Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 24

May 3, 2014

Fearsome Persephone

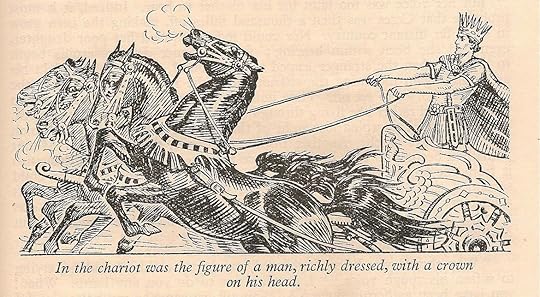

The Greek myth of Persephone has often been retold as a sweet and charming little story, a just-so fable about the cycle of winter and spring. Here’s an extract from a 19th century version for children, ‘The Pomegranate Seeds’ by Nathaniel Hawthorne. Persephone (under her Roman name, Proserpina) has begged Mother Ceres for permission to pick flowers, when, attracted by an unusually beautiful blossoming bush, she pulls it up by the roots. The hole she has created immediately spreads, growing deeper and wider, till out comes a golden chariot drawn by splendid horses.

In the chariot sat the figure of a man, richly dressed, with a crown on his head, all flaming with diamonds. He was of a noble aspect, but looked sullen and discontented; and he kept rubbing his eyes and shading them with his hand, as if he did not live enough in the sunshine to be very fond of its light.

“Do not be afraid,” said he, with as cheerful a smile as he knew how to put on. “Come! Will you not like to ride a little way with me in my beautiful chariot?”

Reducing the myth to a 19th century version of ‘don’t get into cars with strange men’, Hawthorne tells how King Pluto (something of a spoiled Byronic rich boy) makes off with the ‘child’ Proserpina and takes her into his underground kingdom, where she refuses to eat. Archly, Hawthorne explains that if only King Pluto’s cook had provided her with ‘the simple fare to which the child had been accustomed’, she would probably have eaten it, but because ‘like all other cooks, he considered nothing fit to eat unless it were rich pastry, or highly-seasoned meat’ – she is not tempted. In the end, of course, Mother Ceres finds her daughter, and Jove sends ‘Quicksilver’ to rescue her but not before (‘Dear me! What an everlasting pity!’) Proserpina has bitten into the fateful pomegranate – and her natural sympathy for the gloomy King Pluto leads her to declare to her mother, ‘He has some very good qualities, and I really think I can bear to spend six months in his palace, if he will only let me spend the other six with you.’

And lo, the happy ending. Prettified as this is, no one would guess that Persephone – whose name means 'she who brings doom’ – was one of the most significant of Greek goddesses. In Homer, it is to her kingdom which Odysseus sails:

Sit still and let the blast of the North Wind carry you.But when you have crossed with your ship the stream of the Oceanyou will find there a thickly wooded shore, and the groves of Persephone,and tall black poplars growing, and fruit-perishing willows;then beach your ship on the shore of the deep-eddying Oceanand yourself go forward into the mouldering home of Hades.

The Odyssey of Homer, Book X, tr. Richmond Lattimore, Harper & Row, 1965

As Demeter’s daughter, she is originally named simply ‘Kore’ or ‘maiden’. When Kore is stolen away, Demeter searches for her throughout the earth, finally stopping to rest at Eleusis, outside Athens. There, disguised as an old woman, she cares for the queen's son, bathing him each night in fire so that he will become immortal. When the queen finds out, she interrupts the procedure and the child dies. The angered goddess throws off her disguise, but in recompense teaches the queen's other son, Triptolemos, the art of agriculture. Meanwhile, since the crops are dying and the earth will remain barren until Demeter's daughter is restored, Zeus persuades Hades to return Kore to her mother - so long as no food has passed her lips. But Hades has tricked Kore into eating some pomegranate seeds, and she must therefore spend part of every year in Hades. Kore emerges from the underworld as Persephone, Queen of the dead. And a temple is built to Demeter and Persephone at Eleusis, which every year will host the Great and the Lesser Mysteries. The participants would:

[walk] the Sacred Way from Athens to Eleusis calling for the Kore and re-enacting Demeter's search for her lost daughter. At Eleusis they would rest by the well Demeter had rested by, would fast, and would then drink a barley and mint beverage called Kykeon. It has been suggested that this drink was infused by the psychotropic fungus ergot and this, then, heightened the experience and helped transform the initiate. After drinking the Kykeon the participants entered the Telesterion, an underground `theatre', where the secret ritual took place. Most likely it was a symbolic re-enactment of the `death' and rebirth of Persephone which the initates watched and, perhaps, took some part in. Whatever happened in the Telesterion, those who entered in would come out the next morning radically changed. Virtually every important writer in antiquity, anyone who was `anyone', was an initiate of the Mysteries.

(Professor Joshua J. Mark on the Eleusinian Mysteries, at this link: http://www.ancient.eu.com/article/32/)

The story really does contain all those mythic, seasonal references. While Persephone is in the underworld, the plants wither and die; there are the scattered flowers dropped by the stolen girl, there are the significant pomegranate seeds: but this is much more than a pretty fable. It’s a sacred story which conveyed to the initiate the promise and comfort of life after death.

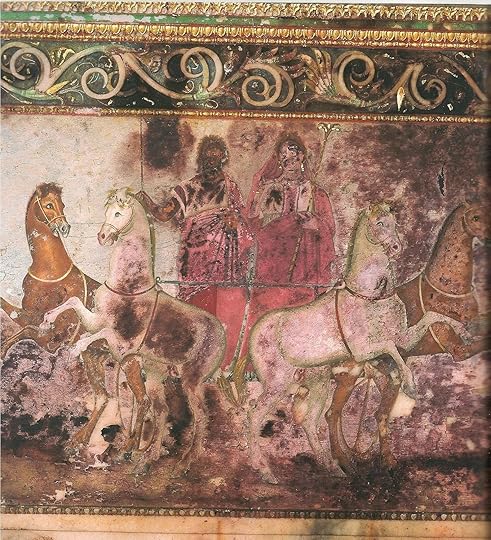

A couple of years ago, I went to see an exhibition of treasures from the royal capital of Macedon, Pella, at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. The treasures were dazzling, and the exhibition also included photographs of the lavish interiors and furnishings of the royal tombs of Philip II (father of Alexander the Great) and his family, at Aegae. In the tomb of Philip’s mother, Euridike, was a fabulous chair or throne. On its seat had rested the chest containing the Queen’s burned bones, wrapped in purple...

...while on the back of the throne is a painting depicting Hades and Persephone riding together in triumph on their four-horse chariot. In another tomb at Aegae, Demeter is shown lamenting the loss of Persephone, while on another wall, Hades carries her off. For me, it seems these images are being used in much the same way that we would place a cross on a Christian tomb. They are not merely referencing, but calling upon a significant myth, a myth with immediate, emotional potential, a myth that speaks of life beyond the doorway of death.

Although these tombs belong to the Classical era, in many ways the Macedonian royals had more in common with the heroic Mycenean age of a thousand years earlier. Many Macedonian consorts acted as priestesses as well as queens. At the funeral pyre of Philip II, in 336 BC, it’s startling to learn that his youngest wife, Queen Meda, went to the flames with him, along with the dogs and horses which were also sacrificed. But she was quite likely a willing victim. Dr Angeliki Kottaridi explains; ‘According to tradition in her country, [this] Thracian princess followed her master, bed-fellow and companion forever to Hades. To the eyes of the Greeks, her act made her the new Alcestes [in Greek mythology, a wife who died in her husband’s place] and this is why Alexander honoured her so much, by giving her, in this journey of no return, invaluable gifts’ – for example, a wreath of gold myrtle leaves and flowers:

Dr Angeliki Kottaridi again:

In the Great Eleusinian Mysteries, Demeter gave to mankind her cherished gift, the wisdom which beats death. With the burnt offering of the breathless body, the deceased, like sacrificial victims, is offered to the deity. Through their golden bands [pictured below] the initiated ones greet by name the Lady of Hades, the ‘fearsome Persephone’. …Purified by the sacred fire, the heroes – the deceased – can now start a ‘new life’ in the land of the Blessed; in the asphodel mead of the Elysian Fields.

Dr Angeliki Kottaridi: “Burial customs and beliefs in the royal necropolis of Aegae”, from ‘Heracles to Alexander the Great, Treasures from the Royal Capital of Macedon’, Ashmolean Museum, 2011

For me, one of the most moving items in the exhibition was this small leaf-shaped band of gold foil, 3.6 cm by 1 cm. Upon it is impressed the simple message:

For me, one of the most moving items in the exhibition was this small leaf-shaped band of gold foil, 3.6 cm by 1 cm. Upon it is impressed the simple message: ΦΙΛΙΣΤΗ ΦΕΡΣΕΦΟΝΗΙ ΧΑΙΡΕΙΝ

Philiste to Persephone, Rejoice!

And I wonder, I wonder about that leaf-shape. The goldsmiths of Macedon were unrivalled at creating wreaths – of oak leaves and acorns, or of flowering myrtle that look as though Midas has touched the living plant and turned it to gold. Would such artists really have used any old ‘leaf shape’ – or is this slim slip a gold imitation of the narrow leaf of the willow – the black, ‘fruit-perishing willows’ which Homer tells us fringe the shores of Persephone’s kingdom?

Photos of Macedonian tomb and goods from Heracles to Alexander the Great, Treasures from the Royal Capital of Macedon’, Ashmolean Museum, 2011

Published on May 03, 2014 04:23

April 20, 2014

"It's not just an [insert genre] book..."

I went into ‘The Last Bookshop’ in Oxford the other day, which sells what I assume (?) are remaindered books, since everything in the shop, regardless of size or original price, is sold for two pounds. I buy books regularly enough that I don’t feel guilty about getting them cheap from time to time: and anyway the selections here are sometimes more interesting than what is to be found in the chains. Which proved to be the case as I pounced with delight upon this:

It’s the third in a series of horse books for children, 'The Horses of Oak Valley Ranch', by Jane Smiley, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of ‘A Thousand Acres’. I have the first two in the US hardcover editions: ‘A Good Horse’ and ‘The Georges and the Jewels’. Faber and Faber in the UK have changed these titles - in a way that links them more clearly as a series - to the more generic ‘Secret Horse' and ‘Nobody's Horse’. ‘Mystery Horse’ is called ‘True Blue’ in the States, and there are two more, which I look forward to reading.

US title/cover

US title/cover

UK title/coverTake a look at the UK cover of 'Mystery Horse' - the gorgeous galloping grey horse against the blue sky, with a blue foil title, and little blue and pink foil flowers scattered around. Any pony-mad child would want it. And then – well, then they might find this is more than your average pony story.

UK title/coverTake a look at the UK cover of 'Mystery Horse' - the gorgeous galloping grey horse against the blue sky, with a blue foil title, and little blue and pink foil flowers scattered around. Any pony-mad child would want it. And then – well, then they might find this is more than your average pony story. Set in 1960’s California, the books follow the story of a young girl, Abby, growing up in a fundamentalist Christian family. Her father is a horse trainer and dealer, and Abby spends much of her free time outside school helping him work with the horses. Her mother and father are loving parents but her father in particular is unbending in his outlook, and her elder brother Danny has left home after a particularly bitter row.

Smiley’s treatment of the family and its predicament is sympathetic and nuanced. As Abby is the narrator, we see her father through her eyes: stubborn, hardworking, fair according to his lights, rigid in his beliefs but – over the course of the first three volumes – able finally to compromise and come to terms with his son’s independence. In the meantime Abby begins to navigate her own way through life. Observing her father’s strengths and weaknesses, she learns how to trust herself, to question her parents’ views without loss of love or respect, and to come to her own conclusions.

US title/cover

US title/cover

UK title/cover And YES, there is a lot about horses. Horses, Smiley suggests, are much like people. When her father, a church elder, wants to discipline the disruptive young sons of a church family, Abby points out that whipping a child can be as counterproductive as whipping a horse:

UK title/cover And YES, there is a lot about horses. Horses, Smiley suggests, are much like people. When her father, a church elder, wants to discipline the disruptive young sons of a church family, Abby points out that whipping a child can be as counterproductive as whipping a horse: “I think they [the boys] are like Jack, not like Jefferson. If we whipped Jack, it wouldn’t make him stop running. It would make him run faster. If we whipped Jefferson, he might not run at all. He might just stop and buck.”

Mom reached over and smoothed my hair. Dad didn't say anything, and we drove the rest of the way home.

As if all this wasn’t enough, ‘Mystery Horse’/’True Blue’ is also a remarkably good ghost story: unsettling, spooky, beautiful and ultimately all about Abby – so that the ghostly bits are integral to the narrative and not some tacked-on extra thrill.

As an adult, I love these books. I love the detailed and thoughtful accounts of grooming, training and riding these horses which – because they are all for sale – often don’t even have individual names, in case anyone gets too attached to them. I love the fact that there can be whole chapters set in church – the ‘church’ which is all this small faith group can afford, a featureless rented space in a shopping mall. I love the thoughtfulness with which Jane Smiley navigates Abby’s world. The ways in which school and home life clash: textbooks which mention evolution and therefore cannot be shown to Daddy, or Mom’s horror on discovering that in a history lesson, Abby has been constructing cardboard models of Spanish missions.

‘“You built a Catholic mission?” “We all did.”’

It’s done with a light, almost comedic touch, but can become serious. ‘“So,” said Daddy' [to Daniel, at the beginning of their quarrel]. “Some boys who taught you to take the holy name of the Lord in vain are going to pick you up and take you to see a fantasy movie about evil and hate. Am I right?”’ Other kids are allowed to go to movies and listen to the Beatles. Abby doesn’t exactly miss these activities, but she knows that not having them makes her different.

I love all of this. But would a child?

Well, it depends on the child. And this is where the title for this post comes in. Genre fiction has an undeserved bad name. Horse and pony books. School stories. Crime. Romance. Historical novels. Science fiction. Fantasy. Children’s books. If you can put it in a category, it must somehow be less than a ‘real’ novel. ‘It’s just a pony book.’ ‘It’s just a school story. ‘It’s just a romance.’

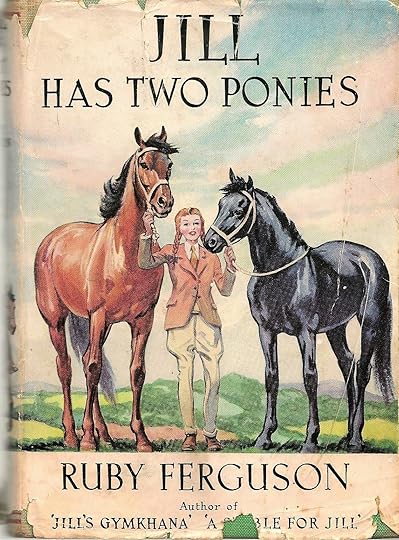

It’s true that there are many pony books, school stories or adventure stories which are hardly great literature, however that may be defined. But not every plain old novel is great literature either. I’m not denigrating the many, many pony books I read as a child just because, as an adult, I no longer find them so interesting. The ‘Jill’ books by Ruby Ferguson, for example, kept me enthralled when I was ten or eleven. They are fun, they are lively. They do one single thing: tell an entertaining story and tell it well. That is good in itself.

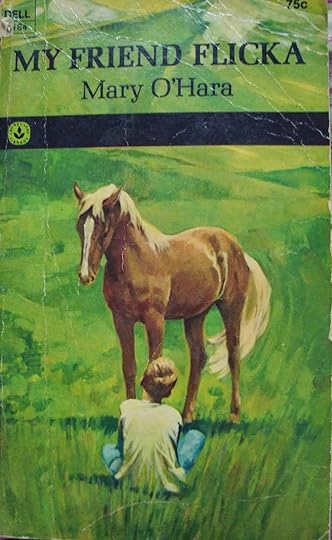

But there are books which do more, which are multi-dimensional. Mary O’Hara’s ‘My Friend Flicka’ and ‘Thunderhead’ and ‘Green Grass of Wyoming’ are multi-dimensional. They offer a richness – of characterisation, of description, of emotional intelligence – which the ‘Jill’ books don’t have and never aspired to. KM Peyton’s ‘Flambards’ and ‘Fly By Night’ and ‘The Team’ are multi-dimensional. In the genre of ‘school story’, Enid Blyton’s ‘Malory Towers’ and ‘St Claire’s’ stories offer the child reader excellent ripping yarns, unashamed fantasies of the fun and frolics of boarding-school life. But Antonia Forest’s school stories ('Autumn Term' and its sequels) are multi-dimensional. They offer more: depth of character, growth, change, consideration of topics such as religion, censorship, responsibility, and the unwitting cruelty of schoolchildren to persons they dislike.

And yes, I loved all of them indiscriminately, but the ones I read and reread and have kept reading into adult life are the multi-dimensional books. I knew even back at the age of eleven or twelve or thirteen that I was getting far, far more out of ‘My Friend Flicka’ than I was getting out of ‘Jill’s First Pony’. Mary O’Hara was talking about stuff that was important to me. My father and my brother, much as they loved each other, used to argue. There were misunderstandings, jealousies, quarrels which sometimes burst around us with the violence of a thunderstorm. In ‘My Friend Flicka’ and its sequels, the dreamy boy Ken and his impatient, practical father are also negotiating a difficult relationship punctuated by storms. That story intertwines with the story of Ken’s love for his little horse, and is equally important.

And yes, I loved all of them indiscriminately, but the ones I read and reread and have kept reading into adult life are the multi-dimensional books. I knew even back at the age of eleven or twelve or thirteen that I was getting far, far more out of ‘My Friend Flicka’ than I was getting out of ‘Jill’s First Pony’. Mary O’Hara was talking about stuff that was important to me. My father and my brother, much as they loved each other, used to argue. There were misunderstandings, jealousies, quarrels which sometimes burst around us with the violence of a thunderstorm. In ‘My Friend Flicka’ and its sequels, the dreamy boy Ken and his impatient, practical father are also negotiating a difficult relationship punctuated by storms. That story intertwines with the story of Ken’s love for his little horse, and is equally important. Maybe some children don’t like these multi-dimensional books, maybe some children – perhaps even many children? – become bored, impatient, wanting simply to get on with the story. But there will be other children who want more, who are already thinking, already asking questions about life, who will appreciate finding these questions taken seriously in the middle of a book ‘about’ horses or school. A multi-dimensional book always gives the reader more than they expected.

Am I simply saying that genre books can be good novels? Of course I am. But it’s more than that. It’s a plea. The next time you read an excellent horse story or school story or fantasy, try not to say in its praise, ‘It isn’t just a pony book/school story, of course…’ as if somehow it needs to be extracted from its lowly niche before it can be appreciated. Worse still, don’t say, ‘It’s not really a pony book/school story/children’s book at all!’

Because if you do, if everyone who ever reads and loves a ‘genre’ book feels they have to rescue it from its category before praising it, then what is left? Every category of books – novels, children’s fiction, popular science, you name it – contains a multiplicity of less or more able writers, and we should remember it's better do something simple and do it well, than to aim high and fail. If somebody says, as someone recently said to me, ‘But Ursula le Guin’s books aren’t really fantasies’, how is that a compliment to le Guin, who chose to employ her wonderful talents in the field of sci-fi and fantasy? All it really proclaims is the reader’s embarrassment at having enjoyed a book belonging to a genre which they believe - in spite of the evidence before their eyes - to be second-rate.

Either we need to do away with categories and genres altogether – which isn’t going to happen – or we need to stop being embarrassed and apologetic, and be ready to recognise and celebrate good work in whatever field it happens to grow. Loud and clear: there are excellent pony books, there are excellent school stories, there are excellent fantasies, and there are excellent children’s books. Their excellence is no different in kind from that of any other writing. So, yes! Unsurprisingly, Jane Smiley's series of horse stories is truly excellent. Any child or adult who picks them up will learn much – about horses, and about life.

Published on April 20, 2014 07:17

April 5, 2014

The Colours in Fairytales

It’s usual for collections of fairytales to include pictures. When I was very small, the simple retellings I was able to read were full of lavish colour illustrations like this one by Rene Cloke. It's very pink...

The Andrew Lang collections, the Red, the Green, the Violet, theYellow Fairybooks had their intricate Victorian engravings (which I longed to colour in). I read the tales of Hans Christian Andersen with wonderful watercolour illustrations by Edmund Dulac:

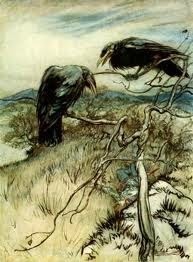

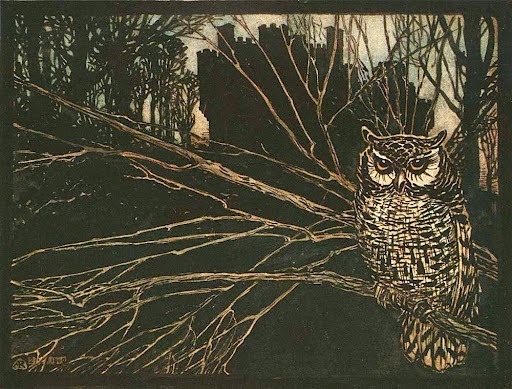

I borrowed from the library Grimm’s fairytales with pictures by Arthur Rackham.

But fairystories don’t actually needillustrations. They contain their own colours, brilliant as any medieval painting. As red as blood, as black as ebony, as white as snow.

In his book ‘An Experiment in Criticism’ CS Lewis talks about good and bad writing, and the possible differences between them. (I know this sounds as if I'm heading off at a tangent, but bear with me.) He suggests that some readers prefer bad writing because they do not want or are not interested in the things which good writing can provide: richness of experience, for example, or depth of thought. Some readers simply want the action, the page-turning, the next thing. And this explains the popularity of the airport thriller, and of Dan Brown.

For such a reader, Lewis says, good writing will be either too rich or too bare for his purposes.

A woodland scene by DH Lawrence or a mountain valley by Ruskin gives him far more than he knows what to do with; on the other hand, he would be disappointed with Malory’s ‘he arrived afore a postern opened towards the sea, and was open without any keeping, save two lions kept the entry, and the moon shone clear.’ Nor would he be content with ‘I was terribly afraid’ instead of ‘my blood ran cold’. To the good reader’s imagination such statements of the bare facts are often the most evocative of all. But the moon shining clear is not enough for the unliterary. They would rather be told that the castle was ‘bathed in a flood of silver moonlight’.

I’m not concerned here with Lewis’s thesis about different types of reading (I think he’s right, but I also think all of us can be ‘good’ and ‘bad’ readers: I have days when I can be that attentive, sensitive reader Lewis applauds and other days when I simply feel lazy). But I do want to point out that fairytales – traditional fairytales – tend like Thomas Malory's Morte D'Arthur to be economical with description.

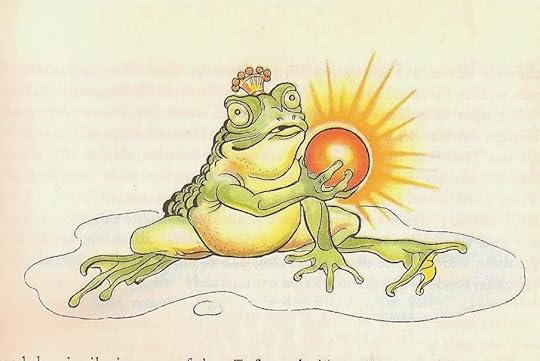

In olden times, when wishing still helped one, there lived a king whose daughters were all beautiful, but the youngest was so beautiful that the sun itself, which has seen so much, was astonished whenever it shone on her face. Close by the King’s castle lay a great dark forest, and under an old lime-tree in the forest was a well, and when the day was very warm, the King’s child went out into the forest and sat down by the side of the cool fountain; and when she was bored she took a golden ball, and threw it up on high and caught it.

The Frog-King

Lovely as it is, the phrase ‘so beautiful that the sun was astonished’ does not tell us what the king’s daughter looks like. Hardly any modern writer who might wish to turn The Frog-King into a novel could resist providing more. The princess would have to be given a name. We would learn what colour her hair and eyes are, whether her nose turns up at the end, what she wears. In the inevitable process of extending and elaborating the tale, the writer would have to try very hard to avoid literary clichés.

A fairytale does not have to try hard. In keeping everything simple, it also keeps everything fresh. ‘Close by the King’s castle lay a great, dark forest’ leaves almost everything to your imagination, and then comes the ‘old lime tree’ and the cool well, and that’s as much as anyone needs to know. A novelist might add a description of the well, providing it with a carved marble parapet or a rustic stone wall. It might be beautifully written and very fine – but in a fairytale, it would merely get in the way.

Yet how is a simile like ‘as green as grass’ or ‘as black as coal’ less of a cliché than ‘bathed in a flood of silver moonlight’? In my opinion, because they are so brief. They leave the imagination free. ‘Red as blood’. The colour flashes on the inward eye in all its familiar, potent brilliance - and is gone. What else can ‘red’ be as red as? Strain after another comparison as much as you like, you’ll not do better.

Colours in fairytales are strong, simple, basic, and meaningful.

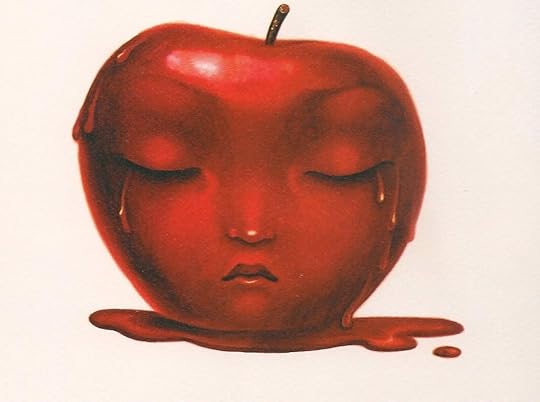

The Queen at her Window: 'Blanche-Neige' illustrated by Benjamin Lacombe, Milan Jeunesse, 2011

The Queen at her Window: 'Blanche-Neige' illustrated by Benjamin Lacombe, Milan Jeunesse, 2011Once upon a time in the middle of winter, when the flakes of snow were falling like feathers from the sky, a Queen sat at a window sewing, and the frame of the window was made of black ebony. And whilst she was sewing and looking out of the window at the snow, she pricked her finger with the needle, and three drops of blood fell upon the snow. And the red looked pretty on the white snow, and she thought to herself, ‘Would that I had a child as white as snow, as red ad blood, and as black as the wood of the window-frame.’

Little Snow-White

In spite of the 'Sleeping Beauty' picture at the top of this post, you don’t get pink in fairytales. You don’t get purple. Yellow is rare. But there is white snow, white linen, white snakes, white doves, white swans, white feathers. Red blood, and roses as red as blood. There are green branches in dark forests. Black ravens, black ebony, black coal. Golden hair, golden straw, golden crowns, golden spinning wheels.

The dove said to her, ‘For seven years must I fly about the world, but at every seventh step that you take I will let fall a drop of red blood and a white feather, and these will show you the way.’

The Singing, Soaring Lark

White, black and red are meaningful colours because they are rare in nature and therefore noticeable. White is the colour of innocence, the colour of an untrodden fall of snow under which the whole landscape is transformed. A white dove is an emblem of peace, a black raven a signifier of wisdom. In some variants of Snow-White, it is a raven which the queen sees against the snow, a more likely and a sharper contrast than an ebony window-frame. Black is unusual. Most birds are brownish: even today with our dulled attention to nature, we notice black crows and white swans. Before chemical dyes, black was an expensive colour for clothes: it stood out: most people could not afford to wear it. And red of course is the most meaningful of all colours, the most emotionally charged. Red is the colour that accompanies childbirth, wounds, war, accidents. Red is the stuff of life and death.

'Blanche-Neige' illustrated by Benjamin Lacombe

'Blanche-Neige' illustrated by Benjamin LacombeGold is the colour of the sun, or perhaps it should be the other way around: the sun is more glorious than gold. The princess in The Singing, Soaring Lark wears a dress ‘as brilliant as the sun itself’, while the heroine of The Black Bull of Norroway cracks open nuts to reveal dresses the colours of the sun, moon and stars. Gold stands for luck, goodness, happiness and fortune.

Blue, the colour of the sky, is strangely rare in fairytales. Apart from the eerie, supernatural blue light – the witch-light – in the story of that name, the only instance I can find is a sad little tale about a toad in which the blue object is artificial, a handkerchief:

An orphan child was sitting by the town wall spinning, when she saw a paddock coming out of a hole low down in the wall. Swiftly she spread out beside it one of the blue silk handkerchiefs for which paddocks have such a liking, and which are the only things on which they will creep. As soon as the paddock saw it, it went back, then returned, bringing with it a small golden crown…

Tales of the Paddock, II

Colours in fairytales aren’t decoration, they aren’t even ‘just’ descriptive. They carry information. They are a form of emphasis. And they can be relied upon. A golden head which rises to the surface of a well may be strange, but won't be evil. Magical and just, it gives the same advice to both the good and the selfish girls: it is their own natures which will bring good or bad fortune. A girl who can ask a hazel tree to shake gold and silver down upon her is sure to prove fortunate. A white dove will aid the innocent even as it pecks out the eyes of the guilty.

Here’s a poem, into which I tried to work the colours of fairytales.

FAIRYTALE

Out from the pine forest stepped

the bowing yellow dwarf, and stopped the prince,

who - half despairing - told him everything.

If the bent woman, walking backwards, sets you

to sweep the green pins with an old owl's feather,

and call up storm clouds in the fine June weather,

and ride the yellow colt of your last nightmare -

what can you do but sigh and tell your story

to the first kindly stranger who has met you?

'Tell me,' the dwarf said, 'what of your princess?'

'Oh, turned into a brown thrush long ago

she sits and sings in a fine gilded cage,

and every spring she lays a pure blue egg,

which, hatched, displays a tiny golden crown.

That's why you see me wandering alone:

for hills of glass and plains of knives spring up

behind, and hinder me from turning back.'

'Where's your white horse? Your squire, young Constant Jack?'

'Jack used to fret me - always making speed.

He rode my white horse red towards the wars

a long time back. Today, I have no doubt,

sheep graze the fine new grass between their bones.'

'Ah?' said the dwarf. 'And so you're quite alone?'

'Alone. And burdened with confusing tasks.'

Then, pointing where the green ride ducked and dipped

to twist behind the dense pine barrier:

'Now,' said the dwarf, smiling, 'keep on till dark...'

Published on April 05, 2014 06:16

April 1, 2014

Folklore snippets: Yeats on Irish fairies

From: ‘Irish Fairies, Ghosts, Witches’ in ‘Lucifer’, 1889

William Butler Yeats

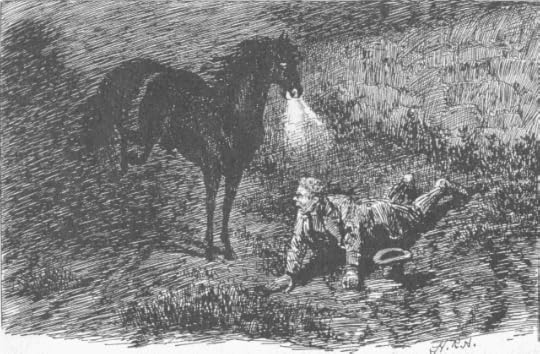

The Pooka seems to be of the family of the nightmare. He has most likely never appeared in human form… His shape is that of a horse, a bull, goat, eagle, ass, and perhaps of a black dog, though this last may be a separate spirit. The Pooka’s delight is to get a rider, whom he rushes with through ditches and rivers and over mountains, and shakes off in the grey of the morning. Especially does he love to plague a drunkard – a drunkard’s sleep is his kingdom.

The Dullahan is another gruesome phantom. He has no head, or carries it under his arm. Often he is seen driving a black coach, called the coach-a-bower [Irish Cóiste-bodhar: deaf or dead coach], drawn by headless horses. It will rumble to your door, and if you open it, a basin of blood is thrown in your face. To the houses where it pauses, it is an omen of death. Such a coach, not very long ago, went through Sligo in the grey of the morning (the spirit hour). A seaman saw it, with many shudderings. In some villages its rumblings are heard many times in a year.

The Leanhaun Shee (fairy mistress) seeks the love of men. If they refuse, she is their slave; if they consent, they are hers, and can only escape by finding another to take their place. Her lovers waste away, for she lives on their lives. Most of the Gaelic poets, down to quite recent times, have had a Leanhaun Shee, for she gives inspiration to her slaves. Her lovers, the Gaelic poets, died young. She grew restless, and carried them away to other worlds, for death does not destroy her power.

Published on April 01, 2014 01:36

March 28, 2014

'Daughters of Time' at the Oxford Festival

This coming Sunday, 30th March, 2.00 pm, I'm heading for the Oxford Literary Festival to join my fellow authors Mary Hoffman, Penny Dolan, Leslie Wilson and Celia Rees who will be talking about this book, 'Daughters of Time'. We're all founding members of The History Girls blog, created by Mary Hoffman to celebrate historical writing, fiction and non-fiction, from a female perspective. We were thrilled when she suggested that some of us might get together to write a series of children’s stories centred around significant women in British history. In the end, thirteen of us took up the challenge: too many to fit on one panel! So I've got the easy job of sitting in the audience - but I'll be there to help sign books at the end. Why did we feel this book was important? Growing up in the 1960’s, the history taught to me at school was mostly about men. I heard of few women role models. When sibling rivalry between me and my younger brother descended a level or two, we might wrangle about whether ‘girls are as good as boys’ or ‘boys are better than girls’, but if he challenged me with ‘Why are there more famous men than women, then?’ my arsenal was small. Queen Elizabeth the First. Grace Darling. Joan of Arc (though being burned at the stake was hardly something to aim for). Um. Queen Victoria? – a dull old lady who wore black and was not amused? Not very inspiring to a child. I knew of only one woman scientist, Marie Curie (culled from the pages of my Grandma’s ‘Reader’s Digest Book of Famous Lives’, I was a child who read everything). Famous authors? – well, I knew about the Brontes. And that was about it.

True, I devoured the historical books of Geoffrey Trease who usually had a brave, cross-dressing heroine adventuring alongside the young hero. But that wasn’t real. Rather gloomily I supposed that women didn’t have adventures.

How wrong I was. And ‘Daughters of Time’ amply demonstrates it. When we came to decide who we should pick, we were spoiled for choice: we had heated discussions about which women to include: we could have written three anthologies, never mind one! (Some of the names which had, inevitably, to be left out are listed at the back of the book). Among us, we wrote about queens, visionaries, reformers, political thinkers, dramatists, scientists, pilots and activists. And I knew immediately who I wanted to write about: Lady Julian of Norwich.

Lady Julian, a medieval visionary and anchorite who spent perhaps thirty years of her life walled up in a small stone room or ‘cell’ at the back of St Julian’s Church in Norwich, may seem a strange character to offer to readers of nine plus. But she was an amazing person, strong, sane and compassionate. She is the author of the very first book known to have been written in English by a woman – ‘Showings of God’s Love’, in which she vividly recounts her visions. It’s a very good book, too – full of imagery drawn from everyday life, as when she describes how God showed her ‘a little thing, the size of a hazelnut’ on the palm of her hand, and when she asked what it was, told her, ‘It is all that is made’. And she has a wonderfully feminist take on religion, describing God as a Mother who tenderly cares for us: ‘for when a child is in trouble or scared, it runs to its mother for help as fast as it can’.

Julian’s message down the centuries is one of hope. ‘All shall be well,’ God promised her. We still need to hear that message, and that was why I chose it as the title of my story in which twelve year-old Sarah, Lady Julian’s new little maidservant, battles with homesickness and grief.

Published on March 28, 2014 03:42

March 21, 2014

The Great Selkie of Sule Skerry

An airthlie nourrice sits and sings,

And aye she sings, Ba lily wean!Little ken I my bairnis fatherFar less the land that he staps in.

So begins the old ballad of 'The Great Selkie of Sule Skerry'. As Laura Marjorie Miller discussed a few weeks ago in her guest post here, most selkie tales – or at least, most of those familiar to a modern audience – concern a seal woman who is captured or taken to wife by a mortal man, usually a fisherman who spies her dancing in mortal form on a moonlit beach and steals her sealskin robe, so preventing her from returning to her kindred in the sea.

In Margo Lanagan’s thought-provoking ‘Sea Hearts’ (UK title 'The Brides of Rollrock Island’), the men of the island take beautiful, passive, mournful selkie brides in preference to ordinary human women, but this communal act of selfish, sexual exploitation rebounds upon them. The men cut themselves off from genuine relationships, and they and their children suffer from the seal women’s terrible, unspoken grief.

My own 'Troll Mill' (the second part of 'West of the Moon'), opens when a fisherman’s wife, Kersten, thrusts her newborn baby into the arms of the young hero, Peer, and flings herself into the sea. Hampered by the baby in his arms, Peer tries to stop her:

Rain slashed into his eyes. His feet skated on wet grass, sank into pockets of soft sand. She was on the beach now, running straight down the shingle to the water. Peer skidded to a crazy halt. He couldn’t catch her. He saw Bjørn, bending over the boat, doing something with the nets. Peer filled his lungs and bellowed, ‘Bjørn!’ at the top of his voice. He pointed.

Bjørn’s head came up. He turned, staring. Then he flung himself forwards, pounding across the beach to intercept Kersten. And Kersten stopped. She threw herself flat and the wet sealskin cloak billowed over her, hiding her from head to foot. Underneath it, she continued to move in heavy, lolloping jumps. She must be crawling on hands and knees, drawing the skin cloak closely around her. She rolled. Waves rushed up and sucked her into the water. Trapped in those encumbering folds, she would drown.

‘Kersten!’ Peer screamed. The body in the water twisted, lithe and muscular, and plunged forward into the next grey wave.

Writing 'Troll Mill', I found myself exploring various themes of possession – can one possess a child? – a wife? – another person? – and motherhood. I wanted to explore the paradoxical selfishness of a ‘good’ and likeable man, Bjørn, who has used love as an excuse for trapping the woman he wants. And I saw the selkie’s return to the sea, abandoning her child, as a metaphor for post natal depression.

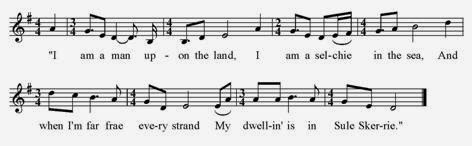

'The Great Selkie of Sule Skerry' differs from the ‘selkie bride’ legends insofar as the selkie in question is not female, but male. The earliest known version was collected by Captain F.W.L. Thomas of the Royal Navy, who heard it sung by ‘a venerable lady of Snarra Voe, Shetland’ some time around 1852: he sent it to The Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. Later in the century it made it into Child’s Ballads, number 113, and an original tune for it was collected in 1938 by Professor Otto Andersen on the island of Flotta, Orkney, who heard it sung by John Sinclair:

Sadly I can’t find a recording. The best known tune for the ballad was written by James Waters in the late 1950s (sung below by Joan Baez).

As with most stories of human/otherworldly liaisons, in 'The Great Selkie of Sule Skerry' things have gone wrong from the very start. The ballad opens with the ‘airthly nourrice’ – the mortal woman nursing her child – lamenting that she doesn’t know who his father is. ‘Little ken I my bairn’s father, far less the land that he dwells in’. It’s easy to let the beautiful tune sweep you away into a pleasant mood of romantic melancholy. But stop, stop and think! What does it mean, when a woman doesn’t know who her child’s father is? How can that happen? It can happen if that woman has been raped. There’s a lot of rape in ballads, much of it quite casual, probably reflecting everyday life.

So here’s this woman, this unnamed woman, rocking and nursing her child, not knowing who his father is, and then something fearful happens.

Then ane arose at her bed-fitAnd a grumlie guest I’m sure was he:‘Here am I, thy bairnis father,Although I be not comelie’.

‘One arose at her bed foot’ – in her home, in her bower, into the safe place where she’s nursing her child, there emerges, surges up like an apparition from the foot of the bed, this grim, rough creature which once forced itself upon her. (The illustration by Vernon Lee, above, powerfully suggests the uncanny terror of the moment.) And he acknowledges her child as his. And he tells her the terrible truth: he’s not even human, and if he has a home at all other than the wild sea, it’s only a tiny rock far out in the North Atlantic, far from land.

I am a man, upo’ the lan,An I am a silkie in the sea,And when I’m far and far frae lanMy hame it is in Sule Skerrie.’

The woman reproaches him. ‘It wasna weel,’ she says, ‘That the great Silkie of Sule Skerrie should come and aught a child to me.’ But in response, this happens.

And he has ta’en a purse of goldAnd he has put it upo’ her knee,Saying ‘Gie to me my little young sonAnd tak thee up thy nourris-fee.’

He’s paying her off, flinging money into her lap. ‘Pick up your money and give me my son.’ It’s like a blow to the face; his indifference to her is chilling. This is not a happy story, and the selkie, being a supernatural creature, has the gift of foreseeing how it will all end: badly. One summer day, ‘when the sun shines hot on every stone’, he will take his little half-mortal son ‘and teach him how to swim the foam’. But by this time the woman will have married a man who can shoot with a gun. (I wonder if when this ballad was new, guns were new too?) At any rate, either by accident or by design, he will shoot both the selkie and his son.

An it sall come to pass on a simmer’s dayWhen the sin shines het on evera staneThat I will tak my little young sonAnd teach him for to swim the faem.

An thu sall marry a proud gunner,An a proud gunner I’m sure he’ll be,And the very first schot that ere he schoots,He’ll schoot baith my young son and me.

What was the point of it all, then? If it was always going to end in such tragedy? Why did the selkie take the woman in the first place, why did he father her child? You might as well ask, ‘What is the point of “Hamlet”?’ The ballad is a song, a poem, and if it’s about anything it’s about the harshness and unfairness of the world, and the brevity and beauty of life. The best moments are in the last-but-one verse: it’s full of light: the glorious heat of the sun on the shoreline stones in the short, bright northern summer, and the sensuous joy and tenderness of the bond between the selkie and his ‘little young son’ as he teaches him to ‘swim the foam’. Those are the moments that make the story bearable – and surely, the ballad says, those are the moments which make human life bearable, however brief it may be.

Joan Baez' haunting version of 'The Great Selkie of Sule Skerry', tune by James Waters.

Picture credit: Vernon Hill's illustration of the tale. From Richard Chope's 1912 collection Ballads Weird and Wonderful

Published on March 21, 2014 03:13

March 13, 2014

Self-created fantasy worlds

Many children and teenagers develop their own private fantasy worlds. I had one. Age nine, I was the imaginary leader of the red horses of the sunset clouds... my name: ‘Red-Gold’. My friend was the leader of the white summer clouds (‘Cloud’); our adversary, the black horses of the thunder. It was obvious enough (you can tell I was horse mad!) but it gave me much pleasure and sent me off to sleep composing adventures. For a feel for the intensity of the thing, here’s a prose poem I wrote about it when I was just thirteen:

And out of the mist come horses galloping, born of the wind with wings like to it, dancing and running, plunging through the cool air, out of the golden, out of the glory, straight from the sun as it shines through the mist: dazzling, glorious, horses of the morning, horses of the sunrise, horses of the dawning, shining horses of the steel-blue sky.

My head may have been almost literally in the clouds, but I don't believe it did me any harm at all. But here are three interesting books which study the effects of fantasy worlds built by young people, and ask what purposes they serve for good and for ill.

The first and earliest is ‘Peter’s Room’ by Antonia Forest, published in 1961, part of her series of novels/school stories about the Marlow family which began with ‘Autumn Term’(1948). Forest was a writer who transcended genre, and her well-characterised, insightful stories (now reprinted by Girls Gone By) are well worth attention. In this one, set during the Christmas holidays, the younger Marlows and their friend Patrick begin using an old stable loft (‘Peter’s room’) as their daily meeting-place. Inspired by the Brontë sisters’ Angria and Gondal, they pass the time by inventing an imaginary world with themselves as characters – role-playing, if you like. Gradually, their fantasy characters begin to exert influence on their real lives. It nearly ends in disaster.

The first and earliest is ‘Peter’s Room’ by Antonia Forest, published in 1961, part of her series of novels/school stories about the Marlow family which began with ‘Autumn Term’(1948). Forest was a writer who transcended genre, and her well-characterised, insightful stories (now reprinted by Girls Gone By) are well worth attention. In this one, set during the Christmas holidays, the younger Marlows and their friend Patrick begin using an old stable loft (‘Peter’s room’) as their daily meeting-place. Inspired by the Brontë sisters’ Angria and Gondal, they pass the time by inventing an imaginary world with themselves as characters – role-playing, if you like. Gradually, their fantasy characters begin to exert influence on their real lives. It nearly ends in disaster.Forest was writing with unusual foresight about the seductive power of role-playing (think Second Life) – but also, the book is about the creative process – the way characters develop lives of their own and often take their authors and creators in unexpected directions. When Patrick’s ‘avatar’, the heroic sounding ‘Rupert Almeda’ evolves into a traitor and coward, it throws Patrick himself into existential doubt. Is he too a coward? How much of himself is in Rupert? Who, really, is he? Forest is in no doubt that the process can be extremely dangerous. The reader doesn’t have to follow her all the way. It could be argued that role-playing is (usually) a safe way of exploring the possibilities of individuals and relationships. Just so long as it doesn’t take over…

A more playful but no less thoughtful exploration of the subject is Jan Mark’s wonderful book “They Do Things Differently There” (1994) in which two bored and lonely teenage girls living in a very ordinary new town called Compton Rosehay, form a friendship by inventing an utterly bizarre alternative neighbourhood called ‘Stalemate’. Local landmarks become ‘Lord Tod’s Corpse Depository’ and ‘The Mermaid Factory:

A more playful but no less thoughtful exploration of the subject is Jan Mark’s wonderful book “They Do Things Differently There” (1994) in which two bored and lonely teenage girls living in a very ordinary new town called Compton Rosehay, form a friendship by inventing an utterly bizarre alternative neighbourhood called ‘Stalemate’. Local landmarks become ‘Lord Tod’s Corpse Depository’ and ‘The Mermaid Factory:“There is a mermaid factory?”

“You know that big iron barn place at the end of Old Compton Street, just opposite the bus stop at the end of the slip road.”

“Where it says O GLEE...?”

“That’s the place.”

“It’s got petrol pumps outside; I think it used to be a garage.”

“You may think so,” said Elaine, “but remember, here in Stalemate what you see is not necessarily what is there. Earth’s fabric hath worn thin. The real Stalemate is all about us, but we only get occasional glimpses of it. You’ll just have to take it on trust. It’s a mermaid factory.”

In this book, the fantasy world the girls create is the basis of the friendship between them. The book’s a celebration of the delights of invention and imagination, and of the joy of finding someone else with the same sense of humour. In the end, though, as the name suggests, you cannot stay in Stalemate. You have to move on.

The most recent book I know which looks at this subject is “The Traitor Game” (2008) by B.R.Collins. Michael and Francis share an imaginary world called Evgard, involved in bitter civil war, with a city called Arcaster. Michael invented it, and it’s been a refuge from the bullying he endured at his last school. Now Francis has been allowed in.

The most recent book I know which looks at this subject is “The Traitor Game” (2008) by B.R.Collins. Michael and Francis share an imaginary world called Evgard, involved in bitter civil war, with a city called Arcaster. Michael invented it, and it’s been a refuge from the bullying he endured at his last school. Now Francis has been allowed in.There was only one other person who knew where Arcaster was; who even knew it existed: Francis. It was as secret, more secret, than a love affair or a drug habit...

And sometimes… when they worked on something together, and ... when both of them were talking about Evgard, arguing, joking, pushing at each other for ideas, Michael felt like he could stretch out his hand and nearly, nearly feel the world of Evgard beyond the real one... He’d catch Francis’s eye when he looked up from his drawing, or hear him say, ‘No, but no, you couldn’t get from Than’s Lynn to Arcaster in two days, it’s winter, you’d have to go the long way round, via Gandet and Hyps,’ and suddenly he’d want to grin like an idiot. It was crazy, they were fifteen, for God’s sake, it wasn’t like they were kids, but here they were inventing a country.

So when Michael believes Francis has betrayed him, his emotions are catastrophic; and the betrayal occurs in Evgard too. This is a dark unflinching book which delves deep into jealousy, cruelty, anger and fear.

All three of these very different books are powerful explorations of friendship and selfhood, and the dark as well as the joyful side of the impulse to create.

Published on March 13, 2014 13:54

March 9, 2014

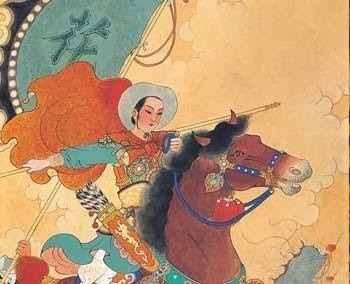

The Ballad of Mulan

I've always liked Arthur Waley's translations of Chinese literature and poetry, and came across this recently in an old edition I found in a second-hand bookshop. The rough ballad style he has chosen seems well suited to the simplicity of the story, to which he adds the note: 'Written in northern China during the domination of the Wei Tartars, Sixth Century AD'. You can compare it with a more recent translation here: http://www.chinapage.com/mulan.html

Click, click, for ever click, click;Mulan sits at the door and weaves.Listen, and you will not hear the shuttle’s sound,But only hear a girl’s sobs and sighs.

“Oh tell me, lady, are you thinking of your love,Oh tell me, lady, are you longing for your dear?”“Oh no, oh no, I am not thinking of my love,Oh no, oh no, I am not longing for my dear.

But last night I read the battle-roll;The Khan has ordered a great levy of men.The battle-roll was written in twelve books,And in each book stood my father’s name.

My father’s sons are not grown men,And of my brothers, none is older than me.Oh let me to the market to buy saddle and horse,And ride with the soldiers to take my father’s place.”

In the eastern market she’s bought a gallant horse,In the western market she’s bought saddle and cloth.In the southern market she’s bought snaffle and reins,In the northern market she’s bought a tall whip.

In the morning she stole from her father’s and mother’s house;At night she was camping by the Yellow River’s side.She could not hear her father and mother calling to her by her name,But only the voice of the Yellow River as its waters swirled through the night.

At dawn they left the River and went on their way;At dusk they came to the Black Water’s side. She could not hear her father and mother calling to her by her name,She could only hear the muffled voices of foreign horsemen riding on the hills of Yen.

A thousand leagues she tramped on the errands of war,Frontiers and hills she crossed like a bird in flight.Through the northern air echoed the watchman’s tap;The wintry light gleamed on coats of mail.

The captain had fought a hundred fights, and died;The warriors in ten years had won their rest.They went home, they saw the Emperor’s face;The Son of Heaven was seated in the Hall of Light.The deeds of the brave were recorded in twelve books;In prizes he gave a hundred thousand cash.

Then spoke the Khan and asked her what she would take.“Oh, Mulan asks not to be madeA Counsellor at the Khan’s court;I only beg for a camel that can marchA thousand leagues a day,To take me back to my home.”

When her father and mother heard that she had come,They went out to the wall and led her back to the house.When her little sister heard that she had come,She went to the door and rouged her face afresh.When her little brother heard that his sister had come,He sharpened his knife and darted like a flashTowards the pigs and sheep.

She opened the gate that leads to the eastern tower,She sat on her bed that stood in the western tower,She cast aside her heavy soldier’s cloak,And wore again her old-time dress.

She stood at the window and bound her cloudy hair;She went to the mirror and fastened her yellow combs.She left the house and met her messmates on the road;Her messmates were startled out of their wits.

They had marched with her for twelve years of warAnd never known that Mulan was a girl.For the male hare sits with its legs tucked in,And the female hare is known for her bleary eye;But set them both scampering side by side,And who so wise could tell you “This is he”?

Translated by Arthur Waley, Chinese Poems, George Allen & Unwin 1936

Picture credits:

Hua Mulan on white horse: image from http://athenaenoctua2013.blogspot.co....

Hua Mulan on bay horse: image from http://www.chinese-swords-guide.com/m...

Published on March 09, 2014 03:16

March 1, 2014

Review: ICEFALL by Gillian Philip

So here is it at last – the fourth and final volume of Gillian Philip’s YA/adult fantasy series ‘REBEL ANGELS’, which began with the electrifying ‘FIREBRAND’ and was followed by ‘BLOODSTONE’ and ‘WOLFSBANE’.

If you haven’t read the series yet, what a treat you have in store as you follow the fortunes – over ben and glen and mountain moor and across centuries – of Seth MacGregor, exiled leader of a clann of the Scottish Sithe, and his struggle against their ruthless queen Kate NicNiven, who aims to rip down the Veil which separates the faerie and mortal worlds, and impose her rule on all.

At the end of ‘WOLFSBANE’ things were looking tough for Seth, his lover Finn, and his son Rory, the ‘Bloodstone’ whom Kate NicNiven needs to fulfil ancient prophecy and tear down the Veil.

Taken together, the four books are a tour-de-force, full of action and excitement, with a huge cast of characters deftly managed. Seth is a tough, laconic, sexy, flawed hero who does his best – and his best isn’t always good enough. Gillian Philip isn’t one of those authors who spares her characters. People die – lots of them. People you like die. Terrible things happen. There’s love and sex and loss and grief and bloodshed. Forget 'Game of Thrones'. This is better.

Taken together, the four books are a tour-de-force, full of action and excitement, with a huge cast of characters deftly managed. Seth is a tough, laconic, sexy, flawed hero who does his best – and his best isn’t always good enough. Gillian Philip isn’t one of those authors who spares her characters. People die – lots of them. People you like die. Terrible things happen. There’s love and sex and loss and grief and bloodshed. Forget 'Game of Thrones'. This is better. One of the things I’ve loved about this series is its boldness. FIREBRAND was set in the tough and bloody sixteenth century – you can find a description of it here. But its successor, BLOODSTONE, jumped straight to the twenty-first, taking advantage of the faerie longevity (definitely not immortality) of the main characters, and resituating them in the no less tough and bloody century we all inhabit today. Exiled faerie characters, good and bad, live on Glasgow sink estates, or have served as mercenaries in Iraq or Afghanistan. (Well, they’re fighters, they have to do something.) But the faerie world calls. Beyond the magical watergates, which may be found anywhere from a wild woodland pool to a flooded basement in a condemned tenement, lies home – no less dangerous but infinitely more beautiful, with its kelpies, its selkies, its feuds and loyalties and treacheries.

ICEFALL introduces Philip’s most sinister creature yet, a mummified child oracle – the Darkfall – which even Kate NicNiven must approach with care. Deep in a cave:-

The breath of the Darkfall was around her. Kate felt it whisper across her skin. Still she waited, until at last a faint light sparked, and grew, and threw shadows that she wouldn’t look at too closely. The child had been dead for years. Centuries. The light was cupped in its hands. Cross-legged in its alcove on the cavern wall, the child lifted its head and gazed at her with eyeless sockets. It opened its mouth. How does it feel?

It's one of those archetypal creations which seem immediately familiar, as though you’ve always known about them. I believed in the Darkfall to the marrow of my bones – and sat back to enjoy the ride. ICEFALL lives up to all the promise of the earlier books. It’s explosive, violent and touching, with an emotionally satisfying ending that gives you, not necessarily everything you've hoped for - but everything you need.

ICEFALL by Gillian Philip will be published by Strident on March 18, 2014

Visit Gillian Philip's website: http://www.gillianphilip.com/

Published on March 01, 2014 03:01

February 21, 2014

Magical Classics: "The King of Ireland's Son" by Padraic Colum

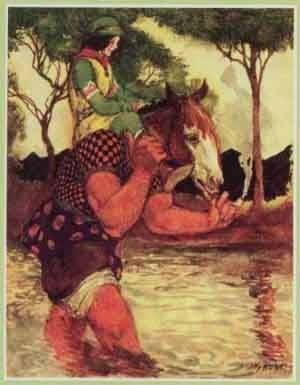

"Then he came from where he was hiding and gave her the swanskin"

"Then he came from where he was hiding and gave her the swanskin" John Patrick Pazdziora on an enchanting Irish classic.

The affair began, as so many do, at a conference. I was just seventeen, and—no, it wasn’t that kind of affair. Good heavens. This was the love of a book.

There were booths aplenty in the Great Hall/gymnasium, but I bulldozed straight to one particular booth—the used book corner, a towering square of collapsible shelves filled with library discards. The bookseller was a charming woman of a certain age, one of those astonishing people who fill the room at a stropping six-foot-five and still manage to seem dainty. She was fond of me, knowing as she did from long experience that I would routinely plonk three months’ worth of allowance on piles of books I’d never heard of and didn’t know I wanted.

“I’ve got a book I think you’d like, hon,” she said. With an easy grace, her huge hand delicately plucked a battered hardcover off the top shelf and plopped it into my hand. It was like so many other easy introductions—half-distracted by the roar of the booths, my mind fretting with the jabber of what to do and where to go and who to see next, a quick glance that saw only the frumpy, mouse-nipped cover, the horrible green and pink striped jacket in the worst possible 1960s way.

“Ah yes,” I said. (What a miserable first impression I must have made.) I turned the book over. “The King of Ireland’s Son. I’ve never heard of this one.”

The bookseller nodded complacently. “It’s very hard to find.”

I looked at the price, swallowed a few times. Ass that I was, trying to measure its value in filthy lucre. “Is it worth it?”

The bookseller widened her eyes and tilted her head, like a duchess who has just found a caterpillar in the soup. “My de-ah! Anything by Padraic Colum is always worth it!”

So it went on the heap like the rest, in the casual way you jot down a number or an email (though this was before email was A Thing) and move on to the next introduction, the next drink, the next book. And it wasn’t till later—how much later I don’t know—that I remembered that ugly green and pink striped book that was so hard to find, that the soft music of the name Padraic Colum crept back in mind, and I sat down to read The King of Ireland’s Son.

Connal was the name of the King who ruled over Ireland at that time. He had three sons, and, as the fir trees grow, some crooked and some straight, one of them grew up so wild that in the end the King and the King’s Councillor had to let him have his own way in everything. This youth was the King’s eldest son and his mother had died before she could be a guide to him.

I honestly don’t remember reading it for the first time. I think, perhaps, there’s just a flicker of memory of my great-grandmother’s white armchair and the lights on of a winter’s evening as I sat, reading about the King of the Land of Mist and Fedelma the Enchanter’s Daughter. I think. I read a lot of books in that chair, so this memory might be confused with another, or several others. And try as I might now, I can’t unstitch the rhythms and richness and sound, the great rolling mouthy feel of the book, from the memories of my childhood and my adolescence, from my own faltering steps and proud determination at being a Real Writer. The memory of it has seeped in through all the cracks and gaps and crevices. Remembering when I first read it is like remembering when I first learned how to slot one word after another and talk. It’s that kind of book.

Now after the King and the King’s Councillor left him to his own way the youth I’m telling you about did nothing but ride and hunt all day. Well, one morning he rode abroad— His hound at his heel,

His hawk at his wrist,

A brave steed to carry him whither he list,

And the blue sky over him,and he rode until he came to a turn in the road. There he saw an old gray man seated on a heap of stones playing a game of cards with himself. Now he would say “That’s my good right,” and then he would say “Play and beat that, my gallant left.” The King of Ireland’s Son sat on his horse to watch the strange old man, and as he watched he sang a song to himself—

Whenever it was, when I first read The King of Ireland’s Son, I’d never heard of the Celtic Twilight or Padraic Colum. I’d yet to have my undergraduate romance with the poetry of Yeats. I’d fallen under the spell of Narnia and The Lord of the Rings, but not Harry Potter. I’d read Little Dorrit and Ivanhoe, but not Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn or The Restaurant at the End of the Universe. I was at an impressionable age, you might say, and certainly I was hungry for a good story, for magical sounding words. And if this strange little mouse-nipped book had simply been another cracking discovery, like The Twilight of Magic, it would have been good enough.

But it’s one of those books that explodes in your hands and in your mind and in your heart, and gets all over the way you think about story and the way you use words—one of those books that twists round inside you and takes you in ways and places you’ve never thought of. Reading it was like seeing a magician for the first time, without knowing anything about sleight of hand or picking a card, any card, so you still think it’s all in the word and the mind and the eye, and would do even if the magician was holding a sheet over his face and saying he’d disappeared. Except it’s a really good magician, one of those sleight-of-hand lads that make professional illusionists look like hacks, one of those who, even long after you’ve learned all the tricks and knots and secret chambers themselves, when you see them perform you—you just can’t help but wonder…You’re seeing magic for the first time, before your very eyes. And it’s all told in the most wonderful, magical, enchanting words. They’re words written for speech, these words, for resonance and richness and music. They’ll change your life, these words, or at the very least they’ll change the way you think about the stories that you tell, and listen to.

It’s that kind of book.

I put the fastenings on my boat

For a year and for a day,

And I went to where the rowans grow,

And where the moorhens lay;And I went over the steppingstones

And dipped my feet in the ford,

And came at last to the Swineherd’s house—

The Youth without a Sword.A swallow sang upon his porch,

“Glu-ee, glu-ee, glu-ee,”

“The wonder of all wandering,

“The wonder of the sea”;

A swallow soon to leave ground sang

“Glu-ee, glu-ee, glu-ee.”

“Prince,” said the old fellow looking up at him, “if you can play a game as well as you can sing a song, I’d like if you would sit down beside me.”“I can play any game,” said the King of Ireland’s Son. He fastened his horse to the branch of a tree and sat down on the heap of stones beside the old man.“What shall we play for?” said the gray old fellow.“Whatever you like,” said the King of Ireland’s Son.“If I win you must give me anything I ask, and if you win I shall give you anything you ask. Will you agree to that?”

Listen! It’s as if Colum has taken every fairy tale and folk story you’ve ever heard or thought of, and a few you haven’t, and he’s taken all the best bits of them, the most magical, and woven them together into a seamless, shining whole. Tale after tale flows over you, and when you expect one story to stop, you find it’s given rise to another, including the best telling of “The Three Ravens” that I’ve ever heard. There’s tricksters and devils and storytellers, bold knights who fall in disgrace and daring maidens who rescue them. There’s three daughters, two of them bad and one of them good, and there’s a battle between the animals and the birds, and the King of Cats comes to Ireland. There’s Gillie of the Goatskin who’s gone in search of the Unique Tale and winds up confronting the Churl of the Townland of Mischance, and there’s Rory the Fox who steals the Crystal Egg and its power of wishing. There’s the silent , Sheen, who follows the Hunter King’s soul into the Quaking Bog, there’s the Pooka—who’s a timid little fellow, as the Little Red Hen knows—and there’s the search for the Swan of Endless Tales.

And it’s all one story! And that’s just the beginning, with more to come besides. Adventures, quests, enchantments, deceptions, impossible tasks, revenge, giants, monsters, chases, escapes, true love—heck, I can’t even describe it without sounding like Peter Falk.

Go read it. Go read it right now. It’s that kind of book, too.

“A goose to hatch the Crystal Egg after an Eagle had half-hatched it! Aye, aye, to be sure, that’s right,” said the Old Woman of Beare. “And now you must go find out what happened to it. Go now, and when you come back I will give you your name.”

John Patrick Pazdziora (PhD, St Andrews) is a research associate at the Institute for Theology, Imagination and the Arts, St Mary’s College, St Andrews. His primary work is on Scottish literature in the nineteenth century, and the adaptation of folklore and the ballad tradition in children’s literature; he has particular interest in George MacDonald, James Hogg, and Andrew Lang. He has also published on more modern authors such as James Thurber, Claire Dean, and J. K. Rowling. With Christopher MacLachlan and Ginger Stelle, he co-edited Re-Thinking George MacDonald: Contexts and Contemporaries (ASLS 2013), and edited New Fairy Tales: Essays and Stories (Unlocking, 2013) with Defne Çizakça. He is also the general editor of Unsettling Wonder (www.unsettlingwonder.com), an imprint of Papaveria Press.

Picture credits: "The King of Ireland's Son": all illustrations by Willy Pogany via Sacred Texts: you can read the book online here.

Published on February 21, 2014 05:11