Tim Prasil's Blog, page 6

May 20, 2024

The Crowe Project Has Landed; Or, Some Other Bad Pun

My efforts to locate, list, and link Catherine Crowe’s short fiction is coming along nicely. Along with backtracking many original publications — some of them anonymous — of tales that were reprinted in collections, I found a few works that seem never to have been reprinted at all. One called “The Bear Steak” (1845), for instance, was probably published one time only. And it’s called “The Bear Steak”!

This is a wild guess, but I’m estimating that I’ve already found 90% of Crowe’s short fiction. I certainly hope that I’ll find new material to add to the list. However, my focus now is on reading what I’ve got and adding summaries and commentaries.

Mysteries So FarA few mysteries have presented themselves. Why did Crowe retitle so many — but not all — of her tales reprinted in collections, especially in Light and Darkness (1850)? Were those single-publication tales simply weaker than the others? I’ve added some comments on Crowe’s other publications, the book-length stuff, to act as context. If I go too far with these, though, do I lose my focus on her short fiction?

Importantly, how do I differentiate Crowe’s fiction from her “creative non-fiction”? For example, in “Remarkable Female Criminals–The Poisoners of the Present Century” (1847), Crowe narrates as if she’s relating real history, maybe filling in some details with her own conjecture. And maybe that’s exactly what she’s doing! But I treated this piece as fiction because it reappears in Light and Darkness, which she introduces as a volume of “tales” and “stories.” But what do I do with Ghosts and Family Legends (1859)? Here, Crowe presents herself as something of a folklorist, a transcriber of other people’s oral tales. Should we trust this, or is this a clever framing device for her own yarns? If not the latter, she almost certainly takes creative liberties with the original tales (despite her claim to the contrary). One exception in this book is “Eighth Evening,” in which Crowe purports to recount her own ghost hunt. What if this is a product of Crowe’s imagination? I hope not, but…

Suggestions?The page is developed enough that visitors can see where I’m headed. Given this, I’m very open to suggestions. Please give it a gander, and tell me what you think. It’s here: The Short Fiction of Catherine Crowe.

— Tim

May 13, 2024

A Quick Comment on Catherine Crowe’s Correct Birth/Death Dates

I’ve noticed contradictory information regarding when Catherine Crowe was born and when she died. I’m 99% sure the correct years are: 1790 and 1872. The June 22, 1872, issue of London Week News (shown below) reports that, on June 14 of that year, the author died at 82 years of age. It’s corroborated by the June 24, 1872, issue of a London publication called Births, Marriages, and Deaths (page 7), but you might need a subscription to NewspaperArchive to see that.

And, thanks to Alex Matsuo, who visited Crowe’s grave, we can see the same year-of-death and age-at-death carved in stone. You might have to squint a bit. It’s old. (The inscription is a bit easier to read here.)

That’s pretty convincing evidence. And it’s easy math to set the year Crowe was born at 1790. Still, if you go to the archives at University of Kent and look at Geoffrey Larken’s unpublished bibliography of Crowe, you’ll read about what he found in the St. George’s, Hanover Square, parish records: Catherine Crowe was born on September 20, 1790. (Thanks for the legwork regarding this, Allison!)

The Wrong YearsNonetheless, some websites give these years: 1803-1876. This one does. This one, too. Until I went back and fixed it, I had done the very same on this site. Turns out, folks have been getting it wrong for a long time. In this 1904 edition of The Night Side of Nature, the editor offers “c. 1800-1876.” This 1885 “Dictionary of Eminent Persons” says “1800-1876,” and a couple of years before that, this “Imperial Dictionary” said the same. When exactly the “1803” thing cropped up, I don’t know. It hardly matters.

The Internet is notorious for spreading misinformation, but doing so wasn’t invented in the Digital Age. Maybe this serves as a good reminder to us all — myself included — to dig up the solid evidence rather than cut-and-paste mistakes. Be cautious, not repetitious.

–Tim

May 6, 2024

The Short Fiction of Catherine Crowe: “The Lost Portrait”

When Catherine Crowe’s “The Lost Portrait” debuted in 1847, readers would have known that a “miniature” is a pocket-sized painting, usually a portrait. Some of those readers might have had a miniature or two of their own — or had admired someone else’s because they were expensive. In fact, they often came with elegant and elaborate frames, as illustrated on the bottom of this page.

Just a generation or two later, though — despite this art’s long history — miniatures had become collectables, charming relics of the bygone past. I suspect the growth and affordability of photography had much to do with this. Maybe our 21st-century equivalent is that picture of a cherished someone carried around on a smart phone.

From an 1881 issue of English Mechanic and World of Science and Art

From an 1881 issue of English Mechanic and World of Science and Art Crowe’s story hinges on a miniature that isn’t lost so much as stolen, and it becomes a fitting parallel to Nina Melloni, kidnapped granddaughter of Giuseppi Marabini. If such a thing is possible, Nina’s abduction is intended to be in the child’s best interest: she sings so beautifully that a couple of opera patrons feel they must commit the crime, resolutely ignoring any harm it might do. Crowe writes:

'It's all for her own good, you know,' answered Herbois. 'Isn't it much better that that beautiful voice should be cultivated, and that she should make her fortune, and the fortunes of her family too, than that she should languish here for the rest of her life in poverty and obscurity?''Well, perhaps it is,' answered Michelet, whose notions of right and wrong were apt to be a little confused as well as those of his friend.

One can’t but wonder if Crowe is setting up a criticism of the arrogant privilege and lack of humanity of those wealthy enough to patronize the arts. If so, the remainder of the story fails to develop such a commentary.

From Social Critique to Crime Melodrama?The remainder of the tale focuses on Giuseppi’s sad journey. His daughter, Nina’s mother, dies. His wife, Nina’s grandmother, dies. He sells his modest vineyard to go in search of the kidnapped Nina. This exhausts his finances, though, and we join him again as he wanders around England.

After a series of twists and turns — and a very crowded cast of characters — the impoverished man is accused of stealing a miniature. The missing item belongs to Sir Henry Massey, and it depicts his wife. Giuseppi is found with a miniature on his person, one carried close to his heart. He claims it’s a picture of his daughter — but, as it happens, there’s a striking resemblance between Lady Massey and the grandfather’s alleged daughter….

It’s not hard to figure out where this headed. Giuseppi is, at long last, reunited with his long lost Nina — now Lady Massey — who looks a lot like her mom. Despite the wild coincidence, there’s a traditional, melodramatic ending to the protagonist’s quest. Hold on! Who really stole the miniature that facilitated this happy reunion? Well, Crowe’s final paragraph names the true culprit, but this gives the piece an odd sense of closure. Was this a crime story all along? It opens with a kidnapping, but Herbois and Michelet are virtually forgotten by the end. It closes with a theft, but the culprit is revealed to be a minor character whose motive is left hazy. The kidnapping and theft create a nice “bookends” to the piece, but something seems off, as if Crowe wasn’t entirely sure of the story’s center.

Or does this reflect my own aesthetic expectations?

A Developing ArtCrowe was no Poe. This statement is painfully obvious, I know, but let me explain. “The Lost Portrait” gives me the impression that, when it came to writing fiction, Crowe thought like a novelist. Many characters. Multiple plot threads. Although Edgar Allan Poe didn’t always follow his own advice, he at least had his “single effect” method of crafting a short story, a narrative form that often would’ve been termed “a tale” in his era. He discusses this approach in an 1842 review of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Twice-Told Tales, saying:

A skilful literary artist has constructed a tale. If wise, he has not fashioned histhoughts to accommodate his incidents; but having conceived, with deliberate care, a certain unique or single effect to be wrought out, he then invents such incidents — he then combines such events as may best aid him in establishing this preconceived effect. If his very initial sentence tend not to the outbringing of this effect, then he has failed in his first step. In the whole composition there should be no word written, of which the tendency, direct or indirect, is not to the one pre-established design. And by such means, with such care and skill, a picture is at length painted which leaves in the mind of him who contemplates it with a kindred art, a sense of the fullest satisfaction.

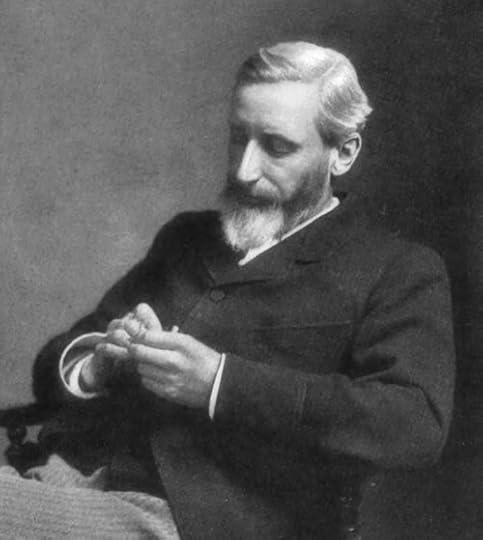

Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849)

Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849)If I understand Poe correctly, he’s saying short-story writers should narrow down what each tale is all about. Don’t start by stitching together an array of plot points (or “incidents”). Start with a “single effect,” which I take to mean a main idea, a unifying point, or possibly a one-sentence theme, such as “A family can be divided — but also united — by a criminal act.” It’s whatever the storyteller wants to linger with the reader after the tale has been told. Poe’s advice remains useful to fiction writers all these decades later, and his review is assigned reading in many Creative Writing classes.

While genres are made to be broken (or stretched or crossed or spun-on-their-heads), another useful way to focus a short story is to ask if the work-in-process is primarily, let’s say, a crime story. Is it a quest? Is it a social satire of patrons of the arts? A novel might afford the room and flexibility to weave together all three, but “tales” tend not to so roomy. That is, in Poe’s perspective. And Poe’s perspective has influenced how many readers read short stories today, so no doubt my dissatisfaction with “The Lost Portrait” is related to that.

To better appreciate Crowe’s short fiction, it can help to remember that novels were well-established by the time the “tale” became widely popular. Literacy was on the rise in the mid-1800s. So were magazines serving those readers. So were short stories printed in those magazines. Crowe was working in a narrative form that was still finding its way. As I say, she was probably thinking like a novelist — along with hundreds of other fiction writers — and this helps us understand why short stories in the era of “The Lost Portrait” might feel rather unwieldy to readers reading almost two centuries later.

Learn more aboutThe Short Fiction of Catherine Crowe.

April 30, 2024

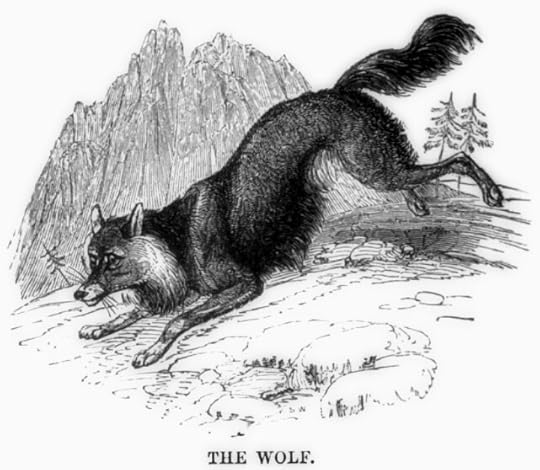

The Short Fiction of Catherine Crowe: “A Story of a Weir-Wolf”

“A Story of a Weir-Wolf” (1846) is probably one of Catherine Crowe’s best known short works because it shows up in a fair number of werewolf fiction anthologies. But there’s not really a werewolf in it — just a character falsely accused of this branch of witchcraft. You see, the story is set in 1596, and this is long before Hollywood put a vampire-spin on werewolves by making the bite of one responsible for the creation of another one. Way back when, a person chose to become a werewolf for the naughty fun of it — but it required a dark ritual and possibly some dealing with the Devil. As I say, though, that’s not what happens in Crowe’s tale.

From Thomas Bingley’s

Bible Quadrupeds

(1864).

From Thomas Bingley’s

Bible Quadrupeds

(1864).In fact, “Weir-Wolf” is better understood as a supernatural-free story. Even an alchemist, named Michael Thilouze, never gets the elixir of youth he pursues — but his Faustian attempt to do so might be seen as the root of the trouble he brings upon himself and his daughter, Francoise. To understand this, one must sort out a complicated tangle of love and resentment.

Stay with me. Victor de Vardes is “arranged” to marry Clemence de Montmorenci — but he thinks Manon Thierry is mighty fine — until he spots Francoise and these two fall in love. This makes Manon surly. Meanwhile, Jacques Renard is also “extremely in love with the alchemist’s daughter,” so he’s surly, too. Oh, and woodsy Pierre Bloui “was a suitor for Manon’s hand,” but she’s more focused on the situation between Victor and Francoise. It’s a novel’s worth of love complications packed into a short story, and I had to scribble down a chart to keep these relationships straight.

With all this jealousy panging left and right, there’s going to be trouble. Sure enough, Renard spills the beans to Count de Vardes, Victor’s father, who wants his son to marry well. And how did the lad’s affections jump from the blue-blooded Clemence over to some baseborn alchemist’s daughter? Did Francoise put the love whammy on Victor? Gossip spreads. Speculation rises. Crowe tells us:

It was asserted that [Pierre] had frequently met Victor and Francoise walking together, in remote parts of the domain; but that when they drew near, she suddenly changed herself into a wolf and ran off. It was a favourite trick of witches to transform themselves into wolves, cats, and hares, and weir-wolves were the terror of the rustics; and as just at that period there happened to be one particularly large wolf, that had almost miraculously escaped the forester's guns, she was fixed upon as the representative of the metamorphosed Francoise.Around here, Crowe tosses out the date 1588, which confused me at first because she opens by setting the story eight years later. But Crowe knew her werewolf-related lore — see, for instance, her essay “The Lycanthropist” — and 1588 is a quick allusion to a famous witch/werewolf case that occurred in Aubergne, France. This bit of folklore involves a hunter cutting off a wolf’s paw and then tracing it to a woman with a bloody stump, the latter then being tried and executed for her crime. The event was generally known in England during Crowe’s era, as shown here, here, and here, and it was almost certainly the inspiration for her “Weir-Wolf.” As we’ll see, Crowe seems to be radically retelling this tale to make a very different point.

Pierre traps the wolf, but it escapes by sacrificing its paw. Shortly afterward, Francoise is found to be one hand short! A wild coincidence? Oddly enough, yes! We learn later, though, that Francoise’s amputation is related to Michael’s efforts to attain his elusive elixir, thereby making him indirectly responsible for the father and daughter being “found guilty of abominable and devilish magic arts.” Readers know they’re innocent, but fret not — there’s an interesting twist coming.

An Interesting Twist (and Big Spoilers)A crowd has gathered to enjoy the execution of Michael and Francoise. The father and daughter stand by a pile of kindling. The executioner is about to strike a match. However, rather than rely on what some might consider a conventional hero such as Victor coming to the rescue, Crowe gives us something less “happily-ever-after” and more meaningful.

Manon, you see, has grown to regret the will ill she felt for Francoise. She hopes to make amends and settles on a plan:

This was no other than to shoot the wolf herself, and, by producing it, to prove the falsity of the accusation. For this purpose, she provided herself with a young pig, which she slung in a sack over her shoulder, and with her brother's gun on the other, and disguised in his habiliments, when the shadows of twilight fell upon the earth, the brave girl went forth into the forest on her bold enterprise alone.Indeed, at the crucial moment, “there came forward, slowly and with difficulty, pale, dishevelled, with clothes torn and stained with blood, Manon Thierry, dragging behind her a dead wolf.” Francoise and the wolf are not one and the same! The crowd cries for their pardon and release!

We’re not done, however. Crowe shows that, while one woman’s valiant effort to provide proof positive should be enough, it isn’t. It isn’t in 1596 France, and very likely, it isn’t among British readers in 1846. It takes Victor’s arrival with a pardon-on-paper from the King himself to finally release the falsely accused pair from their death sentences. Elaborating and revising the folktale about the werewolf of Aubergne, Crowe illustrates how women can be determined and powerful and capable — and rigidly dismissed by men in charge.

Learn more aboutThe Short Fiction of Catherine Crowe.

April 29, 2024

An Updated Update on Catherine Crowe

Yep, I’m updating an update.

Once upon a time, I requested help in locating a dependable portrait of Catherine Crowe (1790-1872 — or dates close to that. Sources disagree.) Crowe wrote some popular and well-reviewed novels, but my early interest in her grew from The Night Side of Nature (1848), an important collection of “true” ghost stories and accounts of other paranormal phenomena. My favorite ghost hunter, Vera Van Slyke, took this work — her beloved “Cathy” — on many a ghostly mystery. And Crowe’s own investigation of a haunted house, chronicled in Ghosts and Family Legends (1859), was interesting enough that I reprinted it in A Victorian Ghost Hunter’s Casebook. Oh — and I added Crowe to the Ghost Hunter Hall of Fame, too. That’s the main reason why I wanted a good portrait of her.

A few weeks ago, I dusted off my original request and reposted it on social media. As I explain in a recent update here, this led to a glimmer of hope and a chasm of despair. I’ve since heard from others — in my mind, I call them the Crowe Crew — and I’m led to the conclusion that I’ll probably never find that portrait. Others far better positioned than I am, by which I mean working in England, have spent years searching. They never found one. I doubt I ever will.

I still have no idea where this satirical cartoon of Catherine Crowe was published. I can’t even remember where I found it! Any help?Recognizing Her Work Rather than Her Face

I still have no idea where this satirical cartoon of Catherine Crowe was published. I can’t even remember where I found it! Any help?Recognizing Her Work Rather than Her FaceAs a result, I’ve decided to get to know Crowe in a different way. I’ve begun a bibliography of her short fiction. As far as I know, no one has done this before, and given Crowe’s importance, it’s long overdue. I’ll follow the same basic format as my Chronological Bibliography of Early Occult Detectives: a year-by-year tally of stories with as many links to online copies as I can find. I’m going to read these short stories, too, and provide summaries along with links to blog posts that explore each tale with greater depth.

This project is in the very early stages. Thinking it might provide some nice context, I’m making mention of Crowe’s novels and other book-length works, and this is nudging me toward a much more general bibliography. Maybe that’s not a bad thing.

Feel free to take a gander at what I have so far by clicking here. Suggestions below would be appreciated! If you’d rather wait until it’s further developed, here’s a very cool video about a controversial event in Crowe’s life to watch in the meantime.

–Tim

April 22, 2024

Was Dr. John Lloyd, Bishop of Swansea, the Last of the British Clerical Ghost Hunters?

In February of 1905, Welsh newspapers reported that poltergeist phenomena was manifesting in Lampeter. The haunting occurred at the residence of H.W. Howell, a solicitor and local court clerk. (In some articles, his name is spelled Howells.) There are earlier reports, but a two-part article published in the Evening Express on the 13th and the 14th is especially insightful. According to this article, Howell’s wife was the first to hear something odd: “tramping of feet and other sounds in the garret.” Next, a servant named Jane — while attending a sick eleven-year-old son named Jack — reported knocking in the wall by the bed. The skeptical Mr. Howell attributed the noise to rats, but once he returned downstairs that same night, he heard more knocking. He explains:

I rapped on the wall and said, 'Come out, old chap, let's have a look at you.' This was said in a sarcastic way, and in derision, and before I came to the last word I heard a terrific noise near the water-closet. It was exactly as if they had got into a rage and had resented my remark. The noise was tremendous.And the night of annoyances wasn’t over. More knocking rose in Jack’s room, “as if there were two rappers,” and it continued until daylight. “I was simply flabbergasted,” explains Mr. Howell, whose usual skepticism was crumbling. In hindsight, claims made by his servants and sons — claims about having heard rustling dresses and having seen both “a lady in black” and “a woman dressed in a long white robe” — now carried much more weight.

From the February 18, 1905, issue of Weekly Mail.

From the February 18, 1905, issue of Weekly Mail.Afterward, Jack was moved to the nursery, but the knocking followed him. It was then discovered that the uninvited guest could repeat whatever number of knocks it was given. It could also drum the beats of familiar tunes. This continued until Mr. Howell moved his son into his dressing-room — but then the boy’s bed started to move, the headboard banging against the wall. Mr. Howell was able to subdue it by grabbing the bed frame, but it resumed as soon as he let go.

Over the next several nights, neighbors arrived and confirmed the phenomena. A clerk from Howell’s office was among them, and this man asked if Jack was always present when the manifestations occurred. “They have knocked when Jack is not in the room,” Howell replied, “but the sound was not so perfect.” As is often the case with poltergeists, a young person seems to act as a catalyst or medium.

The Clergy Arrive (with Others)When the Right Reverend Dr. John Lloyd, Bishop of Swansea (1847-1915) arrived — with the Rev. Charles Harris, a lecturer in Theology at St. David’s College in Lampeter, at his side — the two joined a long line of clergymen called on to act as ghost hunters. In Britain, the tradition goes back at least as far as the famous Drummer of Tedworth case, which drew the attention of Joseph Glanvill (1636-1680), Chaplain to Charles the Second and Rector of Bath Abbey Church. A century later, Samuel Johnson joined the group that debunked the Cock Lane case, but the team leader was the Rev. Stephen Aldrich (?-1796), rector of St. John’s church in Clerkenwell. In Lloyd’s era, Robert Hugh Benson (1871-1914) was another clergyman with an interest in ghosts (as I discuss here). I’m not sure if Lloyd was among the last of the British ecclesiastic ghost hunters, but he certainly wasn’t the first.

The Rev. John Lloyd around 1907. Originally published by Rotary Photographic Co Ltd., this photo comes from the National Portrait Gallery.

The Rev. John Lloyd around 1907. Originally published by Rotary Photographic Co Ltd., this photo comes from the National Portrait Gallery.That two-part article goes on to describe how Lloyd and Harris — with a few others — crowded around Jack in his bed in the hope that the spirit would resume knocking. The goal was to establish communication in a fashion that had served in the Cock Lane ghost of about 150 years earlier. In Cock Lane, the alleged ghost was revealed to have manifested in order to accuse a man of murder. Things went even further in Lampeter. Once contact was made — with three knocks for yes and one for no — it was disclosed that a double murder had occurred in the house — and money remained hidden in the chimney! Strictly speaking, we are no longer in poltergeist territory. This is a spirit (or spirits) with unfinished business.

A later article in the Welsh Gazette and West Wales Advertiser offers a transcript of the conversation with the knocking spirit that divulges those secrets about murder and money. One might see the questioning as “leading the witness” in spots, for example in this exchange:

What is the matter with the house? Is there anything in the way or buried?Yes.

In what form is it? Is it money?

Yes.

If young Jack were playing a trick, as the Evening Express reporter hints in the end, it’s easy to see that he was giving the audience what they wanted.

The Welsh Gazette article includes an interview with Lloyd, and he gives his opinion of the haunting. “My mind is open,” he explains; “I could not account for the taps. … One does not like even to suggest there was any collusion, because one has no ground for it.” Perhaps the bishop departed from the Howells’ house with only questions about the case because, in his concluding remarks, he asks if

we are not taught by the Bible that there are spirits, and that they are somewhere? But as to whether they are allowed to hold communication with us is another question. There is nothing in the Bible to show that they are not allowed. The presumption may be the other way.In other words, Lloyd made no profound assessment of the visitation. He took no decisive action regarding it. He came, he heard, he left befuddled.

In the Weeks to FollowAfter a series of informal investigations such as Lloyd’s, the Howells limited who would be allowed in — and, at the same time, the manifestations seemed to quiet some. For instance, a March 2nd article in the Evening Express says, “Lampeter spook matters have cooled down considerably,” and one in The Cambrian from the following day notes that “there is an old woman now in the neighborhood who declares that years ago when in service with another family in the same house she heard similar manifestations.” The case was creeping backward instead of moving forward.

But on April 17th, the Evening Express reported that the spirit was “again busy” and the Howells had contacted the landlord about dismantling the chimney where the money was still believed to be hidden. Intriguingly, on the 22nd, the Weekly Mail said a cap and “other remains of human clothing” had been discovered under the attic floor, but permission to “open” the chimney had still not been granted.

With a grumble and a mutter, I lose the historical trail at this point. At least — for now.

Should Lloyd Be in the Ghost Hunter Hall of Fame?On the one hand, I would love to induct the first Welsh ghost hunter into that honored corridor. On the other, Lloyd’s contribution to the long legacy of this branch of paranormal investigation is rather minimal. I mentioned how he was far from the first cleric to go wraith wrangling, and this whole case has a “been there, done that” feel to it. It seems as if it should have happened 50 to 100 years earlier, right down to the “purposeful” ghost. (I discuss the recognition of purposeless ghosts in the late-1800s here and here.) Even young Jack Howell echoes Elizabeth Parsons in the Cock Lane case — and let’s toss in the Fox Sisters of Rochester of the mid-1800s. Was the boy a genuine medium or a toe-cracking prankster?

Until I find more information, say, about Lloyd taking a firmer stance on the Howell haunting or about his involvement in other ghostly matters, I’m afraid his place in the Hall of Fame must remain as a spectral visitor only. You are also invited to visit, whether corporeal or otherwise.

— Tim

April 15, 2024

How Did Victorians React to a Story of a Clergyman Getting Away with Murder?

I’ve done considerable reading for the Curated Crime Collection, focusing on “Sherlock Holmes era” fiction that makes a criminal the lead character. The earliest work in the Collection is Grant Allen’s “The Curate of Churnside,” published in 1884. Curiously, this tale remains the most startling among all I’ve read. First, Allen depicts a curate — an assistant minister in the Anglican Church — blatantly committing forgery, fraud, and finally murder.

Second, this character gets away with it!

Third, when I say the Reverend Mr. Walter Dene gets away with it, I don’t just mean he never gets apprehending by some nosy police official or by some prying private detective. I mean there’s absolutely no justice in the form of, say, the Hand of God, a Balancing of Karma, a Twist of Fate, or even so much as a Guilt-Ridden Conscience!

The boldness of this helps explain why, when the story was published in an 1884 issue of Cornhill Magazine, the finale appeared fundamentally revised — crime is punished there — in contrast to how it appears in Allen’s short story collection of the same year and another collection released in 1899. Presumably, the alternate ending in Cornhill ensured that outraged readers wouldn’t immediately cancel their subscriptions. Okay, I’m not sure magazine subscriptions were a thing at the time, but you see my point: “The Curate of Churnside” was risky stuff to publish in 1884 — and remained so for decades afterward.

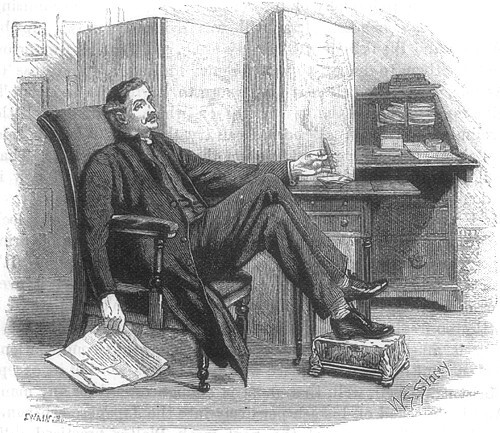

Grant Allen (1848-1899) was one interesting dude.Mixed Reviews

Grant Allen (1848-1899) was one interesting dude.Mixed ReviewsI was curious how Allen’s original readers reacted to this tale, especially the version found in Allen’s two collections, which we might assume was preferred by the author. Were they shocked? Or do I overestimate the late-Victorian demand that crime fiction end with some form of punishment for the villain? Based on critics’ mixed reactions, I suspect it depended very much on the reader.

Let’s start with a mostly negative review of “Curate,” as it appears in Allen’s Strange Stories (1884). At first, the critic for The British Quarterly Review concedes that the tale is “certainly cleverly managed.” Nonetheless, “the result can hardly be described as pleasant or inspiriting.” Adding a touch of clarification, this reviewer says that the story is one

verging perilously on the mere vulgar, sensational, penny-dreadful style, producing an almost grotesque effect which, if it were not for the horror, would be almost ludicrous.Does this critic not consider how very consistently and predictably criminals are ultimately punished in the kind of stories suggested? Isn’t this part of the appeal: to leave with the feeling that Good eventually conquers Evil? That critic’s “horror,” I suspect, actually rises from Allen defying the conventions of “vulgar, sensational, penny-dreadful style” fiction and, in so doing, implying that murderers walk among us, unbothered by their crimes. As a critic from 1923 says: “There are, I fear, many such men in the world as Walter Deane [sic].” Evoking such an uncomfortable thought is, I think, the underlying power of “Curate.”

A more positive review is found in The Literary World, and it focuses on Twelve Tales (1899), the second of Allen’s collections to include the tale of the murderous minister. Here, it’s described as “perhaps, the strongest story Mr. Allen ever wrote” and its portrayal of Dene as “a masterpiece of characterisation.” Clearly, this reviewer spoke for readers who, like myself, see the story as something artistically great and historically significant.

This illustration of Walter Dene is found in the Cornhill publication of the story.

This illustration of Walter Dene is found in the Cornhill publication of the story.On a side note, in their next issue, The Literary World mentions that a reader had pointed out the two very different endings: the one in Twelve Tales and the one in Cornhill. I find this very perturbing. You see, I wanted to be the first to publicly announce that Walter Dene — unlike that wanderer in the Robert Frost poem — managed to take both paths that diverged in a yellow wood!

A Sort of Spoof and Final ThoughtsMy research led me to a goofy, not quite spoofy, short story titled “My First Murder,” written by Angelo J. Lewis, and published in an 1885 issue of Belgravia. (It was published again the following year in The Insurance Journal: A Monthly Review of Fire and Life Insurance, which is a bit funny, given the story’s topic.) Lewis opens by loudly referring to Allen’s tale, which his narrator finds in a copy of Cornhill while waiting at a dentist’s office. The character doesn’t have time to finish reading the story — and remember this version depicts Dene’s downfall — but he reads enough to be inspired to attempt a murder of his own. After a few near-misses, the narrator learns his intended victim’s situation has changed and there’s no longer a motive to commit the terrible deed. And they all lived happily ever after — I guess. Overall, it’s a pretty forgettable piece, but it reveals that “Curate” had made some kind of mark on the crime-fiction scene.

Another point of interest regarding how readers might’ve reacted is found in the story itself, at least, the version that Allen seemed to like. The author closes by addressing those in his audience who assume someone like Dene must be forever haunted by his dark deeds: these people are “trying to read their own emotional nature into the wholly dispassionate character of Walter Dene.” Significantly, after I summarized the story to a friend of mine, she insisted that, indeed, such an uncaught killer would surely be wracked by guilt. Maybe we’re not so very different from the Victorians. We long to believe that crime doesn’t pay, and this explains the enduring popularity of detective fiction.

All this makes me wonder how readers today will react to “The Curate of Churnside.” It’s available — with the Cornhill ending following Allen’s more controversial one — in The Curate of Churnside & The African Millionaire, the first volume in the Curated Crime Collection. More information is provided here.

–Tim

April 3, 2024

I Have Good News — and Very Bad News — About My Quest to Find a Portrait of Catherine Crowe

Years ago, I wrote about my quest to find a portrait of popular novelist and ghostologist Catherine Crowe (1790-1872). She was an important, popular author — a big deal! — and it’s heartbreaking that the best image of her that’s floating around is a sketchy one. I say that in the sense that it’s a fairly general sketch and, given the difficulty of finding a reliable portrait of Crowe, it’s a dubious one. I was informed that there’s no original source documentation provided in the 1935 anthology that seems to have introduced it. Is it a comparable situation to the reprint of one of Crowe’s books that — instead of having a picture of Crowe herself on the cover — shows Grace Aguilar instead?

Apparently, this sketchy sketch first appeared in The Great Book of Thrillers, edited by H. Douglas Thomson’s anthology

The Great Book of Thrillers

(London: Odhams Press Limited, 1935).The Good News

Apparently, this sketchy sketch first appeared in The Great Book of Thrillers, edited by H. Douglas Thomson’s anthology

The Great Book of Thrillers

(London: Odhams Press Limited, 1935).The Good NewsI recently re-linked my request for help on social media, and I was rewarded with a lead on a possible portrait! A kind person and a dedicated bookworm informed me of a literary historian named Geoffrey Larken. He had collected material for a biography of Crowe, but sadly, he passed away before finding a publisher. Larken’s material was then donated to the Special Collections & Archives at the University of Kent’s Templeman Library.

According to their website, one can see a “portrait probably by Rolinda Sharples” among a variety of Crowe-related postcards and photographs. On the one hand, the artist Sharples recorded painting Crowe and her husband in 1829, a point I’ll return to below. On the other, the archive description is vague. Assuming it’s not an oil painting, is it a photograph of a painting? A photocopy of a magazine engraving of a painting? Most importantly, a portrait of whom?

Despite the mystery — and maybe because of it — it’s worth investigating. Unfortunately, I’m in the American Great Plains while Kent is a healthy hike and swim away. If anyone closer to that beguiling artifact is inspired to do some detective work and report back, I’d be very thankful.

The Very Bad NewsMy new online friend also led me to Larken’s 1972 letter to a journal titled Country Life. There, he explains that Sharples’ diary mentions her painting a portrait Crowe and her husband. Larken requests help in locating it, adding that he came up empty-handed at London’s “National Portrait Gallery and its Edinburgh equivalent.”

This request for help appears in the 20 July 1972 issue of Country Life. A subscription is needed to see it.

This request for help appears in the 20 July 1972 issue of Country Life. A subscription is needed to see it.This letter is available at the British Newspaper Archive, where the search results for “‘Catherine Crowe’ portrait” include a 1978 letter from Larken, also printed in Country Life. Frustratingly, even with a subscription, I wasn’t able to open or download the actual page linked from the search results. Maybe it doesn’t matter because an article snippet provided in those search results reveals that Larken was still “hampered by my inability to find portrait of her,” meaning Crowe, six years after his earlier letter.

In other words, a scholar in a much handier part of the globe than me, devoted many years to hunting for a good, reliable image of Crowe — and presumably failed to find this Holy Grail. Alas, this does not bode well for my own efforts.

On a more positive note, that page at Templeman Library mentions where Crowe is buried: Cheriton Road Cemetery in Folkstone. That’s something I didn’t know before!

–Tim

March 27, 2024

Lunch with Vera #2: A Nibbling Ghost

I promised to share more articles from “Lunch with Vera,” the advice column written by Vera Van Slyke late in her life. She is the same journalist whose earlier paranormal investigations are chronicled in the Vera Van Slyke Ghostly Mysteries series, available from Brom Bones Books.

Here’s an interesting request for advice, which Van Slyke almost certainly recognized to be the manifestation of a child’s imagination more than something supernatural. It appeared in the September 28, 1938, issue of the Ferness Drum, published in Ferness, Washington.

Dear Miss or Mrs. Van Slyke,

My mommy helped me write this. She does not believe me when I say there’s a ghost in our house who pinches the cookies. She thinks that it is me who pinches the cookies. However, it is not me because it is a ghost we have.

My grandma never scolded me if I pinched a cookie. My grandma, I will have you know, was very nice and sometimes pinched the cookies for me. She gave me one and ate one her own self, too. It was a secret.

I miss my grandma very much.

Please can you tell my mommy that ghosts sometimes eat the cookies? Please can you tell her that maybe the ghost is my grandma probably?

Thank you kindly,

Who Pinched the Cookies

P.S. That is not really my name. My mommy said it is how these things are done.

Dearest Who Pinched the Cookies,

First, please thank your mommy for passing this dilemma onto me. Wasn’t that very considerate of her? You can also tell her that, indeed, ghosts are believed to eat food in some counties. From Mexico to China, people hold celebrations during which families present food to their loved ones who have gone where your grandma is now. These gifts are sometimes called “offerings.”

From what you’ve reported, I agree that your nibbling ghost probably is your grandma. I wonder if your mommy and you might make your own kind of offering. I suggest that, after supper or lunch, the two of you break a single cookie in half. One half will be for you, and other half for your mother. Imagine how pleased your grandma’s spirit will be to see that you’re still enjoying a cookie while also sharing it with others. I bet this would convince her that she can go along to Heaven, knowing that you are polite and in loving hands.

Long ago, my own Granny and I enjoyed inventing tales about a moose and a mouse, who — despite being disproportionate in size — were the very best of friends. I will never forget their names: Droopymoose and Jollymouse. Like you, I suspected that my Granny visited me after she had died, and she helped me continue to conjure up adventures shared by those two animal pals. This was one of the reasons I became interested in ghosts!

Be good, little one.

A.B. Houghton’s illustration of another grandmother telling tales appeared in Robert Buchanan’s

North Coast and Other Poems

(1868).

A.B. Houghton’s illustration of another grandmother telling tales appeared in Robert Buchanan’s

North Coast and Other Poems

(1868).During the hours I’ve spent editing my great-grandaunt’s chronicles about Van Slyke, I can’t say I’ve ever seen this side of the great ghost hunter, and it’s neat to get a glimpse of what first inspired her to explore haunted sites. I’m left wondering if, deep down, Van Slyke’s ghost hunting might have been nudged by a desire to again invent stories with her grandmother.

— Tim

Click on the cover above to learn more about the Vera Van Slyke Ghostly Mysteries.

Click on the cover above to learn more about the Vera Van Slyke Ghostly Mysteries.

March 18, 2024

A Modest Proposal: Why the UK Government Should Appoint Me as Minister of Authorial Demise Records

As I gather stories for anthologies of fiction about, let’s say, mesmerist mayhem or lunar life, my research often leads to the work of British authors. To sell these anthologies in the UK, I must either secure publishing rights — a process complex enough to scare me off — or affirm that the work is in the public domain. The latter basically means it’s old enough that I can do just about whatever I want with it. Phrased differently, the work is no longer under copyright protection. Since my interests lean toward the 1800s and early 1900s anyway, almost all of the stuff I wind up anthologizing is over a century old and most of the authors have long since given up the ghost. Therefore, seeking material in the public domain makes sense.

Now, the rules of what’s in the public domain differs from country to country. For my concerns, U.S. copyright law is pretty easy: I can reprint written works originally published before 1928 because they’re 95+ years old. The UK — and a good many other countries — use a different standard, one based on the author’s death date rather than publication date. There, if the author died 70+ years ago, I’m free to reprint the material. If all goes to plan, I won’t be hearing from the Arthur Conan Doyle estate, which is kind of Britain’s answer to Disney in terms of litigating copyright.

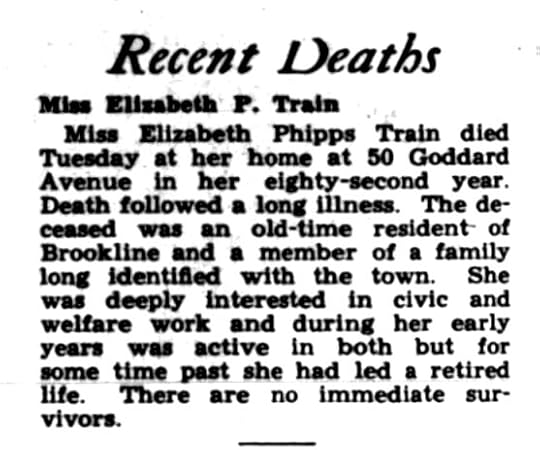

The U.S. has come to share this death + 70 years rule for more recent works. This is not great news for future anthologists because it’s loads easier to establish a publication date than a death date. For example, some months ago, I blogged about my struggle to confirm the death date of Elizabeth Phipps Train. It was a breeze to establish that her novel A Social Highwayman was first published in 1895 — it’s right there on the title page. But I wanted to combine that novel with Guy Boothby’s A Prince of Swindlers for the second volume of the Curated Crime Collection. And I wanted to sell this “two-in-one” volume in the UK (and in Canada and in a long list of other countries). So I had to establish Train’s death date.

Even though Train seems to have fallen out of the literary limelight in her later years, a clever associate of mine located solid evidence of the author’s death date. Phew! The volume is now available for purchase internationally.

The hard-to-find proof that Train died in 1940 — comfortably over 70 years ago.The Ministry of Authorial Demise Records

The hard-to-find proof that Train died in 1940 — comfortably over 70 years ago.The Ministry of Authorial Demise RecordsSince I hold the UK government largely responsible for my troubles (however unfairly), I’m proposing that they hire me to serve as the Minister of Authorial Demise Records. In this position, I would oversee providing editors specifically, and the public generally, with a reliable online database of death dates of authors. I think it could be a service handled by one or two people, and I’m flexible on the ministry designation. It could be an “Office of,” a “Department of,” or an “Agency of” thing — and I know they have something called “Trusts” over there. I’ll bow (or curtsy, if preferred) to the nomenclature suggested by someone who knows more about such things than do I, a Midwest American whose knowledge rests primarily on the Ministry of Silly Walks.

I do, however, have certain modest conditions:

There must be a fund for visiting cemeteries throughout the UK. This, of course, is to verify death dates and not — as some might unkindly speculate — because I love wandering around old graveyards and I’m dang sure the UK has some doozies.The possibility of putting the office of operations on a narrowboat must be explored. Narrowboats, not unlike bow ties, are cool! And it might be named The Authorship. It’s whimsical, you see. A little bit whimsical… Mark Ahsmann, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons This image has been fairly well checked to sidestep copyright litigation.If a floating office proves too difficult, a pub must be within the vicinity of a traditional one. A quaint and charming pub, mind you. Ideally, a quaint and charming pub with one of those The & names.There will be no “Tim Lasso” jokes. Ted came from Kansas. I’ll be coming from Oklahoma.

Completely different!

Mark Ahsmann, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons This image has been fairly well checked to sidestep copyright litigation.If a floating office proves too difficult, a pub must be within the vicinity of a traditional one. A quaint and charming pub, mind you. Ideally, a quaint and charming pub with one of those The & names.There will be no “Tim Lasso” jokes. Ted came from Kansas. I’ll be coming from Oklahoma.

Completely different!

That’s it! All manner of modest right there! I look forward to hearing from the proper authorities regarding this proposal by the end of the month. I thank you in advance.

— Tim