Tim Prasil's Blog, page 4

February 6, 2025

Lowering Old Prices and Planning New Books

I took a break from Brom Bones Books. Some of the time was devoted to crumpling newspaper, tossing on twigs, and lighting the logs for my other website, Friends of Resparking Interest in Ghostly Hearthside Tales. Some of it was spent re-thinking this website.

One decision I made regarding the latter was to lower certain prices. In fact, all three books in the Vera Van Slyke Ghostly Mysteries series are now available at $15 in the U.S. The first three books in the Curated Crime Collection are now available for the same price. Keep an eye on the Phantom Traditions Library anthologies, too. They’re headed in the same direction.

Vera Van Slyke (1868-1941) and Ludmila “Lida” Bergson (1882-1958), née Prášilová, a.k.a. Lucille Parsell

Vera Van Slyke (1868-1941) and Ludmila “Lida” Bergson (1882-1958), née Prášilová, a.k.a. Lucille ParsellMeanwhile, I have ideas for another anthology of non-fiction for my Historical Ghostlore volumes along with something pretty distinctive — something downright theatrical — to add to those spooky Phantom Traditions Library anthologies.

In other words, Brom Bones Books is back, baby!

— Tim

December 23, 2024

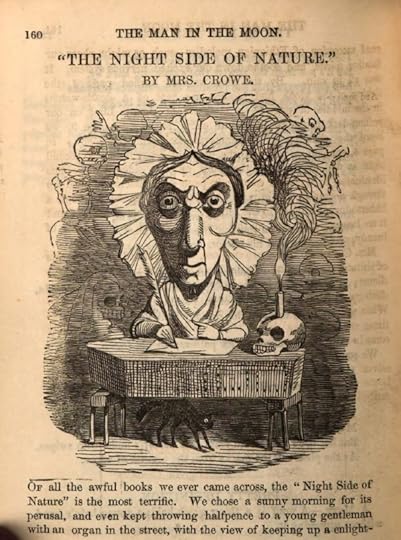

The Source of the Catherine Crowe Caricature Has Been Found

I’ve been on a mighty quest to locate a reliable portrait of once-popular author Catherine Crowe (1790-1872). It’s been so disappointing, however, that I’ve pretty much given up the struggle. Luckily, I’m not alone. There’s been a resurgence in scholarly interest in Crowe, and the findings of others is now my main source of information regarding such a portrait.

I recently heard from Emily Cline, a doctoral researcher at Queen’s University. She found the source of a caricature of Crowe. I had a digital copy of it, but it was trimmed in such as way that there was no clue of where it had been published. In other words, my copy did not look this this:

If you have access to HathiTrust, you can find a scan of the original here.

If you have access to HathiTrust, you can find a scan of the original here.As Cline explains, this is found in “vol. 3 of the comic magazine The Man in the Moon, edited by Angus B. Reach and Albert Smith, which ran from Jan. 1847 to Jun. 1849.” On the one hand, it’s far from a flattering portrait. On the other, it’s pretty great, too.

A number of scholars have contacted me regarding this unusual endeavor, and I’m grateful to each of them.

— Tim

December 20, 2024

Did Charles Hooten’s “Immaterialities; Or, Can Such Things Be?” Pave the Way for Catherine Crowe’s The Night-Side of Nature?

Catherine Crowe’s The Night-Side of Nature; Or, Ghosts and Ghost-Seers was published in 1848 — and became remarkably popular. Not surprisingly, there were plenty of reviews of it upon publication, but over time, it also served a standard reference work in other works about ghosts. It even became mentioned in both fiction and poetry! I haven’t been able to trace all of the editions, but here are a few:

London: T.C. Newby, 1848: Vol. 1 and Vol. 2. London: T.C. Newby, 1849: Vol. 1 [includes Crowe’s “Preface to the Second Edition”] and Vol. 2.New York: J.S. Redfield, 1850. 1853.London: G. Routlege and Co., 1852 [includes Crowe’s “Preface to the Third Edition”]. 1857 [designated “New Edition”]. 1866. 1882. 1904.New York: W.J. Widdleton, 1868.Philadelphia: Henry T. Coates, 1901 [“New Edition”].I recently came upon a magazine series, written by Charles Hooten and published in 1846, that might have served as inspiration for Crowe. If not inspiration, it shows that Crowe was a part of an emerging trend, one of interweaving allegedly true ghost reports with argument that such phenomena should be approached with an open mind instead of the automatic skepticism that had dominated the decades before.

Hooten’s series is titled “Immaterialities; Or, Can Such Things Be?” It was published in Ainsworth’s Magazine:

“Chap. I,” Ainsworth’s 9 (1846) pp. 206-213;“Chap. II,” Ainsworth’s 9 (1846) pp. 297-303;“Chap. III,” Ainsworth’s 9 (1846) pp. 449-454; and“Concluding Chapter,” Ainsworth’s 10 (1846) pp. 49-54.Hooten opens by bemoaning the loss of enchantment to the “utilitarianism and matter-of-fact tendency of the times.” With an odd streak of nostalgia for more fearful times, he laments:

A man may watch in a church, or a graveyard, every hour of the night, and see no ghost, because every body knows there are no ghosts to be seen. The magic has departed from midnight, and the bones of the dead are now scarcely less dreaded by man or maid than are those similar relics of animal mortality which grin upon a dish in the larder. One cannot even hire a haunted house at any lower rent than a similar house that is not haunted....This kind of expository prose frames a series of ghost tales or, perhaps I should say, weird ones. Many of the narratives involve events that took place centuries earlier. His first, for instance, is taken from the letters of “James Howell, one of the clerks of the Privy Council, in Charles the First’s reign,” so this must have been in the first half of the 1600s. Granted, it’s a neat story — but it’s an old one.

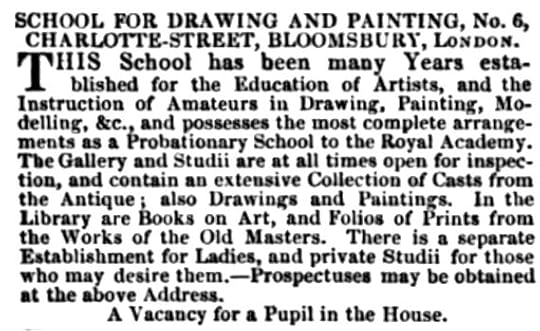

The next story is set in dated 1701. Not much better. But the third is said to have happened in 1829, so within the living memories of most of Hooten’s readers. There’s mention of “the celebrated establishment for drawing in Charlotte Street, Bloomsbury,” in London, and according to this advertisement in an 1841 Art magazine, at least that part of the story is true.

From the September 1, 1841, issue of The Art Union.

From the September 1, 1841, issue of The Art Union.Unfortunately, some of Hooten’s arguments come off as rather silly and “stretched.” For instance, he suggests that sustaining a belief in ghosts can provide a check on immoral — or, at least, naughty — behavior:

Who dare venture to say what crimes have not been prevented by the salutary and healthy belief in ghosts? What mischievous kissings between amorous footmen and susceptible maids in obscure parts of mysterious old manor houses, have not been happily averted by the dread of some too shapely ancestorial shadow, or the fearful sound of a long-departed knight tramping unquietly along the darkened corridor?No snogging amongst the staff, if you please!

At the same time, Hooten admits that “we are totally in the dark” regarding ghosts, and so he shares his stories to provide evidence without drawing a grand theory from it. This is probably the real value of the piece today. The four chapters serve as a wonderful source of “true” tales about hauntings from the Victorian and pre-Victorian period.

Take, for instance, the tale found in the last chapter. It’s among the very earliest I’ve found addressing the haunted spot where Elizabeth Shepherd was murdered in 1817. A stone monument was placed at the spot, one that’s still there and still evokes ghost stories! I’m always fascinated when such haunted sites persist across the centuries. Rarely do the manifestations remain consistent, which suggests specters like to shake it up from time to time.

Those interested in Victorian ghost stories might enjoy wandering through Hooten’s long article.

— Tim

November 20, 2024

Oh, Yes, Windows Will Rattle! An Update on Season 3 of Tales Told When the Windows Rattle

Thunder and bees! I didn’t think it was several months ago that I posted a post about the difficulties I had recording a third season of Tales Told When the Windows Rattle. But it was. I end that posted post by saying I’d let you know if anything develops. And it has.

There I was, a day or two ago, sitting in my quieter recording space when it suddenly hit me: I have enough material to put together what I think will be a very interesting Season Three. As were Seasons One and Two, this would be comprised of ten episodes. I would also continue with reading tales intended to chill and thill while alternating between shots of a hearthside’s view of a fire and a window’s view of rotten weather.

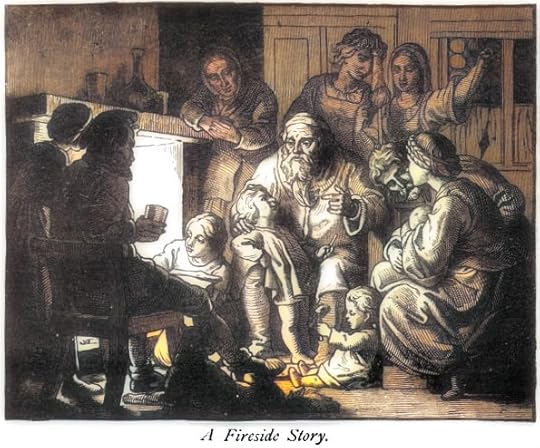

In addition, this material works very nicely with the long tradition of spooky tales told fireside during wintry or rainy weather. Reviving this faded custom has served as the foundational aesthetic of Tales Told all along.

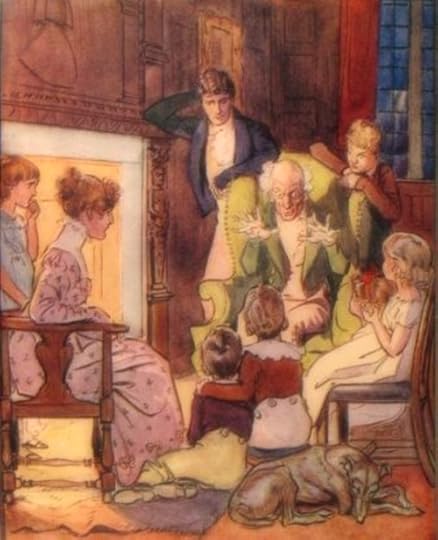

“Ghost Stories Round the Christmas Fire,” by H.M. Brock, The Christmas Tree, by Charles Dickens, (Hodder & Stoughton, c. 1911).The Same But Different

“Ghost Stories Round the Christmas Fire,” by H.M. Brock, The Christmas Tree, by Charles Dickens, (Hodder & Stoughton, c. 1911).The Same But DifferentSeason Three will take things in a new direction, too. Up to now, Tales Told has mostly featured my readings of short works of fiction, stories chosen from the various volumes published here at Brom Bones Books. Lately, though, I’ve been collecting non-fiction ghost stories — narratives presented as true — published during the Victorian period. My findings will form the basis of the next season.

In other words, instead of scary stories crafted by the likes of Poe, Dickens, Blackwood, or Prasil, you’ll hear stories by — well, almost certainly by no one you’ve ever heard of before. But there’s a distinctive appeal to chronicles purported to describe entirely genuine ghostly encounters.

And I’m not pulling from the books I’ve written or edited. This means no annoying sales pitch at the end of every episode. This means shorter episodes, too, though I’ll combine two or three stories for each. I’ll also post them daily, from December 15th to the 24th, instead of weekly as I’ve done in the past.

I’ll notify you when the videos start to become available. Until then, please consider subscribing to the Tales Told YouTube channel.

— Tim

November 14, 2024

The Scarlet Pencil: Victorian Anthologies of “True” Ghost Stories; Or, Beware of Anthologists

For a project that I’ll elaborate upon in the near future, I went searching for 25 allegedly true ghost stories. I wanted them all to have been published in the Victoria era and to involve a manifestation occurring in the same era. I’m pleased to say I found them, but — early in the process — I decided against using books that offer readers a handy collection of such stories, despite how much these would have made things easier for me.

One reason I made this decision is those anthologies are easy to find. (I list and link some of them below.) I wanted to recover some stories that aren’t so easily accessed, thereby adding to the body of literature featuring “true” Victorian ghost stories — if “body” and “ghost” belong in the same sentence.

Another reason is I stumbled upon one flagrant rewriting of an original story in anthology. This got me thinking about how the other anthologists might have been, if not revising the stories outright, at least selecting those that suited their purpose. Before explaining what I mean, let’s take a look at some sample anthologies.

Five Such AnthologiesI know there are more out there, but here are the primary anthologies I have in mind here. I tack on some notes about each anthologist’s bias.

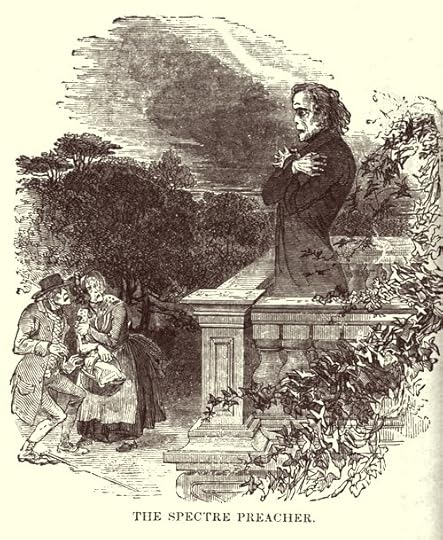

The Night Side of Nature; or, Ghosts and Ghost Seers, Vol. 1 and Vol. 2., edited by Catherine Crowe (London: T.C. Newby, 1848). Crowe is part of a “push against” decades of skepticism that dismissed the reality of ghosts, and her choice of material almost certainly was shaped by this stance.Remarkable Apparitions and Ghost-Stories, edited by Clarence S. Day (New York: Wilson, 1848). Below, I discuss how Day’s radical revision of one ghost story got me thinking about anthologists’ biases and why I should be wary of the kind of books found in this list.Real Ghost Stories, edited by W.T. Stead (London: Grant Richard, 1891). Like Crowe, Stead was a believer in ghosts, and his choices of material was quite likely influenced by this.The Ghost World, edited by T.F. Thiselton Dyer (London: Ward and Downey, 1893). Thiselton Dyer was a folklorist, and I suspect his material was chosen — not to promote a belief in ghosts — but to illustrate specific elements of that widespread belief.The Book of Dreams and Ghosts, edited by Andrew Lang (London: Longmans, Green, 1899). Lang was famous for remaining neutral regarding the reality of ghosts (though still fascinated by the topic), so his selection of material might have been fairly balanced. He fits nicely beside Thiselton Dyer on the bookshelf. Despite the fact that Day appears to have fiddled with the original stories, his Remarkable Apparitions and Ghost-Stories anthology includes some pretty cool illustrations!Day Shines a Light

Despite the fact that Day appears to have fiddled with the original stories, his Remarkable Apparitions and Ghost-Stories anthology includes some pretty cool illustrations!Day Shines a LightIt was Clarence S. Day who really convinced me to find my 25 Victorian ghost stories without the assistance of an anthologist. I mentioned that I was seeking experiences that had happened in the Victorian period, and a lot of Day’s stories are set long before this. But then I spotted one that opens: “Some years ago…”

Day titles this anecdote “How the Ghost of a Young Woman appeared to a Clergyman who had seduced her.” Bit of a spoiler, that! Indeed, in the end, we learn that the clergyman — specified as Roman Catholic — was haunted by unconfessed guilt:

The phantom-lady, in all her visits to others, kept silence; no one but the clergyman ever heard her speak; perhaps, because no one else had the courage to speak to her. But what she said to him, he could never be induced to tell. So stood the matter when we were brought into contact with him. From other sources we have learned that he often passed his night in the open air, to evade the dreaded visitation....Finally, on his death-bed, he confessed the apparition which had haunted him so long and so painfully, was that of a young girl whom he had seduced many years before, and who had died of a broken heart, because he had refused to renounce holy orders and marry her.

One might wonder how the narrator had access to this confession, something generally protected by clergy-penitent privilege. But, hey, let’s ignore that!

A little digging showed me that Day probably copied the story from an issue of Dublin University Magazine that had been published a year earlier. Dublin. Ireland. A predominantly Catholic population. Not surprisingly, the story of the priest here ends very differently. The bulk of the story is the same, but the earlier version concludes this way:

From other sources we have learned that he often passes his night in the open air, to evade the dreaded visitation.... At such times, his village-parishioners often lie awake till the dawn, listening with a heart-clutching fear to the unearthly tones which his voice and his guitar conspire to send forth into the shuddering night.No deathbed confession here. The secret remains secret. And there’s something both unresolved and unnerving in that.

Who Changed What?One might argue that the Dublin University Magazine article carries the altered ending. However, in that article, the anonymous author introduces the story as one gleaned while personally traveling through Germany. This might be pure fiction, I suppose, but it certainly feels closer to the source than Day’s presentation of it.

Furthermore, Day, an American, was compiling his work when the U.S. was experiencing a wave of staunch anti-Catholic and anti-German/Irish immigration. It’s my strong hunch that Day found the Dublin University Magazine article and reworked the finale — maybe to provide greater resolution — but also to reinforce the socio-political leanings of many American readers in the mid-1800s. I’ll never know for sure. But the two endings of the single story serve as a very loud example of how an anthologist’s decisions can skew an anthology. If it hadn’t have been for you meddling editors!

Anthologist bias is not something I’ve worried about in the past. Maybe it’s time I do. At least, I should keep a sharper eye on it, and do my best to trace an anthology’s selections to their original sources.

— Tim

(Posts identified as “The Scarlet Pencil” chronicle my meandering through the misty and mysterious quagmire of editing books.)

Victorian Anthologies of “True” Ghost Stories; Or, Beware of Anthologists

For a project that I’ll elaborate upon in the near future, I went searching for 25 allegedly true ghost stories. I wanted them all to have been published in the Victoria era and to involve a manifestation occurring in the same era. I’m pleased to say I found them, but — early in the process — I decided against using books that offer readers a handy collection of such stories, despite how much these would have made things easier for me.

One reason I made this decision is those anthologies are easy to find. (I list and link some of them below.) I wanted to recover some stories that aren’t so easily accessed, thereby adding to the body of literature featuring “true” Victorian ghost stories — if “body” and “ghost” belong in the same sentence.

Another reason is I stumbled upon one flagrant rewriting of an original story in anthology. This got me thinking about how the other anthologists might have been, if not revising the stories outright, at least selecting those that suited their purpose. Before explaining what I mean, let’s take a look at some sample anthologies.

Five Such AnthologiesI know there are more out there, but here are the primary anthologies I have in mind here. I tack on some notes about each anthologist’s bias.

The Night Side of Nature; or, Ghosts and Ghost Seers, Vol. 1 and Vol. 2., edited by Catherine Crowe (London: T.C. Newby, 1848). Crowe is part of a “push against” decades of skepticism that dismissed the reality of ghosts, and her choice of material almost certainly was shaped by this stance.Remarkable Apparitions and Ghost-Stories, edited by Clarence S. Day (New York: Wilson, 1848). Below, I discuss how Day’s radical revision of one ghost story got me thinking about anthologists’ biases and why I should be wary of the kind of books found in this list.Real Ghost Stories, edited by W.T. Stead (London: Grant Richard, 1891). Like Crowe, Stead was a believer in ghosts, and his choices of material was quite likely influenced by this.The Ghost World, edited by T.F. Thiselton Dyer (London: Ward and Downey, 1893). Thiselton Dyer was a folklorist, and I suspect his material was chosen — not to promote a belief in ghosts — but to illustrate specific elements of that widespread belief.The Book of Dreams and Ghosts, edited by Andrew Lang (London: Longmans, Green, 1899). Lang was famous for remaining neutral regarding the reality of ghosts (though still fascinated by the topic), so his selection of material might have been fairly balanced. He fits nicely beside Thiselton Dyer on the bookshelf. Despite the fact that Day appears to have fiddled with the original stories, his Remarkable Apparitions and Ghost-Stories anthology includes some pretty cool illustrations!Day Shines a Light

Despite the fact that Day appears to have fiddled with the original stories, his Remarkable Apparitions and Ghost-Stories anthology includes some pretty cool illustrations!Day Shines a LightIt was Clarence S. Day who really convinced me to find my 25 Victorian ghost stories without the assistance of an anthologist. I mentioned that I was seeking experiences that had happened in the Victorian period, and a lot of Day’s stories are set long before this. But then I spotted one that opens: “Some years ago…”

Day titles this anecdote “How the Ghost of a Young Woman appeared to a Clergyman who had seduced her.” Bit of a spoiler, that! Indeed, in the end, we learn that the clergyman — specified as Roman Catholic — was haunted by unconfessed guilt:

The phantom-lady, in all her visits to others, kept silence; no one but the clergyman ever heard her speak; perhaps, because no one else had the courage to speak to her. But what she said to him, he could never be induced to tell. So stood the matter when we were brought into contact with him. From other sources we have learned that he often passed his night in the open air, to evade the dreaded visitation....Finally, on his death-bed, he confessed the apparition which had haunted him so long and so painfully, was that of a young girl whom he had seduced many years before, and who had died of a broken heart, because he had refused to renounce holy orders and marry her.

One might wonder how the narrator had access to this confession, something generally protected by clergy-penitent privilege. But, hey, let’s ignore that!

A little digging showed me that Day probably copied the story from an issue of Dublin University Magazine that had been published a year earlier. Dublin. Ireland. A predominantly Catholic population. Not surprisingly, the story of the priest here ends very differently. The bulk of the story is the same, but the earlier version concludes this way:

From other sources we have learned that he often passes his night in the open air, to evade the dreaded visitation.... At such times, his village-parishioners often lie awake till the dawn, listening with a heart-clutching fear to the unearthly tones which his voice and his guitar conspire to send forth into the shuddering night.No deathbed confession here. The secret remains secret. And there’s something both unresolved and unnerving in that.

Who Changed What?One might argue that the Dublin University Magazine article carries the altered ending. However, in that article, the anonymous author introduces the story as one gleaned while personally traveling through Germany. This might be pure fiction, I suppose, but it certainly feels closer to the source than Day’s presentation of it.

Furthermore, Day, an American, was compiling his work when the U.S. was experiencing a wave of staunch anti-Catholic and anti-German/Irish immigration. It’s my strong hunch that Day found the Dublin University Magazine article and reworked the finale — maybe to provide greater resolution — but also to reinforce the socio-political leanings of many American readers in the mid-1800s. I’ll never know for sure. But the two endings of the single story serve as a very loud example of how an anthologist’s decisions can skew an anthology. If it hadn’t have been for you meddling editors!

Anthologist bias is not something I’ve worried about in the past. Maybe it’s time I do. At least, I should keep a sharper eye on it, and do my best to trace an anthology’s selections to their original sources.

— Tim

October 30, 2024

The Complete Crimes of Romney Pringle Is Available, and the Curated Crime Collection Enters Its Second Phase

The fourth volume in the Curated Crime Collection is available for sale. Titled The Complete Crimes of Romney Pringle, it offers all of Clifford Ashdown’s tales regarding their master criminal.

Clifford Ashdown was a pen name used by two medical doctors, both with experience in the penal system. In fact, it’s entirely likely that R. Austin Freeman and John James Pitcairn met while serving at London’s Holloway Prison before collaborating on writing projects. Certainly, their individual experiences there would have given them insight into criminal life, and the final chapters of Complete Crimes are set in an unnamed prison.

Prominent among Romney Pringle’s criminal talents is his skill at disguise.

Prominent among Romney Pringle’s criminal talents is his skill at disguise.That said, Pringle is far from an ordinary criminal. Freeman and Pitcairn apparently sensed that readers might find little interest in a thief like those they met at Holloway. Instead, they created one whose crimes are not motivated by financial need, whose life is filled with high adventure, and whose sense of right and wrong at least flirts with that of Robin Hood. Regarding the latter, Pringle often targets other criminals, and in one case, even uses his criminal skills to rescue a victim of foul play. Nonetheless, he also somehow seems to personally benefit from whatever unlawful opportunity comes his way.

Pringle is an excellent example of how authors responded to the wild popularity of Sherlock Holmes — not by creating yet another detective character, as so many of their colleagues did — but by introducing a villain character engaging enough to sustain, in this case, a series of twelve short stories. Keeping this storytelling challenge in mind has been vital to my selection process as I proceed through the nine-volume Curated Crime Collection. The criminals don’t have to likeable, mind you. But they do have to be entrancing.

And The Complete Crimes of Romney Pringle starts the second phase of these releases: The Crime Wave Crests. The next book, which will be released soon, is a “partners in crime” volume combining Josiah Flynt’s The Rise of Ruderick Clowd and Miriam Michelson’s In the Bishop’s Carriage. That will be followed by The Complete Crimes of the Motor Pirate, which brings together a novel and its sequel featuring G. Sidney Paternoster’s title super-villain.

Then I begin work on the final three volumes, which I’m designating The Crime Wave Crashes. For now, though, let me nudge you take a look at the trio of works comprising the first phase: The Crime Wave Rises.

— Tim

October 23, 2024

Introducing Friends for Rekindling Interest in Ghostly Hearthside Tales, a.k.a. F.R.I.G.H.T.

A while ago, I urged visitors to give me a stern glance of disapproval if I failed to blog more about the centuries-old tradition of sharing spooky stories by a winter fire. If you want to be persnickety about it — and no one should pass up the chance to be persnickety about something — the tradition works just as well around an autumn fire on a blustery evening or even a spring fire on a bone-drenching night. This custom is older than Shakespeare, drifted toward becoming a Christmas thing before Dickens pounced on it, and seems to have faded by the 1900s.

There’s been a here-and-there effort to resurrect the charming yet chilling tradition. For instance, the BBC continues its Yuletide series of holiday horrors. I’ve heard from a father who reads a ghost story aloud to his family each year near Christmastime. There are quite a few YouTube channels that do the reading for you while supplying the cozy fire. I’m a bit Prasil — er, uhm — partial to Tales Told When the Windows Rattle, though the guy who runs it really needs to update it with new stuff.

And there are digital copies of books that were marketed to Victorians as befitting the tradition, such as Fireside Stories for Winter Evenings, but I’ve been struggling to find good ghost or ghostly stories within them.

In other words, there are various resources that could help those who wish to reignite the custom. But, so far as I know, there’s no central website or other locus where such people can find these useful materials or news about what’s being tried.

Enter: F.R.I.G.H.T.So I’ve given myself a mission: be the singed spirit you want to see in the world! I’ve already started this with that YouTube channel linked above and with my Fireside Storytelling Descriptions & Depictions TARDIS page.

But I’ve now started work on what I’m calling Friends for Rekindling Interest in Ghostly Hearthside Tales. Eventually, I hope it’ll be a website all on its own. For now, I’ll offer resources here at BromBonesBooks.com.

And I’m starting with instructions/materials for Holding Your Own Ghostly Hearthside Party. My plan is to:

Locate thirty “real” ghost stories from diverse Victorian sources. These should be fairly short and have something of the feel of tales told orally.Cut-and-paste these narratives into easily read .pdf files, which will then be posted here. Here’s an example. And here’s another example. Since I’m excitable, yet another one. I’ve gently modernized and otherwise tweaked the texts to, I hope, make them more reader-friendly.Explain how distributing these among guests gathered round a fire — be it real or one of the many available on YouTube — can create a quaint and curious evening. With luck, it’ll urge any quaint and curious ghosts in your vicinity to snuggle up next to you or one of your guests.I’ve already invited several friends to act as guinea pigs and to improve upon or offer alternatives to such an activity, though that gathering won’t happen until mid-December. In the meantime, please feel free to share ideas on making the future F.R.I.G.H.T. website a success.

— Tim

October 9, 2024

Washington Irving Is My Hero, and Not Just for Adding to Two of My Lists with a Single Passage

Washington Irving (1783-1859)I have amused myself, during a snowy day in the country, by rendering ["The Grand Prior of Minorca: A Veritable Ghost Story"] roughly into English, for the entertainment of a youthful circle round the Christmas fire. It was well-received by my auditors, who, however, are rather easily pleased. One proof of its merits is, that it sent some of the youngest of them quaking to their beds, and gave them very fearful dreams. Hoping that it may have the same effect on your ghost-hunting readers, I offer it, Mr. Editor, for insertion in your Magazine.-- Washington Irving (writing as Geoffrey Crayon), 1840

Washington Irving (1783-1859)I have amused myself, during a snowy day in the country, by rendering ["The Grand Prior of Minorca: A Veritable Ghost Story"] roughly into English, for the entertainment of a youthful circle round the Christmas fire. It was well-received by my auditors, who, however, are rather easily pleased. One proof of its merits is, that it sent some of the youngest of them quaking to their beds, and gave them very fearful dreams. Hoping that it may have the same effect on your ghost-hunting readers, I offer it, Mr. Editor, for insertion in your Magazine.-- Washington Irving (writing as Geoffrey Crayon), 1840This week, with this a single passage, Washington Irving lengthened two of my TARDIS pages. (On this site, TARDIS stands for Trusted Archival Research Documents in Sequence. I’ve heard tell that, elsewhere, the same acronym indicates a not entirely dissimilar mode of time-travel.)

Mr. Irving’s Second Contribution to the First OneThe first page is the Fireside Storytelling Descriptions & Depictions TARDIS. This page features written and visual “snapshots” of the centuries-old tradition of telling spooky stories by the hearth on a stormy evening. Irving was already in this gallery, under 1819, with a passage taken from “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” I’ve now added this one, too.

On a side note, several people are engaged in reigniting this custom, and my own Tales Told When the Windows Rattle series of readings is part of that. Come to think of it, our widespread effort is something I should blog about more often. If I don’t, poke me in the shoulder, cross your arms, and give me a disappointed look. Clear your throat and tap your foot, too, if it comes to that.

“A Ghost Story,” by George Thomas, from Illustrated London News 45 (Dec., 1864) pp. 44-45. Please spot the cat about to give everyone there a terrible fright. Mr. Irving’s First Contribution to the Other One

“A Ghost Story,” by George Thomas, from Illustrated London News 45 (Dec., 1864) pp. 44-45. Please spot the cat about to give everyone there a terrible fright. Mr. Irving’s First Contribution to the Other OneI added part of the very same passage to The Rise of the Term “Ghost Hunt” TARDIS. This list covers roughly a half-century of, well, pretty much anything that shows how people used “ghost hunt,” “ghost hunter(s),” and “ghost hunting” long before it became a familiar part of the paranormal investigation lingo we know today. In fact, I traced things back to the late 1700s/early 1800s. I didn’t know quite when to end this list, though, and Irving’s contribution strikes me as an excellent place to do just that. By 1840, the term “ghost hunt” had risen — even Washington Irving was using it!

The second use of the term “ghost-hunting” in Elizabeth Gunning’s 1794 novel, The Packet.What If There’s More?

The second use of the term “ghost-hunting” in Elizabeth Gunning’s 1794 novel, The Packet.What If There’s More?I can’t help but wonder what else Irving wrote that could go on, say, my Chronological Bibliography of Early Occult Detectives. In Tim Burton’s 1999 Sleepy Hollow, Ichabod Crane acts as an occult detective — but the “same” character decidedly does not in Irving’s 1820 work. I suspect many folks who have never read the original would be stunned by the differences between it and almost all of the film or television adaptations. Irving’s Ichabod is not a very likeable guy.

Or might the great author qualify for The Ghost Hunter Hall of Fame? If anyone knows if Irving did indeed go on something like a ghost hunt, please let me know! His fictional character Dolph Heyliger investigates a house said to be haunted in a twist-filled tale of the same name. But this ain’t the same fish as Charles Dickens wandering the streets of Cheshunt to find a house said to be haunted or Arthur Conan Doyle reinventing what happened during his investigation of a Charmouth poltergeist. Dickens and Conan Doyle are inducted into the Hall of Fame. But I have a hunch that, if Irving ever had gone on a ghost hunt, I’d have stumbled across it by now.

That said, I only very recently stumbled across the passage on the far end of this post. Who knows? Until something happens, feel free to visit

The Fireside Storytelling Descriptions & Depictions TARDIS,The Rise of the Term “Ghost Hunt” TARDIS,The Chronological Bibliography of Early Occult Detectives, orThe Ghost Hunter Hall of Fame.— Tim

September 25, 2024

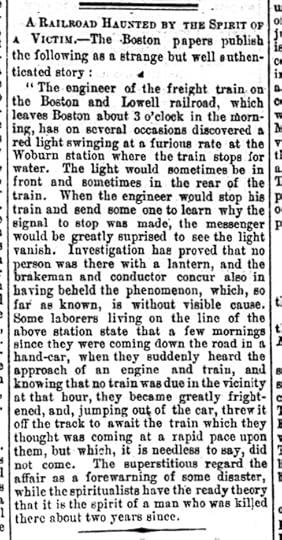

Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit: A Watering Station in Woburn, Massachusetts

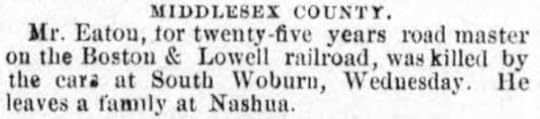

Flip to page 24 of Ashcroft’s Railway Directory for 1866, and you’ll see that the roadmaster for the Boston & Lowell and Nashua & Lowell Railroad is listed as J. B. Eaton. The entry also shows that Eaton’s residence was Nashua, New Hampshire, so it’s not surprising that that’s where he was buried. Regarding his death, on October 10th of the following year, Eaton was killed on the job while down near Woburn, Massachusetts.

From the October 11, 1867, issue of the Worcester [Massachusetts] Daily Spy.

From the October 11, 1867, issue of the Worcester [Massachusetts] Daily Spy. Another notice clarifies that Eaton died by “slipping from a platform on to the track,” where he was presumably hit by passing cars. Perhaps the best explanation of how a seasoned railroad employee can fall prey to such a work accident appeared a couple of days later in Washington D.C.’s Evening Star. It seems Eaton might have sneezed or coughed, causing his false teeth to fly out of his mouth. At least, “a set of false teeth were found in the clenched hand of the deceased, and it is highly probably the fall was principally owing to a sudden movement to recover them….”

The death notice shown above specifies “South Woburn,” and that’s now called Winchester. But the name change happened in 1849, so it’s odd that the 1867 notice still says “South Woburn.” Luckily, another notice of his death specifies “Woburn W. Place,” which I take to mean “Woburn Watering Place,” (elsewhere noted as “Woburn Water’g pl.”). I’ll explain why this is important in a moment.

If nothing else, this provides a distinctive backstory to a railroad haunting that was chronicled in newspapers in early 1870. But Eaton’s spirit isn’t the only candidate to explain the haunting. A list of accidents on the Boston and Lowell line appears in an 1867 report on railroad corporations, and Eaton’s death is accompanied by another possibility: “August 12. — Sumner Clark, while walking on the track near East Woburn, was struck by a train, receiving injuries which caused his death.” However, Eaton’s professional dedication to railroad safety — and the probability that his accident occurred at Woburn Watering Place — make him a better fit for the specific manifestations of the haunting.

The 1870 Railroad HauntingWhat I mean becomes clearer in an 1870 report that apparently began in Boston, Massachusetts, but that travelled as far as newspapers in the UK and London’s The Spiritual Magazine.

From the February 2, 1870, issue of The Daily Dispatch, a paper published in Richmond, Virginia.

From the February 2, 1870, issue of The Daily Dispatch, a paper published in Richmond, Virginia.It’s an especially weird case in that there are two distinctive manifestations reported: the sighting of an inexplicable swinging red light and the sound of a train that never appears. It’s also interesting that two theories of the haunting are posited: a sign of future danger, or a spirit of past tragedy. I haven’t explored the forward-looking possibility, and Eaton’s death is the best evidence I’ve found to support the ghost theory.

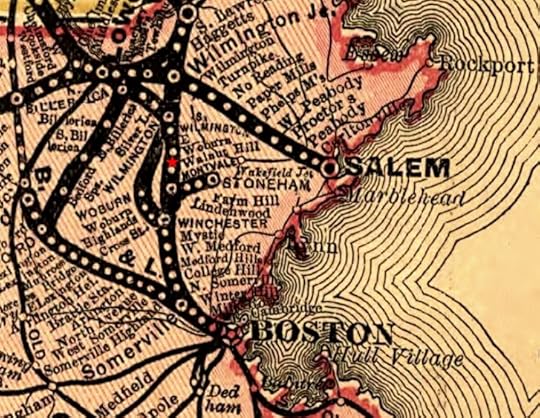

Finding the Station TodayThis case required me to sort out a tangle of names and name-changes. According to an 1867 Boston & Lowell schedule, a northbound passenger can leave Boston and, after Winchester, get off at 1) East Woburn, 2) “Woburn water’g pl.,” or 3) North Woburn, the train continuing on to Wilmington. There’s also an option to take the Woburn branch and, after Winchester, detrain at 1) Richardson’s, 2) Horn Pond, or 3) Woburn Centre. However, a circa-1890 map (see below) shows new names for the main-branch stops between Winchester and Wilmington: Walnut Hill and then E. Woburn. (I have a hunch that the latter was a mistake: “E Woburn” should have been marked as North Woburn.) And here the Woburn branch lets you stop at Cross Street or Woburn Highlands before “WOBURN.”

I put a red star on this detail of a map of the Boston & Lowell Railroad (circa 1890) to indicate the probable spot where the spectral red light was observed.

I put a red star on this detail of a map of the Boston & Lowell Railroad (circa 1890) to indicate the probable spot where the spectral red light was observed.Now, the ghost report is very vague about where the phantom train was heard. I think that might be a lost cause. We can do much better with the spectral red light, though, because it was observed “where the train stops for water.” There’s that stop marked as such on the 1867 schedule, and according to a 1918 history of the Boston & Lowell, “For many years the station now called Walnut Hill was known as Woburn Watering Station.” Walnut Hill is marked on the 1890 map, and it remains an eastern neighborhood of Woburn today. An interested ghost hunter might use this location to carefully explore the tracks that still run — and are still used — between Winchester and Wilmington. They run parallel to and east of Wildwood Avenue.

As I say, this is very likely where roadmaster James Bradford Eaton lost his life while scrambling to retrieve his false teeth. This is very likely where, a bit more than two years later, a ghostly red light was reported to swing “at a furious rate.” Does this phenomena — or the sounds of a phantom train — still linger? Please let us know in the comments if you do any investigation. And if you’re disappointed there, consider exploring nearby Horn Pond, reputed to be the site of a variety of paranormal manifestations.

Discover more “Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit” at the page forAfter the End of the Line: Railroad Hauntings in Literature and Lore.