The Silver Apples of the Moon, the Golden Apples of the Sun

This was our apple tree last September, so laden with fruit that branches actually cracked and broke off under the weight, as though taking Keats’ lines from Ode to Autumn far too literally –

To bend with apples the mossed cottage-treesAnd fill all fruit with ripeness to the core…

The lawn was almost ankle deep in windfalls.

What is it about apples? Why are they so evocative? Why was the fruit of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil – not actually named in the Bible – assumed to be an apple? Why did the Firebird, in Russian folklore, steal golden apples from the garden of the Czar? Why did golden apples of immortality grow in the Garden of the Hesperides, why was the Norse goddess Idun the keeper of golden apples which preserved the youth of the gods? Why was the Apple of Discord – with its inscription To the Fairest – an apple, and why were three golden apples so irresistible to Atalanta that she paused to pick them up and lost her race? (Mind you, that dress she's wearing wouldn't help.)

The apple as the fruit of immortality, or perhaps equally of death, appears as a symbol in Celtic mythology too. Heralds from the Land of Youth might bear a silver apple branch, with silver blossom and golden fruit whose tinkling music lulled the hearers to sleep – perhaps to everlasting sleep. Arthur, after his final battle, went to the island of Avalon, the island of apples, to be healed of his mortal wound. Then of course there’s the apple given by the wicked Queen to Snow-White, one bite of which sends the little princess into a death-like sleep.

Apples are tokens of love and promises of eternity. In Yeat’s ‘The Song of Wandering Aengus’, the lovelorn Aengus seeks forever the beautiful girl from the hazel wood.

Though I am old with wanderingThrough hollow lands and hilly landsI find out where she has gone,And kiss her lips and take her hands;And walk among long dappled grassAnd pluck till time and times are done,The silver apples of the moon,The golden apples of the sun.

But such an eternity is probably also the land beyond death.

Where do apples even come from, why are they so ubiquitous? Why, even today, are so many varieties available even in supermarkets, usually the home of homogeneity? I went into our local Sainsburys the other day and counted eleven different named varieties of apple all on sale at once: Empire, Royal Gala, Red Delicious, Golden Delicious, Cox’s Orange Pippin, Russets, Granny Smiths, Pink Ladies, Jazz, Braeburns and Bramleys. By contrast, there were only four named varieties of pears, and everything else was generic – bananas, strawberries, oranges, etc.

Apples are related to roses, I’m delighted to tell you. According to a rather lovely book called ‘Apples: the story of the fruit of temptation’, by Frank Browning (Penguin 1998):

‘In the beginning there were roses. Small flowers of five white petals opened on low, thorny stems, scattered across the earth in the pastures of the dinosaurs, about eighty million years ago. …These bitter-fruited bushes, among the first flowering plants on earth, emerged as the vast Rosaceae family and from them came most of the fruits human beings eat today: apples, pears, plums, quinces, even peaches, cherries, strawberries, raspberries and blackberries.

‘The apple [paleobotanists believe]… was the unlikely child of an extra-conjugal affair between a primitive plum from the rose family and a wayward flower with white and yellow blossoms of the Spirea family, called meadowsweet.’

Isn’t that wonderful? Apples as we know them today developed in Europe and Asia. The Pharoahs grew them. The Greeks and Romans grew them. And they keep. You can store apples overwinter, eat them months after you’ve picked them: fresh fruit in hard cold weather when there’s nothing growing outside. So perhaps you would think of them as life-giving, immortal fruit. They smell fragrant. They feel good too: hard-fleshed, smooth, a cool weight in the hand.

The medieval lyric 'Adam lay y-bounden' provocatively celebrates the Fall of Man when Adam ate the forbidden fruit:

And all was for an appil An appil that he tokeAs clerkes findenWritten in her boke.

It ends on the mischievously subversive thought that if Adam had not eaten the apple, Our Lady would never have become the Heavenly Queen:

Blessed be the timeThat appil take was!Therefore we maun singen:Deo gratias.

Here is a poem by John Drinkwater (surely the most poetically-named poet ever!) which captures some of those mystical coincidences of apples, eternity, sleep, moonlight, magic and death.

MOONLIT APPLES

At the top of the house the apples are laid in rows,And the skylight lets the moonlight in, and those Apples are deep-sea apples of green. There goesA cloud on the moon in the autumn night.

A mouse in the wainscot scratches, and scratches, and thenThere is no sound at the top of the house of menOr mice; and the cloud is blown, and the moon againDapples the apples with deep-sea light.

They are lying in rows there, under the gloomy beamsOn the sagging floor; they gather the silver streamsOut of the moon, those moonlit apples of dreamsAnd quiet is the steep stair under.

In the corridors under there is nothing but sleep.And stiller than ever on orchard boughs they keepTryst with the moon, and deep is the silence, deepOn moon-washed apples of wonder.

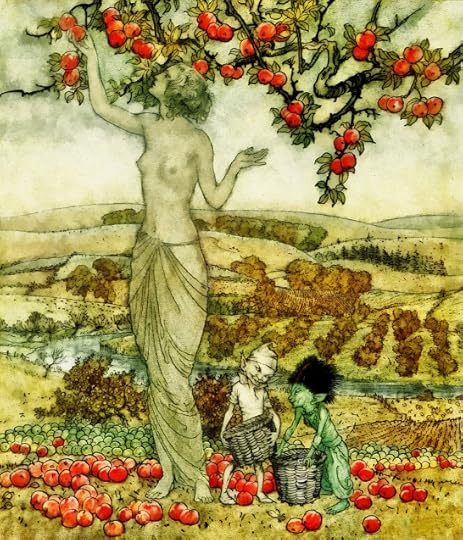

Picture credits:

Apple tree: Author's gardenAtalanta racing Hippomenes: Willen van Herp, c1650Silver Apples: Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh

Adam and Eve: Lucas Cranach, 1537Apple Tree: Arthur Rackham

Labels: Apple of discord, Apples, Eden, Forbidden fruit, John Drinkwater, Katherine Langrish, Keats, Tree of Knowledge, Yeats

Published on June 23, 2021 03:38

No comments have been added yet.