In Praise of Wise Fools and Jesters

There are fools. Thereare foolish fools and wise fools, and this essay will concern itself(mainly) with the wise ones. Foolishfools, in the oral tradition and in literature, are simpletons who makebad decisions. Granted three wishes, they squander their chances, wish forsomething as modest as a black pudding, wish it on to their partner’s noseduring a marital squabble, and use up the third wish to remove it again (‘TheThree Wishes’, ‘More English Fairytales’,Joseph Jacobs, 1894). Stories about them are intended as laughter-provokingdemonstrations of how not to behave;yet sometimes they throw light upon the unsuspected absurdities of worldlywisdom. Wise fools on the other hand are often conscious critics and iconoclastswho, from a theoretically lowly but in fact often privileged social position,turn their wit upon their masters.

Perhapsever since there have been rulers, there have been professional fools, jestersand comedians who have been given (or who have taken) license to expose andhold up to ridicule the kings, priests, presidents and public figures, thelaws, mores, prejudices, injustices and – yes – follies of the societies inwhich they live. They are a world-widephenomenon. In her book ‘Fools Are Everywhere: The Court JesterAround the World’ (2001) Beatrice K. Ottochronicles court jesters not only from Europe but also Russia, India, andImperial China. All employed the same type of impudence, requiring quick witsand strong nerves. She quotes Marais, jester to Louis XIII, remarking to hisking:

‘Il y a deux choses dans votre metier dont je ne me pourraisaccommoder … De manger tout seul et de chier en compagnie.’ [‘There are two things about your job Icouldn’t cope with – eating alone and shitting in company.’]

It isn’t just a jibe: Maraisstrikes home to a truth about the surreal world of the court. Cocooned instultifying ceremony, kings clearly found relief in the direct, disrespectful speechof their jesters, the only members of court permitted to speak to them man toman. Like the child in ‘The Emperor’s New Clothes’, Marais sees through theapparent splendour of Louis’s life, and acknowledges it as both lonely andbizarre. When Henry VIII of Englandwas given the title ‘Defender of the Faith,’ one of his jesters is reported tohave shaken his head and said to Henry (using the familiar tense), ‘Let thouand I defend one another, and let faith alone to defend itself.’ In both casesthe role of jester or fool echoes that of the slave who would stand in thetriumphal car directly behind a victorious Roman general and whisper in his earfrom time to time, ‘Remember, thou art mortal.’ The work of these jesters wasas much to keep the monarch grounded, even sane – as to keep him amused.

And a wise ruler would listen to what his fool told him. ‘King Lear’ is a play which examinesfolly and madness as closely as it does pride and ingratitude. Lear’s terriblefolly is to relinquish power and divide his kingdom between his two elderdaughters. It’s Lear’s fool who stays with him when everyone else has left him.And the fool gives good advice, as fools will.

Fool: Canst tell how an oyster makes his shell?

Lear: No.

Fool: Nor I neither; but I can tell why a snail has a house.

Lear: Why?

Fool: Why, to put his head in, not to give it away to hisdaughter and leave his horns without a case. … If thou wert my fool, nuncle,I’d have thee beaten for being old before thy time.

Lear: How’s that?

Fool: Thou shouldst not have been old before thou wert wise.

KingLear, I, vi

It’s the Fool’s privilegeto speak the truth with safety. Erasmus, in his 1509 essay The Praise of Folly, places in the mouth of the goddess Folly variouscriticisms of society and the church which if he hadn’t been able to pass offas a brilliant jeu d’esprit (it madePope Leo X laugh), might well have got him into trouble. Here he comments onthe folly of even asking (let alone answering) some of the burning questions ofthe day.

The primitive disciples were very frequent in administeringthe holy sacrament, breaking bread from house to house; yet should they beasked … the nature of transubstantiation? the possibility of one body being inseveral different places at the same time? the difference betwixt the severalaspects of Christ in heaven on the cross, and in the consecrated bread? whattime is required for the transubstantiating of the bread into flesh? how it canbe done by a short sentence pronounced by the priest? Were they asked, I say, these and severalother confused enquiries, I do not believe they could answer so readily as ourmincing school-men now-a-days take pride in doing.

ThePraise of Folly, Peter Eckler Publishing, NY 1922, p 214.

These were dangerousspeculations, yet Erasmus could point out with perfect truth that it was nothe, but Folly, who was speaking.

It’snot quite safe to laugh at a jester, or a live comedian. We know it’s best notto sit in the front row; he or she has a mastery of words and is likely to getthe better of us if we cross verbal swords with them. But the jester, dependenton his nimble wits, is only one type of wise fool. There’s another type offolly, the folly of the simpleton.

Simpletons pose no real danger to the bystander. (Ifyou’re thinking we’re all too civilised now to laugh at ‘the village idiot’,stop for a moment to consider what that laughter consisted of. Didn’t it – doesn’t it – consist of findingignorance funny? Social ignorance, lack of nous– ignorance of ‘the way things are done’? Is such laughter dead?)

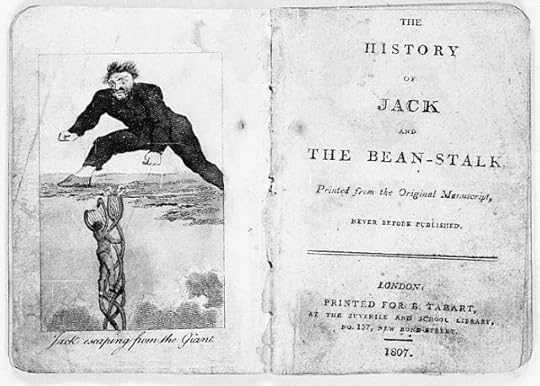

Unlike real life, in stories simple fools come upsmelling of roses. Jack and the Beanstalkis the best known example. There are different versions of this old tale, butin each of them Jack is such a simpleton, such a fool, that he sells hismother’s cow for a handful of beans which (after his angry mother hurls theminto the garden) grow up to touch the clouds.

As he was going along, he met a butcher, who enquired why he wasdriving the cow from home? Jack replied, it was his intention to sell it. Thebutcher held some curious beans in his hat; they were of various colours, andattracted Jack’s notice: this did not pass unnoticed by the butcher, who,knowing Jack’s easy temper, thought now was the time to take advantage of it,and … asked what was the price of the cow, offering at the same time all thebeans in his hat for her. The silly boy could not [sufficiently] express hispleasure at what he supposed so great an offer: the bargain was struckinstantly and the cow exchanged for a few paltry beans.

This is the first printedversion of the tale, published as ‘TheHistory of Jack and the Beanstalk’ by Benjamin Tabart in 1807. According toIona and Peter Opie in ‘The ClassicFairytales’ it is ‘the source of all substantial retellings of the story’. It’sa very literary version which includes a long, dull piece of back-storyintended to show Jack is morally justified in stealing from the Giant, who has previouslymurdered Jack’s father. Tabart also explains away Jack’s stupidity in acceptingthe beans: it was due to the magical influence of a fairy who wished to benefithim. Another literary retelling published over eighty years later by JosephJacobs in ‘English Fairy Tales’similarly attempts to dilute Jack’s folly: on meeting a ‘queer little old man’who offers him five beans for his cow, Milky-White, Jack replies with sarcasm: “Goalong,” said Jack; “wouldn’t you like it?”

The old man has to explainto him that the beans are magic and will ‘grow right up to the sky’ beforeJack will accept the bargain. It’s as though Tabart and Jacobs both found thetraditional Jack too foolish to be anattractive hero. But his folly is more than half the point, and these literaryadditions haven’t survived very well, they haven’t stuck to the story. Most ofus remember Jack as a simpleton who is cheated out of a valuable cow for ahandful of apparently worthless beans. It’s as though the beans gain theirmagical properties in response to thefolly of the hero. Ultimately, Jack wins out and the con-man loses. And themoral lesson is that sharp practice doesn’t always pay, and that good fortunewatches over the innocent and trustful.

This is a lesson repeated over and over infairytales. It’s nearly always the thirdson, the younger, slightly stupid one, whose innocence gives him the edge overhis worldly elder brothers.

There was a man who had three sons, the youngest of whom wascalled Dummling [Simpleton], and was despised, mocked and sneered at on everyoccasion.

It happenedthat the eldest wanted to go into the forest to hew wood, and before he wenthis mother gave him a beautiful sweet cake and a bottle of wine in order thathe might not suffer from hunger or thirst.

When heentered the forest he met a little grey-haired old man who bade him good-dayand said, ‘Do give me a piece of cake out of your pocket, and let me have adraught of your wine; I am so hungry and thirsty.’ But the clever son answered,‘If I give you my cake and wine, I shall have none for myself: be off withyou.’

Is the clever son reallyso clever? We know how these things go: not so very clever after all, for –

When he began to hew down a tree, it was not long before hemade a false stroke, and the axe cut him in the arm, so he had to go home andhave it bound up. And this was the little grey man’s doing.

Soon it’s the secondson’s turn. Characterised as ‘sensible’, he fares no better; and now it isDummling’s chance. His mother gives him poor fare: ‘a cake made with water andbaked in the cinders, and a bottle of sour beer’. But, when the little grey manappears, Dummling readily agrees to share his food:

and when he pulled out his cinder-cake, it was a fine sweetcake, and the sour beer had become good wine. So they ate and drank, and afterthat the little man said, ‘Since you have a good heart and are willing todivide what you have, I will give you good luck. There stands an old tree, cutit down, and you will find something at the roots.’ Then the little old mantook leave of him.

Dummlingwent and cut down the tree, and when it fell there was a goose sitting in theroots with feathers of pure gold.

You will have guessed thename of this story: it is the Grimms’ fairy tale ‘The Golden Goose’ (KHM 64) – not the goose that lays the goldeneggs, but the one which causes anyone who tries to steal its golden feathers tostick to it (and to each other) like glue. Dummling soon has a whole train of greedypeople running after him willy-nilly. Those who covet wealth, the story says,are forced to chase after it, become stuck to it in an undignified straggle. Good-heartedDummling, who shares what he has, is worthy to own the golden goose and marrythe King’s daughter.

Not all fools in folktales are wise. Stories like theGrimms’ tale ‘Frederick and Catherine’(KHM 59), set out simply to amuse the listeners with catalogues of extremefolly. In this way, even foolish fools may provide object lessons. In ‘Frederick and Catherine’ simple,literal Catherine ricochets from one domestic disaster to another.

At middayhome came Frederick:‘Now wife, what have you ready for me?’ ‘Ah, Freddy,’ she answered, ‘I wasfrying a sausage for you, but whilst I was drawing the beer to drink with it,the dog took it away out of the pan, and whilst I was running after the dog,all the beer ran out, and whilst I was drying up the beer with the flour, Iknocked over the can as well, but be easy, the cellar is quite dry again.’

In spite of the disastersshe causes, Catherine is always good tempered. Nothing upsets her, and this is true too of stories such as the Grimms’tale ‘Hans In Luck’ (KHM 89), inwhich a young man trades away his years’ wages as he journeys home, delightedwith each bad bargain he makes even when he’s left with nothing but a stone.The happiness of such characters poses a sly challenge to our own materialvalues.

Some tales involve entire villages full of fools: peoplehave always enjoyed poking fun at their neighbours, as the old saying‘Yorkshire born and Yorkshire bred, Strong in the arm and thick in the head’bears out. (Insert any place-name you like that scans.) Typical of such storiesis this one:

The men of Austwick in Yorkshirehad only one knife between them, so they had a habit of keeping it always underone tree when it was not in use. If itwas not there when it was wanted, the man needing it called out, ‘Whittle tothe tree!’ The plan worked well untilone day a party of labourers took it to a neighbouring moor to cut their breadand cheese. At the day’s end theydecided to leave the knife there for the next day, and to mark the place whereit lay they stuck it into the ground in the shadow of a great black cloud. But the next day the cloud was gone, and sowas the whittle, and they never saw it again.

‘Whittle to the Tree’, ‘ADictionary of British Folk-tales’, Katherine Briggs, Routledge & KeganPaul 1970, Part A, Vol. Two

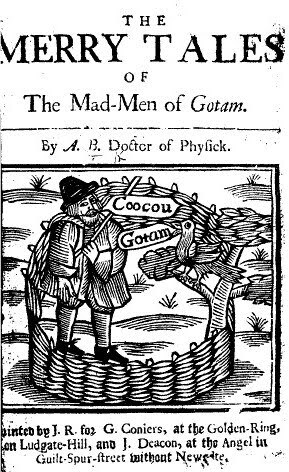

At least one tale slylysuggests there may sometimes be method in this kind of madness. It recounts howthe villagers of Gotham prevented King Johnfrom travelling over their meadows, because they believed any ground over whicha king passed would thereafter become a public road (the king’s highway). Theangry king sends messengers to punish this incivility, but:

The villagers … thought of an expedient to turn away hisMajesty’s displeasure. … When the messengers arrived at Gotham, they found someof the inhabitants endeavouring to drown an eel in a pool of water; some wereemployed in dragging carts upon a large barn, to shade the wood from the sun;others were tumbling their cheeses down a hill; … and some were employed inhedging in a cuckoo… in short, they were all employed in some foolish way orother, which convinced the king’s servants that it was a village of fools,whence arose the old adage, ‘the wise men’ or ‘the fools of Gotham’!

‘The Wise Men of Gotham’, ADictionary of British Folk-tales, Katherine Briggs, Routledge & KeganPaul 1970, Part A, Vol. Two

Folly may be wisdom,cloaked. This story, as so often with stories about fools, asks us to digdeeper, not to accept things at face value. In the following exchange,Shakepeare’s fool Feste demonstrates the folly of his mistress the Lady Olivia:

Feste: Good madonna, why mournest thou?

Olivia: Good fool, formy brother’s death.

Feste: I think hissoul is in hell, madonna.

Olivia: I know his soul is in heaven, fool.

Feste: The more fool,madonna, to mourn for your brother’s soul, being in heaven. Take away the fool,gentlemen.

TwelfthNight, I,v

By this neat Socraticsleight-of-hand Feste demonstrates the limitations of both philosophy andreligion, applied to the human condition. For we know very well how quickly suchstructures can crumble under the shockwave of grief. As a believing Christian,Olivia ought not to mourn her brother who is now in heaven. If she followed thelogic of the elenchos, she shouldrejoice. But grief doesn’t work like that and Feste knows it. On the otherhand, almost a year after her brother’s death perhaps it is time Olivia was teased out of what threatens literally to becomea habit of over-the-top mourning:

The element itself till seven years heat

Shall not behold her face at ample view,

But like a cloistress she will veiled walk

And water once a day her chamber round

With eye-offending brine.

TwelfthNight, I.i

What Feste begins withhis fool’s wisdom, his logical-illogical wisecracking, is a process that willeventually release Olivia from her shroud of grief. She will fall in love, andlife will go on.

‘We are fools for Christ’s sake,’ says St Paul (1Corinthians 4:10), and again: ‘For the message of the cross is foolishness tothose who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God.’(1 Corinthians 1:18). Perhaps thisechoes Christ’s message ‘Suffer the little children to come unto me and forbidthem not: for of such is the kingdom of God. Whosoever shall not receive the kingdom of God as a little child, he shall notenter heaven.’ (Mark 10:14,15).As jesters resemble children in their undeceived clear-sightedness, sosimpletons resemble children in their simplicity and innocence. Many of the stories in ‘The Little Flowers of Saint Francis of Assissi’, a compilation oforal tales about the Franciscans, feature one Brother Juniper, a complete clownwho might have walked straight out of a story like the ‘Wise Men of Gotham’ or ‘Frederickand Catherine’. Like Catherine he is utterly literal in his responses torequests and commands ... to an extent that is truly unsettling.

Once when he was visiting a sick brother at St Mary of theAngels he said to him all on fire with the charity of God, ‘Can I do thee anyservice?’ And the sick man answered, ‘Thou wouldst give me great consolation ifthou couldst get me a pig’s foot to eat.’

Brother Juniper hurriesinto the forest with a knife, finds a herd of swine, cuts off a foot from oneof them and runs back to prepare and cook it for the sick man. The angry swineherdfollows and complains of his action to St Francis, who berates Brother Juniper:‘Wherefore hast thou given this great scandal?’

At these words Brother Juniper was much amazed, wonderingthat anyone should have been angered at so charitable an action, for alltemporal things appeared to him of no value, save in so far as they could becharitably applied to the service of our neighbour.

The Little Flowers of Saint Francis ofAssissi, tr. Lady Georgina Fullerton, 1864

We miss the point if ouronly response is to wince on behalf of the pig. The Franciscan view of animalswas a religious not a sentimental one, and animal rights lay a long, long wayin the future. Whoever wrote this fable down fully expects the contemporaryreader to regard Brother Juniper’s action as great folly (you don’t mutilatelive pigs) and to understand St Francis’s anger. And yet we are asked to see his folly as saintly, to put aside ourusual habits and enter a mindset which quite simply views all things, everything – as belonging already toGod. ‘He would be a good Friar,’ said St Francis, ‘who had overcome the worldas perfectly as Brother Juniper’. Brother Juniper’s single-minded concentrationon God is at once ridiculous, frightening – and holy. Fools and saints are a bit frightening. They don’toperate by the normal rules. When we look at their actions we are sometimesstartled into questioning our own. And that has been the purpose of fools down theages – holding up the glass of folly to reflect back the image of what wethought was wisdom. Are you a fool? Am I?

Lear: Dost thou call me a fool, boy?

Fool: All thy other titles thou hast given away. That, thouwast born with.

KingLear, I, iv

[This essay, and others on fairy tales and folklore, can be found in my book: 'Seven Miles of Steel Thistles' available on Amazon at this link.]

Picture credits

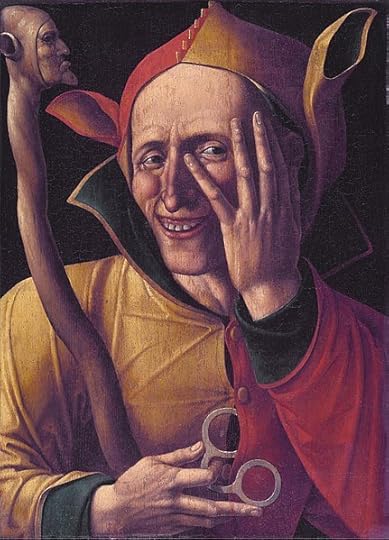

Laughing jester, c 1500, possibly Jacob Cornelisz. van Oostanen wikipedia

Miniature of David and his fool, from the psalter of Henry VIII (likenesses of Henry himself and, probably, Will Summers). British Library

King Lear and his Fool in the Storm, William Dyce, c 1851 wikipedia

Jack and the Beanstalk, 1807 frontispiece wikimedia commons

The Golden Goose, Walter Crane, 1886 wikimedia commons

The Mad-Men of Gotham: 16th C. chapbook

Portrait of the Ferrara court jester Gonella, Jean Fouqet 1445 wikipedia