Tim Prasil's Blog, page 14

January 14, 2023

A Minor Gem: Julian Hawthorne’s “The House Behind the Trees”

Julian Hawthorne’s literary career never really got out of the shadow of his revered father, Nathaniel. It’s tough to compete when one’s daddy wrote The Scarlet Letter and The House of the Seven Gables, after all. This is despite the son’s having written considerably more: “He out-published his father by a ratio of more than twenty-to-one,” says Gary Sharnhorst in a biography of the younger Hawthorne.

Sharnhorst also describes Julian as “a writer of modest talent . . . who tailored his tales to the demands of the market in the heyday of sensational fiction.” This is evident in “The House Behind the Trees,” a ghost hunter tale that is, again, probably more interesting for the author’s parentage than for anything regarding the story itself.

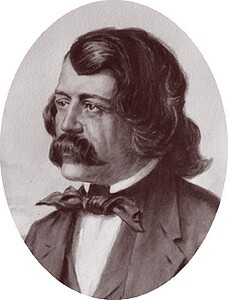

Julian Hawthorne (1846-1934)A Glimmer or Two

Julian Hawthorne (1846-1934)A Glimmer or TwoThat said, “The House Behind the Trees” does have a glimmer or two to make it worth a quick read. The anonymous narrator is chums with a man named Yule. The two, being “rather fond of marvels,” decide to explore a dilapidated house down the road, one with a reputation for being haunted. Hawthorne’s description of the house is fairly routine: long-abandoned, overgrown with weeds, a weathered “For Rent” sign in front. The only twist on their ghost hunt is that it takes place on a sunny summer day instead of a dark and stormy night.

Once that hunt is underway, the story depends on two elements to evoke tension: the initial survey of the house and the backstory to the haunting. I’ll avoid spoilers, but I’ll also say there isn’t much to spoil here. The ending is rather anticlimactic, given that the story had some potential. It was as if Hawthorne were being paid to fill just the one page that contains the story, so he clipped the ending.

Go to the Chronological Bibliography

Go to the Chronological Bibliographyof Early Occult Detectives — 1800s page.

Haunted by Irresolution: ‘Wanted–An Explanation’

“Wanted–An Explanation” is an anonymous novella that appeared in four weekly issues of Household Words during June of 1881. (This journal was a revival of the one Charles Dickens had edited in the 1850s.) The work is an interesting one, and I was very excited as I began reading it. After all, it spotlights one of the rare female supernatural sleuths on my bibliography, Lady Julia Spinner.

Lady Julia is an enjoyably crusty, no-nonsense woman who has never married and probably sees no reason why she should. In some ways, she’s like my own ghost hunter, Vera Van Slyke. She becomes a bit snarky, though, when first hearing that a manor called Hunt House is haunted. You see, Lady Julia is a committed ghost hunter, but very much unlike Vera, she doesn’t believe in ghosts. Serving as narrator, she says:

'I do not believe in their existence at all,' I responded with sharpness. 'I have been a hunter of ghosts all my life, and have never been able even to meet with a single person who has seen one.'In fact, when later called to Hunt House to investigate strange events there, she remains skeptical of supernatural explanations — even after she experiences some very odd sensations herself. This contradiction coupled with her crankiness makes Lady Julia one of the more developed ghost hunter characters I’ve discovered.

A Corner-of-the-Eye PhantomA broken thread appears in the story when we learn how the specter is perceived — or is almost perceived. On the day Lady Julia arrives to investigate the house, she’s in her bedroom unpacking. She speaks to her maid, but she gets no reply.

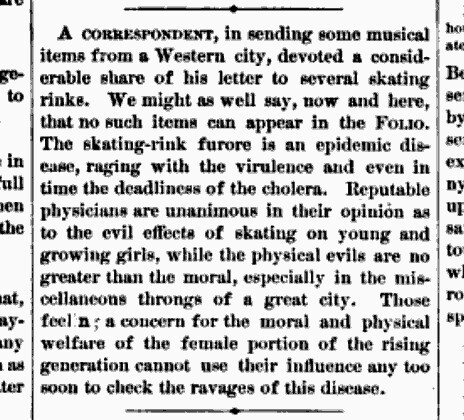

Then I turned round. Beaufort was not there. I was alone. Simple as this was, it positively gave me a shock. Although I had not heard her fidgeting, I could have sworn she was in the room—that well-known, indescribable consciousness of the presence of another identity beside one’s own, with which we are all familiar, had so entirely possessed me.This corner-of-the-eye awareness of the ghostly presence seems to relate to why the new lady of the house becomes enamored with skating. Do the spins and turns Susy Sherbrooke performs on the ice help her to interact with the elusive ghost? Probably not. However, when skating rinks first became popular, some people were very worried that they were a place where young women could freely mingle with men they barely knew! One critic describes the “skating-rink furore” as “an epidemic disease” and a threat to “the moral and physical welfare of the female portion of the rising generation.” And, as we’ll see, improper mingling between the sexes is at the heart of the haunting in this novella.

From Folio 27 (March, 1885) p. 100.Skating as a Parallel of Promiscuity

From Folio 27 (March, 1885) p. 100.Skating as a Parallel of PromiscuityLady Julia discovers evidence of a former resident, and the writer makes this likely villain a foreigner in the fashion of other supernatural novels from about the same time (e.g., Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Richard Marsh’s The Beetle). That is, there’s a strong suggestion that the house is haunted by the ghost of a passionate, swarthy, cloak-wearing, scar-faced Spaniard who had once lived there after eloping with a young, married woman. Susy tells Lady Julia that she keeps glimpsing a “dark, cruel face, the face of the miniature which I found in the cupboard in the little dressing-room,” and that fits the description of the Spaniard. Does his sinful, sexually charged presence linger in the house?

Or do subsequent residents suffer from the curse that this man put on the house? As Lady Julia learns from the local gossip/historian, the villainous Spaniard cursed the house when his lover died: “his were the curses of the wicked; and we all know that curses, like chickens, come home to roost.” Or maybe there’s just bad energy left over from the extramarital elopement itself. No specific final explanation is given for why young wives who move to the house are plagued by madness and their husbands by jealousy. Thus, the title: “Wanted–An Explanation.”

Some readers might find this a disappointment, and it’s not helped by the fact that — just as Lady Julia is about to unravel the riddle — she’s called away. And away she goes! Susy, her friend, is put into far greater danger as a result of this. That’s good for the dramatic tension, I guess, but it seems inconsistent with, if not Lady Julia’s character, then with her role as the story’s detective.

An Important Work with an Unfortunate EndingI worry that I’ve already spoiled things too much, but let me repeat that I found the conclusion unsatisfying in its lack of a confirmed solution to the mystery. It seems as if that title was a way of compensating for the ending instead of, say, signaling that the author was hoping to try something new with how a mystery is resolved. Indeed, perhaps, the reader is invited to do a better job of tying up loose ends than Lady Julia does. Perhaps.

Nonetheless, the theme of wives haunted by urges to commit adultery is rather sophisticated for a Victorian ghost story. In addition, Lady Julia’s characterization starts out strong, and her status as one of the earliest female occult detectives is historically important. These strengths explain why I included “Wanted–An Explanation” in my anthology Ghostly Clients & Demonic Culprits: The Roots of Occult Detective Fiction.

Go to the Chronological Bibliography

Go to the Chronological Bibliographyof Early Occult Detectives — 1800s page.

January 13, 2023

The First American Doctor-Detective?: The Protagonist of “A Needle in a Bottle”

With these words of encouragement and faith, the unnamed doctor/narrator/occult detective in an 1874 short story titled “A Needle in a Bottle” agrees to investigate the mystery of haunted Thornapple Cottage. In some ways, the story is an unremarkable work. After all, it features a haunted house, a hidden treasure, a run-of-the-mill love plot, and even the clandestine machinations of a Catholic cleric. This last staple of Gothic fiction even feels a bit outdated for 1874 — think, for example, of Matthew Lewis’s The Monk from 1796 — though, unlike that earlier work, the later one puts a positive spin on its Catholic character.

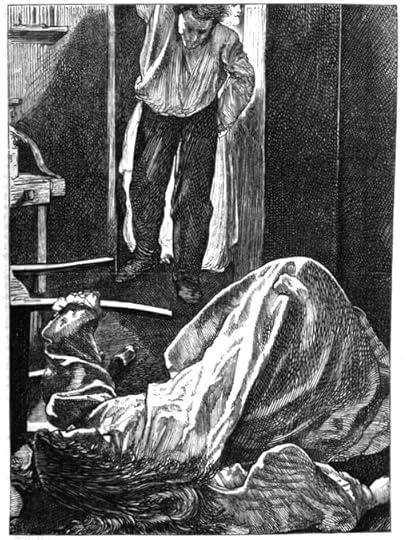

Regardless of its reliance on familiar motifs, “A Needle in a Bottle” is still well worth reading. Some of its spooky images are particularly sharp and weird for the period. The architecture of Thornapple Cottage, for instance, is an odd patchwork of styles, the main section described as looking like a jail while one wing appears “Elizabethan” and the other “Arabeseque.” Once we’re inside the house, the creepy visuals really jump forth, such as when the doctor follows his patient’s gaze to witness this unsettling ghostly manifestation:

Lying upon the floor, in front of a small door in the wainscot, I saw the head, the throat, and a portion of the shoulders of a gray-haired old man. There was no body visible, for below the shoulders the form faded into nothingness. Around the throat were clinched the fingers of a pair of brawny hands, the arms of which were visible only to the elbows, and at no time could I perceive the slightest trace of the form to which they belonged.The description of this strangulation being committed by “amputated” body parts grows far more graphic in the paragraphs that follow. This is one of the reasons I judged the work to be strong enough to be included in my anthology Ghostly Clients & Demonic Culprits: The Roots of Occult Detective Fiction.

A Nice Blend of Supernatural and DetectionWhat I think will especially please fans of occult detective fiction, though, is how this pre-Flaxman Low and pre-Sherlock Holmes tale blends supernatural- and detective-fiction genres. Noted above, the doctor-detective’s previous experience with “supernatural agency” prepares him to approach the case as an actual haunting, not simply a matter of a patient-client suffering from hallucinations. His visit to the site confirms he was wise to proceed in this way. The doctor then uses some very basic, very worldly detective methods to get to the heart of the haunting. In fact, the doctor’s theory about how such things occur might bring to some readers’ minds the electric pentacle of Thomas Carnacki, William Hope Hodgson’s famous occult detective of a few decades later.

An illustration from “A Needle in a Bottle”Another American Occult Detective

An illustration from “A Needle in a Bottle”Another American Occult DetectiveIt’s also interesting that the story is set in and around New York (with a nod to colonial days), and it was published in a magazine from the same city. I can’t know for sure, but it seems likely that the anonymous author was American. In fact, this character is the first American doctor-detective character on my bibliography. E.T.A. Hoffmann’s presumably German Dr. K. leads the list at 1817, and Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s definitely German Dr. Martin Hesselius arrives at 1869. “A Needle in a Bottle” was published in 1874, and it wasn’t until the late 1890s that doctors dabbling in the supernatural really became a convention that led to John Silence, Jules de Grandin, and similar characters of varied nationalities.

As I’ve traced occult detection back to the roots of modern mystery fiction, I’ve been discovering that American writers had an important role. Formerly, critics discussing this cross-genre kept the spotlight on Irish and British authors such as Le Fanu, Bram Stoker, L.T. Mead and Robert Eustace, and E. and H. Heron when naming progenitors. But the emergence of occult detective fiction now appears to be much more a trans-Atlantic effort.

Go to the Chronological Bibliography

Go to the Chronological Bibliographyof Early Occult Detectives — 1800s page.

Re-Licensing Seeley Regester’s Mr. Burton

The Dead Letter was first published in 1866, written by Metta Fuller Victor under her pen name Seeley Regester.. Its detective, Mr. Burton, is one of the founders of a line of diviner-detectives noted on my Chronological Bibliography of Early Occult Detectives. However, in The Dead Witness: A Connoisseur’s Collection of Victorian Detective Stories, Michael Sims takes a negative view of Burton, implying his standard-issue detective’s license should be revoked. Sims says,

Regester’s detective, Mr. Burton, relies on the psychic visions of his daughter. . . . Supernatural or psychic detection has a long history, but it is a category of its own; the intrusion of such irrational plot elements disqualifies The Dead Letter from consideration as a true detective novel.I disagree with Sims’s suggestion that the novel leans too much on Burton’s clairvoyant daughter. While the whereabouts of a prime suspect is determined via this method, the value of this discovery is minimal, since that suspect continues to elude the detective afterward. When the psychic daughter is called upon again later, no results at all are gained. This method of discerning information, then, is far from pivotal to the solution to the mystery.

Learning to Trust a HunchInstead, the clairvoyance acts to encourage readers to consider what probably all occult detective fiction advocates: there’s more to our reality than “rational” investigative methods typically show. This thread of the story is established early, when Richard Redfield, the narrator, tries to sleep after learning about the murder victim. He’s in the house of the victim’s fiancée, and there’s a storm raging outside. “There was something awful in the storm,” he explains, adding, “If I had had a touch of superstition about me, I should have said that spirits were abroad.” In the next paragraph, he reacts to hearing something hitting the window, something other than raindrops: “Ah, my God! I knew afterward what it was. It was a human soul, disembodied, lingering about the place on earth most dear to it.” In a way, the novel is the story of young Redfield’s growth from skeptic to believer.

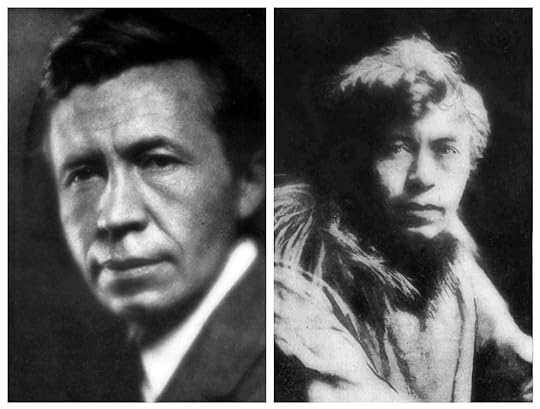

Metta Victoria Fuller Victor, a.k.a. Seeley Regester (1831–1885)

Metta Victoria Fuller Victor, a.k.a. Seeley Regester (1831–1885)This is especially true in regard to Redfield’s trusting his own intuition. Along with having a blatantly clairvoyant daughter, Burton is himself very intuitive. At the novel’s conclusion, he explains that he has an ability that “enables me, often, to feel the presence of criminals, as well as of very good persons, poets, artists, or marked temperaments of any kind.” Only a few pages earlier, Redfield confesses that he, too, had sensed who the guilty party was, but “I had always tried to drive away the impression.” In that Burton acts as a sort of mentor to Redfield, it seems that trusting one’s gut is a key lesson for both the narrator and for readers.

Learning to Maintain BalanceBut Regester keeps this idea of a psychic/supernatural reality in balance. Along the way, Redfield enlists Burton’s aid in probing what appears to be a haunted house. It turns out there’s a natural explanation to the spooky glow and noises, though — one connected to the murder mystery. In fact, other than the dicey use of clairvoyance, this novel is very much a straightforward murder mystery. Granted, there are some rather remarkable coincidences, but even here Regester attributes such things to a reality that exceeds the boundaries of science. As Redfield remarks in one such instance, “How curious are the ways of Providence! It seems as if I received help outside of myself.”

An illustration from the first book publication of The Dead Letter: An American RomanceBurton’s Ancestry

An illustration from the first book publication of The Dead Letter: An American RomanceBurton’s AncestryJust as interesting is how the detective character Burton seems to be a descendant of Henry William Herbert’s Dirk Ericson. Both characters are Americans, and while Herbert attributes his detective’s skills at tracking and at reading visual evidence to his being a frontiersman, Regester uses similar imagery to introduce Burton:

He was like an Indian on the trail of his enemy – the bent grass, the broken twig, the evanescent dew – which, to the uninitiated were ‘trifles light as air,’ to him were 'proofs strong as Holy Writ.'Furthermore, in another post, I point out that patience stands out as a key characteristic of Ericson and at least one other fictional detective from his era. Over two decades later, Regester made a patient disposition vital to Burton’s eventual success in the case. The character declares, “I’ve told you my motto – ‘learn to wait,’ Richard. The gods will not be hurried.”

Sherlock Holmes’ Ancestry?Perhaps more surprisingly, some aspects of Burton resurface in none other than Sherlock Holmes. For instance, while Holmes has made himself an expert in crime-related minutia, such as the identification of various kinds of tobacco ash, Burton has refined his abilities in chirography, which he explains is “the art of reading men and women from a specimen of their handwriting.” Furthermore, anyone who knows Holmes’ relationship to Irene Adler will recognize something in this passage from The Dead Letter regarding Burton’s past cases:

He who had brought hundreds of accomplished rogues to justice did not like to be foiled by a woman. Talking on the subject to me, as we sat before the fire in his library, with closed doors, he said the most terrible antagonist he had yet encountered has been a woman -- that her will was a match for his own, yet he had broken with ease the spirits of the boldest men.Perhaps, to Mr. Burton, she is always referred to as the woman.

For these reasons, I found The Dead Letter a very interesting read. Be warned that there is some stupid racism toward the end (e.g., “Not that all Spaniards are necessarily murderers — but their code of right and wrong is different from ours”). Nonetheless, the character development, the complex plot, the winding adventure, even the language being quite accessible for readers 150 years later all add to the pleasure of this novel. I recommend the Duke University Press reprint, which is edited by Catherine Ross Nickerson. Along with her useful introduction, this edition comes coupled with The Figure Eight, another of Seeley’s mysteries.

Go to the Chronological Bibliography

Go to the Chronological Bibliographyof Early Occult Detectives — 1800s page.

January 12, 2023

To Investigate Matters Otherwise Quite Beyond My Province: Charles Felix’s Ralph Henderson

I learned about The Notting Hill Mystery (1862), written by Charles Felix (the psuedonym of Charles Warren Adams), from a review written by J.F. Norris. Norris is a mystery aficionado who has suggested to me some of the more obscure works now on my Chronological Bibliography of Early Occult Detectives. Notting Hill is especially important because of its prominent place in the history of mystery fiction: it is among the very first detective novels written in English. It’s also one of the key works of mystery fiction that presents a detective character who must come to accept supernatural involvement in order to solve the mystery. This, in brief, is my test for an occult detective.

In his review, Norris describes the book as “a detective novel and a true mystery,” one including a murder that “can only be classified as supernatural.” What I didn’t realize was how pivotal that supernatural murder is to the other events in the story. It depends on taking advantage of a link between twin girls that goes beyond the psychological, beyond even the psychic. As Felix clarifies early in the novel, the twins’ connection is downright physical. One of the case’s witnesses reports that “every little ailment that affects the one [sister] is immediately felt also by the other. . . . I have often heard of the strong physical sympathies between twins, but never met myself with so marked an instance.”

An Easy-to-Spot VillainIn a sense, the mystery explores how this connection might be exploited by an unsavory blackguard. Unfortunately — yet far from unprecedented in early mystery fiction — that unsavory blackguard is easy to spot. I discuss two tales from the 1840s, both with hard-to-miss villains, on this page. When reading this 1862 novel, kindly avoid looking too closely at the Mesmerist with the penetrating eyes. You know, the fellow who, in the first quarter of the novel, inspires one of the twin sisters to write in her diary: “I don’t think he would have much compunction in killing any one who offended him, or stood in his way.”

An illustration from the first serial publication of The Notting Hill Mystery in Once a Week

An illustration from the first serial publication of The Notting Hill Mystery in Once a WeekNow, hypnotism is a scientifically validated phenomenon. But one could argue that its depiction here extends fairly far into the supernatural. That’s an element of this novel that might disappoint some readers hoping for fully formed occult detective fiction. Yes, there’s a proto-Svengali villain with sinister motives and esoteric knowledge, but there are no union-certified vampires or werewolves. Not even a tattered ghost dragging so much as a paper-clip chain.

A Detective Accepting a Wider RealityNonetheless, the detective character fits well with what I term a novice occult detective. In keeping with that category, Felix’s detective finds he must expand his understanding of reality to encompass what strict science would snub as impossible. A life insurance investigator, Ralph Henderson opens the presentation of his solution to the case by admitting that he’s out on a limb. The “Mesmeric Agency” so central to the crime is something he knows will be met with skepticism. And it is! Still, he bravely advances it as “the only theory by which I can attempt, in any way, to elucidate this otherwise unfathomable mystery.” Instead of FBI agent Fox Mulder’s famous UFO poster with the slogan “I WANT TO BELIEVE,” insurance agent Henderson’s poster might read: “I’M FORCED TO BELIEVE.”

Let me close by saying that J.F. Norris’s blog Pretty Sinister Books is tailor-made for readers seeking mystery fiction they didn’t know they wanted to read. He discusses The Notting Hill Mystery and dozens, maybe hundreds, of other novels.

Go to the Chronological Bibliography

Go to the Chronological Bibliographyof Early Occult Detectives — 1800s page.

Crossing Great Distances: Bayard Taylor’s “The Haunted Shanty”

American writers played a key role in establishing the occult detective cross-genre. There’s Henry William Herbert’s “The Haunted Homestead” (1840), set in the New Hampshire/Vermont region. Fitz-James O’Brien wrote two Harry Escott stories (1855 and 1859), both set in New York. And there’s Bayard Taylor’s “The Haunted Shanty,” set on the Western frontier. Of course, since this story is from 1861, that frontier is still in the prairies of Indiana and Illinois instead of the plains of, say, Oklahoma or the Dakotas.

Warning: there be spoilers ahead.

Eber Nicholson, a key character, hasn’t pushed west so much as was pushed west — by guilt. He left a woman named Rachel Emmons behind, the woman he loved. His strict father disapproved and demanded Eber marry a more financially secure woman. And so Eber did. But now Rachel Emmons haunts him. Psychologically and supernaturally. In spirit and in spirit!

If that isn’t trouble enough, it turns out that Rachel Emmons isn’t dead yet. Yes, her “ghost” visits Eber with growing frequency. But she isn’t dead.

A Duty-Driven DetectiveThis is the situation Taylor’s unnamed narrator stumbles upon after becoming lost during a business trip to Peoria, Bloomington, and Terre Haunt. The narrator experiences the ghostly manifestation himself and probes the mystery on the assumption that Eber must have murdered Rachel. When he learns he’s met the ghost of a living person, he’s too mystified not to investigate the matter more thoroughly!

Bayard Taylor (1825-1878)

Bayard Taylor (1825-1878)Here’s where the traits of an occult detective appear. The narrator is a neutral party in the haunting. Nonetheless, after interrogating Eber Nicholson, he goes far out of his way to interview Rachel Emmons. During his investigation, he acts as a consultant, giving his best advice to resolve the haunting. Some of Taylor’s language paints the narrator as almost a doctor-detective. He diagnoses the problem as “a spiritual disease” but is frustrated by feeling “incapable of suggesting any remedy.” This inability makes the character a novice-detective rather than a doctor-detective.

Facing the UnfathomableThis inability also leads to my one hesitation in including this character on my list of occult detectives: the character acting as detective doesn’t solve the mystery. There is resolution in the story. However, after being quite active in the investigation, Taylor’s narrator is terribly passive when it comes to actually doing something about it. This is an important element of the story, though — that feeling of being helpless before an unfathomable mystery. Harry Escott knows the feeling. Harry never really figures out what it was in “What Was It: A Mystery,” a tale by Fitz-James O’Brien that was published two years before “The Haunted Shanty.”

And both Taylor’s narrator and O’Brien’s Escott are in good company. In “The Problem of Thor Bridge” (1922), Dr. Watson mentions that even Sherlock Holmes didn’t solve all of his cases:

Some, and not the least interesting, were complete failures, and as such will hardly bear narrating, since no final explanation is forthcoming. A problem without a solution may interest the student, but can hardly fail to annoy the casual reader.Not as Bad as All ThatSuch annoyance might have been felt by the reviewer who, in an 1861 issue of The New York Times, describes “The Haunted Shanty” as “a modified ghost story, . . . which we do not like at all. The author assures us that it is true, and we do not doubt the assertion — it is certainly dull enough to be so.” Ouch! I disagree. I found the tale to be clever and creepy, a nice variation on the familiar lost-traveler-sleeps-in-a-haunted-room theme. Its setting of pioneer-era Illinois and Indiana also fascinated me, though this might be due to my being from that region.

Go to the Chronological Bibliography

Go to the Chronological Bibliographyof Early Occult Detectives — 1800s page.

Dirk Ericson: America’s First (Occult) Detective?

When Nina Zumel from Multo (Ghost) suggested I read Henry William Herbert’s “The Haunted Homestead” to see if it qualifies as occult detective fiction, I was skeptical. This story was published in 1840 as three installments: “The Murder,” “The Mystery,” and “The Revelation.” Edgar Allan Poe’s C. Auguste Dupin, who’s often named as the first fictional detective, didn’t appear in print until 1841, and I was working on the false assumption that fictional detectives would have to be fairly well established before occult detectives could be introduced. I, therefore, looked for ways to disqualify Herbert’s Dirk Ericson.

Discovering that I couldn’t disqualify Ericson inspired me to pin down what I hope is a reasonable definition of occult detective fiction. Basically, it’s this: mirroring the qualities of other fictional detectives from the same era, a key character accepts the reality of phenomena commonly called supernatural and, thereby, solves a central mystery.

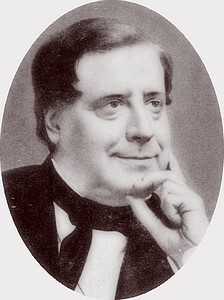

Henry William Herbert (1807-1858)

Henry William Herbert (1807-1858)Ericson clearly displays some basic traits of fictional detectives yet to come. He’s very skilled at drawing logical conclusions about a crime from physical evidence. He leads a murder investigation, and when that’s thwarted, supernatural activity prompts him to switch from gathering evidence to keeping a prime suspect under surveillance. Ericson is a particularly American detective in that he got his expert eye, his stalking skill, even his leadership talents from the “woodcraft” of surviving on the frontier. One might call him the Natty Bumppo of detectives.

Comparing Ericson to His ColleaguesBut does Ericson reflect characteristics of other fictional detectives from his own era? I decided it was time to explore works that have been suggested as beating Poe’s debut detective story for the title of the first piece of detective fiction. For example, Catherine Crowe’s Susan Hopley; or, Circumstantial Evidence (1841) has been described by Lucy Sussex as “a novel with three female detectives, and centred on a murder mystery, [published] four months before Poe’s ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’.” However, it’s only one of a number of works that have been offered as pre-Poe detective fiction, notably, Voltaire’s Zadig, or The Book of Fate (1748), Godwin’s Caleb Williams (1794), Hoffmann’s Mademoiselle de Scudéri (1819), and the anonymous Richmond; Or, Scenes in the Life of a Bow Street Officer, Drawn Up from His Private Memoranda (1827).*

Another story that challenges Poe’s status as writer of the first detective story is William Evans Burton’s “The Secret Cell,” which appeared in two parts in September and October of 1837. Though published in Philadelphia, the story is set in London. The urban setting is only one of its contrasts with Herbert’s “The Haunted Homestead,” which is set in rural New England. Burton writes about a kidnapping case handled by a police official identified as L—. In fact, the tale might even be considered a police procedural despite its romanticized elements. In contrast, Herbert uses an amateur detective and something closer to what would become called a whodunit format — both elements that Poe continued in the first two Dupin stories. Poe also borrowed Burton’s use of a first-person narrator who assists the detective. Only Herbert uses third-person narration.

William Evans Burton (1804-1860)

William Evans Burton (1804-1860)Despite their contrasts, Burton’s and Herbert’s stories have some common traits, and it’s here that Ericson’s adventure clearly reflects other detective fiction of the same era. For instance, L— and Ericson work a lot harder than readers to recognize the culprit. Early in “The Secret Cell,” we meet “an hypocritical hyena of a niece” who “raved and swore the loudest revenge” upon learning that the inheritance she was counting on would be given to Mary Lobenstein, who becomes the kidnapping victim. Likewise, in the first part of “The Haunted Homestead,” Cornelius Heyer is described as “a tall, dark-visaged, gloomy-looking man, wearing a long and formidable butcher-knife in his buff belt.” Heyer offers to guide a young, aristocratic-looking man known only as “the traveler” over rough terrain and through stormy darkness. At one point, Cornelius says he’ll head home and gives the traveler directions that, at the first bridge, would take him off “the most traveled route.” Lo and behold, the traveler is attacked, recognizing “the dark visage and the gloomy scowl” as well as “the glitter of the long butcher-knife” of the man who kills him.

Readers are pretty certain who that is, but yeah, it could be coincidence or perhaps someone disguised as Heyer. Heyer’s twin brother? Herbert goes on to describe the criminal’s subsequent actions — but clumsily avoids stating a name outright. Oddly, Herbert never absolutely confirms that Heyer is the culprit in the end, leaving us only 99% sure we know it was him. Clearly, the whodunit was something very new. And remember that in “The Purloined Letter,” the third Dupin story, there’s almost no doubt of who the culprit is. Rather than unmask the culprit, the detective’s challenge is to outsmart him and retrieve the purloined letter.

Shared Detective StrengthsMore importantly, Burton’s L— and Herbert’s Ericson share some defining characteristics. First, both are good trackers who persist despite a few false steps. After disguising himself to follow up a lead, L— tracks a man named Joe through the London streets to a phony monastery, where people are held against their will. But where is Mary Lobenstein? Meanwhile, Ericson tracks the muddy hoof prints of the traveler and Cornelius to see that they did indeed part ways. He manages to see that the traveler did not continue on the main path after reaching the bridge. But where is the corpse?

Second, both L— and Ericson are good team leaders. The former takes the narrator and several others with him to the phony monastery. Ericson takes his reliable Allen brothers and several others to track the traveler’s horse. This is a curious contrast to Poe’s Dupin, who pretty much works alone, letting the mostly useless narrator tag along. Third, both L— and Ericson know that patience can help solve a mystery, be it the couple of days that L— spends disguised in a bar or the night-after-night that Ericson and the Allen brothers devote to keeping their prime suspect under watch. Fourth, both have an eagle eye that leads to the final step in solving the mystery. L— uses a spaniel to help track where Mary Lobenstein is being confined, but once that dog loses the scent, he spots something all the others in his posse miss: a large padlock on the sliding lid over a cucumber bed in a greenhouse. The oddness of keeping one’s cucumbers under lock and key inspires the detective to grab a crowbar and break open the lid, beneath which lies a room hiding the kidnapping victim. At the close of “The Haunted Homestead,” Ericson’s keen eye spots a patch of snow shaped like a body on Heyer’s property. Knowing the dynamics of melting snow, the detective calls for axes and crowbars, which in turn uncover the corpse of the traveler.

Poe Knew about Burton and HerbertPoe knew of both of these writers’ work. He worked for Burton at Gentlemen’s Magazine, in which “The Secret Cell” was published. But it was in Graham’s Magazine that he described Herbert’s work as being “sometimes wofully turgid.” In addition, “The Mystery of Marie Roget,” the second Dupin tale, was published in The Ladies’ Companion, where Herbert’s “The Haunted Homestead” had appeared two years earlier (and one year before the first Dupin story appeared in Graham’s). It’s possible that either or both of these works spurred Poe to see if he could write a better detective story.

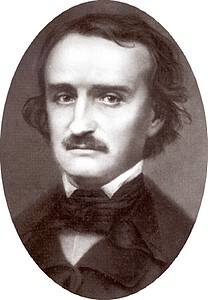

Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849)

Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849)I hope that critics take a closer look at Herbert’s “The Haunted Homestead” when considering detective fiction that precedes Poe’s Dupin stories. Was Dirk Ericson the first American detective in fiction? L— is English, after all, and Dupin is French. Equally intriguing, since the supernatural has an important role in “The Haunted Homestead,” it appears that occult detective fiction didn’t follow detective fiction. Instead, occult detective fiction helped create detective fiction.

*It’s also worth noting that, in 1838-39, Burton ran a series titled “Unpublished Passages in the Life of Vidocq, the French Minister of Police” in his Gentleman’s Magazine. Despite its use of Vidocq, the name of a real police official, this presumably fictional series includes “No. I: Marie Larent,” “No. II: Doctor D’Arsac,” “No. III: The Seducer,” “No. IV: The Bill of Exchange,” “No. V: The Strange Discovery,” “No. VI: The Gambler’s Death,” “No. VII: Pierre Louvois,” “No. VIII: Jean Monette,” and “No. IX: The Conscript’s Revenge.” Interestingly, the very first case involves a character named Dupin!

Go to the Chronological Bibliography

Go to the Chronological Bibliographyof Early Occult Detectives — 1800s page.

January 11, 2023

Is E.T.A. Hoffmann’s Dr. K. Too Early to Be an Occult Detective?

The literary roots of occult detective fiction can be traced back at least as far as the Classical Period and the writings of Pliny the Younger and Lucian of Samosata. Those writings, in fact, establish the two main branches explored in my anthology Ghostly Clients & Demonic Culprits: The Roots of Occult Detective Fiction. And yet the term early in my Chronological Bibliography of Early Occult Detectives means something centuries later than that. To be sure, it starts in 1817, the year that E.T.A. Hoffmann’s “The Mystery of the Deserted House” (a.k.a. “The Deserted House”) was first published in German.

I guess what I mean by early, then, is in relation to occult detective characters as they appear in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. The characters on my list are recognizable ancestors of Carl Kolchak, Agents Mulder and Scully, or Sam and Dean Winchester. Even Buffy Summers or Harry Dresden can trace their roots pretty directly to the characters on my list.

This raises the question: does Dr. K., Hoffmann’s character who resolves the supernatural dilemma in “Deserted,” really qualify as an occult detective at all? Is he simply too early? Well, it’s open to debate.

On the One Hand…It might be helpful to think of Hoffmann’s tale as working its way toward occult detection. After stumbling upon a strange house and increasingly becoming obsessed with it, the protagonist takes his troubles to Dr. K. This physician, we learn, “was noted for his treatment of those diseases of the mind out of which physical diseases so often grow.” Despite this very earth-bound description, the doctor quickly reveals that he accepts the supernatural as part of his diagnosis process. He trusts both psychometry (receiving psychic impressions from a physical object) and mind-to-mind clairvoyance, the latter by placing his hand on the patient’s neck to share his vision of a face in a mirror.

In other words, to gather evidence, Dr. K. accepts the supernatural as real. This acceptance of what’s possible also allows him to later identify the source of the villain’s power and, thereby, to solve the mystery. At its core, then, “Deserted” seems to fit the genre-blending of supernatural and detective fiction pretty well,

But on the Other…That said, detective stories typically tend to focus on the investigator, who meets with a client and then pieces clues together into a history of a crime, one revealing the culprit. A lot of occult detective tales follow the same pattern: the main character meets with a client and then goes to work. However, “Deserted” follows the pattern of many, many supernatural tales by focusing on a protagonist who gradually comes to suffer from an otherworldly experience. Simply put, Hoffmann introduces his occult detective late instead of early, and that might raise an eyebrow.

Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann (1776-1822)

Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann (1776-1822)The other eyebrow might go up, too, because — once Dr. K. finally gets involved — his investigation happens “offstage” while the narrative focus remains on the client. We don’t see this with subsequent clairvoyant doctors, such as Drs. Xavier Wycherley, John Durston, and John Richard Taverner. Stories with these characters usually follow the standard detective-story tradition of narrating the step-by-step investigation of the mystery. Can a work of occult detective fiction downplay the role of the mystery-solver to the extent that Hoffmann does here?

Examples of the Offstage DetectiveThere are examples of detective fiction downplaying the role of the investigator. One might remember that Sherlock Holmes remains surprisingly out-of-sight in The Hound of the Baskervilles (1902). Of course, there, the detective debunks the supernatural.

Regarding truly occult detective fiction, Algernon Blackwood’s “Ancient Sorceries” (1908) is a John Silence tale that bears enough fundamental similarity with Hoffmann’s “Deserted” that a case could be made for Hoffmann having been a direct influence on later author. Both works feature a patient who goes through a traumatic haunting involving a woman with mystical powers, and relating the details of this takes up the bulk of the story. Both doctors are clairvoyant, and both disappear to conduct an investigation. In classic detective story fashion, though, both tales end with the doctors reappearing to provide the big reveal, meaning they recount the history that explains the haunting. Curiously, neither doctor can do very much to defeat the witchy woman who has cast a spell over the patient. Neither story ends with a splashy exorcism or a grandiose staking of the vampire. They both just sort of — end.

When Algernon Blackwood wrote “Ancient Sorceries,” was he under the spell of E.T.A. Hoffmann’s “The Mystery of the Deserted House”?Final Ruling: Dr. K. Qualifies

When Algernon Blackwood wrote “Ancient Sorceries,” was he under the spell of E.T.A. Hoffmann’s “The Mystery of the Deserted House”?Final Ruling: Dr. K. QualifiesThat being so, while “Deserted” is in some ways not typical of a detective or occult detective story, Dr. K. clearly stands as a founding member of the doctor-detective branch of occult detective fiction. (In fact, I see him as a far more impressive doctor-who-treats-occult-ailments than Sheridan Le Fanu’s Dr. Hesselius.) Perhaps this isn’t quite so surprising when considering that Hoffmann frequently used Gothic elements in his fiction. He’s often named as an influence on Poe, and fittingly, Hoffmann’s Mademoiselle de Scudéri (1819) has been seen by some critics as a pre-Poe work of detective fiction. With this in mind, the claim that Hoffmann combined supernatural fiction and early detective fiction to create one of the very first occult detectives in “The Mystery of the Deserted House” seems rather mild.

This is why, despite his being so very early an early occult detective, Dr. K. remains at the top of my roster.

Go to the Chronological Bibliography

Go to the Chronological Bibliographyof Early Occult Detectives — 1800s page.

January 9, 2023

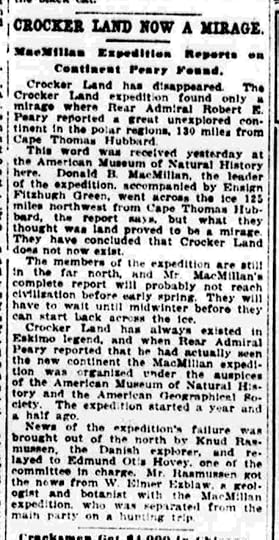

Was It All an Arctic Apparition — or a Cold Calculation?

For decades following Donald MacMillan’s 1914 report that no land existed where Robert Peary had observed it in 1906, Crocker Land was deemed a mirage. In 1916, Edwin Swift Balch turned from supporting Crocker Land to echoing the mirage theory in a letter to the editor the Scientific American, and according to a 1939 newspaper article, expedition leader Clifford MacGregor also agreed with that explanation. As late as 1950, in The White Continent: The Story of Antarctica, Thomas R. Henry addressed how polar atmospheric conditions can produce optical illusions, and Peary’s sighting illustrates this point: “It was not until nearly twenty-five years later that ‘Crocker Land’ north of Ellesmere Island — reported in 1906 and thought by some to be a land mass of continental proportions — was proved a myth. But nobody ever questioned that Peary was an honest and accurate reporter” (pg. 43).

Henry was overgeneralizing about Peary’s public persona. Way back in 1915, the papers were reporting that, for some, his trustworthiness was deeply in doubt. When Congress conferred the rank of rear admirable upon Peary for having reached North Pole, Representative Henry T. Helgesen launched a challenge. The evidence of Peary’s accomplishment was little more than his own word, Helgesen argued, and several other claims by the explorer had been proven false. Crocker Land is among those claims. Helegesen’s argument was reprinted in a 1916 newspaper article, and there he says this history of making false claims destroys Peary’s “reputation for veracity” and leaves no reason to trust “at any time he has been anywhere near the Pole.” Helgesen also uses many of these points in a speech to have Crocker Land removed from government maps.

A century later, it’s become fairly commonplace to portray Peary as having intentionally fabricated Crocker Land. Probably the most prominent raised eyebrow belongs to historian David Welky, whose book A Wretched and Precarious Situation: In Search of the Last Arctic Frontier narrates and analyzes MacMillan’s expedition. In an interview with Simon Worrell for the National Geographic, Welky sets forth his reasons for following Helgesen’s lead in thinking Crocker Land was all a ruse:

Peary was too experienced in Arctic exploration to have mistaken an ice island or a mirage for solid land;there’s no mention of spotting land in the detailed notes Peary wrote during the expedition, nothing in the diaries kept by those who had accompanied him, and nothing in his correspondence for months afterward;there’s likewise no mention of his astounding discovery in the early drafts of Nearest the Pole or a magazine article, both of which recount the trip on which he supposedly spotted the landmass. “In other words,” says Welky, “sometime between the final manuscript and when the book comes out the paragraphs about Crocker Land mysteriously appear.”This is compelling stuff that makes counterargument tough. I have no new direct evidence that sheds any light on whether or not Peary was lying. To be sure — if a winter in the Arctic Circle were held to my head — I’d say, heckyeah, Crocker Land was a fabricaion! Well, probably. You see, I remain troubled by a few things. The best I can do is add some historical context and track Peary’s response to MacMillan’s report in the hope of showing the debate isn’t (or shouldn’t be) settled yet. My goal, then, is to deflate, if only slightly, the confidence with which Peary is sometimes portrayed as a brazen liar.

Naming Land After an Expedition FinancierAt first glance, Peary’s decision to name the land as he did seems designed to appease George Crocker, the millionaire who had contributed bags and bags of money to the very expedition during which the famous explorer says he spotted uncharted land. Was Peary cajoling Crocker to donate more bags of money for his next attempt to reach the North Pole? It feels likely.

However, when Peary allegedly first spotted that land to the north-northwest, he was standing on Cape Colgate, which sits close to the shore of Ellesmere Island. Once upon a time, this island was divided into Grant Land to the north, Ellesmere Land to the south, and Grinnell Land in the middle. The latter was named by Edward De Haven for Henry Grinnell, the shipping magnate who had financed the 1850 expedition that had come upon it. When Peary then crossed Nansen Sound, climbed Cape Thomas Hubbard, and again allegedly spotted land in the same direction as before, he was on what is now called Axel Heiberg Island. This was named by Otto Sverupt for a brewer of that name who had sponsered his 1900-01 expedition. Of course, these landmasses were real. But when Frederick Scott also believed he saw land when trekking toward the North Pole in 1907 — land subsequently proven to not existent — he named it for financial backer John R. Bradley.

To be sure, there are various ways that Arctic lands were named (or renamed if any indigenous names were being ignored). The “phantom” Plover Land was named for a ship, for instance, and the very real Victoria Island was named for the Queen of England. My point, though, is that naming Arctic land for one’s financial supporter isn’t automatically a suspicious act. In fact, it’s something of a tradition.

A Sea Change in the Wake of MacMillan’s ReportNovember 23, 1914, is a pivotal date in the history of Crocker Land. That’s when a letter arrived at the American Museum of Natural History, one written by Walter Elmer Ekblaw. He was a member of MacMillan’s expedition to determine if Crocker Land were real (along with various other goals), an undertaking largely financed by the Museum. As paraphrased in its annual report, Ekblaw says MacMillan and Fitzhugh Green “journeyed 125 miles northwest from Cape Thomas Hubbard across the ice of the Polar Sea in a search for Crocker Land. For two days Messrs. MacMillan and Green thought that they saw land, but this proved to be a mirage, and they finally concluded that Crocker Land does not exist, at least within the range originally ascribed to it.” It didn’t take long for the news to hit the papers, from New York to Iowa to Arizona.

From the November 25, 1914, issue of The Sun, a newspaper published in New York. As discussed below, saying that Peary had reported a “continent” is very misleading.

From the November 25, 1914, issue of The Sun, a newspaper published in New York. As discussed below, saying that Peary had reported a “continent” is very misleading.The announcement published in Arizona, which is marked as a reprint from the Philadelphia Press, ends by saying:

Scientists will probably agree that the discovery that there is no Crocker Land is in itself important enough to have justified the MacMillan expedition and to compensate it for the difficulties of its journey. If a mirage has actually been mapped in the Polar sea, it is to the interests of mankind that the error be rectified. Nor should there be any question of the good faith of Rear Admiral Peary. His reputation as an explorer and scientist places him above suspicion.As we’ve seen, Representative Henry T. Helgesen was among the first to chip away at Peary’s good reputation in the wake of MacMillan’s report. He wasn’t alone, though. Peary’s fellow — and rival — explorer was Frederick Cook. The news from MacMillan apparently soured his view of Crocker Land, too. (Cook’s view of Peary’s character had already soured after announcing that he had beaten Peary to the North Pole. Cook found himself bombarded with accusations of fraudulence, most them traceable to Peary. That’s an immense, complicated topic that would quickly snowball beyond my focus here.)

Here’s a chart of Cook’s gradual shift from at least tentatively accepting Peary’s claim about Crocker Land to strongly refuting it.

September – October, 1909 – Cook’s narrative of his journey to the North Pole was being published in newspapers across the U.S. In the seventh installment, he recounts looking west and seeing “an outline suggestive of land. This we believed to be Crocker Land, but mist persistently screened the horizon and did not offer an opportunity to study the contour.” In the eighth installment, Cook claims to have seen a surprisingly long coastline to his west. “The land as we saw it,” he explains, “gave the impression of being two islands, but our observations were insufficient to warrant such an assertion.” He describes the land as made up of ragged mountains “perhaps eighteen hundred feet high. . . . The lower shore line was at no time visible. This land is probably a part of Crocker Land.” (In the ninth installment, readers learn that Cook named this Bradley Land. By December, this landmass was already being deemed a myth.)

September 30, 1911 (as Cook battled Peary for “First to the Pole”) – A newspaper article quotes Cook as saying: “Peary’s Eskimo companions…positively deny Peary’s claimed discovery of Crocker Land. I still prefer to prefer to believe that Crocker Land does deserve a place on the map.”

December 3, 1914 (about a week after MacMillan’s report had hit the papers) – A newspaper article quotes Cook as saying, “I have claimed for five years that there is no such place as Crocker Land.”

Thanks to digital newspaper archives, we see that Cook had 1) claimed that he believed he might’ve seen Crocker Land, 2) connected it to his own Bradley Land, and 3) defended its place on the map — all within the five years that he then claimed to have been denying its existence. He saw the MacMillan report as an opportunity to discredit Peary while bolstering his own credibility.

Contrary to some reports, Peary’s reputation was becoming tarnished, if not corroded, first by his thinly supported claim to have reached the Pole and now by the discovery that Crocker Land was not there.

Peary’s Reaction to MacMillan’s Early ReportWelky did another interview with Tom Porter for Bowdoin College’s website. Here, the historian points out that, if Peary were hoping to bamboozle Crocker, it didn’t work: “Any hopes he may have had of George Crocker funding a further trip were effectively destroyed in the rubble of the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, after which Crocker plowed all his money into rebuilding the city.”

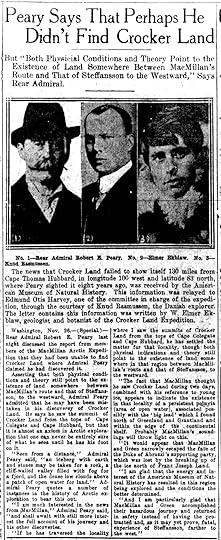

This means that Peary would have known his ruse had failed years before MacMillan’s expedition to verify Crocker Land departed in 1913. When MacMillan’s early report arrived toward the end of the following year, Peary was given the perfect opportunity to shrug off the whole thing and to simply agree that he had seen a mirage. It even mentions that, while seeking the landmass, MacMillan and Fitzhugh Green had themselves experienced a mirage! What a gift! Indeed, Peary came close to accepting this explanation of what he saw.

From the November 2, 1914 issue of the Star Tribune, a newspaper published in Minneapolis. The phrase “physical conditions and theory” almost certainly nods to Rollin Harris’s influential theory — based on currents, old ice, and tides — that a significant landmass exists in the Arctic. Harris introduced his theory in 1904 and elaborated upon it (with references to Crocker Land) in 1911.

From the November 2, 1914 issue of the Star Tribune, a newspaper published in Minneapolis. The phrase “physical conditions and theory” almost certainly nods to Rollin Harris’s influential theory — based on currents, old ice, and tides — that a significant landmass exists in the Arctic. Harris introduced his theory in 1904 and elaborated upon it (with references to Crocker Land) in 1911.Clearly, by late 1914, Peary was willing to concede that he had experienced a mirage. He readily admits that he’d be in good company if that were the case. Here was a handy escape route from his failed ploy to secure funding, if that’s all Crocker Land was.

Peary Resumes the More Dangerous RouteTwo years later, MacMillan was still up north. So was Vilhjalmur Stefannson, leading a different expedition to map-check and discover new land along the northern Canadian coast. Unconvinced by MacMillan’s findings, Stefansson informed Peary that he would include a search for Crocker Land. (I discuss Stefansson and the Canadian Arctic Expedition with greater depth on the To Plant a Flag on Crocker Land page.) Meanwhile, Green — who had shared MacMillan’s trek to, mirages of, and final decision about Crocker Land — was returning home and had made it as far as Copenhagen. He brought with him no retraction of that earlier report and no subsequent evidence supporting Peary’s sighting.

Peary issued a public response to Green’s returning with the mirage theory still in place. This was not merely some off-the-cuff remark. No, he had telegrammed the statement to the New York Tribune, and it was then picked up by newspapers from Georgia to Utah. The telegram said that the renown explorer was holding onto his original belief that Crocker Land would be verified as real! After admitting that the Arctic Sea plays tricks on a man’s eyes and that he might’ve miscalculated the distance to Crocker Land, Peary next adds an important statement:

It will be well to await the completion of Stefansson's discoveries before dismissing Crocker Land.It’s just one sentence, but it nags at me. If Peary knew that Crocker Land wasn’t there and that he wouldn’t be getting funding from George Crocker — and that he must eventually be shown to have been wrong — then what was his motive for clinging to the possibility that Stefannson might still find something? Why put off the inevitable? Why issue any statement at all? Instead of asking “Did Peary lie?” the question becomes “Why would Peary stick to his lie when he could have easily covered it up?” Was his ego so great that, to uphold his image as Mighty Discoverer, he stood by as two expeditions risked the multitude of dangers involved in Arctic discovery? It’s not impossible . . . I guess . . . but yeesch!

An Alternate HistoryUnfortunately, it’s probably impossible to determine why Peary went public with his hope that Crocker Land might yet be discovered. I don’t know any reliable psychic who can contact the explorer’s spirit at a séance. Instead, I’ll lean on my skills as a fiction writer. Given those very troubling points raised by Welky — Peary’s expertise in the Arctic along with his failure to mention of Crocker Land prior to the final release of Nearest the Pole — what seems reasonable?

Imagine that, rather than a man’s cold calculation for additional financing, this tale is about a man haunted by an Arctic apparition. Looking at what Peary claims to have seen in Nearest the Pole, we find first “the faint white summits of a distant land” and then “snow-clad summits of the distant land in the northwest” (pp. 202, 207). This is not at all the “great unexplored continent in the polar regions” described in that article from The Sun. Nor is it the vast landmass that Rollin Harris had previously predicted based on currents, ice, and tides — presumably the “physical conditions and theory” Peary alludes to in the Star Tribune article. Just some summits. With this in mind, let’s suppose Peary was smart enough to know that those summits might’ve been a mirage, as he implies in the Star Tribune. Imagine that, as he stood at Cape Colgate, he recalled that the crew of the H.M.S. Herald had seen Plover Land, which was afterward proven to not exist. Later, as he looked out from Cape Thomas Hubbard, picture him remembering that the Polaris expedition led to President Land being put on the map — and then its existence being disproven five years later. What if self-doubt explains Peary’s long hesitancy in recording or telling anyone what he saw?

Then imagine, at the last minute, Peary had a Huckleberry Finn moment. Huck, you’ll recall, runs away from home and shares a raft with Jim, an escaped slave. The boy has been carefully taught that, according to the moral dictates of his pre-Civil War society, he should turn in Jim — for the sake of his own soul! — and he eventually reaches the raggedy edge of doing exactly that. Huck goes so far as to write a letter to Jim’s legal owner, telling her where to find the slave. Mark Twain has his young hero say that he

laid the paper down and set there thinking—thinking how good it was all this happened so, and how near I come to being lost and going to hell. And went on thinking. And got to thinking over our trip down the river; and I see Jim before me all the time: in the day and in the night-time, sometimes moonlight, sometimes storms, and we a-floating along, talking and singing and laughing. But somehow I couldn’t seem to strike no places to harden me against him, but only the other kind.Huck thinks about how kind and caring Jim has been to him. And about how grateful Jim is when Huck returns his friendship. After a moment more, Huck makes one of the best decisions in all of American literature: “All right, then, I’ll go to hell,” he says — and then he tears up the letter.

Now, I’m not comparing Robert Peary to Huckleberry Finn exactly. After all, I like Huck. Peary’s assault on Cook’s claim to be the first to the Pole reveals a prideful and vindictive man (and I understand there are several other reasons to dislike Peary). I’m just wondering if the older adventurer had an epiphany like Twain’s younger one did. Suppose Peary decided that it was for the greater good if he went ahead with his last chance to report what he had seen because he couldn’t stop thinking: What if it hadn’t been a mirage? What if it was something other than a product of cold haze and refracted light? What if it was a permanent place yet to be visited?

Feeble though it may be, this tale provides an explanation of why Peary didn’t mention Crocker Land until the last minute and why he didn’t stick firmly to the escape route offered by MacMillan. I present it as only an alternate history.

I present it as something to keep us thinking.

To Plant a Flag on Crocker Land: The Quest for Verification

An important — and maybe the most anxious — stage of the scientific method occurs when someone’s reported discovery is subjected to independent verification. Arctic exploration goes through the same process. After Peary had announced his sighting of Crocker Land, confirmation by a second party was imminent. This page examines expeditions led by other explorers to locate and, if possible, to plant a flag on Crocker Land. Eventually, these efforts led to the conclusion that Peary’s “hypothesis” was a false one.

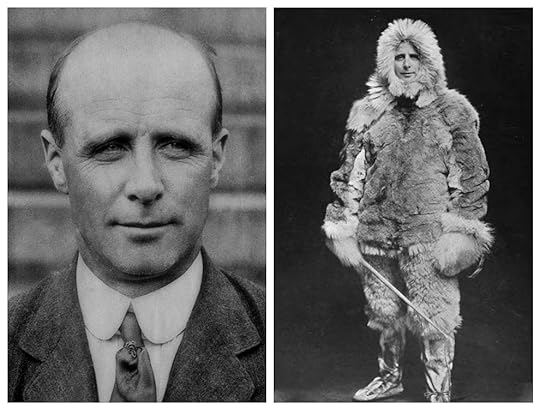

Donald MacMillan and the Crocker Land ExpeditionThere’s little doubt that the expedition most devoted to finding Crocker Land was led by Donald MacMillan. In fact, in a 1913 promotional brochure, his journey is officially called the “Crocker Land Expedition to the North Polar Regions.” The same source also points out that, while the first object was “To reach, map the coast line and explore Crocker Land,” other goals were to seek additional land, to learn about the meteorology and glaciology of Greenland’s ice cap, and to study a wide variety of other things — from seismology to botany — along the way.

Donald Baxter MacMillan (1874-1970)

Donald Baxter MacMillan (1874-1970)Needless to say, Peary saw MacMillan’s expedition as being of the utmost value. In an article for a 1912 issue of The American Museum Journal, he says:

The exploration of Crocker Land easily takes first rank among problems demanding exploration, now that the Poles have been reached and that the insularity of Greenland has been determined. . . . And further than this, should this land, the distant mountain peaks of which I was fortunate enough to see from the summit of Cape Thomas Hubbard in July, 1906, prove to be a land of large extent, the possibilities will be most alluring, for such land will become the gateway to other lands or seas represented by the large blank space on the maps between the North Pole and Bering Strait.The expedition was originally planned to depart in 1912, but this was postponed due to the drowning of MacMillan’s co-planner, George Borup. In July of the following year, MacMillan and his crew finally embarked upon their journey. (According to this article, both the MacMillan and Stefansson expeditions, the latter discussed below, were riddled by calamities.)

On July 2, 1913, MacMillan and his crew departed from the Brooklyn Naval Yard onboard the Diana. This ship ran into rocks near Labrador, though, one in a series of setbacks.

On July 2, 1913, MacMillan and his crew departed from the Brooklyn Naval Yard onboard the Diana. This ship ran into rocks near Labrador, though, one in a series of setbacks.Interestingly, both MacMillan and Borup had been with Peary on the latter’s 1908 expedition, the trip from which Peary returned saying he had reached the North Pole. Both men were located elsewhere, though, when Peary allegedly attained his goal, and that claim came under close scrutiny. Peary’s historic moment became especially debated when Frederick Scott returned about the same time with the news that he himself had been the first man there. As Thomas F. Hall writes in his 1917 book, Has the North Pole Been Discovered?, “neither Peary nor Cook has anything to submit as proof of being the discoverer of the North Pole except a candid narrative.” Since MacMillan’s expedition was spearheaded by Peary’s allies, one might sense that one of its unwritten goals was to bolster Peary’s reliability about his Pole claim by confirming his Crocker Land claim.

And loyalty might partly explain why MacMillan — after finding only icy sea where Peary said Crocker Land should be — went to some length to assure the public that it had been a mirage. In fact, it was so persistent a mirage that he and his colleague had both seen it, too. They even saw it twice from two different locations! In his book recounting the experience, MacMillan explains:

April 21st was a beautiful day; all mist was gone and the clear blue of the sky extended down to the very horizon. [MacMillan's companion, Fitzhugh] Green was no sooner out of the igloo than he came running back, calling in through the door, 'We have it!' Following Green, we ran to the top of the highest mound. There could be no doubt about it. Great heavens! what a land! Hills, valleys, snow-capped peaks extending through at least one hundred and twenty degrees of the horizon. I turned to [Piugaattoq, the expedition's Inuit guide] anxiously and asked him toward which point we had better lay our course. After critically examining the supposed landfall for a few minutes, he astounded me by replying that he thought it was poo-jok (mist). . . . As we proceeded the landscape gradually changed its appearance and varied in extent with the swinging around of the sun; finally at night it disappeared altogether. As we drank our hot tea and gnawed the pemmican, we did a good deal of thinking. Could Peary with all his experience have been mistaken? Was this mirage which had deceived us the very thing which had deceived him eight years before? If he did see Crocker Land, then it was considerably more than 120 miles away, for we were now at least 100 miles from shore, with nothing in sight.The next day, the team surpassed Peary’s estimate of Crocker Land’s shore by thirty miles. With the air being “clear as crystal,” MacMillan found nothing but disappointment. He writes: “You can imagine how earnestly we scanned every foot of that horizon — not a thing in sight, not even our almost constant traveling companion, the mirage.” The team turned back and managed to find the very spot where Peary had stood and seen land in 1906. According to MacMillan:

The day was exceptionally clear, not a cloud or trace of mist; if land could be seen, now was our time. Yes, there it was! It could even be seen without a glass, extending from southwest true to north-northeast. Our powerful glasses, however, brought out more clearly the dark background in contrast with the white, the whole resembling hills, valleys, and snow-capped peaks to such a degree that, had we not been out on the frozen sea for 150 miles, we would have staked our lives upon its reality. Our judgment then, as now, is that this was a mirage or loom of the sea ice.Thus, from vantage points both near and far, the MacMillan deemed Crocker Land to be a mirage. This news was first delivered to the American Museum of Natural History in November of 1914, and Green reiterated it upon his return to New York in September, 1916. Peary, it seems, was the victim of an Arctic visual phenomenon that only the most expert eyes can recognize as merely poo-jok.

Vilhjalmur Stefansson and the Canadian Arctic ExpeditionWhen MacMillan’s expedition for the U.S. embarked, Vilhjalmur Stefansson was already heading north on behalf of Canada. Rather than verifying Crocker Land, though, this expedition was intent upon discovering new land and assessing the accuracy of old maps. Regarding the latter, Stefansson’s crew were unable to find Keenan Land, despite having a telescope and being 25 miles away from the position shown on a National Geographic map.

Vilhjalmur Stefansson (1879-1962)

Vilhjalmur Stefansson (1879-1962)About the time Green returned from the Crocker Land expedition and confirmed the mirage he had experienced with MacMillan (see above), Peary was reported to be holding onto some hope for what Stefansson might find:

It may be that MacMillan and I were both misled by the nearly permanent clouds of condensation over persistent lanes of water. Or unusual refraction which occurs in the Arctic regions may have lifted into view land that was well below the horizon and my estimate of the distance of Crocker may have been too moderate. It will be well to await the completion of Stefansson's discoveries before dismissing Crocker Land.Indeed, Stefansson had dismissed the mirage theory because he knew firsthand how elusive Arctic land can be, and he wrote to Peary to say as much. According the New-York Tribune, Stefansson’s letter dated October 7, 1916, informs Peary of his plan to head “far enough north to have a look for your Crocker Land. From the account of MacMillan’s trip, I don’t see that he has shown its absence.”

On June 17, 1913, Stefansson and crew departed from Esquimalt, British Columbia, aboard the Karluk, the expedition’s flagship. Tragically, the craft became trapped and afterward crushed by ice. It sunk, and the crew’s pursuit of land led to the loss of eleven lives. (Steffanson had earlier disembarked to hunt caribou or to otherwise secure food.)

On June 17, 1913, Stefansson and crew departed from Esquimalt, British Columbia, aboard the Karluk, the expedition’s flagship. Tragically, the craft became trapped and afterward crushed by ice. It sunk, and the crew’s pursuit of land led to the loss of eleven lives. (Steffanson had earlier disembarked to hunt caribou or to otherwise secure food.)Stefansson’s chronicle of his expedition is The Friendly Arctic: The Story of Five Years in the Polar Regions. Unfortunately, there’s not much there on his search for Crocker Land. At one point, the expedition had reached Meighen Island, which was within visual range of where Peary had spotted Crocker Land. This was the farthest north that Stefansson’s men were going, and a 24-hour watch — in clear weather from a 200-foot elevation — was arranged to scan for what Peary had seen. “There were appearances on the horizon which might have been taken for land had one known it to exist,” says Stefansson, “but there was nothing that might not equally well have been fog clouds from open water.” The explorer leaves the island and his readers with this uncertainty.

Afterward, Stefansson discusses getting “remarkably interesting” results from soundings taken beneath the ice off the coast of Melville Island. These measurements led the explorer to conclude that he was passing over a sea bottom

similar to that of an enclosed sea, as we knew from theory and found later when we ran a line of soundings across Melville Sound between Melville and Victoria Islands. This fell in with the theories of Greely, Harris and others that there ought to be land to the northwest, and with Peary's report of having seen 'Crocker Land' in that direction.Stefansson repeats this comment about the sea bottom in a 1921 article for The Geographical Review, which discusses the difficulties of proving or disproving any alleged land in the Arctic. There, he writes:

It seems to me that Crocker Land should still be granted a period of grace. MacMillan marched into the edge of it (as plotted by Peary) and found only sea ice. Had he taken soundings and found abysmal depths, the case against land being there would be impregnable. But he took no critical soundings, and the soundings taken on our journey aimed towards the same general locality in 1917 grew no deeper as we went away from the known lands but continued to be of a 'continental shelf' character for 150 miles as we traveled towards Crocker Land.In other words, his measurements theoretically accommodated the existence Crocker Land, and this was enough for Stefansson to keep an mind open. I’ve found even less in newspapers and popular magazines regarding his conclusions about Peary’s claim. This lack of reporting, in itself, might be revealing: it seems Stefansson simply didn’t have very much to say.

Isaac Schlossbach and the MacGregor Arctic ExpeditionAccording to a brief entry in a 1946 book titled Sailing Directions for Northern Canada, Crocker Land “is now generally believed not to exist.” The MacMillan and Stefansson expeditions are summarized, and then several air trips are noted:

Amundsen, Ellsworth, and Nobile, who flew over the Arctic Ocean in the dirigible Norge in the summer of 1926, saw no sign of the supposed land, but they were perhaps too far west, unless the land were of great extent; visibility was uncertain. Wilkins, who passed eastward of and much nearer the supposed position on his flight from Barrow to Spitsbergen in 1928, states: 'We felt certain then, and believe now, that no mountainous land exists between Grant Land and the North Pole.' Wilkins and Hollick-Kenyon, on a flight in March 1938, had good visibility to the northward of Borden Island, and failed to see Crocker Land. Lieutenant Commander Isaac Schlossback [sic], of the MacGregor Expedition, on May 13, 1938, flew from northwestern Greenland to Axel Heiberg Island and thence northwestward from Cape Stallworthy, but was unable to see any signs of the supposed Crocker Land.Rather than look at each of these individually, I’ll focus on the efforts made by Schlossbach as part of the MacGregor Arctic Expedition. He went flying with Crocker Land specifically in mind, and the results act as a sort of finale to 26 years of failing to find it.

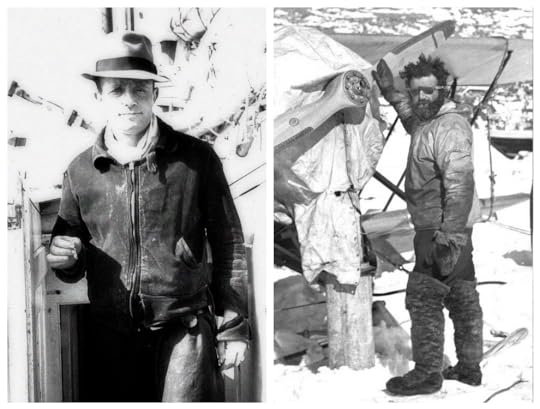

The MacGregor Arctic Expedition, named for and led by Clifford J. MacGregor, was primarily concerned with studying Arctic meteorology and magnetism. However, in a 1937 interview with the Washington D.C. newspaper Evening Star, MacGregor explains that there would also be an aerial “hop” to the North Pole in order to chart “unexplored territory between the top of the world and Greenland and Ellsemere Land [sic] and claim it for the United States. In addition, Mr. MacGregor hopes to clear up the mystery of Crockett Land [sic], sighted by Admiral Peary southwest of the Pole.” He then admits to thinking that “what the admiral saw was probably a mirage.” The same article later names “Lieut. Comdr. I. Schlossbach, U.S.N, retired, who will serve as pilot and navigator and accompany Mr. MacGregor on the flight to the Pole.”

Isaac Schlossbach (1891-1984)

Isaac Schlossbach (1891-1984)The crew returned in October of the following year, and again the Evening Star reported on Schlossbach. “There simply isn’t any Crocker Land,” says the pilot, who had made twenty flights over the spot where Peary reported it. Regarding the lingering mystery, he adds, “I flew over there to clean it up and I think I did.” MacGregor then attributes Peary’s sighting to the conditions that have coaxed many Arctic explorers to see mirages.

Interestingly, the article cited above is titled “Crocker Land Mystery ‘Solved’; A Myth, Says Arctic Explorer,” even though neither Schlossbach nor MacGregor are quoted as using the word “myth.” However, newspaper articles had been referring to the landmass a myth ever since MacMillan’s initial report in late 1914. It’s an interesting word, one with various definitions. It might mean something once believed to be real but now recognized as imaginary, or it can mean something that’s flat-out false. This leads nicely to a new mystery: had Peary been deceived by a mirage — or was he intentionally deceiving the entire world in order to maintain financial support from millionaire George Crocker, the man for whom he named the landmass? Years after Crocker Land had been repeatedly verified as non-existent, the challenge became figuring out the reason behind Peary’s claim to have seen it. Unfortunately, here, the quest for verification requires at least a bit of mind reading.