Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 29

April 27, 2013

Blue Remembered Hills

This is where I lived when I was about fourteen, in a Herefordshire cottage up a mile of rough country lane, with the nearest visible house also at least a mile away, although there was in fact one hidden just over the brow of the hill behind us. Aged about fifteen (?) I decided to paint the view from the lawn in spring, summer and autumn (I never got around to painting winter: perhaps it just didn't snow, and I wanted snow). Anyway, a week or two back, I found the paintings at the bottom of a drawer. The hill to the right, covered in trees, is Lea Bailey, near Ross on Wye. The blue curve behind the bare elms is May Hill.

So here is spring. The houses over on Lea Bailey do look a bit like sugar cubes, and I never could figure out how to paint trees, but I loved that view, and I'm glad to see it again. Even if I could go back, it would not be the same. The elms were lost decades ago.

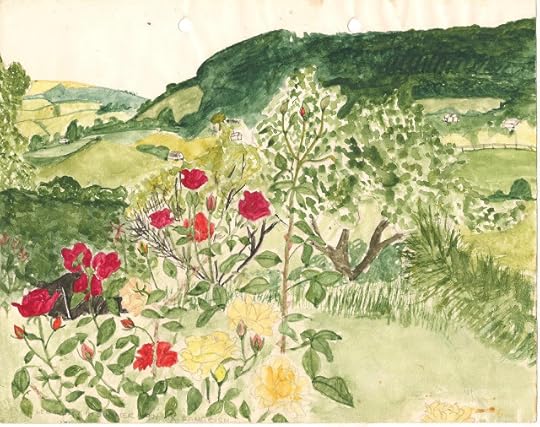

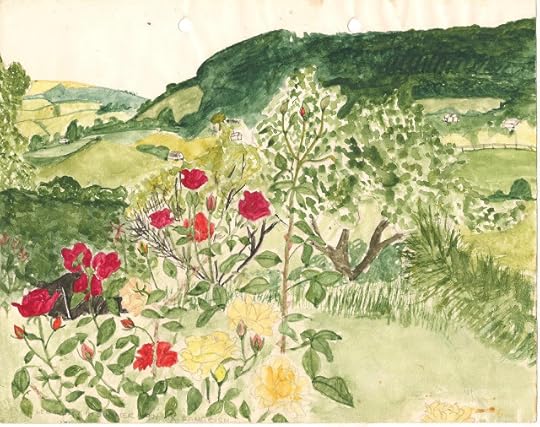

Here is summer. I remember the roses being a problem to paint. How to cope with the background behind them? How to deal with the foliage? I was using a child's paintbox and A4 paper torn from a pad. You can see the punch holes over the top of the hill. But lord, that was a garden. My mother had green fingers, and created beauty wherever she went (she still does) and I certainly couldn't do that garden justice.

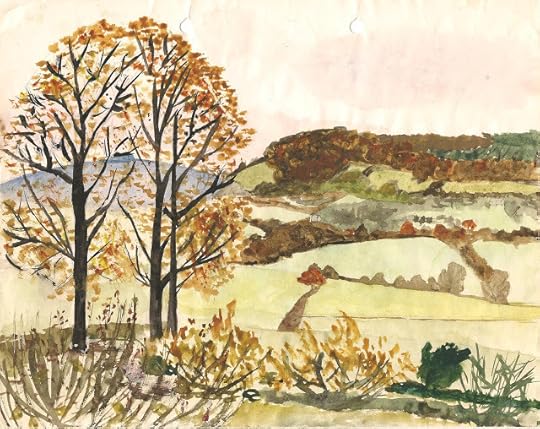

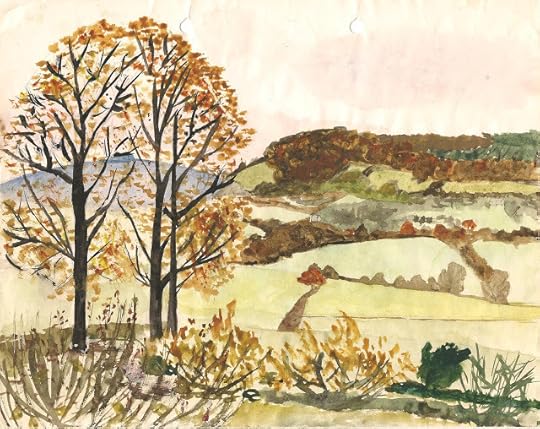

Autumn came... with misty mornings and May Hill appearing again behind the thinning elms. My brother and I took a bicycle ride there, once, and I remember how exciting it seemed to ride by ourselves all the way to the horizon. When you're there, May Hill is full of the sounds of larks singing, and of the wind sighing like the sea through the tall, tall pine trees which grow (grew?) in a clump on the very top. A lonely, gorgeous, magical place. A place to quote Housman. But back then it would have been 'Summertime on Bredon' that would have sprung to my mind, especially the lines:

And see the coloured counties,

And now?

INTO my heart an air that killsThat is the land of lost content,

So here is spring. The houses over on Lea Bailey do look a bit like sugar cubes, and I never could figure out how to paint trees, but I loved that view, and I'm glad to see it again. Even if I could go back, it would not be the same. The elms were lost decades ago.

Here is summer. I remember the roses being a problem to paint. How to cope with the background behind them? How to deal with the foliage? I was using a child's paintbox and A4 paper torn from a pad. You can see the punch holes over the top of the hill. But lord, that was a garden. My mother had green fingers, and created beauty wherever she went (she still does) and I certainly couldn't do that garden justice.

Autumn came... with misty mornings and May Hill appearing again behind the thinning elms. My brother and I took a bicycle ride there, once, and I remember how exciting it seemed to ride by ourselves all the way to the horizon. When you're there, May Hill is full of the sounds of larks singing, and of the wind sighing like the sea through the tall, tall pine trees which grow (grew?) in a clump on the very top. A lonely, gorgeous, magical place. A place to quote Housman. But back then it would have been 'Summertime on Bredon' that would have sprung to my mind, especially the lines:

And see the coloured counties,

And now?

INTO my heart an air that killsThat is the land of lost content,

Published on April 27, 2013 05:04

April 19, 2013

Seeing Angels

Reading Peter Ackroyd’s biography of William Blake (‘Blake’, Vintage) I found a marvellous account of how Blake saw the Archangel Gabriel in his study. Blake was reading Edward Young’s ‘Night Thoughts’ when he came to a passage where the poet asks ‘who can paint an angel?’ Blake shut the book and mused aloud:

Blake: Aye! Who can paint an angel?

Voice: Michel Angelo could.

He looked about but saw nothing except ‘a greater light than usual’.

Blake: And how do you know?

Voice: I know, for I sat to him: I am the arch-angel Gabriel.

Blake: Oho! You are, are you? I must have better assurance than that of a wandering voice; you may be an evil spirit – there are such in the land.

Voice: You shall have good assurance. Can an evil spirit do this?

And then Blake saw a shining, winged shape, which ‘dilated more and more: he waved his hands; the roof of my study opened; he ascended into heaven; he stood in the sun, and beckoning to me, moved the universe.’

As is well known, Blake saw visions all his life. As a child of about four he was frightened (his wife reminded him) by a vision of God who ‘put his head to the window and set you a-screaming’; as a slightly older child he saw a tree bespangled full of angels, and met the Prophet Ezekiel out in the fields. As a man, he saw, conversed with and drew ‘Spectres of the Dead’, angels, Jesus, ‘the ghost of a flea’. He saw ‘the Ancient of Days’ hovering at the top of his narrow, dim staircase.

The Ghost of a Flea

The Ghost of a Flea

None of this did him any favours in practical real-life terms. Some friends revered him, but a much larger proportion considered him eccentric and odd, if not outright mad. Blake was one of those artists and poets who are not much appreciated in their own lifetimes. He always struggled to make a living, and financial and social success eluded him. And yet he was rightly convinced of his own genius, so much so that one can’t feel the pity for him that one feels for Vincent Van Gogh or John Keats, dying before they could know of their own undying fame. Blake was so certain of the worth of his work, the truth and grandeur of his visions, that public recognition – though doubtless it would have been welcome – was not essential to him.

But what would we make of William Blake today? I don’t know about you, but if a neighbour buttonholed me one day and began to tell me that he’d recently been talking to John Milton – ‘I have seen him as a youth. And as an old man with a long flowing beard. He came lately as an old man’ – well, I might tend to back off. It is eccentric and odd to see angels, and it’s hard to blame Blake’s acquaintances for their scepticism which in turn fostered their general sense that he was a man who should not really be taken seriously.

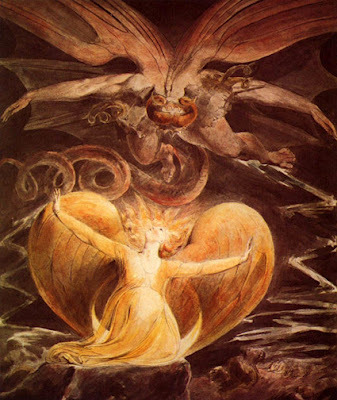

The Great Red Dragon & The Woman Clothed in the Sun

The Great Red Dragon & The Woman Clothed in the Sun

We make exceptions for genius with the benefit of hindsight. With the weight of a century or so of bolstering critical opinion, we all now recognise that William Blake was a genius, and so we suspend our disbelief about his visions. Who knows what a genius may or may not see? Perhaps we consider that, as an artist as well as a poet, Blake’s visual imagination produced images so vivid, so concrete, that in some way they did indeed ‘appear’ before him. Perhaps, as Peter Ackroyd suggests early in his book, the faculty of eidetic imagery, fairly common in children who see hallucinatory images as genuine sensory perceptions, was retained by Blake throughout his life.

Or perhaps he did see angels? What does it mean to say you see angels?

At any rate, this is a man who sang – and drew a picture of his wife – on his deathbed. “‘Stay Kate,’ he said, ‘keep just as you are – I will draw your portrait – for you have ever been an angel to me.’” His friend George Richmond (the artist who later drew the flattering portrait head of Charlotte Bronte) wrote to Samuel Palmer,

“He died on Sunday night at 6 Oclock in a most glorious manner. He said He was going to that Country he had all His life wished to see and expressed Himself Happy, hoping for Salvation through Jesus Christ – Just before he died His Countenance became fair. His eyes Brighten’d and He burst out Singing of the things he saw in Heaven.”

Or, as Blake himself wrote in ‘The Four Zoas’,

‘…he shook his aged mantles off

Into the fires Then glorious bright Exulting in his joy

He sounding rose into the heavens in naked majesty

In radiant youth.’

Albion

Albion

Blake: Aye! Who can paint an angel?

Voice: Michel Angelo could.

He looked about but saw nothing except ‘a greater light than usual’.

Blake: And how do you know?

Voice: I know, for I sat to him: I am the arch-angel Gabriel.

Blake: Oho! You are, are you? I must have better assurance than that of a wandering voice; you may be an evil spirit – there are such in the land.

Voice: You shall have good assurance. Can an evil spirit do this?

And then Blake saw a shining, winged shape, which ‘dilated more and more: he waved his hands; the roof of my study opened; he ascended into heaven; he stood in the sun, and beckoning to me, moved the universe.’

As is well known, Blake saw visions all his life. As a child of about four he was frightened (his wife reminded him) by a vision of God who ‘put his head to the window and set you a-screaming’; as a slightly older child he saw a tree bespangled full of angels, and met the Prophet Ezekiel out in the fields. As a man, he saw, conversed with and drew ‘Spectres of the Dead’, angels, Jesus, ‘the ghost of a flea’. He saw ‘the Ancient of Days’ hovering at the top of his narrow, dim staircase.

The Ghost of a Flea

The Ghost of a FleaNone of this did him any favours in practical real-life terms. Some friends revered him, but a much larger proportion considered him eccentric and odd, if not outright mad. Blake was one of those artists and poets who are not much appreciated in their own lifetimes. He always struggled to make a living, and financial and social success eluded him. And yet he was rightly convinced of his own genius, so much so that one can’t feel the pity for him that one feels for Vincent Van Gogh or John Keats, dying before they could know of their own undying fame. Blake was so certain of the worth of his work, the truth and grandeur of his visions, that public recognition – though doubtless it would have been welcome – was not essential to him.

But what would we make of William Blake today? I don’t know about you, but if a neighbour buttonholed me one day and began to tell me that he’d recently been talking to John Milton – ‘I have seen him as a youth. And as an old man with a long flowing beard. He came lately as an old man’ – well, I might tend to back off. It is eccentric and odd to see angels, and it’s hard to blame Blake’s acquaintances for their scepticism which in turn fostered their general sense that he was a man who should not really be taken seriously.

The Great Red Dragon & The Woman Clothed in the Sun

The Great Red Dragon & The Woman Clothed in the SunWe make exceptions for genius with the benefit of hindsight. With the weight of a century or so of bolstering critical opinion, we all now recognise that William Blake was a genius, and so we suspend our disbelief about his visions. Who knows what a genius may or may not see? Perhaps we consider that, as an artist as well as a poet, Blake’s visual imagination produced images so vivid, so concrete, that in some way they did indeed ‘appear’ before him. Perhaps, as Peter Ackroyd suggests early in his book, the faculty of eidetic imagery, fairly common in children who see hallucinatory images as genuine sensory perceptions, was retained by Blake throughout his life.

Or perhaps he did see angels? What does it mean to say you see angels?

At any rate, this is a man who sang – and drew a picture of his wife – on his deathbed. “‘Stay Kate,’ he said, ‘keep just as you are – I will draw your portrait – for you have ever been an angel to me.’” His friend George Richmond (the artist who later drew the flattering portrait head of Charlotte Bronte) wrote to Samuel Palmer,

“He died on Sunday night at 6 Oclock in a most glorious manner. He said He was going to that Country he had all His life wished to see and expressed Himself Happy, hoping for Salvation through Jesus Christ – Just before he died His Countenance became fair. His eyes Brighten’d and He burst out Singing of the things he saw in Heaven.”

Or, as Blake himself wrote in ‘The Four Zoas’,

‘…he shook his aged mantles off

Into the fires Then glorious bright Exulting in his joy

He sounding rose into the heavens in naked majesty

In radiant youth.’

Albion

Albion

Published on April 19, 2013 00:44

April 14, 2013

After the Apocalypse

It's been an exciting week. I was asked to go along to the BBC to discuss dystopian fiction on Radio 4’s Open Book, together with Gillian Cross whose new book ‘After Tomorrow’ has just been published. Our conversation is on air this afternoon at 4.00pm, will be repeated on Thursday afternoon at the same time, and is (I’m told) available as a BBC podcast.

It's been an exciting week. I was asked to go along to the BBC to discuss dystopian fiction on Radio 4’s Open Book, together with Gillian Cross whose new book ‘After Tomorrow’ has just been published. Our conversation is on air this afternoon at 4.00pm, will be repeated on Thursday afternoon at the same time, and is (I’m told) available as a BBC podcast. Gillian’s books are always wonderful. ‘After Tomorrow’ tells the tale of two boys escaping to France through the Channel Tunnel after an economic and political collapse in Britain. My own dystopian credentials currently rest in the post-apocalyptic short story ‘Visiting Nelson’ – the germ of the novel I’m currently writing – published in the Windling/Datlow anthology ‘AFTER’ which you can see in the margin of this blog - the third cover from the top.

So I thought I might extend the conversation here with some general thoughts about dystopian and post-apocalyptic YA fiction and its appeal. And I'd love to hear your own opinions and recommendations.

If a utopia envisions a perfect, well-functioning society which we’re expected to contrast with the failures of our own, a dystopia does the opposite. It presents us with a society which is dysfunctional, which has gone badly wrong – in which aspects of our own contemporary society are pushed to an extreme. Utopias and dystopias have always been forms of social criticism, not just ‘imaginary worlds’. Tolkien’s Mordor would be an unpleasant place to live, but it isn't and was never intended to be a dystopia - any more than beautiful Lothlorien is a utopia. Nothing about either of them critiques contemporary society. But a dystopia is about us, living our own lives in our own world, reflected in a glass, darkly.

Dystopias and post-apocalyptic novels are often confused with one another: but – if you think about them in terms of Venn diagrams – it’s easy to spot the differences. In the circle labelled ‘dystopias’ are books about bad, usually highly controlling societies which need to be defied, reformed, reshaped. In the circle labelled ‘post-apocalyptic fiction’, the books pose a different challenge. A catastrophe has changed the world for ever: the characters’ task is to survive and rebuild. Where the two circles touch and overlap, there are books which combine elements of both. A post-catastrophic world may well spawn a dystopian society.

Dyslit, to use Terri Windling and Ellen Datlow’s convenient coinage, is a tremendously dramatic way of writing about society, and society is a subject which deeply interests many young adult readers. Where children accept their parents’ belief systems as a given, teenagers are full of questions. They want to make up their own minds, to test and try and decide things for themselves. Often they are passionate and idealistic and wherever they live, under whatever political system, they look at it with fresh, critical eyes, working out what’s good, what’s bad, what could be changed for the better? They arethe future: it’s theirs to mould and create, and they want to learn how – and we should want them to learn! Dystopian fiction is a forum for socio-political argument. It takes elements of the world we live in and holds them up to the light.

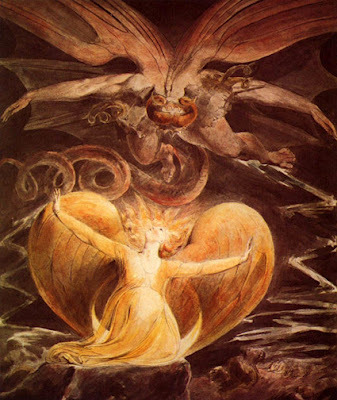

Thus, Scott Westerfield’s ‘Uglies’ and its sequels question the cult of beauty, the pressure to conform to unrealistically high standards, asking: What if everyone underwent plastic surgery as soon as they were sixteen or so, as a sort of initiation into adulthood? That’s obviously not happening around us, is it? Oh – wait a minute… Or what about reality shows and media violence? Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games examines a world in which the government runs gladiatorial shows in which people are actually killed. We know this is not impossible. It happened in the past, in ancient Rome. In some guise, could it happen again?

Thus, Scott Westerfield’s ‘Uglies’ and its sequels question the cult of beauty, the pressure to conform to unrealistically high standards, asking: What if everyone underwent plastic surgery as soon as they were sixteen or so, as a sort of initiation into adulthood? That’s obviously not happening around us, is it? Oh – wait a minute… Or what about reality shows and media violence? Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games examines a world in which the government runs gladiatorial shows in which people are actually killed. We know this is not impossible. It happened in the past, in ancient Rome. In some guise, could it happen again? No wonder dystopian fiction is so popular: it deals with real-world, often highly politicized questions: How much power should a government have to rule the lives of its people? What will happen when the oil runs out/the seas rise/the world warms or freezes? How would you cope with a terrorist attack/nuclear war/a global pandemic? Would you be emotionally strong enough? Could you survive? Dystopian fiction imaginatively represents the individual challenges, perhaps reminding the reader of comforts and conveniences we take for granted. (How would you wash your hair? Keep dry? Light a fire? Purify drinking water? Could you personally kill an animal for food?) In Jo Treggiari’s ‘Ashes, Ashes’, set amid the ruins of New York, something as small as a untied or broken shoelace can be a minor disaster, threatening your mobility and perhaps your survival. What does the future hold for us? What about the political issues in daily discussion around us: devolution, independence, immigration, religious intolerance, the freedom of the citizen versus the power of the state? Where will the internet society take us next? What about virtual realities, online lives: what roles will these things play? Will we retain our humanity? And what is it, anyway, to be human?

Most dyslit protagonists are young, passionate characters caught up in the mesh of their own problematic society and starting to ask these essential, awkward questions. The problems they face include numerous moral challenges. When survival is the key, should they selfishly look after themselves - or help someone else? Do they have the strength, the moral fibre to stand up and say 'this is wrong', when society declares it to be normal and right?

Though some people regard dystopian fiction as very dark - and it can be - it can also be inspiring, because it celebrates courage and hope, self reliance and compassion, the ability to look with a critical eye at the world we inhabit, and the desire to make that world a better place.

In no particular order - and in no way intended as a comprehensive list! - here are some titles I've enjoyed, a mixture of adult and childrens' fiction, old and new, obvious and less obvious. Please add your own recommendations in the comments!

Aldous Huxley – Brave New WorldGeorge Orwell – 1984 Margaret Atwood – The Handmaid’s TaleWilliam Golding – Lord of the Flies

John Wyndham – The Kraken Wakes, The Day of the Triffids, The Chrysalids

Peter Dickinson – The Changes Trilogy (even though the collapse of mechanized society in these books eventually turns out to have a supernatural cause, the workings-out of the changed Britain are practical and striking.)

Robert O’Brien – Z for ZachariahPatrick Ness – Monsters of MenJulie Bertagna – ExodusPaolo Bacigalupi – Ship BreakerJo Treggiari – Ashes, AshesMelvin Burgess – BloodtideMalorie Blackman – Noughts and CrossesScott Westerfield – UgliesBR Collins – Gamerunner

Published on April 14, 2013 01:22

April 5, 2013

More on heroines and heroism in fiction

Among the many thought-provoking comments to last week's post on the 'quieter' fairytale heroines (thankyou all!), is this, from the children's author Lily Hyde:

"I was talking about this with a friend, who said she hated fairytales as a little girl because she was so aware that the girls in them never had any fun - she wanted to be the one riding off on a horse to adventures but felt that to do so she would have to become a boy ... It made me wonder if being kick-ass is actually not about empowerment as such, it's about fun. The fairytale heroines you describe in your post are strong and determined and successful but they are also responsible in a way that the male characters are not. ... Being responsible (by being clever or determined or 'good') is not seen as glamorous, is not showy, is not always fun."

I'm sure this is so - at least, Jo March seemed to agree. "It's bad enough to be a girl, anyway, when I like boy's games, and work, and manners," she cries near the beginning of 'Little Women', and within a chapter or two is stalking the stage as the gallant Rodrigo in their home productions:

"No gentlemen were admitted; so Jo played male parts to her heart's content, and took immense satisfaction in a pair of russet-leather boots given her by a friend, who knew a lady who knew an actor. These boots, an old foil, and a slashed doublet once used by an artist for some picture, were Jo's chief treasures, and appeared on all occasions", and Jo appears "in gorgeous array, with plumed cap, red cloak, chestnut lovelocks, a guitar, and the boots, of course."

When I was nine I never wore a dress or a skirt if I could help it, and certainly not if my best friend was around - we always wore shorts or trousers (then termed 'trews'). We were tomboys (or so we liked to think). Together with our brothers we made rafts out of oildrums and bits of wood and tried to sail them on the River Wharfe; we fought the boys in the playground and got told off; we went up on Ilkley Moor with another friend who had a pony; we hid in the wooden hut shelter by Ilkley Tarn and made ghost noises as old ladies went past. We looked for adventures, for fun.

We were also keen readers. We were trying to channel George.

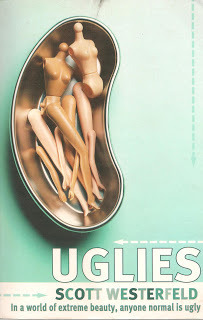

I assume you all know who George is, but just in case: George is the tomboy heroine of Enid Blyton's immensely popular 'Famous Five' series, which has never been out of print since 'Five On A Treasure Island' was published in 1942. Her real name is Georgina, but she refuses to answer to any name but 'George': she dresses like a boy and has cropped curly hair, she is 'as brave as a lion', never tells a lie, and is also, enviably, the owner of faithful Timmy, the gang's devoted dog. By strangers (especially stuffy new tutors and shady criminal types) she is generally mistaken for a boy, a mistake she takes as a compliment.

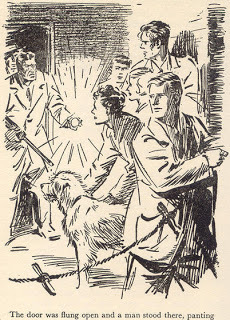

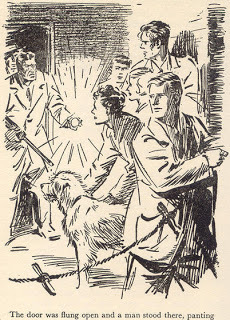

Even more than Jo March, George was a great relief to my generation. She was usually in the forefront of the action, even in the illustrations, thus:

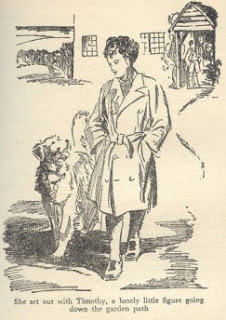

If there was a secret tunnel to be crawled down, or a midnight mission to embark upon, George would be there, with Timmy at her side always ready to have the essential scrawled message pinned to his collar: Trapped on Mystery Marsh. The maths tutor is a spy. The submarine will surface at midnight. Call Scotland Yard! George was fiery. She had a temper and she used it. She got into trouble for being rude: yet her instincts were always right. While Julian, Dick and Anne would shake their heads over the tea-table, George, banished to her room, would be spotting the mystery lights winking from the moor. Who would not want to be like her? - especially when the alternative looked like this:

This soppy girlie is Anne, mistaking a train for a volcano.

"I'm as good as a boy, any day!" was George's defiant cry: and so she was. But why did she have to dress as a boy to prove it?

It was because girls needed so badly to read about adventurous heroines, and for some reason most of the adults writing for them were unable to imagine the possibility that one could have adventures in a skirt. The sort of fun I enjoyed as a child - the pony-riding, the moorland walks, the raft-building, the make-belief - none of it was truly gendered: yet my friend and I felt it was: this was why we claimed the 'tomboy' label. The default assumption presented to us in the fiction we read was that women and girls did not have adventures; were hangers-on in history; led quiet, boring lives. You would imagine no woman ever stepped out of doors without a parasol.

This attitude has changed, but only gradually, and we're still not quite there. During my childhood in the 1960's - not so very long ago really - it had barely begun to shift. You have only to look at the school stories packaged separately, as they were: 'The Bumper Book for Boys', 'The Bumper Book for Girls'. The boys would get tales of historical derring-do, swordfights, brawls, sea-stories, war stories, plus practical tips on collecting hawk-moth caterpillars, how to make a compass with a cork, a magnet, a needle and saucer of water, and how to find your way in a forest by observing the moss on the north sides of trees. The girls' books would involve tales about flower fairies, the Girl Guides and Brownies, rivalries at hockey, lacrosse, and the ballet, how to make a Welsh rarebit, crochet a pretty mat for the table, and fold linen napkins into waterlilies or swans.

No wonder we wanted to be boys. No wonder we wanted to be George. And since boys also read 'The Famous Five' - in droves - George was our ambassador: incontrovertible if fictional proof that girls could have adventures too.

In spite of obvious real-life historical examples such as Grace Darling, Flora Macdonald, Florence Nightingale, and Mary Kingsley (who whacked crocodiles on the head with her canoe paddle and extolled 'the blessings of a good thick skirt' when travelling in Africa), writers stuffed their female leads into breeches if they were to do anything exciting. Geoffrey Trease, in his popular and well-written historical adventure stories for boys and girls, nearly always provided a cross-dressing heroine. There's 'Kit Kirkstone' aka Katherine Russell, in 'Cue For Treason', who runs away from an arranged marriage, falls in with a group of players, plays Shakespeare's Juliet, and ends up helping to foil a plot to kill Queen Elizabeth I. There's Angela D'Asola in 'The Hills of Varna' - a young Venetian scholar who - disguised as a boy - assists in the rescue of a priceless Greek manuscript from destruction at the hands of barbarous and ignorant monks. I loved these stories - they are still very readable - but along with Enid Blyton's George, they fostered in my childish mind the subconscious belief that to be adventurous or lead an interesting life, girls had to resemble boys. Which suggested girls per se were still somehow inferior.

I was interested to read the author's notes at the back of my copy of 'The Hills of Varna'. Trease claims his characters

... are no stranger than the real people who lived in the Italian Renaissance. One has only to think of girls like Marietta Strozzi, who broke away from her guardians at the age of eighteen, lived by herself in Florence, and had snowball matches by moonlight with the young gentlemen of that city; and Olympia Morata, who was lecturing on philosophy at Ferrara when she was sixteen.

Stirring stuff! I looked them up. And if the truth is not quite as romantic as Trease makes it sound, it's more complex and in some ways more interesting. Here is Marietta Strozzi, in a bust by Desiderio da Settignano: a cool and self-possessed young lady who was said to be the greatest beauty of Florence.

Despite the snowball fight (not a spontaneous street-corner affair between a gamine and a group of boys, but a piece of elaborate pageantry with political undercurrents) her life was bounded by the necessity to marry, and the limitations of being fatherless and "therefore" probably "stained". The young man who wished to marry her was dissuaded from doing so.

As for Olympia Morata, whose picture is here, it's true she was a remarkable woman. Her father was tutor to the dukes of Ferrara. Aged about twelve or thirteen,

already fluent in Greek and Latin, she became the friend and companion of the the young princess Anna D'Este. The court held protestant sympathies, and by sixteen Olympia was lecturing on Cicero and Calvin, writing and translating. In her early twenties she married a German Protestant who had come to Ferrara to study medicine. The young couple moved to Schweinfurt in Germany to evade the Inquisition, but were caught in the middle of war. Schweinfurt was occupied by the soldiers of the resplendently-named Albrecht Alcibiades, Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach: and Olympia and her husband lived in dangerous conditions, at one point taking refuge in a wine cellar. Ultimately, the city was sacked and burned. In a letter to her friend Cherubina Orsini, written at Heidelberg on August 8, 1554, Morata describes her difficult escape from Schweinfurt:

Vorrei che aveste visto come io era scapigliata, coperta di straccie, ché ci tolsero le veste d'attorno, e fuggendo io perdetti le scarpe, né aveva calze in piede, sì che mi bisognava fuggire sopra le pietre e sassi, che io non so come arrivasse.

I wish you had seen how dishevelled I was, dressed in rags, because they had taken away our clothes, and in fleeing I lost my shoes and nor had I socks on my feet, so I had to flee over the stones and the rocks - I do not know how I made it.

(Translation courtesy of Michelle Lovric.)

This is exciting by anyone's standards, considerably more of an adventure than most of us would wish to experience. Sadly, Olympia had not much longer to live. Shortly after arriving in Heidelberg,she began once again tutoring students in Greek and Latin, but a fever that she had caught in Schweinfurt never really subsided, and a few months later she died. She was not quite 29 years old: an early death, but not unusual for that place and time.

My point, though, is that here are two sixteenth century women who lived colourful, adventurous and energetic lives. Neither of them had to dress up in boys' clothes to do it. Yet their experiences and those of other women like them have been ignored or discounted down the centuries. Why? Because they are assumed to have been passive. Yet I doubt if Olympia Morata felt very passive while she was escaping barefoot, or Mary Kingsley while cracking the crocodile over the head. I'm willing to bet Olympia's life experiences were more dangerous and more 'exciting' than that of the Margrave Albrecht Alcibiades. Adventures are rarely very much fun for those who are in them. And, to return to Jo March with her beloved russet boots and old foil - was riding off on a horse to the wars ever really that much fun for the boys who had to do it?

Maybe we should look closer at our heroes as well as our heroines, and consider why the ability to fight is still so important to us that we tend - in fiction at least - to undervalue other forms of courage?

"I was talking about this with a friend, who said she hated fairytales as a little girl because she was so aware that the girls in them never had any fun - she wanted to be the one riding off on a horse to adventures but felt that to do so she would have to become a boy ... It made me wonder if being kick-ass is actually not about empowerment as such, it's about fun. The fairytale heroines you describe in your post are strong and determined and successful but they are also responsible in a way that the male characters are not. ... Being responsible (by being clever or determined or 'good') is not seen as glamorous, is not showy, is not always fun."

I'm sure this is so - at least, Jo March seemed to agree. "It's bad enough to be a girl, anyway, when I like boy's games, and work, and manners," she cries near the beginning of 'Little Women', and within a chapter or two is stalking the stage as the gallant Rodrigo in their home productions:

"No gentlemen were admitted; so Jo played male parts to her heart's content, and took immense satisfaction in a pair of russet-leather boots given her by a friend, who knew a lady who knew an actor. These boots, an old foil, and a slashed doublet once used by an artist for some picture, were Jo's chief treasures, and appeared on all occasions", and Jo appears "in gorgeous array, with plumed cap, red cloak, chestnut lovelocks, a guitar, and the boots, of course."

When I was nine I never wore a dress or a skirt if I could help it, and certainly not if my best friend was around - we always wore shorts or trousers (then termed 'trews'). We were tomboys (or so we liked to think). Together with our brothers we made rafts out of oildrums and bits of wood and tried to sail them on the River Wharfe; we fought the boys in the playground and got told off; we went up on Ilkley Moor with another friend who had a pony; we hid in the wooden hut shelter by Ilkley Tarn and made ghost noises as old ladies went past. We looked for adventures, for fun.

We were also keen readers. We were trying to channel George.

I assume you all know who George is, but just in case: George is the tomboy heroine of Enid Blyton's immensely popular 'Famous Five' series, which has never been out of print since 'Five On A Treasure Island' was published in 1942. Her real name is Georgina, but she refuses to answer to any name but 'George': she dresses like a boy and has cropped curly hair, she is 'as brave as a lion', never tells a lie, and is also, enviably, the owner of faithful Timmy, the gang's devoted dog. By strangers (especially stuffy new tutors and shady criminal types) she is generally mistaken for a boy, a mistake she takes as a compliment.

Even more than Jo March, George was a great relief to my generation. She was usually in the forefront of the action, even in the illustrations, thus:

If there was a secret tunnel to be crawled down, or a midnight mission to embark upon, George would be there, with Timmy at her side always ready to have the essential scrawled message pinned to his collar: Trapped on Mystery Marsh. The maths tutor is a spy. The submarine will surface at midnight. Call Scotland Yard! George was fiery. She had a temper and she used it. She got into trouble for being rude: yet her instincts were always right. While Julian, Dick and Anne would shake their heads over the tea-table, George, banished to her room, would be spotting the mystery lights winking from the moor. Who would not want to be like her? - especially when the alternative looked like this:

This soppy girlie is Anne, mistaking a train for a volcano.

"I'm as good as a boy, any day!" was George's defiant cry: and so she was. But why did she have to dress as a boy to prove it?

It was because girls needed so badly to read about adventurous heroines, and for some reason most of the adults writing for them were unable to imagine the possibility that one could have adventures in a skirt. The sort of fun I enjoyed as a child - the pony-riding, the moorland walks, the raft-building, the make-belief - none of it was truly gendered: yet my friend and I felt it was: this was why we claimed the 'tomboy' label. The default assumption presented to us in the fiction we read was that women and girls did not have adventures; were hangers-on in history; led quiet, boring lives. You would imagine no woman ever stepped out of doors without a parasol.

This attitude has changed, but only gradually, and we're still not quite there. During my childhood in the 1960's - not so very long ago really - it had barely begun to shift. You have only to look at the school stories packaged separately, as they were: 'The Bumper Book for Boys', 'The Bumper Book for Girls'. The boys would get tales of historical derring-do, swordfights, brawls, sea-stories, war stories, plus practical tips on collecting hawk-moth caterpillars, how to make a compass with a cork, a magnet, a needle and saucer of water, and how to find your way in a forest by observing the moss on the north sides of trees. The girls' books would involve tales about flower fairies, the Girl Guides and Brownies, rivalries at hockey, lacrosse, and the ballet, how to make a Welsh rarebit, crochet a pretty mat for the table, and fold linen napkins into waterlilies or swans.

No wonder we wanted to be boys. No wonder we wanted to be George. And since boys also read 'The Famous Five' - in droves - George was our ambassador: incontrovertible if fictional proof that girls could have adventures too.

In spite of obvious real-life historical examples such as Grace Darling, Flora Macdonald, Florence Nightingale, and Mary Kingsley (who whacked crocodiles on the head with her canoe paddle and extolled 'the blessings of a good thick skirt' when travelling in Africa), writers stuffed their female leads into breeches if they were to do anything exciting. Geoffrey Trease, in his popular and well-written historical adventure stories for boys and girls, nearly always provided a cross-dressing heroine. There's 'Kit Kirkstone' aka Katherine Russell, in 'Cue For Treason', who runs away from an arranged marriage, falls in with a group of players, plays Shakespeare's Juliet, and ends up helping to foil a plot to kill Queen Elizabeth I. There's Angela D'Asola in 'The Hills of Varna' - a young Venetian scholar who - disguised as a boy - assists in the rescue of a priceless Greek manuscript from destruction at the hands of barbarous and ignorant monks. I loved these stories - they are still very readable - but along with Enid Blyton's George, they fostered in my childish mind the subconscious belief that to be adventurous or lead an interesting life, girls had to resemble boys. Which suggested girls per se were still somehow inferior.

I was interested to read the author's notes at the back of my copy of 'The Hills of Varna'. Trease claims his characters

... are no stranger than the real people who lived in the Italian Renaissance. One has only to think of girls like Marietta Strozzi, who broke away from her guardians at the age of eighteen, lived by herself in Florence, and had snowball matches by moonlight with the young gentlemen of that city; and Olympia Morata, who was lecturing on philosophy at Ferrara when she was sixteen.

Stirring stuff! I looked them up. And if the truth is not quite as romantic as Trease makes it sound, it's more complex and in some ways more interesting. Here is Marietta Strozzi, in a bust by Desiderio da Settignano: a cool and self-possessed young lady who was said to be the greatest beauty of Florence.

Despite the snowball fight (not a spontaneous street-corner affair between a gamine and a group of boys, but a piece of elaborate pageantry with political undercurrents) her life was bounded by the necessity to marry, and the limitations of being fatherless and "therefore" probably "stained". The young man who wished to marry her was dissuaded from doing so.

As for Olympia Morata, whose picture is here, it's true she was a remarkable woman. Her father was tutor to the dukes of Ferrara. Aged about twelve or thirteen,

already fluent in Greek and Latin, she became the friend and companion of the the young princess Anna D'Este. The court held protestant sympathies, and by sixteen Olympia was lecturing on Cicero and Calvin, writing and translating. In her early twenties she married a German Protestant who had come to Ferrara to study medicine. The young couple moved to Schweinfurt in Germany to evade the Inquisition, but were caught in the middle of war. Schweinfurt was occupied by the soldiers of the resplendently-named Albrecht Alcibiades, Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach: and Olympia and her husband lived in dangerous conditions, at one point taking refuge in a wine cellar. Ultimately, the city was sacked and burned. In a letter to her friend Cherubina Orsini, written at Heidelberg on August 8, 1554, Morata describes her difficult escape from Schweinfurt:

Vorrei che aveste visto come io era scapigliata, coperta di straccie, ché ci tolsero le veste d'attorno, e fuggendo io perdetti le scarpe, né aveva calze in piede, sì che mi bisognava fuggire sopra le pietre e sassi, che io non so come arrivasse.

I wish you had seen how dishevelled I was, dressed in rags, because they had taken away our clothes, and in fleeing I lost my shoes and nor had I socks on my feet, so I had to flee over the stones and the rocks - I do not know how I made it.

(Translation courtesy of Michelle Lovric.)

This is exciting by anyone's standards, considerably more of an adventure than most of us would wish to experience. Sadly, Olympia had not much longer to live. Shortly after arriving in Heidelberg,she began once again tutoring students in Greek and Latin, but a fever that she had caught in Schweinfurt never really subsided, and a few months later she died. She was not quite 29 years old: an early death, but not unusual for that place and time.

My point, though, is that here are two sixteenth century women who lived colourful, adventurous and energetic lives. Neither of them had to dress up in boys' clothes to do it. Yet their experiences and those of other women like them have been ignored or discounted down the centuries. Why? Because they are assumed to have been passive. Yet I doubt if Olympia Morata felt very passive while she was escaping barefoot, or Mary Kingsley while cracking the crocodile over the head. I'm willing to bet Olympia's life experiences were more dangerous and more 'exciting' than that of the Margrave Albrecht Alcibiades. Adventures are rarely very much fun for those who are in them. And, to return to Jo March with her beloved russet boots and old foil - was riding off on a horse to the wars ever really that much fun for the boys who had to do it?

Maybe we should look closer at our heroes as well as our heroines, and consider why the ability to fight is still so important to us that we tend - in fiction at least - to undervalue other forms of courage?

Published on April 05, 2013 01:00

March 29, 2013

Fairytale princesses: tougher than you think

Fairytale princesses are still frequently written off as insipid, passive, and generally terrible role models for girls and young women. And while it’s easy enough to find counter examples of bold and brave fairytale heroines (The Master Maid, Mollie Whuppie, the girl in The Black Bull of Norroway) these do tend to be less well known, or at least nothing like as well known as the classics, the famous tales, the ones Disney picked: The Sleeping Beauty, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Cinderella, Beauty and the Beast.

In fact I don't happen to believe that it's the business either of literature in general, or of fairytales in particular, to provide role models. (The business of literature is to tell stories about people, who may or may not be admirable.) But even if it were, is the ‘insipid’ image really deserved? While it’s true that the Sleeping Beauty hasn’t much to do except await ‘true love’s kiss’, I don’t believe this is what makes the story so memorable – as I’ve said here – and I was pleased to discover Ursula K LeGuin saying much the same thing in a fine essay, ‘Wilderness Within’, in her collection ‘Cheek By Jowl’: she quotes a short, haunting poem by Sylvia Townsend Warner:

The Sleeping Beauty woke: The spit began to turn, The woodmen cleared the brake, The gardener mowed the lawn. Woe’s me! And must one kiss Revoke the silent house, the birdsong wilderness?

For LeGuin, as for me: “the story is about that still centre: ‘the silent house, the birdsong wilderness’.”

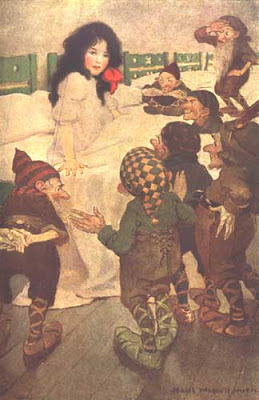

As for the heroines of the other tales, they are all pretty active. Abandoned in the forest, Snow White doesn’t lie down and die like the ‘Babes in the Wood’ but keeps going till she finds the house of the seven dwarfs, where she pays her way by working:

The dwarfs said, “Will you attend to our housekeeping for us? Cook, make beds, wash, sew and knit? If you like to do all this for us, and keep everything in order for us, you may stay and shall want for nothing.” “With all my heart,” said the child. So she stayed, keeping everything in excellent order. The dwarfs went every day to the mountains, to find copper and gold, and came home in the evening, and then their supper had to be ready.

The dwarfs said, “Will you attend to our housekeeping for us? Cook, make beds, wash, sew and knit? If you like to do all this for us, and keep everything in order for us, you may stay and shall want for nothing.” “With all my heart,” said the child. So she stayed, keeping everything in excellent order. The dwarfs went every day to the mountains, to find copper and gold, and came home in the evening, and then their supper had to be ready.I can’t see anything wrong or unworthy about this bargain. Both sides get something out of it, both are satisfied.

Cinderella is another hard worker: grieving too, for her mother’s death: in the Grimm's version, 'Aschenputtel', the version I read as a child, there is no fairy godmother, no rats turned into coachmen, no pumpkin. Cinderella makes her own magic. In a motif similar to that of ‘Beauty and the Beast’, she asks her father to bring her not beautiful clothes, pearls and jewels – as her stepsisters do – but ‘the first branch which knocks against your hat on the way home’. This turns out to be a hazel twig which Cinderella plants on her mother’s grave and waters with her tears, and:

A little white bird always came on the tree, and if Cinderella expressed a wish, the bird threw down to her what she had wished for.

When her stepmother throws peas and lentils into the ashes for her to pick out, Cinderella calls the birds:

“You tame pigeons, you turtle doves and all you birds beneath the sky, come and help me to pick The good into the pot The bad into the crop.”

And when the stepmother and sisters have sped away to the prince’s wedding, she goes to her mother’s grave and calls, “Shiver and quiver, little tree,Silver and gold throw down on me.” Then the bird threw a gold and silver dress down to her, and slippers embroidered with silk and silver.

And so on, for the next three nights. It’s clear that Cinderella stage-manages the whole affair:

When evening came she wished to leave, and the King’s son followed her and wanted to see into which house she went. But she sprang away from him and into the garden behind the house. There stood a beautiful pear tree… She clambered so nimbly between the branches that the King’s son did not know where she had gone. He waited until her father came and said to him, “The unknown maiden has escaped from me and I believe she has climbed up the pear-tree. The father thought, “Can it be Cinderella?” and had an axe brought, and cut the tree down, but no one was in it. And when they got into the kitchen, Cinderella lay there among the ashes, for she had jumped down on the other side of the tree, had taken the beautiful dress to the bird on the hazel tree, and put on her old grey gown.

This is a girl with her own mind and her own agenda. She is a tough cookie, a girl who makes things happen. Although the tale of ‘Cinderella’ is often regarded as the archetypical ‘rags to riches’ story, it’s not, really. A girl who can get whatever she wishes from a magical hazel tree is not ‘poor’. In the course of the story, she gets her own back on nearly everyone. Her father loses his pigeon house and pear tree (chopped to pieces); the stepsisters lose toes, heels and eventually their eyes, and the prince has to (a) delay his gratification and (b) put a good deal of effort into trying to find the mysterious girl he has lost his heart to.

Beauty, in ‘Beauty and the Beast’ is a similarly strong-minded young woman. The original tale by 18th century Madame de Villeneuve probably protested forced marriages - as Terri Windling puts it in another excellent essay: "...Animal Bridegroom stories, in particular, embodied the real–life fears of women who could be promised to total strangers in marriage, and who did not know if they'd find a beast or a lover in their marriage bed." (Beauty and the Beast", Terri Windling, Endicott Studio) And the modern, Freudian interpretation is scarcely any different, declaring the fairytale a parable about virginal female fears (Beauty regards male sexuality as brutish and bestial, before coming to womanhood and embracing it).

Here's a slightly different take: When her father loses all his money, Beauty rolls up her sleeves. She works. She’s physically brave, insisting on saving her father’s life by going to live with the Beast. She’s got moral courage too: when the Beast asks, as he constantly does,

“Beauty, will you be my wife?”

she refuses, because even as she grows more and more fond of him, she is not ready to say yes.

Why aren’t we all cheering? If this is a parable about sex, it’s less about fear of sex – in most of the modern versions, Beauty loses her fear of the Beast months before the end of the story – than it is about resisting pressure, about taking the time to know your own mind. At last - she leaves it rather late, but that’s narrative tension for you – Beauty realises that this ugly Beast is someone she truly loves. She doesn't even know he's a prince until after she's committed to him.

Finally, the whole ‘poor role model’ criticism is odder than you might think. Is there any real danger that a little girl (this sort of angst is always about girls) might read these fairytales and come away from them not with the message that you need hard work, faithfulness, determination and courage to succeed - but that you can loll around wearing pink satin until a prince comes to carry you away? I find that bizarre. Mainly, the princes in fairy stories are symbols of success. How else can the tale convey it? There aren’t that many job descriptions in the castle-studded, anonymous fairytale Wald. Cinderella, Beauty and Snow White can't become tax lawyers or doctors or bankers or members of Parliament, any more than, in 'The Lord of the Rings', Aragorn can blast the Black Riders with a well directed burst of fire from a semi-automatic. Such things simply do not exist in their worlds.

On top of that, isn't it significant that the same disapproval and disquiet is never levelled at the many male characters in fairy stories who marry princesses? The Brave Little Tailor, the soldier in 'The Blue Light', the soldier in 'The Twelve Dancing Princesses', the boy with the Golden Goose – no one seems to have any trouble recognising, in their tales, a royal marriage as a symbol of well-deserved worldly success.

Who would have thought to find the double standard applied even to fairytales? What's sauce for the gander ought to be sauce for the goose.

Picture credits:

Cinderella, Walter CraneSnow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Jessie Willcox SmithBeauty and the Beast, Eleanor Vere Boyle

Published on March 29, 2013 01:56

March 22, 2013

Folklore snippets: The wild white cattle of the Hidden Folk

Wild white cattle at Chillingham, Northumberland

Wild white cattle at Chillingham, NorthumberlandIn Scandinavia the hidden folk, or huldrefolk, are the elves, trolls and other supernatural peoples who live in the mountains, forests and under mounds. They're not always hidden, as the following story shows, and it's interesting that their cattle are, as fairy cattle so often are, described as white or light in colour.

The Huldres in Norwayfrom Scandinavian Folklore, ed William Craigie 1896

The huldres are women as beautiful as can be imagined, who live in the mountains and graze their cattle there. These are often fat and thriving, brindled or light in colour. They themselves, when they appear to men, are dressed in grey clothes, with a white cloth hanging over their face, and the only thing they can be recognised by, is the long tail that drags behind them, which however they for the most past manage to conceal.

White, with red ears

White, with red earsIf one hears them play among the mountains, it is so enchanting that one can hardly contain oneself for joy. This music is called the Huldre’s tune, and there are many peasants who have heard it and learned it, and can play it again.

One time a huldre was present at a gathering, where everyone wanted to dance with the pretty stranger, but in the midst of the merriment the young fellow who was dancing with her caught sight of her long tail. He immediately guessed what she was, and was frightened, but kept his presence of mind and did not betray her, but only said at the end of the dance, “Pretty maid, you are losing your garter.” She immediately disappeared, but afterwards rewarded him wit fine presents and success in his cattle-rearing.

Now, the herd of wild white cattle in Chillingham Park in Northumberland is thought to have been there for at least 700 years, and is supposedly descended from the extinct European aurochs: they cattle are "small, with upright horns in both males and females. They are white with coloured ears. In the case of Chillingham Cattle, the ear-colour is red."

In the great Irish cycle The Cattle Raid of Cooley,

the Morrigan daughter of Aed Ernmas came from the fairy dwellings to destroy Cuchulain. For she had threatened on the Cattle-raid of Regomaina that she would come to undo Cuchulain what time he would be in sore distress when engaged in battle and combat with a goodly warrior, with Loch, in the course of the Cattle-spoil of Cualnge. Thither then the Morrigan came in the shape of a white, hornless, red-eared heifer, with fifty heifers about her and a chain of silvered bronze between each two of the heifers.

(Trans Joseph Dunn, 1914: and for anyone interested, here, on a cattle breeder's website, are links to lots of references from Irish legend to white cattle with red ears.)

White with red ears is the colour of fairy hounds, too, so I wonder if the white fairy cows of the Hidden People are a memory of the non-domesticated wild cattle of the past?

Picture credits:

The Chillingham herd: Photographer: C. Michael Hogan, Wikimedia CommonsWhite with red ears: from geograph.org.uk, author Stuart Wallace, Wikimedia Commons

Published on March 22, 2013 02:43

March 15, 2013

Desiring Dragons

Desiring Dragons is the theme of Terri Windling’s latest Movable Feast. The title of the Feast comes from J.R.R. Tolkien. “I desired dragons with a profound desire," he wrote regarding his life-long taste for myth and tales of magic. "Of course, I in my timid body did not wish to have them in the neighborhood. But the world that contained even the imagination of Fáfnir was richer and more beautiful, at whatever the cost of peril.”

So this post is my response to Terri’s enquiry: “Why are we drawn to stories and other art forms (both contemporary and historic) with their roots dug deep into the soil of myth?”

Okay. Three quotations:

Into my heart that killsFrom yon far country blows:What are those blue remembered hills?What spires, what farms are those?

AE Housman, A Shropshire Lad

We are the Pilgrims, master, we shall goAlways a little further: it may beBeyond the last blue mountain barred with snow,Across that angry or that glimmering sea,White on a throne or guarded in a caveThere lives a prophet who can understandWhy men were born…

James Elroy Flecker, Epilogue, The Golden Journey to Samarkand

The parents had already retired to rest; the old clock ticked monotonously from the wall, the windows rattled with the whistling wind, and the chamber was dimly lighted by the flickering light of the moon. The young man lay restless on his bed, thinking of the stranger and his tales. ‘It is not the treasures,’ said he to himself, ‘that have awakened in me such unutterable longings… But I long to behold the blue flower.’

Novalis, Henry of Ofterdingen: A Romance

We pass through this world. We’re the only animal which understands that it must die, that its time here is transient. And so we are surrounded at all times and in all places by mysteries. There is the past, which we remember but can no longer touch or affect: a magician’s backward-facing glass in which the dead are still alive and the old are still young and can be seeing going about their affairs, ignorant of our gaze, in tiny bright pictures with the sound turned down low.

There is the distance, that blue trembling elsewhere on the rim of the horizon, beyond which – perhaps – everything is different, new and wonderful.

And there is the invisible future into which we constantly travel with our baggage of hopes and promises and longings and fears.

We’re surrounded by things which are not, which have no physical existence. Living in such a world, it’s hardly surprising that we’re drawn to stories of mythical significance. It’s been the aim of humans down the millennia to try to explain the world and our existence in it. Science itself springs from this desire. And the paradoxical, untouchable reality of such important things (the past: the future: the horizon) have surely taught us confidence to imagine and discover and delight in other things which can also neither be seen nor approached nor touched. The soul, the human spirit. Gods, ghosts. Right and wrong. Philosophy. Mathematics.

I don't wish to say that all ideas are equal, just that they spring from the same ‘soil of myth’ Terri speaks of: the soil from which all human ideas spring. What Tolkien called sub-creation doesn’t only apply to story-tellers and artists. The Ptolemaic universe, with the sun at its centre, looks like a fantasy world today, but was believed for centuries to be an accurate description of what was really out there. And indeed it was: it made a great deal of sense given the information then available, until Copernicus and Galileo and Newton came up with new and better descriptions, and then again Einstein: and now we have string theory and branes and multiple dimensions and bubble universes, and cosmologists are continually suggesting new or refined versions. This too is sub-creation.

I long to know what lies beyond the boundaries of my five senses. I want to know what the bee sees in the ultraviolet. I want to know what it’s like to hear like a bat or a dolphin. I want to know what’s underneath the frozen seas of Europa, and if anything lives on Mars or on some planet circling Procyon or Alpha Centauri. I want to visit Petra, that rose red city half as old as time; I want to cross the horizon. I want to know what really happened long ago at Stonehenge and Avebury and Carnac. I want to find out what the Druids really believed. And in the meantime, yes - I want to read about the golden dragons in the paradisal gardens at the end of the world because such stories are celebrations and extensions of the magic and the miracle of ‘this precious only endless world in which we think we live’. I'll let Robert Graves tell you the rest:

Join the Movable Feast and find more on 'Desiring Dragons' by following this link to Terri's blog - Myth and Moor: Moveable Feasts

Picture credit:

One of the dragons from The Nine Dragons handscroll (九龙图/九龍圖), painted by the Song-Dynasty Chinese artist Chen Rong (陈容/陳容) in 1244 CE. Ink and some red on paper. The entire scroll is 46.3 x 1096.4 cm. Located in the Museum of Fine Art - Boston, USA. Wikimedia Commons

Published on March 15, 2013 01:25

March 13, 2013

Inspiring Blogs!

Many thanks this morning to Jill London (at whose blog you will find a gorgeous film clip about the life of Tove Jansson) who has handed to Steel Thistles the Very Inspiring Blogger Award...

In order to claim it I have to tell you seven things about myself, but I think I'd rather tell you about seven inspirational books. And because I usually talk here about fiction - and fantasy fiction at that - I think I'll break the rule and talk about non-fiction books which have inspired me. In no particular order:

1: Gods and Myths of Northern Europe by HR Ellis Davidson.Penguin, 1964. I've had this book for ever, it's about the best scholarly introduction to the study of Norse mythology that you'll ever find, and I recommend all her other books too.

2: Parallel Worlds by Michio Kaku, Allen Lane, 2005. Fascinating and readable exploration of alternative universes and our place in the cosmos by a physicist who's also a big fan of science fiction!

3: The Mind in the Cave by David Lewis Williams, Thames & Hudson, 2002. Spine-tinglingly compelling book about what was really going on with prehistoric cave paintings.

4: Union Street by Charles Causley, Rupert Hart-Davis, 1957. Poems with a strong streak of the ballad in them, which I fell in love with at an early age.

5: Memories by Lucy M Boston, Oldknow Books, 1992. The memoirs of the wonderful author of the 'Green Knowe' children's books. She would spend each summer tending the garden of her 12th century manor house, and each winter writing a book and making a patchwork quilt. The ideal life!

6: Animals in Translation by Temple Grandin & Catherine Johnson, Bloomsbury 2005. High-functioning autistic Professor Temple Grandin's insights into the way animals think and perceive the world.

7: A History of God by Karen Armstrong, Ballantyne 1993. A history of the ways three major monotheistic religions have thought of God, and how we have shaped them and they us.

Right! Time for me to head back to work - but I'd like to pass on this Inspiring Blog Award (again in no particular order) to the following bloggers:

1: Esmeralda's Cumbrian History and Folklore

2: Windsongs and Wordhoards

3: Beneath the Bracken

4: In the Labyrinth

5: Writing in the House of Dreams

If you want to play, this is how: display the award logo on your blog. Link back to the person who nominated you. State 7 things about yourself (or 7 inspirational things: I've just changed the rules!) . Nominate other bloggers for this award if you choose and link to them (notifying those bloggers of the nomination). And that’s it .

Published on March 13, 2013 02:55

March 8, 2013

The Wild Hunt Rides Over Paris

Around about a year ago I spent a few days in Paris with my daughter: we stayed in Montmartre, which I didn't know very well in spite of having once lived in France for four years, close to Fontainebleau.

Around about a year ago I spent a few days in Paris with my daughter: we stayed in Montmartre, which I didn't know very well in spite of having once lived in France for four years, close to Fontainebleau.I unreservedly recommend Montmartre as a place to visit. Sure, there are rather a lot of sex shops at the foot of the hill and along the road of the Moulin Rouge; but up on the hill it still feels very much like the village it once was: home of artists and revolutionaries (most of whom wouldn't actually have minded the sex shops anyway.) High above Paris, the hill used to be covered with windmills and gypsum mines; it was occupied by the Russians when they invaded Paris in 1814: they used the hill as a base for the artillery bombardment of the city, and legend proclaims they here invented the first bistro - fast food - from the Russian word bystro, "quickly".

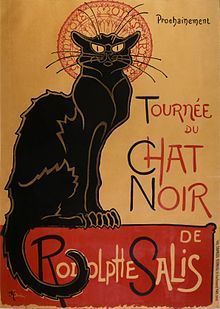

Be that as it may, history-soaked Montmartre was once the haunt of artists like Pisarro, Matisse, Van Gogh, Renoir, Degas, Utrillo, Valadon and Toulouse-Lautrec - and the home of cabarets like La Palette d'Or and Le Chat Noir, for which Théophile Steinlen designed the iconic poster.

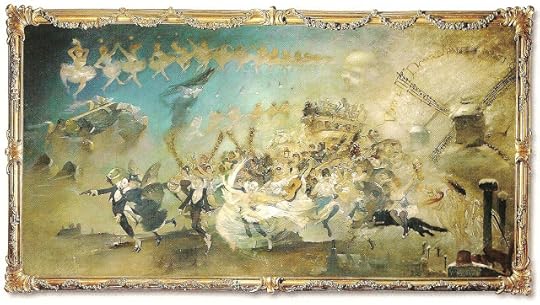

After walking up and down the steep little cobbled streets (there are still two old windmills to be seen) we ended up at the Musee de Montmartre, housed in what was once a 17th century abbey. Renoir lived there for a time, and painted the garden. As you'd expect, the museum has a lot of brilliant art and plenty of information about the history of Montmartre - but the thing I really couldn't take my eyes off was the painting that heads this post. Once I'd seen it, that was it. I could have stood and looked at it for hours.

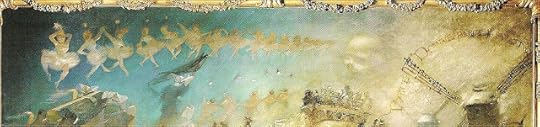

It's by Adolphe Willette, called Parce Domine - the opening words of a Catholic antiphon: Parce, Domine, parce populo tuo: ne in aeternum irascaris nobis (Spare, Lord, spare your people: be not angry with us forever). It's a massive canvas, taking up most of one wall: it's a nightscape over Paris: the smoky city stretches out at the very bottom of the frame, with the hill of Montmartre rising to the right. And streaming out across the sky, over the rooftops, as if they have just leapt out from the windmills of Montmartre, is a fantastic and macabre harlequinade of the beautiful and the damned.

It's led by a Pierrot-like character, a suicide with the gun still in his hand, embraced and semi-supported by a woman in black with black butterfly wings. She seems to be holding up his jaw. Her feet run trippingly on nothing: his are elegantly crossed: it is clear he would fall without her: yet he is the foremost of this troupe. Behind comes another Pierrot-type character, dapper in white shirtfront, white spats and buckled shoes, dancing, dancing; and behind him...

... behind him sweeps a whole frenzied crowd of men and women, swirling and leaping and brandishing guitars and tambourines, rapiers and antler-crowned standards, brooms and whips; in the background a horse-drawn omnibus sways and hurtles along like a chariot.

Their feet never touching the chimneys below, they stream out across the smoke-stained sky from the dark windmills (whose very vanes are staves of music) - a black cat (a Chat Noir) the size of a panther leaping across the canvas with a dancing girl sitting sideways on his back waving aloft what appears to be a swaddled baby (a dead child?), followed by a troop of naked and very young-looking girls - while a mortal cat, dark and solid on the snow-capped rooftop in the lower right hand corner, arches his back and spits at the ghostly throng. Above it all...

... eyeless Death himself looms in the shape of a ghostly cloud and we read the words of the desperate music ringing from the vanes of the moulins: Parce, Domine, parce populo tuo. Spare, Lord, spare your people.

If there's a better expression anywhere of the energy, gaiety, cruelty and poverty of late 19th century Paris, I don't know it. This is an amazing, amazing painting. Think of it, the next time you hear the can-can.

Published on March 08, 2013 01:00

February 28, 2013

'Bitter Greens' by Kate Forsyth

Kate Forsyth first appeared on this blog a couple of years ago when I reviewed her enchanting children's fantasy 'The Puzzle Ring'. Now her recent adult fantasy 'Bitter Greens' is about to be published in the UK. It's a fabulous mix of history, fantasy and fiction: suitably, as its heroine is a storyteller par excellence, the French writer Mademoiselle Charlotte-Rose de Caumont de la Force (1654-1724), best known as the author of the fairytale ‘Persinette’ (1698), which later was adapted by the Brothers Grimm as the famous ‘Rapunzel’. Born to Protestant parents, Mademoiselle de la Force found it too dangerous to retain that faith at the intolerant court of the Sun King, Louis XIV, who denied Protestants religious and political freedom and pursued policies of persection and forcible conversion.

Kate Forsyth first appeared on this blog a couple of years ago when I reviewed her enchanting children's fantasy 'The Puzzle Ring'. Now her recent adult fantasy 'Bitter Greens' is about to be published in the UK. It's a fabulous mix of history, fantasy and fiction: suitably, as its heroine is a storyteller par excellence, the French writer Mademoiselle Charlotte-Rose de Caumont de la Force (1654-1724), best known as the author of the fairytale ‘Persinette’ (1698), which later was adapted by the Brothers Grimm as the famous ‘Rapunzel’. Born to Protestant parents, Mademoiselle de la Force found it too dangerous to retain that faith at the intolerant court of the Sun King, Louis XIV, who denied Protestants religious and political freedom and pursued policies of persection and forcible conversion.She converted, therefore, but in 1697 her lively wit and romans à clef, along with a number of scandals and rumours, provoked the King to send her to the Benedictine abbey of Gercy-en-Brie, where she wrote her memoirs and a number of other novels.

Told in the first person, 'Bitter Greens' begins with Charlotte’s disgrace and journey to the abbey, where the nuns strip her of her elaborate court dress – so complicated in its fastenings she literally cannot undress herself – replacing it with a simple linen smock and shearing off her hair. Charlotte’s quick tongue and spirit get her into more trouble and she undergoes penances such as lying prostrate for hours on the cold stone floor of the chapel. In this misery, she finds a friend – an older nun, Soeur Seraphina, who takes her to work in the garden and begins telling her a story: the story of a young Venetian girl who was sold to a sorceress for a handful of bitter green herbs and shut up in a high tower…

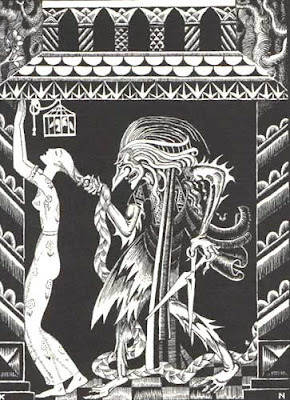

Rapunzel - Kay Nielsen

Rapunzel - Kay NielsenFrom this point on, the story of 'Bitter Greens' interweaves history, fiction and fantasy, complex as any braid of Rapunzel’s hair. There is Charlotte’s own personal history at the court of the Sun King. There is the tale of a Venetian courtesan and witch called Selena Leonelli, or La Strega Bella, who becomes the mistress of Titian and who prolongs her youth by drinking the blood of young virgins. And there is the tale of Marguerite, the child whom La Strega imprisons in the high tower.

Rich and magical as it is, this is frequently a very dark story (and the UK cover, though pretty, says fairytale in a way which suggests a much younger book: this is not in any way a novel for children, and the Australian cover, above, may be a better guide.) Kate Forsyth reminds us of the extreme powerlessness of most women – even those apparently most powerful and celebrated, the Queen herself, or the King’s mistresses, whose wealth and status depend entirely upon his favour. Charlotte-Rose’s mother is deprived of her chateau, freedom and family at the whim of the king. Servant women are raped against walls and left to get on with their work. Charlotte-Rose's talent and intelligence is no security: like any other lady she she must flirt and tease and scheme for a suitable marriage. And the streets – whether of 17th century Paris or 16th century Venice – are full of girls whose only livelihood is to sell themselves. It’s a world of casual brutality, revenge, desperation, plague and persecution. No wonder if there are dead babies and abandoned children. No wonder if some of the survivors turn to witchcraft.

Bitter Greens is a powerful tale about survival, and the endurance of hope, and the tales we tell ourselves to help us carry on. It’s fascinating that Charlotte-Rose wrote ‘Persinette’ while she herself was shut up in a convent: and in Kate Forsyth’s hands the tale of the child taken from her parents and shut up in a high tower has truly disturbing resonances, a reminder of some dreadful modern examples. Fairytales are not always pretty. Nevertheless, there is hope. Rapunzel escapes from her tower, and Charlotte-Rose did eventually return to Paris – where, Kate Forsyth tells us in the Afterword, she became a celebrated member of the salons and joined a secret society set up by the Duchesse de Maine called ‘The Order of the Honey Bee’ – whose thirty-nine members ‘wore a dark-red satin dress embroidered with silver bees and a wig shaped like a beehive.’ Now that is survival with style.

BITTER GREENS by Kate Forsyth, Allison & Busby (25 February 2013)

Published on February 28, 2013 01:53