Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 14

March 10, 2020

Strong Fairy Tale Heroines #3: THE PRINCESS IN ARMOUR, or Iliane of the Golden Tresses

This wonderful Romanian fairy tale plays all kinds of deliberate tricks with sexuality and gender stereotypes. It was collected (and perhaps enhanced, who knows?) by the Romanian folkorist Petre Ispirescu and was rendered into French by Jules Brun in 'Sept Contes Roumaines' (1892) with a commentary by folklorist Leo Bachelin.

The title varies from translation to translation. Jules Brun calls the tale ‘Jouvencelle, Jouvenceau' or ‘Young Woman, Young Man’ - which sounds neater in French than it does in English. Translating Brun’s story for ‘The Violet Fairy Book’, Andrew Lang’s wife Leonora Blanche Alleyne renamed it ‘The Girl Who Pretended to be a Boy’ (and added a few passages to emphasise the heroine's femininity). A translation directly from Romanian by Julia Collier Harris and Rea Ipcar in "The Foundling Prince and Other Tales" (Houghton Mifflin 1917), gives the title as ‘The Princess Who Would Be A Prince: or Iliane of the Golden Tresses’. All of these titles sound a little cumbersome in English, so I've gone out on a limb and called it 'The Princess in Armour', but kept the subtitle which refers to the second heroine of the story - for there are two!

The first heroine is an unnamed warrior princess who quite literally becomes the Romanian sun-hero, Fet-Frumos (Beautiful Son: Făt-Frumos in Romanian) - a warrior of immense chivalry and prowess. Besides his mythic origins, Fet-Frumos is the Prince Charming of Romanian fairy stories and the lover of Ileana Simziana: Iliane of the Golden Hair. Leo Bachelin considers Iliane to be the personification of youth and springtime, dawn and twilight; while he describes the warrior-girl heroine of this story as a sort of androgynous Apollo whose powers of light are bound to put shadows to flight. After all, her/his horse is called Sunray...

In the original Romanian, the heroic princess has to fight a folkloric creature called a Știmă. (T wo of them, in fact.) All the translations I've mentioned above render this word as 'genie', so I've followed them - but it almost certainly gives the wrong impression, especially if Disney's Aladdin comes to mind, since a Știmă seems to be a kind of dangerous nature spirit, who often has a connection with water: this may explain why the one which holds Iliane prisoner lives in 'the swamps of the sea.'

The version below is my translation from Brun's 'Sept Contes Roumaines'. The subtitle 'Iliane of the Golden Tresses' is important because Iliane is another significant personage in Romanian folk tales and mythology. According to this article in The Journal of Romanian Linguistics and Culture she is "the heroine of numerous songs, carols, and fairy tales; the most beautiful of all fairies, their queen, so beautiful that ‘one could look at the sun but not at her’. Her epithets are ‘the beautiful’, the moon fairy, ‘lady of the flowers’, protector of the wild animals and the forests..."

Given all this, the final twist at the end of the story might be taken any number of ways, but to my mind it is a consciously ironic comment on the power of masculinity.

There was once an emperor – oh yes, there was; if he hadn’t existed, how could I tell you about him? Very well then, there was once an All-Powerful Emperor. Victory after victory, he extended his empire over the whole wide earth, as far as to the place where the devil suckles his children! And he forced each of the emperors whom he subjugated to send him one of their sons to serve him for ten years.

Now, on the very edge of the borders of his realm, one last emperor stood against him. Year after year this emperor defended his realm and people until, growing old at last and losing his strength, he realised he too would have to submit.

But how was he going to to obey the command of the All-Powerful Emperor and send a son to serve him? He had no sons, only three daughters. How he worried! If he couldn't send a son, the Emperor would think him a rebel! He didn’t talk about it, but he imagined himself and his daughters thrown out of their lands and dying in misery and distress.

The sadness shadowing his face threw black sorrow on the white souls of his three daughters. Not knowing the cause, they tried their best to brighten up their old father, but nothing worked. So the eldest took her courage in both hands. “What troubles you, father? Is it something we’ve done? Have your subjects turned against you? Please tell us what is poisoning your old age. To blot out the least of your troubles we would shed our blood. You’re our life, you know that! We will never fail you.”

“Ah, I know that’s true, you three have never disobeyed me; but you can’t help me, my dear children. Little girls! Nothing but girls, alas! Only a boy could get me out of the trouble I’m in. My sweethearts, from childhood on, all you’ve ever learned to handle are spindles and needles: spinning and embroidery are all the tasks you know. Only a hero can save me now – a young man who can whirl a heavy weapon – brandish a sword – gallop at the foe like a dragon at lions!”

His daughters cried out, “What are you hiding from us? Speak!” They threw themselves on their knees before him and the emperor gave in. “My children, this is why I’m sad. When I was young, no one dared touch my empire, but the years have frozen my blood and drunk my strength. My enemies are no longer afraid of me: foreign soldiers will set fire to my roofs and water their horses at my wells. There’s nothing to be done, I must submit to the All-Powerful Emperor, as all other emperors on earth have done before me. But he makes all his vassals send the best of their sons to serve ten years in his court, and I have no sons, only three daughters.”

“So what? I’ll go!” cried the eldest, “I’ll save you!”

“No, poor child, it’s useless!”

“Father, one thing is sure, you shall never be ashamed of me. Am I not a princess, and daughter of an emperor?”

“Very well. Get yourself ready and you may try.”

The gallant girl jumped for joy and rushed to prepare for her journey. She turned coffers upside down and emptied chests, packing enough gold-embroidered garments and fine jewels for a year, with all kinds of provisions. She took the most spirited horse from the royal stables, a splendid steed with fiery eyes, silken mane and silver coat.

When her father saw her armed and mounted, making her horse prance in the courtyard, he gave her the best advice, telling her all kinds of tricks to disguise her true sex and warning her against gossip and indiscretions so that everyone would believe she was a young prince chosen for an important mission. Finally he said, “Go with God, my daughter, and keep my advice tucked safely between your two ears.”

Horse and rider leaped away. The princess’s armour shone like a flash of lightning in the eyes of the stunned guards: she split the wind and was gone in the blink of an eye. And if she hadn’t slowed down for her retinue of boyards and servants, they would have been lost, unable to catch up. But although she didn’t know it, her father the emperor – who was a magician – wished to test her. Hurrying ahead of her, he threw a copper bridge over the way, changed himself into a wolf with fiery eyes, and crouched under the arch. As his daughter came by, the wolf leaped howling from under the bridge, teeth gnashing and rushed at her, as if to tear her apart.

The poor girl’s heart leaped with fright, the horse gave an enormous bound – and in panic she wrenched him around, spurred him away and didn’t stop till she was back at her father’s palace.

The old emperor had got back before her. He came to meet her at the gate and shaking his head sadly, welcomed her with these words, “Didn’t I tell you, my little one, flies can’t make honey?”

“Alas, father, how was I to know that on my way to serve an emperor I would have to fight raging wild beasts?”

“There, stay by the fireside with your needle, and may God have pity on me! He alone can spare me from shame.”

Now the second princess came to ask permission to attempt the adventure, swearing that she would stop at nothing to see it through. She begged so hard that her father let her have her way, and off she went, all armed, followed by her baggage train. But she too met the wolf barring the way at the copper bridge, and returned discomfited just like her older sister. The old emperor received her in the same way in front of the gate and said sadly, “Didn’t I say to you, little one, not every bird can be caught?”

"But father, this wolf was really scary. He opened his jaws so wide he could have swallowed me in one gulp, and his eyes flashed rays of lightning as if to destroy me on the spot!’”

“Then stay by the fireside, embroider cloth and make bread. May God help me!”

But here comes the youngest daughter: “Father, it’s my turn. Let me too try my luck. Perhaps I shall laugh at the wolf!”

“After what happened to the others? You have a nerve, you baby! How dare you talk about laughing at the wolf? You’re hardly old enough to use a spoon!"

The old emperor did everything he could to dissuade her, but it was no good. “For you, father, I’d chop the devil into pieces – or turn devil myself. I feel sure I’ll succeed, but if God is really against me, at least I’ll come back with no more shame than my sisters.”

Her father continued to hesitate, but his daughter coaxed him so sweetly that he was beaten. “Very well, I shall let you go. How much use it will be, we shall see. At least I shall have a good laugh when I see you coming back, head hanging, and staring down at your pretty little slippers.”

“Laugh if you wish, father, I shall not be dishonoured.”

The first thing the girl decided to do was to go to an old, white-haired boyard for advice – and remembering the stories she’d heard of the deeds of her father when he was young, she thought of his warhorse, which reminded her she needed to pick one for herself. So she went to the stables and looked in every stall, with her nose in the air. The best horses and mares in the empire – not one of them pleased her. Finally, after a long search, she found the famous horse of her father’s youth, a hairless, broken-down old nag lying in the straw. The girl gazed at him in pity, unable to move away. Then the horse spoke:

“How sweetly you look at me! If only you’d seen me as I was on the battlefield, when your father and I won glory together! but now I’m old, no one rides me any more. See how dry my coat is? My old master neglects me, but if someone cared for me properly, I’d be better than the ten best horses in the stable.”

“How should you be cared for?” the young woman asked. “Sponge me down morning and evening with rainwater, give me barley boiled in new milk, and most important of all, ginger me up with hot cinders.”

“I’ll do it, if you’ll help me in my plans.” “Mistress, you won’t regret it!”

The princess did everything the magical horse had asked. On the tenth day, a long shiver ran through his hide. He was glossy as a mirror, fat as butter and agile as a mountain goat. Looking joyfully at the young woman, he kicked up his heels and said, “May God bring you happiness and success, for you’ve given me new life. Tell me your plans! Command, and I obey!”

The king’s daughter made ready for the journey. Instead of weighing herself down with a year’s provisions like her sisters, she gathered together some plain, loose-fitting boy’s clothes, underwear and food, with a little money in case she needed it. Then she caught her horse and came before her father. “God and his saints protect you, my dear father, and keep you safe till I return!”

“Bon voyage, my child! Just remember my advice: turn to God in every danger. Only he can bring you aid.” The young woman promised, and off she went.

Now, just as he’d done before, the emperor hurried ahead, flung a copper bridge over the way, and waited. But before she got there, the magical horse warned the princess what tricks her father was up to, and told her how to get out of it with honour.

As soon as she arrived at the copper bridge, the wolf leaped at her – flaming eyes, raging teeth, mouth like an oven, tongue like a firebrand – but the gallant girl spurred her horse and rushed at him, sword flashing – and she would have split him down the middle from nose to tail if he hadn’t recoiled and run away. She wasn’t playing, that girl! Her strength came from God and she was determined to accomplish her task. Then, proud as she was brave, she crossed the bridge. Delighted with her courage, her father took a short cut. At the end of the next day’s march, he threw a silver bridge across the way, turned himself into a lion and lay in wait. But the horse warned his mistress of this trick, too. As soon as she arrived at the silver bridge, out jumped the lion, covered in spiny hair. His teeth were like cutlasses, his claws like knives, and he roared loud enough to uproot forests and make your ears bleed. The princess caught her breath – but she charged the lion, sword raised, and dealt a blow of such force that if he hadn’t twisted aside she would have cut him in quarters. Then she crossed the bridge in a single leap, praising God.

But her father got ahead of her again. Three days’ march ahead he threw a golden bridge over the way, turned himself into a dragon with twelve heads and hid beneath the arch. When the princess came in sight, the dragon leaped into view. His tail clattered and coiled, smoke billowed from his fiery jaws, and his twelve tongues waggled and wove about, covered in bristles. The young woman’s heart nearly failed, but the horse urged her on: she raised her sword, spurred forwards and fell upon the dragon. They fought fiercely for an hour until, striking sideways with all her force, she slashed off one of the monster’s heads. He roared to crack the sky, did three somersaults and disintegrated in front of her, taking on human shape.

Even though the princess had been warned, she could scarcely believe it was her own father, but he embraced and kissed her, saying, “Now I see that you are as brave as the bravest! And you’ve picked the right horse; without him you would have fared like your sisters. Now I believe you will fulfil your mission. Remember my advice, and above all, listen to the horse you’ve chosen.” She knelt for his blessing and they parted.

On she went till she came to the mountains that hold up the roof of the world. Here she came across two genies who’d been fighting to the death for two years, neither one of them managing to overcome the other. Assuming her to be a young hero riding out on adventure, one of them cried, “Hey, Fet-frumos, help me! And I’ll give you a horn which can be heard for a distance of three days journey!”

The other shouted, “No – help me, and I’ll give you my precious horse Sunray!”

The princess quickly consulted her own horse. “Take the last offer,” he advised. “Sunray is my younger brother, and even wiser and more active than myself.” So the princess hurled herself at the other genie and split him in half from the skull to the belly-button.

The genie she’d rescued thanked and embraced her (noticing nothing strange), and together they went to his house so that he could give her Sunray as he’d promised. Here the genie’s mother greeted them, delirious with joy to see her son safe and sound. Hardly knowing how to thank him, she kissed the young champion – and immediately suspected something. Still, she showed ‘him’ to the best chamber – but the princess insisted on tending to her horse first. And in the stables, the horse told her everything she needed to know.

For the old woman was brewing up mischief. She whispered to her son that this handsome young fellow was really a young woman – and just the sort to make him an excellent wife. The genie didn’t believe her. Never! Ridiculous! No mere woman could handle a sword like that. But his mother persisted, and promised to prove it. That evening, at the head of each bed, she placed a magnificent bunch of flowers, enchanted so that it would wither overnight at a man’s bedside, but stay fresh at a woman’s.

During the night, the young woman got up (as the horse had advised), tiptoed into the genie’s bedroom, lifted the already-withered bunch of flowers, and slipped her own still-fresh one into its place, knowing that its beauty would soon fade. She went back to her room, lay down and slept. Early next morning the old woman rushed to her son’s room and found the flowers withered, as she’d expected. Next she went to the girl’s room, and was shocked to find those flowers equally faded. But she still couldn’t believe her guest was a boy.

“Can’t you see?” she said to her son. “What man has so graceful a figure? That blonde hair, those lips as red as cherries, those bright eyes, those delicate wrists and feet? This simply has to be a young noblewoman dressed up in armour!”

So they dreamed up a second test. Next morning the genie took his young friend’s arm and suggested a walk in the garden. He showed off all his flowerbeds, and invited ‘him’ to pick any or all of them. But warned by the horse, and suspecting a trick, the king’s daughter demanded roughly why they were idly discussing flowers, when there was man’s business to be done – the stables to visit, horses to tend? So the genie swore to his mother that their guest was certainly a boy. Yet still his mother obstinately judged otherwise.

For the last test, the genie showed the girl into his armoury, full of rows of scimitars, bayonets, maces and sabres – some plain and simple, others decorated with jewels – and invited her to choose one. The princess looked at them, carefully testing the points and edges. Then like a practised warrior, she thrust into her belt an old rusty Damascus blade, curved like a crescent, and told the genie she was leaving and it was time to give her Sunray. Seeing her choice of weapon, the old woman despaired of ever learning the truth, though she was sure in her own mind of what she’d told her son – that this was a clever and tricky girl. But they had to do as she wished. They went to the stables and gave her the horse, Sunray.

The emperor’s daughter leaped on Sunray’s back and pressed him to run faster and faster. Galloping alongside, her father’s old horse said to her, “Mistress, now you must go on with my young brother. Trust him as you do me. He is like myself, but younger and more vigorous. Sunray can show you what to do in difficult times.” Then with tears in her eyes the girl dismissed her old horse, the horse of her father’s youth.

She journeyed on, when all of a sudden she saw a bright curl of golden hair lying in the road. Pulling Sunray to a halt, she asked if she should pick it up or leave it. Sunray answered, “If you take it you’ll be sorry, but if you don’t take it you’ll still be sorry: so take it.” She picked it up, stuck it into the collar of her tunic and rode on. They went by mountains and valleys, through dark forests and sunny meadows, they passed over springs of fresh water, they came to the court of the All-Powerful Emperor, where the sons of other emperors served him like pages. The Emperor was delighted to see this spirited young prince and soon appointed him as a personal companion. This made the other pages jealous. Spotting the lock of shining golden heir tucked into the collar of his shirt, they went to the emperor and told him that their new companion had been boasting that he knew where Iliane lived, golden Iliane, beautiful Iliane of that song,

Tresses of gold,The fields grow green,The roses blossom…

and that he’d shown them a lock of her golden hair. As soon as he heard that, the All-Powerful Emperor ordered the girl to be called before him. “Fet-Frumos, you’ve deceived me. Why did you hide from me that you know Iliane of the Golden Hair? How did you steal that curl? Bring her to me, or your head will roll where your feet are now. I have spoken.”

All the poor young woman could do was bow and retreat, but when Sunray learned what had happened, he said, “Don’t worry! A genie has kidnapped Iliane, whose golden hair you picked up on the road, and imprisoned her in the Swamps of the Sea. She refuses to marry her kidnapper unless he can round up her stud of mares, which is a dangerous thing to do. Go back to the All-Powerful Emperor and say you need twenty ships, and a cargo of precious goods to put in them. ’ The girl went straight to the emperor. “Son,” said the emperor, “you shall have all of it! But bring me Iliane of the golden hair.”

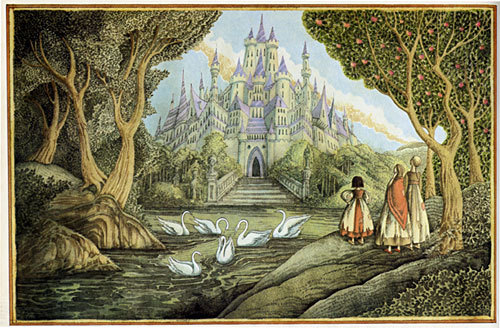

Well, neither wind nor waves delayed them. After a voyage of seven weeks to the Swamps of the Sea, they came to the coast of a beautiful island all covered in revolving palaces, castles which turned around by themselves so as always to face the sun. The emperor’s daughter disembarked, and taking some bejewelled slippers she rode towards the castles on Sunray, where three of the genie’s eunuchs who were guarding Iliane, came to meet her. (The genie was away from home trying to round up Iliane’s mares, leaving only his old mother in charge.) The girl told them she was a merchant who had lost his way in the sea marshes, and had luxury goods to sell.

Now looking from her window, Iliane had spotted the handsome merchant already. Her heart gave a sudden thump at the sight of him, and she persuaded the genie’s mother to let her go down and try on the wonderful slippers. They fitted perfectly, and when the youth told her that his ships held even finer and more precious things, she went on board. While she was looking at all the enchanting merchandise (and exchanging glances with the young merchant) she didn’t notice the shore receding and the sea spreading out over the swamps so far, so far, that soon there was no sign on the horizon of the island and the coast. A good wind blew, the ships flew like seabirds, and beautiful Iliane of the golden hair found herself in the middle of the sea, but did she care? Not when she lifted her eyes to the face of the young merchant who had delivered her from prison.

Nearly had they reached the opposite shore when they saw the genie’s mother rushing after them. Wading over the blue billows, hopping from wave to wave, one foot in the air and the other on the splashing foam, she was almost on their heels, flames streaming from her mouth. The instant the ship touched land they leaped ahore, and the emperor’s daughter threw Iliane up on to Sunray’s back. She leaped up herself, told Iliane to hold to her waist – and away they galloped with the old crone’s breath hot on their shoulders. “I’m scorching!” Iliane cried.

So the emperor's daughter leaned down to the horse and asked him what to do; and Sunray answered, “Reach into my left ear, pull out the sharp stone you’ll find there and throw it behind you!”

The emperor’s daughter did just that. Then all three of them began to race like a hurricane, while behind them in one stroke a rocky mountain rose up to touch the sky. But the genie’s mother flung herself at it, hoisting herself from rock to rock. Look out! Beware!

Twisting around, Ilaine saw her coming. In fright she buried her head in the young merchant’s neck, covering it with kisses and crying out that they would be overtaken. Again the girl bent over the horse’s neck and asked him what to do, for the flames jetting from the witch’s mouth were burning their waists.

“Reach into my right ear, pull out the brush you’ll find there and throw it behind you!”

The emperor’s daughter did just that. Then they ran harder than ever, while behind them sprang up a vast, dark forest, too thick for even the tinest animal to thread its way through. But the crone swung herself through the trees, crushing them, clutching their branches in a burning grip, shoving and shaking their trunks, and after them she came, onwards, onwards, whirling like a tornado.

Iliane saw her coming and, her head buried in the merchant’s neck which in her terror she was now both kissing and biting, she sobbed out her fear of being caught, which was surely now a certainty.

For the last time the girl bent over the horse's neck and asked him what they should do, for the crone was spitting out a column of fire and frizzling the golden hair on their heads. And Iliane was writhing in pain, and Sunray gasped, “Quick, take the ring from Iliane’s finger and throw it behind you!” And this time, up shot a stone tower, smooth as ivory, strong as steel, bright as a mirror, tall enough to crack the sky.

Raging and cursing, the genie’s mother gathered her strength, bent like a bow, and shot herself up to the top of the tower; but she fell through the hole of the ring, which formed the tower’s turret, and couldn’t climb out again; all she could do was cling with her claws to the niches and crannies, with no hope of climbing up or getting out. She did everything she could, she shot out flames for a distance of three hours travel, hoping to grill the fugitives; but barely a spark fell at the tower’s foot where the two lovers were snuggled. And the witch kept puffing out fiery sparks and set fire to the countryside for leagues around, for she could hear her enemies laughing and hugging and taunting her, till in her final rage she crumbled to bits and died. Then the tower bowed gently down to the handsome young merchant, who put his finger through the ring as Sunray had told him, and the high tower vanished as if it had never been there, and there was the handsome girl’s finger with the ring around it. And off they darted like mountain eagles till they came to the imperial court.

The All–Powerful Emperor received Iliane with great respect. He could hardly contain his joy; he fell in love with her at first glance,and decided to marry her. But Iliane was depressed and saddened; she longed to be like other girls who could do as they wished. Why did her fate seem aways to be in the hands of those she disliked – genie or emperor – while her heart was given to the handsome young merchant of the island?

She replied, “Glorious emperor, may you rule your people in honour forever! Alas, I am forbidden even to dream of marriage until someone rounds up my herd of mares and their fierce stallion.”

At this, the All-Powerful Emperor called the warlike girl and gave the order, “Fet-frumos, fetch me this herd of mares, along with their stallion. If you don’t, I will cut off your head.”

“Dread emperor, I kiss your hands. You have put my head in danger already, sending me on a dangerous task, and now you’re giving me another. I see plenty of valiant sons of emperors here, with nothing to do; it would be fairer to send someone else on this errand. What will become of me, where will I find this herd of mares you order me to fetch?”

“How should I know? Ransack heaven and earth if you must, but I’m telling you to do it, and don’t dare to utter a word!”

The girl bowed. Off she went to tell Sunray everything, and the wise horse answered, “Find me nine buffalo hides, cover them in pitch, spread them over my coat and don’t be afraid, for with God’s help you will succeed in this mission; but believe me, mistress, in the end he’s going to play you false.”

[image error]

She did just what the horse had told her and the pair of them set out. It was a long, hard journey, but at last they came to the region where Iliane’s herd of mares was to be found. Here wandered the genie who had stolen Iliane. He thought she was still in his power under strong guard, but since he had no idea how to perform the task she’d set him he spent his time went running here and there after Iliane’s horses, not knowing what saint to call upon for help and generally exhausting himself. When the heroic girl told him that Iliane was gone from the revolving palace and that his mother had died of spite, the genie became fire and flame and flung himself upon her. They fought together till the ground shook and the noise terrified the birds and beasts for twenty leagues around. Finally, with a mighty effort, the girl chopped off her enemy’s head, left the carcase to the crows and magpies, and found the plain where the mares were running.

Sunray now told his mistress to climb a tree and watch what happened. Armoured in the nine buffalo hides, the splendid horse whinnied three times and the whole herd of mares came running to him with their stallion – who was white with foam and roaring in anger. The stallion leapt at Sunray, but with each bite he tore away only a mouthful of buffalo hide, while every time Sunray bit him, he tore away a mouthful of flesh. When the stallion sank down, bleeding and conquered, Sunray hadn’t suffered a scratch, but his buffalo-hide armour hung in tatters. Then the emperor’s daughter came down from her tree, mounted him and led the herd away to the All-Powerful Emperor’s court, where Iliane came and called all of the mares to her by their names. And as soon as he heard her voice, the wounded stallion was healed and looked as fine as he had before, without even the tiniest scar.

Iliane now told the All-Powerful Emperor he must have her mares milked, so that he and she could be betrothed by bathing in their milk. Yet who could do this? The mares kicked fiercely at anyone who came near; even a single kick could cave in your chest, and no one could touch them. The Emperor ordered ‘Fet-Frumos’ to get on with it and do the job.

The emperor’s daughter felt a darkness in her soul. Was she always to be given the hardest tasks? She would collapse under the strain if this went on! Fervently she prayed God to help her, and since she was pure in both body and soul, her prayer was answered. It began to rain – the sort of rain that comes down in buckets. Water rose as high as the mares’ knees, froze to ice as hard as stone and locked their legs in place. The girl thanked God for this miracle and began milking the mares as if she had been doing so all her life.

But by now the All-Powerful Emperor was almost dying of love for Iliane. He kept staring at her the way a child stares at a tree covered in ripe cherries, but she used all kinds of tricks to put off the day of their marriage. Finally running out of ideas, she said, “Gracious emperor, you have granted my wishes, but I would like one little thing more, after which we shall be married. Get me the flask of holy water which is kept in a little chapel beyond the river Jordan. Then I will become your wife.”

The All-Powerful Emperor summoned Iliane’s rescuer and said, “Go, Fet-Frumos, and don’t come back without the flask of holy water, or I will cut off your head.”

The young woman withdrew with a heavy heart, but when Sunray heard what had happened he said, “Dear mistress, here is the last and hardest of your tasks. Keep up your faith in God! Time is nearly up for this wicked and abusive emperor. The flask of holy water stands on an altar in a little chapel guarded by nuns, who sleep neither night nor day. However, from time to time a hermit visits them, to instruct them in holy things. A single nun remains on guard while they listen to his words, so if we can pick that very moment, all will be well. If not, we’ll have plenty of time to regret it.”

Away they rode. They passed over Jordan river and came to the chapel just moments after the hermit had arrived and called the nuns to chapter. A single nun remained on guard, but the hermit’s lesson went on for so long that, tired out by the endless watch, she lay down over the threshold and went to sleep.

Soft as a cat, the emperor’s daughter stepped over the the sleeping nun. Stealthily she lifted up the holy flask, leaped on her horse and galloped away! The clatter of Sunray’s hoofs woke the nun. She saw the flask was gone and began to wail and cry. The other nuns came rushing. Seeing the rider disappearing at top speed and realising there was nothing to be done, the hermit fell on his knees and called down a curse upon the thief: “Thrice holy Lord, grant that the wretched knave who has stolen the holy flask of thy baptismal water may be punished! If it is a man, may he become a woman! – or it is a woman, may she become a man!”

But see how the hermit’s prayer was answered! When the emperor’s daughter suddenly felt herself a gallant boy in both body and soul, just as she had always seemed, she was neither astonished nor upset. In fact, the thoughts of this new he flew straight to Iliane… Delighted with the transformation, hardier and bolder than ever, the youngster returned to the All Powerful Emperor’s court and handing the flask over, said, “Mighty emperor, I salute you. I have completed all the tasks you set me; I hope this will be the last of them. Be happy then, and reign in peace, as you hope to receive mercy from our Lord!”

“Fet-frumos, I am pleased with your services! After my death you shall succeed me on the throne, as up till now I have had no heir. But if God gives me a son, you shall be his right hand,” the Emperor replied.

But Iliane Goldenhair was very angry that this last wish of hers had been fulfilled. She decided to take revenge on the Emperor for always handing the hardest tasks to the invincible young hero she loved. She thought that if her royal admirer was sincere he ought to have fetched the flask of holy water himself. So she ordered a bath of her mares’ milk to be heated, and asked the All-Powerful Emperor to bathe in it with her – he agreed with delight. Once they were in the bath together, she had the stallion from her herd brought in to blow cool air on them. At her signal, the stallion blew cool air upon Iliane through one nostril – and through the other he blew a blast of red-hot air at the All-Powerful Emperor. It was so fierce it charred him to the bone, and he fell back dead.

There was great confusion in the land at the strange death of the All-Powerful Emperor! From all sides they assembled, crowds ran to witness his magnificent funeral. After that, Iliane said to the youth,

“You brought me here, Fet-Frumos: you rounded up my herd of mares with their stallion and all the rest, you killed the genie, and the witch his mother, you brought me the flask of holy water from beyond the Jordan. My life and love belong to you. Be my husband! Let us bathe together and marry!"

“Yes, I’ll marry you, because I love you and you love me,” the youth answered in a voice just as soft as when he was a girl, “but know that in our house, the cock will crow and not the hen…” And guess what? Just because he was a man now, he added, “I’ll have my way!” So they were married, and reigned with justice and in the fear of God, protecting the poor, maltreating no one, and if they haven’t died yet, he and Iliane are reigning still.

And I was there at the wedding, indeed I was! I stood around gaping at all of the parties, for nobody dreamed of offering me a chair. So what did I do?

I sat on my saddle like any old farmer And I told you the story of the princess in armour.

More about fairy tales and folklore in my book "Seven Miles of Steel Thistles" available from Amazon here and here.

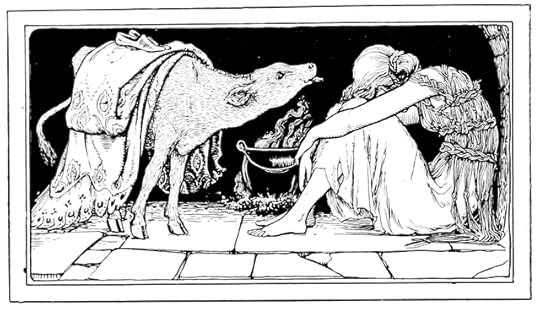

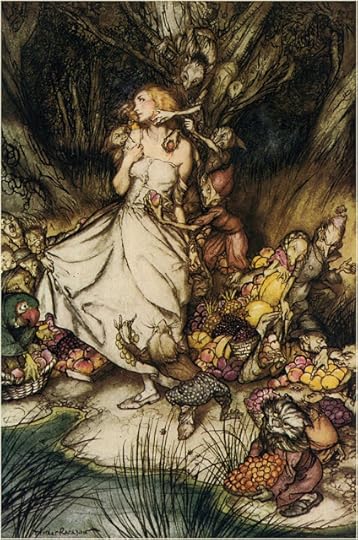

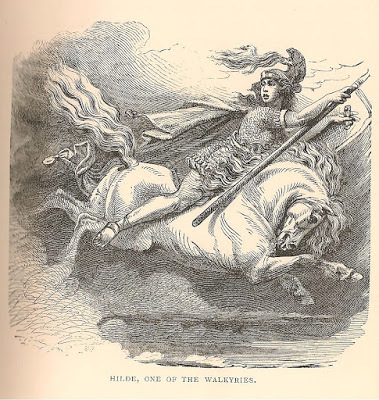

Picture credits:The Princess Charges the Lion, by H J Ford, illustration for The Violet Fairy Book

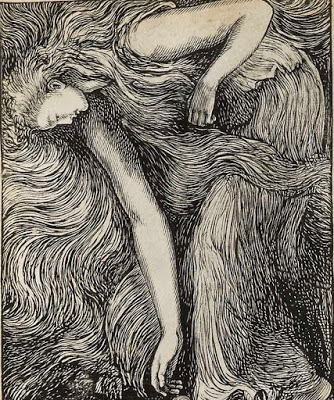

The Valkyrie Lagerta, by Morris Meredith Williams, 1913

Published on March 10, 2020 03:38

March 3, 2020

Strong Fairy Tale Heroines #2: THE THREE SISTERS

THE THREE SISTERS

This haunting story is a Romany tale collected and translated by John Sampson (1862 – 1931). Sampson was a self-taught linguist, scholar and printer, and librarian of University College, Liverpool. On a walking tour near Bala in the late 1900s he encountered and was befriended by members of the Wood clan, descendents of the eighteenth century ‘King of the Gypsies’ Abram Wood, and speakers of Welsh-Romani: ‘a quite pure, inflected Romani dialect’ which became his principal study. Edward’s brother Matthew, and his four sons, told Sampson many folktales some of which were published by the Gypsy Lore Society.

“The Three Sisters” is a tale bathed in a sinister half-light as one after another, the sisters journey to the land ‘where the devil never wound his horn and the cock never crew,’ and white stones glimmer in an eternal dusk. The old woman in the red cloak and her brother in the red jerkin are clearly powerful fairies – red is a dangerous, fairy colour – and the gate leading to the hill, through which each has to pass, suggests it is an entrance to the Otherworld. At the end of the story, the youngest sister triumphs because she has, significantly, taken the initiative from the fairy man by speaking to him first, which enables her to ignore the cries of the white stones. She then supplants the woman in the red cloak as ruler of the fairy kingdom but still takes care to address her as 'good aunt': she has learned that you shouldn't offend the fair folk.

This tale and others can be found in “XXI Welsh Gypsy Tales” by John Sampson, (Gregynog Press, 1933)

There was a cottage, and there lived in this cottage an old man and his wife. They had three children, and these children were three little sisters. And they dwelt there summer after summer until their father and mother died.

And two summers after their father and mother died, there came to the cottage a little old woman who wore a red cloak. And she went to the door and begged for a cup of tea. “No,” said the eldest sister, “we have not enough for ourselves.” “I will bind thy head and thine eyes, if I bind not thy whole body,” said the crone to her. With that she departed.

And now these three sisters grew poor. And one day the eldest sister said to the two others, “I am going to seek work somewhere. And do you three stay here to look after the house. But if ye see the spring dried up and blood in the ladle, some evil has befallen me. Come then, one of you, in search of me.” And so in the morning when they arose they used to look for the tokens of which their elder sister had spoken.

Let us leave the two younger sisters for a while and follow the eldest one.

The eldest sister journeyed to where the devil never wond his horn and the cock never crew. Night fell. Presently she saw a little man in a red jerkin. This little red-jerkined fellow was brother to the old woman of the red cloak. And before the girl asked aught of him, he put a question to her. “Art thou seeking work?” “Yes,” replied the girl.

Little Red Jerkin gave her no hint of the trial that lay before her. He opened a gate. “Go up there and thou wilt get work!”

And up she climbed. There were little white stones all the way up the hill. “Stop and look!” cried one white stone. The girl stopped and looked at the stone. She was bewitched into a trance and transformed into a white pebble. Thus did old Red Cloak bind her head and her eyes with a spell. And now she has bound her whole body.

Let us leave her there and return to the two younger sisters.

One morning the second sister arose and ran to the door to look. She opened the door and there was the spring dried up and blood in the ladle. Horror overwhelmed her when she beheld these things. “Some evil has befallen my sister,” she cried to the youngest girl. Then the spring flowed and the ladle was bright again. Now she, in her turn, said to her younger sister, “If thou seest the spring dried up and blood in the spoon, some misfortune has overtaken me. Come then and seek for me.”

Let us leave the youngest girl now and follow her who set out in search of the eldest sister.

She journeyed to where the devil never blew his horn and the cock never crew, until she met this same man in the red jerkin. And before she could utter a word to him, Red Jerkin spoke. “Art thou looking for work?” asked he. “No,” answered the girl, “I am looking for my sister.” “Thy sister is up yonder; she has found work, and is doing well.”

The gate was opened and the girl climbed the hill. “Stop!” cried one white stone. The girl did not pause, but went straight on. “Look!” called another stone. The girl went on. “Lo! here is thy sister,” cried a third stone. She stood still and looked around when she heard this news about her sister. And she was bewitched into a magic trance and transformed into a white pebble.

Let us return now to the youngest sister who was at home.

She arose one morning and went to the door and opened it. There was no water in the spring; it was dried up. There was blood in the ladle! Then the youngest sister burst into tears.

But she had more spirit than the other two. She knew not where they had gone, she knew not where to seek them. So, after making fast the door, she took the road on which she had seen her sisters set out.

And she journeyed to where the devil never wound his horn and the cok never crew, until she met the little fellow in the red jerkin. Before he could open his mouth, the youngest sister spoke to him. She got in the first word. She asked him about work. “Yes, there is work for thee.” His heart was well-nigh broken, because the maiden had got in the first word.

He opened the gate and the girl climbed the hill. As she climbed, one white stone called to her, “Stop!” The girl went on. “Look!” cried a second stone. “This is the place!” cried a third stone. The maiden was quite fearless. She paid no heed to them. “Lo! here are thy two sisters,” cried yet another stone.

“Kiss them, then,” quoth she. And on she sped until there were no more stones and she reached the little old woman in the red cloak.

When Red Cloak saw the girl she fell on her knees. “Hast thou found me then, little lady?” “I have,” quoth the little lady.

And now, lo and behold! all that slumbrous spell was broken. And all these white stones were restored to their former shapes. It was this maiden who had broken the whole enchantment: the dear God had put in into her heart to achieve all this and to have no fear.

And she went to her two sisters and led them up to the old woman in the red cloak. “Here are my tow sisters,” said she. “I know them,” answered Red Cloak. “but it is thou who art mistress here now. All is left in thy hands. Do as thou wilt.” “I thank thee, good aunt.”

Red Cloak showed the youngest sister where all the treasure was. Then the girl gave her two sisters a bagful each, and charged them to send her word if any mischance should ever again befall them. And they both fell on their knees before their youngest sister. They were escorted home.

And she became the greatest lady in all that land, far and wide, and she married Red Jerkin. And they live there happily to this day.

More on fairy tales and folklore in my book "Seven Miles of Steel Thistles" available here and here.

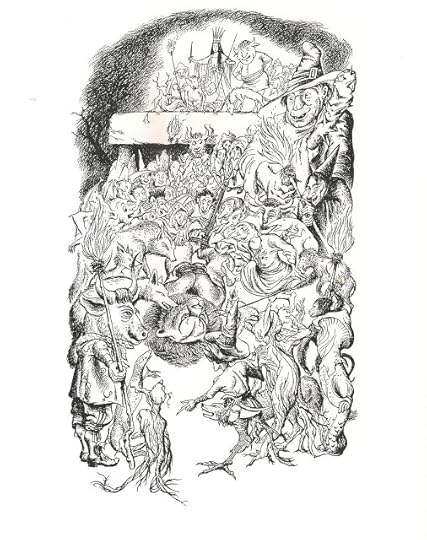

Picture credits:Details from 'The Fairy Feller's Master Stroke' by Richard Dadd

Published on March 03, 2020 02:46

February 25, 2020

Strong Fairy Tale heroines #1: SIMON AND MARGARET

SIMON AND MARGARET

This tale was told in the 1880s by Gaelic-speaking Michael Faherty of Renvyle in Connemara, Co Galway to William Hartpole Lecky, who wrote it down verbatim; it was then translated by Irish poet William Larminie for his collection ‘West-Irish Folk Tales (1893). Larminie was a careful and responsible collector who took down most of his tales in person. He not only names his sources but gives brief descriptions of them: 'Michael Faherty,' he says, 'was when I first made his acquaintance, a lad of about seventeen. He ... lived with his uncle, who had, or has still, a small holding... and who was also a pilot and repairer of boats.' Unlike many 19th century collectors Larminie did not attempt to improve or embellish the stories he was told; he was so conscientious that his collection even includes one unfinished tale, with a note to explain that the storyteller had forgotten the ending!

In this complete tale, the heroine Margaret follows her married lover Simon to sea, only to be cast overboard like Jonah when the ship is threatened by a female sea serpent with a great dislike of the Irish... It's easy to inagine this story being told aloud: deadpan and deceptively naïve, with elisions, sudden surprises and touches of sly humour. We hear how the two lovers are reunited, how the level-headed Margaret saves Simon by fighting the giant of the White Doon, and how in spite of his attempt to take credit for the victory, he's forced to admit that she was the one who did it.

Long ago there was a king’s son called Simon, and he came in a ship from the east to Eire. In the place where he came to harbour he met with a woman whose name was Margaret, and she fell in love with him. And she asked him if he would take her with him on the ship. He said he would not take her, that he had no busines with her, “for I am married already,” said he. But the day he was going to sea she followed him to the ship, and such a beautiful woman was she, that he said to himself that he would not put her out of the ship, “but before I go further I must get beef.” He returned back and got the beef. He took the woman and the beef to the ship and ordered the sailors to make everything ready that they might be sailing on the sea.

They were not long from land when they saw a great bulk making towards them, and it seemed to them that it was more like a serpent than anything else whatever. And it was not long before the serpent cried out, “Throw me the Irish person you have on board.”

“We have no Irish person in the ship,” said the king’s son, “for it is foreign people we are; but we have meat we took from Eire, and, if you wish, we will give you that.”

“Give it to me,” said the serpent, “and everything else you took from Eire.”

He threw out a quarter of the beef, and the serpent went away that day, and on the morrow morning she came again, and they threw out another quarter, and one every day till the meat was gone. And next day the serpent came again, and she cried out to the king’s son, “Throw the Irish flesh out to me.”

“I have no more flesh,” said the prince.

“If you have no flesh, you have an Irish person,” said the serpent, “and don’t be telling your lies to me any longer. I knew from the beginning you had an Irish person in the ship, and unless you throw her out to me, and quickly, I will eat up yourself and your men.”

Margaret came up, and no sooner did the serpent see her than she opened her mouth, and put on an appearance as if she were going to swallow the ship.

“I will not be guilty of the death of you all,” said Margaret; “get me a boat, and if I go far safe it is better, and if I do not, I had rather I perished than the whole of us.”

“What shall we do to save you?” said Simon.

“You can do nothing better than put me in the boat,” said she, “and lower me on the the sea, and leave me to the will of God.”

As soon as she got on the sea, no sooner did the serpent see her than she desired to swallow her, but before she reached as far as her, a billow of the sea rose between them, and left herself and the boat on dry land. She saw not a house in sight she could go to. “Now,” she said, “I am as unfortunate as ever I was. This is no place for me to be!” She arose and began to walk, and after a long while she saw a house a good way from her. “I am not as unfortunate as I thought,” said she. “Perhaps I shall get lodging in that house tonight.” She went in, and there was no one in it but an old woman who was getting her supper ready. “I am asking for lodging till morning.”

“I will give you no lodging,” said the old woman.

“Before I go further, there is a boat there below, and it will be better for you to take it into your hands.”

“Come in,” said the old woman, “and I will give you lodging for the night.”

The old woman was always praying by night and day. Margaret asked her, “Why are you always saying your prayers?”

“I and my mother were living a long while ago in the place they call the White Doon, and a giant came and killed my mother, and I had to come away for fear he would kill myself; and I am praying every night and every day that some one may come and kill the giant.”

The old woman owns a ring, which will only fit the finger of the one destined to kill the giant. Simon’s wife and his brother Stephen arrive together to kill the giant, but the ring will not fit Stephen’s finger, and the giant slays them both. At last, Simon himself arrives at the old woman’s house.

The next morning there came a gentleman and a beautiful woman to the house, and he gave the old woman the full of a quart of money to say paternosters for them till morning. The old woman opened a chest and took out a handsome ring and tried to place it on his finger, but it would not go on. “Perhaps it would fit you,” said she to the lady. But her finger was too big.

When they went out, Margaret asked the old woman who were the man and woman.

“That is the son of a king of the Eastern World, and the name that is on him is Stephen, and he and the woman are going to the White Doon to fight the giant, and I am afraid they will never come back; for the ring did not fit either of them; and it was told to the people that no one would kill the giant but he whom the ring would fit.”

The two of them remained during the night praying for him, for fear the giant would kill him; and early in the morning they went out to see what had happened to Stephen and the lady that was with him, and they found them dead near the White Doon.

“I knew,” said the old woman, “this is what would happen to them. It is better for us to take them with us and bury them in the churchyard.”

About a month after, a man came into the house, and no sooner was he inside the door than Margaret recognised him.

“How have you been ever since, Simon?”

“I am very well,” said he; “it can’t be that you are Margaret?”

“It is I,” said she.

“I thought that billow that rose after you, when you got in the boat, drowned you.”

“It only left me on dry land,” said Margaret.

“I went to the Eastern World, and my father said to me that he sent my brother to go and fight with the giant, who was doing great damage to the people near the White Doon, and that my wife went to carry his sword.”

“If that was your brother and your wife,” said Margaret, “the giant killed them.”

“I will go on the spot and kill the giant, if I am able.”

“Wait while I try the ring on your finger,” said the old woman.

“It is too small to go on my finger,” said he.

“It will go on mine,” said Margaret.

“It will fit you,” said the old woman.

Simon gave the full of a quart of money to the old woman, that she might pray for him till he came back. When he was about to go, Margaret said, “Will you let me go with you?”

“I will not,” said Simon, “for I don’t know that the giant won’t kill myself, and I think it too much that one of us should be in his danger.”

“I don’t care,” said Margaret. “In the place where you die, there am I content to die.”

“Come with me,” said he.

When they were on their way to the White Doon, a man came before them.

“Do you see that house near the castle?” said the man.

“I see,” said Simon.

“You must go into it and keep a candle lighted till morning in it.”

“Where is the giant?” said Simon.

“He will come to fight you there,” said the man.

They went and kindled a light, and they were not long there when Margaret said to Simon, “Come, and let us see the giants.” [There are baby giants as well as the old one.]

“I cannot,” said the king’s son, “for the light will go out if I leave the house.”

“It will not go out,” said Margaret; “I will keep it lighted till we come back.”

And they went together and got into the castle, to the giant’s house, and they saw no one there but an old woman cooking; and it was not long till she opened an iron chest and took out the young giants and gave them boiled blood to eat.

“Come,” said Margaret, “and let us go to the house we left.”

They were not long in it when the king’s son was falling asleep. Margaret said to him, “If you fall asleep, it will not be long till the giants come and kill us.”

“I cannot help it,” he said. “I am falling asleep in spite of me.”

He fell asleep, and it was not long till Margaret heard a noise approaching, and the giant cried from outside for the king’s son to come out to him.

“Fum, far, faysogue! I feel the smell of a lying churl of an Irishman. You are too great for one bite and too little for two, and I don’t know whether it is better for me to send you into the Eastern World with a breath or put you under my feet in a puddle. Which would you rather have – striking with knives in your ribs or fighting on the grey stones?”

“Great, dirty giant,” said Margaret, “not with right or rule did I come in, but by rule and by right to cut your head off in spite of you, when my fine silken feet go up, and your big, dirty feet go down.”

They wrestled till they brought the wells of fresh water up through the gray stones with fighting and breaking of bones, till the night was all but gone. Margaret squeezed him, and first squeeze she put him down to his knees, the second squeeze to his waist, and the third squeeze to his armpits.

“You are the best woman I have ever met. I will give you my court and my sword of light and the half of my estate for my life, and spare to slay me.”

“Where shall I try your sword of light?”

“Try it on the ugliest block in the wood.”

“I see no block at all that is uglier than your own great block.”

She struck him at the joining of the head and the neck, and cut the head off him.

In the morning when she wakened the king’s son, “Was not that a good proof I gave of myself last night?” said he to Margaret. “That is the head outside, and we shall try to bring it home.”

He went out, and was not able to stir it from the ground. He went in and told Margaret he could not take it with him, that there was a pound’s weight in the head. She went out and took the head with her.

“Come with me,” he said.

“Where are you going?”

“I will go the Eastern World, and come with me till you see the place.”

When they got home, Simon took Margaret with him to his father the king.

“What has happened to your brother and your wife?” said the king.

“They have both been killed by giants. And it is Margaret, this woman here who has killed them.”

The king gave Margaret a hundred thousand welcomes, and she and Simon were married - and how they are since then, I do not know!

Find more about fairy tales and folklore in my essays "Seven Miles of Steel Thistles" available from Amazon here and here.

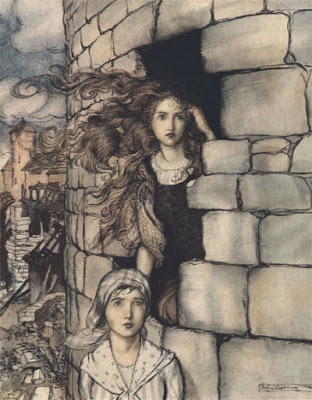

Picture credits:

'Leviathan' by Arthur Rackham

Illustration by Arthur Rackham to 'The Manuscript Found in a Bottle' by Edgar Allen Poe

Published on February 25, 2020 02:08

February 18, 2020

Strong Fairy Tale Heroines: a series!

In 2013 Disney released the story of two princesses: Elsa, with power over ice and snow, and her young sister Anna. When Elsa’s magic accidentally strikes frost into her sister’s heart, the film plays on our expectation that a prince’s kiss will save Anna. Instead, in a feminist twist, the spell is broken by sisterly love and courage while romance is sidelined. It seemed utterly fresh and exciting. 'Inspired by' rather than 'based upon' Hans Andersen's 'The Snow Queen', 'Frozen' wowed children and parents worldwide and became the highest-grossing animated film of all time.

Why was 'Frozen' so successful? It satisfied the hunger of a modern audience keen to identify with strong heroines. Why did the focus on Anna and Elsa seem so unusual? Because there is a persistent misconception that fairy tale heroines are passive. People who may not have read a fairy tale in years recall Snow-White in her glass coffin or Cinderella weeping in the ashes, and assume they stand for all. A discussion on BBC Radio 4’s The Misogyny Book Club (back in December 6 2015) dismissed the entire genre as projecting images of insipid princesses whose role is to lie asleep in towers waiting for princes to rescue them with ‘true love’s kiss’. Fairy-tale fans on Twitter and Facebook erupted, posting examples of tales featuring strong heroines: even so, a relatively small handful of titles kept recurring. There are many, many more.

It would be astonishing if the thousands of traditional tales told across Europe didn’t include characters who could appeal to and satisfy the desire of women as well as men for action and adventure. And of course, they do. In the Grimms’ fairy tales alone, there are more than twice as many heroines who save princes, as there are heroes who save princesses. In fact, taking the collected Grimms’ tales as an example, and discounting the hundred or so which are animal tales, nonsense tales, religious fables and so on, about half of the remaining stories contain main or prominent female characters who rescue brothers or sweethearts, save themselves and others and win wealth and happiness.

This is less surprising when you remember that whether male or female, fairy-tale protagonists are generally underdogs – orphans, simpletons, the youngest child or step-child, whose success is achieved by other means than strength. The major cause of any protagonist’s success is some sort of magical assistance gained by kindness, innocence, quick wits or luck. Not only does this put the sexes on an equal footing, but several heroines have the added advantage of being magic-workers themselves, a skill few heroes possess.

How has this gone unnoticed? Because a long-standing process of social and editorial bias has favoured and raised to prominence the handful of fairy tales we recognise as ‘classic’. When we think of Cinderella’s glass slipper, fairy godmother, pumpkin coach and passive, gentle heroine, we’re thinking of Charles Perrault’s literary version of the story, written to amuse a seventeenth century salon. The Grimms’ version contains none of these elements. Their Cinderella – Aschenputtel – is a girl with her own mind and her own agenda. Her power comes from a magical tree she plants on her mother’s grave: she runs, jumps, climbs and gets her own back on those who have mistreated her. Yet Perrault’s version is the best known, the one found in most picture books for children, the one adapted by Walt Disney for the cartoon and the more recent film.

Seventeenth century writers like Giambattiste Basile, Charles Perrault, Madame d’Aulnoy and others transformed nursery and folk tales into a sophisticated literary art form for the amusement of genteel audiences. Yet Perrault’s conscious, arch rendering of ‘Cinderella’ is certainly not less authentic than the version the Grimm brothers patched together more than a century later ‘from three stories current in Hesse’ which all had different beginnings and endings. In fact, both versions are literary: the search for authenticity is vain. Driven by Romantic taste and nationalist motives, the Grimms touched up or wholly rewrote many of the fairy tales they collected, looking to achieve an apparently artless, pure style which would represent the true voice of ‘the folk’. To them we owe the ‘fairy tale’ we recognise today: a construct, but an extraordinarily powerful one.

Inspired by the Grimms, nineteenth century collectors from Russia to Ireland, from Norway to Romania turned to their own peasantry to record and improve traditional tales in the mould of the Kinder- und Hausmärchen. In the process they not only uncovered but contributed to what Joseph Campbell has called the ‘homogeneity of style and character’ of the European fairy tale. And from the nineteenth century on, social and moral gatekeepers have preferred the docile charm of Perrault’s heroine to the energy and wild magic of the Grimms’. Most of the famous fairy tales are those whose heroines display the qualities Victorian gentlemen most wished to see in women: gentleness, beauty and passivity. Sir George Dasent who translated the Norwegian tales collected by Asbjørnsen and Moe recognised the strength of Tatterhood or the Mastermaid, but he preferred heroines of ‘the true womanly type’. Surprise, surprise.

And so to illustrate the vitality and strength of the neglected heroines within the classic European fairy tale tradition, from next week I’m beginning a series of new posts. In each, I will introduce a fairy tale with a strong heroine, which can then be read in full. Most of the stories I’ve chosen have been been in print for well over a hundred years, available to everyone, yet most are unknown to the general public. Tatterhood, Lady Mary and the Mastermaid are not household names like the Sleeping Beauty and Snow-White. And ‘The Woman who Went to Hell’ and Margaret, from ‘Simon and Margaret’ are likely to be new even to the most die-hard of fairy tale enthusiasts. At least I think so! I hope there’ll be surprises for everyone.

Of course it’s been done before, notably by Angela Carter. Her seminal collections of folk and fairy tales for Virago in 1990 and 1992 (republished as ‘Angela Carter’s Book of Fairy Tales’, 2005) present a wonderfully diverse selection, a kaleidoscope of different story forms from a worldwide range of cultures and featuring women in all kinds of roles, ‘clever, or brave, or good, or silly, or cruel, or sinister’. She sets a characteristically bold, adult tone for the anthology, opening with a brief Inuit tale about the powerful woman, Sermerssuaq, whose clitoris is so big ‘the skin of a fox would not wholly cover it’. Though striking, this seems to be a tall tale rather than a fairy tale, and one of several which are not easy to interpret. Is Sermerssuaq human, shaman, some kind of goddess? Does she figure in other Inuit stories? Carter’s collection is dazzling, but includes a number of tales which, divorced from their cultural context, we are in danger of reading as exotic oddities.

Fables, cautionary tales, tall tales and jokes are forms intended to deliver a single, memorable point: a warning, a lesson or a laugh. They sometimes fail today because we reject the message (a hen-pecked man asserting himself by beating a bossy wife, for example), and they offer nothing more. By contrast, I take the classic fairy tale to be an adventure story: a sequence of marvellous events occurring to a single main character, or perhaps to a pair of lovers or siblings; and it’s the adventure, not the conclusion, which is important. Though the good usually achieve happiness while the wicked are punished, fairy tales have no didactic intention and no single message. Rather, like poetry, they generate an emotional and interpretative response.

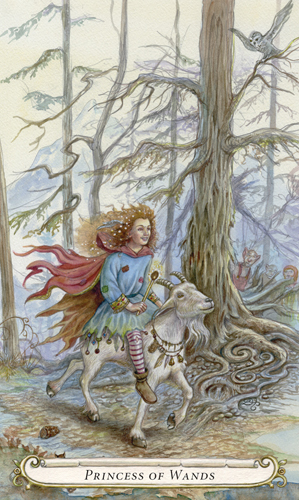

For the purposes of this series I’ll be using the word ‘heroine’ to mean more than ‘main character’: it will indicate someone whose actions and qualities deserve admiration or respect. This might rule out characters like Rapunzel. She’s certainly the protagonist, but the best we can feel for her is pity. Or is it? Look more closely even at that story, and we remember that the prince fails spectacularly to rescue her, and she restores his sight: some of the most passive heroines have more about them than you might suppose. But there is no need for special pleading when so many fairy tales across Europe celebrate active, courageous young women who seize control of their own destinies. How about the heroine of a Romanian tale who sets off in armour on her war-horse to save her father’s honour? Hailed as a hero, she fights dragons and genies, and ultimately rescues and marries another princess, Iliane Goldenhair. The heroine of an Irish fairy tale ‘Simon and Margaret’ fights and kills a giant while her lover sleeps. The flamboyant heroine of the Norwegian ‘Tatterhood’ drives off trolls and witches as she gallops about on a goat. And when brothers and sisters adventure together, it is nearly always the sisters who do the rescuing, not the other way around.

Even the heroes of fairy tales rarely make their way by force. A good heart is more use than a sword. Kindness to animals or old women is rewarded by valuable advice or magical assistance: and where heroes rely on others, heroines often possess their own magical powers. The young peasant girl Bellah of the Breton story ‘The Groac’h of the Isle of Lok’ uses her magic skills to rescue her sweetheart from an enchantress. The giant’s daughter of the ‘The Battle of the Birds’ and the eponymous Mastermaid save their hapless lovers by conjuring up whole catalogues of magical ruses and illusions.

Female intelligence is valued, too. The fiery Scottish heroine Maol a Chliobain uses both magic and sharp wits to trick a giant, while the peasant girl in ‘The Peasant’s Wise Daughter’ is clever enough to save her father and marry a king – whom she later kidnaps in order to teach him a much-deserved lesson. Finally, quietly determined heroines also deserve admiration: the ones who trek stubbornly over glass mountains and wear out iron shoes, the ones who win through by their resolute endurance. Renelde in the Flemish tale ‘The Nettle Spinner’ rejects the advances of her rich overlord and brings about his death by patiently weaving him a nettle shroud. ‘The Woman Who Went to Hell’ endures seven years in Hell and outwits the Devil to bring her lover, an Irish peasant boy, back from the dead. And Maid Maleen survives seven years’ imprisonment in a dark tower, chipping her way out through the wall. All these heroines are brave and not one of them needs rescuing by a man: but fortitude is also courage, historically perhaps particularly the courage of women, and it’s underestimated.

Finally, fairy tales are not romances. In spite of the Disney song ‘One day my prince will come’, ‘Snow-White’ is not a love story. It’s a tale of a cruel queen, a lost child, a dark forest, a magic mirror. The arrival of the prince at the end is no more than a neat way to wrap the story up. Not every fairy tale ends in a marriage, and when they do, something more hard-headed is usually going on. Few fairy tale heroines are princesses by birth. Most are the daughters of merchants, millers, woodcutters or even giants; they are orphans, peasants and servant-girls – the same kind of people who told the tales in the first place, and who prized financial security. Marriage-with-the-prince (or princess) combines wealth and high status in an easily-grasped symbol, and indicates that a person’s endeavours have lifted them to the top of the social heap. I’ve said this elsewhere, but it’s significant that the disapproval directed at heroines who marry princes never seems to be aimed at the many heroes who marry princesses. All those tailors, pensioned-off soldiers, youngest sons and simpletons – no one seems to have any trouble recognising, in their tales, a royal marriage as a metaphor for well-deserved worldly success.

Fairy tales continue to pervade popular culture. Besides Frozen, in the last few years Walt Disney Studios has released Tangled (2010), Maleficent (2014), Into the Woods and Cinderella (2015), Maleficent 2 (2019), a live-action film of Beauty and the Beast ( 2017), and Frozen II (2019). Universal has released Snow White and the Huntsman (2012) and its sequel The Huntsman (2016). More are bound to follow, but it’s a pity that most of these films are based upon the same few well-worn tales – about a girl locked in a tower, a girl who sleeps for a hundred years, a girl who has to marry a Beast, and a girl in a glass coffin. Perhaps I’m not being entirely fair here, but that’s the gist. In the effort to turn these modest heroines into something feisty enough to appeal to 21st century audiences, scriptwriters have gone so far as to transform the wicked fairy of ‘Sleeping Beauty’ into the central, sympathetic character. It was ingenious and successful… but there is plenty more choice out there.

Picture credits:

Mollie Whuppie, by Errol le Cain

Cinderella, silhouette, by Arthur Rackham

Tatterhood, Princess of Wands, from The Fairy Tarot by Lisa Hunt

Bellah finds the Korandon, by HJ Ford

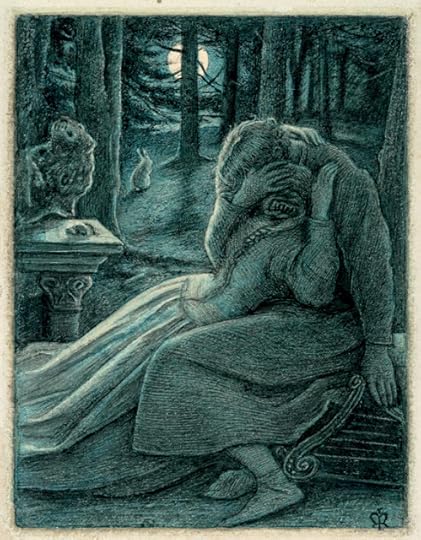

Maid Maleen by Arthur Rackham

Snow White by Benjamin Lacombe

Published on February 18, 2020 07:27

February 9, 2020

Our Craft or Sullen Art

IN MY CRAFT OR SULLEN ART

In my craft or sullen art

Exercised in the still night

When only the moon rages

And the lovers lie abed

With all their griefs in their arms,

I labour by singing light

Not for ambition or bread

Or the strut and trade of charms

On the ivory stages

But for the common wages

Of their most secret heart.

Not for the proud man apart

From the raging moon I write

On these spindrift pages

Nor for the towering dead

With their nightingales and psalms

But for the lovers, their arms

Round the griefs of the ages,

Who pay no praise or wages

Nor heed my craft or art.

Dylan Thomas

When I was a girl I used to memorise poems. I could get drunk on words, mutter them under my breath while waiting for buses, chant them aloud in woods or on windy hills where no one would hear me, murmur them at night, poem after poem, to send myself sliding away on a raft of poetry down a river of dreams. Actually I still do.

Dylan Thomas’s poems are incantations that fill the mouth and roll off the tongue like thunder:

Altarwise by owl-light in the halfway house

The gentleman lay graveward with his furies…

Whatever does it mean? I have no idea, but it sounds good. Better than good! Grand – restorative – like the crashing chords of a cathedral organ; like wonderful spells. I remember suddenly reciting ‘And death shall have no dominion’ to my ten year-old nephew:

Dead men naked they shall be oneWith the man in the wind and the west moon,Though the bones be picked clean and the clean bones goneThey shall have stars at elbow and foot: Though they go mad, they shall be sane;Though they sink through the sea they shall rise again;Though lovers be lost, love shall not:And death shall have no dominion.

His eyes opened wide and he said, ‘Wow!’

Back in the 1970's, there was quite a fashion for obscure poetry; almost every glam-rock album could do the mysteriously evocative stuff. Look at the lyrics of early Genesis under the aegis of Peter Gabriel:

Coming closer with our eyes, a distance falls around our bodies,Out in the garden, the moon shines very bright,Six saintly shrouded men walk across the lawn slowlyThe seventh walks in front, with a cross held high in hand…

In either case – Thomas’s poems or Gabriel’s lyrics – I wasn't bothered about the literal meaning: often there wasn’t one, but the imagery evoked magical inward visions, emotions and feelings. Not that every song by Genesis or poem by Thomas was quite so obscure, but even in those poems I could make some sense of, like the luminous ‘Fern Hill’ or ‘Poem in October’ – it was the music which enchanted me.

Nowadays, though I still love the music, I look for meaning too. And behold, it's there, and now I understand it a little bit better.

‘My craft, or sullen art.’ How honest that adjective is, ‘sullen’: because writing can be so hard, so difficult, so damned uncooperative! You try and you try, and it’s not good enough, still not good enough, but you keep trying. You keep trying because what you’re really aiming for, what you want the most – and he’s right, he’s so right – isn’t money, isn’t ‘ambition or bread’, nor fame: ‘the strut and trade of charms/On the ivory stages’. No!

We don't write for the critics. We don't write (we wouldn’t dare, though maybe Thomas dared) with an eye on posterity and the hope of joining the ranks of ‘the towering dead with their nightingales and psalms’. We don’t write for fame and most of us don’t get it – or even make a living out of it. We're grateful to those who find and read our words, for no one owes us any attention and most will pay no heed. I think we write because this sullen, difficult art won't let us go. We write to honour ‘the lovers, their arms round the griefs of the ages’, because each person in this world is such a lover. We write to share, as best as we are able, the common wages of the secret heart.

'The Lovers' by John Everell Millais, British Museum

Published on February 09, 2020 04:17

January 7, 2020

Glass Slippers, Fur Slippers! Cinderella's Shoes.

There are extraordinary numbers of superstitions about shoes - though most are now unfamiliar to us 21st century mortals. According to Iona Opie and Moira Tatem’s ‘Dictionary of Superstitions’, an old shoe hung up at the fireside was thought to bring luck. You would turn your shoes upside down to prevent nightmares, or to stop a dog from howling; it was unlucky to put your right shoe on before your left; burning a pair of old shoes could prevent children from being stolen by the fairies; bad luck was bound to follow if a pair of new shoes was placed upon a table -- and so on and on. In fact, shoes have often been often hidden within the fabric of buildings, possibly as apotropaic charms to ward off evil.

Here's a photo of a whole collection of such shoes from East Anglia, courtesy of St Edmundsbury Heritage Service. Northampton Museum keeps a ‘Concealed Shoe Index’; in a pamplet written for the museum J.M. Swann describes some of the finds, dating from the early 15thcentury into the 20th:

The shoes are usually found not in the foundations but in the walls, over door lintels, in rubble floors, behind wainscoting, under staircases… shoes occur singly or with others, very rarely in pairs, occasionally in ‘families’ – a man’s, woman’s, and a range of sizes of children’s. Sometimes they are found with other objects – a candlestick, wooden bowl or pot, wine glass, spoon, knife, sheath, purse, glove, pipe… The condition of the shoes, like the objects found with them, is usually very poor: worn out, patched, repaired.

My mother preserved some tiny silver shoes which were used to decorate her wedding cake. Old shoes used to be thrown after the departing bride and groom for luck and I can remember at least once seeing old boots tied to the bumper of the honeymoon couple's car. Maybe this still happens? It's a practice which goes back centuries. Opie and Tatem quote John Heywood in 1546: ‘For good lucke, cast an olde shoe after mee’ and Ben Jonson in 1621: ‘Hurle after an olde shooe, I’le be merry what e’er I doe.’ Francis Kilvert writes in his diary for January 1, 1873:

The bride went straightway to her carriage. Someone thrust an old white pair of satin shoes into my hand with which I made an ineffectual shot at the post-boy, and someone else behind me missed the carriage altogether and gave me with an old shoe a terrific blow on the back of the head…

Shoes are very personal items. They literally mould themselves to the shape of an individual’s foot. Anyone who’s sorted through the clothes of someone who’s died will know how the sight of a pair of their empty shoes is especially poignant. It’s as if well-worn shoes have almost become part of the person. Perhaps that’s why, as the folklorist Sabine Baring-Gould writes in his 1913 ‘Book of Folk-Lore’:…when we say that a man has stepped into his father’s shoes, we mean that the authority, position and consequence of the parent has been transferred to his son.

Now to Cinderella. Numerous variants of the Cinderella story (tale type ATU 510A) include the motif of the heroine’s shoe which is dropped or lost and, when restored and matched to her foot, proves her identity and worth. In Basile’s ‘La Gatta Cenerentola’ or ‘The Hearth-Cat’ (1634) the heroine Zezolla drops a fashionable ‘stilted shoe’ or ‘chopine’ as she escapes from the festa: when she appears at a banquet which the King has ordered for all the ladies in the land, it darts to her foot like iron to a magnet. Chopines were the platform shoe to end all platform shoes – more like towers than platforms, as you can see below – and must have been extremely difficult to walk in: no wonder Zezolla lost one. (They're almost incredible, but apparently some were as tall as twenty inches high and you can find out more about them here.)

16th century style Venetian chopinePerrault’s Cinderella has slippers made of glass, such an improbable material for shoes that some have argued it must be a mistake, a confusion between ‘vair’ (parti-coloured fur) and ‘verre’ (glass). But really, when has improbability ever troubled a fairy tale? Aschenputtel’s shoes are golden, Scottish Rashin Coatie’s slippers are made of satin, and in one of my favourite versions, the Irish tale ‘Fair, Brown and Trembling’, the heroine Trembling gets the jazziest shoes of all. She asks a henwife (a magical figure in Irish tales) for clothes fit to go to church in. On the first day the henwife obliges with a dress as white as snow and green shoes, on the second she provides a dress of black satin and red shoes, and on the third day Trembling demands:

16th century style Venetian chopinePerrault’s Cinderella has slippers made of glass, such an improbable material for shoes that some have argued it must be a mistake, a confusion between ‘vair’ (parti-coloured fur) and ‘verre’ (glass). But really, when has improbability ever troubled a fairy tale? Aschenputtel’s shoes are golden, Scottish Rashin Coatie’s slippers are made of satin, and in one of my favourite versions, the Irish tale ‘Fair, Brown and Trembling’, the heroine Trembling gets the jazziest shoes of all. She asks a henwife (a magical figure in Irish tales) for clothes fit to go to church in. On the first day the henwife obliges with a dress as white as snow and green shoes, on the second she provides a dress of black satin and red shoes, and on the third day Trembling demands:“A dress red as a rose from the waist down, and white as snow from the waist up; a cape of green on my shoulders, and a hat on my head with a red, a white and a green feather in it, and shoes for my feet with the toes red, the middle white and the backs and heels green.”

Flamboyant in these fairy colours, riding on a white mare with ‘blue and gold-coloured diamond-shaped spots’ all over its body, Trembling cannot enter the church and has to listen to mass from outside the door, but the king’s son sees her and falls in love. Racing beside Trembling’s horse as she rides away, he pulls a shoe from her foot and searches all Ireland for the fair lady.

In a story from China dating to 850/860 AD, the heroine Yeh Xien loses and has restored to her a gold shoe ‘as light as down’, and in what may be the oldest recorded variant of the tale – from the early first century AD – there is still a shoe, or at least a sandal. It comes in part of an account of the Pyramids by the Roman historian, geographer and traveller Strabo. After describing the Pyramids, he explains that one of them: