Tim Prasil's Blog, page 18

December 15, 2022

A Gallery of Notable Gentlemen, All of Whom Encountered Vera Van Slyke

Last week, I blogged about how a founding occult detective named Harry Escott might have been real. I even provided a photograph that might be one of him. In addition, more than once, expert ghost hunter Vera Van Slyke identifies Escott as her mentor paranormal investigation. This week, I’ve gathered photographs of men we know to be real and who also are said to have met Van Slyke during her later investigations.

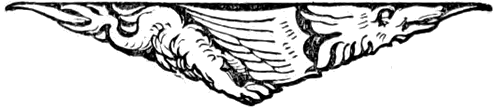

William James (1842-1910)

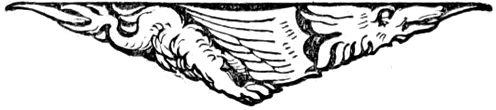

William James (1842-1910)Harvard professor William James plays a key role in the book-length chronicle titled Guilt Is a Ghost. In 1899, James was sitting at the séance where Van Slyke, his friend, exposed a young medium’s fakery. The shock of this was the tipping point for millionaire Roderick Morley, who was counting on this séance to solve the murder of his close and trusted spiritual advisor. Morley took his own life that night. Four years later, the Morley mansion was reported to be haunted. Van Slyke was called back to Boston, this time not to debunk, but to confirm that spirits lingered in this house and to solve the mystery that bound them there. James assists her, but he is much better remembered as a philosopher/early psychologist with keen interests in religious experience and psychical research.

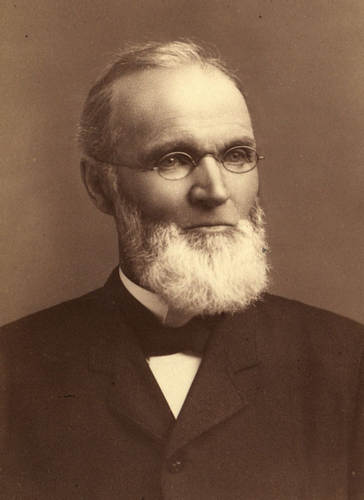

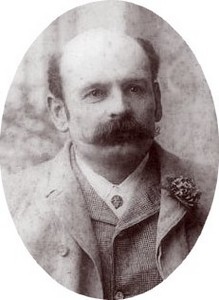

William B. Watts (1852-1925)

William B. Watts (1852-1925)William B. Watts was Chief Inspector of the Bureau of Criminal Investigation when Van Slyke returned to Boston to tackle the Morley haunting. As the man who had defrocked faith-healer Francis Truth, Watts was no stranger to debunking. Maybe this is why he warmed up to Van Slyke — despite her conviction that ghosts are real — and worked with her to reopen the “cold-case” murder of Morley’s associate. Watts was less focused on wraiths than he was on rascals, his term for criminals of the corporeal realm.

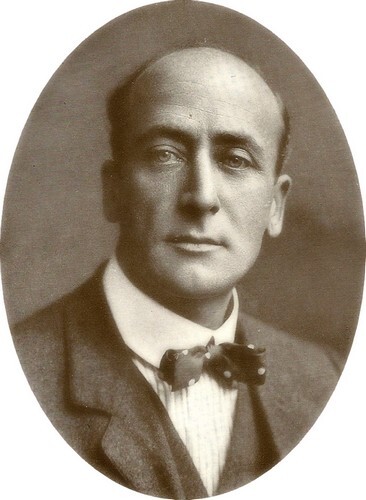

Peter M. Hoffman (1863-1948)

Peter M. Hoffman (1863-1948)Peter M. Hoffman had not yet realized his ambitions of become Sheriff in 1906. Instead, he was still the Cook County Coroner, and that year, he summoned Van Slyke to help him solve a series of bizarre deaths occurring among workers digging tunnels deep below Chicago. Like Watts, his fellow lawman, Hoffman was a skeptic. However, he too grew to admire the determination and intelligence Van Slyke brought to her investigations. He appears in a chronicle is titled “Vampire Particles,” which is found in Help for the Haunted.

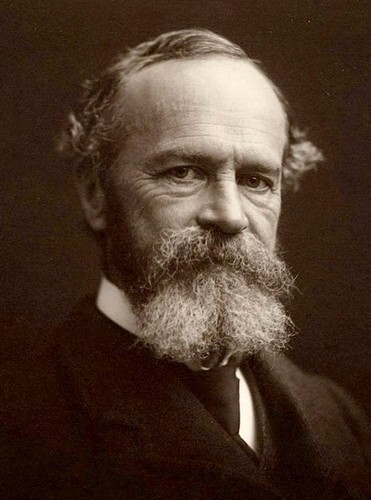

Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930)

Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930)Arthur Conan Doyle had left his fictional detective, Sherlock Holmes, far behind when he was touring the United States in 1923 to lecture about the marvels of Spiritualism. Along the way, he shared a train ride with Van Slyke. Though Conan Doyle’s eagerness to believe in almost anything otherworldly clashed with Van Slyke’s more selective stance, the journalist revealed sympathy and respect for the author. Their encounter is narrated in The Hound of the Seven Mounds.

Erik Weisz, also known as Harry Houdini (1874-1926)

Erik Weisz, also known as Harry Houdini (1874-1926)Conan Doyle’s strained friendship with Harry Houdini — as well as the escape artist’s great fame — came after 1905. That’s the year Houdini traveled to Chicago, hoping Van Slyke would assist him in defrauding a Spiritualist medium. The medium claimed to have gotten unsavory knowledge about Houdini’s past from the spirit of a deceased woman. Meanwhile, there’s a whispering ghost that Houdini says visits him at night. This case, titled “Houdini Slept Here,” is among those in Help for the Haunted. It’s what I’ll be reading in this weekend’s episode of Tales Told When the Windows Rattle.

You can find out more about the Vera Van Slyke Ghostly Mystery series on this page. My reading of “Houdini Slept Here” premieres this weekend on the Tales Told YouTube channel. You can also find it here. If you’d prefer the podcast version, I recently added Apple Podcasts to Spotify, Google Podcasts, RadioPublic, Stitcher, and Anchor.

— Tim

December 8, 2022

Was Harry Escott — Founding Occult Detective and Vera Van Slyke’s Mentor — a Real Person???

I introduce this weekend’s episode of Tales Told When the Windows Rattle by reading a few lines from a lengthy obituary about author/poet Fitz-James O’Brien. The obit writer remains anonymous, but I’d bet a nickel it’s O’Brien’s buddy and editor William Winter. Anyway, that writer turns to “The Pot of Tulips,” the first of two tales featuring O’Brien’s founding occult detective, Harry Escott. Apparently, some of the original readers of this adventure responded to it with resolute belief:

The plot is wrought out with great skill, the marvelous dénouement being narrated in the most matter-of-fact manner. To the story was appended a postscript, to the effect that any person ‘who wished further to investigate the subject might have an opportunity of doing so by addressing Harry Escott, care of this Magazine.’ Scores of letters, and not a few personal applications, were received, asking for the means of communicating with Mr. Escott. I remember one young man, who called so often, and was so firmly convinced that in this narrative lay the germs of some great revelation, that I was compelled to tell him that the whole was an effort of pure imagination. Unfortunately, he would not believe me.

I then ask my listeners: “What if that young man — and those scores of letter writers — were not wrong? What if Harry Escott was real?

This photograph — identified only as “Vera’s Harry” on the back — was among my great-grandaunt’s memoirs. Is this Harry Escott?

This photograph — identified only as “Vera’s Harry” on the back — was among my great-grandaunt’s memoirs. Is this Harry Escott?Indeed, Vera Van Slyke identifies Harry Escott as her ghost-hunting mentor in a chronicle titled “Houdini Slept Here.” (As fate would have it, I’ll read this in the next episode of Tales Told.) Van Slyke is asked why she never used her journalist skills to recount her own paranormal investigations for publication, and in her explanation, she suggests how Escott’s path crossed with O’Brien’s. Van Slyke says,

Early in his career, [Harry Escott] had granted permission to an aspiring writer to pen a couple of his experiences. That writer took the liberty of presenting both cases as if recorded by Harry himself, perhaps for the dramatic effect that goes with firsthand accounts of the supernatural. They were published in this manner. . . . You see, spectral encounters are better related by a reporter who brings some objectivity to the subject. By impersonating Harry himself, the writer inadvertently prompted many readers to view my mentor either as a liar or a lunatic.

Apparently — and predictably — there were skeptical readers along with those scores of letter-writing believers. Van Slyke then suggests that it would be better if her own ghostly mysteries were penned by her friend and my ancestor, Lida Bergson, née Prášilová. (Adding the “ová” suffix to a woman’s surname is a long-lived but now dying tradition in Czech and other Slavic cultures.) And that’s what happened, though Lida’s chronicles weren’t published until I inherited them.

After years of trying to sort out what’s real and what’s “an effort of pure imagination” in the Van Slyke chronicles, I’ve had only very limited success. Despite rumors to the contrary, the Internet does not answer all our questions, and in this case, neither do the Prasil family stories. I have resigned myself to letting my readers decide for themselves.

And you can take a step toward making that decision by listening to “A Pot of Tulips,” attributed to Fitz-James O’Brien, this weekend at the Tales Told YouTube channel or on this page. Learn more about the Vera Van Slyke Ghostly Mysteries series here.

— Tim

December 1, 2022

Sheer-Legs — and the Danger that Weighed Heavily with Them

“Current legislation means they can never be used again,” says the Barrow Hill Collections website in regard to an enormous contraption called a sheer-legs (sometimes spelled without the hyphen). This device did various kinds of heavy lifting, but as the old photos on that page show, one kind involved hoisting up a steam engine so that a worker can perform maintenance from below. Yes, people did work below! a! steam engine! weighing I don’t know how many tons! A slip of a chain, and — well, you understand why using them has become illegal.

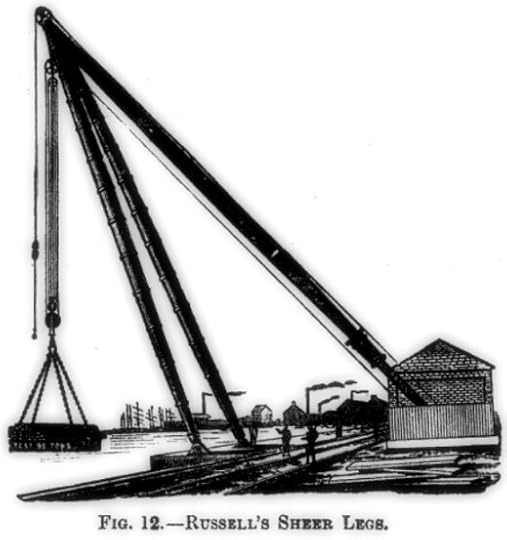

This illustration of a sheer-legs used for transferring cargo to and from ships comes from an 1897 textbook on engineering.

This illustration of a sheer-legs used for transferring cargo to and from ships comes from an 1897 textbook on engineering.A sheer-legs figures prominently in this weekend’s episode of Tales Told When the Windows Rattle. I read Henry Tinson’s 1875 ghost story, “Under the Sheer-Legs.” Early in the tale, Tinson establishes the eerie atmosphere of a major Victorian railroad hub: “The long gloomy sheds and empty workshops, with uncouth machinery, and enormous engines imperfectly seen in the dim light, were, after dark, as vague and full of mystery as any old monastery or castle could ever be.” Tinson knew that there were places built in his own era that were as daunting and as ghostly as crumbling, medieval buildings.

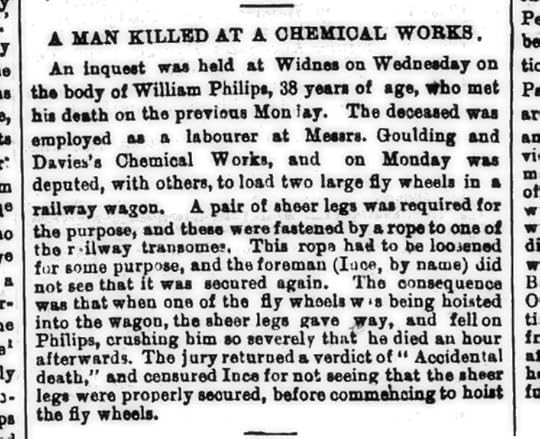

The same year that Tinson’s “Under the Sheer-Legs” was published, this article about a man crushed under a sheer-legs appeared in the

Warrington Examiner

. As in the story, a jury rules the tragedy to be an “Accidental death.”

The same year that Tinson’s “Under the Sheer-Legs” was published, this article about a man crushed under a sheer-legs appeared in the

Warrington Examiner

. As in the story, a jury rules the tragedy to be an “Accidental death.”Those who listen to Tales Tales regularly know that I play with character voices and accents (and sound effects) to tug each episode away from being a “newsreader” narration and to nudge it closer to being an audio drama. I hope I don’t offend the entire population of the United Kingdom with my attempt to give each minor character a different regional British accent. I’m certain I’ve failed in accuracy, but I hope I’ll still earn a “well done, mate” for being a guy who grew up in Illinois — the same state where Dick Van Dyke grew up — and who butchered more regional dialects than a cockney alone. A guy needs a goal, after all.

The Tales Told YouTube channel is found here, and you can choose the video or the audio version on this page.

— Tim

November 23, 2022

The Curious Frequency of Skeletal Remains Said to be Found at Sites Said to Be Haunted

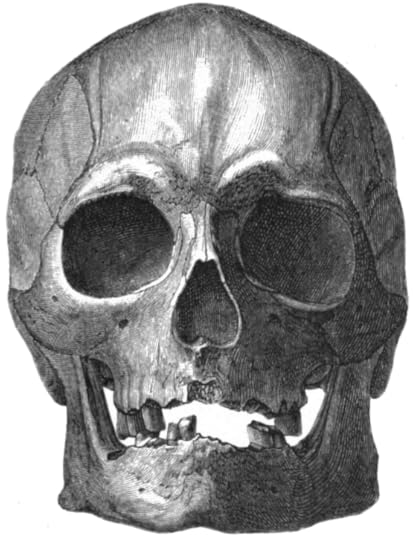

Some weeks ago, I promised to blog about something I discuss more fully in Certain Nocturnal Disturbances: Ghost Hunting Before the Victorians. It’s the long tradition of linking a site allegedly haunted to human bones allegedly discovered on the grounds. I have a nagging hunch these stories owe much to the legend of Athenodorus, the great-great-great-… grandfather of ghost hunters. This legend was probably a century old when it was put to paper (or was it papyrus?) in the first century BCE. Briefly, Athenodorus investigates a house said to be haunted; he follows the ghost there to skeletal remains of someone buried in chains in the backyard; and once those bones are reinterred with due ceremony, the ghost is released from its earthly concerns.

There was renewed interest in this legend in Britain and the United States (and probably elsewhere) in the 1800s and early 1900s, and I’ll look at a sampling of prominent hauntings involving skeletal remains from those decades.

1872: “A Hampshire Ghost Story,” published in Gentleman’s Magazine, presents Mary Ricketts’ account of the 1765-1771 haunting of Hinton Ampner. Supplementary documents are included, and in one of them, we read about how, when the house was demolished in 1797, “there was found by the workmen under the floor of one of the rooms a skull, said to be that of a monkey.” Regrettably, no inquiry was made into “the real nature of the skull.” In 1893, reporting on the case for the Society of Psychical Research, John Crichton-Stuart said it’s “suggested that the skull . . . was the head of a child,” since it’s “absolutely inexplicable that a monkey’s skull should be buried in a small box under the floor of a room.” The notion of keeping a child’s skull in a box under the floor doesn’t seem to strike Crichton-Stuart as equally bizarre, even one fitting his tenuous theory about an illegitimate baby having been murdered in the house. In 1945, examining the haunting again, Harry Price shouted: “Some say it was the skull of a baby!” (See Poltergeist over England: Three Centuries of Mischievous Ghosts, p. 144). Thus, a monkey skull evolved into a human one.1898: The August 30th issue of London Standard reported on a farmhouse in Halton Holgate, where residents Mr. and Mrs. Wilson were said to have found “human bones” under the floor. This was presumed to be connected to “strange tappings having been heard” and “a ghost having been seen” by the couple. In the September 13th issue, the Standard said the ghostly phenomena continued and — with echoes of Athenodorus — “a London clergyman has written advising Mrs. Wilson to bury the bones in consecrated ground, then, he says, ‘the ghostly visitor will trouble you no longer.'” Below, I discuss an amusing follow-up investigation of this haunted house conducted by travel writer James John Hissey. 1904: Newspapers from New York to Michigan and Arizona (and probably well beyond) announced that William H. Hyde unearthed bones beneath the cabin that had belonged to the Fox sisters about fifty years earlier. These were the famous Fox sisters whose 1848 claims of being able to communicate with spirits ignited a massive wave of interest in Spiritualism, and the 1904 skeletal remains corroborated their early allegation of having contacted a murder victim in that cabin. In contrast to the Hinton Ampner case, according to the New-York Tribune, “the arm and leg bones of a human being” were discovered and then “all the important bones of the body except the skull.” M.A. Veeder, a physician with an interest in such things, looked into the case for

The Occult Review

. (See page 52.) He concluded that the bones — which were mismatched and looked to be haphazardly assembled “by some one without a knowledge of anatomy” — had been planted in the cabin Even more damaging, Veeder says he had since heard the confession of a prankster in a 1909 update for the

Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research

. Although this debunking had appeared in prominent paranormal publications, believers still used the dubious bones to support Spiritualism. Franklin A. Thomas does so in

Philosophy and Phenomena of Spiritualism

(1922), and the same goes for Arthur Conan Doyle in Chapter 4 of The History of Spiritualism (1926). Bones, after all, are hard evidence of spirits.1918: Here, the haunting is far less famous than one of its investigators. Conan Doyle was on his way to rebranding himself — from the creator of the wildly popular Sherlock Holmes series to a proponent of almost anything otherworldly — when his book The New Revelation was released. There, he discusses a poltergeist case he had investigated roughly twenty years earlier. He explains that, a few years after that ghost hunt, “I met a member of the family who occupied the house, and he told me that after our visit the bones of a child, evidently long buried, had been dug up in the garden. You must admit that this was very remarkable. Haunted houses are rare, and houses with buried human beings in their gardens are also, we will hope, rare.” On the same page, he then notes that “there was also some word of human bones” found in the Fox sisters’ cabin. After reading this, one might wonder just how rare haunted houses with buried bones are.

1904: Newspapers from New York to Michigan and Arizona (and probably well beyond) announced that William H. Hyde unearthed bones beneath the cabin that had belonged to the Fox sisters about fifty years earlier. These were the famous Fox sisters whose 1848 claims of being able to communicate with spirits ignited a massive wave of interest in Spiritualism, and the 1904 skeletal remains corroborated their early allegation of having contacted a murder victim in that cabin. In contrast to the Hinton Ampner case, according to the New-York Tribune, “the arm and leg bones of a human being” were discovered and then “all the important bones of the body except the skull.” M.A. Veeder, a physician with an interest in such things, looked into the case for

The Occult Review

. (See page 52.) He concluded that the bones — which were mismatched and looked to be haphazardly assembled “by some one without a knowledge of anatomy” — had been planted in the cabin Even more damaging, Veeder says he had since heard the confession of a prankster in a 1909 update for the

Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research

. Although this debunking had appeared in prominent paranormal publications, believers still used the dubious bones to support Spiritualism. Franklin A. Thomas does so in

Philosophy and Phenomena of Spiritualism

(1922), and the same goes for Arthur Conan Doyle in Chapter 4 of The History of Spiritualism (1926). Bones, after all, are hard evidence of spirits.1918: Here, the haunting is far less famous than one of its investigators. Conan Doyle was on his way to rebranding himself — from the creator of the wildly popular Sherlock Holmes series to a proponent of almost anything otherworldly — when his book The New Revelation was released. There, he discusses a poltergeist case he had investigated roughly twenty years earlier. He explains that, a few years after that ghost hunt, “I met a member of the family who occupied the house, and he told me that after our visit the bones of a child, evidently long buried, had been dug up in the garden. You must admit that this was very remarkable. Haunted houses are rare, and houses with buried human beings in their gardens are also, we will hope, rare.” On the same page, he then notes that “there was also some word of human bones” found in the Fox sisters’ cabin. After reading this, one might wonder just how rare haunted houses with buried bones are.Sure enough, it’s fairly easy to find reports that combine ghosts with skeletal remains. As I discuss with greater detail in Certain Nocturnal Disturbances, I’ve come upon more examples from both sides of the Atlantic. And I continue to find them, the last one presented here. Often, reports of ghosts are better understood as folklore — that fascinating middle-ground between fact and fiction — and finding human bones to substantiate a haunting seems to be a recurring folkloric motif.

James John Hissey (1847-1921)

James John Hissey (1847-1921)I dug up this topic because this weekend’s episode of Tales Told When the Windows Rattle features my reading of James John Hissey’s chronicle about trying to arrange a ghost hunt at Halton Holgate. Hissey was a frustrated ghost hunter, and — spoiler alert — his lifelong desire to witness a specter seems never to have been fulfilled. Nonetheless, he maintains a hopeful and humorous attitude toward his hapless history as a phantom finder. Well, mostly hopeful and humorous. Ride along with him as he journeys through Lincolnshire, England, managing to track down the haunted farmhouse and to chat with the Wilsons about their ghost — and those equally creepy bones — at the Tales Told YouTube channel. I also share the videos here, adding a downloadable copy of the audio along with links to some podcast sites carrying the series.

— Tim

November 17, 2022

The Scarlet Pencil: Why I Put Alwyne Sargent Before Jack Hargreaves

When Allen Upward’s five-story occult detective series appeared monthly in The Royal Magazine, from late 1905 to early 1906, it went by the title “The Ghost Hunters.” I dropped this rather bland title when I edited the tales for From Eerie Cases to Early Graves: 5 Short-Lived Occult Detective Series. At first, I simply dubbed that section of the anthology “Allen Upward’s Jack Hargreaves and Alwyne Sargent,” since this was in keeping with the other author/character section titles.

The banner placed above each of Upward’s five Sargent and Hargreaves stories in The Royal Magazine

The banner placed above each of Upward’s five Sargent and Hargreaves stories in The Royal MagazineAs I was working on the pieces, I realized I was making a mistake — and being outright sexist — for placing Hargreaves before Sargent. Granted, he is the narrator. He is the realtor who earns a reputation for turning haunted houses into profitable properties. He is Sargent’s boss.

But Hargreaves is clearly the Watson to Sargent’s Holmes. She does the brain work, since she’s clairvoyant. She puts her health at risk to help restless spirits and to expand our understanding of the paranormal. She, ultimately, solves the occult mysteries. To be sure, Upward wants us to see that it’s the partnership that matters, just as Arthur Conan Doyle does with Holmes and Watson. Furthermore, Hargreaves is far from the idle sidekick that Watson occasionally finds himself to be. But a reader might easily sense that Sargent could’ve done occult-detection work without Hargreaves. And probably not the other way around.

Allen Upward (1863-1926)

Allen Upward (1863-1926)Was Allen Upward deliberately challenging the gender dynamic reinforced by Conan Doyle’s well-established pair by cleverly making his lead detective a woman? Did he advocate women’s suffrage or participate in any other of his era’s movements for greater gender equality? There were some male authors of his generation who did so — for instance, Hamlin Garland comes to mind. However, I haven’t found anything to support the claim that Upward was among those authors.

All I can say is that, like Garland, Upward knew his stuff when it came to psychical research. When working on From Eerie Cases to Early Graves, I found myself footnoting a fair number of his references to the era’s thinking about hauntings and about how clairvoyants can play a key role in resolving them. Hereward Carrington’s chapter titled “Haunted Houses and Their Cure” does a good job of explaining this, too, though it was published a few years after Upward’s series.

Find out what other authors/characters join Upward’s Sargent and Hargreaves on the page for From Eerie Cases to Early Graves: 5 Short-Lived Occult Detective Series. In addition, my reading of the first Sargent and Hargreaves adventure is featured on this weekend’s episode of Tales Told When the Windows Rattle. You’ll find it on this page — where you’ll also find links to the podcast version — or on the YouTube channel. Regarding the latter, I’m hoping to win the hearts of a full 100 subscribers before the end of Season Two. After all, a fella can dream.

— Tim

(Posts identified as “The Scarlet Pencil” chronicle my meandering through the misty and mysterious quagmire of editing anthologies for Brom Bones Books.)

November 15, 2022

Well, This Helps A Little; Or, Here’s One More Theater Ghost Report from the 1800s

Last week, I discussed how haunted theaters abound these days, so much so that at least one ghost is practically required in any theater older than half a century. And yet I really struggled to find any reports of such buildings in newspapers, magazines, or books from the 1800s. I wondered if the widespread implementation of electricity and, specifically, the custom of keeping on a “ghost light” in theaters inspired specters to buy season tickets — or if perhaps the phantom crew might have resulted from horrific theater fires in the early 1900s.

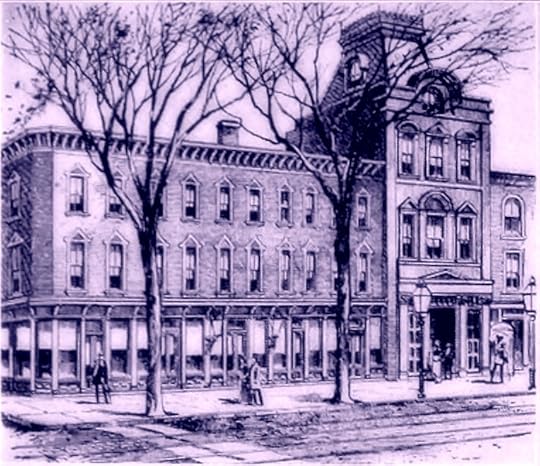

I’m no closer to a solution this week, but my “spirit guide” — by which I mean one of my proofreaders — directed me to a really interesting case of freaky theatrical phenomena from the 1870s. The story goes that the Brooklyn Theater was built on the corner of Johnson and Washington Streets in that borough of New York City. St. John’s church had previously stood there, and it had been one of those churchyards that also served as a graveyard. In other words, quaint and, in my Midwestern American eyes, a bit creepy, too. (We tend to bury our dead on the outskirts of town, thank you very much.) What’s far creepier is the prospect that not all of the corpses had been reinterred elsewhere before the theater was constructed.

The Brooklyn Theater, from

Palmer’s Views of New York, Past and Present

(R.M. Palmer, 1909)

The Brooklyn Theater, from

Palmer’s Views of New York, Past and Present

(R.M. Palmer, 1909)I’ve found confirmation that St. John’s did stand at the corner of Johnson and Washington previously. It’s not unreasonable that some of the buried bodies remained, too. If nothing else, it certainly sets the stage for a drama involving restless ghosts!

A Ghost EntersAccording to an article in the Helena Weekly Herald, Mr. and Mrs. F.B. Conway oversaw the theater, and the wife was worried — not about the disrespected dead specifically — but that “the contemplated enterprise was a desecration of holy ground, and that nothing would succeed there.” Almost inevitably, word spread “that the [play]house was haunted,” and this was supported by untraceable cold drafts that moved scenery and caused creaks. Shortly after the theater opened, Mr. Conway died. Not too long after that, Mrs. Conway died. The article says that, upon this second death,

moans and shrieks were heard in the theater, . . . which so terrified the stage carpenter, stage shifters, and property men, that they all tumbled over each other down stairs and rushed into the street with blanched faces and teeth chattering with fear.

There are no more details of the haunting than that. The article ends by shifting away from ghosts altogether to explain that the Conways died in debt, leading to efforts to raise enough money for their daughters to continue running the theater. Dirty dealings, though, prevented this from happening.

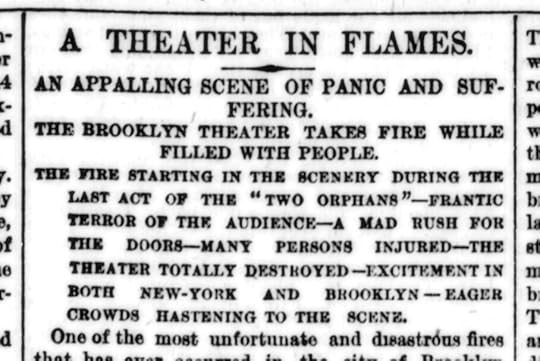

The 1876 Fire From the front page of the December 6, 1876, issue of the New-York Tribune

From the front page of the December 6, 1876, issue of the New-York TribuneOddly, the Helena Weekly Herald article never mentions a terrible fire that had occurred at the Brooklyn Theater a month before! Clearly, that newspaper was only re-printing the information from another one. The same story was also retold elsewhere with the original source cited as the New York Herald. (Frustratingly, I am unable to find the original article, even though issues of the New York Herald are available at the Chronicling America archive. Your help would be greatly appreciated!)

The fire killed about 300 people. In an excellent post on the both the theater’s fire and its ghosts, Chris Woodyard comments on the curious fact that “the ghosts seem to have come before the fire,” relying on yet another reprint of the article mentioned above. He then provides a transcript of a slightly later article, but the interviewees there say they never saw a ghost, and one refuses to say anything at all about it. In fact, the article ends with another shift: away from ghosts and to speculation that some of the human remains unearthed after the fire might have been from the earlier graveyard.

Woodyard then jumps to 1890 with an article about how a rebuilt theater on the site was then being replaced with an office building. By this time, ghosts of the fire victims were said to haunt the place, and those spirits — or, more likely, rumors of them — had driven away patrons. At first, stories were told of spectral actors reenacting scenes from the play being performed when the fire occurred. Next came tales about how

every gallery seat was nightly occupied by the ghost of the person whose life had been lost there in the fire. These disembodied spirits according to this conceit, were usually impalpable alike to sight and touch, and did not hinder the living purchaser of the seat from sitting in it….

It’s pretty goofy stuff, and Woodyard suggests it’s more a product of journalism that’s sensational than of anything that’s supernatural.

In my post of last week, I admit that my search for 1800s reports of haunted theaters left me disappointed. The few reports of ghosts at the Brooklyn Theater have done little to improve my mood. I’m still left wondering why and when today’s proliferation of theater ghosts — pardon the pun — materialized.

— Tim

November 10, 2022

Why Can’t I Find More Old Ghost Reports on Haunted Theaters? WHY???

If charnel-houses, and our graves, must send

Those that we bury back, our monuments

Shall be the maws of kites.

— Macbeth (3.4.70-72)

This weekend’s episode of Tales Told When the Windows Rattle spotlights one of my Vera Van Slyke ghostly mysteries: “The Ghost of Banquo’s Ghost.” In it, Vera and Lucille investigate possible poltergeist activity in a Chicago theater and, specifically, a production of Shakespeare’s Macbeth still in rehearsal.

An illustration from

Macbeth: With an Illustration and Remarks by D–G

(Thomas Hails Lacey, 1860). I splashed it with a few extra colors.

An illustration from

Macbeth: With an Illustration and Remarks by D–G

(Thomas Hails Lacey, 1860). I splashed it with a few extra colors.I introduce this episode by mentioning that I can’t remember ever visiting a theater older than fifty years that didn’t have some kind of ghost story attached to it. But I don’t mention that I once asked a paranormal investigator, after he had snooped around my local community theater, why such places seem so prone to haunting. His answer was concise: “Energy.” (I nodded and let it go at that, wondering why I’ve never heard of a haunted football stadium.)

I figured theaters must have a long and proud history of being haunted. Focusing on the 1800s and using my usual research sites — namely, the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America for newspapers and Google Books for magazines and books — I wound up with unexpectedly disappointing results! Even the best newspaper report I found ends with disappointment:

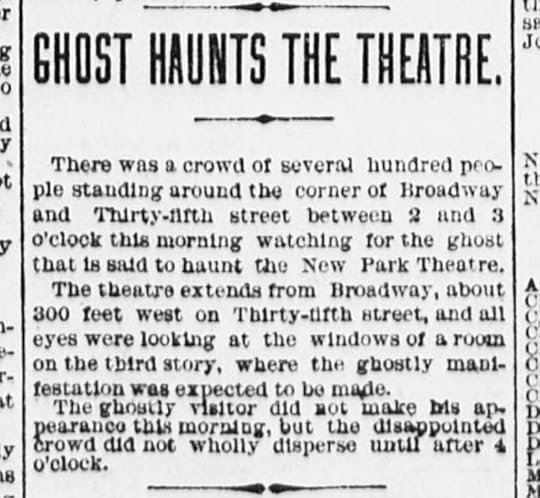

From the front page of the June 22, 1891 issue of New York’s The Evening World.

From the front page of the June 22, 1891 issue of New York’s The Evening World.I wonder if tales of haunted theaters simply became more widespread later. Were they somehow mixed with electric lights and especially the theater tradition of keeping a “ghost light” lit, a practice that presumably would have been too dangerous with candles or gas? Come to think of it, theaters lit by only candles or gas must have been comparatively shadowy places — were they spooky enough without having to add the strange appeal of a ghost-in-residence?

Or is a better explanation found in a series of early-20th-century theater fires?

1903: Chicago’s Iroquois Theatre takes over 600 lives1908: Boyertown, Pennsylvania’s Rhoads Opera House takes about 170 lives1927: Montreal’s Laurier Palace Theatre takes 78 lives1937: Nantong, China’s Nantung Movie Theater takes 658 lives1941: Guadalajara’s Montes Movie Theater takes 86 livesI’m sure there were several other theater fires. And such fires certainly didn’t begin in the 1900s — for example, Kamli, Japan, had one in 1893 that took almost 2,000 lives! These tragedies must surely have cast a macabre pall on theaters everywhere. Did they set the stage for stories about theater ghosts?

In sharp contrast, “The Ghost of Banquo’s Ghost” is one of the lightest of the Vera Van Slyke chronicles. It’s set in 1900, and while I can’t explain why I had trouble finding reports of theatrical ghosts prior to that year, I can warmly welcome you backstage at the Scepter Theatre and invite you to join Vera’s investigation of weird phenomena there. My dramatic reading debuts this weekend, and your complimentary ticket awaits you at the Tales Told YouTube channel.

— Tim

November 2, 2022

An Indication that Newspaper Ghost Reports Truly Were More Prominent in the U.S. than in the UK

Lately, I’ve been stumbling upon interesting connections between my various projects. Last week, for instance, I mentioned how some of the ghost stories I’ve written or anthologized depict residual hauntings — also known by the name “Stone Tape Theory” — which connects with the special interest of recent Ghost Hunter Hall of Fame inductee Robert Hugh Benson (see Honorable Mention). Meanwhile, as I was searching through British newspapers for ghost reports to add to my Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit project, I came upon an article that supports a claim made in my introduction to Spectral Edition: Ghost Reports in U.S. Newspapers, 1865-1917.

My claim there is this: the odd wave of ghost reports published in American papers between this country’s Civil War and its involvement in World War I grew from grief. It was a coping strategy following an unprecedented and still unequaled loss of life in the War Between the States. After all, ghost reports offer evidence — contestable yet rooted in the observable — of an afterlife and of a chance to rejoin the multitude of war dead. In my introduction, I refer to a telling news article from 1865, saying that it gives

a decidedly Yankee perspective on the end of the American Civil War: “Beaten, flying, disorganized, falling into pieces with every mile it moved, . . . the once proud army of Lee had become a mere rabble and rout, and its commander, when he could not save it, surrendered it. In that surrender the rebellion committed suicide. Its ghost may still haunt us for a time, but its life is gone and its deeds are things of the past.” Though speaking figuratively about ghosts, the reporter literally predicted one means Americans used to cope with the terrible loss of life incurred by that rebellion and the war to quell it.

In other words, the ghost reports I present in Spectral Edition were, in part, a product of a specifically American experience. This isn’t to say similar ghost reports didn’t appear in other countries. They did. But probably not to the extent they did here in the States.

Evidence That I Wasn’t Wrong

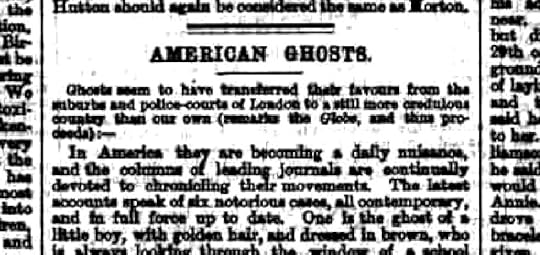

Struggling to find railroad-related ghost reports in UK papers, I found an article there suggesting that ghost reports were much more an American phenomenon. The article was reprinted in several papers in March of 1873, the original source being the London Globe. Titled “American Ghosts,” the article begins:

Ghosts seem to have transferred their favours from the suburbs and police-courts of London to a still more credulous country than our own (remarks the Globe, and thus proceeds):–

In America they are becoming a daily nuisance, and the columns of leading journals are continually devoted to chronicling their movements. The latest accounts speak of six notorious cases, all contemporary, and in full force up to date. . . .

It goes on to summarize the six stateside hauntings. Some I recognize, and some are new to me. Some of them are railroad related, and I’ll be looking into those.

Speaking of railroad hauntings, this Friday’s episode of Tales Told When the Windows Rattle is my reading of “At Ravenholme Junction” (1876).* This short story was probably influenced by Dickens’ “The Signal-Man” (1866), though it’s distinctive enough and creepy enough that I included it in After the End of the Line: Railroad Hauntings in Literature and Lore. On that page, you can see my progress-to-date on the Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit project.

West Virginia’s Hempfield Railroad Tunnel was reported to be haunted in 1869 — and is still said to be so today.

West Virginia’s Hempfield Railroad Tunnel was reported to be haunted in 1869 — and is still said to be so today.You can read the whole “American Ghosts” article here for free. (Thank you, Lyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru/National Library of Wales!) Learn more about Spectral Edition here, and kindly let me read you an eerie tale or two at the Tales Told YouTube channel. If so inclined, you might even consider subscribing to the latter.

— Tim

* “At Ravenholme Junction” was published anonymously and is now sometimes credited to Mary E. Penn. Richard Dalby appears to be the first to contend that Penn wrote it, doing so “on stylistic grounds.” Dalby was certainly a great and admirable scholar, but I get nervously cautious when I see an author given credit because a work seems like — or even smacks of — other works by that author. I want to see the specific reasoning behind this attribution before I repeat it. And — until I’m sweet-talked into selling the movie rights to my Vera Van Slyke Ghostly Mysteries — the book that might or might not present Dalby’s reasoning is beyond my price range.

October 26, 2022

A New Episode of Tales Told and a New Inductee to the Ghost Hunter Hall of Fame — and They’re Connected!

The very special Halloween weekend episode of Tales Told When the Windows Rattle features my reading of Algernon Blackwood’s “A Case of Eavesdropping.” It’s the first of the author’s four Jim Shorthouse tales. Or, at least, what I think most folks would agree is the first story in terms of Shorthouse’s growth as an occult detective.

This one — and another Shorthouse story titled “The Empty House” — both focus on what seem to be cases of residual haunting. These are not ghosts who can be convinced to move on or who can be compelled to leave the haunted site for more suitable digs. Rather, they involve an emotionally charged scene that comes embedded in the actual physicality of the house itself. Back in 1912, Robert Hugh Benson described the phenomena as “like music in a phonograph” in that the original scene is replayed over and over and over, presumably whether or not there’s someone around to experience it. That fact puts an occult detective character in a tricky spot. What is one to do to end the haunting? In both of Blackwood’s stories, Shorthouse really doesn’t do much of anything. I mean — other than leave.

Algernon Blackwood understood that bow ties are cool.

Algernon Blackwood understood that bow ties are cool.Vera Van Slyke faces something like this in “A Burden that Burns,” which is one of the interwoven chronicles in Help for the Haunted. Here, the haunting is ended, though. You see, back in the 1760s, a solider reluctantly decided to set a fire, following his conscience instead of following orders. Ever since, that distraught soldier’s spirit has been caught in a cycle of starting new fires on the same spot. This is compared to making a phone call over and over and over. All one needs to do, then, is pick up the receiver and let the ghost know he did right to defy orders all those years ago. As I say, not quite the same thing. After all, the Vera chronicles focus on how guilt can haunt us as horribly and as persistently as any ghost.

And this fits nicely with “At Ravenholme Junction,” which isn’t a piece of occult detection. Rather, it’s a more traditional ghost story, one I’ll be reading on Tales Told later in the season. In this 1876 tale, the scene of an overworked railway signalman making a mistake that led to a terrible train wreck is reenacted on every anniversary of that event. Like the soldier in “The Burden that Burns,” the railroad worker was tortured by guilt, giving a psychological twist to the haunting.

Robert Hugh Benson felt that dog collars are cool

Robert Hugh Benson felt that dog collars are coolI hope to delve into the history of residual hauntings, since they appear to be fundamentally different from those involving the ghost/spirit of someone who has unfinished business or who otherwise clings to the material world. So far, I know that Benson did a great job of explaining the phenomena in 1912. In fact, for his efforts on this topic, he was recently granted Honorable Mention at the Ghost Hunter Hall of Fame. You can read about that here.

Meanwhile, Blackwood’s Jim Shorthouse series is included in From Eerie Cases to Early Graves: 5 Short-Lived Occult Detective Series, and you can discover more about that here. The page for Help for the Haunted: A Decade of Vera Van Slyke Ghostly Mysteries is here. “At Ravenholme Junction” is in After the End of the Line: Railroad Hauntings in Literature and Lore, the details of which are here. And it doesn’t have to be Halloween for you to enjoy these books!

— Tim

October 19, 2022

Hey, Let’s All Revive Victorian-Style Ghost Hunting, Whadaya Say?

The second season of Tales Told When the Windows Rattle begins on Friday. I open by reading Catherine Crowe’s account of a ghost hunt she conducted, a memoir included in her Ghosts and Family Legends: A Volume for Christmas (1859). By the time this book was released, Crowe was famous for The Night Side of Nature; Or, Ghosts and Ghost Seers (1848), her remarkable compendium of reputedly true reports of paranormal phenomena, specters prominent among them.

Ghosts and Family Legends is perfect for Tales Told because of the way Crowe introduces it. She explains that, as 1857 was drawing to a close, she was a guest “in a large country mansion, in the north of England.” The visitors were enjoying a variety of activities, when “a serious misfortune” altered the mood. They gathered around “the drawing-room fire, where we fell to discussing the slight tenure by which we hold whatever blessings we enjoy, and the sad uncertainty of human life. . . .” However, the topic drifted. Crowe explains:

In short, we began to tell ghost stories; and although some of the party professed an utter disbelief in apparitions, they proved to be as fertile as the believers in their contributions. . . . The substance of these conversations fills the following pages, and I have told the stories as nearly as possible in the words of the original narrators.

If you know my Tales Told series, you know that it is likewise intended to capture something of the centuries-old tradition of sharing gripping stories by an alluring fire during wet or cold weather.

Focolaio domestico, by Francesco Bergamini (1851-1900; date of painting unknown)

Focolaio domestico, by Francesco Bergamini (1851-1900; date of painting unknown)When Crowe’s turn to tell a tale arrives, she narrates her experience of leading a paranormal investigation. It’s fairly representative of Victorian ghost hunts, through I suspect it might’ve had more surprises than was typical. One of the things that intrigues me is the use of a mesmerized clairvoyant to perceive the kinds of things that 21st-century ghost hunters trust to electronic gadgets.

Gizmo-based ghost hunting has never appealed to me, but that’s entirely on me. I can barely get my TV remote to work, and I’ve only recently mastered my iPod. Yes, the notion of a ghost hunter’s bag containing a good novel, a bottle of brandy, and probably a few cigars has greater charm for me than anything involving batteries or wires or even an on-off switch. A loyal beagle by my side is preferable to night-vision googles around my head. Call me old-fashioned.

Maybe, along with the current movement to revitalize the tradition of fireside ghost stories, there should be a push to reexperience Victorian-style ghost hunting. In a way, the Victorian approach to ghost hunting might be better understood as ghost fishing. The serenity of waiting is at least as pleasurable as the thrill of catching. (And did I mention the brandy?) I imagine a lot of people would happily climb onboard that bass boat.

In the meantime, you can subscribe to the Tales Told YouTube channel here.

— Tim