Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 22

March 5, 2015

The Devil at the Centre of the World

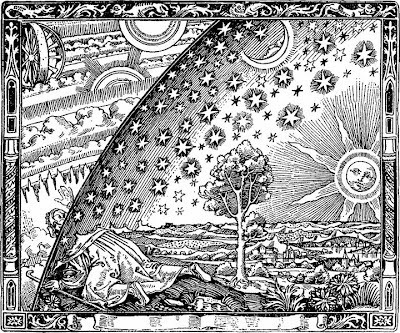

The Flammarion engraving, 1888, artist unknown“Medieval people thought the world was flat.” Well no, they didn’t, not educated people at least (and after all there’s still the Flat Earth Society today, whose members appear to believe that the moonshots were a hoax, though it’s hard to tell how many of them are simply having a bit of straight-faced fun.) And there were plenty of educated medieval people.

The Flammarion engraving, 1888, artist unknown“Medieval people thought the world was flat.” Well no, they didn’t, not educated people at least (and after all there’s still the Flat Earth Society today, whose members appear to believe that the moonshots were a hoax, though it’s hard to tell how many of them are simply having a bit of straight-faced fun.) And there were plenty of educated medieval people.Mind you, the pre-Christian early medieval Norse did – theoretically – believe in a sort-of flat earth. They imagined middle earth surrounded by an encircling ocean, with Yggdrasil, the World Tree, growing up from its centre. Even then, the delving roots and high branches of Yggdrasil evoke layer upon layer of other dimensions. But this poetic, mythic explanation of the universe was unlikely to have been applied in any serious way to the voyages the Vikings made, which were guided by careful observation of landmarks and ocean currents, of drifting seaweed and circling gulls, of the migration of whales and the position of stationary clouds over land.

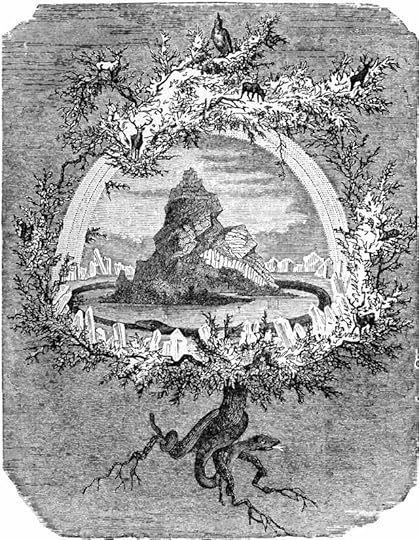

The Ash Yggdrasi by Friedrich Wilhem Heine

The Ash Yggdrasi by Friedrich Wilhem HeineI suspect pragmatic Norse sailors performed that simple human trick of being able to believe two incompatible things at once: religio-mythic descriptions of the universe were one thing: the sea route to Greenland was quite another. In my book ‘West of the Moon’, the storm-driven Norse sailors of the knarr ‘Watersnake’, sailing across the North Atlantic, argue about their position.

“What if we miss Vinland altogether and sail over the edge of the world?” Floki piped up, conjuring in every mind a vision of the endless waterfall plunging over the rim of the earth.“Showing your ignorance, Floki,” said Magnus. “The world is shaped like a dish, and that keeps the water in. Ye can’t sail over the edge.”“That’s not right,” Arne argued. “The world’s like a dish, but it’s an upside down dish. You can see that by the way it curves.”Magnus burst out laughing. “Then why wouldn’t the sea just run off? You can’t pour water into an upside-down dish.”“It’s like a dish with a rim,” said Gunnar in a tone that brooked no arguments. “There’s land all round the ocean, just like there’s land all round any lake. Stands to reason. And that means so long as we keep sailing west, we’ll strike the coastline.”

West of the Moon, HarperCollins 2009

Gunnar is wrong, of course, but in a practical sense he’s also right. Sail far enough west from anywhere in Europe, and you’ll strike the American continent somewhere. And Arne’s right too in his observation of the curvature of the world’s surface - obvious to any sailor who sees the land rising out of the sea as he sails towards it. In Canto II of Dante’s early 14th century ‘Purgatorio’, the boat bringing the souls of the saved to the island of Purgatory rises above the horizon as it approaches: Dante spies the tips of its guiding angel’s wings before the boat itself is visible:

...as Mars reddens through the heavy vapours, low in the west over the waves at the coming of dawn, so a light appeared… coming over the sea so quickly that no flight equals its movement, and when I had taken my eyes from it for a moment to question my guide, I saw it once more, grown bigger and brighter. Then something white appeared on each side of it, and little by little, another whiteness emerged from underneath it.

My Master did not speak a word, until the first whitenesses were seen to be wings… and it came towards the shore, in a vessel so quick and light that it skimmed the waves.

(trans. A.S. Kline © 2000)

The Greeks of the 4th century had discovered that the world is a sphere, a fact which was commonsense observation and no news to most medieval people, including churchmen. However, commonsense observation can also deceive. With their own eyes, medieval people could see the sun, moon and stars turning around the earth. But as C. S. Lewis points out in his indispensable book on the medieval cosmos, ‘The Discarded Image’, this geocentric view of the universe didn’t necessarily mean they thought the central Earth was the most important thing in it. To get a genuinely Euro-medieval view, you have to turn your ideas about the cosmos inside out. The eternal, unchangeable, holy realms were all out there, beyond the circuit of the changing Moon. The sun and moon and stars and planets all turned around the earth, set in crystal spheres, making heavenly harmony as they went. This is why Lorenzo exclaims to Jessica in ‘The Merchant of Venice’,

Look how the floor of heavenIs thick inlaid with patines of bright gold:There’s not the smallest orb which thou behold’stBut in his motion like an angels sings....

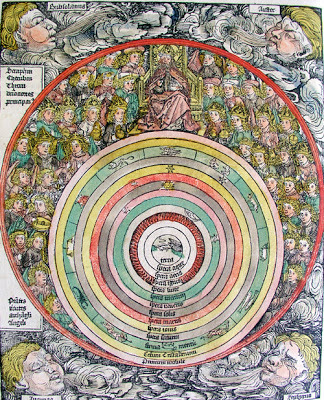

From The Nuremberg Chronicle, 1493My 12th century Welsh heroine Nest, in ‘Dark Angels’, expresses it with the aid of a mural painted by her dead mother:

From The Nuremberg Chronicle, 1493My 12th century Welsh heroine Nest, in ‘Dark Angels’, expresses it with the aid of a mural painted by her dead mother:“See this picture, how beautiful it is? A map of the whole of Creation! Mam painted it herself. I used to sit on a stool eating nuts and watching her.”She pointed. “Look, here’s the Earth in the middle, like a little ball. All around it is the air. Above that, the Moon.” She traced a line up the wall. “Next, Mercury and Venus.” Her finger landed on a fiery little sun with a human face, crackling with life. “Here’s the Sun. Then Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, spinning around and around the Earth, all of them set in crystal spheres, each one bigger than the last! Then, this dark blue circle with the stars painted in it – that’s the Fixed Stars, all turning around together. And then the sphere that makes them all move, and beyond that” – her finger burst through the last ring, like a chicken pecking through an eggshell – “Heaven.”She drew a deep breath. “That’s where my mam is! Outside the universe. Safe with God.”

Dark Angels, HarperCollins 2007

There’s a grandness of imagination to the medieval design of the universe, which for centuries worked well as a mathematical model – it takes into account huge distances, but on a human scale. Humans are small, living on a world that is tiny compared to the vastness of the Primum Mobile, the sphere of the First Mover - but not scarily insignificant.

Chaucer’s Troilus, in ‘Troilus and Criseyde’ (written mid 1380’s), ascends to the seventh sphere after his death and looks down:

…And down from thennes fast he gan aviseThe litel spot of erthe, that with the seaEmbraced is...

Hell was of course located underground, at the centre of the earth – where Dante and his guide Virgil find gigantic Satan buried up to the waist at the very bottom of the funnel that is Hell – and have to turn around as they climb down his hairy body, to find themselves ascending as they pass the midpoint of the world. Dante narrates:

[Virgil] took fast hold upon the shaggy flanksand then descended, down from tuft to tuftbetween the tangled hair and icy crusts.When we had reached the point at which the thighRevolves, just at the swelling of the hip,My guide, with heavy strain and rugged workReversed his head to where his legs had beenAnd grappled on the hair, as one who climbs.I thought that we were going back to Hell.

But Virgil explains:

...When I turned, that's when you passed the pointto which, from every part, all weight bears down.

(trans: Allen Mandelbaum)

Satan, by Gustave Doré

Satan, by Gustave DoréI’m struck dumb with admiration at Dante’s utterly fantastic feat of imagination here. He died in 1321, and it would be over 350 years before Isaac Newton worked out his theory of gravitation: people observe things, and can deploy them for practical purposes, long before they can adequately explain them.

Of course, the medieval universe also included another underground world besides Hell. Tinged with a whiff of the same infernal smoke - with a suspicion that the back door might lead much deeper down - in shallow caves and holes and hollow hills was the kingdom of Elfland…

But that is another story.

Published on March 05, 2015 01:32

January 27, 2015

Written in Stone

SunkenkirkLike most children’s authors, I make occasional school visits where I talk about ‘where ideas come from’ and tell some of the stories behind the historically based fantasies such as Troll Fell and Dark Angels which represent most of my output so far. Usually at the end of each visit the children ask me questions, and though some require a certain amount of patience to answer (such as: ‘What made you start writing?’ when I’ve just spent forty-five minutes explaining that very thing), the majority are intelligent and thoughtful - even insightful. The best question ever put to me was from a boy of 13 or so who asked, ‘If you could go back to anywhere in the past, where would you go?’

SunkenkirkLike most children’s authors, I make occasional school visits where I talk about ‘where ideas come from’ and tell some of the stories behind the historically based fantasies such as Troll Fell and Dark Angels which represent most of my output so far. Usually at the end of each visit the children ask me questions, and though some require a certain amount of patience to answer (such as: ‘What made you start writing?’ when I’ve just spent forty-five minutes explaining that very thing), the majority are intelligent and thoughtful - even insightful. The best question ever put to me was from a boy of 13 or so who asked, ‘If you could go back to anywhere in the past, where would you go?’No one had asked me that before. No one has asked it since. I had to stop and think. Where wouldI go? There’s a short story – could it be by Ray Bradbury? – about time-trippers who go back to the beginning of the First Century to try and witness the Crucifixion. It all goes wrong for them. I thought about that; it didn’t seem appropriate: and suddenly I knew just where I'd want to go. ‘Stonehenge,’ I said. ‘I’d love to go back to when they were building Stonehenge, and find out what they were really doing there.’ The boy nodded seriously. To him, too, it seemed a good time and place to visit.

We're gradually learning more and more about Stonehenge and its landscape: the story, whatever it is, is becoming ever more fascinating. But we’ll still never really know what they were doing there, will we? Not for sure, even if we can speculate. Has any trace of what they believed come down to us? What were their myths and legends? What hero stories did they tell?

The archaeologist Francis Pryor, in his book ‘Britain BC’, writes of the Northern Irish Bronze and Iron Age site known as Navan Fort (County Armagh):

The Cattle Raid of Cooley describes how the mythical hero Cú Chulainn helps Conchobar, king of Ulster, based at his capital Emain Macha (pronounced Owain Maha) exact retribution for a cattle raid carried out by warriors of the rival power of Connacht, to the south. Scholars are agreed that The Cattle Raid of Cooley refers to events in pre-Christian Ireland. There can be no doubt that Emain Macha was the capital of the Ulster kings. And it just so happens that it is also the Irish name for Navan Fort.

Navan Fort, Co Armagh (wikimedia)

Navan Fort, Co Armagh (wikimedia)In the early Iron Age a series of nine roundhouses were built at Navan Fort; but in the first century 100 BC these were replaced by a massive wooden structure of over 250 tall posts arranged in concentric rings. Shortly afterwards, it was filled with boulders and burned to the ground. From the air, the open excavation shows a regular, segmented, pizza-like appearance. Pryor adds:

... Chris Lynn has made a special study of the symbolism and imagery surrounding Navan. He considers that the huge, post-built structure that was erected in 94 BC was a bruidne, or magic hostelry; these have been likened to an Iron Age Valhalla. According to the Irish epics the heroes were lavishly feasted in the bruidne, then at the end of the meal it was burned down around them and they were immolated where they sat.

Navan Fort, excavation

Navan Fort, excavationHere, perhaps, is a tiny glimpse of the significance of a prehistoric monument, preserved - as they say - in legend and in song. You can read about just such an immolation in part of the Ulster cycle, The Destruction of Da Derga's Hostel ("Da Derga" means "Red God"). Da Derga's Hostel, or inn, was in Leinster and as far as I know has no modern presence, but its story suggests possibilities for the burned structure at Emain Macha. 'Seven doorways there are in it, and seven sleeping rooms between every two doorways'. in which Conaire Mor, High King of Ireland, dies, having breached the conditions of several geasa laid on him at birth. Conaire is a heroic Iron Age figure:

The colour of his hair was like the shining of purified gold; the cloak about him was like the mist of a May morning, changing from colour to colour; a wheel brooch of gold reaching from his chin to his waist; his golden-hilted sword within his reach.

But he and his company are attacked by outlaws, the Three Red Hounds of Cualu and their ally Ingcel the One-Eyed:

...three times the Inn was set on fire and three times it was put out again... and at last there was none left in the Inn with Conaire but Conall, and Sencha, and Dubthach. Now from the rage that was on Conaire, and the greatness of the fight he had fought, a great drought came on him, and such a fever of thirst, and no drink to get, that he died of it.

It’s exciting, stirring, it gives me goosebumps, but it’s the exception rather than the rule. What were the stories told by the builders of Stonehenge? We have none earlier than the medieval conjectures of Geoffrey of Monmouth, who thought Merlin built it with the help of Irish giants.

It’s not just Stonehenge though. Over 1000 stone circles can still be seen in the British Isles, even if many are small and insignificant. I once took my husband and children to try and rediscover a little one on the moors above Malham in the Yorkshire Dales, where I used to live. It’s marked on the Ordnance Survey map, and I’d visited it by myself years before: a rough group of a few knee-high boulders leaning out of the moor-grass. We couldn’t find it, and not only that, there was an inexplicable, lowering, heavy gloom about the day which sapped our spirits. The children whined, we felt depressed: we gave up and returned home to discover, later, an eclipse of the sun had been happening during our walk. Not a total eclipse, but enough to explain the failure of the light, the doomy sense of pointlessness we’d felt. And whoever built that little circle, thousands of years ago – what would they have made of our experience?

In the Lakes last summer, driving back over Black Combe from the coast at Ravenglass, I spotted the tiny symbol of a stone circle marked on the route map. It took a bit of finding, diving up the tiny twisting roads and finally squishing the car into a hedge and tramping up a mile and a quarter of rough trackway towards a distant farm. I wasn’t expecting much. I thought it would be like the Malham circle, a small set of minor stones poking out of the turf. As we drew nearer to the farmhouse, we saw this:

And getting closer, this:

This was no minor stone circle. It is Sunkenkirk, or Swinside Stone Circle, on the north-east side of Black Combe, and it's almost complete, containing 55 stones. (I made it 58, but that included some broken bits.) We tied the dog to the gate, as there were sheep and cattle in the field, and went in.

Once inside, I tried to photograph it in quadrants. The circle lies - like Castlerigg - on a high, flattish plateau surrounded on all sides by a horizon of noble hills. It feels like a dancing floor or a theatre.

It even has a sort of ceremonial porch on the southeastern side, a set of double stones flanking the entrance.

It was a beautiful, serene afternoon. The worn stones glowed in the late sunshine. The circle was so complete, it felt as though the people who built and used it had only just gone away, instead of being dust for 5000 years.

But who were they? Why did they build it and what did it mean to them? We have only the name Sunkenkirk, and a tale - for we will always tell tales - that it was built by the Devil, who busied himself at night in pulling down and removing the stones of a church which was being built in the day. That's a new, young story, perhaps a hundred years old. We will never know what stories were told about this circle immediately after it was built, or through most of the rest of its long, long history.

In an essay called 'Burning Bushes' (from 'In Other Worlds: SF and the Human Imagination', Virago 2011), Margaret Atwood speculates on the value of art to early societies: that those who possessed

... such abilities as singing, dancing and – for our purposes – the telling of stories – would have had a better chance of survival than those without them. That makes a certain sense: if you could tell your children about the time your grandfather was eaten by a crocodile, right there at the bend of the river, they would be more likely to avoid the same fate. If, that is, they were listening.

Language and narrative are inextricable one from another. Every sentence we speak lays a narrative template over experience and alters our perceptions. In the beginning was the Word: we create our own worlds in our own images. If you can tell a ‘true’ story about the crocodile at the bend of the river, fiction and myth spring at once into existence. Because you can tell another story, about how bravely your grandfather fought the crocodile (even if you weren't there yourself): and that leads almost inevitably to the question of where he is now - surely not mere crocodile food, but a hero in the world of ancestors, who passes his wisdom down to you and maybe speaks to you in dreams.

Some years ago I visited this grassy barrow. There it is the in the middle of the photograph, looking just like so many I've seen in England: but we know who lies there, and who buried them, and when, and why. It's the burial place of the Plataean forces who fought alongside the Athenians commanded by Miltiades, against the Persians under Darius, at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC. We know, because the story was written down. And knowing it sent prickles down my spine.

The battle of Marathon was written as history (though maybe not history as we conceive of it today) not too long after the events themselves. 'The Cattle Raid of Cooley' was only written down centuries after the events it purports to describe, after the oral tradition and mythification process, the business of turning fact into fiction, had got well under way. Yet as in the tales of Troy and Knossos, some truths were preserved in the storytelling, like flies in amber. But there are no such stories for Stonehenge, no hero tales from Sunkenkirk. And that's why, if I could travel back in time I'd still go to the the third millenium BC and visit them.

Because I want to know their story.

Picture creditsAll photos copyright Katherine Langrish except the photo of Navan Fort which I found at Navan Fort Archives Digital Key

and the photo of Marathon: Wikimedia Commons.

Published on January 27, 2015 03:18

January 12, 2015

Why The Owl Service isn’t as easy as a computer thinks it is.

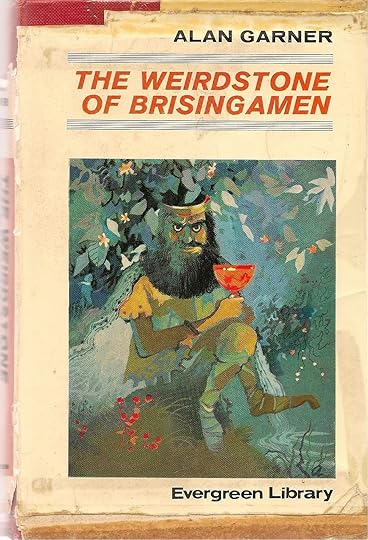

My friend and fellow children's writer Cecilia Busby commented in a recent blog post for the 'Awfully Big Blog Adventure' on a computer-run reading scheme used in schools, Accelerated Reader. Developed as a guide for teachers and parents, the scheme assesses and grades books for young readers. It awards each title a number on a scale ranging from easy (around 3) to difficult (11 or 12), and encourages children to read by awarding collectable points for each title and providing quizzes to test their understanding. The scheme is popular and widely used, but Cecilia discovered some anomalies in its grading system. For example, Accelerated Reader grades Alan Garner’s 1967 book The Owl Serviceas easier for young readers than his debut novel The Weirdstone of Brisingamen. Anyone who’s actually read the books will know that this is bonkers. Intrigued, I took a closer look to try to find out how such a mistake could have been made.

My battered, much-loved childhood copy

My battered, much-loved childhood copyIt seems the AR programme judges books by length, complexity of syntax and difficulty of vocabulary – including proper nouns. Although The Owl Service contains a number of unusual Welsh names such as Lleu Llaw Gyffes and Gronw, it can’t compare with The Weirdstone of Brisingamen’s whole bunch of unusual polysyllabic names such as Durathror, Fenodyree, Angharad, Llyn-dhu, Fundindelve, Cadellin, Atlendor, and of course the eponymous Weirdstone itself. Moreover, a glance at any page of The Owl Service will show a high proportion of dialogue – and consequently shorter, snappier sentences and simpler syntax – than the many long narrative paragraphs of The Weirdstone. So the dutiful AR computer has awarded The Owl Servicea lowish 3.7 and banded it MY (Middle Years) for children aged 9-13, while The Weirdstone has been pushed right up to 6.3 and banded UY (Upper Years) for readers of 14 and over.

The Owl Service is far more advanced, difficult and sophisticated book than The Weirdstone, but the computer does not know this, because it literally cannot read between the lines. All the most interesting stuff in The Owl Service goes on in the spaces and silences and misunderstandings between the characters. And that’s the trouble. Reading isn’t just about understanding what words say. It’s also about understanding what they imply.

Here is the elliptically brilliant opening page of The Owl Service:

‘How’s the bellyache, then?’ Gwyn stuck his head round the door. Alison sat in the iron bed with brass knobs. Porcelain columns showed the Infant Bacchus and there was a lump of slate under one leg because the floor dipped. ‘A bore,’ said Alison. ‘And I’m too hot.’ ‘Tough,’ said Gwyn. ‘I couldn’t find any books, so I’ve brought one I had from school. I’m supposed to be reading it for Literature, but you’re welcome: it looks deadly.’ ‘Thanks anyway,’ said Alison. ‘Roger’s gone for a swim. You wanting company, are you?’ ‘Don’t put yourself out for me,’ said Alison. ‘Right,’ said Gwyn. ‘Cheerio.’ He rode sideways down the banisters on his arms to the first floor landing. ‘Gwyn!’ ‘Yes? What’s the matter? You OK?’ ‘Quick!’ ‘What’s the matter? You going to throw up, are you?’ ‘Gwyn!’He ran back. Alison was kneeling on the bed.‘Listen,’ she said. ‘Can you hear that?’‘That what?’‘That noise in the ceiling. Listen.’The house was quiet. Mostyn Lewis-Jones was calling after the sheep on the mountain: and something was scratching in the ceiling above the bed.

This apparently effortless piece of text provides immense density of information: but it takes time to unpack. We learn – if we are really thinking while we read – that the scene is set in a bedroom on the top floor of an old Welsh house (the uneven floor and the old brass bed); we learn that the weather is hot, probably summer; we learn that the house is situated among mountains where sheep are reared. We are introduced to three main characters by name, and we see that while the unseen Roger has gone swimming, Gwyn is interested in Alison. He brings her a book and asks how her tummy-ache is (perhaps she has period pain; they must be teenagers) and, pseudo-casually, asks if she wants his company. When she reacts ungraciously, he pretends not to care – only to speed back upstairs to her side as soon as she calls him, to listen to something scratching up in the ceiling.

No inexperienced reader is going to ‘get’ all this – or any of it – or be especially interested if they did. Imagine a younger child deciphering ‘what happens on the first page’ without understanding the subtext. ‘A girl is sick in bed. I don’t know what all the stuff about porcelain columns and Bacchus is supposed to mean. A boy brings the girl a book which he says is boring. They talk a bit. Then he goes downstairs and then she calls for him and he thinks she’s going to be sick, and then she tells him to listen to a scratching noise.’ On the surface, little is happening. It could seem disjointed, confusing, dull.

Like the very grown-up tale from the Mabinogion which inspired it, The Owl Service is about nothing if it is not about relationships, and Garner expects the reader to work at the implications of his prose. He rarely tells us what anyone thinks or feels, or what they look like. But it’s all there.

Compare the much more conventional first page of The Weirdstone (not counting the prologue, The Legend of Alderley):

The guard knocked on the door of the compartment as he went past. “Wilmslow fifteen minutes!” “Thankyou!” shouted Colin. Susan began to clear away the debris of the journey – apple cores, orange peel, food wrappings, magazines, while Colin pulled down their luggage from the rack. And within three minutes they were both poised on the edge of their seats, case in hand and mackintosh over one arm, caught, like every traveller before or since, in that limbo of journey’s end, when there is nothing to do and no time to relax. Those last miles were the longest of all. The platform of Wilmslow station was thick with people and more spilled off the train, but Colin and Susan had no difficulty in recognising Gowther Mossock among those waiting. As the tide of passengers broke round him and surged through the gates, leaving the children lonely at the far end of the platform, he waved his hand and came striding towards them. He was an oak of a man: not over tall, but solid as a crag, and barrelled with flesh, bone and muscle. His face was round and polished; blue eyes crinkled to the humour of his mouth. A tweed jacked strained across his back, and his legs, curved like the timbers of an old house, were clad in breeches, which tucked into thick woollen stockings just above the swelling calves. A felt hat, old and formless, was on his head, and hob-nailed boots struck sparks from the platform as he walked.

Fifty-five years after it was written, these long sentences might strike a modern child as a bit slow, but they present few challenges and there is a reassuring sense of direction: when they get off the train, very soon, an adventure will begin. True, the train isn’t quite like a modern train, and children might not now (did they ever?) divide tasks quite so readily into ‘girl clears up the litter and boy lifts down the cases’ – and ‘limbo’ and ‘mackintosh’ might conceivably puzzle some young readers. Still, the first half-page is a straightforward narrative, while the second half is an equally easy-to-follow description of Gowther Mossock – perhaps a little lengthy, but Gowther’s solid dependability renders him an important emotional anchor in the adventures that lie ahead. For The Weirdstone of Brisingamen is of course not about relationships. Though there are few signs of it in that conventional opening, the book is a fiery, frosty fantasy which burst upon my twelve year-old consciousness like a firework of marvels, magic and excitement. In those days even children expected a book to start in a leisurely manner and to gather momentum as it went along, but it is still a far more accessible story for a young reader than The Owl Service can ever be.

For a writer to progress from The Weirdstone of Brisingamen to The Owl Service in seven short years (1960 – 1967) was to display extraordinary talent. Alan Garner is one of our greatest living writers. But I need to confess in this context, that as a young reader, I couldn’t keep up. And I was a really good reader, a child who read all day, every day. I devoured at least ten books a week. I was probably ten or eleven when I first read The Weirdstone, and over the next few years I read it and its sequel The Moon of Gomrath (1963), and Garner’s third children’s book Elidor (1965) multiple times, and secretly began writing Garner-inspired fiction of my own. But I wasn’t progressing as a reader at the same speed that Alan Garner was progressing as a writer. He was accelerating away from me, and with Red Shift in 1973 seemed in fact blue-shifting from children’s into adult fiction. When I first read The Owl Service at the age of 13 or so I found it dry and spare and difficult. I looked in vain for the colour and richness of the earlier books, and its pared-down dialogue was wasted on me. If The Owl Service had been the first book I’d read by Alan Garner, I doubt if I would ever have tried his others. And that would have been a great shame.

But the computer goes by rule-of-thumb. The computer looks at syntax and vocabulary. The computer thinks The Owl Service is for children of 9 to 13 and The Weirdstone of Brisingamen is for teenagers of 14 plus. I’m not mocking. Friends assure me that the AR programme really does encourage schoolchildren to read, that many of them like the element of competition and enjoy amassing points for the titles they read. So long as they are also enjoying the books themselves, that’s good. But parents and teachers should know that the system isn’t foolproof. The computer which assesses and grades these titles cannot actually read – in a human sense – at all.

A computer can never replace an experienced librarian.

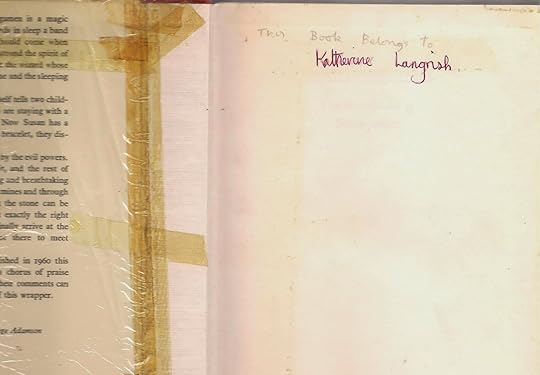

Stuck together with Sellotape, my 1965 edition of The Weirdstone with my name written inside

Stuck together with Sellotape, my 1965 edition of The Weirdstone with my name written inside

Published on January 12, 2015 04:10

January 5, 2015

January Tales

Look carefully; the countryside is full of goblins.

Out with my dog one foggy morning a few days back I fell in with my neighbour Colin walking his elderly spaniel. Colin’s a shrewd countryman with plenty of tales to tell, who was born in a damp, thatched Dartmoor cottage over seventy years ago, one of a large family of practical hard-headed country people. We strolled along the lane together chatting about how though thatched cottages look so pretty, they’re usually very dark inside. We were just passing one, and Colin gazed at the thatch. ‘Riddled with rat-runs ours used to be, full of rats and mice; they didn’t cover ‘em with netting then, the way they do now. And leaky! – we had to set buckets and basins out to catch the drips. And fleas? It’s a wonder we didn’t all die, the way my mother used to sprinkle the beds with DDT.’ He shook his head. ‘Like sugar out of a sugar shaker.’

We turned past the cottages into the field, full of low-hanging grey mist. A few years ago one misty morning I’d been coming along the hedge here and looked up to see an impossibly tall giant approaching out of the foggy brightness. Seconds later I saw it was a tree, superimposed on another tree – a crooked elbow, a shoulder, a shaggy head – yet the shock lingered. I told Colin.

‘When I was a boy,’ he said, ‘I went to work for a hunting stable, and in the winter I had to come home late along this deep dark lane, and every night there’d be someone standing on the bank watching me. He wouldn’t move and he wouldn’t speak, and he was never there in the day. Well the way I’d handle it, I’d walk on the other side, and when I got close to him I’d start to run, and I’d yell out, “Good night sir!” and run past as fast as I could. “Good night, sir!” I’d shout, and I’d run. Well, my mother could see something was scaring me, and in the end she got it out of me, and she said, “We’ll see about that,” she says, and she come down the lane with me in the dark. And when we get there, “You silly old fool,” she says, “it’s only an old tree stump after all.”’

Published on January 05, 2015 09:18

December 15, 2014

Re-reading Narnia: 'The Horse and His Boy'

This, the fifth Narnia book in order of publication, is the one I’ve thought about least since childhood. And it was never one of my particular favourites, which seems odd considering that next to Narnia, ponies were my passion. A book which combined Narnia and horses ought to have been a big hit.

I enjoyed the book, but I didn’t love it the way I loved The Voyage of the Dawn Treader and The Silver Chair. This may be because it’s the least complex, least layered of the Seven Chronicles. It’s a simple adventure story offering straightforward pleasures: appealing main characters, obnoxious villains, touches of humour, an arduous journey and a nick-of-time rescue. What it does not offer – alone among the Narnia books – is anything much in the way of strong emotion, wonder or awe: certainly nothing to match the moment when the Stone Table cracks in two, or Reepicheep’s coracle vanishes over the crest of the wave at the end of the world: nothing to match the brilliant birds fluttering in the trees at the top of Aslan’s holy mountain, or the poignant death of old King Caspian. To use Lewis’s own term, there is no ‘stab of joy’ in The Horse and His Boy. On this re-reading I was often entertained and amused by the book, but seldom moved.

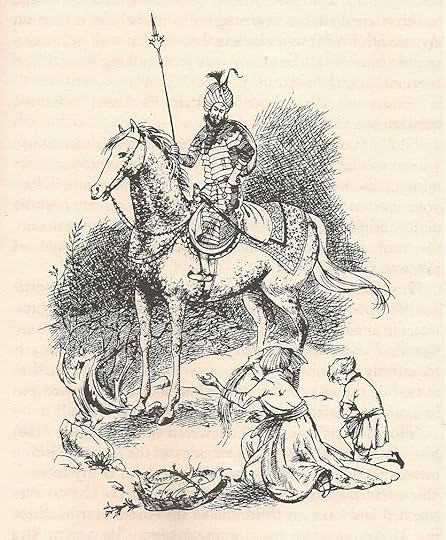

Told throughout from within – from the point of view of characters who were born in Narnia rather than in our world – The Horse and His Boy is set during the ‘golden age’ of Narnia when the four thrones of Cair Paravel are filled by the four children of The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe. The hero of the book, the boy Shasta, has grown up to the age of perhaps twelve believing himself the son of Arsheesh, a poor fisherman in the southern land of Calormen, a country which will remind most readers of the Persia of the Arabian Nights. And at once we run into a difficulty. The dark-skinned Calormens are depicted in a way that strikes me now as at best naively Orientalist, at worst upsettingly racist.

In an essay called ‘The Revolution in Children’s Literature’ (The Thorny Paradise, Writers on Writing for Children, ed. Edward Blishen, Kestrel 1975) Geoffrey Trease recalls the sexism and racism prevalent in children’s books during the first half of the 20thcentury and bravely illustrates it with a toe-curlingly inappropriate extract from a story written by himself as a schoolboy in 1923:

‘The white dog!’ hissed the Arab leader, and his scimitar grated against my cutlass… I saw the dark triumphant face of my antagonist, the curved beam of reflected light raised to strike, and like a flash I ducked, and striking upwards with my left hand, administered a thoroughly British uppercut. And, because an Oriental can never understand such a blow, he reeled back, a look of almost comical surprise on his face. Ere he could recover, I lunged out with my cutlass and stretched him dead upon the ground.

While you’re still wincing: I have a theory that classic children's books have a half-life of about fifty years of being read by actual children (after a century, most are relegated at best to academic study). They last this long mainly because adults give or read to children the books they themselves remember; and because books are durable physical objects that may sit around for decades on dusty shelves to be pulled out by voracious young readers. This is how I gobbled down the jingoistic and now almost unreadable works of GA Henty, written in the last third of the nineteenth century. What modern ten year-old could tolerate ‘Under Drake's Flag, A Tale of the Spanish Main' (1883) or 'By Sheer Pluck: A Tale of the Ashanti War' (1884)? They were eighty years old by the time I was reading them in the 1960's and I think I must have been in the last generation of children who could possibly have enjoyed them. But the sixty year-old Narnia stories are very much with us, kept alive like the Velveteen Rabbit by the love of real children. While Henty's prejudices may no longer matter, those of CS Lewis are still of concern. And I can't help feeling he should have known better. As an adult writer, Geoffrey Trease set out to combat the prejudice he’d parroted as a boy. His historical novels for children, like ‘The Red Towers of Granada’ (1966), are deliberately respectful of ‘other’ cultures as those of Judaism or Islamic Spain. In spite of his efforts, the range of literature available to me growing up in the sixties was still crammed with dodgy foreigners: effete, or cunning, or comic, or cowardly, or cruel. I noticed it, without realising it was unfair. So long as an author spins a good story, children are accepting readers.

Lewis first introduces the Calormen in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader:

Two merchants of Calormen … approached. The Calormen have dark faces and long beards. They wear flowing robes and orange-coloured turbans, and they are a wise, wealthy, courteous, cruel and ancient people.

‘Wise, wealthy, courteous and ancient’ are all very well until we reach that word ‘cruel’: in its company all other virtues are contaminated. Lewis continues:

They bowed most politely to Caspian and paid him long compliments, all about the fountains of prosperity irrigating the gardens of prudence and virtue – and things like that – but of course what they wanted was the money they had paid.

The Calormen’s flowery language is critiqued in THHB as the language of insincerity, especially compared to the white-skinned Narnians’ free, frank speech. (Interesting, that word ‘frank’, with its derivation from the founders of western culture.) From the outset Lewis leaves no doubt that Calormen culture and society is morally inferior. One has only to look at the relationship between Shasta and his foster father Arsheesh to see how Lewis puts his hand in the scales. The fairytale motif of ‘noble baby set adrift’ is known world-wide, from Moses, to Perseus, to Perdita in The Winter’s Tale, and in most of these stories the foster parent, whether humble fisherman or noble princess, rescues and raises the child with unselfish tenderness. Lewis inverts this tradition. Arsheesh self-servingly explains to the Tarkaan who wishes to buy Shasta:

‘“Doubtless,” said I, “these unfortunates have escaped from the wreck of a great ship, but by the admirable designs of the gods, the elder has starved himself to keep the child alive, and has perished in sight of land.” Accordingly, remembering how the gods never fail to reward those who befriend the destitute, and being moved by compassion (for your servant is a man of tender heart) – ’

‘Leave out all these idle words in your own praise,’ interrupted the Tarkaan. ‘It is enough to know that you took the child – and have had ten times the worth of his daily bread out of him in labour, as anyone can see…’

There’s no love or tenderness between Arsheesh and Shasta: the latter is simply relieved to learn that he’s not the fisherman’s own flesh and blood. He even dreams of possible advancement (‘the lordly stranger on the great horse might be kinder to him than Arsheesh’). Lewis soon dispels this dream, and leaves an adult reader in some discomfort as to why this Tarkaan has suddenly taken a fancy to buy Shasta.

‘This boy is manifestly no son of yours. For your cheek is as dark as mine but the boy is fair and white like the accursed but beautiful barbarians who inhabit the remote north.’

Admiration for despised beauty is never a good sign. What is Bree the Talking Horse implying, when he warns Shasta in the strongest terms that the Tarkaan is bad – ‘Better be lying dead tonight than go to be a human slave in his house tomorrow’? As a child I simply assumed ‘hard work and beatings’. Now I wonder whether this might truly be a 'fate worse than death'.

Orientalism is a term employed by Edward Said to examine and criticise patronising Western perceptions of the East: it marks a subset of racism which views Eastern cultures as irredeemably mysterious, 'inscrutable' and Other. Lewis’s characterisation of the dark-skinned Calormen, quoted above, as ‘wise, wealthy, courteous, cruel and ancient’ could be a textbook example. If Trease could overcome his early conditioning, why couldn’t Lewis? Yes, there is Aravis: yes, there is the gentle and courteous knight Emeth in The Last Battle: they remain exceptions.

But there is more going on. Narnia is a paradise of happy magical creatures and talking animals. By contrast, Calormen is a grown-up country of farms and roads, a religion and a class structure, a bureaucracy, a literature, slaves and soldiers and cities. Despite its supposed Arabian Nights exoticism, from a child’s perspective Calormen is a dull place.

How come? Where are all those flying carpets, magical rings, terrifying jinni, sorcerers and enchantresses with which Scheherezade filled the Thousand and One Nights? Lewis ditched them all. He borrowed the trappings of the Arabian Nights but left out all the magic. Reading about Calormen is a bit like reading a nineteenth-century European travelogue of a journey through rural Turkey.

Shasta was not at all interested in anything that lay south of his home because he had once or twice been to the village with Arsheesh and he knew that there was nothing very interesting there. In the village he only met other men who were just like his father – men with long, dirty robes, and wooden shoes turned up at the toe, and turbans on their heads, and beards, talking to one another very slowly about things that sounded dull.

It’s not as though the Narnia books haven’t already carried us to foreign lands. The wilds of Ettinsmoor, the depths of Bism, the numinous islands of the Eastern Sea – these belong, these fit within the Narnian fairy world. But Calormen isn’t a fairytale land. It exists to oppose Narnia’s every quality. If Lewis had wanted, he could have incorporated peris and griffins, flying carpets and sphinxes into his story, but he didn’t want. Not even the ghouls of the Tombs are ‘real’.

In a fantasy series which happily blends classical and Norse mythologies, medieval legends and talking animals, why did Lewis instinctively (I doubt he thought about it) strip out all the magic from the Arabian Nights? Where else in the Narnian world does this failure of enchantment occur? In the least interesting episode of The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, on the unmagical Lone Islands where the Calormen trade for slaves – and in King Miraz’s Narnia, where the only town, Beruna, is demolished by Aslan and the personified powers of nature (a destruction significantly presented as a restoration). Narnia at its most Narnian is a place of joyful and magical disorder, a place in which there is no need for rules because no one wants to do anything bad. It owns no villages like Shasta’s, no cities, no roads. Cair Paravel is a stand-alone fairytale castle with no town around it. King Lune’s castle of Anvard in Archenland is similarly isolated.

Unlike the threat posed by the magical White Witch and Green Lady, the threat to Narnia from Calormen (and the Telmarine rule of Miraz) is a divorce from magic. The Calormen are enemies of the imagination, enemies of fairyland itself. Their rule would destroy Narnia's magic, substituting an order of economics, progress, trade, politics, scepticism: unromantic things which Lewis didn’t like and didn’t want in his fairy paradise. The be-turbaned, Arabian Nights-style Calormen represent these values, however, only because Lewis chose they should. Historically it was the west which imposed its industrial and political values upon the rest of the world.

In conservative Christian circles CS Lewis is the logic-chopping wielder of the Sword of Truth, but he could and did allow prejudice to blind him. No doubt at the back of his mind was the medieval clash between Islam and Europe: the Matter of France, the Song of Roland, the Battle of Lepanto. Compared with the magic of the pagan Greek myths (so important a component in classical education as, paradoxically, to have become a part of Christian European identity) I suspect Lewis felt deep in his bones that the magic of the Arabian Nights was foreign,inimical, incompatible with Aslan’s. So he left it out, but his depiction of the Calormen creates all sorts of problems. They are undoubtedly human, so where have they come from? Are they, like Peter and Edmund, Susan and Lucy, ‘sons of Adam and daughters of Eve’ - originally from our world? When Aslan sang Narnia into existence in The Magician’s Nephew, did he create Calormen too? And what about their gods, Zardeenah, Azaroth and Tash? I feel there'll be much more to say about these questions when we come to The Last Battle.

For now, though, on with the story!

One of the things I truly loved about this book was the relationship between Shasta and Bree, the Narnian Talking Horse who, like Shasta, was kidnapped as a little foal.

“My mother warned me not to range the southern slopes, in Archenland and beyond, but I wouldn’t heed her. And by the Lion’s Mane I have paid for my folly. All these years I have been a slave to humans, hiding my true nature and pretending to be dumb and witless like their horses.”

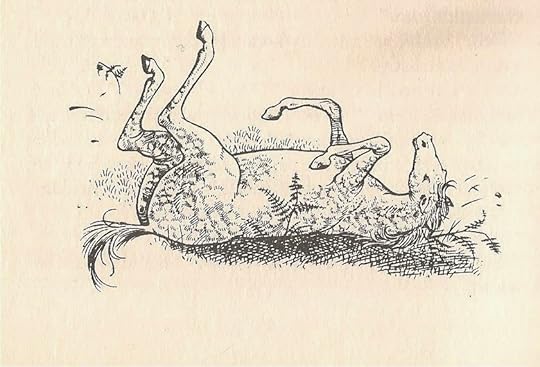

A pony-mad little girl, I found the story of Shasta being taught to ride by his horse enchanting (“No one can teach riding so well as a horse”). Bree, or to give him his full name, Breehy-hinny-brinny-hoohy-hah – is a superb character. I loved and still love the comedy of his good-humoured disdain for Shasta and for humans in general (“What absurd legs humans have!”) and his bracing lack of sympathy for Shasta’s aches and pains (“It can’t be the falls. You didn’t have more than a dozen or so.”). An experienced war-horse, Bree takes initial charge of the escape: but as the adventure continues it is the inexperienced Shasta who begins to make the difference, while Bree allows vanity and insecurity (would a true Narnian Talking Horse enjoy a good roll?) to undermine him.

Bree sees that escaping together will improve both their chances: he won’t be chased as a stray, and on his back Shasta can ‘outdistance any other horse in this country.’ With a final bit of riding advice from the Horse to his Boy, off they go:

“Grip with your knees and keep your eyes straight ahead between my ears. Don’t look at the ground. If you think you’re going to fall just grip harder and sit up straighter. Ready? Now: for Narnia and the North.”

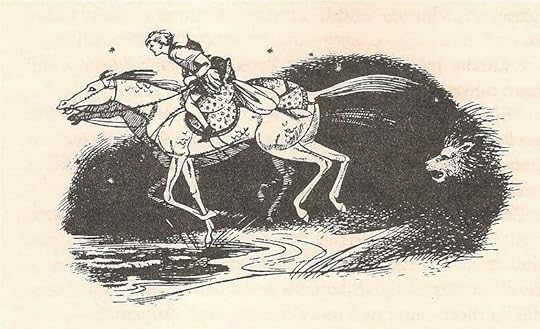

One night after ‘weeks and weeks’ of journeying, Bree and Shasta hear another horse and rider accompanying them northwards between the forest and the sea.

“Ssh!” said Bree, craning his neck around and twitching his ears... “…That’s not a farmer’s riding. Not a farmer’s horse either. Can’t you tell by the sound? …I tell you what it is, Shasta. There’s a Tarkaan under the edge of that wood. Not on his war horse – it’s too light for that. On a fine blood mare, I should say.”

'Craning his neck around and twitching his ears': Lewis never lets us forget that Bree is a horse.

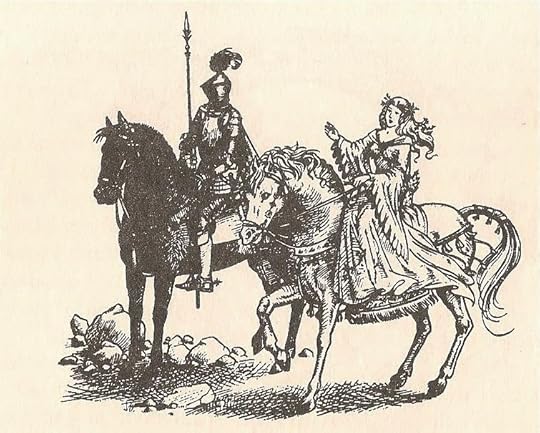

The strange ‘horseman’ seems as eager to avoid them as they are to avoid him, but lions attack. The two horses are driven together in a mad gallop across the sands, and the young rider – described as a ‘small, slender person, mail-clad … and riding magnificently’ is revealed as a girl, Aravis, with ‘her’ Talking Horse, Hwin. It’s a dramatic entrance, and Aravis takes no prisoners from the start.

“Broo-hoo-hah!” [Bree] snorted. “Steady there! I heard you, I did. There’s no good pretending, Ma’am. …You’re a Talking Horse, a Narnian horse, just like me.” “What’s it got to do with you if she is?” said the strange rider fiercely, laying hand on sword-hilt. But the voice in which the words were spoken had already told Shasta something. “Why, it’s only a girl!” he exclaimed. “And what business is it of yours if I am onlya girl?” snapped the stranger. “You’re only a boy: a rude, common little boy – a slave probably, who’s stolen his master’s horse.”

When the book was written fifty years ago, this ‘only a girl’ thing was everywhere, a universal gas we all breathed. In Little Women, in What Katy Did – in Enid Blyton’s books about the Famous Five, even in Geoffrey Trease – my friends and I encountered heroines who wished they were boys, and we didn’t always understand that this wasn’t because boys were naturally superior, but because society privileged them with better choices and opportunities. So it was great to meet competent, confident Aravis who rode a horse the way I wished I could, and wore a sword too. And when Shasta comes out with this classic put-down, ‘only a girl’, Aravis annihilates him. Later in the book, when Hwin quietly suggests it would be wise for them to keep going, Bree retorts crushingly: 'I think, Ma'am... that I know a little more about campaigns and forced marches and what a horse can stand than you do'. (Stallionsplaining?) Hwin shuts up because she is 'a very nervous and gentle person who was easily put down.' But Hwin is right and Bree is wrong, and his decision is a bad one. To my mind, Lewis is quite certainly an equal-opportunities author.

This is as I’ve said, an adventure story, and it’s linear: Shasta and his friends must get from A (Calormen) to B (Narnia). It's an escape rather than a quest. We already know what Narnia is like (or we do if we’ve read the other books), so all the surprises, all the plot interest must come from twists and turns and picaresque interludes along the way. The first is when Aravis relates her escape, and for once Lewis, via Bree, has something good to say about the formal and flowery Calormen narrative style (the sort of thing we expect of 'Eastern' tales but perhaps actually an artefact of Western translations: in her 2013 edition of The Thousand and One Nights, Hanan Al-Shaykh praises the original's 'flat, simple style'). However:

Bree… was thoroughly enjoying the story. “She’s telling it in the grand Calormen manner and no story-teller in a Tisroc’s court could do it better…”

Aravis’ story is effectively another fairytale: cruel stepmother persuades weak father to marry his daughter to a rich old man. In despair, Aravis is about to kill herself when Hwin her mare ‘magically’ begins to talk – the Animal Helper motif of so many fairystories – and to tell her about

The woods and waters of Narnia and the castles and the great ships, till I said, “In the name of Tash and Azaroth and Zardeenah Lady of the Night, I have a great wish to be in that country of Narnia.” “O my mistress,” answered the mare, “if you were in Narnia you would be happy, for in that land no maiden is forced to marry against her will.”

Aravis hatches a plot.

I put on my gayest clothes and sang and danced before my father and pretended to be delighted with the marriage which he had prepared for me. Also I said to him, “O my father and O the delight of my eyes, give me your licence and permission to go with one of my maidens alone for three days into the woods to do secret sacrifices to Zardeenah, Lady of the Night, as is proper and customary for damsels when they must bid farewell to the service of Zardeenah and prepare themselves for marriage.”

This surely is Lewis’s conscious recall of a very dark Old Testament story (Judges 11, 34-39) when the warrior Jephthah (in another ancient fairytale motif) bargains with God for victory over his enemies in exchange for a burnt offering of the first thing that greets him on his return home:

And Jephthah came to Mizpah unto his house, and, behold, his daughter came out to meet him with timbrels and with dances; and she was his only child… And he rent his clothes, and said, Alas, my daughter! thou hast brought me very low… for I have opened my mouth unto the Lord and I cannot go back. And she said unto him, My father, if thou hast opened thy mouth unto the Lord, do to me according to that which hath proceeded out of thy mouth. … And she said unto her father, Let this thing be done for me: let me go alone two months that I may up and down upon the mountain and bewail my virginity, I and my fellows. And he said, Go. And he sent her away for two months: and she went with her companions and bewailed her virginity upon the mountains. And it came to pass at the end of two months that she returned unto her father, who did with her according to his vow which he had vowed.

In this case, Lewis redeems the story. Aravis does what we might all wish Jephthah’s unnamed daughter could have done. She tricks her father, obtains three days grace, drugs her maid, dresses in her brother’s armour and races for Narnia on Hwin – covering her tracks further by sending her father a letter as if from her betrothed husband claiming to have married already after a chance meeting in the woods. Aravis displays from the beginning great competence, cool-headedness and fortitude: she is, as Lewis later comments, ‘proud and could be hard enough but… as true as steel’. What she doesn’t have is empathy: it is left to Shasta the underdog to wonder what might have happened to the maid Aravis drugged and left behind.

“Doubtless she was beaten for sleeping late,” said Aravis coolly. “But she was a tool and spy of my stepmother’s. I am very glad that they should beat her.” “I say, that was hardly fair,” said Shasta. “I did not do any of these things for the sake of pleasing you,” said Aravis.

When I first read this book I can’t say that the fate of the maid upset me very much, and I appreciated tough, unsympathetic Aravis who does the necessary without wringing her hands. The adventure story is a genre which requires a brisk pace and little consideration of those who fall by the way or get in the way. But of course this isn’t your average adventure story and Lewis has a moral agenda. He wants his child readers to notice the collateral damage. Aslan is watching, and Aslan will repay – an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth:

“The scratches on your back, tear for tear, throb for throb, blood for blood, were equal to the stripes laid upon the back of your stepmother’s slave because of the drugged sleep you cast upon her. You needed to know what it felt like.”

“Tear for tear, throb for throb, blood for blood.” It sounds sadistic. Does Aslan punish Aravis because her action got the slave-girl into trouble? Or is it rather because she wasn’t sorry about it and didn’t care? I think the latter. Aravis’ punishment can’t help the slave-girl, who will never even hear of it. “You needed to know what it felt like”: this is about Aravis herself, to correct a flaw in her character and teach her to empathise. It seemed fair to me as a child. (“Children, who are innocent, love justice, while most of us are wicked and naturally prefer mercy,” GK Chesterton said.) But now? Now I think this is penny-in-the-slot type justice. You do something bad: something bad happens to you: end. How neat it would be if, as Jesus said, ‘With what measure ye mete it shall be measured to you again’, but it doesn’t work that way in real life and even if it did, where is the victim in this? Aslan lays no responsibility on Aravis to consider that slave-girl again, or to try and help her. In fact he even discourages her from doing so, saying as he so often does that it is ‘not your story’. Again: this is an adventure story and most adventure stories would never raise the issue of ‘what happened to the slave girl?’ in the first place – but having raised it, Lewis doesn’t seem to me to deal with it well. So long as you’re sorry, there’s no need to do anything but accept your lesson gracefully, and grow in compassion and understanding, and everything in the garden will be lovely? It’s easy but dangerous to relinquish earthly justice to one’s notion of the divine. Where was justice, for Jephthah’s daughter? I don’t like Aslan very much, in this book.

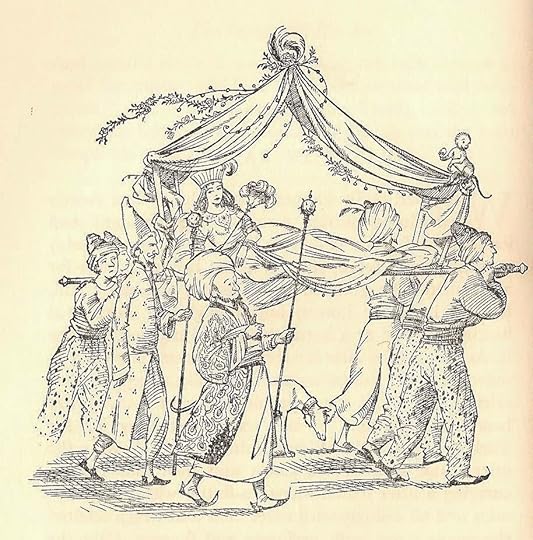

The next interlude is the journey through the city of Tashbaan, during which Shasta is separated from his friends. In an adventure pretty much borrowed wholesale from Mark Twain’s The Prince and the Pauper, he is mistaken for his (as it will turn out) long-lost identical twin, young Prince Corin of Archenland who's come on a Narnian state visit to Tashbaan centred on a possible marriage between Susan of Narnia and Prince Rabadash, eldest son of the Tisroc. In comparison to the Calormen lords and ladies lolling on their litters carried by “gigantic slaves”, the Narnians are first seen on foot:

Their tunics were of fine, bright, hardy colours – woodland green, or gay yellow, or fresh blue. Instead of turbans they wore steel or silver caps… The swords at their sides were long and straight, not curved like the Calormen scimitars. And instead of being grave and mysterious like most Calormenes, they walked with a swing and … chatted and laughed. One was whistling. You could see they were ready to be friends with anyone who was friendly and didn’t give a fig for anyone who wasn’t. Shasta thought he had never seen anything so lovely in his life.

Reading this as a child I was of course thrilled to be in the company of real Narnians at last, and Lewis makes them sound attractive indeed – a real breath of fresh air. Now I can’t help noticing how every word is loaded so that even the Narnians’ dress choices appear ‘better’ than those of the Calormen. It’s absurd to suggest that Calormen people never dress in blue, yellow or green: but why in any case should those colours be preferred to red, purple or gold? Because those are the colours associated with luxury and by further implication moral degeneracy? It would be even more absurd to say out loud that the ‘straight’ Narnian swords suggest directness and honesty while the ‘curved’ Calormen scimitars denote indirectness and treachery – but that’s what this passage manages, on a subconscious level, to imply.

Snatched from his friends, Shasta is taken away to the Narnians’ guest suite in a great palace, where he is scolded as a truant. In the same way that young Tom Canty in The Prince and the Pauper is mistaken for King Henry VIII’s son Prince Edward, and assumed to have lost his memory from ‘too much study’, Mr Tumnus (hooray!) suggests to Edmund and Susan that the ‘little prince’ must have a touch of sunstroke. ‘Look at him! He is dazed. He does not know where he is.’ Told to rest on a sofa and given iced sherbert to drink, Shasta overhears all the Narnians’ discussions. Queen Susan no longer wishes to marry Prince Rabadash, who is turning out – in Edmund’s words - ‘a most proud, bloody, luxurious, cruel and self-pleasing tyrant’. In the course of their discussions Shasta learns of a secret desert route which he and his friends will take once reunited. But the Narnians intend to escape by sea, and now Shasta hopes to go with them.

He only hoped now that the real Prince Corin would not turn up until it was too late and that he would be taken away to Narnia by ship. I am afraid he did not think at all of what might happen to the real Corin when he was left behind in Tashbaan. He was a little worried about Aravis and Bree waiting for him at the Tombs. But then he said to himself, “Well how can I help it?”

This is disconcerting selfishness. If it weren’t for Corin’s sudden return (having got into a fight and been arrested by the Watch) Shasta would abandon his friends. His readiness to make excuses for himself and to think badly of Aravis may be realistic but it's not endearing. Lewis dedicated THHB to David and Douglas Gresham, the young sons of the American writer Joy Davidman whom he was to marry in 1956, two years after the book was published, and I wonder if he chose a boy protagonist for their sake? Shasta is the first male main character in the Narnia books (in order of publication), but Lewis doesn’t really love him. Aravis has more flair, Bree more personality, Hwin more compassion... From the beginning Shasta is starved of emotional depth. Is it because Lewis thought boys would find emotion - other than fear - soppy?

You must not imagine that Shasta felt at all as you or I would feel if we had just overheard our parents talking about selling us for slaves. For one thing, his life was already little better than slavery… For another, the story about his own discover in the boat had filled him with excitement and with a sense of relief. He had often been uneasy because, try as he might, he had never been able to love the fisherman.

There's no regret, no sense that Shasta wishes Arsheesh could have loved him. Shasta’s life is an emotional void and he doesn’t seem to know or care. Ambition stirs, but no longing:

And now, apparently, he was no relation to Arsheesh at all. That took a great weight off his mind. “Why, I might be anyone!” he thought. “I might be the son of a Tarkaan myself – or the son of the Tisroc (may he live forever) – or of a god!”

Shasta is inexperienced and naïve, and he wants to be something better. He is not just awkward with and rude to Aravis because she is a girl, but because he is jealous of her: her status, confidence and manners: and there is some shrewd comedy at his expense:

Aravis produced rather nice things to eat from her saddlebag. But Shasta sulked and said No thanks, and that he wasn’t hungry. And he tried to put on what he thought very grand and stiff manners, but as a fisherman’s hut is not usually a good place for learning grand manners, the result was dreadful. And he half knew is wasn’t a success and then became sulkier and more awkward than ever.

This is not unsympathetic, but it’s likely to make us smile at Shasta rather than love him. His main characteristics are anxiety and self-pity: he has no core strength like Lucy or Jill or Aravis. Perhaps his inarticulacy is touching: a revelation of the fears and inadequacies that boys so often conceal. Still, as the story progresses, Shasta and Aravis learn to judge one another more fairly, and Shasta does take responsibility for the desert march. Though it seems to come out of the blue, he proves himself finally at the moment when he jumps off Bree's back to defy the lion that is attacking Aravis – and when he runs on at the Hermit’s urging to warn King Lune of Rabadash’s approaching force. But even when he finds himself to be Prince Cor, eldest son of King Lune of Archenland, the emotional drought continues. The dam never breaks, the rain never comes, the revelation is all cogs and clockwork. Shasta is still worried what Aravis will think of him, and he continues to express himself in tongue-tied clichés like a prep-school boy:

Father’s an absolute brick. I’d be just as pleased – or very nearly – at finding he’s my father even if he wasn’t a king. Even though Education and all sorts of horrible things are going to happen to me.

Two throwaway moments in THHB show what Lewis could have done with Shasta. One is when Bree presses the question of whether Shasta can eat grass:

“Ever tried?”“Yes, I have. I can’t get it down at all. You couldn’t either if you were me.”

The other is when Shasta tries dismounting (to spare the horses) on the desert ride:

As his bare foot touched the sand he screamed with pain and got one foot back in the stirrup and the other half over Bree’s back before you could have said knife.

A child who tries to eat grass, a child whose shoeless feet scorch in the hot sand: here is poverty made pitiable and tangible.

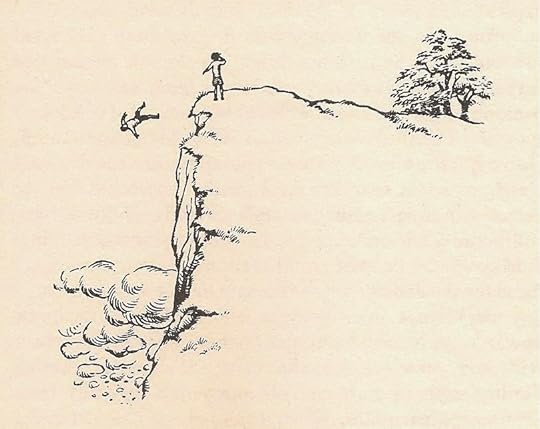

Moving on: after the 'real' Prince Corin reappears, Shasta hurries to the Tombs of the Ancient Kings, where he and his friends have agreed to meet if they became separated in Tashbaan. '... and now the sun had really set. Suddenly from somewhere behind him came a terrible sound. Shasta's heart gave a great jump and he had to bite his tongue to keep himself from screaming. Next moment he realised what it was: the horns of Tashbaan blowing for the closing of the gates.' In one of the most memorable and atmospheric chapters in the book Shasta spends the night alone beside the Tombs, which are like 'gigantic beehives ... black and grim', later even more scarily personified as '... horribly like huge people, draped in grey robes that covered their heads and faces'.

Aravis, meanwhile, has been having adventures which mirror Shasta's: recognised by her girly friend Lasaraleen, she effects a hair-raising escape from the palace at night, during which, crushed behind a sofa, she and Lasaraleen overhear Rabadash and the Tisroc plotting treacherously to attack King Lune's castle of Anvard - and witness the cringing, sycophantic behaviour of her affianced husband, Ahoshta the Vizier. With Lasaraleen's help, Aravis and the horses rejoin Shasta at the Tombs where they pool their information. Aravis carries the news of Rabadash's plans; Shasta knows the secret route across the desert. The race is on to reach Archenland ahead of Prince Rabadah, and warn King Lune.

Aslan, it turns out, has been masterminding nearly the whole plot of THHB – as he himself explains, walking unseen in the mist unseen beside Shasta when he is lost.

I was the lion who forced you to join with Aravis. I was the cat who comforted you among the houses of the dead. I was the lion who drove the jackals from you while you slept. I was the lion who gave the Horses the new strength of fear for the last mile so that you should reach King Lune in time. And I was the lion you do not remember who pushed the boat in which you lay, a child near death, so that it came to shore…

Leiws wants us to find this moving, satisfying, perhaps even reassuring. At ten years old I accepted it but it didn’t move me, and now it seems manipulative, reducing the characters to puppets. Aslan reconfigures Shasta’s account of his misfortunes to show that all the ‘bad’ things which have happened to him have in fact been for the good. There is something uncomfortably controlling about Aslan’s sequential incursions into the lives of Shasta, Aravis and Bree even though it’s all for their own good and even though Bree certainly deserves to be taken down a peg or two. As a child I found the scene irresistibly comic in which Bree confidently asserts that Aslan is not a real lion – while Aslan creeps up behind him.

“No doubt,” continues Bree, “when they speak of him as a Lion they only mean he’s as strong as a lion or (to our enemies of course) as fierce as a lion. …it would be quite absurd to suppose he is a real lion. … Why!” (and here Bree began to laugh) “If he was a lion he have four paws, and a tail, and Whiskers!... Aie, ooh, hoo-hoo! Help!

For just as he said the word Whiskers one of Aslan’s had actually tickled his ear.

It is still funny. Just not as funny as it was.

The religious message in THHB seems to me painting-by-numbers. A series of events is worked out to illustrate a set of propositions: God ordains all things; God knows and judges all things; God will reward the good and punish the sinner; God is with us always. It reminds me too often of those ‘footprints in the sand’ posters which can be bought from Christian bookshops with a little parable in which God reassures us that ‘when you thought you were walking alone, that is when I was carrying you.’ Such parables undoubtedly do comfort some people, and heaven knows we all need comfort. However, sincerity is required to make these things work, and in The Horse and His Boy I’m not convinced Lewis is sincere. It’s all a little too clever. There is no sense that anything springs from a deep emotional source and this is evident at the end of Chapter XI when Aslan at last reveals himself to Shasta. Lewis strains unsuccessfully for affect: at least it doesn't work for me.

It was from the Lion that the light came. No-one ever saw anything more terrible or beautiful. … After one glance at the Lion’s face [Shasta] slipped out of the saddle and fell at its feet. He couldn’t say anything but then he didn’t want to say anything, and he knew he needn’t say anything.

The High King above all kings stooped towards him. Its mane, and some strange and solemn perfume that hung about its mane, was all around him. It touched his forehead with its tongue.

This is a stern, remote, High Church Aslan far removed from the flesh and blood Lion who played so joyfully with Lucy and Susan in The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe – as far removed perhaps as the Jesus of the Gospels seems from the Christ of the Road to Damascus. The Aslan who sacrificed himself to save Edmund, whose blood and pain restored Caspian to life, youth and strength, has become the Aslan who tears bloody stripes in Aravis's back and even scratches Shasta in retaliation for having once thrown stones at a cat. It's a harsh and retributive transformation.

Still, as a child, I felt the adventure had been wrapped up very satisfactorily. The story ends in slapdash humour. Prince Rabadash makes a fool of himself (“The bolt of Tash falls from above!” – “Does it ever get caught on a hook half-way?”) and is transformed by Aslan (punitive to the last) into a donkey so he can do no more harm. Shasta is reinstated as Prince of Archenland. Bree casts off his anxiety and has a good roll. Cor and Aravis’s eventual marriage, in order to go on quarrelling ‘more conveniently’, seemed to me a reasonable and un-sloppy basis for a relationship: they were clearly good friends. I closed the book and reached for the next.

What has surprised me most on this re-reading isn't so much that I found myself addressing questions of racism; I knew from the start I would need to do that. What has really surprised me is how didactic, how prescriptive, I've found a book which in my memory was the least 'religious' of the Narnia stories. My suspicion is that it turned out this this way because Lewis's heart was never really in the story at all (except for the character of Bree, horsiest of horses). He turned, perhaps, to dogma rather than to feeling. Luckily 'The Magician's Nephew' comes next, a book into which Lewis really did pour his heart, his art - and his past.

More of that soon. Meanwhile a happy Christmas, happy Hannukah, happy solstice, happy holidays to you all.

Picture credits:

All artwork from 'The Horse and His Boy', by the magnificent Pauline Baynes. Visit her website here: http://www.paulinebaynes.com/

Published on December 15, 2014 01:34

December 10, 2014

The Grasshopper's Child by Gwyneth Jones

“You’re a recovered asset, hired out by the loan company to work off your dad’s debts.”

“You mean I’m a slave,” said Heidi.

This excellent YA novel is set in the same world as Gwyneth Jones’ Arthur C Clarke Award winning, five book cycle ‘Bold As Love’ – set, that is to say, ‘fifteen minutes into the future’ of a United Kingdom in the process of economic and political collapse, when a trio of rock musicians – lovers and friends – find themselves thrust to charismatic leadership of a Barmy Army battling for England’s soul against the forces of a new Dark Age. (The Arthurian echoes are deliberate.) If you haven’t read them, and if you enjoy character-driven, audaciously imagined, beautifully-written novels with a breath of sci-fi and a hint of magic, you can start rubbing your hands now.

Although fans of the adult series will enjoy picking up references to the earlier books, The Grasshopper’s Child is a stand-alone novel well pitched for young adults (for whom Gwyneth Jones has written for years under the pen name Ann Halam).

Before she did the terrible thing, Heidi Ryan had been a teen with adult dependents, exempt from Ag. Camp because Mum and Dad couldn’t manage without her. Her Mum had schizophrenia – which, as Immy their social worker kept telling Heidi isn’t a disease, it’s a name for a bunch of distressing mental health symptoms. … Dad’s issues weren’t so obvious. … Basically, Immy said, he was a lovely man and a good dad, but he’d taken too many drugs when he was young and … now he just couldn’t make decisions. Or pay bills. Or generally look after himself, never mind anyone else. But that was okay because Heidi was in charge. Or so she thought.

For years, Heidi has been her parents’ carer. But coming home one day to find her father dying in a pool of blood and her mother brandishing a knife, she does the ‘terrible thing’: she calls the police. Her mother is taken away, and Heidi is sent to the remote coastal village of Mehilhoc to become an Indentured Teen – or, as she bluntly points out to the Old Wreck she works for, a slave. (In a society which routinely demonises and commodifies people on benefits; the Dept. of Work and Pensions recently demanded a man work six months without pay for the company which had sacked him - this seems chillingly possible.)

As she explores the overgrown garden of the dilapidated mansion whose owners now own her, Heidi’s mission is to prove that her mother didn’t kill her father. But there are further mysteries. Why has the suitcase containing all her worldly goods gone missing? What is the secret of the bitter, decrepit brother and sister whom she serves? Who or what comes creeping up the attic stairs at night? Why does everyone defer to the Carron-Knowells, effectively feudal lords of the village?

Heidi is a wonderful heroine, tough and sensitive, a poet who puts her fears and joys into genuinely good verse. As she makes friends with other teenagers in the village, The Grasshopper’s Child explores the dynamics of this group of young people: their strengths and weaknesses, the things they can say to one another and the things that are left unspoken. It explores friendship and responsibility, and the difference between sexual attraction and real liking: when Heidi finds herself reacting to her friend Challon’s off-and-on boyfriend Gorgeous George Carron-Knowell, she deals with it in a manner that preserves self-respect. Heidi has bags of self-respect. She is a delightful and formidable character – oh, one who happens also to be black.

As ever with Gwyneth Jones, the writing is a joy to read: beautiful, vivid and tactile, as here: 'red velvet curtains, worn to rust in the folds, silently coughed out dust when she touched them...' I can almost taste that acrid dust in my throat. With ghosts, with technological wizardry, with mystery, modern pirates and murder, and references to The Secret Gardenas well as many a children’s adventure story (secret tunnels, anyone?) The Grasshopper’s Child is a feast. Do buy it, and curl up with it for Christmas.

Visit Gwyneth Jones' website here: http://homepage.ntlworld.com/gwynethann/Buy The Grasshopper's Child as an ebook on Amazon

The cover picture above is that on the proof of the paperback edition. I will add a link when I know it is available.

Published on December 10, 2014 02:01

October 30, 2014

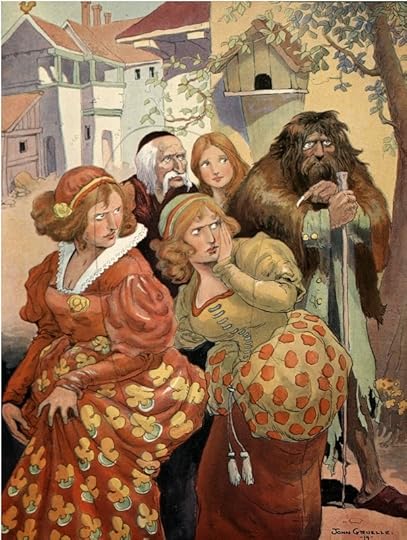

Fairytale Reflections: DER BÄRENHÄUTER/THE BEARSKIN

by Jane Rosenberg LaForge

A combination of “Beauty and the Beast” and “Cinderella’’, with an equal part of “The Cat-Skin’’ and a good dose of Job, “The Bearskin” (Der Bärenhäuter in the original German) is a tale of one man testing his endurance against the Devil’s. Some versions of the story, such as the one told in the Philippines, don’t necessarily pronounce a winner in this contest. But the original Grimm’s fable makes it abundantly clear: the Devil triumphs again. At times the story has been known as “The Devil, a Bearskin” (Der Teufel ein Bärenhäuter) as if to reinforce this idea. The Bearskin, a starving young man who makes his deal with the Devil so he might survive, undergoes a transformation, but he is no Cinderella, and no friendly and misunderstood Beast either. But this story, I have come to understand, still has had its own impact on the culture, or at least on mass entertainment.

In traditional tellings of “The Bearskin,” a soldier without a war to fight has no food, money, or shelter, and no prospects of finding any; his brothers have rejected him. He appears to be close to suicide when a cloven-hoofed creature in a green jacket reveals himself, and offers a way out. The green jacket will produce all the money he needs if the soldier does not say the Lord’s Prayer; if he does not wash, cut his hair, or clip his nails—if he becomes a monster by sleeping, eating, and living in a bearskin the Devil has just harvested from a bear that threatened to kill the both of them, moments earlier. If the soldier can live as the Bearskin for seven years, he’ll be returned to his natural state again.

Without any options, the soldier says yes. He wanders about the country, paying poor people to pray for him; and his transformation from man to monster is gradual. Eventually, though, he is forced to retreat to a room at an inn because his appearance is so appalling. While at the inn, he hears a man in great distress, and discovers the man has lost his fortune. He offers to help the man by giving him money; to thank him, the man promises Bearskin one of his three daughters in marriage. The two older daughters refuse Bearskin, but the youngest agrees because Bearskin has helped her father. Bearskin breaks a ring in two, gives half to this daughter, and keeps the other half. Then he leaves to complete his odyssey.

After serving his seven years, the Bearskin summons the Devil and demands that he be cleaned up; in some versions, he forces the Devil to say the Lord’s Prayer. He then returns to the inn to retrieve his bride but is mistaken for a more desirable colonel; the two older daughters vie for his attentions. But by presenting his half of the ring, he reveals himself to the youngest daughter and declares: “I am your betrothed bridegroom, whom you saw as Bearskin. Through God's grace I have regained my human form and have become clean again." When the older sisters see the two embracing, they are overcome with rage and anger. One sister hangs herself; the other drowns herself in a well.

The Devil arrives at the home of the new bride and groom that evening. "You see, I now have two souls for the one of yours,’’ he says, referring to the two sisters’ suicides. And so the tale ends. Maybe.

I was raised in the 1960s in the United States, so what I knew from fairy tales came in the form of Disney movies, books, and costumes. “The Bearskin” was not suitable for such purposes. Perhaps there was no way for Disney to tidy up its message. I did not encounter “The Bearskin” until graduate school, when I was studying German as part of my English degree. “Der Bärenhäuter” was one of the short selections in our textbook. This is appropriate, since fairy tales are one way we pass language and all its shadings onto our children, and yet at the same time, I was too old, and possibly too cynical, to buy into its message.