Tim Prasil's Blog, page 17

January 2, 2023

Francis Smith and the Tragedy of the Black Lion Lane “Ghost Hunters”

For several years, I’ve been on a quest to find the earliest published use of the term “ghost hunter,” and as of today — March 15, 2021 — the farthest back in time I’ve gone is January, 1804. [UPDATE: I’ve since found earlier uses of it.] That term is used in news articles about several men who went in search of the Hammersmith ghost. Since it turned out to be a hoax, I might have teased about this team being an early nineteenth-century “Scooby Gang.” But it wasn’t much of a laughing matter, since the overzealous “ghost hunt” led to an innocent man being shot.

Here’s the story. In the final months of 1803, something ghostly was seen in the churchyard and surrounding avenues of the Hammersmith district of London, and the residents were upset. According to a newspaper report from January 13, 1804:

Women and children have nearly lost their senses. One poor woman, in particular, who was far advanced in her pregnancy of a second child, was so much shocked at this supposed Ghost, that she took to her bed, where she still lies in great danger -- The Ghost had so much alarmed a sturdy waggoner [driving sixteen passengers] that the driver took to his heels, and left waggon and horses, so precipitately, that the whole were greatly endangered.I’m not sure of its reliability, but a report published about a decade after the fact elaborates on the pregnant woman, saying she was accosted by the ghost in the churchyard and the trauma was so great that she died two days later. The same source says that rumors were circulating that the ghost was that of a man “who had cut his throat in the neighbourhood above a year ago.” But some of the residents denied that something supernatural was afoot, and they tried to expose whoever was creating havoc in the guise of a ghost. After this failed to produce results, a reward was offered.

Francis Smith Got His GunThat’s when Francis Smith perhaps got a bit drunk and definitely got his gun. He went out to hold a stake-out in Black Lion Lane, one of the spots where the culprit was known to lurk. One 1804 account, found in Kirby’s Wonderful and Scientific Museum, suggests Smith acted by himself (albeit having told his plans to the town watchman, William Girdler.) However, the January, 1804 issue of the Universal Magazine of Knowledge and Pleasure reports:

A person of the name of Smith, a Custom-house officer, with a few others, lured by the hope of the reward, determined to watch the phantom, and for that purpose provided themselves with arms, and took post in Black Lion Lane. They were situated there on the night of January 3rd, between the hours of ten and twelve: a man of the name of Mil[l]wood, who was by trade a plaisterer, unhappily had sent his wife out upon some business, and, imagining she staid longer than was necessary, determined to go in search of her, in order to protect her home at that dreary time of night. The ill-fated man was dressed as usual in his white flannel jacket, and, having parted with his sister at his own door, proceeded along Black Lion Lane, where the ghost-hunters were lying in wait.[Bold added.]Though an article published the same month in The Scots Magazine and Edinburgh Miscellany is otherwise different, this passage is virtually identical. I’m not sure who’s plagiarizing whom, but the events in Hammersmith were bringing public exposure to the term “ghost-hunter.” It also appears in that newspaper report above. (The discrepancy in reporting whether Smith was acting alone or with others might be explained by an 1805 register of the previous year’s news, which says that “several young men had gone every evening, in order to detect the impostor. . . .” While Smith might have been on his own, a number of “ghost hunters” were lurking along the alleyways. Maybe these other lads can collectively be called the Hammersmith Scooby Gang.)

Smith Shot MillwoodThat’s hardly important, though, given what happened next. Smith spotted Millwood, the man dressed in white. Smith shot his gun. The bullet entered Millwood’s jaw and fatally penetrated his spine. Smith realized what he had done, surrendered to authorities, and was tried for wilful murder. He was found guilty and was committed to Newgate Prison. Originally sentenced to execution, he was later pardoned by the King and served only a one-year sentence.

The Hammersmith Ghost as depicted in Kirby’s Wonderful and Scientific Museum (1804), one of the most complete contemporary accounts of the hoax.

The Hammersmith Ghost as depicted in Kirby’s Wonderful and Scientific Museum (1804), one of the most complete contemporary accounts of the hoax.The trial revealed that Smith had given Millwood a verbal warning, shouting, “Damn you, who are? and what are you? Speak or I’ll shoot.” This is verified by the court transcript. In fact, both the transcript and the Scots article say that Millwood had admitted to being mistaken for the ghost on a previous occasion. Of course, none of this excuses Smith’s rash action, even if he were driven by a desire to protect his neighbors. The victim was dressed in the garb of his trade, after all, not in anything resembling “a white sheet, and sometimes in a calf-skin dress, with horns on its head, and glass eyes,” as Millwood’s sister, under oath, said the ghost had been reported to appear.

Nonetheless, Francis Smith earns a place in the Ghost Hunter’s Hall of Fame, if not for having an indirect role in popularizing the term “ghost hunter,” then for opening the 1800s with a profound example of how not to go about that pursuit.

A Confession Came Too LateBy the bye, the actual culprit disguising himself as a ghost was revealed shortly after Smith was taken into custody. A shoemaker named John Graham confessed to wanting to punish his apprentices after they had teased and terrified his children with stories of ghosts. But this excuse seems doubtful. At the trial, Thomas Groom, a brewer’s servant, explained that, as he had been passing through the churchyard one time, “some person came from behind a tomb-stone, which there are four square in the yard, behind me, and caught me fast by the throat with both hands, and held me fast.” Groom escaped thanks to a fellow servant who was nearby. If Graham were the attacker here, the lesson he hoped to teach his apprentices seems wildly misdirected!

That article suggesting Smith acted alone also provides some of the best information about what all preceded his shooting Millwood. The piece ends by saying the reports of a woman dying after being traumatized by the specter and the ghost itself wearing an animal skin and horns “owe their rise to newspaper fabrication.” In other words, as with many ghost stories, it’s hard to know who to believe.

Events Morphed into LegendWere the ill-fated pregnant woman and skittish bus driver creative flourishes intended to sell newspapers as events were unfolding? A researcher of ghostlore must always work on the assumption that there’s at least as much fiction and fact in historical documents. Take, for instance, the 1824 edition of The Newgate Calendar. This publication began in the mid-1700s as a monthly report of executions performed at England’s Newgate Prison and evolved into a long-lived series of volumes spotlighting sensational criminal cases. It’s not a good source for accurate history, but the tales are gripping and the illustrations are intriguing. Starting in 1825, the series introduced illustrations of the Hammersmith incident.

Captioned “The pretended Hammersmith Ghost frightening a poor Woman to death,” this illustration appears in

The Newgate Calendar

of 1825.

Captioned “The pretended Hammersmith Ghost frightening a poor Woman to death,” this illustration appears in

The Newgate Calendar

of 1825. Captioned “Shooting a Ghost,” this illustration by “Phiz” appeared in

The Chronicles of Crime; or, The New Newgate Calendar

(1887).

Captioned “Shooting a Ghost,” this illustration by “Phiz” appeared in

The Chronicles of Crime; or, The New Newgate Calendar

(1887).

Samuel Johnson Misconstrued

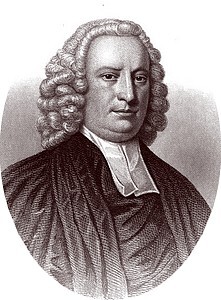

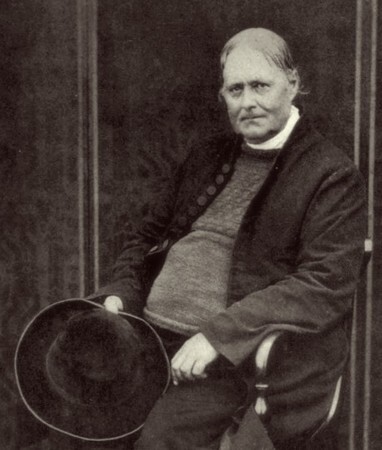

Samuel Johnson (1709-1784)Curiosity Is Not ConvictionIt is wonderful that five thousand years have now elapsed since the creation of the world, and still it is undecided whether or not there has ever been an instance of the spirit of any person appearing after death. All argument is against it; but all belief is for it.

Samuel Johnson (1709-1784)Curiosity Is Not ConvictionIt is wonderful that five thousand years have now elapsed since the creation of the world, and still it is undecided whether or not there has ever been an instance of the spirit of any person appearing after death. All argument is against it; but all belief is for it.English author and lexicographer Dr. Samuel Johnson is frequently named as a prominent person who believed in ghosts. For instance, in Moby Dick (1851), Herman Melville writes: “Are you a believer in ghosts, my friend? There are other ghosts than the Cock-Lane one, and far deeper men than Doctor Johnson who believe in them.” A few years later, the anonymous author of “A Night in a Haunted House” (1855) had that tale’s narrator say: “Dr. Johnson declares it is impossible to account for the belief in ghosts among nearly all nations except by supposing the reality of their appearance.”

It turns out this is a misrepresentation of Johnson’s views on ghosts. In Life of Samuel Johnson, LL.D. (1791), James Boswell says the idea that ghosts must be real because they’re such a widespread phenomenon was expressed, not by Johnson himself, but by a fictional character in his novel Rasselas (1756). There, Imlac says:

There is no people, rude or learned, among whom apparitions of the dead are not related and believed. This opinion, which perhaps prevails as far as human nature is diffused, could become universal only by its truth; those that never heard of one another would not have agreed in a tale which nothing but experience can make credible.

He Debunked Cock LaneIn reality, Johnson had a much more agnostic view, and Boswell takes a very clear stance against Johnson being a dupe when it came to ghosts. For evidence, the biographer points out that Johnson was part of a team that debunked the famous Cock Lane Ghost case. The Cock Lane “story had become so popular, that he thought it should be investigated.” Johnson formed a team of, essentially, occult detectives. (At this point, I’m picturing an assemblage of properly powdered and wigged gentlemen ghost hunters, ideally accompanied by a dog named Sir Scooby of Doo.) Johnson later reported the committee’s findings, saying that the child involved in the alleged haunting “has some art of making or counterfeiting particular noises, and that there is no agency of any higher cause.”

An illustration from The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction 34.969 (Sept. 21, 1839) p. 193.How to Validate a Ghost

An illustration from The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction 34.969 (Sept. 21, 1839) p. 193.How to Validate a GhostDespite finding fraud in that particular case, Johnson appears to have kept an open mind about ghosts. He knew there could be psychological reasons for thinking one is being haunted — especially, a sense of shame — but there are also ways to tell if one is in the company of a genuine spirit. He explained that,

if a form should appear, and a voice tell me that a particular man had died at a particular place, and a particular hour, a fact which I had no apprehension of, nor any means of knowing, and this fact, with all its circumstances, should afterwards be unquestionably proved, I should, in that case, be persuaded that I had supernatural intelligence imparted to me.Presumably, though, this had never happened to Johnson during his lifetime.

(For more on the Cock Lane ghost case, visitThe Cock Lane Ghost TARDIS page.)

The Reverend Richard Dodge: Spectral Exorcist of Fearful Repute

Should anyone be looking for a real-life figure upon which to base a fictional occult detective, let me suggest the Reverend Richard Dodge (c. 1653-1746). Little is known about the actual man, but his reputation as an exorcist of malevolent spirits made him legendary. Literally. He’s become part of Cornish folklore.

The earliest reference to Dodge that I’ve found is in a work written by Thomas Bond and delightfully titled Topographical and Historical Sketches of the Boroughs of East and West Looe, in the County of Cornwall; with an Account of the Natural and Artificial Curiosities and Picturesque Scenery of the Neighbourhood (1823). There, we read that Dodge was vicar of Talland — and, “by traditional accounts, a very singular man. He had the reputation of being deeply skilled in the black art, and could raise ghosts, or send them into the Red Sea, at the nod of his head.” Bond says that many of these spirits “were seen, in all sorts of shapes, flying and running before [Dodge], and he pursuing them, with his whip, in a most daring manner.” Before presenting the tombstone inscription of this whip-wielding, Cornish clerical cowboy who fought the Powers of Darkness, Bond says Dodge “was a worthy man, and much respected; but had his eccentricities.”

As I say, if this isn’t fodder for an occult detective character, then I don’t know what!

The Talland Church from The Western Antiquary; or, Devon and Cornwall Note-Book 4.5 (Oct., 1884) p. 105.Another Version of the Dodge Legend

The Talland Church from The Western Antiquary; or, Devon and Cornwall Note-Book 4.5 (Oct., 1884) p. 105.Another Version of the Dodge LegendThe next chronicle of Dodge that I’ve located is “The Spectral Coach,” Thomas Q. Couch’s record of a Talland legend he once heard “by a country fire-side.” At least, that’s what he says in The History of Polperro: A Fishing Town on the South Coast of Cornwall (1871), where it’s reprinted in an appendix. The transcribed tale first appeared in Popular Romances of the West of England: Or, The Drolls, Traditions, and Superstitions of Old Cornwall (1865) and, afterward, wound its way into The Haunters & the Haunted: Ghost Stories and Tales of the Supernatural (1921), an interesting mishmash of ghostly fiction and folktales. Couch tells us that Dodge was kind and well respected, albeit eccentric. He lived in a time when ghosts “had more freedom accorded them, or had more business with the visible world, than at present, and the parson was frequently required by his parishioners to draw from the uneasy spirit the dread secret which troubled it.” But, along with dealing with sorrowful spirits, the vicar could handle the sinister ones, too. “Mr. Dodge had a fame as an exorcist,” says Couch, and it is his talents in this area that make up the heart of Couch’s tale.

Indeed, according to a letter sent to Dodge, the phantom of “a man habited in black, driving a carriage drawn by headless horses” had been terrorizing a moor in Lanreath. As any occult detective worth his (protective circle of) salt would, the vicar takes the case. All I’ll say about this story is that it opens with those in need calling upon the ghost-busting services of Dodge — and ends with Dodge proving to be the right man for the job.

An illustration for “The Spectral Coach” from Legend Land (Great Western Railway, 1922) p. 36.Were Dodge’s Theatrics a Diversion?

An illustration for “The Spectral Coach” from Legend Land (Great Western Railway, 1922) p. 36.Were Dodge’s Theatrics a Diversion?Couch says that Dodge “was fearless in reprehending” smuggling among his parishioners, However, it has been implied that the parson’s nighttime battles with demons and their kin were theatrics intended to frighten the locals away from his own smuggling operation. At least, Charles G. Harper suggests as much in his 1909 book, The Smugglers. Who knows? All I’ll say is that I prefer Dodge as a ghostbusting superhero than as a charlatan of the cloth.

Even so, Dodge’s legend makes great occult detective material. And he’s even found his way from folklore to folk music! Here’s a song by John Langford about Reverend Dodge:

Parson Ruddle of Launceston: Ghost-Quieter

The Reverend John Ruddle (?-1699)Harassed by a Ghost

The Reverend John Ruddle (?-1699)Harassed by a GhostIn 1665, in Cornwall, a boy named Sam was harassed by a ghost as he walked to school. He recognized the ghost as being that of Dorothy Dingly (or Dingley or Dinglet), a young woman from the area who he remembered had died and was buried. The phantom wouldn’t let poor Sam be, gliding up to join him even when he tried to take a different route. Sam’s parents — who scoffed at the notion of ghosts — took the problem to a visiting minister, bidding him to investigate the validity of Sam’s story. After confirming Sam really was being visited by a ghost, the Reverend Mr. Ruddle (or Rudell or Rudall) went to work. He did his homework, he revisited the specter, and after he shared some conversation with her, spectral Dorothy went away, never to return.

This story has taken various forms over the years, and a debate arose over who first brought it before the reading public. The first time it was published appears to be as part of Duncan’s Campbell’s Pacquet (1720), where it’s titled “A Remarkable Passage of an Apparition.” The piece was then tacked onto a re-release of The History of the Life and Adventures of Duncan Campbell. In the 1800s, some contended that Daniel Defoe was the author, the same man known for having penned Robinson Crusoe and the ghost story,”The Apparition of Mrs. Veal.” Others disagreed, arguing that Ruddle himself wrote the narrative. (Sure enough, the piece uses a first-person narrator named Ruddle — but Robinson Crusoe uses a first-person narrator named Crusoe, and that’s widely deemed to be a work of fiction.)

A Parable About BelievingThis early version of the tale is less an edge-of-your-seat ghost story and more a parable about believing in the Unseen. Sam is derided by his skeptical family and friends until Ruddle investigates and proves he was right all along. Ruddle himself becomes a believer in ghosts rather than starts out as one. You see, he wasn’t summoned because of his reputation for banishing otherworldly entities, which would make him predisposed to believe in such things. No, Sam’s parents asked for Ruddle’s help solely because they heard him give an impressive eulogy. And keeping the tale’s emphasis more on teaching a moral lesson and less on thrilling its audience, Ruddle’s final confrontation with the ghost is lackluster and disappointing: “[A]fter a few words on each side, it quietly vanished, and neither doth appear since, nor ever will more, to any man’s disturbance.” The narrator never reveals why Dorothy returned from the dead or how he convinced her to go away. Nope. Just some indeterminate chitchat.

The next time the story appeared in print appears to be in C.S. Gilbert’s A Historical Survey of the County of Cornwall. Gilbert tweaked a few things. Sam’s family is given the name “Bligh, from Botathan,” for instance, and the haunted field changes from “Higher-Broom-Quartils” to “Higher Broomfield.” Ruddle’s name becomes “Ruddell” here, and “Dingly” is now “Dingley.” Otherwise, the minister’s credentials are as unimpressive and the story ends as disappointingly.

A More Gripping Version AppearedIt took another vicar, Robert Stephen Hawker, to spice up the tale and fill in several details, and he did so by claiming to have come across a “diurnal” (a fancy name for a journal) written by none other than Rudall. Yep. That’s how Hawker spells it. Titled “The Botathen Ghost,” this version appeared in Charles Dickens’ All the Year Round in 1867. Now, we might never know whether this “diurnal” thing was real or just a really imaginative ruse to turn the earlier transcribed folk tale into a much more gripping and proper Victorian ghost story. Not surprisingly, this is the version that often gets anthologized.

Robert Stephen Hawker (1803-1875)

Robert Stephen Hawker (1803-1875)Here, instead of an ordinary (albeit eloquent) guy who gets snagged into acting as ghost hunter, Rudall is described as “a powerful minister, in combat with supernatural visitations.” We get nice details on Dorothy’s ghostliness: “There was the pale and stony face, the strange and misty hair, the eyes firm and fixed, that gazed, yet not on us, but on something that they saw far, far away. . . .” While in the earlier version, the minister simply goes home where he “studied the case,” Hawker has Rudall arrange an audience with the bishop to solicit “license for my exorcism.” I like to picture that as being similar to a driver’s license — but, you know, more for driving away demons and such. Wearing a special ring, this Rudall draws a protective circle and pentagram in order to banish the ghost. Now, we’re flirting with the methods of a duly licensed occult detective!

Hawker also explains why Dorothy D. haunted the field. Rudall learns that she had harassed poor Sam because ghost law stipulates that a specter “must seek a youth or maiden of clean life, and under age, to receive messages and admonitions.” It seems Dorothy needed Sam to convey a message to his own father, a message about “a certain sin.” The juicy details are left to the Victorian reader’s imagination, but Rudall takes it upon himself to confront “that ancient transgressor,” who consequently shows “horror and remorse” and “entire atonement and penance.” Afterward, telling Dorothy that her mission is fulfilled, Rudall “did dismiss that troubled ghost, until she peacefully withdrew, gliding toward the west.” Hmm, maybe there was another sinner in Canada with whom she had business.

Fact or Fiction?Despite the likelihood that Hawker’s discovery of the diurnal was a ploy to give the folk tale the crisp details and satisfying closure of a literary short story, some readers believed it wasn’t fiction at all. Among them was the Reverend R. Wilkins Rees, who wrote a fascinating article titled “Ghost-Layers and Ghost-Laying,” printed in The Church Treasury of History: Custom, Folk-lore, Etc. He summarizes (at length!) Hawker’s story, and then discusses some of Ruddle’s fellow ghost-busting clergymen who also lived in Cornwall at about the same period. Thomas Flavel is an interesting one, and there’s the fiery Richard Dodge. The latter is already listed in my Ghost Hunter Hall of Fame.

And now John Ruddle is in that Hall, too. Eager to become even more confused by what is fact and what is fiction in the muddle of Ruddle? I recommend Alfred Robbins’ article in The Cornish Magazine and S. Baring-Gould’s chapter in his Cornish Characters and Strange Events.

A Ghost Hunter Exemplar: Antoinette du Ligier de la Garde Deshoulières

Antoinette du Ligier de la Garde Deshoulières (1638-1694)Matter and Material Causation

Antoinette du Ligier de la Garde Deshoulières (1638-1694)Matter and Material CausationAntoinette du Ligier de la Garde Deshoulières, an important French poet and philosopher, appears to have been very interested in revealing the natural causes behind what seems to be supernatural or spiritual. At the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, John J. Conley explains that Deshoulières “employed verse to argue that natural causes can adequately explain such apparently spiritual phenomena as thought, volition, and love. In metaphysics, Deshoulières argues that the real is comprised of variations of matter and that material causation adequately explains observed changes in the real.”

Deshoulières held that instinctual behavior explains human behavior much more than many of us like to admit, and that “[m]aterial organs, and not the occult powers of a spiritual soul, produce such human phenomena as thought and choice,” according to Conley. In other words, we humans are less ghosts in machines and more, well, simply machines.

An Anecdote Arises in the 1800sThis begins to explain a popular anecdote about Deshoulières that spread during the first half of the 1800s. This is an era when much was written about ghostly encounters being attributable to mistakes or delusions, not to spirits of the departed returned to the physical realm. One can see this lesson dramatized in fictional form in Washington Irving’s 1820 tale “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” in which the superstitious Ichabod Crane is scared out of town presumably by Brom Bones masquerading as the Headless Horseman. The Deshoulières anecdote presents the flip side of Ichabod’s story: the poet visits a castle, bravely insisting on spending the night in its room reputed to be haunted. There, she calmly discovers a perfectly natural reason — matter and material causation — underlying the haunting. It turns out the “phantom” was only an inquisitive dog. The tale’s status as fiction is barely debatable due to the silly, canine explanation for the events that utterly horrify the gullible lord and lady of the castle. The narrative serves as a parable rather than as history.

The earliest version of this tale that I’ve managed to unearth, titled simply “Madame Deshoulieres, the French Poetess,” appeared in the December 6, 1817, issue of The Literary Gazette. There, Deshoulières’ ghost hunting adventure is introduced as an example of “intrepidity and coolness which would have done honour to a hero.” The title was changed to “The Ghost Discovered” when retold in an 1818 issue of The Repository of Arts, Literature, Fashions, Manufactures, &c. and changed again to “Seizing a Ghost” when it became part of The Percy Anecdotes, compiled by Joseph Clinton Robertson and Thomas Byerley (as Shoto and Reuben Percy) and published in 1820.

The Anecdote LingersI’ve located a few re-tellings of the adventure in later publications, too. In 1853, the story became part of a longer article on Deshoulières in Sarah Josepha Hale’s Woman’s Record; or, Sketches of All Distinguished Women. As late as 1867, the fable of courage surfaced in a weekly journal titled Our Boys and Girls, where it became a key part of May Mannering’s “A Ghost Story.”

Much like “The Barber’s Ghost,” another instructive ghost hunter tale about a skeptic who debunks an alleged haunting, the anecdote about Deshoulières had lasting appeal with readers in the early 1800s. As suggested above, I don’t know for sure if her visit to a castle and debunking of its ghost ever actually happened. Even if it had, print re-tellings of the narrative transformed Deshoulières into a kind of ghost-hunting folk hero.

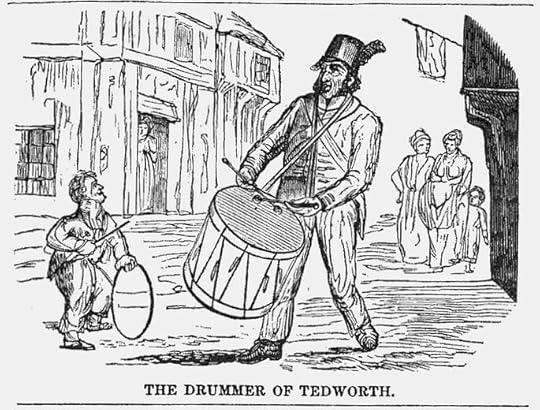

Joseph Glanvill and the Drummer of Tedworth: Setting a Foundation for Ghost Hunters

Joseph Glanvill (1636-1680)The First Psychical Researcher?

Joseph Glanvill (1636-1680)The First Psychical Researcher?Some say that Joseph Glanvill was the very first psychical researcher. It’s tough to settle on such historical firsts, so it might be safer to simply say that Glanvill was a man who believed witches and ghosts were real, and he chronicled accounts about them from this perspective. His own investigation into the Drummer of Tedworth haunting reads surprisingly like ghost hunts that would follow. In fact, his handling of this famous case, which involved poltergeist-like manifestations at the Mompesson house in the early 1660s, stands as a model — a foundation — for ghost hunts from the Cock Lane investigation conducted in the 1760s to several more from the Victorian era, roughly another century after that.

The Drummer of Tedworth is a tale often told as a true ghost story, popular enough to have appeared in everything from Horace Welby’s Signs of Death and Authenticated Apparitions (1825) and a journal titled Legends and Miracles and Other Curious Stories of Human Nature (1837) to the Dublin University Magazine (1848) and Henry Addington Bruce’s Historic Ghosts and Ghost Hunters (1908). Those are just a few of the sources I consulted to put together my own version of the tale.

A Begger with a Fake PermitIt seems that, in England of the 1660s, a beggar needed a permit to beg. William Drury was such a beggar — or, perhaps, more of a busker in that he wandered around and beat a drum in hopes of eliciting a handout or two. But he shouldn’t have wandered to Tedworth (now Tidworth) because it was there that John Mompesson checked Drury’s permit and found it had been forged. His fake permit and drum confiscated, Drury was run out of town. The drum ended up at Mompesson’s house.

About a month later, weird stuff started happening at that house. Disembodied shouting. Hard knocking on doors where nobody stood. And inexplicable drumming! Worse yet, Mompesson’s children started to be targeted. The blankets were ripped off of them while sleeping. A weird scratching could be heard near their beds. Then ghostly lights were seen. Then a human-shaped form with glowing red eyes!

Glanvill InvestigatesThis went on for over a year. Enter Joseph Glanvill, Chaplain to Charles the Second and Rector of Bath Abbey Church. Glanvill had fashioned himself into a specialist on supernatural phenomena. He tells of his visit to Mompesson’s house in a book titled Saducismus Triumphatus (1681), which is designed as much to prove the reality of witches as ghosts. (My American readers might recall that the horrible events in Salem, Massachusetts, were sparked in 1692. Witches were as much a source of panic in England in the late 1600s.)

Glanvill writes that, on his first night of keeping watch at the haunted site, he heard “strange scratching” as he ventured toward the bedroom of the haunted children. He confirmed that the children couldn’t have been responsible for the noise, and he checked around the bed. “So that I was then verily persuaded,” he explains, “and am so still, that the Noise was made by some Dæmon or Spirit.” After half an hour of scratching, the noise turned into heavy panting — so heavy it shook the room! Glanvill searched for a dog, a cat, “or any such Creature in the Room” — but there was nothing. A linen bag moved. Again, no tangible explanation for it.

Moving to the room where the troubles were first noticed, Glanvill sleep well — until a loud knocking sounded. He asked who was there, but no answer came until he demanded, “In the Name of God who is it, and what would you have?” A stern voice answered, “Nothing with you!” In the morning, Glanvill was assured that no servant — indeed, no one at all — had been in that section of the house. The haunting even affected Glanvill’s horse, which had mysteriously grown lame and died shortly afterward.

An illustration from Legends and Miracles and Other Curious Stories of Human Nature (1837)

An illustration from Legends and Miracles and Other Curious Stories of Human Nature (1837)All of this seems to fall within the realm of spectral phenomena (well, except what happened to the poor horse), and Glanvill’s nocturnal vigil and search for physical explanations followed — or, I should say, helped establish — standard ghost hunting procedure. And wouldn’t it be a nice and tidy ghost story if it was then discovered that the beggar William Drury had vowed vengeance against Mompesson on his deathbed shortly before the manifestations began?

If Not Drury’s Ghost, Then What?No, Drury was still alive when those manifestations occurred. He was even safe from being accused of somehow faking the haunting because, during part of it, he could verify his location: the Gloucester goal, accused of theft. In fact, it was while in jail that Drury heard of the weird events in Tedworth — and his pride ruled his good sense. He bragged that he had bewitched the man who had taken his drum from him there. Indeed, this boast resonated with the day that Mompesson, responding to loud noises near the children, heard a phantom voice cry, “A witch, a witch!” Eclipsing the charge of thievery, Drury was now tried for practicing witchcraft!

He got off easy, though. Glanvill reports: “The Fellow was Condemn’d to Transportation, and accordingly sent away.” In other words, Drury was once again driven out — this time, out of England. The manifestations in Tedworth seem to have stopped around this point. However, Glanvill ends the story with a more dramatic flourish. He says that, not only did great storms brew as Drury’s ship sailed off, but the man himself was revealed to have owned “Gallant Books” that once belonged to “an old Fellow, who was counted a Wizard.” Glanvill’s version of the tale — a primary source for the many retellings that followed — ends with the ghost hunt becoming a witch hunt.

Athenodorus and the Ghost Who Waited

Athenodorus (1st Century BCE)

Athenodorus (1st Century BCE)In one of his letters, Pliny the Younger (61/62 CE-c. 113 CE) recounts an anecdote about Athenodorus, a legendary ghost hunter. Pliny describes this figure as “a philosopher” and seems to be referring to an actual person, but we don’t know exactly who that person was. There are two main contenders: Athenodorus Cananites, who was born around 74 BCE and died in the year 7 CE, and Athenodorus Cordylion, who was an old man in 47 BCE. It’s easy to simply say they were both from the 1st century BCE. In addition, both were born near Tarsus (in what is now Turkey), and both traveled to Rome. Both were philosophers of the Stoic school. You see why they’re easily confused.

If we’re right so far, Pliny was retelling a tale set around 100 years earlier, making his “Athenodorus” something like Robin Hood: possibly based on some actual person, but so tarnished — or should I say so polished — by oral tradition as to have taken on a life of his own. There appears to be no evidence that the ghost hunt ever really happened, and when I say Athenodorus was “a legendary ghost hunter,” I mean that literally.

While Pliny’s transcription of the legend is brief, it’s also a fascinating glimpse into how Classical Rome understood ghost hunting techniques and the characteristics of an effective ghost hunter. Lately, I’ve been looking at English translations of that chunk of Pliny’s letter. William Melmoth appears to have offered one of the earliest translations in 1747. This translation was later “revised” by F.C.T. Bosanquest, and you might find that a bit easier to read. Alternatively, you might try John Delaware Lewis’s 1879 translation.

In a nutshell, the story goes like this:

There was a spacious house in Athens, one said to be haunted. Residents had heard chains clanking and saw the phantom of a withered old man. The sightings only occurred at night, but often enough to have driven away those residents. The house stood empty for a long time, no one wanting to rent or buy it — even at the cheap rate at which it became advertised.

But then Athenodorus strutted into town. Intrigued by the low price, he asked around. He learned about the ghost. That only made him more intrigued, and he agreed to take the place. On his first night, Athenodorus began his investigation. Knowing that expectation exerts a powerful influence — that humans tend to find what they want to find — he kept himself busy with something other than ghosts. He focused, instead, on a writing project.

And he stayed focused on his writing even when he started to hear the clinking of chains. The sound came nearer. And nearer. Still, Athenodorus riveted his attention to his work. Once the rattling arrived at his door, he finally glanced up to see the specter of the elderly man! That ghost was motioning for the philosopher to follow him.

Here’s where Athenodorus shows his resolve. He neither crumbled in fear nor fled from the house. He did not freeze in place. He didn’t even get up to follow the ghost! No, cool as can be, Athenodorus raised his hand and gestured for the ghost to be patient. Wait there a bit. Let me finish writing down this thought. Athenodorus went back to his pen and paper — well, his stylus and tablet.

None of the translations I found confirm this, but at this point, I like to picture the apparition tapping its phantom foot and crossing its ethereal arms.

At last, Athenodorus turned back to the ghost, followed it to a spot where the figure melted into the ground, and then marked that spot. The next day, he persuaded the officials to dig there. A skeleton wrapped in chains was found. With due ceremony, those bones were reinterred elsewhere, and the house was never again troubled by ghosts.

There’s the feeling of a parable, a fable with a moral, here. Yet there’s more than one lesson to be learned:

Don’t automatically fear ghosts — maybe they’re asking for help.A good ghost hunter resists expectation (which is especially tough if you’ve spent $300 on ghost-hunting equipment!)Don’t hesitate to ask a ghost to wait — they tend to have flexible schedules.While rummaging through ghost-hunting chronicles from many centuries later, I’m occasionally reminded of the ending of Athenodorus’s adventure. Skeletal remains, lending credence to and explaining an alleged haunting, show up again in the Hinton Ampner case of the mid-1700s. In 1904, a skeleton was reported to have been discovered under the cabin of the Fox Sisters, and since the bones appeared about 50 years old, some saw it as supporting the sisters’ 1848 claim regarding a murdered peddler making contact with them there. In his 1918 book, The New Revelation, Arthur Conan Doyle concludes an anecdote about a poltergeist investigation he participated in by saying, “Some years afterwards, … I met a member of the family who occupied the house, and he told me that after our visit the bones of a child, evidently long buried, had been dug up in the garden.” Most likely, there are additional ghost hunting chronicles that end with the discovery of a backyard burial.

Are these hints that the legend of Athenodorus was influencing ghost hunting chronicles during those centuries when Pliny’s letters were being translated into English? Well, the legend also appears in this magazine article about ghosts, in this liberal retelling of the tale, and even in this version for children. Presumably, it appeared elsewhere, too, so it wasn’t known only to select scholars in the 1700s and 1800s. It might have had some influence on how Hinton Ampner, the Fox Sisters’ home, and Conan Doyle’s own case were remembered.

On the other hand, there might be a line of disgruntled ghosts waiting to have their hidden bones unearthed. Regardless, Athenodorus stands tall (when he gets around to standing up) as a model for ghost hunters, not just in ancient Rome, but also during the Victorian period and, to some extent, still today.

UPDATE: In this post, I dive deeper into reports of skeletal remains found at sites said to be haunted.

December 30, 2022

Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit: The Mechanic Shops in Decatur, Alabama

Beware of Women with Red Shawls

Beware of Women with Red ShawlsI’ve been collecting old newspaper ghost reports long enough to consider where each new one falls between journalism and folklore. I recently found a 1905 article titled “Railroad Men Saw Ghost.” Since it’s about a team of train mechanics in Alabama fleeing from an “old hag with a large red shawl wrapped around her head,” I felt as if I had something leaning hard toward legend instead of fact. I then discovered that, sure enough, books from that period reveal similar figures in Celtic folklore, the red shawl being shorthand for WATCH OUT!

Once upon a time in Ireland, a person could hire someone to pray for, say, a good crop or a desirable spouse. One lazy, disreputable member of these “professional prayer-men” found himself stalked by “a horrible old hag,” whose “head was wrapped up in an old red shawl.” Things turn out unexpectedly well, however, after this women is revealed to be a magically disguised, benevolent herbologist who loves this jerk for no known reason. Across the Irish Sea, in days of yore, Welsh children were ever on the lookout for witches and hightailed it when spotting any “aged woman, with a red shawl on, for they believed she was a witch, who could, with her evil eye, injure them.” Down in Cornwall, there was a legend of an old woman, “wrapped in a red shawl,” who magically prevented people from drawing water from a well each night. You see, that old woman was actually “the ghost of old Moll, a witch who had been a great terror to the people in her lifetime, and had laid many fearful spells on them.” Of course, in many traditional stories, red is symbolic — a color often signaling danger — and learning about these crimson-draped women has given me a new appreciation for Little Red and her riding-hood.

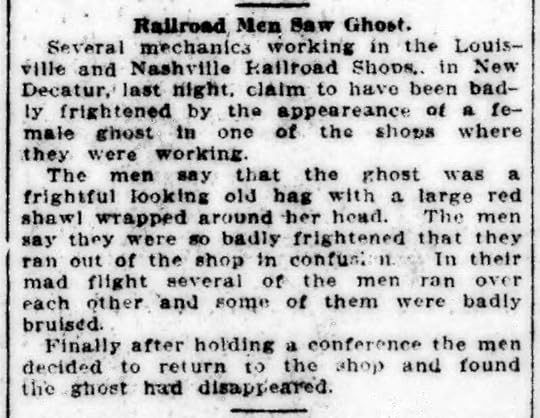

Did the Alabama Mechanics Have Celtic Roots?Let’s look at that 1905 article:

From the December 24, 1905, issue of The Montgomery Advertiser, an Alabama newspaper

From the December 24, 1905, issue of The Montgomery Advertiser, an Alabama newspaperThis was published on Christmas Eve, and I can’t help but think that some sweet grandma, wearing a seasonal babushka, was graciously offering the men cookies. And those bumbling idiots wildly misinterpreted her intensions. I haven’t found anything beyond the article itself to explain what made the mechanics react so strongly to what they had seen, but — if there’s any truth at all to the report — they might have been raised on folktales of witchy women in red scarves.

Now, let’s assume there was something truly paranormal wandering the grounds…

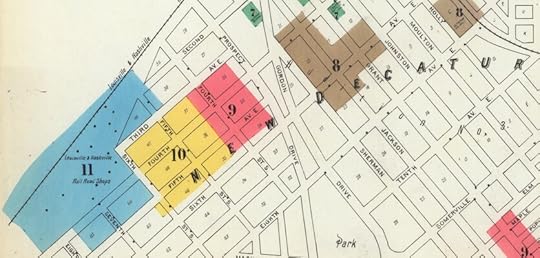

Finding Where the Railroad Shops Once WereWhile I couldn’t find out anything more about the otherworldly encounter, there’s good information available to locate the grounds where it allegedly happened. The Alabama town of New Decatur, as it’s identified in the article, is now simply called Decatur. A map published in 1903 clearly marks the grounds of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad shops. They were on the blue section of the map below. Well over a century later, the streets remain almost exactly the same, but the old map is at a particular angle. A helpful spot for orientation is the meeting of Third Avenue and Sixth Street, southwest of Delano Park. You can find it on the Google map.

This detail of the 1903 map gives the Louisville & Nashville Railroad shops the number 11 and color blue.

This detail of the 1903 map gives the Louisville & Nashville Railroad shops the number 11 and color blue.The area remains mostly industrial. Exactly where those skittish men had worked long ago is probably impossible to specify today, but ghost hunters might have some fun wandering that “blued” stretch of north-south Fourth Avenue (between east-west Sixth and Eighth Streets) in search of a ghostly crone in a red scarf. If you’re especially lucky, she might share some Christmas cookies with you!

If that doesn’t happen, Decatur seems like a lovely place to visit. Train buffs will be especially drawn to its beautiful historic depot, which now serves as a railroad museum. This depot was built in 1905, the same year the article was published. Hmm.

— Tim

Discover more “Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit” at the page forAfter the End of the Line: Railroad Hauntings in Literature and Lore

December 28, 2022

There’s No Good Reason for You to Read This Year-End Review

This is one of those year-end “here’s what I accomplished” things. It’s traditional, I guess, but it’s also self-indulgent. Don’t get me wrong — I enjoy these. But I see no good reason why you would. That notwithstanding…

Brom Bones Books released two books this year. The first was Certain Nocturnal Disturbances: Ghost Hunting Before the Victorians. My inspiration came from the Ghost Hunter Hall of Fame, which began with mostly Victorian inductees, such as Catherine Crowe and William Howitt. Of course, these folks are very important to the history of ghost hunting, since they set the stage for Cambridge’s Ghost Club and then for the Society for Psychical Research, which in turn signaled a shift toward studying hauntings and other paranormal subjects with academic rigor. But my research kept nudging me to look earlier and earlier to learn about equally important figures such as Antoinette du Ligier de la Garde Deshoulières and Samuel Johnson. When I realized there was enough pre-Victorian material to do so, I went ahead and wrote my first book-length history. It has quickly become one of BBB’s bestsellers.

This year’s second book is a significantly revised, pretty darned new edition of an anthology I created for another small press many years ago. Retitled From Eerie Cases to Early Graves: 5 Short-Lived Occult Detective Series, this book allows fans of supernatural mysteries to have handy the case reports of some of the best founding characters of that cross-genre. Specifically, it features series detectives who didn’t “survive” enough tales to fill a book by themselves. But Harry Escott, Jim Shorthouse, the duo of Alwyne Sargent and Jack Hargreaves, and others are certainly as worthy of being remembered and reprinted as are the likes of Flaxman Low or John Silence (all of whom appear in a long parade of supernatural sleuths in my Chronological Bibliography of Early Occult Detectives).

But perhaps I’m most proud of the second season of Tales Told When the Windows Rattle. Season One was mostly stuff I had already recorded, so it was pretty easy to complete. This season was all new dramatic readings, and I almost didn’t finish the final episode on time! But with coffee and fortitude, I posted my performance of Charles Dickens’ creepy classic “The Signal-Man” in time for Christmas.

I originally conceived of Tales Told as being a YouTube thing, but then I realized it could also be a podcast. As a result, I have no idea how many people follow it. Still, I started this season with about 30 YouTube subscribers. Last I looked, there are over 170. It’s certainly, ahem, modest by YouTube standards — but I’m counting it a rousing success. Especially when I picture the numbers in terms of theater seats. Which I do. Because that’s how I think.

What’s coming up in 2023? I honestly don’t know! Remember the thing about my thinking in terms of theater seats? Well, I’m itching to write a stage play, a project that’s not especially web-friendly. So I might be absent for long stretches of time. And I’ll probably post some new episodes of Tales Told Whenever I Feel Like It! In fact, a request has been made for my take on Poe’s The Raven, which I think is an excellent idea. And regarding books, I have plans for a series of novel reprints featuring charming criminals — think Raffles — that will steer Brom Bones Books and my research in a fresh, felonious direction.

But I have nothing solid to report. We shall see. For now, click on any of the pictures above to get to the corresponding page. For now, have a silly yet safe New Year’s celebration.

— Tim

December 22, 2022

The Second Season of Tales Told Ends with Charles Dickens Foreshadowing Thomas Hardy

This season of Tales Told When the Windows Rattle ends with “The Signal-Man,” one of Charles Dickens’ creepiest and most disturbing stories. Perfect for Christmas, right? Okay, maybe not. But I figure that other, more hopeful Dickens story get plenty of airplay this time of year. You know, the one about the gang of ghosts who prod that grumpy Gus to buy the Cratchits that gargantuan goose? Okay, maybe it’s a titanic turkey.

Charles Dickens (1812-1870)

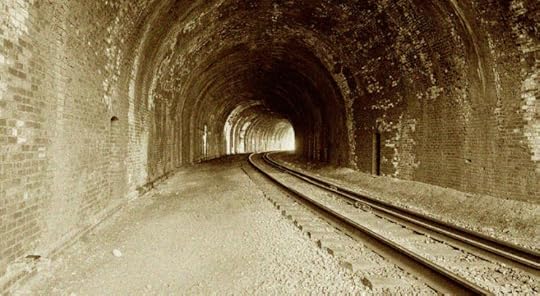

Charles Dickens (1812-1870)As I was recording “The Signal-Man,” which was first published in 1866, I was struck by how the title character has similarities to the stifled, stymied, smothered characters to come afterward from the pen of Thomas Hardy. Think of Hardy’s Tess in Tess of the D’Urbervilles (1891) or his Jude in Jude the Obscure (1895). First, Dickens puts his character in a bleak, narrow work environment:

On either side, a dripping-wet wall of jagged stone, excluding all view but a strip of sky; the perspective one way only a crooked prolongation of this great dungeon; the shorter perspective in the other direction terminating in a gloomy red light, and the gloomier entrance to a black tunnel, in whose massive architecture there was a barbarous, depressing, and forbidding air. So little sunlight ever found its way to this spot, that it had an earthy, deadly smell.

Then there’s the unrealized potential of the man himself:

On my trusting that he would excuse the remark that he had been well educated, and . . . perhaps educated above that station, he observed that instances of slight incongruity in such wise would rarely be found wanting among large bodies of men; that he had heard it was so in workhouses, in the police force, even in that last desperate resource, the army; and that he knew it was so, more or less, in any great railway staff. He had been, when young, . . . a student of natural philosophy, and had attended lectures; but he had run wild, misused his opportunities, gone down, and never risen again.

It’s almost no wonder that, when offered visions of an apparition seeming to signal future rail tragedies, he experiences them as incomprehensible fragments, infuriating teases of coming events instead of intelligible messages upon which he might act. He pleads:

[W]hy not tell me where that accident was to happen,—if it must happen? Why not tell me how it could be averted,—if it could have been averted? When on [the apparition’s] second coming it hid its face, why not tell me, instead, ‘She is going to die. Let them keep her at home’? If it came, on those two occasions, only to show me that its warnings were true, and so to prepare me for the third, why not warn me plainly now? And I, Lord help me! A mere poor signal-man on this solitary station! Why not go to somebody with credit to be believed, and power to act?

Another title might have been “Tunnel Vision,” and I suspect that Dickens was implying that his solitary railway worker was far from alone in suffering from this condition. If I’m wrong, I can say with confidence that this piece says more about a life of dire constraints than one typically finds in a ghost story. As I ask in the introduction to my reading, is it really a ghost story at all?

I put a lot of “soundscape” behind my recording of “The Signal-Man” in the hope of making it a distinctive conclusion to Season Two. Give it a listen on the Tales Told YouTube channel, on the season’s page here, or at your preferred podcast provider: Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, RadioPublic, Stitcher, or Anchor.

If you’ll excuse me, I now have to go think about what to read on Tales Told Whenever I Feel Like It!, the interim series.

— Tim