Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 30

February 22, 2013

Folklore Snippets: The River Horse

From Scandinavian Folklore, William Craigie, 1896

The River Horse

The river-horse (bäck-hästen) is very malicious, for not content with leading folk astray and then laughing at them, when he has landed them in thickets and bogs, he, being Necken himself, alters his shape now to one thing and now to another, although he commonly appears as a light-grey horse.

It is certain that the river-horse still exists, for it is no more than a few years back that a man in Fiborna district, who owned a light-grey horse, was coming home late one night and saw, as he thought, the horse standing beside Väla brook. He thought it strange that his man had not taken in Grey-coat, and proceeded to do so himself, but just as he was about to lay hold of it it went off like an arrow and laughed loudly. The man turned his coat so as not to go astray, for he knew now who the horse was.

In Kristianstad there was a well, from which all the girls took drinking water, and where a number of the boys always gathered as well. One evening the river-horse was standing there, and the boys, thinking it was just an old horse, seated themselves on its back, one after the other, till there was a whole row of them, but the smallest one hung on by the horse’s tail. When he saw how long it was he cried, “Oh, in Jesus’ name!” whereupon the horse threw all the others into the water.

Another version:

One evening, many years ago, some young girls from Ryslinge had been out at a farm in Skirret, to help the woman there to card her wool, and it was pretty late before they started home. They followed the path from Skirret to Ryslinge, which went through the marsh. The girls were frightened as to how they were to get over this dangerous spot, but on coming to it they found there a lean old horse, so lean that one could count its ribs. The boldest of the girls immediately mounted on its back, and the others followed her example, for the more that mounted it, the longer grew the horse. They then rode into the marsh, but when they had got half way over, the foremost girl looked behind her, and when she saw that they were all on one and the same horse, she was so scared that she cried out,

“Jesus Christ’s cross!We are sitting all on one horse.”

As soon as this was said, the horse suddenly disappeared, and the girls were left standing in the middle of the bog, and had to wade to land.

Picture credit: An t-Òrd, Skye: Stranded water horse (Wikimedia Commons) Photo by Martin Gorman, who writes:"The skeleton of a stranded sea monster lies in a garden next to the beach at Ord. A sign informs that these are the only known remains of the long-tailed water horse Hydro equus extendus. Apparently they are only sighted twice a year when they swim inshore to browse on whelks. This one was stranded on an exceptionally low tide in 1967. You can't beat a good monster story!"

Published on February 22, 2013 01:04

February 14, 2013

Martial Arts for Cats?

This is an unashamed blast of the trumpet for a writer who isn't half as well known as he deserves to be. If you love children's fantasy adventure, I hope some of you will try these books. If you don't like them I'll eat my hat.

Nick Green's ‘The Cat Kin’ with its sequels ‘Cats Paw’ and 'Cat's Cradle' is a brilliant contemporary fantasy for young readers. What if a child could have a cat’s powers? What if you could jump ten times your own height, see in the dark, tread silently, be almost invisible? What if you had a very unusual teacher who could show you how to do all this, via a forgotten Ancient Egyptian martial art called 'pashki'? What wonderful advantages your new powers would give you, if you had to combat a bunch of evil crooks experimenting on animals in a nearby factory! What fun!

Nick Green's ‘The Cat Kin’ with its sequels ‘Cats Paw’ and 'Cat's Cradle' is a brilliant contemporary fantasy for young readers. What if a child could have a cat’s powers? What if you could jump ten times your own height, see in the dark, tread silently, be almost invisible? What if you had a very unusual teacher who could show you how to do all this, via a forgotten Ancient Egyptian martial art called 'pashki'? What wonderful advantages your new powers would give you, if you had to combat a bunch of evil crooks experimenting on animals in a nearby factory! What fun! A few years ago when I first heard of Nick Green's debut novel ‘The Cat Kin’, it was news. Nick had self-published the book believing in its worth: and he was absolutely right. After it was reviewed in The Times by Amanda Craig, who called it ‘a gripping adventure’, it was bought by Faber & Faber. Nick was writing the sequel, there was going to be a trilogy, and everyone was talking about it. What a great success story! So I whizzed out and bought a copy. I was entranced.

Two London kids, Ben and Tiffany, each living tough lives, join an after-school gym class run by a strange woman called Mrs Powell. And it turns out that what she teaches is the lost Egyptian art of ‘pashki’ – moving and sensing like a cat. Soon Ben, Tiffany and the rest of their class are leaping over London’s rooftops, slipping near-invisibly through the streets – and about to need all nine of their new lives as they discover the very dark deeds taking place in the old factory with the chimney like a wizard’s tower, visible from Ben’s apartment block. The plot is exciting, the writing is fresh, funny and perceptive.

But there’s a dark side to the books, too. Tiffany is struggling with the reality of her brother’s illness. There's a moral dilemma: what if illegal experiments could produce a drug to cure him? Ben and his mother are under threat, their apartment wrecked by thuggish developers who want them to move out. And both children have to learn responsibility for their new, sometimes frightening powers.

Well, there turned out to be a dark side to the success story of Nick’s publication, too. Despite so many good reviews, despite the fact that by this time Nick had written the sequel, Faber & Faber decided not, after all, to go ahead with publishing this second volume, ‘Cat’s Paw’.

This sort of crushing blow is something that only another author can fully understand. Bloodied but unbowed, Nick decided to self-publish ‘Cat’s Paw’, and be damned to 'em.

Which he did. And in the best fairytale tradition, courage and tenacity, allied to faith and talent, paid off. ‘The Cat Kin’ and 'Cat's Paw' were taken by ‘Strident Publishing’ and republished with a brand-new covers. The third book in the trilogy, ‘Cat’s Cradle' was published recently in 2012. I read it last week in one single gulp, and loved every minute! Tiffany and Ben combat their worst enemies yet: a criminal clan whose sinister art installation in Tate Modern looks like bringing London literally to its knees. The intrepid hero and heroine are evenly matched, and as they cheat death by crocodile and leap all over the roof of St Paul's Cathedral, their friendship turns delicately into something warmer. What's not to like?

Nick Green writes with flair, wit, and an enviable way with words. (I love the moment when Ben creeps up behind a criminal to put a pashki move on him: "The man slid to the floor, taken out as quietly as a library book.") He also has a tremendous sense of place. This is London. The books are brilliantly exciting. As far as the ticklish business of age range is concerned, I'd suggest the older end of the children's market, and younger teens (say a rough guide of 9 to 14?) because of some violence and the occasional death of sympathetic minor characters, which younger children might find upsetting. (You have to wait for the end of the trilogy to find out that the account of one death, at least, has been exaggerated.) But overall these are positive books with happy endings. They ought to be selling in shedloads.

Nick Green writes with flair, wit, and an enviable way with words. (I love the moment when Ben creeps up behind a criminal to put a pashki move on him: "The man slid to the floor, taken out as quietly as a library book.") He also has a tremendous sense of place. This is London. The books are brilliantly exciting. As far as the ticklish business of age range is concerned, I'd suggest the older end of the children's market, and younger teens (say a rough guide of 9 to 14?) because of some violence and the occasional death of sympathetic minor characters, which younger children might find upsetting. (You have to wait for the end of the trilogy to find out that the account of one death, at least, has been exaggerated.) But overall these are positive books with happy endings. They ought to be selling in shedloads.If you have a Kindle, you have a chance to try out Nick's latest book for yourselves. ( I haven't read it myself because I haven't yet succumbed to a Kindle, though this is the sort of thing that makes me weaken.) It's called 'The Storm Bottle' and you can download it FREE on February 14th and 15th by clicking on THIS LINK. And here's the description:

"Foam unzipped the waves. I saw a crescent fin, a glass-boulder forehead. The dolphin had come back."

Swimming with dolphins is said to be the number one thing to do before you die. For 12-year-old Michael, it very nearly is. A secret boat trip has gone tragically wrong, and now he lies unconscious in hospital.

But when Michael finally wakes up, he seems different. His step sister Bibi is soon convinced that he is not who he appears to be. Meanwhile, in the ocean beyond Bermuda’s reefs, a group of bottlenose dolphins are astonished to discover a stranger in their midst – a boy lost and desperate to return home.

Bermuda is a place of mysteries. Some believe its seas are enchanted, and the sun-drenched islands conceal a darker past, haunted with tales of lost ships. Now Bibi and Michael are finding themselves in the most extraordinary tale of all.

Damn it, I'm really going to have to get that Kindle.

Published on February 14, 2013 14:46

February 8, 2013

Thou Shalt Not Ride Sunwise Around Tara!

So - in this second post about the mysterious and powerful Irish injunctions called geasa- what on earth were they all about? There’s a note by PW Joyce at the back of his translation of 'Old Celtic Romances’ in which he comments,

Geasa means solemn vows, conjurations, injunctions, prohibitions. It would appear that individuals were often under geasa or solemn vows to observe, or to refrain from, certain lines of conduct – the vows being either taken on themselves voluntarily, or imposed on them, with their consent, by others. It would appear, also, that if one person went through the form of putting another under geasa to grant any reasonable request, the abjured person could not refuse without loss of honour and reputation.

Interesting as these comments are, they don’t seem quite to cover the range and quality of all geasa. Was the geas Gráinne laid upon Diarmuid a ‘reasonable request’ when she asked him, one of Finn’s faithful warriors, to marry her under Finn’s nose at a wedding feast that had been arranged partly to settle an old enmity between Finn and her father? It’s true that Diarmuid doesn’t have to agree – he asks several of his friends what he should do – but the unanimous decision of all is that though Diarmuid can decline Gráinne’s geasa, he will lose all honour if he does.

Thus there seem to me to be different kinds of geasa. Gráinne’s geas on Diarmuid is an almost insuperable injunction on him to do something he would never otherwise have dreamed of doing, and it involves him in loss of honour no matter what action he takes. The fact that he chooses to obey the geasarather than keep faith with his lord shows how incredibly powerful the injunction was considered to be. (So: not at all something you’d use to get the children to tidy up their rooms! Not something you’d use lightly!) Gráinne had given her father her consent to be Finn’s bride, but casually, ‘without giving much thought to the matter’:

“I know not whether he is worthy to be thy son-in-law; but if he be, why should he not be a fitting husband for me?”

When she sees Finn, however, she changes her mind. Desperate not to be married to this man older than her father, her eye falls upon handsome young Diarmuid. She uses the power of the geasas an extreme, last-minute measure: her only chance of escape.

Other geasa, however, are more in the style of prophetic warnings or tabus, like the many geasa laid upon King Conaire in 'The Destruction of Da Derga's Hostel'. He is not to shoot birds, for example, because his father was a bird-man, the male equivalent of the swan-maidens of many folktales, who can cast off their feathery skins and appear in human form. This is a straightforward tabu: you don’t kill the animal which is your totem, to which you are ‘related’ by spiritual bonds and by blood.

But the complicated geasaabout not going righthanded (sunwise) about Tara or lefthanded (widdershins) about Bregia, or following three Reds to the House of Red, or sleeping in a house from which firelight can be seen at night, these are prophetic warnings. They are not, perhaps, quite as inescapable as the prophecies of Greek myths. When the oracle at Delphi tells Oedipus he will slay his father and marry his mother, you know it’s a done deal. No matter what Oedipus does, no matter how hard he tries, this is what will happen. The event is foretold. In the case of the Irish King Conaire, however, the geasa merely indicate unlucky actions which ought to be avoided; and although the assumption is that somekind of bad luck will follow, they don’t spell out exactly what the consequences will be. Also, the prohibitions laid down by the geasa seem arbitrary: they are in themselves innocuous actions. We would all want to avoid killing our fathers and marrying our mothers. But most of us could ride clockwise around Tara, or sleep in a house with firelit windows, without coming to harm.

The geasapiled upon Conaire spell out a sequence of actions and omens which will lead to his death; but he cannot know this in advance. For the reader, or for the audience hearing Conaire’s tale told or sung aloud, the geasa are a highly effective literary, poetic device for building up tension and the sense of approaching doom. And in the same way, the two geasa laid upon Cú Chulain – not to eat the flesh of a dog, and never to refuse an offer of food from a woman – having lain dormant for much of the tale, snap together like the jaws of a trap as the old hags call him to turn aside from his journey towards the army of Maeve to taste the meat of the hound they are cooking. It’s a signal that the end is coming, a sign of doom. And Cú Chulain cannot escape it, although the tale makes it clear that he has the opportunity – he may refuse, but not without dishonour, not without falling short of his own greatness. “A great name outlasts life,” he says – like Achilles.

Cú Chulain has already seen the Washer at the Ford:

A young girl, thin and white-skinned and having yellow hair, washing and ever washing, and wringing out clothing that was all stained crimson red, and she crying and keening all the time.

“Little Hound,” said Cathbad, “do you see what it is that young girl is washing? It is your red clothes she is washing, and crying as she washes, because she knows you are going to your death against Maeve’s great army. And take the warning now, and turn back again.”

“I will not turn back” [says Cú Chulain] …”And what is it to me, the woman of the Sidhe to be washing red clothing for me? It is not long till there will be clothing enough, and armour and arms, lying soaked in pools of blood, by my own sword and spear. And if you are sorry and loth to let me go into the fight, I am glad and ready enough myself to go into it, though I know as well as you yourself I must fall in it. Do not be hindering me any more then,” he said, “for, if I stay or if I go, death will meet me all the same.”

(Translation by Lady Gregory)

As Jane Yolen poignantly said in her comment to last week's post, "We are all under a geasa--of life, of death. And trying to make sense of when it will be our time, we put the knowledge into story of battling what we know is inevitable."

I can’t confidently answer the question of whether geasa were ever truly used in real life, outside the tales and the epics, but I would hazard a guess that they were, just as we know that the oracles were regularly consulted in ancient Greece and in Rome. I’m willing to bet that there were geasa - prohibitions, tabus - against the killing or eating of various animals associated with ancestry and with luck, like Conaire’s bird/spirit father, and Cú Chulain’s iconic struggle with the hound which gave him his name. Once Cú Chulain had – effectively – become a hound, as he did when he offered himself to Chulain the smith in exchange for the dog he had killed, then in a sense all dogs became his kin. Of course he could not eat them.

I’m willing also to believe there were geasa or prohibitions concerning all kinds of other omens and lucky or unlucky actions or directions, because after all they still exist today: feng shui, not walking under ladders, not having thirteen at a dinner table.

But the geas that one person could lay upon another, to compel them to do something even against their will and their honour – that’s something else again, and as far as I know doesn’t seem to appear in other mythologies. Did it ever exist? Was it a metaphor for what we now call emotional blackmail? Or was it something more fearsome and holy, reserved perhaps for special occasions, for religio-political purposes? Was it a remnant of Druidical power?

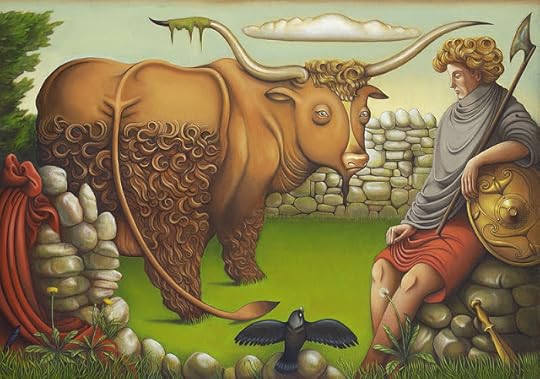

Picture credits:

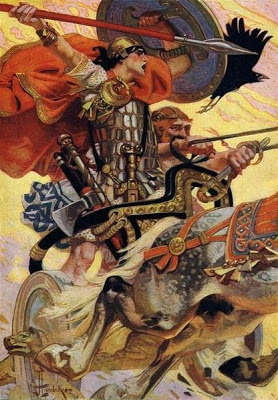

Cú Chulain and the Bull by Karl Beutel 2003 Oil on Canvas, Armagh County Museum Collection

Grainne - artist unknown, image from this link http://www.squidoo.com/diarmuid-and-grainne where you can find more Irish and Celtic stuff from http://www.squidoo.com/lensmasters/susannaduffy - if anyone recognises the artist please let me know and I will gladly credit him or her.

Statue of Cuchulainn by Oliver Sheppard in the window of the GPO, Dublin - commemorating the 1916 rising.

Source: Wikipedia, under Creative Commons License. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Cuchulain_at_GPO.jpg#filelinks

Published on February 08, 2013 02:43

February 1, 2013

Thou Shalt Not Eat the Flesh of a Dog!

‘Geasa’ – the magical prohibitions or tabus laid upon Irish heroes such as Cú Chulainn – must have been very difficult and frustrating to endure, especially since it seems to have been the fate of most heroes eventually to violate them.

‘Geasa’ – the magical prohibitions or tabus laid upon Irish heroes such as Cú Chulainn – must have been very difficult and frustrating to endure, especially since it seems to have been the fate of most heroes eventually to violate them. You remember how the young Setanta, son of Sualtim, gained the name Cú Chulain (‘Chulain’s Hound’), after killing the fierce guard-dog belonging to the smith Chulain? When Chulain complains of his hound’s death, the boy offers to make it up to him:

“If there is a whelp of the same breed to be had in Ireland, I will rear him and train him until he is as good a hound as the one killed, and until that time, Chulain,” he said, “I myself will be your watch-dog, to guard your goods and your cattle and your house.”

(Translation by Lady Augusta Gregory, ‘Cuchulain of Muirthemne’,1907)

After that, Cú Chulain was laid under two geasa: never to refuse a meal offered to him by a woman, and never to eat the flesh of a dog. At the end of his life, when he is riding out to fight against Maeve’s great army, the geasaare used against him by three witches at least as deadly as those in 'Macbeth':

After a while he saw three hags, and they blind of the left eye, before him in the road, and they having a venomous hound they were cooking with charms on rods of the rowan tree. And he was going by them, for he knew it was not for his good they were there.

But one of the hags called to him, “Stop a while with us, Cuchulain.” “I will not stop with you,” said Cuchulain. “That is because we have nothing better than a dog to give you,” said the hag. “If we had a grand, big cooking hearth, you would stop and visit us, but because it is only a little that we have, you will not stop.”

…Then he went over to her, and she gave him the shoulder-blade of the hound out of her left hand, and he ate it out of his left hand. And he put it down on his left thigh, and the hand that took it was struck down, and the thigh he put it on was struck through and through, so that the strength that was in them before left them.

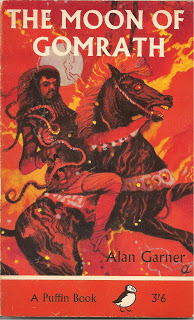

It couldn’t be more ominous, and presently, in forlorn battle against the odds, Cú Chulain is mortally wounded and straps himself to a pillar-stone, or standing stone, west of the lake of Muirthemne, so that he will not meet his death lying down: and his horse, the Grey of Macha, defends him with its teeth and hooves, until at last the hero dies and the crows descend upon him. Fans of ‘The Weirdstone of Brisingamen’ will notice that Alan Garner has used this scene for the death of the dwarf Durathror, who straps himself to the pillar of Clulow on Shuttlingslow, defending Colin and Susan from the morthbrood.

In ‘The Destruction of Da Derga’s Hostel’, which is another part of the Ulster cycle, King Conaire, whose father was a magical bird-man, is placed under a truly startling variety of geasa:

“Do not go righthandwise round Tara and lefthandwise around Bregia. Do not hunt the evil beasts of Cerna. Do not go out beyond Tara every ninth night; do not settle the quarrel of two of your own people; do not sleep in a house you can see the firelight shining from after sunset; do not let one woman or one man come into the house where you are after sunset; do not let three Reds go before you to the House of Red.”

But of course, one by one Conaire breaks all the geasa. He goes out to make peace between two of his subject lords, and travels the wrong way around Tara and Bregia to avoid raiders; he hunts the beasts of Cerna without realising what they are.

And it was the Sidhe that had made that Druid mist of smoke about him, because he had begun to break his bonds.

At last, on his way to find shelter in the hostelry of his friend Da Derga of Leinster, with its seven doors, Conaire sees himself preceded by three horsemen clad in red:

Three red bucklers they bore, and three red spears were in their hands: three red steeds they bestrode, and three red heads of hair were on them. Red were they all, both body and hair and raiment, both steeds and men.

(Translation by Dr Whitley Stokes, ‘The Destruction of Da Derga’s Hostel’, 1902)

Knowing another geasa has been broken, Conaire sends his young son Lefriflaith after the men to ask who they are. Lefriflaith calls out to them three times, and the third time one of them calls back that they are three of the Sidhe, banished from the elfmounds:

Lo, my son, great the news. Weary are the steeds we ride. We ride the steeds of Donn Tetscorach from the elf-mounds. Though we are alive we are dead. Great are the signs: destruction of life: sating of ravens: feeding of crows: strife of slaughter: wetting of sword-edge, shields with broken bosses after nightfall. Lo, my son!

The incantatory prose of Whitley Stokes’ translation has again been wonderfully taken up and adapted by Alan Garner in the chapter called ‘The Horsemen of Donn’ of ‘The Moon of Gomrath’, when Colin and Susan kindle fire on the mound:

They were dressed all in red: red were their tunics and red their cloaks; red their eyes and red their long manes of hair bound back with circlets of red gold; three red shields on their backs and three red spears in their hands… Red were they all, weapons and clothing and hair; both horses and men.

They were dressed all in red: red were their tunics and red their cloaks; red their eyes and red their long manes of hair bound back with circlets of red gold; three red shields on their backs and three red spears in their hands… Red were they all, weapons and clothing and hair; both horses and men.“Who – who are you?” whispered Colin. “What do you want?”

The middle horseman stood in his saddle and raised a glowing spear over his head:

“Lo, my son, great the news! Wakeful are the steeds we ride, the steeds from the ancient mound. Wakeful are we, the Horsemen of Donn, Einheriar of the Herlathing. Lo, my son!”

King Conaire’s last two geasaare broken when a lone woman comes to the door of Da Derga’s hostel (or inn): she has the Druid sight, and ill-wishes the king:

“It is what I see for you,” she said, “that nothing of your skin or of your flesh shall escape from the place you are in, except what the birds will bring away in their claws. And let me come into the house now.”

With great unwillingness the king allows the woman to enter, though not unnaturally “none of them felt easy in their minds after what she had said.” Finally, firelight from the hostel is spotted by Conaire’s enemy, Ingcel the One-Eyed and his army of reivers. They attack the hostel, great destruction is wrought, and Conaire dies.

A last example, just as ill-fated, is the geasa placed on Diarmuid by Gráinne, daughter of King Cormac and the promised bride of Finn MacCool. At the wedding feast Gráinne is put off by Finn’s age (older than her father!) and falls in love with one of his warriors, young Diarmuid. After sending Finn a cup that makes all who drink of it fall asleep, she asks Diarmuid to marry her, and when he refuses, she says,

I place thee under geasa, and under the bonds of heavy druidical spells, that thou take me for thy wife before Finn and the others awaken.

(Translation by P W Joyce, ‘Old Celtic Romances’, 1879)

Diarmuid replies:

Evil are those geasa thou hast put on me, and evil, I fear, will come of them.

He asks those of his friends whom Gráinne has not put to sleep what he should do, and they all agree he must follow the geasa even if it results in his death, which of course it eventually does, though not before many others have died first. Wounded by a boar, Diarmuid explains to Finn that Gráinne ‘put me under heavy geasa, which for all the wealth of the world I would not break,’ and begs Finn to save his life with a drink of water cupped in his healing hands. But, thinking of Gráinne, Finn spills the water three times and Diarmuid dies.

Maybe geasa were just a poetical, literary device, the equivalent of the prophecies about Greek heroes like Achilles and Oedipus, where the narrative imperative says that Achilles’ heel will be his undoing; that Oedipus will kill his father and marry his mother, etc. If not, though – if they ever had any real currency – you have to wonder. Could anyone use them? If so, how often? How carelessly? Could you do the equivalent of putting your children under geasa to pick up their socks and tidy their rooms? Or would that kind of thing backfire just as badly as most of them seem to have done in the tales? Geasa seem to have been impossible to refuse, however arbitrary or awkward they might be. In my next post, I’m going to take a closer look at how they actually operate, both in fiction and – maybe – in real life.

Picture credits:

Cuchulain in Battle by Joseph Christian Leyendecker, Wikimedia CommonsThe Moon of Gomrath by Alan Garner, cover by George Adamson

Published on February 01, 2013 01:00

January 25, 2013

Folklore snippets: The Childhood of Jesus

Jesus makes birds of clay: by Vitrearum, from his excellent blog Medieval Church Art - from a fifteenth century wallpainting at Shorthampton in Oxfordshire

Jesus makes birds of clay: by Vitrearum, from his excellent blog Medieval Church Art - from a fifteenth century wallpainting at Shorthampton in OxfordshireIt's not the end of January yet, so this is a post which still seems seasonal. And these old stories of the childhood of Jesus certainly count as folklore: current in medieval times, they have found their way into old songs and carols and even on to the walls of churches.

Charming as these tales are, with their vibrant images of children’s play, of tell-tales and rivalry, they also have a shocking impact. They show childhood’s ruthlessness as well as its innocence.

They are from the Apocryphal Gospels of Thomas and the Gospel of the Pseudo Matthew: the translation is by MR James (Oxford University Press 1924). James comments:

“The few Greek manuscripts are all late. The earliest authorities are a much-abbreviated Syriac version of which the manuscript is of the sixth century; and a Latin palimpsest at Vienna of the fifth or sixth century. The Latin version… is found in more manuscripts than the Greek; none of them, I think, is earlier than the thirteenth century.”

From the Greek Text B:

II 1 On a certain day when there had fallen a shower of rain he went forth of the house where his mother was and played upon the ground where the waters were running: and he made pools, and the waters flowed down, and the pools were filled with water. Then saith he: I will that ye become clean and wholesome. And straightway they did so.

2 But a certain son of Annas the scribe passed by bearing a branch of willow, and he overthrew the pools with the branch, and the waters were poured out. And Jesus turned about and said unto him: O ungodly and disobedient one, what have the pools done to thee that thou hast emptied them? Thou shalt… be withered up even as the branch which thou hast in hand.

3 And he went on, and after a little he fell and gave up the ghost. And when the young children that played with him saw it, they marvelled and departed and told the father of him that he was dead. And he ran and found the child dead, and went and accused Joseph.

III 1 Now Jesus made of that clay twelve sparrows: and it was the Sabbath day. And a child ran and told Joseph, saying: Behold, thy child playeth about the brook, and hath made sparrows of the clay, which is not lawful.

2 And he when he heard it went and said to the child: Wherefore doest thou so and profaneth the Sabbath? But Jesus answered him not, but looked upon the sparrows and said: Go ye, take your flight, and remember me in your life. And at the word they took flight and went up into the air. And when Joseph saw it he was astonished.

The last part of the story was taken up (and embellished) by Hilaire Belloc who wrote this very sweet poem, published 1910:

When Jesus Christ was four years oldThe angels brought Him toys of gold,Which no man ever had bought or sold.

And yet with these He would not play,He made Him small fowl out of clayAnd blessed them till they flew away: Tu creasti Domini

Jesus Christ, thou child so wise,Bless mine hands and fill mine eyes,And bring my soul to Paradise.

However, closer to the apocryphal gospels is the old ballad ‘The Bitter Withy’, collected by Vaughan Williams in Shropshire and Herefordshire in 1908/9. It is based on tales from the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew and also from a 13th century poem on the childhood of Jesus known as the Vita Rhythmica. In the ballad, Jesus asks his mother if he may go and play ball:

So up the hill and down the hill Our sweet young Saviour ranUntil he met three rich young lordsAll playing in the sun.

“Good morn, good morn, good morn,” said they,“Good morning then,” cried he,“And which of you three rich young lordsWill play at ball with me?”

But the rich young lords despise him:

“We are all lords’ and ladies’ sonsBorn in a bower and hall,And you are nothing but a poor maid’s childBorn in an ox’s stall.”

Alas, you don’t meddle with divinity.

“Well though you’re lords’ and ladies’ sonsAll born in your bower and hall,I’ll prove to you at your latter endI’m an angel above you all.”

So he built him a bridge from the beams of the sunAnd over the water ran he,The rich young lords chased after himAnd drowned they were all three.

So up the hill and down the hillThree rich young mothers ranSaying, “Mary mild, fetch home your child,For ours he’s drowned each one.”

Then Mary mild, she took her childAnd laid him across her knee,And with a handful of withy twigsShe gave him slashes three.

“Oh bitter withy, oh bitter withy,You’ve causèd me to smart,And the withy shall be the very first treeTo perish at the heart.”

Far from being sorry for what he’s done, the little Christ Child curses the withy itself – the willow wands with which his mother has whipped him. There’s a wry, very conscious humour in this ballad. It’s been made up and sung by people who were used to being the underdogs, who could only console themselves that, ultimately, God was on the side of the poor and the humble, not the lords and ladies. They knew they would never find equality this side of heaven, however: so the ballad is a joke – a knowing, tender, deliberate joke – about children, and the way they play and quarrel, and the topsy-turvy chaos that is caused when the innocent but all-powerful Christ Child lashes out against those who jeer at him… and how even HE has to be taught a lesson when he goes too far.

Here's Maddy Prior singing 'The Bitter Withy' at Cecil Sharp House, 23rd October 2008

Published on January 25, 2013 01:04

January 18, 2013

Addlers and Menters

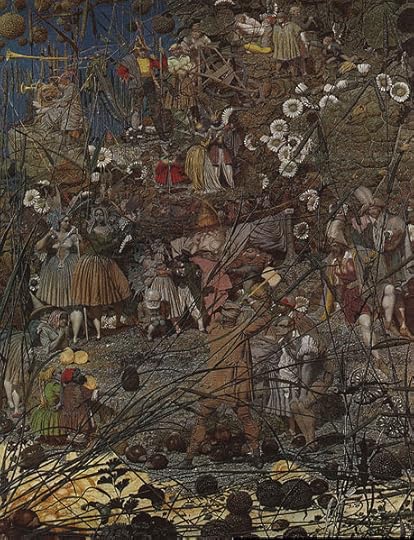

The Fairy Feller's Master Stroke - Richard Dadd

The Fairy Feller's Master Stroke - Richard DaddLike the tale of the 'Elf Dancers of Cae Caled' which I posted up a few weeks ago, some folk tales sound so detailed and oddly convincing, you feel they must be true – whatever ‘truth’ may mean. And then again, you start to wonder. Here are two fairy stories from Thomas Keightley’s Fairy Mythology (1828) which have set me thinking carefully about the way they may have been collected.

This is the first tale, with Keightley’s original asterisk and footnote:

Addlers and Menters

An old lady in Yorkshire related as follows:– My eldest daughter Betsey was about four years old; I remember it was on a fine summer’s afternoon, or rather evening, I was seated in this chair which I now occupy. The child had been in the garden, she came into that entry or passage from the kitchen (on the right side of the entry was the old parlour-door, on the left the door of the common sitting-room; the mother of the child was in a line with both doors); the child, instead of turning towards the sitting room made a pause at the parlour-door, which was open. She stood several minutes quite still; at last I saw her draw her hand quickly towards her body; she set up a loud shriek and ran, or rather flew, to me crying out “Oh! Mammy, green man will hab me! green man will hab me!”

It was a long time before I could pacify her; I then asked her why she was so frightened. “O Mammy,” said she, “all t’parlour is full of addlers and menters.” Elves and fairies (spectres?) I suppose she meant. She said they were dancing, and a little man in a green coat with a gold-laced cocked hat on his head, offered to take her hand as if he would have her as his partner in the dance.

The mother, upon hearing this, went and looked into the old parlour, but the fairy vision had melted into thin air.

“Such,” adds the narrator, “is the account I heard of this vision of fairies. The person is still alive who witnessed or supposed she saw it, and though a well-informed person, still positively asserts the relations to be strictly true.” *

*And true no doubt it is: ie: the impression made on her imagination was as strong as if the objects had been actually before her. The narrator is the same person who told the preceding boggart story.

It’s frustrating that Keightley did not often name his contributors. In ‘Addlers and Menters’ we initially assume the narrator to be the old lady mentioned in the first sentence. However, a different voice creeps in to comment upon the layout of the house – this is the person she is telling the story to, who in the absence of any clue to the contrary, we suppose to be Keightley himself. Only in the last paragraph do we realise that the person to whom this story was told is not Keightley after all, but an unnamed contributor. We are therefore getting the story at third hand: and it’s not at all clear from Keightley’s own footnote whether the ‘person still alive who witnessed it’ is the old lady, or her daughter, little Betsey, now grown up.

The detail of the first two paragraphs – the well visualised domestic interior, the little girl coming in from the garden, the pause by the open parlour door, the child’s sharply observed gesture of ‘drawing her hand quickly towards her body’, and her terrified shriek – all suggest a genuine experience of some sort, if only a frightening waking dream or hallucination, which has later been ‘finished off’ with a conventional literary ending. Addlers and menters? Whether dialect words or childish gabble, they somehow carry conviction. But the civilized little man with green coat and gold-laced cocked hat who invites the child to dance – does not. He is hardly convincing as the source of such childish terror.

I find it fascinating to compare the style of this tale with the Boggart story which Keightley’s footnote declares to have been narrated by the same person – whether the old lady herself, the daughter, or Keightley’s unnamed contributor. Here is the boggart story:

The Boggart

In the house of an honest farmer in Yorkshire, named George Gilbertson, a Boggart had taken up his abode. He here caused a great deal of annoyance, especially by tormenting the children in various ways. Sometimes their bread and butter would be snatched away, or their porringers of bread and milk be capsized by an invisible hand; for the Boggart never let himself be seen; at other times, the curtains of their beds would be shaken backwards and forwards, or a heavy weight would press on and nearly suffocate them. The parents had often, on hearing their cries, to rush to their aid. There was a kind of closet, formed by a wooden partition, on the kitchen stairs, and a large knot having been driven out of the deal boards of which it was made, there remained a hole. Into this one day the farmer’s youngest boy stuck the shoe-horn with which he was amusing himself, when immediately it was thrown out again, and struck the boy on the head. The agent was of course the Boggart, and it soon became their sport (which they called laking with Boggart) to put the shoe-horn into the hole and have it shot back at them.

The Boggart at length proved such a torment that the farmer and his wife resolved to quit the house and let him have it all to himself. This was put into execution, and the farmer and his family were following the last loads of furniture, when a neighbour named John Marshall came up – “Well, Georgey,” said he, “and soa you’re leaving t’ould hoose at last?” – “Heigh, Johnny my lad, I’m forced tull it. For that damned Boggart torments us soa, we can neither rest neet nor day for’t, and soa you see, we’re forced to flitt.” He scarce had uttered the words when a voice from a deep upright churn cried out, “Aye, aye, Georgey, we’re flitting ye see.” – “Od damn thee,” cried the poor farmer, “if I’d known thou’d been there, I wouldn’t ha’ stirred a peg. Nay nay, it’s no use, Mally,” turning to his wife, “we may as weel turn back again to t’ould hoose as be tormented in another that’s not so convenient.”

So here’s another story which seems split in two. Or even three. Most people will recognise the second paragraph as a well known popular folktale, complete in itself, Aarne-Thompson Type ML.7020. Motif: F.482.3.1.1 [Farmer is so bothered by brownie that he decides he must move, etc]. Here, it seems to have been tacked on to the first part, which itself appears to have been cobbled together from two other narratives, one about a poltergeist or unquiet spirit which terrorises some young children; the other involving some boys who, far from being afraid of their boggart, actually play a game with him: ‘laking with Boggart’ – in which he fires objects like the shoe-horn out of the hole into which they push them. ‘Laking with boggart’, which means ‘playing with the boggart’ is convincing Yorkshire usage (they still say ‘laiking about’ in Yorkshire, and drop the definite article.) Most of the domestic detail, the closet on the kitchen stairs, and the knot-hole, and the boys with the shoe-horn, comes from this part of the story.

Apart from the dialogue, the story is told in a rather flat ‘literary’ style – ‘In the abode of an honest farmer’, ‘this was put into execution’, etc, but the second paragraph is not entirely convincing in its attempt at a colloquial dialect. For one thing, the farmers address one another with the formal ‘you’. Instead of John Marshall’s ‘Soa you’re leaving at last’, I’d expect the informal ‘Soa th’art leaving at last’. Even if John Marshall is actually addressing George and his family – plural – George’s response is ‘and soa you see, we’re forced to flitt’- instead of the more likely ‘and soa tha sees, we’re forced to flitt’. Apart from the phrase ‘laking with boggart’, none of this story conveys the impression of someone scribbling down what he has actually heard. Whereas the little girl’s words in ‘Addlers and Menters’ sound as if they’ve been written down verbatim, the dialogue in the second paragraph of The Boggart’ seems much more like what someone thinks is the way a Yorkshire farmer talks.

So what’s been going on? In my opinion, someone has decided to turn a series of anecdotes – odd in themselves, but short and inconclusive – into stories, ‘improving’ them by linking them together into a narrative. And who was that someone? It could be Keightley himself, of course, but personally I suspect his unnamed contributor, the person who listened to the old Yorkshire lady. It’s perfectly possible the old lady told him all the ingredients of these stories, as separate tales – I’m sure she supplied the names of George Gilbertson and John Marshall, and the anecdote of the shoe-horn. But I don’t believe they were originally linked. And I think that the addlers and menters, the poltergeist, and the shoe-horn game are much more convincing – and far more unsettling – when left on their own.

Picture credit: Richard Dadd: The Fairy Feller's Master Stroke (Tate Britain) Wikimedia Commons

Published on January 18, 2013 00:44

January 11, 2013

White Ladies

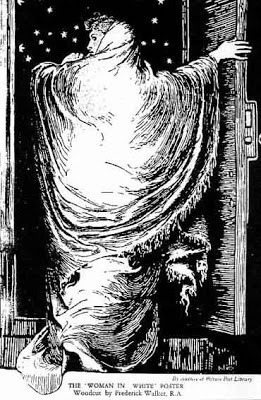

In my book ‘Dark Angels’ (US title ‘The Shadow Hunt’) the castle of La Motte Rouge, which shelters below the hill called Devil’s Edge, is haunted by a mournful White Lady who wanders the courtyard on dark and misty nights, wringing her hands and moaning softly. She’s creepy but harmless, she's forgotten her own name; she may be the diminished pagan spirit of the spring which feeds the castle’s cistern, and is regarded by the various inhabitants with attitudes ranging from fear to pity. In this passage the saintly old priest Howell intercepts her as she peers in at the door of the castle’s chapel:

In my book ‘Dark Angels’ (US title ‘The Shadow Hunt’) the castle of La Motte Rouge, which shelters below the hill called Devil’s Edge, is haunted by a mournful White Lady who wanders the courtyard on dark and misty nights, wringing her hands and moaning softly. She’s creepy but harmless, she's forgotten her own name; she may be the diminished pagan spirit of the spring which feeds the castle’s cistern, and is regarded by the various inhabitants with attitudes ranging from fear to pity. In this passage the saintly old priest Howell intercepts her as she peers in at the door of the castle’s chapel:Billows of mist floated across the yard, and the pale lady was still moaning and wringing her hands at the chapel door.

“Hush now, hush!” the old man called in a soothing voice. The lady turned to him like a frightened child.

“I can’t remember. I can't remember my name…”

“Dear, dear. …But that’s all right, because you see, we have a name for you. Dame Blanche, our White Lady, our sweet Ladi Wen.” He dropped into musical Welsh, and the lady listened very attentively. When he had finished she bowed her head and walked smoothly away. The mist followed her. Her feet moved a fraction above the ground, and when she reached the dark corner of the building, Wolf wasn’t sure if she went around it, or just vanished.

You can catch a glimpse of her here.

White Ladies are a bit different from other ghosts. In an article called The White Lady of Britain and Ireland, by Jane C Beck (Folklore, Vol 81, 1970), Beck argues that “the modern day ghost known as the White Lady … is …a creature with a heritage reaching back to the darkest recesses of time. Although her most usual form today is that of a gliding spectre, some of the acts she performs recall her earlier condition as a deity.”

Ghost stories often come complete with ‘explanations’ for the apparition - explanations which usually feel contrived. Frequently they involve some sort of crime: the ghost is unable to rest because it is either the victim or the perpetrator. White ladies are often described as murdered brides or sweethearts, or else girls who have drowned themselves for love. They are frequently associated with water. A story from Yorkshire, reported in 1823, tells how a lovely maiden robed in white is to be seen on Hallowe’en at the spot where the rivers Hodge and Dove meet, standing with her golden hair streaming and her arm around the neck of a white doe. From Somerset, Ruth Tongue describes an apparition called the White Lady of Wellow,

… who haunts St Julian’s Well, now in a cottage garden. She played the part of a banshee to the Lords of Hungerford, but she seems to have been a well spirit rather than a ghost. The Lake Lady of Orchardleigh is another white lady who is rather a fairy than a ghost. But the most fairy-like of the three is the White Rider of Corfe, who…gallops along the road on a white horse, turns clean aside by a field gate and into the middle of a meadow, where she vanishes. I was told about her by some old-age pensioners in the Blackdown Hills in 1946. One of them said. “She shone like a dewdrop,” and another of them, “T’was like liddle bells all a-chime.”

In Wales there are apparently two types of white ladies, the Dynes Mewn Gwyn or lady in white, and the ladi wen: the first is a true ghost; the second is an apparition which haunts the place where someone has died a violent death. Not all White Ladies are harmless. Jane Beck tells of one which appeared at Ogmore Castle near Bridgend, Glamorgan, where she was believed to guard a treasure under the tower floor. One man was brave enough to speak to her; she gave permission to take half the treasure and showed him where it lay, but when he was so greedy as to return for the rest:

The White Lady then set upon him, and to his dismay, he found she had claws instead of fingers, and with these she nearly tore him to pieces.

Jacob Grimm, in his Teutonic Mythology, talks of the White Lady as someone who

… appears in many houses when a member of the family is about to die, and …is thought to be the ancestress of the race. She is sometimes seen at night tending and nursing the children… She wears a white robe, or is clad half in white, half in black; her feet are concealed buy yellow or green shoes. In her hand she usually carries a bunch of keys or a golden spinning wheel.

I’m strongly reminded of Princess Irene’s great-great (ever-so-many-greats) grandmother in George MacDonald’s ‘The Princess and the Goblin’, a beautiful woman with long white hair who can seem both old and young, who inhabits the top floor of the castle tower, and sits spinning her magical moony wheel. When Irene climbs the tower steps and taps at the door:

“Come in, Irene,” said the sweet voice.

The princess opened the door and entered. There was the moonlight streaming in at the window, and in the middle of the moonlight sat the old lady in her black dress with the white lace, and her silvery hair mingling with the moonlight, so that you could not have told which was which.

And is the Lady of the Lake, in the Morte D’Arthur, a White Lady? She is seen by Arthur and Merlin ‘going upon the lake,’ and although it is not actually her arm ‘clothed in white samite’, which brandishes the sword Excalibur above the water, she does tell Arthur that the sword belongs to her. Whose is the arm, then? We never find out.

In John Masefield’s wonderful wintry book “The Box of Delights’, there’s a passage which well combines the ambiguous mystery and dread of the White Lady. Kay Harker is out on the Roman Road on a night ‘as black as a pocket’ and sees something white moving towards him:

He remembered, that Cook had said, there was a White Lady who “walked” out Duke’s Brook way. This thing that was coming was a White Lady… but supposing it was a White Wolf, standing on its hind legs and ready to pounce. It looked like a wolf; its teeth were gleaming. Then the moon shone out again; he saw that it was a White Lady who held her hand in a peculiar way, so that he could see a large ring, with a glittering ‘longways cross’ on it.

“Come Kay,” she said, “you must not stay here; the Wolves are running: listen.”

Significantly the White Lady (who in this case is wholly benevolent) is still believed by Cook to haunt a water course: Duke’s Brook. Masefield’s fiction is full of folklore, in which he clearly took great delight: his White Lady runs true to type.

Before the Romans came to Britain, the British appear to have worshipped the deities – many or mainly female – of rivers, streams, springs and pools. Most of their names, like that of my White Lady, must have been forgotten, but we still know Sabrina of the River Severn, and Sulis, who gave her name to Aquae Sulis, the hot springs at Bath. To the waters of these springs, pools and rivers, the British made offerings – just as we still throw coins into fountains – and many is the bronze or iron age sword which has been recovered from river beds and marshlands. How many Bediveres have thrown precious weapons to the Lady of the Lake? And what did they hope to receive in return? Health? Wealth? Victory?

I like White Ladies – beautiful, eerie creatures draped in moonlight, trailing clouds of grief and longing for those far-away ages when they still had the power to bless and to curse.

Picture credits:

The Woman in White by Frederick Walker, image courtesy of The Victorian Web

Irene's Grandmother, by Arthur Hughes; illustration from The Princess and the Goblin by George Macdonald

Sulis Minerva in the Museum of Bath by Akalvin at Wikimedia Commons. Original uploader was Akalvin at de.wikipedia

Published on January 11, 2013 01:02

January 7, 2013

Folklore snippets: The Elf Dancers of Cae Caled

From “Welsh Folk-Lore” by Elias Owen, 1887

This is taken from an account of a childhood event experienced near Lanelwyd House, Bodfari, Denbigh, by one Dr Egbert or Edward Williams and written, according to Elias Owen, in 1757. I think it's remarkable both for the immediacy of the account (he writes as if it had happened yesterday) and for the terror felt by all the children as soon as they witness the mysterious dancers. Notable also is the fact that the elf or dwarf cannot pass the boundary of the stile.

On a fine summer day (about midsummer) between the hours of 12 at noon and one, my eldest sister and myself, our next neighbours' children Barbara and Ann Evans, both older than myself, were in a field called Cae Caled near their house, all innocently engaged at play by a hedge under a tree, and not far from the stile next to that hedge, when one of us observed on the middle of the field a company of – what shall I call them? – Beings, neither men, women, nor children, dancing with great briskness. They were in full view less than a hundred yards from us, consisting of about seven or eight couples; we could not well reckon them [count them], owing to the briskness of their motions and the consternation with which we were struck at a sight so unusual. They were all clothed in red, a dress not unlike a military uniform, without hats, but their heads tied with handkerchiefs of a reddish colour, sprigged or spotted with yellow, all uniform in this as in habit, all tied behind with the corners hanging down their backs, and white handkerchiefs in their hands held loose by the corners. They appeared of a size somewhat less than our own, but more like dwarfs than children.

On the first discovery we began, with no small dread, to question one another as to what they could be, as there were no soldiers in the country, not was it the time for May dancers, and as they differed much from all the human beings we had ever seen. Thus alarmed we dropped our play, left our station, and made for the stile. Still keeping our eyes upon them we observed one of their company starting from the rest and making towards us at a running pace. I being the youngest was the last at the stile, and, though struck with an inexpressible panic, saw the grim elf just at my heels, having a full and clear, though terrific view of him, with his ancient, swarthy and grim complexion. I screamed out exceedingly; my sister also and our companions set up a roar, and the former dragged me with violence over the stile on which, from the moment I was disengaged from it, this warlike Lilliputian leaned and stretched himself after me, but came not over.

With palpitating hearts and loud cries we ran towards the house, alarmed the family and told them our trouble. The men instantly left their dinner, with whom still trembling we went to the place, and made the most solicitous and diligent enquiry in all the neighbourhood, both at that time and after, but never found the least vestige of any circumstance that could contribute to a solution of this remarkable phenomenon…

Picture Credits:

Picture Credits:Wikimedia Commons:

Fairies dancing in a ring: Woodcut from an old English chapbook. 17th century?

Fauns, devils, elves (?) dancing: Woodcut by Olaus Magnus, "Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus", 1555

Published on January 07, 2013 01:02

December 24, 2012

The Angels Dancing in the Sun

Happy Christmas, happy holidays to all of you. May the next year bring you all good things. To celebrate the season, here's an extract from my medieval fantasy 'Dark Angels', in which the young hero Wolf fulfills a promise to meet his friend Nest, daughter of a Norman lord and a Welsh princess, at the top of the watch tower of the castle La Motte Rouge at daybreak on Christmas morning, in the hope of seeing angels dancing in the sunrise. Wolf has bad news for Nest, and danger is all about them - but - it's still Christmas...

FAR across the snow-filled valley the sky was changing from blue to the palest apricot. Wolf hurried, slipping and stumbling. When he reached the door at the bottom of the tower, it was ajar, and clods of snow had been stamped off on the dark floor just inside. The ladder ran up into the gloom. He climbed steadily, rung after rung, till his head and shoulders emerged into the chilly little room at the top of the tower. Snow had gusted through the open windows and doorway, and coated the boards with white powder.

FAR across the snow-filled valley the sky was changing from blue to the palest apricot. Wolf hurried, slipping and stumbling. When he reached the door at the bottom of the tower, it was ajar, and clods of snow had been stamped off on the dark floor just inside. The ladder ran up into the gloom. He climbed steadily, rung after rung, till his head and shoulders emerged into the chilly little room at the top of the tower. Snow had gusted through the open windows and doorway, and coated the boards with white powder.

"Look out," said Nest quietly. "It's slippery."

"You remembered!"

"So did you!"

They beamed at each other.

"I wasn't sure you would, " said Nest, "but I came in case."

... She picked up a cloth bundle tied with knots. "Here - this is for you. Take it!"

Mystified, Wolf untied the knots. Out fell a long-sleeved tunic. A linen shirt. Warm, tight-fitting hose for his legs. And a fine woollen cloak lined with rabbit-fur. They were new. Nest must have been making them for weeks. He looked up at her, speechless.

"Merry Christmas," she said gruffly.

"I can't believe you did this," he said in a hoarse voice. "Thank you." He looked at the clothes again, fingering the cloth. "Nest - I came to tell you -"

A gleam of pink light touched her face. "No!" she pleaded. "Don't tell me yet. Remember why we came? Look, the sun's nearly up!"

Wolf swept snow from the rail. They leaned on it, looking east. Every moment, the colour in the sky grew stronger. A vast cloud stood high over Crow Moor. It flushed rose and peach and gold and began to brighten beyond colour, into pure light. Out of nowhere a small wind ruffled their faces.

Christus natus est! Christ is born! Far below their feet a cock crowed, wild and shrill. A goblet of fire too bright to look at rose over the rim of the world. Fields and woods leaped to life. Rays of light struck across the valley, and the snow-crusted edge of the rail where they leaned turned all to diamonds.

A lump came into Wolf's throat. Poised here on the tower, high above the world, his hard decisions and troubles seemed tiny and unimportant.

Nest grabbed his hand. "Oh Wolf," she breathed. "Look."

Above the joyful blazing disc of the sun, the sky was hammered silver. White sparks appeared in it, like morning stars. Wolf squinted between the bars of his fingers. Far, far away, leaving streaks and curls of fire, the angels danced like a flock of birds before the sun, their immeasurably distant wings flashing.

Dark Angels by Katherine Langrish, HarperCollins

US edition: The Shadow Hunt, HarperCollins

Happy Christmas to you all!

Picture credits:

Sunrise over Boldron fields by Andy Waddington, Wikimedia Commons

Angels dancing in the sun by Giovanni di Paolo (Musee Conde), Wikimedia Commons

FAR across the snow-filled valley the sky was changing from blue to the palest apricot. Wolf hurried, slipping and stumbling. When he reached the door at the bottom of the tower, it was ajar, and clods of snow had been stamped off on the dark floor just inside. The ladder ran up into the gloom. He climbed steadily, rung after rung, till his head and shoulders emerged into the chilly little room at the top of the tower. Snow had gusted through the open windows and doorway, and coated the boards with white powder.

FAR across the snow-filled valley the sky was changing from blue to the palest apricot. Wolf hurried, slipping and stumbling. When he reached the door at the bottom of the tower, it was ajar, and clods of snow had been stamped off on the dark floor just inside. The ladder ran up into the gloom. He climbed steadily, rung after rung, till his head and shoulders emerged into the chilly little room at the top of the tower. Snow had gusted through the open windows and doorway, and coated the boards with white powder."Look out," said Nest quietly. "It's slippery."

"You remembered!"

"So did you!"

They beamed at each other.

"I wasn't sure you would, " said Nest, "but I came in case."

... She picked up a cloth bundle tied with knots. "Here - this is for you. Take it!"

Mystified, Wolf untied the knots. Out fell a long-sleeved tunic. A linen shirt. Warm, tight-fitting hose for his legs. And a fine woollen cloak lined with rabbit-fur. They were new. Nest must have been making them for weeks. He looked up at her, speechless.

"Merry Christmas," she said gruffly.

"I can't believe you did this," he said in a hoarse voice. "Thank you." He looked at the clothes again, fingering the cloth. "Nest - I came to tell you -"

A gleam of pink light touched her face. "No!" she pleaded. "Don't tell me yet. Remember why we came? Look, the sun's nearly up!"

Wolf swept snow from the rail. They leaned on it, looking east. Every moment, the colour in the sky grew stronger. A vast cloud stood high over Crow Moor. It flushed rose and peach and gold and began to brighten beyond colour, into pure light. Out of nowhere a small wind ruffled their faces.

Christus natus est! Christ is born! Far below their feet a cock crowed, wild and shrill. A goblet of fire too bright to look at rose over the rim of the world. Fields and woods leaped to life. Rays of light struck across the valley, and the snow-crusted edge of the rail where they leaned turned all to diamonds.

A lump came into Wolf's throat. Poised here on the tower, high above the world, his hard decisions and troubles seemed tiny and unimportant.

Nest grabbed his hand. "Oh Wolf," she breathed. "Look."

Above the joyful blazing disc of the sun, the sky was hammered silver. White sparks appeared in it, like morning stars. Wolf squinted between the bars of his fingers. Far, far away, leaving streaks and curls of fire, the angels danced like a flock of birds before the sun, their immeasurably distant wings flashing.

Dark Angels by Katherine Langrish, HarperCollins

US edition: The Shadow Hunt, HarperCollins

Happy Christmas to you all!

Picture credits:

Sunrise over Boldron fields by Andy Waddington, Wikimedia Commons

Angels dancing in the sun by Giovanni di Paolo (Musee Conde), Wikimedia Commons

Published on December 24, 2012 01:31

December 21, 2012

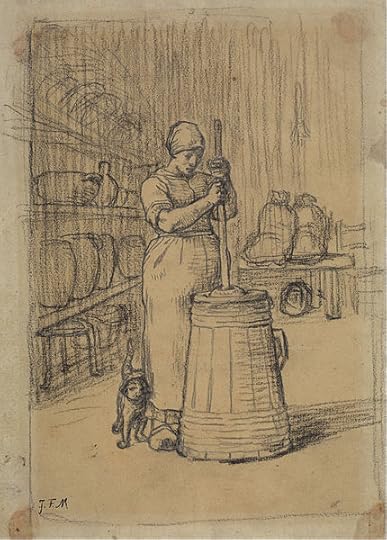

Folklore Snippets: Stealing Cream

Stealing Cream for Butter From Scandinavian Folklore, ed William Craigie 1896

Here’s a Norse version of the Sorcerer’s Apprentice, in which we learn about theft, greed, and the power of multiplication, and in which a young person learns to follow instructions carefully or rue the consequences…

Here’s a Norse version of the Sorcerer’s Apprentice, in which we learn about theft, greed, and the power of multiplication, and in which a young person learns to follow instructions carefully or rue the consequences…There was once a woman in Stödov on Helge-neas, who practised witchcraft. She had the custom, when she was about to make butter, of saying, “A spoonful of cream from every one in the county”; and in this way she always got her churn quite full of cream. One day it happened that she had an errand into town, just when they were about to churn, and said to the maid, “You can churn when I am away, but before you begin you must say, ‘A spoonful of cream form every one in the county’; I shall take care then that plenty of cream will come to you.” She then went away, and the maid began to churn but when she came to say the words that the witch had taught her, she thought that a spoonful from every one was so very little, so she said, “a pint of cream from every one in the county.”

Now she got cream, and that in plenty. The churn was filled, and the cream still continued to come, till at last the kitchen was half full of cream. When the woman returned home, the girl stood bailing the cream out at the kitchen door, and the witch was very angry that the maid had gone beyond her orders and asked for a pint instead of a spoonful, for now every one could easily see that cream had been stolen from them. After this the girl never got leave to make the butter by herself.

Picture credit: Study for Woman Churning Butter, Jean-Francois Millet, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Wikimedia Commons

Published on December 21, 2012 01:27