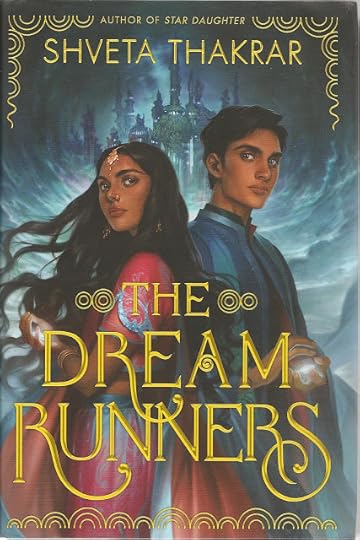

'Nagas and Garudas, Dreams and Stars', a guest post by Shveta Thakrar

I’m delighted to welcome forthe second time to my blog the author Shveta Thakrar, whose second YA novel TheDream Runners was published by HarperCollins last year. I thoroughly enjoyed herdebut novel Star Daughter and this one's even better. Shvetaweaves into her YA fantasies all kinds of mystical beings from Hindu legends and sacred texts, and Holly Black describes her writing as ‘beautiful as starlight’. In this post, Shveta retells the story of the enmity between the nagas and garudas, describesthe creative thinking behind her novel, and challenges us toconsider ways to turn old enmities into friendships.

#

We all know aboutfaerie courts. Night Courts and Bright Courts, Seelie and Unseelie. But what ofnagas and garudas?

TheDream Runners, the second in my Night Market triptych of YA fantasynovels based on various aspects of Hindu mythology, started out as an answer tothat question. I’d finished all work on StarDaughter, and my editor reached out to ask me what was next. I tooksome time to ponder that. I knew I loved changelings and faerie courts, but Iwasn’t ready to stop writing about Hindu mythology and folklore when I’d reallyonly just begun.

Garuda devouring a naga

Garuda devouring a nagaThen it struck me: I already knew of a similar scenario,that of the ancient mythical war between the nagas—serpent shape-shifters—andtheir cousins and mortal enemies, the garudas—eagle shape-shifters. With suchsharp lines of division, these two groups might as well be two opposing courts.In fact, since I am a storyteller, allow me now to tell you their tale.

#

(There are, of course,different variations and even different narratives, but this is the version Ilearned as a child. And if you enjoy it, I highly recommend seeking out aseries of comic books called AmarChitra Katha, which recount many Indian myths and legends.)

Long, long ago, in the time of the Mahabharata,there were two sisters, the elder called Vinata and the younger Kadru, daughters of Lord Daksha. Wed to the samerishi—sage—Kashyapa, bothsisters bore children by him after requesting that boon: Vinata gave birth totwo eggs, which contained Arun, who laterbecame Lord Surya’scharioteer, and Garuda,while Kadru gave birth to a thousand eggs, from which emerged the first nagas.

One day, Kadru, known for her wily nature, challengedVinata to name the color of the tail of Uchchaihshravas, thedivine horse born from SamudraManthan, the churning of the Cosmic Ocean of Milk.However, the wager came with a cost: should Vinata answer incorrectly, she andher son would then become enslaved to Kadru and her brood. If she answeredcorrectly, the reverse would be true. The question seemed simple enough, and asthe seven-headed horse was radiantly white from head to toe, Vinata guessed thathis equine tail was white.

But Kadru had been scheming. She sent her children, thenagas, to cover Uchchaihshravas’s tail, then brought her sister to see him.“Black,” she pronounced, and her unfortunate sister had no choice but to agree.

The humiliation of being proven wrong would have been unpleasantbut bearable, had that been the only consequence. Of course, it was not, and soVinata and Garuda began their indenture, waiting upon her sister and her niecesand nephews. Watching his mother endure their abuse was an indignity Garudacould not accept, and from that day forward, he nursed a grudge against hiscousins, stoking the fires of his hatred.

At last, having grown mighty, with a wingspan that couldblock the sun, he demanded of Kadru that she free Vinata. Kadru, naturally, woulddo no such thing without a price: the amrit from the heavenly realmof Svargalok. Garuda then fought all the gods in the realm, even Lord Indra,and came away with the nectar. Kadru freed her sister and instructed Garuda to distributethe amrit amidst her children.

Garuda returns with the vase of Amrita

Garuda returns with the vase of AmritaHowever,Lord Indra had beseeched him not to grant it to the nagas, so instead, Garudacommanded them to wash and purify themselves before they could imbibe. Whilethey did so, Indra’s son, Jayanta,stole the vessel back. When the nagas returned, Garuda consumed them all.

(Yetin the contradictory way of mythology, there are still more nagas and later arace of garudas, who continue this enmity forever more.)

And that, gentle reader, is why eagles eat snakes.

#

I’ve always beenfascinated by this story—and the antics people get up to when they have no truepurpose driving them—so it shouldn’t come as a surprise that I had initiallyused it in my first attempt at a novel, now trunked. But when my editor camecalling, it occurred to me that I could cannibalize elements from that trunkednovel and incorporate them into what became The Dream Runners. By then, Ihad become a skilled enough writer to do the myth justice.

Thatoriginal attempt featured a human main character named Sameer, who becamerelegated to a tertiary character in The Dream Runners, while hisgirlfriend, the delightful and audacious nagini Princess Asha, now took on agreater role as a secondary character. I also—of course—resurrected the magicalbar with its enchanted libations such as silver wine (distilled moonlight) and setit in the Night Market from Star Daughter, thus connecting the two books.

Meanwhile, two new characters, Tanvi, a dream runner whostarts waking up, and Venkat, the dreamsmith she previously sold her harvesteddreams to in return for a beloved bracelet, ran away with the story of boonsand dreams and arranged marriages between naga clans, all set against thebackdrop of the mythological war between the garudas and the nagas.

And so, The Dream Runners became my lovingfanfiction of the original myth.

#

Myths exist for manyreasons, one of which is to reflect our lives back to us. I cannot help but seethe connections between things, and I think a lot about interpersonalcommunication, empathy, and what plays out on the world stage when we forget thatwe’re connected and view others as our rivals, if not as our enemies. When weforget that, as the Sanskrit saying goes, we are all one world family: वसुधैव कुटुम्बकम (vasudhaiva kutumbakam), we harm both others andourselves.

As in the myth, that fundamental truth getsdismissed again and again in a dog-eat-dog global society focused on greed forthe few at the cost of the rest. Though I didn’t intend it, there’s definitelyan anticapitalist slant to The Dream Runners. I might not have realized that’swhat I was writing in Tanvi and her harvesting, but I stand by it.

So,returning to the matter at hand: What do you do once a war has calcified intowhat appears to be inevitability, and seemingly unmovable, unbreachable lineshave been drawn? When you hurt me, so now I must hurt you, and because I hurtyou, you will now hurt me?

How do we break old cycles of violence and hatred?

Iwon’t spoil how my characters choose to solve that problem, but I personallybelieve that we need to find answers to these questions. Our worlddepends on it. I wrote The Dream Runners to be a magical escape for myreaders, to celebrate Hindu mythology and shine a spotlight on the beingslesser known in the West, but also to get us to consider if there might be alternativesto the way it’s always been. If we can write a new ending to an old story.

Iinvite you to start writing yours.

Picture credits

The Dream Runners by Shveta Thakrar, HarperTeen. Cover art by Charlie Bowater

Garuda devouring a naga: Painting at the Temple of the Emerald Buddha, Bangkok, Wikipedia

Uchchaihshavras: origin unknown: https://www.quora.com/What-is-known-about-Uchchaihshravas

Garuda returns with the vase of Amrita: V&A collections