Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 27

September 14, 2013

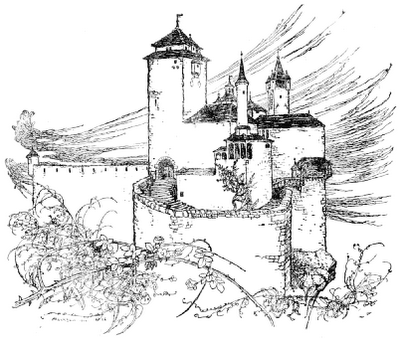

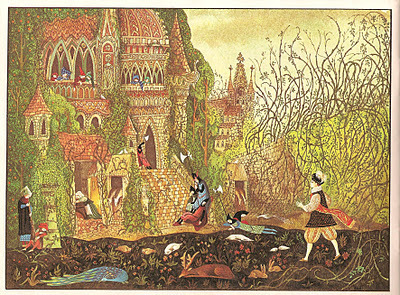

Briar Rose - or 'Time Be Stopped'

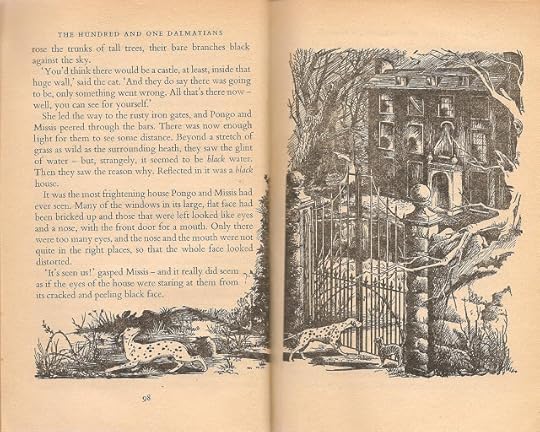

Schooldays. I’m about eight years old, I have my brown school reader in my hand, and I’m about to knock on the headmistress’s door. Everyone in the school has to go and read to her once a week - a solemn ceremony and not a bad one either: there’s something special about leaving the classroom while lessons are happening and making this solo pilgrimage across the quiet school hall. The door swings open and I see her room drenched in sunlight, her window opening on to a bright rose garden beyond, a garden perhaps for the teachers only, as I don’t remember ever setting foot there - a secret garden. I stand beside her desk and read aloud, and the story is Briar Rose. And somehow the feeling of her office - this sunlit, secluded, shut-away space - weaves into the story I’m reading, so that while the tall hedge of briars springs up around the castle, and everyone, even the doves on the roof and the flies on the wall, drop into their century of sleep, I feel as though it’s all happening right now, and the sleepy afternoon enfolds the school for a perfect enchanted moment, now and forever.

No one in the last Fairytale Reflections series chose Briar Rose - the Sleeping Beauty - as one of their favourites. It’s a tale which has become almost notorious as presenting an image of female passivity, the worst possible role model for a child to grow up with: a heroine who does nothing, initiates nothing, whose claim to fame is to sleep for a hundred years and be woken by the kiss of a prince she hasn’t even chosen (and that’s the mildest version): an object rather than a subject. It’s one of the most difficult fairystories to retell and still stick to the original. Disney fudged the issue of the hundred years sleep by doing away with it altogether and introducing a fire-breathing dragon instead. Robin McKinley’s wonderful ‘Spindle’s End’ also does away with the passive heroine, and achieves its success by departing from the fairytale in many ways. Her themes are friendship and self-discovery, and her heroine Rosie escapes the enspelled sleep which envelops the castle, and rides to defeat the sorceress who has caused it. Only Sheri S Tepper’s ‘Beauty’ really engages with the hundred-years sleep and makes a magnificent and intriguing mystery out of it. (And I am reminded that there are two wonderful books, Jane Yolen's 'Briar Rose' and Adele Geras's 'Watching the Roses', which use the fairytale as the basis for realistic novels exploring, in Yolen's case, a Holocaust survival story and in Geras's, a rape.)

What matters to me about the fairytale though, isn’t the heroine, whether you call her Briar Rose or Aurora or Rosie, it’s the mythos - the idea of time coming to a standstill for a hundred years. Not all stories are about people, even if they include people; not all stories are hero/heroine-centered. They can be about ideas, feelings, wonders - the white blink of lightning as the sky cracks and the eye of God looks through. For me this story is about the shiver you feel - which any child feels - when the storyteller says:

“The horses in the stable, the doves on the roof, the dogs in the kennel and the flies on the wall, all fell fast asleep. Even the fire ceased to burn. And a hedge of thorns sprang up around the palace and grew higher and higher, so that it was lost to sight.”

When you’re a child, time seems endless anyway. So long to wait till your birthday! So long to wait till Christmas! The holidays stretch for ever, and even a single day at school, six short hours or so, can be an eternity of happiness or unhappiness or boredom. And a hundred of anything is an enormous number. “What would you do if you had a hundred pounds?” we used to ask each other as children. To sleep for a hundred years! The story is a meditation on Time.

“Footfalls echo in the memory,” (says T S Eliot)

“Down the passage which we did not take,

Towards the door we never opened

Into the rose garden.”

Four Quartets is a poem full of the imagery of houses which rise and fall and vanish, of rose gardens and fallen petals and lost children. As it, too, is a profound meditation upon Time, am I wrong to suspect that the story of Briar Rose, the Sleeping Beauty, was somewhere in the poet’s mind as he wrote?

“Ash on an old man’s sleeve

Is all the ash the burnt roses leave.

Dust in the air suspended

Marks the place where a story ended.

Dust inbreathed was a house-

The wall, the wainscot and the mouse.”

What is Time? the poem asks. A cycle of recurring seasons? A river which sweeps us away? A train on a set of linear tracks, the present moment drumming ever onwards, leaving everything we have known unreachably behind? Or can Time somehow curl around us like an enclosed secret garden in which the essence of everything we’ve loved is still real, compressed like a bowl of rose leaves, immanent, half glimpsed?

In T.F. Powys’s little-known masterpiece ‘Mr Weston’s Good Wine’, God - in the shape of wine-salesman Mr Weston, accompanied by his assistant Michael, arrives at the village of Folly Down one bleak November day in a small Ford van. Mr Weston is here to offer the villagers his choice of wines, from the light wine of love to the dark wine of death. It’s a marvellous, tender story, both comic and sad: but the bit that remains in my memory is this passage near the middle of the book, when something very odd happens in Angel Inn, the village pub:

…Mr Thomas Bunce happened to look at the grandfather clock. He did so because the unnatural silence that came over the company - an angel is said to be walking near when such a silence occurs - had disclosed the astonishing fact that the clock was not ticking.

Mr Bunce was sure that the clock was wound. He knew that the heavy pendulum was in proper order, though no one nodded to it now; and yet the clock had stopped.

…No policeman, supposing that one of them had happened to call to see that the right and lawful hours were kept at Folly Down inn, could ever have found fault with that timepiece. The clock was truthful; it was even more honourable than that; it was always two minutes in advance of its prouder relation, that was set high above mankind, in the Shelton church tower.

Mr Bunce stared hard at the clock. He wished to be sure.

All was silent again.

“Time be stopped,” exclaimed Mr Bunce excitedly.

“And eternity have begun,” said Mr Grunter.

Of course the story of Briar Rose continues, with the prince’s arrival and the blossoming of the thorns into roses, and the kiss and the awakening, because time does move and so must narratives. But I don’t think that’s what the story is about. I’m sure the reason the story (otherwise so slight) has remained in existence for so long, is all to do with that hiatus in the middle, in which nothing happens except one long moment. Perhaps it celebrates the way life happens in the gaps between the lines, the space between the words, the silence in the imaginary rose garden. Perhaps it moves us in an almost Taoist sense to look, really look at the flies on the wall, the doves on the roof, the arrested gesture of the cook’s hand as she slaps the serving boy - and say to ourselves,

“This - this is life.”

© Katherine Langrish February 2012

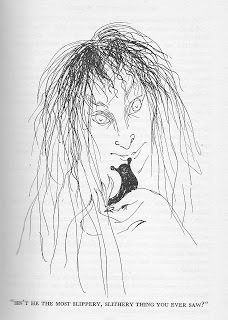

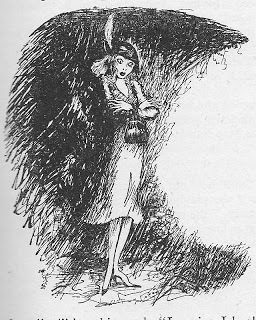

Picture credits:

Arthur Rackham, Sleeping Beauty. All the others are by Errol le Cain from 'Thorn Rose'

Published on September 14, 2013 02:45

September 7, 2013

Good Witches

In this third post about witches, I’m considering some children’s books in which the characters are recognisably witches, but good rather than evil.

In this third post about witches, I’m considering some children’s books in which the characters are recognisably witches, but good rather than evil. All of these examples are modern. I’m not sure I know of any good witches in older fiction except for Glinda in ‘The Wizard of Oz’,and incidentally, I don’t know how I forgot to mention the Wicked Witch of the West, in my first witchy post, as a fine example of an American witch – and her recent reinvention by Gregory Maguire in ‘Wicked’ exemplifies the changes in attitude which have been taking place over the decades, changes which have to be set down to the feminist movement. The very title of Maguire’s book is a gauntlet thrown down. If anyone is wicked in ‘Wicked’, it’s not the witch. And it’s a lot more difficult these days than it used to be, to think powerful female = witch = evil.

Let’s start with the great Terry Pratchett. The very first book of his I ever read was ‘Wyrd Sisters’. I’d been put off the Discworld novels by their covers, which looked too hysterical for me. But I picked up ‘Wyrd Sisters’ in the library one day and read the opening page:

The wind howled. Lightning stabbed at the earth erratically, like an inefficient assassin... …In the middle of this elemental storm a fire gleamed among the dripping furze bushes, like the madness in a weasel’s eye. It illuminated three hunched figures. As the cauldron bubbled an eldritch voice shrieked: “When shall we three meet again?” There was a pause. Finally another voice said, in far more ordinary tones: “Well, I can do next Tuesday.”

On this comic anticlimax we meet Granny Weatherwax, Nanny Ogg and Magrat ('Margaret', only her mother couldn’t spell). And what these three witches do is what women down the years have always done. They help bring babies into the world, they do their best to cure the sick, they lay out the dead, and they dispense commonsense advice with a bit of magical flimmery-flammery to help it along. On top of that, Granny Weatherwax in particular is skilled in what she calls ‘headology’ – a fine-tuned sympathy with the minds and beings of others. In ‘Wyrd Sisters’ the three witches prevent soldiers from killing a baby on the moor at night, and on discovering a crown in the bundle of wrappings, realise they have to hide the child. And the crown? Can it be hidden too?

“Oh, that’s easy,” said Magrat. “I mean, you just hide it under a stone or something…” “It ain’t,” said Granny. “The reason being, the country’s full of babies and they all look the same, but I don’t reckon there’s many crowns. They have this way of being found, anyway. They kind of call out to people’s minds. If you bunged it under a stone up here, in a week’s time it’d get itself discovered by accident. You mark my words.” “It’s true, is that,” said Nanny Ogg earnestly. “How many times have you thrown a magic ring into the deepest depths of the ocean and then, when you get home and have a nice bit of turbot for your tea, there it is?” They considered this in silence. “Never,” said Granny irritably.

The Discworld novels are written for adults, but are YA in their appeal, and Terry Pratchett has also written several children’s books set in the same world, featuring the young apprentice witch Tiffany Aching – a girl of great grit, determination and courage. The first in the series is ‘The Wee Free Men’, and begins with yet another witch (Miss Perspicacia Tick) sitting under a hedge in the rain, making a device to ‘explore the universe’:

The exploring of the universe was being done with a couple of twigs tied together with string, a stone with a hole in it, an egg, one of Miss Tick’s stockings which also had a hole in it, a pin, a piece of paper, and a tiny stub of pencil. Unlike wizards, witches learn to make do with very little.

Terry Pratchett, you feel, actually likes women. He seems comfortable around them in a way the male authors of my last week’s post – C.S. Lewis, T.H. White and even Alan Garner – do not.

In Philip Pullman’s ‘The Golden Compass’, the first book of ‘His Dark Materials’, we meet a race of witches of a very different type. They are far wilder and more romantic than Terry Pratchett’s – a reversion to the witch queen type, in fact, but as ever-youthful as the fairies and as warlike as the Amazons. They come to the rescue of Lyra and her friends during the attack on the Bolvangar experiment station, shooting their arrows with deadly effect:

“Witches!” said Pantalaimon. And so they were: ragged elegant black shapes sweeping past high above, with a hiss and swish of air through the needles of the cloud-pine branches they rode on. As Lyra watched, one swooped low and loosed an arrow: another man fell.

A few pages later, Lyra meets one of them: clan queen Serafina Pekkala:

She was young – younger than Mrs Coulter; and fair, with bright green eyes; and clad like all the witches in strips of black silk, but wearing no furs, hoods of mittens. She seemed to feel no cold at all. Around her brow was a simple chain of little red flowers. She sat on her cloud-pine branch as if it were a steed… Lyra could see why Farder Coram loved her, and why it was breaking his heart… He was growing old: he was an old broken man, and she would be young for generations.

They aren’t central characters, and you could argue that Mrs Coulter wears the pointed hat in this story, but the courageous, nearly immortal witches, with their necessarily brief liaisons with human men and women, lend an exotic touch of wildness and tragedy to Pullman’s world.

A witch who didn't make it into the last couple of posts is the Russian BabaYaga, with her hut on chicken legs. She's pretty scary but ambiguous - she can actually be helpful if propitiated in the right way. Susan Price’s Carnegie Medal winning ‘The Ghost Drum’ is drawn from the Russian tradition. With its sequels ‘Ghost Dance’ and ‘Ghost Song’ (now all available as e-books) it is set in “a far-away Czardom, where the winter is a cold half-year of darkness.”

Here we meet the witch-girl Chingis, daughter of a slave, rescued and raised to be a Woman of Power by a shaman woman, who exchanges the child for a snow baby and takes her away.

Out in the night, in the snow, stood another house. It stood on two giant chicken-legs. It was a little house – a hut – but it had its double windows and its double doors to keep in the warmth of the stove, and it had good thick walls and a roof of pine shingles. The witch came running over the snow, and the house bent its chicken-legs and lowered its door to the ground… …Then the legs took a few quick, jerky steps, sprang, and began to run. Away over the snow ran the little house… Its windows were suddenly lit by a glow of candlelight. The hopping candlelight could be seen for a long time, shining warmly in the cold, glimmering twilight, but then the light was so distant and small that it seemed to go out. All that was left of the little house was its footprints.

Raised by the witch-shaman, Chingis becomes her successor, and eventually goes to rescue young Safa, the son of the mad Czar, whose father has kept him shut up in a single room for his entire life.

Every moment, day and night, waking and dreaming, his spirit cried; and circled and circled the dome room, seeking a way out. And Chingis heard. She heard it first as she slept; a strange and eerily disturbing crying. Stepping from her body, her spirit grasped the thread of the cry and flew on it, like a kite on a line, to the Imperial Palace, to the highest tower, to the enamelled dome.

Armed with her wits, her spells, and her grandmother’s proverb: “Whenever you poke your nose out of doors, pack courage and leave fear at home,” Chingis sets off on a mission that will take her all the way to Iron Wood and the Ghost World. This is one of those books I just wish I had written myself, although I know I never could have done it half so well. It inverts the terror and evil of Baba Yaga, reinventing her as a shaman with powers allied to nature, stronger and more merciful than the cruelties of Czars. It’s beautiful. Please read it!

I have written a witch of my own – Astrid, the girl with ‘troll blood’ in the book of that name, 'Troll Blood', the third part of my Viking trilogy 'West of the Moon'. Is she really a witch, though? That’s what the viking sailors call her, because they fear and dislike her, and it’s true she practises seidr – the old northern magic (pronounced roughly saythoor). But Astrid – haughty, proud, thin-skinned, damaged and vulnerable – hasn’t had much of a chance in life, and uses her powers to command what respect and fear she can, since she doesn’t expect love. Whether or not any of her spells really work is left open. I don’t know myself. But I do know that I have a lot of sympathy for difficult, prickly, deceitful Astrid, and I hope the reader will too.

Lastly, what about the Harry Potter books? And why on earth didn’t I begin with them?

Well, to my mind, the Harry Potter books are hardly about witches at all. They’re about school-children masquerading as witches. Yes – they go to Hogwarts, which is billed as a school for witches and wizards. Yes, they learn spells. Yes, there are plenty of the trappings of witchery about: pointed black hats, robes, wands (wands? witches don't need wands, those are for wizards), cauldrons, etc. And yes, Harry and his friends are pitted against a Dark Lord of impeccable credentials, Voldemort, who undoubtedly goes to the same club as Sauron and Lucifer. But does anyone really believe Hermione Granger is a witch? Top of the class in spells she may be, but seriously? Are Harry and Ron really wizards? Try mentally lining them up with Gandalf, Ged, and even Dumbledore, and see what I mean.

Wizards may go to school, wizards may study things: wizards are expected to be forever poring over old curling scrolls while the stuffed crocodile dangles overhead. But as soon as you make witchcraft into something taught in a classroom, for me the magic runs right out of it like water from a bath. I do like the first three Harry Potter books (with reservations about the rest concerning editing, mainly) – I love the energy and fun and sheer inventiveness of Rowling’s writing. But, along with other witch school series such as Jill Murphy’s ‘The Worst Witch’ and some of Diana Wynne Jones’ Chrestomanci titles, the witchery seems to me to be there to lend colour and flavour to what is basically an old-fashioned school story. And none the worse for that. However, and it’s an important point, in these modern books the traditional image of the witch has lost its power. Dress up Hermione in robes and black hat as much as you like, she’ll always look more like a college girl on graduation day than a minion of Satan.

When I started these posts, I wasn’t sure where they would lead me. But it seems to me that over the past seventy years, the image of the witch in children’s fiction has changed considerably to have reached the point where a set of books about a whole school full of children training to be witches fighting against evil can be received by the mainstream with perfect aplomb. And I end on this thought – those earnest people who do worry about the Harry Potter books and the treatment of witches in children’s fiction, need to learn to look past the shadow to the substance.

© Katherine Langrish September 2010

Published on September 07, 2013 06:49

August 31, 2013

Witches: Queens and Crones and Little Girls

The witches from children’s fiction who appeared in my last post were all wicked. But their authors wrote about them with humour, and a relish for the sheer range of social possibilities open to a character possessing magical powers and zero scruples. Miss Smith, Sylvia Daisy Pouncer and Madam Mim are most unlovable, but we can thoroughly enjoy their subversive wickedness in complete assurance that all will be well in the end. Theirs is the evergreen appeal of seeing someone behave appallingly badly in ways you secretly long to do yourself, but haven't the nerve.

In this post, though, I’m thinking about some much darker witches, whose authors take them – and expect us to take them – very seriously. All the examples in this post are from books I've been reading and rereading for years, and deeply admire. These witches are quite diverse, but two things are constant: they are all bad characters, and we are not expected to feel any secret sympathy for them.

And you can forget about the old crone with nutcracker nose and chin, wearing a pointed hat and riding on a broomstick. Instead, we meet a range of variants on the ‘witch queen’ theme, plus a scatter of adherents to black magic including a scholar, a postmistress and a little girl.

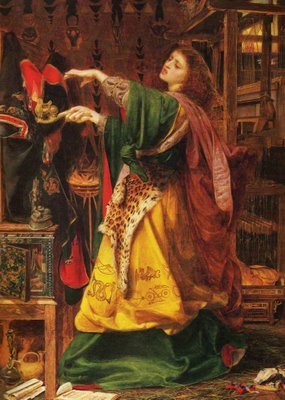

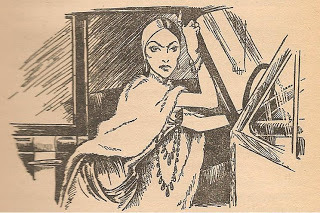

The witch queen is a stereotype as old as the hills, coming down to us from many an ancient goddess (Ishtar, Astarte, Diana Queen of the Night) whose worship was suppressed. This picture of Medea by the Pre-Raphaelite Frederick Sandys suggests the type. Patriarchal monotheism doesn’t go in for powerful females. They’re difficult to keep out, as the cult of the Madonna shows – but the Madonna personifies male-approved feminine qualities of tenderness, mercy, beauty and maternal love. Patriarchal systems save the tougher qualities of justice, wrath, vengeance etc, for the male deity. The Madonna never said ‘Vengeance is mine’. But Diana had Acteon torn to pieces by his own hounds.

Descended from disapproved goddesses, it’s usual for fictional witch queens to be beautiful, sexual women of great power, selfishness and cruelty. Check out T.H. White’s Morgause, Queen of Orkney, busy – on the first occasion we meet her – boiling a cat alive, and all for nothing: nearing the end of the spell, Morgause can’t be bothered to continue. She’s the mother from hell. Adored by her sons, she alternately neglects, torments and smothers them. She uses everyone she meets and is the ruin of most of them. The title of the book in which she appears, "The Queen of Air and Darkness", comes from the well known poem by A.E. Housman, worth quoting in full:

Her strong enchantments failing,

Her towers of fear in wreck,

Her limbecks dried of poisons

And the knife at her neck

The Queen of air and darkness

Begins to shrill and cry,

'O young man, O my slayer.

Tomorrow you shall die.'

O Queen of air and darkness,

I think 'tis truth you say,

And I shall die tomorrow,

But you shall die today.

It's an extraordinary conjuration of fear and violence, and antagonism not only between the sexes but possibly between the generations. There is no sympathy, no possibility of mercy towards this Queen. She is to be destroyed as one might kill a snake.

T.H. White was a man tormented by his own sexuality and suppressed sado-masochistic tendencies. He had a terrible relationship with his own mother, and once wrote to his friend David Garnett (asking him to call on her), “She is a witch, so look out, if you go.” In Elisabeth Brewer’s critical work, ‘T.H. White’s The Once and Future King’, 1993, White is quoted as describing Morgause thus:

She should have all the frightful power and mystery of women. Yet she should be quite shallow, cruel, selfish…One important thing is her Celtic blood. Let her be the worst West-of-Ireland type: the one with cunning bred in the bone. Let her be mealy-mouthed: butter would not melt in it. Yet also she must be full of blood and power.

Blood and power (and racism): White is clearly very frightened of this woman, who both fascinates and repels him. He didn’t find his Morgause in Malory. Malory’s Queen Morgawse isn’t even an enchantress like her half-sister Morgan Le Fay. ‘Le Morte D’Arthur’ presents her as a great lady whose sins are adulterous rather than sorcerous. No: White created his Morgause out of his own fears and loathings.

Whether or not ‘The Once and Future King’ is really a book for children – I first read it as a young teen – the Narnia books certainly are, and contain two excellent examples of the Witch Queen: Jadis of ‘The Magician’s Nephew’, who reappears as the White Witch in ‘The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe’; and the Green Witch of ‘The Silver Chair’, who shares many characteristics with fairy queens of the Unseelie Court. (But let’s stick to witches for now.) Jadis is proud, cruel, ruthless and ambitious, and as the White Witch and usurper of Narnia, actually sacrifices Aslan the Lion. Lewis traces her descent from Lilith and – in ‘The Magician’s Nephew’ – she is seen stealing the apples of Life in a scene echoing the transgression of Eve. The comedy of the chapter in which she riots through London, balancing on top of a hansom cab as if it were a chariot, does suggest some wicked delight on the part of the author – perhaps mostly because of Uncle Andrew’s complete discomfiture. Lewis is making a point about different types of evil: where Uncle Andrew is slimy and small-minded, Jadis has beauty, style and magnificence: but we are not to approve of either of them. The Green Lady, by contrast, is softly spoken, charming, ‘feminine’ – and sly, dangerous and deceitful. Women, Lewis clearly feels, should be neither domineering nor manipulative…

Celtic legends have provided the attributes of many a witch-queen of modern times. The foremost is Alan Garner’s ‘the Morrigan’, a name borrowed from Irish legend and originally probably that of a war goddess. The name is variously translated as Great Queen or Phantom Queen. At any rate, in Garner’s ‘The Weirdstone of Brisingamen’ and ‘The Moon of Gomrath’, she appears as the death or crone aspect of the triple Moon Goddess: the roles of maiden and mother being taken respectively by the young heroine Susan, and the Lady of the Lake Angharad Goldenhand. Dividing up the feminine in this way allows the author to approve maiden and mother (on the time-honoured Madonna pattern) while disapproving the crone. The Morrigan isn’t all that old, but she seems so to Susan, and is physically unattractive:

She looked about forty-five years old, was powerfully built (“fat” was the word Susan used to describe her), and her head rested firmly upon her shoulders without appearing to have much of a neck at all. Two deep lines ran from wither side of her nose to the corners of her wide, thin-lipped mouth, and her eyes were rather too small for her broad head. Strangely enough her legs were long and spindly, so that in outline she resembled a well-fed sparrow, but again that was Susan’s description… Her eyes rolled upwards and the lids came down till only an unpleasant white line showed; and then she began to whisper to herself.

('But again that was Susan's description' - this is oddly arch, for Garner. It's as if he's disassociating himself from Susan's opinion: the subtext is that you might not want to believe her - but why? Because Susan might be jealous? Because you can't ever wholly trust what one female says about another?)

Anyway. Frightening, powerful, ruthless, the Morrigan wastes no time in trying to conjure the children into her car so that she can take the ‘Bridestone’ from Susan. Later, in the second book, ‘The Moon of Gomrath’, the Morrigan is revealed in her true strength. In a chapter which still makes my spine prickle after years of re-reading, Susan faces the Morrigan outside the ruined house which is only ‘there’ in the moonlight:

Now Susan felt the true weight of her danger, when she looked into eyes that were as luminous as an owl’s with blackness swirling in their depths. The moon charged the Morrigan with such power that when she lifted her hand even the voice of the stream died, and the air was sweet with fear.

Susan and the Morrigan vie with one another, black and silver lances of power jetting from their mirror-opposite bracelets, and when at last Susan wins by blowing the horn of Angharad Goldenhand, it’s an all-female victory by which the world is unsettlingly changed: Susan’s brother Colin hears a sound ‘so beautiful he never found rest again’, and ‘the Old Magic was free for ever, and the moon was new.’ Is this a good thing or a bad thing? Garner’s answer appears to be that it’s an unavoidable natural force, and each individual will have to come to his or her own terms with it.

Powerful, magical, beautiful as the books are, Garner is forced into an awkward distinction between the Black Magic supposedly practised by the Morrigan, and the Old Magic of the elemental Wild Hunt and the moon maidens Susan and Angharad. It seems a little illogical to brand the Old Moon as evil while the New and Full Moons are good… I’m not sure quite where the Morrigan’s evil really resides, and I think LeGuin would say that we need to accept the darkness as well as the light. (In Garner's recent sequel, 'Boneland' he take a fresh look at the Morrigan.) But the books are brilliant, and the Morrigan is another unforgettable witch-queen.

Moving on from the Celtic goddesses, we come to some witches of more mundane appearance. First, Emma Cobley of Elizabeth Goudge’s ‘Linnets and Valerians’. Goudge was a spiritual, religious writer: also an intelligent, questioning one, and there are some moving passages in her adult books about the trials of mental illness. She was conscious of goodness as a great force, and of evil as a force almost as strong. In this book, Emma Cobley is an elderly postmistress of humble background; as a young, vivid girl she was in love with Hugo Valerian, the squire; and when he married the doctor’s daughter Alicia, in jealous hatred she cast spells on him and his wife and child. Spells for ‘binding the tongue’, for causing loss of memory, for ‘a coolness to come between a man and a woman’: little images carved of mandrake root with pins piercing the tongue or heart. Emma keeps the village shop, full of tempting sweets like the witch’s house in Hansel and Gretel, and owns a black cat which can change size. The wickedness in the book is an expression of the capacity of the human soul to cling to destructive passions.

As is the acquisitiveness of the next witch: Dr Melanie D. Powers, of Lucy Boston’s ‘An Enemy at Green Knowe’. (For those who don’t know the Green Knowe series, it’s a set of gentle but eerie ghost stories set in Lucy Boston’s own wonderful 11th century manor house, and I can’t praise it too highly.) The grandson of the house, Tolly, and his friend Ping, pit themselves against his grandmother’s new neighbour, a prying, malicious woman, a Cambridge don and scholar of the occult, who has – we slowly realise – struck a Faustian bargain with the devil. She has got wind of an ancient occult manuscript to be found in the manor house, and will stop at nothing to get hold of it. Miss Powers (who has an unaccountable dislike of passing in front of a mirror) invites herself to tea at the manor, and makes ultra-sweet conversation with such ominous lines as:

As is the acquisitiveness of the next witch: Dr Melanie D. Powers, of Lucy Boston’s ‘An Enemy at Green Knowe’. (For those who don’t know the Green Knowe series, it’s a set of gentle but eerie ghost stories set in Lucy Boston’s own wonderful 11th century manor house, and I can’t praise it too highly.) The grandson of the house, Tolly, and his friend Ping, pit themselves against his grandmother’s new neighbour, a prying, malicious woman, a Cambridge don and scholar of the occult, who has – we slowly realise – struck a Faustian bargain with the devil. She has got wind of an ancient occult manuscript to be found in the manor house, and will stop at nothing to get hold of it. Miss Powers (who has an unaccountable dislike of passing in front of a mirror) invites herself to tea at the manor, and makes ultra-sweet conversation with such ominous lines as:

“One can sense that yours is a very happy family. Happy families are not so frequent as people make out. And unfortunately they are easily broken up. Very easily.”

She refuses to take a small cake:

“Grown-ups do better without extra luxuries like that. It is enough for me to look at them.”

In fact, it seemed to Tolly that she could not take her eyes off them… About half an hour later when tea was over… Mrs Oldknowe offered to lead the way upstairs to see the rest of the house. Miss Powers was standing with her back to the table, her hands clasped behind her, lingering to look at the picture over the fireplace, when Tolly… saw one of the little French cakes move, jerkily, as if a mouse were pulling it. Then it slid over the edge of the plate… and into the twiddling fingers held ready for it behind Miss Powers’ back.

And this tells us everything we need to know about Miss Powers. Petty, deceitful, covetous, full of malice, she is a truly evil person. The damage she causes is real: the boys’ beloved grandmother, Mrs Oldknowe, is nearly defeated by her; and the triumph of good over evil – the grand climax when, in the midst of a total eclipse of the sun, her demon is finally driven out of her – is only precariously achieved.

Pettiness and selfish ambition are qualities lavishly displayed by Gwendolen Chant, of Diana Wynne Jones’ ‘Charmed Life’. Wynne Jones writes even-handedly about good and evil witches, warlocks and wizards, but Gwendolen is one of the worst of the bunch. What Wynne Jones despises above all is exploitation of others and betrayal of trust. Gwendolen, a pretty girl with blue eyes and golden hair, exploits and betrays her younger brother Cat to the extent of actually causing his death on several occasions – since Cat, as she knows and he doesn’t, is a nine-lifed enchanter. Gwendolen uses his extra lives to enhance her own powers of witchcraft. Like some of the witches I wrote about last week, Gwendolen has no problem with the sort of anti-social behaviour which can be entertaining to behold – as Cat says, ‘I quite liked some of the things she did’ – but we are left in no doubt that she has gone too far when she conjures up what we later discover to be the apparitions of Cat’s lost lives:

The first was like a baby that was too small to walk – except that it was walking, with its big head wobbling. The next was a cripple, so twisted and cramped upon itself that it could barely hobble. The third was… pitiful, wrinkled and draggled. The last had its white skin barred with blue stripes. All were weak and white and horrible.

So there’s the range of seriously presented evil witches in children’s fiction, from glamorous witch queens to extremely nasty little girls. All of the witch queens I could call to mind have been created by men; women writers have created more domestic and less obviously dramatic characters. I leave you to decide what the different examples say, individually, about the various authors’ attitudes to women. Next post will be about the sympathetic presentation of witches – children’s books where witches are given an altogether more positive aspect.

© Katherine Langrish 27 August 2010

In this post, though, I’m thinking about some much darker witches, whose authors take them – and expect us to take them – very seriously. All the examples in this post are from books I've been reading and rereading for years, and deeply admire. These witches are quite diverse, but two things are constant: they are all bad characters, and we are not expected to feel any secret sympathy for them.

And you can forget about the old crone with nutcracker nose and chin, wearing a pointed hat and riding on a broomstick. Instead, we meet a range of variants on the ‘witch queen’ theme, plus a scatter of adherents to black magic including a scholar, a postmistress and a little girl.

The witch queen is a stereotype as old as the hills, coming down to us from many an ancient goddess (Ishtar, Astarte, Diana Queen of the Night) whose worship was suppressed. This picture of Medea by the Pre-Raphaelite Frederick Sandys suggests the type. Patriarchal monotheism doesn’t go in for powerful females. They’re difficult to keep out, as the cult of the Madonna shows – but the Madonna personifies male-approved feminine qualities of tenderness, mercy, beauty and maternal love. Patriarchal systems save the tougher qualities of justice, wrath, vengeance etc, for the male deity. The Madonna never said ‘Vengeance is mine’. But Diana had Acteon torn to pieces by his own hounds.

Descended from disapproved goddesses, it’s usual for fictional witch queens to be beautiful, sexual women of great power, selfishness and cruelty. Check out T.H. White’s Morgause, Queen of Orkney, busy – on the first occasion we meet her – boiling a cat alive, and all for nothing: nearing the end of the spell, Morgause can’t be bothered to continue. She’s the mother from hell. Adored by her sons, she alternately neglects, torments and smothers them. She uses everyone she meets and is the ruin of most of them. The title of the book in which she appears, "The Queen of Air and Darkness", comes from the well known poem by A.E. Housman, worth quoting in full:

Her strong enchantments failing,

Her towers of fear in wreck,

Her limbecks dried of poisons

And the knife at her neck

The Queen of air and darkness

Begins to shrill and cry,

'O young man, O my slayer.

Tomorrow you shall die.'

O Queen of air and darkness,

I think 'tis truth you say,

And I shall die tomorrow,

But you shall die today.

It's an extraordinary conjuration of fear and violence, and antagonism not only between the sexes but possibly between the generations. There is no sympathy, no possibility of mercy towards this Queen. She is to be destroyed as one might kill a snake.

T.H. White was a man tormented by his own sexuality and suppressed sado-masochistic tendencies. He had a terrible relationship with his own mother, and once wrote to his friend David Garnett (asking him to call on her), “She is a witch, so look out, if you go.” In Elisabeth Brewer’s critical work, ‘T.H. White’s The Once and Future King’, 1993, White is quoted as describing Morgause thus:

She should have all the frightful power and mystery of women. Yet she should be quite shallow, cruel, selfish…One important thing is her Celtic blood. Let her be the worst West-of-Ireland type: the one with cunning bred in the bone. Let her be mealy-mouthed: butter would not melt in it. Yet also she must be full of blood and power.

Blood and power (and racism): White is clearly very frightened of this woman, who both fascinates and repels him. He didn’t find his Morgause in Malory. Malory’s Queen Morgawse isn’t even an enchantress like her half-sister Morgan Le Fay. ‘Le Morte D’Arthur’ presents her as a great lady whose sins are adulterous rather than sorcerous. No: White created his Morgause out of his own fears and loathings.

Whether or not ‘The Once and Future King’ is really a book for children – I first read it as a young teen – the Narnia books certainly are, and contain two excellent examples of the Witch Queen: Jadis of ‘The Magician’s Nephew’, who reappears as the White Witch in ‘The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe’; and the Green Witch of ‘The Silver Chair’, who shares many characteristics with fairy queens of the Unseelie Court. (But let’s stick to witches for now.) Jadis is proud, cruel, ruthless and ambitious, and as the White Witch and usurper of Narnia, actually sacrifices Aslan the Lion. Lewis traces her descent from Lilith and – in ‘The Magician’s Nephew’ – she is seen stealing the apples of Life in a scene echoing the transgression of Eve. The comedy of the chapter in which she riots through London, balancing on top of a hansom cab as if it were a chariot, does suggest some wicked delight on the part of the author – perhaps mostly because of Uncle Andrew’s complete discomfiture. Lewis is making a point about different types of evil: where Uncle Andrew is slimy and small-minded, Jadis has beauty, style and magnificence: but we are not to approve of either of them. The Green Lady, by contrast, is softly spoken, charming, ‘feminine’ – and sly, dangerous and deceitful. Women, Lewis clearly feels, should be neither domineering nor manipulative…

Celtic legends have provided the attributes of many a witch-queen of modern times. The foremost is Alan Garner’s ‘the Morrigan’, a name borrowed from Irish legend and originally probably that of a war goddess. The name is variously translated as Great Queen or Phantom Queen. At any rate, in Garner’s ‘The Weirdstone of Brisingamen’ and ‘The Moon of Gomrath’, she appears as the death or crone aspect of the triple Moon Goddess: the roles of maiden and mother being taken respectively by the young heroine Susan, and the Lady of the Lake Angharad Goldenhand. Dividing up the feminine in this way allows the author to approve maiden and mother (on the time-honoured Madonna pattern) while disapproving the crone. The Morrigan isn’t all that old, but she seems so to Susan, and is physically unattractive:

She looked about forty-five years old, was powerfully built (“fat” was the word Susan used to describe her), and her head rested firmly upon her shoulders without appearing to have much of a neck at all. Two deep lines ran from wither side of her nose to the corners of her wide, thin-lipped mouth, and her eyes were rather too small for her broad head. Strangely enough her legs were long and spindly, so that in outline she resembled a well-fed sparrow, but again that was Susan’s description… Her eyes rolled upwards and the lids came down till only an unpleasant white line showed; and then she began to whisper to herself.

('But again that was Susan's description' - this is oddly arch, for Garner. It's as if he's disassociating himself from Susan's opinion: the subtext is that you might not want to believe her - but why? Because Susan might be jealous? Because you can't ever wholly trust what one female says about another?)

Anyway. Frightening, powerful, ruthless, the Morrigan wastes no time in trying to conjure the children into her car so that she can take the ‘Bridestone’ from Susan. Later, in the second book, ‘The Moon of Gomrath’, the Morrigan is revealed in her true strength. In a chapter which still makes my spine prickle after years of re-reading, Susan faces the Morrigan outside the ruined house which is only ‘there’ in the moonlight:

Now Susan felt the true weight of her danger, when she looked into eyes that were as luminous as an owl’s with blackness swirling in their depths. The moon charged the Morrigan with such power that when she lifted her hand even the voice of the stream died, and the air was sweet with fear.

Susan and the Morrigan vie with one another, black and silver lances of power jetting from their mirror-opposite bracelets, and when at last Susan wins by blowing the horn of Angharad Goldenhand, it’s an all-female victory by which the world is unsettlingly changed: Susan’s brother Colin hears a sound ‘so beautiful he never found rest again’, and ‘the Old Magic was free for ever, and the moon was new.’ Is this a good thing or a bad thing? Garner’s answer appears to be that it’s an unavoidable natural force, and each individual will have to come to his or her own terms with it.

Powerful, magical, beautiful as the books are, Garner is forced into an awkward distinction between the Black Magic supposedly practised by the Morrigan, and the Old Magic of the elemental Wild Hunt and the moon maidens Susan and Angharad. It seems a little illogical to brand the Old Moon as evil while the New and Full Moons are good… I’m not sure quite where the Morrigan’s evil really resides, and I think LeGuin would say that we need to accept the darkness as well as the light. (In Garner's recent sequel, 'Boneland' he take a fresh look at the Morrigan.) But the books are brilliant, and the Morrigan is another unforgettable witch-queen.

Moving on from the Celtic goddesses, we come to some witches of more mundane appearance. First, Emma Cobley of Elizabeth Goudge’s ‘Linnets and Valerians’. Goudge was a spiritual, religious writer: also an intelligent, questioning one, and there are some moving passages in her adult books about the trials of mental illness. She was conscious of goodness as a great force, and of evil as a force almost as strong. In this book, Emma Cobley is an elderly postmistress of humble background; as a young, vivid girl she was in love with Hugo Valerian, the squire; and when he married the doctor’s daughter Alicia, in jealous hatred she cast spells on him and his wife and child. Spells for ‘binding the tongue’, for causing loss of memory, for ‘a coolness to come between a man and a woman’: little images carved of mandrake root with pins piercing the tongue or heart. Emma keeps the village shop, full of tempting sweets like the witch’s house in Hansel and Gretel, and owns a black cat which can change size. The wickedness in the book is an expression of the capacity of the human soul to cling to destructive passions.

As is the acquisitiveness of the next witch: Dr Melanie D. Powers, of Lucy Boston’s ‘An Enemy at Green Knowe’. (For those who don’t know the Green Knowe series, it’s a set of gentle but eerie ghost stories set in Lucy Boston’s own wonderful 11th century manor house, and I can’t praise it too highly.) The grandson of the house, Tolly, and his friend Ping, pit themselves against his grandmother’s new neighbour, a prying, malicious woman, a Cambridge don and scholar of the occult, who has – we slowly realise – struck a Faustian bargain with the devil. She has got wind of an ancient occult manuscript to be found in the manor house, and will stop at nothing to get hold of it. Miss Powers (who has an unaccountable dislike of passing in front of a mirror) invites herself to tea at the manor, and makes ultra-sweet conversation with such ominous lines as:

As is the acquisitiveness of the next witch: Dr Melanie D. Powers, of Lucy Boston’s ‘An Enemy at Green Knowe’. (For those who don’t know the Green Knowe series, it’s a set of gentle but eerie ghost stories set in Lucy Boston’s own wonderful 11th century manor house, and I can’t praise it too highly.) The grandson of the house, Tolly, and his friend Ping, pit themselves against his grandmother’s new neighbour, a prying, malicious woman, a Cambridge don and scholar of the occult, who has – we slowly realise – struck a Faustian bargain with the devil. She has got wind of an ancient occult manuscript to be found in the manor house, and will stop at nothing to get hold of it. Miss Powers (who has an unaccountable dislike of passing in front of a mirror) invites herself to tea at the manor, and makes ultra-sweet conversation with such ominous lines as:“One can sense that yours is a very happy family. Happy families are not so frequent as people make out. And unfortunately they are easily broken up. Very easily.”

She refuses to take a small cake:

“Grown-ups do better without extra luxuries like that. It is enough for me to look at them.”

In fact, it seemed to Tolly that she could not take her eyes off them… About half an hour later when tea was over… Mrs Oldknowe offered to lead the way upstairs to see the rest of the house. Miss Powers was standing with her back to the table, her hands clasped behind her, lingering to look at the picture over the fireplace, when Tolly… saw one of the little French cakes move, jerkily, as if a mouse were pulling it. Then it slid over the edge of the plate… and into the twiddling fingers held ready for it behind Miss Powers’ back.

And this tells us everything we need to know about Miss Powers. Petty, deceitful, covetous, full of malice, she is a truly evil person. The damage she causes is real: the boys’ beloved grandmother, Mrs Oldknowe, is nearly defeated by her; and the triumph of good over evil – the grand climax when, in the midst of a total eclipse of the sun, her demon is finally driven out of her – is only precariously achieved.

Pettiness and selfish ambition are qualities lavishly displayed by Gwendolen Chant, of Diana Wynne Jones’ ‘Charmed Life’. Wynne Jones writes even-handedly about good and evil witches, warlocks and wizards, but Gwendolen is one of the worst of the bunch. What Wynne Jones despises above all is exploitation of others and betrayal of trust. Gwendolen, a pretty girl with blue eyes and golden hair, exploits and betrays her younger brother Cat to the extent of actually causing his death on several occasions – since Cat, as she knows and he doesn’t, is a nine-lifed enchanter. Gwendolen uses his extra lives to enhance her own powers of witchcraft. Like some of the witches I wrote about last week, Gwendolen has no problem with the sort of anti-social behaviour which can be entertaining to behold – as Cat says, ‘I quite liked some of the things she did’ – but we are left in no doubt that she has gone too far when she conjures up what we later discover to be the apparitions of Cat’s lost lives:

The first was like a baby that was too small to walk – except that it was walking, with its big head wobbling. The next was a cripple, so twisted and cramped upon itself that it could barely hobble. The third was… pitiful, wrinkled and draggled. The last had its white skin barred with blue stripes. All were weak and white and horrible.

So there’s the range of seriously presented evil witches in children’s fiction, from glamorous witch queens to extremely nasty little girls. All of the witch queens I could call to mind have been created by men; women writers have created more domestic and less obviously dramatic characters. I leave you to decide what the different examples say, individually, about the various authors’ attitudes to women. Next post will be about the sympathetic presentation of witches – children’s books where witches are given an altogether more positive aspect.

© Katherine Langrish 27 August 2010

Published on August 31, 2013 01:07

August 24, 2013

Witches in Children's Literature

Macbeth: How now, you secret, black and midnight hags? What is’t you do?Witches: A deed without a name.

Macbeth: How now, you secret, black and midnight hags? What is’t you do?Witches: A deed without a name.“Witch” is not a neutral word. You can have good wizards or bad wizards, it seems, and when you encounter a fictional wizard you cannot be certain what leanings he may have. (Gandalf is good, Saruman is bad.) But the default option for a fictional witch is that she will be wicked, unless the qualifying adjective ‘white’ is used. There is a gender-based difference here.

My friend the YA writer Leslie Wilson has pointed out to me that African witches can be men. I wonder, though, if there are translation issues here, as there were for the ‘witch’ of Endor. Who was it who first chose ‘witch’ as the correct translation for whatever the African words for these people are? Why ‘witch’ rather than ‘sorcerer’ or ‘shaman’? The name you give to something affects or reflects the way you think about it. I notice that we in the west tend to refer to African ‘tribes’, which sounds primitive. When we refer to ourselves we speak of nations – or, on a more familial level, clans. Was ‘witch-doctor’ a term used in disparagement? Someone reading this may know.

But in any case, I still think the ‘wicked’ aspect of the witch is linked to male fear of female power. Ursula LeGuin’s Earthsea books turned into an almost philosophical exploration of this thought. In the first book, ‘A Wizard of Earthsea’, wonderful and complex though it is, the usual stereotypes apply, as expressed in a couple of Gontish proverbs: Weak as women’s magic or wicked as women’s magic. ‘Good’ women in the book are unlearned and domestic. The others are either ignorant crones with a few half-understood cantrips and charms, or else powerful, beautiful, ambitious and ruthless. Reading the Earthsea books through in sequence is to follow LeGuin’s impressive journey from acceptance of this stereotype, to questioning of it, to utter rejection.

In popular usage, even in this day and age, calling a woman a ‘witch’ is never complimentary – but neither is it entirely without positive implications. A ‘witch’ is a woman who may be perceived as (illicitly) powerful, throwing her weight about, inspiring fear or envy. (As Cherie Blair and Hilary Clinton have been perceived.) A ‘witch’ is a woman who cannot be ignored.

And in this spirit, a spirit of subversive enjoyment, I think many of the witches of children’s fiction have been conceived. I’m going to start off with a favourite from my own childhood, out of print now for many years: Beverley Nichols’ fantasy series for children beginning with ‘The Tree That Sat Down’. Here we meet the unforgettable Miss Smith. She looks like a Bright Young Thing, ‘as pretty as a pin-up girl’; she is actually three hundred and eighty-five years old; her familiars are three quite disgusting toads whom she keeps in the refrigerator; she puffs green smoke from her nostrils in moments of stress; she flies a Hoover instead of a broomstick, and she takes an energetic delight in wickedness with which the author clearly had enormous fun. As Miss Smith walks through the wood (on her way to make trouble for little Judy and her grandmother who keep a shop in the Willow Tree),

And in this spirit, a spirit of subversive enjoyment, I think many of the witches of children’s fiction have been conceived. I’m going to start off with a favourite from my own childhood, out of print now for many years: Beverley Nichols’ fantasy series for children beginning with ‘The Tree That Sat Down’. Here we meet the unforgettable Miss Smith. She looks like a Bright Young Thing, ‘as pretty as a pin-up girl’; she is actually three hundred and eighty-five years old; her familiars are three quite disgusting toads whom she keeps in the refrigerator; she puffs green smoke from her nostrils in moments of stress; she flies a Hoover instead of a broomstick, and she takes an energetic delight in wickedness with which the author clearly had enormous fun. As Miss Smith walks through the wood (on her way to make trouble for little Judy and her grandmother who keep a shop in the Willow Tree),… all the evil things in the dark corners knew that she was passing… The snakes felt the poison tingling in their tails and made vows to sting something as soon as possible. The ragged toadstools oozed with more of their deadly slime… In many dark caves, wicked old spiders, who had long given up hope of catching a fly, began to weave again with tattered pieces of web, muttering to themselves as they mended the knots…

Miss Smith’s fetching exterior allows her to inveigle her way into all sorts of places. For example, she deals with the evil Sir Percy Pike who preys upon widows and orphans by lending money at extortionate rates. Miss Smith is ‘also very keen on widows and orphans’, and – driven by professional jealousy – presents herself to Sir Percy in the guise of a beautiful widow, bedizened with diamond rings.

At the sight of these rings Sir Percy began to dribble so hard that he had to take out a handkerchief and hold it over his chin. … No sooner had he shut the door, than she spat in his face, hit him sharply on the chin with the diamond rings, knelt on his chest, and proceeded to tell him exactly what she thought of him.

You can’t help cheering – even though Miss Smith is just as bad herself. She comes into all Beverley Nichols’ children’s books: the others are ‘The Stream that Stood Still’, ‘The Mountain of Magic’ and ‘The Wickedest Witch in the World’. Though she is of course foiled on every occasion, hers is the energy that drives the narrative.

Next on my list is the witch Sylvia Daisy Pouncer in John Masefield’s ‘The Midnight Folk’ (Heinemann, 1927) and – though appearing to a lesser extent – in the sequel, ‘The Box of Delights’. Little Kay Harker is a lonely, imaginative child: the book is peopled with his imaginary friends, toys, pet cats and ancestors who may or may not be ‘really there’. His life is ruled by the strict and over-fussy governess Miss Pouncer:

“Don’t answer me back, sir,” she said. “You’re a very naughty, disobedient little boy, and I have a very good mind not to let you have an egg. I wouldn’t let you have an egg, only I had to stop your supper last night. Take off one of those slipper and let me feel it. Come here.”Kay went up rather gingerly, having been caught in this way more than once. He took off one slipper and tended it for inspection.“Just as I thought,” she said. “The damp has come right through the lining, and that’s the way your stockings get worn out.” In a very pouncing way she spanked at his knuckles with the slipper…

It’s perhaps not surprising, then, that at night when the Midnight Folk reign in the old house, Miss Pouncer is cast in the role of the chief witch:

There were seven old witches in tall black hats and long scarlet cloaks sitting round the table at a very good supper. They were very piggy in their eating (picking the bones with their fingers, etc) and they had almost finished the Marsala. The old witch who sat at the top of the table…had a hooky nose and very bright eyes. “Dear Pouncer is going to sing to us,” another witch said.

And Pouncer does, to great effect:

“When the midnight strikes in the belfry darkAnd the white goose quakes at the fox’s bark,We saddle the horse that is hayless, oatless,Hoofless and pranceless, kickless and coatless,We canter off for a midnight prowl…” All the witches put their heads back to sing the chorus:“Whoo-hoo-hoo, says the hook-eared owl.”

No wonder Nibbins, Kay’s cat, exclaims, “I can’t resist this song. I never could.” Wicked the witches may be, but once again the author relishes their energy, their subversive delight.

Another small boy in the clutches of a powerful female is the Wart in the hands of Madam Mim, in T.H. White’s “The Sword in the Stone”. This passage was cut from “The Once and Future King” – perhaps White thought it was too burlesque for the soberer, more epic quality of the longer work? (The witch of “The Once and Future King” is of course the Queen of Air and Darkness, the terrifying Queen of Orkney.) Madam Mim is a humbler creation, but probably all too familiar to any little boy whose mother or nurse undressed him for an unwanted bath. Madam Mim forcibly undresses The Wart with an eye to popping him in the pot and cooking him, singing a chicken-plucking song as she does so:

“Pluck the feathers with the skinNot against the grain-oh.Pluck the small ones out from in,The great with might and main-oh.Even if he wriggles, never mind his squiggles,For mercifully little boys are quite immune to pain-oh.”

The Scots writer Nicholas Stuart Grey created another memorable witch in ‘Mother Gothel’, the desperately evil witch in “The Stone Cage” (Dobson 1963), his retelling of the fairytale Rapunzel. Here, the fun and energy of the story belongs to the narrator, Mother Gothel’s cat Tomlyn – whose cynical and laconic style belies the fact that his heart is in the right place. The witch herself is powerful, terrifying, slovenly, sluttish, but ultimately pathetic and redeemable.

More wicked witches next week – this time, some of the darker and more serious treatments. © Katherine Langrish 23 August 2010 Picture credits:Miss Smith the witch: illustrations by Isobel and John Morton-Sale from Beverley Nichols' 'The Tree that Sat Down'

Published on August 24, 2013 02:03

August 16, 2013

Magical Rooms in Children's Fiction

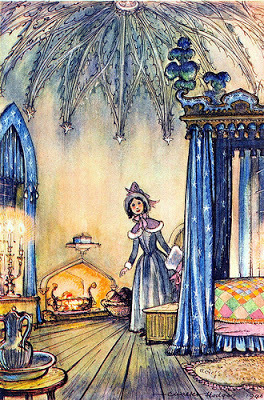

Maria's room - C. Walter Hodges, with thanks to http://www.flickr.com/photos/squatbet...

Maria's room - C. Walter Hodges, with thanks to http://www.flickr.com/photos/squatbet...When I was about twelve, my brother and I had a den in an unused outbuilding belonging to the house we lived in. We trod a narrow winding path through a deep bed of green nettles to get to the flaking, rickety door; we whitewashed the walls and found some old broken stools and chairs to furnish it. It was our private place. And we made a cardboard sign to hang on the door and ward off intruders: it read, in drippy red paint: Beware! 10,000 Volts!

But, especially in children’s fiction, secret rooms can mean a lot more than Bettelheim’s Freudian explanation. How many books did you read as a child, where the discovery of a concealed room was one of the most exciting parts of the story? Enid Blyton had them by the dozen. I well remember one (in ‘The Rockingdown Mystery’) where the hero, blue-eyed Barney, spends several nights in the deserted but poignantly furnished nursery of an eerie abandoned house - full of old dolls and damp, moth-eaten blankets, with strange noises echoing up through the floor. You know he’s not going to stay there, he’s going to go down exploring through the dark abandoned house, he’s going to find …what?

Hidden rooms in children's fiction are transitional places, they have meaning, they hold some clue that leads elsewhere. In Jane Langton’s 1962 classic ‘The Diamond in the Window’, Eleanor and Edward discover the ‘hidden’ room at the top of the tower – with, significantly, a keyhole-shaped stained-glass window – from which, years ago, two children with exactly the same names disappeared. The keyhole has no sexual implications here: it stands for the unlocking of mystery.

[Eleanor] was blinded at first by the dimness. Then the many colours of the great keyhole window blossomed… and gradually illumined the objects in the room… a huge mirror that was sunk into the well of an enormous dresser across the room from the window. There was a table, and what was that on the table? …It was a castle, a castle made of blocks. And there were chairs and toys, and a little wagon. And what was that on either side of the window? Eleanor’s heart bounded into her throat.It was two narrow beds, and the covers were turned neatly down.

‘Two narrow beds’ – there are suggestions here of death, absence, the mysteries of time. Just as in the book by Enid Blyton, these are traces of long-ago children who have vanished. This is a recurrent theme in children’s books: for it’s a sad and certain yet also glorious and fascinating truth that all children do disappear – into adulthood, and ultimately into death… which is presumably the meaning of that very unsettling short story by Walter de la Mare, ‘The Riddle’ – where, one after another, a whole family of children climb silently into a carved chest in the attic and disappear for ever.

But then there are bedrooms. Bedrooms, in children’s fiction, are places of magical refuge, yet full of possibility – as different as possible from the Bloody Chamber or the Ivory Tower.

A room of one’s own. Many children do not have one. They share with brothers or sisters. They lead lives ruled by adults. A room of one’s own, for a child, is a place where it can be in control. It’s also a place to start out from: the firm base of safety from which a child can explore the world. Rooms in children’s or young adult fiction, therefore, often reflect the desirable qualities of a perfect personal space.

Elizabeth Goudge was good at this. Maria, heroine of ‘The Little White Horse’, coming to the magic and mystery of Moonacre Manor, is provided with a bedroom in a tower with a door too small for an adult to get through. The room has three windows, one with a window seat, a ‘silvery oak floor’, and a four-poster bed ‘hung with pale blue silk curtains embroidered with silver stars’. And ‘the fireplace was the tiniest she had ever seen,’ but big enough for ‘the fire of pine cones and applewood that burned in it… It was the room Maria would have designed for herself if she had had the knowledge and the skill.’ From such a base Maria can with confidence launch her campaign against the men of the sinister Black Castle in the pine wood.

In ‘Linnets and Valerians’, perhaps Goudge’s masterpiece, the quieter heroine Nan is given a parlour of her own by her austere Uncle Ambrose. It opens off a dark passage, but then:

‘The room inside was a small panelled parlour. There was a bright wood fire burning in the basket grate, and on the mantelpiece above were a china shepherd and shepherdess and two china sheep. Over the mantelpiece was a round mirror in a gilt frame… Nan sat down in the little armchair and folded her hands in her lap… It was quiet in here, the noises of the house shut away, the sound of the wind and rain seeming only to intensify the indoor silence. The light of the flames was reflected in the panelling, and the burning logs smelt sweet.’ And yet, in the heart of this paradise a snake lurks: the discovery, in a cupboard, of an old notebook written by the witch Emma Cobley. ‘Nan sat down in the armchair with shaking knees, but nevertheless she opened the book and began to read.’

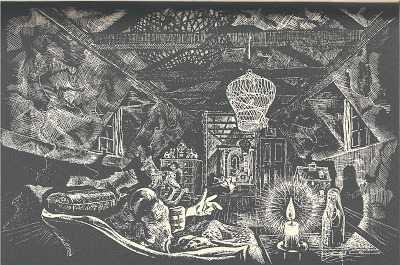

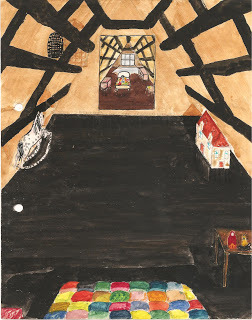

Tolly's room - Peter BostonIn each case, the rooms – though so utterly desirable – contain clues and hints of the past, of the passage of other people’s lives, and of mysteries which must be investigated. But the rooms give them the assurance to cope. Tolly’s delightful room in Lucy Boston’s ‘The Children of Green Knowe’ is filled with the toys, memories and ghostly presences of the children who lived there in the past and who become his companions. The picture above is Peter Boston's illustration of Tolly's room: as a child I loved it so much that I tried to paint my own version:

Tolly's room - Peter BostonIn each case, the rooms – though so utterly desirable – contain clues and hints of the past, of the passage of other people’s lives, and of mysteries which must be investigated. But the rooms give them the assurance to cope. Tolly’s delightful room in Lucy Boston’s ‘The Children of Green Knowe’ is filled with the toys, memories and ghostly presences of the children who lived there in the past and who become his companions. The picture above is Peter Boston's illustration of Tolly's room: as a child I loved it so much that I tried to paint my own version:  Tolly's room - Katherine Langrish (age 14)

Tolly's room - Katherine Langrish (age 14)In a similar way when Garth Nix’s Sabriel comes for the first time to the house of the Abhorsen, escaping terrifying dangers, it is a place of refuge:

‘The gate swung open, pitching her on to a paved courtyard, the bricks ancient, their redness the colour of dusty apples. The path wound up to…a cheerful sky-blue door, bright against whitewashed stone.’ And she wakes later, ‘to soft candlelight, the warmth of a feather bed…A fire burned briskly in a red-brick fireplace, and wood-panelled walls gleamed with the dark mystery of well-polished mahogany. A blue-papered ceiling with silver stars dusted across it faced her newly opened eyes.’

This is a place in which Sabriel cannot stay, but which belongs to her: it will strengthen her even though she must leave it. It’s also a place in which she will learn more about her family, her past.

It’s not a fantasy, but Betsy Byars’ ‘The Cartoonist’ is also about a child's need for a personal space and the strength he derives from it. The only place in Alfie’s crowded house where he can be himself is in his attic, where he expresses himself by drawing the cartoons that are his life-blood. So long as he has his attic, he can cope with the demands of his noisy, feckless family:

‘The only thing Alfie liked about the house was the attic. That was his. He had put an old chair and a card-table up there, and he had a lamp with an extension cord that went down into the living room. Nobody ever went up there but Alfie. Once his sister, Alma, had started up the ladder, but he had said, “No, I don’t want anybody up there…I want it to be mine.”’

When the family decide over his head that his older brother can have the attic, Alfie’s entire personal existence – and his imaginative life – feels threatened. He barricades himself in.

And in Michael Ende’s ‘The Never-Ending Story’, Bastian hides himself in the school attic ‘crammed with junk of all kinds’: ‘Not a sound to be heard but the muffled drumming of the rain on the enormous tin roof. Great beams blackened with age rose at regular intervals… and lost themselves in darkness. Here and there spider webs as big as hammocks swayed gently in the air currents.’ Sinister it may seem, but this is a safe place, a place where Bastian can open the Never-Ending Story and escape into fiction.

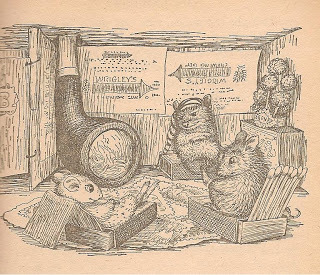

The mouse-hole in the Black Castle - Garth WilliamsMagical rooms, magical personal spaces, abound in children’s fiction. In Margery Sharp’s ‘The Rescuers’, I was charmed as a child by the cosy home the mice build in the heart of The Black Castle whilst eluding the dreadful cat Mameluke and trying to rescue the imprisoned Poet. The hole becomes:

The mouse-hole in the Black Castle - Garth WilliamsMagical rooms, magical personal spaces, abound in children’s fiction. In Margery Sharp’s ‘The Rescuers’, I was charmed as a child by the cosy home the mice build in the heart of The Black Castle whilst eluding the dreadful cat Mameluke and trying to rescue the imprisoned Poet. The hole becomes: ‘a commodious apartment… Gay chewing gum wrappers papered the walls, while upon the floor used postage stamps, nibbled off envelopes in the Head Jailer’s wastebasket, formed a homely but not unsuitable patchwork carpet. Miss Bianca with her own hands fashioned several flower-pieces – so essential to gracious living – dyed pink or blue with red or blue-black ink’.

And there’s the fire’ of course – ‘a fire of cedarwood’ made from cigar boxes.

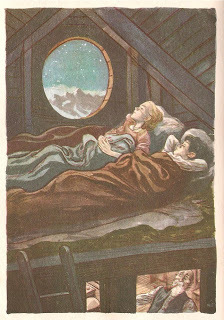

Heidi's hayloft - William SharpI remember wishing I, like Heidi, could have a bedroom up a ladder in a hay-loft, where Heidi sleeps ‘as soundly and well as if she had been in the loveliest bed of some royal princess’. And to this bedroom she returns later in the book with her rich, lame friend Klara:

Heidi's hayloft - William SharpI remember wishing I, like Heidi, could have a bedroom up a ladder in a hay-loft, where Heidi sleeps ‘as soundly and well as if she had been in the loveliest bed of some royal princess’. And to this bedroom she returns later in the book with her rich, lame friend Klara: ‘They all stood round Heidi’s beautifully made hay bed…drawing deep breaths of the spicy fragrance of the new hay. Klara was perfectly charmed with Heidi’s sleeping place. “Oh Heidi! From your bed you can look straight out into the sky, and you can hear the fir trees roar outside. Oh I have never seen such a jolly, pleasant sleeping room before.”’

This mountain home will give strength to Klara and heal her.

And isn’t part of the charm in Frances Hodgson Burnett’s ‘A Little Princess’ the way in which Sara’s attic room is transformed, first by the power of her imagination and then by a reality which she calls ‘the magic’, from a cold, inimical space into a place which comforts and sustains both body and soul?

‘“Supposing there was a bright fire in the grate, with lots of little dancing flames,’ she murmured. ‘Suppose there was a comfortable chair before it – and suppose there was a small table nearby with a little hot – hot supper on it. And suppose”- as she drew the thin coverings over her – “suppose this was a beautiful soft bed, with fleecy blankets and large downy pillows. Suppose – suppose –’ And her very weariness was good to her, for her eyes closed and she fell fast asleep.”

Of course she awakes and finds it’s all come true…

Secret rooms in children’s fiction are not Freudian symbols of sexual awakening, neither are they sterile ivory towers from which it is necessary to be rescued. Hidden rooms are exciting places in which clues can often be found to understanding the child’s personal history and place in the world. Children’s own rooms are magical personal spaces in which the child is protected and nourished, from which she - or he - can draw the strength and confidence to set out on adventures.

© Katherine Langrish 10 July 2011

Published on August 16, 2013 00:32

August 9, 2013

Good News! And Bad News -

Please don't worry though! Actually the bad news isn't so bad. I'm about to take a break from this blog, but I fully intend to be back here some time in the autumn with a new selection of wonderful guest writers, Magical Classics, Folklore Snippets, and possibly even Fairytale Reflections, as well as anything else that strikes me about the wonderful world of folklore, fairytale and fantasy.

I began 'Steel Thistles' in December of 2009, and I've been blogging pretty well steadily ever since, at least once a week and sometimes more. I've enjoyed every moment of it. But - and here is the good news! - during that time I've also been researching and writing my new book. In fact, I even mentioned the book in that very first post of more than four years ago - which is a rather scary thought! It's the longest I've ever taken over writing a book - I'm one of those 'revise as you go' writers - and I'm now finally beginning the last chapter.

I'll tell you a little tiny bit about it: it's YA (ie: for Young Adults), and it's set in the future, in the same world as the short story 'Visiting Nelson' which I wrote for the Terri Windling/Ellen Datlow anthology AFTER (whose cover you can see in the right hand column). I've been living and dreaming it for so long, I can hardly believe I'm nearly there. (Except, and this is good,the next thing I have to do is write the sequel!)

So, dear reader, I need to take time off, have a breathing space, let the well of inspiration refill - all that stuff. In the mean time, I hope you'll keep visiting, because I'm going to be reposting one of my older posts each week, things you may have not seen - or forgotten. Also, I'd like to tell you again the story of how this blog got its rather strange title - 'Seven Miles of Steel Thistles'.

It comes from a phrase in a West Irish fairytale called The King Who had Twelve Sons, in which the hero has to ride 'over seven miles of hill on fire, and seven miles of steel thistles, and seven miles of sea'.

I read that, and I thought it was a good metaphor for life in general and the craft of writing in particular. It can be a long hard journey, but you get there. In the end.

Even though I won't be writing new posts for a while, I'll be dropping in myself regularly, so I hope you'll leave comments, and we can keep talking. And here's the very first post I ever wrote for this blog, with that reference to the now-almost-completed-book.

See you in the autumn!

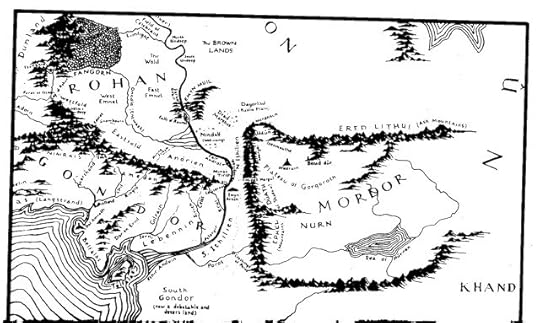

THE ECONOMY OF MORDOR

For nefarious reasons connected with my next book, I’ve been investigating towers, and as one thing leads to another and fictional towers tend to carry the mind to Dark Towers, I found myself – and not for the first time – considering the economy of Mordor. You could hardly complain about the amount of creative thought and background research that JRR Tolkien put into creating the world of Middle-Earth, but he was undeniably stronger on history and languages than he was on geography and economics.

A look at the map is instructive. Mordor is a landlocked country, surrounded on three sides by suspiciously straight lines of mountains. In the north-west is the Plateau of Gorgoroth, perhaps volcanic; doubtless dry and cold, for no rivers run from it. To the south-east is the low-lying and bitter Sea of Nurnen. No navigable rivers flow out of Mordor, though the River Harnen has its source just beyond the southern border. The Great River Anduin curves provocatively close to Mordor’s western frontier, but there appear to be only two passes through the Ephel Duath: Minas Morgul represents one; the Morannon or ‘Black Gate’ the other.

Trade-routes to the west, therefore, are few and far between. To the east Mordor lies open, but although we sometimes hear of ‘Easterlings’or ‘Wainriders’ – enemies of Gondor – they are characterised as wild nomadic tribesmen, unlikely sources of supplies. South Gondor is marked on the map as ‘a debatable or desert land’, and Near Harad, Haradwaith and Khand appear utterly devoid of forests, rivers, cities or hills. It’s a complete puzzle how the ‘Southrons’ who ally themselves with Mordor find the resources to muster their vast armies mounted on oliphaunts.

Mordor itself is an ecologist’s nightmare: a wasteland of slag and ash, scored with gaping fissures and rocky ridges, governed by an evil all-seeing Eye on the top of a vast Dark Tower not too far from an active volcano which pours out ever more ash and smoke. Nothing grows. There’s hardly any rain, and any trickle of water running through the polluted land swiftly becomes poisoned.

In the course of rescuing Frodo from the Tower of Cirith Ungol, Sam raises a question that suggests Tolkien may have experienced a slight frisson of doubt about the non-availability of food in Mordor. ‘Don’t orcs eat, and don’t they drink? Or do they just live on foul air and poison?’ Frodo assures Sam that on the contrary, orcs do eat: ‘Foul waters and foul meats they’ll take, if they can get no better, but not poison.’

Armies, as we know, march on their stomachs. I can see that an enormous fiery Eye isn’t going to care that in all his wide lands there’s not a bite to eat; and the Nine Ringwraiths probably don’t mind much either. But the orcs? How do they benefit from serving Sauron? And Frodo watches whole armies marching into Mordor via the northern Black Gate: ‘men of other race, out of the wide Eastlands, gathering to the summons of their Overlord.’ What on Middle-Earth are they thinking of? What can they expect to gain from rallying to the aid of a Dark Lord who rules a bankrupt country with no agriculture, no exports or imports and no internal food supplies? There isn’t even the prospect of future riches if Gondor falls to Sauron – for in that case Gondor itself will become a similar wasteland.

In any normal world economy, Mordor would be over its ears in debt. Refugees – orcs, Easterlings and Southrons – would be streaming westwards in the hope of better lives for themselves in Gondor. Rather than closing its gates against an invading army, Minas Tirith would be coping with an influx of immigrants. The tough and hardy orcs would hire themselves out as cheap labour in exchange for a few coppers and a square meal. Mounted bands of Rohirrim would patrol the borders of Rohan to turn away fugitives. Dark Lord or no Dark Lord, Sauron would have no choice but to borrow money from the coffers of Minas Tirith – or from the metal-rich dwarfs – in order to keep Mordor from emptying itself. The power is with the purse strings.

Still, The Lord of the Rings is not a political satire. Perhaps we can be grateful that Tolkien didn’t look too closely at the economy of Mordor. Middle-Earth is a polarised world. The brave, the beautiful and the good are all grouped together on one side, while the wicked, the ugly and the cruel gravitate together on the other. So let’s hear it for the all-powerful Dark Lord, Ruler of the Wastelands, Commander of Ringwraiths, Leader of the Axis of Evil.

So long as we remember he doesn’t exist.

(21 December 2009)

Picture credits: John Bauer: illustration from The Ring - the link is here, with a fascinating essay about visual influences on Tolkien's world: http://www.touchstonemag.com/archives/article.php?id=15-01-041-f

Map of Mordor, from The Return of the King.

Published on August 09, 2013 02:04

August 2, 2013

Magical Classics: 'Harding's Luck' by E Nesbit