Tim Prasil's Blog, page 8

January 8, 2024

The Hurtful Finale of Ada M. Jocelyn’s Otherwise Interesting Occult Detective Novel

Lady Mary’s Experiences (1897) is a novel by Ada Marie Jocelyn (née Jenyns, a.k.a. Mrs. Robert Jocelyn). A reviewer for The Literary World describes the work’s protagonist, Lady Mary “Molly” Merton, as someone who — after two spectral encounters — “asked for fresh ghosts, and the idea of going to live in a haunted house captivated her.” Upon finding one, Lady Mary “made up her mind to take it, furnish it, live in it, and compel it, so to speak, to exhibit for her pleasure whatsoever phantoms held it on a supernatural lease.” Given this, I figured I might have a work of Victorian occult detection, one made unusual by being of novel-length and by casting a woman in the role of lead ghost hunter.

To be sure, the first 35 chapters were all I had hoped they would be. Jocelyn uses those first two spectral encounters to cleverly illustrate how Lady Mary has evolved into someone eager to investigate haunted places and intent on freeing ghosts from their earthly shackles. The first experience is very basic: Lady Mary learns that she can see a ghost thought to be perceptible only to members of the Englefield family. In fact, she sees that the ghostly “woman in green” can also appear in white and black gowns. Does Lady Mary have a special gift for apprehending apparitions? Well, recounting the adventure, she says that it was learned “that I was distantly related to the Englefields on my mother’s side of the family.” So maybe there’s no special gift.

But then she narrates her second experience, and Lady Mary discovers herself to be what might have been called a “sensitive” or a “ghost-seer” in her own age — and what might be called today a “clairsentient,” an “empath” or, specifically, a “mediumship empath.” This case also calls on her to perform nocturnal surveillance, a spectral stake-out, so she’s on her way to becoming an occult detective.

The third haunting, then, makes up most of the novel, and Jocelyn depicts Lady Mary balancing nocturnal surveillance with witness interviews and rational deduction. The character passes the Occult Detective Qualification Exam as she attempts to unravel the riddle of a house called the Grey Hall. This stately structure is falling into ruin because tenants avoid it, and they avoid it mostly because of its reputation for being haunted or cursed or something else that’s very unappealing. “And I have made up my mind to solve the mystery here,” proclaims Lady Mary, “and lay the ghost also, if that is possible.”

The Grey Hall Mystery and a Unique Holmes and WatsonThe primary paranormal phenomena at Grey Hall is no one can sleep there. Not at all! Oh, there are unsubstantiated reports of weird sounds and shadowy figures, but that main manifestation — insistent insomnia — is something that I found distinctive and intriguing. Regarding it, Lady Mary promptly determines what none before her had: the sleeplessness only occurs upstairs. Swap the rooms traditionally on the first floor with the upstairs bedrooms, and an investigator can snoop as long as she likes without being driven away or driven mad by the relentless lack of sleep.

True to form, Lady Mary has a sidekick in this case, a skeptical Scully to her more open-minded Mulder. She’s Veronica Lawrence, and together, they form a duo that one character considers “as capable of taking care of themselves as any two women she had ever come across.” Indeed, Veronica explains that she learned to use a revolver “in a manner which I find reassuring, out in the backwoods of Canada.” At one point, she carries it in her dressing-gown. She also owns a dog named Reckless, “a great, ugly brute” that few can control. Simply put, Veronica is the brawn to Lady Mary’s brain.

This is not Veronica Lawrence, but I have a strong hunch this woman from an 1895 issue of Ludgate Magazine also carries a pistol in the folds of her dressing gown.

This is not Veronica Lawrence, but I have a strong hunch this woman from an 1895 issue of Ludgate Magazine also carries a pistol in the folds of her dressing gown.We learn early on that the property owner, Lord Artingdale, knows something about the haunting — a nasty family secret — that he’s keeping to himself. This is complicated by the romantic history between Artingdale and Lady Mary. He loved her. And, though she liked him pretty much, she was married. They parted. He pined. She had a kid. He pined. She became a widow. He pined. They meet again when Lady Mary happens upon the Grey Hall. It’s a ghost novel, not a ghost short story, so I guess some romantic entanglement is to be expected.

Does the Romantic Entanglement Explain the Hurtful Finale?And then Lord Artingdale’s younger brother, Jim Ackroyd, falls for Lady Mary. And vice versa. It’s a mess with a fairly predictable clean-up. But Jocelyn handles it well, and single-parent Lady Mary — even with her youth, beauty, and wealth — is something other than the marriageable miss one meets in, say, a Jane Austen novel. That said, if one is reading Lady Mary’s Experiences to enjoy a typical occult detective narrative, one might grow a bit annoyed by the heavy romance element. But that’s not what ultimately hurts the novel.

The novel’s greatest weakness, I think, is its conclusion. For 35 chapters, the author has been presenting Lady Mary and Veronica as smart, brave, and tenacious. There’s a great scene toward the end involving Jim and Lady Mary urgently wanting to get upstairs while Reckless prevents them from using the front stairs. She suggests they fetch a ladder to climb in through a portico window. Jim suggests that, instead both of them going, Lady Mary retreat to someplace safe. “I am coming with you,” says she, “so do not waste any time in arguments.” He accepts this. On the way to the ladder, lovestruck Jim insists Lady Mary promise to marry him. She consents, adding, “Only please do not let us lose any time.” They soon arrive at the ladder, and Lady Mary grabs one end. Jim tries to halt this, too. Jocelyn writes:

In spite of his protests, she secured the lighter end of the ladder, and as she seemed determined to retain it, as usual he was obliged to give in and let her do so.In barely more than two pages, Jocelyn has forecast a marriage in which Lady Mary continually throws cold water on Jim’s desire to make himself a conventional man-in-charge and his wife into a conventional damsel-in-distress. It feels very modern.

But just a couple of chapters later, our occult detective with the ability to see ghosts witnesses the terrible spirit that presumably keeps people awake. Jocelyn writes:

Jim Ackroyd saw nothing, but that something appalling must have been seen by Lady Molly, he had no doubt, and a moment later he received her unconscious form in his arms.No woman has come anywhere close to fainting at any point until this. The fact that Lady Mary does at the pivotal moment contradicts all that came before it. Ouch.

(Sketchy spoilers ahead.)

In addition, the full details of the family secret are finally revealed by Lord Artingdale to Jim, who then shares them with Lady Mary, thereby diminishing her role as the central riddle solver. Ouch. And nothing about the mystery’s solution has anything to do with keeping people awake. Ouch.

That all said, just before Lady Mary collapses in her future husband’s arms, she has done pretty well at being a successful occult detective. Her actions have helped expose a murder in the house. She speculates that this will allow the victim, at least, to move on. The murderer’s ghost, she adds, will probably linger on at the Grey Hall as punishment, and the narrator’s closing comments suggest this is correct. In the end, our otherwise promising occult detective falls short of banishing the evil spirit. Ouch.

Still, Lady Mary has come close enough to solving the case to qualify for my Chronological Bibliography of Early Occult Detectives. And Jocelyn’s dramatizing her character’s growth toward that classification makes Lady Mary’s Experiences especially interesting reading.

Go to the Chronological Bibliography

Go to the Chronological Bibliographyof Early Occult Detectives — 1800s page.

December 31, 2023

The Crime Wave Has Risen: TWO More Volumes of the Curated Crime Collection Are Available!

The Curated Crime Collection features reprints of — and interesting combinations of — fictional works that put a criminal character at center stage (though the spotlight there might be kept a bit dim). I call the first phase of releases “The Crime Wave Rises,” and it includes three books. If everything goes to plan, the next two phases, respectively called “The Crime Wave Crests” and “The Crime Wave Crashes,” will each introduce three books, too, for a total of nine.

All of the material being reprinted was originally published in the late 1800s and early 1900s. You see, in these decades, mystery fiction exploded, thanks largely to the stunning popularity of Sherlock Holmes. Many authors wanted a slice of the crime pie, and while criminal lead characters were certainly overshadowed by detective characters, I managed to compile a lengthy list of the former. It took me over a year to do so, and I’m now slowly reading and choosing the best of the best. I’m carefully curating the crime.

Criminal characters have a very long history, though. Think, for instance, of the Robin Hood legends of the Middle Ages. Still, Grant Allen’s “The Curate of Churnside” (1884) and An African Millionaire (1897) seem to have been at the forefront of a new type of criminal character. Especially his short story explores the complexities of morality, the battle of good and evil waged within us all. Think, for instance, of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886). Allen, then, seemed like a good author to feature in the first volume of the collection.

Elizabeth Phipps Train’s A Social Highwayman (1895) works very nicely beside Guy Boothby’s A Prince of Swindlers (1897). That’s why these works are combined in the second volume. Train being an American and Boothby being an Australian (by birth) shows that the wave was wide. Also, Train’s Courtice Jaffrey and Boothby’s Simon Carne not only prey on the well-to-do — they are the well-to-do! No, E.W. Hornung did not invent the gentleman thief by introducing A.J. Raffles in 1898. He was merely taking a developing literary trend to a new level of success.

Like the two before it, the third volume is a “partners in crime” book because it combines two criminal characters. Both The Brotherhood of the Seven Kings and The Sorceress of the Strand were written by collaborators L.T. Meade and Robert Eustace, and each features a woman master criminal. In a sense, they were ushering Trincomalee Liz — the barely seen woman who finances Boothby’s Simon Carne — from the shadows of Sri Lanka to the limelight of London. I can’t say this with 100% certainty, but I believe this is the first time Meade and Eustace’s Madame Koluchy and Madame Sara have appeared in the same book. If that’s correct, it’s also unusual. After all, they are very prominent members of literature’s sinister sisterhood.

As I shift to curating the next three works, I’ll probably blog more about these first three. Meanwhile, you can download my introduction to this neglected trend in mystery fiction from the page detailing all three of the books.

–Tim

December 17, 2023

A Curated Curate and a Crafty Con Man: The First Volume of the Curated Crime Collection is Available

I forget which version of Grant Allen’s “The Curate of Churnside” I read first. Was it the one from either of his collections, Strange Stories (1884) or Twelve Tales: With a Headpiece, a Tailpiece, and an Intermezzo (1899)? Or was it the version with the very different finale that was printed in Cornhill Magazine in 1884? All I know is that, most likely, Allen preferred the version found in his collections and, most likely, the different ending in the magazine resulted from an editor worried about offending readers. “The Curate of Churnside,” you see, is a very daring tale.

However, that Cornhill editor couldn’t get around the story’s plot involving a curate (which is an assistant minister) murdering his uncle by stabbing him in the back, quite literally and with thorough premeditation. But what should happen to that murderous clergyman in the end? If I’m right, the editor wanted justice to be served, be it by the legal system, by a guilt-ridden conscience, or by fate. The author, though, wanted his tale to be far more unconventional or unsettling.

The respected curate Walter Dene tenderly mends a dog’s paw — a sad accident that occurred while the clergyman was murdering his uncle! This illustration from Grant Allen’s “The Curate of Churnside” appeared in its Cornhill Magazine publication.

The respected curate Walter Dene tenderly mends a dog’s paw — a sad accident that occurred while the clergyman was murdering his uncle! This illustration from Grant Allen’s “The Curate of Churnside” appeared in its Cornhill Magazine publication.Upon discovering these two versions, I knew I had a very interesting insight into how the late Victorians were questioning the moral foundations of their cosmos. Centuries of storytelling suggest that, in one way or another, crime will be punished. My research in ghostlore has taught me that, when it doesn’t at first, the dead can return to request rectification. My interest in Edgar Allan Poe’s tales has shown me that — even when detectives are unhelpful or God seems unconcerned — guilt or fate or even insanity will ensure a murderer gets revealed. Think especially of “A Tell-Tale Heart” or “The Black Cat.”

But Allen’s version of “The Curate of Churnside” challenges that preconception. And that was pretty bold. And that’s why, after presenting his version of the tale, I include what I call “The Cornhill Ending” in The Curate of Churnside & An African Millionaire, the first of the Curated Crime Collection.

This is followed by An African Millionaire (1897). While this novel isn’t quite as unsettling as the short story, it is a lot of fun. The premise involves an ingenious con man who relentlessly targets and frustrates a South African diamond tycoon, and this allows Allen to make some pointed social commentary, too. 1897 saw the release of a few important novels using farfetched fantasy to comment on colonization. Bram Stoker’s Dracula might be considered more an invasion narrative, but — as Lucy Westenra might tell you — Dracula’s distinctive method of “converting” the English natives to his way of doing things makes him a very weird kind of colonizer. Maybe H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds, which debuted the same year, is clearer example of how one alien’s invasion is another’s colonization.

And Allen questions the morality of the colonial presence in Africa by showing that the title victim is far from innocent. Not quite a vampire or a Martian perhaps, but someone readers don’t mind seeing swindled over and over. In fact, this is one of those heist stories that nudge one to root for the robber.

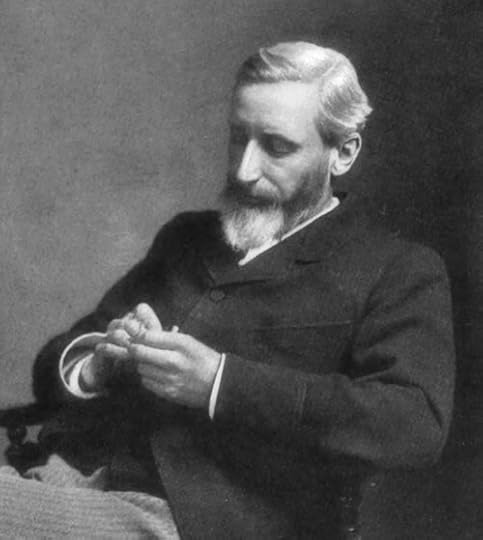

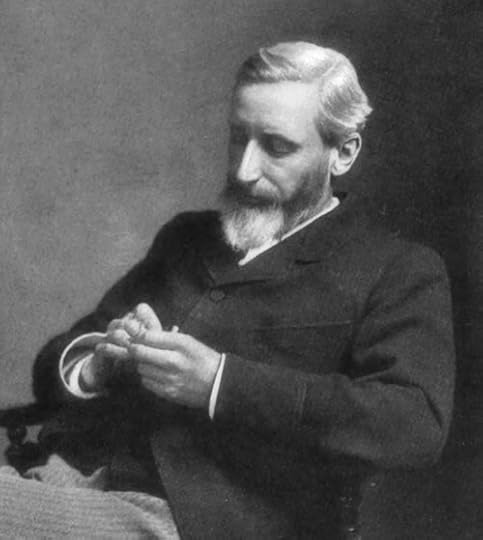

Grant Allen

Grant AllenPlease consider purchasing The Curate of Churnside & An African Millionaire, by Grant Allen. If all goes well, the first three (of a projected nine) volumes of the Curated Crime Collection will be out before the end of the year. Read more about them here — or find this first one at Amazon.

— Tim

December 10, 2023

Announcing the Curated Crime Collection

Very soon, the first three volumes of the Curated Crime Collection will be available for purchase. The series is something a bit new for Brom Bones Books. Here’s how I summarize it:

The Curated Crime Collection showcases works of fiction whose central characters are criminals, culled from a wave of such literature that rose in the late 1800s and subsided in the early 1900s.I wrote an introduction to the series and titled it “A Searchlight Can Serve as a Spotlight.” There, I discuss how critics from those decades acknowledged that criminals had figured prominently in prose fiction and a variety of other narrative forms for centuries. However, they also identified a new wave of such stories rising shortly after Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes had become an international sensation. It’s as if some writers wanted to take advantage of the burst of popularity in mystery fiction by inventing variations on Moriarty (or Adler or Milverton, etc.) rather than creating yet another spin on Holmes himself.

Grant Allen (1848-1899) had a key role in rejuvenating fiction focused on a criminal character. This portrait comes from the December, 1899, issue of The Bookman.

Grant Allen (1848-1899) had a key role in rejuvenating fiction focused on a criminal character. This portrait comes from the December, 1899, issue of The Bookman.But this renewed interest in criminal characters worried several of those critics. They warned that putting criminals at center stage — be they thieves or murderers — would corrupt impressionable youth. It’s same argument that, at various times, has been aimed novels altogether, comic books, TV shows, video games, and more.

Meanwhile, during the late 1800s/early 1900s, a new science dubbed “Criminology” developed amid debates over the causes of crime and the best methods to prevent and penalize it. Add to this daring ideas about whether morality is a fixed system created by God — as certain as cosmological physics — or a much more fluid notion created by humanity — as inconsistent as individual consciences.

As I discuss in “A Searchlight Can Serve as a Spotlight,” this swirl of trends, worries, and debates helps explain why criminals became a fascinating topic for fiction writers to explore as the nineteenth century evolved into the twentieth. My essay is available here and on the information page for the first phase of the series. It will also be in the first volume.

The first three books in the Curated Crime Collection should be available for purchase before the end of the year.

— Tim

December 3, 2023

Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit: A Pedestrian Crossing Near Sittingbourne Station, Kent

A Wide-Spread Report

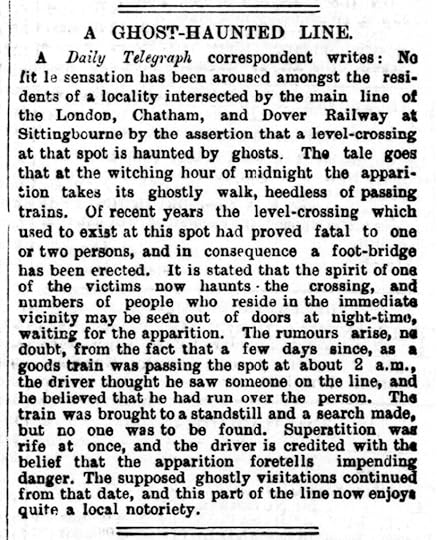

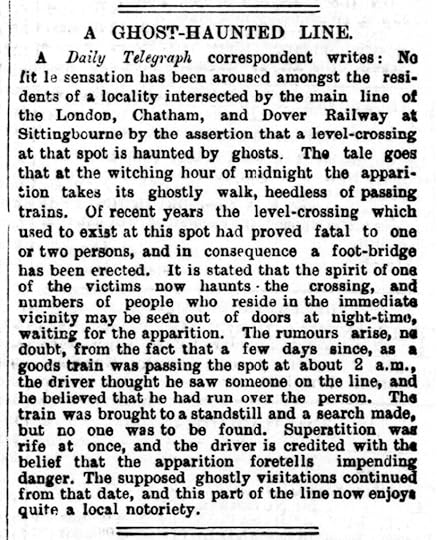

A Wide-Spread ReportIn late 1893, news of an apparition materializing near Sittingbourne Station in southeast England spread far and wide. The report appears to have originated in the Daily Telegraph, but it quickly spread to several other British newspapers, as far away as Australia, and even into journals aimed at those interested in the paranormal or in railroads.

From the November 4, 1893, (pg. 3) issue of the Brighouse & Rastrick Gazette

From the November 4, 1893, (pg. 3) issue of the Brighouse & Rastrick GazetteAs far as these railroad haunting articles go, this one seems a bit sketchy. The article suggests that there was only one witness, who encountered the specter only once. I’ve read enough of these reports to know there’s nothing at all unique about the driver thinking “he had run over [a] person . . . but no one was to be found” while also suspecting “the apparition foretells impending danger.” Those are both conventional elements of railroad ghostlore. So why did this case receive so much attention? Why did this skimpy evidence inspire residents to go out ghost hunting on those autumn nights?

Sittingbourne Station’s Deadly HistoryThe answer might be buried in the fact that the “spot had proved fatal to one or two persons” within those local ghost hunters’ memories. In fact, Sittingbourne Station had been a deadly site for decades. Here’s what I found:

1861: On January 5, the Sun reported that a “fatal accident occurred” the previous day as a train approached Sittingbourne Station. The train threw a wheel and derailed, a passenger named Patterson becoming mangled in the wreckage. His injuries were so severe that he died a few hours afterward. 1862: On October 22, the Albion reported a similar accident. A mail train “ran off the line, near Sittingbourne Station, and killed the engine-driver.”1878: The Glasgow Herald joined many British newspapers in reporting on an August 31 collision between two trains “on the London, Chatham, and Dover Railway, at Sittingbourne Station.” Two days after the tragedy, the journal explained that “five had been killed and about forty severely injured.”1881: A paper called Brief News & Opinion reported on James Williams, a man who “was killed by being knocked down at a very dangerous level-crossing on the London, Chatham, and Dover Railway.” Interestingly, the article notes: “On account of numerous fatalities which have occurred at these crossings at Sittingbourne great indignation has been aroused….”Given those “numerous fatalities” mentioned in 1881, I suspect there had been several other instances of horrible accidents around Sittingbourne Station by the time the 1893 ghost report gained so much attention. Reports of railroad-related fatalities were widespread during these decades, and this helps to explain why ghost reports involving grisly deaths probably struck a chord with a vast audience.

Finding the Haunted Site TodayWhile finding the station itself is easy, ghost hunters might have to visit a few possible locations to investigate what the 1893 ghost report describes as a level-crossing replaced by a foot-bridge. Luckily, the website of the ARCHI UK offers a very useful map of Milton-next-Sittingbourne along with an ingenious “Time Traveller Tool” that lets a user slide back and forth between a Victorian ordinance map and a modern one.

The bridge over the tracks that connects Jubilee Street to Hawthorn Road is a likely suspect for the haunted spot. However, I wouldn’t rule out what appear to be underpasses farther east: one connecting Redgrove Avenue to Laburnam Place, one at Milton Road, and one at Crown Quay Lane. The story about the haunting persists on various websites, such as the one for The Yorkshire Post and for The Paranormal Database. But does the ghost still walk? If you join those residents of 1893 in searching for answers, please let us know about your experience.

Discover more “Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit” at the page forAfter the End of the Line: Railroad Hauntings in Literature and Lore

A Pedestrian Crossing Near Sittingbourne Station, Kent

A Wide-Spread Report

A Wide-Spread ReportIn late 1893, news of an apparition materializing near Sittingbourne Station in southeast England spread far and wide. The report appears to have originated in the Daily Telegraph, but it quickly spread to several other British newspapers, as far away as Australia, and even into journals aimed at those interested in the paranormal or in railroads.

From the November 4, 1893, (pg. 3) issue of the Brighouse & Rastrick Gazette

From the November 4, 1893, (pg. 3) issue of the Brighouse & Rastrick GazetteAs far as these railroad haunting articles go, this one seems a bit sketchy. The article suggests that there was only one witness, who encountered the specter only once. I’ve read enough of these reports to know there’s nothing at all unique about the driver thinking “he had run over [a] person . . . but no one was to be found” while also suspecting “the apparition foretells impending danger.” Those are both conventional elements of railroad ghostlore. So why did this case receive so much attention? Why did this skimpy evidence inspire residents to go out ghost hunting on those autumn nights?

Sittingbourne Station’s Deadly HistoryThe answer might be buried in the fact that the “spot had proved fatal to one or two persons” within those local ghost hunters’ memories. In fact, Sittingbourne Station had been a deadly site for decades. Here’s what I found:

1861: On January 5, the Sun reported that a “fatal accident occurred” the previous day as a train approached Sittingbourne Station. The train threw a wheel and derailed, a passenger named Patterson becoming mangled in the wreckage. His injuries were so severe that he died a few hours afterward. 1862: On October 22, the Albion reported a similar accident. A mail train “ran off the line, near Sittingbourne Station, and killed the engine-driver.”1878: The Glasgow Herald joined many British newspapers in reporting on an August 31 collision between two trains “on the London, Chatham, and Dover Railway, at Sittingbourne Station.” Two days after the tragedy, the journal explained that “five had been killed and about forty severely injured.”1881: A paper called Brief News & Opinion reported on James Williams, a man who “was killed by being knocked down at a very dangerous level-crossing on the London, Chatham, and Dover Railway.” Interestingly, the article notes: “On account of numerous fatalities which have occurred at these crossings at Sittingbourne great indignation has been aroused….”Given those “numerous fatalities” mentioned in 1881, I suspect there had been several other instances of horrible accidents around Sittingbourne Station by the time the 1893 ghost report gained so much attention. Reports of railroad-related fatalities were widespread during these decades, and this helps to explain why ghost reports involving grisly deaths probably struck a chord with a vast audience.

Finding the Haunted Site TodayWhile finding the station itself is easy, ghost hunters might have to visit a few possible locations to investigate what the 1893 ghost report describes as a level-crossing replaced by a foot-bridge. Luckily, the website of the ARCHI UK offers a very useful map of Milton-next-Sittingbourne along with an ingenious “Time Traveller Tool” that lets a user slide back and forth between a Victorian ordinance map and a modern one.

The bridge over the tracks that connects Jubilee Street to Hawthorn Road is a likely suspect for the haunted spot. However, I wouldn’t rule out what appear to be underpasses farther east: one connecting Redgrove Avenue to Laburnam Place, one at Milton Road, and one at Crown Quay Lane. The story about the haunting persists on various websites, such as the one for The Yorkshire Post and for The Paranormal Database. But does the ghost still walk? If you join those residents of 1893 in searching for answers, please let us know about your experience.

Discover more “Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit” at the page forAfter the End of the Line: Railroad Hauntings in Literature and Lore

November 26, 2023

Ghost Stories by an Arctic Fireside in 1850 — and a Chased Cheese in 2023

If you’re a frequent visitor at BromBonesBooks.com, you might know about my fascination with “phantom islands” in the Arctic. This interest was sparked by Robert Peary’s 1907 claim of having glimpsed an uncharted piece of land during one of his (failed) attempts to reach the North Pole. He called the place Crocker Land, and years later — after Crocker Land had been proven to not exist — Peary was accused of fabricating the “sighting” to garner funding for his next expedition. This inspired me to explore the many previous cases of respected explorers who also had reported seeing islands that weren’t actually there. I don’t know if Peary was intentionally lying, but I do know he was far from alone in having made such a claim.

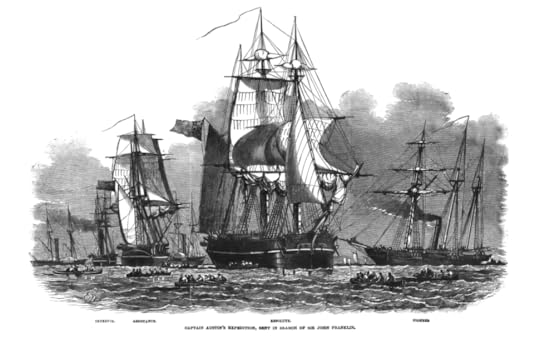

I’m also fascinated by the Arctic expeditions themselves. Imagine my pleasure, then, in discovering a book that presents various documents, many of them fairly casual, written during an 1850-1851 British voyage north. Though there were four ships with four captains, Admiral Horatio Thomas Austin appears to have been the man in charge. The collection is a mishmash of pieces written by officers and crewmen, titled Arctic Miscellanies: A Souvenir of the Late Polar Search (1852). Among the contents are articles written for a shipboard “newspaper” called the Aurora Borealis.

This illustration of the various ships involved in Austin’s expedition comes from the May 11, 1850, issue of the Illustrated London News.

This illustration of the various ships involved in Austin’s expedition comes from the May 11, 1850, issue of the Illustrated London News.And among these articles is one about how Christmas was spent onboard, frozen in place. (See pages 141-143.) Here, my fascination with Arctic exploration crossed paths with my interest in the old custom of telling ghost stories by a fire during nasty weather. Using the name “A Venerator of By-Gone Times,” the writer discusses time-honored Christmas customs, such as hearthside storytelling:

Everybody can recollect gathering round the fireside, with the great Yule-log blazing upon it, and listening with feeling of delight, not unmixed with awe, to some jolly, well-told story about ghosts or robbers, in which damp vaults, ruined castles, church-yards, and violent tempests are portrayed. . . .Indeed, the writer continues, such tales were shared during that Christmas far from home, where “the weather outside is twice as cold” and where there was “fifty times the quantity of ice and snow that there is in England.” I’ve added the full quotation to my Fireside Storytelling Descriptions & Depictions TARDIS page. Look for it under 1852.

Chasing a Research Question as If It Were Cheese“A Venerator of By-Gone Times” also describes the Christmas feast the explorers shared, listing foods from mutton to mince-pies — and, of course, plum-pudding. But one item named there confused me: “double Gloucester.” My first thought was it might be a kind of ale, one well suited to winter like a double bock. This shows how my mind works. While I have lived a decade in Wisconsin, America’s Dairyland, it was mostly in Milwaukee. Therefore, I start with beer.

I’m ashamed to say that, not only did I not know about double Gloucester cheese, I didn’t even know there was such a thing as a cheese stool! Clearly, my education should start with The Cow: A Guide to Dairy Management and Cattle-Rearing (1880). It has an excellent chapter on cheese.

I’m ashamed to say that, not only did I not know about double Gloucester cheese, I didn’t even know there was such a thing as a cheese stool! Clearly, my education should start with The Cow: A Guide to Dairy Management and Cattle-Rearing (1880). It has an excellent chapter on cheese.Instead, I discovered, double Gloucester is a cheese. (Confusing it with single Gloucester cheese would be a dreadful faux pas, one presumes.) Not only that, but each year, in Brockworth, Gloucestershire, England, people come from around the world to chase a wheel of double Gloucester cheese sent rolling down a hill. The hill is so steep that seemingly every contestant tumbles and somersaults to win that treat. Let’s take a look, shall we? (Note: this footage is not for the faint of heart.)

Here’s what I learned this week: 1) the tradition of telling ghost stories by a fire during inclement weather made it as far as the Arctic, and 2) people can be delightfully and dangerously silly — especially when there’s cheese at sake.

— Tim

November 5, 2023

Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit: The Curve Near Wicks, Missouri

Half a Ghost

Half a GhostThere is a curve in the tracks near Wickes, Missouri, that skirts a rock formation called Sentinel Rock. Starting around 1885, railroad workers passing by saw a ghost standing on top of this rock. Maybe standing isn’t quite right, since the apparition was that of a “half man,” the figure a person from the waist up, according to a lengthy article in the May 27, 1906, issue of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. That report also says that tales of the ghost had been circulating among railroaders for twenty years, and “today it is probably the most talked-about railroad ghost story in the world.”

The article identifies the ghost as Philip Toland, who had been killed in that location when his southbound train collided with one charging north. Toland “was crushed, his lower extremities being consumed in the firebox of the engine, into which he was forced by the shock of the impact.”

These injuries are consistent with news reports of the tragedy shortly after it happened, but the 1906 article mistakes the year slightly. The wreck didn’t occur in “the summer of 1884,” but in the spring of 1885, as revealed by Chicago’s Daily Inter Ocean and, closer to Toland’s home, The Philadelphia Times. Still, it’s interesting that the spirit reputed to haunt the spot is identified as someone who actually had died there two decades earlier.

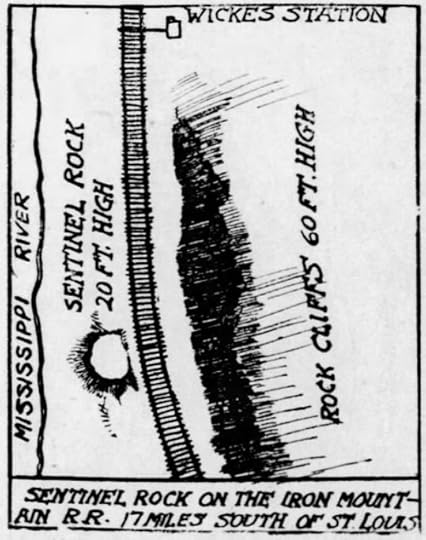

The tracks and limited visibility beside Sentinel Rock are shown in James Cox’s

Our Own Country

(National, 1894).Was Toland Warning of a Future Wreck?

The tracks and limited visibility beside Sentinel Rock are shown in James Cox’s

Our Own Country

(National, 1894).Was Toland Warning of a Future Wreck?Some of these railroad hauntings feature an apparition presumably trying to signal “DANGER AHEAD,” whether it’s ahead in terms of distance or of time. If that’s the case here, the ghost of Toland seems to have lingered very patiently to warn about another deadly train accident that occurred near Wickes in 1904. This was a derailment instead of a head-on collision. At least nine people were killed and many more were injured, according to an early report of this second wreck. The 1906 article about the ghost mentions this event, explaining that, two weeks prior to it, “the crew of a southbound freight train had seen the dimly outlined of the half man on top of the rock….”

Toland probably wasn’t hanging around to forewarn of that disaster, though, because his apparition continued to manifest on Sentinel Rock afterward. “Not long ago,” says the 1906 article, a man wanting to see the ghost accompanied an engine crew as they traversed the haunted spot.

The moon shone brightly from the full orb and one shriek of the whistle was the signal for Wickes Station. At the end of a sharp turn Sentinel Rock came into the vista. There was a wavering, uncertain movement on top of the rock [but the speed and smoke prevented clear observation. The men looked back after passing, and the man who stoked the engine's fire] said he was sure the ghost was there and that the bright moonlight had prevented a good view of the specter.Maybe that fireman was simply keeping the story alive. But maybe the ghost on Sentinel Rock was holding firm to his trackside lookout.

This map from the 1906 article might be a bit confusing, since the Mississippi River is to the east and southbound trains pass Sentinel Rock before reaching Wickes Station. Basically, it’s upside-down to how we typically read maps today.Visiting the Site Today

This map from the 1906 article might be a bit confusing, since the Mississippi River is to the east and southbound trains pass Sentinel Rock before reaching Wickes Station. Basically, it’s upside-down to how we typically read maps today.Visiting the Site TodayThe area around Wickes Station, called Wickes, is now a neighborhood in the city of Arnold. Probably the best way to visit the haunted site is via Wicks Road. Heading southeast, cross the tracks — yes, the tracks are still there! — and then take Dickerman Drive northeast toward the Arnold Ultra Light Airport. I can’t pinpoint where Sentinel Rock is, if it is still there at all, but clues in the 1906 article put it somewhere between Dickerman Drive and the tracks running parallel to the northwest. It strikes me that any interested ghost hunters must first apply their bloodhound skills to finding that rock formation before determining if Toland’s patient and persistent ghost remains to this day. If you give it a go, please share what you have or haven’t discovered in the comments below.

And if you’re planning to make a weekend trip of it, nearby Kimmswick offers a lot of history and a long list of old buildings. Surely, there’s got to be a ghost or two lurking there somewhere.

Discover more “Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit” at the page forAfter the End of the Line: Railroad Hauntings in Literature and Lore

November 1, 2023

Breaking News: Elizabeth Phipps Train’s Death Confirmed (in 1940)

This last weekend, I blogged about an American author named Elizabeth Phipps Train. She had gained acclaim in the late 1800s, but apparently started avoiding the limelight around the turn of the century. I was hoping to confirm her date of death, and this morning, I am able to do that. As suspected, it was indeed 1940.

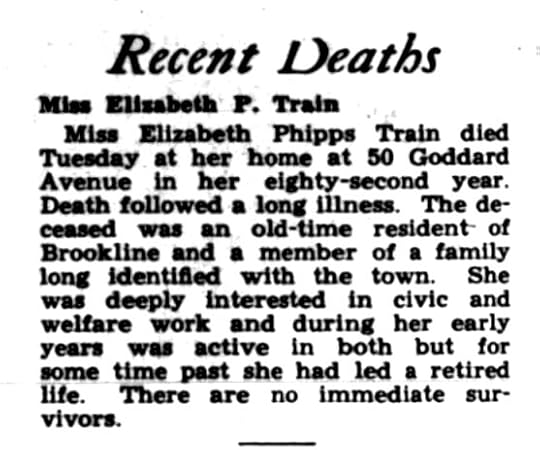

Here’s Train’s obituary, published in the July 18, 1940, issue of The Brookline Chronicle:

The address — 50 Goddard Avenue, Brookline — matches the 1940 census, which has Train living with her sister, Hannah P. Weld, née Train. So why that last line: “There are no immediate survivors”? In fact, Weld’s 1943 obituary mentions another living sister.

And why no mention in Train’s obituary of her having once been a noted author, one who had penned well-received novels and short stories? In my research, I came upon a celebrity sighting (yes, a “Train spotting”) notice published in 1926. She had been staying at the Ritz Carlton in Atlantic City, and the fact was considered newsworthy. This shows Train’s accomplishments as an author were still recognized as late as the mid-1920s. Had her shining star become extinguished just 14 years later?

I have no answers. But I do have abundant gratitude for Kelly Keener, whose expertise in and devotion to preserving the history of literary figures led to her locating this obituary and to her editing Tales, Sketches, & Poems of Charles Fenno Hoffman. My earlier post about Train is here.

— Tim

October 29, 2023

The Case of the Disappearing Author; Or, When Did Elizabeth Phipps Train Die?

In 1902, Elizabeth Phipps Train was described as an author whose name was “widely known,” at least in regard to the literary scene in Boston, Massachusetts. She had, after all, penned several novels, and she made the list of “Best American Authors” in a 1900 short story anthology that includes three of her tales.

Elizabeth Phipps Train, taken from the May, 1894, issue of Book News and colorized at Palette

Elizabeth Phipps Train, taken from the May, 1894, issue of Book News and colorized at PalettePerhaps celebrity did not agree with her, though. Train appears to have stopped writing not long after achieving these honors. Searching the usual online archives, I haven’t found any works by her or mentions thereof published after those short stories from 1900. She seems to have taken up traveling while also falling off the literary map.

I mention this because I’m embarking on a project that has prompted me to investigate her biography. On the one hand, there’s pretty good evidence that Train was born in 1856. On the other, the only evidence I’ve found of when she died comes from a genealogy site, which says 1940 — but without solid documentation in the form of, say, a death certificate or a newspaper obituary to confirm that year.

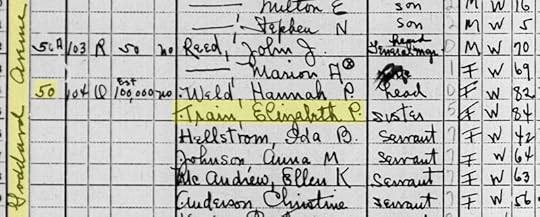

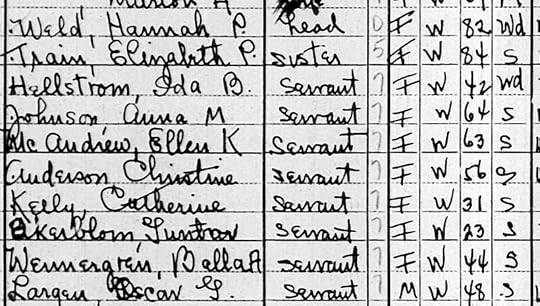

I have reason to believe that might be wrong, though. The U.S. census reveals that in April of 1940, Elizabeth P. Train was a single woman living in Brookline, a town near Boston, with her widowed sister, Hannah P[utnam] Weld (and a bewildering number of servants). That’s not the problem. Train could have died later in the year.

The problem is found in a Boston Globe article from 1943 with the headline “Hannah P. Weld, Brookline, Leaves Sister $100,000.” The piece says that Weld died in February of that year and then implies that “Elizabeth P. Train, Brookline, sister,” was still around to inherit that goodly sum. In other words, on the surface, it looks as if Train hadn’t died a few months after the census taker had visited in 1940.

Now, the Globe article does say, “The will was drawn in 1937.” It’s possible the reporter hadn’t checked to see if the woman named in the will and in the headline was still alive. It’s possible the reporter had never heard that the once-famous author had died a few years earlier. That’s some pretty shabby reporting, though, especially for such a respected journal. The really frustrating thing is that, despite Train’s earlier acclaim — despite her being related to a Boston Brahmin family — I can’t find even one obituary or tribute written about the author that would help settle the year she died. I’m hoping someone who reads this can help me solve this little mystery.

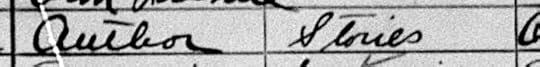

In the meantime, let me share something amusing that I found in my research. It’s from the 1910 census. Train was living in Boston and — sandwiched between the likes of a scrub women in the hotel business and a merchant engaged in dry goods sales — we find her specific occupation and general field:

She was an Author in the Stories industry.

— Tim