After the Apocalypse

It's been an exciting week. I was asked to go along to the BBC to discuss dystopian fiction on Radio 4’s Open Book, together with Gillian Cross whose new book ‘After Tomorrow’ has just been published. Our conversation is on air this afternoon at 4.00pm, will be repeated on Thursday afternoon at the same time, and is (I’m told) available as a BBC podcast.

It's been an exciting week. I was asked to go along to the BBC to discuss dystopian fiction on Radio 4’s Open Book, together with Gillian Cross whose new book ‘After Tomorrow’ has just been published. Our conversation is on air this afternoon at 4.00pm, will be repeated on Thursday afternoon at the same time, and is (I’m told) available as a BBC podcast. Gillian’s books are always wonderful. ‘After Tomorrow’ tells the tale of two boys escaping to France through the Channel Tunnel after an economic and political collapse in Britain. My own dystopian credentials currently rest in the post-apocalyptic short story ‘Visiting Nelson’ – the germ of the novel I’m currently writing – published in the Windling/Datlow anthology ‘AFTER’ which you can see in the margin of this blog - the third cover from the top.

So I thought I might extend the conversation here with some general thoughts about dystopian and post-apocalyptic YA fiction and its appeal. And I'd love to hear your own opinions and recommendations.

If a utopia envisions a perfect, well-functioning society which we’re expected to contrast with the failures of our own, a dystopia does the opposite. It presents us with a society which is dysfunctional, which has gone badly wrong – in which aspects of our own contemporary society are pushed to an extreme. Utopias and dystopias have always been forms of social criticism, not just ‘imaginary worlds’. Tolkien’s Mordor would be an unpleasant place to live, but it isn't and was never intended to be a dystopia - any more than beautiful Lothlorien is a utopia. Nothing about either of them critiques contemporary society. But a dystopia is about us, living our own lives in our own world, reflected in a glass, darkly.

Dystopias and post-apocalyptic novels are often confused with one another: but – if you think about them in terms of Venn diagrams – it’s easy to spot the differences. In the circle labelled ‘dystopias’ are books about bad, usually highly controlling societies which need to be defied, reformed, reshaped. In the circle labelled ‘post-apocalyptic fiction’, the books pose a different challenge. A catastrophe has changed the world for ever: the characters’ task is to survive and rebuild. Where the two circles touch and overlap, there are books which combine elements of both. A post-catastrophic world may well spawn a dystopian society.

Dyslit, to use Terri Windling and Ellen Datlow’s convenient coinage, is a tremendously dramatic way of writing about society, and society is a subject which deeply interests many young adult readers. Where children accept their parents’ belief systems as a given, teenagers are full of questions. They want to make up their own minds, to test and try and decide things for themselves. Often they are passionate and idealistic and wherever they live, under whatever political system, they look at it with fresh, critical eyes, working out what’s good, what’s bad, what could be changed for the better? They arethe future: it’s theirs to mould and create, and they want to learn how – and we should want them to learn! Dystopian fiction is a forum for socio-political argument. It takes elements of the world we live in and holds them up to the light.

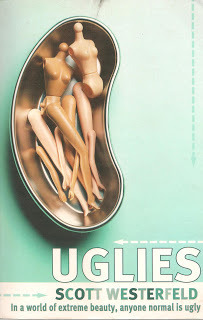

Thus, Scott Westerfield’s ‘Uglies’ and its sequels question the cult of beauty, the pressure to conform to unrealistically high standards, asking: What if everyone underwent plastic surgery as soon as they were sixteen or so, as a sort of initiation into adulthood? That’s obviously not happening around us, is it? Oh – wait a minute… Or what about reality shows and media violence? Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games examines a world in which the government runs gladiatorial shows in which people are actually killed. We know this is not impossible. It happened in the past, in ancient Rome. In some guise, could it happen again?

Thus, Scott Westerfield’s ‘Uglies’ and its sequels question the cult of beauty, the pressure to conform to unrealistically high standards, asking: What if everyone underwent plastic surgery as soon as they were sixteen or so, as a sort of initiation into adulthood? That’s obviously not happening around us, is it? Oh – wait a minute… Or what about reality shows and media violence? Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games examines a world in which the government runs gladiatorial shows in which people are actually killed. We know this is not impossible. It happened in the past, in ancient Rome. In some guise, could it happen again? No wonder dystopian fiction is so popular: it deals with real-world, often highly politicized questions: How much power should a government have to rule the lives of its people? What will happen when the oil runs out/the seas rise/the world warms or freezes? How would you cope with a terrorist attack/nuclear war/a global pandemic? Would you be emotionally strong enough? Could you survive? Dystopian fiction imaginatively represents the individual challenges, perhaps reminding the reader of comforts and conveniences we take for granted. (How would you wash your hair? Keep dry? Light a fire? Purify drinking water? Could you personally kill an animal for food?) In Jo Treggiari’s ‘Ashes, Ashes’, set amid the ruins of New York, something as small as a untied or broken shoelace can be a minor disaster, threatening your mobility and perhaps your survival. What does the future hold for us? What about the political issues in daily discussion around us: devolution, independence, immigration, religious intolerance, the freedom of the citizen versus the power of the state? Where will the internet society take us next? What about virtual realities, online lives: what roles will these things play? Will we retain our humanity? And what is it, anyway, to be human?

Most dyslit protagonists are young, passionate characters caught up in the mesh of their own problematic society and starting to ask these essential, awkward questions. The problems they face include numerous moral challenges. When survival is the key, should they selfishly look after themselves - or help someone else? Do they have the strength, the moral fibre to stand up and say 'this is wrong', when society declares it to be normal and right?

Though some people regard dystopian fiction as very dark - and it can be - it can also be inspiring, because it celebrates courage and hope, self reliance and compassion, the ability to look with a critical eye at the world we inhabit, and the desire to make that world a better place.

In no particular order - and in no way intended as a comprehensive list! - here are some titles I've enjoyed, a mixture of adult and childrens' fiction, old and new, obvious and less obvious. Please add your own recommendations in the comments!

Aldous Huxley – Brave New WorldGeorge Orwell – 1984 Margaret Atwood – The Handmaid’s TaleWilliam Golding – Lord of the Flies

John Wyndham – The Kraken Wakes, The Day of the Triffids, The Chrysalids

Peter Dickinson – The Changes Trilogy (even though the collapse of mechanized society in these books eventually turns out to have a supernatural cause, the workings-out of the changed Britain are practical and striking.)

Robert O’Brien – Z for ZachariahPatrick Ness – Monsters of MenJulie Bertagna – ExodusPaolo Bacigalupi – Ship BreakerJo Treggiari – Ashes, AshesMelvin Burgess – BloodtideMalorie Blackman – Noughts and CrossesScott Westerfield – UgliesBR Collins – Gamerunner

Published on April 14, 2013 01:22

No comments have been added yet.