Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 6

July 26, 2022

Lord Dunsany on the magic of poetry (1)

In March 1943 Lord Dunsany delivered the three ‘Donellan Lectures’ at Trinity College, Dublin, choosing to speak about prose, poetry and drama. I’m repeating this post from 2020 as it’s just lovely, but also because I promised to follow it up with more of Dunsany’s thoughts on prose and poetry. I didn't get around to it then, but this time I will. Look out for more of Dunsany over the next few weeks!

"Nothing at all separates a poet in China from a poet in Ireland: both feel that beauty is sacred and is the outward and obvious expression of what is right and fitting: both labour to express those feelings worthily; their separation is only by centuries, and down these their thoughts travel until they meet in any land. And how does this strange magic work?

"If I revealed that secret, the magicians of the world would be angry with me, for they have always guarded their mysteries. But they need have no fear that this great mystery will escape from my lips, because I do not know it; I can only guess that our minds, which are strangely different from that lumber with which they are stored and that we call facts, are created in harmony with many ancient things like ripples on water, or the wind going over the trees, and even inhuman and undisciplined things like the singing of birds; and that words that are attuned to this ancient harmony, to the voice of the woods and the hills, the old voice of the earth, come to us when we hear them like his own language suddenly spoken at night to a wanderer in a far country.

"However the magic may work, the power that metre has is best explained by Keats when, describing a kindred power, the song of the nightingale, he says that it

oft-times hath

Charmed magic casements, opening on the foam

Of perilous seas, in faery lands forlorn.

"It is almost like the call of a horn heard in the morning by a busy man in a town, heard far off behind him from grassy uplands beyond the woods, with dew still on the grass and on the spider’s web … and sunlight streaming down valleys, that has not yet come to the town, for the golden morning has not yet peered over the high roofs. The man turns to the sound of the horn, but he cannot follow, for it is far away and he has much to do, and he has not the right clothes or boots for this: those distant valleys are not for him. Bodies are not moved so easily. But … the spirit, if once aroused, is up and away with a speed of which our bodies know nothing, and which cannot indeed be compared with the movement of any body, though the sudden dart of a snipe out of Irish marshes is something more like it than anything we can attain.

"But how is the spirit aroused by that haunting call, by that chiming of words that we call metre and rhyme? Our ears, our thoughts, our hearts, call it what you will, are made one way, and metre is made on the same plan, and so the two respond as two birds calling; singing and answering over a wide valley. How it is so I can only guess, but … it is certain that poets have the power to cast such spells.

"The certainty can be readily demonstrated by a single experiment. Take for instance a sentence such as: ‘She and I were born about the same time, and used to live at Brighton.’ You may anticipate a story when you hear those words, but you cannot be thrilled by the anticipation. Now take something similar, but said by a magician, Edgar Allan Poe:

I was a child and she was a child

In a kingdom by the sea.

"There you have a spell at once, or at least the beginning of one, one is half enchanted already, one’s spirit is prepared already for a far journey, and a very far journey: those simple words call to it far from here, for a kingdom by the sea is far on the way to fairyland. We have no such kingdoms here; kingdoms with coastlines we have in abundance, but a kingdom by the sea is a long way off, like little countries of which our nurses might have read tales to us a very long while ago."

Picture credits:

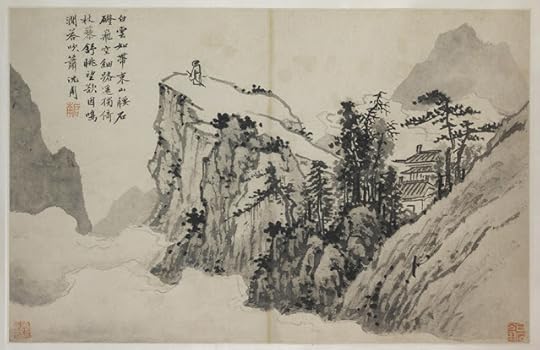

Poet on a mountain top by Shen Zhou, 1427 - 1509, Wikipedia

Miranda by John William Waterhouse, 1916, Wikimedia Commons

Val d'Aosta by John Brett, 1858 Wikimedia Commons

Walton on the Naze, Ford Madox Brown, 1860, Birmingham Museums Trust

June 21, 2022

The Green Lady, Jane, Orual and other adult women in the novels of C S Lewis

I will begin with the Green Lady, Perelandra’s unfallen Eve, though the novel has very much the quality, simplicity and large theme of the medieval morality plays (Temptation by the Devil, the Prevention of a New Fall), and characterisation is consequently minimal. There are just three characters of any significance: Dr Ransom, the Lady herself, and the devilish Un-man, none of whom is particularly complex. The Green Lady is all innocence and majesty, the Unman devilish horror, while Ransom is Everyman, or Every Christian, whose task it is to tackle evil and fight the good fight even when he thinks he isn’t up to it. Though the workings of the plot involve plenty of jeopardy and tension, for me the book’s appeal rests largely in the rapturous, lyrical writing with which Lewis brings this Edenic ocean world to rich life.

The Green Lady is a blend of mother-goddess and Mother-of-God, but we can glean quite a lot about Lewis’s view (circa 1941) of ordinary women and their roles from the strategies of temptation to which she is subjected. At work to make her break Maleldil’s command never to sleep on the Fixed Land, the Un-man suggests that Maleldil’s hidden purpose is for her to become independent – necessitating a disobedience which would really be a far higher obedience, and would make her wiser and ‘older’ than her absent husband the King. (Contextually, a bad idea.) To illustrate this argument the Unman tells her tales of tragic and noble heroines.

Each one of these women had stood forth alone and braved a terrible risk for her child, her lover or her people. Each had been misunderstood, reviled and persecuted: but each also magnificently vindicated by the event. The precise details were often not very easy to follow. Ransom had more than a suspicion that many of these noble pioneers had been what in ordinary terrestrial speech we call witches or perverts.

The Un-man’s appeal to the Lady is one of self-aggrandisement masked as self-sacrifice: ‘Do this for the King even if he doesn’t want you to: it will be for his own good.’ I’m not honestly sure how many witches that fits, or ‘perverts’ either – whomever or whatever Lewis intended by that term. Given that most of the people who ‘in ordinary terrestrial speech we call witches or perverts’ have in historical fact been innocent victims, it seems a bit rich for Lewis/Ransom to point the finger at them rather than at the witch-hunters. It is done for effect, doesn’t stand up to a moment’s thought, and should have been left out. But the clear implication of the passage is that busy-bodying interference in someone else’s life ‘for their own good’ is a female trait, or sin, and one the Green Lady as a woman is most likely to fall for. (Is it, though? Or is this the reaction of the little boy being made by Matron to swallow the cod-liver oil?) It becomes explicit when Ransom, ‘goaded beyond all patience’, loses his temper and

tried to tell her that he’d seen this kind of ‘unselfishness’ in action: to tell her of women making themselves sick with hunger rather than begin the meal before the man of the house returned, though they knew perfectly well that there was nothing he disliked more [my italics]; of mothers wearing themselves to a ravelling to marry some daughter to a man whom she detested; of Agrippina and Lady Macbeth.

From passive aggression to Lady Macbeth is quite an escalation. Ransom’s first example is sharp social observation but fails to investigate likely reasons why this test-case woman would delay her meal. What if she’s lonely? Who likes to eat on their own? What hour does the ‘man of the house’ get home? If she’s really ‘sick with hunger’, it must be late. Does he usually meet his friends in the pub for convivial drinks after work? Pubs in the 1940s were not places where women felt welcome. If he regularly abandons her in this way, of course he’ll detest this enacted reproach.

The Un-man’s final temptation is his attempt to teach the Green Lady vanity and exceptionalism, encouraging her to wear a robe of feathers and a chaplet of leaves, and to look at her own face in a cheap mirror which – it claims – will become ‘the Queen’s mirror, a gift brought into the world from Deep Heaven: the other women would not have it.’ Ransom perceives that the image of the Lady’s beautiful body has been shown her ‘only as a means to awake the far more perilous image of her great soul’ – and realises that ‘this has to stop.’ The contest now changes from a three-sided metaphysical or moral argument to a very physical battle between the Un-man and Ransom.

The Green Lady is an impressive, even awesome presence who is able to philosophise as well as Ransom can, if not better. When I said she is two-dimensional (in that morality play sort of way) I didn’t mean Lewis didn’t think hard about her: he did. As he explained in a letter to Sister Penelope Cary of 9 November 1941,

‘I’ve got Ransom to Venus and through his first conversation with the ‘Eve’ of that world: a difficult chapter. ...I may have embarked on the impossible. This woman has got to combine characteristics which the Fall has put poles apart – she’s got to be in some ways like a Pagan goddess and in other ways like the Blessed Virgin. But if one can get even a fraction of it into words it is worth doing.’

The polarity he mentions – ‘Pagan goddess/Blessed Virgin’ – is not a black and white one of evil/good or sin/virtue, but of sensuality/purity, and nothing is wrong with either of those qualities per se. In the sinless world of Perelandra they are combined, whereas in our sinful world, in Lewis’s view, they are separated. The man who introduced the Bacchantes into Narnia had no real problem with pagan goddesses. All the same, the Un-man’s attacks on the Lady target what Lewis seems to think of as women’s especial weaknesses, in particular a tendency to reorganise others’ lives, personal vanity, and self-dramatisation.

Some of these issues turn up again in Lewis’s portrait of a contemporary and more complex female character, Jane Studdock in That Hideous Strength (1945). Jane is the lonely young faculty wife of aspiring lecturer Mark Studdock, and her predicament – she has given up her studies to become a housewife – is sympathetically drawn. Lewis describes her marriage as

the door out of a world of work and comradeship and laughter and innumerable things to do, into something like solitary confinement. ... She had never seen so little of Mark as she had in the last six months. Even when he was at home he hardly ever talked. He was always either sleepy or intellectually preoccupied. [...] Was it the crude truth that all the endless talks which had seemed to her, before they were married, the very medium of love itself, had never been to him more than a preliminary?

Here, couched in much more understanding terms, is the viewpoint of the nameless woman whom Ransom complained of in Perelandra: sharp, spiky, intelligent Jane is bored stiff, and wasted on the trivial domestic routine which has become her life.

She had just left the kitchen and knew how tidy it was. The breakfast things were washed up, the tea towels were hanging above the stove, and the floor was mopped. The beds were made and the rooms ‘done’. She had just returned from the only shopping she need to that day, and it was still a minute before eleven. Except for getting her own lunch and tea there was nothing that had to be done till six o’clock, even supposing Mark was really coming home to dinner. But ... almost certainly ... he would ring up to say that ... he would have to dine in College. The hours before her were as empty as the flat.

Reading this we are immediately on Jane’s side, as Lewis intends. He is clear that Jane’s current existence is barren and pointless. But sympathetic as his portrayal is, this is no feminist take. Jane still hopes to complete an unfinished doctorate thesis on John Donne – but Lewis strongly hints that it’s not going to happen and that in any case it is the wrong way to go. What a married woman really needs is babies.

She had always intended to continue her own career as a scholar after she was married: that was one of the reasons why they were to have no children, at any rate for a long time yet. Jane was not perhaps a very original thinker, and her plan had been to lay great stress on Donne’s ‘triumphant vindication of the body’. She still believed that if she got out all her notebooks and editions and really sat down to the job she could force herself back into her lost enthusiasm for the subject.

Why has Jane lost enthusiasm for a thesis emphasising the ‘vindication of the body’? Perhaps, Lewis hints, because marital sex has proved a disappointment. Her husband Mark is ‘an excellent sleeper. Only one thing ever seemed to keep him awake after he had gone to bed, and even that did not keep him awake for long.’

Lewis's unkindest cut is ‘not an original thinker’. Jane, he lets us know, is not top-class academic material: and if you’re not top-class you shouldn’t try. But then her husband Mark is hardly a committed scholar. He is a sociologist – this is intentionally damning since the discipline was regarded by Oxbridge as very much below the salt, in the 1940s – and the only work he does for the vacuously named National Institute for Controlled Experiments (N.I.C.E.) is hack propaganda. At least Jane studied literature! One of the conscious ironies of the book is that Mark’s apparent success in scrambling into N.I.C.E.’s ‘inner ring’ is due not to his merits but to the fact that they need to recruit his wife. Jane is a seer whose visions would be useful to them, but she has become part of the real Inner Ring, the community of St Anne’s on the Hill. She is at the centre of what’s really happening, while Mark is clueless.

Lewis takes both characters on a pilgrim’s progress, but Mark’s is more convincing than Jane’s. One of the novel’s best passages is when Mark, who’s been desperately toadying the villains and is way out of his depth, finds the power to reject them when, asked to insult a crucifix, he has a Puddleglum-like moment: it may seem a trivial thing to trample an unfeeling image, but surely to insult the pain it represents would be a disgusting action. What side is he on? The worm turns, and he utters the natural but telling words, ‘I’m damned if I do any such thing.’

But Jane – sharp, unhappy, newly-married Jane – her road-to-Damascus moment comes when she is inexplicably bowled over by the male authority of Dr Ransom, now mysteriously transformed into the charismatic, golden-bearded Mr Fisher-King, aka the Pendragon – a sort of ur-Aslan, if you like. It is unbelievable: Ransom was never charismatic. We identified with him in the earlier books precisely because he was ordinary, modest, unsure. Dorothy Sayers put it fairly kindly in a letter to Lewis: ‘I don’t like Ransom quite so well since he took to being golden-haired and interesting on a sofa.’ Impossible to imagine the Ransom of Out of the Silent Planet or Perelandra expounding to Jane on courtship, ‘fruition’ and sexual enjoyment, or remarking: ‘No one has ever told you that obedience – humility – is an erotic necessity.’ So far as we know, Ransom has never married. Neither, at this point, had Lewis.

That Hideous Strength is a flamboyant but flawed mash-up of fantasy, science-fiction, horror, Christianity, the powers of the medieval cosmos and the Matter of Britain, and is strongly influenced by the ‘spiritual thrillers’ of Charles Williams – not to its benefit. Lewis seems to me never to have quite made up his mind what it’s about. Jane and Mark’s almost non-existent relationship is at its heart, but though their marital reunion is the culminating event of the book, they do nothing together. The lessons they learn are learned separately. Jane’s true destiny turns out to be wife-and-motherhood, albeit an enriched form following the conversion of both Mark and herself to a sacramental view of marriage with its duties and honours which include ‘the procreation of children’. There is even a suggestion from Merlin that the child she conceives should have been (or may yet be) one ‘by whom the enemies should have been put out of Logres of a thousand years.’ These are deep waters to drown in.

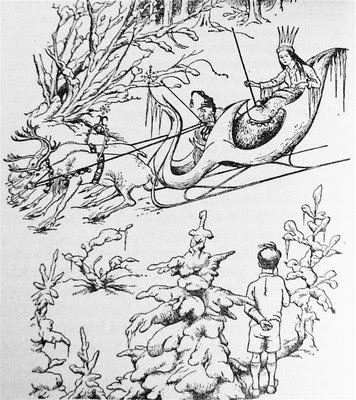

There are several adult women in the seven Narnia books. Some are villains, like the White Witch/Queen Jadis (I’ve never been entirely convinced they’re the same woman: Jadis has more personality), and the lamia-like Lady of the Green Kirtle who is drawn very much from medieval romance and balladry. On the virtuous side there is Digory’s kind, homely Aunt Letty, a minor character who all the same is capable of telling Uncle Andrew a few home truths. There is Ramandu’s unnamed daughter, who is not much more than a consolation prize for Caspian, denied the chance to visit Aslan’s country – and there are brief glimpses in The Horse and His Boy of the adult Queen Susan ‘The Gentle’ visiting her suitor Prince Rabadash in Tashbaan, and Queen Lucy ‘The Valiant’ riding with ‘a merry face’ to the relief of Anvard, armed with helmet, mailshirt, bow and arrows.

Lewis has sometimes been criticised for what one critic has termed ‘the dearth of heroic adult women’ in the Narnia books. But such criticism is mis-aimed. Adults do not get to be heroes in children’s books; it is children who have agency, who are put to the test and triumph. And of course the Narnia books feature several girl-heroes: Polly and her tough common-sense, Lucy with her integrity, Aravis’s fiery courage, Jill’s stubborn independence, woodcraft and archery. Adults in children’s fiction are either villains, or else supporting cast such as parents, grandparents and teachers. We might as well ask where the heroic adult menare, in the Narnia stories? They don’t exist either – for the same reason. But there are plenty of adult male villains: Uncle Andrew, King Miraz, Gumpas, the Governor of the Lone Islands. Does Shift the Ape count? He masquerades as a ‘man’ towards the end of the book. Where the female villains are charismatic and powerful, the male villains are sly and repulsive: when Queen Jadis meets Uncle Andrew, the latter collapses into a grovelling heap. I don’t see any reason to complain.

‘Hope not for mind in women,’ Jane quotes bitterly from Donne. ‘At their best/Sweetness and wit, they are but Mummy possest.’ And she goes on to wonder, ‘Did any men really want mind in women?’ It turns out that Lewis did. His marriage late in his life to Joy Gresham, neé Davidman – a civil marriage in early 1956, followed by a religious ceremony in March ’57 – was to him an emotional, mental and physical revelation. After her death from cancer a few years later, he wrote of her in A Grief Observed:

Her mind was lithe and quick and muscular as a leopard. Passion, tenderness and pain were all equally unable to disarm it. ... How many bubbles of mine she pricked! I soon learned not to talk rot to her unless I did it for the sheer pleasure [...] of being exposed and laughed at. I was never less silly than as H’s lover.

Till We Have Faces: A Myth Retold was published in 1956 and dedicated ‘To Joy Davidman’. They discussed it together as he was writing, and she wrote to her children’s father Bill Gresham that Lewis ‘says he finds my advice indispensable.' And it's Lewis’s masterpiece. It is the only work of fiction he ever wrote in the first person (he'd recently completed his own autobiography), and it is the exception to the rule that no matter whether he’s writing fiction, literary criticism or Christian apologetics, we always hear Lewis’s own voice in his books. Orual’s voice is stronger.

I will begin my writing with the day my mother died and they cut off my hair:

Batta, the nurse, shore me and my sister Redival outside the palace, at the foot of the garden which runs steeply up the hill behind. Redival was my sister, three years younger than I, and we two were still the only children. While Batta was using the shears many other of the slave women were standing around, from time to time wailing for the Queen’s death and beating their breasts, but in between they were eating nuts and joking. As the shears snipped and Redival’s curls fell off, the slaves said, “Oh what a pity! All the gold gone!” They had not said anything like that when I was being shorn. But what I remember best is the coolness of my head, and the hot sun on the back of my neck when we were building mud pies, Redival and I, all that summer afternoon.

A brilliant synthesis of voice, narrative and information, this does so much. We’re plunged into a vivid, ancient world of kings, queens and slaves, where little Orual and her sister, cared for by slaves, are so remote from their mother they’re not at all affected by her death and go on playing with mud ‘all summer afternoon’. We can see that Orual and Redival are at this time playmates; that Redival is pretty and Orual is not and that – at this time – Orual hasn’t realised it. All in one effortless paragraph. And Orual doesn’t sound like Lewis.

Lewis had been considering a version of the myth of Cupid and Psyche back in the 1920s, when he tried and then gave up writing a narrative poem on the subject (in which, interestingly Psyche has a sister named Caspian and a brother named Jardis, names that reappear in Narnia, gender-switched, as Prince Caspian and Queen Jadis). Three decades on, the story was still in his mind.

The myth of Cupid and Psyche, if it is a myth and not a fairy tale, first appears in Lucius Apuleius’ The Golden Ass. A picaresque romance of the second century AD, it is a ribald tale in which Apuleius is turned into a donkey by a Thessalian witch and has numerous bizarre adventures. In the 22nd chapter an old woman relates the story of a King with three daughters, the youngest of whom is so beautiful she attracts her people’s worship and the wrath of the goddess Venus. Obeying an oracle, her father takes her to a nearby mountain to become the bride or prey of a flying serpent. But Venus’ son Cupid has fallen in love with her, and she is carried away to a palace on the mountainside where each night he becomes her unseen lover. Psyche’s two sisters visit the mountain to mourn her fate, but are jealous when they discover her living in luxury. Warning that her lover may be a monster, they persuade her to disobey his command and light a lamp by which she can see and kill him. A drop of burning oil falls on Cupid, who wakes and flies angrily away. The envious sisters meet shameful deaths, but Psyche (now pregnant) sets out to seek her lover. Jealous Venus gives her a number of impossible tasks – sorting a heap of different kinds of grain, collecting gold wool from a flock of fierce sheep, fetching the water of death, and descending to Hades to beg Proserpina for a portion of her beauty. With fairytale assistance from ants, reeds, an eagle and a talking tower (!) Psyche succeeds, but is tempted to try some of Proserpina’s beauty on herself. The box contains a deadly sleep, and she falls senseless to the ground where Cupid discovers and wakens her. Jupiter makes Psyche immortal, and the lovers marry.

Lewis preserved the pattern of a king with three daughters. All the characters are excellent – the Fox, the educated Greek slave who is the voice of philosophy, reason and civilisation; the King, the three girls’ father, a violent, bullying Henry VIII figure whom Lewis keeps three-dimensional because of the contradictions in his nature. But the characters are all mediated to us via the voice and perceptions of the eldest daughter, and Orual is a passionate and unreliable narrator. Till We Have Faces is her story not Psyche’s, and the narrative we follow is one which in the end she comes to reassess. In Orual’s account, Redival grows up a shallow, sly, envious, tattling, man-loving minx and Psyche is innocent perfection. In fact, though Apuleius’ Psyche is a persuadable simpleton, Lewis’s Psyche possesses considerable mental and spiritual strength, and she grows up. Orual often misreads her half-sister, and the intensity of her feelings for her is almost suffocating:

I wanted to be a wife so that I could have been her real mother. I wanted to be a boy so that she could be in love with me. I wanted her to be my full sister instead of my half sister. I wanted her to be a slave so that I could set her free and make her rich.

The last sentence is the giveaway: Orual’s love is toxically possessive. Low in self-esteem, ugly, and denigrated by her father, she is needy for love. Far from setting Psyche free, she manipulates and clings to her. In Apuleius’ tale the two sisters are jealous of Psyche’s wealth, her rich palace. Orual is jealous too: jealous of any person or thing that will separate her from her sister. She believes she is weak and powerless when in fact she is monstrously strong.

And yet we’re on her side; Lewis is on her side. We know this story: we know that the palace which Orual can’t (in Lewis’ version) see, is real; we know that Psyche’s lover is Love himself. And we see her making this dreadful, catastrophic mistake. Forcing Psyche to break her promise to her invisible lover, Orual sticks a dagger through her own arm and threatens to kill them both. If you’re anything like me you’re inwardly crying ‘Don’t do it!’ It’s the worst possible emotional blackmail. Here again is the woman Dr Ransom complains of in Perelandra, the woman who meddles, who takes it upon herself to re-organise someone’s life ‘for their own good’ against their will, the woman who knows what’s best. But Orual cannot see the invisible palace or the beautiful wine cup; to her the rich wine is simple spring water. She cannot see what Psyche claims is there, so Psyche must be deranged. In her shoes we would probably feel the same way. Braced for disaster, we know she’s wrong, yet still we can understand and empathise.

But Orual has no empathy, no space left for anyone else. After Psyche has been chosen as the sacrifice to Ungit, Redival comes running to her in tears, babbling:

‘Oh Sister, Sister, how dreadful! Oh, poor Psyche! It’s only Psyche, isn’t it? They’re not going to do it to all of us? I never thought – I didn’t mean any harm – it wasn’t I – and oh, oh, oh...’

I put my face close up to hers and said very low but distinctly, ‘Redival: if there is one single hour when I am queen of Glome, or even mistress of this house, I’ll hang you by the thumbs at a slow fire until you die.’

Near the end, Orual reflects back on the time ‘when we were building mud pies, Redival and I, all that summer afternoon’. Tarin, a boy who was gelded and sold to punish his teenage romance with Redival, reappears in Glome as a diplomat in the service of the Great King and tells Orual that Redival was lonely after the birth of Psyche. ‘She used to say, “First of all Orual loved me much; then the Fox came and she loved me little; then the baby came and she loved me not at all.”’ Though Orual cannot quite believe him she admits that

one thing was certain; I had never thought at all how it might be with her when I turned first to the Fox and then to Psyche. For it had somehow been settled in my mind from the beginning that I was the pitiable and ill-used one. She had her gold curls, didn’t she?

It’s the beginning of her reassessment of her own life.

Lewis revisits, with so much more insight and compassion, themes that have cropped up time and again in earlier books. In Perelandra, the Green Lady is tempted to break Maleldil’s law by the non-human Un-man, an evident devil. In Till We Have Faces Orual causes Psyche to disobey another apparently arbitrary divine command. Orual even suggests that her lover ‘need never know’ – just as Queen Jadis suggests to Digory in The Magician’s Nephew that he can steal the apple of life for his mother and abandon Polly in Narnia, and nobody at home need ever know: ‘You needn’t take the little girl home with you, you know.’ Both suggestions are met with fiery disdain, but where Jadis is irredeemable, Orual’s ‘victory’ turns at once to ashes. She has made Psyche despise her. “[M]y heart was in torment. I had a terrible longing to unsay all my words and beg her forgiveness.’

There are other parallels. Motherless or abandoned children are scattered liberally throughout the Narnia books. In The Horse and His Boy, Shasta is stolen from his mother as a baby, and she dies long before he can be reunited with her, though there is no narrative reason why this should be. Prince Caspian’s mother is long dead, and his uncle Miraz gets rid of his nurse and mother-substitute. The youthful Prince Rilian of The Silver Chair loses his mother (Caspian’s queen) when she’s stung to death by a poisonous green serpent, and in The Magician’s Nephew Lewis re-imagines the events of his own mother’s death and gives Digory the miraculously happy ending he had prayed for as a child.

Yet in this book here’s Orual losing a mother and not caring a jot. All the caring is to come, when she makes herself surrogate mother of baby Psyche – to the exclusion of Redival. The passion Lewis explores in Orual is the passion of a strong-willed, capable, undervalued woman who knows she will never marry, never experience sexual love, never have children. There’s a lovely moment when she discovers Trunia of Phars in the palace gardens at night, on the run from his brother Argan, and he flirts with her in the dark: ‘I’ll bet a girl with a voice like yours is beautiful’. Orual finds this so unusual and so sweet she feels ‘a fool’s wish to lengthen it’, but knows it cannot go on.

So she cannot let go of those few to whom she is dear. Before fighting Argan of Phars in single combat she sets the Fox free – and dissolves in childish fear on realising that he may now wish to leave her. After an inward struggle he agrees to stay – ‘his face very grey and his manner very quiet.’ Orual, embracing him, feels ‘only the joy.’

The goddess Ungit, who is Aphrodite, is worshipped in Glome as ‘a black stone without head or hands of face’ and the old Priest of Ungit says that with her, ‘loving and the devouring are all the same thing.’ Orual makes an excellent Queen of Glome but she does devour those she loves, in particular her Captain of the Guard, Bardia, with whom she is in love. Jealous of his wife, she consoles herself by thinking her own relationship with Bardia is the more important. ‘Has she ever crouched beside him in the ambush? Ever ridden knee to knee with him in the charge? I have known, I have had so much of him she could never dream of.’ It’s selfish: we see she’s hard; we also see she doesn’t understand the damage she’s doing as, without intending it, she works him to death.

With all her flaws and faults we remain on Orual’s side (perhaps because her faults seem familiar) as she finally comes to a painful understanding of herself. In dreams or visions at the end of her life she stands barefaced and naked before the gods and makes her accusation against them. She thinks she is reading from the book she has written, the book we have been reading. But it’s a tattered roll scribbled over with a terrible outpouring of jealousy, anger and hate:

I never really began to hate you until Psyche began talking of her palace and her lover and her husband. Why did you lie to me? You said a brute would devour her. Well, why didn’t it? I’d have wept for her and buried what was left and built her a tomb and ... and ... But to steal her love from me! ... What should I care for some horrible, new happiness which separated her from me?

Listening to her own ‘real voice’ Orual at last recognises that she has been a destructive lover, angry with those whose other commitments threatened her – Psyche’s to the god, Bardia’s to his wife, the Fox to his homeland. This is her ‘death before death’: the spiritual death of the Orual who felt these things. The gods can never meet us face to face, she realises, ‘till we have faces’. It is the process of writing her accusation – her autobiography, the book we have been reading – that reveals her long-hidden face. The vision ends with her acceptance by and reunion with those who have loved her. In her devouring love she has been Ungit, but in her suffering she has also been Psyche.

All of CS Lewis’s novels explore the country of the spirit and this is eminently the case in Till We Have Faces. At the same time, in Orual he gives us the portrait of a lone woman, active in a man’s world. She has ruled a country and led her armies in battle – erasing Aslan’s remark about battles being ugly when women fight; all battles are ugly. She has killed men and passed judgements. Her reign has brought prosperity, stability and peace to Glome, and her people praise her. Her self-esteem is still low. On the brink of death she finds it strange that her women and Arnom the priest should weep for her: ‘What have I ever done to please them?’ Yet Arnom writes in her epitaph that she was ‘the most wise, just, valiant, fortunate and merciful of all the princes known in our parts of the world.’ Orual is a tour de force and is by far the most complex and interesting woman in Lewis’s fiction.

If Joy Davidman helped him to understand her, she did a good job.

If you've enjoyed this essay about CS Lewis's work, you might also enjoy my book on the Narnia stories: 'From Spare Oom to War Drobe: Travels in Narnia with my nine year-old self',published by Darton, Longman and Todd.

Picture credits:

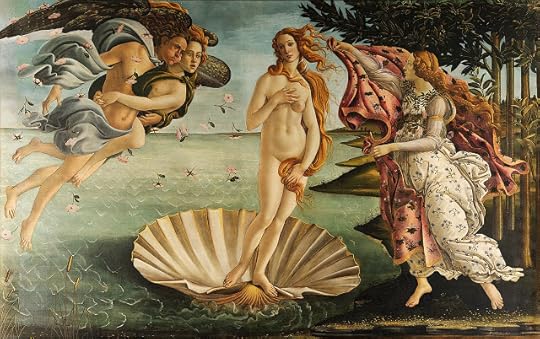

The Birth of Venus by Sandro Botticelli

The White Witch by Pauline Baynes

Queen Jadis and Uncle Andrew by Pauline Baynes

Psyche and Amor by Francois Gerard

Psyche's Wedding by Edward Burne Jones.

June 17, 2022

The Katharine Briggs Lecture

I’ve had a busy summer thus far, and I’ve neglected this blog for a month or two but I will be putting up a new post soon! In the meantime I’ve had lovely news which some of you may already have seen on my facebook and twitter feeds: I’ve been asked to give this year’s Katharine Briggs Lecture to the Folklore Society. Katharine Briggs is one of my heroes and I feel tremendously honoured by the invitation. The event will take place on Tuesday 8 November at 18:30 at The Brockway Room, Conway Hall, Red Lion Square, London WC1R 4RL. The title of my address is:

Fenrir’s Fetter and the Power of Stories.

On the power of stories for both good and ill.

JRR Tolkien wrote: “Spell means both a story told, and a formula of power over living men.” This is a talk about the power of stories – folk tales, fairy tales, the scary urban myths children tell one another – and those stories handed down in families, communities and nations which confer identity and pride, but which can become exclusionary. Stories may offer wisdom, solace, joy; they may also frighten or alienate. For good or ill they can change our perceptions of ourselves and the world around us.

Tickets are free but prior booking is essential. If you'd like to book your place, please email thefolkloresociety@gmail.comand you can find the event on the Folklore Society’s website: https://folklore-society.com/event/the-katharine-briggs-lecture-and-book-award-2022/

March 8, 2022

Strong Fairy Tale Heroines #31: THE GIRL AND THE ROBBERS

This Irish tale can be found in Jeremiah Curtin’s ‘Tales of the Fairies and of the Ghost World’ (1895) and is a version of the widespread tale type 'The Robber Bridegroom'. It was told to Curtin by a man ‘about forty years old’ named Diarmid Duvane, at a gathering of neighbours in a house near Ventry Strand at ‘a cross-road west of Dingle’. Duvane, who had been born in the area, had emigrated to America and lost his eyesight in a quarry explosion in Massachusetts. Returning to Ireland, ‘though blind, he found a wife and with her lives in a little cottage with a garden and a quarter acre of potatoes.’ He was, says Curtin, ‘a sceptic by nature’ but one who could tell many a good fairy tale. [NB: a wether is a gelded male sheep.]

There was a farmer in Kerry who owned a great many cattle and sheep and was a very rich man. There were four fairs in the year near his land, and one these was always held on St Martin’s Day. On that day they used to kill a sheep, a heifer or something to offer St Martin. That was the custom all over Ireland then, and still is.

The wife of this rich farmer died and left him with one son and one daughter. He didn’t remarry, and the son and daughter grew till they were of the age to be married, and off they went to the fair on St Martin’s Day. While they were gone their father forgot all about killing the beast for St Martin. Late in the evening his children came home, and they weren’t in the house five minutes before their father remembered what he should have done.

‘A thing has happened that never happened before to myself, my father or my grandfather,’ he said to his son. ‘I forgot to bring an animal into the house to kill for St Martin!’

‘What a misfortune!’ said the son.

‘We can mend it,’ said his father. ‘I want you to go up the hill now and bring me a wether. Go up to the pen on the hill and bring him down to me.’

‘I may not come back alive if I do,’ said the son, ‘and ‘tis you yourself that ought to think of St Martin, and get the sheep.’ The son wouldn’t be told, and he wouldn’t go, so then the daughter said to her brother that she’d go with him, but he swore he wouldn’t go at all, either alone or in company, so the sister said, ‘I’ll go without you.’ And she went to get a rope to tie the sheep.

In the parlour was a nice sword they kept in case there was need of it; it was in a scabbard hanging from a belt. The young woman buckled the belt around her waist and off she went to the hill, where the sheep were penned in a yard with a high stone wall to keep out dogs and wolves, and at one end was a little stone hut where a herder could take shelter. The girl chose the best wether she could find and tied the rope on him, but just as she started for home a great fog came down. She and the sheep got lost and wandered on the hill till they came back to the yard and the hut again, and she decided to wait out the fog and go home in the morning.

Around midnight what did she hear but men talking, and out of the fog and the dark came three fellows driving a great flock of sheep before them. Three brothers they were, robbers that plagued the whole countryside, and there was a hundred pounds reward on the head of each one of them. The girl hid herself in the stone hut and listened. One of the robbers picked out the best of her father’s sheep, the second added them to the flock they’d stolen, while the third man stood guard at the gate. The man choosing the sheep had chosen a good many, when he noticed the hut and said to himself, ‘Maybe he keeps the best of the bunch in here.’ He opened the door and put his head in. The girl was waiting behind it with the naked sword in her two hands. With one blow she took his head off and dragged him into the hut.

The other two called and asked what was keeping him. Getting no answer, the man who was minding the sheep put his head into the hut, and she served him the same way as the first one. The third and youngest called to his brothers, but what was use was it? Sure, they couldn’t answer. He went to the hut and what did he find but his brother stretched in the doorway; he pulled out the body and saw that the head was gone. The fear fell on him, and he took to his heels and left the others behind.

The girl was afraid to come out and stayed where she was till clear day. Then she found two flocks of sheep, for the robber had run off with only his life. She found the wether the rope was on and led him home with her. Her father had been crying and lamenting all night, sure that some evil had come to her. He welcomed her with gladness and asked what had kept her all night. She told him how she had killed the two robbers and left the yard full of sheep. It was well pleased he was to see her safe, and himself and the son went to the sheep yard, fetched the two heads, and taking the girl with them they went to claim the reward, Two hundred pounds she received, for her father said she had earned it and she should keep it.

Well, the news flew all over the country how the young woman had done such a great deed of bravery, and all the people, young and old, were talking of her. About a year later, who should come to the farmer’s house one evening but a man on horseback, and he dressed like any nobleman. They stabled his horse and after supper the farmer, who was wondering what could bring such a fine young man to his house, asked him who he was and what brought him?

‘I’ve come for a wife,’ said the young man.

‘Ah, don’t be talking,’ said the farmer, ‘my daughter is not a fit wife for the likes of you.’

‘If she pleases me, isn’t that enough?’ asked the young man. ‘I have riches enough for myself, and the two hundred pounds she got for the heads of the robbers is enough for her. I want no fortune, I want nothing but herself.’

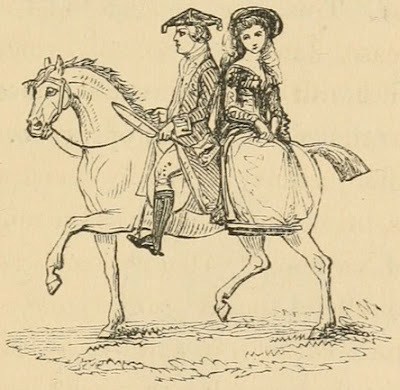

By the end of the evening, the farmer was well pleased wth the man, and the match was settled. The very next morning they had the marriage and the wedding, but then the husband wouldn’t stop another night: he said he must get home that very day. When the bride saw that, she looked at him closely and thought to herself, ‘He may well be a brother to the two men I killed.’ The young man mounted his horse and she sat behind him, pillion, but she had put the sword belt around her, and hidden the sword under her long cloak.

Away they rode, and not on the highway but through wild and lonely places, and never a word the man spoke to her till the middle of the afternoon, when he stopped and said, ‘Too long I’ve been waiting. I’ve the last of my patience lost and I’ll give you no more time. Come down from the horse.’

‘What are you saying?’ said she.

‘You killed my two brothers in the sheep yard,’ said he. ‘I have you now, and I don’t know how in this world I will make you suffer enough for it. It’s not a sudden death, but a long one I’ll be giving you.’ And what did he tell her then but to undress till he’d cut the flesh from her bit by bit, and she alive.

She came down from the horse. ‘Well,’ said she, ‘I’ve only one thing to ask.’

‘You’ll get nothing from me,’ said the robber.

‘All I wish is for you to turn your face from me while I’m undressing.’

It was the will of God that he turned his face away, and that moment she gave one blow of her sword on his neck and swept the head off him. She hid the head among the rocks where no dog or beast could come at it, for there were two hundred pounds on this man’s head, for he was the worst of the brothers.

Then she tried to turn the horse, but he wouldn’t move a step for her, so she let him have his head and take his own way and he never stopped till he reached the robbers’ house. There was no one there but a very old man, and when he heard the clatter he came out. Seeing the horse, he saluted the farmer’s daughter and asked where was his son?

‘He’s at his father-in-law’s house,’ said she. ‘He got married this morning. He’ll stop there tonight, and be here with his wife tomorrow. Friends will come with them to have a feast here; he sent me to tell you.’

The old man ordered his servant to make everything ready. ‘This is a rich house,’ he told the young woman.

‘Oh, sure your riches could never compare to what your son’s wife has!’

‘I’ll show you a part of the place,’ said the old man, and he showed her a room that was full of gold and silver in heaps. ‘Look at this!’ he said.

‘That is a deal of riches,’ said she, ‘but if there was twice more, ’twould be less than the riches your son’s wife has.’ At supper she asked, was it far to a town or city?

‘Cork is eight miles from this,’ said the old man, and he pointed out the road that led to the highway. Then he showed her to a room and a bed and told her to sleep without fear.

Well, the room was full of men’s clothes – coats, caps and three-cornered hats. She didn’t sleep, she slipped off her dress and put on a man’s clothes. She started at midnight and travelled till daylight. Not two miles from Cork, what did she see coming towards her but a young man on horseback. He saluted her and said, ‘I suppose you have been travelling all night?’

‘A good part of it,’ said she, ‘and I suppose you have, too?’

‘No, but I have to rise early. I am the Mayor of Cork, and have a great deal of work on my hands,’ said he.

Hearing this, she threw herself on her knees, and the Mayor asked what trouble was on her. She told all that had happened. So the Mayor went back to the city and brought out a good company of soldiers with two wagons, and they never stopped till they reached the robbers’ house, while the farmer’s daughter led the Mayor and some men to the place where she had hidden the head. They brought the head with them and gathered up all the riches at the robbers’ house, bound the old father and took him to Cork to be tried and judged and hanged. And the Mayor was unmarried, and what did he do but marry the farmer’s daughter, and she was his wife for as long as she lived.

* For more on the old Irish custom of killing a beast for St Martin, visit https://www.rte.ie/brainstorm/2019/1108/1089533-martinmas-blood-sacrifice-rites-ireland-november-11th/

Picture credit

Shepherdess by her hut, by Wilhelm Frey, 1872

Riding pillion, The Young Lady's Equestrian Manual, Project Gutenberg

February 17, 2022

Mi’kmaq Star Lore about the Great Bear

The following account is excerpted from 'The Celestial Bear' by Stansbury Hager in the 'Journal of American Folk-Lore', 1900. Vol XII, April-June. He says he was told the story by ‘the Mi’kmaqs of Nova Scotia, as we sat beside the camp-fire in the glorious summer evenings of that land, and pointed out overhead the stars of which they spoke.’ NB: the correct pronunciation of Mi'kmaq is 'Meeg-em-ach'. All additions in square brackets are by me.

"The stars of Ursa Major seem to have been called the Bear over nearly the whole of the North American continent... as far north as Point Barrow, as far east as Nova Scotia, as far west as the Pacific coast, and as far south as the Pueblos.

The Bear [in Mi’kmaq Muin, pronounced Moo-een] is represented by the four stars in the bowl of what we call the Dipper. Behind are seven hunters who are pursuing her, all of whom are named for birds. Close behind the second hunter is a little star. This is the pot he is carrying so that when the bear is killed, he can cook the meat in it. Just above these hunters a group of smaller stars form a pocket-like figure: this is the cave or den from which the bear has emerged.

Late in spring, the bear wakes from her long winter sleep, leaves her rocky den [Corona Borealis, marked Corona on the star map] and descends in search of food. Instantly the sharp-eyed Chickadee [Mi’kmaq: Chŭgegéss] perceives her, and being too small to pursue her alone, brings his pot and calls the other hunters to his aid. [The Chickadee is the brighter element of a naked-eye double star, Mizar, with its dimmer companion Alcor. Alcor is the pot!]

Together the seven hunters start after the bear, hungry for meat after the short rations of winter, and they follow her eagerly, but all summer the bear flees across the northern horizon and the chase continues. In the autumn, one by one the hunters in the rear begin to lose the trail. First the two owls, the Screech Owl [Ku’ku’gwes] and the little Saw-whet Owl [Kōpkéj] heavier and clumsier of wing than the other birds, disappear from the chase. But you must not laugh when you hear how Kōpkéj, the smaller owl, failed to secure a share of the bear meat, and you must not imitate his rasping cry, for if you do you can be sure that wherever you are, as soon as you are asleep he will descend from the sky with a birch-bark torch and set fire to your clothing. Next, the Blue Jay [Wōlōwej] and the Pigeon [Pŭlés] also lose the trail and drop out of the chase. This leaves only the Robin [Gapjagwej], the Moose-bird [Mi’kjagogwej], and the Chickadee to continue the hunt, and at last in mid-autumn they overtake their prey.

At bay, the Bear rises up on her hind legs and prepares to fight, but the Robin shoots her with an arrow and she falls over upon her back. Eager with hunger, the Robin leaps on his victim and becomes covered with blood which, flying to a nearby maple tree he shakes off on to the leaves, all except one spot on his breast. And this is why each autumn we see the forests of the earth becoming red, especially the maples, because trees on the earth follow the appearance of trees in the sky, and the sky maple received most of the blood. The sky is just the same as the earth, only up above, and older.

Some time after all this happened to the Robin, the Chickadee arrived on the scene. The two birds cut up the Bear, built a fire and placed some of the meat upon it. Just as they were about to eat, the Moose-bird caught up with them. He had almost lost the trail, but when he found it again he had not hurried, knowing that it would take his companions some time to prepare the meat and cook it, and he did not mind missing the work so long as he arrived in time to eat his share. And this worked so well for him, that ever since he he has not bothered to hunt for himself, preferring to follow other hunters and share their spoils, and so whenever a bear or moose or other animal is killed in the woods, he turns up to demand his share. This is why the other birds call him Mi’kjagogwej – He who comes in at the last moment – and the Mi’kmaq say there are some men who ought to be called that, too.

However, the Robin and the Chickadee, being generous, willingly shared their food with the Moose-bird: the Robin and the Moose-bird danced around the fire while the Chickadee stirred the pot.

But the story of the Bear does not end here. All winter long her skeleton lies upon its back in the sky, but her life-spirit has entered another bear who also lies asleep upon her back, invisible in the Den and sleeping the winter sleep. When spring comes round, this bear too will emerge, again the Seven Hunters will follow her, and the endless cycle will continue."

Stansbury Hager goes on to point out that the actions of the birds and animals in this story represent the yearly movement across the night sky of the constellations of Ursa Major, Bootes and Corona Borealis as seen from the latitude of Nova Scotia.

Picture credits:

Painting of Mi'kmaq settlement, Artist unknown, Nova Scotia Archives: Wikimedia Commons

Star Map - out of Patrick Moore's Naked Eye Astronomy, marked up by me.

Image of the Celestial Bear and her Hunters - Mc Master University Faculty of Social Sciences

February 16, 2022

Folklore Snippets: Thorsten and the Dwarf

Perhaps this is more of a fairytale snippet than a folklore snippet. The picture, which I rather like, is an imaginary reconstruction of Leif Eriksson's first glimpse of 'Vinland' painted by Christian Krohg (1893). The story hasn't anything to do with that, except that it's set in Vinland. It's a very tall tale of dwarfs and dragons, which I found in Thomas Keighley’s ‘Fairy Mythology’ (1828). Keightley claims it was taken from ‘Thorston’s Saga’ [sic]; I assume by this he means 'The Saga of Thorstein Vikingsson' which is similar in style - non-historical and full of adventures, sorcery and entertaining magical occurances - but I haven’t in fact been able to locate it there. If anyone knows, please enlighten me! Whatever its source, I love the laconic closing line.

[Edited to add: the knowledgeable Simon Roy Hughes of the blog Norwegian Folk Tales has come to my aid to say, 'There are a few Thorsteins in the sagas. You’re looking for the third chapter of “The Tale of Thorstein Bæjamagn” (Þorsteins Þáttr Bæjarmagns) in the Heimskringla'. Interestingly, the dragon seems to be a 19th century mistranslation of

Ørn (eagle) for 'Orm' (worm, dragon); unless perhaps the manuscript is unclear.]

When spring came, Thorsten made ready his ship and put twenty-four men on board of her. When they came to Vinland, they ran her into a harbour, and every day he went on shore to amuse himself.

He came one day to an open part of the wood, where he saw a great rock, and a little way out from it a Dwarf, who was horridly ugly and was looking up over his head with his mouth wide open; and it appeared to Thorsten that it ran from ear to ear, and that the lower jaw came down to his knees. Thorsten asked him why he was acting so foolishly.

‘Do not be surprised, my good lad,’ replied the Dwarf; ‘do you not see that great dragon that is flying up there? He has taken off my son, and I believe that it is Odin himself that has sent the monster to do it. But oh, I shall burst and die if I lose my son.’

Then Thorsten shot at the dragon and hit him under one of the wings, so that he fell dead to the earth; but Thorsten caught the Dwarf’s child in the air, and brought him to his father.

The Dwarf was exceedingly glad, and rejoiced more than anyone could tell, and he said, ‘A great benefit have I to reward you for, who are the deliverer of my son; and now choose your recompense in gold and silver.’

‘Cure your son,’ said Thorsten, ‘but I am not used to take rewards for my services.’

‘It would not be right,’ said the Dwarf, ‘if I did not reward you; and do not think my shirt of sheeps’ wool, which I will give you, a contemptible gift, for you will never be tired when swimming, or ever get a wound, if you wear it next to your skin.’

Thorsten took the shirt and put it on, and it fitted him well, though it had appeared too short for the Dwarf. The Dwarf now took a gold ring out of his purse and gave it to Thorsten, telling him that he should never want for money while he kept that ring. He next took a black stone and gave it to Thorsten and said, ‘If you hide this stone in the palm of your hand, no one will see you. And now I have few more things to offer that would be of value to you, but I will give you this fire-stone for your amusement.’

He took the stone out of his purse, and with it a steel point. The stone was triangular, white on one side and red on the other, and a yellow border ran around it. The Dwarf said, ‘If you prick the white side of the stone with the point, there will come on such a hailstorm that no one will able to see through it; but if you want to stop this shower, you have only to prick the yellow part, and there will come so much sunshine that the hail will melt away. But if you should prick the red side, out of it will come such fire, sparking and crackling, that no one will be able to look at it. You can get whatever you want from this point and stone: and they will come back to you by themselves when you call them.

‘I can now give you no more such gifts.’

Thorsten thanked the Dwarf for his presents and returned to his men, and it was better for him to have made this voyage than to have stayed at home.

February 3, 2022

Lost fairy tales of 16th century England and Scotland

Most of the fairy tales we know today we owe to versions collected during the 19th or early 20thcenturies. But although fairy tales were certainly being told during the 16thcentury – along with legends and ballads and the kinds of tale which Sir Philip Sidney describes in ‘An Apologie for Poetry’ as holding ‘children from play and old men from the chimney corner’ – we have little direct evidence for them and many must have simply disappeared.

Of course there are hints and inferences. Thomas Nashe name-checks the tale of ‘Tom Thumb’ in ‘Pierce Penniless’ (1592), complaining sourly that ‘…every gross-brained idiot is suffered to come into print, who if he set forth a pamphlet of the praise of pudding-pricks[skewers], or write a treatise of Tom Thumb … it is bought up, thick and threefold, when better things lie dead.’ People clearly knew about ‘Tom Thumb’, but there’s no printed trace of it until it was published as a chapbook in 1621. With woodcuts!

The English fairy tale ‘Mr Fox’ must also have been widely known in the 16thcentury, since Edmund Spenser and Shakespeare both quote from it – Spenser in ‘The Faerie Queene’ (1596) and Shakespeare in ‘Much Ado About Nothing’ (1598). But the story has only survived because a certain Mr Blakeway contributed a note to Edmond Malone’s 1790 edition of the complete works of Shakespeare (‘Malones’s Variorum Shakespeare’), to clarify the lines in ‘Much Ado About Nothing’ Act I, Sc 1, where Benedick says to Claudio: ‘Like the old tale, my lord: it is not so, nor ‘twas not so; but, indeed, God forbid it should be so.’ Blakeway wrote: ‘I believe none of the commentators have understood this; it is an allusion, as the speaker says, to an old tale, which may perhaps still be extant in some collections of such things, or which Shakspeare may have heard, as I have, related by a great aunt, in his childhood.’ And he then went on to recount the whole story, as well he could remember it. [To read more about that, click here.]

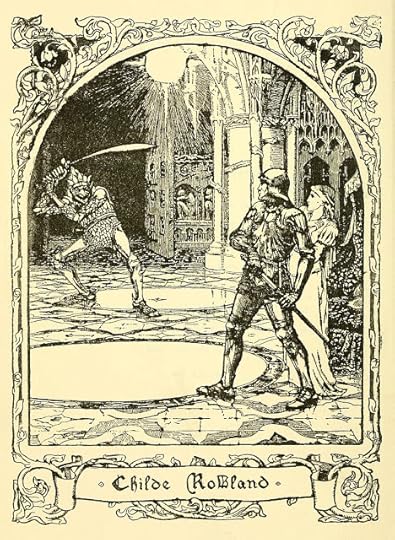

Edgar, in ‘King Lear’ (1605), refers to the fairy story or ballad of ‘Childe Roland’:‘Child Roland to the dark tower came,

His word was still, “Fie, fo and fum,

I smell the blood of a British man.”’

Yet again, we're lucky to have it. The story survives only in a single, imperfectly remembered version recorded by the Scots writer Robert Jamieson in his book ‘Illustrations of Northern Antiquities’ (1814). It had been told to him in boyhood by a journeyman tailor, who recited it ‘in a sort of formal, drowsy, mannered, monotonous recitative, mixing prose and verse, in the manner of the Icelandic sagas and as is still the manner … among the Lowlanders in the north of Scotland, and among the Highlanders and Irish.’ It is an elaborate and haunting tale, in which Childe Roland (or Rowland) goes to rescue his sister Burd Ellen from the Elf-King who lives in a hall under a green hill. Like a giant, the Elf-king bounds out, crying:

‘With fee, fi, fo and fum!

I smell the blood of a Christian man!

Be he dead, be he living, wi’ my brand

I’ll clash his harns [brains] frae his harn-pan!’

Thomas Nashe preserves perhaps the earliest version of this ‘giant’s chant’ in ‘Have With You to Saffron Walden’ (1596), in which he gleefully attacks his enemy the writer and schoolman Gabriel Harvey, accusing him of being a time-wasting pedant ‘who will find matter enough to dilate a whole day of the first invention of Fy, fah and fum, I smell the blood of an English-man.’ (Exactly what I’m doing in this essay; and by the way, Nashe is inventing all this to belittle Harvey. He doesn’t expect to be believed.)

A similar rhyme appears in ‘The Red Etin’, a Scottish story about a monstrous giant which I first read as a child in ‘The Blue Fairy Book’. The Etin chants:

‘Snouk but and snouk ben,

I find the smell of an earthly man;

Be he living or be he dead

His heart shall be kitchen to my bread.’

The Langs found the tale in Robert Chambers’ ‘Popular Rhymes of Scotland’ (1841), but the story is very old. It is mentioned in the ‘Complaynt of Scotland’ (1548) as ‘the tale of the Red Ettin with the three heads’ – and earlier still in Sir Robert Lyndsay’s poem ‘The Dreme’ (1528), in which he reminds the 16 year-old King James V of Scotland of the stories he told him as a child, including:

The propheceis of Rymour, Beid and Marlyng,

And of mony uther pleasand storye

Of the Reid Etin, and the Gyir Carlyng…

[The prophecies of Rhymer, Bede and Merlin,

And of many other pleasing stories,

Of the Red Etin, and the Giant Woman.]

So far we’ve clocked up ‘Tom Thumb’, ‘Mr Fox’, ‘Childe Roland’ and ‘The Red Etin’, with tantalising hints of other tales. I wonder when ‘Jack the Giant Killer’ was first told in the form we know it? It is found in a chapbook ‘The History of Jack and the Giants’, printed in Newcastle in 1711 in two parts, of which only the second still exists. But, say the Opies in ‘The Classic Fairy Tales’, the title-page set out a full account of Jack’s deeds:

Victorious conquests over the North Country Giants, destroying the inchanted Castle kept by Galligantus, dispers’d the fiery Griffins, put the Conjuror to flight, and released not only many Knights and Ladies, but likewise a Duke’s Daughter to whom he was honourably married.

The mid-16th century ‘Complaynt of Scotland’ contains a long and fascinating list of titles, some of which sound very much like lost fairy tales. One is ‘The Tale of the Giant that Ate Men Alive’. Did it feature a hero named Jack - or Jock? Who knows? There is also ‘The Tale of the Three-Footed Dog of Norway’, ‘The Tale of the Pure Tint’, ‘The Tale How the King of Eastmoreland Married the King’s Daughter of Westmoreland’… but however much they were told and enjoyed, they are lost. Nobody ever wrote them down.

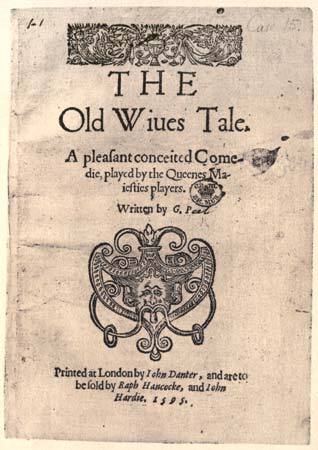

We can add to the list, however. ‘The Old Wives Tale’ by the Elizabethan poet George Peele is a short one-act play ‘of magic and adventure, farce and mystery’ which was published in 1595: the title-page declares it to have been performed by ‘the Queene’s Majesties’ Players’. It’s utterly charming, and I find it fascinating because it contains so many fairy tale references and motifs. The story opens like this:

Three servants benighted in a dark wood take shelter in a blacksmith’s cottage. As there is only one bed and the blacksmith needs his sleep, his old wife Madge suggests that one of the three young fellows should share with him while the other two sit up with her: ‘They that ply their work must keep good hours,’ she tells them. ‘One of you go lie with him; he is a clean-skinned man, I tell you, without either spavin or windgall.’ Then to pass the time, she agrees to tell ‘an old wife’s winter tale’: an offer that is met with enthusiasm. ‘A tale of an hour long were as good as an hour’s sleep,’ exclaims one, and the other, ‘Look you, gammer, of the giant and the king’s daughter…’ In fact they want to hear a fairy tale, and the old woman begins telling one, in a rambling, forgetful manner.

“Once upon a time there was a king, or a lord, or a duke that had a fair daughter, the fairest that ever was, as white as snow and as red as blood; and once upon a time, his daughter was stolen away, and he sent out all his men to seek for his daughter, and he sent so long that he sent all of his men out of his land. […]

There was a conjuror, and this conjuror could do anything, and he turned himself into a great dragon, and carried the king’s daughter away in his mouth to a castle that he made of stone, and there he kept her I know not how long, till at last all the king’s men went out so long that her two brothers went to seek her. Oh, I forgot! He [the conjuror] turned a proper young man to a bear in the night and an old man by day, and he made his lady run mad… God’s me bones! Who comes here?”

She breaks off in surprise: the kidnapped lady’s two brothers have suddenly appeared on stage to seek their lost sister. Seeing the Old Man (the enchanted youth) picking ‘hips and haws and sticks and straws’ at a wayside cross, they give him alms; he in return gives them mysterious advice from ‘the White Bear of England’s Wood’ – which sounds like another lost fairy tale in itself, especially as we hear no more of it. Anyway, Madge’s story has come to life, and the play now unfolds before her startled eyes.

The villain is Sacrapant the Conjuror. Previously, he was besotted with Venelia, the betrothed of young Erestus. Sacrapant turned Erestus into an Old Man by day and a White Bear by night, and enspelled the lady Venelia to run mute and distracted through the woods. More recently he has abducted Delia, daughter of the king of Thessaly, and caused her to forget her true identity – so that when she encounters her brothers, she doesn’t know them. Sacrapant is old, but by his art is able to look like a ‘fair young man’; his power is stored in a little glass vial with a flame in it, which he keeps buried. Also searching for Delia is her lover, the Wandering Knight, Eumenides.

‘The Old Wives Tale’ is stuffed with fairy tale references which George Peele clearly expected everyone in the audience to recognise – as we still do. ‘As white as snow and as red as blood’, says old Madge. Peele probably never knew a version of ‘Snow White’, but we remember how the mother wishes for a daughter ‘as white as snow, as red as blood, as black as ebony’: it is a common fairy tale description.

And there is much, much more. About a third of the way through the play, Sacrapant asks Delia what she would like to eat and drink, and she playfully demands ‘the best meat from the king of England’s table and the best wine in all France, brought in by the veriest knave in all Spain.’ He responds:

‘Well, sit thee down.

Spread, table, spread; meat, drink and bread.

Ever may I have what I ever crave.’

These words demonstrate that Sacrapant possesses a Magic Table which supplies food and drink (the well-known fairy tale motif Aarne Thompson Index D1472.1.7). In the Grimms tale, ‘The Wishing Table, the Gold-Ass and the Cudgel in the Sack’ (KHM 36), a youth is given a little wooden table. It doesn’t look much, but he only has to say, ‘Little table, spread yourself’, and it covers itself at once with ‘a clean little cloth, a plate, knife and fork, dishes with boiled and roasted meats … and a great glass of red wine that shone so as to make his heart glad.’ Sacrapant uses just the same form of words, ‘Spread, table, spread.’

Stories involving Wishing Tables, then, were clearly being told during the 16thcentury: Peele expects his audience to recognise this one as a standard magical prop that needs no explanation. Staging such magic would of course be difficult: the get-out is Delia’s demand that the food be served by ‘the veriest knave in all Spain’, so the magic duly conjures up a Spanish Friar (Spanish! Friar! Hiss! Boo!) to bring the food to the table.

In a sub-plot that runs through the play, a poor man called Lampriscus has two daughters: Zantippa, beautiful but shrewish and Celanta, ugly but kind. This is a deliberate reversal of The Kind and Unkind Girls (AT tale type 480): usually the beautiful sister is kind; the unkind one, ugly. Lampriscus sends the pair to find their fortunes by drawing water from the Well of Life. When Zantippa brings her pitcher to the well, a voice speaks and a Head rises from the water, saying,

‘Gently dip, but not too deep,

For fear you make the golden beard to weep.

Fair maiden, white and red,

Comb me smooth and stroke my head

And thou shalt have some cockle-bread.’

Zantippa takes offence at this request and smashes her pitcher over the Head. Maybe she simply objects to combing and smoothing the Head, but the editor of the Mermaid edition of the play, Charles Whitworth, believed that cockle-bread ‘may have been’ made with seeds of the weed corn-cockle and thought to be an aphrodisiac; he quotes Aubrey recording a ‘wanton sport’ called ‘moulding of cockle-bread’ which involved young maids climbing on to a table with skirts and knees raised and then ‘wabbl[ing] to and fro with their Buttocks as if they were kneading of dough with their Ayrses.’ Here is a great glimpse of 17th century kitchen-life; you can hear their shrieks of laughter – but I doubt if corn-cockle would ever have been deliberately introduced into bread, as it seems to have had a bad taste. As John Gerard in The Herball or Generalle Historie of Plantes (1597) writes: ‘the spoil unto bread, as well as colour, taste and unholesomnes, is better known than desired’.

Whatever the implication of the song, Zantippa is angered and departs without any water. But when the ill-favoured but kind Celanto arrives and obligingly strokes and combs the Head, it sinks into the well to rise again with gold for her to comb into her lap, singing:

‘Fair maiden, white and red,

Stroke me smooth and comb my head,

And every hair a sheaf shall be,

And every sheaf a golden tree.’

Heads in wells turn up in many later fairy tales. In ‘The Princess of Colchester’, from ‘The History of the Four Kings of Canterbury, Colchester, Cornwall and Cumberland’ (a chapbook printed in Falkirk, Scotland, in 1823), an old man advises a princess how to get through a dense, thorny thicket. Hidden beyond it is a well. ‘Sit down on the brink,’ he tells her, ‘and there will come up three golden heads, which will speak, and whatever they require, that do.’ One by one, the heads come up, singing:

‘Wash me, comb me,

Lay me down softly.’

She complies and the three heads reward her with beauty, sweetness of breath and body, and ‘marriage to the greatest prince that reigns.’ Joseph Jacobs adapted this story for his ‘English Fairytales’ (1890), renaming it ‘The Three Heads in the Well’, the title by which it’s now best known. He modernised the style – ‘will you please to partake?’ becomes ‘would you like to have some?’ – and less successfully prettied up the rhyme:

‘Wash me and comb me

And lay me softly:

And lay me on a bank to dry;

That I may look pretty

When somebody passes by.’

The last two lines somehow trivialise the Heads, which I feel in my bones have gravitas and power.

Wikipedia notes the similarities between ‘The Three Heads in the Well’ and ‘The Old Wives Tale’ but incorrectly claims ‘The Old Wives Tale’ as the first recorded instance of the Heads in the Wellmotif. In fact there’s a Scottish variant, ‘The Wal at the Warldis End’, which is name-checked in the ‘Complaynt of Scotland’ (1548) although misspelt as ‘The Wolf of the Warldis End’. It is told in full in Robert Chambers’ ‘Popular Rhymes of Scotland’ (1841): a king’s daughter is sent by her stepmother to fetch a bottle of water from, yes, the well at the world’s end. After crossing ‘a moor of hecklepins’ – sharp pins packed together and used for teasing out wool – the girl finds the well too deep to reach with her bottle; as she wonders what to do, she sees ‘three scaud men’s heads’ looking up at her. (‘Scaud’ means scalded or burned; it may mean the heads are bald or blackened.) The heads say together,

‘Wash me, wash me, my bonnie May

And dry me wi’ yer clean linen apron.’

When the girl obliges they fill her bottle with water and give her three gifts: to be ten times bonnier than before, that jewels shall fall from her mouth every time she speaks, and for her to be able to comb gold and silver out of her hair. Her rude and careless stepsister of course fares badly.

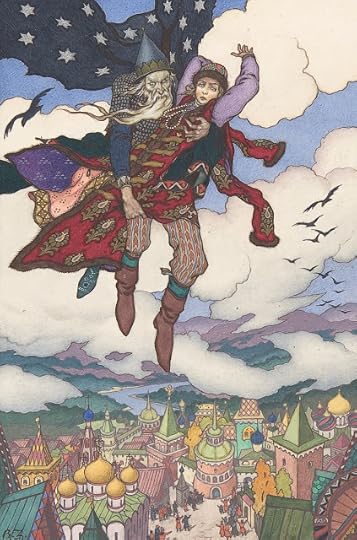

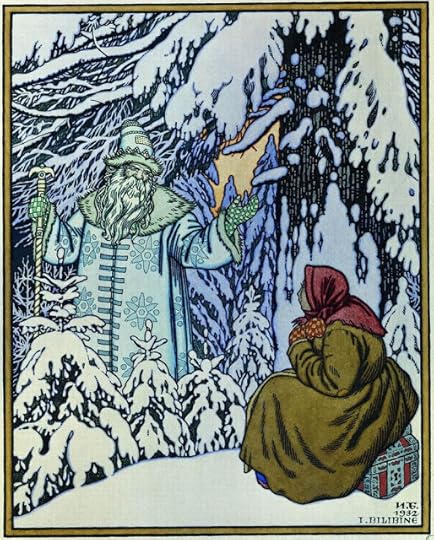

Returning to the main story-line, you’ll remember the conjuror Sacrapant’s magical power is contained in a buried, light-filled vial? This resembles the many fairy tales around the world in which a giant, ogre or magician keeps his heart, soul, or power separately hidden, and the trope is known as The Ogre’s Heart in the Egg (AT tale type 302). An example is the Russian tale ‘Koshchei the Deathless’. Koshchei is a semi-mythological character, a monstrous magician who has carried off not only a king’s daughter but also the mother of the hero Prince Ivan.

When Ivan arrives at Koshchei’s mountain fortress, his mother wheedles from Koshchei the secret of his hidden death. ‘There stands an oak,’ he tells her, ‘and under the oak is a casket, and in the casket is a hare, and in the hare is a duck, and in the duck is an egg, and in the egg is my death.’ Of course in the end, Prince Ivan succeeds in finding and smashing the egg, and Koshchei the Deathless dies.

Our magician Sacrapant boasts of his vial:

‘With this enchantment do I anything,

And till this fade, my skill shall still endure,

And never none shall break this little glass.

But she that’s neither wife, widow nor maid.

Then cheer thyself; this is thy destiny

Never to die but by a dead man’s hand.’

There are two points here. Firstly, Sacrapant’s confidence that no one can break the glass is based on his belief that there is no such thing as a woman who is neither wife, widow or maid. But this is one of those apparently reassuring prophecies which contains its own destruction – like that of the witches who tell Macbeth to ‘Laugh to scorn/The power of man, for none of woman born/Shall harm Macbeth’. Though true, their words are deceptive – as Macbeth finds out while he’s fighting Macduff.

Macbeth: I bear a charmèd life, which must not yield

To one of woman born.

Macduff: Despair thy charm,

And let the angel whom thou still has served

Tell thee Macduff was from his mother’s womb

Untimely ripped.

Like Macbeth, Sacrapant fails to read the small print. A 16th century betrothal was a contract, after which sexual intercourse might legitimately take place prior to the expected wedding. (In Measure for Measure, Mariana is betrothed to Lord Angelo but he has abandoned her, which is very much to his discredit.) Betrothed to Erestus, no longer a maid, but as yet unmarried, Venelia will be able to break Sacrapant’s glass. Second, Sacrapant’s confidence in his invulnerabilty is bolstered by the belief that he is destined ‘never to die, but at a dead man’s hand’: an apparent impossibility. I haven’t been able to find a tale-type for this particular trope, but the example best known today must surely be the Lord of the Nazgûl’s certainty that ‘no living man’ can slay him. Cue: Eowyn!

And cue: the Grateful Dead Man! (AT tale type E341: the best known version must be Hans Christian Andersen’s ‘The Travelling Companion’.) Delia's lover Eumenides meets the Old Man (Erestus) who tells him, ‘Bestow thy alms, give more than all/Till dead men’s bones come at thy call.’ Unsure what this means, Eumenides sleeps on it and is awakened by an altercation. A Churchwarden and Sexton are refusing to bury a poor man, Jack, who has died leaving no money for the funeral. Eumenides pays for the burial and shortly afterwards is overtaken by a young lad who offers to serve him: ‘Are you not the man, sir – deny it if you can, sir – that gave all the money you had to the burying of a poor man, and but one three-halfpence left in your purse? Content you, sir, I’ll serve you – that is flat.’ He gives his name as Jack – a name so common that Eumenides does not associate him with the dead man. (After all why should he?) Arranging a fee of half of whatever his master wins, Jack assists and protects Eumenides. Invisible, he steals away Sacrapant’s sword and wreath – and probably runs him through with the sword (there is no stage direction) as the conjuror cries,

‘My blood is pierced, my breath fleeting away

And now my timeless date is come to end’.

Slain by the dead man, Sacrapant dies and goes to hell, but his magic is still contained in the vial. Jack now summons Venelia to break the glass, all the wicked enchantments are undone and Delia and Eumenides are reunited: but under the terms of Jack’s agreement with Eumenides, he was to share half of all that Eumenides gained. Testing his master’s faith, he asks Eumenides to cut Delia in two. (You can get away with this in fairy tales, which are about action, not characterisation.) Eumenides reluctantly agrees and Delia exclaims ‘Farewell, world!’: then –

Jack: Stay, master! It is sufficient that I have tried your constancy. Do you now remember since you paid for the burying of a poor fellow?

Eumenides: Ay, very well, Jack.

Jack: Then, master, thank that good deed for this good turn. And so, God be with you all.

Jack leaps down in the ground.

A theory about ‘The Old Wives Tale’ is that it was written for a company of child actors, which could explain why it’s so short. You can imagine the intelligentsia permitting themselves to enjoy the charming sight of children acting out a rustic fairy tale; if Thomas Nashe’s contempt for ‘Tom Thumb’ and ‘Fee fi foh fum’ was generally held, this offered the excuse. In fact the play is not naïve; there’s more than a hint of tongue-in-cheek fun about it: but it’s kindly. There’s no derision. Perhaps it's more a masque than a play, and Milton borrowed the story of brothers seeking a sister imprisoned by a magician for his masque ‘Comus’, presented at Ludlow Castle on Michaelmas night, 1634. He subdued the folksy elements, however, giving the role of the Dead Man to the rather more ethereal Attendant Spirit, and replacing the watery Heads in the Well with Sabrina, goddess of the River Severn. His magician Comus is the son of Circe, and he dignified his work with plenty of other classical references.

‘The Old Wives Tale’ is not ashamed of its humble fairy and folk-tale sources. It uses them with genuine delight. I will stick out my neck and suggest that no educated people would treat common fairy tales quite like this again for the next two hundred years, or think them worth writing down. Spenser’s ‘The Faerie Queene’ was published a year after ‘The Old Wives Tale’, in 1596, and though it too takes delight in romances and fairy tales, it renders them respectable by allegorising them: the Red-Cross Knight who slays the Dragon represents Holiness conquering Sin. (So now you can enjoy the story without feeling guilty about it, because really it's doing your soul good.)

John Bunyan did the same thing in ‘The Pilgrim’s Progress’ about eighty years later. The chapter in which Christian fights and vanquishes Apollyon, for example, reads just like a fairy tale. The humble ‘old wives’ tales’ were still popular at street-level in chapbooks and ballads, but could not be taken seriously without this extra dimension. Even after the revival of interest triggered by the Grimm brothers in the first decades of the 19thcentury, it took the English a long time to turn their attention to their native tales. The Scots did better. But traces of many once-loved fairy tales that have since been lost are still visible in 16th century literature.

If you enjoyed this essay, read more like it in my book 'Seven Miles of Steel Thistles: Reflections on Fairy Tales', available in paperback and ebook from Amazon

Picture credits:

The Three Heads of the Well - Arthur Rackham

Adventures of Tom Thumb - chapbook frontispiece: wikimedia

Childe Rowland draws his sword - John Batten: illustration to Joseph Jacobs' 'English Fairy Tales'

The Red Etin of Ireland - H J Ford: illustration to The Blue Fairy Book

The Wishing Table, The Gold Ass, and The Cudgel - illustrated by Georg Mühlberg (1863-1925)