Tim Prasil's Blog, page 5

September 18, 2024

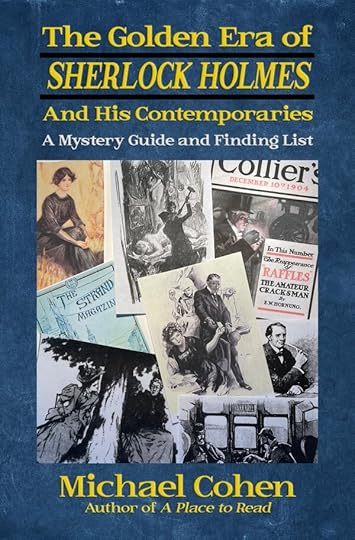

A Book Report on Michael Cohen’s The Golden Era of Sherlock Holmes and His Contemporaries

A criticism of modern detective fiction would obviously be inadequate without some appreciation of the great Sherlock Holmes cycle…. A man who had not heard of Holmes would be more singular than a man who could not sign his own name.

— Cecil Chesterton, “Art and the Detective” (1906)

You’re a Wizard, SherlockDo you remember the level of popularity that Harry Potter generated as the 20th century became the 21st? I imagine this is the closest equivalent we have to the Sherlock Holmes craze of a century earlier. I keep bumping into references to Holmes whether I’m looking at critics’ responses to that era’s criminal characters for the Curated Crime Collection or reading tales for the Chronological Bibliography of Early Occult Detectives. The Bodacious Brain of Baker Street even pops up in at least one survey of haunted sites. As Cecil Chesterton notes in the 1906 essay quoted above, Sherlock Holmes had become a part of everyday language in a way that very few other fictional characters can claim.

By 1904, Sherlock Holmes merchandising was underway, as shown by this ad in The Smart Set. Could lunch boxes and action figures be far behind?

By 1904, Sherlock Holmes merchandising was underway, as shown by this ad in The Smart Set. Could lunch boxes and action figures be far behind?Close upon the heels of Arthur Conan Doyle’s newfound fame, mystery fiction swelled with competitors, a swarm of scribes who brought a diversity of detectives often appearing in short-story series. In The Golden Era of Sherlock Holmes and His Contemporaries (Genius, 2024), Michael Cohen explains that his “concentration is on those features that led to Conan Doyle’s success and how those following him employed and transformed them.” Cohen proves himself to be very well-read in this wave of mystery fiction, introducing readers to a library full of potential new reading material in chapters devoted to imitations/sharp revisions of Holmes, to women detectives, and to medical and other scientific crime-solvers. I was especially happy to see a chapter devoted to the kind of criminals whose exploits I curate — and another to those investigators whose dealings with ghostly clients and demonic culprits qualify them for my bibliography.

The Pluses and Problems of ParametersCohen sets the parameters for his material pretty firmly between 1891, when the first Holmes short story debuted, and 1918, when World War I ended. To be sure, along with a lot of conventional detective fiction, these years also encompass a wide range of innovative, even experimental, work. As the author says:

The genre-extending and changing, the deconstruction, the repeated failures, the intertextuality, reflexivity, and metafiction characteristics of this First Golden Era of detective fiction are worth pointing out and naming.As we wander through the many authors and characters, Cohen adds dashes and splashes of connections to Holmes, references to Edgar Allan Poe, historical contextualization, and his personal preferences. I especially appreciated his explanation of how changing trends in publishing herded detective fiction away from novels and toward short-story series — and, afterward, back to novels.

However, a book of this type necessitates a great deal of plot summary (and Cohen divulges a good many endings, too). In this regard, I found the reading the book straight through a bit sluggish, but perhaps Golden Era is better understood as a reference work that can be read bit by bit, now and again, to discover new reading material. And Cohen provides a long list of online sources for the works he discusses in case readers have come upon a character or two who have sparked their interest. I was honored to see my Chronological Bibliography included there.

Nonetheless, the time frame might also help explain why Cohen falls back on a truncated history of occult detective fiction that scholars digging deeper have extended to many decades earlier. Cohen opens his chapter titled “Occult Detectives” by bluntly stating:

The occult or psychic detective in fiction is a late nineteenth century invention, though some have made an argument for Sheridan Le Fanu's Dr. Hesselius, a minor character in one of his books that collects earlier stories, In a Glass Darkly (1872).In keeping with some literary historians (two of whom I discuss in Part 3 of “Settling on a Definition of Occult Detective Fiction”), Cohen names John Bell, L.T. Meade and Robert Eustace’s debunking detective, and Flaxman Low, E. and H. Heron’s expert on genuine spooks, as the first characters to count as occult detectives. This version of the history excludes relevant fiction by important writers such as E.T.A. Hoffman, Fitz-James O’Brien, Edward Bulwer-Lytton, and Charlotte Riddell. As I say, perhaps this is prompted by Cohen’s historical parameters. Nonetheless, a quick acknowledgement of literary precedents — as he elsewhere makes with Poe, Mary Elizabeth Braddon, and Wilkie Collins — would have kept me from wincing.

Clear Prose (with a Few More Winces)Despite that quibble, which might be a very personal one, Cohen writes with a clarity that doesn’t sacrifice intelligence. He builds on the work of several literature scholars, but avoids the specialized jargon that sometimes accompanies discourse in that field. On the other hand, my wincing reflex was also triggered by obsolete terms such as “mulatto” (pg. 22), “negro” (pg. 55), or even “Scotchman” (pg. 64), none of which are clearly signaled as reflecting the language of the era under discussion. Readers forewarned of these moments are likely to find The Golden Era of Sherlock Holmes and His Contemporaries very enlightening.

— Tim

Read more reviews in my“A Book Report on…” series.

September 11, 2024

The Short Fiction of Catherine Crowe: “Loaded Dice”

Though a short story titled “Loaded Dice” was published anonymously in an 1850 issue of Household Words, two sources confirm that it was written by Catherine Crowe. One is the office book of the journal’s subeditor William Henry Wills, which is transcribed in Anne Lophrli’s index Household Words: A Weekly Journal 1850-1859 Conducted by Charles Dickens (U of Toronto Press, 1973. The entire index is available online in the U.S. at Hathitrust, and those elsewhere can see the story’s entry at Google Books.)

The other source is more illuminating. Charles Dickens, editor of Household Words, wrote to Wills regarding Crowe’s story a couple of months before it was printed. Apparently, the famous author wasn’t too keen on “Loaded Dice,” which begs the question of why he published it. He says:

Mrs. Crowe's story I have read. It is horribly dismal; but with an alteration in that part about the sister's madness (which must not on any account remain) I should not be afraid of it. I could alter it myself in ten minutes.It might be easy to agree with Dickens, since “Loaded Dice” is probably not one of Crowe’s better short works. One weakness might be seen in the story’s narrative frame. This tale repeats a pattern that Crowe uses in an earlier crime story, “An Adventure in Terni” (1841): two travelers, one acting as narrator, come upon something mysterious and — after conducting some subsequent, “offstage” inquiry — the narrator relates the backstory that accounts for the mysterious something. Crowe is following the basic format of a mystery story. But with Step 2 missing.

Step 1) Client walks into the detective’s office with a mystery,

Step 2) detective investigates, and

Step 3) the backstory is unveiled.

Of course, I’ve oversimplified things here, but I think you see my point. If Crowe had spent more time with that middle chunk, she might be better remembered as an important figure in the history of the mystery. At least, we would see why the visiting narrator plays an important part in the tale. On the surface, it seems like this story could’ve been told without the framing device.

Dying of ShameAnother weakness might be in the fact that, while “An Adventure in Terni” involves a murder, “Loaded Dice” is about a young man cheating at gambling. The stakes are much lower here, and — as Dickens implies — Crowe leans pretty hard on how Charles Lovell’s surrender to temptation led to melodramatically dire consequences, including a character literally dying of shame. A soldier named Herbert is engaged to Charles’s sister, Emily, and he loses all of his savings to Charles’s cheating. Crowe writes:

[Herbert] determined instantly to pay the debts, but he knew that his own prospects were ruined for life; he wrote to the agents to send him the money and withdraw his name from the list of purchasers. But how was he to support his mother's grief? How meet the eye of the girl he loved? . . . The anguish of mind he suffered then threw him into a fever, and he lay for several days betwixt life and death, and happily unconscious of his misery.If that isn’t enough suffering, Herbert recovers — and, the day after he learns Charles has been accused of cheating, the soldier “was found a corpse, and a discharged pistol lying beside him.” If that isn’t enough suffering, Emily hears about her brother’s cheating and her fiancé’s suicide, and wouldn’t ya know it:

Before Herbert's funeral took place, Emily Lovell was lying betwixt life and death in a brain fever.This seems to be where Dickens stepped in and quite possibly saved Emily’s life or, at least, reduced her pain with a red pencil. In the end, she accompanies Charles in self-imposed exile in Australia. This, one presumes, is preferable to death, if only for the nice beaches down under.

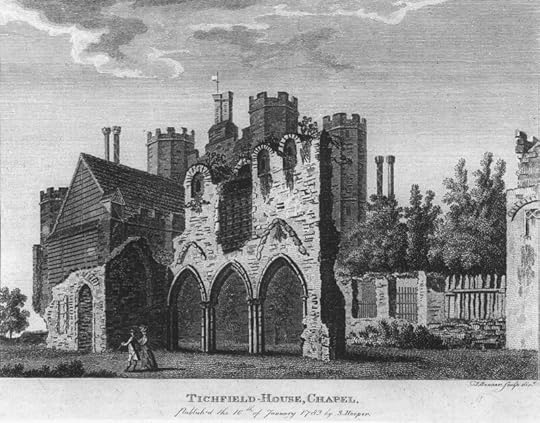

In that Crowe uses an actual landmark in “An Adventure in Terni,” I wondered if she does the same in “Loaded Dice.” Does what she describes as a towered abbey in “T–,” somewhere in the southern counties of England, refer to Titchfield Abbey in Hampshire? This illustration from several decades earlier appears in Francis Grose’s The Antiquities of England and Wales (1784). A Lesson about the Dangers of Gambling — or A Lesson about the Dangers of Poverty?

In that Crowe uses an actual landmark in “An Adventure in Terni,” I wondered if she does the same in “Loaded Dice.” Does what she describes as a towered abbey in “T–,” somewhere in the southern counties of England, refer to Titchfield Abbey in Hampshire? This illustration from several decades earlier appears in Francis Grose’s The Antiquities of England and Wales (1784). A Lesson about the Dangers of Gambling — or A Lesson about the Dangers of Poverty?It would be easy to see “Loaded Dice” as a didactic, if not downright preachy, tale about the dangers of gambling. That, after all, is the root of all the high tragedy here. However, the title might be more significant than just one of the ways Charles was found cheating. (He also manipulates the cards to his own advantage.) Were the metaphorical dice, the Dice of Fate, loaded to the disadvantage of Charles, a good guy who happened to be born into poverty?

Crowe spends a good amount of time establishing that Charles is the product of a good family, and here’s where the two travelers/narrative frame does play an important role. The travelers discuss how the cheater’s father is the local vicar, who married for love rather than for money and who was promptly disinherited by a rich uncle as a consequence. Though poor, Charles was raised in an idyllic, rural environment. The narrator’s companion even says that “poverty might be poetical and graceful here.” This is not at all the filthy streets and grimy workhouses of London, where Dickens’ Oliver Twist grew up. In fact, one might argue that what Dickens had done to link crime to urban poverty in that 1838 novel is being done here for the rural equivalent. Financial desperation very much explains Charles’s succumbing to cheating, illustrating how criminals are made, not born. (That this debate was on people’s minds is suggested by Cesare Lombroso formally articulating the “born criminal” theory in 1876. An English translation is here.) Thinking of Crowe’s short story in these terms helps to make it a more sophisticated piece than the “horribly dismal” one that Dickens deemed it.

A Couple of (Probably Pirated) ReprintsAnd this might explain why not everyone agreed that “Loaded Dice” is as overwrought as Dickens did. A New York publisher reprinted it in Stories from Household Worlds (1850), a series promoted as offering “the choicest literary repasts of the day.” In a similar anthology from another New York published, one titled Pearl Fishing: Choice Stories from Dickens’ Household Words (1854), the editor introduces the contents as “judicious selections” from Dickens’ journal, “embracing some of its best stories.” Well, if nothing else, “Loaded Dice” was being sold as quality stuff.

The promotional section for the 1850 reprint of “Loaded Dice,” published in New York.

The promotional section for the 1850 reprint of “Loaded Dice,” published in New York.However, Crowe still goes unnamed in both of those anthologies, and the words “by Charles Dickens” on the title page of the earlier one along with “from the pen of Charles Dickens” in its promotional copy can easily mislead a reader into thinking he’s the author. Transatlantic copyright protections were a mess at this time, and it’s entirely likely Crowe received neither a cent nor a pence from the New York publishers. The same can be said when the story reappeared in Recollections of a Policeman (1856), published in Boston, Massachusetts. Here, the author is blatantly named as “Thomas Waters, an inspector of the London Detective Corps.” Oh, the irony: falsely attributing a pirated tale to a police officer. Nonetheless, this shows that Crowe’s work was being understood as a piece of crime fiction.

A couple of decades later, another victim of pirating — an author known as Mark Twain — would campaign for better domestic and international copyright protection. As for Catherine Crowe, her crime story would be stolen away. The Dice of Fate were loaded to her disadvantage.

September 4, 2024

Two Tales Illustrating How, Even as a Minor Character, Baba Yaga Is Unpredictable

English translations of Russian Baba Yaga folktales suggest that oral storytellers adapted the character — who probably would’ve been familiar to their fireside listeners — to the needs of the tale being told. Sometimes, she’s a witchy major character, the narrative’s antagonist. Other times, she’s a minor character, but her villainous nature still frustrates the protagonist’s efforts to achieve some goal. Occasionally, she acts as a minor character, but she generously gives trustworthy guidance to the hero (along with a good meal and a night’s sleep). If you’re ever journeying through the woods and come upon Baba Yaga’s hut, beware — she’s unpredictable.

The range of Baba Yaga’s fickle disposition is well illustrated by “The Frog-Tsarevna” and “The Footless and Blind Champions.” She appears only briefly in both of these. Let’s start with her in a good mood.

The Frog-Tsarevna; Or, Baba Yaga Ain’t So Bad — SometimesI was reminded of the Celtic legend of the selkie when reading “The Frog-Tsarevna” (a.k.a. “The Frog Princess” and “The Frog Queen”), since the title character can remove the skin of her amphibious self to become a woman. Of course, she’s a frog-woman, not a seal-woman, but true to selkie lore, her husband restricts her freedom by stealing her skin. He even burns it!

How Ivan came to marry Vasilisa Premudraya, the woman who’s perfect except for the frog thing, comprises the tale’s first act. Act II introduces his destroying her skin, and that’s when Vasilisa informs Ivan he should’ve been more accepting. Following R. Nisbet Bain’s 1895 translation, Vasilisa laments:

"Alas! Tsarevich Ivan! what hast thou done? If thou hadst but waited for a little, I should have been thine for ever more, but now farewell! Seek for me beyond lands thrice-nine, in the Empire of Thrice-ten, at the house of Koshchei Bezsmertny." Then she turned into a white swan and flew out of the window.Ivan! You royal idiot! To be sure, he recognizes that he’s been too controlling and humbly begins a quest to win back his bride. Along the way, Ivan meets Baba Yaga.

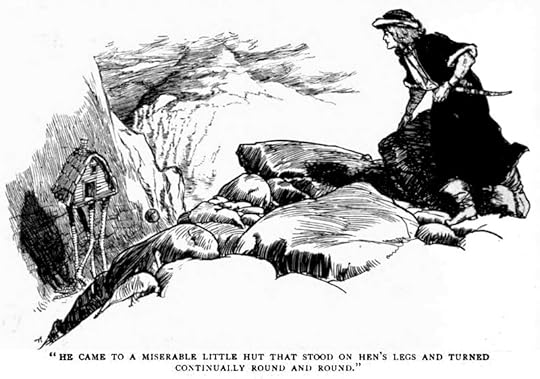

H.R. Millar’s illustration for Post Wheeler’s translation of the tale, published in a 1912 issue of The Strand magazine.

H.R. Millar’s illustration for Post Wheeler’s translation of the tale, published in a 1912 issue of The Strand magazine.We’re sure it’s Baba Yaga thanks to her quirky hut that rotates on chicken legs. In addition, the piece features Koshchei the Deathless, who has a key role in “Marya Morevna,” a better-known work in which Baba Yaga appears. But “The Frog-Tsarevna” can be grouped with those showing Baba Yaga’s kinder side, since her only role is to lend a hand to Ivan’s retrieval of the shape-shifting Vasilisa. There are no small roles — only small Slavic folklore figures. And Baba Yaga is not too high-minded to accept a small role.

The Footless and Blind Champions; Or, Baba Yaga as a Vampire?Our mercurial friend plays another minor part in “The Footless and Blind Champions” — again, not coming onstage until well after the curtain rises — but she’s far more sinister here. I’ll cut to the chase.

So a tutor named Katoma crosses paths with a very unpleasant princess named Anna when he helps his tutee win her hand in marriage. The tutee is another dude named Ivan (or, if it’s the same dude, he really needs to consider remaining a bachelor). Well, her Royal Unpleasantness orders that Katoma have his feet amputated. Luckily, he then meets a man who was previously blinded by Anna, and they work together to kidnap a merchant’s kind daughter, who presumably suffers from Stockholm syndrome, and the three settle into a happy domestic arrangement. You with me here? Yes, this is one of the wackier tales that, to be honest, I really love.

The trio’s happiness is short-lived, though. Following W.R.S. Ralston’s 1873 translation:

No sooner have the heroes gone off to the chase [for food], than the Baba Yaga is there in a moment. Before long the fair maiden's face began to fall away, and she grew weak and thin. The blind man could see nothing, but Katoma remarked that things weren't going well. He spoke about it to the blind man, and they went together to their adopted sister, and began questioning her. But the Baba Yaga had strictly forbidden her to tell the truth.By sucking her breasts, Baba Yaga drains the life out of the merchant’s daughter. I don’t recall seeing this vampirism in any of the other folktales I’ve read for this project. Furthermore, other than the name, there’s not much here to confirm that this the same Baba Yaga character as in those other stories. There’s no hen-legged hut, no flying mortar, no penchant for eating people, etc. However, there is a “fountain of healing and life-giving water,” which is key to the “Water of Youth, Water of Life, and Water of Death,” one of those tales in which Baba Yaga acts as a helpful guide.

The blind man and Katoma catch Baba Yaga and force her to divulge the location of the restorative waters. Even in this, she’s wily — but ultimately she guides them to the water that will give them back what Princess Anna took from them. Somehow, they promptly convert the princess to a repentant and more obedient life as Ivan’s wife. Katoma then marries the kidnapped merchant’s daughter. This seems very much a story about overpowering women and making wives of them, be they as dangerous as Anna or as charitable as the merchant’s daughter.

What happens to this oddly vampiric Baba Yaga? Presumably unmarriageable, she’s killed. Perhaps the best that can be said is: she’s been killed before, and that doesn’t seem to stop her.

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THE

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THEWHISPERS OF WITCHERY

MAIN PAGE.

August 28, 2024

Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit: A Stretch of Tracks in Trumbull, Texas

A Purposeless or Just Mischievous Ghost?

A Purposeless or Just Mischievous Ghost?In the 1880s, train passengers traveling between Houston, Texas, and Dallas took the Houston and Texas Central Railroad. Along the way, they would travel between the towns of Palmer and Ferris. By 1890, such passengers might’ve encountered the spirit of a man who had lost his life between those towns, in a stretch that had, by then, become known as Ghost Hill. More likely, they would’ve been inconvenienced by the phantom, whose activities sometimes prompted the crew to bring the train to an unscheduled halt.

From North Carolina’s Asheville Daily Citizen, 4-11-1890, p. 3

From North Carolina’s Asheville Daily Citizen, 4-11-1890, p. 3The article above — which also ran in papers from Washington to Maryland — shows that the phantom made itself known by repeatedly blowing the whistle and ringing the bell. Apparently, there wasn’t any particular reason for this. No train coming the other way. No damaged tracks ahead. Not even so much as a stray longhorn to consider. Unlike some railroad ghosts, this one seemed simply to be proclaiming its presence or maybe pulling a prank on old colleagues.

Speaking of pranks, a different 1890 article also refers to the Ghost Hill ghost. Titled “A Brakeman’s Ghost,” it was published in the Fort Worth Daily Gazette, but the reporter was less concerned with the paranormal phenomenon and more with how the spot’s reputation inspired a fireman to masquerade as the spirit and scare a co-worker. I’d be tempted to shrug off both articles as resulting from a prank — a tall tale told by trainmen — if Ghost Hill itself hadn’t been named for its alleged spectral visitor.

Searching for the SourceSometimes, when researching these railroad hauntings, I’ve been able to confirm or, at least, lend credence to an accidental death said to account for the ghost. Other times, I haven’t. (Wrecks, of course, are easier in this regard than are individual fatalities, since they’re more “newsworthy.”) This case is especially difficult because that widely reprinted article says the restless victim was a “fireman,” the Daily Gazette article says he was a “brakeman,” and a 1906 article in The Waxahachie Daily Light cites “an Irishman who was killed there when the railroad was being built.” Somewhere along the way, the backstory morphed so that the haunting was attributed to three Mexican accident victims! None of these contradictory sources name names, so it’s tough to know what to search for.

Nonetheless, while hunting, I discovered that the tracks close to Palmer might have been a danger spot. That 1890 Daily Gazette piece places the fatality at “[a]bout eight years ago,” meaning in the neighborhood of 1882. Well, in 1881, the Dallas Weekly Herald reported that a freight train had wrecked “near Palmer.” But there were no injuries. A year later, with fiery wording, the same paper said that, “[j]ust beyond Palmer,” a sharp-eyed engineer narrowly avoided sabotaged tracks, thereby saving northbound passengers from robbery and almost certain death. Again, there’s nothing to account for a ghost. All that can be concluded from these articles is that the tracks in the area of Ghost Hill had a history that was, if not deadly, then marked by calamity and criminal intent.

From

Appleton’s Illustrated Hand-book of American Travel

(1860)Walking the Haunted Line Today

From

Appleton’s Illustrated Hand-book of American Travel

(1860)Walking the Haunted Line TodayTracks remains to this day between Palmer and Ferris, and they run roughly parallel to and west of Interstate 45. Presumably, this is where the tracks were in the 1800s. Ghost Hill was one of several names given to an unincorporated community now called Trumbull, which is pretty small. Conducting an investigation should be fairly easy. Needless to say, any ghost hunters should proceed with extreme caution — those tracks don’t need any new ghosts.

And the investigation might be combined with a visit to nearby Waxahachie, where even a weekend paranormal investigator can enjoy a ghost tour and/or stop by the Munster Mansion, a recreation of the house depicted in The Munsters, that old TV show. However you arrange an outing to check up on the Ghost Hill ghost, please let us know your experience in the comments below.

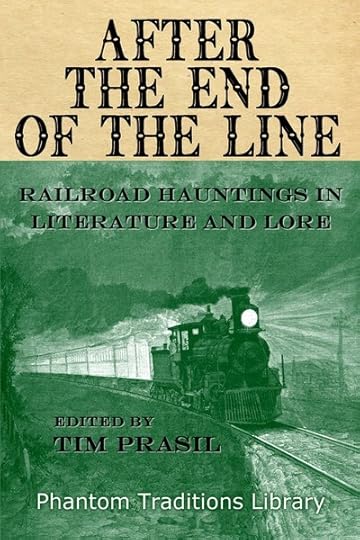

Discover more “Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit” at the page forAfter the End of the Line: Railroad Hauntings in Literature and Lore.

August 13, 2024

The Short Fiction of Catherine Crowe: “The Monk’s Story” (a.k.a. “A Story for a Winter Fireside”)

If you’ve ever read Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein (1818, rev. 1831), you probably learned at least two things: 1) the movies have never done it justice, and 2) it presents a story-within-a-story-within-a-story. Catherine Crowe ups the narrative frames by one in “A Story for a Winter Fireside” (1847), later retitled “The Monk’s Story.” The piece is easier to follow than this chart might suggest, but humor me here:

The outer frame is a third-person narration about Charles Lisle, who is visiting the Grahams at their Christmas gathering. He asks his host to give him a room with a good, working lock. This seems a bit unfriendly, if not downright paranoid, so Mr. Graham and the other guests say such a room will be provided on the condition that Charles explain the reason.Charles does so at the fireside that evening, creating another narrative frame. This one is first-person, and it takes us back to Charles’s travels through France.Early in his tale, Charles repeats an anecdote told to him by Père Jolivet, the prior of the monastery of Pierre Châtel. This first-person story concerns a monk known as Fra Dominique, who calls himself Brother Lazarus. Dominque has the bad habit of walking in his sleep and, while so entranced, attempting to stab people in their beds! Jolivet narrowly escaped such a fate, and afterward, he interrogated Dominique to grasp what happened. (It seems safe to say that Crowe’s inspiration for this part of her tale is the strikingly similar anecdote attributed to Dom Duhaget, “once prior of the Chartreuse convent of Pierre Chatel,” in Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin’s Physiology of Taste: Or, Transcendental Gastronomy . This popular book — revealing the deep roots of the “foodie” movement — was first published in France in 1826.)At this interrogation, Dominique relates a terrible incident from his childhood to Jolivet, creating the core first-person narration. He had been sharing his mother’s bed when he witnessed her murder by stabbing. (And couldn’t a Freudian have a field day with that?) Thereafter, Dominique became plagued by nightmares and sleepwalking.Now, Dominique tells Jolivet that the killer was his ne’er-do-well, hotheaded brother-in-law. But this begs the question of why the monk assumes the role of the murderer in his sleeping reenactments of the traumatic experience. Is he extracting revenge? Is he misremembering who killed his mother? Psychologically denying his own horrible deed? Flat-out lying about it? We can’t really answer that question, but Crowe’s use of these multiple first-person narrators certainly raises the possibility of an unreliable one. It’s along the lines of what Shelley does when the creature, who we know has murdered a child and shrewdly framed a nanny for the crime, still somehow stirs readers’ sympathy by presenting himself as the real victim when narrating his sad story to Dr. Frankenstein. Should we trust the creature? Should we believe the monk?

Ambiguity: thy name is nineteenth-century authors.

Was Crowe inspired by the case of Albert John Tirrell? The year before “The Monk’s Story” debuted, the American Tirrell made headlines for being legally exonerated of murder by using sleepwalking as a defense. If there was no direct influence on Crowe, we still can see the topic was of wide interest in the 1840s. The illustration above comes from a pamphlet titled “Eccentricities and Anecdotes of Albert John Tirrell.”

Was Crowe inspired by the case of Albert John Tirrell? The year before “The Monk’s Story” debuted, the American Tirrell made headlines for being legally exonerated of murder by using sleepwalking as a defense. If there was no direct influence on Crowe, we still can see the topic was of wide interest in the 1840s. The illustration above comes from a pamphlet titled “Eccentricities and Anecdotes of Albert John Tirrell.”We then bounce back to Charles’s frame to learn he next journeyed to Spain. And it’s there that Dominique, now thought to be dead, rises again. “Brother Lazarus,” indeed! With Charles as his target now, the monk yet again reenacts his childhood trauma, ending with another narrow escape. Crowe ends the fireside tale by briefly returning to that third-person frame. SPOILER: Charles is granted a room with a working lock.

But this is more than just a tidy ending. The chances are very, very slim that Dominique would invade Charles’s bedroom back home in England. But Charles, like the beleaguered monk himself, has suffered a trauma — and that’s something that haunts a person deeply and irrationally. Interestingly, even Dominique’s return from “death” mirrors how the effects of trauma resurface relentlessly and can’t be buried. This idea runs throughout “The Monk’s Story,” and it shows an understanding of the human psyche that would come to be diagnosed and treated by psychoanalysts in the two centuries to follow. We might say Crowe was ahead of her time — if not for the similar psychological insights being made by her contemporaries such as Nathaniel Hawthorne, Edgar Allan Poe, and others. Crowe is working on the same level as these better-remembered authors here.

To be sure, “The Monk’s Story” is one of Crowe’s most powerful and thought-provoking pieces of short fiction.

July 29, 2024

W.E. Ord: An Early Proponent of the “Ghosts as Detectable Energy” Theory

I’m far from an expert on how ghosts are understood in our present age. However, the array of equipment used by paranormal investigators, from EMF meters to EVP recorders, seems to suggest that the goal is to detect is some form of energy, from electromagnetic to psychic. In addition, I have noticed in my brief encounters with paranormal investigators that the word “energy” is often spoken. I sense it’s important an important part of ghost-hunting vocabulary these days.

However, in my research into the long history of ghost-hunting, I haven’t run into many sources that use that term. That’s why I was very interested to find an 1897 essay titled “A Scientific View of Ghosts,” in which W.E. Ord mentions energy by name while indirectly endorsing the use of “ghost-hunting tools.” After noting how our unassisted senses allow for only fleeting and possibly illusory glimpses of spectral phenomena, Ord explains that special equipment, from photographic cameras to magnetic compasses, might be tapping into the ghostly realm. He writes:

Recent science has shown that there is probably a world of energy and matter hidden from our ordinary senses, of which we can only conjecture from the suggestions obtained when the photographic plate records more than the human eye is ever capable of seeing or the magnetic needle responds to an influence quite unfelt by our dull senses. Now it may be that it is in such a hidden world that ghosts have their existence — spirits finding a dwelling-place in forms as much material as those of ordinary human beings but of an essentially different, and perhaps more ethereal, character. Into their hidden world of peculiar and unknown energy, mankind cannot usually enter, but at critical times in a man's life, corresponding to the fitful and occasional appearances of ghosts, his senses may be abnormally developed, so that — as with the photographic camera — he sees more than his eye is ordinarily capable of seeing, and may become conscious by sight, or hearing, or touch, of that hidden world in which ghosts live, and move and have their being.On the one hand, there’s not a lot in Ord’s essay that is remarkably new, even in 1897. Essentially, Ord seems to be saying that, at times, almost anyone can temporarily become a “ghost-seer” (or a medium or a psychic or a sensitive, etc.). He illustrates this by referring to “crisis apparitions,” which involve someone perceiving the spirit a loved one at the moment of that person’s death, and these experiences had been discussed at least since 1859.

Albert von Kölliker’s hand, an X-ray taken in 1896 by Röntgen

Albert von Kölliker’s hand, an X-ray taken in 1896 by RöntgenOn the other hand, what I find interesting is Ord’s implication that cameras and even compasses extend our perception into the “hidden world of peculiar and unknown energy,” possibly wherein spirits dwell. (Crisis apparitions, he posits, grant a peek into that world.) When he refers to cameras, by the way, I doubt he’s suggesting spirit photography. It was too controversial, too fraught with fakery, and not exactly the “[r]ecent science” Ord mentions because it had been around for over three decades when the essay appeared. Instead, he probably means X-rays, which had been detected only a couple of years earlier.

It might be interesting to chart how the use of perception-extending equipment — or what I probably shouldn’t belittle as “ghost gizmos” — came to overtake the sit-and-wait nocturnal surveillance method that ghost hunters had relied upon for centuries. Ord’s essay seems to have a place in the roots of that development. (And if you’re interested, so does the “ululometer,” which I discuss here.)

— Tim

July 16, 2024

The Short Fiction of Catherine Crowe: “The Bear Steak”

Around 1845, Catherine Crowe’s short fiction began to appear with her name in the byline (as opposed to being published anonymously). She was identified as “Mrs. Crowe,” but one might wonder if the success of her novels Susan Hopley, Or, The Adventures of a Maid Servant (1841) and Men and Women; Or, Manorial Rights (1843) — both originally published anonymously while The Story of Lilly Dawson (1847) bears her name — had a hand in making her authorship worth noting.

I’ve had to rely on Crowe’s two collections of short fiction, Light and Darkness; Or, The Mysteries of Life (1850) and The Story of Arthur Hunter and His First Shilling: With Other Tales (1861) to confirm that many of her early works were indeed hers. I did not have to do this with “The Bear Steak” (1845), since her name is on it — and I couldn’t have, since it appears not to have been reprinted in her lifetime.

In other words, “The Bear Steak” debuted once Crowe was a fully risen and recognizable star in the British literary sky.

Yet it’s a fairly minor work. “The Bear Steak” is a light piece of dark comedy that illustrates how our enjoyment of a meal isn’t entirely dependent on its taste. A tourist in Switzerland agrees to sample a slice of bear and winds up loving it — at first.

I tried another mouthful as big as the first. 'Indeed,' said I, 'it's delicious! I never could have believed it.'However, that tourist promptly learns that, in the effort to kill the bear, one hunter was left a “shapeless mass of bones and flesh.” His head gone missing. Presumably eaten. Suddenly, the meal doesn’t sit so well in the tourist’s stomach, and off he runs. There it ends. Sometimes you eat the bear, but sometimes the bear you’re eating partially devoured someone else. Forgive the strained pun, but I very much admire Crowe’s grisly sense of humor here.

From Phillis Browne’s

Field Friends and Forest Foes

(1877)

From Phillis Browne’s

Field Friends and Forest Foes

(1877)As I delve into Crowe’s short fiction, I’m enjoying how much she’s defying my expectations and proving to be a far more versatile writer than The Night Side of Nature (1848) and Ghosts and Family Legends (1859) might lead one to believe. She wasn’t confined by supernatural, crime, or even domestic-drama subjects, and I wonder if short stories afforded her room to stretch her talents a bit more than her novels and other books did.

July 2, 2024

The Next Three Volumes Spotlighting Sherlock Holmes-Era Criminal Characters Have Been Selected. Let the Proofreading Begin!

The next phase of the Curated Crime Collection — which I’m calling “The Crime Wave Crests” — will feature four authors and four criminal characters. The rogues’ gallery includes:

Clifford Ashdown’s Romney PringleJosiah Flynt’s Ruderick ClowdMiriam Michelson’s Nance Olden (combined with Flynt)G. Sydney Pasternoster’s the Motor PirateReaders can enjoy the “complete crimes” of Pringle, whose adventures were originally published in two magazine series for a total of twelve adventures. The Motor Pirate is featured in another “complete crimes” volume, originally published as a novel and its sequel, but published here all in one book.

Romney Pringle applies yet another perfect disguise, only one of his criminous skills.

Romney Pringle applies yet another perfect disguise, only one of his criminous skills.Clowd and Olden are “complete,” too, but both appeared in novels short enough that I combined them in a single “partners in crime” volume. They work together nicely because Flynt and Michelson, both American authors, each brought a unique sensibility to the wave of criminal-focused fiction that followed Sherlock Holmes’s original big splash in mystery fiction. Flynt’s novel has a jagged edge of realism while Michelson’s transfers the feeling of comedic farce from the stage to the page. If I were forced to recommend just one volume in the Curated Crime Collection, it might be this two-in-one volume. I’m very glad I found them.

But that’s true of each book in this series. Carefully reading a variety of material — and choosing the very best of it — is at the heart of the Curated part of the Crime Collection, after all. (I discuss the process of rejecting some of the contenders here.)

Selected But Not ProofreadUnfortunately, all of this doesn’t mean the next three volumes will be available anytime soon. The formatting and proofreading process now begins, and that takes time. Not long ago, I told a writer that I have my own indy press, and without hesitation, she informed me that books published independently are filled with typos and other mistakes. She said it to my face. She said it to my Ph.D.-in-English face! But the stereotype exists for a reason, and far too often, that accusation is justified.

Rest assured, I do my Ph.D.-in-English-face’s best to fix errors. Along with my own efforts, I have two remarkably keen proofreaders. While mistakes do slip through, I must say I’ve found such flubs in books published by the most esteemed university presses. It’s aggravating but inevitable.

So when will The Complete Crimes of Romney Pringle, The Rise of Ruderick Clowd & In the Bishop’s Carriage, and The Complete Crimes of the Motor Pirate be available? I can’t be any more specific than: this autumn. And then work begins on the three volumes of “The Crimes Wave Crashes”!

In the meantime, the three volumes of “The Crime Wave Rises” are available. Learn more about them here.

June 21, 2024

The Short Fiction of Catherine Crowe: “An Adventure in Terni” (a.k.a. “A Traveller’s Tale”)

The earliest short story written by Crowe that I’ve located so far debuted in 1841. It appeared in Chambers’ Edinburgh Journal with the fairly lackluster title of “A Traveller’s Tale.” When reprinted in Crowe’s collection Light and Darkness; Or, The Mysteries of Life about a decade later, it was retitled “An Adventure in Terni.” If not zippier, at least the new title is more specific.

Toward the finale, Crowe’s unnamed narrator refers the incident he and a companion encountered while traveling through Italy as a “mystery.” To be sure, it involves a murder, the victim having been pushed off of what one can presume is Cascata delle Marmore in Terni. But the victim’s husband is a strong suspect right from the start — the only suspect throughout — and he’s convicted and executed in the end. So there’s no struggle to identify the culprit here. It isn’t a whodunit, in other words.

“Falls of Terni,” painted by J.D. Harding and engraved by Edward Franics Finden, taken from

Finden’s Illustrations of the Life and Work of Lord Byron

(1834)

“Falls of Terni,” painted by J.D. Harding and engraved by Edward Franics Finden, taken from

Finden’s Illustrations of the Life and Work of Lord Byron

(1834)Instead, this tale fits neatly into the whydunit mold. We don’t get much information on how the two travelers unearth the backstory to the murder. Maybe they just asked around. It’s not especially important, though, because Crowe’s focus is the loves of two brothers. And the arranged marriage that led one brother to commit suicide and the other to commit murder. And the poor woman who loved the “wrong” brother.

Romantic entanglement seems to be a frequent element in Crowe’s short fiction. At times, this leads to complexities and a cast of characters more befitting a novel than a short story, but she keeps things very manageable here. I didn’t feel the need to start taking notes on who loves whom, who doesn’t love whom back, and who flat out resents whom.

In fact, it’s curious that Crowe shows a knack for tale writing in this early work that isn’t always evident in her later stuff. I found “An Adventure in Terni” to be a pleasant illustration of how the strong currents of our passions can whirl and swirl, sweeping us to a moral plummet. Crowe creates a disastrous and deadly waterfall, if you will, for both the killer and the killed.

June 11, 2024

Will There Be a Third Season of Tales Told When the Windows Rattle?

Tales Told When the Windows Rattle is a YouTube series/podcast featuring my dramatic readings of stories found in various volumes published by Brom Bones Books. I put each book’s sales pitch at the very end so that it’s easily avoided. Sure, I want to sell books. But I also like to ham it up and to contribute to the revival of the old tradition of telling spooky stories by a cozy fireside during wet or wintry weather.

However, after finishing Season Two, my recording environment was invaded by a mechanical monster called an actuator. It has something to do with the HVAC system in my apartment. All I know is it began to snarl and growl and hiss — and repairs were not coming anytime soon. In addition, I lived on Main Street, so recording already involved pausing for passing fire engines or drivers who find great joy in being heard for blocks around. The combined clamor was simply too much for me to proceed with a third season.

But I recently moved! To a much quieter apartment! On a much quieter street!

I’m still not absolutely sure there will be a third season of Tales Told, but it looks promising. I hope this is welcomed news for those who have enjoyed listening to my readings while watching a slow swing from indoor fires to outdoor storms on the YouTube series. I hope it’s good news for those who preferred the audio-only version on Spotify or Apple Podcasts. Naturally, if Season Three does materialize, I’ll let you know.

For now, if you’ll excuse me, I’m still unpacking.

— Tim