – I like aye to do a good turn for a small reward – all I ask, and will have, is that lad bairn in your bosom.”

The goodwife o’ Kittelrumpit let oot a skirl like a stickit gryse [stuck piglet]. The green woman was a fairy, nae doubt of it, so she prays and weeps and kneels and begs and flytes, but it wouldna do. “Ye may spare your din,” quo’ the fairy, “skirling as if I was a deaf as a doornail; but this I’ll tell ye – by the law we live on, I canna take your bairn till the third day after this; and no then, if ye can tell me my right name.” And off gaes madam around the pigsty end, and the goodwife falls down in a swoon behind the knocking-stane.

Aweel, the goodwife couldna sleep that night for weeping and a’ the next day the same, cuddling her bairn till she near squeezed its breath out; but the second day she thinks o’ taking a walk in the wood, and wi’ the bairn in her arms she sets out and gaes far in amang the trees where there was an old quarry hole grown o’er wi’ gorse, and a bonny spring well in the middle of it. Before she came very nigh, she hears the birring of a lint-wheel [a wheel for spinning flax], and a voice lilting a sang; sae the wife creeps quietly amang the bushes, and keeks [peeps] ower the brow of the quarry, and what does she see but the green fairy kemping at her wheel and singing:

“Little kens our good dame at hameThat Whuppitie Stoorie is my name!”

“Ah ha!” thinks the wife. “I’ve gotten the mason’s word at last: the de’il gie them joy that tell’t it!” And she gaed hame far lichter than she came out, as you may guess, laughing like a madcap wi’ the thought of begunkin [befooling] the auld green fairy.

Aweel, ye must ken that this goodwife was a jocular woman and aye merry when her heart wasna sair overladen, sae she thinks to have some sport wi’ the fairy: and at the appointit time she puts the bairn behind the knocking-stane and sits down on it hersel’. Syne she pulls her nightcap ajee [awry] ower her left lug [ear], crooks her mouth on t’ither side, as if she were weeping – and a filthy face she made, ye may be sure. She hadna lang to wait, for up the brae mounts the green fairy, neither lame nor lazy, and lang afore she got near the knocking-stane, she skirls out,

“Goodwife o’ Kittelrumpit, ye ken weel what I come for – stand and deliver!”

The wife pretends to greet sairer [weep more sorely] than before, and wrings her nieves [fists], and falls on her knees, wi’: “Och, sweet madam mistress, spare my only bairn and take the weary soo!”

“The de’il take the soo, for my share,” quo’ the fairy. “I come na here for swine’s flesh. Dinna be contramawcious, hizzie [hussy, wench], but gie me the gett [child; begotten] instantly!”

“Ochone, dear leddy mine,” quo’ the goodwife, “forbear my poor bairn and take mysel’!”

“The de’il’s in the daft jade,” quo the fairy, looking like the far-end o’ a fiddle

I trow this set up the wife o’ Kittelrumpit’s birse [put up her hackles]; for though she had two bleared een and a lang red neb [nose] forbye, she thought hersel’ as bonny as the best o’ them. Sae she bangs aff her knees, sets her nightcap

Gin a fluff o’ gunpowder had come out o’ the ground, it couldna hae made the fairy loup [leap] higher than she did; then down she came again, thump on her shoe-heels, and whirling around, she ran down the brae, screeching for rage like an owlet chased wi’ the witches.

The goodwife o’ Kittelrumpit laughed till she was like to ryve [split]; then she takes up her bairn and goes into her hoose, singing all the way;

A goo and a gitty, my bonny wee tyke,Ye’s noo hae your four-oories;Sin’ we’ve gi’en Nick a bane to pykeWi’ his wheels and his Whuppity Stoories.”

Published on April 28, 2020 02:34

April 21, 2020

Strong Fairy Tale Heroines #9: EDERLAND THE POULTRY-MAID

This light-hearted story comes from 'Danish Fairy Tales', collected by Svendt Grundtvig, (1824-1883) and is a good follow up to last week's tough Cinderella, employing several of the same motifs to very different effect. A dying mother leaves most of her possessions to her two eldest daughters, gifting the youngest, little Ederland, with nothing but a dough pan, an apron and a broom. Her sisters deride her, telling her that their mother thought nothing of her, but Ederland holds fast to a belief in her mother's love. When her sisters make further difficulties for her, she visits her mother's grave - again like Cinderella - where her faith in her mother is upheld, and her apparently poor legacy turns out to be the very thing that makes her fortune.

Buoyed by her mother's advice, Ederland sets off on her adventures. With cheerful élan she tricks a family of trolls and wrests three precious things from them, one of which - the pig that never diminishes no matter how much bacon is sliced from it - perhaps hails back to the boar Sæhrímnir on which the Norse gods feast nightly in Valhallr (besides irresistably reminding me of the Dish of the Day in Douglas Adams' 'The Restaurant at the End of the Universe': see link here.) Ederland's marriage to a distinctly selfish master ('You could easily do it if you wanted to!' he keeps moaning) is the traditional fairy tale coda, denoting her worldly success. Fairy tales are almost never romances.

I hope you'll agree with me that Ederland is another tough cookie. Just don't feel too sorry for the trolls!

Once upon a time there was a woman who had three daughters. She was very ill and she expected to hear death knock at her door from day to day; so she called together her three daughters and divided what she had among them. But she did not make an equal division: she gave the two older daughters, who were always nice to look at, and kept themselves well dressed, all that she had; and the youngest, little Ederland, received only a dough-pan, a broom-stick and an apron.

The mother lived but a short time, and when she had died, what she had left was divided between her children as she had arranged. Then the two older sisters said to Ederland, "That shows you once more, Ederland, that our mother thought more of us than she did of you, for all she gave you was that wretched dough-pan, and the broom-stick and apron."

But little Ederland was patient, and held her tongue, and still believed that her mother had loved her just as much as she had her two sisters.

In the course of time all three sisters took service in a fine house. The two older sisters were in the house itself, and helped with all the housework; but little Ederland was only the poultry-maid. Yet before long the master of the house noticed that his poultry had never been in better condition than since Ederland had taken charge; and therefore he praised her continually in her sisters' presence.They did not enjoy hearing it at all. At last they decided to tell their master that Ederland could do much more, if only she felt like it. They knew positively, that she could get him a candlestick that would give light without a candle; and if she said she could not, it merely showed that she would not.

When their master heard this, he at once sent for Ederland and said to her, "I hear that you can get me a candlestick that gives light without a candle. I want to have it very much, and you must get it for me. It is useless for you to refuse, for I know that you can if you feel like it."

Little Ederland cried, and said she would like to oblige him if only she knew how; but that he had set her a task she really could not accomplish. Yet her master would not believe her.

"All your speeches won't help you," he said. "You must get the candlestick for me, but you shall have two bushels of gold for getting it!"

Little Ederland left the house in tears, and went straight to her mother's grave. As she stood there and cried, her mother rose from the grave and said, "Do not cry! Go back home, and ask your master for two bushels of salt, take your broomstick, set it up as a mast in the dough-pan, tie your apron to it for a sail, and sail out to sea with your two bushels of salt. Then you will come to the place where you can get the candlestick that gives light without a candle!"

And with that the mother sank back into her grave, and little Ederland went home and asked her master for the two bushels of salt. She got them, and then set up her dough-pan with the broom-stick for a mast, and the apron for a sail, took her two bushels of salt, and sailed out on the stormy sea, letting the waves carry her along as they chose.

She sailed a long way, but at last she landed on the island of the trolls, and went ashore with the two bushels of salt. Somewhere about she saw a house. She went up to it, climbed on the roof, and looked down the chimney. Down below stood the old troll mother, cooking mush for her sons. On the hearth, beside the kettle of mush, stood the candlestick that gave light without a candle. This was just what Ederland wanted, and when the old troll mother turned her back, she poured down her two bushels of salt into the mush. The old troll mother turned right around again, and tasted the mush; but it was terribly salty. So she took up a bucket to get some water to cook over the mush. Then Ederland slipped down the chimney in a trice and ran after her, and as the old troll mother was stooping over the edge of the well to draw up the bucket, Ederland gave her a push so that she fell in head over heels, and did not come up again. Ederland now quickly secured the candlestick and ran down to her ship. She was no more than a short distance from land, when she saw the trolls come home, and a moment later they ran down to the strand and called after her, "Ederland, Ederland! You have thrown our mother into the well and taken our candlestick! If you ever come here again you will have to pay the price!"

But Ederland called back, "Well, I am coming back twice!" and sailed gaily home.

Her master was filled with joy when he saw the candlestick that gave light without a candle, and little Ederland received her two bushels of gold and was happy as well. But her two sisters grew more angry with each passing day at her good fortune, and their only thought was of how they might mar her pleasure. At last they again told their master that Ederland could do much more if she only would. She could get a horse with bells on all four legs, one that could be heard long before it was seen, and that could be found again, no matter how far it had strayed. Their master would much rather have had a horse of that kind even than the candlestick he already possessed. He had Ederland called at once, and told her that he was well aware that she could obtain a horse that had bells on all four of its legs, which one could hear in the distance, and could always find if it strayed. She must get him that horse! Ederland cried and said she was only too willing to get it, but she did not know how. Yet her master would not content himself with her answer.

"You could, if you only would," he said. "You must get that horse for me and I will give you three bushels of gold for it."

Again Ederland went to her mother's grave and cried, and was very unhappy. And again her mother rose from the grave and said to her, "Do not cry, my little Ederland! Go home and ask your master for four bunches of tow, take them and sit down in your dough-pan with the broomstick and the apron as before. Then you will reach the place where you can obtain the horse with the bells on all four legs."

Thereupon her mother sank back into the grave; while little Ederland went home and asked her master for the four bunches of tow. He gave them to her at once, and she sailed out to sea in her dough pan, with the broomstick for a mast, and her apron for a sail. This time she also landed on the island of the trolls.

It was just at the time when the trolls were at home, and were eating their dinner, and the horse with the bells on all four legs was grazing in the field before the house. Ederland slipped up to him, tied a bunch of tow around each leg, so that the bells could not ring, and led him down to the strand. Just as she was leading him into the boat, however, the bunch of tow about one of his legs fell off, the bell at once began to ring, and all the trolls hurried down to the strand. Little Ederland had led the horse safely aboard, and had just put a bit of water between the boat and the shore, when the trolls reached the beach. They fell into a terrible rage when they saw that Ederland was escaping with their horse, and called after her, "Ederland, Ederland! You pushed our old mother into the well, and took our candlestick, and now you have stolen our horse! When you come again you will have to pay for it!"

But Ederland called back to them, "Well, I am coming back once more!"

When Ederland reached home with the horse, her master was filled with joy. He gladly gave her the three bushels of gold he had promised her, and Ederland herself was very happy. But her two sisters were not at all pleased with her good fortune, and day and night they thought only of what harm they might do her. Before long they said to their master, "Ederland could get you something far better than she has already obtained for you: a pig that stays just as fat as it was, though you cut as much bacon from it as ever you will."

That seemed the best of all to their master. Ederland had to come to him at once and he said to her, "I have heard that you can get a pig for me from which I may cut as much bacon as ever I will, while it stays as fat as it was. That pig I must have."

In vain Ederland wept and said, "I would, if only I could; but I cannot get any such pig for you."Her master would not listen to her. "You can and must obtain that pig for me," he said, "and in return I will give you all the beautiful things which you see here."

But little Ederland was very sad. She went to her mother's grave and wept bitterly. Then her mother rose from her grave, and said to her, "Do not cry, my little Ederland! Go home and ask your master for two flitches of bacon, seat yourself in your boat, and sail out to sea. Then you will come to the place where you can get the pig. " " When she had said this she sank back into her grave.But Ederland went home and got the two flitches of bacon, put them in her dough-pan with the broomstick for a mast and the apron for a sail, and the wind blew her across the sea to the island of the trolls. It was just the time when the trolls were taking their after-dinner nap. The pig was in the meadow, but the trolls had hired a little boy to watch it.

Ederland ran up to the little boy and said to him, "These two flitches of bacon are for the trolls. Will you carry them over to them while I take care of the pig for you in the meantime?" The boy saw no harm in this, so he took the bacon and ran with it to the house. But as he was telling the trolls how he came by the two flitches of bacon, they at once thought that Ederland might have a hand in the matter again, so they ran down to the beach as fast as they could. And there Ederland had been unable to get the pig into the boat.

So the trolls seized her as well as the pig. They dragged Ederland into the house, and handed her over to the old troll father, telling him to slaughter her, and dish up a real tasty supper for them when they came back from work. Then the trolls went off, and Ederland stayed behind with the old troll father. He dragged up a great block of wood, put down the axe beside it and said to her, "Now lay down your head on the block so that I can chop it off."

"Yes," said little Ederland, "I'm willing to do so, but I do not know how. First you will have to show me."

"Why," said the old troll father, "it is quite simple, you only need to do like this," and as he spoke he laid his head down on the block. In a moment Ederland had seized the axe and chopped off his head with a single stroke. She at once put a nightcap on the head, laid it in bed, and thrust the body into the soup-kettle that hung over the hearth. Then she ran down to the beach, took the pig and sailed away in her boat.

Not long after the trolls came home, and at once fell on the supper cooking over the stove. They were much surprised to find the meat so tough, when the person who had furnished it was so young. But they were hungry and managed to get it down. At last it occurred to one of them that their old father should also have his share. He went over to the bed and shook him; but they all were much frightened when they realized that his head alone was lying on the bed. At last they saw how everything had happened, left their supper and ran down to the beach. But by that time Ederland was far out to sea. The trolls came down in the most furious rage, and called after her, "Ederland, Ederland! You pushed our old mother into the well, you took our candlestick, you stole our horse, and now you have killed our old father and robbed us of our pig. If you come here again you will have to pay for it!"

But Ederland called back, "I shall never, never come back, and you need not expect me!"

So little Ederland sailed home, and her master received her very joyfully, and soon after they married and lived in peace and contentment. Her sisters lived with her, but they did nothing day by day, save brood over Ederland's good fortune.

One day Ederland said to them, "If you feel like sailing, you are welcome to my boat." The sisters decided to try it at once. They got into the boat, set sail and came to the island of the trolls. But when they got there the trolls seized them, cooked them and fried them, and were pleased as pleased could be to have made such a haul.

Picture credits:

Ederland the Poultry Maid: 'She sailed out upon the stormy sea, letting the waves carry her as they chose' : by George W HoodTroll mother and son, by John Bauer

Published on April 21, 2020 02:57

April 14, 2020

Strong Fairy Tale Heroines #8: ASCHENPUTTEL

Aschenputtel: The Cinderella of the Brothers Grimm

The most familiar of fairytales can seem strange when we read a different version from the one we’re used to. Most of us know the one generally offered to children, the one Disney adapted, the one based on Charles Perrault’s ‘Cendrillon’. ThatCinderella is a long-suffering, patient, gentle girl; her fairy godmother is a civilised sponsor who launches her protégé into society with the aid of delightful conjuring tricks, transforming pumpkin and mice into a splendid coach and uniformed servitors. At the end of Perrault's tale, Cinderella forgives her stepsisters and marries them off to ‘two great lords of the court’. Everything is in excellent taste.

But the heroine of the Grimms’ ‘Aschenputtel’ is different. Her story is less literary, more magical: almost savage in tone and detail. There is blood within the shoe. The dead return as birds. There's no pumpkin coach, no fairy godmother. No panic, no deadlines, no clocks striking twelve. No glass slipper – and no forgiveness.

The mother’s deathbed adjuration, that if her daughter remains good, she will watch over her from heaven, is less a pious wish than a supernatural promise, fulfilled when her father asks his daughters what he should bring them as gifts and Cinderella asks not for beautiful clothes, pearls and jewels as her step-sisters do, but for ‘the first branch which knocks against your hat on the way home’. Like the rose in Beauty and the Beast, this humble gift will prove the most precious, as well as being something that will certainly pass under her step-mother and step-sisters’ radar. Cinderella plants the hazel twig on her mother’s grave and waters it with her tears. And in contrast to the civilised patronage of Perrault’s fairy godmother, the power the girl derives from her true mother’s grave is a miraculous inheritance that rises from the earth in green sap and leaves, with spirit-like birds sitting in the branches.

At her call, these birds flock down to perform the impossible tasks her stepmother sets for her – and each time Cinderella succeeds, the stepmother breaks her promise to allow her to go to the festival. We are not meant to view this realistically, or ask why the stepmother and Cinderella should expect any different outcome from each other after the first demonstration. We are witnessing the breaking of a ritual, magical contract which will earn a ritual, magical punishment.

The unbroken bond between Cinderella and her dead mother trumps the step-mother’s broken promises. For the next three nights, as the white birds in the hazel tree shower down upon her their transformative gold and silver, Cinderella stage-manages the whole affair. She goes to the dance alone. She leaves when she pleases. She runs, climbs trees and jumps out of them. She performs lightning costume-changes, and she lies low to deceive the family.

It's a story which pulls few punches. Quite frankly, a great deal of the pleasure it affords is the pleasure of revenge. This Cinderella gets her own back on everyone who has ill-treated her. When her neglectful father’s pigeon house is destroyed, we shouldn't think of a cute ornamental dove-cot sitting on a pole. We should imagine the pigeon-house of a grand mansion: a great, circular, stone-built affair with hundreds of niches inside it for nesting places, and a revolving ladder from which servants might collect eggs and young birds. Its destruction would be a social and financial blow. Her father also loses his magnificent pear tree - it is chopped to pieces – and her ambitious step-sisters fare even worse. And, an incidental detail - the prince doesn't need to try the slipper on the foot of every girl in the kingdom. By the third night he's got a very good idea of where Cinderella lives, so the mysterious maiden has to be one of the three daughters.

The translation is by Margaret Hunt.

The wife of a rich man fell sick, and as she felt that her end was drawing near, she called her only daughter to her bedside and said, “Dear child, be good and pious, and then the good God will always protect you, and I will look down on you from heaven, and see you.” Thereupon she closed her eyes and departed. Every day the maiden went out to her mother’s grave and wept, and she remained pious and good. When winter came the snow spread a white sheet over the grave, and by the time the spring sun had drawn it off again, the man had taken another wife.

The woman brought with her into the house two daughters, who were beautiful and fair, but vile and black of heart. Now began a bad time for the poor step-child. “Is the stupid goose to sit in the parlour with us?” they said. “He who wants to eat bread must earn it; out with the kitchen-wench.” They took her pretty clothes away from her, put an old grey bedgown on her, and gave her wooden shoes. “Just look at the proud princess, how decked out she is!” they cried, and laughed, and led her into the kitchen. There she had to do hard work from morning till night, get up before daybreak, carry water, light fires, cook and wash. Besides this, the sisters did her every imaginable injury – they mocked her and emptied her peas and lentils into the ashes, so that she was forced to sit and pick them out again. In the evening when she had worked till she was weary she had no bed to go to, but had to sleep by the hearth in the cinders. And as on that account she always looked dusty and dirty, they called her Cinderella.

It happened that the father was once going to the fair, and he asked his two step-daughters what he should bring back for them. “Beautiful dresses,” said one, “pearls and jewels,” said the second. “And you, Cinderella,” said he, “what will you have?” “Father, break off for me the first branch that knocks against your hat on the way home.” So he bought beautiful dresses, pearls and jewels for his two step-daughters, and on his way home as he was riding through a green thicket, a hazel twig brushed against him and knocked off his hat. Then he broke off the branch and took it with him. When he reached home he gave his step-daughters the things which they had wished for, and to Cinderella he gave the branch from the hazel bush. Cinderella thanked him, went to her mother’s grave and planted the branch on it, and wept so much that the tears fell down on it and watered it. And it grew and became a handsome tree. Thrice a day Cinderella went and sat beneath it and wept and prayed, and a little white bird always came on the tree, and if Cinderella wished for anything, the bird threw down to her what she had wished for.

It happened, however, that the King gave orders for a festival which was to last three days and to which all the beautiful young girls in the country were invited, in order that his son might choose himself a bride. When the two step-sisters heard that they too were to appear among the number, they were delighted, called Cinderella and said: “Comb our hair for us, brush our shoes and fasten our buckles, for we are going to the wedding at the King’s palace.” Cinderella obeyed, but wept, for she too would have liked to go with them to the dance, and begged her step-mother to allow her to do so. “You go, Cinderella!” said she; “covered in dust and dirt as you are, and would go to the festival? You have no clothes and shoes, and yet would dance?” However, as Cinderella went on asking, the step-mother said at last, “I have emptied a dish of lentils into the ashes for you; if you have picked them out again in two hours, you shall go with us.”

The maiden went through the back door into the garden and called, “You tame pigeons, you turtledoves, and all you birds beneath the sky, come and help me to pick

The good into the potThe bad into the crop.”

Then two white pigeons came in by the kitchen window, and afterwards the turtledoves, and at last all the birds beneath the sky, came whirring and crowding in, and alighted amongst the ashes. And the pigeons nodded with their heads and began pick, pick, pick, and all the rest began also to pick, pick, pick, and gathered all the good grains into the dish. Hardly had one hour passed before they had finished and all flew out again. Then the girl took the dish to her step-mother, and was glad, for she believed that now she would be allowed to go with them to the festival.

But the step-mother said, “No, Cinderella, you have no clothes and you can not dance; you would only be laughed at.” And as Cinderella wept at this, the step-mother said, “If you can pick two dishes of lentils out of the ashes for me in one house, you shall go with us.” For she thought to herself, “That she most certainly cannot do again.”

When the step-mother had emptied the two dishes of lentils among the ashes, the maiden went through the back door into the garden and cried: “You tame pigeons, you turtledoves, and all you birds beneath the sky, come and help me to pick

The good into the potThe bad into the crop.”

Then two white pigeons came in by the kitchen window, and afterwards the turtledoves, and at last all the birds beneath the sky, came whirring and crowding in, and alighted amongst the ashes. And the pigeons nodded with their heads and began pick, pick, pick, and all the rest began also to pick, pick, pick, and gathered all the good seeds into the dishes, and before half an hour was over they had already finished, and all flew out again. Then the maiden carried the dishes to ther step-mother and was delighted, and believed that she might now go with them to the wedding. But the step-mother said, “All this will not help; you cannot go with us, for you have no clothes and can not dance; we should be ashamed of you.” On this she turned her back on Cinderella and hurried away with her two proud daughters.

As no one was now at home, Cinderella went to her mother’s grave below the hazel tree, and cried,

“Shiver and quiver, little tree, Silver and gold throw down on me.”

Then the bird threw a gold and silver dress down to her, and slippers embroidered with silk and silver. She put on the dress with all speed, and went to the wedding. Her step-sisters and the step-mother did not know her and thought she must be a foreign princess, for she looked so beautiful in the golden dress. They never once thought of Cinderella and believed she was still at home in the dirt, picking lentils out of the ashes. The prince approached her, took her by the hand and danced with her. He would dance with no other maiden, and never let loose of her hand, and if any one else came to invite her, he said, “This is my partner.”

She danced till it was evening, and then she wanted to go home. But the King’s son said, “I will go with you and bear you company,” for he wished to see to what family the beautiful maiden belonged. She escaped from him, however, and sprang into the pigeon-house. The King’s son waited until her father came home, and then he told him that the unknown maiden had leapt into the pigeon-house. The old man thought, “Can it be Cinderella?” and they had to bring him an axe and a pickaxe that he might hew the pigeon house to pieces, but no one was inside it. And when they got home, Cinderella lay in her dirty clothes among the ashes, and a dim little oil lamp was burning on the mantle-piece, for Cinderella had jumped down quickly from the back of the pigeon-house and had run to the little hazel tree, and there she had taken off her beautiful clothes and laid them on the grave, and the bird had taken them away again, and then she had seated herself in the kitchen amongst the ashes in her grey gown.

Next day when the festival began afresh, and her parents and the step-sisters had gone once more, Cinderella went to the hazel tree and said,

“Shiver and quiver, my little tree, Silver and gold throw down over me.”

Then the bird threw down a much more beautiful dress than before. And when Cinderella appeared at the wedding in this dress, everyone was astonished at her beauty. The King’s son had waited until she came, and instantly took her by the hand, and danced with no one but her. When others came and invited her, he said, “This is my partner.” When evening came she wished to leave, and the King’s son followed her and wanted to see to which house she went. But she sprang away from him and into the garden behind the house. There stood a beautiful tree on which hung the most magnificent pears. She clambered so nimbly between the branches like a squirrel that the King’s son did not know where she had gone. He waited until her father came and said to him, “The unknown maiden has escaped from me, and I believe she has climbed into the pear tree.” The father thought, “Can it be Cinderella?” and had an axe brought and cut the tree down, but no one was in it. And when they got into the kitchen, Cinderella lay there among the ashes as usual, for she had jumped down on the other side of the tree, had taken the beautiful dress to the bird on the little hazel tree, and put on her grey gown.

On the third day, when the parents and sisters had gone away, Cinderella went once more to her mother’s grave and said to the little tree,

“Shiver and quiver, my little tree, Silver and gold throw down over me.”

And now the bird threw down to her a dress which was more splendid and magnificent than any she had yet had, and the slippers were golden. And when she went to the festival in the dress, no one knew how to speak for astonishment. The King’s son danced with her only, and if anyone invited her to dance, he said, “This is my partner.”

When evening came, Cinderella wished to leave, and the King’s son was anxious to go with her, but she escaped from him so quickly he could not follow her. The King’s son, however, had caused the whole staircase to be smeared with pitch, and there, where she ran down it, the maiden’s left slipper had remained stuck. The King’s son picked it up,and it was small and dainty, and all golden. Next morning he went to his father and said, “No one shall be my wife but she whose foot this golden slipper fits.”

Then the two sisters were glad, for they had pretty feet. The eldest went with the shoe into her room and wanted to try it on, and her mother stood by. But she could not get her big toe into it, and the shoe was too small for her. Then her mother gave he a knife and said, “Cut the toe off; when you are Queen you will have no more need to go on foot.” The maiden cut the toe off, forced her foot into the shoe, swallowed the pain and went out to the King’s son. He took her on his horse as his bride and rode away with her, but the way took them past the grave and there on the hazel tree sat the two pigeons and cried,

“Turn and peep, turn and peep, There’s blood within the shoe, The shoe it is too small for her, The true bride waits for you.”

Then he looked at the foot and saw how the blood was trickling from it. He turned his horse around and took the false bride home again and said she was not the true one, and that the other sister was to put the shoe on. Then this one went into her chamber and got her toes safely into the shoe, but her heel was too large. So her other gave her a knife and said, “Cut a bit off your heel; when you are Queen you will have no more need to go on foot.” The maiden cut a bit off her heel, swallowed the pain, and went out to the King’s son. He took her on his horse as his bride and rode away with her, but when they passed the hazel tree, the two little doves sat on it and cried,

“Turn and peep, turn and peep, There’s blood within the shoe, The shoe it is too small for her, The true bride waits for you.”

He looked down at her foot and saw how the blood was running out of her shoe and how it had stained her white stocking quite red. Then he turned his horse and took the false bride home again. “This also is not the right one,” said he, “have you no other daughter?” “No,” said the man, “there is still a little stunted kitchen wench which my late wife left behind her, but she cannot possibly be the bride.”

The King’s son said he was to send her up to him, but the mother answered, “Oh no, she is much too dirty, she cannot show herself!” But he absolutely insisted on it, and Cinderella had to be called. She first washed her hands and face clean, and then went and bowed before the King’s son, who gave her the golden shoe. Then she seated herself on a stool, drew her foot out of the heavy wooden shoe and put it into the slipper, which fitted like a glove. And when she rose up and the King’s son looked at her face he recognised the beautiful maiden who had danced with him and cried, “That is the true bride!” The step-mother and the two sisters were horrified and became pale with rage; however, he took Cinderella on his horse and rode away with her. As they passed by the hazel tree, the two white doves cried,

“Turn and peep, turn and peep, No blood is in the shoe, The shoe is not too small for her, The true bride rides with you,”

and when they had cried that, the two came flying down and perched on Cinderella’s shoulders, one on the right, the other on the left, and remained sitting there.

When the wedding with the King’s son was to be celebrated, the two false sisters came and wanted to get into favour with Cinderella and share her good fortune. When the betrothed couple went to church, the elder was at the right side, and the younger at the left, and the pigeons pecked out one eye from each of them. Afterwards as they came back, the pigeons pecked out the other eye from each and so, for their wickedness and falsehood, they were punished with blindness for the rest of their days.

Picture Credits:

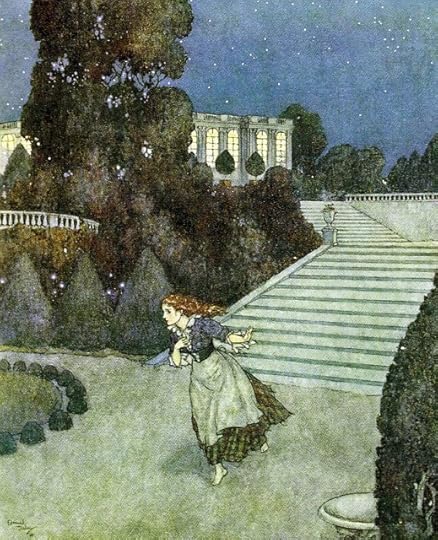

Cinderella: by Edmund DulacCinderella at the hearth: John Everett Millais

Aschenputtel at her mother's grave: by Liga-MartaAschenputtel and the turtledoves: by Alexander Zick

Aschenputtel and the stepsisters: by Hermann Vogel

Cinderella at the ball: by Edmund Dulac

Shiver and Quiver, Little Tree: by Millicent Sowerby

Pitch on the stairs: by John D Batten

Cinderella running: by Arthur Rackham Cinderella tries on the slipper: by Walter Crane

Published on April 14, 2020 02:26

April 7, 2020

Strong Fairy Tale Heroines #7: THE MASTERMAID

This fast-moving Norwegian fairy tale from Asbjørnsen and Moe was translated into English by Sir George Dasent in ‘Popular Tales from the Norse’ (1859). Nineteenth century translations can feel a little stiff nowadays and we tend to read them with too much respect. I decided to tell this story aloud a few months ago, but it came to life for me when I tweaked it a bit and told it in a strong Yorkshire accent (which is where I'm from). Traces of this should be obvious in the version below. This helped me bring out not only the Northern-ness of the tale, but also the sheer fun and naughtiness of the original, such as the bit near the end, where the Mastermaid takes various men to bed with her only to make them stand up all night gripping such suggestive items as a poker or a calf’s tail...

The story begins as if it’s all going to be about a prince, but though he’s an attractive, cheeky lad, he can’t achieve anything without the Mastermaid (the clue’s in her name)! The tale is classed as Aarne–Thompson type 313A, 'the girl helps the hero flee', a category which in my opinion ought to be renamed 'the heroine rescues the boy'. The Mastermaid saves the prince's life four separate times, provides him with invaluable advice, organises his escape, saves him from marrying a troll, and generally sorts everything out with tremendous aplomb.

There was once a king’s son who had a fancy to see the world. Off he set, and after travelling for several days he found a door that was built into the mountain. It was the door to a troll’s house; he spent the night there and hired himself out next day as the troll’s servant.

In the morning, before the troll went out to graze his herd of goats on the mountain meadows, he told the king’s son to shovel out the stable. ‘I’m an easy-going master,’ he said, ‘when you’ve done that, you can have the rest of the day off, but do your work well, and don’t go poking into any of the other rooms in the house, or I’ll tear your head off.’

‘He does seem an easy master!’ said the lad to himself. He thought he’d have plenty of time, so he walked about humming, and then he thought he wouldtake a look into some of the other rooms. What might the troll be hiding?

In the middle of the first room a big cauldron was boiling and bubbling away with no fire under it! ‘What’s cooking?’ the king’s son wondered, and he looked in, a piece of his hair swung down into the broth and came out with each strand bright as copper.

‘Funny soup, that!’ said the lad, ‘if anyone sipped it, they’d have copper lips!’ and he went into the second room.

Here was another cauldron simmering away with no fire. ‘I’ll try this one too,’ he says and dips a second lock of hair in. Out it comes, shining silver. ‘Expensive soup!’ says he, ‘we’ve nothing like it my father’s castle, but how does it taste?’ and he went into the next room where there was a third cauldron bubbling and steaming.

The lad dipped another lock of hair in, and this time it came out gleaming gold. ‘Anyone who drank that would get a gilded gullet!’ he said, ‘but if that’s gold, what’ll I find next?’ and he opened the door to the fourth room, and in it a girl was sitting on a bench, the loveliest lass the lad had ever seen.

‘God in heaven,’ she says, ‘what do you want? And what are you doing here?’

‘I’ve just been hired by the troll,’ he says.

‘Have you any idea what you’ll have to do for him?’ she asks.

‘Oh he’s an easy sort of chap,’ says the king’s son. ‘All I have to do is muck out the stable, nothing hard, and then I can take time off.’

‘You think that’s easy? If you set about it the usual way, ten shovelfuls will fly in for every one you chuck out. I’ll tell you what to do: turn the pitchfork around and shovel with the handle, then all the muck will fly out by itself!’

He’d do that, all right, thought the king’s son, and then the two of them sat chattering away, falling in love, till as evening came the lad thought he’d better go out and do his work, and as soon as he turned the pitchfork upside down, all the muck flew out by itself to the dungheap and the stable was as clean as clean.

Troll comes back with the goats. ‘Have you shovelled out t'stable?’ he asks

. ‘I have that, it’s as clean as clean.’

‘I’ll see for myself!’ says the troll, and he came and saw, and he says, ‘You must have been talking to my Mastermaid! You haven’t got enough between the ears to have managed it yourself.’

‘Mastermaid?’ says the lad, pretending to be thick, ‘what sort of a thing is that? I’d love to see it. Can I see it?’

‘You’ll see soon enough,’ says the troll.

Next morning the troll gave the lad instructions to go up the mountain and bring down the horse which was grazing up there. ‘When you’ve done that you can take things easy the rest of the day, but don’t go into any of the other rooms, or I’ll wring your head off!’

‘Kind master or not,’ thought the king’s son, ‘I’ll talk to the Mastermaid all the same. Yours, is she? What if she’d rather be mine?’ and he went to see her.

‘What work has he given you today?’ she asks.

‘Nowt much,’ says the king’s son. ‘Just go up the mountain to fetch his horse.’

‘And how are you going to do that?’

‘Shouldn’t be hard, should it? I’ll bet I’ve ridden better horses than his!’

‘It won’t be as easy as you think,’ said the Mastermaid, ‘but I’ll tell you what to do. It’ll rush at you as soon as it sees you, breathing fire and flame, but if you take that bridle hanging there by the door and throw it over its head, it’ll calm down and follow you like a lamb.’

Well, the lad would certainly take her advice, and so they sat chatting and thought how wonderful it would be if they could get away together and escape the troll… and he would have forgotten all about going to fetch the horse if the Mastermaid hadn’t reminded him as evening came on, so he took the bridle and climbed the mountain, and as the horse came rushing at him with blazing eyes and flaming jaws he threw the bridle over its head, and then it was tame and followed him back like a lamb.

Troll comes home. ‘Is horse in’t stable?’

‘Oh aye,’ says the lad. ‘A nice quiet nag, I rode it back and shut it in the stall, I did.’

‘I’ll see for myself!’ says the troll. And there was the horse, just as the lad had said. ‘You must have been talking to my Mastermaid!’ said the troll. ‘You could never have worked that out for yourself!’

‘Mastermaid? Mastermaid? You said that yesterday, and still I don’t know what a Mastermaid is. I wish you’d show me, master, indeed I do,’ said the king’s son, thick as a brick.

‘You’ll find out soon enough!’ said the troll.

Next day the troll went out with his goats as before. ‘Today it’s off to hell with you, to fetch the fire-tax,’ he said to the lad. ‘You can take it easy the rest of the day! Lucky for you I’m such a kind master.’ Off he went.

‘Oh aye, very kind,’ says the lad, ‘to give me all the dirty jobs. I’d better find the Mastermaid.’ And he went to her. ‘What’ll I do? I’ve never been to hell. I don’t know the way! And I don’t know how much to ask for!’

‘Oh, I can tell you all that. Go to the cliff face below the mountain, take this club with you and knock on the wall with it. Then someone will come out with sparks flying off him. Tell him your errand, and when he asks how much you want, you say, “As much as I can carry!”’

Well, the lad thought he could do that, and then they sat talking all day long and he would be sitting there still if the Mastermaid hadn’t reminded him to go and fetch the fire tax before the troll came home.

Off he went and knocked at the cliff with the club, and out came someone swarming with sparks, fire flying from his hair and eyes and nose. ‘What do you want?’