Tim Prasil's Blog, page 19

October 16, 2022

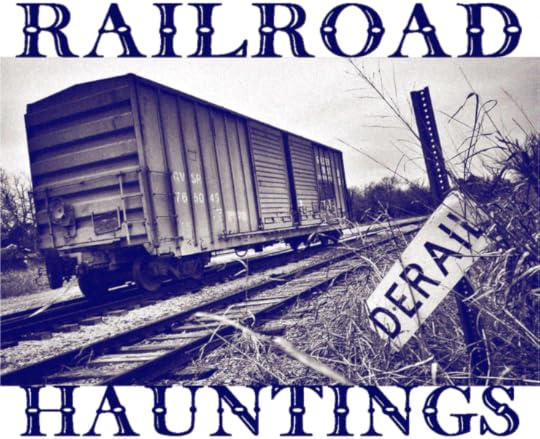

Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit: A Station-Master’s House in Chollerford, Northumberland, UK

The Persistency, The Pertinacity

The Persistency, The PertinacityThe haunting of a station-master’s house in Chollerford, England, seems to have been fairly well examined. That is, if one trusts an article in the January 10, 1891, issue of The Shields Daily Gazette and Shipping Telegraph, which takes its information from another newspaper. The article is slightly tricky to access — and tells a great story — so I’ll tack the whole thing up here:

A series of station masters heard the unaccountable rattles, footsteps, and scraping. Unnamed others knew of them. Spiritualists were intrigued enough to hold three séances. And those Spiritualists’ findings were convincing enough that the most recent station master dug up a garden in search of bones! Rarely do these old reports describe this much activity being ignited by a haunting. Indeed, it had become famous enough that an article on the ghostlore of England’s northern region points to “the scare at Chollerford” as an example of how belief in such matters persists.

On a side note, let me add that — from Athenodorus to the Fox Sisters — substantiating spectral manifestations by uncovering skeletal remains is something that recurs suspiciously often in allegedly true ghost stories. I discuss it in Certain Nocturnal Disturbances: Ghost Hunting Before the Victorians, but remind me to blog about it, too, some day.

The Station’s Name Was ChangedIn 1891, it might’ve been easy for the passengers traveling northwest on the Border Counties Section of the North British Railway to have mistakenly detrained at Chollerford Station, when they should have waited for the next one, named Chollerton. In 1919, our haunted station was renamed Humshaugh Station, presumably to make things less confusing.

According to Bradshaw’s Monthly Railway and Steam Navigation Guide (1862), a passenger could detrain at either Chollerford or Chollerton.

According to Bradshaw’s Monthly Railway and Steam Navigation Guide (1862), a passenger could detrain at either Chollerford or Chollerton.Luckily, Humshaugh Station and the house attached to it still exist, and this page provides plenty of details and photos. Among those details is the location of the place: “East side of Military Road B6318 at the end of Chollerford Bridge over the River North Tyne.” According to this other site, it’s now a private house, which might make ghost hunting there complicated — unless the owner would love to allow such a thing!

Even if plans for a ghost hunt are thwarted, Chollerford seems well worth a visit. It’s steeped in history, and I’m talking Roman Empire stuff along with a battle against the Welsh in the 600s. There’s a handy hotel beside the bridge that leads to the once-haunted site. (That hotel has a nifty story attached to it, too.) Please leave a comment if you go for a visit or if you know anything more about the historic town, its vanished railway, or its lingering ghosts.

— Tim

Discover more “Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit” at the page forAfter the End of the Line: Railroad Hauntings in Literature and Lore

October 12, 2022

Lucky 13: From Eerie Cases to Early Graves Is Now Available

I’m pleased to report that the thirteenth volume published by Brom Bones Books is now available. It’s also the sixth in the Phantom Traditions Library. Titled From Eerie Cases to Early Graves: 5 Short-Lived Occult Detective Series, this new book opens with Fitz-James O’Brien’s two Harry Escott tales, includes similar series characters from Arthur Machen and Algernon Blackwood, and closes with Allen Upward’s five adventures featuring clairvoyant Alwyne Sargent and realtor Jack Hargreaves. (Well, actually, there’s an appendix presenting an 1893 essay that looks at cross-cultural beliefs about getting rid of ghosts!)

As far as I can tell — and don’t quote me on this — the Sargent and Hargreaves series has never before been published in its entirety in book form. Originally, it had been published monthly in Royal Magazine, and I’ve seen one or two of the stories included individually in occult detective or ghost story anthologies. I think the stories really work best together, since Sargent and Hargreaves improve as their investigations as they go, Sargent’s use of her psychic powers takes a gradual toll, and a significant relationship develops between the two.

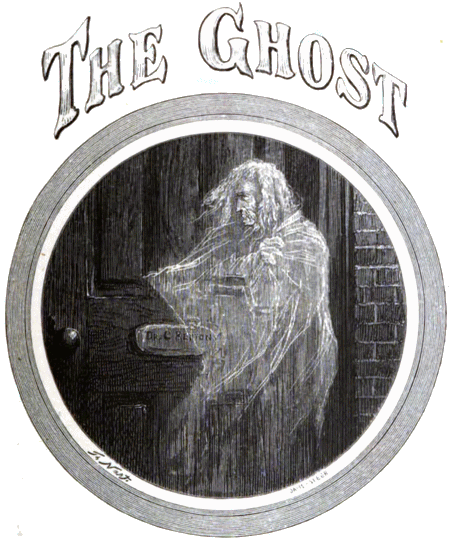

An illustration from the original publication of “The Tapping on the Wainscot,” the second Sargent and Hargreaves adventure.

An illustration from the original publication of “The Tapping on the Wainscot,” the second Sargent and Hargreaves adventure.I must make clear, though, that From Eerie Cases to Early Graves might remind some stalwart fans of occult detective fiction of a similar book I edited for another press, an anthology that is no longer in print. I see this as a much improved second edition of that earlier volume. I dropped some of the weaker, very short-lived series, and I added two series that I think those fans will much better appreciate.

You can see which characters are included on the webpage for this new book. There, you can also read my introduction to get a good feel of the thing and to maybe learn a few things about the history of detective fiction and series characters in general.

— Tim

October 9, 2022

“Were Christmas Ghost Stories a Thing in the U.S. during the Victorian Era?” Reconsidered

A few weeks ago, I attempted to answer to the question: “Was sharing ghost stories part of Christmas customs in the U.S. during the Victorian Era?” Elizabeth Yuko explains that this British tradition “was not one that really caught on” stateside. In my post, I explain that, while I found nothing to suggest that ghost stories were specifically a Christmas thing here in the States, there is some evidence of such tales being told — frequently by the fire — during autumn and winter.

Now, I should say that my evidence came primarily from works of fiction published in the 1800s, and that’s an imperfect mirror on real life in that century. I suppose diary entries or published memoirs from the period would better serve the purpose. Still, it’s tough to find that autobiographical stuff and relatively easy to find published fiction.

So let’s stick with fiction for the time being. Shortly after my post appeared, I was contacted by Christopher Philippo, who’s been researching this topic much longer than I have. He says American fiction does offer ghosts glimmering with Yuletide tinsel. In one of our exchanges, he says such stories “aren’t anywhere near as common as British ones, but there’s definitely more than just a few.” He very kindly provided me with some examples, and I took a look.

American Imitations of English TalesWilliam Douglas O’Connor’s novella The Ghost: A Christmas Story (1856) is set in Boston, Massachusetts, specifically the ritzy Beacon Hill neighborhood. There, grumpy Doctor Renton comes home on Christmas, complaining about various topics, from women’s rights to poor people not being able to pay their rent. Indeed, a tenant of his arrives to beg him not to evict her, but the stern doctor harrumphs at her sad case. All the while, a scrubby ghost — the spirit of an idealistic friend named George Feval, who had died in poverty one Christmas — lingers beside Renton, struggling to exert his more merciful influence. It is, after all, the season of good will. Sure enough, Renton becomes infused with goodness and generosity by the end. Much as the spirit of Feval manages to reform Renton, the spirit of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol (1843) appears to exert a significant influence here, too, and one might see this work as O’Connor’s attempt to tell an American version of that famous story. Dr. Renton, in a Scroogesque mood, even says “Bah!” and “Humbug!” So, yes, an American ghost story for Christmas. But one still leaning pretty hard on English fiction.

The frontispiece from an 1867 reprint of O’Connor’s The Ghost

The frontispiece from an 1867 reprint of O’Connor’s The Ghost The next two stories are similar to O’Connor’s in that they exhibit American authors essentially imitating English ghost stories for Christmas. There’s Leonard Kip’s “The Ghosts at Grantley” (1875), which opens by constructing its haunted house not too far from London. There’s also John Kendrick Bangs’ “Water Ghost of Harrowby Hall” (1891), which is a bit trickier to pin down to a geographic setting. We learn, though, that the protagonist is unable to find anyone “in all England” to investigate a room where a very drippy ghost manifests every Christmas Eve. The authors are American. But these tales only suggest they acknowledge the custom of Yuletide ghost stories as an English one rather than attempt to Americanize it.

The Real and Sweet DealWe have more luck with Elia W. Peattie’s “Their Dear Little Ghost” (1898). Again, the location is kept vague, but we do read that the narrator is “called to the Pacific coast.” Something tells me we’re not in England anymore! Peattie is a writer I really should know more about. Like me, she was born in the Great Lakes region, lived in Chicago, and moved to the Great Plains. According to a website dedicated to her, “many agree that the stories that she wrote about the West are among her best.” Is “Their Dear Little Ghost” one of these? Maybe, but not necessarily. It’s set in an almost mythic and magical Anyplace, where living children go looking for fairies and dead children return from the grave, looking for Christmas presents. It’s very much a ghost story for kids. Or maybe for parents.

The illustration in Harper’s Weekly for Stockton’s “The Great Staircase at Landover Hall”

The illustration in Harper’s Weekly for Stockton’s “The Great Staircase at Landover Hall”Last, we have Frank Stockton’s “The Great Staircase at Landover Hall: A Christmas Story” (1898). The narrator is “up from Mexico” and the heirs of Landover Hall are “out in Colorado,” so we seem to have returned to the western states. This tale spotlights what Vera Van Slyke would call a “chatty phantom,” meaning a ghost capable of holding an extensive conversation with someone still breathing. In a nutshell, the ghost sets the narrator up with her great-granddaughter, who’s still alive, and the living two live happily ever after. Like Peattie, Stockton is working more for a sentimental sniffle from his reader, not a horrified shudder. Still, both works can easily be deemed American Christmas ghost stories published during the Victorian era.

Interestingly, Yuko includes this quotation from English professor Tara Moore: “American Christmas scenes and stories tended to be syrupy sweet.” Peattie and Stockton reinforce this idea, even though their stories are certainly well crafted.

Christmas Wrapping UpWhat do we learn from this? While the tradition seems not to have been widespread in mainstream American culture, it was on the cultural radar. And an American author could mix a ghost story with the sentiments of the season, swapping chills with warmth, to create an American cousin to the British Christmas ghost story.

Let me end by saying that Christopher Philippo edited an anthology of Christmas ghost stories that were originally published in the New World. It’s the fourth volume in The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories, and it goes well beyond what I’ve discussed here, encompassing a range of creepy and strange stories. You can also hear him chat about the same on the Weird Christmas podcast, hosted by someone going by the name of Craig Kringle. I cannot (and will not) say that this podcaster isn’t an elf.

— Tim

P.S. Oh yeah — my original post is here. And Tales Told When the Windows Rattle returns with its second season in a couple of weeks. I wouldn’t mind, not even a little bit, if you subscribed to the YouTube channel.

October 2, 2022

A Founding Occult Detective Author Was Reported to Have Returned as a Ghost!

Years ago, I proposed that occult detective fiction has much deeper roots than one would gather from the histories then being told by the few literary critics addressing the topic. In fact, following a tip from Nina Zumel, I realized Henry William Herbert’s 1840 novella “The Haunted Homestead” was pretty easy to classify as a work of occult detective fiction. It’s a quirky contribution to the cross-genre, to be sure, but it’s clearly a murder mystery spotlighting a semi-Sherlockian investigator and weaving in supernatural events to spark and propel the investigation. Did I mention 1840? That’s a year before the debut of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” which is sometimes named as the very first work of detective fiction! Granted, it’s three years after William Evans Burton’s “The Secret Cell,” which joins other works to seriously challenge that stuff about Poe inventing mystery fiction. But Herbert’s detective being decidedly American (while Burton’s is English and Poe’s is French) makes this author important not just for his place in occult detective fiction, but also for his place in detective fiction in general.

An illustration of The Cedars used as a frontispiece in the second volume of The Life and Writings of Frank Forester (Henry William Herbert), ed. David W. Judd (Orange Judd, 1882).

An illustration of The Cedars used as a frontispiece in the second volume of The Life and Writings of Frank Forester (Henry William Herbert), ed. David W. Judd (Orange Judd, 1882).Herbert, who often used the pseudonym Frank Forester, led an interesting life. But it’s his death in 1858 — and his reputed ghostly afterlife fifteen years later — I want to look at here. He spent his final days in a “cottage” called The Cedars in Newark, New Jersey. An 1867 source describes the house as “so thickly shut in by trees that it is invisible from the road” and as the place where Herbert had led “his almost hermit life.” The structure burned down in 1872, but it had been right next to Mount Pleasant Cemetery, and that’s still there. Apparently, the mercurial Herbert spent those final days in anguish, abandoned by the woman he loved. He took his own life.

Think of that. A secluded house. A cemetery beside it. An author who, on at least one occasion, wrote a ghost story. His suicide. It was almost inevitable that a story regarding the author’s own ghost would materialize.

And in May of 1873, that story materialized in the New York Herald. It’s a tale of a tipsy trio who said they had encountered a ghost and the reporter who conducted a ghost hunt to verify their claim. The less-than-reliable three went to nose around The Cedars, then in ruins due to the fire. There, they witnessed “a tall, shadowy man, who advanced toward them from the cemetery. . . .” The reporter then launched a follow-up investigation, maybe being a bit too eager to interview a ghost. Finding the “high-walled, cavernous room” where the three had had their odd experience, our correspondent settled down, “determined to await the appearance of the ghost.” After some time, there was “a shadow — quick, uncertain, but unmistakably an interruption in the [star]light. Another moment of breathless suspense and it had passed again, this time slower and more palpably.” After the third time this happened, the reporter went in search of answers. In the direction of the cemetery, a presence “like the white shadow of a tall figure” flitted by and drifted towards a shed. The reporter pursued, finding nothing in or near the shed to explain the vision. “It was not accountable on physical principles, for there was nothing tangible that could produce such an appearance,” says the journalist, who ends the article with the mystery unsolved.

Not surprisingly, such a hair-raising report also seems to have raised doubting eyebrows. The Herald ran another article the very next day. Along with the alleged spectral phenomena, it adds “lights [that] flit about the ragged walls” and “noises as of groaning and cries of distress.” Nonetheless, the initial reporter’s white figure is here attributed to another ghost hunter roaming around there that same night, and the unsettling interruptions of starlight are said to probably have been nothing more than passing clouds. This more cautious article ends with a wait-and-see attitude: “The place is invested with a mystery, and at some future night there may be truer apparitions of departed spirits in that vicinity than have been shown to wandering mortals.” Was a senior editor backpeddling after an eager cub reporter went too far? Hard to say.

All I can say is that I’m weirdly delighted by the notion of a founding author of occult detective fiction returning in ghostly form to the physical plane. Or, I guess, his having never left at all. New Jersey ghost hunters assemble! We need you to poke around Newark’s Mount Pleasant Cemetery in search of a tall phantom who just might be the troubled Henry William Herbert! Report your findings back here.

But to prepare, you can read this post about the author’s key place in occult detective fiction. If you have little interest in Herbert and more in those challenges to the claim that detective fiction starts with Poe, here’s another post about that.

— Tim

September 25, 2022

Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit: The Roundhouse in San Francisco, California

Technically, the roundhouse is in Brisbane — but it’s adjacent to the southern end of San Francisco — amid neighborhoods called Bayshore and Visitacion Valley (and, ahem, Sunnydale). It was constructed in the early 1900s, and the remains of it still stand. There’s an effort underway to restore it.

However, I suspect few people, even among the restorers, know that a phantom locomotive has been linked to the structure’s history. On May 10, 1908, The San Francisco Call published a full-page article on exactly that. The writer, F. Jay Cagy, uses as his focus the roundhouse’s watchman, a man named Michael Flaherty. According to Cagy, while Flaherty has never seen a spectral train at the site, “more than once,” he

has heard the rails click with approaching wheels, heard the weird warning of a ghostly whistle, . . . and, standing back from the roundhouse switch, has heard the phantom locomotive pass with a rush of wind and run straight on through the closed doors of the empty roundhouse, into its echoless interior.

Cagy uses this as springboard for other accounts of phantom locomotives that other trainmen claimed to have witnessed out west. There’s the late Pete Quinn. Quinn was the engineer in a long-distance passenger train, the No. 7, running through the Sierras and toward “Oakland Mole.” At some point, he spotted another train heading straight for him! He did his best to brake — but then he prayed for safety instead of jumping to it. “There was a sensation as of swiftly rushing air and the phantom locomotive passed through or over No. 7,” writes Cagy. After the bizarre experience, Quinn somehow knew the spectral train had appeared as a warning of something. Sure enough, upon investigation, he and the conductor discovered that a trestle bridge ahead of them had been washed out by storm higher in the mountains. Cagy’s source for the story? Flaherty, who had shared an engine with Quinn is earlier days.

Next, Cagy retells another story heard by Flaherty. It involves a Santa Fe railroad telegrapher, who witnessed a phantom locomotive “sent” to foretell and prevent an impending collision between a train carrying freight and one carrying 500 passengers. The article ends with a third tale, one more recent and closer to San Francisco. It involves yet another warning delivered by a phantom locomotive, this one prompting a trainman to stop his engine and, thereby, to save the occupants of an automobile that had wrecked on the tracks ahead.

Flaherty’s tales — or Cagy’s retellings of them — are too sketchy to locate where any of these three phantom trains were spotted. Indeed, it’s uncertain how much stock one should put into Cagy’s claim that Flaherty had heard a phantom locomotive pull into the roundhouse, especially when the reporter also says a visit from the ghost train is “anxiously desired at the new roundhouse.” Wait. So did Flaherty experience it or not? Or is this to say that the roundhouse workers hope a supernatural warning arrives before any disasters do?

One thing we know for sure is that the ruins are presently fenced off. Nonetheless, the creators of this well-done video suggest permission to explore it can be gotten from San Francisco Trains. Be safe, ghost hunters! And if you visit the roundhouse, please let us know if you spot either a phantom locomotive or, perhaps, a ghostly watchman named Michael Flaherty eagerly awaiting the arrival of one.

— Tim

Discover more “Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit” at the page forAfter the End of the Line: Railroad Hauntings in Literature and Lore

September 4, 2022

Were Christmas Ghost Stories a Thing in the U.S. during the Victorian Era?

In an essay called “The Christmas Dinner,” Washington Irving paints a nice picture of the Yuletide tradition of telling ghost stories by a fire. After feasting, Irving moseys to the parlor, where a group is gathered around the hearth. There, the parson relates “strange accounts of popular superstitions and legends,” focusing on a local legend about a stone effigy rising from the tomb and stomping around the churchyard. But Irving is relating an experience he had while touring England. Did a similar custom of sharing spooky stories at Christmas also exist in the U.S. in the 1800s?

In “How Ghost Stories Became a Christmas Tradition in Victorian England,” Elizabeth Yuko writes, “Although countless trends made their way from England to America during the Victorian era, the telling of ghost stories during the Christmas season was not one that really caught on.” Although “a few American writers” tried to import the custom, Yuko reports that folklorist Brittany Warman theorizes the American experience was too much about fresh beginnings to bother with musty old customs and raggedy old ghosts. “Another reason telling spooky stories never took off as a Christmas tradition in the United States,” adds Yuko, “was because it became more firmly established as a Halloween tradition, thanks to Irish and Scottish immigrants.” That makes sense. I grew up in Illinois, and sure enough, Halloween was the holiday for ghosts — and, of course, vampires, witches, and the usual assortment of unpleasant company. When it came to supernatural entities, Christmas was reserved for elves and angles.

This illustration by Edmond H. Garrett appears in

Snow-bound; A Winter Idyll,

by John Greenleaf Whittier (Ticknor and Fields, 1866). In his “Prefatory Note,” the New England poet mentions growing up hearing tales told by his parents on “long winter evenings” and his uncle sharing stories, “which he at least half believed, of witchcraft and apparitions.”

This illustration by Edmond H. Garrett appears in

Snow-bound; A Winter Idyll,

by John Greenleaf Whittier (Ticknor and Fields, 1866). In his “Prefatory Note,” the New England poet mentions growing up hearing tales told by his parents on “long winter evenings” and his uncle sharing stories, “which he at least half believed, of witchcraft and apparitions.” Nonetheless, as I search through ghost stories from the 1800s, I keep stumbling across evidence that fireside ghost-storytelling was once a part of mainstream, American culture. Perhaps, it was only in a minor way. Perhaps, it was more in rural than urban areas. Very likely, it was not linked to Christmas specifically. Returning to Irving, frightening tales told by the fire are spotlighted in “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” which is set not terribly far upriver from New York City. Irving says that, due to the high mobility of the American population, ghost stories were rare in the States, even in remote regions. They still flourished in Sleepy Hollow, though. First, Irving notes Ichabod Crane listening to the “marvelous tales of ghosts and goblins, and haunted fields, and haunted brooks, and haunted bridges, and haunted houses . . .” shared by the hamlet’s wives as they spun wool by the fire on winter evenings. Second, at Van Tassel’s autumn bash, folks “were doling out their wild and wonderful legends. Many dismal tales were told about funeral trains, and mourning cries and wails heard and seen. . . .” Finally, even Crane’s disappearance at the end inspires “a favorite story often told about the neighborhood round the winter evening fire,” one with supernatural spice added. So here ghost stories are shared in autumn and winter — but not linked to Christmas itself.

Both Irving’s travel piece and his fictional tale were collected in The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent., first published in 1820, before the Victorian era proper. Yuko names Irving, along with Nathaniel Hawthorne and Henry James, among those writers attempting to import the tradition. But let’s see what other American authors were doing.

In The Key of the Kingdom (1836), Franklin Langworthy mentions having listened to fireside winter’s tales, not Christmas ones: “We can remember the time when through the long winter’s evening we have sat around some neighbor’s kitchen fire, listening in breathless horror to tales of devils, apparitions, witchcraft and haunted rooms. . . .” (Remember that this kitchen fire would have burned in what looks like a very large fireplace, not on some dinky gas stovetop.) He next says that spreading such stories might’ve been okay in the era of “our pious forefathers, the puritans of New England,” but not in the “enlightened days” of the 1800s. What’s interesting here is the American ancestry along with the book’s title page showing it was printed and copyrighted in northern New York State. Add the fact that the same author went on to write a book about his traveling to and living in California. I can’t find much on Langworthy’s biography, but he seems pretty American.

Joseph Holt Ingraham’s “An Evening at Buccleuch Hall; Or, The Grenadier’s Ghost” (1842) is set in New Jersey and, as the title makes clear, there’s a ghost. Again, the season is winter when the fireside narration occurs, and helping set the mood, there’s also a thunderstorm. There’s nothing very specific in regard to the day, however.

More specificity arrives in one of my most interesting finds: “The Spectre Revels: A Tale of All Hallow Eve” (1860), by Washington D.C.-born E.D.E.N. Southworth. This is another piece of fiction — one set in the States and framed as a fireside ghost story — but it’s told specifically on Halloween! Indeed, a Scottish and Irish touch is found in characters named Patrick O’Donegan and the Ferguson family.

Captioned “Do, do, tell us a story,” this illustration appears in Harriot Beecher Stowe’s

Sam Lawson’s Oldtown Fireside Tale

s

(James R. Osgood, 1872).

Captioned “Do, do, tell us a story,” this illustration appears in Harriot Beecher Stowe’s

Sam Lawson’s Oldtown Fireside Tale

s

(James R. Osgood, 1872).None other than Harriet Beecher Stowe describes fireside storytelling in Massachusetts in Sam Lawson’s Oldtown Fireside Stories (1872), sketching it as an activity for “when winter came, and the sun went down at half-past four, and left the long, dark hours of evening to be provided for.” The narrator explains that, for lack of other forms of entertainment, “in those days, chimney-corner story-telling became an art and an accomplishment.” This introduces a story titled “The Ghost in the Mill.” Again, this is presented as more a winter than a Christmas thing — but it’s still presented as a part of American life once upon a time.

In Erskine M. Hamilton’s “A Legend of Van Duysen House” (1879), after Grandpa Van Duysen is asked for a fireside ghost story, he opts to tell a Revolutionary War adventure instead. The setting for the oral story is the same as the written one: “here in this house and neighborhood.” Since it’s about the American War of Independence, we can safely assume we’re on U.S. soil, maybe even the East Coast. We’re given a more precise time when Grandpa tells the story: New Year’s Eve, 1840. Interesting, interesting!

By 1887, war stories competed with ghost stories at the hearth. In History of Bucks County, Pennsylvania, editor J.H. Battle includes an anonymous poem. There, we read of “the winter wind” sweeping and a “crackling fire” being stirred. The poet continues: “And then the weird tales of ghosts, / Of heroes, and of mighty hosts / That met in battles afar.” As with Hamilton’s short story, the Revolution War is cited.

On the one hand, I’m sure there must be more examples out there. On the other, it’s tough to say how far we can apply evidence from fiction to real life. Still, it strikes me that — while it’s fair to say that fireside ghosts stories never mingled with Christmas in the States — it’s wrong to assume from this that no fireside ghost stories were told in American homes during the years when Queen Victoria sat on the throne. I strongly suspect they were! Sometimes on Halloween. Sometimes on New Year’s Eve. And sometimes simply whenever the weather was chilly enough to gather ’round a crackling fire.

For glimpses of the long, long history of this custom in the UK and the U.S., visit my page titled Fireside Storytelling Descriptions and Depictions TARDIS. Oh, and Season Two of Tales Told When the Windows Rattle will arrive in a bit more than a month. If you missed Season One or my short interim series, this page will help catch you up. That said, your subscribing to the Tales Told YouTube channel would be greatly appreciated!

— Tim

August 28, 2022

The Scarlet Pencil: Remapping Machen

Posts identified as “The Scarlet Pencil” chronicle my meandering through the misty and mysterious quagmire of editing anthologies for Brom Bones Books. As announced in my introductions to these volumes, I try to make the material less distracting to 21st-century readers by modernizing outdated conventions of written English — changing, for instance, “to-night” to “tonight” and “any one” to “anyone” — while also preserving of the charms and uniqueness of the original language. At times, this balancing act is easy. At other times, it’s tough, and I sometimes find myself having discussions with the authors’ ghosts, negotiating my decisions and hopefully receiving their chilly pat of approval.

Arthur Machen (1863-1947)

Arthur Machen (1863-1947)This week, I’ve been working on From Eerie Cases to Early Graves: 5 Short-Lived Occult Detective Series and, specifically, Arthur Machen’s short stories — or are they novellas? — featuring Mr. Dyson. An interesting problem has arisen, one mentioned by Cian Gill in the “Evil Fairy Folk: Arthur Machen’s Novel of the Black Seal” episode of his wonderful podcast Wide Atlantic Weird. Examining this story-within-a-story found in Machen’s novel The Three Imposters (1895), Gill points out that Machen’s setting has striking similarities to Caerleon, Wales, the author’s hometown. Oddly, Machen identifies this town as being — not in Wales — but in the west of England. Gill contemplates aloud:

I wonder myself if this was some sort of English versus Welsh thing that, at the time, in order to be published in London and be taken seriously, you had this expectation that the public were more interested in things that were English than were not.

About the same thing occurs in “The Shining Pyramid,” the story I’m editing. At one point, readers learn that children walk to and from school behind a main character’s residence. The children either start from — or attend school in — Croesyceiliog, a real town in Wales with a really Welsh name. Later, though, the setting is said to be in “this quiet corner of England.”

I imagine some people aren’t quite sure where Wales is in relation to western England. To help, I took a detail from a map I found in an 1894 book and did my best to put Wales is in red. If I goofed up, I trust my Welsh ancestors — if not cartography fans still living — will duly haunt me.

I imagine some people aren’t quite sure where Wales is in relation to western England. To help, I took a detail from a map I found in an 1894 book and did my best to put Wales is in red. If I goofed up, I trust my Welsh ancestors — if not cartography fans still living — will duly haunt me.As a test, I did some Googling. I tried to find the nearest English town to Croesyceiliog as the crow flies, and I settled on Portishead. The tykes would have to travel about 12 or 13 miles — or 19 or 20 kilometers — twice a day. Applying my own average of walking roughly 4 mph on a good day, those kids spent at least six hours of their own day traveling to school and back — and unless they caught a ferry, they’d probably be slowed down by swimming across Aber Hafren (aka the Severn Estuary). Silliness aside, the geography doesn’t make much sense. Machen is grasping the corners of a town easily identified as Welsh, dragging it east across the border, and spreading it back out on English land.

Or just as likely, the original editor of “The Shining Pyramid” performed this formidable act. Sometimes, a person might forget that fiction published in the 1800s often carries the stamp — or, hopefully, the gentle touch — of an editor. For instance, Arthur Edward Waite was the editor of The Unknown World, where Machen’s story was originally published in 1895. That source is tough to locate. Seriously, when I can’t find something at Google Books or the Internet Archive or HathiTrust or even listed on WorldCat, I shrug and start to look for a later source. I used a 1923 reprint of “The Shining Pyramid,” one edited by Vincent Starrett. Yes, I’m editing a probably-already-edited version of the tale, crossing my fingers that Starrett’s tweaking of his source for the story, if there was any tweakage at all, was minimal.

But what’s an editor living in a less Anglocentric time and place than 1800s London do about Machen’s specifying Croesyceiliog, which clearly suggests he wants readers to think Wales, in a text that then says England? If Gill is correct in his speculation that an author had to favor English settings to get published — or if Waite and/or Starrett went ahead and switched the setting for some similar reason — then wouldn’t it be wise to now change the setting to “this quiet corner of Wales” or, perhaps, “this quiet corner of Britain”? To make it make sense? Am I right here?

Well, as it stands now, that’s what I’ve done. But From Eerie Cases to Early Graves isn’t out yet. There’s still a month or so for me to change my mind. We shall see.

— Tim

August 21, 2022

Announcing the Tales for the Second Season of Tales Told When the Windows Rattle

This week, I finalized the schedule for the second season of Tales Told When the Windows Rattle. It’s a very ghostly season that will take listeners through several haunted houses, along a few stretches of haunted railroad, and backstage at a haunted theater. We’ll even meet a haunted escape artist. Here’s the itinerary:

October 21: A Victorian Ghost Hunt (Catherine Crowe)

October 28: “A Case of Eavesdropping” (Algernon Blackwood)

November 4: “At Ravenholme Junction” (Anonymous)

November 11: “The Ghost of Banquo’s Ghost” (Tim Prasil)

November 18: “The Story of the Green House, Wallington” (Allan Upward)

November 25: Another Victorian Ghost Hunt (James John Hissey)

December 2: “Under the Sheer Legs” (Henry Tinson)

December 9: “A Pot of Tulips” (Fitz-James O’Brien)

December 16: “Houdini Slept Here” (Tim Prasil)

December 23: “The Signal-Man” (Charles Dickens)

You see that I scheduled a spooky story by Blackwood for the weekend before Halloween — and a creepy story by Dickens for the weekend of Christmas. It just seemed right!

If you’re not familiar with Tales Told, please visit the viewing-or-listening-or-downloading page here.

— Tim

August 7, 2022

I Had a Good Week, This Last Week

This last week, I converted Certain Nocturnal Disturbances: Ghost Hunting Before the Victorians into a Kindle version for those who prefer a disembodied book about the deep history of specter stalking. You can read more about this book here — or head straight to Amazon for either the ebook or the paperback.

II.This last week, I posted my reading of “The Least Haunted House in Wales.” It’s an original tale that features William Hope Hodson’s great occult detective, Thomas Carnacki. I felt the ol’ boy needed to set aside his Electric Pentangle and enjoy a case that’s a bit less serious than those Hodson assigned him. My story is included in an anthology of new stories about this character: The Book of Carnacki the Ghost-Finder, published by Belanger Books.

Why did I set in Carmarthen, Wales? Why is the client, whose surname is Nicholas, a confectioner? Well, you see, I have ancestors who came from there and carried that name and had that occupation. Fans of Carnacki will probably know that the names Abner, Abigail, Abbott — and the fact that the wife/mother is off in Aberystwyth — is me having fun with Carnacki’s penchant for words such as “ab-natural,” “Ab-human,” and “Ab.” Is Taxman Bellow a spin on Flaxman Low? No! No, of course not! Weeeell, okaaaaaay…

My reading is an episode of Tales Told Whenever I Feel Like It, the interim series between seasons of Tales Told When the Windows Rattle. You can enjoy both series with video on YouTube. The audio-only is on Spotify, Google Podcasts, RadioPublic, Stitcher, and Anchor. Find the video and audio — and download the audio for offline listening — on this page.

III.Speaking of Tales Told, this last week, I scheduled the stories for Season Two. The ten episodes will be posted every Friday from October 21 to December 23. This season is devoted exclusively to ghosts, combining fiction with a dash or two of non-fiction. The authors include the likes of Algernon Blackwood, Catherine Crowe, and Charles Dickens. It’s the perfect stuff to listen to by a fire on a stormy night, be it Halloween, Christmas, or any time at all. (If you lack a cozy hearth and/or nasty weather, both are provided gratis in the video version.)

IV.And this last week, I gave From Eerie Cases to Early Graves: 5 Short-Lived Occult Detective Series a vigorous scrubbin’ — by which I mean a solid proofreading. I also secured the services of two first-rate proofreaders to proofread my proofreading. Then I’ll proofread their proofreading of my earlier proofread. One likes to be thorough.

I think this anthology will be a very good addition to the Phantom Traditions Library. Read all about it here. I’m almost certain it’ll be available two or three weeks before Halloween. Maybe even earlier.

It was a good week, this last week.

–Tim

July 31, 2022

Another Precedent for Crocker Land; Or, What If Peary Wasn’t Lying?

Scroll down the page for Phantom Island at Wikipedia, and you’ll find a very blunt, very incriminating description of Crocker Land: “A hoax invented by Arctic explorer Robert E. Peary to gain more financial aid from George Crocker, one of his financial backers.” A year or two ago, I became intrigued by — not just Crocker Land — but the history of 1) Arctic explorers claiming to have spotted land in the distance, 2) that reported land making its way onto an official map, and 3) that land later being revealed as non-existent. My doing so made me less convinced that Peary had invented a hoax.

One of my reasons is that, even after Peary knew he wasn’t going to get any more funding from George Crocker, he advocated a “wait and see” attitude regarding confirmation of the land he had seen. He maintained that stance even after an expedition found no physical trace of Crocker Land where he had reported it be — only a distinct and persistent mirage of land there. In others words, Peary’s alleged motive for lying had vanished and he had been handed an easy way out of his alleged lie. Why, then, didn’t he shrug his shoulders and admit he — like others before and after him — had been the victim of an optical illusion?

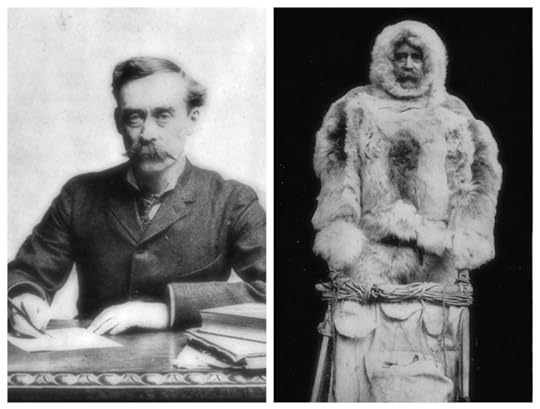

Robert Edwin Peary Sr. (1856-1920)

Robert Edwin Peary Sr. (1856-1920)It happens. The Arctic plays visual tricks. What looks like land is really just a mirage. As I say, there’s a history of exactly that. It was reported in 1849 that Captain Henry Kellett spotted what he called Plover Land. About five years later, though, Commander Rogers searched hard for it and concluded: “Kellett was misled by appearances.” In 1880, it was announced that Captain Keenan had spotted a significant land mass, which was named “Keenan Land” in his honor. Over twenty years later, Ejnar Mikkelsen reported on his study of where that land would be. It wasn’t there, and he attributed Keenan’s sighting to floating ice that, “seen in a certain light, conveys the idea of distant land.”

Not long ago, I found yet another example of this, another sighting/mapping/disproving that nudges me toward thinking Peary simply made a mistake. It involves the Polaris expedition of 1871-1873. This journey is better remembered for the tragedy surrounding its captain, Charles Francis Hall, who died during the trip. There’s good reason to suspect he was poisoned by members of his crew! However, that crew also returned with claims about having observed a body of land, which they named President(‘s) Land. Though no one had actually stepped on this perceived chunk of earth, it became mapped.

Detail from “Map of the Smith Sound Route to the North Polar Sea” (1875)

Detail from “Map of the Smith Sound Route to the North Polar Sea” (1875)By 1876, however, the claim was disproved by Captains Nares and Stephenson during an expedition on their respective ships, Alert and Discovery.

That said, there are still very good reasons to be suspicious of Peary’s claim about Crocker Land. But there’s an important difference between suspicion and conviction. I’m hoping my “Charting Crocker Land” articles, which now include President Land, play some small role in making this point of history somewhat less certain.

— Tim