Tim Prasil's Blog, page 12

March 22, 2023

The Lingering Leg: A Witch Legend in Bucksport, Maine

An etiological myth is one designed to explain how something came to be. Where does lightning come from? Zeus. Why don’t snakes have legs? God’s punishment for its deceptions and harmfulness. What accounts for the Great Lakes? Paul Bunyan dug them, of course, because his logger buddies were thirsty. Structurally, these are a bit like a detective story: 1) there’s an observable thing, be it a lightning bolt, a slithery snake, a Great Lake, or a dead body; 2) construct a narrative — believable or otherwise — that leads up to and accounts for that thing.

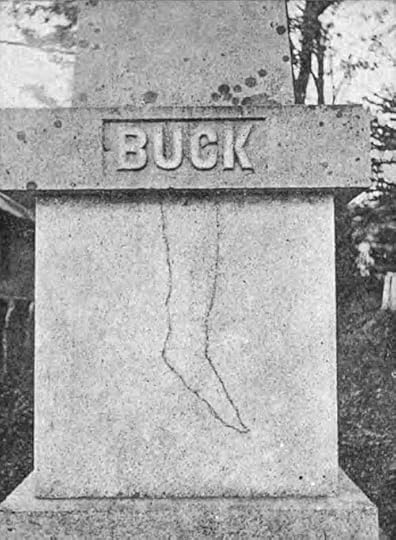

This is pretty clearly what happened in the case of a witch legend centered in Bucksport, Maine. There’s a headstone there for the town’s founder, Colonel Jonathan Buck, and his family. On the back of that monument is an image that’s permanently embedded in the granite. One source describes it as looking like “a woman’s stocking-clad foot, or maybe a boot.” That might be a touch too specific. It’s a pretty sketchy outline.

A photograph, possibly enhanced to better show the leg, from James O. Whittemore’s “The Witch’s Curse,” an important chronicle of the legend.

A photograph, possibly enhanced to better show the leg, from James O. Whittemore’s “The Witch’s Curse,” an important chronicle of the legend.But how to account for this odd image? Well, from 1898 to 1899, an article attributed to the Philadelphia Inquirer was reprinted in newspapers from New Jersey to Kansas and from the Dakota Territory to New Mexico. This same article was republished in the September, 1902, issue of The New England Magazine with John O. Whittemore identified as the author. It’s probably one of the best print records of the legend passed down orally by Bucksport residents.

The History of Colonel BuckBefore getting to that legend, let’s look at the actual history of the man buried below the headstone. Jonathan Buck (1719-1795) was born in Massachusetts and became an officer in the American Revolutionary War. According to a history written by the Bucksport’s Bicentennial Committee, Buck had begun the work of developing what had been designated “Planation 1” in Maine prior to the war, but afterward, the area was named for him: first, Buckstown and then Bucksport. In another document written for the bicentennial celebration, Valerie Van Winkle writes:

Buck might have remained a traditional local hero, but in August of 1852, his grandchildren erected a monument near his grave site. As the monument weathered, an image in the form of a woman’s leg and foot appeared under the Buck name.In the wake of this appearance, the legend rose, becoming a tantalizing tale in Bucksport’s local lore. Whittemore’s 1898 Inquirer article, Van Winkle implies, was the first record of it in print.

The Legend of the Lingering LegIn summary, Whittemore’s version of the legend goes like this: Buck “was most Puritanical, and to him, witchcraft was the incarnation of blasphemy.” At some undated time, Buck use his civil authority to order that a woman accused of witchcraft be imprisoned, swiftly tried, and executed for that crime. The woman — probably innocent but, at least, illegally condemned — stood on the gallows and cast a curse on Buck:

"You will soon die. Over your grave they will erect a stone.... Listen all ye people -- tell it to your children and your children's children -- upon that stone will appear the imprint of my foot, and for all time long, long after your accursed race has perished from the earth, the people will come far and near, and the unborn generations will say, 'There lies the man who murdered a woman.'"This curse, according to Whittmore, was remembered once the granite monument was put in place and the apparition of the appendage came into sight. Sure enough, it drew in spectators “from miles around to gaze and wonder.”

In other words, it became a tourist attraction. And it remains one today.

This detail of an 1875 map of Bucksport shows the location of the cemetery. The site can still be visited today, and it’s still at the corner of Main and Hinks Streets.Problems with Reconciliation and Such Like

This detail of an 1875 map of Bucksport shows the location of the cemetery. The site can still be visited today, and it’s still at the corner of Main and Hinks Streets.Problems with Reconciliation and Such LikeUnfortunately, the history and legend don’t match. Even Whittmore notes that some people will “pooh-pooh the legend and call attention to the historical discrepancy between the date of the witchcraft era and the régime of Colonel Buck.” I’ll put myself among those pooh-poohers. The belief in witchcraft as tied to Satanic allegiance, which is how the Puritans understood it, died out surprisingly quickly after the late 1600s. (Remember that the Salem witch trials occurred in 1692-93, and the charge of was already controversial then.) Buck, born in the early 1700s, would have been raised with a very different mindset, one shaped by Enlightenment-era movements such as deism and scientific skepticism. If the adult Buck had ordered the execution of a woman for practicing witchcraft, he would have been promptly removed from any position of authority amid astonishment and snickers.

There’s also the problem with marking a murder with a rough outline of a leg. That’s just lazy legend-ing. A heart? Sure. An eye? Ooo, that would be cool! A raised middle finger would be awesome! But a leg? Van Winkle’s article cites versions of the legend written after Whittmore’s, and while these better account for the vengeful leg, they also push the legend into the realm of outright fiction.

There’s also the issue of the legend fitting a formula. Nathaniel Hawthorne, who knew quite a lot about turning legends into fiction, opens The House of the Seven Gables (1851) with a similar story of Matthew Maule being falsely accused of witchcraft by Colonel Pyncheon. Prefiguring the curse hurled at Colonel Buck, Hawthorne writes:

At the moment of execution—with the halter about his neck, and while Colonel Pyncheon sat on horseback, grimly gazing at the scene Maule had addressed him from the scaffold, and uttered a prophecy, of which history, as well as fireside tradition, has preserved the very words. 'God,' said the dying man, pointing his finger, with a ghastly look, at the undismayed countenance of his enemy,—'God will give him blood to drink!'Moll Dyer is featured in a similar legend about a Maryland woman driven from her home by witch-hunting zealots. She extracted her revenge in the form of a rock forever marked by her hand. Touching this rock, it is said, will bring misfortune. I suspect there are additional tales that follow the pattern, too.

So We’re Left to Ask…Why, then, do such witchy legends appear and appeal, persist and propagate? This is endlessly debatable, I suppose, but I’ll try to spark that debate with some ideas. At first, the victim-turned-vengeful-villain might seem like a contradiction. The one unfairly accused of witchcraft is revealed to have supernatural power. Maybe that power isn’t gained through a deal with the Devil, though. Maybe it comes from a higher source of justice, since it punishes the guilty. We seem to like such stories. For instance, most detective stories do the same, even though the Hand of God stuff usually goes unstated.

Come to think of it, stories in which the guilty wind up punished fill bookshelves everywhere. So let’s ask: why witches? Are these legends meant to remind those living from the 1700s onward of the dangers of clinging to old superstitions — while not abandoning the idea of Divine Justice? Do the tales represent lingering guilt over the victimization of those accused of witchcraft and, perhaps by association, any and all other groups preyed upon by a fearful and more powerful opposition?

Debatable. Luckily, none of this deep analysis has the power to destroy the pure entertainment of a kooky story about a headstone with something that looks vaguely like a leg on it. Legends are fun, and the one about the unnamed and ill-treated woman who kicked Colonel Buck where it counts is, too.

March 12, 2023

Two Acts and a Couple of Witches

I’m writing a two-act play. Each act is two scenes long, and I only have the final scene left to write. That’s mapped out pretty well, so it looks like this will be the first full-length play I’ll actually complete. I started one long ago, but never finished it, and I’ve finished several short plays for the stage and for audio. (If you’re interested, I list them and offer some of the scripts at the bottom of my writing résumé in the About section.)

I suspect many writers wind up with at least a slightly different story than what they sat down to write. It’s part of the process and part of the fun. For instance, I hadn’t fully realized that my play was, at its heart, a tale of witchcraft. In fact, two legendary witches are named. The first one is Moll Dyer, whose legend is told here. This tale presents her as a vengeful victim of a witch hunt rather than a practicing witch. Dyer is accused of witchcraft, she’s driven out of her house on a bitter cold night, and she freezes to death. However, her handprint is found pressed into a rock, and that rock is said to curse anyone who touches it. There’s an older telling of the legend here, one which becomes a ghost story. In regard to this witch-and-ghost-legend blend, Maryland’s Moll Dyer has some basic similarities to Tennessee’s Bell Witch, the latter legend being something I wove into one of my Vera Van Slyke novels.

From Chapter X of

A Famous History of the Lancaster Witches

(1780)

From Chapter X of

A Famous History of the Lancaster Witches

(1780)Moll Dyer and her cursed rock play only a minor part in my play. Baba Yaga is revealed in the end to have had a more central role in all that happens. This figure from Slavic folklore is complicated and contradictory. At times, Baba Yaga is terrible, but other times, she’s helpful. She might guide you through the woods — or eat you. Moody, in other words. This ambiguity works nicely with the story I’m dramatizing: a group traveling through rural Wisconsin gets hit by a blizzard. They find refuge in an old farmhouse whose previous owner had a notorious reputation — think Ed Gein. The guests come to discover they’re trapped. This is supposed to sound like a familiar premise — something in the “old dark house” vein — but I think I put a pretty good twist on it.

Oh, did I mention it’s a comedy?

I’m now fascinated — dare I say bewitched? — by Baba Yaga. I want to learn more about how she appears in various forms in various folktales. Though not exactly promised, it’s quite possible that I’ll share what I find here. And if I stumble across any other witchy legends, such as the one about Moll Dyer, I’ll probably share them, too. In other words, BromBonesBooks.com is now home to ghosts and witches.

— Tim

February 26, 2023

My Mother’s Side, Part 3: The Andrews Family of Carmarthen

Go To “MY Mother’s Side, Part 2”Like Trying to Find a Kelly in Dublin

Genealogy research, I’ve learned, is very hit-or-miss. My mother’s father’s mother was a Kelly, born in Chicago. Tracking down one particular Kelly in Chicago is like looking for one particular piece of hay in a haystack. I’d rather look for the needle. On the other hand, my mother’s mother’s mother was an Andrews — another common surname — but, for some reason, I’ve discovered quite a lot about them, especially those who remained in Carmarthen, Wales.

Here, then, is what I’ve been able to piece together about my ancestors who made candy and raced bicycles in the 1800s and early 1900s.

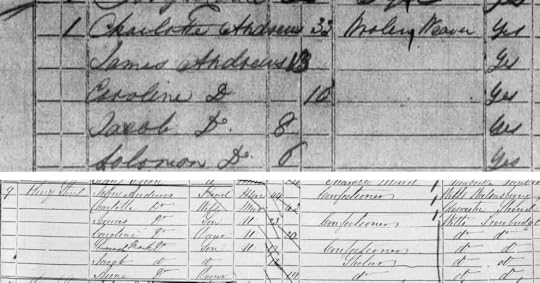

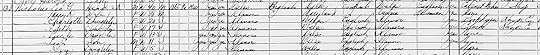

Jacob Andrews ArrivesMy great-great-grandfather, Jacob Andrews, appears as an 8-year-old on the 1841 census for Trowbridge, Wiltshire, England. That “yes” on the right of the first document below means he was born in the same country. However, by 1851, the Andrews family had moved to 9 King Street in Carmarthen, Wales, and the father and his oldest sons were confectioners. (Confectioners, you might already know, make candy and other treats that are irresistible and probably bad for you.)

The 1841 and 1851 UK census shows that the Andrews had moved from Trowbridge to Carmarthen.

The 1841 and 1851 UK census shows that the Andrews had moved from Trowbridge to Carmarthen.Sure enough, Jacob would join the same profession, as shown on his 1853 marriage certificate. His bride’s name was Lucy Ann Moseley, and she also lived on King Street. The 1871 census shows Jacob still in the sweets business, but the couple are living a bit further down King Street with their four children. (One of those kids is Ida Mary, my great-grandmother. She’ll marry John Nicolas and they’ll emigrate to Chicago, something I discuss in Part 1 of this little series.)

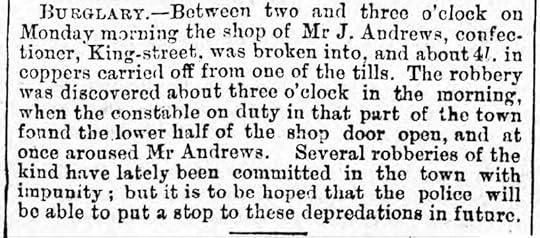

The 1870s; Or, Who Robs a Confectionary?Let me rephrase that: who robs a confectionary for money?

From The Aberystwith Observer (5th June 1875, p. 4)

From The Aberystwith Observer (5th June 1875, p. 4)A far greater loss had come the previous year. Lucy Ann Andrews died on September 16, 1874. Jacob remarried, and the 1881 census lists his wife as Margaret from Carmarthen. But Margaret died on January 2, 1889. It follows that no wife is indicated in the 1891 census. Nonetheless, in 1901 and 1911, Jacob’s wife is identified as Susan. Though the typical reasons behind for doing so might be different today, marrying three times was also a part of Victorian and Edwardian life.

To illustrate a very different part of Victorian and Edwardian life, let me now shift the spotlight to Jacob and Margaret’s son, Bertie.

Bertie Andrews: Successful Local Cyclist From The Carmarthen Journal and South Wales Weekly Advertiser (12th July 1901, p. 4)

From The Carmarthen Journal and South Wales Weekly Advertiser (12th July 1901, p. 4)The Carmarthen newspapers that figured readers would want to know about Bertie’s fall from a bicycle also kept tabs on his accomplishments as a racer. For instance, the Journal announced his being chosen to ride for Wales against the London Polytechnic Club (9th May 1902, p. 5) while the Weekly Reporter explained that, at a benefit held by area athletes for one of their own, Bertie was considered to be “the best cyclist on the ground that day” (18th July 1902, p. 2).

I imagine that even a champion bicycle racer needs a side gig to pay the bills. It makes sense to start with a bike shop. And that’s what Bertie did in 1903, selling the brand of bike ridden by a king!

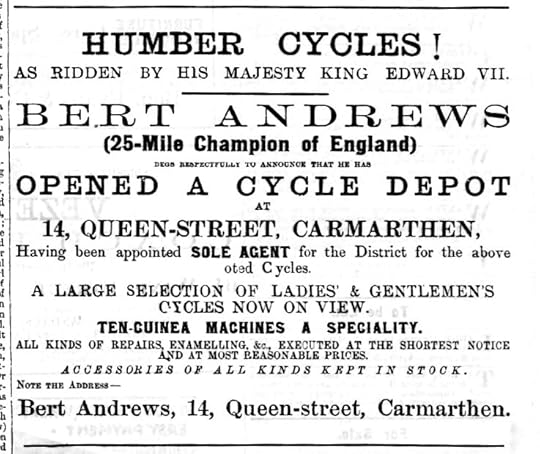

An ad for Bert Andrews’ “cycle depot” from The Carmarthen Journal and South Wales Weekly Advertiser (27th March 1903, p. 3)

An ad for Bert Andrews’ “cycle depot” from The Carmarthen Journal and South Wales Weekly Advertiser (27th March 1903, p. 3)In 1910, he retired from cycling. Here’s the only picture I’ve managed to find of the famous athlete.

From the Evening Express (7th April 1910, p. 4)

From the Evening Express (7th April 1910, p. 4)Maybe Bert had grown tired of the sport or was looking to settle into something less physically demanding. Whatever his reason, within a few years, he had become the proprietor of the Spread Eagle Hotel on Queen Street, an establishment that still exists today. Should I swing by, I think I’m owed a complimentary beer.

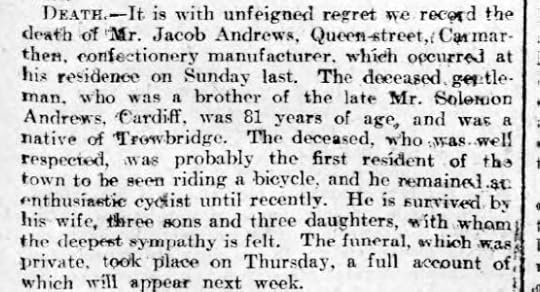

Jacob Was Remembered for Cycling, TooApparently, cycling mattered to both Jacob and Bertie. When the father was memorialized in 1914, it was noted that he had been among the earliest bicyclists in the area. Maybe Bertie got the itch from his dad.

From The Carmarthen Journal and South Wales Weekly Advertiser (17th April 1914, p. 5)

From The Carmarthen Journal and South Wales Weekly Advertiser (17th April 1914, p. 5)That Solomon Andrews mentioned in the obituary was a pretty big deal in a variety of businesses across Wales, from local bus services to real estate development. He’s worthy of a post of his own, but I’m going to leave that to someone else.

If you’ve bothered to read through this little series of piecemeal tales about my ancestors, I sincerely thank you. I stitched together these various documents more for me than for anyone else. Still, there’s a chance — however slight — that I’ve inspired a few folks to look into their own genealogy. I’d love to hear about other people’s adventures in ancestry below.

— Tim

February 19, 2023

My Mother’s Side, Part 2: Tragedy Comes to the Nicholas Family

Last week, I took documents gathered while researching my genealogy and organized them to help me form a narrative. I discussed how my great-grandmother, Ida Mary Nicholas, née Andrews, and her husband, John, left Carmarthen, Wales, in the early 1880s to start a new life in Chicago, USA. In the process of telling this story, I learned some things about American history and new details about my ancestors.

This week, I’ll pick up where I left off, discussing a series of deaths in the Nicholas family that occurred within just a few years. John, my great-grandfather, outlived his wife and two of his children, and I wonder if he ever regretted having left Wales.

The Death of John’s Wife (or Ex-wife?) in 1926By 1920, apparently Ida Mary and John had separated. Maybe they had divorced. The census of that year shows my great-grandmother as “Head” of the family, living on Monroe Street. She’s still marked as married, but the entry for John — living with their son, Leo, on Madison Street — says he’s divorced. Their daughter/my grandmother resided with her mother. She was also named Ida Mary, but I’ll just call her Ida for clarity.

The 1920 census shows Ida Mary as head of the family.

The 1920 census shows Ida Mary as head of the family.Of course, I don’t know much at all about this parting of the ways. The usual documents are silent on that part of story. One thing I do know is that the John and Ida Mary are buried side-by-side, which suggests the break-up wasn’t too ugly. I hope…

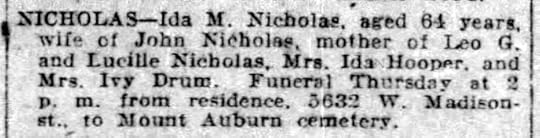

Ida Mary died first. It was in 1926, and by then, Ida, her namesake, had married a man named Hooper.

My great-grandmother’s obituary notice appeared in the Chicago Tribune (September 1, 1926, p. 36). Back in Carmarthen, her life seemed not to stray too far from King Street, something I discuss in Part 1. In Chicago, Madison Street was where she had lived early on and, according to this notice, where she resided when she died. The Violent Death of John’s Son in 1932

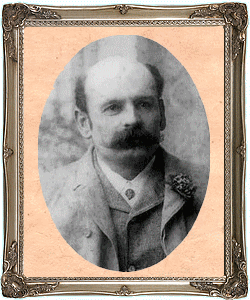

My great-grandmother’s obituary notice appeared in the Chicago Tribune (September 1, 1926, p. 36). Back in Carmarthen, her life seemed not to stray too far from King Street, something I discuss in Part 1. In Chicago, Madison Street was where she had lived early on and, according to this notice, where she resided when she died. The Violent Death of John’s Son in 1932Ida Mary and John’s first born was Leo George, their only child born in Wales. As discussed last week, he was born in or around 1880, and by 1900, he was married and working alongside his father at a Chicago grille works company. (Grilles are ornate panels or screens often made of wood.) By 1918, though, he had taken a job as a guard in the Cook County penal system, as shown on his WWI registration card of that year. This might have been a part-time job because the 1920 census says he worked as a cabinet maker, still a woodworker and, I suspect, still making grilles. This latter document also shows that he, his wife, four daughters, and one son were living on Madison Street, further west from where the 1900 census shows him. In other words, he had moved to a house up the street to accommodate his growing family.

The 1920 census suggests Leo George, Ida Mary and John’s first born, had adapted well to Chicago. Below his children (though unseen here) are a number of lodgers — not unusual in the early 20th century — the last of which is Leo’s father, marked as divorced.

The 1920 census suggests Leo George, Ida Mary and John’s first born, had adapted well to Chicago. Below his children (though unseen here) are a number of lodgers — not unusual in the early 20th century — the last of which is Leo’s father, marked as divorced.Leo was still a jail guard in 1932. This is the year that Jack Lawrence was an inmate being held for trial on the charge of murdering a police officer. Lawrence had gotten into a fight with another prisoner, and Leo was assigned to accompany him to the doctor’s office. But, somehow, Lawrence had managed to get a gun into the secured facility. He shot Leo three times and then went on a rampage, running from one floor to another. He threatened two other guards, demanding to be set free from the jail. These guards both avoided being shot. Soon, “dozens of guards armed with rifles and tear bombs were posted at vantage exits,” according to the Chicago Daily Tribune. That’s when Lawrence turned the gun on himself and committed suicide.

The shooting death of Leo Nicholas, my granduncle, was covered on the front page of the Chicago Daily Tribune (June 23, 1932). In the same issue, the picture above appeared beside one of murderer Jack Lawrence (p. 9). It’s the only picture I have of any member of the Nicholas family.

The shooting death of Leo Nicholas, my granduncle, was covered on the front page of the Chicago Daily Tribune (June 23, 1932). In the same issue, the picture above appeared beside one of murderer Jack Lawrence (p. 9). It’s the only picture I have of any member of the Nicholas family.The news of Leo Nicholas’s violent death was reported in newspapers as far away from Chicago as Connecticut and Nevada.

The Deaths of John’s Daughter and John Himself in 1933 My grandmother’s obituary notice appeared in the Chicago Tribune (January 27, 1933, p. 16).

My grandmother’s obituary notice appeared in the Chicago Tribune (January 27, 1933, p. 16).My maternal grandmother died when she was in her 30s. Unlike her brother’s, Ida’s death didn’t make the front page. I don’t know what caused her death. Beyond the fact that she once was, I don’t remember her being discussed in my family. Not by my mother, who would have been only four-years-old when her mother died. Not by my grandfather, who outlived Ida by six decades (without ever remarrying). I don’t remember our ever visiting her grave, and not until I plunged into genealogy research did I learn that she’s buried with her parents rather than with her husband. It makes sense that she would be, I guess. Ida didn’t live long, but she had lived longer as a daughter than as a wife and mother.

Ida Hooper, née Nicholas, remains a mystery to me, her grandson. However, I think more about how her father must have suffered. In the wake of splitting with his wife, she, their son, and their daughter all died in the span of seven years. Did the weight of all this contribute to John’s own death, which occurred just a few months after Ida’s?

My great-grandfather’s obituary notice appeared in the Chicago Tribune (May 23, 1933, p. 16).

My great-grandfather’s obituary notice appeared in the Chicago Tribune (May 23, 1933, p. 16).John was survived by two daughters, as his obituary notice says, and the 70-something man had probably played with several of his grandchildren, too. Ninety years later after his death, a great-grandson named Tim would use his blog to try to tell something about this man’s Welsh origin, his immigrant experience, and his American sorrows.

Once upon a time, Ida Mary Andrews married John Nicholas, and together, they journeyed to Chicago. I know some interesting things about a few of the relatives they left behind in Wales. Next week, I’ll jump back in time — and back across the ocean — to talk about the Andrews family. I promise that post will be more upbeat than this one. After all, the Andrews combined candy-making with bicycle-riding!

— Tim

February 12, 2023

My Mother’s Side, Part 1: The Nicholas Family in Carmarthen and Chicago

I’ve been tracing my genealogy for several years now. At first, I focused on my father’s side. I did fine with mapping the descendants of my great-grandparents, the ones who immigrated to Chicago from what was then called Bohemia (and is now called the Czech Republic or Czechia). However, going back further — back to Europe — proved difficult because my grasp of the Czech language goes only slightly beyond ordering a beer.

Then I switched to my mother’s side. Now, we’re dealing with folks from the UK and Ireland! Even though their records are mostly in English, I’ve still struggled with those on the other side of the Atlantic. There are some exceptions. For example, I’ve uncovered a few things about the Nicholas family from Carmarthen, Wales. As I’ve learned bits and pieces about this family, the storyteller in me has felt an urge to recount their lives. This, then, is where I’ll begin a short series of posts about the maternal line of my ancestry.

A King Street Romance — and Trouble with the NumbersAccording to the 1871 census, a 12-yearold girl named Ida Mary Andrews lived at 56 King Street in Carmarthen, Wales. Ida Mary’s father, Jacob, was a confectioner from Trowbridge, England. I’ll share my discoveries about the Andrews family in Part 3 of this blog series. For now, let’s stick with Ida Mary and a boy up the street — the man she would marry — John Nicholas.

The Andrews family, including Ida Mary, lived at 56 King Street, according to the 1871 UK census.

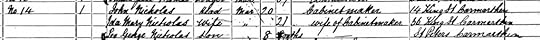

The Andrews family, including Ida Mary, lived at 56 King Street, according to the 1871 UK census.Ida Mary and John had been married by the time the 1881 census was taken. This time, folks appear with their current locations along with the ones where they were born. While it looks like it says Ida Mary Nicholas had been born at 36, not 56, King Street, I put my trust in the census of the previous decade, since it’s followed by “55 King Street” and then “54 King Street.” It also says John Nicholas was born at 14 King Street, just up the way.

The 1881 UK census shows that John had been born at 14 King Street, Carmarthen.

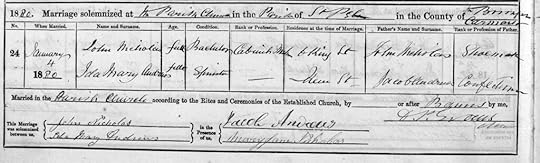

The 1881 UK census shows that John had been born at 14 King Street, Carmarthen.Regardless of street numbers, Ida Mary and John met each other, one might presume crossing paths somewhere along King Street. Had it been at the candy shop of Ida Mary’s father? Who knows? What we can say is they were married at St. Peter’s Church, which is an easy walk away. The happy event was on January 4, 1880.

The marriage certificate of John and Ida Mary. Here, we see that John was a cabinet maker, and the Andrews had since moved to Queen Street (specifically 15 Queen Street, according to their entry on the 1881 census). A Baby — and Trouble with the Numbers

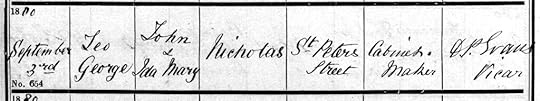

The marriage certificate of John and Ida Mary. Here, we see that John was a cabinet maker, and the Andrews had since moved to Queen Street (specifically 15 Queen Street, according to their entry on the 1881 census). A Baby — and Trouble with the NumbersJohn and Ida Mary’s first born was named Leo George. I wasn’t able to find a birth certificate to confirm the date, but his baptism record is dated September 3, 1880. That’s almost exactly nine months after the wedding day. Let’s just say John and Ida Mary wasted no time starting their family.

Leo George’s baptism record is dated September 3rd, 1880. Can we safely say he was born in, oh, July or August, 1880?

Leo George’s baptism record is dated September 3rd, 1880. Can we safely say he was born in, oh, July or August, 1880?Or should we say that? This genealogy stuff often raises sticky questions, such as why Leo George’s 1918 World War I registration card puts his birthdate at July 18, 1879. This would be about a half a year before his parents got married and well over a year before he was baptized. Is there a family scandal here, or was Leo adding a year to his age when enlisting? I could understand why he might claim to be a year older if that was needed to pursue a teenager’s dreams of being a soldier. But, no, he was in his late 30s.

Document E: Leo’s WWI registration card says he was born in 1879, not 1880. Hmmmm.

Document E: Leo’s WWI registration card says he was born in 1879, not 1880. Hmmmm.Here’s something I didn’t know before working on this post. Though there were plenty of Americans who volunteered to fight in WWI, the War Department still recommended a draft. According to the U.S. Army website, “The Selective Service Act passed on May 18, 1917, and all men age 21 to 30 were required to register with local draft boards. As the war continued, the age for registration went up to 45.” Was Leo claiming to be a year older with the hope of making himself a less desirable draftee? I’d be surprised by this because, at the bottom of that card, his occupation is given, and Leo was working as a guard for the Cook County Sheriff’s Office. Something tells me that a man brave enough to serve as a prison guard in Chicago wouldn’t try to sidestep military service.

I’m going assume that Leo was born in the summer of 1880, as suggested by his baptism record. The 1881 census lends support to this, too, since it puts him at “8 months” that year.

From Carmarthen to ChicagoThe same census also puts little Leo and his parents at 14 St. Peter’s Street in 1881. The distance between King and St. Peter’s Streets isn’t much at all. However, in 1882, John, Ida Mary, and Leo journeyed from Carmarthen, Carmarthenshire, Wales, all the way to Chicago, Illinois, USA. Eighteen years later, the US census reveals that the family had grown by three daughters and one daughter-in-law. They lived on West Madison Street.

The 1900 US census indicates that Ida Mary, John, and Leo immigrated to Chicago in 1882. Along with a quartet of daughters, Ida Mary and John have a granddaughter named Lottie.

The 1900 US census indicates that Ida Mary, John, and Leo immigrated to Chicago in 1882. Along with a quartet of daughters, Ida Mary and John have a granddaughter named Lottie.See that third daughter, the one named Ida M.? That’s my grandmother!

Kindly also note that May Nicholas, Leo’s wife, is the daughter of a man born in Maryland and a mother born in Bohemia! The Welsh and the Czechs were mixing already! Was it their mutual disdain for the English language’s limitations on vowels? (For instance, nghwm means valley in Welsh and hrst means handful in Czech.) Or was it an understanding born of being subjugated by a neighboring empire, be it British or Habsburg? Or is it just a Chicago melting-pot thing? Maybe all of the above and quite a bit more.

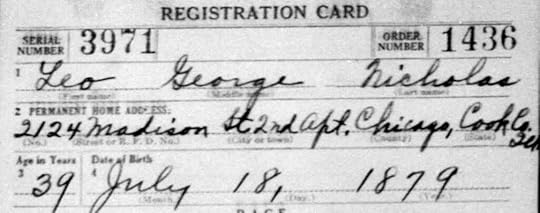

Here’s another interesting — or should I say pretty darned astounding? — discovery I made as I was writing this post. That 1900 census says John and Leo worked in the “grille” business, the father as a manufacturer and the son as a maker. I wanted to find out was a “grille” was. Turns out, it’s a fairly large piece of decorative woodwork that one might use to cover a radiator or frame a window or you name it. While looking for this information, though, one of the first sources I found was a short article titled “20th Century Grille Works,” run in a 1900 issue of The National Builder. Seriously, I grabbed both sides of my head when I read:

There are a number of manufacturers of grille work in Chicago, and prominent among them is Twentieth Century Grille Works, of which Mr. John Nicolas is manager. This establishment is located at No. 853 Madison street.... This enterprise was established by Mr. Nicholas about eight years ago, and he is still manager for this firm. He has been identified with this branch of manufacture for some eighteen years. Mr. Nicholas was born and reared in Wales and came to Chicago eighteen years ago.Until now, I hadn’t known the company name and work address of my Welsh-immigrant ancestor. This has to be him, right? I imagine there have been several men named John Nicholas in Chicago, but this one worked in the grille-manufacture business and immigrated from Wales in 1882. And guess what. The address in the advertisement below is the same as on the 1900 census. (I’m curious if he did this work at home — or if the Nicholases lived in a woodworking shop!) Calling it: that guy in the article is my great-grandfather!

A 1900 advertisement printed in The National Builder, the same Chicago-based journal that ran a short piece about John Nicholas, my great-grandfather. And, yes, I’m sending for that illustrated catalogue!

A 1900 advertisement printed in The National Builder, the same Chicago-based journal that ran a short piece about John Nicholas, my great-grandfather. And, yes, I’m sending for that illustrated catalogue!Let’s review. My great-grandparents lived on the same street in Carmarthen, Wales. I even know the street numbers and could stroll past those spots should I ever visit Wales (and I should). And now I could also stroll past their home/workplace in Chicago (and might have, since I spent a few years in that city).

Sadly, tragedy was looming for the Nicholas family. I’ll post about that next weekend.

— Tim

February 5, 2023

Another (Dispiriting) Ghost Hunt Conducted by James John Hissey

In The Victorian Ghost Hunter’s Casebook, I present travel writer James John Hissey’s charming and sometimes funny chronicle of his investigation of a haunted house in the English village of Halton Holgate. Following leads from newspaper reports, he manages to locate the house. There, he interviews the residents, Mr. and Mrs. Wilson. The wife gives him a tour, showing where she saw the phantom of an old man at the top of the stairs and where she uncovered bones under some bricks. Disappointingly, though, the Wilsons turn down Hissey’s request to conduct nocturnal surveillance, and this leaves the writer lamenting his failure to have ever encountered a ghost.

I recently stumbled across another of Hissey’s ghost hunt chronicles, and this time, his wish to spend the night in a haunted spot is granted! This much shorter narrative appears in The Road and the Inn (1917). Hissey is wandering through Bury St. Edmonds, where an innkeeper claims to have the very knife and fork used by Mr. Pickwick during his stay there. Apparently, the gent was not troubled by the fact that Mr. Pickwick is a fictional character created by Charles Dickens. The general topic of the curious “discoveries one makes on the road, some so surprising that the seasoned traveller ceases to be surprised at them,” then narrows to an anecdote about Hissey being invited to hunt a ghost in an ancient, isolated house. Without giving the location of the site, he explains:

It was supposed to be haunted by the ghost of some long-dead ancestor buried in a private chapel in the grounds. I very faintly hoped that there perchance, if anywhere, I might at last run down a ghost after many years of fruitless ghost hunting. The ghost had excellent credentials. This example of Hissey’s skill as an illustrator comes from The Road and the Inn. The house is Gedding Hall, near Bury St. Edmunds (and presumably not the house in his ghost-hunting anecdote.)

This example of Hissey’s skill as an illustrator comes from The Road and the Inn. The house is Gedding Hall, near Bury St. Edmunds (and presumably not the house in his ghost-hunting anecdote.)All the conditions are right for a spectral encounter: a stormy, winter night; a creaky, old house; a room with a blazing fire; and, as Hissey discovers, a private stairway in the corner, which he says provides “a convenient approach for ghosts.” Sadly — other than a servant coming to check the fire around 4:30 a.m. — our paranormal investigator receives no visitors. He bemoans:

That was my last experience of sleeping in a haunted room; now I am beginning to despair of ever beholding a ghost. Why will they appear to others and never to me?Hissey then relates a few accounts given by some of those others who had crossed paths with ghosts (or so they claimed), including the Wilsons at Halton Holgate. The Road and the Inn was the writer’s last-published book. He died a few years afterward, so it’s probably safe to assume that — if his wish to see a ghost ever came true — it was only after he had passed to the Great Beyond.

Not much has been written about Hissey’s life. We only have some bare facts. There’s a brief biography in Esme Anne Coulbert’s doctoral thesis, “Perspectives on the Road: Narratives of Motoring in Britain 1896-1930.” (Nottingham Trent University, 2013, pp. 43-44). We learn that Hissey was born in Longworth, Oxfordshire. He inherited lucrative property in Chicago from his uncle, and amid efforts to secure that claim, he toured the western states. Upon returning to England as a man of leisure, he began to write his travel books, illustrating them with his impressive drawings and, later, his photographs. The same basic history is told at Goodreads, though it’s anonymous and lacks documentation of sources. There, London is identified as the birthplace and details are added about, for instance, the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. A website dedicated to Britain’s earliest automobiles offers a dash more information along with some great photos of the Hisseys posing in their motor cars. The top photo on this page makes me wonder if Hissey’s formidable moustache (see above) produced any measurable wind resistance during his automobilist adventures.

Allow me a short detour here to say that haunted houses were apparently considered worthwhile destinations for early automobile tourists. This is suggested by an article about such houses published in a 1914 issue of The Autocar. This magazine was billed as “A journal published in the interests of the mechanically propelled road carriage.”

I posted my reading of Hissey’s chronicle about his Halton Holgate investigation, titling it “Another Victorian Ghost Hunt,” on the Tales Told When the Windows Rattle YouTube channel and here on this site. In my opening and closing comments, I admit to having a soft spot for this frustrated ghost hunter. His books reveal that, despite constant disappointment, he doggedly and admirably sought haunted places while out on his journeys. In this respect, I imagine Hissey speaks for a good many Victorian ghost hunters — those investigators who came up empty-handed and, so, never bothered to record their cases.

January 25, 2023

Passing the Ghost Torch: Edwin and Windham Wyndham-Quin

Ghost Hunter Hall of Fame inductee Violet Tweedale explains that she was introduced to ghost hunting by her father. Early in her memoir Ghosts I Have Seen (1919), Tweedale paints a picture — one at least as charming as it is chilling — of the pair sharing “the thrill of nocturnal adventures,” meaning snooping for specters together. Another father who passed the ghost torch to his child was Edwin Wyndham-Quin, the 3rd Earl of Dunraven and Mount-Earl (1812-1871). His son was given the whimsical, if not cruel, name Windham Wyndham-Quinn (1841-1926), and he inherited his father’s earldom. But both are also identified in historical records as the Viscount of Adare, the title that preceded their earldom.

The similarities of names and titles can be confusing, and the workings of the peerage system frazzles my American brain. I’ll do my best to sort out who did what and to suggest how the child followed in his parent’s footsteps by referring to the dad as Edwin and the son as Windham. A timeline of significant events should help, too.

1843: Edwin’s Ghost HuntEdwin compiled a report of his investigation of a haunted house in County Clare, Ireland. It was published in The Spiritual Magazine in 1869. According to that report, Mr. and Mrs. Daxon moved to Kilmoran around 1824. Their residence was plagued by a menagerie of spectral manifestations: untraceable sounds of a hungry dog, of human feet, of horse hooves, and of the song of a pet canary that continued to be heard after it had been killed by a cat. A pillow, books, and writing implements were tossed by unseen hands. New noises arose, a clamor seemingly designed to scare off the Daxons: screams! gunshots through glass! and, heaven forbid, bagpipes! Four people experienced the “throwing of the a great weight upon the chest, or some part of the body,” and one time, “Mrs. Daxon felt the pressure of a very cold hand on her back.” The eerie phenomena occurred at both night and day.

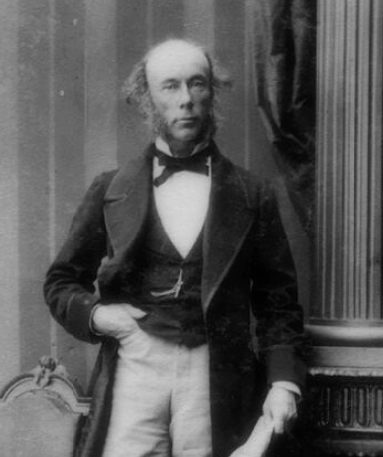

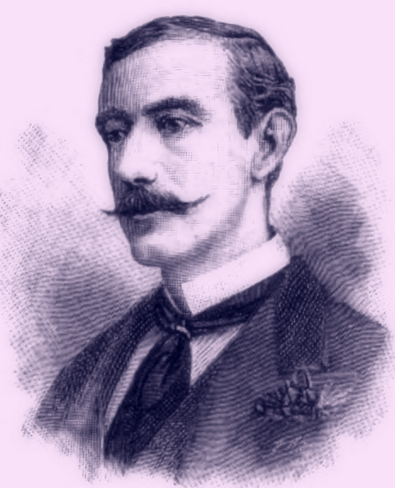

Edwin Richard Windham Wyndham-Quin, 3rd Earl of Dunraven and Mount-Earl

Edwin Richard Windham Wyndham-Quin, 3rd Earl of Dunraven and Mount-EarlAll of this information came from letters written to Edwin by numerous witnesses, and he provides ample excerpts of them in his article. Another of the letters, written by the household steward, relates a curious backstory, which Edwin says “may be related to these noises.” A family burial vault was located near the house. There, a coffin had been discovered opened. Worse yet, the steward found a fresh gash across the corpse’s pelvis! Edwin notes an Irish folk belief that “a part of the inside of a body (the liver I believe) gives power of witchcraft.”

This stuff about mutilating a corpse to practice witchcraft is pretty speculative, and Edwin must have become itchy to get more involved. In fact, he says that, “in order to satisfy myself more fully, I went to Kilmoran.” Now, we see him moving beyond an “armchair” ghost hunter! He says:

After seeing the house I was more than ever alive to the difficulty of attempting to explain the different things that occurred, by attributing them to clever contrivance or mechanism.He checked the walls. He checked the halls. “The house was not infested by rats,” he declares, ruling out that common cause for falsely branding a house as haunted.

He relates a few more odd occurrences told to him by the Daxons. Perhaps the oddest is something Edwin refrains from clarifying, but he says that “it points to a person as a possible agent; and this person was said by the people to be possessed of the power of witchcraft.” Whoa! Witchcraft again? Is this becoming a witch hunt? In the mid-1800s? That’s something one associates with, say, Joseph Glanvill’s investigation of the Mompesson residence/Drummer of Tedworth case, which happened in the late 1600s! (I’ve written about Glanvill here and witch hunts in general here.) Belief in this kind of witchcraft had virtually disappeared in the 1700s. To be sure, Edwin says he doesn’t “put very much trust in the connection between the noises and this possible cause, nor does Mrs. Daxon.” So probably not a witch. Whew!

A clue about when this in-person follow-up investigation happened is found in this statement:

In April, 1842, not long after I had made an examination of the house, I heard from Mrs. Daxon that the noises had recommenced. . . .Two maids complained of hearing things in their bedrooms, where “an invisible being” had also “pulled the bed clothes off.” The noises stopped, however, when the irritating apparition was threatened loudly with a pistol. Edwin attributes this last bit of mischief to someone playing a trick, and then he concludes the report.

There’s no indication that Edwin conducted any nocturnal surveillance, that centuries-old method of exploring a possible haunting. His contribution to the history of paranormal investigation, however, is less in his handling of this particular case or the case itself, and more in the influence he had on his son.

1850: Edwin Becomes Earl & Windham Becomes ViscountUpon the death of his father, Edwin succeeded from Viscount Adare to Earl of Dunraven and Mount-Earl. Young Windham, in turn, became Viscount Adare.

1869: Windham Reports to Edwin on D.D. HomeWindham’s memoir of one of the most famous and controversial Spiritualist mediums was published this year. Titled Experiences in Spiritualism with Mr. D.D. Home, the book’s introduction is written by none other than Edwin, who shows he knows quite a bit about Spiritualism. In addition, in the preface, Windham says that the book grew from letters about Home that he had sent to his father. Clearly, a father-son bond was bolstered by a shared interest in the paranormal.

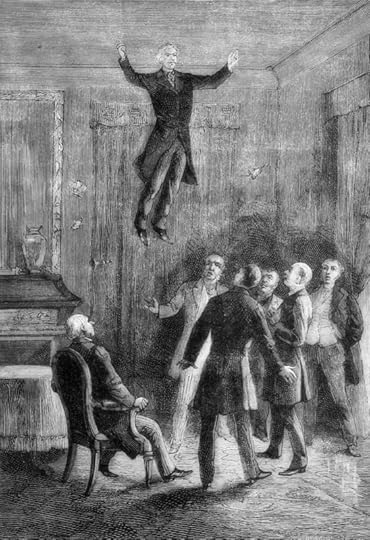

Captioned “Un Prodige de Dunglas Home,” this illustration of D.D. Home’s miraculous feats comes from Volume 2 of Louis Figuier’s

Les Mystères de la Science

(1880).

Captioned “Un Prodige de Dunglas Home,” this illustration of D.D. Home’s miraculous feats comes from Volume 2 of Louis Figuier’s

Les Mystères de la Science

(1880).The book is made up mostly of recaps of a series of séances conducted by Home, all of which Windham attended. Number 41 (pages 80-85) is probably the best known of these, since it was here that Home allegedly floated out of a window in an adjacent room and into a room where Windham waited beside two more witnesses. The incident occurred on December 16, 1868, and ever since, it has received a lot of attention, from believers such as Arthur Conan Doyle (see pages 425-426) to skeptics such as Frank Podmore (see pages 255-258). Though fascinating, it has little to do with ghost hunting. Let me shift the focus, then, to Windham and his connection to one of the most famously haunted sites in the recent history of haunted sites.

1871: Edwin Dies & Windham Becomes EarlUpon Edwin’s death, Windham succeeded to the title of the 4th Earl of Dunraven and Mount-Earl.

Windham Thomas Wyndham-Quin, 4th Earl of Dunraven and Mount-Earl, taken from a 1985 issue of The Strand Magazine1872: Windham Breaks Ground for the Stanley Hotel

Windham Thomas Wyndham-Quin, 4th Earl of Dunraven and Mount-Earl, taken from a 1985 issue of The Strand Magazine1872: Windham Breaks Ground for the Stanley HotelWindam traveled to the U.S. and, specifically, to Colorado. He was more interested in hunting big game than ghosts, and he became enchanted by the idea of owning his own wildlife preserve. With this in mind, over the next few years, he managed to acquire a huge chunk of what is now the Rocky Mountain National Park. (In that park, one can climb Mount Dunraven, named for Windham.) His methods of accumulating land were suspect, though, and the legal complications arising from them grew.

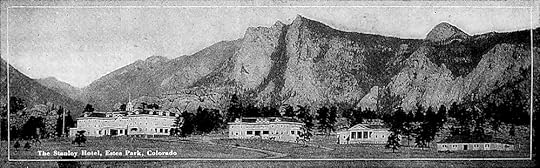

He opted instead for starting a mountain hotel, one that would capitalize on the area’s soaring tourism. The Estes Park Hotel opened in 1877. Litigation concerning his land dealings continued, though, so Windham sold the hotel to F.O. Stanley and returned to Ireland some time afterward. In 1911, that original hotel burned down, but Stanley decided to rebuild and to dub the sprawling, new structure the Stanley Hotel.

Yes, that Stanley Hotel. The one that inspired Stephen King to write The Shining (1977). The one that continues to draw ghost-hunting pilgrims from far and wide.

A promotional picture of the Stanley Hotel, published in a 1920 issue of The Du Pont Magazine1926: The Echoing of Fathers

A promotional picture of the Stanley Hotel, published in a 1920 issue of The Du Pont Magazine1926: The Echoing of FathersAnd there’s still another haunted site to discuss! Back in 1810, Windham’s Irish grandfather, Windham Henry Quin, married a Welsh woman named Caroline Wyndham and then assumed the name Windham Wyndham-Quin. Now, you see where our Windham Wyndham-Quin got his echo of a name. That grandfather didn’t just get a bride, however — no, there was a castle in Wales that came with her. It was called Dunraven Castle, and Edwin inherited it from his father, and Windham inherited it from his father.

Windham went on to write a history of the castle. Perhaps with his father’s 1843 haunted house report in the back of his mind, he devoted a short section of the book to his collection of witness testimony regarding an apparition observed there (see pages 52-55). The ghost was given one of the finest names any ghost can hope for: the Blue Lady of Dunraven.

During World War I, the building was used as a convalescent hospital for soldiers, and — though Windham says reports of the ghost go back earlier — he cites these patients, their nurses, and a former caretaker as primary witnesses. Echoing what his father had done all those year ago, Windham presents excerpts from their letters. The witnesses describe the Blue Lady as “quite calm and in no way troubled,” as “a lovely spirit and nothing to be afraid of,” and as emitting a fragrance decidedly like “mimosa.” Presumely, that refers to the plant, not the cocktail. Windham ends this section by saying the testimony is too “remarkable” to be waved off as “mere hallucinations or the result of over-wrought nerves.” Still, he leaves any final ruling to others with a penchant for ghosts.

Dunraven Castle, taken from an 1893 issue of the Evening Express, a Welsh newspaper

Dunraven Castle, taken from an 1893 issue of the Evening Express, a Welsh newspaperSadly, only some ruins of the castle can be visited today. And yet castle ruins are ghostly, right? And the Stanley Hotel offers “ghost” tours of their properties! Remaining with us are faint echoes of Edwin and Windham Wyndham-Quin’s mutual fondness for otherworldly investigation, and their weird and winding story is certainly worth remembering.

January 18, 2023

BBB.com Is Washed and Ironed — and Now I Can Ramble about Lessons Learned

For the first couple of weeks of the new year, I’ve been acting on a resolution to give BromBonesBooks.com a good laundering. I scrubbed some smudged language and stitched some ripped links to other websites. I also converted a whole lot of the pages into posts. This means there are now many more tags for finding related information, and there are more chances to post a comment.

I’ve always thought of this site as something more than place to display my stuff-for-sale. My books are important to me, of course, but so are the various historical projects that have often led to them. Two books were inspired by the Chronological Bibliography of Early Occult Detectives, my effort to reveal that occult detective fiction began much earlier than was once thought. My desire to do the same with ghost hunting manifested in the Ghost Hunter Hall of Fame, a corridor that leads to the Victorian Ghost Hunter’s Library and the Rise of the Term “Ghost Hunter” TARDIS. Again, two books resulted. My anthology of spooky, train-related stories crossed tracks with Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit. In terms of books, only Charting Crocker Land stands out in the cold. These are the projects that I washed and ironed.

Doing so, I was reminded of how digital archives have brought great opportunities to historians, including those exploring something other than popular fiction or ghosts. I recalled that, along the way, I’ve picked up some general lessons about chronicling history.

Be careful about claiming something is “the first in history.” Some brat will come along and show that’s simply not the case.Define terms. Settling on a definition for “occult detective fiction” took a few years, but since I’ve done it, I now have a firmer grasp on how to separate works in this cross-genre from that more pervasive type of detective fiction, the one with corporeal criminals. In turn, this has opened doors, admitting new works into the tradition while helping me show that validating the supernatural, not debunking it, has been a part of modern mystery fiction from the start. Not everyone will agree with my definition or the conclusions I’ve drawn from it, but at least folks might better understand what I’m getting at.Remember that humans rarely, if ever, agree on things. My hunting through the history of ghost hunting has taught me this over and over. Ever since some of the earliest extant documents about ghost hunters were written, the reality of ghosts has been debated. Roughly, that’s the 1st century CE (a.k.a. AD). I suspect this debate will continue for centuries.Here endth the lessons (and, quite likely, the extent of my wisdom). Let 2023 begin!

— Tim

January 17, 2023

A Case of Teleæsthetia: Louis Joseph Vance’s Dr. Philip Fosdick

[I]t’s possible that you’ve inherited some psychic tradition. There are families, for instance, that hand down from generation to generation the clairvoyant tendency we know by the name of second sight.

This speculative diagnosis is made by Dr. Philip Fosdick in Louis Joseph Vance’s 1920 novel The Dark Mirror. The doctor fits my definition of an occult detective by accepting the reality of clairvoyance and, specifically, teleæsthetia. The latter is perceiving things without the usual sense organs, such as seeing something going on miles and miles away. Think of having a television inside your head. A psychoanalyst, Fosdick is a member of the doctor-detective tradition that includes such key occult detective figures as Drs. Hesselius, Van Helsing, and Silence. He also uses fairly standard detective methods — including hiring a professional private detective to assist — in order to successfully solve the novel’s central mystery.

Louis Joseph Vance (1879-1993)

Louis Joseph Vance (1879-1993)That said, the doctor is almost a minor character, working in the background as the reader follows the strange story of his patient/client much more closely. He pops in now and again, and is granted “the big reveal” at the end, but this is not a step-by-step account of the investigation itself. Instead, the novel spotlights his patient, Priscilla Maine. She’s a painter living a double life through frighteningly real dreams. At first, one wonders if the artistic Priscilla might be having artistic delusions. But then Vance does quite well at complicating things as Maine’s waking life crosses paths with her more dangerous yet very romantic dream life. Promising stuff.

Prepare to Leap and Bring a MacheteUnfortunately, there are some plot holes. (How did Inez just happen to know where Mario was living?) In addition, some parts of the final solution are very predictable and show up in similar novels from well into the previous century.

Add to that Vance’s overwrought prose style. Here’s an example of the thick wordage a reader must slash with a machete:

And insidiously the tranquil surface of that contentment was flawed by apprehensions of nameless danger, of peril latent, stealthy and implacable; as though the swimmer surmised some monstrous shape of evil skulking unseen in those opaque deeps — or felt herself subtly ensnared by a current whose irresistible set was altogether toward destruction.

Remember, this is 1920. Granted, the spare prose of, say, Ernest Hemingway hadn’t quite arrived yet, but Vance’s countrymen Mark Twain, Frank Norris, and other writers had been battling against such florid language for decades.

An illustration from The Dark MirrorStill, Worth the Effort

An illustration from The Dark MirrorStill, Worth the EffortDespite those flaws, I enjoyed the novel. It’s hokey, and it’s melodramatic — yet Vance is not afraid to kill off characters, preventing a conventional happy ending. And it’s always a pleasure to meet criminal characters named Charlie the Coke or Harry the Nut, and to hear them talk the talk that Vance imagines New York street folks talk. Meanwhile, Priscilla — the uptown star of the show — is resourceful, daring, smart, and not at all a lackluster damsel in distress. There are narrow escapes aplenty, and poor Priscilla is usually the one escaping.

In fact, The Dark Mirror feels much like a Perils of Pauline-style silent-movie thriller, and it was quickly adapted to exactly that medium. (I wonder if Vance had this in mind when he was writing it.) The film still exists according to this and this source, but I haven’t found an easily watched copy of it. In the end, The Dark Mirror is far from top-notch occult detective fiction, but it would be interesting to see what the early movies did with this cross-genre.

Go to the Chronological Bibliography

Go to the Chronological Bibliographyof Early Occult Detectives — Early 1900s page.

The Human and Every Other Point of View: Gerald Biss’s Lincoln Osgood

So says Lincoln Osgood, protagonist and chief narrator in Gerald Biss‘s novel The Door of the Unreal (1919). There’s a Sherlock Holmes-ness to the statement, and lest readers fail to see Osgood as such, Biss makes it very clear. When the character arrives in the town where motorists are inexplicably disappearing, he “immediately became the cynosure of all eyes — a figure of mystery, the latest importation from Scotland Yard, an unofficial Sherlock Holmes or what not!” And some pages later, it’s implied that Osgood is “some Sherlock Holmes . . . sent from Heaven.” Not a subtle writer, this Gerald Biss.

Yet Osgood is far more open to possibilities than grumpy ol’ Holmes. Osgood accepts the fact that some culprits are supernatural — and he knows just what to do when they are! This is because, as a man of leisure with a love of travel, he calls upon his experiences in rural Eastern Europe and Russia to help him solve a mystery in England, one stumping the finest detectives of Scotland Yard. As in the novel Dracula (1897), a clear influence on The Door of the Unreal, modern-day Brits are simply too modern-day to recognize threats easily identified by those from the regions of the Continent mislabeled as “backward.”

Curiously, though, Osgood isn’t from the Continent as is Dr. Abraham Van Helsing, from whom he inherited a stalwart sense of mission and the leadership skills needed to succeed. No, Osgood is American! It’s an interesting choice for a British author, but while Osgood is an outsider, he’s also decidedly Anglo-American. In fact, the novel is annoyingly Anglocentric and xenophobic. The historical context of post-war England begins to account for this nationalistic feel.

The Culprit Also Melds CharacteristicsThe general category of the supernatural culprit is another intriguing element of The Door of the Unreal. This novel is historically important because it is one of the key examples of werewolf fiction in early 20th-century fiction, standing beside Jessie Douglas Kerruish’s 1922 occult detective novel The Undying Monster. I don’t feel that I’m giving too much away by revealing this because that lack of subtlety that marks Biss’s writing gives it away, too. Even the advertisements for and reviews of the novel didn’t hesitate in mentioning the story’s werewolves.

A full-page advertisement for The Door of the UnrealNot with a Howl but a Whimper

A full-page advertisement for The Door of the UnrealNot with a Howl but a WhimperKnowing there’s a werewolf is afoot — apaw? — isn’t a weakness of this novel. Consider Dracula: readers know very early on that the title character has more than a few unsavory habits. Nonetheless, Biss’s book ain’t Dracula. Instead of the chase across Europe in Bram Stoker’s famous novel, Biss employs an ambush to defeat the enemy. The novel’s pacing is fine at first. When we prepare for the ambush, though, there’s a lot of stiff-upper-lip, brandy-toasting male bonding. Pages of it. Chapters of it. This is instead of the story speeding to a gallop and then crashing into things gone terribly wrong and then picking itself up and dusting itself off and then getting back on the path and finally speeding to a gallop again.

In fact, when the ambush finally does occur, everything goes remarkably smoothly. True, that’s good for the characters — but it’s pretty disappointing for the reader.

In the end, Osgood is well situated for more occult adventures, and it would have been nice to learn more about his background or more about who exactly he is. Unfortunately, Biss never returned to the character. In fact, the author died only a few years after The Door of the Unreal was published. It’s too bad because — despite its shortcomings — this novel actually does have a lot of promise to it.

Go to the Chronological Bibliography

Go to the Chronological Bibliographyof Early Occult Detectives — Early 1900s page.