Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 34

August 6, 2012

Folklore snippets: 'Another Troy'?

Homes on the Great Blasket, Ida M Flower, c. 1920

Homes on the Great Blasket, Ida M Flower, c. 1920From ‘The Western Island’ by Robin Flower, Oxford 1944, an account of the writer’s experiences visiting and staying on the Great Blasket between 1910 and 1935. Until 1953, the inhabitants of Great Blasket Island formed the most westerly settlement in Ireland. This small fishing community of less than 150 people lived in little cottages perched on the relatively sheltered north-east shore. In 1953 the Irish Government evacuated the islanders.

A story from Tomás ó Crithin:

‘When I was a young man growing up, it was a different world from the world we have today. There was no silent drinking then into the tavern and out of it without a word said, but you would be walking the road and the tavern-door would open, and you would go in. There would be as many as twenty men in the room drinking, and every man that came in he would not go out without singing a song or telling a tale. …The country was full to the lid of songs and stories, and you would not put a stir out of you from getting up in the morning to lying down at night but you would meet a poet, man or woman, making songs on all that would be happening. It is not now as it was then, but it is like a sea on ebb, and only pools left here and there among the rocks. And it is a good thought of us to put down the songs and stories before they are lost from the world for ever.’

And so, he sitting on one side of the table, rolling a savoury sprig of dillisk round and round in his mouth to lend a salt flavour to his speech, and I diligently writing on the other side, the picture of the Island’s past grew from day to day under our hands. At times I would stop him as an unfamiliar world or strange twist of phrase struck across my ear, and he would courteously explain it… Thus on one occasion, the phrase ‘the treacherous horse that brought destruction on Troy’ came into a song.

‘And what horse was that?’ I said.

‘It was the horse of wood,’ he answered, ‘that was made to be given to the King that was over Troy. They took it with them and brought it into the middle of the city, and it was lovely to look upon. It was in that city Helen was, she that brought the world to death; every man that used to come with a host seeking her, there would go no man of them safe home without falling because of Helen before the city of Troy. It was said that the whole world would have fallen by reason of Helen that time if it had not been for the thought this man had, to give the horse of wood to the King. There was an opening in it unknown to all, two men in it, and it full of powder and shot. When the horse was in the middle of the city, and every one of them weary from looking at it, a night of the nights my pair opened the horse and out with them. They brought with them their share of powder and shot. They scattered it here and there through the city in the deep night; they set fire to it and left not a living soul in Troy that wasn’t burnt that night.’

Derelict homes on The Great Blasket Island, Co. Kerry, Ireland.

Derelict homes on The Great Blasket Island, Co. Kerry, Ireland.Picture credits:

Derelict homes on The Great Blasket Island, Co. Kerry, Ireland, photo by Cargoking. Wikimedia Commons

Published on August 06, 2012 01:15

August 3, 2012

The Master-Maid: the role of women and girls in fairyland

by Ellen Renner

Recently, during a school visit, an eleven-year-old boy said he found my book Castle of Shadows 'girly' and asked, 'Did I mean it to be that way?'

Recently, during a school visit, an eleven-year-old boy said he found my book Castle of Shadows 'girly' and asked, 'Did I mean it to be that way?'

I was, frankly, horrified. Castle of Shadows is about love and hate, power and powerlessness, politics and science. Charlie, the main character, is the least frilly princess imaginable. In a reversal of the fairy-tale tradition, she is the hero and her helper a boy. When I invited him to imagine the exact same sequence of events with a boy as the main character, my questioner had to admit that there was nothing intrinsically feminine in either plot or themes. It appeared that the thing preventing him from identifying with the story was that fact that it had a girl protagonist who, moreover, was a princess.

He went on to ask many more lively and interesting questions, but the incident remains with me as an example of the truism that, while girls will happily read books where the main character is a boy, the same cannot be said for boys. Which begs the question: Why?

Are girls innately more empathetic? Are there biological and evolutionary reasons which tend to make men see women as 'other', while women sometimes identify so strongly with those they love that they can lose their own sense of self? Or is the reason cultural: the fact that active female protagonists – female 'heroes' – are so hard to find in our stories and cultural myths? If the boy in that school had grown up with stories and cultural myths where 'heroes' are girls as often as boys, would he have had the same reaction to my book?

Castle of Shadows began as a fairy-tale: a missing queen, a forgotten princess, a mad king who neglects both daughter and kingdom, the corrupting desire for power. I was aware of these fairy-tale elements from the moment of inception and also of my own ambivalence towards them. I was particularly wary of having a princess for a main character. Fairy-tale princesses held little charm for me as a child.

I read mythology, folk lore and fairy-tales voraciously, yet certain tales felt inappropriate and even irritating long before I was capable of analysing why that might be. They annoyed me in the same way Barbie dolls did. These were the stories featuring passive girls, usually born or destined to become princesses, like Sleeping Beauty or Cinderella. Girls whose physical attractiveness was the sum of their identity; girls who were not so much protagonists as prizes.

I yearned for heroines I could identify with and aspire to be like. Girls who DID things. Who underwent hardship and suffering and overcame the odds by use of their own wit or courage. And I found Gerta in Andersen's The Snow Queen and the brave sister in the Grimms tale, The Six Swans. I found Gretel in Hansel and Gretel; Janet in Tam Lin; and the redoubtable, spendidly named Molly Whuppie – the female Jack who bests her giant. Molly may marry and disappear into 'happy-ever-after', but you know she will go on dominating life just the same.

I had a more complicated reaction, no doubt because of the darker themes of forced marriage and the bestial interpretation of male sexuality, to tales such as Mossy Coat, The Black Bull of Norroway, and East of the Sun, West of the Moon, but I still admired the courage and cleverness of the heroines. In these tales, a young woman is forced to perform nearly impossible tasks in order to recover a lost fiancé or husband, and sometimes their children. She succeeds with the help of magical advisers and gifts.

Similar, but missing out the forced marriage aspect, are versions of The Master-Maid as told by Andrew Lang in The Blue Fairy Book. This tale and its variants, including Sweetheart Roland, Nix-Nought-Nothing and The Battle of the Birds, are classified, by those who enjoy such things, as 'girl helps hero flee' (Arne-Thompson type 313). It's a strange classification, since the heroes in these stories are less interesting than the heroines. The 'helpers' are the true protagonists. These heroines have no advisers, are given no gifts. They succeed by dint of their own magical abilities, courage and cleverness. These are witches, one and all; daughters of ogres or giants, who wield far more power than than their mortal lovers.

In The Master-Maid, the king's youngest son goes off into the world to seek his fortune and takes employment with an evil giant. The giant sets him three impossible tasks which the prince is only able to complete by following the advice of the Master-Maid. 'Master' here means skilled, and the young woman is obviously a magician employed as a servant by the giant. Their relationship is never explained. (In some versions, she is the Giant's daughter.) The giant, suspecting her involvement, orders her to kill the prince and cook him for his supper. Master-Maid pretends to obey, but when the giant falls asleep, she puts her plan into action:

So the Master-Maid took a knife, and cut the Prince's little finger, and dropped three drops of blood upon a wooden stool; then she took all the old rags, and shoe-soles, and all the rubbish she could lay hands on, and put them in the cauldron; and then she filled a chest with gold dust, and a lump of salt, and a water-flask which was hanging by the door, and she also took with her a golden apple, and two gold chickens; and then she and the Prince went away with all the speed they could ...

Of course, the giant wakes, is fooled for a short time by the three drops of blood, who answer his calls in the Master-Maid's voice. He tastes the mess in the cauldron; the game is up and he gives chase. This pursuit was always my favourite part, but I prefer the version in The Battle of the Birds, taken from The Well at the World's End, Folk Tales of Scotland retold by Norah and William Montgomerie:

...the giant jumped out of bed and, finding the Prince and his bride had gone, ran after them.

In the mouth of the day, the giant's daughter said her father's breath was burning her neck.

'Quickly, put your hand in the grey filly's ear!' said she.

'There's a twig of blackthorn,' said he.

'Throw it behind you!' said she.

No sooner had he done this than there sprang up twenty miles of blackthorn wood, so thick that a weasel could not go through.

The giant is delayed while he chops the wood down, but he's soon after them again:

'In the heat of the day, the giant's daughter said: 'I feel my father's breath burning my neck. Put your hand in the filly's ear, and whatever you find there, throw it behind you!'

He found a splinter of grey stone, and threw it behind him. At once there sprang up twenty miles of grey rock, high and broad as a range of mountains. The giant came full pelt after them, but past the rock he could not go.

He is delayed again as he digs through the rock, but the lovers' respite is brief and she once more instructs him to reach into the filly's ear:

This time he found a thimble of water. He threw it behind him, and at once there was a fresh-water loch, twenty miles in length and breadth.

The giant came on, but was running so quickly he did not stop till he was in the middle of the loch, where he sank and did not come up.

The giant defeated, the lovers reach the Prince's home, but their trouble is not over. The Master-Maid warns him: '... if you go home to the King's palace you will forget me, I forsee that.' But the stubborn Prince insists. And as though he were a mortal venturing into the fairy realm, she instructs him not to speak to anyone there, and especially not to eat any food, or else he will forget her. Of course, he eats and forgets. In the second half of the tale, she must use all her magic to cancel the spell and win back her beloved.

Most tales about the winning back of a lover or husband put the blame for his forgetfulness onto women: the mother and daughter troll; the hag and the enchantress. Only in darker versions of Sweetheart Roland do we find the heroine killing both rival witch and straying betrothed. In all other cases, it is only the rival women who are killed. From The Master-Maid:

So the Prince knew her again, and you may imagine how delighted he was. He ordered the troll-witch who had rolled the apple to him to be torn in pieces between four-and-twenty horses, so that not a bit of her was left ...

This is the first mention in the story that the young lady is a troll. It seems rather stiff punishment for proffering an apple to a man who takes your fancy, but such are the rules of fairy-tales.

As for hags, in these as in most fairy-tales, elderly women come in for harsh treatment, which doubtless says much about the social attitudes of the times in which they were written. The Master-Maid needs somewhere to live in order to win back her man, and when she spies a little hut in a small wood near the King's palace, she more or less moves in:

The hut belonged to an old crone, who was also an ill-tempered and malicious troll. At first she would not let the Master-Maid remain with her; but at last, after a long time, by means of good words and good payment, she obtained leave.

The crone is less pleased when the Master-maid starts redecorating:

The old crone did not like this either. She scowled, and was very cross, but the Master-maid did not trouble herself about that. She took out her chest of gold, and flung a handful of it or so into the fire, and the gold boiled up and poured out over the whole of the hut, until every part of it both inside and out was gilded. But when the gold began to bubble up the old hag grew so terrified that she fled as if the Evil One himself were pursuing her, and she did not remember to stoop down as she went through the doorway, and so she split her head and died.

Such is the fate of hags and crones. They are either trolls to be killed or, more rarely, advisers whom the heroine would be wise to listen to.

The best of all hags must be Baba Yaga, as powerful as she is terrifying; who eats stupid girls but offers the wise and brave ones power and life. Lucy Coats has done an excellent post on Baba Yaga and my favourite fairy-tale heroine, Vasilisa.

I can't leave hags behind without mentioning a modern fairy-tale, the brilliant 'Howl's Moving Castle', in which Diana Wynne Jones takes the motif of the fairy-tale hag and turns it on its head from the inspired moment in the book when she transforms her protagonist into an aged crone, which she remains for much of the novel. Wynne Jones knows, as all women do, that there is little difference between heroine and crone. Time's slight-of-hand – a malicious magic – and the princess becomes the hag.

In most fairy-tales, the heroine's ultimate reward is marriage, whereupon her adventures cease. But then, so do the hero's.

As for my own heroine, the princess Charlotte, I grew to know her better as I wrote the book. Like the Master-Maid and Molly Whuppie, she is girl who knows her own mind. She is, like all girls, the heroine of her own life, not merely a prize or a helper, and her story needed to reflect that reality. Castle of Shadows is no fairy-tale. Charlie resembles the real life queen, Elizabeth the First, far more than she ever will Cinderella or Sleeping Beauty. In the passing of time, she will grow to become a wise and powerful crone. And like that monarch (for Charlie is a queen now too), she may be destined never to know what happens in the land of 'happy-ever-after'.

Ellen Renner was born in the USA, in the Ozark Mountains of Missouri, but came to England looking for adventure, married here, and now lives in an old house in Devon with her husband and son. Her first book, ‘Castle of Shadows’ (2010) is set in an alternate world similar to nineteenth century England, in a city not unlike London. Young Charlie (Charlotte) is the Princess of Quale. Years ago her mother the Queen – a notable scientist – mysteriously vanished. Her eccentric father the King spends all his time building ever more elaborate card-castles. Neglected and hungry, bullied by the housekeeper, Charlie runs wild and scrambles at will over the roofs of the castle, her only friend the gardener’s boy, Toby – until the day when the suavely intelligent Prime Minister, Alistair Windlass, begins to take an interest in her. But is he a true friend, or does he have some other motive for turning Charlie back into an educated, well-dressed, 'proper' princess?

‘City of Thieves’ continues Charlie’s story, with further focus on her friend Toby and his efforts to escape both the family of thieves who claim him as their own, and the machinations of the sinister yet strangely attractive Windlass. Quale is in deadly danger – and Charlie and Toby are forced to take opposite sides.

The plotting is delightfully complex: more twists and turns than a chain-link fence. These are books hard to categorise – a fantasy world with no magic, a hint of steam-punk, lots of interesting politics, some fearsome inventions, and brilliant characters you really care about. Ellen’s writing is reminiscent of Joan Aiken’s. If only one could introduce characters from one author’s books to another’s! How I’d love to see tough, passionate Charlie meet Aiken’s irrepressible gamine, Dido Twite...

Picture credits:

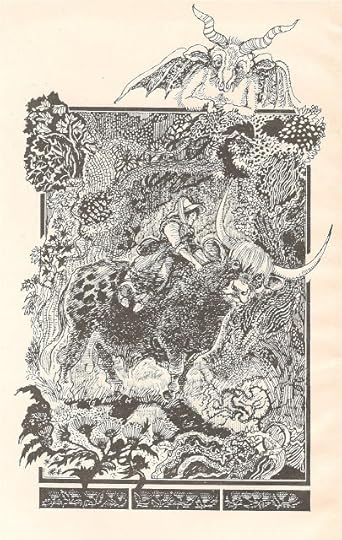

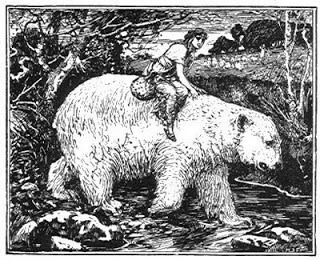

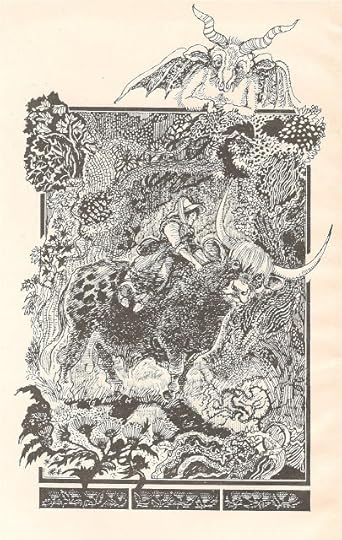

'The Black Bull of Norroway', by John Lawrence, from 'The Blue Fairy Book', 1975'Molly Whuppie' by unknown 19th century (?) illustrator at this link: http://nota.triwe.net/lib/tales16.htm

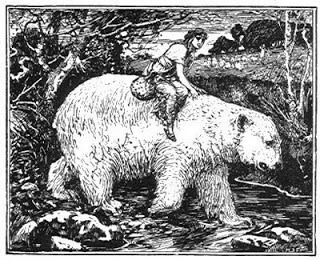

'East of the Sun, West of the Moon' by Henry Justice Ford

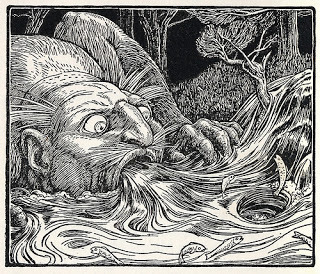

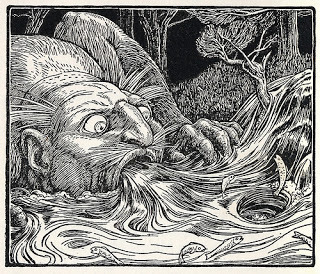

'The Giant in The Master Maid' by John D Batten

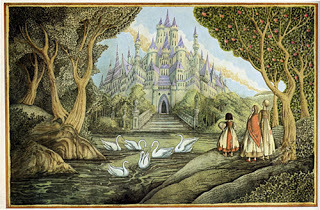

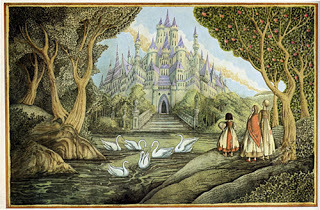

'Mollie Whuppie and her Sisters' by Errol le Cain

Recently, during a school visit, an eleven-year-old boy said he found my book Castle of Shadows 'girly' and asked, 'Did I mean it to be that way?'

Recently, during a school visit, an eleven-year-old boy said he found my book Castle of Shadows 'girly' and asked, 'Did I mean it to be that way?'I was, frankly, horrified. Castle of Shadows is about love and hate, power and powerlessness, politics and science. Charlie, the main character, is the least frilly princess imaginable. In a reversal of the fairy-tale tradition, she is the hero and her helper a boy. When I invited him to imagine the exact same sequence of events with a boy as the main character, my questioner had to admit that there was nothing intrinsically feminine in either plot or themes. It appeared that the thing preventing him from identifying with the story was that fact that it had a girl protagonist who, moreover, was a princess.

He went on to ask many more lively and interesting questions, but the incident remains with me as an example of the truism that, while girls will happily read books where the main character is a boy, the same cannot be said for boys. Which begs the question: Why?

Are girls innately more empathetic? Are there biological and evolutionary reasons which tend to make men see women as 'other', while women sometimes identify so strongly with those they love that they can lose their own sense of self? Or is the reason cultural: the fact that active female protagonists – female 'heroes' – are so hard to find in our stories and cultural myths? If the boy in that school had grown up with stories and cultural myths where 'heroes' are girls as often as boys, would he have had the same reaction to my book?

Castle of Shadows began as a fairy-tale: a missing queen, a forgotten princess, a mad king who neglects both daughter and kingdom, the corrupting desire for power. I was aware of these fairy-tale elements from the moment of inception and also of my own ambivalence towards them. I was particularly wary of having a princess for a main character. Fairy-tale princesses held little charm for me as a child.

I read mythology, folk lore and fairy-tales voraciously, yet certain tales felt inappropriate and even irritating long before I was capable of analysing why that might be. They annoyed me in the same way Barbie dolls did. These were the stories featuring passive girls, usually born or destined to become princesses, like Sleeping Beauty or Cinderella. Girls whose physical attractiveness was the sum of their identity; girls who were not so much protagonists as prizes.

I yearned for heroines I could identify with and aspire to be like. Girls who DID things. Who underwent hardship and suffering and overcame the odds by use of their own wit or courage. And I found Gerta in Andersen's The Snow Queen and the brave sister in the Grimms tale, The Six Swans. I found Gretel in Hansel and Gretel; Janet in Tam Lin; and the redoubtable, spendidly named Molly Whuppie – the female Jack who bests her giant. Molly may marry and disappear into 'happy-ever-after', but you know she will go on dominating life just the same.

I had a more complicated reaction, no doubt because of the darker themes of forced marriage and the bestial interpretation of male sexuality, to tales such as Mossy Coat, The Black Bull of Norroway, and East of the Sun, West of the Moon, but I still admired the courage and cleverness of the heroines. In these tales, a young woman is forced to perform nearly impossible tasks in order to recover a lost fiancé or husband, and sometimes their children. She succeeds with the help of magical advisers and gifts.

Similar, but missing out the forced marriage aspect, are versions of The Master-Maid as told by Andrew Lang in The Blue Fairy Book. This tale and its variants, including Sweetheart Roland, Nix-Nought-Nothing and The Battle of the Birds, are classified, by those who enjoy such things, as 'girl helps hero flee' (Arne-Thompson type 313). It's a strange classification, since the heroes in these stories are less interesting than the heroines. The 'helpers' are the true protagonists. These heroines have no advisers, are given no gifts. They succeed by dint of their own magical abilities, courage and cleverness. These are witches, one and all; daughters of ogres or giants, who wield far more power than than their mortal lovers.

In The Master-Maid, the king's youngest son goes off into the world to seek his fortune and takes employment with an evil giant. The giant sets him three impossible tasks which the prince is only able to complete by following the advice of the Master-Maid. 'Master' here means skilled, and the young woman is obviously a magician employed as a servant by the giant. Their relationship is never explained. (In some versions, she is the Giant's daughter.) The giant, suspecting her involvement, orders her to kill the prince and cook him for his supper. Master-Maid pretends to obey, but when the giant falls asleep, she puts her plan into action:

So the Master-Maid took a knife, and cut the Prince's little finger, and dropped three drops of blood upon a wooden stool; then she took all the old rags, and shoe-soles, and all the rubbish she could lay hands on, and put them in the cauldron; and then she filled a chest with gold dust, and a lump of salt, and a water-flask which was hanging by the door, and she also took with her a golden apple, and two gold chickens; and then she and the Prince went away with all the speed they could ...

Of course, the giant wakes, is fooled for a short time by the three drops of blood, who answer his calls in the Master-Maid's voice. He tastes the mess in the cauldron; the game is up and he gives chase. This pursuit was always my favourite part, but I prefer the version in The Battle of the Birds, taken from The Well at the World's End, Folk Tales of Scotland retold by Norah and William Montgomerie:

...the giant jumped out of bed and, finding the Prince and his bride had gone, ran after them.

In the mouth of the day, the giant's daughter said her father's breath was burning her neck.

'Quickly, put your hand in the grey filly's ear!' said she.

'There's a twig of blackthorn,' said he.

'Throw it behind you!' said she.

No sooner had he done this than there sprang up twenty miles of blackthorn wood, so thick that a weasel could not go through.

The giant is delayed while he chops the wood down, but he's soon after them again:

'In the heat of the day, the giant's daughter said: 'I feel my father's breath burning my neck. Put your hand in the filly's ear, and whatever you find there, throw it behind you!'

He found a splinter of grey stone, and threw it behind him. At once there sprang up twenty miles of grey rock, high and broad as a range of mountains. The giant came full pelt after them, but past the rock he could not go.

He is delayed again as he digs through the rock, but the lovers' respite is brief and she once more instructs him to reach into the filly's ear:

This time he found a thimble of water. He threw it behind him, and at once there was a fresh-water loch, twenty miles in length and breadth.

The giant came on, but was running so quickly he did not stop till he was in the middle of the loch, where he sank and did not come up.

The giant defeated, the lovers reach the Prince's home, but their trouble is not over. The Master-Maid warns him: '... if you go home to the King's palace you will forget me, I forsee that.' But the stubborn Prince insists. And as though he were a mortal venturing into the fairy realm, she instructs him not to speak to anyone there, and especially not to eat any food, or else he will forget her. Of course, he eats and forgets. In the second half of the tale, she must use all her magic to cancel the spell and win back her beloved.

Most tales about the winning back of a lover or husband put the blame for his forgetfulness onto women: the mother and daughter troll; the hag and the enchantress. Only in darker versions of Sweetheart Roland do we find the heroine killing both rival witch and straying betrothed. In all other cases, it is only the rival women who are killed. From The Master-Maid:

So the Prince knew her again, and you may imagine how delighted he was. He ordered the troll-witch who had rolled the apple to him to be torn in pieces between four-and-twenty horses, so that not a bit of her was left ...

This is the first mention in the story that the young lady is a troll. It seems rather stiff punishment for proffering an apple to a man who takes your fancy, but such are the rules of fairy-tales.

As for hags, in these as in most fairy-tales, elderly women come in for harsh treatment, which doubtless says much about the social attitudes of the times in which they were written. The Master-Maid needs somewhere to live in order to win back her man, and when she spies a little hut in a small wood near the King's palace, she more or less moves in:

The hut belonged to an old crone, who was also an ill-tempered and malicious troll. At first she would not let the Master-Maid remain with her; but at last, after a long time, by means of good words and good payment, she obtained leave.

The crone is less pleased when the Master-maid starts redecorating:

The old crone did not like this either. She scowled, and was very cross, but the Master-maid did not trouble herself about that. She took out her chest of gold, and flung a handful of it or so into the fire, and the gold boiled up and poured out over the whole of the hut, until every part of it both inside and out was gilded. But when the gold began to bubble up the old hag grew so terrified that she fled as if the Evil One himself were pursuing her, and she did not remember to stoop down as she went through the doorway, and so she split her head and died.

Such is the fate of hags and crones. They are either trolls to be killed or, more rarely, advisers whom the heroine would be wise to listen to.

The best of all hags must be Baba Yaga, as powerful as she is terrifying; who eats stupid girls but offers the wise and brave ones power and life. Lucy Coats has done an excellent post on Baba Yaga and my favourite fairy-tale heroine, Vasilisa.

I can't leave hags behind without mentioning a modern fairy-tale, the brilliant 'Howl's Moving Castle', in which Diana Wynne Jones takes the motif of the fairy-tale hag and turns it on its head from the inspired moment in the book when she transforms her protagonist into an aged crone, which she remains for much of the novel. Wynne Jones knows, as all women do, that there is little difference between heroine and crone. Time's slight-of-hand – a malicious magic – and the princess becomes the hag.

In most fairy-tales, the heroine's ultimate reward is marriage, whereupon her adventures cease. But then, so do the hero's.

As for my own heroine, the princess Charlotte, I grew to know her better as I wrote the book. Like the Master-Maid and Molly Whuppie, she is girl who knows her own mind. She is, like all girls, the heroine of her own life, not merely a prize or a helper, and her story needed to reflect that reality. Castle of Shadows is no fairy-tale. Charlie resembles the real life queen, Elizabeth the First, far more than she ever will Cinderella or Sleeping Beauty. In the passing of time, she will grow to become a wise and powerful crone. And like that monarch (for Charlie is a queen now too), she may be destined never to know what happens in the land of 'happy-ever-after'.

Ellen Renner was born in the USA, in the Ozark Mountains of Missouri, but came to England looking for adventure, married here, and now lives in an old house in Devon with her husband and son. Her first book, ‘Castle of Shadows’ (2010) is set in an alternate world similar to nineteenth century England, in a city not unlike London. Young Charlie (Charlotte) is the Princess of Quale. Years ago her mother the Queen – a notable scientist – mysteriously vanished. Her eccentric father the King spends all his time building ever more elaborate card-castles. Neglected and hungry, bullied by the housekeeper, Charlie runs wild and scrambles at will over the roofs of the castle, her only friend the gardener’s boy, Toby – until the day when the suavely intelligent Prime Minister, Alistair Windlass, begins to take an interest in her. But is he a true friend, or does he have some other motive for turning Charlie back into an educated, well-dressed, 'proper' princess?

‘City of Thieves’ continues Charlie’s story, with further focus on her friend Toby and his efforts to escape both the family of thieves who claim him as their own, and the machinations of the sinister yet strangely attractive Windlass. Quale is in deadly danger – and Charlie and Toby are forced to take opposite sides.

The plotting is delightfully complex: more twists and turns than a chain-link fence. These are books hard to categorise – a fantasy world with no magic, a hint of steam-punk, lots of interesting politics, some fearsome inventions, and brilliant characters you really care about. Ellen’s writing is reminiscent of Joan Aiken’s. If only one could introduce characters from one author’s books to another’s! How I’d love to see tough, passionate Charlie meet Aiken’s irrepressible gamine, Dido Twite...

Picture credits:

'The Black Bull of Norroway', by John Lawrence, from 'The Blue Fairy Book', 1975'Molly Whuppie' by unknown 19th century (?) illustrator at this link: http://nota.triwe.net/lib/tales16.htm

'East of the Sun, West of the Moon' by Henry Justice Ford

'The Giant in The Master Maid' by John D Batten

'Mollie Whuppie and her Sisters' by Errol le Cain

Published on August 03, 2012 00:27

July 31, 2012

Folklore Snippets: Giant Women and Hellish Boys

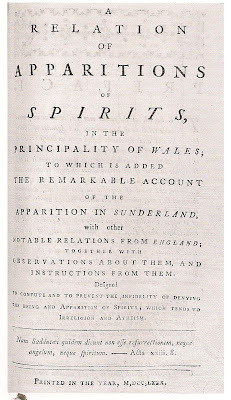

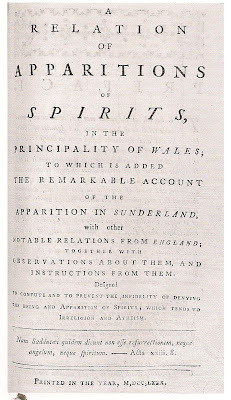

Here are three folklore snippets from a wonderful book called 'The Appearance of Evil: Apparitions of Spirits in Wales': edited with an introduction by John Harvey and published by the University of Wales Press, 2003.

Here are three folklore snippets from a wonderful book called 'The Appearance of Evil: Apparitions of Spirits in Wales': edited with an introduction by John Harvey and published by the University of Wales Press, 2003.Edmund Jones (1702-93) was an 18th century Welsh Dissenter, a minister and preacher who travelled 'on horseback and on foot, throughout Wales and his seventy years of service across, what he considered, a cursed and pestilent landscape infested with the emissaries of darkness.' His book, A Relation of Apparitions of Spirits in the Principality of Wales, published in 1780, was not written from what we now consider the usual motives for collecting and preserving folk tales and traditions. Instead, Jones regarded the tales and incidents he collected (and frequently also experienced) as evidence of the genuine existence and interference of the supernatural and diabolical in everyday life - and hence, also, evidence for the truth of the gospels. (His argument, roughly, was: if bad spirits exist, as stated in the Bible, then so does God.)

I have given the extracts titles. All page numbers are taken from the 2003 edition.

THE HELLISH BOY

About the year 1748, J W James was going by night from Bedwas (with a young woman whom he pretended to court) towads Risca church-wakes on horseback. Before they came over against Certwyn Machen hill (the east side of it facing the parish of Risca) they could see the resemblance of a boy going before them part of the way. They suspected, by something in the appearance, that it was not a real boy - as, indeed, it was not - but a hellish dangerous boy, as it soon appeared. For while they looked upon it, they could see it suddenly putting its head between its legs and, transforming into a ball of light, tumbling a steep way towards the Certwyn, which is the top of the high Machen mountain - it being as easy for a spirit to go up as to come downhill. (p 103)

THE GIANT WOMAN Once, coming home at night from Abergavenny, Thomas Miles Harry was much oppressed with fears (as is usually the case before the appearance of evil spirits) in the way, when near home. His horse took fright, it seeing something he did not, and ran violently with him towards the house. Nor did Thomas’s fear cease when he was by the house. He was afraid to look about (expecting to see somewhat) and hastened to unsaddle his horse. But happening to cast his eye towards the other end of the years, he saw the appearance of a woman so prodigiously tall as to be about half as high as the tall beech trees at the other side of the yard. Glad was he of a house to enter in and rest.(p 77)

THE FAIRY FUNERALA certain man in a field, burning turfs, saw the fairies coming through the field where he lay blowing the fire in one of the pits. They went by like a burial, imitating the singing of psalms as they went, and, doubtless, the very tune sung at the approaching funeral. One of them leaped over his legs. He rose up to see where they would go, and followed them into a field that led into a wood. Soon after, a real burial came through the field, and he lay down by the pit of turfs to see what they would do. One of the company actually leaped over his legs in passing by, just as the fairies had done before. They also sung psalms at the burial, as the fairies foreshadowed.(p 58)

Published on July 31, 2012 02:43

Folktale Snippets: Giant Women and Hellish Boys

Here are three folklore snippets from a wonderful book called 'The Appearance of Evil: Apparitions of Spirits in Wales': edited with an introduction by John Harvey and published by the University of Wales Press, 2003.

Here are three folklore snippets from a wonderful book called 'The Appearance of Evil: Apparitions of Spirits in Wales': edited with an introduction by John Harvey and published by the University of Wales Press, 2003.Edmund Jones (1702-93) was an 18th century Welsh Dissenter, a minister and preacher who travelled 'on horseback and on foot, throughout Wales and his seventy years of service across, what he considered, a curse and pestilent landscape infested with the emissaries of darkness.' His book, A Relation of Apparitions of Spirits in the Principality of Wales, published in 1780, was not written from what we now consider the usual motives for collecting and preserving folk tales and traditions. Instead, Jones regarded the tales and incidents he collected (and frequently also experienced) as evidence of the genuine existence and interference of the supernatural and diabolical in everyday life - and hence, also, evidence for the truth of the gospels. (His argument, roughly, was: if bad spirits exist, as stated in the Bible, then so does God.)

I have given the extracts titles. All page numbers are taken from the 2003 edition.

THE HELLISH BOY

About the year 1748, J W James was going by night from Bedwas (with a young woman whom he pretended to court) towads Risca church-wakes on horseback. Before they came over against Certwyn Machen hill (the east side of it facing the parish of Risca) they could see the resemblance of a boy going before them part of the way. They suspected, by something in the appearance, that it was not a real boy - as, indeed, it was not - but a hellish dangerous boy, as it soon appeared. For while they looked upon it, they could see it suddenly putting its head between its legs and, transforming into a ball of light, tumbling a sttep way towards the Certwyn, which is the top of the high Machen mountain - it being as easy for a spirit to go up as to come downhill. (p 103)

THE GIANT WOMAN Once, coming home at night from Abergavenny, Thomas Miles Harry was much oppressed with fears (as is usually the case before the appearance of evil spirits) in the way, when near home. His horse took fright, it seeing something her did not, and ran violently with him towards the house. Nor did Thomas’s fear cease when he was by the house. He was afraid to look about (expecting to see somewhat) and hastened to unsaddle his horse. But happening to cast his eye towards the other end of the years, he saw the appearance of a woman so prodigiously tall as to be about half as high as the tall beech trees at the other side of the yard. Glad was he of a house to enter in and rest.(p 77)

THE FAIRY FUNERALA certain man in a field, burning turfs, saw the fairies coming through the field where he lay blowing the fire in one of the pits. They went by like a burial, imitating the singing of psalms as they went, and, doubtless, the very tune sung at the approaching funeral. One of them leaped over his legs. he rose up to see where they would go, and followed them into a field that led into a wood. Soon after, a real burial came through the field, and he lay down by the pit of turfs to see what they would do. One of the company actually leaped over his legs in passing by, just as the fairies had done before. They also sung psalms at the burial, as the fairies foreshadowed.(p 58)

Published on July 31, 2012 02:43

July 30, 2012

Richard Coeur-de-Lion - Hollywood Hero or Sneering Villain?

You'll find me over at the History Girls today, wondering how on earth Richard the Lionheart has managed to go down in history as an English Hero (with a statue outside the Houses of Parliament, no less). Just click on this link.

Published on July 30, 2012 03:38

July 27, 2012

Tam Lin

by Gillian Philip

Carterhaugh, a farm on the Buccleuch Estate, here seen across the Ettrick Water. As a child I don’t think I was aware of the story of TAM LIN, one of many mortal men stolen away by the Queen of the Faeries. I’m not even sure when I first read or heard such tales; stories of the faery people were simply a kind of background music that I gradually noticed and that came to fascinate me. Tam Lin is just one variation on a theme that sometimes has a happy ending, more often less so: a mortal – more often than not a man – is foolish or brave or naive enough to go away with the faeries.

Carterhaugh, a farm on the Buccleuch Estate, here seen across the Ettrick Water. As a child I don’t think I was aware of the story of TAM LIN, one of many mortal men stolen away by the Queen of the Faeries. I’m not even sure when I first read or heard such tales; stories of the faery people were simply a kind of background music that I gradually noticed and that came to fascinate me. Tam Lin is just one variation on a theme that sometimes has a happy ending, more often less so: a mortal – more often than not a man – is foolish or brave or naive enough to go away with the faeries.

There’s a recurring notion that once involved with the People of Peace, you’re going to need all your wits, courage and – usually – the help of a friend to get away. More often than not, even all of those aren’t enough, and that makes many of the stories melancholy.

Tam Lin is a little different, and that’s why I’m fond of it. The traditional ballad begins with a warning not to go to the woods of Carterhaugh, because young Tam Lin is there – a man who was taken by the Queen of the Faeries, who now protects their sacred woods, and who will demand a penalty of anyone who trespasses. Earlier versions are pretty clear about what that penalty will be... and when young Janet, whose father nominally owns the wood, dares to go there to pick roses, she comes back not just wildly in love, but pregnant.

Luckily the love is mutual, and Tam explains to Janet that the Queen of Elfland saved and took him when he fell from his horse in these woods. He is her prized mortal lover, but every seven years the Queen must pay a tithe of souls to Hell, and he fears that this Halloween, he will be the tithe. Janet can save him, and free him from the Queen’s thrall, but it will take huge courage. She must wait in the trees till she sees the faery folk ride in procession through the woods. She must let the first two horses pass, but when the third – a milk-white steed – appears, she must pull him down from it.

The faeries, he warns her, will be enraged, and now will come the hard part. She has to hold onto him whatever happens, though they’ll morph him into many hideous forms to try to make her let go. Sure enough, when she does as he tells her and pulls him from his horse, he is turned into a snake, a newt, a bear, a lion, red-hot iron, then burning lead. Through all the transformations, Janet holds on for dear life, and at the touch of the burning lead, forewarned by Tam, she tips her burden into the water of the nearby well. Tam climbs out, returned to his human form and free of servitude to the Queen. Though the Queens rails about the ‘theft’ of her dearest mortal, she sullenly admits defeat, and the young couple live, as they should, happily ever after.

Thomas Rhymer & the Queen of Elphame by Kate GreenawayThe story has many parallels and similarities in other traditions and tales – Thomas Rhymer, Cupid & Psyche, Childe Rowland, and even Beauty and the Beast: with the last, for instance, there’s the forbidden forest and the rose motif; the threatening inhuman figure with whom the heroine falls in love; his former identity as a noble young lord; and the fact that the heroine must go through dangers and horrors to rescue him. (There’s a theory that Beauty & the Beast is a later bowdlerisation of the Tam Lin story, leaving out the sex. I’ve always rather liked the Disney version more than their other ‘fairytales’, not least for its gutsy heroine, but it’s difficult to imagine it including ravishing among the roses followed by pregnancy...)

Thomas Rhymer & the Queen of Elphame by Kate GreenawayThe story has many parallels and similarities in other traditions and tales – Thomas Rhymer, Cupid & Psyche, Childe Rowland, and even Beauty and the Beast: with the last, for instance, there’s the forbidden forest and the rose motif; the threatening inhuman figure with whom the heroine falls in love; his former identity as a noble young lord; and the fact that the heroine must go through dangers and horrors to rescue him. (There’s a theory that Beauty & the Beast is a later bowdlerisation of the Tam Lin story, leaving out the sex. I’ve always rather liked the Disney version more than their other ‘fairytales’, not least for its gutsy heroine, but it’s difficult to imagine it including ravishing among the roses followed by pregnancy...)

The reversal of ‘traditional’ fairytale roles is one of the most appealing aspects of Tam Lin. Tam is effectively helpless before the Faery Queen, though there’s nothing emasculated about him. It’s Janet who must free him, and she’s willing to undergo torments to do so. The fact that it all ends happily is unusual for a tale of the Faery Court.

Belief in faeries is still strong in areas of Scotland, which isn’t wholly surprising. There are still places wild enough for the barriers between reality and ‘something else’ to seem remarkably, tangibly thin (not least the haunting Isle of Colonsay, whose former laird MacPhie seems to have had an unusual number of run-ins with the people of the Otherworld). Superstitions still exist quite strongly (my mother-in-law’s gardener swore no good would come of her telling him to cut down a rowan tree, and blamed the foul deed immediately when the house subsequently burned down). At a relative’s baptism I remember being quite sure that an aged aunt’s refusal to drink from a green cup was down to an unwillingness to offend the faeries. As it turned out the prejudice was an extreme sectarian one, but I can’t believe the two aren’t linked, somehow and somewhere in the past.

As for the disappearance of unfortunate mortals, there are surprisingly recent tales. Tomnahurich is a hill in the middle of Inverness that’s long been associated with the Otherworld. A local story tells of two buskers, dressed in kilts and carrying pipes (all perfectly normal) who seemed so disoriented and terrified among the traffic that they spent a night in the police cells. When they were brought before the sheriff next day – luckily a Gaelic speaker, since they could speak nothing else – they explained that their panic was down to the world seeming to have changed a great deal since last night, when they were offered good money to play at a gathering of lords and ladies beneath Tomnahurich hill.

At a loss, the sheriff returned them for the time being to the cells, where a minister was summoned to the disturbed young men. As soon as he began to pray, and God’s name was mentioned, the young men, their instruments, and their payment all crumbled to dust.

It’s a fanciful story, and appears in many forms over the centuries, but in wilder landscapes it’s not hard to imagine another barely-seen world, repressed (perhaps temporarily...) by modernity and religion. Maybe that’s why the stories and their attached superstitions are resilient enough to survive into the contemporary world.

Or possibly it’s because the fairy stories are so entangled with religion and superstition and the beliefs of even more ancient times. The Fairy Hill of Aberfoyle in Perthshire is believed to house the spirits of the local dead, in a way that echoes the far older beliefs of those who buried their dead in chambered cairns. Catherine Czerkawska’s play The Secret Commonwealth is the tale of Aberfoyle minister Robert Kirk, who wrote a book of the same title, and whose knowledge was thought to come straight from the faeries themselves. He’s another one who meddled with them at his own peril: angry at his betrayal of their secrets, the faeries were said to have faked his death while abducting him to the Otherworld. He came to his cousin in a dream, telling him of his captivity and promising to appear at his own funeral – at which moment the cousin must throw a knife over his head to free him. Kirk duly appeared – but alas, the cousin was too gobsmacked to perform the required act, and the minister was never seen again.

It’s a chilling and wonderful story, but in Czerkawska’s play it’s used also as a metaphor for the loss of the ancient beliefs, the gradual withdrawal of an older tradition before the Christian ascendancy. What’s so fascinating about the fairy traditions is the way they were not discarded, but woven into the new beliefs: loathed by the Church, becoming associated with the devil and necromancy – but never wholly dying out.

Yet that mingling isn’t all bad. One of the loveliest cross-traditions, and my favourite, is the one – varying from region to region – that says the faeries are the rebel angels. Thrown out of Paradise by an angry God, the angels that fell into the sea became seals and seal people. The ones that were caught in the sky as they fell became the Merry Dancers, the Northern Lights. And the ones that fell on land? They became the Faeries.

Gillian Philip writes across genres: ‘anything that comes into my head, including fantasy, crime, science fiction and horror’. 'Bad Faith' is a Scottish-set dystopia about a society ruled by a tight-minded religious elite, and ‘Crossing the Line’ is a hard-edged thriller with a hint of the supernatural. As Gabriella Poole she has written the 'Darke Academy' series for Hothouse.

Gillian’s 'Rebel Angels' series ('Firebrand', 'Bloodstone', and - out in August - 'Wolfsbane') have to be some of the best new fantasies of recent years. Beginning in the 16th century at a time of witch hunts and burnings, it follows the fortunes of Seth MacGregor, bastard prince of the Scottish faeries, the Sithe, and an attractive hero in every sense of the word: lover, warrior, and owner of a sinister and beautiful waterhorse from the loch. The books are rooted in the history and folklore of Scotland, and quite unflinching about the cruelty and hardship of the times. The Sithe are ruled by a queen, Kate NicNiven, who is volatile, cruel and devious in the best traditions of fairy queens, and who deliberately stretches the loyalty of her subjects, Seth and his brother Conan included, almost to breaking point. There’s a protecting Veil between the land of the Sithe and the mortal world, and Kate wants to tear it away. And she invokes the help of some hauntingly unpleasant creatures called the Lammyr…

Picture credits: Carterhaugh: The copyright on this image is owned by Richard Webb and is licensed for reuse under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 license.Thomas the Rhymer & the Queen of Elphame by Kate Greenaway, d. 1901. Wikimedia Commons. Cleaned up from a scan found at Winterspells

Carterhaugh, a farm on the Buccleuch Estate, here seen across the Ettrick Water. As a child I don’t think I was aware of the story of TAM LIN, one of many mortal men stolen away by the Queen of the Faeries. I’m not even sure when I first read or heard such tales; stories of the faery people were simply a kind of background music that I gradually noticed and that came to fascinate me. Tam Lin is just one variation on a theme that sometimes has a happy ending, more often less so: a mortal – more often than not a man – is foolish or brave or naive enough to go away with the faeries.

Carterhaugh, a farm on the Buccleuch Estate, here seen across the Ettrick Water. As a child I don’t think I was aware of the story of TAM LIN, one of many mortal men stolen away by the Queen of the Faeries. I’m not even sure when I first read or heard such tales; stories of the faery people were simply a kind of background music that I gradually noticed and that came to fascinate me. Tam Lin is just one variation on a theme that sometimes has a happy ending, more often less so: a mortal – more often than not a man – is foolish or brave or naive enough to go away with the faeries.There’s a recurring notion that once involved with the People of Peace, you’re going to need all your wits, courage and – usually – the help of a friend to get away. More often than not, even all of those aren’t enough, and that makes many of the stories melancholy.

Tam Lin is a little different, and that’s why I’m fond of it. The traditional ballad begins with a warning not to go to the woods of Carterhaugh, because young Tam Lin is there – a man who was taken by the Queen of the Faeries, who now protects their sacred woods, and who will demand a penalty of anyone who trespasses. Earlier versions are pretty clear about what that penalty will be... and when young Janet, whose father nominally owns the wood, dares to go there to pick roses, she comes back not just wildly in love, but pregnant.

Luckily the love is mutual, and Tam explains to Janet that the Queen of Elfland saved and took him when he fell from his horse in these woods. He is her prized mortal lover, but every seven years the Queen must pay a tithe of souls to Hell, and he fears that this Halloween, he will be the tithe. Janet can save him, and free him from the Queen’s thrall, but it will take huge courage. She must wait in the trees till she sees the faery folk ride in procession through the woods. She must let the first two horses pass, but when the third – a milk-white steed – appears, she must pull him down from it.

The faeries, he warns her, will be enraged, and now will come the hard part. She has to hold onto him whatever happens, though they’ll morph him into many hideous forms to try to make her let go. Sure enough, when she does as he tells her and pulls him from his horse, he is turned into a snake, a newt, a bear, a lion, red-hot iron, then burning lead. Through all the transformations, Janet holds on for dear life, and at the touch of the burning lead, forewarned by Tam, she tips her burden into the water of the nearby well. Tam climbs out, returned to his human form and free of servitude to the Queen. Though the Queens rails about the ‘theft’ of her dearest mortal, she sullenly admits defeat, and the young couple live, as they should, happily ever after.

Thomas Rhymer & the Queen of Elphame by Kate GreenawayThe story has many parallels and similarities in other traditions and tales – Thomas Rhymer, Cupid & Psyche, Childe Rowland, and even Beauty and the Beast: with the last, for instance, there’s the forbidden forest and the rose motif; the threatening inhuman figure with whom the heroine falls in love; his former identity as a noble young lord; and the fact that the heroine must go through dangers and horrors to rescue him. (There’s a theory that Beauty & the Beast is a later bowdlerisation of the Tam Lin story, leaving out the sex. I’ve always rather liked the Disney version more than their other ‘fairytales’, not least for its gutsy heroine, but it’s difficult to imagine it including ravishing among the roses followed by pregnancy...)

Thomas Rhymer & the Queen of Elphame by Kate GreenawayThe story has many parallels and similarities in other traditions and tales – Thomas Rhymer, Cupid & Psyche, Childe Rowland, and even Beauty and the Beast: with the last, for instance, there’s the forbidden forest and the rose motif; the threatening inhuman figure with whom the heroine falls in love; his former identity as a noble young lord; and the fact that the heroine must go through dangers and horrors to rescue him. (There’s a theory that Beauty & the Beast is a later bowdlerisation of the Tam Lin story, leaving out the sex. I’ve always rather liked the Disney version more than their other ‘fairytales’, not least for its gutsy heroine, but it’s difficult to imagine it including ravishing among the roses followed by pregnancy...)The reversal of ‘traditional’ fairytale roles is one of the most appealing aspects of Tam Lin. Tam is effectively helpless before the Faery Queen, though there’s nothing emasculated about him. It’s Janet who must free him, and she’s willing to undergo torments to do so. The fact that it all ends happily is unusual for a tale of the Faery Court.

Belief in faeries is still strong in areas of Scotland, which isn’t wholly surprising. There are still places wild enough for the barriers between reality and ‘something else’ to seem remarkably, tangibly thin (not least the haunting Isle of Colonsay, whose former laird MacPhie seems to have had an unusual number of run-ins with the people of the Otherworld). Superstitions still exist quite strongly (my mother-in-law’s gardener swore no good would come of her telling him to cut down a rowan tree, and blamed the foul deed immediately when the house subsequently burned down). At a relative’s baptism I remember being quite sure that an aged aunt’s refusal to drink from a green cup was down to an unwillingness to offend the faeries. As it turned out the prejudice was an extreme sectarian one, but I can’t believe the two aren’t linked, somehow and somewhere in the past.

As for the disappearance of unfortunate mortals, there are surprisingly recent tales. Tomnahurich is a hill in the middle of Inverness that’s long been associated with the Otherworld. A local story tells of two buskers, dressed in kilts and carrying pipes (all perfectly normal) who seemed so disoriented and terrified among the traffic that they spent a night in the police cells. When they were brought before the sheriff next day – luckily a Gaelic speaker, since they could speak nothing else – they explained that their panic was down to the world seeming to have changed a great deal since last night, when they were offered good money to play at a gathering of lords and ladies beneath Tomnahurich hill.

At a loss, the sheriff returned them for the time being to the cells, where a minister was summoned to the disturbed young men. As soon as he began to pray, and God’s name was mentioned, the young men, their instruments, and their payment all crumbled to dust.

It’s a fanciful story, and appears in many forms over the centuries, but in wilder landscapes it’s not hard to imagine another barely-seen world, repressed (perhaps temporarily...) by modernity and religion. Maybe that’s why the stories and their attached superstitions are resilient enough to survive into the contemporary world.

Or possibly it’s because the fairy stories are so entangled with religion and superstition and the beliefs of even more ancient times. The Fairy Hill of Aberfoyle in Perthshire is believed to house the spirits of the local dead, in a way that echoes the far older beliefs of those who buried their dead in chambered cairns. Catherine Czerkawska’s play The Secret Commonwealth is the tale of Aberfoyle minister Robert Kirk, who wrote a book of the same title, and whose knowledge was thought to come straight from the faeries themselves. He’s another one who meddled with them at his own peril: angry at his betrayal of their secrets, the faeries were said to have faked his death while abducting him to the Otherworld. He came to his cousin in a dream, telling him of his captivity and promising to appear at his own funeral – at which moment the cousin must throw a knife over his head to free him. Kirk duly appeared – but alas, the cousin was too gobsmacked to perform the required act, and the minister was never seen again.

It’s a chilling and wonderful story, but in Czerkawska’s play it’s used also as a metaphor for the loss of the ancient beliefs, the gradual withdrawal of an older tradition before the Christian ascendancy. What’s so fascinating about the fairy traditions is the way they were not discarded, but woven into the new beliefs: loathed by the Church, becoming associated with the devil and necromancy – but never wholly dying out.

Yet that mingling isn’t all bad. One of the loveliest cross-traditions, and my favourite, is the one – varying from region to region – that says the faeries are the rebel angels. Thrown out of Paradise by an angry God, the angels that fell into the sea became seals and seal people. The ones that were caught in the sky as they fell became the Merry Dancers, the Northern Lights. And the ones that fell on land? They became the Faeries.

Gillian Philip writes across genres: ‘anything that comes into my head, including fantasy, crime, science fiction and horror’. 'Bad Faith' is a Scottish-set dystopia about a society ruled by a tight-minded religious elite, and ‘Crossing the Line’ is a hard-edged thriller with a hint of the supernatural. As Gabriella Poole she has written the 'Darke Academy' series for Hothouse.

Gillian’s 'Rebel Angels' series ('Firebrand', 'Bloodstone', and - out in August - 'Wolfsbane') have to be some of the best new fantasies of recent years. Beginning in the 16th century at a time of witch hunts and burnings, it follows the fortunes of Seth MacGregor, bastard prince of the Scottish faeries, the Sithe, and an attractive hero in every sense of the word: lover, warrior, and owner of a sinister and beautiful waterhorse from the loch. The books are rooted in the history and folklore of Scotland, and quite unflinching about the cruelty and hardship of the times. The Sithe are ruled by a queen, Kate NicNiven, who is volatile, cruel and devious in the best traditions of fairy queens, and who deliberately stretches the loyalty of her subjects, Seth and his brother Conan included, almost to breaking point. There’s a protecting Veil between the land of the Sithe and the mortal world, and Kate wants to tear it away. And she invokes the help of some hauntingly unpleasant creatures called the Lammyr…

Picture credits: Carterhaugh: The copyright on this image is owned by Richard Webb and is licensed for reuse under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 license.Thomas the Rhymer & the Queen of Elphame by Kate Greenaway, d. 1901. Wikimedia Commons. Cleaned up from a scan found at Winterspells

Published on July 27, 2012 00:24

July 25, 2012

These caught my eye...

A handful of posts which caught my eye:

Steve Feasey talks to Lucy Coats about imps - particularly the Lincoln Imp, whom I hadn't heard of - at Scribble City Central

"It is morally right to respect the creator and not steal from him': Nicola Morgan on the Awfully Big Blog Adventure on digital piracy

A hoard of bronze-age swords on display in Cumbria at Esmeralda's Cumbrian History and Folklore

And: enthusiastic and charming: children's letters to Susan Price at A Nennius Blog

Steve Feasey talks to Lucy Coats about imps - particularly the Lincoln Imp, whom I hadn't heard of - at Scribble City Central

"It is morally right to respect the creator and not steal from him': Nicola Morgan on the Awfully Big Blog Adventure on digital piracy

A hoard of bronze-age swords on display in Cumbria at Esmeralda's Cumbrian History and Folklore

And: enthusiastic and charming: children's letters to Susan Price at A Nennius Blog

Published on July 25, 2012 00:53

July 24, 2012

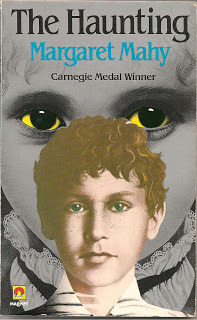

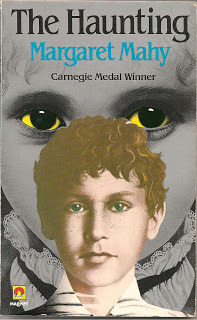

Margaret Mahy

I was saddened to hear yesterday of the death after a short illness of the wonderful New Zealand writer Margaret Mahy. She was 76, and in this day and age that's young... and Margaret Mahy was a writer who knew what it's like to be young. She wrote with insight and brilliance for all ages, from young children ('A Lion in The Meadow', 'The Downhill Crocodile Whizz') to young adults ('The Haunting', 'The Changeover', 'The Other Side of Silence'), and to call her a fantasy writer is only to begin to indicate - to anyone who hasn't read them - the individuality of her books.

'The Haunting', which won the Carnegie Medal, was the first of her titles which I ever read - back in 1982 - and I was inexorably drawn in from the first paragraph:

'The Haunting', which won the Carnegie Medal, was the first of her titles which I ever read - back in 1982 - and I was inexorably drawn in from the first paragraph:

When, suddenly, on an ordinary Wednesday, it seemed to Barney that the world tilted and ran downhill in all directions, he knew he was about to be haunted again. It had happened when he was younger, but he had thought that being haunted was a babyish thing that you grew out of, like crying when you fell over, or not having a bike.

But Barney's Great-Uncle Cole has died - and Barney is about to be haunted by the apparition of a mysterious child in a blue velvet suit who repeats: 'Barnaby's dead! Barnaby's dead - and I'm going to be very lonely.' As the apparition appears any time, anywhere, Barney becomes convinced that his dead uncle is sending him messages:

When he opened his eyes first thing in the morning he had seen through his window not the shaggy Palmer lawn and hedge, but a forest filled with glittering birds and dark red flowers, which had slowly faded to let the usual scene show through and take over. The blue milk jug on the table had wavered into another shape - a head, covered with tight blue curls and a dull bluish skin, crowned with a chain of gold leaves and berries. Its lips had moved, saying words he could not hear, and had then given him a terrifying smile.

It's so vivid it could be too frightening if it weren't for the fact that, as in most of Mahy's books, the child protagonist is not alone but surrounded by a large, charming, scatty but supportive family, whose members do their best to help him. As Barney's stepmother says, defending him against the power that threatens him:

"He's mine all right! Everyone in this family belongs to everyone else - belongs with everyone else, rather. I've looked after him for a year now - ironed his shirts, made his school lunches, told him stories. ... But what matters most is that he wants to be ours, and he doesn't want to be yours. That's what counts."

I'm sad she's gone. But at least I can go and read her books again. Fortunately there are many to choose from and I know they'll bring me wisdom and delight.

'The Haunting', which won the Carnegie Medal, was the first of her titles which I ever read - back in 1982 - and I was inexorably drawn in from the first paragraph:

'The Haunting', which won the Carnegie Medal, was the first of her titles which I ever read - back in 1982 - and I was inexorably drawn in from the first paragraph:When, suddenly, on an ordinary Wednesday, it seemed to Barney that the world tilted and ran downhill in all directions, he knew he was about to be haunted again. It had happened when he was younger, but he had thought that being haunted was a babyish thing that you grew out of, like crying when you fell over, or not having a bike.

But Barney's Great-Uncle Cole has died - and Barney is about to be haunted by the apparition of a mysterious child in a blue velvet suit who repeats: 'Barnaby's dead! Barnaby's dead - and I'm going to be very lonely.' As the apparition appears any time, anywhere, Barney becomes convinced that his dead uncle is sending him messages:

When he opened his eyes first thing in the morning he had seen through his window not the shaggy Palmer lawn and hedge, but a forest filled with glittering birds and dark red flowers, which had slowly faded to let the usual scene show through and take over. The blue milk jug on the table had wavered into another shape - a head, covered with tight blue curls and a dull bluish skin, crowned with a chain of gold leaves and berries. Its lips had moved, saying words he could not hear, and had then given him a terrifying smile.

It's so vivid it could be too frightening if it weren't for the fact that, as in most of Mahy's books, the child protagonist is not alone but surrounded by a large, charming, scatty but supportive family, whose members do their best to help him. As Barney's stepmother says, defending him against the power that threatens him:

"He's mine all right! Everyone in this family belongs to everyone else - belongs with everyone else, rather. I've looked after him for a year now - ironed his shirts, made his school lunches, told him stories. ... But what matters most is that he wants to be ours, and he doesn't want to be yours. That's what counts."

I'm sad she's gone. But at least I can go and read her books again. Fortunately there are many to choose from and I know they'll bring me wisdom and delight.

Published on July 24, 2012 00:43

July 20, 2012

Folktale Snippets: The Fairy Rade

Sir Joseph Noel Paton: 'The Fairy Rade: Carrying Off A Changeling - Midsummer's Eve

Sir Joseph Noel Paton: 'The Fairy Rade: Carrying Off A Changeling - Midsummer's EveIn honour of my recent stay in the beautiful Scottish border country (it rained every day, but we had a lot of fun anyway), here's an eye-witness account, from an unnamed 'old woman of Nithsdale’, of a Fairy Ride or cavalcade of the fairies, also known as the Seelie Hunt.

It’s taken from Thomas Keightley’s Fairy Mythology which was first published in 1828 - my second edition copy dates from 1850 – and, as is often the way of folk accounts, is strangely convincing. (A Scots mile (now obsolete) was about 220 yards longer than an English mile.)

“In the night afore Roodmass I had trysted with a neebor lass a Scots mile frae hame to talk anent buying braws i’ the fair. We had nae sutten lang aneath the haw-buss till we heard the loud laugh of fowk riding, wi’ the jingling o’ bridles, and the clankin’ o’ hoofs. We banged up, thinking they wad ride owre us. We kent nae but it was drunken fowk ridin’ to the fair i’ the forenight. We glow’red roun’ and roun’ and sune saw it was the Fairie-fowks Rade. We cowred down till they passed by. A beam o’ light was dancin’ owre them mair bonnie than moonshine: they were a wee wee fowk wi’ green scarfs on, but ane that rade foremost, and that ane was a good deal larger than the lave wi’ bonnie lang hair, bun about wi’ a strap whilk glinted like stars. They rade on braw wee white naigs, wi’ unco lang swooping tails, an’ manes hung wi’ whustles that the win’ played on. This an’ their tongue when they sang was like the soun’ of a far-away psalm. Marion and me was in a brade lea fiel’, where they came by us; a high hedge o’ haw-trees keepit them frae gaun through Johnnie Corrie’s corn, but they lap owre it like sparrows, and gallopt into a green know beyont it. We gaed i’ the morning to look at the treddit corn; but the fient a hoofmark was there, nor a blade broken.”

Here's my tamer English version:

In the night before Roodmas [the Feast of the Cross, May 3rd] I had met up with a neighbour lass, a Scots mile from home, to talk about buying pretty things at the fair. We hadn’t been sitting long under the hawthorn bushes when we heard the loud laugh of folk riding, with jingling bridles and clattering hoofs. We jumped up, thinking they would ride over us. We assumed it was drunken folk riding to the fair in the early evening. We stared round and about and soon saw it was the Fairy-folks Ride. We cowered down as they passed by. A beam of light was dancing over them, prettier than moonshine: they were tiny little folk with green scarves on, all but the one who rode in front, who was a good deal bigger than the rest, with lovely long hair bound about with a ribbon that glinted like stars. They rode on fine little white horses, with uncommonly long sweeping tails, and manes hung with whistles which the wind played on. This, and their voices when they sang, was like the sound of a far-away psalm. Marion and I were in a broad pasture field, where they came by us; a high hedge of hawthorn trees prevented them from going through Johnnie Corrie’s cornfield, but they leaped over it like sparrows and galloped into a green hill beyond it. We went next morning to look at the trodden-down corn, but devil a hoofmark [ie: not a single hoofmark] was to be seen, nor a blade broken.

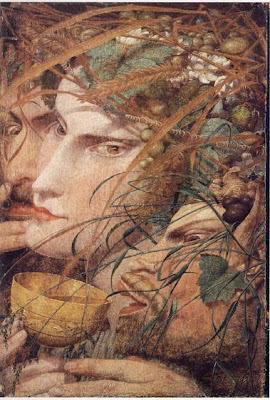

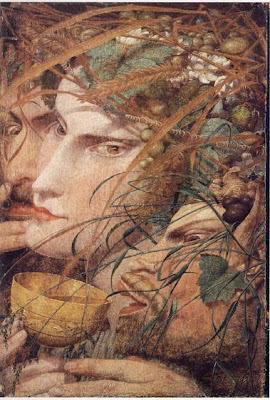

Richard Dadd: Bacchanalian scene

Richard Dadd: Bacchanalian scene

Published on July 20, 2012 01:22

Folklore Snippets: The Fairy Rade

Sir Joseph Noel Paton: 'The Fairy Rade: Carrying Off A Changeling - Midsummer's Eve

Sir Joseph Noel Paton: 'The Fairy Rade: Carrying Off A Changeling - Midsummer's EveIn honour of my recent stay in the beautiful Scottish border country (it rained every day, but we had a lot of fun anyway), here's an eye-witness account, from an unnamed 'old woman of Nithsdale’, of a Fairy Ride or cavalcade of the fairies, also known as the Seelie Hunt.

It’s taken from Thomas Keightley’s Fairy Mythology which was first published in 1828 - my second edition copy dates from 1850 – and, as is often the way of folk accounts, is strangely convincing. (A Scots mile (now obsolete) was about 220 yards longer than an English mile.)

“In the night afore Roodmass I had trysted with a neebor lass a Scots mile frae hame to talk anent buying braws i’ the fair. We had nae sutten lang aneath the haw-buss till we heard the loud laugh of fowk riding, wi’ the jingling o’ bridles, and the clankin’ o’ hoofs. We banged up, thinking they wad ride owre us. We kent nae but it was drunken fowk ridin’ to the fair i’ the forenight. We glow’red roun’ and roun’ and sune saw it was the Fairie-fowks Rade. We cowred down till they passed by. A beam o’ light was dancin’ owre them mair bonnie than moonshine: they were a wee wee fowk wi’ green scarfs on, but ane that rade foremost, and that ane was a good deal larger than the lave wi’ bonnie lang hair, bun about wi’ a strap whilk glinted like stars. They rade on braw wee white naigs, wi’ unco lang swooping tails, an’ manes hung wi’ whustles that the win’ played on. This an’ their tongue when they sang was like the soun’ of a far-away psalm. Marion and me was in a brade lea fiel’, where they came by us; a high hedge o’ haw-trees keepit them frae gaun through Johnnie Corrie’s corn, but they lap owre it like sparrows, and gallopt into a green know beyont it. We gaed i’ the morning to look at the treddit corn; but the fient a hoofmark was there, nor a blade broken.”

Here's my tamer English version:

In the night before Roodmas [the Feast of the Cross, May 3rd] I had met up with a neighbour lass, a Scots mile from home, to talk about buying pretty things at the fair. We hadn’t been sitting long under the hawthorn bushes when we heard the loud laugh of folk riding, with jingling bridles and clattering hoofs. We jumped up, thinking they would ride over us. We assumed it was drunken folk riding to the fair in the early evening. We stared round and about and soon saw it was the Fairy-folks Ride. We cowered down as they passed by. A beam of light was dancing over them, prettier than moonshine: they were tiny little folk with green scarves on, all but the one who rode in front, who was a good deal bigger than the rest, with lovely long hair bound about with a ribbon that glinted like stars. They rode on fine little white horses, with uncommonly long sweeping tails, and manes hung with whistles which the wind played on. This, and their voices when they sang, was like the sound of a far-away psalm. Marion and I were in a broad pasture field, where they came by us; a high hedge of hawthorn trees prevented them from going through Johnnie Corrie’s cornfield, but they leaped over it like sparrows and galloped into a green hill beyond it. We went next morning to look at the trodden-down corn, but devil a hoofmark [ie: not a single hoofmark] was to be seen, nor a blade broken.

Richard Dadd: Bacchanalian scene

Richard Dadd: Bacchanalian scene

Published on July 20, 2012 01:22