Tim Prasil's Blog, page 3

July 9, 2025

Haunted Ancestral Homes 4: The Terror of Glamis Castle

This article comes from the February 16, 1892, issue of the Brechin Herald.

Glamis Castle not only still stands — you can plan a tour and attend a variety of events there. It continues to attract the attention of paranormal enthusiasts.

5: The Ghostly Visitations of Calverley HallIf you’re intrigued by Victorian ghostlore, consider purchasing The Victorian Ghost Hunter’s Casebook. It features fourteen firsthand chronicles of actual ghost hunts.Click on the cover to learn more.

July 2, 2025

Haunted Ancestral Homes 3: The Mystery of Littlecot[e] Hall

This article comes from the February 9, 1892, issue of the Brechin Herald.

Littlecote Hall not only still stands — it now serves as a hotel! Visiting it would seem to be fairly easy. Here’s a 2007 report of a paranormal investigation conducted there. The comments below it are worth reading.

4. The Terror of Glamis CastleIf you’re intrigued by Victorian ghostlore, consider purchasing The Victorian Ghost Hunter’s Casebook. It features fourteen firsthand chronicles of actual ghost hunts.Click on the cover to learn more.

June 25, 2025

Haunted Ancestral Homes 2: The ‘Brown Lady’ of Raynham Castle

This article comes from the February 2, 1892, issue of the Brechin Herald.

[The following part might be difficult to read. It says: “…rivalry rather later than was usual for them. The game of chess had so absorbed their attention that they paid no heed to the hour, and when the clock struck midnight and the fire began to crackle and fall in the dreary way we all know is a sign of dissolution, the gentlemen thought it was time to move. The game was finished; the pieces replaced in the common grave-box of the pawn and knight, and king and queen….”]

Frith’s references are to Catherine Crowe’s chapter on haunted houses in Volume 2 of The Night Side of Nature; Or, Ghosts and Ghost Seers (T.C. Newby, 1848) pp. 73-74 and to Lucia C. Stone’s “The Brown Lady of Rainham,” found in Rifts in the Veil: A Collection of Inspirational Poems and Essays Given Through Various Forms of Mediumship (W.H. Harrison, 1878) pp. 97-98.

Raynham Hall still stands, and it can be visited.

3: The Mystery of Littlecote HallIf you’re intrigued by Victorian ghostlore, consider purchasing The Victorian Ghost Hunter’s Casebook. It features fourteen firsthand chronicles of actual ghost hunts.Click on the cover to learn more.

June 19, 2025

Haunted Ancestral Homes 1: The Demon Drummer of Cortachy Castle

This article comes from the January 26, 1892, issue of the Brechin Herald.

Cortachy Castle still stands! Even better, it can be visited.

2: “tHE ‘BROWN LADY’ OF RAYNHAM CASTLE”If you’re intrigued by Victorian ghostlore, consider purchasing The Victorian Ghost Hunter’s Casebook. It features fourteen firsthand chronicles of actual ghost hunts.Click on the cover to learn more.

June 18, 2025

Haunted Ancestral Homes: An 1892 Newspaper Series Exploring British Ghosts

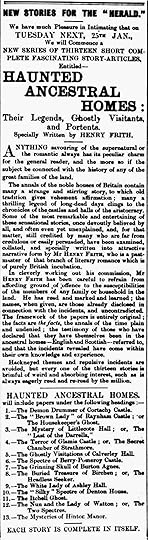

In January of 1892, British newspapers from Angus, Scotland, down to Hampshire, England, announced they would be running a 13-part series. It was titled “Haunted Ancestral Homes: Their Legends, Ghostly Visitants, and Portents” and written by Henry Frith. Here’s what that announcement looked like in the January 19 issue of the Brechin Herald:

The subject of Frith’s series is very similar to John H. Ingram’s book The Haunted Homes and Family Traditions of Great Britain, published the previous decade. However, Frith takes greater creative license, replacing Ingram’s strict reporting with, for instance, word-for-word dialogue that no one could’ve recorded. This is despite Frith introducing the series in the first article by saying “no inventions of the writer shall interfere with” his chronicles.

I intend to make the entire “Haunted Ancestral Homes” series available here in the BLOG section. If I can find a bit of extra information on the haunting or its location — maybe an update or an related image — I’ll toss that in at the end. You’ll find all 13 articles posted on a weekly basis, the way readers enjoyed them in 1892.

If you’re intrigued by Victorian ghostlore, consider purchasing The Victorian Ghost Hunter’s Casebook. It features fourteen firsthand chronicles of actual ghost hunts.Click on the cover to learn more.

June 3, 2025

Speculation on How and Where Dr. Watson Published His Holmes Chronicles, Part One

Though it would be far too dangerous to explain why at this time, I’ve begun to read all of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes adventures: the four short novels and the five collections of tales. I’m reading them in order of publication rather than grapple with reading them chronologically by case (i.e., in the “this case happened before that case and after that case” sequence debated by dedicated Sherlockians such as William Baring-Gould). Attempting to follow the latter, I fear, might lead to madness. After all, Conan Doyle set each adventure whenever he darned well felt like and often with no clear-cut clues of when a story is set.

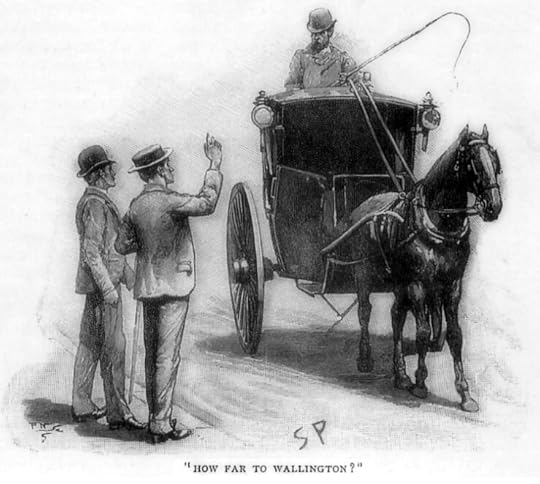

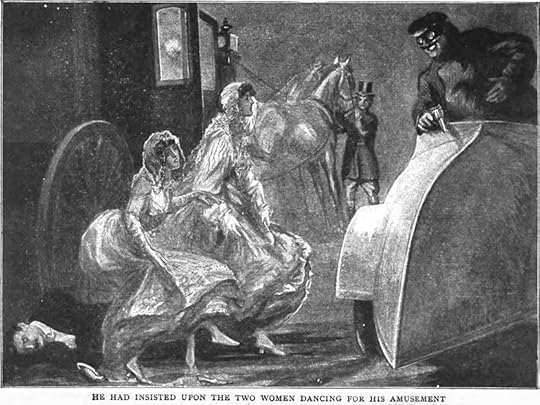

One of Sidney Paget’s wonderful illustrations for the Holmes series. Paget did much to establish how the great detective is visualized by readers and by costumers (though seeing him a boater hat — as he is here — seems not to have taken root).

One of Sidney Paget’s wonderful illustrations for the Holmes series. Paget did much to establish how the great detective is visualized by readers and by costumers (though seeing him a boater hat — as he is here — seems not to have taken root).My main objective in this project is to find evidence of how and where Dr. Watson published his chronicles. Was it in The Strand, where a good many of the stories actually debuted, albeit attributed to the pen of someone named Arthur Conan Doyle? This is how the problem is handled in the well-known TV adaptations starring Jeremy Brett. It’s a fun approach, to be sure, and I do enjoy when the fourth wall is, at least, bumped.

However, I’m fairly certain The Strand Magazine is never alluded to in the tales themselves. I want to see what those texts really do suggest and compare that to what was available in the late-Victorian and early-Edwardian eras, specifically publications likely to print a non-fiction narrative of a private investigator’s methods. It’s all fanciful speculation, of course, but hopefully there might be a point or two of interest in the endeavor.

So far, I’ve read A Study in Scarlet (1887), The Sign of [the] Four (1890), and The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. (1891-1892). Here’s the very first reference I’ve found to Watson recording — and making public — Holmes’s remarkable skill at solving a mystery.

A Study in Scarlet:

Watson [to Holmes]: “Your merits should be publicly recognised. You should publish an account of the case. If you won’t, I will for you.”

Watson: “I have all the facts in my journal, and the public shall know about them.”

There’s not much to go on here, but we see that the doctor intends to become Holmes’s biographer and, in a way, his publicist right from start. Better evidence in found in the next work.

The Sign of the Four:

Watson [referring to the previous case]: “I was never so struck by anything in my life. I even embodied it in a small brochure, with the somewhat fantastic title of ‘A Study in Scarlet.'”

Watson [after Holmes complains of the romantic elements he included]: “I was annoyed at this criticism of a work which had been specially designed to please him. I confess, too, that I was irritated by the egotism which seemed to demand that every line of my pamphlet should be devoted to his own special doings.”

Holmes [on why he must disguise himself at times]: “You see, a good many of the criminal classes begin to know me — especially since our friend here took to publishing some of my cases.”

Ah ha! Watson published that first case as a pamphlet! I’ve run into 19th-century pamphlets fairly often. (There are several ghost-related ones included under “Pamphlets on Individual, Purportedly True Hauntings” on my page titled The Victorian Ghost Hunter’s Library.) As explained on the 19th Century British Pamphlets Online site, these relatively short publications were printed in limited numbers, yet served as “a significant form of publication in the 19th Century and they can complement other publications such as books, newspapers and periodicals.” While pamphlets addressed a wide variety of topics, it’s interesting that they seem to have been a reliable means to share medical discoveries. Watson, then, would have been familiar with pamphlet publication.

I hope to research true-crime pamphlets further, but for now, one might glance over Waldemar Fitzroy Peacock’s 22-page “Who Committed the Great Coram-Street Murder? An Original Investigation” to glean what Watson’s pamphlet might’ve looked like.

Hold on! Why does Holmes say that Watson has taken “to publishing some of my cases”? Some? At this point, one would think that the doctor has only published A Study in Scarlet. I have no answer, and it joins several stumpers I’ve hit during this first chunk of reading. Can we safely assume that the police inspector Athelney Jones in A Sign of the Four reappears as the police inspector Peter Jones in “The Red-Headed League”? Why is the landlady named “Mrs. Turner” in “A Scandal in Bohemia,” not the “Mrs. Hudson” named previously in The Sign of the Four and afterward in “The Five Orange Pips”? Why is John H. Watson called “James” by his wife in “The Man with the Twisted Lip”? These mini-mysteries have probably been addressed elsewhere by those smarter than me. I must remain focused on the task at hand!

The endlessly fascinating Arthur Conan Doyle

The endlessly fascinating Arthur Conan DoyleWhile pamphlet publication accounts nicely for A Study in Scarlet and The Sign of the Four, it feels doubtful that Watson would publish the many shorter narratives to follow in the same way. Even though pamphlets could be very short, I’ve found no evidence that they accommodated a significant series. That’s monthly magazine or possibly book territory. Let’s turn to those shorter chronicles.

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

“A Scandal in Bohemia”

Holmes [to Watson]: “By the way, since you are interested in these little problems, and since you are good enough to chronicle one or two of my trifling experiences, you may be interested in this.”

Watson: “I was already deeply interested in his inquiry, for, though it was surrounded by none of the grim and strange features which were associated with the two crimes which I had elsewhere recorded, still, the nature of the case and the exalted station of his client gave it a character of its own.

“The Red-Headed League”

Holmes: “I know, my dear Watson, that you share my love of all that is bizarre and outside the conventions and humdrum routine of everyday life. You have shown your relish for it by the enthusiasm which has prompted you to chronicle, and, if you will excuse my saying so, somewhat to embellish so many of my own little adventures.”

“A Case of Identity”

Holmes [to Watson, regarding a delicate case]: “I cannot confide it even to you, who have been good enough to chronicle one or two of my problems.”

“The Five Orange Pips”

Watson: “When I glance over my notes and records of the Sherlock Holmes cases between the years 1882 and 1890, I am faced by so many which present strange and interesting features that it is no easy matter to know which to choose and which to leave. … There is, however, one of these which is so remarkable in its details and so startling in its results that I am tempted to give some account of it in spite of the fact that there are points in connection with it which never have, and probably never will be, entirely cleared up.”

“The Speckled Band”

Watson: “The events in question occurred in the early days of my association with Holmes, when we were sharing rooms as bachelors in Baker Street. It is possible that I might have placed them upon record before, but a promise of secrecy was made at the time, from which I have only been freed during the last month by the untimely death of the lady to whom the pledge was given. It is perhaps as well that the facts should now come to light, for I have reasons to know that there are widespread rumours as to the death of Dr. Grimesby Roylott which tend to make the matter even more terrible than the truth.”

“The Engineer’s Thumb”

Watson [contrasting this case to another]: “[T]he other was so strange in its inception and so dramatic in its details that it may be the more worthy of being placed upon record, even if it gave my friend fewer openings for those deductive methods of reasoning by which he achieved such remarkable results. The story has, I believe, been told more than once in the newspapers, but, like all such narratives, its effect is much less striking when set forth en bloc in a single half-column of print than when the facts slowly evolve before your own eyes, and the mystery clears gradually away as each new discovery furnishes a step which leads on to the complete truth.”

“The Noble Bachelor”

Watson: “As I have reason to believe, however, that the full facts have never been revealed to the general public, and as my friend Sherlock Holmes had a considerable share in clearing the matter up, I feel that no memoir of him would be complete without some little sketch of this remarkable episode.”

“The Copper Beeches”

Holmes [regarding how the “least important and lowliest manifestations” of art can sometimes be its “keenest pleasure”]: “It is pleasant to me to observe, Watson, that you have so far grasped this truth that in these little records of our cases which you have been good enough to draw up, and, I am bound to say, occasionally to embellish, you have given prominence not so much to the many causes célèbres and sensational trials in which I have figured but rather to those incidents which may have been trivial in themselves, but which have given room for those faculties of deduction and of logical synthesis which I have made my special province.”

Watson: “And yet … I cannot quite hold myself absolved from the charge of sensationalism which has been urged against my records.”

Holmes: “[Y]ou have erred perhaps in attempting to put colour and life into each of your statements instead of confining yourself to the task of placing upon record that severe reasoning from cause to effect which is really the only notable feature about the thing. … You have degraded what should have been a course of lectures into a series of tales. … [Y]ou can hardly be open to a charge of sensationalism, … [b]ut in avoiding the sensational, I fear that you may have bordered on the trivial.”

Watson: “The end may have been so, … but the methods I hold to have been novel and of interest.

Holmes: “Pshaw, my dear fellow, what do the public, the great unobservant public, who could hardly tell a weaver by his tooth or a compositor by his left thumb, care about the finer shades of analysis and deduction!”

These exchanges give some insight into Watson’s goals for penning the investigations and Holmes’s disapproval of how his friend handled them. Holmes wants them to be more about logical deduction; Watson contends the events demand a more rounded approach, one encompassing the stuff of life. Great characterization here, but little about the “how and where” of publishing the narratives.

Maybe there are some clues in the word choices: chronicle, account, record, and even statement. There’s also a contrast between what Waston is writing and what’s found in newspapers. Still, as implied in the phrase “the great unobservant public,” Watson is presenting his narratives to a wide readership. He remains Holmes’s publicist.

In terms of specific journals, let’s start with suspects bearing some basic resemblance to The National Police Gazette. Despite the title, this journal was aimed at male readers of all walks of life rather than those in law enforcement. But it was American, not British. And it was decidedly sensational, which perhaps relates to Holmes and Watson’s concern for how much sensationalism was added. I’ll continue to look into this possibility of a non-fiction journal that specialized in crime fighting.

For now, it might be just as likely that Watson sought more general magazines. Indeed, it wasn’t unusual for true-crime articles to be found in these broad-appeal journals, some of which are listed here and here. Conan Doyle himself wrote a three-part series of “studies of the actual history of crime” — found here, here, and here — for none other than The Strand. So, yeah, I’m back to the same magazine where most of the Holmes tales were published.

But this investigation has just begun. I’ll have more to say when I’ve read more of Watson’s published records, accounts, chronicles….

— Tim

May 5, 2025

The Complete Crimes of the Motor Pirate: An Outlaw Races into the 20th Century

The Complete Crimes of the Motor Pirate is now available, completing the second phase of the Curated Crime Collection. This book combines G. Sidney Paternoster’s novel The Motor Pirate with his sequel, The Cruise of the Conqueror: The Further Adventures of the Motor Pirate. I’m 99% certain it’s the first time the two works have been published in a single volume, and I’m even more certain these are the only works Paternoster wrote about the dastardly title character.

And a decidely dastardly character he is! Any researcher digging into the history of super-villains should shove a shovel at these two novels. Along with a variety of skills that make “the Pirate” an almost-unstoppable criminal, he is a mad genius, especially when it comes to internal combustion engines!

The Joker, the Batmobile — But No BatmanIn the first adventure, the Pirate invents an automobile that can reach speeds up to 100 miles per hour! Not a big deal these days, but this novel debuted in 1903 — when cars where in their infancy — and Paternoster’s explanation of how the remarkable engine works adds a dash of science fiction to what’s otherwise a tale of high adventure. In fact, this work ends in what might well be fiction’s very first high-speed car chase!

Charles R. Sykes’s illustration for The Motor Pirate

Charles R. Sykes’s illustration for The Motor PirateThe sequel then moves from the roads of England to the waters between it and the Continent. One early ad cites a review describing this work as heralding the “introduction of the motor-boat into fiction.” In other words, Paternoster was spinning the steering wheel of crime fiction in a brand new direction.

As someone who enjoys charting the evolution of English, I really liked seeing how, in the early 1900s, the language of automobiles mirrored that of horse-drawn carriages. For instance, one doesn’t simply get out of a motorcar; one “dismounts” it. One escapes “upon” a car instead of in it. A flat tyre is an “injury,” almost as if it’s a horse’s sprained leg. Naturally, I left all these fun bits of history as is.

The Editor’s CutNow, like it or not, almost all novels have been shaped — if only slightly — by an editor. I try to use a light hand when editing old material. In this project, though, I had to deal with the first name of the Pirate inexplicably changing from the first novel to second. Had Paternoster forgotten it, or did he never imagine the two works being printed together? Similarly, what was once a bullet wound in the shoulder somehow reappears as a “broken arm.” Since readers of this edition are likely to read both novels back-to-back, I went ahead and made things more consistent.

In addition, while Paternoster was a master at telling a ripping adventure tale, he could’ve used a few editor’s tips when it came to writing a whodunit. Granted, this branch of mystery fiction was still coalescing in 1903. Think of how the earlier Sherlock Holmes stories don’t really give readers all the clues needed to “match wits” with the great detective. However, as first published, The Motor Pirate grants readers barely any challenge at all in unmasking the focal gentleman thief/murderer. At the same time, that identification seems absurdly difficult for the narrator, James Sutgrove, and Inspector Forrest of Scotland Yard, even though they have all the same clues as readers. These two characters form a sort of Watson and Holmes, with Sutgrove’s knowledge of cars proving valuable when Forrest is assigned to the case. To see them missing the blatant signs of the Pirate’s real identity is, well, a bit painful. So I tweaked a few passages to relieve that pain a little.

Join the RideThat said, I never lost sight of the possibility that Paternoster might’ve wanted readers to be aware of who the dangerous character is well before his unsuspecting crime-solving duo. After all, that can be a nice way to build tension. So, yeah, you’ll probably still have a strong hunch of who the culprit is early on. Not to worry — it’s still a really fun adventure novel.

And since that culprit is confirmed in the first novel, the second one becomes much more a cat-and-mouse story — or a “howcatchem” — and Paternoster is very good at writing this. Editorially, I took a backseat in the Pirate’s motorboat and enjoyed the cruise.

Now you can join the ride, too! Scroll down to the section for The Complete Crimes of the Motor Pirate on this page for more information.

–Tim

March 19, 2025

Some Ghostly Newspaper Discoveries

I accepted an offer to give Newspapers.com a free week-long trial. I found some interesting, if minor, articles. All are related to my ghostly volumes published by Brom Bones Books. I’ll present them in chronological order.

An 1828 Reference to “Ghost Hunters”I found an 1828 article that uses the term “ghost hunters” in an issue of the Essex, Herts and Kent Mercury. I quickly added this to The Rise of the Term “Ghost Hunt” TARDIS, a page that charts my discoveries regarding the long history of that still-familiar (and, in some circles, controversial) term. From time to time, I’ve come upon the misconception that ghost hunting begins in the late 1800s in response to the rise of Spiritualism and the Society for Psychical Research. My own digging has revealed that there’s far longer, much richer history to this branch of paranormal investigation. I write about that in Certain Nocturnal Disturbances: Ghost Hunting Before the Victorians.

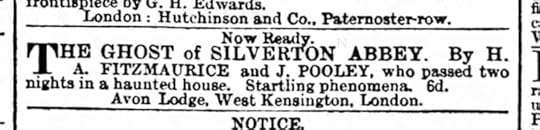

The Silverton Abbey Haunting and Late-Victorian Ghost HuntingSomething that might’ve fit nicely in The Victorian Ghost Hunter’s Casebook is a 16-page pamphlet titled The Ghost of Silverton Abbey: A True Story. It was published in 1896 and written by H.A. Fitz-Maurice and J. Pooley. Unfortunately, it’s extremely rare, and a guy who pounces on a free trial to Newspapers.com ain’t going to buy a ticket from the North American Great Plains to Britain to see it. (Of course, there are other very nice things one might visit in Britain, but that’s a discussion for another time.)

I did, however, find a couple of newspaper articles by the same authors. In fact, I found the article that first stirred interest in the haunting. It was published in London’s The Standard on April 22, 1896, and the writer reviews a variety of weird phenomena happening at what he renames “Silverton Abbey” to protect the actual place. (The real names of the building and the letter writer are divulged here.)

A number of responses were published in The Standard, but the one I personally found most interesting is from Fitz-Maurice and Pooley. They recount their investigation of the site in the May 6th issue, and describe some of the “peculiar attributes” they encountered there. Over two nights, the duo heard footsteps, something heavy being dragged, and a loud bang. They conclude:

We are fully aware that the usual objections will be urged; but we can only say we took all precautions, such as examining bolts, bars, &c., and patrolling the house twice during the night, being provided with a pistol and lights, and the fact remains, based on our joint testimony, that the most unusual sounds were heard, which we who heard them are quite sure could not have been caused by rats, cats, wind, and so forth. We can offer no explanation, and must refer any one interested to the various authors and Societies who investigate these matters.In other words, Fitz-Maurice and Pooley were not among those more formal investigators. The manifestations seem fairly routine, if not disappointing, but it would be interesting to read that pamphlet to get a sense of how amateur ghost hunters went about their business.

The case sparked several letters, including a follow-up by Fitz-Maurice in the May 8th issue. He points out that the house was a fairly new one and then mentions that, based on his “reading on the subject,” hauntings should be “received quietly and in a sympathetic manner” or the ghost is liable to be scared away. Subsequent investigators reported their experiences in the May 13th and May 21st issues of the Standard, and these take a more skeptical stand on some of the phenomena.

There’s not enough here to qualify Fitz-Maurice and Pooley for the Ghost Hunter Hall of Fame. I’ll certainly reconsider this if I ever manage to read their pamphlet. Until then, you’ll find comparable pamphlets listed and linked in the “Pamphlets on Individual, Purportedly True Hauntings” section of The Victorian Ghost Hunter’s Library.

Remember that Help-for-the-Haunted-ish Ad?Now, whether Vera Van Slyke is fictional or factual is a matter of debate. I usually assume my great-grandaunt, from whom I inherited the chronicles of Van Slyke, was either making things up entirely or, at least, allowing her imagination to “enhance” the tales.

Vera Van Slyke (1868-1941) and Ludmila “Lida” Bergson (1882-1958), née Prášilová, a.k.a. Lucille Parsell

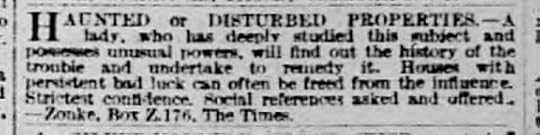

Vera Van Slyke (1868-1941) and Ludmila “Lida” Bergson (1882-1958), née Prášilová, a.k.a. Lucille ParsellYet, quite a few years ago, I came upon and blogged about a 1919 advertisement with the heading: “HAUNTED OR DISTURBED PROPERTIES.” The ad, run in London’s The Times, offers aid from a person who “will find out the history of the trouble and undertake to remedy it.” This has intriguing similarities to an ad run by Van Slyke, as discussed in Help for the Haunted: A Decade of Vera Van Slyke Ghostly Mysteries. However, I had never seen the quirky ad itself until now:

Something I hadn’t known was the ad ran just about every week for several months. The earliest printing I found was February 25th, and the latest was June 3rd. It would be interesting indeed if this ad had been placed by Vera Van Slyke herself!

— Tim

March 5, 2025

More than Half of the Curated Crime Collection Is Now Available

The fifth volume in the Curated Crime Collection is available for sale. Titled The Rise of Ruderick Clowd & In the Bishop’s Carriage, it combines two distinctive crime novels, the first by Josiah Flynt (1869–1907) and the second by Miriam Michelson (1870-1942).

These two works fit nicely together because of their parallels. Both were written by American authors and debuted in 1903. Both lead characters, whose crimes lean toward picking pockets and burglary, are products of poverty and “the streets.” Both characters grapple with a crisis of conscience when their criminal activity forces them to, at least, consider committing homicide.

However, the two works are also very different, especially in tone. Ruderick Clowd is a work of stark realism, a piece in the tradition of Stephen Crane’s 1893 novella Maggie: A Girl of the Streets and Frank Norris’s 1899 novel McTeague. Flynt’s title also calls to mind other realist novels dealing with complex characters struggling with complicated moral choices: William Dean Howells’ 1885 The Rise of Silas Lapham and Abraham Cahan’s 1917 The Rise of David Levinsky.

Josiah Flynt

Josiah FlyntAn example of Flynt’s gritty realism — and his critique of the prison system — appears when a prison chaplain urges the incarcerated Clowd to do better. The hardened inmate replies:

This ain't the place for anybody's conscience to get in its work. . . . You send a fellow here for ten years, shut him up in a cell, put a crowd o' fellows around him him just like him, and then tell him to be good. You might as well tell him to go and catch fish out in the courtyard. I know where I stand, and I know why I stand there, too. I'm a crook, and you know it and the whole prison knows it. I was sent here for doin' crooked work. I admit all that, and I ain't kicked at what I've had to go through. But don't you get it into your head for a moment that I'm thinking o' losin' the good times that are comin' to me when I'm turned loose.Despite Clowd’s apparent lack of conscience here, some chapters later, readers come to learn he has one:

It all might have been very different; everything had been carefully planned that it should be very different; but -- Ruderick Clowd's conscience had interfered.Indeed, a reader might have wondered if Flynt’s title should’ve been The Fall of Ruderick Clowd, given the character’s descent into street crime, mob heists, prison life, and failed love relationships. But the author provides an ending that is both believable and — maybe not happy exactly — but happy enough. One shouldn’t ask too much for someone who’s experienced all that Ruderick Clowd has.

Miriam Michelson’s Nance Olden, on the other hand, is something very different. Michelson worked as a drama critic, and her knowledge of backstage life and onstage theatrical flair come into play. In fact, In the Bishop’s Carriage has enough narrow escapes and coincidental meetings that Michelson transports the feel of farce from the stage to the page.

Miriam Michelson

Miriam MichelsonAs a result, Nance Olden becomes an entertaining and capable female — role model isn’t the right word, so let’s settle for protagonist — in an era when women’s roles were changing rapidly. Remember, this is the generation that won the vote for women.

Still, the evolution from street criminal to stage performer is not an easy one. Dazzled by a diamond worn by someone who shares the stage with her, Olden finds herself easily tempted to fall back into her illicit ways:

I shut the door.But not behind me. I shut it on the street and -- Mag, I shut forever another door, too; the old door that opens out on Crooked Street. With my hand on my heart, that was beating as through it would burst, I flew back again through the black corridor, through the wings and out to Obermuller's office. With both my hands I ripped open the neck of my dress, and, pulling the chain with that great diamond hanging to it, I broke it with a tug, and threw the whole thing down on the desk in front of him.

"For God's sake!" I yelled. "Don't make it so easy for me to steal!"

Like Ruderick Clowd — and despite the very different tones of the two novels — Nance Olden has to struggle to establish a new life for herself.

I’m proud and pleased to have reissued these two novels. I think both are important contributions to American literature of the early 1900s, and — as partners in crime — Flynt’s Clowd and Michelson’s Olden illustrate the breadth found in crime fiction of that era.

— Tim

February 26, 2025

Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit: An Embankment Between Whaley Bridge and Chapel-en-le-Frith, Derbyshire

A Headstrong Skull

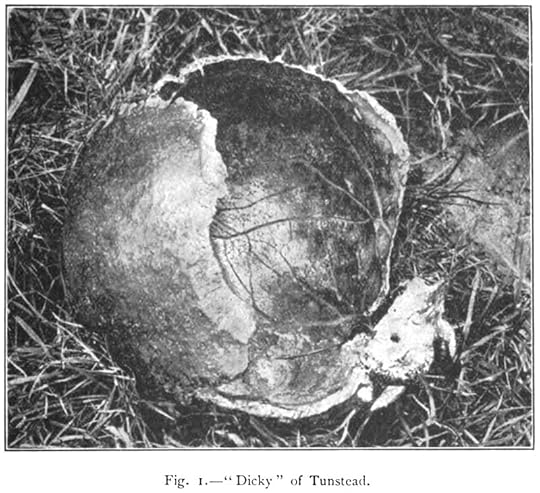

A Headstrong SkullOnce upon a time, a folktale circulated in Derbyshire, England. The story was set in Tunstead, a bit south of the midpoint between Whaley Bridge and Chapel-en-le-Frith. Apparently, a local farmer kept a skull on the premises. It was a real skull, mind you! There are pictures! Exactly why the farmer had it is less certain. Back when the skull’s original user — named “Dicky” or “Dickey,” depending on the source — had been buried, her or his — sources disagree on the gender — ghost grew unhappy. That spirit created a ruckus involving wailing sounds, knocked-about furniture, and wandering and dying cows. Somehow, it was determined that keeping the skull on the farm kept said spirit quiet and content. In fact, “it” protected the place against theft.

And so the skull remained on the farm for many decades — without showing the slightest sign of decomposition!

From G. Le Blanc Smith’s “Dicky of Tunstead,” The Reliquary and Illustrated Archæologist 9 (Oct., 1905) pp. 228-237. This is one of most in-depth articles on the folklore surrounding the skull.

From G. Le Blanc Smith’s “Dicky of Tunstead,” The Reliquary and Illustrated Archæologist 9 (Oct., 1905) pp. 228-237. This is one of most in-depth articles on the folklore surrounding the skull.At least, that’s what was said. Seemingly, the earliest written record of the oral tale is found in an 1809 book titled Tour through the Peak of Derbyshire, by John Hutchinson. Unfortunately, I haven’t found a scan of this rare work online. Hutchinson is referenced, though, in an 1862 book titled Tales and Traditions of the High Peak, by William Wood — and there’s a transcription of that here.

Wood’s book probably had a hand in shaping a railroad haunting involving the skull, given that the work had been published just one year earlier. You see, in 1863 — when Stockport, Disley and Whaley Bridge Railway workers ran into trouble while laying tracks for a line from Whaley Bridge down to Buxton — they had a persnickety ghost nearby upon whom to place the blame.

To be sure, Llewellyn Jewett’s “An Address to ‘Dickie,” one of the best written records of the folktale, was published in 1867 and includes a mention of the railroad workers’ trouble with the headstrong spirit. The same year, William Bennet shared his findings regarding the skull’s origins. He also notes the railroad encounter, suggesting that it had become a fixed part of the lore by then.

From Tale to RailThe June 3, 1863, issue of the Derby Mercury reported that the new Whaley Bridge to Buxton line had been opened — but only after considerable difficulty in laying the tracks. (A scan of the original is here for free, but sign-up is required.)

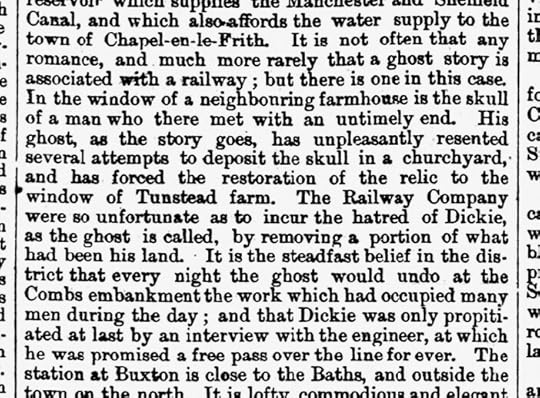

About two miles and a half from Whaley Bridge the line crosses the head of the Combs Valley, near the reservoir which supplies the Manchester and Sheffield Canal, and which also affords water to Chapel-en-la-Frith. Here, for about a quarter mile, the engineer, Mr. A. C. Crosse, met with the greatest difficulty. It was necessary to construct a bridge beneath which the road from Combs to Chapel might pass. The navvies dug through scores of feet of clay resting upon sand, but could find nothing upon which to build a foundation. The earth also of which the embankment was to be made forced outward the surface of the ground, and made it bulge to a remarkable extent. Finally, the Company were compelled to abandon the construction of the bridge and to build another upon the nearest solid ground that they could find. This has necessitated a considerable diversion of the highroad.While there’s no mention of the ghost in that article, there is in an otherwise almost identical one that appeared two days later in the Nottinghamshire Guardian:

It appears newspaper editors disagreed on whether or not to include the tidbit about the fussy phantom. Yet that tidbit garnered national attention when a London publication called The Panorama reprinted it as “A Railway Ghost” in its Oddities section. To be sure, in 1863, railroad hauntings were a novelty. It took a few decades for musty old ghosts to climb aboard those shiny, newfangled trains, something I discuss in my introduction to After the End of the Line: Railroad Hauntings in Literature and Lore.

Tracking the Ghost TodaySadly, the skull appears to have gone the way of all flesh. It can no longer be visited, in other words. But its curious history still sparks interest. Darcus Wolfsom did some spook snooping for a site called Explore Buxton, and there you can see another picture of the skull provided by that town’s Museum and Art Gallery. Since Dickie’s range of ghostly activity seems to have been wide and uncertain, focusing on the railroad encounter might help any paranormal investigators interested in the spot.

Indeed, if the present railroad winding from Whaley Bridge Station down and over to Chapel-en-le-Frith reflects the specter-diverted 1863 line, the stretch of tracks west of the Combs Reservoir provides a rough idea of where the ghostly protest was probably made all those years ago. The Combs Reservoir Railway Bridge might serve as a nice starting point, and from there, one can follow a footpath south between Meveril Brook and the reservoir itself. These serve as safe alternatives to actually walking the dangerous tracks. As always, if you do conduct an investigation, be it formal or informal, please give us a report.

And remember that Dickie was appeased with an offer of eternal free rides along those tracks. Maybe the best way to have an otherworldly encounter, then, is by riding the train.

Discover more “Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit” at the page forAfter the End of the Line: Railroad Hauntings in Literature and Lore.