Tim Prasil's Blog, page 11

May 17, 2023

Baba Yaga, “Marya Morevna,” and Several Sets of Three

Baba Yaga has a pivotal — yet relatively minor — role in the folktale “Marya Morevna,” a.k.a. “The Death of Koshchei the Deathless.” Prince Ivan is the protagonist, Koschei the Deathless is the antagonist, and Marya Morevna is the “prize” over whom they fight. This is one of many Russian folktales transcribed by Alexander Afanasyev and then translated into English by W.R.S. Ralston (1873), Nathan Haskell Dole (1907), and Leonard A. Magnus (1916). I’ll be following Ralston’s version.

I refer to Morevna as a “prize,” but she’s certainly no damsel in distress — at least, not at first. When we first meet her, she’s a great warrior, and that’s how Ivan meets her, too. After some business with marrying off his sisters, he embarks on a journey. He comes upon “a whole army lying dead on the plain,” and a survivor tells him the massacre is the work of Morevna. Apparently, Ivan found this mass bloodshed enticing because, while another man might flee in terror, he goes to meet the mighty Morevna. After spending some time in her tent, “he found favor in the eyes of Marya Morevna, and she married him.” It’s interesting to see that they wed — not because Morevna pleased Ivan — but because Ivan pleased Morevna. To be sure, we read: “The fair Princess, Marya Morevna, carried him off into her own realm.”

The trouble starts when, after a bit of married life back home, Morevna gets the itch for more slaughter. Preparing to leave, “she handed over all the housekeeping affairs to Prince Ivan.” If you know the tale of “Bluebeard,” you’ll recognize a gender swap when Morevna grants her husband the freedom to go just about anywhere in the house — “only do not venture to look into that closet there,” Morevna warns. Well, wouldn’t you know it? Once she departs, Ivan pokes his nose into that forbidden closest. Instead of the bodies of Bluebeard’s murdered wives, he finds Koshchei the Deathless bound in chains.

Long story short, Koshchei dupes Ivan into releasing him. The villain then kidnaps Morevna, who suddenly and disappointingly transforms into a damsel in distress after having been the one who managed to subdue the fearsome and reputedly immortal Koshchei. Next, Ivan goes to work to rescue his bride. Considering Ivan’s powerful wife and his formidable rival, one might see this as a story about a man proving his value as a husband.

Fine, But What About Baba Yaga?One might also see “Marya Morevna” as a story about a man learning he must kill those who get in his way. Ultimately, Ivan wins back his wife by proving that Koshchei’s nickname “the Deathless” was an overstatement. To accomplish this, Ivan must first secure a magical horse from Baba Yaga. And he gets one from her. But he kills her, too, in the process.

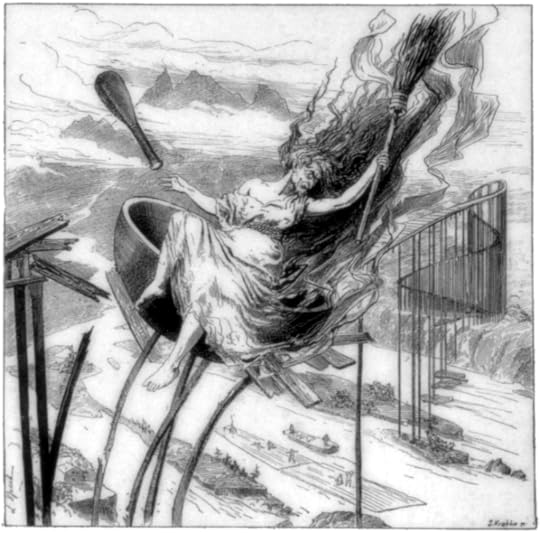

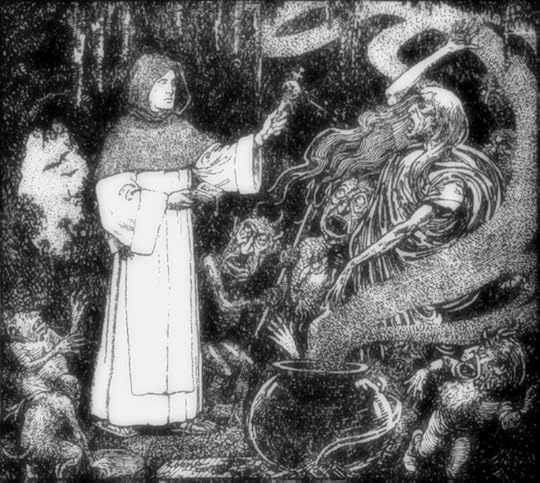

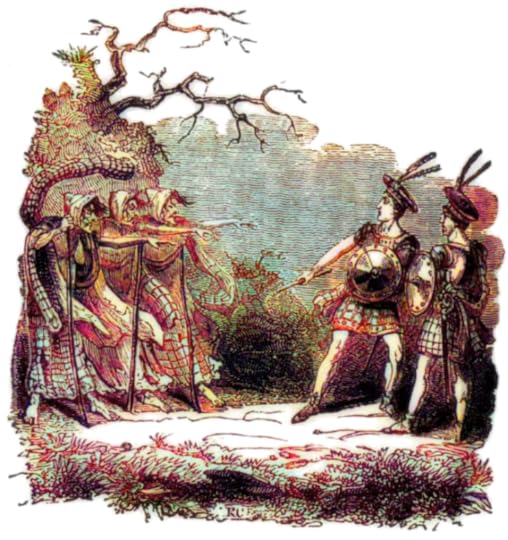

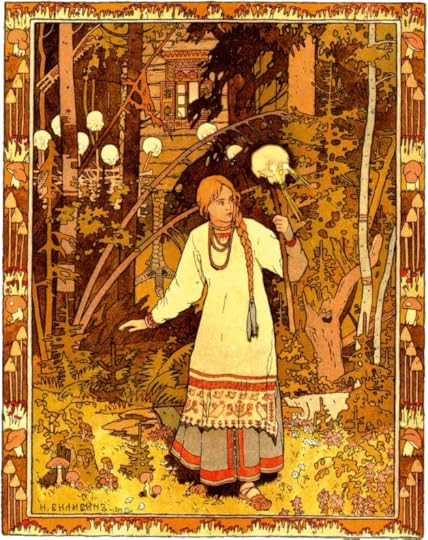

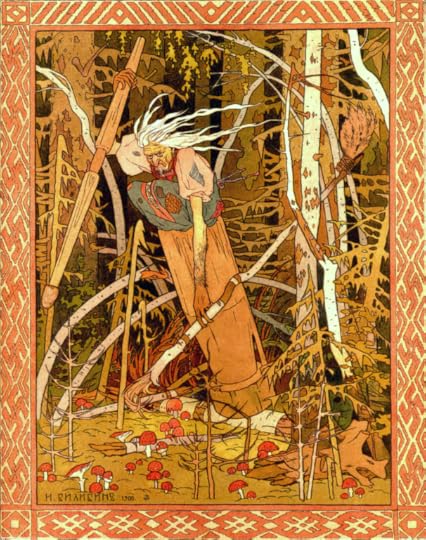

Baba Yaga’s final moments as illustrated in Andrew Lang’s The Red Fairy Book (1890), where Ralston’s translation appears with the title “The Death of Koshchei the Deathless.”

Baba Yaga’s final moments as illustrated in Andrew Lang’s The Red Fairy Book (1890), where Ralston’s translation appears with the title “The Death of Koshchei the Deathless.” This portion of the folktale echoes another one that Ralston calls simply “The Baba Yaga.” In that story, an unnamed girl is forced to ask Baba Yaga for a needle and thread. On her way to the witch’s hut, she performs acts of kindness that become reciprocated once the girl is escaping from being eaten by said witch. In “Marya Morevna,” after failing repeatedly to rescue Morevna, Ivan realizes he needs a horse that can out-magic Koshchei’s magic horse. Who’s a better source of enchanted steeds than Baba Yaga? On his long trek to her hut, famished Ivan shows mercy by respecting requests to not eat a talking bird’s young, a talking queen bees’ honeycomb, and a talking lioness’s cub. Sure enough, these grateful creatures then play key roles in his appropriating one of Baba Yaga’s horses.

Chase scenes seems to be pretty common in the Baba Yaga tales, and there’s also one here. However, this time, the witch falls to her death. Ivan, you see, has a very useful handkerchief that converts into a bridge when needed. It’s needed when he’s absconding with one of Baba Yaga’s horses, and — well, you can imagine what Ivan does with that handy hanky after he crosses the bridge with the witch in hot pursuit. “There truly did she meet with a cruel death,” as Ralston puts it.

It’s not stated in the story, but something tells me Baba Yaga can be resurrected faster than you can say “Dracula in a Hammer film.”

Riffing on TriosFill in the blanks: The ___ little pigs. ___ blind mice. Goldilocks and the ___ bears. There’s often a set of three in fairy tales. While they have little to do with Baba Yaga, sets of three appear so frequently and almost heavy-handedly in “Marya Morevna,” it’s worth addressing. The three elephants in the room, as it were.

Here are some of the “trios” this tale includes:

Before Ivan meets Morevna, we learn that he has three sisters.Those three sisters marry three bird-men — a falcon-man, an eagle-man, and a raven-man — over the course of three years. In essence, Ivan is then free to go meet his own wife.Koshchei drinks three buckets of water before regaining strength enough to escape from Morevna’s closet.On his trek to rescue Morevna, it takes Ivan three days to come upon his first bird-brother-in-law’s palace, three days to find the second, and three days to find the third. These encounters will prove helpful later.On Ivan’s third failure to rescue Morevna, Koshchei’s gratitude for having been freed is exhausted. He kills Ivan. His three bird-brothers-in-law bring him back to life, giving him that handy handkerchief/bridge and paving the path for Ivan to kill Koshchei back!On his way to Baba Yaga’s hut, Ivan doesn’t eat 1) the baby bird, 2) the honeycomb, or 3) the lion cub.I’ll stop there. I think you see my point, and you probably did after the third example. There’s so much playing with sets of three in this tale that I wonder if it might be part of the fun. Is it a parody of other folktales? Is it a method for an oral storyteller to remember this weird and winding narrative? Is it a kind of musical motif? Think of how Beethoven opens his 5th Symphony with sets of four: Bum-bum-bum-bummmm! Bum-bum-bum-bummmm! Bum-bum-bum-bum, bum-bum-bum-bum, bum-bum-bum-bummmm. Bum-bum-bum-bum, bum-bum-bum-bum, bum-bum-bum-bummmm. Well, perhaps that’s a stretch. Nevertheless, whatever the reason behind all the sets of three in “Marya Morevna,” they become an intriguing part of the story.

Any thoughts on this or some other element in this piece from the Baba Yaga playlist? “Marya Morevna” is among the oddest selections I’ve found in this body of folklore (though “Yvashka with the Bear’s Ear” gives it some stiff competition in terms of wackiness). I’d love to learn how others react to it. Feel free to comment below.

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THE

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THEWHISPERS OF WITCHERY

MAIN PAGE.

May 14, 2023

Reviving the Works of Charles Fenno Hoffman

Almost all the volumes created for Brom Bones Books have been proofread by Kelly Keener (among others). She shows astonishing precision, for instance, noticing in a tiny footnote that there’s a double-space when a single-space is correct. Like myself, Kelly feels a kinship with American authors of the 1800s, and not too long ago, the Edgar Allan Poe Review published her article describing an intriguing letter related to that author, a letter she had discovered!

Kelly has a particular interest in a great but largely forgotten writer named Charles Fenno Hoffman. I’ve been skimming over some tributes to Hoffman that appeared in 1884, the year he died. There’s a common thread. One says his “name will always be associated with the early triumphs of American literature,” and another says that name “once held a conspicuous place in American literature, and…is still held in high regard by reading people.” Reading his fiction today, one might be reminded of the weirdness of Poe or — since Hoffman enjoyed exploring the frontier — the wilderness of James Fenimore Cooper. That second obituary says that, upon his death, Hoffman was best remembered for his poetry and that his volumes thereof “are prized by collectors of American books.” Still, his renown has faded in this area, too, unlike Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, his contemporary, or Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson, who came a bit later.

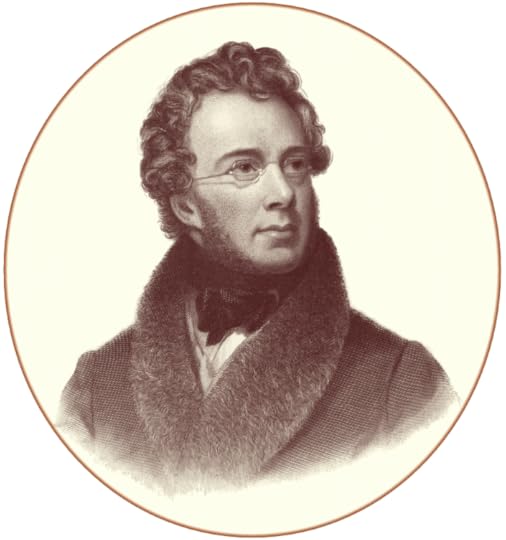

Charles Fenno Hoffman (1806-1884)

Charles Fenno Hoffman (1806-1884)At some point, Kelly and I discussed the idea of having Brom Bones Books publish a collection of selected works by Hoffman. After all, a new generation of readers — including fans of, say, Poe or Cooper or Longfellow — might very much appreciate having a handy introduction to him. That’s exactly how we approached it, as sort of assigned readings for a Hoffman 101 class.

I’m pleased to announce that Tales, Sketches, & Poems of Charles Fenno Hoffman, edited by Kelly Keener, will be available for purchase by this summer. I’ll share more about what it includes — and probably more about Hoffman himself — in the coming weeks. Until then, click on cover below to learn more.

— Tim

May 7, 2023

Sympathy for the Witch: Gloucester’s Peg Wesson Legend and the Escalation of Vengeance

Vengeance often appears in witch legends, at least, those rooted in the U.S. A woman who might or might not be a witch is exiled or executed for the crime, and before making her exit, she casts a curse. The curse comes true, too, though it’s left unclear if its power stems from Divine Justice or something much more evil. This narrative motif also pops up in Massachusetts’s Peg Wesson legend. A short history lesson might be useful to better understand the context of this folktale.

Before the American Revolutionary War (1775–83), Britain and its North American colonists waged a series of wars against France and its North American colonists. Roughly speaking, the battles took place in Canada’s Maritimes and down the east coast of the United States, though these places weren’t called that then. Different indigenous tribes allied themselves with both sides, and the wars on this side of the Atlantic were intertwined with conflicts in Europe. One point of particular interest was the Fortress of Louisbourg, which sat on the eastern edge of what’s now Cape Breton Island in the province of Nova Scotia. In 1745, militia forces from New England, under the command of William Pepperell, joined with the British Royal Navy to seize that fort. They succeeded. (Incidentally, control went back to France under the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle of 1748, but the British captured it again in 1758. After all — and I’m probably oversimplifying here — that fort regulated access to the St. Lawrence River, which allowed the British to take political power in Québec City, Montreal, and finally all of Canada.)

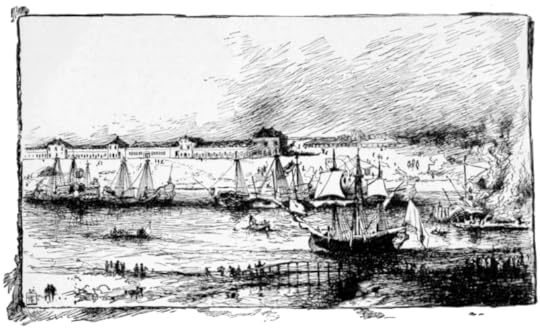

This sketch of Louisbourg is based on a painting and found in

Lieutenant-General Sir William Pepperell, Bart

(1887), by Everett Pepperrell WheelerBabson’s 1860 Transcription of the Tale

This sketch of Louisbourg is based on a painting and found in

Lieutenant-General Sir William Pepperell, Bart

(1887), by Everett Pepperrell WheelerBabson’s 1860 Transcription of the TaleSome of the soldiers who followed Pepperell in 1745 came from Gloucester, Massachusetts. The setting of the legend is that town shortly before those soldiers departed. I’ve found no earlier written record of the tale than what’s in John J. Babson’s History of the Town of Gloucester (1860). His transcription is short, and I’ll shorten it even more. Before heading up to fight the French, a few cocky Gloucester lads decided it’d be fun to pester Peg Wesson, who “was reputed to be witch.” They irritated her enough that “she threatened them with vengeance at Louisb[o]urg.” Once on the battleground, the hooligans noticed a crow stalking them. Unable to kill the bird, “it occurred to one of them that it must be Peg Wesson” and a silver bullet was needed to end her otherworldly counter-pestering. One of the soldiers loaded his gun with some of the silver buttons from his sleeve, and this tactic ended the life of the shape-shifting witch. Or something like that. Back in Gloucester, “at the exact moment the crow was killed, Peg Wesson fell down.” She had somehow broken her leg, and extracted from the wound were “the identical sleeve buttons fired at the crow”! Babson ends the vignette by saying that, while it’s hard to imagine anyone ever believing it, the folktale was told by some Gloucester citizens with “apparent belief in it” within the previous half-century.

Of course, the point of the story is to dazzle the listener with the mystery of the silver button/bullet jumping from Nova Scotia to Massachusetts. Does this prove Wesson was a witch all along? If so, as Babson tells the tale, she is presented as a mostly harmless one. Even when provoked, she just caws a lot. The villains — or, at least, antagonists — are those rowdy soldiers, who might be easily deemed murderers by the end. If the Biblical injunction to “not suffer a witch to live” (Exodus 22:18) was part of their motivation, it goes unstated. Instead, after incurring Wesson’s vengeance for their bad behavior, they decide she transformed into a crow to taunt them — and so they kill her! Wow! Hardly a flattering portrait of Gloucester’s bravest!

But maybe this is really a parable about rapidly escalating vengeance. A is rude to B, B retaliates against A with magic, so A kills B. It’s blunt, but it does make a point: don’t be a bully — especially to seemingly defenseless old women — because it can get ugly fast.

This illustration of the gang of Gloucester soldiers incurring the wrath of Peg Wesson comes from Sarah Comstock’s “The Broomstick Trail,” an 1920 article in Harper’s Monthly.And Duley’s 1892 Adaptation

This illustration of the gang of Gloucester soldiers incurring the wrath of Peg Wesson comes from Sarah Comstock’s “The Broomstick Trail,” an 1920 article in Harper’s Monthly.And Duley’s 1892 AdaptationI have a hunch that the Sarah G. Duley identified as a member of the Cape Ann Scientific and Literary Association in The Gloucester Directory 1882-83 is the very same Sarah G. Duley whose name appears on an interesting retelling of the Peg Wesson legend. If I’m right, the author might have grown up hearing the legend and, though her version adds a level of detail and dialogue typically found in prose fiction, these might have been molded as much by oral tradition as by Duley’s own imagination. I like to think so, anyway.

Acknowledged as having originated in the Boston Transcript, Duley’s 1892 adaptation was reprinted in newspapers from Vermont to Arizona and from North Carolina to the State of Washington. It’s more than a hunch that the legend reached more readers through Duley’s spin on it than through Babson’s history of Gloucester. As I say, she adds some nice touches, such as when the soldiers — now named Martin Sanders, Jacob Ayers, and Tom Goodwin — try to trick Wesson by paying her with fake coins to read their futures. We also get specifics on how the witch-in-feathered-form retaliates: being suspiciously present when Sanders nearly drowns, when Ayers gets his arm crushed, and when Goodwin’s ankle gets chomped by a fox trap. Duley gives A and B clear reasons for retaliation.

Otherwise, Duley’s adaptation echoes Babson’s transcription. The soldiers shoot the crow with silver, and — at the exact moment, roughly 600 miles away — Wesson falls from a broken leg with the same bits of silver found in her wound. Now, though, Wesson dies of her injury and is buried in an unmarked grave. If readers haven’t already been moved to sympathize with the witch, Duley adds another flourish to drive the point home. She rhapsodizes:

Poor maligned, persecuted Peggy! For thee and such as thou there should indeed be, there must be, some happier sphere where the shadows of earth may be forgotten in the glad sunshine of happiness unknown before.Even if the soldiers had garnered sorrow for their woes, Duley makes it very clear that Peg Wesson is the real victim of vengeance gone terribly awry. Indeed, Heaven awaits the witch! Instead of not suffering witches to live, then, audiences of the Peg Wesson legend — and others like it circulating in the U.S. during the 1800s — were urged to pity the suffering of witches.

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THE

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THEWHISPERS OF WITCHERY

MAIN PAGE.

April 30, 2023

Sannikov Land: Another Arctic Island Mapped But Not There

Let’s review. Plover Land, President’s Land, Keenan Land, Crocker Land, and Bradley Land. These are all Arctic islands reliable explorers claimed to have observed in the 1800s and early 1900s. Except for Plover Land, I’ve found them all on maps assumed to be reasonably accurate. But there’s a problem. Subsequent expeditions couldn’t verify the existence of these places — on the contrary, no land at all appeared where they had been reported to be — and the decision was eventually made that none of these islands exist! They no longer appear on maps.

I don’t know for sure why I find this interesting. It fits perfectly with the usual path of scientific progress: a researcher puts forth a claim — in this case, hey, there could be some land in this spot! — and other researchers then go to work to support or challenge that claim. With ongoing verification, the claim advances in validity. Frequently, though, it’s eventually disproved. So why am I intrigued by this pattern of polar misperception? Do these phantom islands qualify as ghosts of a different kind? Is it an illustration of how, under certain circumstances, we should be very careful about trusting our own eyes? Is it a reminder that reality is flexible and funny?

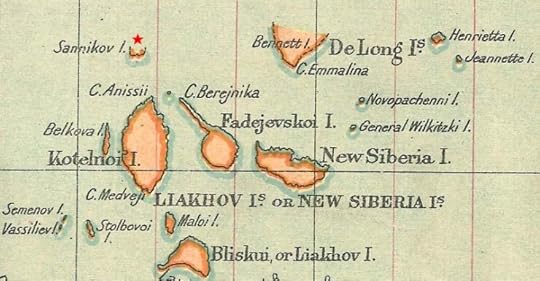

I added a red star to indicate Sannikov Island in this detail from

Stanford’s General Map of the World

(1922). (Though Bennett Island is real, this map misrepresents its size and proximity.) Squint hard, and you can see Sannikov Land on this 1910 map. It’s a bit easier to spot it on this 1919 map.

I added a red star to indicate Sannikov Island in this detail from

Stanford’s General Map of the World

(1922). (Though Bennett Island is real, this map misrepresents its size and proximity.) Squint hard, and you can see Sannikov Land on this 1910 map. It’s a bit easier to spot it on this 1919 map.Whatever the answer, last week, I added another example of this history to my Crocker Land and Other Mapped Mirages of the Arctic page. Sannikov Land was named for the man who first observed it: Yakov Sannikov, a.k.a. Яков Санников, a.k.a. Jacob Sannikoff. This theoretical land, said to lie directly north of Kotelny Island in the New Siberian archipelago, wavered between being there and not being there for over a century. It’s a somewhat complicated history, and it’s a bit tricky to chart the specifics of it. But I’m going to give it a try.

Sannikov Land Was There, Not There, There, and Not ThereOne of my best sources of information is Baron Edward Toll’s “Proposal for an Expedition to Sannikoff Land,” translated and published in an 1898 issue of The Geographical Journal. Toll was a Russian explorer who had claimed to have seen the island before making his proposal to hunt for it, so he might be biased in favor of it existing. Nonetheless, he dates Sannikov’s original sighting between 1805 and 1811. This was followed by attempts to verify the island by Petr Anjou in 1821-23. While acknowledging the difficulties of exploration in that region, Anjou declared that he couldn’t find what Sannikov had seen. Already, the reality of Sannikov Land was in doubt, and Toll says “it disappeared from maps.”

Despite Anjou’s challenge, continues Toll, Sannikov had made a similar claim about what would become called Bennett Island off to the northeast, a claim that was verified in 1881. And local hunters said there is land north of Kotelny Island. And on an 1886 expedition, “during quite clear weather,” Toll himself peered where Sannikov had done so decades earlier and observed “the sharp outlines of four truncated cones[,] like table mountains, from which a low foreland extended towards the east.” The ice had prevented him from reaching the spot at that time, but Toll was inspired to organize a formal search for the island. He even hoped to camp there for a winter.

The news of Toll’s expedition to find Sannikov Land reached as far as Montana, where this illustration appeared in the March 24, 1900 issue of the Daily Inter Mountain.

The news of Toll’s expedition to find Sannikov Land reached as far as Montana, where this illustration appeared in the March 24, 1900 issue of the Daily Inter Mountain.For information on how that expedition turned out, we must turn to other sources. First, The Geographical Journal reported in its April 1902 issue that Toll’s ship, called the Zarya, “passed the supposed position of Sannikof Land without gaining sight of it; so that it must either lie farther north than has been supposed, or have no existence.” Later that year, as Helen S. Wright explains in her book The Great White North (1910) — after Toll had been “[d]isappointed in his hopes of reaching Sannikof Land” — he and a few colleagues never returned to the Zarya after going on an excursion to Bennett Island. Given how important confirming the existence of the island was to Toll and to the expedition that took his life, things looked bleak for verification of Sannikov Land.

Another Expedition, Another RefutationIn 1913, Boris Vilkitsky led an Arctic expedition on the Taimyr and the Vaigach, two ice-breakers. This expedition put the Severnaya Zemlya archipelago — dubbed Nicholas II Land by Vilkitsky — on the map, which was pretty amazing considering how much exploration had been done by that year. (One website calls it “the Last Charted Territory on Earth.”) I can’t find any evidence that settling the Sannikov Land issue was among Vilkitsky’s main goals, but his ship’s log for August 21 reports this: “There had been clear water all these days and a clear horizon, but we had seen nothing of the conjectured Sannikov Land.” This carried weight in making a final decision.

A 1914 announcement in Scientific American says that Sannikov Land was “one of the fruits” of the Vilkitsky expedition. It’s an odd way to word it. The explorers were never able to taste or even pick that fruit.

A 1914 announcement in Scientific American says that Sannikov Land was “one of the fruits” of the Vilkitsky expedition. It’s an odd way to word it. The explorers were never able to taste or even pick that fruit.In the wake of the Taimyr and the Vaigach, Sannikov Land was on its way to vanishing for good. In a 1921 article for Discovery magazine, R.N. Rudmose Brown declares, “We are probably justified in saying it does not exist.” That same year, in the pages of The Geological Review, Vilhjalmer Stefansson put it among those places that, after being reported by credible Arctic explorers, “have kept their places on the chart for one or several generations, but are now gone forever.”

It’s interesting to see how the final days of Sannikov Land overlapped with Robert Peary’s 1907 claim of having spotted Crocker Land and Donald MacMillan’s 1913-1917 Crocker Land Expedition, which played a major part in invalidating Peary’s claim. There are good reasons why some people accuse Peary of having faked his discovery in order to secure more funding. Before passing judgment, though, it’s wise to remember the history of claims about having observed an Arctic island that were afterward determined to be false. Not falsified, mind you. Simply false.

As I say, the Sannikov Land story is now noted on my timeline titled Crocker Land and Other Mapped Mirages of the Arctic. I made some additional changes that will hopefully make things easier to follow there. You can also find lots more related stuff on Charting Crocker Land (Base Camp).

— Tim

April 23, 2023

The Witch of Wookey; Or, The Merciless Monk

— Henry Harrington

In a 1755 issue of Gentleman’s Magazine, an untitled, anonymous poem explains why, in western England’s Wookey Hole Caves, there’s a stalagmite shaped something like a witch. It had been a witch, you see, one who was turned to stone. The poem seems to be based on a local folktale, but instead of penning a trustworthy transcription of the legend, the poet might’ve been adapting it to encourage men to relocate to the nearby town of Wells. After all, the bard claims that the women there were hankering for husbands. At the same time — and perhaps entirely inadvertently — the poem portrays an ecclesiastic witch hunter as acting obliviously and mercilessly, thereby stirring sympathy not just for husbandless women, but also for women who have been zealously condemned as witches.

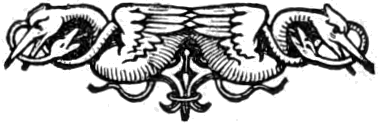

This photograph is from Ernest A. Baker and Herbert E. Blach’s

The Netherworld of Mendip: Explorations in the Great Caverns of Somerset, Yorkshire, Derbyshire, and Elsewhere

.

The cave formation is said to resemble a witch. For best results, squint — and squint hard!

This photograph is from Ernest A. Baker and Herbert E. Blach’s

The Netherworld of Mendip: Explorations in the Great Caverns of Somerset, Yorkshire, Derbyshire, and Elsewhere

.

The cave formation is said to resemble a witch. For best results, squint — and squint hard!The poem was reprinted in a pamphlet the following year with the curious title “Slander; or, the Witch of Wokey,” and that might be easier to read. In the earlier magazine, though, it was introduced this way:

The following stanzas were sent me from Wells in Somersetshire, and assign the reason why ladies of that city are destitute of gentlemen.Those stanzas describe a woman who, while “in her prime,” never had someone to love her: “No gaudy youth gallant and young, / E’er blest her longing arms.” Loneliness made her embittered, which made her into an evil witch. Along with becoming physically hideous (if she hadn’t been all along), she vented her pain on her neighbors, blighting the area’s land and livestock: “She blasted ev’ry plant around, / and blister’d o’er the flocks.” To be sure, she became a general nuisance and “marr’d all goodlie cheer.”

The problem was fixed when a cleric came up from Glastonbury and turned the witch to stone. And that, you see, explains the stalagmite. But as often happens in folktales about someone executed for witchcraft, be it justly or not, there are lingering consequences.

She left this curse behinde,'My sex shall be forsaken quite,Tho' sense and beauty both unite,Nor find a man that's kind.'The lack of marriable men suggested in the introduction, it appears, stems from the curse of a love-starved witch. There’s a lot of blaming the victims in these folktales, and that’s certainly seen in this narrative.

From the fourth volume of a 1923 series called

Legend Land

. These nifty booklets promoted railway travel in western Britain.Or Should We Blame the Witch Hunter?

From the fourth volume of a 1923 series called

Legend Land

. These nifty booklets promoted railway travel in western Britain.Or Should We Blame the Witch Hunter?Another interpretation of this poem, however, emerges if we shift the focus from witch to witch hunter. There’s not much we know about the poem’s “learned wight” who arrives “[f]ull bent” to end the witch’s spree. We learn he’s an ecclesiastic of some kind when told he first recited from a “goodlie book,” presumably the Bible since he next “blest the brook” and then splashed some of the now-holy water on the “ghastly hag.” “When, lo!” continues the speaker, “where stood the hag before, / Now stood a ghastly stone.” So he’s got some powerful magic of his own, but his springs from God.

Later versions of the legend specify the witch hunter’s identity as “a monk from Glastonbury Abbey,” an apt detail given the importance of that monastery in the region’s (and England’s) history. Nonetheless, he’s still said to handle the situation without a moment’s pause, without any investigation of or interest in his suspect’s past. He acts with neither compassion nor mercy. Rather than offer an opportunity for redemption, as one might expect from a Christian cleric, he strides in, flicks some water, and goes Medusa on the witch.

It’s easy for readers to question the ecclesiastic’s prompt “stoning” of his quarry, given the fact that the poet has rooted the witch’s evil in heartache, not in succumbing to Satanic temptation. In other words, at its base, this isn’t a Christianity versus the Devil story. No, it’s one about a representative of Christ versus a woman gone terribly astray. In fact, in the end, the speaker compares the witch to those Wells women cursed to remain unwed: “Shall such fair nymphs thus daily moan! / They might I trow [think], as well be stone, / As thus forsaken dwell….” The poet prompts readers to sympathize with women without men to marry (and I’ll let others delve into the complexities of that). The punished witch is among those women or, at least, once was. Is the zealous witch hunter and man of God, then, accidentally — or perhaps even subversively — cast as the narrative’s heartless villain?

A Very Different Explanation for the Calcified FigureThe poem went on to be included in a number of anthologies, such as this 1765 one, this 1770 one, and this 1801 one. By 1817, it was confirmed to have been written by Henry Harrington, a physician from Bath. But his take on the “witch” of Wookey Hole Caves is not the only one. There’s a very different folktale recorded in an 1804 issue of Sporting Magazine, and it’s presented as a transcription of the story told by a young woman who gave tours of the caves. Instead of having ever been love-starved — instead of being turned into stone by a Glastonbury monk — the witch was simply an evil sorceress who lived before Christ was born. Powerful and omniscient, she “could turn all she did touch into stone.” Here, the witch is rumored to have been attended by the Devil, “but in this they are not clearly sure.” Perhaps thanks to her omniscience, the witch heard that Christ had been born, and knowing that He would have plans to “put away all witchcraft, she grew very sorrowful, and determined to destroy herself.” First, though, she turned other things into stone, from her dinner to a servile lion! Presumably, her last act was to turn herself into stone.

As I say, very different from Harrington’s poem. Unlike Harrington, who wants to stir sympathy for the women of Wells, the Sporting Magazine author has no clear agenda other than to share a cool story told by a tour guide. Does this make it truer to the folktale that was actually shared aloud at Somerset firesides and spinning wheels?

Well, in A Walk Through Some of the Western Counties of England (1800), Richard Wagner summarizes a version of the folktale told to him by another tour guide. In general outline and time frame, it comes closer to Harrington’s than to the one in Sporting Magazine. Here, the witch

had been turned, years ago, into a stone, by a parson, as she was cooking a child in her kitchen, which she had stolen from the village; but [the guide] had heard his grandmother say, her father remembered the wicked old woman, as well as the tricks she played....Indeed, Wagner himself claims that Harrington had “drawn out the oral tale into vision, and secured it to posterity by an elegant versification” with limited poetic license. He then reprints the poem.

So two tour guides are reported to have told two very different versions of how the witch-shaped stalagmite came to be. Both strike me as equally reliable in terms of capturing something of how the story was transmitted orally during the mid-1700s to the early 1800s. Quite possibly, more than one version circulated then. Long afterward, others exploring the Witch of Wookey legend also comment on there being various versions. Though the “stone-suicide” version seems to have vanished over time, others — including one in which the Glastonbury monk is a vengeful victim of the witch — are discussed on this website and this one.

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THE

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THEWHISPERS OF WITCHERY

MAIN PAGE.

April 19, 2023

Turned into a Witch: The Transformation of Black Annis

Shouldn’t All Witch Legends Be Told in Rhyme?Here, if the uncouth song of former days,Soil not the page with Falsehood's artful lays,Black Annis held her solitary reign,The dread and wonder of the neighb'ring plain.

Shouldn’t All Witch Legends Be Told in Rhyme?Here, if the uncouth song of former days,Soil not the page with Falsehood's artful lays,Black Annis held her solitary reign,The dread and wonder of the neighb'ring plain.— John Heyrick, 1797

Once upon a time, the Dane Hills rose to the west of Leicester, England. The area has long since been developed into suburban houses, yards, and streets. It used to be covered with wilderness, though, and within those ancient woods sat a cave. According to legend, a terrible fiend known as Black Annis lurked within this cave, emerging to feast on the local livestock — and on the local children.

My usual work of dusting off old records of witch legends has largely been done for me in the case of Black Annis. A small compilation of excerpts from histories and newspaper articles was offered by Charles James Billson in 1895 (under the heading “Caves”), and there are more mentioned in a 2006 article by Bob Trubshaw. The primary sources referenced by Billson and Trubshaw give good evidence that a cave actually had existed. To be sure, records of it — albeit associated with the names Black Agnes and Black Anny — predate 1797. But that’s the year when John Heyrick’s transcription of the Black Annis legend, told with iambic pentameter and rhyming couplets, was published with the title “On a Cave Called Black Annis’ Bower.” That’s the year the oral folktale was preserved on paper.

The speaker in Heyrick’s poem describes the cave as a place avoided and detested. Shepherds steer clear because, in the past, they’ve tracked their missing animals to the spot. Children and mothers share this fear, since “infant blood oft stain’d the gory den.” Meanwhile, men in general have not “dar’d to meet the Monster of the Green.” Despite this keeping a safe distance, the speaker is able to provide a portrait of Black Annis. Her eyes are “fierce and wild,” and instead of hands, she has talons that are “foul with human flesh.” Her face is “livid blue.” Around her waist, she wears “[w]arm skins of human victims.”

Heyrick ends the poem with the monster vanquished. We read: “But Time, than Man more certain, tho’ more slow / At length ‘gainst Annis drew his sable bow.” I take this to mean that age, not a brave Leicesterian, killed the fiend, that sable bow being a symbol of unavoidable death rather than an actual weapon. The speaker next explains that Black Annis’s corpse was tossed into her own cave, where her “monstrous tropheys” were found in rooms scratched out by her talons. The cave entrance was left open to inspire future generations to retell the legend attached to the place. Heyrick does exactly that, and echoing the “uncouth song of former days” mentioned in the beginning, he ends by implying his own “rough, unpolished song” is a product of fanciful poetry, not of factual history.

Black Annis is not a typical witch, too, if she’s a witch at all. Heyrick makes no mention of spells or curses, of consorting with the Devil, of flying on a broom, or of having a feline or other type of familiar. Instead, Black Annis comes closer to being an especially bloodthirsty spin on the wild man of the wood (a.k.a. “woodwose”) figure, a human or humanoid who exhibits feral behavior and even more body hair than Brett Goldstein. Heyrick suggests this when he describes Black Annis as a “gaunt Maid . . . Whom Britain’s wolf with savage nipple nurs’d.” This is the image of Black Annis that followed for decades.

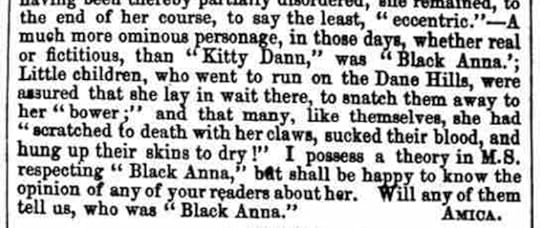

What the Leicester Chronicle ChronicledThe depiction resurfaced in 1846, when John Dudley’s Naology was published. There, the legendary resident of Black Annis’s Bower is said to be “a savage woman with great teeth, and long nails” who “devoured human victims.” In 1874, it was reiterated in an exchange printed in multiple issues of The Leicester Chronicle. Every Saturday, this newspaper offered space for readers to ask questions that might be answered by other readers in future issues. On September 5, someone using the name “Amica” asked what anyone knew about “Black Anna,” clearly referring to the same legend.

From the Leicester Chronicle, September 5, 1874, p. 2

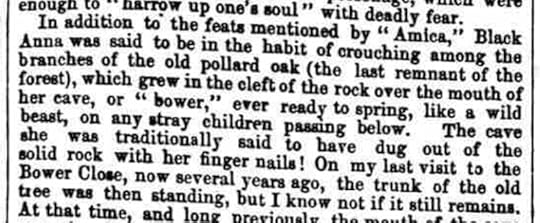

From the Leicester Chronicle, September 5, 1874, p. 2About a month later, a reply came from someone signed as “F.R.H.S.” The acronym probably stands for Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, and Billson identifies the writer as William Kelly.

From the Leicester Chronicle, October 3, 1874, p. 5

From the Leicester Chronicle, October 3, 1874, p. 5This writer goes on to discuss the cave itself and various theories about the person for whom it’s named. He notes that such conjectures disagree on a specific name — Black Agnes? Black Anna? Black Annis? — contending that the latter surname is “still found amongst us” and likely belongs to the property owner. However, in the November 7, 1874, issue, John Mellor joined the Chronicle conversation to say he had located land deeds from 1764 that name the spot as “Black Anny’s Bower Close.” Of course, these are attempts to pin down a historical person, not a legendary one. Given Heyrick’s use of “Annis,” I think we’re safe going with that name when describing the folkloric figure.

Is the Legend About a Witch or Something Else?Conspicuously absent from all the descriptions of Black Annis above is the word “witch.” Instead, we see terms such as “monster,” “savage woman,” and even “ominous personage.” When did Black Annis become referred to specifically as a witch? The best I can say is: the late 1800s. Billson’s 1895 piece includes a passage attributed to Henrietta Ellis, though it isn’t noted what kind of source it is — a letter maybe? Here, the Dane Hills and, by association, the cave there are linked to Cat Anna, “a witch who lived in the cellars under the castle.” Billson then adds a footnote, explaining that an 1837 play titled Black Anna’s Bower; Or, The Maniac of the Dane Hills portrays the character in the title as similar to Shakespeare’s Three Witches in Macbeth. Unfortunately, copies of the playscript are very rare. WorldCat lists only two: one at the University of Leicester, as might be expected, and the other at Indiana University, which I did not expect. Maybe one day I’ll journey to either of those libraries and see if the play really does have its Black Anna do the witchy things Shakespeare’s famous trio does. For instance, a bit of conjuring at a bubbling cauldron would be nice.

An illustration from

Macbeth: With an Illustration and Remarks by D–G

(Thomas Hails Lacey, 1860). I splashed it with a few extra colors.

An illustration from

Macbeth: With an Illustration and Remarks by D–G

(Thomas Hails Lacey, 1860). I splashed it with a few extra colors.Ever since the 1900s arrived, Black Annis seems to have been routinely dubbed a witch. For instance, a headline from a 1931 issue of the Leicester Evening Mail shouts:

From the Leicester Evening Mail, March 31, 1931, p. 6

From the Leicester Evening Mail, March 31, 1931, p. 6The article recounts the long-lost ritual and lore surrounding “Black Anna, the witch.” Indeed, Waddington says, “Leicester has forgotten all its old tales of the witch, but she was a very real figure to the children of a hundred years ago.” However, if she truly had been forgotten, she would not remain so.

The old legend has found a new voice in websites that continue to refer to Black Annis as a witch. There’s this one, this one, and this one. Odd though it might seem, there’s a hotel in far-flung Victor, Colorado that offers a Black Annis Room, wherein visitors can enjoy some “big witchy vibes.” Pretty impressive for a folktale character from central England much better known for being a cave-dwelling introvert than for being able to fly!

In the minds of many, then, Black Annis has been remembered as being a witch for over a century.

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THE

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THEWHISPERS OF WITCHERY

MAIN PAGE.

April 12, 2023

Vengeance of a Victim: Moll Dyer’s Witch Rock in Maryland

The Hard Artifacts

The Hard ArtifactsUp in Maine, there’s a legend about a woman who — moments before being hanged for witchcraft — cursed the vehement witch hunter, Jonathan Buck. The curse is manifested in the image of a leg that cannot be removed from Buck’s cemetery monument. The history of this is doubtful, of course, but something that looks like a leg is indeed on Buck’s gravestone. It can seen today.

That tale is similar to one down in Maryland, and like the Buck headstone, a very solid artifact remains. However, here, instead of the witch hunter being named, we know who the vengeful victim was: Moll Dyer. The legend is transcribed in an 1892 issue of the Saint Mary’s Beacon, a county newspaper published in Leonardtown. Like many legends, this story is set in a murky period “when witchcraft was more believed in than now” and during “such a Winter as the old times knew.” Some forgotten calamity inspired settlers near Leonardtown to accuse Dyer, a defenseless and impoverished woman, of being witch. A nameless mob of witch hunters rose to exile her by burning down her hut. A few days later, Dyer’s body was found frozen to death. The position of the corpse, however, was remarkable. The writer explains that Dyer had died upright while

kneeling on a stone with one hand resting thereon and the other raised as if in prayer.... The story runs that she offered a prayer to be avenged on her persecutors and that a curse be put upon them and their lands.... [T]he stream by the hut is known to this day as Moll Dyer's Run, and the stone but a short distance away, upon which she knelt, is now pointed out to the curious, bearing upon its face the clear impressions of her knees and hand.The rock is now on display at the Saint Mary’s County Historical Society, and Atlas Obscura has some of the best photographs of it I can find. Personally, I don’t see any marks left by knees or a hand, but we can blame that on erosion or on my not seeing the rock up close.

Trouble Tracking the TranscriberWhen I was researching that Maine legend about Buck’s headstone, I had a pretty easy time tracking an anonymous newspaper article to a reprint of it in a magazine, the latter identifying the author. This time, though, my detective work has fizzled. The first paragraph of the anonymous Saint Mary’s Beacon article is quoted at the end of a footnote in James W. Thomas’s Chronicles of Colonial Maryland (1913) with “J.F. Morgan” named as the author. That’s about as far as I’ve gotten. The initials aren’t much to go on, and Morgan is a common surname. Still, I like to imagine that this is the same person who offered medical services in an earlier issue of the Beacon.

Who knows? Maybe Dr. Morgan transcribed local legends as he waited at Uncle Joe’s for his next patient. As I say, though, this is disappointing detective work. Unfortunately, there’s not a lot to go on in this case — including an absence of old accounts of the legend itself.

Trouble Tracking Other Early Records of the LegendThere’s another legendary witch’s rock with a curse that’s said to be near West Greenwich, Rhode Island. It’s said to be there, but no one really knows where it is. Nonetheless, I found accounts of that legend in sources dated 1885, 1896, and 1904. Maybe I was just very lucky in that case because — other than the article discussed above — I’m not able to find anything comparable regarding the cursed witch’s rock now on public display in Leonardtown.

I had high hopes for Annie Weston Whitney and Caroline Canfield Bullock’s Folk-Lore from Maryland, published in 1925. But there are no references to the Moll Dyer tale, not even in a section titled “Stories of Witchcraft, Devil’s Babies, Etc.” I’ve been thwarted (cursed?) when looking for pre-1925 records of the legend on Google Books, Chronicling America, Hathitrust, and other helpful digital archives.

Yet if you do an Internet search for “Moll Dyer” or “Leonardtown witch,” you’ll find all kinds of information about the legend, including some interesting attempts to uncover historical information about Dyer herself. (I can recommend this site, for instance. ) I’d suspect this legend was a fairly recent invention — if not for that 1892 article in the Beacon. A part of the legend noted on the Web is how touching the rock is rumored to affect one’s health, for better or worse. That significant detail isn’t mentioned in the Beacon article. Maybe that’s the real value of locating old transcriptions of legends. While confirming that a particular legend has been around for, say, over a century, such records also suggest how such legends evolve across time.

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THE

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THEWHISPERS OF WITCHERY

MAIN PAGE.

April 9, 2023

Vasilisa, Baba Yaga, and a Whole Lot of Work

Vasilisa the Famous

Vasilisa the FamousMy research leads me to suspect that “Vasilisa the Beautiful” is a likely candidate for Best Known Tale Featuring Baba Yaga. If so, we have Alexander Afanasyev to thank. In the 1850s and 1860s, he meticulously collected and transcribed Russian folktales, and the one about Vasilisa’s attempt to fetch a flame from Baba Yaga, the dreaded witch of Slavic lore, appears in a variety of reprints and translations. Even if you can’t read Russian, Ivan Biliban‘s color illustrations in this 1902 edition of the story are well worth a gander, and I reproduce two of them below. If you want to read the story in English, you can choose your translation: W.R.S. Ralston’s in Russian Folk-Tales (1873), Nathan Haskell Dole’s in The Russian Fairy Book (1907), or Leonard A. Magnus’s in Russian Folk-Tales (1916). Since these translators were all working from Afanasyev’s transcription, the results all about the same.

There are some differences in the title and the title character’s name, though. Should we spell it “Vassilisa the Fair” or “Vasilísa the Fair”? Or call her “Vasilisa the Beautful,” “Vasilisa the Brave,” or “Vasilisa the Wise”? I’ve come across all of these, and indeed, the character is all of the above.

One of Ivan Biliban’s depictions of Vasilisa the Fair, Wise, and Brave (with a glimpse of Baba Yaga’s hut that stands on chicken legs)Work, Work, Work

One of Ivan Biliban’s depictions of Vasilisa the Fair, Wise, and Brave (with a glimpse of Baba Yaga’s hut that stands on chicken legs)Work, Work, WorkIt strikes me that calling the story “Vasilisa the Managerial” might draw attention to one of its key themes, since demands on the title character to work (and work and work) keep popping up. I’ll follow Ralston’s translation to explain how Vasilisa’s cruel stepmother and stepsisters attempt to ruin her beauty with “every possible sort of toil, in order that she might grow thin from over-work, and be tanned by the sun and the wind.” Yet Vasilisa only grows more attractive because she maintains a good relationship with a certain laborer. You see, when her biological mother died, Vasilisa was bequeathed a magical doll “who would do Vasilisa’s work for her.”

The situation takes a turn when the last bit of fire is extinguished in Vasilisa’s house. Apparently, there weren’t any matches or a flint or two sticks, so those nasty stepsisters send Vasilisa to fetch some fire from the horrible Baba Yaga. Even here, the witch stipulates that the young woman work for it. “But if you won’t work, I’ll eat you!” threatens Baba Yaga. As one might expect, the sinister keeper of the flame tries to get the better end of the bargain by giving Vasilisa an exhausting list of chores. That worker-doll comes in handy once again, doing most of the labor. This permits Vasilisa to keep up with the demanding tasks, much to Baba Yaga’s surprise. Much to her disappointment, too, since she was hoping to eat her guest.

Eventually, Baba Yaga feels compelled to ask: “How is it you manage to do the work I set you to do?” Manage is right! Vasilisa slyly answers: “My mother’s blessing assists me.” Well, the witch is uncomfortable around blessings, and she gives Vasilisa her fire — in the form of a skull with flaming eyes! — and rushes her out the door. The young woman returns home, where Folktale Justice jumps onstage and that skull-with-the-flaming-eyes burns the stepsisters and stepmother to crisp. In a sort of epilog, Vasilisa’s talent as a weaver — which again springs from the worker-doll — leads to her marrying the king. Granted, she’s pretty, but her weaving expertise is central to sparking the king’s love. In other words, a person can rise in the world by displaying good occupational skills and good employee relations.

Interestingly, Baba Yaga oversees employees, too, and they have very important jobs. Flip back to when Vasilisa is walking to Baba Yaga’s hut. She spots someone dressed in white, riding a white horse; a red-clad rider on a red horse; and a person with black clothes on yet another color-coordinated steed. When asked about this, Baba Yaga explains that, respectively, these are the Day, the Sun, and the Night. Furthermore, says the witch, “they are all trusty servants of mine.” Baba Yaga, then, might be considered the Time Manager! Of course, this impressive job title depends on whether or not we trust a woman who eats kids and lives in a chicken-legged cottage.

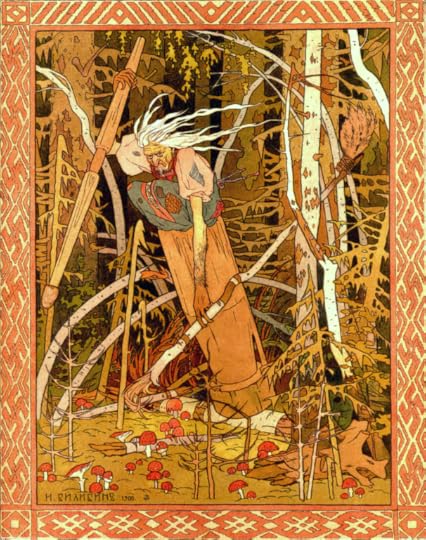

Here is Biliban’s depiction of Baba Yaga riding her pestle-guided mortar. Apparently, this curious vehicle travels close enough to the ground that the witch needs a broom to erase her tracks.Does This Tale Still Resonate Because We, Too, Feel Overworked?

Here is Biliban’s depiction of Baba Yaga riding her pestle-guided mortar. Apparently, this curious vehicle travels close enough to the ground that the witch needs a broom to erase her tracks.Does This Tale Still Resonate Because We, Too, Feel Overworked?While this folktale lends itself nicely to a Marxist or a feminist interpretation, I’ll simply suggest that it resonates with the audience’s experience of work — and, especially, the weariness of being overworked. In the case of the original audience, those poverty-class Russians telling fireside tales in the 1800s, the motivation to work and work and work was probably closely tied to the urge to survive. Speaking as a mainstream American in the 2020s, my own drive to work and work and work — well, I don’t know what it springs from, to be honest. But I’m certainly not alone in feeling that weariness of overwork.

Does this explain why “Vasilisa the Beautiful” (or whatever we should call it) seems to retain more attention than other Baba Yaga tales? On the one hand, such stories dazzle us with images of houses on hen’s leg and skulls with fiery eyes. They offer escape. On the other hand, if they were nothing but escape and entirely detached from our own lives, I wonder if we would have any interest in them at all. Why would certain stories strike a popular chord while others don’t? Phrased differently, is that famous series of novels and movies simply about a kid attending Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry? Or is it about a kid struggling to grow up, like a good many of us are doing or have done? I have a hunch it’s about both.

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THE

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THEWHISPERS OF WITCHERY

MAIN PAGE.

April 5, 2023

The Hopkins Hill Witch Rock: A Rhode Island Mystery

A Bewitched Rock You Can’t (Easily) Visit

A Bewitched Rock You Can’t (Easily) VisitMany a rock has a witch legend attached to it. For instance there’s one in Rochester, Massachusetts; another in Rockbridge, Ohio; and yet another in Carlops, Scotland. A person can locate and visit these rocks pretty easily. However, there’s a bewitched boulder near West Greenwich, Rhode Island, that’s waiting to be discovered. Of course, it might never really have existed it all.

The earliest transcript of the legend I’ve found appears in the June 14, 1885, issue of New York’s The Sun. (It then spread to other newspapers, reaching such spots as Kansas and the Dakota Territory.) The tale recorded there, attributed only to “an aged Rhode Islander,” is fairly detailed. The anonymous storyteller sets the story in roughly the late 1600s, “when settlers had begun to break ground in the neighborhood of Hopkins Hill.” A pesky witch, who lived by a particular rock, was blamed for tools gone missing, cows growing sick, and showers of stones hitting her neighbors’ windows. The witch was even tied to damaging weather because “people saw her flying through the air, driving the storm onward with her broom.”

Finally, the witch was driven away. She was compelled to leave the land around the rock. But she left it cursed. That patch of property could not be plowed or otherwise cultivated, and the storyteller says it remains “enchanted to this day.”

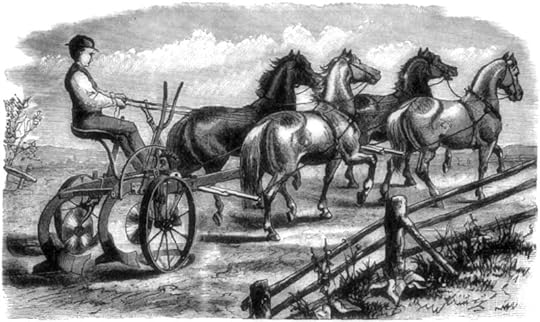

From

The Home and Farm Manual

(1884)Reynolds Attempts to Plow Through the Curse

From

The Home and Farm Manual

(1884)Reynolds Attempts to Plow Through the CurseA man named Reynolds, continues the storyteller, scoffed at the idea of the land being cursed. This skeptic boasted that he could and would successfully plow the land. A crowd formed to witness his attempt. Things started out fine. However, Reynolds’ plow became disabled once he reached the border of bewitchment. He tried again. Again, the curse stopped him. The crowd not only dispersed — it fled!

Besides Reynolds, the only person remaining was the landowner. Together, they witnessed something far stranger than a plow breaking down a couple of times. The storyteller explains, “Reynolds said that, as soon as the people ran away, a crow came from the north.” After cawing a few times,

the crow changed into an old woman with a cocked hat on. She was pursued by the men to the rock, when she turned into a cat and disappeared into its mysterious underground recesses.... After that, the lot was left to grow up to weeds, wild grass, and bushes; the cabin fell to pieces about the enchanted rock, and finally the thick woods that you now see covered the tract, hiding the witch's stone from the world.The reporter ends the article by saying that, these days, the rock is visited only by the occasional hunter or those intrigued by the legend. Is it still there? It would take a determined paranormal investigator to relocate it. I, for one, think it’s worth the archeological effort, though.

Another Transcription — or the Article Summarized?The legend is also included in Charles M. Skinner’s Myths and Legends of Our Own Land, an 1896 collection of American folklore. Unfortunately, this short piece doesn’t add anything new to The Sun’s article and, in fact, looks as if Skinner were drawing directly from that source. On the other hand, a few differences appear when Edgar Mayhew Bacon recounts the legend in his 1904 travelogue/history, Narragansett Bay: Its Historic and Romantic Associations and Picturesque Setting. Here, the witch isn’t run off and Reynolds gives plowing a third try. Perhaps Bacon was chronicling the tale as he had heard it from a different teller. Maybe he was just adding his own touches.

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THE

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THEWHISPERS OF WITCHERY

MAIN PAGE.

March 29, 2023

Meeting Baba Yaga: Two Russian Folktales (Translated into English)

A Fashion for Folktales

A Fashion for FolktalesDuring the latter half of the 1800s, there arose a trend to publish English translations of folktales from various European countries. Those interested in the Grimm Brothers’ German tales could enjoy an 1853 translation (volume 2 is here) or an 1867 one. Granted, these groundbreaking tales had been available in English at least since 1823, but similar collections from other cultures started popping up after mid-century. For example, Popular Tales from the Norse debuted in 1859 and Serbian Folk-lore: Popular Tales in 1874. Those wanting to read Italian Popular Tales in English had to wait until 1885. In the preface to this last volume, translator Thomas Frederick Crane mentions the “growing interest in the popular tales of Europe” among both “the general reader” and “the student of comparative folk-lore.”

Lately, I’ve become a student of folklore about Baba Yaga — sometimes preceded by the or a, and sometimes spelled Baba Jaga — a witchy figure appearing in several Slavic folktales. I’m sad to report that I’m among those whose reading is limited to English, but I managed to find two Russian yarns that were translated and published during the trend mentioned above. Each one is presented as a good introduction for readers not yet afraid of Baba Yaga.

This illustration of Baba Yaga navigating her pestle-controlled mortar (and erasing her tracks with a broom) comes from a 1902 book titled Vasilisa Prekrasnai︠a︡. “Yvashka with the Bear’s Ear”

This illustration of Baba Yaga navigating her pestle-controlled mortar (and erasing her tracks with a broom) comes from a 1902 book titled Vasilisa Prekrasnai︠a︡. “Yvashka with the Bear’s Ear”The first story is titled “Yvashka with the Bear’s Ear.” This was presented by translator George Borrow in “Russian Popular Tales,” a three-installment series that appeared in the magazine Once a Week in 1862. (It appears between “Emelian the Fool” and “The Story of Tim.”) Borrow was respected enough to have a posthumous, multivolume series of his works released, and you might have an easier time reading “Yvashaka with the Bear’s Ear” in this book.

Borrow introduces the piece by explaining that, despite the title, the “main interest” of the story is Baba Yaga, “the grand mythological demon of the Russians….” I’m especially interested in how Borrow describes Baba Yaga’s cabin: it “has neither door nor window, and stands upon the wildest part of the steppe, upon hen’s feet, and is continually turning around.” This bipedal hut is a sign that we’re dealing with the Baba Yaga, not just some sinister substitute.

The story itself is, in a word, nutty. Yvashka was born with a bear’s ear, an indication that he’s got a wild side. He doesn’t play nicely with other children — tearing off their hands and tearing off their heads — so Yvashka’s father put his son in time-out. Permanent time-out. As in get-out-of-my-house-and-don’t-come-back.

Maybe this is exactly what the bear-eared lad needed. On his subsequent journey, he makes three friends, one being a fellow with a moustache long enough to use for fishing. Next, the four pals come upon a cabin that’s rotating on hen’s feet. They stop the cabin from rotating and enter it, a process left murky if, indeed, Baba Yaga’s cottage has no doors or windows. But why quibble?

Yeah, it’s Baba Yaga’s place, and when she returns, she beats up Yvashka’s friends one by one. Now, just because a guy has a bear’s ear doesn’t mean he’s of very little brain. Yvashka somehow knows how to deal with Baba Yaga, laying a trap that’s just as crazy as the rest of the story. Nonetheless, she escapes. The four friends track her to an abyss where she keeps her three daughters working against their wills. Well, Yvashka descends into the abyss and frees the three daughters, but due to a mix-up, the three friends leave him down there.

When Yvashka finally finds his way out, he hunts down his buddies. Turns out that, shortly after abandoning their bear-eared friend, they married the three daughters. As you do, Yvashka kills the guy with the impressive moustache and takes his wife. The end. You’ll note Baba Yaga ingeniously vanishes from both the abyss and the story, presumably to be available for folktales to follow.

George Borrow (1803-1881), taken from Edward Thomas’s

George Borrow: The Man and His Books

“The Baba Yaga”

George Borrow (1803-1881), taken from Edward Thomas’s

George Borrow: The Man and His Books

“The Baba Yaga”Compared to “Yvashka with the Bear Ear,” the next tale is almost sensible. It was translated by William Ralston Shedden-Ralston and is included in his 1873 Russian Folk-tales. As Borrow did, Ralston gives a nice introduction to Baba Yaga before the tale, mentioning her rotating hut “on fowl’s legs.” He also mentions a couple of features I’ve come across in my preliminary research: a fence made of human bones surrounding the hut and a witch-sized mortar that Baba Yaga uses to get around in a hurry. This mortar requires a pestle to guide it. I’m still trying to picture how this works. Like a gondola or a canoe? Is the pestle a ski pole or a stick shift? Maybe the propulsion system of this magic vehicle is left up to individual imaginations.

This tale has a familiar opening. A daughter has a step-mother who mistreats her. One day, the step-mother tells the unnamed daughter to fetch a needle and thread from her step-aunt. “Now that aunt was a Baba Yaga,” says the narrator, suggesting a label applicable to any number of unpleasant women rather than one specific character. The daughter, wary of her step-mother, first visits “a real aunt of hers” for advice. This kind aunt provides a series of instructions regarding a tree branch, squeaky doors, dogs, and a bacon-loving cat. How the kind aunt has this knowledge isn’t explained, but it turns out to be very good advice indeed.

The daughter arrives at Baba Yaga’s hut and explains her task. The witch privately tells a servant to prepare a bath for the girl because one likes one’s food to be to washed. Sensing danger, the daughter immediately plans her escape, exchanging gifts for favors from the servant, the cat, the dogs, and likewise ensuring that the doors and the tree branch won’t stop her along the way. When Baba Yaga learns the girl has vamoosed, she asks the dogs, the doors, and the tree for assistance in catching her. However, they remind the witch that she’s never treated them nicely, so she can forget about any reciprocity.

Short story shorter, the daughter escapes and — as with “Yvashaka with the Bear’s Ear” — Baba Yaga shrugs and quietly exits the stage. When the father hears about his daughter’s adventure, as you do, “he became wroth with his wife, and shot her.” Apparently, in Babayagaville, marriages end as abruptly as the folktales in which they appear. Unlike the other tale, though, there’s a lesson here mixed in with the entertainment: be kind and you’re less likely to be eaten.

This illustration accompanies a variation on the tale discussed above. Titled “Baba Yaga and the Little Girl with the Kind Heart,” it’s in A Staircase of Stories, a 1920 compilation by Louey Chisholm and Amy Steedman. (The tale itself is taken from Arthur Ransome’s

Old Peter’s Russian Tales

.) Curiously, the advice-giving aunt is replaced by a mouse and, instead of the father shooting the step-mother, he simply gives her the boot.

This illustration accompanies a variation on the tale discussed above. Titled “Baba Yaga and the Little Girl with the Kind Heart,” it’s in A Staircase of Stories, a 1920 compilation by Louey Chisholm and Amy Steedman. (The tale itself is taken from Arthur Ransome’s

Old Peter’s Russian Tales

.) Curiously, the advice-giving aunt is replaced by a mouse and, instead of the father shooting the step-mother, he simply gives her the boot. Ralston includes other tales about Baba Yaga in his collection, and other sources include even more. In the coming weeks, I hope to read and report on those I can find, eventually creating a single page listing them and providing links to English translations. This will be part of a new project I’m calling Whispers of Witchery: Exploring Written Records of Witch and Witch Hunter Folktales. Stay tuned. Would it be too cringeworthy if I said you just might find it bewitching?