A Novice’s Introduction to Victorian Carriages, Part 1

I started reading the Sherlock Holmes stories when I was a kid. Growing up near Chicago in the late 1900s, I squinted at — and shrugged off — references to the variety of Victorian horse-drawn vehicles named there. It might’ve been the brougham in A Study in Scarlet (1887), the landau in “A Scandal in Bohemia” (1891), or the dog-cart in “The Speckled Band” (1892). An adult now, I find myself more intrigued by such references, especially as I edit the volumes of the Curated Crime Collection. Grant Allen makes several in An African Millionaire (1897), but they’re sprinkled throughout the works of many Victorian writers. Would the original readers of Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), for instance, have found something significant when Jonathan Harker reacts strongly to seeing someone seated in, not just any old carriage, but specifically in a victoria? Why does a character in Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret (1862) character specify the vehicle when thinking: Nobody ever saw a ghost in a Hansom cab. And why did my favorite frustrated ghost hunter, James John Hissey, narrow down the manner of conveyance when titling his A Tour in a Phaeton Through the Eastern Counties (1889)?

Here in the States (and elsewhere, I’m sure), an author can quickly convey information about a character by saying they drive a BMW, a Dodge Ram, a Prius, etc. Once upon a time, there was a running gag about shmucks who own Edsels — and a very different connotation of what happens in VW vans. Were Victorian authors using a comparable shorthand? Seeking an answer, I’ve begun to research those Victorian carriages. Here are my early findings — and I welcome corrections and/or additional insights because I’m no expert at vehicular history.

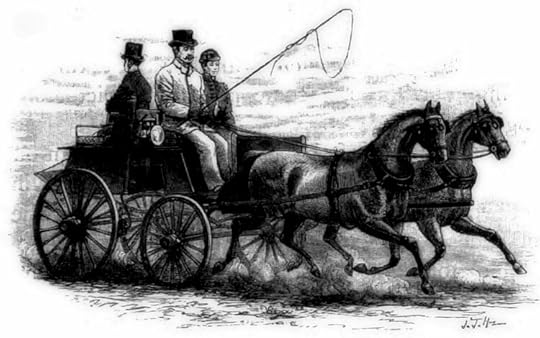

Embarking in a Dog-Cart J.J. Hissey also named his vehicle in

Across England in a Dog-Cart

(1891). This is his own illustration, and it’s titled — you guessed it — “The Dog-Cart.” As discussed below, however, some might beg to differ regarding that nomenclature.

J.J. Hissey also named his vehicle in

Across England in a Dog-Cart

(1891). This is his own illustration, and it’s titled — you guessed it — “The Dog-Cart.” As discussed below, however, some might beg to differ regarding that nomenclature.According to The Young Folks’ Cyclopedia of Common Things (1880), a because it was once much used by sportsmen, who carried their dogs to the hunting field in the box behind.” This carriage is pulled by one horse or by putting another horse before the horse before the cart (a.k.a. “tandem”), and you’ll notice in the illustration above that the far horse appears to be trotting outside of the shafts. Presumably, it will relieve the closer one that’s doing the actual pulling for now.

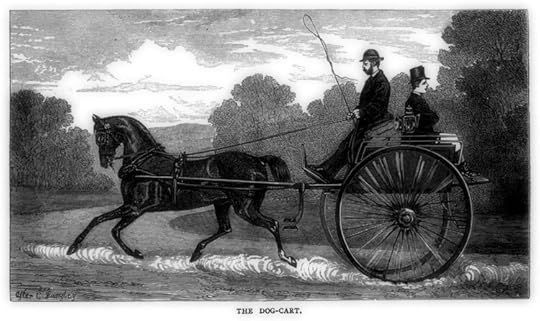

However, that illustration might be misleading due to the number of wheels. On the one hand, that Cyclopedia of Common Things points out that there are four wheels on a French dog-cart. On the other, a writer in an 1886 issue of The Hub contends: “The Dog-cart of today is a two-wheeled vehicle. … The so-called ‘Four-wheel Dog-cart’ is properly called a Phaeton.” Perhaps the distinction mattered more to carriage manufacturers in the U.S., who made up the target audience of The Hub, than to British authors. However, the illustration below from Samuel Sidney’s The Book of the Horse (1893) — a great source of illustrations! — suggests we can safely envision two wheels when such authors denote a dog-cart.

As implied above, I sense there was some flexibility in what exactly is meant by some of these vehicles’ names.

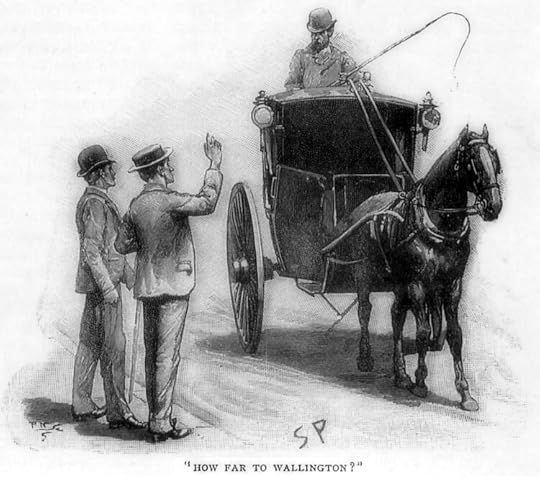

All Hail the Hansom Cab A hansom cab is featured in this illustration for “The Adventure of the Cardboard Box.” It’s one of Sidney Paget’s many depictions of Sherlock Holmes, and here the great detective is sporting a boater hat!

A hansom cab is featured in this illustration for “The Adventure of the Cardboard Box.” It’s one of Sidney Paget’s many depictions of Sherlock Holmes, and here the great detective is sporting a boater hat!Don’t you dare quote me on this, but I sense that dog-carts were generally used in rural settings while city folks were more prone to hail a hansom cab. (The H in “hansom” was sometimes capitalized and sometimes not.) Another two-wheeler, this vehicle is described in an 1894 source as “admirably adapted for the crowded streets of great cities.” A key difference between this and a dog-cart is the placement of the operator: the hansom perched drivers high and behind. Related to this modification, the hansom was better suited for only two passengers while dog-carts could comfortably carry four — though some would have to face backward, possibly making a few riders sick as a dog.

Hansom cabs were clearly a popular cultural reference point, as seen in the titles of Robert Lewis Stevenson’s “The Adventure of the Hansom Cab” (1878) and Fergus Hume’s The Mystery of a Hansom Cab (1889). Given the rapid rise of automobiles, perhaps it’s not terribly surprising that a 1912 issue of Popular Mechanics announced that hansom cabs had become so obsolete that they were becoming museum pieces.

Remember to Tip Your BloggerThe dog-cart and the hansom cab seem to be the most popular of the two-wheelers. I’ll move on to the four-wheelers in upcoming posts. As I say above, feel free to offer tips in the comments section if I’ve made any flubs or if you have any additional insights.

— Tim