Tim Prasil's Blog, page 16

January 3, 2023

“The Barber’s Ghost”: Tracking a Ghostly Folk Tale in Print

A curious connection arose between my hunting for early occult detective fiction and my search for actual ghost reports that led to Spectral Edition: Ghost Reports in U.S. Newspapers, 1865-1917. The connection involves a tale titled “The Haunted Chamber.” This was published in The Waste Book, a journal printed in 1823 by “John Miller, Printer” from Providence (Rhode Island, I assume).

The tale is about a man who stops at a Massachusetts inn, hears that one of its rooms is considered haunted, and requests to stay in that room in order to debunk the rumors. The local legend explains that the ghost was a barber in life, and his spirit lingers to ask: “Do you want to be shaved?” Solving the ghostly mystery, the character then takes advantage of those who believe in the haunting by posing as the ghost to scare them. It’s fairly typical of an 1820s ghost story in that it urges readers to be skeptical about alleged hauntings. Think, for instance, of Washington Irving’s 1820 “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” in which superstitous Ichabod Crane is (most likely) bamboozled and scared out of town by Brom Bones. The moral here is that those who believe in ghosts can be easily manipulated.

The tale about the alleged spectral barber reappears in A Collection of Useful, Interesting, and Remarkable Events, Original and Selected, from Ancient and Modern Authorities, by Leonard Deming (Middlebury: J.W. Copeland, 1825). Though clearly the same story, it’s reduced considerably, and instead of being set in New England, it takes place in “one of the Southern states.” Furthermore, the traveler consents to sleeping in the haunted room rather than specifically requesting to do so, meaning he’s no longer a ghost hunter per se. Importantly, the title is now: “The Barber’s Ghost–A Fact.” In other words, it’s presented as if it really happened.

Yorkville Enquirer, July 31, 1889After the 1820s

Yorkville Enquirer, July 31, 1889After the 1820sIt next appears in an 1833 issue of The Literary Journal, and Weekly Register of Science and the Arts. The introduction reads: “The substance of the following narrative was given, several years ago, as a contribution to a periodical work. It has now been revised and in part re-written, by the author, for insertion here.” Unfortunately, that author remains anonymous.

The abridged version might have served as the source of subsequent reprints in newspapers — at least, until newspapers started taking it from other newspapers. The earliest I’ve found is in the May 23, 1840, issue of the Camden Journal, a newspaper from South Carolina. The story is now set “the upper part of this State,” which would mean South Carolina in this case, but when that phrase is repeated elsewhere, the story hits close to home with any reader anywhere.

For instance, when the story appeared in the January 30, 1841, issue of the Salt River Journal from Bowling Green, Missouri, the setting is again “the upper part of this State.” But this printing prepares readers to recognize its status as — if not outright fiction — then something that’s hardly hard news. It opens: “The following story is old but a precious good one. We laughed heartily over it ‘long ago,’ and presuming many of our readers never heard of it, we serve it up for their edification.” The amusing anecdote now feels less like “a Fact” and more like a tall tale one might hear at, say, the barber shop.

Even into the 1860sAfter an appearance in Gleason’s Literary Companion on (July 2, 1864), our spooky barber re-materialized in the Dayton Daily Empire on June 03, 1865. The setting returns to “one of the Eastern States,” but without the introduction that the Salt River Journal provided. A reader might have viewed it as a typical news article. The Cambria Freeman chose April 1st, 1869, to share the tale with its readers in Ebenburg, Pennsylvania. Despite it being April Fool’s Day, that introduction used in the Salt River Journal was included, too. And when South Carolina’s Yorkville Enquirer published it on July 31, 1889, the editor placed it in the Humorous Department column (as shown above.)

I very strongly suspect that many other newspapers ran the story throughout the 1800s and possibly into the 1900s. But this is enough evidence to see “The Barber’s Ghost” as a sort of tall tale transcribed, an American folk story passed around not only by word-of-mouth but via periodicals reprinting from other periodicals. In its wanderings, it often straddled the line between a factual news report and a humorous piece of fancy.

Those who wish to investigate the long life of this ghost story further might want to look at an academic article by Mac E. Barrick, titled “‘The Barber’s Ghost’: A Legend Becomes a Folktale” and published in Pennsylvania Folk Life (23.4 Summer 1974).

A Dispiriting Sport: James John Hissey, Frustrated Ghost Hunter

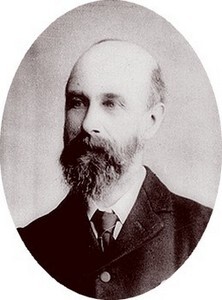

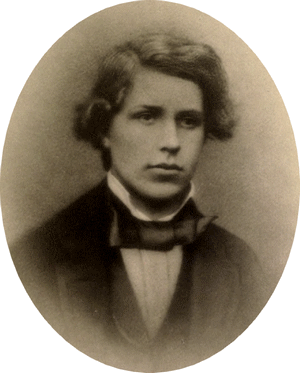

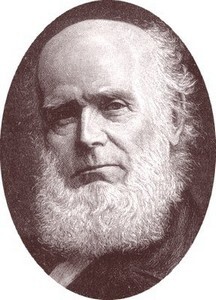

James John Hissey (1847-1921)Sightseeing with an Eye on Haunted Spots

James John Hissey (1847-1921)Sightseeing with an Eye on Haunted SpotsFrom the 1880s to around World War I, James John Hissey wrote fourteen books about his travels through Britain. Frequently, these travelogs include quick mentions of ghosts as the sightseer recounts local legends told in some of the spots he visits. But ghosts are mentioned so frequently throughout his books that Hissey seems to have been deliberately keeping an eye on haunted houses. Or haunted inns. Or haunted castles or haunted streets or haunted hills.

Indeed, Hissey claimed to be a ghost hunter — but a frustrated one because he never witnessed a ghost himself. The closest he came to a personal encounter with a phantom is discussed in The Charm of the Road: England and Wales (1910): “Hunting after haunted houses is in one sense a dispiriting sport, for though haunted houses abound, I never could run down a ghost; at least only once, and then it hastily ran away from me.” Staying at a house in Scotland, Hissey learned that a spectral figure was said to appear out in the yard during nightly prayers (his host being a strict Presbyterian). During one of those prayer sessions, Hissey “conveniently had a bad headache” and slipped outside to pursue the ghost. Sure enough, he spotted it! He says:

I saw a mysterious white figure coming quietly along; just when it had arrived between myself and the window I rushed at it with raised stick; I heard quite a human shriek and plainly saw two human feet beneath what I took to be a white sheet,—but, alas! I lost my balance and fell down to the bottom of the dry moat. I hurt myself somewhat, but so effectually did I scare that particular ghost, that he or she never appeared again, at any rate during my stay. ... And that is the sole outcome of over twenty years’ hard ghost-hunting.

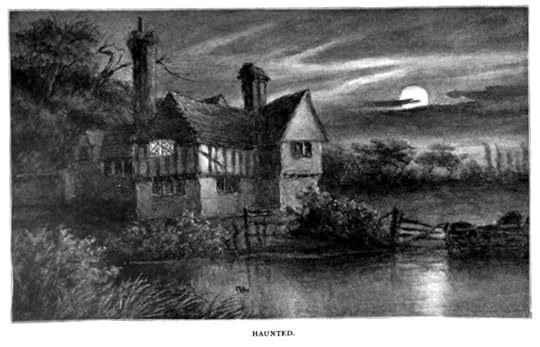

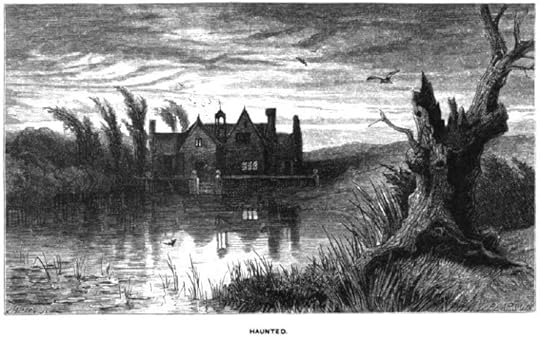

A GIFTED ARTIST, HISSEY DREW ILLUSTRATIONS FOR HIS OWN BOOKS. HERE ARE SOME OF THE SPOOKY SITES HE VISITED.A More Involved Investigation

A GIFTED ARTIST, HISSEY DREW ILLUSTRATIONS FOR HIS OWN BOOKS. HERE ARE SOME OF THE SPOOKY SITES HE VISITED.A More Involved InvestigationThis brief anecdote stands as one of the two records of Hissey’s overt ghost hunting that I’ve managed to find. Luckily, the other investigation is much more involved, filling about twenty pages and reaching from the end of one chapter to start of the next.The more detailed investigation appears in Over Fen and Wold (1898). Here, Hissey tells of his visit to Halton Holgate, near Spilsby, Lincolnshire.

He first presents two newspaper articles about a haunted farmstead there. Readers learn that the farmhouse was occupied by Mr. and Mrs. Wilson. The couple had been hearing strange knockings and other sounds, but it was the wife alone who spotted the phantom of a round-shouldered, old man standing at the top of the stairs one night. This apparition seemed to presage the next creepy event: the discovery of human bones under the floor of the house!

Inspired by these news articles, Hissey questioned the landlord of the inn where he had been staying in nearby Wainfleet. The innkeeper pooh-poohed the haunting, so the tenacious ghost hunter went to the source. Asking a villager in Halton Holgate the whereabouts of the haunted house, Hissey found his way there.

It Didn’t Look Properly Haunted“Nothing could well have been farther from our ideal than what we beheld; no high-spirited or proper-minded ghost, we felt, would have anything to do with such a place,” writes Hissey about seeing the farmstead. But the farmer living there appeared to be a straightforward and honest man. He retold the story related by the newspapers, and then Mrs. Wilson gave Hissey a tour of the place. She showed the staircase where she saw the “little, bent old man with the wrinkled face standing on top and looking steadily down at me.” Hissey saw the uneven bricks that marked where they had “found some bones, a gold ring, and some pieces of silk” buried under the floor.

In classic ghost hunter fashion, Hissey asked if he might be allowed to spend the night in the haunted room. Mrs. Wilson said no, though, explaining that they had promised a couple of London reporters the “first rights” to that experience. Hissey is left to lament:

I feel quite hopeless now of ever seeing a ghost, and have become weary of merely reading about his doings in papers and magazines. I must say that ghosts, both old and new, appear to behave in a most inconsiderate manner; they go where they are not wanted and worry people who positively dislike them and strongly object to their presence, whilst those who would really take an interest in them they leave ‘severely alone!’I read the entire section devoted to Hissey’s Halton Holgate investigation for Tales Told When the Windows Rattle. It’s available at YouTube, on the page here for the second season of Tales Told, and on several podcast platforms.

Many of Hissey’s books are easily found online, and they’re pretty charming. Still, readers should expect a lot of leisurely descriptions of perfectly natural landscapes, villages, and buildings — not a ghost hunter’s casebooks. Zero in on those pages that actually do discuss haunted locales, however, and one can easily get the impression that Hissey sincerely hoped to witness a ghost firsthand. He kept a gentle sense of humor about never having done so, but there’s something gloomy lurking under the humor that reveals his frustration.

William F. Barrett: A Solid Ghost Hunter

William F. Barrett (1844-1925)A Physicist Exploring the Borders

William F. Barrett (1844-1925)A Physicist Exploring the BordersBy trade, William F. Barrett was a physicist. He taught the subject at Ireland’s Royal College of Science, and his professional accomplishments earned him places in organizations ranging from the Royal Society and the Institute of Electrical Engineers to the Philosophical Society and the Royal Society of Literature. If you wish to get a sense of the state of physics at the close of the 1800s, you might take a look at Practical Physics: An Introductory Handbook for the Physical Laboratory (1898), which Barrett co-wrote.

However, Barrett is probably better remembered today for his explorations on the borders of the physical realm: telepathy, Spiritualism, even dowsing. In addition, he was a key figure in the founding of the Society for Psychical Research in both the UK and the U.S. Like his fellow scientists on both sides of the psychical pond, he was accused of gullibility — of being too eager to believe in the phenomena he was investigating. Nonetheless, such accusations seemed not to deter his desire to extend scientific study into these fringe subjects.

Barrett’s 1877 Ghost HuntTo this end, his chronicle of a ghost hunt he conducted concludes with a bit of a homily about how, despite living in an age of skepticism, reports of ghosts persist and how we should, at least, entertain the idea that such hauntings might be evidence of human spirit existing beyond the body. Published in the Dublin University Magazine, this chronicle is titled “The Demons of Derrygonelly” (1877). Despite the rather dramatic and alliterative title, Barrett describes ghostly manifestations that seem more the work of a poltergeist than a demon. Still, it’s a nicely written article, one that illustrates well the operations of a Victorian ghost hunter.

Barrett opens the article by describing how the ghost hunt was almost a secondary consideration of a man who invited him to explore the caves near Enniskillen, Ireland. From there, he and his host journey to a purportedly haunted cottage in Derrygonnelly. The two spend the night and are witness to a series of rappings and scratchings. Despite their best efforts, they are unable to trace the source of these noises.

The Knocking Phantom CompliedBarrett maintains a skeptical — or, at least, cautious — attitude as he scouts around for evidence of trickery or some other physical explanation for the noises. The most inexplicable experience of the evening is when he invites the phantom to knock a specific number of times. And it does so correctly! Even when the physicist spoke the number more quietly and more quietly, the phantom is able to show it understands. Barrett goes on:

At last, I mentally asked for a certain number of knocks: they were slowly and correctly given! To check any tendency to bias or delusion on my part, I thrust my hands in my coat pockets, and said, ‘Knock the number of fingers I have open.’ The response was at first merely a loud scratching, but I insisted on my request being answered, and to my amazement three slow, loud knocks were given, — this was perfectly correct.

Barrett says he was able to repeat the test a few more times, and each time, the ghost discerned and communicated the correct number of fingers.

The Loss of a Wife and MotherPerhaps more compelling is the story of the peasant farmer in whose cottage these noises had been heard for weeks. The manifestations, he explains, began after his wife died, leaving him with four daughters and one son. The ghostly activity seems not to be the dead woman’s spirit, though. Grieving, one senses, is a better explanation for the phenomena. Specifically the eldest daughter, Maggie, seems to be the catalyst for the poltergeist, particularly when she sleeps. “One morning,” the farmer explains, “we found fifteen or sixteen small stones had been dropped on her bed.” Meanwhile, the phantom also plays pranks on the family, such as playing hide-and-go-seek with their boots.

Barrett ends his narrative with neither a solution to the ghostly mystery nor a resolution to the poor cottager’s predicament. Instead, he ends with that plea for further exploration of such hauntings that I mention above.

Barrett’s Other Ghost HuntsBarrett conducted additional ghost hunts, some of which are noted in the “Hauntings and Poltergiests” chapter of his book-length survey titled Psychical Research (1911). His chronicle of a 1914 investigation struck me as material for very distinctive dramatic reading, and I asked some actor friends to join me in treating it as exactly that:

Similar to the 1877 case, Barrett ends this outing with the Unsubstantial remaining elusive and, well, unsubstantial. Nonetheless, he exhibited solid abilities in paranormal investigation and a solid track record in such endeavors.

Crane, McLean, and Le Conte: The 1874 Oakland Ghost-Hunting Committee

On April 23, 24, and 25, 1874, strange phenomena manifested at the house of Thomas Brownell Clarke. Things started simply: the doorbell rang — or some bell rang — but no one was at the door. Next, loud thumping and crashing were heard. Perhaps that could be explained in some natural way, such as a clumsy burglar, but again no explanation was found by the family or their boarders. Then furniture began to move without anyone or anything pushing it: a chair, a basket of silverware and a box of coal, more chairs, a sofa, a trunk, and even a bureau. Witnesses also reported hearing a scream, one sounding as if it had come from a woman. This was on the third and final night, so perhaps the spirit was saying farewell. One official record says the scream was “short, not very loud,” but others describe it as “a long, loud wail of anguish.” An online article from 1997 quotes unnamed sources as describing a woman ghost bathed in light, who ‘threw her head back to the heavens’ and ripped loose with ‘a long wild, shrill scream . . . half of fear and half of rage.'” Even though Clarke disparages an early article in the San Francisco Chronicle as reflecting the reporter’s “vivid imagination,” his own description of the scream comes close to the more dramatic version.

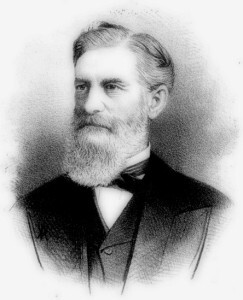

Thomas Brownell Clarke (1823-1884)

Thomas Brownell Clarke (1823-1884)Friends of the family confirmed the phenomena. The newspaper reports spurred gawkers to surround the house for a glimpse of what we would now call poltergeist activity. Enough attention and concern were stirred that an impromptu investigative committee was formed. This first group arrived in time to witness that third night of activity. And they left undecided: “What I have seen and heard to-night is the work either of devilish spirits, or of equally devilish man.”

A Formal Committee InvestigatesIn the wake of the haunting, another committee was formed to spend a full week investigating the house and the testimonies of witnesses. This more-thorough delegation was comprised of William W. Crane, Jr., a lawyer; John Knox McLean, a Congregationalist pastor; and Joseph Le Conte, a professor of geology and natural history at UC-Berkeley. On the surface, neither Crane, McLean, nor Le Conte seems especially knowledgeable about ghosts or well-suited to investigate a haunting. Of course, this might have been their strength: they weren’t seeking validation of any assumptions about the paranormal.

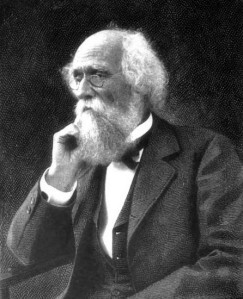

That said, Le Conte was probably a staunch skeptic, as suggested by his 1885 review of a book titled Mind Reading and Beyond. An evolutionist, Le Conte suggests there that the greatest hurdle facing those investigating is the supernatural is a deeply entrenched “love of the marvelous.” He writes: “In Man, the instinct which ascribes a supernatural or spiritual origin to the occurrences of life and to many observed phenomena in nature, has probably been inherited from primeval man. . . . Under the influence of the all-pervading hereditary supernatural instinct, even the most intelligent men are, more or less, governed by the inspirations originating from this source.” Scientists aren’t immune, he adds. In this respect, the clergyman McLean might have brought a healthy balance to the committee (though plenty of religious leaders have denied the reality of ghosts).

Joseph Le Conte (1823-1901) — but for very different reasonsThe Committee’s Findings Are “Leaked” to the Press

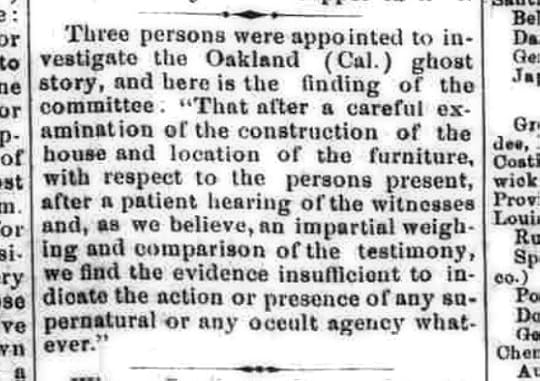

Joseph Le Conte (1823-1901) — but for very different reasonsThe Committee’s Findings Are “Leaked” to the PressWhatever their group dynamics, Crane, McLean, and Le Conte had made a curious compromise with Clarke, the owner of the haunted house. They had agreed that, upon completing their investigation, Clarke himself would have full discretion over publishing their conclusions. As it turned out, a small part of the report compiled by Crane, McLean, and Le Conte was published, and it included their final assessment:

From the front page of the July 23, 1874, issue of the Fayette County Herald. This newspaper was published in Ohio, so presumably the Oakland Ghost had gained widespread interest.

From the front page of the July 23, 1874, issue of the Fayette County Herald. This newspaper was published in Ohio, so presumably the Oakland Ghost had gained widespread interest.It appears that Clarke himself had been responsible for releasing this to the press, and he did so with an adamant refutation of it. I haven’t found an actual article to confirm this, but on July 4, 1874, the Daily Alta published a letter from the Committee to Clarke and a reply from Clarke to the Committee. In the former, Crane, McLean, and Le Conte suggest Clarke released that conclusion and argue that, without the full report as context, it becomes misleading. Clarke fires back, saying that the Committee knew he objected to their conclusion. And he had adhered to their agreement! And he never even wanted an investigation in the first place!

Clarke Defends the HauntingClarke appears to have felt personally attacked by the Committee’s decision that there wasn’t enough proof to deem the disturbances to be supernatural. In an 1877 pamphlet defending the truth of the ghostly visitation, he says he hopes to deflect the “stigma of fraud heaped on me and mine by the committee” (p. 3). He adds that Crane, McLean, and Le Conte “proved themselves wholly unworthy” of the investigation and even states that, in rejecting evidence of a spiritual reality, “they have encouraged the same old spirit that crucified Him”– Him being Jesus (p. 25). Clearly, Clarke saw his spectral furniture movers as proof of survival beyond physical death, and he saw himself as chosen to spread that news. This mission becomes evident in the three pamphlets he published later. He claims they were “channeled” by the spirits of no less than George Washington — yep, that George Washington — along with Washington’s wife, Martha, and his mother, Mary. (These pamphlets are linked on this well-written and well-researched page.) Perhaps there’s a glimmer of self-styled martyrdom or a persecution complex in Clarke’s construing that single sentence about a lack of evidence to be an allegation of fraud.

The Case in HindsightMany years later, James H. Hyslop tried to make sense of the case for the American Society for Psychical Research. After hearing from Clarke’s daughter, he (finally) published the Committee’s report along with Clarke’s pamphlet and other related documents. Amid this 232-page article, Hyslop explains that the Committee’s controversial conclusion “does not deny the existence of evidence in the matter, but the sufficiency of evidence. That is a verdict with which every scientific man would have to agree.” Nonetheless, he also contends that the Committee was biased against a supernatural explanation and that their “denial of the ‘supernatural’ and the ‘occult’ involved a duty to explain [what happened] by some ‘natural’ hypothesis” (pp. 229-30). In other words, Hylsop nods when Crane, McLean, and Le Conte say there’s not enough there to prove supernatural stuff happened, but he crosses his arms and scowls at them for not offering any kind of explanation at all and for sidestepping the question of sufficient evidence of a natural explanation.

Regardless of how well they completed their task, Crane, McLean, and Le Conte were one in a long line of investigative committees appointed to handle alleged hauntings, a tradition going back at least as far the Cock Lane Ghost of 1762. In the 1880s, the Seybert Commission investigated Spiritualism, and presumably other committees probed other paranormal cases or subjects. In this sense, these groups served as first steps toward better-remembered and longer-lasting organizations with similar goals, namely, the Ghost Club at Cambridge and, following it, the Society for Psychical Research.

Documenting Cambridge’s Ghostly Guild/Association for Spiritual Inquiry/Ghost Society/Ghost Club

Around 1850, a number of young men attending the University of Cambridge gathered to study ghosts and related supernatural phenomena. Though committees had been formed earlier to investigate specific alleged hauntings, such as the Cock Lane Ghost, the Cambridge group was different in that it was probably the first to collate multiple cases in the hope of drawing general truths from them. The group preceded the Ghost Club by about one decade and the Society for Psychical Research by three. That much is certain. Exactly what they called their group, on the other hand, is tougher to pin down.

The earliest mention of this organization I’ve found appears nameless in Herbert Mayo’s Letters on the Truths Contained in Popular Superstitions, which was published in 1849. In “Letter IV: Real Ghosts,” we read about a distinguished gentleman who, when a Cambridge undergraduate, served as

secretary to a ghost-society formed in sportive earnest by some of the cleverest men of one of the best modern periods of the university. The result of their labours was the collection of about a dozen stories [about the recently dead appearing to the living as an apparition or in a dream] resting upon good evidence.Mayo’s series of letters was first published in Blackwood’s Magazine in 1847, but apparently he did some heavy editing and updating for the book. I found no mention of the Cambridge society or its secretary in the magazine version.

In a letter dated 2 September 1859, William Howitt asked Charles Dickens if he knew about the Cambridge organization:

Are you aware that there has existed for years a society jocularly called the Ghost Club, consisting of a number of Cambridge men, ... whose object has been to thoroughly sift this question of APPARITIONS, and to test the cases produced by every test of logical and metaphysical enquiries, by the principles of the severest legal and historical evidence; and that, after examining a vast number of such statements, the conclusion they have come to is, that 'the Ghosts have it'?The letter was reprinted in The British Spiritual Telegraph. (Howitt and Dickens are both inductees in the Ghost Hunter Hall of Fame, and their debates over ghosts are examined here.)

Another reference to the group came in 1860. In Footfalls on the Boundary of Another World, Robert Dale Owen mentions that, a few years before publication of his book, “at one of the chief English universities, a society was formed … for the purpose of instituting, as their printed circular expresses it, ‘a serious and earnest inquiry into the nature of the phenomena which are vaguely called supernatural.'” In a footnote, Owen specifies the year as 1851, the university as Cambridge, and the society as being “popularly known as the ‘Ghost Club.'” He also includes the society’s circular as an appendix, but unfortunately, no name at all is offered in this document. Regardless, this circular stands as one of the best — and one of the very few — records remaining.

Nine years later, Epes Sargent clarified that the Ghost Club might have been a nickname for the society. The more official name was the Cambridge Association for Spiritual Inquiry. This is found in a quick mention in Sargent’s book Planchette; or The Despair of Science (1869).

Biographies of the Participants

Biographies of the ParticipantsJump several years later, and the exact name of the organization shifts again when we turn to biographies of three of its participants. First, in A Memoir of Henry Bradshaw, Fellow of King’s College, Cambridge, and University Librarian (1888), G. W. Prothero says that Bradshaw became a member of a society called the Ghostly Guild at Cambridge, and he mentions the 1851 circular. The project

does not seem to have obtained very satisfactory results; at all events, its originators did not go beyond the preliminary inquiry. Sir Arthur Gordon [whose membership is confirmed in the Westcott biography mentioned below] informs me that they came to a conclusion very similar to that which the modern Psychical Society has arrived at -- namely, that, while for the ordinary run of ghost-stories there is nothing in the nature of trustworthy evidence, an exception must be made in favor of phantasms of the living, or appearances of persons at the point of death.Second, Life and Letters of Fenton John Anthony Hort (1896) also uses the name Ghostly Guild, and this is repeated in one of Hort’s letters, though qualified as a “temporary name” there. Along with the circular, this letter might be considered one of the few historical documents left. Dated 29/30 December 1851, Hort explains that, on the topic of ghosts and similar phenomena, the guild’s members were “all disposed to believe that such things really exist.” Third, Life and Letters of Brooke Foss Westcott (1903) once again uses the same name, spelling it Ghostlie Guild. This book was the work of Westcott’s son, who ends this short section by saying he never learned exactly what became of his father’s guild. He does suggests that, after some initial progress at gathering evidence, the elder Westcott had a change of heart about the good derived from investigating the supernatural.

Sketchy HistoriesThere are a few histories, too. In “The Ghost Society And What Came of It,” H. Addington Bruce discusses the group’s impact on later psychical research organizations with his emphasis much more on “what came of it” than on the society itself. The article was published in a 1910 issue of The Outlook. In “An Early Psychical Research Society,” W.F. Barrett reprints the circular yet again after a brief introduction that notes references to the society in two more biographies of participants: Henry Sidgwick and Edward White Benson. Barrett’s piece appeared in a 1923 issue of the Journal of the Society for Psychical Research. There are also mentions in W.H. Salter’s The Society for Psychical Research: An Outline of Its History (Society for Psychical Research, 1948), Alan Gauld’s The Founders of Psychical Research (Schocken, 1968), and Peter Underwood’s The Ghost Club: A History (Limbury, 2010). I haven’t consulted Gauld, but the other histories don’t say very much about the Cambridge project. To be sure, there are very few records remaining to discuss.

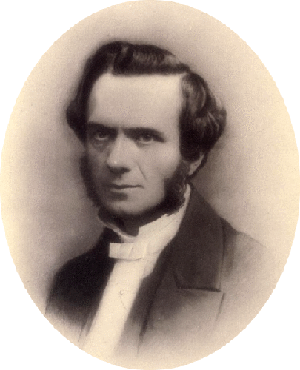

Some Especially Notable Members Brooke Foss Westcott (1825-1901)

Brooke Foss Westcott (1825-1901)Perhaps the man most responsible for founding the Cambridge project was Brooke Foss Westcott. His membership in the group is noted in Hort’s, Benson’s, and his own respective biographies; in Barrett’s history; and it’s Westcott’s name that appears at the end of that important circular. A theologian, he went on to become the Bishop of Durham.

Edward White Benson (1829-1896)

Edward White Benson (1829-1896)That Edward White Benson was a member is documented in all of the above-mentioned biographies except Bradshaw’s and spoken of in Bruce’s, Barrett’s, Salter’s, and Underwood’s respective histories. Benson later became the Bishop of Truro and then, from 1883 to 1896, the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Henry Sidgwick (1838-1900)

Henry Sidgwick (1838-1900)If Henry Sidgwick actually were a member of the group, he would have come in during its final years. His name isn’t included among the participants found in Hort’s and Westcott’s respective biographies. Yet Sidgwick’s own biography says that, as Benson was leaving Cambridge, he passed one of the accounts gained through the circular to young Henry, who had expressed an interest in the subject. (Bruce repeats this in his history, but the same biography might have been his source.) Indeed, Sidgwick was interested in such things — he went on to become the first president of the Society for Psychical Research.

The Ghostly Debate that Charles Dickens Sparked

In late 1859 and early 1860, The Critic: A Weekly Review of Literature and the Arts published a “lively exchange of letters” regarding a haunted house in Cheshunt, England. Well, that’s how William Howitt’s daughter phrases it in a book about her father. These letters appeared in the wake of a ghost hunt Charles Dickens had tried to conduct of that house after Howitt had provided him with a short list of potential haunted locales.

To make these hard-to-find documents more readily available to those interested in Victorian ghost hunts or Dickens or Howitt, I’m posting them here. They all come from the “Sayings and Doings” section of The Critic, which is comprised mostly of reviews of and advertisements for recently-released books. The commentary that originally sparked the exchange appeared on page 599 of the December 17, 1859, issue:

E.R.’s rebuttal appeared on pages 623-624 of the December 24, 1859, issue:

The original report on Dickens’ ghost hunt and the snarky introduction to E.R.’s rebuttal were enough to rouse Howitt’s ire. His response was published on pages 647-648 of the December 31, 1859, issue (and it was reprinted here):

The editor of The Critic didn’t let things end there. When an American advocate of Spiritualism surprised his audience in a lecture hall by turning around and condemning such beliefs, the editor called on Howitt to reply. This is from pages 71-72 of the January 21, 1860, issue:

And, sure enough, Howitt replied. That response was printed on pages 103-104 of the January 28, 1860, issue:

As my research into ghosts and ghost hunters repeatedly confirms, it’s usually wise to see history less in terms of what people believed back then and more in regard to what people debated back then. These exchanges sparked by Dickens’ investigation of the house in Cheshunt drive home that lesson.

Go to my article titled “Charles Dickens, Ghost Hunter? Well…”

Frenemies over Ghosts and the Prelude to Dickens’ Ghost Hunt

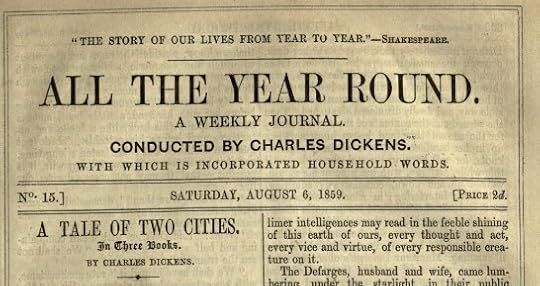

Some trouble began in 1859, when Charles Dickens published a series of anonymous articles in All the Year Round, his new journal following Household Words. That series was titled “A Physician’s Ghosts,” and Parts I and II appeared on August 6, Part III on August 13, and Part IV on August 27. Previously, Dickens had a cordial relationship with William Howitt, publishing his writing in Household Worlds. But Howitt was not pleased with “A Physician’s Ghosts.”

Here’s the title page of the All the Year Round issue that introduced the “A Physician’s Ghosts” articles, which then sparked a skirmish between Howitt and Dickens.

Here’s the title page of the All the Year Round issue that introduced the “A Physician’s Ghosts” articles, which then sparked a skirmish between Howitt and Dickens.In fact, Howitt was peeved enough to have written Dickens a letter expressing his discontent, which he then had reprinted in the British Spiritualist Telegraph. In that reprint, the letter is prefaced by Howitt himself with an explanation that the anonymous physician attempts to explain ghostly encounters as a matter of thought transference occurring at the point of death — a moment of clairvoyance — instead of as the lingering spirit of a deceased person. This idea, called “crisis apparitions,” would go on to gain great interest to members of the Society of Psychical Research and similar investigators. Howitt, a traditional ghostologist, scoffs at this notion in his letter and brings up a haunted house in Cheshunt to prove his point. This is exactly the site that Dickens would be unable to locate a few months later.

Oddly, in that letter complaining about the clairvoyance theory in “A Physician’s Ghosts,” Howitt also mentions the case of Captain Wheatcroft, the so-called War Office Ghost, which actually seems to fit with the crisis apparition theory quite nicely. Captain Wheatcroft was off at war, but he appeared as a ghost to his wife one day. She then learned of her husband’s death. The official date of death, though, was the day after her ghostly encounter, and a subsequent report confirmed that Wheatcroft had died on the day he appeared to his wife. Apparently, this case had gained a lot of attention. (Interestingly, Howitt then asks Dickens if he’s heard of the Ghost Club at Cambridge. He offers one of the earliest descriptions of that organization that I’ve stumbled across.)

Dickens Wrote BackHowitt’s letter is dated September 2, 1859. A return letter from Dickens is dated four days later. There, Dickens explains that he doesn’t personally subscribe to the theories of the series author. Instead, he personally maintains an open — yet cautiously doubtful — view of supernatural subjects: “I do not in the least pretend that such things are not.” Even so, he ends by saying that he’d need much more evidence to be convinced of the War Office Ghost case. (Sadly, he makes no mention of the Ghost Club.)

From here, the trail becomes a bit hit-and-miss. There’s a subsequent letter from Dickens to Howitt dated — interestingly enough — October 31. This is the one that seems to have begun Dickens’s unspectacular ghost hunt, and it’s followed by a couple more letters, dated November 8 and November 15, arranging that hunt. However, as early as November 2, Dickens privately expressed a bit of irritation at Howitt. In a letter to his brother with that date, Dickens describes the War Office Ghost case as “not very intelligible” and Howitt himself as the “Arch Rapper of Rappers.” The term “rappers” was a unflattering nickname for Spiritualists, who relied on the raps of spirits to communicate with the living. This same letter confirms that Howitt was upset over the “A Physician’s Ghosts” series.

It’s unclear exactly when Dickens journeyed to Cheshunt to be thwarted in finding any house fitting Howitt’s description. However, about two years later, Dickens published an article titled “Four Stories” in All the Year Round. The first three of these purportedly true stories involve those “crisis apparitions” that had become an issue when discussed in the “A Physician’s Ghosts” series. Perhaps this was Dickens’s way of making sure the door would remain open on alternate ideas about ghosts.

Go to my article titled “Charles Dickens, Ghost Hunter? Well…“

Charles Dickens, Ghost Hunter? Well…

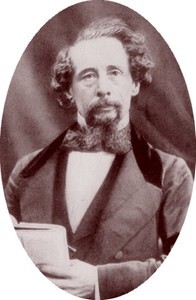

Charles Dickens (1812-1870)Mr. Dickens Sought a Haunted House

Charles Dickens (1812-1870)Mr. Dickens Sought a Haunted HouseFrom A Christmas Carol to “The Signal-Man” and beyond, several gripping ghost stories came from the pen of Charles Dickens. Though a steadfast skeptic when it came to real hauntings, he maintained an interest in the possibility. At one point, he even attempted to become a bona fide ghost hunter. Sadly, the adventure was disappointing and short lived.

It seems that, as 1859 came to a close, Dickens had sparked a debate about ghosts with William Howitt, a more seasoned ghost hunter. Previously, the two men had had a friendly working relationship. Dickens, editor of Household Words, had accepted stories and other kinds of writing by Howitt, but none of this material was related to the supernatural. However, the editor ran a series of articles arguing that ghosts are more a matter of psychic communiqués sent by the dying than the lingering spirits of people no longer breathing. Howitt strongly disagreed, and as a result, tensions rose between the two men. (More details regarding this gathering of storm clouds can be found on this page.)

Perhaps to ease these tensions — or to throw down the gauntlet — Dickens wrote to Howitt, asking for a list of haunted houses that he and some of his chums might investigate. Howitt made a few suggestions, and Dickens settled on a house in Cheshunt, which was conveniently close to London. Joining the great author on the outing were William Henry Wills, Wilkie Collins, and John Hollingshead. The latter devotes a few pages in his autobiography to the ghost hunt, and it’s there that we read about the group’s struggle to find anyone in Cheshunt who had heard of a haunted house in town. Finally, they met a resident old enough to recall a place once said to be haunted — but it had been torn down and replaced. In the end, there was no ghost and not even a house, reports Hollingshead, so the gents decided to settle down to “a substantial meal, after Dickens’s own heart, and the ale was nectar.”

A Debate Then EruptedThough Dickens didn’t directly participate in it, a heated exchange about ghosts followed his disappointing ghost hunt. Instead, the debate was held between Howitt and an editor of a journal called The Critic, one who remained anonymous but who had clearly heard about Dickens’ outing. I located these articles on microfilm — and you can read copies of them in this post — but you might prefer a thinner slice of the debate that was published in The Spiritualist Magazine in early 1860. As its name suggestions, this journal upholds the believers’ position, first challenging Dickens’ skepticism by referring to some of his fiction, oddly enough, and ending by reprinting one of Howitt’s letters from The Critic.

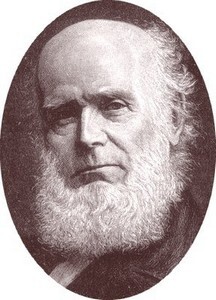

William Howitt (1792-1879)

William Howitt (1792-1879)In that letter, Howitt suggests that Dickens had been too quick to pooh-pooh the haunted house, citing Catherine Crowe’s mention of it in The Night-Side of Nature* as well as his own follow-up investigation. Regarding the lack of a ghost, Howitt says that, “if Mr. Dickens and his friends had ever acquainted themselves with the laws of pneumatology,” they’d have known that “a ghost is not bound to remain in any particular spot for ever.” Ghosts, he contends, have just as much freedom to move around as do “a knot of jolly fellows” who’ve gone ghost hunting.

One might agree with Howitt’s claim that Dickens was too quick to abandon his ghost hunt or hadn’t taken it seriously from the start. But it would also be a mistake to assume that the ghost story writer was dismissive of specters in real life. If he were, he wouldn’t have been one of the most distinguished members of The Ghost Club.

A Fracture Between Dickens and HowittIn 1883, Anna Mary Howitt Watts, Howitt’s daughter, described the debate in The Critic as her father’s “dêbut in the newspapers as champion of the Spiritualist cause.” Barely four years after this debut, Howitt’s formidably titled The History of the Supernatural in All Ages and Nations and in All Churches, Christian and Pagan, Demonstrating a Universal Faith was published. Dickens was then editing All the Year Round, where he reviewed Howitt’s book and titled his own piece “Rather a Strong Dose.” Describing his former friend as being “in such a bristling temper on the Supernatural subject,” Dickens refrains from debating him on specifics. Instead, he informs his readers that Howitt hopes they will forget the Reformation — indeed, Protestantism altogether — and

will please to believe . . . all the stories of good and evil demons, ghosts, prophecies, communication with spirits, and practice of magic, that ever obtained, or are said to have ever obtained, in the North, in the South, in the East, in the West, from the earliest and darkest ages, down to the yet unfinished replacement of the red men in North America.For the remainder of the review, Dickens continues in this sarcastic vein, implying without subtlety that only the most gullible reader should bother with Howitt’s tome.

If nothing else, the fracture between Dickens and Howitt regarding ghosts reminds us that broad generalizations about what was believed by “people back then” rarely hold water. History — and certainly the history of ghosts — is probably best viewed less in terms of what people of a given period agreed upon and more in terms of what they debated. Humanity, after all, is and always has been a cantankerous species.

* Howitt specifies page 332 as the spot to find Crowe’s discussion of the haunted house in Cheshunt, but he must have been looking at a different edition of The Night-Side of Nature than any I’m able to find online. My best guess is he’s referring to the account that starts with “About six years ago” in Crowe’s chapter titled “Haunted Houses.” I base this on the house’s proximity to London, the mention of Mr. C and Mrs. C — whom Howitt reveal to be the Chapmans in his letter and in his book — and the fact that both writers say that subsequent residents of the house experienced strange events. My hunch that Crowe’s story about Mr. and Mrs. C is, in fact, an early version of Howitt’s chronicle of the Chapmans’ experiences in Cheshunt is also supported by what John H. Ingram says in The Haunted Homes and Family Traditions of Great Britian (1905).

Go to the “Frenemies over Ghosts and the Prelude to Dickens’ Ghost Hunt” post. Go to the “The Ghostly Debate that Charles Dickens Sparked” post.

William Howitt and the Intriguing Haunting of Clamps-in-the-Wood

William Howitt (1792-1879)Who Ya Gonna Call?

William Howitt (1792-1879)Who Ya Gonna Call?When Charles Dickens wanted to locate a haunted house not too far from London, he contacted William Howitt. Apparently, Howitt was something of an expert on haunted places, and he describes one of his own ghost hunts in an 1862 article titled “Berg-Geister — Clamps-in-the-Wood.” The first part of this curious title means “mountain spirits” in German. The second part is the name of a farmhouse, one that that used to belong to a man named Clamps and that was in the woodlands near Thorpe in the East Midlands of England.

Howitt had been born and raised in this region, and on a visit there, he overheard an elderly woman talking to a clergyman. She was asking for his help in exorcising some spirits haunting that farmhouse, which she now inhabited after Mr. Clamps had gone. The cleric, an Oxford-educated man, dismissed the woman’s notion of ghosts

But Howitt didn’t share this skeptical view, and so he asked others about the haunted cottage in the woods. He learned that several people confirmed the woman’s story. In years past, Mr. Clamps himself had claimed to have seen strange lights hovering and moving inside his house. They proved to be harmless, and the former resident had even grown fond of them, calling them his “glorious lights.” His neighbors had seen them, too, while visiting.

Howitt Visited the Haunted CottageHowitt couldn’t resist. He embarked on a search for the elderly woman whose request for help had been waved off. He found Clamps-in-the-Wood, which the woman shared with her daughter, son-in-law, and grandchildren. Worrying about how these grandkids might react to the spectral lights had spurred their grandmother to seek the clergyman’s help. Like Mr. Clamps before them, however, the three adults living there had never felt much threat from the manifestations.

At the farmhouse, Howitt learned that most witnesses only perceived the ghostly lights, which would emerge from solid walls and sink down into the stone floor. The grandmother, though, was able to discern more. Howitt writes:

[T]he old woman saw clearly dark figures at the centres of the lights. They were generally three, like short men, as black and as polished, she said, as a boot. Whilst they staid, she said, their hands were always in motion.... [They] seemed to take a pleasure in coming towards the warm fire, and looking at what was going on.When Howitt asked if he might be allowed to stay and see the lights, he was disappointed to learn that they could only be seen during the dark months of winter. He was unable to come back then.

Spirits of the Mines and MountainsAnd yet the ghost hunter held to his conviction that the intriguing spirits were real. In fact, as the introduction of his article makes clear, he had a theory about the identity of these seemingly non-human entities. Now, the region of England that surrounds Clamps-in-the-Wood was known for lead mining, and mining is a key clue. Howitt explains, “We know that the miners of Germany and the North have always asserted and still do assert the existence of Kobolds and other Berg-Geister, or spirits of the mountains or the mines. . . .” Though he doesn’t discuss the spectral light, he reports that these spirits are drawn to the fires and the company of living humans. They’re innocuous, very black, and about four-foot-high. (Though much darker than the Disney depiction, these mining spirits remind me of Snow White’s seven dwarfs!) He makes quick mention of a miner in Wales who claims to have discovered copper with the help of such spirits.

The article ends with Howitt recounting the adventure of a friend of his, a “Captain D–,” who had plans to visit York for Christmas and offered to stop by Clamps-in-the-Wood on the chance of verifying the ghost lights. The good captain managed to find the remote cottage and was given permission to remain awake there through the night. After a few hours, he heard knockings, but he didn’t think much about them. His cloak then slipped off a table for no clear reason, and the old woman explained that the spirits were having a bit of fun. Finally, after his hostess went to bed, Captain D– did indeed see what he’d come for: “He saw a globular light about the size of an ordinary opaque lamp-globe issue from the wall, about five or six feet from the floor, and advance about half a yard into the room.” It only stayed a few minutes, then it receded the same way it had come. The captain quickly examined the wall, the windows, the chinks in the door — nothing was there to explain the light. And that was all he witnessed for the rest of the night.

Two Related ArticlesI’ve found two subsequent articles related to the Clamps-in-the-Wood visitations. The first was published in an 1865 issue of Chambers’s Journal, and the anonymous narrative reads almost like it’s Captain D–’s own account of his investigation. Pursuing the claims of “a friend who informed us of strange sights and sounds, nightly visitations, and other wonders,” this writer visits Clamps-in-the-Wood in January. The grandmother is asked about the manifestations. The coat slips inexplicably from a table. Some noises “like a drum gently beaten” are heard. A light is seen, but it disappears quickly. Subsequent examination fails to provide a physical explanation. There are one or two new wrinkles — a table leaf levitates, for instance — but this article doesn’t really add much information to Howitt’s from three years earlier.

Ten years later, the second article appeared on the front page of the October 29, 1875, issue of the Banner of Light, a Spiritualist newspaper published in Boston, Massachusetts. There, Emma Hardinge Britten relates her own investigation, which she says was aided by her powers as a medium. Unlike the anonymous writer, Britten acknowledges Howitt’s earlier report, but her investigation occurred after Clamps-in-the-Wood had been abandoned. The medium was taken to another spot ripe for a ghostly encounter. There, Britten heard knocking along with experiencing what seems like poltergeist activity — kitchen items fell from shelves and a “rude door shook violently. . . .” Afterward, she saw “a row of four lights as large as the veritable ostrich’s egg which adorned the mantle shelf of the humble shanty.” Sure enough, the medium is able to discern a “faint outline of a miniature human form” within each light before they vanished into the wall behind.

Emma Hardinge Britten (1823-1899)

Emma Hardinge Britten (1823-1899)Britten was next granted a second look at the glowing figures. “They were grotesque in shape,” she says, “with round shining heads, destitute of hair, perfectly black, and more human about the head than the body.” With playful expressions, they seemed to somersault for Britten before signalling the end of the show with a “strange duck with each little head” and then disappearing for good.

Folklore has a number of mine-associated spirits, be they the knocker of Wales, Cornwall, and the West Country of England; the bluecap from further north in the UK; the kobold of Germany; or the shubin of the Ukraine. Clearly, there are similarities between these tales and these three reports on supernatural manifestations in Clamps-in-the-Wood and the cottage visited by Britten. This wouldn’t be the only time that such elfish creatures would sneak over from folklore into journalism. Remember that, a few decades later, another ghost hunter named Sir Arthur Conan Doyle would write articles for The Strand regarding the validity of fairy photographs taken in Cottingley. As both Howitt and Britten explain at the start of their articles, the spirit world is populated by more than just the phantoms of human beings who have died. At least, this seems to have been the case from the mid-1800s to the early 1900s.

Dr. Edward Drury: Humble(d) Ghost Hunter

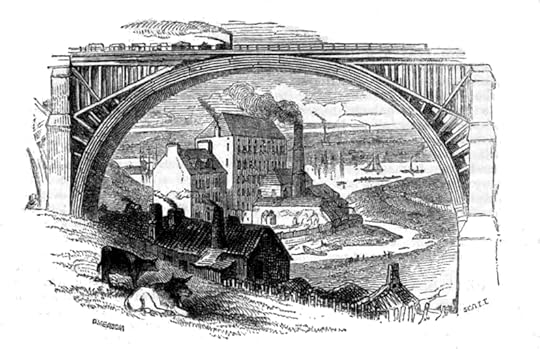

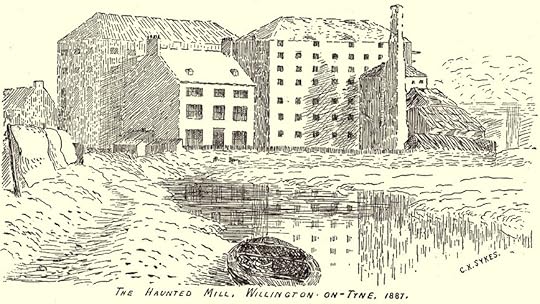

In the mid-1800s, an ordinary-looking house in the village of Willington became one of England’s most famous haunted sites. The first published record of it appears to be a pamphlet titled “Authentic Account of a Visit to the Haunted House at Willington near Newcastle-Upon-Tyne” (Newcastle: Richardson, 1842), but within the year, the same publisher reprinted that account in a volume called The Local Historian’s Table Book. Told mostly through letters, the narrative spotlights an overnight ghost hunt of the house conducted by Edward Drury, a local doctor.

William Howitt later reprinted the account — adding his own findings regarding the haunting — in the May 22, 1847 issue of Howitt’s Journal of Literature and Popular Progress. To a lesser extent, Catherine Crowe continued the ghost hunt, too. In her chapter on haunted houses in The Night Side of Nature (1848), she opens a section on the Willington haunting with a letter she received from the house’s owner, Joseph Procter, and then reprints Howitt’s and Drury’s narratives. From there on, the case and Drury’s important role in it have regularly appeared in books about ghosts, especially ghosts in Britain.

Willington Mill as illustrated in Howitt’s JournalThings Started Out Well, But…

Willington Mill as illustrated in Howitt’s JournalThings Started Out Well, But…Yet Drury was far from a model ghost hunter. He was very much a novice at paranormal investigating as revealed in his description of what happened the night he kept watch in the Willington house. With small edits made by myself, this is what he reported to Procter about that night’s ghost hunt:

Sunderland, July 13, 1840.Dear Sir,—I hereby, according to promise in my last letter, forward you a true account of what I heard and saw at your house, in which I was led to pass the night from various rumours circulated by most respectable parties. . . . Having received your sanction to visit your mysterious dwelling, I went, on the 3rd of July, accompanied by a friend of mine, T. Hudson. . . . I must here mention that, not expecting you at home, I had in my pocket a brace of pistols, determining in my mind to let one of them drop before the miller, as if by accident, for fear he should presume to play tricks upon me; but after my interview with you, I felt there was no occasion for weapons, and did not load them, after you had allowed us to inspect as minutely as we pleased every portion of the house.I sat down on the third story landing, fully expecting to account for any noises that I might hear, in a philosophical manner. This was about eleven o’clock p.m. About ten minutes to twelve we both heard a noise, as if a number of people were pattering with their feet upon the bare floor, and yet so singular was the noise that I could not minutely determine from whence it proceeded. A few minutes afterwards we heard a noise as if some one was knocking with his knuckles among our feet; this was followed by a hollow cough from the very room from whence the apparition proceeded. The only noise after this was as if a person was rustling against the wall in coming upstairs.At a quarter to one I told my friend that, feeling a little cold, I would like to go to bed, as we might hear the noise equally well there; he replied that he would not go to bed till daylight. . . . I took out my watch to ascertain the time, and found that it wanted ten minutes to one. In taking my eyes from the watch, they became rivetted upon a closet door, which I distinctly saw open, and saw also the figure of a female attired in grayish garments, with the head inclining downwards, and one hand pressed upon the chest, as if in pain, and the other—viz. the right hand—extended towards the floor, with the index finger pointing downwards. It advanced with an apparently cautious step across the floor towards me; immediately as it approached my friend, who was slumbering, its right hand was extended towards him; I then rushed at it, giving, as Mr. Procter states, a most awful yell; but instead of grasping it, I fell upon my friend, and I recollected nothing distinctly for nearly three hours afterwards. I have since learnt that I was carried down stairs in an agony of fear and terror.I hereby certify that the above account is strictly true and correct in every respect.Edward Drury, North ShieldsThings Didn’t End Well, But…Alas, Dr. Drury hardly ends up being a shining hero in the adventure, despite the suggestion that he acted to protect Hudson. Nonetheless, this brief story carries some of the conventions of many other ghost hunting narratives, including those found in fiction: securing permission to spend a night in the house said to be haunted, bringing a companion — a sort of “Dr. Watson” — packing pistols in case a prank is being pulled, the long wait, and the eventual encounter with the ghost.

And as illustrated in The Monthly Chronicle of North-Country Lore and Legend

And as illustrated in The Monthly Chronicle of North-Country Lore and LegendFew works of fiction conclude with the ghost hunter unconscious and experiencing amnesia due to fear, of course, but even this element of Drury’s widely published account might have served as inspiration for several fiction writers. In an earlier letter, the doctor says this to Procter: “I am persuaded that no one went to your house at any time more disbelieving in respect to seeing any thing peculiar,–now, no one can be more satisfied than myself.” Unable to explain his experience with “natural causes,” he concludes that the terror he felt “was a punishment to me for my scoffing and unbelief.” In other words, the cocky skeptic who had intended to debunk the ghost rumors was humbled — even punished — while spending a night in a haunted house. This is a theme underlying such fictional works as the anonymous “A Night in a Haunted House” (1848), M.A. Bird’s “The Haunted House” (1865), George Downing Sparks’ “The House on the Corner” (1888), B.M. Croker’s “Number Ninety” (1895), Ralph Adams Cram’s “In Kropfsberg Keep” (1895), and C. Ashton Smith’s “The Ghost of Mohammed Din” (1910). (It should be noted that Charles May’s “The Haunted House” from 1831, before Drury’s narrative, also follows the same basic pattern.)

Those interested in the Willington haunting can find more information in the 1887 volume of The Monthly Chronicle of North-Country Lore and Legend, which reprints the decidedly more skeptical version of the ghost hunt told by Tom Hudson, Drury’s companion on the night. In 1892, the Society for Psychical Research published a fuller account of the haunting with additional information provided by Joseph Procter’s son. What may well be the first mention of Drury’s ghost hunt in fiction appears in G. Linnæus Banks’ 1881 novel Stung to the Quick: A North Country Story.