More on heroines and heroism in fiction

Among the many thought-provoking comments to last week's post on the 'quieter' fairytale heroines (thankyou all!), is this, from the children's author Lily Hyde:

"I was talking about this with a friend, who said she hated fairytales as a little girl because she was so aware that the girls in them never had any fun - she wanted to be the one riding off on a horse to adventures but felt that to do so she would have to become a boy ... It made me wonder if being kick-ass is actually not about empowerment as such, it's about fun. The fairytale heroines you describe in your post are strong and determined and successful but they are also responsible in a way that the male characters are not. ... Being responsible (by being clever or determined or 'good') is not seen as glamorous, is not showy, is not always fun."

I'm sure this is so - at least, Jo March seemed to agree. "It's bad enough to be a girl, anyway, when I like boy's games, and work, and manners," she cries near the beginning of 'Little Women', and within a chapter or two is stalking the stage as the gallant Rodrigo in their home productions:

"No gentlemen were admitted; so Jo played male parts to her heart's content, and took immense satisfaction in a pair of russet-leather boots given her by a friend, who knew a lady who knew an actor. These boots, an old foil, and a slashed doublet once used by an artist for some picture, were Jo's chief treasures, and appeared on all occasions", and Jo appears "in gorgeous array, with plumed cap, red cloak, chestnut lovelocks, a guitar, and the boots, of course."

When I was nine I never wore a dress or a skirt if I could help it, and certainly not if my best friend was around - we always wore shorts or trousers (then termed 'trews'). We were tomboys (or so we liked to think). Together with our brothers we made rafts out of oildrums and bits of wood and tried to sail them on the River Wharfe; we fought the boys in the playground and got told off; we went up on Ilkley Moor with another friend who had a pony; we hid in the wooden hut shelter by Ilkley Tarn and made ghost noises as old ladies went past. We looked for adventures, for fun.

We were also keen readers. We were trying to channel George.

I assume you all know who George is, but just in case: George is the tomboy heroine of Enid Blyton's immensely popular 'Famous Five' series, which has never been out of print since 'Five On A Treasure Island' was published in 1942. Her real name is Georgina, but she refuses to answer to any name but 'George': she dresses like a boy and has cropped curly hair, she is 'as brave as a lion', never tells a lie, and is also, enviably, the owner of faithful Timmy, the gang's devoted dog. By strangers (especially stuffy new tutors and shady criminal types) she is generally mistaken for a boy, a mistake she takes as a compliment.

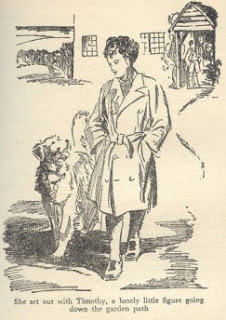

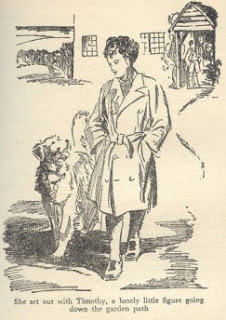

Even more than Jo March, George was a great relief to my generation. She was usually in the forefront of the action, even in the illustrations, thus:

If there was a secret tunnel to be crawled down, or a midnight mission to embark upon, George would be there, with Timmy at her side always ready to have the essential scrawled message pinned to his collar: Trapped on Mystery Marsh. The maths tutor is a spy. The submarine will surface at midnight. Call Scotland Yard! George was fiery. She had a temper and she used it. She got into trouble for being rude: yet her instincts were always right. While Julian, Dick and Anne would shake their heads over the tea-table, George, banished to her room, would be spotting the mystery lights winking from the moor. Who would not want to be like her? - especially when the alternative looked like this:

This soppy girlie is Anne, mistaking a train for a volcano.

"I'm as good as a boy, any day!" was George's defiant cry: and so she was. But why did she have to dress as a boy to prove it?

It was because girls needed so badly to read about adventurous heroines, and for some reason most of the adults writing for them were unable to imagine the possibility that one could have adventures in a skirt. The sort of fun I enjoyed as a child - the pony-riding, the moorland walks, the raft-building, the make-belief - none of it was truly gendered: yet my friend and I felt it was: this was why we claimed the 'tomboy' label. The default assumption presented to us in the fiction we read was that women and girls did not have adventures; were hangers-on in history; led quiet, boring lives. You would imagine no woman ever stepped out of doors without a parasol.

This attitude has changed, but only gradually, and we're still not quite there. During my childhood in the 1960's - not so very long ago really - it had barely begun to shift. You have only to look at the school stories packaged separately, as they were: 'The Bumper Book for Boys', 'The Bumper Book for Girls'. The boys would get tales of historical derring-do, swordfights, brawls, sea-stories, war stories, plus practical tips on collecting hawk-moth caterpillars, how to make a compass with a cork, a magnet, a needle and saucer of water, and how to find your way in a forest by observing the moss on the north sides of trees. The girls' books would involve tales about flower fairies, the Girl Guides and Brownies, rivalries at hockey, lacrosse, and the ballet, how to make a Welsh rarebit, crochet a pretty mat for the table, and fold linen napkins into waterlilies or swans.

No wonder we wanted to be boys. No wonder we wanted to be George. And since boys also read 'The Famous Five' - in droves - George was our ambassador: incontrovertible if fictional proof that girls could have adventures too.

In spite of obvious real-life historical examples such as Grace Darling, Flora Macdonald, Florence Nightingale, and Mary Kingsley (who whacked crocodiles on the head with her canoe paddle and extolled 'the blessings of a good thick skirt' when travelling in Africa), writers stuffed their female leads into breeches if they were to do anything exciting. Geoffrey Trease, in his popular and well-written historical adventure stories for boys and girls, nearly always provided a cross-dressing heroine. There's 'Kit Kirkstone' aka Katherine Russell, in 'Cue For Treason', who runs away from an arranged marriage, falls in with a group of players, plays Shakespeare's Juliet, and ends up helping to foil a plot to kill Queen Elizabeth I. There's Angela D'Asola in 'The Hills of Varna' - a young Venetian scholar who - disguised as a boy - assists in the rescue of a priceless Greek manuscript from destruction at the hands of barbarous and ignorant monks. I loved these stories - they are still very readable - but along with Enid Blyton's George, they fostered in my childish mind the subconscious belief that to be adventurous or lead an interesting life, girls had to resemble boys. Which suggested girls per se were still somehow inferior.

I was interested to read the author's notes at the back of my copy of 'The Hills of Varna'. Trease claims his characters

... are no stranger than the real people who lived in the Italian Renaissance. One has only to think of girls like Marietta Strozzi, who broke away from her guardians at the age of eighteen, lived by herself in Florence, and had snowball matches by moonlight with the young gentlemen of that city; and Olympia Morata, who was lecturing on philosophy at Ferrara when she was sixteen.

Stirring stuff! I looked them up. And if the truth is not quite as romantic as Trease makes it sound, it's more complex and in some ways more interesting. Here is Marietta Strozzi, in a bust by Desiderio da Settignano: a cool and self-possessed young lady who was said to be the greatest beauty of Florence.

Despite the snowball fight (not a spontaneous street-corner affair between a gamine and a group of boys, but a piece of elaborate pageantry with political undercurrents) her life was bounded by the necessity to marry, and the limitations of being fatherless and "therefore" probably "stained". The young man who wished to marry her was dissuaded from doing so.

As for Olympia Morata, whose picture is here, it's true she was a remarkable woman. Her father was tutor to the dukes of Ferrara. Aged about twelve or thirteen,

already fluent in Greek and Latin, she became the friend and companion of the the young princess Anna D'Este. The court held protestant sympathies, and by sixteen Olympia was lecturing on Cicero and Calvin, writing and translating. In her early twenties she married a German Protestant who had come to Ferrara to study medicine. The young couple moved to Schweinfurt in Germany to evade the Inquisition, but were caught in the middle of war. Schweinfurt was occupied by the soldiers of the resplendently-named Albrecht Alcibiades, Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach: and Olympia and her husband lived in dangerous conditions, at one point taking refuge in a wine cellar. Ultimately, the city was sacked and burned. In a letter to her friend Cherubina Orsini, written at Heidelberg on August 8, 1554, Morata describes her difficult escape from Schweinfurt:

Vorrei che aveste visto come io era scapigliata, coperta di straccie, ché ci tolsero le veste d'attorno, e fuggendo io perdetti le scarpe, né aveva calze in piede, sì che mi bisognava fuggire sopra le pietre e sassi, che io non so come arrivasse.

I wish you had seen how dishevelled I was, dressed in rags, because they had taken away our clothes, and in fleeing I lost my shoes and nor had I socks on my feet, so I had to flee over the stones and the rocks - I do not know how I made it.

(Translation courtesy of Michelle Lovric.)

This is exciting by anyone's standards, considerably more of an adventure than most of us would wish to experience. Sadly, Olympia had not much longer to live. Shortly after arriving in Heidelberg,she began once again tutoring students in Greek and Latin, but a fever that she had caught in Schweinfurt never really subsided, and a few months later she died. She was not quite 29 years old: an early death, but not unusual for that place and time.

My point, though, is that here are two sixteenth century women who lived colourful, adventurous and energetic lives. Neither of them had to dress up in boys' clothes to do it. Yet their experiences and those of other women like them have been ignored or discounted down the centuries. Why? Because they are assumed to have been passive. Yet I doubt if Olympia Morata felt very passive while she was escaping barefoot, or Mary Kingsley while cracking the crocodile over the head. I'm willing to bet Olympia's life experiences were more dangerous and more 'exciting' than that of the Margrave Albrecht Alcibiades. Adventures are rarely very much fun for those who are in them. And, to return to Jo March with her beloved russet boots and old foil - was riding off on a horse to the wars ever really that much fun for the boys who had to do it?

Maybe we should look closer at our heroes as well as our heroines, and consider why the ability to fight is still so important to us that we tend - in fiction at least - to undervalue other forms of courage?

"I was talking about this with a friend, who said she hated fairytales as a little girl because she was so aware that the girls in them never had any fun - she wanted to be the one riding off on a horse to adventures but felt that to do so she would have to become a boy ... It made me wonder if being kick-ass is actually not about empowerment as such, it's about fun. The fairytale heroines you describe in your post are strong and determined and successful but they are also responsible in a way that the male characters are not. ... Being responsible (by being clever or determined or 'good') is not seen as glamorous, is not showy, is not always fun."

I'm sure this is so - at least, Jo March seemed to agree. "It's bad enough to be a girl, anyway, when I like boy's games, and work, and manners," she cries near the beginning of 'Little Women', and within a chapter or two is stalking the stage as the gallant Rodrigo in their home productions:

"No gentlemen were admitted; so Jo played male parts to her heart's content, and took immense satisfaction in a pair of russet-leather boots given her by a friend, who knew a lady who knew an actor. These boots, an old foil, and a slashed doublet once used by an artist for some picture, were Jo's chief treasures, and appeared on all occasions", and Jo appears "in gorgeous array, with plumed cap, red cloak, chestnut lovelocks, a guitar, and the boots, of course."

When I was nine I never wore a dress or a skirt if I could help it, and certainly not if my best friend was around - we always wore shorts or trousers (then termed 'trews'). We were tomboys (or so we liked to think). Together with our brothers we made rafts out of oildrums and bits of wood and tried to sail them on the River Wharfe; we fought the boys in the playground and got told off; we went up on Ilkley Moor with another friend who had a pony; we hid in the wooden hut shelter by Ilkley Tarn and made ghost noises as old ladies went past. We looked for adventures, for fun.

We were also keen readers. We were trying to channel George.

I assume you all know who George is, but just in case: George is the tomboy heroine of Enid Blyton's immensely popular 'Famous Five' series, which has never been out of print since 'Five On A Treasure Island' was published in 1942. Her real name is Georgina, but she refuses to answer to any name but 'George': she dresses like a boy and has cropped curly hair, she is 'as brave as a lion', never tells a lie, and is also, enviably, the owner of faithful Timmy, the gang's devoted dog. By strangers (especially stuffy new tutors and shady criminal types) she is generally mistaken for a boy, a mistake she takes as a compliment.

Even more than Jo March, George was a great relief to my generation. She was usually in the forefront of the action, even in the illustrations, thus:

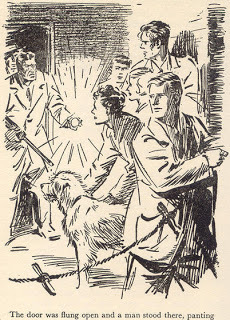

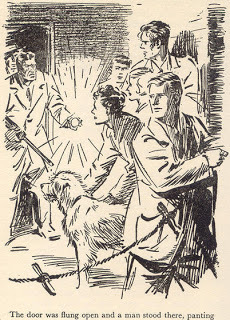

If there was a secret tunnel to be crawled down, or a midnight mission to embark upon, George would be there, with Timmy at her side always ready to have the essential scrawled message pinned to his collar: Trapped on Mystery Marsh. The maths tutor is a spy. The submarine will surface at midnight. Call Scotland Yard! George was fiery. She had a temper and she used it. She got into trouble for being rude: yet her instincts were always right. While Julian, Dick and Anne would shake their heads over the tea-table, George, banished to her room, would be spotting the mystery lights winking from the moor. Who would not want to be like her? - especially when the alternative looked like this:

This soppy girlie is Anne, mistaking a train for a volcano.

"I'm as good as a boy, any day!" was George's defiant cry: and so she was. But why did she have to dress as a boy to prove it?

It was because girls needed so badly to read about adventurous heroines, and for some reason most of the adults writing for them were unable to imagine the possibility that one could have adventures in a skirt. The sort of fun I enjoyed as a child - the pony-riding, the moorland walks, the raft-building, the make-belief - none of it was truly gendered: yet my friend and I felt it was: this was why we claimed the 'tomboy' label. The default assumption presented to us in the fiction we read was that women and girls did not have adventures; were hangers-on in history; led quiet, boring lives. You would imagine no woman ever stepped out of doors without a parasol.

This attitude has changed, but only gradually, and we're still not quite there. During my childhood in the 1960's - not so very long ago really - it had barely begun to shift. You have only to look at the school stories packaged separately, as they were: 'The Bumper Book for Boys', 'The Bumper Book for Girls'. The boys would get tales of historical derring-do, swordfights, brawls, sea-stories, war stories, plus practical tips on collecting hawk-moth caterpillars, how to make a compass with a cork, a magnet, a needle and saucer of water, and how to find your way in a forest by observing the moss on the north sides of trees. The girls' books would involve tales about flower fairies, the Girl Guides and Brownies, rivalries at hockey, lacrosse, and the ballet, how to make a Welsh rarebit, crochet a pretty mat for the table, and fold linen napkins into waterlilies or swans.

No wonder we wanted to be boys. No wonder we wanted to be George. And since boys also read 'The Famous Five' - in droves - George was our ambassador: incontrovertible if fictional proof that girls could have adventures too.

In spite of obvious real-life historical examples such as Grace Darling, Flora Macdonald, Florence Nightingale, and Mary Kingsley (who whacked crocodiles on the head with her canoe paddle and extolled 'the blessings of a good thick skirt' when travelling in Africa), writers stuffed their female leads into breeches if they were to do anything exciting. Geoffrey Trease, in his popular and well-written historical adventure stories for boys and girls, nearly always provided a cross-dressing heroine. There's 'Kit Kirkstone' aka Katherine Russell, in 'Cue For Treason', who runs away from an arranged marriage, falls in with a group of players, plays Shakespeare's Juliet, and ends up helping to foil a plot to kill Queen Elizabeth I. There's Angela D'Asola in 'The Hills of Varna' - a young Venetian scholar who - disguised as a boy - assists in the rescue of a priceless Greek manuscript from destruction at the hands of barbarous and ignorant monks. I loved these stories - they are still very readable - but along with Enid Blyton's George, they fostered in my childish mind the subconscious belief that to be adventurous or lead an interesting life, girls had to resemble boys. Which suggested girls per se were still somehow inferior.

I was interested to read the author's notes at the back of my copy of 'The Hills of Varna'. Trease claims his characters

... are no stranger than the real people who lived in the Italian Renaissance. One has only to think of girls like Marietta Strozzi, who broke away from her guardians at the age of eighteen, lived by herself in Florence, and had snowball matches by moonlight with the young gentlemen of that city; and Olympia Morata, who was lecturing on philosophy at Ferrara when she was sixteen.

Stirring stuff! I looked them up. And if the truth is not quite as romantic as Trease makes it sound, it's more complex and in some ways more interesting. Here is Marietta Strozzi, in a bust by Desiderio da Settignano: a cool and self-possessed young lady who was said to be the greatest beauty of Florence.

Despite the snowball fight (not a spontaneous street-corner affair between a gamine and a group of boys, but a piece of elaborate pageantry with political undercurrents) her life was bounded by the necessity to marry, and the limitations of being fatherless and "therefore" probably "stained". The young man who wished to marry her was dissuaded from doing so.

As for Olympia Morata, whose picture is here, it's true she was a remarkable woman. Her father was tutor to the dukes of Ferrara. Aged about twelve or thirteen,

already fluent in Greek and Latin, she became the friend and companion of the the young princess Anna D'Este. The court held protestant sympathies, and by sixteen Olympia was lecturing on Cicero and Calvin, writing and translating. In her early twenties she married a German Protestant who had come to Ferrara to study medicine. The young couple moved to Schweinfurt in Germany to evade the Inquisition, but were caught in the middle of war. Schweinfurt was occupied by the soldiers of the resplendently-named Albrecht Alcibiades, Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach: and Olympia and her husband lived in dangerous conditions, at one point taking refuge in a wine cellar. Ultimately, the city was sacked and burned. In a letter to her friend Cherubina Orsini, written at Heidelberg on August 8, 1554, Morata describes her difficult escape from Schweinfurt:

Vorrei che aveste visto come io era scapigliata, coperta di straccie, ché ci tolsero le veste d'attorno, e fuggendo io perdetti le scarpe, né aveva calze in piede, sì che mi bisognava fuggire sopra le pietre e sassi, che io non so come arrivasse.

I wish you had seen how dishevelled I was, dressed in rags, because they had taken away our clothes, and in fleeing I lost my shoes and nor had I socks on my feet, so I had to flee over the stones and the rocks - I do not know how I made it.

(Translation courtesy of Michelle Lovric.)

This is exciting by anyone's standards, considerably more of an adventure than most of us would wish to experience. Sadly, Olympia had not much longer to live. Shortly after arriving in Heidelberg,she began once again tutoring students in Greek and Latin, but a fever that she had caught in Schweinfurt never really subsided, and a few months later she died. She was not quite 29 years old: an early death, but not unusual for that place and time.

My point, though, is that here are two sixteenth century women who lived colourful, adventurous and energetic lives. Neither of them had to dress up in boys' clothes to do it. Yet their experiences and those of other women like them have been ignored or discounted down the centuries. Why? Because they are assumed to have been passive. Yet I doubt if Olympia Morata felt very passive while she was escaping barefoot, or Mary Kingsley while cracking the crocodile over the head. I'm willing to bet Olympia's life experiences were more dangerous and more 'exciting' than that of the Margrave Albrecht Alcibiades. Adventures are rarely very much fun for those who are in them. And, to return to Jo March with her beloved russet boots and old foil - was riding off on a horse to the wars ever really that much fun for the boys who had to do it?

Maybe we should look closer at our heroes as well as our heroines, and consider why the ability to fight is still so important to us that we tend - in fiction at least - to undervalue other forms of courage?

Published on April 05, 2013 01:00

No comments have been added yet.