Tim Prasil's Blog, page 7

March 11, 2024

Lunch with Vera #1: Vera Van Slyke’s Advice Column for the Spectrally Troubled

I’ve only been able to learn the basics about where and when Vera Van Slyke lived. She was born in 1868, not too far from Tarrytown, New York, where she spent her childhood. In the mid- to late-1880s, she traveled down the Hudson to New York City, where she began her journalism career and met her mentor in paranormal investigation, Harry Escott. She relocated to Chicago in 1900, her room at the Hotel Manitou serving as home and freelance-reporting headquarters. In 1909, she embarked on what became a four-year tour of Britain and the European Continent. Funded by the Morley Foundation, an organization promoting psychical research, she crossed the Atlantic to test her theory about strong guilt puncturing the membrane between the physical and spiritual realms and, thereby, allowing for ghosts and other paranormal phenomena. Upon her return in 1913, Van Slyke again settled in New York City, specifically, the Harlem neighborhood.

That’s when things get murky. I know that, in 1923, Van Slyke was still living in Harlem and that she and my great-grandaunt, Ludmila Bergson, remained in touch. This is revealed in The Hound of the Seven Mounds, the chronicle of an investigation Van Slyke conducted that year. However, after this point, I lose the trail of where the great ghost hunter might have roamed. My ancestor had described her as having a restless spirit, so I half-assumed she might again head west — maybe even farther west than Chicago.

Vera Van Slyke (1868-1941) and Ludmila “Lida” Bergson (1882-1958), née Prášilová, a.k.a. Lucille Parsell

Vera Van Slyke (1868-1941) and Ludmila “Lida” Bergson (1882-1958), née Prášilová, a.k.a. Lucille ParsellTurns out, I was right. By the late 1930s, around the time Van Slyke would have reached 70 years old, she was residing in the coastal village of Ferness, in the State of Washington. I know this because a reader of the Vera Van Slyke ghostly mysteries contacted me. He’s a journalism student in Seattle who happens to be engaged in a historical study of advice columns — and he discovered that Van Slyke wrote one! It was titled “Lunch with Vera,” and it appeared in the local newspaper, the Ferness Drum. My new friend graciously included digital scans of several of the articles, which unfortunately aren’t available online.

Here’s where it get interesting. Along with addressing a variety of other topics, Van Slyke gave advice to readers experiencing problems related to — you guessed it — ghosts! In the months to come, I’ll be transcribing these articles (unless, of course, I’m ordered to cease-and-desist for copyright reasons. As I understand it, newspaper articles from the 1930s are in a gray area in terms of public domain.)

I’ll start with a fairly short, representative article. It comes from the August 10, 1938, issue.

Dear Vera,

My husband works nights at a salmon cannery. Nights are also when our resident ghost declares its presence with footsteps in empty rooms, with whispery singing, and by standing perfectly still while barely seen at the far end of our main hallway. As it happens, I’ve grown accustomed to these displays. They no longer upset me, and truth be told, I now appreciate having some company.

However, on those nights when he’s free, my husband finds our supernatural visitor unnerving. He insists that we rid ourselves of this “demon freeloader.” He is a man of action and deep feeling, my husband, and I dare say he’s even given signs of being jealous of my nightly companion.

Please, Vera, how do I convince him that this is an undaunting haunting?

Signed — Not Alone Nights

Dear Not Alone Nights,

If possible, try to find a neighbor who has lived on your block for a good while. After assuring this person that you find the situation to be, as you charmingly phrase it, “an undaunting haunting,” ask about any former resident of your house or apartment, one now deceased. Disembodied footsteps and faint visual apparitions in dark spaces are fairly routine, but the singing might be helpful in regard to identification. With luck, mentioning this will remind your neighbor of, let’s say, a church choir member who died in your home.

Next, provide your husband with the story behind the haunting. I have discovered that knowing someone’s biography — whether the individual has a heartbeat or not — is a remarkable first step toward overcoming ill will, be it rooted in fear, distrust, or unfounded jealousy. Knowing something about a stranger’s experiences pokes a peephole into that person’s soul, so to speak, and it may go a long way toward changing your husband’s mind, transforming his “demonic freeloader” into something much less threatening.

Now, let’s consider the stabbing pangs of guilt that allow your ghost to appear in the first place. I can’t help but be struck by the peculiarity of a man being jealous of a ghost! Is it possible your deep-feeling husband sorely regrets leaving you alone at night? I’ve handled cases in which self-reproach has twisted outward into suspiciousness and, yes, jealousy. If you think this might be the case, assure him that you love him for the sacrifices he makes to support you and that your ghost — instead of being a competitor in his absence — is, in truth, a comforter during those times.

As I say, I will share more of these unusual articles in the future. In the meanwhile, if learning something of Vera Van Slyke’s biography has poked a peephole into a stranger’s soul, my advice is to start with Help for the Haunted: A Decade of Vera Van Slyke Ghostly Mysteries, though her two book-length chronicles stand on their own.

Click on the cover above to learn more about the Vera Van Slyke Ghostly Mysteries.

Click on the cover above to learn more about the Vera Van Slyke Ghostly Mysteries.— Tim

March 4, 2024

On Curating Crime: Why William Le Queux Made Me All Sad

Almost certainly, the fourth volume of the Curating Crime Collection will be called The Complete Crimes of Romney Pringle, and it will combine all of Clifford Ashdown’s stories featuring career criminal, Romney Pringle. Ashdown’s Pringle tales are consistently good fun in that stretching-reality, sometimes-downright-goofy way that draws me and I hope many other readers to this subgenre of mystery fiction.

Almost certainly, the fifth volume will include Miriam Michelson’s short novel In the Bishop’s Carriage. It’s a fast-paced drama of a woman trying very hard to abandon a criminal past for an acting career, and Michelson — who served as a drama critic along with being a popular fiction writer — manages to create the feel of a French farce. I like it a lot! But it’s not long enough to be the whole book. And finding something else to combine with Michelson is proving to be a bit of a challenge.

Bored People Are Boring PeopleOne contender was Arnold Bennett’s The Loot of Cities. This short series of stories features Cecil Thorold, a gentleman thief who’s wealthy, sophisticated — and terribly bored. Thorold combats his ennui by committing crime. Boredom is a potentially interesting motivation, I guess, but it’s difficult to sustain readers’ interest in such a character. Bored people are boring people, after all. Bennett might have recognized this because, by the fourth and fifth tales in the series, Thorold has become the victim of an elaborate crime rather the perpetrator of one. The sixth and final adventure involves a (very, very) complex scheme to attend a gala theatrical performance, which strikes me as a petty crime at best.

Is there a negative form of “curated”? I de-curated The Loot of Cities.

John Cameron’s illustration of Cecil Thorold being asked about his stolen watch appeared in Windsor Magazine.A Promising to Saddening Choice

John Cameron’s illustration of Cecil Thorold being asked about his stolen watch appeared in Windsor Magazine.A Promising to Saddening ChoiceNow, if the name William Le Queux rings a bell, it’s probably because of his role in establishing spy fiction. His 1906 novel The Invasion of 1910 depicts a war between England and Germany, and it was published eight years before WWI. The Count’s Chauffeur (1907) can be seen as Le Queux’s contribution to that wave of crime fiction from which I’m curating my “9-volume anthology” called the Curated Crime Collection.

And The Count’s Chauffeur starts out with a lot of promise! While Michelson’s In the Bishop’s Carriage illustrates a character struggling to escape the crime world, Le Queux spotlights one being seduced into that lifestyle. This trajectory, though, might’ve been an afterthought. It’s not until well toward the end of the book that narrator George Ewart, who has been hired to drive Count Bindo and his partners in crime, muses:

Before my engagement as the Count's chauffeur I think I was just as honest as the average man ever is; but there is an old adage which says that you can't touch pitch without being besmirched, and in my case it was, I suppose, only too true. I had come to regard their ingenious plots and adventures with interest and attention, and marvelled at the extraordinary resource and cunning with which they misled and deceived their victims. ...Had this composite novel consistently charted Ewart’s gradual corruption, it might’ve been better. Not Macbeth or Lord of the Flies, needless to say. But better.

But no. Instead, Le Queux’s chauffeur loses direction and swerves to settings and adventures of a very different type. About halfway through the book, Ewart leaves aiding and abetting behind, becoming — like Cecil Thorold — a victim of crime and circumstance. A tale titled “The Red Rooster,” I’ll admit, is very intriguing in and of itself. Ewart finds himself entangled in a pogrom in Poland, and here, a Jewish character’s noble self-sacrifice reveals an awareness of that group’s persecution that I haven’t seen before in British literature of this period. Sadly, though, it has nothing to do with Ewart’s succumbing to a life of crime or with the kind of stuff that makes up the Curated Crime Collection.

Cyrus Cuneo’s illustration for The Count’s Chauffeur appeared in Cassell’s Magazine.

Cyrus Cuneo’s illustration for The Count’s Chauffeur appeared in Cassell’s Magazine.As my disappointment rose in terms of Le Queux giving me a solid piece of crime fiction — perhaps not entirely his intention — he seemed to grow inconsistent even within the tales themselves. In “The Lady in a Hurry,” we first read Ewart’s assessment of a brand new character named Julie Rosier: “There was nothing of the police spy or adventuress about her. On the contrary, she seemed a very charmingly modest young woman.” Our narrator contradicts himself a mere two pages later: “At first I had been conscious that there was something unusual about her, and suspected her to be an adventuress.” Dude! Le Queux! Why ya gotta do this to me? Were you rushing to meet a deadline?

Again: de-curated!

The Count’s Chauffeur certainly has its interests. It is consistent if there were a genre called Buzzing About in a Newfangled Motorcar fiction. Unfortunately, in terms of late-1800s/early-1900s fiction featuring criminals — i.e., Professor Moriarty‘s competition — it’s not up to snuff.

So the curation continues…

–Tim

February 19, 2024

Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit: A Phantom Locomotive at Rittman, Ohio

As Wrecks Go…

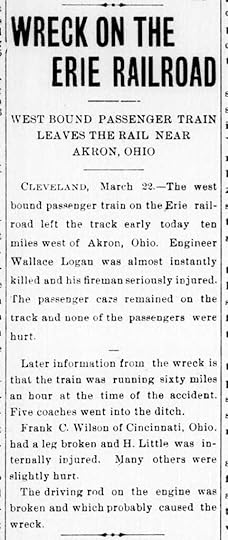

As Wrecks Go…On March 22, 1899, a westbound train derailed near Rittman, Ohio. One source reports that the train had been running at 60 miles an hour, and a later one explains that speeding along this stretch of the Erie Railroad allowed engineers to stay on schedule. Unfortunately, on that run in March, the No. 5 broke a driving rod, which probably lead to the wreck. (Another source uses the term “parallel rod,” but clearly it was some sort of engine trouble.) With even greater speed, news of the tragedy reached Washington, D.C., later that same day and California the very next.

As the No. 5 was veering off the rails, Engineer Alexander Wallace Logan bravely kept his hand on the throttle, sacrificing his life to save passengers and other crew members. He was honored as a hero. Though it received national attention, this single-fatality tragedy was comparatively minor — at least, as late-1800s/early-1900s train wrecks go. For instance, in 1876, a train plummeted 70 feet from a collapsing bridge into Ohio’s Ashtabula River, killing around 90 passengers.

One of the best early reports of the wreck appeared on the front page of the March 22, 1899, issue of The Huntington Advertiser, a West Virginia newspaper.

One of the best early reports of the wreck appeared on the front page of the March 22, 1899, issue of The Huntington Advertiser, a West Virginia newspaper.Even so, in October of the same year, a phantom train was witnessed by John Faber, a local doctor, and his companion. The spectral manifestation came again in 1901, this time being observed by “three reputable citizens of Rittman,” named Ewing, Goldner, and Fielding. Interestingly, there are some discrepancies between what we know of the wreck and what was said of that ghostly manifestation.

Were the Wreck and the Manifestations in Different Places?I suppose discrepancies in the historical record shouldn’t be a surprise. For instance, one paper says the first encounter with the phantom locomotive was on a Saturday while another says Thursday. Rushed reporters still get things wrong to this day. With this in mind, I’ll rely on an article that includes Dr. Faber’s own words, knowing full well he might’ve been misquoted. When the physician and his office boy first encountered the manifestation, they “were driving along the river road.” Faber and friend heard a train approaching. “There appeared to us to be nothing unusual about the train,” he continues,

until it came nearly opposite us. The engine whistled 'down brakes,' streams of sparks shot out of the wheels, and we distinctly heard the 'chuck, chuck' of the reversed engine. Just as the engine reached the bridge there was a flash and a terrific crash and the engine plunged into the stream.The doctor hurried his horse to the site — but “by the time we had reached the bridge there was not a sign of a wreck to be seen.” Faber confirms that, earlier that year, “an engine jumped the track at the point where I saw the phantom train,” presumably meaning the No. 5.

Now, the bridge where Faber had his encounter — and where he claims the wreck had occurred earlier that year — spans a river called Styx. Yes, that name carries a mythological association with death. However, the photograph below suggests the train didn’t actually plunge into this curiously named stream. Granted, it’s possible the river is not too far behind the camera or hidden just beyond the pile-up, but the train appears to have slipped off the embankment and into a something no more watery than a channel to drain rain water. Indeed, those March articles that reached both coasts say the No. 5 went “into the ditch,” not off a bridge and into a river.

A photo of the wreck was published in

American Locomotive Engineers: Eire Railway Edition

(1899), which included an obituary for Logan.

A photo of the wreck was published in

American Locomotive Engineers: Eire Railway Edition

(1899), which included an obituary for Logan.In other words, a half-year after the accident, its spectral reenactment had moved from what appears to be a farm to the Styx, from field to stream. Was Faber consciously or subconsciously “borrowing” images from that much deadlier, much more traumatic wreck that had happened a couple of decades earlier up in Ashtabula or from some similar wreck? Did having the No. 5 plunge into the Styx simply make for a more gripping tale?

Whatever explains the discrepancy between the early reports/photograph and Faber’s encounter, a subsequent sighting of the phantom train occurred near the bridge. In the article about Ewing, Goldner, and Fielding, the Akron Daily Democrat says the wreck had happened “on a trestle over the River Styx near Rittman.” These men’s experience with the phantom train was very similar to Faber’s: they were in the vicinity of the bridge, they heard a train approaching and then crashing, and they “ran down over the embankment to the edge of the stream into which the train had plunged.” However, once there, the trio found that “not a ripple disturbed the placid surface of the water.”

Perhaps they were looking in the wrong place on the tracks. The train wrecked due to engine trouble, remember — not bridge trouble.

From the 1899 Railroad Map of Ohio, available at the Columbus Metropolitan Library websiteLet’s Lengthen the Search

From the 1899 Railroad Map of Ohio, available at the Columbus Metropolitan Library websiteLet’s Lengthen the SearchMuch more recently, investigators have identified the bridge as the site of the wreck. For instance, John presents an engaging YouTube video about the history of the phantom train, shot and narrated at the bridge itself. Meanwhile, ghost hunter Ken Summers provides an excellent chronicle of his efforts to track down the correct bridge. I wonder, though, if those interested in the case should use the bridge as a handy landmark and wander along a longer path that safely accompanies the tracks.

A current map suggests that safe path might be along East Ohio Avenue or along Salt Street, since both run parallel to tracks crossing the Styx. However, this 1899 map shows the Erie Railroad — which the No. 5 was on — approaches Rittman from the northeast, coming from Wadsworth, while the B&O line approaches from the southeast, from Doyleston. Therefore, East Ohio Avenue is the better bet (as also suggested in this article). If you launch your own investigation, please let us know of the results in the comments section.

After the End of the Line: Railroad Hauntings in Literature and Lore .

February 12, 2024

A Book Report on David Welky’s A Wretched and Precarious Situation: In Search of the Last Arctic Frontier

“The lure of the Arctic is tugging at my heart.” — Matthew Henson

Crocker Land Haunts MeI keep returning to Crocker Land. It doesn’t exist — I know it doesn’t exist — but I can’t seem to leave it behind.

And I can’t explain what I find so fascinating about this and the many other cases of explorers spotting land in the Arctic, only to have the sighting proven false by those who followed. Robert Peary went public with his “discovery” of Crocker Land in 1907, but this certainly wasn’t the first time such a thing had happened. For instance, in 1818, Commander John Ross observed a mountain range extending across what was actually a passageway west, one that could have let him sail farther in pursuit of the Northwest Passage. Convinced he had seen land, he turned the ships under his command around and even named what he thought he had seen the Croker Mountains! I recently added Ross to my “Crocker Land and Other Mapped Mirages of the Arctic” page.

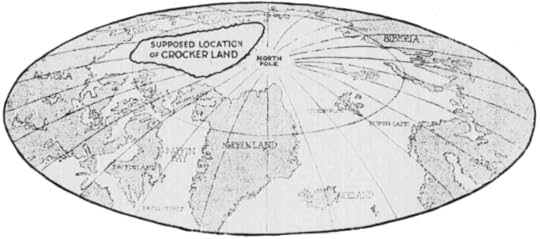

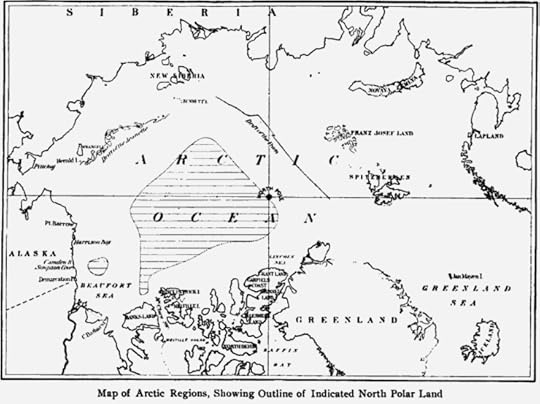

The September 24, 1916, issue of the Richmond Times-Dispatch includes this map of Crocker Land. It’s a very generous interpretation of “the faint white summits of a distant land” Peary claimed to have observed.

The September 24, 1916, issue of the Richmond Times-Dispatch includes this map of Crocker Land. It’s a very generous interpretation of “the faint white summits of a distant land” Peary claimed to have observed.This addition and my most recent return to Peary’s Crocker Land were sparked by reading David Welky’s A Wretched and Precarious Situation: In Search of the Last Arctic Frontier. It’s a remarkable book that is both engagingly written and impressively researched. Its main focus is a 1913-1917 expedition, led by Donald MacMillan and intended to verify the existence of Crocker Land (along with several other goals). This voyage became a solid first step in invalidating what Peary thought he had seen. I cite a couple of interviews with Welky in my pages on Croker Land, but I only recently read the book he discusses in them.

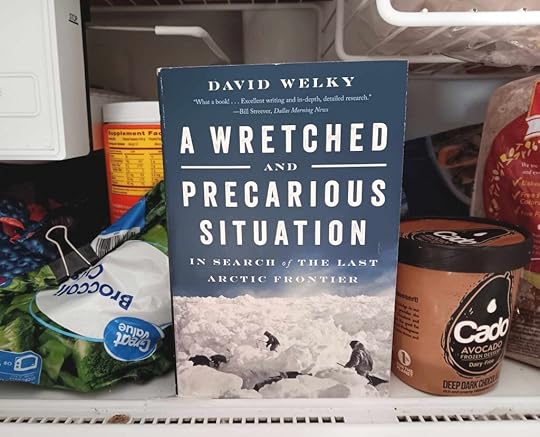

Somehow seemed like a good spot for my copy of Welky’s chilling yet tasty book.

Somehow seemed like a good spot for my copy of Welky’s chilling yet tasty book.While narrating MacMillan’s problem-plagued, four-year journey, Welky poses a serious challenge to Peary’s sincerity regarding his claim about having seen land off the coast of northern Canada. The historian writes:

Only Peary could say for sure, but numerous pieces of evidence indicate that he misled the world in order to advance his personal agenda. (255)This evidence includes Peary’s expertise in all things Arctic, including the mirages that might be seen there. There’s also a conspicuous absence of references to Crocker Land in the following:

Peary’s diary entries on the two days he supposedly spotted it;a record he left behind at the area where he supposedly spotted it;his photographs of the trip;the diary of one of his shipmates on the trip home;his newspaper interviews, letters, and speeches/lectures once he arrived back to the States;and the drafts of his chronicle of the expedition prior to the one for publication (pp. 255-259).That’s a suspicious amount of not mentioning what would have been a very important discovery! Add to this Peary’s record of making false claims, which I discuss below. Welky has good reason to go on to use unqualified language, referring to the Crocker Land claim as “Peary’s fraud” and “a lie” (pp 261, 422). Indeed, he builds a strong case for exactly that.

A Precedent for Doubting Peary’s HonestyWelky wasn’t the first to cast aspersions on Peary’s veracity, however. In 1916, Congressman Henry T. Helgesen gave a speech to the House, arguing that government-issued maps based on the explorer’s unreliable claims be corrected. The politician never exactly accuses Peary of intentional fabrication — but he comes very close. At one point, he says, “For 20 years, Mr. Peary posed as the discoverer of the Peary Channel, the discoverer of the East Greenland Sea, and the discover of the insularity of Greenland.” Subsequent exploration, continues Helgesen, established that the channel doesn’t exist and the sea is dry land while Greenland’s insularity had already been established by previous exploration (pp. 5-8). He moves on to other claims made by Peary, saying that one of them required the explorer “to occupy two widely separated points at one and the same time.” Noting that MacMillan couldn’t find Crocker Land where Peary had indicated, Helgesen dubs it “an imaginary dream” (pp. 5-11). He adds some “fictitious soundings reported by Peary” before including Peary’s life-defining claim of being the very first to have reached the North Pole among his “false claims of discovery and achievement” (pp. 20, 24). What begins as a plea to correct maps ends as an effort to ensure “that scientific proof shall prevail and that history shall not be perverted” (p. 31). The speech is a relentless attack on Peary’s character, and — as one might after reading Welky’s book — one is likely to walk away with a very poor opinion of the famous Arctic adventurer.

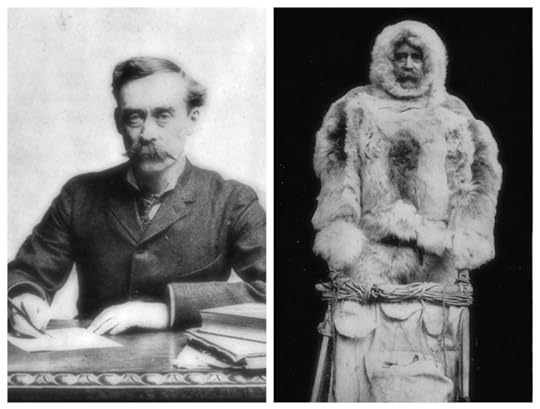

Robert Edwin Peary Sr. (1856-1920)Welky’s Troubling Use of “Continent”

Robert Edwin Peary Sr. (1856-1920)Welky’s Troubling Use of “Continent”That said, there was one element of A Wretched and Precarious Situation that made me wonder if Welky might be misrepresenting Peary in order to further his challenge to that man’s integrity. As far as I know, Peary’s only descriptions of what he thought he saw were “the faint white summits of a distant land” when he first saw it and “the snow-clad summits of the distant land in the northwest” the second time, both of these observations chronicled in Nearest the Pole: A Narrative of the Polar Expedition of the Peary Arctic Club in the S. S. Roosevelt, 1905-1906 (pp. 202, 207). Early on, Welky says: “Whatever Peary had twice seen, whether island or continent, would henceforth and forever be known as Crocker Land” (p. 11). Thereafter, the historian persistently refers to Crocker Land — not as an island — but as a continent. (See pp. 15, 30, 48, 69, 78, 82, 121, 169, 189, 190, 241, 249, 256, 257, 258, 261, 262, 304, 321, 343, 357, 412, 419, 422, and 434. Yep, it struck me as curious enough to mark the pages where the word appears as a description of Crocker Land.)

I’ve found unconfirmed land in the Arctic referred to as a continent in newspaper articles — sensationalized ones, such as the wild one in a 1922 issue of the Washington Times — but I don’t think that was ever Peary’s term or implication.

Now, whether a mirage or a lie, Crocker Land was bolstered by a 1904 essay by Dr. Rollin A. Harris, who advanced a theory regarding, as his title suggests, “Some Indications of Land in the Vicinity of the North Pole.” (Welky relates Peary’s claim to Harris’s theory on p. 261.) Harris refers to this hypothetical place as “a large tract of land dividing the deep Arctic channel” (p. 257), but he doesn’t use the word continent.

In fact, a map Harris provides suggests his “Indicated North Polar Land” to be roughly the size of Greenland, which is an island that’s part of the North American continent. Granted, there’s some debate in exactly how to define continent, but size matters. Greenland is about a quarter the size of Australia, the smallest member of the Continent Club. While Crocker Land might have been a very significant island — maybe an archipelago — Welky’s labeling it a continent is curious. Is this intended to suggest that Peary’s claim about Crocker Land was, not just any old lie, but a full-out whopper?

A Great Book for Us Armchair ExplorersDespite this semantic quibble, I highly recommend Welky’s book, especially to readers who, like myself, are fascinated by what’s revealed about human nature through Arctic exploration. The tenacity of MacMillan, the fraying nerves of his lead crew — which, in one case, led to murder! — and the drive to sail, paddle, tromp, and sledge across one of the planet’s most desolate, deadly regions acts as a good reminder that human beings are both bold and bonkers.

If you’re interested in what I discuss above, from the history of mapping Arctic mirages to my hesitancy in dubbing Peary a liar — at least, in regard to his having spotted unexplored land — my “Charting Crocker Land” project starts at Base Camp.

— Tim

Read more reviews in my“A Book Report on…” series.

February 5, 2024

Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit: A Phantom Locomotive Near Whitland, Wales

A Phantom Train That Arrived Early

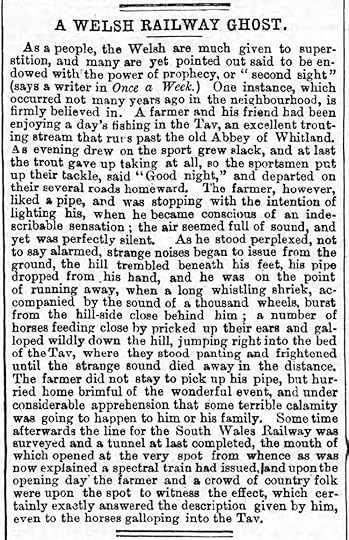

A Phantom Train That Arrived EarlyAn article titled “Beyond Gower’s Land” appeared in the November 12, 1864, issue of the magazine Once a Week. It’s I.D. Fenton’s chronicle of a journey through Wales, and along the way, the traveler transcribes an anecdote heard in the South West region. Within context, this anecdote has the feel of folklore, a charming and quirky tale the locals tell. Whether or not the locals honestly believe it is another matter.

This colorful anecdote tells of a phantom locomotive, one keeping with the tradition of spectral manifestations warning of future events. Curiously, the ghost train arrived to signal the coming of trains themselves. The tale was weird enough to be excerpted and reprinted in newspapers across the UK, where it then took on at least a hint of being a trustworthy news report.

From the November 19, 1864, issue of The Aberystwith Observer, page 3.

From the November 19, 1864, issue of The Aberystwith Observer, page 3.Presumably no record was made of the farmer’s prophetic experience — that “second-sighted” sign of trains one day tearing through the peaceful spot — before the railway was actually completed. One might wonder, then, if this tale is born of a nostalgic longing for the good old days. The unspoken moral of the story seems to be: I told you letting the railway come here was a bad idea! Didn’t I tell you?

But what if there is something more to it than that? Intriguingly, Fenton’s transcription provides enough clues to locate the real-life setting of the narrative. Some newspaper searching also gives us a pretty good timeframe for when that first corporeal train roared through the tunnel.

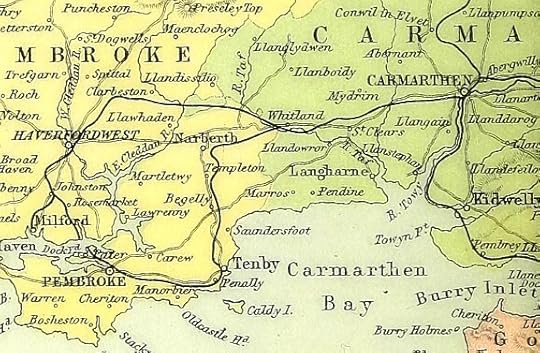

The Location of the TunnelFenton provides three landmarks that help us zero in on the location of the alleged encounter with a phantom train. First, there’s the River Tav (which I’ve also seen spelled “Tave,” “Taf” and “Taff.” The Welsh is “Afon Taf”). Apparently, this is not a safe place for trout, but it is for horses. Second, Fenton mentions Whitland Abbey, which is very helpful. The ruins of this structure lie northwest of the village of Whitland. Third, there’s the South Wales Railway tunnel, which is the most precise landmark in relation to the spectral/prophetic manifestation.

A bit of sloppy triangulation and a modern map reveal the tunnel is still there! (Look for the gap in the tracks in the southeast corner of that map.) Fenton is very helpful when it comes to pinning down where the prophetic experience allegedly occurred.

This drawing of a tile excavated from the ruins of Whitland Abbey appeared in the December, 1839, issue of Gentleman’s Magazine. Sadly, I was unable to find an illustration of the ruins themselves, but there might not have been much left to illustrate. Indeed, an 1847 travel guide says that “little else than a shadow now remains of that peaceful abode.” Yet some traces of the abbey still do remain, as these recent photos show.A Timeframe for the Anecdote

This drawing of a tile excavated from the ruins of Whitland Abbey appeared in the December, 1839, issue of Gentleman’s Magazine. Sadly, I was unable to find an illustration of the ruins themselves, but there might not have been much left to illustrate. Indeed, an 1847 travel guide says that “little else than a shadow now remains of that peaceful abode.” Yet some traces of the abbey still do remain, as these recent photos show.A Timeframe for the AnecdoteDetermining when it occurred is trickier. Fenton only says “not many years ago,” which is hard to subtract from 1864. It’s better than “once upon a time,” I guess, but there’s still enough haze to add to the story’s feel of folklore. Ah ha! — perhaps Fenton had predicted the story would fall under the eye of a research addict 160 years later! I went searching to find out when that first physical train ran through the tunnel.

Thanks to the online newspaper archive of the Wales National Library, I found that the South Wales Railway noted by Fenton extended its line from Carmarthen west to Haverfordwest — running through the tunnel and stopping at Whitland — as 1853 came to a close. According to a reporter in that year’s December 30 issue of the Pembrokeshire Herald, the new route had opened some days earlier. Though “of momentous importance,” the event had its opposition:

That there should be persons who are sceptical as to the advantages which it is expected we shall derive from Railway communication is not to be wondered at, when we consider that there is a tendency in some minds to a morbid apprehension of any change of circumstances, habits, and modes of existence with which long custom has rendered them familiar. ... It is felt that to invade the lonely dells where simplicity, peace, and contentment dwelt in undisturbed repose ... with the hideous shriek of the iron King, as he whirls onwards with fearful rapidity to his destination, may indeed serve to increase our wealth, and enhance our commercial importance, but can never compensate for the calm tranquillity which it displaces.Here, then, we see the perspective of that apprehensive farmer and of those spooked horses.

In this detail of “The Counties of South Wales” map from

Philips’ Handy Atlas of the Counties of England

(1873), the dark lines show the railway route from Carmarthen to Whitland and on to Haverfordwest. The River Taf is also indicated.

In this detail of “The Counties of South Wales” map from

Philips’ Handy Atlas of the Counties of England

(1873), the dark lines show the railway route from Carmarthen to Whitland and on to Haverfordwest. The River Taf is also indicated.The reporter goes on to describe what westbound passengers will encounter. Most relevant to us is the passage about leaving “St. Clears, where the first Station is built, and after passing through a tunnel near Penycoed, it crosses the Tave by a timber bridge on Piles to the Whitland Station.” When locating the tunnel, the reporter appears to have mistaken a wood named Pen-y-coed with the Great Pale Wood, the two being about three or four miles apart. Still, it’s neat that the tunnel is mentioned at all, and a similar article printed in The Welshman on the same day refers to it, too.

Given these articles, we now know that the day foretold by the spectral locomotive arrived toward the very end of 1853. This is about a decade before Fenton’s record of the strange manifestation was published. We also know that the clamorous event was not welcomed by everyone. In other words, the anecdote might be a folktale — but there’s a fair amount of truth woven into it.

Would a Prophecy Leave Behind Traces?Your typical haunting comes afterward. Let me explain. Say there’s a terrible train accident. Ghosts of those killed are observed afterward. However, in some cases, the ghost appears before a tragic event, such as with the canwyll corff (or corpse candles) once well-known in parts of Wales. In After the End of the Line, an entire section titled “Danger Signals from Beyond” presents railroad-related narratives about ghostly warnings of things-to-come. This is what happened beside that South Wales Railway tunnel sometime before 1853.

Given this, is the area on either end of the tunnel worth investigating over a century-and-a-half after the fact? Could any residual energy be measured or paranormal activity intuited? Well, WalesOnline says yes, putting it as #25 on a list titled “Mysterious Wales: 34 weird and wonderful secret places to go in search of the supernatural.” Trains appear to still run through the site, though, so I advise extreme caution. Remember that the phantom locomotive appeared outside the tunnel. If you happen to go there for some ghost hunting — and/or some trout fishing — please let us know about your outing in the comments, regardless of the results.

Discover more “Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit” at the page forAfter the End of the Line: Railroad Hauntings in Literature and Lore .

February 1, 2024

A Novice’s Introduction to Victorian Carriages, Part 4

GO TO VICTORIAN CARRIAGES, PART 2

GO TO VICTORIAN CARRIAGES, PART 3Variations on a VehicleThe forms of carriages as now built are so numerous as to almost defy classification, and they altogether baffle detailed description.

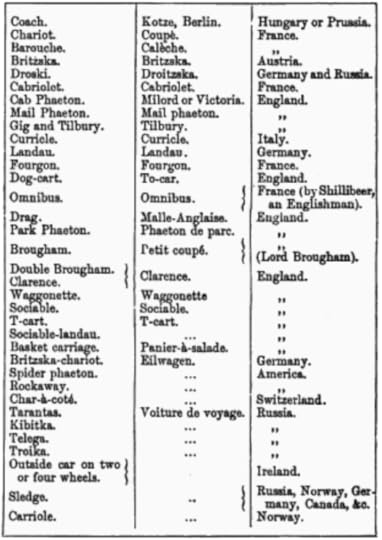

This passage comes from the entry for “Carriage,” sub-section “Modern Carriages,” in the 1876 edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, and — as if to prove the point — it’s followed by this chart of carriages and their countries of origin:

That article goes on to say that the list excludes “numberless forms of fancy carriage” resulting from “the misdirected ingenuity of coach-builders,” who combine bits and pieces of various vehicles yet fail to build a better mousetrap. My efforts to focus only a handful of Victorian carriages in these posts led me to the same conclusion: it’s really hard to nail down any reliable characteristics that differentiates, say, a dog-cart from a gig, a hansom from a cabriolet, or a sociable-landau from, well, a reclusive one.

Nonetheless, I still want to glance at two more vehicles that pop up in Victorian literature. After all, this series of posts was inspired by my urge to better envision what would have been easily envisioned by Victorian readers. Unlike the carriages I’ve discussed so far, which were built to comfortably accommodate two or four passengers, the wagonette and the omnibus could handle a group of passengers, perhaps eight or more.

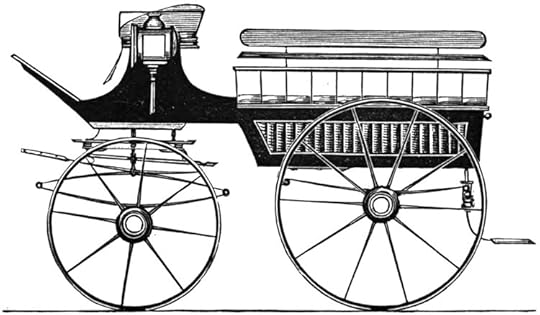

Piling into a Wag(g)onette This wagonette illustration appears in William N. Fitz-Gerald’s

The Carriage Trimmers’ Manual and Guide Book

(1881). There’s a fun photo of none other than Queen Victoria looking more amused than regal in the back of one here.

This wagonette illustration appears in William N. Fitz-Gerald’s

The Carriage Trimmers’ Manual and Guide Book

(1881). There’s a fun photo of none other than Queen Victoria looking more amused than regal in the back of one here.Disagreeing with the Britannica’s suggestion that cobbling together features from various carriages is “misdirected,” George S. Sidney says the wagonette “is a combination of all the best parts of the Irish inside car, the French sportsman’s char à banc, the English brake, and the modern stanhope phaeton.” He concludes that it “is, in fact, the perfection of a family country carriage.” Presumably, this is because several passengers can ride in it — some of them traveling sideways, but not backwards, on benches along both sides of the main passenger area — and yet it can be pulled by only one or two horses.

Given the passenger capacity of a wagonette, it makes sense that one carries the unwary Otis family to haunted Canterville Chase in Oscar Wilde’s “The Canterville Ghost” (1887). These carriages also roll into view in L.T. Meade and Robert Eustace’s A Master of Mysteries (1897-99), which is fitting since this introduction to Victorian carriages was nudged by my editing the first Curated Crime Collection volumes, and Meade and Eustace’s The Brotherhood of the Seven Kings (1898) and The Sorceress of the Strand (1902-03) are part of that. Yet another waggonette figures into H.G. Wells’s The Food of the Gods (1904).

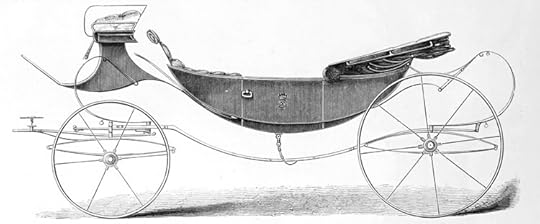

Squeezing into an Omnibus (a.k.a. a ‘Bus) From Henry Charles Moore’s

Omnibuses and Cabs: Their Origin and History

(1902)Of all the public conveyances that have been constructed since the days of the Ark — we think that is the earliest on record — to the present time, commend us to an omnibus.

From Henry Charles Moore’s

Omnibuses and Cabs: Their Origin and History

(1902)Of all the public conveyances that have been constructed since the days of the Ark — we think that is the earliest on record — to the present time, commend us to an omnibus.This according to Charles Dickens. His buddy Wilkie Collins seems to have liked omnibuses, too, since he has the title character of his novel Basil (1852) praise the “perambulatory exhibition-room of the eccentricities of human nature” afforded by them. Fortuné du Boisgobey opens Le Crime de l’omnibus (1881, an English translation being titled “An Omnibus Mystery”) with an interesting scene involving the frustrations of missing the last omnibus of the night, and from there, he transports readers to a murder case.

It strikes me that an omnibus might be the easiest of the Victorian carriages for 21st-century readers to visualize. Despite the transition from horse (and, in some cases, steam) power to fossil fuel — despite over a century of modification — buses look roughly the same. Well, very roughly. At least, we understand the basic principle: a driver in front with plenty of seating behind. Come to think of it, wagonettes are pretty easy to grasp, too. They’re basically wagons with a couple of bleacher seats.

Regardless, I’m now better at picturing these and the other carriages I’ve discussed, and I find myself excitedly trying to identify them in movies and TV shows set in Victorian times. I certainly hope I’ve helped others who enjoy Victorian fiction or period drama, too. As I’ve said at the end of the previous three posts, feel very free to correct or add to the discussion in the comments.

— Tim

GO TO VICTORIAN CARRIAGES, PART 1GO TO VICTORIAN CARRIAGES, PART 2

GO TO VICTORIAN CARRIAGES, PART 3

January 29, 2024

A Novice’s Introduction to Victorian Carriages, Part 3

GO TO VICTORIAN CARRIAGES, PART 2More Showy Phaetons

In Part 2, I looked at the brougham and the victoria, two prestigious carriages (though simpler, more affordable versions of them were available). Apparently, it was a thing among those who could afford it to parade around Hyde Park, displaying their frou-frou carriages. In Hyde Park, Its History and Romance (1908), Ethel Brilliana Tweedie (a.k.a. Mrs. Alec-Tweedie) tells us the title spot is where “the èlite drive on summer afternoons from five to seven, when four or five rows of motors and carriages moving along at a crawling pace is quite a common sight.” It was something of a ritzy ritual.

That sparkling parade probably included barouches and landaus, both discussed below. The former was mostly used in summer while the latter could be ridden throughout the year. But carriage makers were continually tinkering with and improving upon designs, borrowing a feature from one kind to put on another. There was even something called a barouche landau. In this regard, classifications of carriages are like genres of fiction: it’s best to remember that they’re ever-evolving and neither rule-bound nor stable.

Check the Weather Before Boarding a Barouche This illustration of a barouche appears in

The Art Journal Illustrated Catalogue

(1862). You can see a photo of one with the cover raised here. In fact, that covered barouche belonged to Abraham Lincoln, and it’s what he rode in to Ford’s Theatre on the night he was assassinated!

This illustration of a barouche appears in

The Art Journal Illustrated Catalogue

(1862). You can see a photo of one with the cover raised here. In fact, that covered barouche belonged to Abraham Lincoln, and it’s what he rode in to Ford’s Theatre on the night he was assassinated!As far as I can tell, a barouche was pretty much a victoria — but with seating for four instead of only two. The third and/or fourth passenger would ride facing backward right behind the driver, a seating plan often called “vis-à-vis.” However, if it started to rain, those suckers riding backwards would be all wet because a collapsible leather hood only reached far enough to protect the passengers facing forward. Think of this cover as something like what’s found on a baby carriage (or a perambulator, if infant perambulation is more your style).

I’m cheating on Victorian-era here, but I found it interesting that, in Sense and Sensibility (1910), one way Jane Austen shows how Edward Ferrars disappoints his sister involves a barouche. Or, rather, doesn’t involve a barouche. Well, I’ll let Austen explain:

[Edward] was neither fitted by abilities nor disposition to answer the wishes of his mother and sister, who longed to see him distinguished — as — they hardly knew what. They wanted him to make a fine figure in the world in some manner or other. His mother wished to interest him in political concerns, to get him into parliament, or to see him connected with some of the great men of the day. Mrs. John Dashwood wished it likewise; but in the mean while, till one of these superior blessings could be attained, it would have quieted her ambition to see him driving a barouche. But Edward had no turn for great men or barouches.Alas, poor Edward is too introverted for such a flamboyant vehicle. A more useful, more practical landau might’ve appealed to him — but Austen doesn’t address the matter. (She does, however, address a barouche-landau in Emma!)

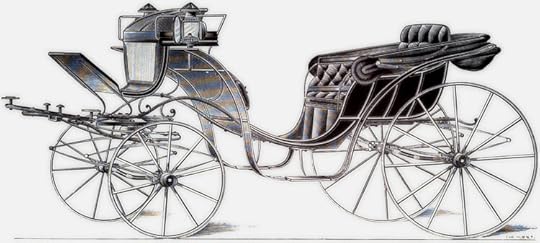

Only the Poor Coachman Gets Wet in a Landau This illustration from

The Hub

shows a landau with both leather hoods down. There’s a photo of one with the hoods up at the Encyclopedia Britannica.

This illustration from

The Hub

shows a landau with both leather hoods down. There’s a photo of one with the hoods up at the Encyclopedia Britannica.In Modern Carriages (1905), Sir Walter Gibley explains: “The advantages of the landau make it one of the most widely used carriages among private owners and on the public stands.” One of those advantages was the ability to raise two leather hoods — one in front and one in back — over the passenger compartment, making it as cozy as a clam. Unlike a clam, though, a landau with the hoods raised looked — to my novice eyes — something like a brougham because of the boxy shape of the passenger compartment. In fact, we might consider this a brougham convertible, and this begins to explain what made them so popular.

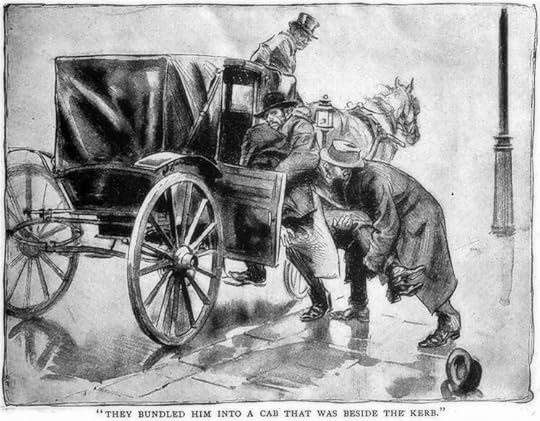

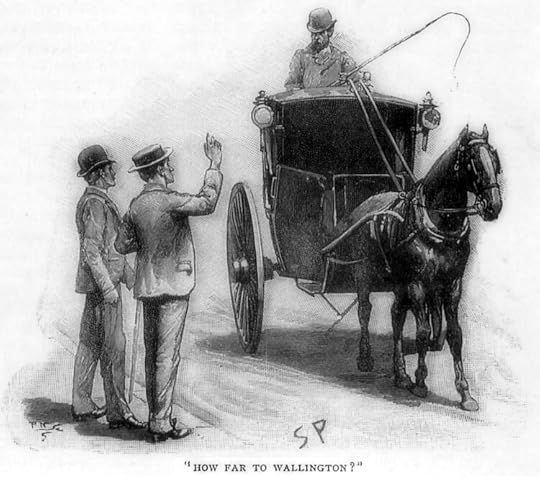

Wait! I wasn’t expecting a pop quiz! Well, I guess that’s the point of a pop quiz — but while researching and studying Victorian carriages, I stumbled upon a test of what I’ve learned so far. It involves a Sherlock Holmes story titled “The Adventure of the Red Circle” (1911 – again, not Victorian). In it, a character named Mrs. Warren explains her dilemma to Holmes, saying her husband had “not got ten paces down the road when two men came up behind him, threw a coat over his head, and bundled him into a cab that was beside the kerb.” Readers can assume that things happened too quickly for either Mrs. Warren or her abducted husband to have noticed the specific kind of carriage or cab involved. Arthur Conan Doyle doesn’t pin it down, either. This presents a challenge to an illustrator assigned to depict that dramatic moment, and H. M. Brock and Joseph Simpson are both named as illustrators in The Strand’s publication of the story. The result is this:

The abduction of Mr. Warren from Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Adventure of the Red Circle” as illustrated in

The Strand Magazine

The abduction of Mr. Warren from Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Adventure of the Red Circle” as illustrated in

The Strand Magazine

Now, Watson, let’s review the evidence. Sir Walter informs us that landaus were very popular. One might conjecture, however, that they were not quite so popular as to be immediately recognizable as, say, a hansom cab. Now, please note the leathery exterior and boxy shape of the passenger compartment in the illustration. Four wheels. One horse. I’m convinced, dear doctor, that what we see above is a landau! Yes, a laudau with the hoods raised to conceal nefarious shenanigans!

Then again, I ain’t no Sherlock Holmes. Feel very free to correct or expand on anything I say above in the comments below. I’ll wrap things up in Part 4, expanding on what I say in my opening comments above: not only did Victorian carriages wander all over the place in terms of locale — they also wandered all over the place in terms of design.

— Tim

GO TO VICTORIAN CARRIAGES, PART 1GO TO VICTORIAN CARRIAGES, PART 2

January 25, 2024

A Novice’s Introduction to Victorian Carriages, Part 2

In Part 1, I looked at two very popular carriages: the dog-cart and the hansom cab. Both of those typical have only two-wheels, though we saw that, sometimes, a four-wheel vehicle was called a “dog-cart.” Now, we look at two more carriages, both four-wheelers.

Apparently, “phaeton” was simply a name for almost any four-wheeled carriage, and there was quite a variety of phaetons. Here, I look at the brougham and the victoria.

Being Seen in a Brougham Another of the lovely illustrations from Samuel Sidney’s

The Book of the Horse

Another of the lovely illustrations from Samuel Sidney’s

The Book of the Horse

“Dorian, you will come with me. I am so sorry, Basil, but there is only room for two in the brougham. You must follow us in a hansom.” So says Lord Henry in Oscar Wilde’s A Picture of Dorian Grey (1890), and this helps us better see the picture being painted by Victorian authors who specify a brougham. It’s limited to two passengers. In fact, expert on all things equestrian Samuel Sidney explains that the later models “barely afford a place for the travelling-bag of more than one passenger.” Cozy, then. And the lighter load meant it could be drawn by only one horse, which I sense was a frequent sight, but there might be two.

It’s also what was called a “close carriage,” meaning riders were protected from the weather by an enclosure. One might wonder if it got stuffy in there! Well, Sidney tells us this vehicle was warm in winter and cool in summer. But they might’ve been “stuffy” in the sense that broughams were typically owned by the upper-crust, Lord Henry and the like. Sidney continues: “In the Park [presumably, London’s Hyde Park], and at other assemblies of the fashionable, the windows of a brougham are so ‘hung on the line’ as to present a fair face at the very best point of view for admiration and for conversation.” In other words, these were something of a high-fashion accessory for those wanting to be noticed. And this is why a 1901 short story titled “Wanted: for Desertion” opens with a police officer at a posh public performance using “his massive body as a buffer between brougham-windows and plebian curiosity.” Dare I say, one’s desire to be noticed hardly extends to being noticed by the riffraff.

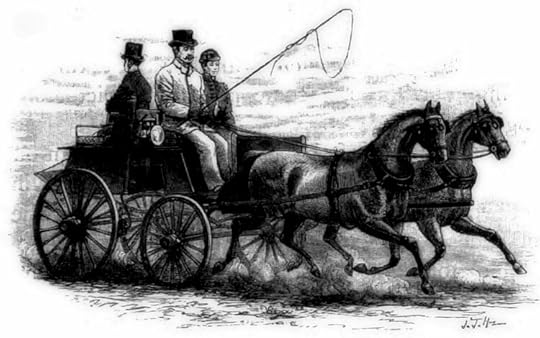

Being Even More Seen in a Victoria From an impressive series of 1886 “fashion plates” published in a New York magazine called The Hub

From an impressive series of 1886 “fashion plates” published in a New York magazine called The HubAs with the brougham, a victoria was light enough for only one horse, though more could be added. This, too, is vehicle for displaying one’s wealth. As Sidney points out, the victoria was designed to show off — not just one’s face — but one’s entire regalia, “from the crown of her head to the sole of her foot.” It is “an expensive carriage to convey two persons — a carriage only available for ornamental purposes, for it cannot be used at night, or in dirty weather, or in the country, or anywhere except for the Park, for a little shopping and a little visiting.” The illustration above says as much. That flip-up roof, often called a “calash,” might guard against the Sun — but not much more.

In Part 1, I make a quick mention of Bram Stocker’s Dracula (1897). In this novel of many narrative perspectives, one relevant moment comes through Mina’s eyes. She and Jonathan are strolling near Hyde Park, when something scary happens:

I was looking at a very beautiful girl, in a big cart-wheel hat, sitting in a victoria outside Guiliano’s, when I felt Jonathan clutch my arm so tight that he hurt me, and he said under his breath: "My God!"Yet Jonathan isn’t reacting to the passenger in the victoria (in front of Carlo Giuliano’s jewelry shop). Instead, he has spotted “a tall, thin man, with a beaky nose and black moustache and pointed beard, who was also observing the pretty girl.” The man has “big white teeth” that are “pointed like an animal’s.” As does Jonathan, readers are pretty sure they recognize this toothy chap from earlier in the novel. Now, let’s chart things here: upon observing the woman in the victoria, Mina next observes Jonathan observing Dracula observing the woman in the victoria. No wonder Stoker specifies that particular kind of carriage. The victoria wasn’t merely a mode of transportation. It was a mode of public appearance. It fits the scene perfectly.

I wonder, though, if broughams and victorias were more status-symbolic in metropolitan areas, especially London, than in the country. In Driving (1889), Henry Charles Beaufort contends: “A brougham, a victoria, or a waggonette, may be put down as the cheapest form of carriage procurable for general purposes.” He then qualifies this, though, by suggesting that those wanting something fancier can find such vehicles (and the horses pulling them) at “fancy prices.”

There were other kinds of phaetons that pop up in Victorian fiction, too, and I’ll discuss two more in Part 3. If you have anything to add — or to contest — please do so in the comments.

— Tim

GO TO VICTORIAN CARRIAGES, PART 1

January 22, 2024

A Novice’s Introduction to Victorian Carriages, Part 1

I started reading the Sherlock Holmes stories when I was a kid. Growing up near Chicago in the late 1900s, I squinted at — and shrugged off — references to the variety of Victorian horse-drawn vehicles named there. It might’ve been the brougham in A Study in Scarlet (1887), the landau in “A Scandal in Bohemia” (1891), or the dog-cart in “The Speckled Band” (1892). An adult now, I find myself more intrigued by such references, especially as I edit the volumes of the Curated Crime Collection. Grant Allen makes several in An African Millionaire (1897), but they’re sprinkled throughout the works of many Victorian writers. Would the original readers of Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), for instance, have found something significant when Jonathan Harker reacts strongly to seeing someone seated in, not just any old carriage, but specifically in a victoria? Why does a character in Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret (1862) character specify the vehicle when thinking: Nobody ever saw a ghost in a Hansom cab. And why did my favorite frustrated ghost hunter, James John Hissey, narrow down the manner of conveyance when titling his A Tour in a Phaeton Through the Eastern Counties (1889)?

Here in the States (and elsewhere, I’m sure), an author can quickly convey information about a character by saying they drive a BMW, a Dodge Ram, a Prius, etc. Once upon a time, there was a running gag about shmucks who own Edsels — and a very different connotation of what happens in VW vans. Were Victorian authors using a comparable shorthand? Seeking an answer, I’ve begun to research those Victorian carriages. Here are my early findings — and I welcome corrections and/or additional insights because I’m no expert at vehicular history.

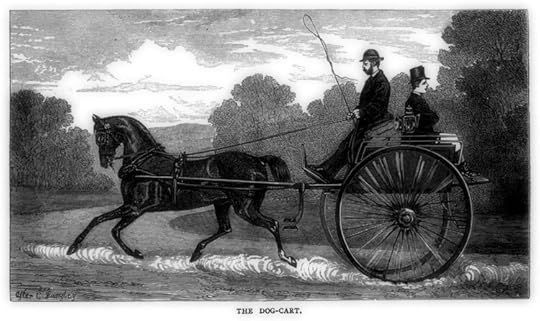

Embarking in a Dog-Cart J.J. Hissey also named his vehicle in

Across England in a Dog-Cart

(1891). This is his own illustration, and it’s titled — you guessed it — “The Dog-Cart.” As discussed below, however, some might beg to differ regarding that nomenclature.

J.J. Hissey also named his vehicle in

Across England in a Dog-Cart

(1891). This is his own illustration, and it’s titled — you guessed it — “The Dog-Cart.” As discussed below, however, some might beg to differ regarding that nomenclature.According to The Young Folks’ Cyclopedia of Common Things (1880), a because it was once much used by sportsmen, who carried their dogs to the hunting field in the box behind.” This carriage is pulled by one horse or by putting another horse before the horse before the cart (a.k.a. “tandem”), and you’ll notice in the illustration above that the far horse appears to be trotting outside of the shafts. Presumably, it will relieve the closer one that’s doing the actual pulling for now.

However, that illustration might be misleading due to the number of wheels. On the one hand, that Cyclopedia of Common Things points out that there are four wheels on a French dog-cart. On the other, a writer in an 1886 issue of The Hub contends: “The Dog-cart of today is a two-wheeled vehicle. … The so-called ‘Four-wheel Dog-cart’ is properly called a Phaeton.” Perhaps the distinction mattered more to carriage manufacturers in the U.S., who made up the target audience of The Hub, than to British authors. However, the illustration below from Samuel Sidney’s The Book of the Horse (1893) — a great source of illustrations! — suggests we can safely envision two wheels when such authors denote a dog-cart.

As implied above, I sense there was some flexibility in what exactly is meant by some of these vehicles’ names.

All Hail the Hansom Cab A hansom cab is featured in this illustration for “The Adventure of the Cardboard Box.” It’s one of Sidney Paget’s many depictions of Sherlock Holmes, and here the great detective is sporting a boater hat!

A hansom cab is featured in this illustration for “The Adventure of the Cardboard Box.” It’s one of Sidney Paget’s many depictions of Sherlock Holmes, and here the great detective is sporting a boater hat!Don’t you dare quote me on this, but I sense that dog-carts were generally used in rural settings while city folks were more prone to hail a hansom cab. (The H in “hansom” was sometimes capitalized and sometimes not.) Another two-wheeler, this vehicle is described in an 1894 source as “admirably adapted for the crowded streets of great cities.” A key difference between this and a dog-cart is the placement of the operator: the hansom perched drivers high and behind. Related to this modification, the hansom was better suited for only two passengers while dog-carts could comfortably carry four — though some would have to face backward, possibly making a few riders sick as a dog.

Hansom cabs were clearly a popular cultural reference point, as seen in the titles of Robert Lewis Stevenson’s “The Adventure of the Hansom Cab” (1878) and Fergus Hume’s The Mystery of a Hansom Cab (1889). Given the rapid rise of automobiles, perhaps it’s not terribly surprising that a 1912 issue of Popular Mechanics announced that hansom cabs had become so obsolete that they were becoming museum pieces.

Remember to Tip Your BloggerThe dog-cart and the hansom cab seem to be the most popular of the two-wheelers. I’ll move on to the four-wheelers in upcoming posts. As I say above, feel free to offer tips in the comments section if I’ve made any flubs or if you have any additional insights.

— Tim

January 15, 2024

Do We No Longer Expect Ghosts to Manifest with a Purpose?

Back when I was working on Certain Nocturnal Disturbances: Ghost Hunting Before the Victorians, I came upon a 1771 investigation involving a house haunted for no clear reason. The manifestations seemed random and chaotic, even if it had been a poltergeist. My research into the case grew into a chapter titled “Purposeless Ghosts: Jervis, Bolton, and Luttrell at Hinton Ampner.” You see, pre-Victorian ghost reports typically portray spirits as returning to the physical realm with a specific goal, albeit sometimes vague enough that a ghost hunter/real-life occult detective is required to solve the mystery and resolve the unfinished business. Gradually, though, the tradition of the ghost-with-a-goal faded.

By the end of the 1800s, the likes of Eleanor Mildred Sidgwick and Andrew Lang were discussing how purposeless ghosts had eclipsed the earlier kind. I discuss that here and, with greater depth, in Certain Nocturnal Disturbances. Embarking on a brand new project, though, I’ve found a few early- and mid-Victorian mentions of this curious aspect of ghostlore.

Two Curt Nods to Purposeless Ghosts

Two Curt Nods to Purposeless GhostsFor instance, in an 1841 article, Robertson Noel surveys “a few of the strange and wild notions which prevailed among our forefathers, on the subject of spectral appearances.” In other words, he treats a belief in ghosts as something quaint and outdated, which was pretty common in the early 1800s. At one point, Noel relates what feels like a fairy tale about a spectral child repeatedly roaming through a house. Mustering courage to follow the spirit, a visitor helps to reveal that, in life, the child had selfishly hidden two pennies in the floor boards rather than obediently passing them along to a beggar. Once the living deliver the coins to the intended party, the guilty ghost of the naughty child is never seen again. Noel comments:

In the little story related above there was a reason assigned for the appearance; but in seven out of ten of extant ghost stories, there is so evident a want of cause that they must be classed as inventions, and not very cunningly devised.If a ghost is said to be without purpose, according to Noel, someone surely must be fibbing — and badly. Rather than give even one example of this, though, he immediately proceeds to a case of a murder victim’s ghost appearing to divulge where her body lies hidden and who her killers were, which strikes me as a very urgent reason to manifest indeed! I’m left to conclude that, while Noel recognized that most accounts of ghosts involve purposeless ones, he considered such tales a waste of ink.

By 1860, things seem to have been about the same: purposeless ghosts were glanced at but given the cold shoulder. That year, an anonymous writer arguing against the reality of ghosts makes the following observation:

Most ghost stories tell us that ghosts appear for some certain object; that there is some reason for their quitting the land of shadows to return to the place of their earthly residence; and that they have something of importance to communicate to the living. But there are numerous instances in which they are said to have appeared for no particular object, or, at all events, with no apparent reason.Rather than expand upon this point, though, the writer quickly moves on to the long history of believing in ghosts.

Handpicking Our Ghost StoriesAs I say, the late Victorians were better at grappling with purposeless ghosts. In fact, the two examples above seem to support Lang’s theory that “the old believers in the old-fashioned ghost chiefly collected and recorded the more striking and interesting cases — those in which the ghost showed a purpose (as a few modern ghosts still do).” Purposeless ghosts have been around all along, Lang suggests, but earlier ghostologists failed to preserve cases involving them, creating a false impression that ghosts had become aimless during the 1800s.

The tales we tell about ghosts — the ones we find worth repeating and those we shrug off — certainly change over time. And this has me wondering how things stand in the early 2000s. Do we interpret ghosts as having clear-cut purposes for either returning to or remaining in familiar places? Do they still manifest to ensure justice? To rectify mistakes? To plead for prayers or for some other kind of assistance from those left behind? Are they, in our psychology-savvy age, mostly about relentless trauma? Do we now classify purposeless ghosts as “residual hauntings“?

Beats me — I live in the past! With this in mind, I’ll continue to hunt historical ghosts, thank you.

— Tim