Magical Classics: "Puck of Pook's Hill" by Rudyard Kipling

John Dickinson on the midsummer magic of Kipling's children's classic

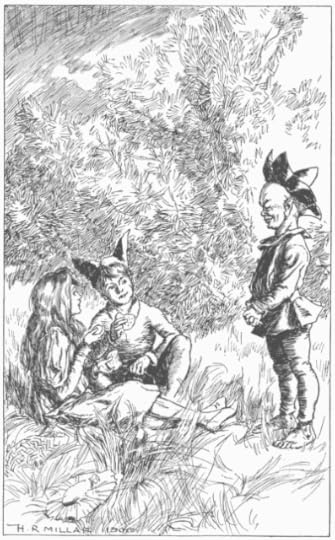

Two children, Dan and Una, perform a scene from Midsummer Night’s Dream three times on midsummer eve, in a fairy ring under the shadow of Pook’s Hill. They find they have summoned Puck himself, the last of the ‘People of the Hills’. Through him they meet characters out of the past – a Norman knight, a Roman centurion, a Tudor craftsman, and in the second book, Rewards and Fairies, many others including St Wilfred and Elizabeth I. Each one tells their story.

There are no dragons in Puck, no wizards, no spells except a little charm that Puck himself weaves with oak, ash and thorn. The magic is a framework for the stories, like a hazy golden halo around each one. So they are not really ‘fantasy’ as we now understand it. They are scenes out of history: the things that over the centuries (Kipling believed) had made England what it was.

At the beginning and end of each story there is a little poem: a sort of coda to the tale. Some have become famous in their own right (this is where you will find If… for example). In one of these Kipling tells us clearly what response he hoped for from his young readers.

‘Land of our Birth, our faith, our pride,For whose dear sake our fathers died;O Motherland, we pledge to theeHead, heart and hand through the years to be!’

(From The Children’s Song)

We are wary, these days, about telling history to inspire patriotism. We know what came next. If Dan was eight or nine when the stories were written, as he seems to be, then he would have been the same age as Kipling’s own son who was lost in the trenches in 1915. Kipling did not know, then, what was coming. But he knew what might.

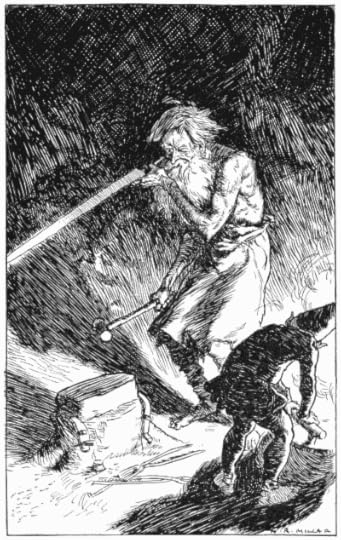

Read the stories again. There’s a mischievous delight in them, but also a sadness, a sense of hopes extinguished and things lost. There are no rewards. Crowds do not cheer and trumpets do not sound . ‘Finish’ says the word on the bricked up archway that the young centurion finds at the end of the road to Hadrian’s Wall. The Tudor architect gets his knighthood for entirely the wrong reason. The fairies raise a young boy hoping to make him a king, and he is fated to become a slave. As the cold iron ring clicks around his neck Puck says:

“…he must go among folk in housen henceforward, doing what they want done, or what he knows they need, all Old England over. Never will he be his own master, nor yet ever any man’s. He will get half he gives, and give twice what he gets, till he draws his last breath; and if he lays aside his load before he draws that last breath, all his work will go for naught.”

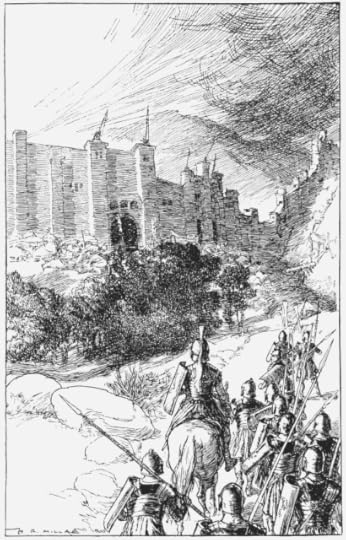

The words could have been spoken for any of the characters the children meet. They could have been spoken for Dan and Una themselves. It’s about unseen virtue, found where you least expect it. Harsh, hook-nosed Baron de Aquila schemes in his castle to prevent another Norman invasion. A fat, drunken Roman general, supplanted by younger men, is transformed in the desperate battle for the Wall. And the lead role in the climax of the first book goes to a despised Jew. It is Kadmiel who tricks the stupid Christians and traps a bad King, so that one key phrase passes into Magna Carta and becomes the heart of the law of England. And he never even sees it signed. ‘Nay. Who am I to meddle with things too high for me? I returned to Bury, and lent money on the autumn crops. Why not?’ That is Kipling’s kind of hero. Well. We could call it Edwardian moralising, and sneer at it for that. Fair’s fair. He would have sneered at the easy, wish-fulfilling stuff, lightly peppered with teenage angst, that we serve up for children now. But it’s a brave writer who sneers at Kipling.

Read the stories a third time (that’s the magic, you see.) Better still, find someone who will read them aloud with you. His words were made to be heard. Curl up and listen. Remember the delight of finding a secret friend – a magic friend, on the bare hill above your house. Imagine these strangely-dressed people, who tell stories of courage and cleverness and fate in voices as rich and grainy as the land they describe, and yet who respect you for the things you know that they never could. It’s all there, the wonder and high adventure hammered together into the words with the skill of a smith of gods. ‘Bold as a wolf, cunning as a fox was Witta!’ Hear the drum-beat in that line, as the Viking pirate steers his archers in to fight fierce apes for African gold! PC Kipling was not (and his natural history was shocking.) But he could write. He really could. You didn’t need me to tell you so.

John Dickinson is the son of the author Peter Dickinson, and worked in the Ministry of Defence, Cabinet Office and NATO before leaving the civil service to begin writing. His distinguished YA fantasy novel ‘The Cup of the World’ and its sequels ‘The Widow and The King’ and ‘The Fatal Child’ are set in a far-off, war-troubled medieval kingdom, and they are full of compelling, flawed characters and beautiful, ominous writing. John has also published a historical novel for adults, ‘The Lightstep’, set in a German palatinate at the time of the French Revolution, a science fiction novel called ‘WE’, which was nominated for the Carnegie Medal, and, for children, 'Muddle and Win: The Battle for Sally Jones', in which an angel and a demon struggle for the soul of the eponymous - and rather too Good - heroine. It's delightful, and you can find my review here.

Picture credits:

All illustrations by HR Millar, from 'Puck of Pook's Hill' by Rudyard Kipling, Macmillan & Co 1906

Published on July 19, 2013 01:16

No comments have been added yet.