Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 4

June 6, 2023

The Woman Warrior Who Taught Cuchulain

Folklore tells that themountain ranges of Skye named the Red and Black Cuillins were namedafter the Irish hero Cuchulain, who came there to learn battle skills from thewoman warrior Scáthach, pronounced Ska’hach, with ‘ch’ as in ‘loch’. Accordingto James MacKillop’s Dictionary of CelticMythology the name means ‘shadow, shade’ (or possibly ‘shelter, protection’:but as her daughter Uathach’s name means ‘spectre’, I tend towards ‘shadow’.)The story is told in the Tochmarc Emire(‘The Wooing of Emer’), and the island of Skye was said to have been namedafter her, or after her fortress Dún Scáthaige or Scáith.

Hereare two folktales from Skye: The Islandand its Legends by Otta F Swire (OUP 1952). A native of Skye, she wrotethat these were ‘some of the old Skye stories which I heard from my mother andmany of which she, in turn, heard from a great-aunt who was born over 150 yearsago, on 18 April 1799...’ The first tale tells how the Cuillins or ‘Cuchullins’were formed, while the second is a gently humorous version of the meetingbetween Scáthach – written ‘Skiach’ to approximate the pronunciation – andCuchulain. At the end, Swire misnames Cuchulain’s terrible spear, the Gae Bolg,by calling it ‘the Fir Bolg’: the Fir Bolg however are the mythical invaders ofIreland who came before the Tuatha De Danaan. I have corrected the mistake.

When all the world wasnew, there was a great heather-clad plain between Loch Bracadale on the west,and the Red Hills on the east. It was a dark and lonely place, and theCailleach Bheur (a personification of Winter in Scottish Gaelic) whose home wason Ben Wyvis, often lived there when she came west to boil up her linen in herwashing pot, dangerous Corryvreckan. She was a very powerful and fearsomeperson who had made Scotland by dropping into the sea a creel of peat and rockwhich she had brought with her from the north. When her clothes had boiledwell, she would spread them to bleach on Storr, and while she was in Skye nogood weather was to be got at all. Now Spring hated her because she held themaiden he loved prisoner (until the girl could wash a brown fleece white) andhe fought with her, but she was strong, stronger than anyone else within thefour brown boundaries of the earth, and he could do nothing. He appealed to theSun to help him, and the Sun flung his spear at Cailleach Bheur as she walkedon the moor: it was fiery and hot it scorched the very earth, and where itstruck, a blister, six miles long and six miles wide, grew and grew until itburst and flung forth the Cuchullins as a glowing, molten mass. For many, manymonths they glowed and smoked, and the Cailleach Bheur fled away and hidbeneath the roots of a holly and dared not return. Even now, her snow isuseless against the fire hills.

*

For a long time noliving thing inhabited the Cuchulins, and then came Skiach – goddess or mortalno one knows which, but undoubtedly a great warrior. She started a school forheroes in the mountains, to teach them the art of war. Some say she took her namefrom a Gaelic name for Skye, others that Skye took its name from her. Howeverthat may be, the fame of her name and of her school spread abroad and reachedthe ears of Cuchullin, the Hero of Ulster, whose friends acclaimed him thegreatest warrior in the world. Undefeated he, single handed, had held up anarmy; so great was his battle-fury that after a fight three large baths ofice-cold water were always prepared for him: when he jumped into the first itwent off in steam; when he jumped into the second it boiled over, when hejumped into the third it became a pleasantly hot bath. On hearing that in Skyethere lived a woman, unconquered in battle, who offered to teach the heroes ofthe world how to fight, Cuchullin took two strides from the northern tip ofIreland and landed on Talisker Head; a third stride brought him to Skiach’sschool in the hills. Here he had expected to be received with awe and honour,and was much peeved to find himself treated as only a ‘new boy’, and beingfirmly snubbed all round as a boastful new boy at that.

He challenged all the other students to single combat anddefeated them. At this Skiach deigned to take notice and gave him permission tofight with her daughter... So Cuchullin and Skiach’s daughter fought ‘for a dayand a night and another day’ and then, at last, he vanquished her. Great wasthe wrath of Skiach. She for the first time descended from the high tops tofight. She and Cuchullin fought. They fought for a day and a night and anotherday, they fought on the mountains and on the moors and in the sea, but neithercould come by any advantage. Then Skiach bade all the princes and heroes watch,for never again would they see such a fight. And they fought for a day and anight and another day, but neither gained any advantage.

The Skiach’s daughter was troubled and sent some of hermaidens to bring her deer’s milk, and she made a cheese from it such as hermother loved, and bade them come and eat. But they would not. So she sentheroes to bring her a deer and she roasted it and called to them to come andeat, and it smelt very good, but theywould not. The she sent the heroes once again to gather her ‘wise’ hazel nutsfrom the trees which grow in the little burns on the side of Broc-Bheinn, andshe roasted another deer and stuffed it with roasted hazel nuts and bade themcome and eat. And Skiach thought, ‘The hazels of knowledge will teach me how toovercome Cuchullin.’ And Cuchullin thought, ‘The hazels of knowledge will teachme how to overcome Skiach.’ So they both came and sat down and ate.

When they tasted the wise hazels they knew that neithercould ever overcome the other, so they made peace together and swore that ifeither called for aid the other would come, ‘though the sky fall and crush us.’And Cuchullin returned to Ireland, but not, some say, before Skiach had givenhim the Gáe Bolg.

Notes:

This version of thestory is considerably less violent and a lot less sexy than those found in the Tochmarc Emire, as you can find out foryourself here. James MacKillop’s Dictionaryof Celtic Mythology describes the Gáe Bolg as the ‘Terrible weapon of theUlster Cycle, which entered the victim at one point but made thirty woundswithin. Deeply notched and characterized by lightning speed, Gáe Bolg was madefrom the bones of a sea-monster killed in a duel with another monster ofgreater size. Although usuallu the possession of Cuchulain, received from hisfemale tutor Scáthach, Gáe Bolg also appears in the hands of other heroes. Howit was used is still a matter of conjecture. When Cuchulain uses it to killFerdiad, he casts it ‘from the fork of his foot’, ie: between his toes.’

Picture credits:

The Black Cuillins, looking from Blaven to the west, Skye - by Nick Bramhall https://www.flickr.com/people/black_friction/

May 23, 2023

Children's Rhymes

Sometime ago I was sitting in a pub garden watching a little boy of about threetrying to play Aunt Sally - a game rather like skittles which is popular in ourbit of Oxfordshire. He was having difficulty, but eventually succeeded inhurling the heavy wooden baton (which is used instead of a ball) down the alleyat the Sally, which is a single white skittle, and knocked her down. In greatdelight he went running back to his family chanting, ‘Easy peazy lemon squeezy,easy peazy lemon squeezy!’ Iwas smiling and thinking to myself how much young children love rhyme andrhythm and word-play. Many of them, in junior school, are natural poets; you’dthink it would be dead easy to make readers out of them. What happens to thesimple joys of having fun with words?

Here’s a skipping or clapping rhyme my childrenused to chant at school. I'll show the stresses in the first few lines, but itwould be a bit much to do the whole thing. Come down heavily on the italicizedwords and you'll get it:

My mother, your mother, lives acrossthe street.

Eighteen, nineteen, Mulberry Street –

Every night they have a fight and this is what it sounded like:

Girls are sexy, madeout of Pepsi

Boys are rotten, madeout of cotton

Girls go to college toget more knowledge

Boys go to Jupiter toget more stupider

Criss, cross, applesauce,

WE HATE BOYS!

Chantedrapidly aloud, you can feel how infectious it is. Another one, also a clappinggame, runs:

I went to the Chinesechip-shop

To buy a loaf ofbread, bread, bread,

They wrapped it up ina five pound note

And this is what theysaid, said, said:

My… name… is…

Elvis Presley

Girls are sexy

Sitting on the backseat

Drinking Pepsi

Had a baby

Named it Daisy

Had a twin

Put it in the bin

Wrapped it in -

Do me a favour and –

PUSH OFF!

Isuppose every junior school in the country is home to a similar rhyme: chantedrapidly and punctuated with a flying, staccato pattern of handclaps, it’sextremely satisfying. I've heard teachers in schools get children to clap outthe rhythms of poems 'so that they can hear it' , but never anything ascomplicated as these handclapping games children make up for themselves. Noadults are involved. What unsung, anonymous geniuses between 8 and 12 inventedthese rhymes and sent them spinning around the world? Nobody analyses them, construesthem, sets them as text, or makes children learn them. Some of them go backcenturies, constantly evolving and updating. They’re for fun. Nothing but fun.

From such ordinary backgrounds sprang thegreat poet without whom we would have no ballads, no fairy tales, no myths,no legends, no Bible – all of which were made up and told aloud by Anon long before they were written down and published in big thickbooks. It's unimaginable. We’d have no proverbs, no skipping rhymes,no riddles, no jokes. People are naturals at using colourful speech: youreally and truly do not have to learn to read or write in order to expressyourself. And this reminds me of a section about ‘Children’s Folklore and GameRhymes’ in a lovely book called ‘Folklore on The American Land’ by DuncanEmrich (Little, Brown & Company, 1972). Here are some examples. Acounting-out rhyme –

Intery,Mintery, Cutery, Corn

Appleseed and apple thorn,

Wire,briar, limber-lock

Threegeese in a flock,

Oneflew east and one flew west,

Andone flew over the cuckoo’s nest,

O– U – T spells out!

So that’s where the Jack Nicholson filmtook its name from! I'd never realised. How about this exuberant skipping rhyme from a school in Washington?

Salome was a dancer

She danced before the king

And every time she danced

She wiggled everything.

‘Stop,’ said the king,

‘You can’t do that in here.’

‘Baloney,’ said Salome,

And kicked the chandelier.

And another:

Grandma Moses sick in bed

Called the doctor and the doctor said

‘Grandma Moses, you ain’t sick,

All you need is a licorice stick.’

I gotta pain in my side, Oh Ah!

I gotta pain in my stomach, Oh Ah!

I gotta pain in my head,

Coz the baby said,

Roll-a-roll-a-peep! Roll-a-roll-a-peep!

Bump-te-wa-wa, bump-te-wa-wa,

Roll-a-roll-a-peep!

Downtown baby on a roller coaster

Sweet, sweet baby on a roller coaster

Shimmy shimmy coco pop

Shimmy shimmy POP!

Shimmy shimmy coco pop

Shimmy shimmy POP!

A clapping rhyme I remember from my own schooldays went:

Have you ever ever ever in your long-legged life

Seen a long-legged sailor with a long-legged wife?

No, I’ve never never never in my long-legged life

Seen a long-legged sailor with a long-legged wife.

The second verse figured a knock-kneedsailor and a knock-kneed wife, and the third a bow-legged sailor with abow-legged wife, and, as Iona and Peter Opie recorded a child explaining (in‘The Singing Game’, OUP 1985): ‘Every time you start a new bit you put yourhands on your knees and then clap your hands together – that’s for “Have you”and “No I’ve”, because they are slow. Then you go quicker and clap against theother person’s right hand and your own hands again and the other person’s lefthand and your own hands again, and when you say “long-legged life” you separateyour arms out sideways. And when you come to “knock-kneed” and “bow-legged” youimitate those as well.’ Playing this game was a lot of fun.

Here’s a last one, comically relevant perhaps, given the recent news that the prolific Boris is to become a father again for the 8th (or 9th?) time.

The Johnsons had a baby,

They called him Tiny Tim,

They put him in a bathtub

To see if he could swim.

He drank up all the water,

He ate up all the soap,

He tried to eat the bathtub

But it wouldn’t go down his throat.

Mummy Mummy I feel ill,

Call the doctor down the hill.

In came the doctor, in came the nurse,

In came the lady with the alligator purse,

Measles said the doctor,

Mumps said the nurse,

Toothache said the lady with the alligator purse.

Out went the doctor, out went the nurse,

Out went the lady with the alligator purse.

Picture credits:

Child Skipping:

https://www.birminghammail.co.uk/news/nostalgia/look-fun-games-streets-birmingham-11184178Children playing a clapping game: Le Nomade du 21émeSiécle,Wikimedia Commons

'In came the lady with the alligator purse': from Janet and Allen Ahlberg's 'The Jolly Christmas Postman' (Heinemann, 1991)

May 12, 2023

"The Enchanted People": a poem by Lord Dunsany

It came, it came againto the scented garden,

Thecall that they would not heed,

A clear wild note farup on the hills above them,

Blownon an elfin reed.

From the heath in thehidden dells of a moorland people

It came so crystal clear

That they could nothelp a moment’s pause on their pathways,

They could not choose but hear.

The very blackbird,perched on the wall by cherries,

Ripe at the end of June,

Made never a stirthrough all of his glossy body,

Learning that unknown tune.

They needs must hear asthey walked in their valley garden,

Surely they needs must heed

That it came from afolk as magical and enchanted

As ever blew upon reed.

Surely they must arisein the heavy valley,

Sleepy with years of night,

And go to the oldimmortal things out of fable,

That danced young on the height.

But the moss was blackand old on the paths about them,

And the weeds were old and deep,

And they could notremember who were high on the uplands;

And they needed sleep.

And they thought that aday might come when someone would call them

With a song more loud and plain.

And the call rang pastlike birds going over a desert,

And it never came again.

Dunsany wrote of this poem: ‘One night in June, after I had gone to bed, there came to methe scene of a poem more vividly than one had ever come before. It is hard tosay what it is about; indeed I do not entirely know. I only know that I saw thescene very vividly, and [...] the feeling that I ought to get up and write itthere and then was as strong as the vision itself. So for the first time in mylife I got out of bed and and went downstairs to write a poem, and it camewithout any difficulty, and I feel sure that I should never have been able towrite it had I left it till morning. ... Most of my poems are simple and veryclear, but sometimes a vision may come as if from a far country.’

Picture credits:

The Horns of Elfland Faintly Blowing - by Bernard Sleigh

Faun at the Gates of Horn - by Bernard Sleigh

April 17, 2023

Naming and Identity in Myths, Legends, Fairy Tales & Fantasy

To begin near the beginning: thename Adam was originally not a proper name at all. In his book The Five Books of Moses: A Translation withCommentary, the Hebrew scholar Robert Alter remarks of Adam’s firstappearance in Genesis 1.26:

The term ’adam,afterwards consistently used with a definite article, which is used both hereand in the second account of the origins of humankind, is a generic term forhuman beings, not a proper noun. It also does not automatically suggest maleness[...]. And so the traditional rendering “man” is misleading, and an exclusivelymale ’adam would make nonsense of thelast clause of verse 27:

AndGod created the human [the ’adam] inhis image,

in theimage of God He created him,

maleand female he created them.

In case you’re thinking, ‘Waita minute, there’s a ‘him’ right therein the second line,’ Alter adds:

In themiddle clause of this verse, “him”, as in the Hebrew, is grammatically but notanatomically masculine. Feminist critics have raised the question as to whetherhere and in the second account of human origins, in chapter 2, ’adam is to be imagined as sexuallyundifferentiated until the fashioning of woman, though that proposal leads tocertain dizzying paradoxes in following the story.

I love this and feel it couldwell be true: it’s a reminder that translating a word from one language toanother is often far from straightforward. In the second chapter of Genesis,God fashions the ’adam from the ’adamah (‘the human from the soil’: anetymological pun) like a potter moulding a figure out of clay. ‘A person’ in Frenchis une personne, grammaticallyfeminine even if the person in question is male. French la table is feminine while German der tisch is masculine, but no one thinks tables are male orfemale. Grammatical gender need not and often does not correspond to biologicalgender. In any case, a clay figure hasno biological gender. Whatever it lookslike, it is asexual.

Name-giving is an act of power, 'deep magic from the dawn of time' Even to speak is to exercise that power. Fewof us choose our own names; they are given by our parents when we’re so young wecan have no say in the matter, and as Adam and Eve ‘ruled’ over the animals, parents hold authority over their children. No matter how benevolent therelationship, this is probably why when children go to school, they often abbreviatetheir names or adopt nick-names. It’s a small act of self-assertion, part of thejourney towards detaching themselves from parental rule. To change your name isin some way to change yourself.

This brings me to the OldSpeech in Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea series. In the first book, ‘A Wizard ofEarthsea’ (above, see my much-read copy of 1971) the hero Ged, whose use-name is Sparrowhawk (a true name is kept secret) arrives at the Wizards’ School onthe island of Roke to be sent with seven other apprentices to the Master Namer,Kurremkarmerruk, in the Isolate Tower.

Nofarm or dwelling lay within miles of the Tower. Grim it stood above thenorthern cliffs, grey were the clouds over the seas of winter, endless thelists and ranks and rounds of names that the namer’s eight pupils must learn.Amongst them in the Tower’s high room Kurremkarmerruk sat on a high seat,writing down lists of names that must be learned before the ink faded atmidnight leaving the parchment blank again.

Hard as this is, Ged does notcomplain. ‘He saw that in this dusty and fathomless matter of learning the truename of each place, thing and being, the power he wanted lay like a jewel atthe bottom of a dry well. For magic consists in this, the true naming of athing.’ He learns that the Old Speech is the speech of the Making, ‘thelanguage Segoy spoke who made the islands of the world’ and still spoken by dragons.We never learn much about Segoy, but in this origin myth it’s Segoy’s naming thatbrings Earthsea into existence – just as in the Book of Genesis, God brings theworld into existence.

Godsaid, ‘Let there be light,’ and there was light. [...] And God called the lightDay, and the darkness He called Night. And it was evening and it was morning,first day. And God said, ‘Let there be a vault in the midst of the waters, andlet it divide water from water.’ And God called the vault Heavens, and it wasevening and morning, second day. And God said, ‘Let the waters under theheavens be gathered in one place so that the dry land will appear.’ And so itwas. And God called the dry land Earth and the gathering of the waters Hecalled Seas...

In Genesis 2, in contrast tothe order of creation in Genesis 1, God creates animals after having created the ’adam,bringing each one of them to the human ‘to see what he would call it, andwhatever the human called a living creature, that was its name.’ It’s as though,having created human beings ‘in his own image’, God delegates the naming ofthings to them. There’s a strong hint that the naming of things – language – isan integral part of human ‘rule’ over animals. Names, or nouns, are single-word descriptions,the beginning of categorisation and a typically human and cerebral form ofknowledge. When in prehistory did spoken languages begin? Probably we’ll neverknow, but the Language of the Making , the Words of Creation – is a powerfulmyth.

In learning the true names ofthings, Ged gains power over them, a power that should be used sparingly and neverselfishly. He finds this out the hard way when prompted by pride and anger, hesummons by her name the spirit of beautiful Elfarran, a thousand years dead.And she appears.

Theshapeless mass of darkness he had lifted split apart. It sundered, and a palespindle of light gleamed between his opened arms, a faint oval reaching fromthe ground up to the height of his raised hands. In the oval of light for amoment there moved a form, a human shape: a tall woman looking back over hershoulder. Her face was beautiful, and sorrowful, and full of fear.

She is glimpsed only for amoment. Then the gap Ged has opened widens and rips ‘and through the brightmisshapen breach clambered something like a clot of black shadow, quick andhideous, and it leaped straight out at Ged’s face’, tearing and clawing him. Itcosts the life of the Archmage Nemmerle to close the gap, and for the rest ofthe book Ged is pursued by the shadow-beast he has let loose – until at last hehas the self-knowledge to claim this darkness as himself and calls it by his own name.

Many a medieval alchemist or renaissancedoctor attempted to conjure up spirits using what they conceived to be thepower of holy or unholy names. Katharine Briggs in ‘The Anatomy of Puck’ appendsa spell from Bodleian MS. Ashmole (1406) ‘To Call a Fairy’, parts of which run:

I.E.Acall the. Elaby: Gathan: in the name of the. father. of. the. son. and of theholy ghost. And. I Adjure. the. Elaby. Gathan: Conjure. and. Straightly.charge. and Command. thee. by. Tetragrammaton: Emanuell. Messias. Sether.Panton. Cratons. Alpah et Omega. [...] And. I. Conjure thee. Elaby. by. these.holy. Names. of God. Saday. Eloy. Iskyros, Adonay. Sabaoth. that thou appearpresently. meekely. and myldly. in this glasse. without. doeinge. hurt. or.daunger. unto. me. or any other. livinge. creature...

Knowledge of the fairy’s name wasonly half the battle: the magician clearly felt the need of divine protectionwhen it did appear.

An even more egregious example is given by Reginald Scot inhis scathing take-down of charlatans and superstition, ‘The Discoverie ofWitchcraft’ (1584). Of many examples, he includes a ‘prayer’ (!) forbinding and commanding angels ‘throwne downe from heaven’, which runs in part:

Irequire thee, O Lord Jesus Christ, that thou give thy virtue and power over allthine angels which were throwne downe from heaven to deceive mankind, to drawthem to me, to command them to do all they can, and that [...] they obeie meand my saiengs, and fear me. [...] and I require thee, Adonay, Amay, Horta,Vegedora, Mitai, Hel, Suranat, Ysion, Ysesy, and by all thy holie names [...]that thou enable me to congregate all thy spirits throwne down from heaven,that they may give me a true answer of all my demands, and that they satisfyall my requests, without the hurt of my bodie or soule, or anything that ismine...

The word ‘require’ in the late1580s hadn’t the force it has today; it meant something more like ‘request’ or‘desire’ – but this magician is clearly attempting to bend Christ to his willby the use of the various ‘holy’ names he attributes to him, and through Christto gain magical power over (and immunity from) devils. Talk about nerve! Someof the names look very made-up. ‘Vegedora’ sounds like a brand of softmargarine, but whatever is the Norse goddess of the underworld, Hel, doing in thatlist?

Besides summoning, itwas of course possible to banish or exorcise an evil spirit, if you knew itsname. In the Gospel of Mark, Chapter 5, Jesus casts out an ‘unclean spirit’from a madman who was living ‘among the tombs’ and whom no one could restraineven with chains, for he broke them all.

Whenhe saw Jesus from a distance, he ran and bowed down before him’ and he shoutedat the top of his voice, ‘What have you to do with me, Jesus, Son of the MostHigh God? I adjure you, by God, do not torment me.’ (For Jesus had already saidto him, ‘Come out of the man, you unclean spirit!’) Then Jesus asked him, ‘Whatis your name?’ He replied, ‘My name is Legion, for we are many.’ [...] Nowthere on the hillside a great herd of swine was feeding, and the uncleanspirits begged [Jesus], ‘Send us into the swine.’ So he gave them permission.And the unclean spirits came out and entered the swine, and the herd ... rusheddown the steep bank into the sea and were drowned.

In his book on the NewTestament, ‘Scripting Jesus’ (2010) L. Michael White points out that ‘the demonactually tries to exorcize Jesus bysaying, “I adjure you by God, do not torment me.” The word usually translated“adjure” here is the Greek orkizein(“conjure”), just as was used in demon spells.’ So, ironically, this demon tries calling onthe name of God to negate Jesus’ power. It is unable to resist when Jesusdemands its own name.

Given the belief that youcould conjure up demons or fairies by name, it’s unsurprising that magicalcharacters in fairy tales and folklore often keep their names secret. If they wereknown, others would wield power over them. In ‘The Water-Horse of Varkasaig’, a folktale from Skye, the dangerous water-horse is foiled of his prey (a youngmaiden) when the girl’s mother threatens to ‘cry his name to the four brownboundaries of the earth’ and to prove she can do it, whispers it in his ear. Onhearing it, with a terrible shriek the water-horse plunges into the river andvanishes.

Rumpelstiltskin famously tearshimself in two with rage when the young woman whose straw he has spun into goldguesses his name. Variants of the story are found across Europe, and many’s thehero or heroine who manages to wriggle out of similarly unwise bargains. In his 'Teutonic Mythology' JacobGrimm tells how King Olaf of Norway (later Saint Olaf) hired a large troll or jøtun to build him a fine church on theagreement that once it was finished, his payment should be the sun andmoon, or else Olaf himself. Olaf set conditions which he thought the troll couldnot possibly meet: the church should be so large that seven priests couldpreach in it at once without disturbing one another, and the pillars andcarvings were all to be made from the hardest flint. But soon the church wasalmost finished, with only the roof and spire left to complete. Understandably worried,Olaf ‘wandered over hill and dale, when suddenly inside a mountain he heard a childcry and a troll-woman lulling it: “Hush, hush! Thy father, Wind-and-Weather,will come home in the morning, and bring you the sun and moon, or else SaintOlaf himself!”’ Hurrying home in delight, for ‘the power of evil beings ceaseswhen their name is known’, Olaf found the troll just placing the spire on theroof. ‘Vind och veder!’ he cried, ‘du har dat spiran sneder’ – ‘Wind andWeather! You’ve set the spire on crooked!’ – upon which the troll fell off theroof and burst into a thousand pieces. All variants include this accidentaloverhearing of the supernatural helper’s name. In a Danish version, St Olaf’srole is taken by one Esbern Snare, who hears a troll woman within a hillsinging:

‘Liestill, baby mine!

Tomorrow comes Fin, father thine,

Andgiveth thee Esbern Snare’s eyes and heart to play with.’

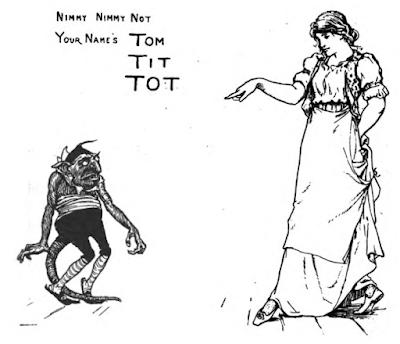

It’s possible to feel rathersorry for the trolls or imps who lose their labour (or lives!) in this way. Myfriend the writer Inbali Iserles has remarked of ‘Rumpelstiltkin’ that it is ‘astory where the greedy succeed, the victim is unsympathetic, and the villaincuriously wretched.’ But it’s hard to feel sorry for the gleeful little imp TomTit Tot, eponymous villain of the splendid Norfolk dialect version. After the Queenhas failed for the second time to guess its name (‘Is that Methuselem’ – ‘Noo,t’aint that neither’), the imp

looksat her with that’s eyes like a cool o’ fire, an’ that says, “Woman, there’sonly to-morrer night, an’ then yar’ll be mine!” n’ away te flew.

However the King her husband hasoverheard the imp’s name. Remarking casually to his wife that ‘I reckon Ishorn’t ha’ to kill you’ (seeing that she’s successfully spun the skeins eachnight so far), he sits down to supper with her and tells how out hunting hecame across a curious little black thing singing, ‘Nimmy nimmy not/My name’sTom Tit Tot’. Next day the Queen is well prepared:

[T]hat there little thing looked soo maliceful when he comefor the flax. An’ when night came she heerd that a knockin’ agin the winderpanes. She oped the winder, an’ that come right in on the ledge. That weregrinnin’ from are to are, an’ Oo! tha’s tail were twirling round so fast.

‘What’s myname?’ that says, as that gonned her the skeins.

‘Is thatSolomon?’ she says, pretending to be afeared.

‘Noo,t’ain’t,’ that says, and that come fudder inter the room.

‘Well isthat Zebedee?’ says she agin.

‘Noo,t’ain’t,’ says the impet. An’ then that laughed an’ that twirled that’s tailtill yew cou’n’t hardly see it. ‘Take time, woman,’ that says’ ‘next guess, anyou’re mine.’ An’ that stretched out that’s black hands at her.

Well, shebacked a step or two, an’ she looked at it, an’ then she laughed out, an’ saysshe, a pointin’ of her finger at it –

‘Nimmy nimmynot,

Yar name’s Tom Tit Tot.’

Wellwhen that hard her, that shruck awful an’ awa’ that flew into the dark, an’ sheniver saw it noo more.

Characters in fairy tales areoften referred to either by generic descriptions (‘the king’sdaughter’, ‘the boy’, ‘the maiden’, and so on – or by the common names of whatevercountry the tale is set in, such as Hans, Klaus, Ivan, Kate, Jack. But many fairytale names are purely descriptive. Little Red-Cap or ‘Red Riding Hood’ is so calledafter her red head-wear. The faithful servant in ‘The Frog King’ is named IronHenry because ‘he had been so unhappy when his master was changed into a frog,that he had caused three iron bars to be laid round his heart, lest it shouldburst with grief’. The names Snow-White and Rose Red describe the innocence andbeauty of the characters, and ‘The Mastermaid’ is an apt description of the lively,clever, magic-working young woman of that Norwegian story.

Sometimes these names are insulting.Cinder-lad, Aschenputtel, Tatterhood, Dummling are given their names by familieswhich despise them: but since fairy tales always favour the underdog, we knowthey’re going to succeed. The princess known as ‘Allerleihrauh’ (All Kinds of Fur) escapes fromher incestuous father dressed in a cloak of, yes, all kinds of fur. ‘Coat o’Rushes’ disguises herself in a woven reed coat after her King Lear-like fatherthrows her out, and the princess in the Norwegian fairy tale ‘Katy Woodencloak’wears a clattering cloak of wooden laths. All three serve as kitchenmaids inthese guises, and all three restore their fortunes. The names derived fromtheir actions come to define them: ‘real’ names, if they had any, would besuperfluous. It’s all very existential.

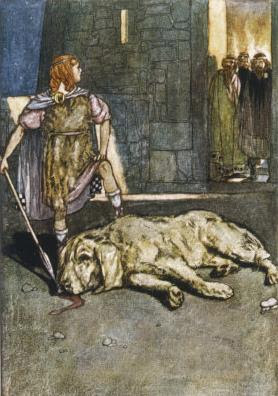

As I’ve said above, to changeyour name is to change yourself. A sevenyear-old boy called Setanta son of Sualtim (his true father is Lugh of the LongHand, Irish god of light and war) kills Culainthe Smith’s savage guard-dog. When Culain complains, the boy offers to train upanother hound for him, until which time: ‘I myself will be your watch-dog, toguard your goods and your cattle and your house.’ Hearing this, Cathbad theDruid renames the boy.

‘I could have given no better award myself,’ said Cathbadthe Druid. ‘And from this out,’ he said, ‘your name will be Cuchulain, theHound of Culain.’ ‘I am better pleased with my own name of Setanta, son ofSualim,’ said the boy. ‘Do not say that,’ said Cathbad, ‘for all the men in thewhole world will some day have the name of Cuchulain in their mouths.’ ‘If thatis so, I am content to keep it,’ said the boy. And this is how he came by thename Cuchulain.

Cuchulain of Muirthemne tr. Lady Gregory,John Murray, 1907, 11

Cuchulain’s offer ofsubstitution – ‘I will be your watch dog’ – and his new name ‘Hound of Culain’ suggeststhat from now on dogs are Cuchulain’s kindred or totem. He is laid under two geasa: never to refuse a meal offered tohim by a woman and never to eat the flesh of a dog. At the end of his life,riding out to fight against Maeve’s great army, both geasa are used against him by three witches.

After a while he saw three hags, and they blind of the lefteye, before him in the road, and they having a venomous hound they were cookingwith charms on rods of the rowan tree. And he was going by them, for he knew itwas not for his good they were there.

But one ofthe hags called to him, ‘Stop a while with us, Cuchulain.’ ‘I will not stopwith you,” said Cuchulain. ‘That is because we have nothing better than a dogto give you,’ said the hag. ‘If we had a grand, big cooking hearth, you wouldstop and visit us, but because it is only a little that we have, you will notstop.’

…Then he went over to her, and shegave him the shoulder-blade of the hound out of her left hand, and he ate itout of his left hand. And he put it down on his left thigh, and the hand thattook it was struck down, and the thigh he put it on was struck through andthrough, so that the strength that was in them before left them.

Like the actions of thosefairy tale princesses Allerleihrauh, Katy Woodencloak andCoat o’ Rushes, Cuchulain’s boyhood decision to ‘become’ Culainthe Smith’s hound triggers his renaming, and changes the course of his life.Cathbad the Druid says, ‘All the men in the whole world will some day have thename of Cuchulain in their mouths.’ Cuchulain’s future identity as a hero issomehow bound up with his acceptance of this new name.

In Ursula le Guin’s collection‘Tales From Earthsea’ there’s a wonderful story called ‘Dragonfly’, about ayoung woman who travels to the Isle of Roke hoping to enter the School forWizards. Her use-name is Dragonfly, but the Doorkeeper asks for her true name –as he asks everyone who wishes for admittance – and her true name is one she’saccepted but has never felt really comfortable with.

‘Do you know whose name you must tell me before I let youin?’

‘My own,sir. It is Irian.’

‘Is it?’ hesaid.

That gaveher pause. She stood silent. ‘It’s the name the witch Rose of my village on Waygave me, in the spring under Iria Hill,’ she said at last, standing up andspeaking truth.

TheDoorkeeper looked at her for what seemed a long time. ‘Then it is your name,’he said. ‘But maybe not all your name. I think you have another.’

‘I don’t know it, sir.’ After anotherlong time she said, ‘Maybe I can learn it here, sir.’

Irian does not find her othertrue name here on Roke; but she does discover her true nature and her power:and when Thorion the Master Summoner (who is literally a dead man walking)attempts to bind her, he fails.

Slowly he raised his arms and the white staff in invocationof a spell, speaking in the tongue that all the wizards and mages of Roke hadlearned, the language of their art, the Language of the Making: ‘Irian, by yourname I summon you and bind you to obey me!’

She hesitated, seeming for a moment toyield, to come to him, and then cried out, ‘I am not only Irian!’

The Summoner lunges at her,running up on to Roke Knoll where all things become their true selves.

Theywere both on the hill now. She towered above him impossibly, fire breakingforth between them, a flare of red flame in the dusk air, a gleam of red-goldscales, of vast wings – then that was gone, and there was nothing there but thewoman standing on the hill path and the tall man bowing down before her, bowingslowly down to the earth, and lying on it.

Thorion’s return to deathrestores the Equilibrium, although from now on there will be a new balance.Irian departs ‘beyond the west’ to find the dragons, ‘Those who will give me myname. In fire, not water. My people.’ In dragon form she springs into the airand flies, and as ‘a curl of fire, a wisp of smoke’ drifts down through thedarkening air, the men stand silent, watching. ‘What now?’ asks her friend theMaster Patterner. And the Doorkeeper of the Wizards’ School on Roke answerssimply, ‘I think we should go to our house, and open its doors.’

It is the lastline of the story. And the story is all about difference. Who is Irian? Is she indeed a woman? Can you be twothings at once? What is her truth?

In the world of Earthsea asUrsula le Guin developed it over decades, humanity and dragons were once onekind, one kindred: the dragons were there at the beginning: the Eldest, bornknowing the True Speech. Then came the Division, the separation of dragons andhumans: but some still are of both kinds. Irian is not only such a one, she isalso female, a woman, considered by most of the Mages of Roke as less than aman. ‘I am not only Irian!’ she cries, refusing to be limited to a singleidentity. So yes, the story is about difference and prejudice, about names andthe changing of names and the discovering of new identities. And it asks us notto prejudge, but to accept and open our doors to those who come to us withtheir differences. I think it is good advice.

Picture credits:

Adam and Eve in the garden with God:Hieronymous Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, c. 1490-1510

A Wizard of Earthsea, Penguin 1971, cover art &design Brian Hampton

Dr John Dee (1507-1608). Artist unknown, Ashmolean, Oxford, image from wikipedia

The Discoverie of Witchcraft, title page,British Library, image from wikipedia

Rumpelstiltskin: Walter Crane, 1886

Tom Tit Tot: English Fairy Tales by JosephJacobs, ill. John D Batten

Setanta Kills the Hound: ill. Stephen Reid, imagefrom wikipedia

April 5, 2023

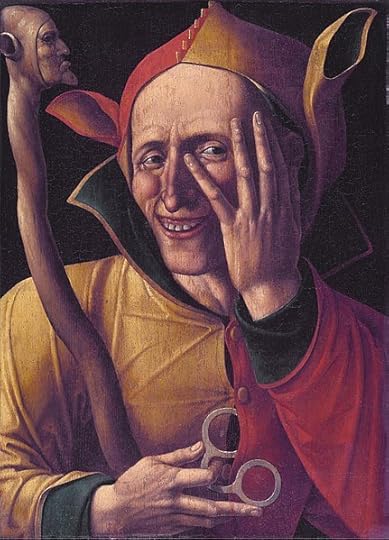

In Praise of Wise Fools and Jesters

There are fools. Thereare foolish fools and wise fools, and this essay will concern itself(mainly) with the wise ones. Foolishfools, in the oral tradition and in literature, are simpletons who makebad decisions. Granted three wishes, they squander their chances, wish forsomething as modest as a black pudding, wish it on to their partner’s noseduring a marital squabble, and use up the third wish to remove it again (‘TheThree Wishes’, ‘More English Fairytales’,Joseph Jacobs, 1894). Stories about them are intended as laughter-provokingdemonstrations of how not to behave;yet sometimes they throw light upon the unsuspected absurdities of worldlywisdom. Wise fools on the other hand are often conscious critics and iconoclastswho, from a theoretically lowly but in fact often privileged social position,turn their wit upon their masters.

Perhapsever since there have been rulers, there have been professional fools, jestersand comedians who have been given (or who have taken) license to expose andhold up to ridicule the kings, priests, presidents and public figures, thelaws, mores, prejudices, injustices and – yes – follies of the societies inwhich they live. They are a world-widephenomenon. In her book ‘Fools Are Everywhere: The Court JesterAround the World’ (2001) Beatrice K. Ottochronicles court jesters not only from Europe but also Russia, India, andImperial China. All employed the same type of impudence, requiring quick witsand strong nerves. She quotes Marais, jester to Louis XIII, remarking to hisking:

‘Il y a deux choses dans votre metier dont je ne me pourraisaccommoder … De manger tout seul et de chier en compagnie.’ [‘There are two things about your job Icouldn’t cope with – eating alone and shitting in company.’]

It isn’t just a jibe: Maraisstrikes home to a truth about the surreal world of the court. Cocooned instultifying ceremony, kings clearly found relief in the direct, disrespectful speechof their jesters, the only members of court permitted to speak to them man toman. Like the child in ‘The Emperor’s New Clothes’, Marais sees through theapparent splendour of Louis’s life, and acknowledges it as both lonely andbizarre. When Henry VIII of Englandwas given the title ‘Defender of the Faith,’ one of his jesters is reported tohave shaken his head and said to Henry (using the familiar tense), ‘Let thouand I defend one another, and let faith alone to defend itself.’ In both casesthe role of jester or fool echoes that of the slave who would stand in thetriumphal car directly behind a victorious Roman general and whisper in his earfrom time to time, ‘Remember, thou art mortal.’ The work of these jesters wasas much to keep the monarch grounded, even sane – as to keep him amused.

And a wise ruler would listen to what his fool told him. ‘King Lear’ is a play which examinesfolly and madness as closely as it does pride and ingratitude. Lear’s terriblefolly is to relinquish power and divide his kingdom between his two elderdaughters. It’s Lear’s fool who stays with him when everyone else has left him.And the fool gives good advice, as fools will.

Fool: Canst tell how an oyster makes his shell?

Lear: No.

Fool: Nor I neither; but I can tell why a snail has a house.

Lear: Why?

Fool: Why, to put his head in, not to give it away to hisdaughter and leave his horns without a case. … If thou wert my fool, nuncle,I’d have thee beaten for being old before thy time.

Lear: How’s that?

Fool: Thou shouldst not have been old before thou wert wise.

KingLear, I, vi

It’s the Fool’s privilegeto speak the truth with safety. Erasmus, in his 1509 essay The Praise of Folly, places in the mouth of the goddess Folly variouscriticisms of society and the church which if he hadn’t been able to pass offas a brilliant jeu d’esprit (it madePope Leo X laugh), might well have got him into trouble. Here he comments onthe folly of even asking (let alone answering) some of the burning questions ofthe day.

The primitive disciples were very frequent in administeringthe holy sacrament, breaking bread from house to house; yet should they beasked … the nature of transubstantiation? the possibility of one body being inseveral different places at the same time? the difference betwixt the severalaspects of Christ in heaven on the cross, and in the consecrated bread? whattime is required for the transubstantiating of the bread into flesh? how it canbe done by a short sentence pronounced by the priest? Were they asked, I say, these and severalother confused enquiries, I do not believe they could answer so readily as ourmincing school-men now-a-days take pride in doing.

ThePraise of Folly, Peter Eckler Publishing, NY 1922, p 214.

These were dangerousspeculations, yet Erasmus could point out with perfect truth that it was nothe, but Folly, who was speaking.

It’snot quite safe to laugh at a jester, or a live comedian. We know it’s best notto sit in the front row; he or she has a mastery of words and is likely to getthe better of us if we cross verbal swords with them. But the jester, dependenton his nimble wits, is only one type of wise fool. There’s another type offolly, the folly of the simpleton.

Simpletons pose no real danger to the bystander. (Ifyou’re thinking we’re all too civilised now to laugh at ‘the village idiot’,stop for a moment to consider what that laughter consisted of. Didn’t it – doesn’t it – consist of findingignorance funny? Social ignorance, lack of nous– ignorance of ‘the way things are done’? Is such laughter dead?)

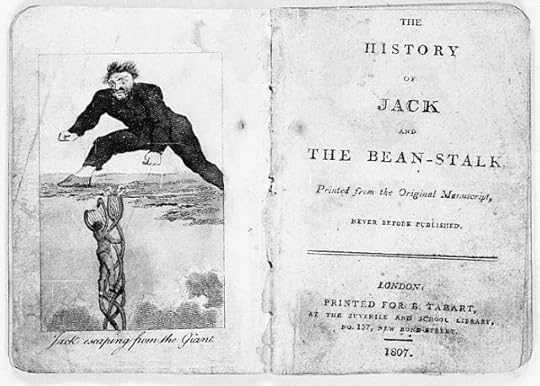

Unlike real life, in stories simple fools come upsmelling of roses. Jack and the Beanstalkis the best known example. There are different versions of this old tale, butin each of them Jack is such a simpleton, such a fool, that he sells hismother’s cow for a handful of beans which (after his angry mother hurls theminto the garden) grow up to touch the clouds.

As he was going along, he met a butcher, who enquired why he wasdriving the cow from home? Jack replied, it was his intention to sell it. Thebutcher held some curious beans in his hat; they were of various colours, andattracted Jack’s notice: this did not pass unnoticed by the butcher, who,knowing Jack’s easy temper, thought now was the time to take advantage of it,and … asked what was the price of the cow, offering at the same time all thebeans in his hat for her. The silly boy could not [sufficiently] express hispleasure at what he supposed so great an offer: the bargain was struckinstantly and the cow exchanged for a few paltry beans.

This is the first printedversion of the tale, published as ‘TheHistory of Jack and the Beanstalk’ by Benjamin Tabart in 1807. According toIona and Peter Opie in ‘The ClassicFairytales’ it is ‘the source of all substantial retellings of the story’. It’sa very literary version which includes a long, dull piece of back-storyintended to show Jack is morally justified in stealing from the Giant, who has previouslymurdered Jack’s father. Tabart also explains away Jack’s stupidity in acceptingthe beans: it was due to the magical influence of a fairy who wished to benefithim. Another literary retelling published over eighty years later by JosephJacobs in ‘English Fairy Tales’similarly attempts to dilute Jack’s folly: on meeting a ‘queer little old man’who offers him five beans for his cow, Milky-White, Jack replies with sarcasm: “Goalong,” said Jack; “wouldn’t you like it?”

The old man has to explainto him that the beans are magic and will ‘grow right up to the sky’ beforeJack will accept the bargain. It’s as though Tabart and Jacobs both found thetraditional Jack too foolish to be anattractive hero. But his folly is more than half the point, and these literaryadditions haven’t survived very well, they haven’t stuck to the story. Most ofus remember Jack as a simpleton who is cheated out of a valuable cow for ahandful of apparently worthless beans. It’s as though the beans gain theirmagical properties in response to thefolly of the hero. Ultimately, Jack wins out and the con-man loses. And themoral lesson is that sharp practice doesn’t always pay, and that good fortunewatches over the innocent and trustful.

This is a lesson repeated over and over infairytales. It’s nearly always the thirdson, the younger, slightly stupid one, whose innocence gives him the edge overhis worldly elder brothers.

There was a man who had three sons, the youngest of whom wascalled Dummling [Simpleton], and was despised, mocked and sneered at on everyoccasion.

It happenedthat the eldest wanted to go into the forest to hew wood, and before he wenthis mother gave him a beautiful sweet cake and a bottle of wine in order thathe might not suffer from hunger or thirst.

When heentered the forest he met a little grey-haired old man who bade him good-dayand said, ‘Do give me a piece of cake out of your pocket, and let me have adraught of your wine; I am so hungry and thirsty.’ But the clever son answered,‘If I give you my cake and wine, I shall have none for myself: be off withyou.’

Is the clever son reallyso clever? We know how these things go: not so very clever after all, for –

When he began to hew down a tree, it was not long before hemade a false stroke, and the axe cut him in the arm, so he had to go home andhave it bound up. And this was the little grey man’s doing.

Soon it’s the secondson’s turn. Characterised as ‘sensible’, he fares no better; and now it isDummling’s chance. His mother gives him poor fare: ‘a cake made with water andbaked in the cinders, and a bottle of sour beer’. But, when the little grey manappears, Dummling readily agrees to share his food:

and when he pulled out his cinder-cake, it was a fine sweetcake, and the sour beer had become good wine. So they ate and drank, and afterthat the little man said, ‘Since you have a good heart and are willing todivide what you have, I will give you good luck. There stands an old tree, cutit down, and you will find something at the roots.’ Then the little old mantook leave of him.

Dummlingwent and cut down the tree, and when it fell there was a goose sitting in theroots with feathers of pure gold.

You will have guessed thename of this story: it is the Grimms’ fairy tale ‘The Golden Goose’ (KHM 64) – not the goose that lays the goldeneggs, but the one which causes anyone who tries to steal its golden feathers tostick to it (and to each other) like glue. Dummling soon has a whole train of greedypeople running after him willy-nilly. Those who covet wealth, the story says,are forced to chase after it, become stuck to it in an undignified straggle. Good-heartedDummling, who shares what he has, is worthy to own the golden goose and marrythe King’s daughter.

Not all fools in folktales are wise. Stories like theGrimms’ tale ‘Frederick and Catherine’(KHM 59), set out simply to amuse the listeners with catalogues of extremefolly. In this way, even foolish fools may provide object lessons. In ‘Frederick and Catherine’ simple,literal Catherine ricochets from one domestic disaster to another.

At middayhome came Frederick:‘Now wife, what have you ready for me?’ ‘Ah, Freddy,’ she answered, ‘I wasfrying a sausage for you, but whilst I was drawing the beer to drink with it,the dog took it away out of the pan, and whilst I was running after the dog,all the beer ran out, and whilst I was drying up the beer with the flour, Iknocked over the can as well, but be easy, the cellar is quite dry again.’

In spite of the disastersshe causes, Catherine is always good tempered. Nothing upsets her, and this is true too of stories such as the Grimms’tale ‘Hans In Luck’ (KHM 89), inwhich a young man trades away his years’ wages as he journeys home, delightedwith each bad bargain he makes even when he’s left with nothing but a stone.The happiness of such characters poses a sly challenge to our own materialvalues.

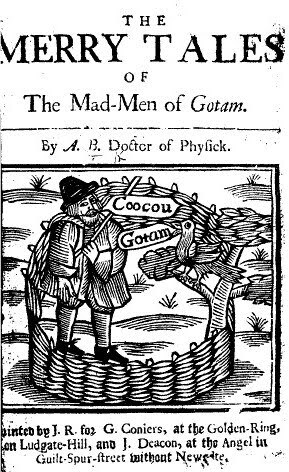

Some tales involve entire villages full of fools: peoplehave always enjoyed poking fun at their neighbours, as the old saying‘Yorkshire born and Yorkshire bred, Strong in the arm and thick in the head’bears out. (Insert any place-name you like that scans.) Typical of such storiesis this one:

The men of Austwick in Yorkshirehad only one knife between them, so they had a habit of keeping it always underone tree when it was not in use. If itwas not there when it was wanted, the man needing it called out, ‘Whittle tothe tree!’ The plan worked well untilone day a party of labourers took it to a neighbouring moor to cut their breadand cheese. At the day’s end theydecided to leave the knife there for the next day, and to mark the place whereit lay they stuck it into the ground in the shadow of a great black cloud. But the next day the cloud was gone, and sowas the whittle, and they never saw it again.

‘Whittle to the Tree’, ‘ADictionary of British Folk-tales’, Katherine Briggs, Routledge & KeganPaul 1970, Part A, Vol. Two

At least one tale slylysuggests there may sometimes be method in this kind of madness. It recounts howthe villagers of Gotham prevented King Johnfrom travelling over their meadows, because they believed any ground over whicha king passed would thereafter become a public road (the king’s highway). Theangry king sends messengers to punish this incivility, but:

The villagers … thought of an expedient to turn away hisMajesty’s displeasure. … When the messengers arrived at Gotham, they found someof the inhabitants endeavouring to drown an eel in a pool of water; some wereemployed in dragging carts upon a large barn, to shade the wood from the sun;others were tumbling their cheeses down a hill; … and some were employed inhedging in a cuckoo… in short, they were all employed in some foolish way orother, which convinced the king’s servants that it was a village of fools,whence arose the old adage, ‘the wise men’ or ‘the fools of Gotham’!

‘The Wise Men of Gotham’, ADictionary of British Folk-tales, Katherine Briggs, Routledge & KeganPaul 1970, Part A, Vol. Two

Folly may be wisdom,cloaked. This story, as so often with stories about fools, asks us to digdeeper, not to accept things at face value. In the following exchange,Shakepeare’s fool Feste demonstrates the folly of his mistress the Lady Olivia:

Feste: Good madonna, why mournest thou?

Olivia: Good fool, formy brother’s death.

Feste: I think hissoul is in hell, madonna.

Olivia: I know his soul is in heaven, fool.

Feste: The more fool,madonna, to mourn for your brother’s soul, being in heaven. Take away the fool,gentlemen.

TwelfthNight, I,v

By this neat Socraticsleight-of-hand Feste demonstrates the limitations of both philosophy andreligion, applied to the human condition. For we know very well how quickly suchstructures can crumble under the shockwave of grief. As a believing Christian,Olivia ought not to mourn her brother who is now in heaven. If she followed thelogic of the elenchos, she shouldrejoice. But grief doesn’t work like that and Feste knows it. On the otherhand, almost a year after her brother’s death perhaps it is time Olivia was teased out of what threatens literally to becomea habit of over-the-top mourning:

The element itself till seven years heat

Shall not behold her face at ample view,

But like a cloistress she will veiled walk

And water once a day her chamber round

With eye-offending brine.

TwelfthNight, I.i

What Feste begins withhis fool’s wisdom, his logical-illogical wisecracking, is a process that willeventually release Olivia from her shroud of grief. She will fall in love, andlife will go on.

‘We are fools for Christ’s sake,’ says St Paul (1Corinthians 4:10), and again: ‘For the message of the cross is foolishness tothose who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God.’(1 Corinthians 1:18). Perhaps thisechoes Christ’s message ‘Suffer the little children to come unto me and forbidthem not: for of such is the kingdom of God. Whosoever shall not receive the kingdom of God as a little child, he shall notenter heaven.’ (Mark 10:14,15).As jesters resemble children in their undeceived clear-sightedness, sosimpletons resemble children in their simplicity and innocence. Many of the stories in ‘The Little Flowers of Saint Francis of Assissi’, a compilation oforal tales about the Franciscans, feature one Brother Juniper, a complete clownwho might have walked straight out of a story like the ‘Wise Men of Gotham’ or ‘Frederickand Catherine’. Like Catherine he is utterly literal in his responses torequests and commands ... to an extent that is truly unsettling.

Once when he was visiting a sick brother at St Mary of theAngels he said to him all on fire with the charity of God, ‘Can I do thee anyservice?’ And the sick man answered, ‘Thou wouldst give me great consolation ifthou couldst get me a pig’s foot to eat.’

Brother Juniper hurriesinto the forest with a knife, finds a herd of swine, cuts off a foot from oneof them and runs back to prepare and cook it for the sick man. The angry swineherdfollows and complains of his action to St Francis, who berates Brother Juniper:‘Wherefore hast thou given this great scandal?’

At these words Brother Juniper was much amazed, wonderingthat anyone should have been angered at so charitable an action, for alltemporal things appeared to him of no value, save in so far as they could becharitably applied to the service of our neighbour.

The Little Flowers of Saint Francis ofAssissi, tr. Lady Georgina Fullerton, 1864

We miss the point if ouronly response is to wince on behalf of the pig. The Franciscan view of animalswas a religious not a sentimental one, and animal rights lay a long, long wayin the future. Whoever wrote this fable down fully expects the contemporaryreader to regard Brother Juniper’s action as great folly (you don’t mutilatelive pigs) and to understand St Francis’s anger. And yet we are asked to see his folly as saintly, to put aside ourusual habits and enter a mindset which quite simply views all things, everything – as belonging already toGod. ‘He would be a good Friar,’ said St Francis, ‘who had overcome the worldas perfectly as Brother Juniper’. Brother Juniper’s single-minded concentrationon God is at once ridiculous, frightening – and holy. Fools and saints are a bit frightening. They don’toperate by the normal rules. When we look at their actions we are sometimesstartled into questioning our own. And that has been the purpose of fools down theages – holding up the glass of folly to reflect back the image of what wethought was wisdom. Are you a fool? Am I?

Lear: Dost thou call me a fool, boy?

Fool: All thy other titles thou hast given away. That, thouwast born with.

KingLear, I, iv

[This essay, and others on fairy tales and folklore, can be found in my book: 'Seven Miles of Steel Thistles' available on Amazon at this link.]

Picture credits

Laughing jester, c 1500, possibly Jacob Cornelisz. van Oostanen wikipedia

Miniature of David and his fool, from the psalter of Henry VIII (likenesses of Henry himself and, probably, Will Summers). British Library

King Lear and his Fool in the Storm, William Dyce, c 1851 wikipedia

Jack and the Beanstalk, 1807 frontispiece wikimedia commons

The Golden Goose, Walter Crane, 1886 wikimedia commons

The Mad-Men of Gotham: 16th C. chapbook

Portrait of the Ferrara court jester Gonella, Jean Fouqet 1445 wikipedia

March 2, 2023

The Water-Horse of Varkasaig

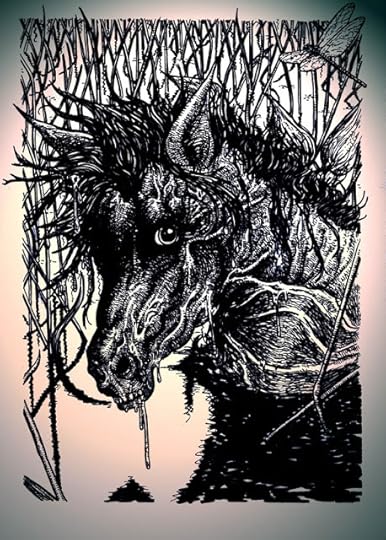

'Water-Horse' by Andrew Paciorek

'Water-Horse' by Andrew Paciorek

This tale about a water-horse is taken from ‘Skye: The Island and its Legends’ by Otta F. Swire (Oxford University Press, 1952). Varkasaig is on Loch Bharcasaig (same name, different spelling) on the north-west coast of Skye. ‘Crowdie’ is gruel, a ‘shieling’ is a rough hut or shelter built on a piece of pasture and a ‘cailin’ is a girl (like the Irish ‘colleen’). I love the wonderful, evocative phrase with which the mother threatens the kelpie.

Orbost and Varkasaig are both said to be Scandinavian place-names, Orbost being ‘the homestead of the seals’, of which a great number once haunted the bay, and Varkasaig being ‘the place of the great jumping beast’, though this, I fear, is too good to be true. This refers to an ‘Each Uisge’ or water-horse which lives in the stream.

At one time there was a shieling not far from the burn and here an old woman and her daughter came one summer to herd the cows. One night there was a great storm of thunder, lightning, and rain. When the storm was at its height there came a knocking at the door of the shieling: the girl hastened to open it and found on the threshold a very handsome young man, well dressed but dripping wet, who begged for shelter. Rather thrilled, the girl invited him in and offered him a place by the fire and some oatcake and crowdie. He accepted both, then settled himself near the maiden with his head on her lap, where she sang him to sleep.

When he slept the old woman handed her a comb and,very gently, she began to comb his hair. As the wise woman expected, it was full of sand and small shells. Then they knew him for what he was – a water-horse. The frightened girl gently moved his head on to a bundle of unspun wool her mother brought her, and slipped out of the house to cross the burn, knowing that no supernatural creature can pursue across running water. But the hut was some way from the burn side and in a few moments the young man awoke: when he realised what had happened he at once resumed his horse’s shape and, roaring with fury, pursued the maiden in great leaps and jumps. Her mother was beforehand with him, however, and threw a naked knife in his path. As he paused she came up with him and said: ‘If you pursue the cailin I will cry your name to the four brown boundaries of the earth’, and she whispered his name. What it was or how she knew it has never been told, but the effect was instantaneous; with a terrible shriek the water-horse rushed to the burn side, plunged into the deep pool by the bridge, and vanished.

It is said that, ignorant that the old woman has long since died, he has never again dared to venture far from his burn lest she name him, but those who go quietly on a fine summer evening may perchance see him frolicking all alone on the sand at the river mouth; and colts born in the valley exceed all others in strength and swiftness. But other say that the ‘Each Uisge’ made a pact with the wise woman, that every tenth year the burn should bring him a living sacrifice so long as he remained beneath its waters.

Picture credit:

'Water-Horse' by kind permission of Andrew Paciorek: http://www.batcow.co.uk/strangelands/water.htm

February 16, 2023

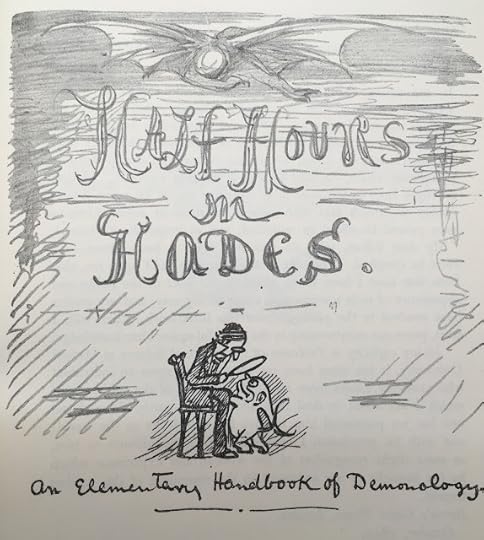

Half-Hours in Hades, and The Screwtape Letters

I have made a discovery, or at least a possible discovery. Maybe others have made it before, but it is new to me: in 1891 at the age of seventeen G.K. Chesterton, then a pupil at St Paul’s School London, wrote and illustrated a witty natural history (or supernatural history?) of devils, which he called ‘Half-Hours In Hades: An Elementary Handbook of Demonology’. It opens with a preface by the supposed author, a ‘Professor of Supernatural Science’:

In the autumn of 1890, I was leaving the Casino at Monte Carlo in company wth an eminent Divine, whose name, for obvious reasons, I suppress. We were engaged in an interesting discussion on the subject of Demons, he contending that they were an unnecessary, not to say prejudicial, element in our civilisation, an opinion which, needless to say, I strongly opposed. Having at length been so fortunate as to convince him of his error, I proceeded to furnish him with various instances in which Demons have proved beneficial to mankind, and at length he exclaimed, ‘My dear fellow, why do you not write a book about – ’ Here he coughed. The idea took so strong a hold upon me that from that time I have taken careful note of the the habits and appearance of such specimens as come in my way, and my studies have resulted in the production of this little work, which will, I trust, prove not uninteresting to the youthful seeker after knowledge.

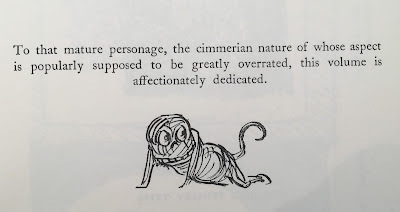

With its casually ludicrous opening in which a professor and a clergyman exit the Casino at Monte Carlo deep in a discussion about demons, and its spoof faux-academic style, this is a polished piece of writing from a boy of seventeen. Daring, too, especially when the so-called Professor goes on to dedicate his work to – well, to Lucifer:

In my capacity as Professor of Supernatural Science at Oxford University, it has often been my duty to call upon an individual who probably knows more about all branches of the subject with which I am about to deal than any man on earth, although no one has yet persuaded him to give his knowledge to the world, and with his permission I have dedicated these pictures to him, as some slight recognition of the wisdom and experience which he has brought to my assistance in the compiling of this modest treatise.

The word ‘cimmerian’ being unknown to me (see above), I looked it up in the Shorter Oxford Dictionary, which provides the meaning: ‘Of or belonging to the Cimmerii, a people fabled by the ancients to live in perpetual darkness. Hence, an epithet of dense darkness.’ Where young Chesterton came across it I don’t know but lo! the rewards of a classical education. He went on to write three ‘chapters’ of this short but lively treatise. The first and longest concerns ‘The Five Primary Types’ of demons and their habits:

For those who love the study of Demonology (and I pity the man or woman who does not) it possesses an interest which will remain after health, youth and even life have departed.

I love the sinister, dead-pan humour of this assertion, delivered as though demonology were a hobby as ordinary as stamp-collecting. Chesterton, or his professor, now introduces us to ‘The Common (or “Garden”) Serpent ... so-called because its first appearance in the world took place in a Garden. Since that time its proportions have dwindled considerably, but its influence and power have largely increased; it is found in almost everything.’

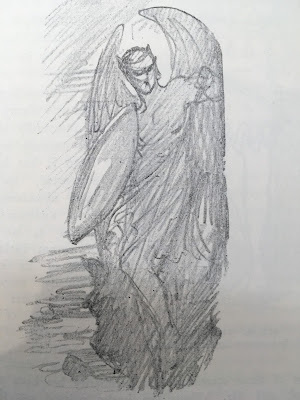

Beside it comes the Mediaeval Demon, ‘whose horns, tail and claws form a remarkable contrast to the serpentine formation of the first type.’

It is ... the subject rather of playfulness and household merriment rather than abhorrance, while the far cleverer and more graceful serpent is the object of a cruel and unreasoning persecution. But useful as the mediaeval species is found at the present day as a general source of amusement, it has of late somewhat failed to stir public interest, which is turned towards newer and more elegant varieties. Mr. J. Milton, in his interesting and valuable work on this subject, has discussed at some length the leading characteristics of a fine species of which he was primarily the discoverer... This magnificent animal measures at least four roods, and when floating full length on the warm gulf, of which it is an inhabitant, has been compared by its discoverer to a whale.*

You get the picture. Accounts of the ‘Red Devil’ (Diabolus Mephistopheles), and the ‘Blue Devil’ (Caerulius Lugubrius) follow, while Chapter 2, ‘The Evolution of Demons’ is comprised mainly of cartoons (Chesterton’s inventive powers perhaps temporarily exhausted). Here they are:

Chapter 3, ‘What We Should All Look For’, is a dialogue between mother and child which begins, ‘But, mamma, can we all see devils?’ – ‘Certainly, Charlotte, if we take the trouble’ – and ends with a lesson in which 'Mamma' demonstrates how to raise a demon from a cauldron.

‘Do you see those two round green orbs of light, Jane? ... Do not scream, Charlotte, for that would be very naughty, and would perhaps frighten the little creatures, as they are very timid. By this time, children, you may perceive the outline of an attenuated figure, resembling in some respects that of a skeleton, though the ears, which you can now see moving, show that this is not the case. Lift little Harry up, James, since he is too small to see over the edge of the cauldron.’

I don’t know for sure but would guess that Chesterton probably wrote ‘Half-Hours in Hades’ to amuse his fellow schoolboys, but years later he considered it strong enough to deserve inclusion in his collection of stories and essays ‘The Coloured Lands’ (Sheed & Ward, 1938), and I think he was right. It is daring, funny and satirical, as when ‘mamma’ tells her child that the vicar, Dr. Brown, is the proud owner of a varied collection of demons.

‘But, mamma’ [the child asks] ‘does Dr Brown love his little pets?’ – ‘I have reason to believe that he is fondly attached to them. They are never out of his sight and he has often said that he has gleaned many useful lessons from their habits. In fact he says that he would not be the man he is but for them, and one glance at Dr. Brown will make it clear this is no exaggeration.’

You may agree with me by now that Half-Hours in Hades in some ways resembles C.S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters which, though written 50 years later, employs much the same kind of satire and dead-pan humour. In Letter XV, for example, Screwtape describes two churches he considers suitable for the damnation of his nephew Wormwood’s ‘patient’:

I think I warned you before that if your patient can’t be kept out of the Church, he ought at least to be violently attached to some party within it. I don’t mean on really doctrinal issues; about those, the more luke-warm he is the better. … The real fun is working up hatred between those who say ‘mass’ and those who say ‘holy communion’ when neither party could possibly state the difference between, say, Hooker’s doctrine and Thomas Aquinas’, in any form that would hold water for five minutes.

And in Lewis's introduction to the letters – ‘I have no intention of explaining how the correspondence which I now offer to the public fell into my hands’ – his pretence of their extraneous diabolic origin echoes the claim of Chesterton’s ‘professor’ to have gathered hisknowledge from the Authority on that subject.But did Lewis ever actually read Half-Hours in Hades? According to a letter written Sunday July 21, 1940 to his brother Warnie, the idea of a correspondence between devils occurred to him in church:

Before the service was over – one could wish these things came more seasonably – I was struck by an idea for a book which I think might be both useful and entertaining. It would be called ‘As one Devil to Another’ ... the idea would be to give all the psychology of temptation from the other point of view...

His biographers Roger Lancelyn Greene and Walter Hooper record that when Hooper once asked ‘if there were any book which had given him the idea for The Screwtape Letters,’ Lewis showed him one I have never heard of, Confessions of a Well-Meaning Woman by Stephen McKenna (1922) in which (as Lewis explained) the same moral inversion occurs, along with ‘the humour which comes of speaking through a totally humourless person.’ He did not mention Chesterton as any kind of inspiration. All the same, Lewis read many of Chesterton’s works, including his essays, and Christian apologetics such as Orthodoxy (1908) and The Everlasting Man (1925), praising the latter as ‘the best popular defence of the full Christian position I know.’

Though Chesterton was more than twenty years Lewis’s senior, the two men had plenty in common. Both wrote popular novels and poetry as well as essays and theology, and both filtered Christianity through the mesh of fiction. Chesterton’s ‘Father Brown’ detective tales are concerned with sin and repentence, justice, mercy and the love of God. Lewis’s Narnia stories introduce the same concerns to a younger audience. Both men were fluent, charismatic writers blessed with the ability to communicate, a sense of humour and the common touch. Chesterton delivered a series of radio lectures for the BBC in the 1930s; Lewis did the same during the war years. As a writer and a public figure, Chesterton was impossible to miss; and it is not unlikely that Lewis might have obtained a copy of the The Coloured Lands when it came out in 1938, and enjoyed Half-Hours in Hades, Chesterton’s jeu d’esprit.

If he had though, wouldn’t he have said? First, he might simply have forgotten: he was a busy man with a lot going on. The Screwtape Letters were originally published one per week from May to November 1941 in a High Church periodical, The Guardian (not the newspaper, then known as The Manchester Guardian); Lewis donated the £2 fee for each installment to a fund for the widows of clergymen. He had begun his wartime broadcasts on ‘Mere Christianity’ and was writing Voyage to Venus (Perelandra), plus the lectures on Milton which subsequently became A Preface to Paradise Lost. Child evacuees had arrived at his Oxford home, The Kilns, and he was still actively tutoring students. Second, The Screwtape Letters has psychological depth beyond the reach of the teenage Chesterton, and a structure and purpose that Half-Hours in Hades lacks. Writers borrow all the time; they cannot credit all their sources, and G.K. Chesterton’s reputation did not depend on a piece of clever but ultimately inconsequential juvenilia. Did it once sow a seed in Lewis's imagination? We may never know, but the possibility is fascinating.

* Thus Satan, talking to his nearest mate,

With head uplift above the wave, and eyes

That sparkling blazed; his other parts besides

Prone on the flood, extended long and large,

Lay floating many a rood, in bulk as huge

As whom the fables name of monstrous size,

Titanian or Earth-born, that warred on Jove,

Briareos or Typhon, whom the den

By ancient Tarsus held, or that sea-beast

Leviathan, which God of all his works

Created hugest that swim th’ ocean-stream.

Paradise Lost, Book 1

Picture credits:

All artwork by G.K. Chesterton.

February 9, 2023

Janet Speaks

‘Oh Tam Lin –

If I had known of this night’s deed

I would have torn out your two grey eyes

And put back in two eyes of tree.’

So said the faerie queen that night on the road

when I quenched my love in the peat pool,

but that was not the end of it.

For winter nights, the Sithe shriek round the house,

calling down the chimney like a black wind

plucking the slates away, ‘Come back, Tam Lin!

You who gave a girl a rose from the briar bush!

The heart’s fire dwindles. Do you remember Elf-hame?

And my love, my love throws back the blanket,

and I grip his arm as I gripped the red-hot iron

in unflinching hands.

‘Tam Lin, can you bear to grow old?

Do you remember the land of young apples?

What have you lost, what have you gained, Tam Lin,

but aches and agues, toothlessness and death?’

howl the voices down the chimney.

They always bring a night of storm, and all

my paternosters cannot turn them away.

‘Come wind, come rain,

beat on this house until the lintels weep,

beat on this house until the candles quiver

and cold draughts whip under the door and blow

over the floor, cross-currents of unease.

Let him feel mortal!’

I could bear all this.

Only, my youngest boy came in today

with a rose in his hand. ‘Who gave you that?’ said I.

‘O mother,’ said he, ‘a lady in the brakes

of Carterhaugh. Her kirtle green as grass,

with silver chains that tinkled as she walked.’

‘Your son shall come with me, Janet,

In yon green hill to dwell.

Your son shall be my knight, Janet,

And he shall serve me well.

‘His eyes shall be of wood, Janet,

Cut from an alder tree,

And you may keep Tam Lin, Janet,

For he’s too old for me.’

It’s a hard price.

I would rather have died in giving birth to him.

I would rather my love rose and went out to them.

Oh Queen of Fays –

if I had known of this day’s deed

I would have let your knight, Tam Lin,

ride down to hell on his milk-white steed.

Copyright Katherine Langrish 2011

Picture credit: Thomas Rhymer and the Queen of Faerie (detail) - Joseph Noel Paton, 1821 - 1901

December 20, 2022

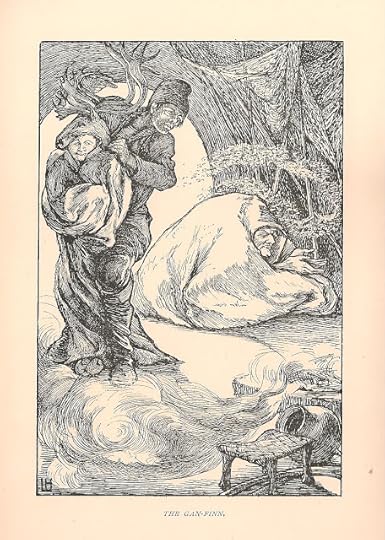

"Jack of Sj��holm and the Gan-Finn" by Jonas Lie

This wintry and veryeerie ghost story is by the 19th century Norwegian writer Jonas Lie. A contemporaryof Henrik Ibsen, born 1833 at Hvokksund not far from Oslo, he spent much of hischildhood at Troms��, inside the Arctic Circle. He was sent to navalcollege, but poor eyesight unsuited him for a life at sea, so he became alawyer and began to write and publish poems and novels reflecting Norwegian life,folklore and nationalism ��� though written in Danish, the official language of Norway till the early 20th century. I was lucky enough tofind in a second hand bookshop ���Weird Tales From Northern Seas���, a collectionof his tales based on Norwegian and Finnish legends about the sea, translated byR. Nisbet Bain (Kegan Paul, 1893).

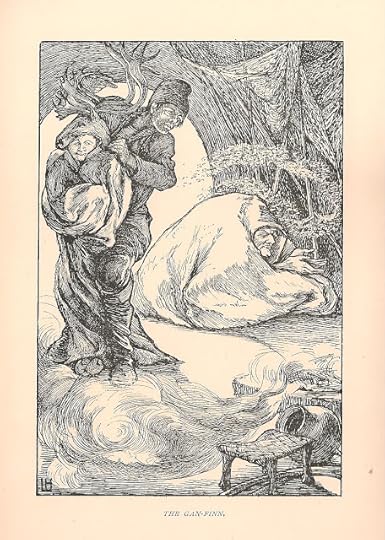

���Jack of Sj��holm andthe Gan-Finn��� is one of his best tales, by turns grim, lyrical, haunting, and ultimatelycompassionate. Jack is an over-confident young man whose ambition is to save lives by building betterboats, but his life becomes twisted after he meets the Gan-Finn and the undeadhaunter of the seas, the Draug.

The illustration above is by Laurence Housman and the translation is by R.Nisbet Bain.

In the days ofour forefathers, when there was nothing but wretched boats up in the Nordland,and folks must needs buy fair winds by the sackful from the Gan-Finn,it was not safe to tack about in the open sea in wintry weather. In those daysa fisherman never grew old. It was mostly women-folk and children, and the lameand halt, who were buried ashore.

Now there was once a boat���s crewfrom Thj��tt�� in Helgeland, which had put out to sea, and worked its way rightup to the East Lofotens.

But that winter the fish would notbite.

They lay to and waited week afterweek, till the month was out, and there was nothing for it but to turn homeagain with their fishing gear and empty boats.

But Jack of Sj��holm, who was withthem, only laughed aloud and said that, if there were no fish there, fish wouldcertainly be found higher northwards. Surely they hadn���t rowed out all thisdistance only to eat up all their victuals, said he.

He was quite a young chap, who had neverbeen out fishing before. But there was some sense in what he said for all that,thought the head fisherman.

And so they set their sailsnorthwards.

On the next fishing ground theyfared no better than before, but they toiled away so long as their food heldout. And now they all insisted on giving it up and turning back.

���If there���s none here, there���s sureto be some still higher up towards the north,��� opined Jack; and if they hadgone so far they might surely go a little further.

So they tempted fortune from fishingground to fishing ground, till they had ventured right up to Finmark.But there a storm met them, and try as they might to find shelter under theheadlands, they were obliged at last to put out into the open sea again.

There they fared worse than ever.Again and again the prow of the boat went under the heavy rollers, and later inthe day the boat foundered.

Then they all sat helplessly on thekeel in the midst of the raging sea, and they all complained bitterly againstthat fellow Jack, who had tempted them on and led them to destruction. Whatwould become of their wives and children? They would starve now they had no oneto care for them.

When if grew dark their hands beganto stiffen, and they were carried off by the sea one by one.

And Jack heard and saw everything,down to the last shriek and the last clutch; and to the very end they neverceased reproaching him for bringing them to such misery, and bewailing theirsad lot.

���I must hold on tight now,��� saidJack to himself, for he was better even where he was than in the sea. And so hetightened his knees on the keel, and held on till he had no feeling left ineither hand or foot.