Tim Prasil's Blog, page 13

January 16, 2023

Arthur Machen’s Dr. James Lewis: Almost an Armchair Occult Detective

— Arthur Machen’s The Terror

Reasons to Think SoAs I was reading The Terror (1917), by Arthur Machen, I wavered on whether or not to add its central character, Dr. James Lewis, to my Chronological Bibliography of Early Occult Detectives. I had read Michael Dirda’s comment that this work “is structured like a short detective novel” (link no long available), and I knew that the American publication presents it with the subtitle: A Mystery. There’s also a first-person narrator, apparently someone who knows Dr. Lewis well enough to tell his story, hinting at something like a Watson/Holmes relationship.

Arthur Machen (1863-1947)

Arthur Machen (1863-1947)Add to that the story’s series of odd deaths, some of which suggest murder’s been done! Theories are posited, and the narrator brings the focus back to Dr. Lewis’s rejection of those theories and the development of his own. In the end, readers are led to believe that the doctor’s final theory is the closest we can come to knowing what really happened — despite that theory’s basis in the occult. Since he solves the mystery, then, Dr. Lewis must be our occult detective . . . right?

Reasons to Wonder IfWell, amid all the theorizing, Dr. Lewis doesn’t do much investigating or clue-gathering. He’s a country doctor, so he’s called in to determine the cause(s) of death in some local cases, and that’s a form of investigating . . . right? Sure, but a lot of information simply falls into his lap, for example, when his brother-in-law arrives with stories of the odd things happening in another part of Wales. At one point, Lewis himself even says, “if one is confronted by the insoluble, one lets it go at last. If the mystery is inexplicable, one pretends that there isn’t any mystery.” That’s not at all something a good detective should say . . . right?

Despite my mental ping-pong game, I ultimately decided that, yes, Dr. Lewis does qualify as an occult detective. Towards the end of the novel, he very actively joins an investigation of the Griffith farmhouse. We’re told that the doctor “had heard by chance that no one knew what had become of Griffith and his family; and he was anxious about a young fellow, a painter, of his acquaintance, who had been lodging [with them] all the summer.” Finally, some legwork along with the brain-work!

A Study in RatiocinationAnd then the last chapter confirms that Machen was borrowing from the detective genre to tell his supernatural tale. Someone’s who’s read the C. Auguste Dupin stories knows that how a detective’s thinking works is one of Poe’s chief interests. Read the first few paragraphs of “The Murders of the Rue Morgue,” and you might feel like you’re reading an expository essay on the analytical thought process. How Dr. Lewis finally arrives at a satisfactory solution to the mystery — despite multiple hurdles, such as those noted in the passage at the top of this post — is at the heart of Machen’s last chapter. As the narrator says regarding Dr. Lewis: “He told me that, thinking the whole matter over, he was hardly more astonished by the Terror in itself than by the strange way in which he had arrived at his conclusions.”

In the end, the process of what Poe would have called ratiocination plays a pivotal role in The Terror. In fact, building upon detective fiction, Machen explores how his doctor managed to expand the limits of his thinking to arrive at an occult solution to the mystery. As such, Dr. James Lewis has joined my list of early occult detectives (and can confer with the many other doctor-detectives among them there).

Go to the Chronological Bibliography

Go to the Chronological Bibliographyof Early Occult Detectives — Early 1900s page.

“Equal to All of the Ghosts”: Clark Ashton Smith’s Ghost Hunter Character

Some writers of speculative fiction become best remembered for one, maybe two, of the many works they wrote. With Mary Shelley, it’s Frankenstein. With Bram Stoker, it’s Dracula. M.R. James: Ghost Stories of an Antiquary. Shirley Jackson: “The Lottery” and The Haunting of Hill House.

To be honest, I wouldn’t have been able to name even a single title of something written by Clark Ashton Smith before discovering his 1910 tale “The Ghost of Mohammed Din.” I knew his name as one of those pulp writers from the heyday of Weird Tales and Amazing Stories. Though I’m curious about this wave of speculative fiction, my tastes keep dragging me back to the fin de siècle and Victorian stuff.

Although Algernon Blackwood’s John Silence or William Hope Hodgson’s Carnacki appeared in print about the same time (1908 and 1910 respectively), Smith’s protagonist/narrator in “The Ghost of Mohammed Din” doesn’t have the same feel. No, this supernatural sleuth feels closer to, say, the unnamed ghost-buster in H.G. Wells’ short story “The Red Room” (1896) or “the Chief” in Alexander M. Reynolds’ short story “The Mystery of Djara Singh: A Spiritual Detective Story” (1897). This latter story was published in Overland Monthly, the same magazine where Clark’s story appears.

Clark Ashton Smith (1893-1961)

Clark Ashton Smith (1893-1961)Perhaps it’s not surprising that “The Ghost of Mohammed Din” has the feel of a supernatural story from the previous century. Clark was only about seventeen years old when his tale was published, and it’s been my experience that young writers often imitate more than invent. Very likely, imitation is just an early stage in learning to write fiction for many, many authors.

Nonetheless, Smith’s detective bears all of the traits of what I call the novice-detective. In fact, he’s a prime example of a character who comes to the investigation without years of training and without a firm conviction that the supernatural really does intrude upon the physical realm. This character begins as “rather skeptical” on the subject of ghosts. Hoping to test the reality of phantoms, he gladly agrees to spend the night in a house alleged to be haunted. It’s a familiar set-up for a ghostly mystery, and like several of those, the character’s skepticism crumbles while the supernatural manifestation leads him to the evidence of an unpunished crime. In other words, rather than facing a supernatural criminal as Silence and Carnacki so often do, the ghost that appears to Smith’s amateur detective acts as a supernatural client seeking resolution of a crime.*

My preference for and familiarity with those pre-pulp stories might have dampened my enjoyment of this one a bit. Still, as an example of Clark’s early work, as an example of that tendency of young writers to imitate, and as an example of the long “dare to spend the night in a haunted house/room” tradition, “The Ghost of Mohammed Din” is certainly worth reading.

*This post was written at a time when I was developing the idea that occult detective fiction historically follows two paths: the ghostly client tradition and the demonic culprit one. This discovery led to my anthology Ghost Clients & Demonic Culprits: The Roots of Occult Detective Fiction.

Go to the Chronological Bibliography

Go to the Chronological Bibliographyof Early Occult Detectives — Early 1900s page.

“There Are Such Things”: Robert W. Chambers’ Westrel Keen.

So says Robert W. Chambers’ Westrel Keen, a detective who specializes in locating those gone missing. In fact, the series featuring this character is titled The Tracer of Missing Persons (1906). As suggested above, Keen occasionally handles a case that involves the supernatural.

Two of the five stories in the Tracer series involve the occult. The first, “Solomon’s Seal,” is a love story involving a man and woman who’ve never met. The tale touches on astral projection and “ghost” photography, but its use of an encrypted message seems to be the real focus. The second supernatural story is “Samaris,” which is mostly about a man trying to retrieve a mummy he stole from the men who stole it from him. Perhaps to give the case a more romantic, happily-ever-after spin, Chambers tosses in a bit of mystical magic at the end. I’ll just say there’s at least one way around being accused of having stolen a mummy.

Robert William Chambers (1865-1933)Less Occult Detection and More Mushy Mystery

Robert William Chambers (1865-1933)Less Occult Detection and More Mushy MysteryIn other words, in each case, Chambers is writing a romance-mystery with a dash of the supernatural, not supernatural fiction that has a detective character and a dash of romance. Westrel Keen is likely to disappoint some fans of the occult detective cross-genre because of this. The supernatural is neither unsettling nor menacing here. Instead, Keen taps into the cosmic powers of attraction rather than the cosmic powers of evil or justice.

Nonetheless, Keen is an interesting and distinctive character in 20th-century mystery. He became especially prominent in radio from the 1930s to the 1950s and even made it to a television series in the 1980s. I really don’t know for sure, but I have a hunch that none of these subsequent adventures in electronic media included ventures into the occult. Let me know if I’m wrong.

Perhaps the author himself is the greater draw for fans of supernatural fiction. Chambers’ The King in Yellow (1895) is considered a classic of early weird fiction and a possible influence on H.P. Lovecraft.

Go to the Chronological Bibliography

Go to the Chronological Bibliographyof Early Occult Detective — Early 1900s page.

Putting Your Shorthouse in Order

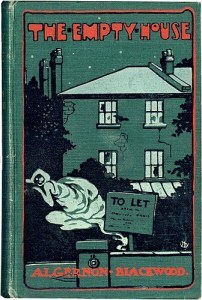

Algernon Blackwood left a puzzle for fans of occult detective/supernatural fiction. It’s his four stories featuring a character named Jim Shorthouse. From what I can tell, the first one published was “A Case of Eavesdropping,” which appeared in the December 1900 issue of Pall Mall Magazine, and the remaining three Shorthouse tales were first published in Blackwood’s collection The Empty House and Other Ghost Stories, which also includes the first.

The puzzle is 1) why Blackwood scattered the stories throughout the collection rather than putting them side-by-side and 2) why they seem to be in no particular order at all even though Shorthouse clearly evolves. The solution might well be that, even when put into a seemingly sensible sequence, the stories still feel a bit disjointed — as if Blackwood never saw them as a cohesive series but just found the name “Jim Shorthouse” interesting or handy. Scattering and jumbling the four stories in The Empty House and Other Ghost Stories reinforces the idea that they were never meant to be read as sequential.

Just the same, I suggest that there is a fairly logical order to the tales, one that reveals Shorthouse’s growth toward becoming a proper occult detective as well as the character’s evolution in mastering fear. The order I suggest is this: “A Case of Eavesdropping,” “The Strange Adventures of a New York Secretary,” “The Empty House,” and then “With Intent to Steal.” Indeed, this is the order I reprint them in From Eerie Cases to Early Graves: 5 Short-Lived Occult Detective Series.

Algernon Blackwood (1869-1951)1: An Inexperienced Ghost-Seer

Algernon Blackwood (1869-1951)1: An Inexperienced Ghost-SeerI suspect most readers would agree that “A Case of Eavesdropping” should come first. By itself, it really doesn’t qualify as an occult detective story. A young Shorthouse has moved from England to what is presumably New York City. He moves into a room with noisy neighbors and gets very scared when he discovers they’re, well, not entirely there. His reaction is to vamoose — and that ends the story. There’s no detecting, no mystery solving, no detective/client or detective/criminal relationship. However, we do learn that Shorthouse can perceive ghosts when others cannot. This is a first step toward becoming a divining-detective when read with the other tales in mind. Also, when Shorthouse flees the haunted room in the end, we see that fear has beaten him.

2: An Apprentice DetectiveThere’s a bit of a leap to “The Strange Adventures of a New York Secretary” — the next in my ordering of the series — but the fact that “Eavesdropping” and “Strange Adventures” are both set in New York is the first clue that they belong together. (Though it’s not entirely definite, “Empty House” and “With Intent to Steal” suggest that Shorthouse has moved back to England.) More importantly, “Strange Adventures” presents a more settled, more mature Shorthouse. He’s considering his financial future, after all. He’s not much more adept at occult detection, though he jokes about feeling like a detective at one point. Despite these small steps forward, he’s now much tougher when it comes to coping with the crazy (and kind of hokey) menagerie of Gothic creepiness into which Blackwood drops him. Important to his overall character evolution, he’s now much more cognizant of how to manage, if not master, his fear.

3: A Journeyman Ghost HunterThere’s another jump to “The Empty House,” and though Blackwood quickly describes Shorthouse as a “young” man, he somehow feels older now than a secretary running an errand. I think it’s because of the introduction of Shorthouse’s wrinkle-cheeked, “elderly spinster aunt.” Not his grandmother, mind you, who would separate the characters by a full two generations. No, his aged aunt. Let’s imagine Shorthouse in his late 30s, if not well into his 40s. Add to this the fact that Shorthouse reveals clear signs of having become a good ghost hunter. This time, he doesn’t just accidentally discover himself in a haunted place. He accepts an invitation to explore one! And he knows the right and proper investigative routine, making notes as he goes.

Nonetheless, one still could probably swap “Empty House” and “Strange Adventures” either way if not for two more considerations. First, Shorthouse is advancing in terms of facing fear, since this time he has to manage not just his own fear, but that of his aunt, too. Second, Shorthouse’s added burden of having his aunt as companion on an occult investigation leads especially well into the final story, which illustrates the value of having a companion along when ghost hunting.

4: A Master Occult DetectiveMuch as it’s easy to put “Eavesdropping” first, it’s also easy to put “With Intent to Steal” last. Shorthouse is now decidedly more mature — even worldly — and he’s fully committed to combating supernatural evil. His relationship with a companion, as I mention above, is also central to this case. That companion serves as the narrator in the style of Dr. Watson, reinforcing the notion that Shorthouse has very much arrived as a true occult detective. As the two characters spend the night in a haunted barn, Shorthouse tells of his earlier experiences, and a reader might wonder if the companion here isn’t, in fact, the narrator of the earlier three stories, too! Blackwood never settles that issue, though.

Nonetheless, the author does confirm that even a Sherlock Holmes can benefit from having a Dr. Watson at his side. This tale brings Jim Shorthouse to fruition, from a naïve victim who flees from ghosts to a mature vanquisher of supernatural fiends, one wise enough to know when help is needed.

Go to the Chronological Bibliography

Go to the Chronological Bibliographyof Early Occult Detectives — Early 1900s page.

Is Willa Cather’s “The Affair at Grover Station” a Work of Occult Detection?

Willa Cather is a key figure in American literature. Be it O Pioneers!, My Ántonia, or The Song of the Lark, her novels have earned a favored place on the bookshelves of many readers, and her short stories — which include “A Wagner Matinee,” “The Sculptor’s Funeral,” and “Paul’s Case” — are often anthologized. In 1922, she won the Pulitzer Prize for her novel One of Ours.

I’ve personally been especially interested in her tales of Bohemian (think Czech) immigrants on the plains, works such as “Peter,” My Ántonia, or Neighbor Rosicky. Those characters remind me of my roots, even though my forebears settled in Chicago, not Nebraska. And in my Vera Van Slyke chronicles, there’s a recurring character named Eric “Rick” Bergson, who moves to Chicago from Nebraska and who seems to have stepped straight out of Cather’s novel about Swedish newcomers on the plains, O Pioneers!

Did She Wet Her Toe in Occult Detection?While hunting for occult detectives, I read one of Cather’s early short stories. It’s called “The Affair at Grover Station” (1900). I had a very mixed reaction to it. First, I was delighted to find out that Cather not only dabbled in murder mystery — she also dabbled in occult detection! I had known the author only for her works of realism, but since discovering this story, I’ve learned that at least two of Cather’s other stories have a ghostly quality to them: “The Fear that Walks by Noonday” (1895) and “Consequences” (1915). She liked to tell a spooky story on occasion, it seems.

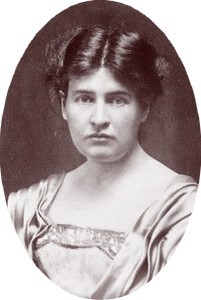

Willa Cather (1874-1947)Collecting Evidence

Willa Cather (1874-1947)Collecting Evidence“The Affair at Grover Station” features a character named “Terrapin” Rodgers, who becomes an amateur detective while confirming that a fellow railroad employee was the victim of murder. Though the investigation proper doesn’t start until well into the story, Rodgers is assigned by his dispatcher to find out why a station agent has gone missing. He surveys the station. He then questions the missing agent’s landlady. He questions a little girl who’d seen him with a stranger whose “eyes snapped like he was mad, and she was afraid of him.” Rodgers next finds blood on the pillow where in the agent slept. All very detective-y.

But the “smoking gun” that solves the mystery comes not from the tangible world. No, that crucial clue is exactly what places this character on my Chronological Bibliography as a novice-detective. Enough said about that. No spoilers.

A Story SpoiledI do feel prompted to spoil the story in another way, though, if Cather doesn’t go ahead and do this herself. “The Affair at Grover Station” has a prime suspect who makes this story very much a part of the Yellow Peril movement of the late 1800s and early 1900s. That suspect is a man named Freymark. Cather is far from subtle at signaling him to be the criminal. She has Rodgers say of Freymark:

He was a wiry, sallow, unwholesome looking man, slight and meagerly built, and he looked as though he had been dried through and through by the blistering heat of the tropics. His movements were as lithe and agile as those of a cat, and invested with a certain unusual, stealthy grace.We learn that Freymark’s father was French and his mother Chinese. Though this makes him bi-racial, of course, we later read that “he was of a race without conscience or sensibilities.” Freymark’s criminal nature is attributed to his Chinese heritage. Though such bigotry was widespread in the U.S. when the story appeared, I was sorry to see it in Cather, especially given that Mark Twain, Bret Harte, and Ambrose Bierce were writing stories that — while perhaps not directly sympathetic to Chinese immigrants — were certainly critical of the racism aimed against them. Cather, it seems, could paint immigrants from Bohemia or Sweden as admirable additions to the national landscape. But, in this story, a half-Chinese immigrant is portrayed as inherently evil.

Needless to say, this is not one of my favorite Cather stories. My hunt for early occult detectives has yielded many surprises, and the fact that Cather is now among the many authors who explored this cross-genre of fiction is certainly intriguing. The fact that it’s made me reassess my appreciation of Cather, though, is disheartening.

Go to the Chronological Bibliography

Go to the Chronological Bibliographyof Early Occult Detectives — Early 1900s page.

January 15, 2023

An Investigator in Psychic Forms: Marie Corelli’s Dr. Maxwell Dean

Dr. Watson convinces Sherlock Holmes to take a relaxing trip to Surrey in “The Reigate Squires” (1894) and another one to Cornwall in “The Devil’s Foot” (1910). Ellery Queen planned to take a break on the coast in The Spanish Cape Mystery (1935). Hercule Poirot is on holiday in Devon in Evil Under the Sun (1941). Miss Marple’s sunny get-away is interrupted in The Caribbean Mystery (1964) as is her quite likely foggy get-away to London in At Bertran’s Hotel (1965). Needless to say, even on vacation, a detective can’t say no to investigating a good mystery.

This is the case in Marie Corelli’s Ziska: The Problem of a Wicked Soul (1897), in which Dr. Maxwell Dean lounges among the British leisure-class as they travel through Egypt. It’s there that he uncovers a clandestine plot for revenge! The interesting part is that the original injustice being avenged happened a few millennium in the past.

Cosmic JusticeDr. Dean works on the theory that the cosmos finds a way to re-balance the scales of justice regardless of how long it takes, and this idea underlies the supernatural events of the novel. While I’ll do my best to avoid spoilers, be aware that Corelli hardly bothers to do the same. Among other things, Dr. Dean’s frequent conversations about his theories make the ending pretty easy to predict. Unfortunately, he does not practice what he preaches: “There are certain subjects connected with psychic phenomena on which it is best to be silent.”

Marie Corelli, a.k.a. Mary Mackay (1855-1924)

Marie Corelli, a.k.a. Mary Mackay (1855-1924)Nonetheless, this is an enjoyable novel. Corelli’s narrator has a humorously satirical tone, targeting upper-class British customs, values, and ethnocentrism. There’s almost a drawing-room comedy feel to some of the scenes, and the characters are engaging. For instance, while Dr. Dean is a distinctively drawn and likeable occult detective, the otherworldly figure in Ziska is much more mysterious than monstrous, even stirring readers’ sympathy. It becomes interesting to compare and contrast the English hero and the decidedly not English villain in this novel to those in Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Richard Marsh’s The Beetle, both of which were published in the same year. In fact, 1897 was a banner year for occult detective fiction!

A Ph.D. in the PsychicalDespite his title, Dr. Dean is not among those occult detective characters I classify as “doctor-detective.” He’s not a medical doctor. Instead, he says, “I am a doctor of laws and literature,–a humble student of philosophy and science generally.” He seems fascinated by virtually everything, but he has specific experience in things supernatural. Along with having formulated theories about “scientific ghosts,” he is well-versed in “the discoveries of psychic science” and is “an investigator in psychic forms.” He says the case of Princess Ziska is “the most interesting problem I have had the chance of studying!” This implies he’s investigated other such problems, and all of this adds up to his being a specialist-detective.

At the same time, Dr. Dean is unusually passive for an occult detective. Sure, he detects a lot and solves puzzles and knows things that no one else seems to know. However, unlike Dr. Van Helsing in Dracula or Augustus Champnell in The Beetle, Dr. Dean takes no real action against the novel’s supernatural entity even after he’s figured out its dangerous, if not deadly, intentions.

Man Is Not SupremeThis probably grows from Corelli’s efforts to affirm that there’s a realm beyond the physical world. Arguably, that’s the goal of any writer spinning a supernatural story, but it’s handled in an overt and downright heavy-handed way here. Corelli clearly wants to deflate the arrogance accompanying the notions that the vast universe is limited to the mere mundane and that puny humans are large and in charge. As Dr. Dean pontificates:

More wills than one have the working out of our destinies. . . . Man is not by any means supreme. He imagines he is but that is only one of his many little delusions. You think you will have your way; Gervase thinks he will have his way; I think I will have my way; but as a matter of fact there is only one person in this affair whose ‘way’ will be absolute, and that person is the Princess Ziska.Princess Ziska, we learn, is not the unholy and unnatural foreign invader found in Dracula or The Beetle. No, she’s a supernatural “agent” tasked with — or, possibly, granted the opportunity to — right a crime left long unaddressed. Dr. Dean’s job is not to thwart that act of justice but to try to explain it to people living an age of materialism and skepticism.

As such, Corelli’s Ziska is not the usual occult detective versus scary monster story. Instead, it’s an occult detective versus fin de siècle secularization parable. If read with this mind, the novel becomes a clever twist on standard supernatural fiction.

Go to the Chronological Bibliography of Early Occult Detectives — 1800s page.

Go to the Chronological Bibliography of Early Occult Detectives — 1800s page.

A Bare Bones Ghost Hunter: The Narrator of H.G. Wells’ “The Red Room”

In 2016, it was announced that a ghost story written by H.G. Wells — one never before published and virtually forgotten — was discovered at the University of Illinois. The story, “The Haunted Ceiling,” involves a man harassed by the vision of a woman with her throat slit, which appears on his ceiling. The creepy tale was (finally) published in an issue of The Strand.

When one thinks of H.G. Wells, one might think first of science fiction — or “scientific romance,” as Wells himself was wont to call it. He also wrote a fair amount of supernatural fiction. Perhaps not surprisingly given Wells’ level of creativity, a lot of this branch of his writing is not at all traditional supernatural fiction. I only know of two other works that can be called ghost stories (if, by that, we mean stories with right and proper ghostly entities in them): “The Red Room” (1896) and “The Inexperienced Ghost” (1902).

Herbert George Wells (1866-1946)

Herbert George Wells (1866-1946)The title of “The Inexperienced Ghost” hints that it’s a humorous tale. “The Red Room,” though, is very serious, and it features a protagonist who qualifies as an occult detective character. The character also serves as narrator, and Wells only provides the bare bones of information about him. Perhaps tales of a skeptic hoping to debunk rumors of ghosts had become so routine by 1896 that the author didn’t feel the need to give much exposition.

Starting in the MiddleExactly what motivated the narrator’s interest in the haunted “great red room of Lorraine Castle” and how he got permission to investigate it go unexplained. The narrator does mention an earlier investigation conducted by his “predecessor,” a young duke who died in the effort. Does this mean he inherited the house from the duke, or was that duke just the previous investigator of the strange room? Or is the narrator investigating the duke’s death? Again, unexplained.

Perhaps this absence of exposition helps explain why “The Red Room” jumps to a level of anxiety at the very start, when that narrator interviews the keepers of the castle. These residents, twisted and decrepit with age, become the first source of discomfort.

Well-Prepared, but InexperiencedOne thing we do know about our mysterious narrator is he’s armed, and his careful and “systematic investigation” of the Red Room make him, at least, a well-prepared novice detective. He certainly goes into that notorious room ready to do battle…

But he finds something very unpredictable once he enters the Red Room. Considering that candles were repeatedly extinguished, we know that the invisible culprit is both supernatural and downright unpleasant. But is it a ghost in the traditional sense? In a very basic way, Wells’ detective is like the more “fleshed-out” one in Rudyard Kipling’s “The House Surgeon” in that they both confront something other than a once-breathing, now-disembodied person. What both detectives find in their respective haunted rooms is something that very much bedevils us all.

Go to the Chronological Bibliography

Go to the Chronological Bibliographyof Early Occult Detectives — 1800s page.

Two Occult Detectives from One (Unexpected) Author: Rudyard Kipling’s “Mr. Perseus” and Strickland

“Mr. Perseus” is the nickname given to an otherwise anonymous occult detective Rudyard Kipling’s 1909 short story “The House Surgeon.” Despite being named for a legendary monster hunter, the character is not especially well-versed in supernatural investigation. So far as readers can tell, he’s not a crime investigator, either. While many occult detectives are medical doctors, this fellow is only mistaken for one. Perhaps Kipling was having a bit of fun with the tradition.

However, I’m convinced this is a legitimate occult detective story. When given the task of figuring out why a house casts a cloud of despair over people who stay in it, Kipling’s protagonist takes on the role quite seriously! At least, he does after he’s felt swallowed by the gloom of the place himself. And he approaches the mystery very much in terms of detective work. Narrating his own adventure, he says:

I am less calculated to make a Sherlock Holmes than any man I know, for I lack both method and patience, yet the idea of following up the trouble [of the haunted house] to its source fascinated me.Later, he almost apologizes for detailing an interrogation “because I am so proud of my first attempt at detective work.” This, then, is a novice occult detective — but an occult detective nonetheless.

Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936)In the end, our man succeeds at exorcising “the dumb Thing that filled the house with its desire to speak.” The method of exorcism, though, is revealing. Since the manifestation involves psychological depression, it’s fitting that the “cure” for the haunting be a kind of intervention. In fact, the problem is as much the house’s former inhabitants, who are still living, as the ghost.Strickland: Occasional Occult Detective

Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936)In the end, our man succeeds at exorcising “the dumb Thing that filled the house with its desire to speak.” The method of exorcism, though, is revealing. Since the manifestation involves psychological depression, it’s fitting that the “cure” for the haunting be a kind of intervention. In fact, the problem is as much the house’s former inhabitants, who are still living, as the ghost.Strickland: Occasional Occult DetectiveAnother of Kipling’s occult detectives is named Strickland. He was first introduced to readers as a police officer in a tale called “Miss Youghal’s Sais” (1887). It’s basically a love story, though, in which Strickland finds a way to woo and win Miss Youghal. No supernatural stuff here. He next appeared in another non-occult story, “The Bronkhorst Divorce Case” (1888). It’s in the next two Strickland stories where the character appears as a detective who grapples with a supernatural reality: “The Mark of the Beast” (1890) and “The Return of Imray” (1891). Curiously, Kipling places the two occult stories earlier in Strickland’s life, before he ever met Miss Youghal.

The website of the Kipling Society suggests there are additional Strickland stories, but I believe only the two noted above involve the supernatural. One might also toss “By Word of Mouth” (1887) into this fictional universe, since it’s the story of Dr. Dumoise’s otherworldly death that’s mentioned in “The Mark of the Beast.”

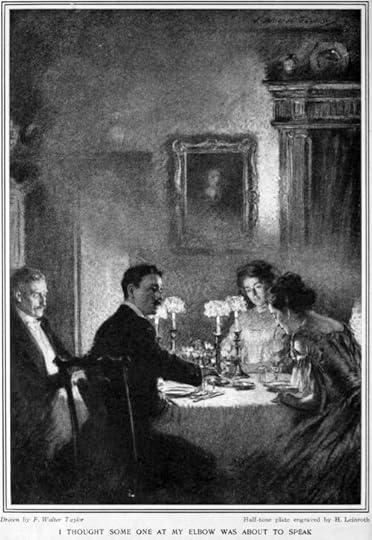

An illustration from the “The House Surgeon” that accompanied the story in Harper’s Magazine“Mr. Perseus” Is the More Traditional Detective

An illustration from the “The House Surgeon” that accompanied the story in Harper’s Magazine“Mr. Perseus” Is the More Traditional DetectiveEven though Strickland is a police officer, I think “Mr. Perseus” is the more traditional detective — at least, in terms of how they’re presented in these tales. In “The Mark of the Beast” and “The Return of Imray,” the case and the solution seem to more or less fall into Strickland’s lap. They’re great stories — they’re just not especially great detective stories. In a sense, the amateur status of “Mr. Perseus” heightens the challenge of his investigating and ultimately solving the case. That said, I suspect many readers will find “The Mark of the Beast” the most gripping in terms of horror, and it fits very well with the more monstrous tales in Ghostly Client and Demonic Culprits: The Roots of Occult Detective Fiction.

All the stories are worth a look, though, if only because of the fame of the author. When I first learned that Kipling had dabbled in the occult detective cross-genre with one story, I was surprised. I’m now a bit astonished to learn that he was drawn to create such fiction repeatedly.

Go to the Chronological Bibliographyof Early Occult Detectives — 1800s page.January 14, 2023

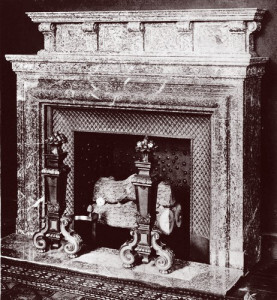

Sarah P.E. Hawthorne’s Mr. Curtis: Poster Boy for Novice Occult Detectives

A character known only as Mr. Curtis appears in Sarah P.E. Hawthorne’s 1888 short story “The Ghost of the Grate.” He’s one of the very few occult detectives from the 1800s who’s also a card-carrying professional detective, albeit in the crime-solving business. In fact, for a moment, I wondered if he might be the first professional detective on my Chronological Bibliography. But, no, this honor belongs to Mr. Burton from Seeley Regester’s The Dead Letter, which was published in 1866.

Still, Burton falls under the heading of a divining-detective due to his relying on his daughter’s clairvoyance and his own semi-psychic abilities when conducting a criminal investigation. Curtis, on the other hand, confronts a spectral manifestation — and only then does he accept the reality of the supernatural. Doing so allows him to solve the mystery. In fact, in the concluding paragraph of his first-person narrative, he says: “I had never been a believer in the supernatural, and this was my first and only experience with the great unexplainable.” As such, Hawthorne’s Mr. Curtis stands as very fitting example of the novice occult detective.

Occult Detectives See BeyondThough the story itself is a bit lackluster and conventional, it works well to illustrate how occult detective fiction challenges traditional mystery fiction by having its key investigator character confront a mystery that goes beyond the physical and the rational. This, of course, has philosophic implications regarding whether or not we can understand the whole of our world through scientific exploration.

Curtis mentions an earlier case he had handled, and I wondered if Hawthorne might’ve written that story or any others with this detective. I don’t think she did. In fact, I couldn’t dig up much information at all on the author herself. Some cursory research reveals she lived in Maine. She was a “regular contributor” to a magazine called Success with Flowers and had regional fiction published in Peterson’s and Demorest’s. There’s a brief biography in The Literary World that says Hawthorne wrote humorous pieces known as the “Simon Ciders” letters. It doesn’t appear that she specialized in supernatural or mystery fiction, so “The Ghost of the Grate” was probably a one-time lark. About the most curious thing I discovered is that her maiden name is the same as her detective’s: Curtis.

“The Ghost of the Grate” is not a great story. If it’s predictable, it’s also short. For students and fans of early occult detective fiction, it’s likely worth fifteen minutes of your time.

Go to the Chronological Bibliography

Go to the Chronological Bibliographyof Early Occult Detectives — 1800s page.

What if Dr. Watson Could Read Minds? B.J. Farjeon’s Devlin the Barber

There is a long line of what I call “divining-detectives,” who turn to clairvoyance, palm-reading, etc. to solve a crime. Such characters are probably not most occult detective fans’ first choice in reading. They tend to like it when the culprit involves the supernatural. If the detective uses supernatural means to solve the mystery, well, meh. (But it can still be pretty cool if they combine some form of divination with their own human wits to win the day. Or, should I say, to win the night?)

Now, what happens when the source of mystery is as much the clairvoyant character as the crime? This is the premise of B.L. Farjeon’s Devlin the Barber (1888). The title character, as his name suggests, has a devilishness about him. Indeed, his landlady is convinced this demon barber is luring her husband toward ruination. The unnamed narrator, though, sees Devlin — and especially his ability to read the minds of those whose hair he cuts — differently. When the mystery of Devlin intersects with a murder mystery, this narrator has been hired to investigate, the prospect of working with an assistant who can read minds becomes very tempting indeed.

Benjamin Leopold Farjeon (1838-1903)A Faustian Twist

Benjamin Leopold Farjeon (1838-1903)A Faustian TwistHerein lies the beauty of Devlin the Barber as well as the twist that makes this novel something other than a murder mystery with a contrived, clairvoyant cheat. Is this a Faustian story of an amateur detective lured into using sinister if not sinful, supernatural means to solve his case? He is recently unemployed, after all, and he has been offered a lot of money to solve the murder. In this regard, Farjeon’s contribution to the tradition of the divining-detective is particularly inventive.

Unfortunately, I found the novel’s pacing to be a problem. The landlady’s testimony of her dealings with Devlin takes up chapter after chapter after chapter . . . delaying the heart of the story, which is the relationship between the narrator/detective and Devlin. Once the detective forms a pact with Devlin, though, things pick up. The murder mystery is fairly easily solved and resolved, and it’s a touch goofy, too. However, the Devlin mystery provides a counterbalance to this that’s, well, rather hard to resist.

Go to the Chronological Bibliographyof Early Occult Detectives — 1800s page.