Tim Prasil's Blog, page 20

July 24, 2022

Minutes from the July 22, 2022, meeting of the Ghost Hunter Hall of Fame Inductee-Selection Committee

The Chair called to order the regular meeting of the Ghost Hunter Hall of Fame Committee at midnight on Friday, July 22, 2022.

II. Roll CallThe Secretary conducted a roll call. The following members were present:

Andrew Lang (1844-1912), Chair;

Vera Van Slyke (1868-1941), Vice Chair;

Tim Prasil (still living), Secretary; and

Elizabeth Gaskell (1810-1865), Treasurer.

Our fifth member was missing: Ambrose Bierce (1842-?), Publicity Officer.

The minutes of the last meeting were read. Ms. Gaskell moved they be worded in a manner more unnerving, if not alarming, and Ms. Van Slyke seconded. Upon revision, minutes of the last meeting were unanimously approved.

IV. Old Business“Given the historical emphasis we place on the Hall of Fame,” quipped Ms. Van Slyke, “all we ever do is old business.” The other members chuckled.

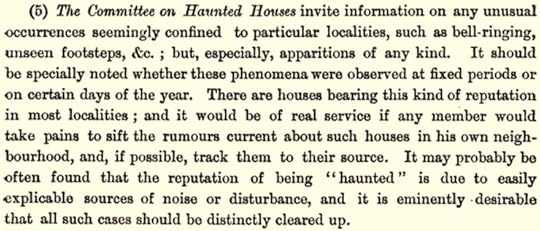

V. New BusinessMr. Lang made a case for inducting the Psychical Research’s Committee of Haunted Houses into the Hall of Fame. This committee was* among the first organized when the Society began in 1882. It appears to have lasted two or three years. His rationale was that, while their findings were disappointing, their punctilious methods were commendable. He submitted the attached, clipped from an early issue of the Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research:

Mr. Prasil explained that it’s certainly true the Committee for Haunted Houses was admirably judicious in assessing witness testimony. The same is true of their efforts to occupy and examine a reputedly haunted site for a long period, thereby improving upon the practice of single-night surveillance. However, he argued, such concerns can be traced back to ghost hunting prior to the Victorians. He asked the members to consider Charles Caleb Colton (1780-1832) for induction into the Hall of Fame. Colton repeatedly advocated securing sufficient evidence before announcing a final decision regarding the 1810 haunting in Sampford Peverell.

Ms. Gaskell replied, “I think you’ll find Colton stood in favour of the ghost.”

“I know he later earned that reputation,” explained Prasil, “but his published statements reveal him to be neither for nor against believing a ghost was involved. As I say, he repeatedly argued against arriving at any decision prematurely. While his main opponent, the publisher John Marriot, was quick to proclaim the whole thing a hoax, Colton called for keeping an open mind.”

Mr. Lang submitted, “If memory serves, the Sampford haunting was one of those ‘blame it all on smugglers’ cases so common in Cornwall and the West Country.”

Ms. Van Slyke added, “Tim, you must write a story about the spirits of Cornish smugglers haunting the people who have blamed Cornish smugglers for a haunting. You can put me into it, if you like.”

Ms. Gaskell inquired, “Vera? Are you fictional. Oh, forgive me — were you fictional?”

Ms. Van Slyke and Mr. Prasil exchanged a glance. The latter answered, “Only if my great-grandaunt invented her. I’ve found some indications that Vera might have really existed. Unfortunately, there’s barely a handful of vague indications.”

“Barely a handful of vague indications!” protested Ms. Van Slyke. “What am I, then? Am I one of the ghosts from that Christmas story by — by that fellow who wrote the enormous books?”

“Charles Dickens?” suggested Ms. Gaskell and Mr. Lang and Mr. Prasil.

“More to the point,” Ms. Van Slyke resumed, squinting at Mr. Prasil, “isn’t your recommendation of this Mr. Colford a ploy to sell your last book?”

“No! Not at all! It’s true that, uh, Colton and the, uh, Stamford case are the focus of the last chapter of Certain Nocturnal Disturbance: Ghost Hunting Before the Victorians, which is now available at Amazon. But does this make him any less worthy to be inducted into the Hall of Fame? I’d say it’s a sign of his importance to ghost hunting. By the way, click on the book cover below for more information.”

Mr. Lang motioned, “Let’s take some time to dwell upon our two nominees and finalize a decision at next month’s meeting.” Ms. Gaskell seconded.

VI. AdjournmentMs. Van Slyke moved we adjourn and go get some beer. The motion was unanimously passed.

*At this point in the meeting, Gaskell and Lang, being British, pointed out that the Committee of Haunted Houses should be recorded as a plural construction (e.g., “the Committee were…”) while Van Slyke and Prasil, both American, retorted, no, it’s a singular body (e.g., “the Committee was…). No agreement was reached after twenty minutes, so the issue was dropped.

July 17, 2022

Arabella Kenealy’s Lord Syfret: A Nebulous and Wayward Occult Detective

I’ve been working on the Introduction to Eerie Cases and Early Graves: 5 Short-Lived Occult Detective Series, and to doublecheck one of my points, I needed to reread Arabella Kenealy’s “Some Experiences of Lord Syfret” series. To be clear, this series is not a short one — and it won’t appear in the anthology — because there are eleven tales in all. That could fill a book all on their own.

As far as I know, no such book featuring all the Syfret adventures has ever been published (and the reason for that will probably become apparent as you continue to read this post). After the eleven tales appeared in Ludgate Magazine from June, 1896, to April, 1897, only seven of them were collected along with seven more, unrelated pieces in Kenealy’s Belinda’s Beaux and Other Stories (Bliss, Sands, 1897), a book that’s very tough to find.

At times, Syfret fits my criteria for being an occult detective pretty well. Or well enough. At other times, he does not at all. It is as if Kenealy were hoping to capture some of the magic of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes series, which had burst on the scene about ten years earlier. Unfortunately, Kenealy wasn’t able to pin down a fictional world or even a central character as distinctive, as consistent, or as clearly drawn as Holmes.

As a result, the series wanders, and Syfret remains obscure. Some stories involve the supernatural. Some are more conventional criminal mysteries. Some might be categorized as psychological mysteries, but some aren’t really mysteries at all. Some barely involve Syfret! Most of the stories are fairly good individually, but Kenealy’s series lacks the cohesion needed for a proper series.

Kenealy’s Lord Syfret

Kenealy’s Lord SyfretHere are my notes on each of the stories:

“The Haunted Child”: There’s a ghost and reincarnation, so the story is decidedly supernatural. Syfret solves the mystery — making this tale probably the one that most accomodates the occult detective genre — but he isn’t able to vanquish or appease the ghost. In terms of character, we learn that Syfret has an estate, and he says, “I was a magistrate. . . .” But there are almost no other details to describe him.

“In a Terrible Grip”: This is a bit like Agatha Christie’s 4:50 from Paddington in that Syfret sees something strange in a house that he passes on a train and then investigates it. It’s also a bit like Edgar Allan Poe’s “Berenice” in that teeth become a key motif. No supernatural elements appear, and again, we learn next to nothing about Syfret as a character.

“The Villa of Simpkins”: This is a howdunit murder mystery, and Syfret takes the lead in solving it. The tale opens with him experiencing a precognitive sense of tragedy regarding a particular house, but that’s as supernatural as this one gets. Again, Syfret is presented as the lord of a landed estate. And he dislikes publicity, and he has a yacht. I suppose that’s something.

“The Wolf and the Stork”: Syfret watches — and often tries to avoid — the main players in this story of a wealthy mother hoping to “marry off” her ditzy daughter. Nothing supernatural here, and no insights into Syfret’s source of income (though his wealth becomes apparent). He’s happy as a bachelor.

“Stronheim’s Extremity”: Again, Syfret assumes the role of an observant bystander during an incident involving a precious coin. Nothing supernatural. Nothing new about Syfret’s character.

“A Beautiful Vampire”: A nice, if somewhat predictable, tale of psychic vampire — so we’re definitely back on supernatural terrain. If you like this kind of thing, consider also reading Mary E. Wilkins Freeman’s “Luella Miller.” Again, Syfret stays at a distance in this adventure — Nurse Marian does the actual legwork — and the only new thing we learn about him comes when he says, “Among my clientèle I numbered several trained nurses.” But what does that mean?

“Honoria’s Hero”: Wow, here’s a confusing story! Uhm, as far as I can tell, there are crazy people doing crazy things and criminals trying to do criminal things. No supernatural.

“Prince Ranjichatterjee’s Vengeance”: One thing that can be said about Syfret’s character is he sure likes to pry into other people’s business. Here, he forces himself into a situation with an unhappy marriage and a missing/stolen diamond necklace. Be aware that Kenealy presents Indian and Jewish characters with very demeaning stereotypes. Nothing supernatural to see here.

“The Metamorphosis of Peter Humby”: This feels like it was never meant to be a Syfret piece. So far, Syfret has acted as narrator, but this one opens with third-person narration and then presents information that Syfret never could’ve known (such as specific dialog). Well into the story, a first-person narrator arrives. We presume that’s Syfret. Even then he doesn’t have much of anything to do with what happens. Maybe this tale is a spoof of realism, which is presented as turning ugliness into art — a very limited understanding of realism, indeed! Then again, this might be a generous interpretation.

“The Beautiful Mrs. Tompkins”: With supernatural and criminal mysteries long behind us, Kenealy presents what amounts to a tragic love story. Syfret only appears in a short preface, saying he got the manuscript from “a medical woman.” Oh, it’s a fine story, I guess — by itself. But it’s easy to assume that the author and the editor of Ludgate never should have agreed to a series.

“An Ogre in Tweeds”: Another tragic love story with no supernatural, no crime, and no mystery. As with “The Metamorphosis of Peter Humby,” Kenealy spotlights a physically ugly man. An interesting topic, perhaps, especially in a culture that put a high price on beauty — both female and male — but there’s no lesson in inner beauty here. Ugly men, says Kenealy, are ugly people. Wow.

As I say, Kennealy didn’t seem to have a very clear vision for Syfret, beyond his being a member of the gentry with time and money enough to poke around in other people’s lives. Unless there’s a shelf for Busybody Fiction, that’s a pretty wide umbrella, and it makes the Syfret series a tough one to box into any particular genre. At times, defying genre constraints is a good thing! I’m not so sure it is here, though.

Needless to say, I’m glad the series doesn’t fit into Eerie Cases and Early Graves: 5 Short-Lived Occult Detective Series. Not numerically. Not generically. Not in terms of consistency or quality. To find out what is in my next anthology, visit its page. It should be available well before Halloween.

— Tim

July 10, 2022

Edgar Allan Poe Sure Did Have an Ear! (Possibly, Two.)

I recorded myself reading Edgar Allan Poe’s “A Cask of Amontillado” for the Tales Told When the Windows Rattle series. Season One of this series is complete, and you can find the video version on the YouTube channel or those videos and the (downloadable) audio-only files right here. “Amontillado,” though, is part of an interim sub-series I’m calling Tales Told Whenever I Feel Like It!, which should help keep me occupied until Season Two of the regular series appears in mid-October.

Edgar A. Poe (1809-1849)

Edgar A. Poe (1809-1849)I especially like to record Poe’s tales because, so often, he tosses in important aural elements: the beating heart in “The Tell-Tale Heart,” the muffled meow in “The Black Cat,” or the tinkling bells of Fortunato’s jester cap in “Amontillado.” Clearly, Poe had an ear, and he knew a familiar sound in a frightfully unfamiliar situation can add a certain something to a creepy story.

If you’d like to hear what I mean, my take on “Amontillado” is up at YouTube. I also started a new page for the “Whenever” readings. I might be able to squeeze in one or two more of these before Season Two begins this autumn.

— Tim

July 3, 2022

Certain Historical Discrepancies; Or, Why I Wrote a Book About the Deep Roots of Ghost Hunting

History is full of surprises. I find it remarkable how similar paranormal investigations conducted in 2022 are to the one held by Athenodorus. The story of this ghost hunt had been circulating orally for about 100 years when Pliny the Younger (61–c. 113) jotted it down in a letter in the first century. As we do, the notion of ghost hunting at night — a practice I call “nocturnal surveillance” — appears to have been taken for granted.

Of course, Athenodorus didn’t have night-vision goggles or an EVP recorder. But even in our era of energy-sensitive equipment, we honor the long, long tradition of nocturnal surveillance. So did Antoinette du Ligier de la Garde Deshoulières (1636-1694) and Parson Richard Dodge (c. 1643-1746), who are said to have conducted ghost hunts. These three investigations are probably better understood as the stuff of legend rather than historical fact, since they involve actual people but the evidence of them going ghost hunting is dicey. However, much better documented investigations — conducted by the likes of Joseph Glanvill (1636-1680), Samuel Johnson (1709-1784), and John Jervis, 1st Earl of St Vincent (1735-1823) — also employed nocturnal surveillance. These investigators followed other standard investigative procedures when they performed witness interrogation and on-site inspection. The latter involves checking the pipes, the walls, and so on for ordinary explanations of what might have been mistaken for ghostly activity.

I only knew bits and pieces about the investigations conducted by Athenodorus, Deshoulières, Dodge, Glanvill, Johnson, and Jervis when I spotted people suggesting that the history of ghost hunting was relatively short. Some books and websites trace the tradition’s origins to the Victorians. To be sure, admirable work was done by members of the Society for Psychical Research, who conducted extensive witness interrogation, performed on-site inspection, and, like Athenodorus, rented houses reputed to be haunted and sat up for some nocturnal surveillance. Their work started in the 1880s, though, and there are additional reasons to assume that ghost hunting started at some point in the Victorian era (1837-1901).

Nonetheless, I muttered to myself, “Someone should write a book about pre-Victorian ghost hunting!” Then it occurred to me: I write books! And so Certain Nocturnal Disturbances: Ghost Hunting Before the Victorians was born.

This was a different kind of project for me. I’ve written several introductions to anthologies that trace the history of, say, sharing ghost stories by a fireside or speculating about life on the Moon. But I had never written a book-length history. I also trained as an Americanist, and this book demanded I time-travel to places such as Greece and France — and Cornwall, London, and Belfast. I think, though, that this just made me work harder, taking my time and doing solid research.

My goal — well, one of them — was to let people engaged in 21st-century ghost hunting know that they are part of a very long and honorable tradition. The paranormal investigators I discuss, whether their investigations are legend or historical fact, serve as examples to follow, as warnings of what to avoid, and as ancestors in spirit. If you’d like to learn more about the book, click here to get to its page. There, you can find my Introduction, links to online bookstores carrying it, and more.

— Tim

May 8, 2022

Historical Techniques in Ghost Removal; Or, How to Lay a Ghost the Old-Fashioned Way

Inching toward the completion of Certain Nocturnal Disturbances: Ghost Hunting Before the Victorians, I realized I’ve assembled a tidy library of historical sources on how to lay a ghost. The term lay here suggests setting an unquiet spirit to rest. These days, we might call this cleansing a haunted place. In especially ugly situations, the term exorcism might be more apt.

The oldest source I found is Henry Bourne’s 1725 book, Antiquitates Vulgares; Or, The Antiquities of the Common People. This is a collection of what would come to be called folklore, recording a variety of popular customs and beliefs that were fading, if not already vanished. A chapter titled “The Form of Exorcising an Haunted House” details a week-long ritual, one involving daily prayers and scriptural readings led by a priest. After thoroughly relating the procedure, Bourne speculates that the reasoning underlying it “is that the Devil may be gradually banished.” He ends by arguing that it is “ridiculous to suppose that the Prince of Darkness will yield to such feeble Instruments as Water and Herbs and Crucifixes.” There’s some Protestant hostility toward Catholicism lurking here.

In 1777, John Brand reprinted Bourne’s book, adding his own commentary after each chapter. He called it Observations on Popular Antiquities, and following the chapter mentioned above, Brand says he has little to add. By this time, a wave of skepticism regarding ghosts was in full swing (and belief in witchcraft was considered by the majority to be a sorry thing of previous centuries). Brand’s few comments here reflect this attitude.

On a side note, in 1863, George Cruikshank reflected the mistaken view that people of the 1700s must surely have believed in just about anything: “The gullibility of the public was much greater at that time than now, and they would then swallow anything in the shape of a ghost.” In contrast, I have yet to find a historical period in which ghosts were anything other than a topic of debate. I also have yet to find a historical period that didn’t boast about being more enlightened than the ones before it. But I digress.

You’ll find a few comments on traditional ghost laying in Francis Grose’s A Provincial Glossary: With a Collection of Local Proverbs and Popular Superstitions, first published in 1787. In a section titled “A Ghost,” Grose looks at the topic with a bit of humor, saying that

there must be two or three clergymen, and the ceremony must be performed in Latin; a language that strikes the most audacious Ghost with terror. A Ghost may be laid for any term less than an hundred years, and in any place or body, full or empty; as a solid oak—the pommel of a sword—a barrel of beer, if a yeoman or simple gentleman—or a pipe of wine, if an esquire or a justice.

I suspect I’d wind up in a barrel of beer. Not that I’m complaining, mind you.

For a more cross-cultural look at such beliefs, take a look at the very interesting chapter titled “Ghost Laying” in one of the best books dedicated to ghostlore, T.F. Thiselton-Dyer’s The Ghost World, published in 1893. Many cultures hold that water can block ghosts, and some folks have said — perhaps, for the sake of the story — that ghosts can be trapped in bottles. The relationship between ghosts and candles is explored, and as Grose does, Thiselton-Dyer points out that the Red Sea has long been designated as a good place to incarcerate spirits.

So far, these sources have been the work of folklorists compiling beliefs they treat as curious, enchanting, and quaint. The authors don’t suggest any of the techniques they discuss will actually rid a house of ghosts. Let me end, though, with a work that addresses ghost laying in the mind frame of an author who, in the early 1900s, believed it just might work. It’s a chapter titled “Haunted Houses and Their Cure,” which appears in The Coming Science, written by Hereward Carrington and published in 1908. By then, ghosts were being treated with more open-mindedness by “psychical researchers,” though plenty of skepticism still existed — even among the psychical researchers themselves! Carrington recommends getting a clairvoyant/medium involved, someone who can rally the assistance of other spirits to guide, if not drag, the ghost away from the physical realm.

Bits and pieces of these works show up throughout Certain Nocturnal Disturbances. As I say above, this book is advancing. Slowly. It should be out by summer. For now, you can find out a bit more about the book here. And that illustration on the cover was drawn by none other than Francis Grose!

— Tim

April 10, 2022

Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit: An Engine Shed in Chorley, Lancashire, UK

Suicide and Stones

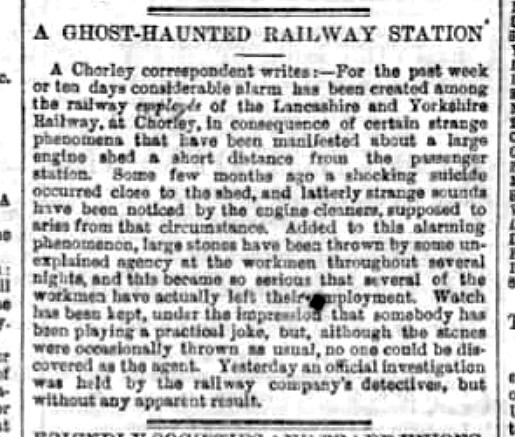

Suicide and StonesI’ve struggled to find an old railroad haunting in the UK that can still be visited, and this one is iffy. The case involves an engine shed in Chorley, Lancashire. We start with an article from the November 29, 1876 issue of The Manchester Evening News. (The news also spread to London and Wales.)

In the 21st century, ghosts seem to have put down their stones, but I found a surprising number of these nocturnal knuckleballers when working on Spectral Edition: Ghost Reports in U.S. Newspapers, 1865-1917. It’s interesting to come upon such reports in 19th-century England, too.

First, I wondered if I could find any earlier information about the suicide. I can’t be sure that the sad and grisly incident described below is the same one alluded to above, but it certainly might be. This comes from the February 12, 1876 issue of The Liverpool Weekly Courier.

The Ghostly Shed

The Ghostly ShedSecond, I tried to discover if the haunted engine shed still stands or, at least, determine where it had once stood. Well, the Chorley Historical and Archeological Society says the shed closed in 1922, but was it repurposed or completely demolished? I don’t know. I have a rough idea, though, of where it probably had been built. According to the website for White Coppice, Anglezarke, and Rivington, the Lancashire Union Railroad built such a shed in Chorley somewhere between Brunswick Street and Stump Lane. Assuming the names have remained the same (and assuming I’m reading the Google map correctly), those two east/west streets are about a fifth of a mile from each other. Friday Street connects them, running parallel and fairly close to the north/south train tracks. Portland Street also runs north/south — closer to the tracks — but it doesn’t reach from Brunswick all the way up to Stump.

Sadly, there’s a lot I don’t know in regard to visiting that haunted engine shed or hunting the ghost once said to lurk there. Maybe someone on that side of the Atlantic will have better luck. If anyone wanders along either Portland or Friday and spots what might’ve been an engine shed a century and more ago, please let us know. And especially let us know if, during your walk, you heard strange sounds or had to dodge stones thrown from the Great Beyond!

— Tim

Discover more “Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit” at the page forAfter the End of the Line: Railroad Hauntings in Literature and Lore

April 3, 2022

Nope, Not a New Early Occult Detective: Carlton Brand in The Vampire; Or, Detective Brand’s Greatest Case (1885)

The title page of The Vampire; Or, Detective Brand’s Greatest Case (1885), as reprinted by Strangers from Nowhere Press, includes the name of an essay placed after the novel. That essay is Gary D. Rhodes and John Edgar Browning’s “America’s First Vampire Novel and the Supernatural as Artifice.” Those last four words were my first clue that the novel’s central detective, Carlton Brand, would turn out to be what I’ve come to call a debunking detective. In essence, debunking detective work involves meddling kids pulling the sheets off ghosts to reveal imposters underneath. Think of Sherlock Holmes in The Hound of the Baskervilles, Hercule Poirot in “The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb” or Miss Marple in “The Blue Geranium,” and even Thomas Carnacki in “The House Among the Laurels.”

Unlike the others, Carnacki usually digs down to the case’s root and finds an otherworldly pest there, and mystery stories with such verified supernatural elements have guided my selections for the Chronological Bibliography of Early Occult Detectives. The list is plenty long as it is, but it would be downright exhausting — and never exhaustive — if I were to include debunking detectives.

SPOILER: Yep, Brand discovers that the villain in The Vampire was employing “the Supernatural as Artifice.” Therefore, nope, he does not join the sleuths on my list. (I’ll revisit this decision if, in his second or third greatest case, Brand proves a werewolf is a human who, on special occasions, sprouts impressive body hair and proceeds to impolitely gnaw on other humans.) Given that the title culprit is more faux vampire than a certified supernatural one, this novel might be framed as America’s First Vampiresque Novel. And it’s really more detectivesque than vampiresque. Instead of coffins and castles and crucifixes, the focus is on investigations led by characters named Blakely and Brace and Brand.

This is certainly not a negative criticism. Rhodes and Browning explain in their essay that a solid tradition of non-supernatural horror literature existed in the U.S. during the 1800s. One strain, they say, involves “real-life horrors,” and the other stirs up a specter of the supernatural “only to rationalize it” (pp. 249-250). The second strain prepares the way for The Vampire as well as for Holmes and his debunking colleagues. Rhodes and Browning go on to describe Brand as being “prescient of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, who would not appear in print for another two years” (p. 255). In this regard, The Vampire might be viewed as much closer to Conan Doyle’s Holmes tale “The Adventure of the Sussex Vampire” (1924) than to Bram Stoker’s vampire novel Dracula (1897).

If approached with this in mind, The Vampire becomes a fun, goofy, melodramatic, not-even-trying-to-be-realistic yarn one expects from a dime novel, which it originally was. In fact, I found it amusing to assess Brand’s performance in light of Sherlock-to-Come, a competition that I’m sad to say the American loses. Brand’s Plan A involves repeating Brace’s Plan A, which ended with that detective being murdered. Brand’s Plan B is to repeat Plan A, which ends with his being outmaneuvered by a character known as Miss Marita Madriea, a mysterious figure with a whiff of Irene-Adler-to-Come. Brand’s Plan C? Repeat Plan A. Ask Goldilocks: the third time’s a charm.

Meanwhile, poor Helena Porras is having a miserable first visit to the States, what with being drugged, abducted, nearly drowned, held for ransom, drugged, and abducted. I was glad to see that, though she’s stuck in the damsel-in-distress role, Porras still exhibits a glimmer of self-preservation agency.

My advice to interested readers, then, is to go in expecting a detective adventure. Expecting a vampire novel might lead to some disappointment.

[This paragraph is bracketed because it refers to the Advance Reader Copy I was kindly sent, one with a sticker saying the “product may not be final.” There are a fair number of errors in the text I read. The first page of the novel proper, for instance, mentions “A serious of mysterious deaths” when that should clearly read a series of mysterious deaths. I asked the publisher about the errors and was informed that leaving in the original flubs was intentional, allowing today’s readers to experience the work as readers did in 1885. That’s a bold editorial choice, especially since it goes unannounced. Thus, a character named Anchona is referred to as “Anehona” at one point, and another named Somerton as “Sornerton.” Minor stuff — barely a blip in reading comprehension. It’s a bit tougher to figure what goes unspoken when our bad guy steps up to a boat “and placing oars in its motioned Brand to embark.” A reader might raise an eyebrow when Brand is about to handcuff Madriea and she “extends her writits” — indeed, extending her wrists would seem more comfortable — or when that bad guy boasts “you will not tang me” rather than voice his views on being hanged. I’ll also toss in the several commas that appear as periods and the multiple times “he” shows up as “be.” I haven’t seen the original novel, but I’ve worked with enough old texts to suspect these last errors stem from the scanning/OCR process, and I hope they’re double-checked for the books available for purchase. Typos are gnats flying around readers’ eyes, and the fewer the better.]

Regardless of those tiny bugs, The Vampire is a fun glimpse at the cheap entertainment of an earlier generation. Personally, I don’t think the work adds much to the history of vampire literature. Call me a purist, but — much as I like my occult detectives to face the actual supernatural — I prefer my vampires to emerge at dusk, slake their unholy thirst for human blood (either politely or impolitely), maybe burst into flame in sunlight — and would it kill ya to climb down a castle wall like a lizard now and again? However, the novel is a noteworthy addition to the debunking detective tradition.

By the way, feel free to snoop around the Chronological Bibliography of Early Occult Detectives, if you have a few moments.

— Tim

March 27, 2022

A Return to Ballechin House (with New Old Research Sources Related Thereto)

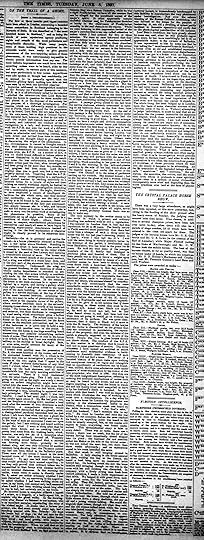

Ava Goodrich-Freer was inducted into the Ghost Hunter Hall of Fame quite some time ago. Though she conducted a number of ghost hunts, probably the most famous and controversial was at Ballechin House, called “Scotland’s most haunted house.” John Crichton-Stuart, 3rd Marquess of Bute — a.k.a. Lord Bute — rented the place for three months. Goodrich-Freer agreed to oversee its investigation during that time, and this involved several additional ghost hunters coming and going. Some of these visitors were members of the Society for Psychical Research. One visitor, presumably not a member of the Society, wrote a strong opinion piece on the affair for London’s The Times. This article dismisses the reality of the haunting itself, snubs Goodrich-Freer’s abilities, and lashes out at the Society.

My recent research has led back to Ballechin House, and I managed to find some tricky-to-access sources that might prove valuable to researchers in the quirky field of historical ghostlore. This isn’t everything I found, just what I feel is the most interesting and revealing.

We’ll start with the article that inflamed the controversy, written by someone identified only as “a correspondent.” The piece is designed to debunk the haunting, and the Society’s previous investigations are described as “perfunctory and absurd” for their short durations. (Ironically, the correspondent was himself only at the house a couple of days.) Though Lord Bute was smart to extend this probe “over a considerable period,” the correspondent suggests, he erred when assigning Goodrich-Freer to oversee things. Why was this a mistake? Well, “simply because she is a lady, and because she had her duties as hostess to attend to, she is unfit to carry out the actual work of investigating the phenomena in question.” Welcome to 1897. The correspondent goes on to attribute the manifestations — most of which were audible — to pipes, rats, noises carrying from adjoining rooms, and maybe a prankster. Superstition and similar factors explain the reports of visual phenomena. The piece ends with a scathing attack on the Society, which is accused of employing methods that are “extremely repulsive. What it calls evidence is unsifted gossip always reckless and often malignant; what it calls investigation would provoke contempt in Bedlam itself. . . .” Why a ghost hunt would prompt such a tirade will probably never be known.

“On the Trail of a Ghost,” Times [London], 8 June 1897, p. 10.

In the days to follow, this article was followed by a gush of letters-to-the-editor. One of the earliest is from Goodrich-Freer, who identifies herself as the hostess but who also signs the letter with “X,” her usual pen name. She defends the merits of the investigation and rebukes the writer for having exposed the name of the house. (There’s an editor’s note at the end saying the correspondent wasn’t told to keep the things confidential.)

X [Ada Goodrich-Freer], “To the Editor of the Times,” Times [London], 9 June 1897, p. 6.

A few days later, another letter from another visitor opens by denying that guests were requested to keep the name of the house under wraps. In the end, the writer pins the phenomena on fakery and hallucination, and anything leftover is a result of

earth tremors (Ballechin is only 20 miles from Comrie, the chief centre of seismic disturbance in Scotland), by the creaking and reverberations of an old and somewhat curiously-constructed house, or by some other simple natural cause.

A Late Guest at Ballechin, “To the Editor of the Times,” Times [London], 12 June 1897, p. 11.

And then The Times printed three letters — and in a single column — regarding the original article. The first is signed J.M.S. Steuart, the owner of Ballechin House, who says he wouldn’t have rented it to Lord Bute if he’d known it was to be Party Central for ghost hunters. The next is from a previous tenant, who denies having had any role in starting rumors that the house was haunted. The last is from someone who pooh-poohs the Society’s practice of hiding the identities of people involved in the cases they examine.

“To the Editor of the Times,” Times [London], 14 June 1897, p. 6.

By now the Society was attempting to minimize the damage. The Times printed secretary Frederick Myers’ letter responding to earlier letters. He mentions the many tests the Society uses on alleged hauntings, stipulating that it would have been “pedantic” to test for seismic activity. Regarding hiding identities, he says the members encourage their informants to go public — but they respect those informants’ wishes when they choose privacy.

Frederic W.H. Myers, “To the Editor of the Times,” Times [London], 15 June 1897, p. 12.

The Society also used its own publications to distance themselves from Ballechin.

“Ballechin House,” Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 8 (July, 1897) p. 116.

Not until 21 June 1897 did Times readers get a chance to hear from someone who was at Ballechin — not to investigate — but to work and, specifically, to butle. Harold Saunders explains that he had been at his assignment only a few days before maids and family members began reporting “ghostly noises.” Hesitant to think these sounds were anything more than hot-water pipes banging or, perhaps, branches hitting the house, Saunders did some of his own ghost hunting. Despite sitting up late across three weeks, he never heard a thing. Finally, though — he did hear a thing. It was a “tremendous thumping just outside my door.” He adds, “The same thing happened with variations almost nightly for the succeeding two months that I was there.” The experience was preceded by a chill, “like suddenly entering an ice-house,” and one night, Saunders heard “two distinct groans . . . like someone being stabbed and then falling to the floor.” When he finally went to bed, he felt his sheets being lifted. He attempt to light a match, but “my hand was held back as if by some invisible power.” Saunders ends by saying that, if the correspondent who had started the controversy “had stayed as long at Ballechin as I did and had some of my experiences, he would have a very different tale to tell.” (On the same page, prominent geologist John Milne affirms and develops the “seismic disturbances” theory postulated in previous letters.)

“To the Editor of the Times,” Times [London], 21 June 1897, p. 4.

Saunders provides an intriguing chronicle of Victorian ghost hunting conducted by someone who seems to have neither experience nor any previous interest in that pursuit. Altogether, these sources reveal how, at times, ghost hunting has been a highly debated endeavor. For more about Ballechin and more sources concerning it, visit my page titled “Ada Goodrich-Freer: Ghosts Gone Awry.”

— Tim

March 13, 2022

Aimless Thoughts on “Purposeless” Ghosts

I’m in the editing phase of Certain Nocturnal Disturbances: Ghost Hunting Before the Victorians, and I’ve been thinking about types of ghosts. There are headless ghosts, for instance, who sometimes ride headless ghost-horses and are sometimes attended by headless ghost-postillions. That comes up in the book. But one of my chapters is devoted to a baffling case from the late 1700s, a haunting in which the manifestations don’t point to a particular type of ghost exactly. No, those manifestations appeared unconnected to any history at the house. Whispery voices were heard, but so was a sort of music. Was there more than one ghost? Disembodied footsteps came and went. Doors slammed on their own. A pretty good ghost hunt was conducted, but the only “solution” was to recommend the residents move away. And they did!

I present this case as an early example of a “purposeless” ghost before such ghosts were officially recognized by those who dealt with such things. Let me explain. For centuries, ghosts seemed to have had a mission or some unfinished business. The purpose might be to reveal one’s murderer. To rectify an unceremonious burial. To ensure that the proper party inherit the family loot. There’s a whole list, and upon achieving the goal, the ghost typically found peace and “moved on.” Some nasty phantoms came back from the grave simply to raise a ruckus, and their stories usually end with being forced to move on via exorcism.

Eleanor Mildred Sidgwick (1845-1936)

Eleanor Mildred Sidgwick (1845-1936)In 1885, though, Eleanor Sidgwick found things had changed. After an exhaustive study of ghost reports submitted to the Society for Psychical Research — after winnowing down these hundreds of reports to the most reliable twenty-five — she found that ghosts don’t give a wooden nickel for tradition. They don’t have any particular fondness for old houses or for materializing on particular anniversaries. A history of crime or tragedy doesn’t appear to matter all that much. Indeed, Sidgwick reported:

[T]here is a total absence of any apparent object or intelligent action on the part of the ghost. If its visits have an object, it entirely fails to explain it. It does not communicate important facts. It does not point out lost wills or hidden treasure. It does not even speak. . . .

The purposeless ghost was netted and put on display.

A few years later, in a book titled Cock Lane and Common-sense, Andrew Lang differentiated what he called the “old-fashioned” ghost to “the modern ghost,” a.k.a. “the ghost of the nineteenth-century,” a.k.a. the purposeless ghost. Apparently paraphrasing Sidgwick’s report, he explained that this modern specter is much more shy:

He appears nobody knows why; he has no message to deliver, no secret crime to reveal, no appointment to keep, no treasure to disclose, no commissions to be executed, and, as an almost invariable rule, he does not speak, even if you speak to him.

Andrew Lang (1844-1912)

Andrew Lang (1844-1912)Lang knew that ghosts hadn’t changed overnight. In an article published about the same time as the book, he clarifies that there wasn’t a sudden loss of spectral purpose:

The more probable theory is, that the old believers in the old-fashioned ghost chiefly collected and recorded the more striking and interesting cases — those in which the ghost showed a purpose (as a few modern ghosts still do) — while these anecdotes were, doubtless, improved upon and embellished.

In other words, the shift probably says more about ghostologists than ghosts. (Owen Davies dives a bit further into this point on pages 8-9 in The Haunted: A Social History of Ghosts.)

The upshot? What’s my purpose for this post? Hmmm, guess what… Well, maybe it’s just to report that Certain Nocturnal Disturbances is progressing nicely.

— Tim

February 20, 2022

Not Everything Is Ghosts — I Also Write Little Plays and Stuff

I just submitted an original script to a local short-play festival, one that raises money for a variety of charities. While the festival has had to contend with and accommodate Covid, it hopes to return this year in a way that approximates what it once was. Writing scripts for them lets me exercise my writing muscles in an interesting and helpful way.

This got me thinking about my Writer’s Résumé over in the About section here. Toward the bottom, I list my “Performance” pieces, meaning my scripts that have been produced for audio, video, and stage. The audio and video works are available online (and I provide links thereto), but why include the stage performances? Folks can’t time travel to watch them, so why mention them? Well, because I had the honor of having them produced — that’s why…

My portrait for a curious website called Sad Playwright. Rest assured, the defacement depicted here is “theatrical.”

My portrait for a curious website called Sad Playwright. Rest assured, the defacement depicted here is “theatrical.”Still, what if I posted those scripts? Then, at least, folks could read the stories and imagine how they might be performed onstage. And what if this led to one being produced somewhere new? Well, wouldn’t that enhance my résumé?!

That’s what I did. I posted my short-play scripts down at the bottom of my Writer’s Résumé page. Enjoy, if you’re into that sort of thing.

— Tim