Tim Prasil's Blog, page 10

July 23, 2023

The Poe Uncertainties: What Caused His Death?

If one could measure the various uncertainties surrounding Edgar Allan Poe, what led to his death might have to be converted into hectares. Maybe miles. Possibly tons. Probably not lightyears, but you see my point. There is a lot of uncertainty regarding Poe’s death.

At the Smithsonian Magazine website, Natasha Geiling approaches this complex controversy by looking at “the top nine theories.” These include beating, cooping, alcohol, carbon monoxide poisoning, heavy metal poisoning, rabies, brain tumor, flu, and murder. If you’re new to the subject, this is a good departure point for your journey into bewilderment.

This is my close-up of Charles Rudy’s 1957 sculpture of Poe awaiting inspiration. The statue can be visited at Richmond’s Virginia State Capitol Square.

This is my close-up of Charles Rudy’s 1957 sculpture of Poe awaiting inspiration. The statue can be visited at Richmond’s Virginia State Capitol Square. What’s that? Nine theories aren’t bewildering enough for you? In that case, Open Culture has a page titled “The Mystery of Edgar Allan Poe’s Death: 19 Theories on What Caused the Poet’s Demise.” There, Josh Jones offers a handy list of 15 theories along with information to dig up the publications in which each was first proposed. He mentions that the list was pulled from the website of The Poe Museum in Richmond, Virginia, but his link is dead. All I can find at that site is a quick mention of “over 26 published theories of [Poe’s] demise” on their page titled “Poe Biography.” Struggling through a jungle of that many theories would require, by my calculations, at least three machetes, seven pith helmets, and a dozen cans of bug spray.

The Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore eases the struggle with a very useful, in-depth review of many of the theories. Wisely, they group things under “The Alcohol Theory,” “Disease and Other Medical Problems,” and “The Cooping Theory.” They also provide full citations for the original sources.

In Geiling’s article mentioned above, Poe expert Chris Semtner is quoted as saying, “I’ve never been completely convinced of any one theory, and I believe Poe’s cause of death resulted from a combination of factors.” I find great relief in adopting this stance. The debate over Poe’s birthplace is pretty much settled: Boston, not Baltimore. His role in establishing detective fiction is less certain, though I feel confident in saying that, while Poe had a crucial role in refining and directing the mystery genre, it’s misleading to suggest he alone invented it. The cause of his death, however, is a question I refuse to answer, even tentatively. In fact — as with ghosts, Bigfoot, Jack the Ripper, and how “literally” came to mean “not at all literally” — I quite prefer the enduring mystery to any solution.

That said, I’ve begun a piece of fiction that posits an imaginary explanation of what happened. It features Harry Escott, Vera Van Slyke’s mentor in occult detection. Hoping to add a dash of realism, I’ve started a page that puts into chronological order some of what we know about the end of Poe’s life. I call it “The Facts in the Case of Poe’s Demise.” It’s very much a work in progress, and any helpful comments would be appreciated.

Go to THE POE UNCERTAINTIES: HIS BIRTHPLACEGo to THE POE UNCERTAINIES: HIS PLACE IN THE HISTORY OF DETECTIVE FICTION

July 19, 2023

The Kinder Side of Baba Yaga(s)

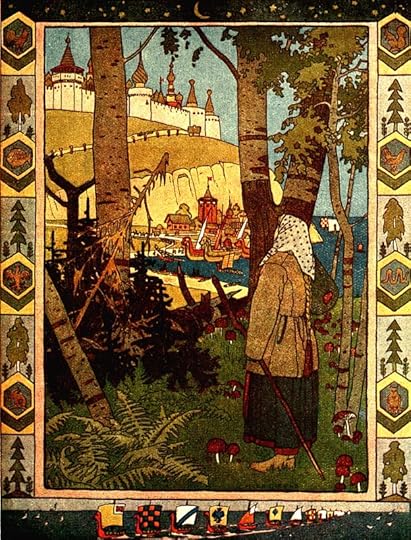

While many readers of English might have been introduced to Baba Yaga by George Borrow in 1862, W.R.S. Ralston’s influential Russian Folk-Tales (1873) delves much further into the figure. However, Ralston describes Baba Yaga as “a species of witch” (p. 9), and his sample tales about her — such as “Marya Morevna” or “Vasilissa the Fair” — emphasize her more sinister side.

Perhaps to counterbalance Ralston, Jeremiah Curtin revealed more of Baba Yaga’s kinder side in Myths and Folk-Tales of the Russians, Western Slavs, and Magyars (1890). In some of the tales translated there (probably by Curtin himself, though I don’t have confirmation of this), Baba Yaga has a very minor role. At times, she is a trio of sisters, each referred to as “a Baba Yaga.” Given this, Curtin illustrates the flexibility in this folkloric character more than Ralston. I’ll focus here on the tales from the later work that especially present Baba Yaga acting as a character who helps rather than threatens the protagonists.

“The Feather of Bright Finist the Falcon”Bright Finist, the title character in this tale, has the enviable ability to toggle between human to falcon forms. He falls in love with a maiden, but her two jealous sisters drive the birdman away. The unnamed maiden embarks on a quest to find him, and along the way she is assisted by three sisters: the Baba Yagas. We recognize that this is the same basic character as in the Ralston collection because, in each case, the maiden comes upon a “hut on hen’s legs, and it turns without ceasing.” Inside, she finds a woman with a gigantic nose who’s lying from one corner of the hut to the other. Baba Yaga’s usual flying mortar and pestle is missing, though, and so are the bones and skulls of victims with which she decorates her fence. She’s still a bit creepy, I guess, but she turns out to be very helpful.

One after the other, the Baba Yagas provide the maiden with a meal, a night’s rest, and the knowledge that Bright Finist is to marry another woman. They also give the maiden the implements needed to thwart her competition, which is exactly what happens. In fact, by the end, Bright Finist has married that other woman. Not to worry, though! It is decided that his legally wedded wife is “to hang on a gate,” where the local officials shoot her. Folktale Justice doesn’t shilly-shally!

A version of this story appears in Russian Wonder Tales (1912), translated by Post Wheeler and illustrated by the great Ivan Bilibin. However, Wheeler doesn’t identify Baba Yaga by name.

“Water of Youth, Water of Life, and Water of Death”

“Water of Youth, Water of Life, and Water of Death”This story is a weird one! In a nutshell, the Tsar hears that there’s a beautiful maiden “from whose hands and feet water was flowing, and whoever would drink that water would become thirty years younger.” (Did I mention it’s weird?) Two of the Tsar’s sons fail to find the maiden, scared off by warnings of being dismembered that come first from “a gray old man” and then from Baba Yaga. Beyond the name and the nickname “boneleg,” this Baba Yaga doesn’t appear with any of the usual indicators: no spinning hut on chicken legs, no huge nose, etc. The Tsar’s third son, Ivan, next tries to find the magic maiden, and he also comes upon “Baba Yaga, boneleg.” If this is the same one his brother encountered, we don’t know, but this time, there is mention of “a cabin on hen’s feet.” As were his brothers, Ivan is warned against pursuing his goal. He’s determined, though, and the remainder of the adventure involves his finding ways around the dismemberments foretold by Baba Yaga. She has a very small role, and it’s limited to cautioning the protagonist about dangers ahead. Poor Ivan doesn’t even get a meal or a night’s rest out of the deal. Nonetheless, Baba Yaga is shown to be making a bit of an effort to guide him on for his quest. At least, she gets points for not eating Ivan.

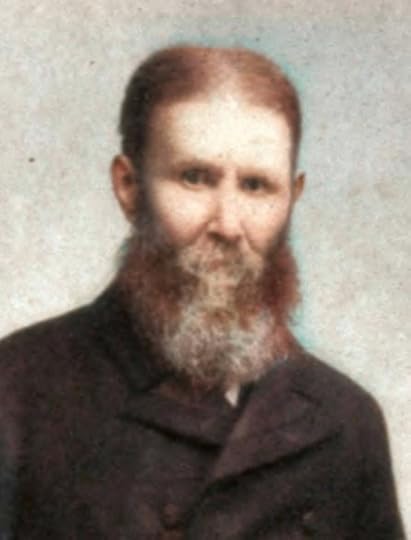

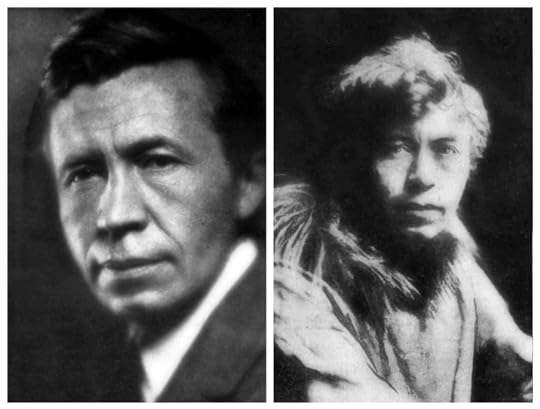

Jeremiah Curtin (1835-1906), taken from his English translation of

The Knights of the Cross,

by Henryk Sienkiewicz, with a dash of color courtesy of Palette“The Enchanted Princess”

Jeremiah Curtin (1835-1906), taken from his English translation of

The Knights of the Cross,

by Henryk Sienkiewicz, with a dash of color courtesy of Palette“The Enchanted Princess”It’s hard to decide if there are two Baba Yagas or only one in the previous tale, but in this one, there are definitely three. There’s no mention of the hut, the nose, the flying mortar and pestle, the skull-lined fence — all the props and set pieces that, in my mind, help to make Baba Yaga a consistent character. Of course, folklore doesn’t really lend itself to such continuity. It’s not Star Trek. I guess the debates over “keeping with canon” don’t make much sense here.

Another romance. A soldier meets a talking bear, who explains she’s really an enchanted princess. He breaks the spell, they fall in love, and the soldier then falls prey to the same “unclean” group who cursed the princess. (I don’t know what’s implied by “unclean,” but it makes me uncomfortable.) One thing leads to another, and the soldier becomes “caught up by a boisterous whirlwind and borne away from her eyes.” Another quest. The soldier hopes to make his way home and, on the way, meets the first Baba Yaga, who is described as “bone-leg, old and toothless.” She guides him to her sister — and then the second Baba Yaga guides him to a third. This third Baba Yaga does more than help. She saves the day by commanding the winds to locate the princess and carry the soldier back to her.

As I say, none of the usual indicators of Baba Yaga are in this tale, but Baba Yaga does have the power to control natural elements. In one of the best known of her tales, which Ralston titles “Vasilissa the Fair,” Baba Yaga reveals that the Day, the Sun, and the Night “are all trusted servants of mine.” There, though, she just seems to be showing off. In “The Enchanted Princess,” she uses this power for the good of the protagonist.

The more I explore Baba Yaga, the more I become enchanted by her ability to take many forms. Indeed, she’s an enchantress, so I guess this was her plan all along.

By me a ghost! CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THE

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THEWHISPERS OF WITCHERY

MAIN PAGE.

July 16, 2023

Resparking Interest in Charles Fenno Hoffman, a Once-Acclaimed American Author

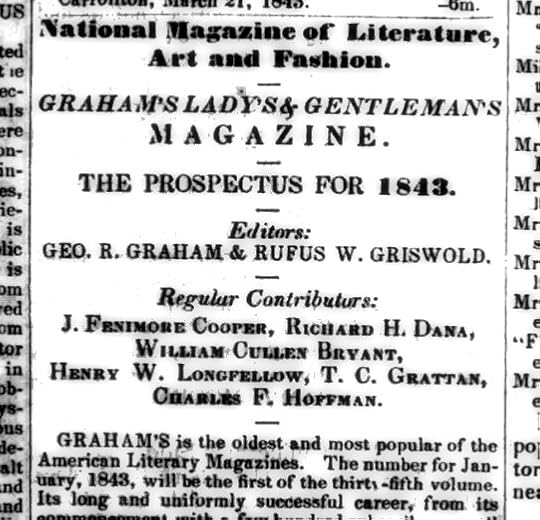

I went digging for some interesting tidbit regarding an American author named Charles Fenno Hoffman (1803-1884). I found one in the November 5, 1842, issue of the Southern Pioneer, a newspaper based in Carrollton, Mississippi. It’s a promotional piece for Graham’s Magazine, and Hoffman’s name is placed among James Fenimore Cooper and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

It’s interesting that another writer, a fellow named Edgar Allan Poe, had published quite a bit in Graham’s by the time this advertisement appeared. Along with literary reviews and some of his most cherished poems, outstanding tales written by Poe — namely, “Murders in the Rue Morgue,” “A Descent into the Maelström,” and “The Mask of the Red Death” — had all been printed in Graham’s. Nonetheless, in late-1842, Poe seems to have lacked what Hoffman had earned: the name recognition that might sell magazines.

I wonder, though, how many readers today know the work of Hoffman. Certainly, there are fewer than those who’ve read Poe. Or Cooper. Or Longfellow.

I’m pleased to announce that Brom Bones Books has now released Tales, Sketches, & Poems of Charles Fenno Hoffman, edited by Kelly Keener. On the one hand, this volume serves as a great introduction for readers unfamiliar with Hoffman. On the other, it’s a handy collection of otherwise tough-to-find works for readers who already enjoy his writing. Learn more about it by clicking on the cover below.

— Tim

July 3, 2023

Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit: A Phantom Locomotive Near Dalton, Georgia

A Historic and Haunted Line

A Historic and Haunted LineFounded in 1836, the Western & Atlantic Railroad continues to connect Atlanta, Georgia, to Chattanooga, Tennessee. In the 1860s, during the Civil War, an effort to sabotage rail passage led to what’s come to be called the Great Locomotive Chase. In the 1870s, a ghost appearing along the line was reported in Georgia newspapers. (A thorough overview of that railroad haunting is here.) But in the 1880s, not far outside Dalton, a phantom locomotive was witnessed charging along the tracks. It’s this apparition that I’ll focus on here.

Let’s begin with this 1881 article from The Marietta Journal:

From the front page of the January 27, 1881, issue of The Marietta Journal.A Subsequent Witness — or Old News?

From the front page of the January 27, 1881, issue of The Marietta Journal.A Subsequent Witness — or Old News?There’s not much to go on here. For instance, there was only one witness — that is, unless the phantom train was encountered again in October of 1883. That’s the month the North Georgia Citizen reported that an apparition previously mentioned in another newspaper “has been seen again.” Yet the facts of this “new” sighting suspiciously mirror those related in 1881. In both articles, the witness saw a headlight coming around a curve. He stepped to the side of the tracks, where he became puzzled by the absence of sounds. He then watched the apparition rush by him.

The two articles end a bit differently, though. In 1881, the witness claims to have seen two spectral trainmen. In 1883, the train is described as having been semi-transparent: “objects on the opposite side of the railroad were distinctly visible.” Still, I can’t help but wonder if somehow the Marietta Journal and the Citizen are describing the same encounter.

From the

Report of the Superintendent and Treasurer of the Western & Atlantic Rail-Road

(1852)Locating the Encounter Now

From the

Report of the Superintendent and Treasurer of the Western & Atlantic Rail-Road

(1852)Locating the Encounter NowOnly the earlier report gives a hint of where the sighting might’ve happened. It says: “about two miles from town.” While this seems pretty vague at first, it actually narrows things down considerably. The article first appeared in a Dalton newspaper called the North Georgia Citizen, so presumably “town” is Dalton itself. (I haven’t been able to find that original article, but — as does the Marietta Journal above — the Savannah Morning News credits the Citizen.) Now, according to The Official Railway Guide for 1881, the Western & Atlantic stops before and after Dalton were Tunnel Hill to the north and Tilton Road to the south. These days, I-75 runs parallel to and east of the tracks. A ghost hunter can use these locations to chart an expedition along both stretches of track, two miles top and two miles bottom, so to speak. Needless to say, be extremely careful when investigating railroads. Keep your eyes up rather than on your equipment. After all, physical trains far outnumber phantom ones.

If no semi-transparent locomotive with a panicked engineer and fireman onboard speeds silently by, Dalton is still a great destination for railroad and history lovers. First, there’s a restored depot that now serves as a Visitor’s Center. Second, up the line a way, there’s the Tunnel Hill Heritage Center & Museum. According to their website, visitors can enjoy “a number of railroad and Civil War artifacts that tell the story of Tunnel Hill from the days before the city was chartered to the renovation and reopening of the historic Western & Atlantic Railroad tunnel in 2000.” And I bet that tunnel has a few tales to tell.

As always, regardless of the results, please let us know in the comments below if you do any ghost hunting in Dalton.

Discover more “Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit” at the page forAfter the End of the Line: Railroad Hauntings in Literature and Lore

Buy me a ghost!

Buy me a ghost!

July 2, 2023

How Narrowboats Floated Me Toward Asking Folks to Buy Me a Ghost

Every now and again, I’m inspired to redesign BromBonesBooks.com to make it easier to navigate. This week, I simplified the main menu with blunt headings: BOOKS, RESEARCH, FUN, BLOG, and ABOUT. I took features previously found under “For Fun and Edification” and split them into RESEARCH and FUN. As a result, projects such as Whispers of Witchery and the Ghost Hunter Hall of Fame are now found under RESEARCH while Tales Told When the Windows Rattle and Old Phantoms with New Captions are linked under FUN. (Doing this revealed that I really ought to be having more fun!)

Please let me know if this is helpful or if there are other ways that I might make improvements.

The Progress, a working narrowboat on the River Severn, taken from a 1909 issue of

The Motor Boat

(and colorized at Palette.fm)

The Progress, a working narrowboat on the River Severn, taken from a 1909 issue of

The Motor Boat

(and colorized at Palette.fm)Speaking of navigation, I’m a fan of YouTube channels about narrowboating. You see, Britain has an impressive canal system, one originally built to transport goods. The earliest boats were basically barges, which were towed by horses led along the shore. Unfortunately, those confounded steam trains appeared shortly afterward, providing more efficient distribution. The canals drifted into disrepair.

Fret not! Decades later, the canal system was “rediscovered” as a watery playground for pleasure boaters, and it ignited new interest in these charming boats — now powered by solar and diesel rather than by oats and hay. Some people live on theirs fulltime, such as the boater who steers my current favorite YouTube show: The Narrowboat Pirate.

This is the long story behind another something new you’ll find here at BBB.com. That pirate roaming the canals of Britain and the channels of YouTube benefits from small donations handled by a site called Buy Me a Coffee. She changed things, though, so that folks can Buy Her a Rum. It occurred to me that someone might think the RESEARCH and the FUN on my site are worth a few bucks, and so I signed up, too. You can now Buy Me a Ghost! Throughout my site, at the bottom of pages and posts, I’m discreetly tucking buttons like the one below. Click on any of them to find out how it works.

Buy Me a Ghost!Please give it a glance. Who knows? Maybe one day I’ll be able to afford a phantom narrowboat!

— Tim

June 25, 2023

The Hannah Cranna Legend: A Transcription from 1900 Versus the Internet Version

Do an Internet search for “Hannah Cranna,” the main figure in a witch legend rooted in the Stepney district of Monroe, Connecticut. You’ll probably find out that:

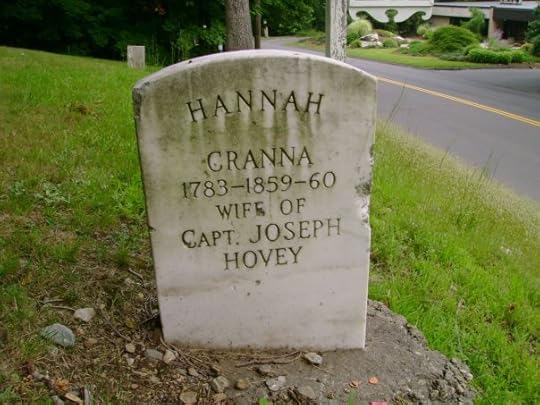

Hannah was a real person, who was born in 1783 and who died in the winter of 1859/60.She was married to Captain Joseph Hovey, who died under mysterious circumstances.Those years and the marriage are confirmed by Hannah’s headstone (shown below) in the Gregory’s Four Corners Burial Ground.Interestingly, these points disagree with the earliest transcription of the legend I’ve been able to find. It’s a three-part, anonymous article published in The Newtown Bee on the 7th, 14th, and 21st of December, 1900. On the 28th, The Bee published a sort of letter-to-the-editor from a reader who adds more to the article’s many tales told about Hannah’s witchy exploits.

If only to stir a cauldron of confusion, I’ll take a look at the discrepancies between what I’ve read on the Internet and what’s in this 1900 transcription. I won’t attempt to suggest that one version of the legend is right or “righter” while the other is wrong or “wronger.” Legends simply don’t work that way. But maybe this will provide an insight into how these (more than) twice-told tales evolve over time, and how the Internet has given us something new to consider when it comes to telling folktales.

Why Was Hannah Called “Cranna” and When Did She Live?All by itself, that headstone is a bit of a head-scratcher. Is “Cranna” Hannah’s maiden name? At first glance, this seems reasonable. , after all, one probably derived from a Scottish term for a rocky or lofty place. In the first installment of The Bee article, though, the writer establishes that “Cranna” is Hannah’s married name, since her husband is identified as Silas Cranna. So what do we do with the headstone saying “wife of Captain Joseph Covey”? Well, according to the Damned Connecticut website, the woman buried there “apparently picked up the nickname Hannah Cranna while she was still alive.” The New England Ghoul adds that it was meant to insinuate that Hannah might have pushed her husband off a cliff, i.e., a rocky and lofty place. Interesting! Does dubbing Hannah this name suggest Monroe had a significant Scottish population? More importantly, would such a nasty nickname be carved into a headstone? Wouldn’t there be, say, quotation marks around it or something else to imply this was what Hannah was called informally, if not behind her back? That headstone raises more questions than it offers answers.

Let’s move on. There’s also a discrepancy in when Hannah lived. After an introduction, The Bee writer sets the stage for the legend proper:

Many years ago, so many that only one or two of the oldest inhabitants ever saw her, in the house on the hill lived Hannah Cranna. . . .If Hannah died 40 years before the article was printed, as that headstone indicates, there probably would be more than “one or two” locals old enough to have seen her. While life expectancy was indeed shorter in the 1800s, that’s an average age of dying, one lowered by the many things that spelled death, especially infant mortality. If one managed to avoid those many deadly things, people lived about as long as they often do now, and it was far from unheard of for some folks in the 1800s to live into their 70s, their 80s, even their 90s. The woman whose headstone is shown above, for example, lived to about 76. More than a century before that, Ben Franklin’s parents survived well into their 80s. Human DNA hasn’t changed that much in a few centuries, after all. It’s just that we’re generally lots better at making it to “old age,” raising the average life expectancy. With this in mind, The Bee’s Hannah seems to be a generation or two older than that the Internet’s Hannah.

The Death of Hannah’s HusbandThe website for the New England Historical Society also works on the premise that Hannah in the legend was the wife of Joseph Hovey and follows the dates on the headstone. It explains Hovey’s death this way: “No whisperings of witchcraft followed [Hannah] until her husband died suspiciously…. The townspeople of Monroe thought Hannah had cast a spell that confused Joseph Hovey enough to wander into an abyss. From then on she carried the nickname Hannah Cranna.”

The Bee writer, on the other hand, gives a less ambiguous story. It starts this way:

Silas Cranna was an inveterate tippler [meaning an alcoholic] and passed much of his time [drinking] at an inn that stood at the present site of Porter's blacksmith shop, near Stepney Depot.Please permit me a quick digression. In 1900, there was a blacksmith named Porter who worked near the Stepney train depot. The notice below shows he wanted whoever pilfered his saw to return it, if you please!

From the December 1, 1899, issue of The Newtown Bee.

From the December 1, 1899, issue of The Newtown Bee.Now, this doesn’t prove that an inn was there previously or that someone named Silas Cranna frequented it. Mentioning the blacksmith might be nothing more than a way to add a dash of recognizable reality to an otherwise fabricated story (and it’s followed by references to other residents alive in 1900). Now, let’s get back to that story:

[Silas Cranna's] mode of life, to say the least, annoyed Hannah, and she ushered in her initiation to witchcraft by murdering him.... [Witnesses near a local cliff watched as] she seized him and dragged him toward the edge of the precipice. He struggled desperately but his virility being undoubtedly much weakened by his bucolic habits, he was no match for his enraged wife. She forced him, writhing and screaming for help, to the edge and deliberately thrust him over.... Silas Cranna never stirred again. He was dead.Unlike the Internet version, the mystery surrounding what became of Hannah’s husband is set straight in The Bee version: Hannah committed mariticide up on Helvelyn crag.

There’s another problem, however. I can’t find verification a “Helvelyn crag” anywhere near Monroe. Was The Bee writer, in this case, changing the name to protect the innocent? Maybe “Helvelyn crag” was a pseudonym for what the CT Insider identifies as the spot where the Hoveys allegedly lived: “Cragley Hill, close to present-day Cutler’s Farm Road.” Much more likely, it’s an alternate spelling of “Haviland Hill,” which Monroe historian Edward Nichols Coffey says was the traditional name for Bug Hill Road.

The Many Agreements Between The Bee and the InternetCoffey’s out-of-print book, A Glimpse of Old Monroe, includes a discussion of the Hannah Cranna legend. It was published in 1974, and so it acts as a nice “halfway point” between The Bee and the Internet versions. (Please tell me if you know where I can find a copy that isn’t too expensive.) Scroll down to the Hannah Cranna section in this online article from The Monroe Sun, and you’ll see it leans heavily on Coffey’s version. Given what’s there about “Cranna” being a nickname and “Hovey” being Hannah’s real one, I suspect a lot of the Internet accounts can be traced back to Coffey’s book.

But a lot of the Internet lore fits nicely with The Bee article, too, meaning some of what’s being said now has been said for well over a century. For instance, there’s an anecdote about Hannah striking back at a couple of farmers who pooh-poohed the authenticity of her conjuring powers. She cast a spell that halted their oxen from carrying a cartload of hay. The Bee article identifies the farmers as Theodore Beach and Isaac Nichols. A site called Paranormal Catalog leaves them nameless, but it’s the same illustration of Hannah’s tit-for-tat approach to witchcraft.

In addition, Hannah’s beloved rooster, Old Boreas, has been part of the legend all along. The bird crowed reliably every midnight instead of every morning, and when he died, Hannah gave him a starlight burial “exactly in the center of her garden,” according to The Bee article — and “in the exact center of her garden,” according to Cemetery Insights and Beyond. In other words, some of the legend continues to be told very much as it was in 1900. And Old Boreas’s star still shines!

From Lewis Wright’s

The Book of Poultry

(1885)

From Lewis Wright’s

The Book of Poultry

(1885)The account of how Hannah meddled with her own funeral has persisted across the decades, too. She left instructions that her coffin should be transported all the way to the cemetery by pallbearers, not by a cart or some other vehicle pulled by horse or oxen. The Bee writer describes Hannah threatening the villagers:

"Obey my wishes strictly if you would avoid trouble and vexation of spirit, for remember, even after I am no more there will be that which I shall leave behind that will see that my wishes in this matter are respected and fulfilled."It being the dead of winter, though, the villagers disobeyed. They tried to drag the coffin on a sled behind some oxen, but it slipped off time and again, and even chains wouldn’t hold the bewitched box in place. At times, the coffin seemed to move of its own volition!

It was, therefore, eventually decided to return with the body to the house and to start again from thence at an hour before sunset, carrying the remains of the witch as she had dictated, thus fulfilling in every detail her last instructions....This parable in respecting final wishes — along with several other yarns about Hannah found in The Bee transcription — persist as standard elements of the Internet renditions of the legend. And that’s pretty cool.

Where Does This Leave Us?Much as Hannah Cranna’s coffin shifted and slipped from that sled, folklore is unsteady. It wiggles and wobbles over time. Readers interested in spooky legends about witches, ghosts, lake monsters, or what have you should keep in mind that what they find on the Internet is often just one version of the story — almost certainly not the only one. At the same time, the Internet has made it easy to see what was being said long before the Internet! Dig deep. Gage how long a particular legend has been around. Spot the discrepancies. Appreciate the consistencies.

Only then can one enjoy the ways that legends evolve and, by evolving, endure.

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THE

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THEWHISPERS OF WITCHERY

MAIN PAGE. Buy me a ghost!

June 11, 2023

Cornwall’s Old Moll: A Witch Who Only Wants to be Remembered?

The grassy grounds surrounding Carn Kenidjack, in Cornwall, is a fabled and forbidding landscape. Allegedly, strange sounds rise from the rock formation at night, accounting for its original name Cairn Kenidzhek, which means “hooting cairn.” In 1887, Margaret Ann Courtney described the place this way:

It enjoys a very bad reputation as the haunt of witches. Close under it lies a barren stretch of moorland, the "Gump," over it the devil hunts at night poor lost souls.... It is often the scene of demon fights, when one holds the lanthorn to give the others light, and is also a great resort of the pixies. Woe to the unhappy person who may be there after nightfall: they will lead him round and round, and he may be hours before he manages to get out of the place away from his tormentors. Here more than once some fortunate persons have seen 'the small people' too, at their revels.... From John Thomas Blight’s

A Week at Land’s End

(1861). This 2019 video taken by Lucas Nott suggests things have remained pretty much the same.What about Witches?

From John Thomas Blight’s

A Week at Land’s End

(1861). This 2019 video taken by Lucas Nott suggests things have remained pretty much the same.What about Witches?Beyond saying witches lurk near Carn Kenidjack, Courtney does not provide any specifics. Sixty-six years before her, John Thomas Blight tried to convey the mood of the area by saying that “Macbeth’s witches might have danced on such a spot.” But that’s as witchy as he gets.

For an individualized tale of a witch there, we turn to Robert Hunt’s Popular Romances of the West of England (1865). It’s short enough for me to quote in full:

On the tract called the "Gump," near Kenidzhek, is a beautiful well of clear water, not far from which was a miner's cot, in which dwelt two miners with their sister. They told her never to go to the well after daylight; they would fetch the water for her. However, on one Saturday night she had forgotten to get in a supply for the morrow, so she went off to the well. Passing by a gap in a broken down hedge (called a gurgo) near the well, she saw an old woman sitting down, wrapped in a red shawl; she asked her what she did there at that time of night, but received no reply; she thought this rather strange, but plunged her pitcher in the well; when she drew it up, though a perfectly sound vessel, it contained no water; she tried again and again, and, though she saw the water rushing in at the mouth of the pitcher, it was sure to be empty when lifted out. She then became rather frightened; spoke again to the old woman, but receiving no answer, hastened away, and came in great alarm to her brothers. They told her that it was on account of this old woman they did not wish her to go to the well at night. What she saw was the ghost of old Moll, a witch who had been a great terror to the people in her lifetime, and had laid many fearful spells on them. They said they saw her sitting in the gap by the wall every night when going to bed.Red Shawls and Witches Who LingerTwo elements of this legend grabbed my attention: the red shawl and the fact that the witch is a ghost. Working on one of my other projects a while back, I wrote about a 1905 newspaper article describing Alabama railroad workers being terrified by the ghost of “a frightful looking hag with a large red shawl wrapped around her head.” In that post, I refer to this Cornish legend along with one from Ireland and another from Wales, all of which signal the danger of a witch by putting her in a red shawl. My hunch is that those Alabama workers had inherited this folklore motif from Celtic ancestors. (If the pairing of witches and red shawls is found elsewhere, I’d love to hear about it!)

As I delve further into witch legends, from time to time, I stumble upon tales of a witch whose power transcends death and whose spirit is really the star of the show. The spectral witch in Alabama appears to be limited to materializing and sending train mechanics fleeing in confusion. The Kenidjack witch’s magic seems to have weakened since death, reducing her to pulling pranks at the well. Since Old Moll doesn’t seem able to do much harm now that she’s dead — not like in her glory days — perhaps she simply wants to be remembered. The most impressive ghostly witch I know about is Tennessee’s Bell Witch, a legend born in the early 1800s. From a later perspective, this case smacks of poltergeist activity. The folks involved didn’t have the word “poltergeist” in their vocabulary, though, so they dubbed the spirit a “witch,” one possibly conjured by Kate Batts.

Folktale Fashioned into Fairy TaleMy research led to a story titled “The Magic Pail,” which appears in Enys Tregarthen’s 1905 collection The Piskey-Purse: Legends and Tales of North Cornwall. Aimed at children, the book contains what we can confidently call fairy tales, since Tregarthen points out that they feature “Piskey and other fairy folk” (p. ix). Two pages later, though, she uses the term “folklore tales,” perhaps to inject a told-at-the-fireside-in-olden-days charm to them. At the same time, “The Magic Pail” is 51 pages of detail and dialogue, which implies it’s far removed from quaintly creepy stories heard at Cornish hearths. It might be a very loose adaption of the legend Hunt transcribed. It might simply have been inspired by that legend and others like it. It might be something entirely different.

One of J. Ley Pethybridge’s illustrations for “The Magic Pail,” in Enys Tregarthen’s The Piskey-Purse (1905)

One of J. Ley Pethybridge’s illustrations for “The Magic Pail,” in Enys Tregarthen’s The Piskey-Purse (1905)Nonetheless, Hunt’s and Tregarthen’s two narratives share basic building blocks: Carn Kenidjack is the setting, a miner is an important character, a pail is a key prop, and there’s magic and mystery. Beyond that, the stories are pretty different. Hunt’s doesn’t seem to teach a clear moral for its audience, depending instead on stirring a moment of wonderment. Tregarthen’s is more of a King Midas/Monkey’s Paw/be-careful-what-you-wish-for thing, the pail granting wishes that turn out badly in one way or another. It’s a well-crafted tale, if a bit long, and certainly one that illustrates how Carn Kenidjack radiates a sensation of strangeness — and stories about the same.

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THE

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THEWHISPERS OF WITCHERY

MAIN PAGE.

June 4, 2023

Victorian Advice for a Reluctant Ghost Hunter

In the April 21, 1877, issue of Vanity Fair, the British magazine, readers were prompted to resolve a dilemma faced by a timid ghost hunter. It was that week’s challenge in “Hard Cases,” a regular feature that posed problems in proper behavior — proper, that is, for members of England’s upper-crust. The “cases” ranged from meeting for tea to extramarital relationships, and readers sent in their best advice. Responses “adjudged correct” (presumably by a member of the editorial staff) were printed the following week. That week in April, the topic managed to blend paranormal investigation with courtship:

The next week, the “right” responses are so contradictory that the smitten yet shivering “A” wouldn’t know what to do. Several readers advise him to muster the courage to sleep in the haunted chamber. Others agree, but add that he not do so alone: share the investigation with Miss C and her mother, a friend, “a couple of bottles of port,” or a bribed butler. On the other hand, a few readers tell A to confess his fears. The implication is that he might offer to share a bedroom with someone rather less deceased.

That same week, the editors raised the stakes by tacking on the “Second Incident”:

The replies chosen to appear in the May 5, 1877, issue are just as varying. Be brave! Solve the mystery! Throw something at the ghost! Throw a pillow at it! Throw the butler at it! Strike a match! Touch the ghost! Ring the bell! Yell!

While two or three of the readers treat the case as silly — telling A to hide under the blankets or to “[a]sk the ghost to kiss him” — most of the readers respond with some seriousness. These can be placed on a spectrum between sceptics and believers. Interestingly, several of readers strike a balance and bid A to test the authenticity of his observation. For instance, the reader who suggests ringing the bell — and “violently,” no less — wants A to summon another witness for verification.

The sceptics seem to make up the majority, though. Working on the assumption that ghosts can’t be real, they advise A to debunk the situation. Some recommend he threaten the hoaxer with a pistol. The reader who suggests he throw his pillow at the apparition explains that, if the pillow passes through it, there’s proof that “his imagination is merely distorted by his nervous system having been over-taxed by the narration of the ghostly tale.” If the pillow bounces off the apparition, “it will prove that A is either the victim of a practical joke, or that he has to deal with a somnambulist.” In other words, the vision is either a full-fledged mental delusion or a misinterpretation of something entirely physical, such as a sleepwalker. No ghosts need apply.

Only a few approach the problem on the assumption that the ghost is real. The most sympathetic of these writes: “A should speak to the ghost, and find out why it troubles the house so pertinaciously.” Well, that might be a lot to ask of our trembling suiter, but it reinforces something all ghost hunters should remember: not all specters want to spook us.

Had I’ve known about this curious exchange earlier, I would have considered including it in The Victorian Ghost Hunter’s Casebook. Hmmm. Maybe it doesn’t really fit there. But it does give us a glimpse into how the Victorians understood — and disagreed on — proper procedure for dealing with ghostly phenomena.

–Tim

May 24, 2023

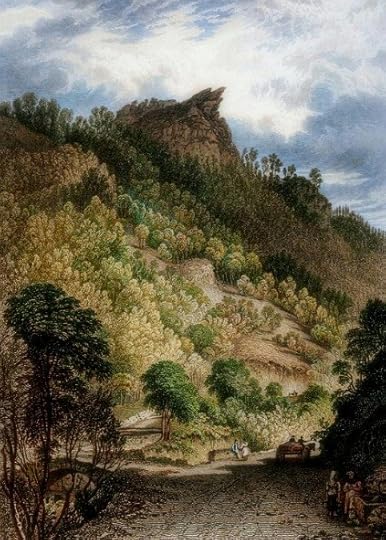

A Tale of Two Witches: The Legend of Lady Sybil and Mother Helston

There’s a legend set near Todmorden, on the border of England’s Lancashire and Yorkshire counties, that’s unique in that it pits — not the usual solitary witch against an entire community — but two witches against each other. In addition, the witchcraft that incites the story’s conflict does no one harm — it simply allows a woman to experience contentment and freedom. Despite these distinctive characteristics, the legend of Lady Sybil and Mother Helston mirrors similar folktales in that the ultimate goal driving the narrative is to halt a witch’s behavior in one way or another.

The oldest written record of this legend I’ve found is in John Roby’s 1829 Traditions of Lancashire, which he introduces as a collection of “interesting legends, anecdotes, and scraps of family history . . . hitherto preserved chiefly in the shape of oral tradition.” Roby explains he was transcribing the folktales he had heard growing up, yet he must have recognized that doing so in 1829 England might raise an elitist eyebrow. Tales told by the common folk? — Heaven forfend! He clarifies that he’s presenting these popular stories “in a form that may be generally acceptable, divested of the dust and dross in which the originals are but too often disfigured, so as to appear worthless and uninviting.” In other words, he was tailoring his material to a readership expecting a good deal of erudition along with any entertainment. He did so by adding the kind of details, dialogue, and digressions one finds in novels and histories, not in the oral narrations he had heard in his youth.

As a result, Roby’s rendition of the legend takes up 26 pages while John Harland, in 1873; T.F. Thiselton-Dyer, in 1895; and Joshua Holden, in 1912, each managed to tell the same tale in under three pages. By the second half of the 1800s, you see, folktales preserved as folktales had become a more welcome kind of reading.

Lady Sybil’s Story Shared SuccinctlyHere’s Holden’s version, the shortest of all four versions:

Long ago a beautiful heiress, called Lady Sybil, lived at Bernshaw Tower. She was exceedingly gifted and took a keen delight in the beauty of Nature. One of her favourite walks was to Eagle Crag, where she would often stand and gaze into the wooded chasm beneath. It was then that Lady Sybil longed for the supernatural power of a witch. At last, unable to resist the temptation of the devil, she bartered her soul in return for this magical gift. With the aid of magic she could change her shape, and it was her delight to roam over her native hills in the form of a beautiful white doe. George Pickering’s depiction of Eagle’s Crag, taken from John Roby’s

Traditions of Lancashire

(1829) and colorized at PaletteOne of Lady Sybil's admirers was Lord William of Hapton Tower, a younger member of the Towneley family. She rejected his suit, and in his despair, he sought the help of Mother Helston, a famous witch. She told him to go hunting in the gorge of Cliviger. He did so and there caught sight of a milk-white doe. After a long pursuit he captured it near Eagle Crag, with the help of Mother Helston who joined the hunt disguised as a hound. Lord William fastened an enchanted silken leash round the doe's neck and led her in triumph to Hapton Tower. In the morning it was Lady Sybil who graced Hapton Tower with her presence. Soon afterwards, when she had renounced witchcraft, she was married to Lord William. But the old longing for magical experiences returned, and again she wandered, as of old, in some secret disguise. Once, when she was frolicking in Cliviger Mill as a beautiful white cat, the miller's man cut off one of her paws. Pale and wounded, for she had lost one of her hands, Lady Sybil returned home. She had to face the anger of Lord William, to whom the missing hand with its costly signet ring had been brought from Cliviger. Magic skill restored the hand, and Lady Sybil was reconciled to her husband. Her strength, however, was gone, and when her soul had been rescued from the powers of darkness, she died in peace. Bernshaw Tower was left tenantless, but for many years on All Hallow's Eve a spectre huntsman with a hound and milk-white doe flitted past Eagle Crag. Shapeshifting and Halloween

George Pickering’s depiction of Eagle’s Crag, taken from John Roby’s

Traditions of Lancashire

(1829) and colorized at PaletteOne of Lady Sybil's admirers was Lord William of Hapton Tower, a younger member of the Towneley family. She rejected his suit, and in his despair, he sought the help of Mother Helston, a famous witch. She told him to go hunting in the gorge of Cliviger. He did so and there caught sight of a milk-white doe. After a long pursuit he captured it near Eagle Crag, with the help of Mother Helston who joined the hunt disguised as a hound. Lord William fastened an enchanted silken leash round the doe's neck and led her in triumph to Hapton Tower. In the morning it was Lady Sybil who graced Hapton Tower with her presence. Soon afterwards, when she had renounced witchcraft, she was married to Lord William. But the old longing for magical experiences returned, and again she wandered, as of old, in some secret disguise. Once, when she was frolicking in Cliviger Mill as a beautiful white cat, the miller's man cut off one of her paws. Pale and wounded, for she had lost one of her hands, Lady Sybil returned home. She had to face the anger of Lord William, to whom the missing hand with its costly signet ring had been brought from Cliviger. Magic skill restored the hand, and Lady Sybil was reconciled to her husband. Her strength, however, was gone, and when her soul had been rescued from the powers of darkness, she died in peace. Bernshaw Tower was left tenantless, but for many years on All Hallow's Eve a spectre huntsman with a hound and milk-white doe flitted past Eagle Crag. Shapeshifting and HalloweenMany of the basic narrative elements in all the four versions mentioned above are consistent. Lady Sybil is always described as exceptional, be she very beautiful, very smart, and/or very gifted. Mentioned in each is her beloved Eagle’s Crag, one of the various landmarks that roots the fantasy in reality. (Eagle’s Crag even has the honor of having a real brewery named for it.) Being rejected by Lady Sybil drives Lord William to consult with Mother Helston, apparently a local freelance witch. With a weirdly swift hound’s help, Lord William then manages to put a leash on Lady Sybil — literally and figuratively. In a nutshell, the legend is very much about a man without (magical) power needing help from a woman with (magical) power to forcibly take a wife with (magical) power. Gender is often a glaring part of this kind of narrative, but is this one a reflection of male anxiety about powerlessness or even womb envy? Lord William’s desire for dominance is hardly subtle here.

Not surprisingly, there are some fairly minor differences, too. For example, Thiselton-Dyer reduces the episode of Lady Sybil’s relapse — the stuff about her losing her cat paw/human hand — to this: “But within a year [of being lassoed by/married to Lord William] she had renewed her diabolical practices, causing a serious breach between her husband and herself. Happily a reconciliation was eventually effected….” Another alteration appears when Holden suggests Helston shapeshifted into the hound that assists Lord William. Harland and Thiselton-Dyer identify the spooky pooch as Helston’s familiar instead of Helston herself. Roby implies a mysterious link between the hound and Helston while avoiding specifics. The point is the same: it takes a witch to catch a witch.

Halloween plays an interesting — and only slightly inconsistent — role in these variations of the legend. Roby puts the hunt on “All-Hallow’s day,” but earlier the Devil tells Lady Sybil that this is “when the witches meet to renew their vows.” Harland and Thiselton-Dyer say it’s on “All-Hallow’s eve,” meaning Halloween. Holden remains silent. All say that Lady Sybil’s paw/hand was cut off a year after her capture/marriage, so maybe Halloween had something to do with her being lured back to shapeshifting. Interestingly, all four transcriptions end by saying that, every Halloween since Lady’s Sybil’s death, the ghostly scene of a doe chased by a hunter and a hound is reenacted in the vicinity of Eagle’s Crag.

“Lady Sybil at Eagle’s Crag,” taken from T.F. Thiselton-Dyer’s Strange Pages from Family Papers (1895) and colorized at PaletteThe Tragedy of a Woman Bound

“Lady Sybil at Eagle’s Crag,” taken from T.F. Thiselton-Dyer’s Strange Pages from Family Papers (1895) and colorized at PaletteThe Tragedy of a Woman BoundSome folktales elicit sympathy for a witch character. A good example of this is the Peg Wesson legend. This one follows that pattern, too, presenting Lady Sybil as victimized the other three characters. As noted above, her witchcraft does no harm: she merely communes with nature by assuming a form no more ferocious than a weredeer (should that be “weredoe”?) and a werecat. Yes, her making a pact with the Devil is a problematic part of this, but it’s still pretty easy to feel for her, given that her wish to roam incognito is thwarted by a man who binds her with what our storytellers call either a “noose” or a “leash.”

In contrast, Mother Helton sells out her supernatural sister. This backstabbing witch disappears by the end of the shorter versions, but Roby mentions that, when Helton died, she “was denied the rites of Christian burial.” She’s presented as a far less sympathetic witch.

Presumably, some audience members might identify with the two male characters. But would anyone sympathize with them? The men act primarily to deny Lady Sybil her freedom. To accomplish this, Lord William turns to witchcraft — the very thing he later forbids his wife to practice — so what starts with frustration quickly escalates into hypocrisy with scoop of obsession on the side. Hardly admirable. Why did the miller’s assistant cut off the cat’s paw? Only in Roby’s detailed narrative do we find a motive: he was protecting the mill from the “hell-cats,” the preferred form assumed by witches and warlocks. Upon being attacked by “a prodigious company of cats, bats, and all manner of hideous things,” the assistant fought back with a knife, too overwrought to do more than cut off one cat’s paw. Inadvertently, he exposes the shapeshifter’s identity. More than doing the kindly or heroic thing in regard to Lady Sybil, these male characters just react strongly to being spurned by her or to clashing with her creepy-critter squad.

Even after death, Lady Sybil — or, at least, her spirit — remains bound. Earthbound. Roby says that, on her deathbed, the repentant woman “looked up to the Mercy she invoked, and was forgiven.” Both Harland and Thiselton-Dyer explain: “the devil’s bond was cancelled.” Holden says she was “rescued from the powers of darkness.” Despite all this forgiveness, cancellation, and rescue, she’s not allowed to enter Heaven. Well, at least, some part of her is obligated to return annually to perform what might be called a tableau mort for those brave enough to wander by Eagle’s Crag on Halloween.

There is no triumph here. Only tragedy.

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THE

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THEWHISPERS OF WITCHERY

MAIN PAGE.

May 21, 2023

Researcher’s Intuition Says Clerk Island Will Be My Last Mapped Mirage of the Arctic

A couple of weeks ago, I added Sannikov Land to my Crocker Land and Other Mapped Mirages of the Arctic page. That inspired me to research Clerk Island, too. I found a map marking the spot where a trustworthy explorer had seen it, just as I had with Sannikov Land, President’s Land, Kennan Land, Crocker Land, and Bradley Land. (I’m still looking for a map that includes Plover Land.) The common thread here, though, is: none of these spotted, named, and mapped patches of earth were actually there. It’s typically assumed that they were merely mirages. Now, my chronological list shows that such Arctic apparitions appeared roughly every twenty years throughout the 1800s and into the 1900s.

Clerk Island was first observed by John Richardson on August 1, 1826. A physician and naturalist, Richardson was part of an effort to chart the northern coast of Canada and Alaska while also learning what wonders were there. This was the second expedition led by John Franklin, a name that might have a familiar ring. He was the same captain whose third Arctic voyage about twenty years later would end with 129 crew members perishing, even though they were on two different ships. It remains one of the greatest tragedies and mysteries of Arctic exploration.

But we’re concerned with Franklin’s earlier expedition. While the captain led one contingent westward, Richardson led another eastward. He explains that — after observing a river that he named for John Croker, Secretary of the Admiralty — he noticed “a high island, lying ten or twelve miles from the shore, which received the appellation of Sir George Clerk’s Island.” At the time, George Clerk was serving as a Lord of the Admiralty. Richardson’s geographical discovery would, over time, be shortened to “Clerk Island.”

I added a red star to help locate Sir George Clerk’s Island on the above section of a map published in 1828. With the help of Internet maps about two centuries later, we can still find Cape Parry and Darnley Bay. To the southeast lie Cape Lyon and the mouth of the Roscoe River. Farther on run both the Buchanan and Croker Rivers. All these landmarks remain with the same names, suggesting the 1828 map was impressively accurate!

Clerk Island Erased from the MapBut then why doesn’t Clerk Island, northeast of the Croker River outlet, not also appear on Internet maps? Well, subsequent explorers were unable to confirm its existence. For instance, Richard Collison reports that he couldn’t verify it when he was exploring the region onboard the H.M.S. Enterprise in 1853:

The weather continuing very hazy gave us only occasional glimpses of land, and we ran past Clerks Island without being able to distinguish it.Can we blame the haze for that? Maybe so, but while traversing the same region in 1905, Roald Admunsen sent a cablegram saying: “We passed near Clerk Island without seeing it.” Unfortunately, he provides no indication of visibility.

Vilhjalmur Stefannson (1879-1962)

Vilhjalmur Stefannson (1879-1962)More non-sightings came in 1910 and again in 1911, both by Vilhjalmur Stefannson, who admits to being particularly driven to settle the issue. He reports that he was searching by land — the way Richardson had seen Clerk Island — and the weather during his second attempt was very different from what Collison had experienced decades earlier. Yet the result was the same:

The weather on this portion of our eastward journey had fortunately been clear, and although the mountains of Victorian Island itself, sixty miles away, were clearly visible, there was no sign of Clerk Island.Stefansson goes on to say that he continued the hunt onboard a ship called the Teddy Bear. Still nothing. Even after that, the ship’s captain “cruised backward and forward over the site without discovering even a sign of a shoal or sandbank.” What, then, had Richardson seen all those years earlier, seen with enough certainty to name it for a Lord of the Admiralty?

It might be a pretty easily solved puzzle. In Report of the Canadian Arctic Expedition, 1913-18, published in 1924, Kenneth G. Chipman and John R. Cox reflect what probably had become the prevailing thinking by then:

The weight of evidence seems to be that the island is non-existent and should be omitted from maps. Richardson mentions ice in the vicinity when he saw and named the island[,] and it is quite probable that he saw dirty ice and mistook it for an island--a mistake easily made.And Yet Whalers Have Good EyesStefansson would very likely have agreed with the dirty ice theory. Probably. Maybe. I suspect one of the reasons he worked so hard to settle the issue was because of something he had heard from reliable sources. Stefansson writes:

I have spoken with American whalemen who say they have seen the island. Captain S.F. Cottle of the steam whaler Belvedere is sure not only that he has seen it but that it is in the location where the chart puts it.Okay, that’s interesting! About the same happened with Sannikov Land. First reported by Yakov Sannikov around 1805, the land that later bore his name was then not found in the 1820s — and then re-found in 1886! Eventually, it was decided that Sannikov Land was no land at all, but it kept appearing on maps until at least 1922.

I don’t know quite what to do with this. But I do have a strong hunch that Clerk Island will be the last entry on my Crocker Land and Other Mapped Mirages page. My research hasn’t given me any more leads to additional examples.

That said, those spectral stretches of rock and rubble in the icy north have proven themselves to be terribly sneaky.

— Tim