Tim Prasil's Blog, page 9

October 22, 2023

Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit: A Phantom Locomotive at Broad Street Station in Newark, New Jersey

Ghosts Tied to Time

Ghosts Tied to TimeThere’s something weirdly appealing about the idea of an “anniversary ghost.” This is a spirit who, though having moved on to another dimension, returns to the physical realm on a strict schedule. Henry Holt Moore, writing in 1891, contrasted such old-fashioned ghosts to the new, nineteenth-century kind, which “come at no yearly anniversary….” However, in her 1919 memoir, Ghosts I Have Seen and Other Psychic Experiences, Violet Tweedale relates her neighbor’s “very tantalizing experience” with an anniversary ghost, saying the encounter happened “a very few years ago….” The neighbor saw the apparition and became enchanted by it! He noted the date and, to be sure, witnessed it again exactly one year later. Such annual manifestations have many precedents, and if I lived in a haunted house, I’d prefer such a spectral housemate — I could either make popcorn and await its performance or, if that proved too unsettling, make plans to be elsewhere that night.

All of this helps to explain why, in 1873, a large crowd gathered in Newark, New Jersey, to witness a phantom locomotive said to manifest with the regularity one might expect from a more tangible train. It was reputed to leave Broad Street Station on the 10th of every month. Let me begin at the beginning, though.

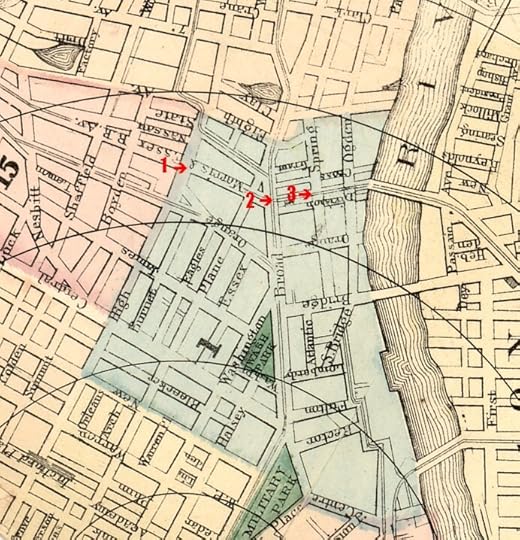

A Wreck on a Wet, Autumn NightOn September 26, 1868, a train tragedy occurred in Newark, which the New York Herald described the next day as a “collision of a serious character.” On the 28th, a fuller account appeared in the Elizabeth Daily Monitor, and here we learn that the collision involved a train belonging to the Morris & Essex Railroad (M&E). The engine, hauling 36 cars of coal, “was brought to a standstill at High street, on the heavy down grade of the road, about one-eighth of a mile from the depot….” (See 1 on the map below.) Battling gravity and wet tracks, engineer Nathan Nichols was unable to keep the train from slipping downhill, and it resumed its course “with fearful velocity.” The fireman, brakeman, and conductor each managed to leap off before the engine collided with another train sitting at Park Street. (See 2.) With Nichols still at his post, the coal train derailed. It continued on, sideswiping “a dwelling house, occupied by a family named Conkling, on the northeast corner of Spring and Division streets.” (See 3.) This was enough to bring the runaway locomotive to a terrible halt.

I rotated this section of an 1875 map to make it accord with a typical “north-up/south-down” orientation. As revealed on this current map, some of the streets have changed, but the tracks (named “Morris & Essex R.R. Av.” above), Broad Street, Division Street, and Military Park all remain. High Street appears to have been renamed MLK Boulevard, and Washington Park is now Harriet Tubman Square.

I rotated this section of an 1875 map to make it accord with a typical “north-up/south-down” orientation. As revealed on this current map, some of the streets have changed, but the tracks (named “Morris & Essex R.R. Av.” above), Broad Street, Division Street, and Military Park all remain. High Street appears to have been renamed MLK Boulevard, and Washington Park is now Harriet Tubman Square.Miraculously, the Conklings survived. However, when the rubble was cleared, Nichols was found dead. His funeral was held at the Eighth Avenue ME Church, being presided over by the Reverend Charles E. Little, and the trainman was buried in Evergreen Cemetery. Oddly, later that same night, Michael Burns, a M&E flagman at the Broad Street crossing, was run over while attempting to shepherd pedestrians away from another passing coal train. He died, too. A later report says he was considered “a victim to his own carelessness,” which strikes me a harshly worded when considering his kind effort.

Apparently, the M&E Railroad approved of the patented Thomas system of keeping track of luggage, enough to lend their name to the advertising.A Phantom Locomotive Reported

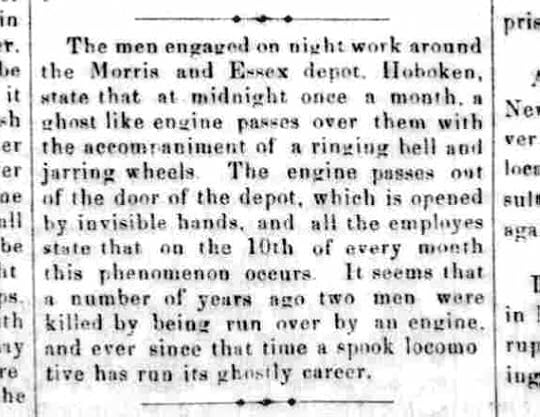

Apparently, the M&E Railroad approved of the patented Thomas system of keeping track of luggage, enough to lend their name to the advertising.A Phantom Locomotive ReportedFive years later, a phantom locomotive was reported to appear at the Broad Street Station. It was tied to that night of death and narrow escapes. For some reason — maybe simply the passage of time — the earliest report I’ve found links the manifestation to Hoboken, where Nichols was headed, instead of to Newark, where he died.

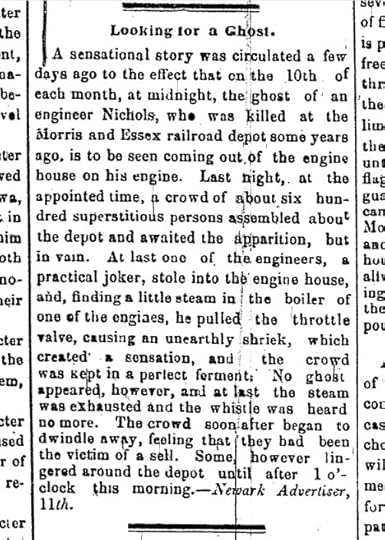

From the February 13, 1873, issue of The Jeffersonian, a newspaper published in Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania

From the February 13, 1873, issue of The Jeffersonian, a newspaper published in Stroudsburg, PennsylvaniaSubsequent reports confirm that the phantom train was witnessed in Newark, though, and the figure of Nichols was observed sitting in the engineer’s seat. Here’s an article published a couple of days later:

From the February 15, 1873, issue of the Schenectady Evening Star (though attributed the Newark Advertiser)

From the February 15, 1873, issue of the Schenectady Evening Star (though attributed the Newark Advertiser)From there, the news traveled to places such as Maine, Virginia, Ohio, and Tennessee. All of the newspapers in these states attribute Newark’s Courier as their source, saying that the wreck that led to Nichols’ death had occurred on October 10th. This is incorrect, of course, but without the remarkably handy technology of online archives, who would know? Admittedly, this mistake, the failure of the spectral locomotive to appear, and the “practical joker” mentioned above combine to give this case the fragrance of a hoax or, at the very least, of a tall tale.

Is It Still Worth Investigating?Despite the reasons to doubt the story, the specificity of the backstory — the fact that the apparition can be traced to an actual wreck with verifiable fatalities — adds a pinch of credibility. Besides, who isn’t a sucker for a phantom locomotive? The site is conveniently located, too, and Division Street, where the runaway train finally halted, is walkable. Therefore, I say it’s worth some spook-snooping.

The building around which all those hopeful but disappointed ghost-seers had gathered in 1873 was eventually demolished, and the present Broad Street Station was put in its place in 1901-1903. Nonetheless, this new structure is rich in history, making it worth a visit for train enthusiasts. For those more interested in the paranormal, Newark has more than just the Jersey Devil to make it interesting, from a witch named Moll DeGrow to a ghost named Annie Crest. It’s also the home of Henry William Herbert (1807-1858), a founding writer of occult detective fiction. In a spooky twist, the very same year that engineer Nichols’ ghost was reputed to have returned, author Herbert’s ghost made news, too!

As always, if you conduct even a casual ghost hunt in the area of Park Street Station, please share your findings below.

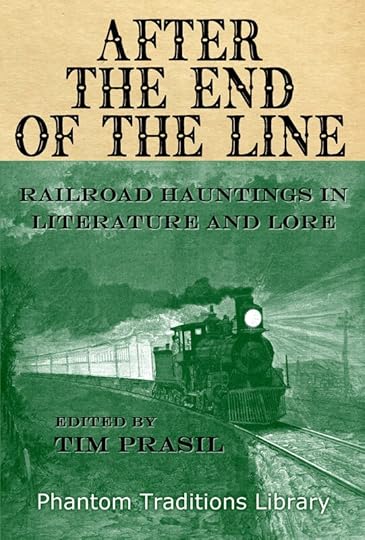

Discover more “Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit” at the page forAfter the End of the Line: Railroad Hauntings in Literature and Lore

October 15, 2023

Edgar Allan Poe’s Connection to Charles Fenno Hoffman

So far, there are only two authors found on the “American Authors of the Early 1800s” shelf here at Brom Bones Books: Edgar Allan Poe and Charles Fenno Hoffman. Kelly Keener, editor of the latter book, recently posted a fascinating piece on how these two authors’ lives and work overlapped. Please enjoy it!

Edgar Allan Poe’s Connection to Charles Fenno Hoffman

— Tim

October 1, 2023

The Syderstone Investigation, Part 2: The Ghost Hunters Divide

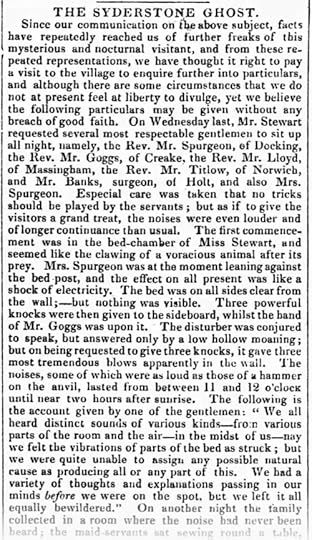

When news of ghostly disturbances at Syderstone parsonage hit English papers in 1833, a dash of local gossip about the haunting was sprinkled into the report. After reviewing the facts of the case, London’s Weekly Dispatch (May 6, 1833, pg. 4) added: “It had been formerly reported in the village that the house has been previously haunted by a Rev. Gentleman who died there about 27 years ago…”. Subsequent reports name this suspected spirit “Mental” — later correctly identified as “William Mantle” — but then testimony given by Elizabeth Goff, the deceased clergyman’s servant, suggested strange phenomena was already present when he arrived there in 1785. Besides, Mantle appears to have died in 1797, which would have been 36 years earlier, making the reported “about 27 years ago” a bit timey-wimey.

Goff’s testimony, however, was not taken to dispel rumors about the ghost of William Mantle lingering at Syderstone parsonage. As discussed in Part 1, it was intended to refute allegations that the haunting was a ruse created by one or more of its current, very-much-alive residents: the family of the Reverend John Stewart. If a former curate had found the parsonage haunted when he got there, then the present curate’s claim to have done the same is substantiated.

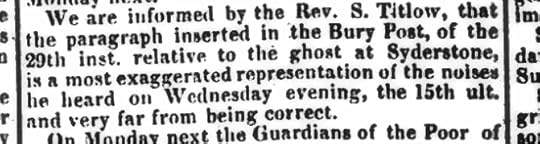

Tensions Rise Between a Ghost Hunter and the PressThen the press announced that Stewart had organized a ghost hunt at the parsonage, one comprised largely of his clerical colleagues. The article first appeared in the Bury and Norwich Post on May 29, 1833, and I show the relevant portion of it in Part 1. But one investigator, the Reverend Samuel Titlow (c. 1793-1871), was quick to issue a correction about what had occurred during the investigation. Curiously, Titlow’s complaint appeared first in a rival paper, the Norwich Mercury.

Norwich Mercury, June 1, 1933, pg. 3

Norwich Mercury, June 1, 1933, pg. 3With a raised editorial eyebrow, the Post replied:

Bury and Norwich Post, June 5, 1833, pg. 3. On the front page of their June 12 issue, the Post admits that Titlow had written them a letter about his concerns, but it “did not reach us till after our publication.” After printing the letter itself, the editor expresses regret for the earlier snarky comment.

Bury and Norwich Post, June 5, 1833, pg. 3. On the front page of their June 12 issue, the Post admits that Titlow had written them a letter about his concerns, but it “did not reach us till after our publication.” After printing the letter itself, the editor expresses regret for the earlier snarky comment.With an ecclesiastic eyeroll, Titlow wrote to the Norfolk Chronicle, yet another competing paper. It was common practice for newspapers to freely reprint — often, word-for-word — what had appeared in other papers, and the Chronicle had done exactly that with the Post’s report on the ghost hunt. (There’s a reprint of the latter article here.) Apparently, Titlow was covering all bases by writing to multiple journals.

Norfolk Chronicle, June 8, 1833, pg. 3. A reprint of the entire letter is available here.

Norfolk Chronicle, June 8, 1833, pg. 3. A reprint of the entire letter is available here.Titlow’s goal was not to completely deny what had been reported in the Post. There were noises — but they were not loud noises. There were knocks — but they were neither powerful nor most tremendous knocks. There was a scream — but it did not alarm him.

Wait. There was a scream? An unalarming scream? Isn’t that a contradiction in terms? What Titlow proceeds to say about this scream is important because — while others were working to shield the Stewarts from the stigma of committing a hoax — he declares that there is at least a possibility of something very much like that at work:

I cannot speak positively as to the origin of the scream, but I cannot deny that such a scream may be produced by a ventriloquist. The family are highly respectable, and I know not any good reason for a suspicion to be excited against any one of the members; but as it is possible for one or two members of a family to cause disturbances to the rest, I must confess that I should be more satisfied that there is not a connection between the ghost and a member of the family if the noises were distinctly heard in the rooms when all the members of the family were known to be at a distance from them.From this point on, we’ll see that tensions between the ghost hunter and the press were redirected, causing a division between Titlow and his co-investigator, the Reverend John Spurgin (1787-1857).

From

A Country Curate’s Autobiography

(1836). This is the best picture I could find that’s at least vaguely related to the Syderstone case.Tensions Rise Between Ghost Hunters

From

A Country Curate’s Autobiography

(1836). This is the best picture I could find that’s at least vaguely related to the Syderstone case.Tensions Rise Between Ghost HuntersAt first, Spurgin had joined Titlow in attempting to assure the public that, while the ghost hunters had encountered strange sounds without discovering an explanation for them, the press had exaggerated things. In a letter that appeared beside Titlow’s in the Chronicle (reprinted here), he gives his own account of the night’s activity and, at one point, declares that the Stewarts were not responsible. After discussing the knocks, he turns to moans and groans. These seemed to come

from the bed of one of Mr. Stewart's children, about ten years of age. From the tone of voice, as well as other circumstances, my own conviction is, that these 'moans' could not arise from any part of the child. Perhaps there were others present who might have had different impressions....It’s very likely that, once Spurgin’s letter was printed, he saw Titlow’s encouraging further investigation with the Stewarts “at a distance.” He might also have read John Baker publicly contending that a ventriloquist was behind the haunting (as discussed in Part 1), though apparently Baker wasn’t the only one putting forth that idea. Very definitely, Spurgin wrote additional letters intended to defend the Stewarts’ innocence. In one, he opens by saying that mounting aspersions against the family impelled him to protest:

Norfolk Chronicle, June 15, 1833, pg. 3

Norfolk Chronicle, June 15, 1833, pg. 3Titlow saw Spurgin’s follow-up letter as a personal attack. In his own second letter to the Chronicle, Titlow reminds readers that he had carefully praised the Stewarts’ respectability while also contending that “it is possible for one or two family members to cause disturbances to the rest.” He merely pointed out the possibility and then nudged Stewart toward allowing an investigation with the family absent to help arrive at some substantial conclusion about the case.

Titlow also challenges Spurgin’s claim about hearing scratching when the Stewarts were “a considerable distance from the spot.” He says:

Norfolk Chronicle, June 29, 1833, pg. 3

Norfolk Chronicle, June 29, 1833, pg. 3Sure enough, Spurgin wrote to the Chronicle yet again. It would be tiresome to detail all of the retorts in this long letter. It’s a bit like reading the comments on social media, and doing so reveals that the era’s Anglican Church leaders certainly could get hot under the collar. Suffice to say, Spurgin accuses Titlow of not practicing “Christian love” and of “bearing false witness against an unoffending brother”:

Norfolk Chronicle, July 13, 1833, pg. 4

Norfolk Chronicle, July 13, 1833, pg. 4Dang! The Reverend Spurgin accused the Reverend Titlow of being a bad Christian, doing so in a public forum! He next turns to that evidence noted above, the witness testimony supporting the claim that the weird noises didn’t start with the Stewarts. Spurgin ends by addressing Titlow’s suggestion that Stewart allow an investigation with the family absent, saying that the phenomena is random — it might go quiet when the ghost hunters waited there — so “the experiment therefore so loudly called for becomes too hazardous to be adopted.” Point taken.

But had Titlow “loudly called for” such an experiment? Didn’t he simply say he would be more convinced the case wasn’t a hoax “if the noises were distinctly heard in the rooms when all the members of the family were known to be at a distance from them”? Was it unreasonable to determine whether or not the Syderstone haunting was like the debunked ones on Cock Lane in 1762, in Stockwell in 1772, or in Hammersmith in 1804? Would Spurgin have been so invested if Stewart has been, let’s say, a cobbler instead of a curate? Perhaps, lurking beneath it all, Spurgin saw the mere suggestion of testing for a hoax as a challenge to church authority, to a sovereignty too sacred, too unquestionable, or even too fragile to allow for such a trial.

If nothing else, the division between Titlow and Spurgin indicates a difficult decision facing ghost hunters before and after them. Those in Spurgin’s congregation might argue that, when paranormal investigators test for fraud, they cast a specter of doubt over people claiming to be already haunted. The acolytes of Titlow, however, might see debunking as one form of exorcism, allowing those same people to sleep better.

GO TO The SyderStone Investigation, Part 1

September 24, 2023

The Syderstone Investigation, Part 1: The Ghost Hunters Gather

There’s an unusual amount of historical material available regarding an 1833 ghost hunt held at the parsonage in the hamlet of Syderstone, Norfolk, England. The head of the haunted house was a clergyman named John Stewart, who described the unaccountable manifestations as tapping and scratching, groaning and sobbing, and tramping and knocking. The latter noises became particularly loud. The phenomena, strictly auditory and heard in every room, had occurred ever since the Stewarts had arrived, and the curate says he had traced the haunting back sixty years! Indeed, the disturbances were continuing when he described them in a letter dated 1841, eight years after his family had taken up residency.

When the ghost hunt occurred, the alleged haunting had made its way into the press already. The May 6, 1833, issue of London’s Weekly Dispatch is the earliest report I’ve found. According to the article, the inexplicable knocks, moans, clangs, and crashes, were on the rise, “becoming more violent” and scaring away one servant. The ruckus began nightly at 2:00 a.m. and continued until daylight. Numerous witnesses confirmed them, and “several ladies and gentlemen, to satisfy themselves, have remained all night,” all to no avail. Equally futile were Stewart’s efforts to communicate with “the supposed ghost” and “to exercise his spiritual authority to exorcise it.” This report then spread to other papers, drawing attention across Britain and eventually across the Atlantic.

As hinted at above, Stewart encouraged investigation at first. In fact, he organized a formal probe to be held on the night of May 15/16, 1833, and this sparked a series of newspaper articles that provide the bulk of what is known about the case. One key article (see below) lists the people who Stewart summoned to form the investigation team and the towns from which they came. With the help of an 1836 Norfolk directory and a few other sources, I double-checked where they lived while adding first names. The investigation team was comprised of:

the Reverend John Spurgin, who traveled from Docking;Maria Spurgin, née Dewing (so named in this source and this source), who presumably accompanied John, her husband;the Reverend Samuel Titlow, who came from Norwich;the Reverend Henry Goggs, who came from Creake;the Reverend John Lloyd, who came from Massingham according to the newspaper, but resided in Hindolveston according to the directory of three years later; andJohn Banks, a surgeon who came from Holt.Stewart gives a brief description of the ghost hunt in a letter written a week afterward, which is reprinted in Elliott O’Donnell’s Ghostly Phenomena (1910). But more details were publicized in the May 29, 1833, issue of The Bury and Norwich Post. Here it is:

The report goes on to describe additional experiences of the family and household staff. It ends by acknowledging “the respectability and superior intelligence of the parties who have attempted to investigate into the secret” while also assuring readers that a physical cause will be discovered.

In the weeks to follow, both John Spurgin and Samuel Titlow publicly stated that this report was exaggerated. Sure enough, they had heard a series of knocks — some that matched the number requested by investigators — along with a moan and even a scream! They didn’t deny they heard strange sounds that they couldn’t explain, but they simply wanted it known that these weren’t quite as dramatic as described in the Post article.

Spurgin’s and Titlow’s respective rebuttals also sparked a split between the two ghost hunters regarding where to focus future investigation. I’ll dive into this rupture in Part 2, but to better understand that, it’s helpful to look at what others were saying about the Syderstone haunting.

The Ventriloquist Theory and Its ImplicationsIn the June 9, 1833, issue of The Norfolk Chronicle, John Baker of Leeds proposed a solution to the mystery: ventriloquism. In a fairly long letter to the editor, Baker opens by saying he was hesitant to offer his theory in the hope that something more certain would come to light. Since it hadn’t, he describes a situation that had occurred in his own house twenty years earlier. A quiet knocking was heard at night, disturbing the servants. Thinking it might be a rat, Baker and his staff then heard “a noise as if that animal was biting the boards.” That would have settled things, but the nightly disruptions grew louder. Baker says that

the rapping was like wagging of the tail of a pointer dog against a door, and the scratching like that of a cat against the boards violently -- the noise was too loud for a rat.... I was, I confess, rather 'bewildered.'And yet Baker suspected one of his servants was the culprit. Interestingly, he says he wanted to find out if she was “a ventriloquist,” not a hoaxer or a prankster. He then conducted a series of simple tests, the last of which

fully satisfied me that the whole was done by this person, she having the power of ventriloquism or conveying sounds to a distance.... I discharged the servant and we were no more troubled by the Ghost.Baker concludes by declaring his conviction that “the Syderstone Ghost is a ventriloquist….” However, since the Post had already reported that the members of the May 15/16 ghost hunt were drawn to activity “in the bed chamber of Miss Stewart,” there’s a serious implication here, especially for a clergyman in 1833. Baker was not simply pointing out that there is nothing supernatural happening in Syderstone parsonage. Neither was he exactly suggesting the noises there spring from a mischievous servant, one who could be promptly dismissed. No, given the ghost hunters’ findings, Baker’s implication is that the haunting is a deception created by one of the respectable Stewarts.

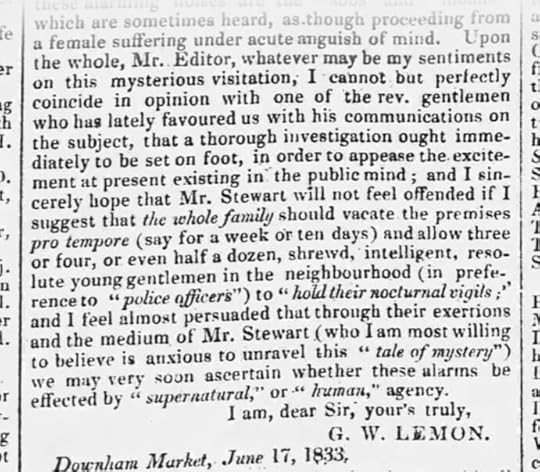

This explains why G.W. Lemon wanted to launch in his own investigation — with the family absent. In the June 19, 1833, issue of the Post, Lemon explains that he visited the Stewarts to see if he could conduct his own ghost hunt. He was refused because “the family had been so much harassed of late by acceding to the wishes of the public, that they had been as it were compelled to decline the admission of of any further nocturnal visits.” Nonetheless, the Stewarts told Lemon of continuing disturbances that the papers hadn’t yet reported. Creaking footsteps heard in the attic had descended to the curate’s bedroom. A crash had sounded like some heavy metal object falling through the roof, and another one seemed to be a door “wrenched from its hinges and hurled with violence against the floor.” All the while, sobs and moans were heard.

Still aching to investigate (and very likely referring to a letter-to-the-editor written by Titlow), Lemon ends the letter this way:

If the phenomena ceased with the Stewarts away, they would be implicated, and if it continued, they would be exonerated. But there was another way to determine the Stewarts’ innocence. What if it could be shown that the phenomena had been witnessed before the family ever moved in?

Testifying It Wasn’t Someone in the FamilyThe Chronicle did exactly that in their June 22, 1833, issue. An article signed by Thomas Seppings and John Savory presents testimony from five people who had served previous clergymen at the parsonage, a visitor who had slept there, and a shepherd who — while walking by when the place was unoccupied — had heard “very loud ‘groanings’ like those ‘of a dying man'” coming from deep inside. Seppings and Savory open by saying that the witness accounts were collected to inform the public as well as to protect the Stewarts from “the most ungenerous aspersions….”

Other than what the shepherd reported, the witness evidence becomes a bit repetitive in terms of noises heard but never explained: knocks, crashes, a door opening, furniture dragged, and glass and china rattling. You can read the full report here. What’s more important is that Syderstone parsonage had been a site of unusual, if not ghostly, phenomena for about twenty years before the Stewarts arrived.

However, Samuel Titlow, one of the May 15/16 ghost hunters, refused to rule out the possibility that a family member had a hand in creating the weird noises. On this point, he sharply differed from his co-investigator John Spurgin. How they made their disagreement very public is discussed in The Syderstone Investigation, Part 2: The Ghost Hunters Divide.

Part 2 will be posted on Sunday, October 1.

September 17, 2023

Did These Two Works Inspire Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None?

I suffer from a recurring itch to dig into the history of . I can fill in that blank with “fictional occult detectives” or “actual ghost hunters” or, well, almost anything else. This itch began to twitch again — if, indeed, an itch does twitch — when I learned my local community theater will perform a stage adaptation of Agatha Christie’s 1939 novel And Then There Were None. It’s among the author’s most popular works, but it’s also unusual. Ten people answer invitations to come to an isolated house on an isolated island. One by one, they are found murdered, and the surviving guests deduce that the culprit must be among them. The plot doesn’t fit with the traditional mystery, which spotlights a detective methodically solving a crime in the manner of, let’s say, Christie’s Miss Marple or Hercule Poirot. Instead, And Then There Were None seems to fit better into the “old dark house” subgenre.

Agatha Christie as she appeared in a 1923 issue of The Illustrated London News

Agatha Christie as she appeared in a 1923 issue of The Illustrated London NewsLooking into earlier examples of old dark house works, I came upon a 1934 movie called The Ninth Guest. You can find it at the Internet Archive. It’s a fun, offbeat film, probably improved by being fairly short — barely over an hour — and by its interesting parallels to Christie’s novel. It’s based on a 1930 novel, titled The Invisible Host and written by Bruce Manning and Gwen Bristow, which has been cited as possible inspiration for Christie. Both open with a cast of characters gathering in a spot from which they can’t escape, next a disembodied voice informs them they’re going to pay for their crimes, and then there’s a series of carefully timed deaths. The notion that Manning and Bristow influenced Christie has weight, though I confess I say this having only seen the movie.

Traveling further back in time, I came upon another contender. It’s Anna Katherine Green’s 1905 novella The House in the Mist. Green is a very important figure in mystery history. Her Ebenezer Gryce was a bestselling series detective before Sherlock Holmes appeared, and she is frequently named as one of Christie’s influences. Like The Ninth Guest and And Then There Were None, this tale involves yet another circle of scoundrels coming together and, well, you can guess the general drift of what happens to them. All I’ll say is the pacing of Green’s novella is very different from the 1930 and 1939 novels, but we’re in similar extracting-wholesale-justice territory. All three mysteries involve a murderer who’s hidden in plain sight, and all three lack some smarty-pants detective getting in the way.

Anna Katherine Green as she appeared in the 1903-1904 edition of Illustrated Catalogue of Books, Standard and Holiday

Anna Katherine Green as she appeared in the 1903-1904 edition of Illustrated Catalogue of Books, Standard and HolidayIt might be impossible to determine if Christie, while pondering And Then There Were None, gave any thought to how she might put her own spin on Green’s mystery of over three decades earlier. Certainly, the younger author was familiar with the spooky tunnel of mystery fiction that takes readers to an old dark house. Such works were especially popular on the stage and on the silent screen in the 1920s. Think of Mary Robert Rinehart and Avery Hopwood’s 1920 play The Bat, adapted from Rinehart’s 1908 novel The Circular Staircase, or John Willard’s 1922 play The Cat and the Canary. Both have been put on film repeatedly. J.B. Priestley’s 1927 novel Benighted led to the 1932 movie The Old Dark House, which gave the subgenre a name.

But was that when the subgenre budded, as some suggest, or when it blossomed? Can we trace things back to works published even before Rinehart’s novel? Green’s The House in the Mist employs at least three basic elements that those later examples latched onto tightly: crappy weather, the well-attended reading of a will, and a house with secret passageways. To be sure, the “tangled hedges” surrounding the “long, low building” that serves as Green’s title dwelling foreshadow the gnarly evils of the lowly guests who assemble there. The setting, in other words, is a dark house, though perhaps not quite yet an old one.

On a related note, it’s entirely possible that I’ve started a new research project. After all, when an itch starts to twitch…

— Tim

September 10, 2023

Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit: A Crossing Near Little York Station in Toronto

A Tangle of Tracks

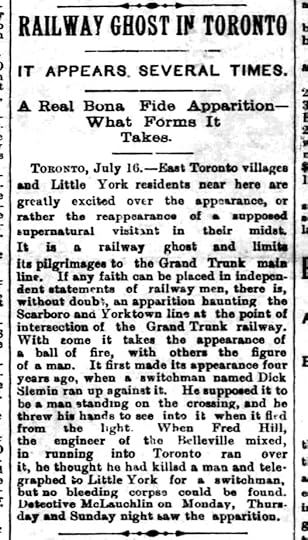

A Tangle of TracksOn July 16, 1890, at least two Canadian newspapers reported on an apparition witnessed by multiple people near what was then called Little York Station. A short piece appeared in The Montreal Star, and one with more details in The Winnipeg Tribune. Here’s the longer report:

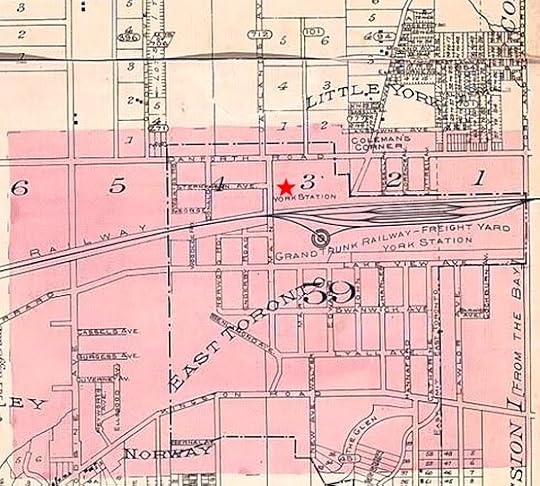

In 1890, East Toronto and Little York were villages just outside of Toronto. Their borders are no longer clearly marked, but it’s easy to locate where they were, and an 1890 map (shown below) reveals how close they were to a hub/freight yard belonging to the Grand Trunk Railway. Unfortunately, I haven’t had much luck in zeroing in on that intersection with “the Scarboro and Yorktown line” mentioned in the article above.

Nonetheless, the shorter report in The Montreal Star offers a promising clue. It mostly summarizes what The Winnipeg Tribune says, but it adds that the crossing is a place “where many persons have been run over and killed.” I went searching for earlier reports of railroad-related deaths in that vicinity, and to be sure, I found several. They’re all linked to Little York station, which also went by the simpler name “York Station.”

(Little) York Station on a day of low traffic.

(Little) York Station on a day of low traffic.Glance down at that old map, and you’ll see that the station house sat just north of a tangle of tracks. This area of congestion begins to explain why, in October of 1886, three people died when they left one train and, “getting out of the way of a following train, stepped in front of an engine on another track.” The next year, Robert McDonald “was killed by a train” after his foot was ensnared by a railroad frog. Later that year, an “engine killed an unknown man near Little York station.” In 1889, a railroad employee “named John Donahue was run over and instantly killed” at the very same station.

I added a red star to indicate where the station is on this detail of a map found in Atlas of the City of Toronto and Vicinity, published in 1890. Scroll down to “Toronto — Eastern District”/Plate 50 at this page of an impressive website impressively named Recursion: Adventures from a Fractal Life.

I added a red star to indicate where the station is on this detail of a map found in Atlas of the City of Toronto and Vicinity, published in 1890. Scroll down to “Toronto — Eastern District”/Plate 50 at this page of an impressive website impressively named Recursion: Adventures from a Fractal Life.It’s entirely possible that there were additional fatalities at Little York Station, and I have a strong hunch that the multiple ghost sightings reported in the papers occurred not far from that treacherous hub.

Where Once Was Is NowLike waves of gravy spreading over cheese curds and fries, East Toronto annexed Little York — and then Toronto annexed East Toronto — shortly after the turn of the century. The street names remain largely the same today, though, and the two long-lost villages linger in Little York Road and East Toronto Athletic Field. If you find the corner of Danforth Avenue and Main Street and follow Main down to the tracks, you’ll see that Little York Station has been replaced by the present Danforth Station. In other words, where the old station stood is easy to locate.

While current tracks follow some of the old lines, it appears that the deadly tangle of over a century ago has been unraveled. Trains continue to run there, and the rails are fenced off for good reason. Ghost hunters should avoid snooping along them and stick to the much safer, parallel walkways to the north and south. Whether you conduct a formal investigation or simply happen to wander by some evening, please jot down your observations in the comments below.

And should the Toronto Ghosts and Hauntings Research Society update their Self Guided Walking Tour of that beautiful city, I hope they consider adding this curious bit of history.

Discover more “Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit” at the page forAfter the End of the Line: Railroad Hauntings in Literature and Lore

September 3, 2023

A Scrap of Evidence that Arthur Conan Doyle Changed the Story of His First Ghost Hunt

Though it might be oxymoronic to say, I’m slightly obsessed with Arthur Conan Doyle’s first ghost hunt. It happened around 1894, but Conan Doyle himself didn’t formally write or speak about it until 1917, after he had become an evangelist for Spiritualism. Not surprisingly, by then, he recounted the investigation in a way that supports the prospect that spirits can and do interact with those left behind on the physical plane.

However, there are bits and pieces of evidence revealing that, at first, the creator of Sherlock Holmes had deduced that the haunting was a hoax. This week, I came across a tidbit that can be added to this small pile. It comes from a newspaper article titled “Was It a Ghost?,” written by Luke Sharp, a pen named used by Robert Barr (1849-1912). The item was widely reprinted — from Blackfoot, Idaho, to Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire — but I believe its earliest appearance was in the April 12, 1896, issue of the Detroit Free Press. Here’s what Barr has to say:

Barr had written for the Free Press for several years before moving from the Great Lakes region to England in 1881. Apparently, he retained a good relationship with his old publisher, since “Was It a Ghost?” was published well after he had become a member of the London literati. It was in this later phase of his life when Barr hobnobbed with Conan Doyle. If he is to be trusted, in the mid-1890s, Conan Doyle spoke of having ended his ghost hunt as a skeptic.

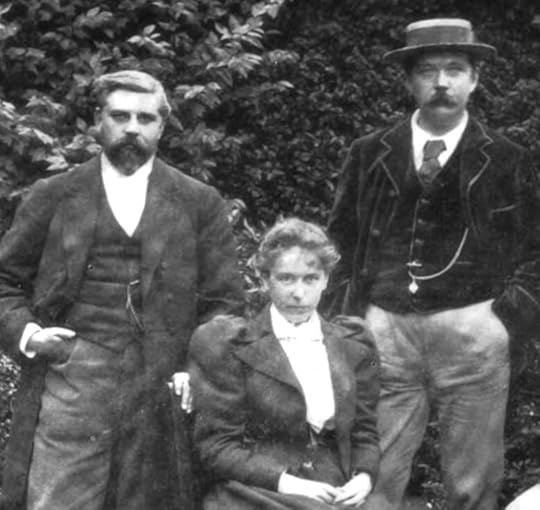

Bryan Mary Julia Josephine Doyle is seen sitting between Robert Barr on the right and her brother, Arthur Conan Doyle, on the left. This photo appears in an 1894 issue of The Idler. (Note to self: watch fobs are cool.)

Bryan Mary Julia Josephine Doyle is seen sitting between Robert Barr on the right and her brother, Arthur Conan Doyle, on the left. This photo appears in an 1894 issue of The Idler. (Note to self: watch fobs are cool.)Frank Podmore was part of the investigation, and — if I correctly identified his 1897 chronicle of what happened (see Case IX) — he judges it to be a hoax. In My Life and Times (1925), Jerome K. Jerome recalls Conan Doyle sharing the story with very different details, but again the outcome is a hoax. Jerome notes that, looking back, the investigation “led [Conan Doyle] to conclusions with which he may now disagree.” Perhaps most tantalizing of all, Conan Doyle himself appears to have recorded his experience in a personal letter to James Payn shortly after the investigation. In The Man Who Created Sherlock Holmes: The Life and Times of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (2007), Andrew Lycett describes this document as providing an account that comes “as close to the truth as possible.” While he doesn’t offer any direct quotations, Lycett suggests that Conan Doyle treats the case as resulting from the prank of a young man. A hoax.

How the Author Formally Told It Years LaterUnless I’ve missed something, Conan Doyle didn’t formally share his experience until addressing the London Spiritualist Alliance on October 25, 1917. (This, by the way, is very close to a year before his son Kingsley died, more proof that this tragedy wasn’t what ignited the father’s belief in Spiritualism.) Luckily, a detailed record of the lecture was published in Light: A Journal of Psychical, Occult, and Mystical Research, where the anecdote about his ghost hunt opens in this way:

[H]e was one of three delegates sent by the Psychical Research Society to sit up in a haunted house in Dorsetshire. It was one of these poltergeist cases, where noises and foolish tricks had gone on for some years. … Nothing sensational came of their visit, and yet it was not entirely barren. On the first night nothing occurred. On the second, there were tremendous noises, sounds like someone beating a table with a stick. They had taken every precaution, and could not explain the noises, but at the same time they could not swear that some ingenious practical joke had not been played upon them. There the matter ended for the time.

But then Conan Doyle tosses in a twist. Years later, he met a resident of the house and was told that, since the investigation, a child’s bones had been unearthed in the garden! There’s no mention of his double-checking this new evidence. Nonetheless, Conan Doyle uses it to validate the claim that paranormal activity happened at the house. It is, he contends, “surely some argument for the truth of the phenomena.”

Conan Doyle retells the anecdote in three books: The New Revelation (1918), Memories and Adventures (1924), and in The Edge of the Unknown (1930). Over time, he adds some details and alters others, which is probably to be expected. However, in each case, he repeats the “epilog” about the discovery of a child’s skeleton to lend credence to the supernatural reality of the haunting.

Of course, the “hardness” of the child’s skeleton is an issue. Were human remains actually found? This was certainly not the first time bones in the backyard or basement had been used to bolster a haunting’s supernatural foundation (a topic I’ve written about before. I also expand on some of the above here.) Was Conan Doyle duped by someone who told him what he wanted to hear? Did the great author himself invent the story to please his Spiritualist-leaning audiences while nudging skeptics to rethink their positions? He went on to promote some fairly farfetched claims, from fairies caught on film to spirits communicating via radio. Did he really believe in all of the phenomena he was publicizing?

In my quieter moods, I like to think that Dr. Conan Doyle had diagnosed the 20th century as suffering from chronic disillusionment. The physician knew the cure involved injecting as many people as he could with a dose of wonderment. Maybe it doesn’t matter if he honestly believed in everything he espoused. Maybe his main goal, his prescription, was to prompt people to think bigger and to think beyond a world without miracles.

— Tim

August 27, 2023

Professor Curjambi and the Threat of Ethnocentrism

I came upon a 1903 short story titled “The Ameer’s Revenge,” written by Rose German-Reed. It features an occult detective character named Professor Curjambi, and it shares a premise with Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) and many folk horror films written much later. The perennial premise is this: antiquated beliefs or “superstitions” mustn’t be snubbed because threats such as vampires, demons, changlings, and animal — including human — sacrifice rituals remain very real. The characters who suffer the consequences of failing to heed this often seem to be British, though I doubt they own the rights thereto. These stories, whether intentionally or not, teach a lesson in the danger of ethnocentrism. Cultural pridefulness. The hubris of assuming one is more civilized and sophisticated than others. Arrogant jerkism.

In German-Reed’s tale, British characters suffer the consequences of not recognizing an Indian monster, even though the British had been a colonial presence in India for many years when the events of the story occur. In fact, one of the main characters, Agnes Rossiter, was born in India, where as a baby she was tattooed with symbols she doesn’t understand as an adult. Imagine that. She’s reminded of her connection to India every time she looks in the mirror, but she’s never bothered to investigate its meaning.

And so, when the monster arrives as clearly signaled by the title, the man required to vanquish it is a professorial occult detective with a solid understanding of Indian realities. German-Reed gives him an Indian-sounding surname, Curjambi, and a face that’s “unmistakably Oriental”. A few years earlier, the British characters in Dracula relied on Professor Van Helsing, a Netherlander, to save them from the toothy Transylvanian. Stoker showed those Continental “hillbillies” know stuff that can save thoroughly modern Brits from being bitten on their, uhm, necks. “The Ameer’s Revenge” feels a bit influenced by Dracula, even though its invading terror and its learned monster-hunter come from farther afield.

Now, while one might see a critique of British colonialism in “The Ameer’s Revenge,” it’s very underdeveloped here. Curjambi’s heroism — in contrast to the Ameer’s villainy — is attributed to his being well assimilated to English life. Like Van Helsing, he straddles English culture and the demonized one. In both German-Reed’s and Stoker’s works, foreigners are branded as evil. The British are their snooty yet sympathetic victims, and it takes a sort of cultural intermediary to act as the Solver of Problems. (Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Brown Hand” is another occult detective story grappling with the aftermath of England’s presence in India. It better blurs the line between good and bad than “The Ameer’s Revenge,” but its smart hero, Dr. Hardacre, is entirely British.)

All of this is my way of saying that “The Ameer’s Revenge” is a pretty blunt story, a supernatural mystery that’s predictable and forgettable. There is a bit of a surprise at the end — maybe — but it’s still a goofy story (with some flagrant logistical flaws for added snickers). Nonetheless, Professor Curjambi meets my criteria of an occult detective, and he’s now an ethnically unique member of the Early Occult Detectives on my Chronological Bibliography.

— Tim

August 20, 2023

Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit: Around a Station House in Clontarf, Minnesota

The Collision

The CollisionIn 1872, a report of a spectral visitation brought international attention to a rural spot in Minnesota. The place was called Randall Station at the time, but it’s now known as Clontarf. The ghost was recognized to be a railroad worker named Connelly, who had died in a wreck a few months earlier. What was his reason for lingering the physical realm? Apparently, Connelly was a devoted employee and not at all happy with having been replaced.

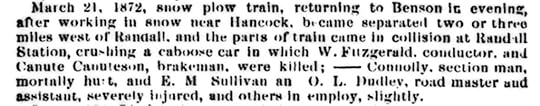

While an article on the March 21 train wreck on the St. Paul & Pacific Railroad — cited as the accident that killed Connelly — doesn’t mention a victim by that name, a subsequent and more officious report does. The two sources give a good account of how a multi-engine train was being used to plow snow along the tracks. One of those engines became detached, but the flying snow prevented the workers from noticing. That separated engine then slammed into the rest of the train after it had stopped at Randall Station.

“Connolly, section man, mortally hurt” is named in a year-end report issued by the Minnesota government. In other sources, his name is spelled “Connelly.”

“Connolly, section man, mortally hurt” is named in a year-end report issued by the Minnesota government. In other sources, his name is spelled “Connelly.”In October, an article in the St. Paul Pioneer points to the disaster while explaining the appearance of Connelly’s vengeful ghost. Though I haven’t found that original report, Minneapolis’s Star Tribune reprinted it, introducing the piece as coming from a trustworthy paper. In the days that followed, the story was picked up by papers in several other states, including The New York Times. It even spread as far England and Scotland. Indeed, news of Connelly’s ghost traveled beyond the reach of the railroad.

Connelly Is Replaced — with ConnellyThe Pioneer article portrays Connelly as having been an exemplary employee. He was “very much attached to his division” and kept “everything right and tidy” there, despite it being on a bleak and blustery prairie. After he was killed, the position was filled by a man bearing the very same surname. This second Connelly is described as “sober, industrious, and intelligent,” not a man one would “suspect of being tinctured in the slightest degree with superstitious notions.” Still, being replaced is one thing. Being replaced by someone with the same name is another. The first Connelly — whose only shortcoming was having died — would let his vexation be known!

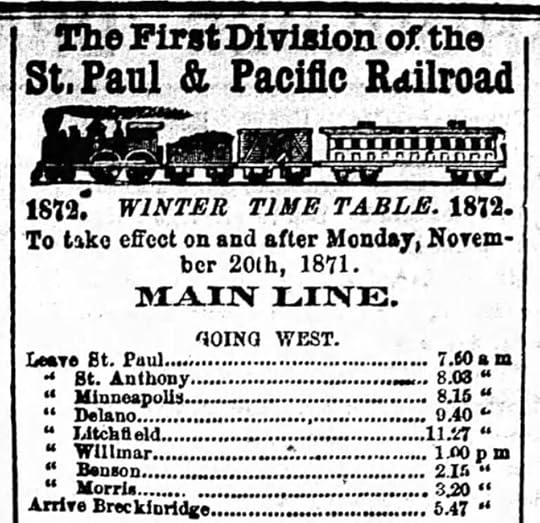

Randall Station was between the Benson and Morris stops. This schedule appeared in The St. Cloud Journal, March 7, 1872, pg. 4.

Randall Station was between the Benson and Morris stops. This schedule appeared in The St. Cloud Journal, March 7, 1872, pg. 4.The ghostly Connelly — let’s call him “Connelly A” for apparition — used various means to express his disdain for the new guy. Let’s call this poor fellow “Connelly B” for breathing. Connelly A visited Connelly B’s bedside, where he “vainly endeavors to tell his tale by unearthly motions, at times apparently entreating, and anon with every appearance of anger and revenge.” The spiteful specter managed to yank the living man out of bed, leaving “the marks of rough handling,” including prints made by hands and fingernails. Connelly A even plagued Connelly B during the day.

There were other witnesses, too. In fact, Connelly B kept quiet about what he was experiencing until other workers saw the figure. They were eating supper when the phantom materialized and “remained long enough to make a number of demonstrations of a revengeful character….” Though the apparition vanished, the horrified men had recognized their former colleague. Only then did Connelly B share what he had suffered, and it was probably shortly thereafter that his experience went viral 1872-style.

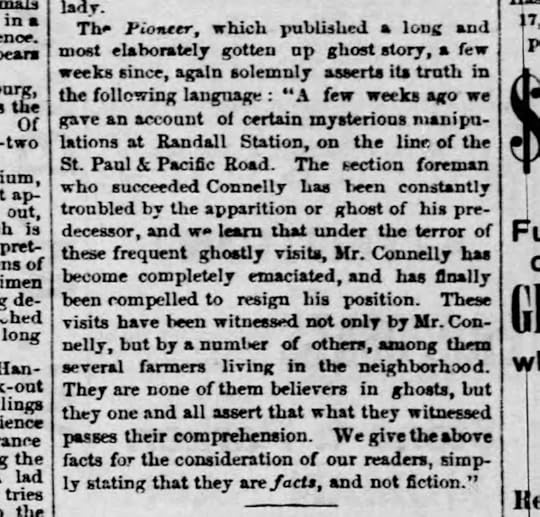

The Pioneer Defends What the Star Tribune DebunksGiven the widespread attention the weird story was getting, it’s probably not surprising that the reliability of the Pioneer was called into question. They defended the original article, however, restating its key points and then affirming that “they are facts, and not fiction.”

From the Star Tribune, November 22, 1872.

From the Star Tribune, November 22, 1872.Nonetheless, the Star Tribune launched its own investigation and published the findings in January, 1873. The unnamed reporter opens by giving a thorough recap of the story, silently correcting the paper’s March report of the collision by adding Connelly’s name and changing another. Here, readers learn that the two Connelly men were brothers, and both were involved in the wreck. The surviving brother “was injured in the spine to such an extent that his mind was probably somewhat affected,” according to this follow-up story. The reporter then casts further aspersions on Connelly B by pointing out that he immigrated from a country “where the poorer classes at least believe in ghosts and goblins.” Given the , readers are asked to accept an far-from-flattering stereotype about the Irish here.

The reporter goes on to dismiss the other witnesses as the gullible prey of two engineers pulling a prank. Exactly how this was uncovered isn’t explained. The skeptical scribe next points out that, since the ghost report was first published, several curious visitors to the station house had failed to witness any ghost. However, two of them succeeded! And yet the reporter discounts those two as “evidently disposed to keep up the joke,” again with no explanation of how this was revealed. The piece ends with the implication that Connelly — earlier dubbed mentally impaired and ethnically superstitious — is attempting to cleverly dupe the railroad company into building him a new house away from the haunted spot. As far as disproving supernatural phenomena goes, this attempt to debunk is pretty easy to debunk.

Finding Where the Station House WasIn 1877, the area near Randall Station became a settlement called Clontarf, and this name remains. Presumably, the old tracks were where the current ones are, since they still connect Benson and Morris. This map shows they run parallel to Route 9, a bit to the west. I haven’t been able to determine exactly where the station house stood, but the phenomena weren’t confined to this structure. The Pioneer article says the ghost hid the trainmen’s tools, which very likely were stored near but outside the station house itself. In addition, an engineer is cited as having seen “the apparition in the night at work upon the track.” At times, it gave warning signals to the engineer and somehow slowed down the locomotive — as if it were plowing through deep snow — until it reached a certain distance beyond. Given this radius of activity, a ghost hunter might have luck investigating more than just where the house had been.

I usually like to end these “Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit” posts with other nearby attractions related to ghost hunting or railroad history in case the old ghost has retired. Unfortunately, Clontarf is a hamlet whose population ranges between 150 and 200. It has an interesting history, one intertwined with the heyday of railroading, but there’s not much there today. Let me suggest, then, you make it part of a road trip that combines Anoka, Halloween Capital of the World, with some of the haunted sites in the Twin Cities. And if you visit any of these places, please let us know about it in the comments below.

Discover more “Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit” at the page forAfter the End of the Line: Railroad Hauntings in Literature and Lore

August 13, 2023

Memories Straying Like Cows: My Unspectacular Progress in Adding to What We Know About Poe’s Final Days

The many mysteries surrounding Edgar Allan Poe’s demise have probably been baffling armchair detectives ever since the announcement of that death hit the papers in October of 1849. As I piece together my own timeline of what happened, I hoped I might stumble across something new or, at least, correct a mistake that has been repeated and repeated for decades.

Perhaps I was overestimating my ability to go all C. Auguste Dupin on this case. I’m sorry to report that, so far, I haven’t come up with anything of much importance. Yet it’s been interesting to see how those who were there changed their stories over time. Here are two examples of exactly that.

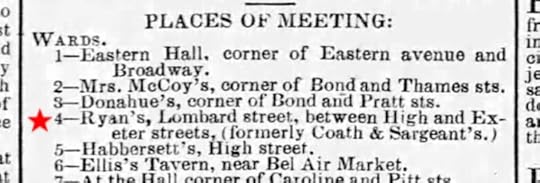

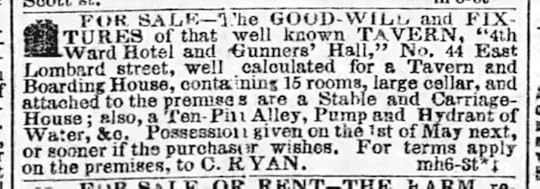

The Shifting Name of the Establishment on Lombard StreetOne of the oddest clues in the case involves Poe, typically a fastidious dresser, being discovered in shabby clothes and even shabbier mental condition. It happened on October 3, 1849, on Baltimore’s Lombard Street, between High and Exeter. A man named Joseph Walker found him there, and Poe was coherent enough to bid Walker to summon Joseph Evans Snodgrass, an editor with medical training. Walker complied, sending a message that identifies the location as “Ryan’s 4th ward polls.” This probably made sense at the time, given that there was an election going on and the spot was serving as a voting place.

But Snodgrass did not use that same name when, years later, he twice recounted the events for publication. His first memoir was published in something called Women’s Temperance Paper, reflecting Snodgrass’s devotion to the anti-alcohol movement. This source seems to be no longer extant. In January of 1856, though, the piece was reprinted in The Spiritual Telegraph, and we have a copy of this. (See page 155 or this transcript.) Snodgrass explains that, on receiving Walker’s message, he rushed to “a drinking house in Lombard-street, Baltimore.” He adds that the place had rooms available, so we seem to be talking less about a tavern and more about an inn or a hotel with a bar. Snodgrass doesn’t give us much more to help us pin down what kind of place it was.

Luckily, about a decade later, Snodgrass retold the story in Beadle’s Magazine. Here, the establishment is identified by name: “Cooth & Sergeant’s tavern in Lombard street, near High street, (Baltimore).” When I first read this, I was confused. I had seen other sources refer to it as “Ryan’s Fourth Ward Polls,” “Ryan’s inn and tavern,” and “Gunner’s Hall.” I hoped that sorting out this issue might be my small contribution to what we know.

Well, here’s what I found. Baltimore newspapers reveal that — between October, 1840, and October, 1846 — there was a political rallying/voting place called “Cooth & Sargeant’s” or “Coath & Sargeant’s” on that city’s Lombard Street. However, by 1849, this had become its former name. Instead, it was known as “Ryan’s Hotel,” “Ryan’s,” or “4th Ward Hotel and Gunners’ Hall.” (I suspect the hall was a meeting room within the hotel, one frequently used for political functions. It might also have been the barroom itself.)

It’s “Ryan’s Hotel” in The Baltimore Sun, August 17, 1849, pg. 2.

It’s “Ryan’s Hotel” in The Baltimore Sun, August 17, 1849, pg. 2. It’s “Ryan’s” and “formerly Coath & Sargeant’s” in The Baltimore Sun, November 27, 1849, pg. 2.

It’s “Ryan’s” and “formerly Coath & Sargeant’s” in The Baltimore Sun, November 27, 1849, pg. 2. It’s “4th Ward Hotel and Gunners’ Hall” in The Baltimore Sun, March 9, 1852, pg. 4.

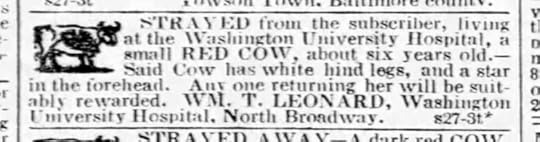

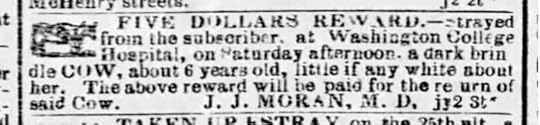

It’s “4th Ward Hotel and Gunners’ Hall” in The Baltimore Sun, March 9, 1852, pg. 4.I found a handful of inconsistent notices like these, so all I can safely deduce is that, by 1867, Snodgrass’s memory had simply wandered back to the location’s earlier name. He does the very same when he says that Poe was transported to “Washington College Hospital.” It’s a very minor error, but by that time, the facility was generally known as Washington University Hospital, as shown in an 1846 newspaper article, the 1848 notice for a stray cow shown below, and an official 1849 report.

One thing I’ve learned from investigating Poe’s death is that — at least in Baltimore — livestock strayed often enough that there were newspaper columns specifically designed to sort out adventuresome cows, horses, and hogs. This announcement appeared in The Baltimore Sun, September 27, 1848, pg. 3.The Disappearance of Reynolds

One thing I’ve learned from investigating Poe’s death is that — at least in Baltimore — livestock strayed often enough that there were newspaper columns specifically designed to sort out adventuresome cows, horses, and hogs. This announcement appeared in The Baltimore Sun, September 27, 1848, pg. 3.The Disappearance of ReynoldsAnother famous clue appeared once Poe was in his Washington University Hospital bed. In a delirious state, he referred repeatedly to someone named Reynolds. This tantalizing tidbit goes back to a letter dated November 15, 1849, roughly a month after Poe’s death. There, Dr. John Joseph Moran informs Maria Clemm, Poe’s aunt and mother-in-law, about his patient’s recurring fits. After one outburst, Poe rested, but Moran checked in on him later:

When I returned I found him in a violent delirium, resisting the efforts of two nurses to keep him in bed. This state continued until Saturday evening (he was admitted on Wednesday) when he commenced calling for one 'Reynolds', which he did through the night up to three on Sunday morning.Interestingly, the story changed when Moran recounted his experience for publication about 25 years later. In 1875, the only time he uses the name Reynolds is when he says:

I had sent for his cousin, Neilson Poe, having learned he was his relative, and a family named Reynolds, who lived in the neighborhood of the hospital. These were the only persons whose names I had heard him mention living in the city. Mr. W. N. Poe came, and the female members of Mr. Reynolds’s family.This paints a much calmer picture than Poe calling out the name over and over after being restrained by two nurses. Refashioning the story again in 1885, Moran makes no mention at all of someone named Reynolds. Now, he substitutes the name Herring where he had written Reynolds a decade earlier:

I had sent for his cousin, Mr. Nielson A. Poe, ... having learned that he was related to my patient; and also for a Mr. Herring and family, who lived in the neighborhood. [Nielson] Poe came as soon as notified and also the Misses Herring.Analyzing Moran’s wandering recollections a century later, W.T. Bandy concludes that “Reynolds was only a figment of Moran’s imagination” or, putting it more mildly, “just a mistake on Moran’s part, which he gradually corrected.” This certainly seems reasonable. And yet I really wish that “Reynolds” and “Herring” sounded more alike. Surely, Dr. Moran had several patients. Had some other delirious man shouted for Reynolds, and Moran confused them? Maybe so.

Another stray cow belonged to Poe’s attending physician, J.J. Moran. This appeared in The Baltimore Sun, July 2, 1850, pg. 3. Curiously, though this appeared after the similar notice above, it uses the earlier name: Washington College Hospital.

Another stray cow belonged to Poe’s attending physician, J.J. Moran. This appeared in The Baltimore Sun, July 2, 1850, pg. 3. Curiously, though this appeared after the similar notice above, it uses the earlier name: Washington College Hospital.Of course, a fiction writer might idly speculate that someone named Reynolds had something to hide and, so, convinced Moran to carefully and cleverly change his story. Don’t tell anyone, but creating a fictional solution to this authentic mystery is why I’m looking into it.

For the time being, though, I really haven’t shed any light on the mystery of Poe’s demise. What I discuss above only shows that memory is a funny thing, and most of us probably knew that already. My work continues, then, to find something new to say about a very old, well-trodden mystery. There’s more to ponder on my page called “The Facts in the Case of Poe’s Demise.”

— Tim