Jeremy Butterfield's Blog, page 24

April 25, 2016

Lording it over – or lauding it? All glory, laud, and honour … Commonly confused words (29-30)

Quick takeaways

Quick takeawaysIf you laud someone, you praise them.

If you lord it over someone, you treat them arrogantly and in a domineering way.

Very occasionally, lorded seems to be used for lauded.

Conversely, and rather more often, laud (in all inflections) seems to be used for lord, which I find more difficult to explain semantically. However, this eggcorn goes back at least to the 19th century.

Perhaps someone can help.

You should be lorded because…

(No, the above is not from a conversation between a member of the government and a Tory party donor.[1])

In a Daily Express online article (ok, I know, I know, an organ that is not necessarily the guardian of the nation’s orthography), my eye was caught by the juxtaposition of a standard spelling and an eggcorn.

In the body of the article, someone was quoted as saying “You should be lauded because you’re wearing uniform, you should be celebrated for wearing uniform.” But the summary box at the side (I don’t know what you call that; somebody will no doubt enlighten me) had “You should be lorded because you’re wearing uniform.”

(Interestingly, when I looked again after a few hours, the mistake had been corrected, possibly by a vigilant sub-editor, if such people still exist)

Inevitably, this set me wondering whether this was a complete one-off, or a more widespread homophone eggcorn. It gets only a passing mention in the main online eggcorn database, so I decided to do a bit of my own linguistic gumshoeing.

Remind us. What’s an eggcorn, again?

In case any gentle readers have forgotten what an eggcorn is, here’s the OED definition: “An alteration of a word or phrase through the mishearing or reinterpretation of one or more of its elements as a similar-sounding word.”

And for those who have forgotten (wake up, you at the back!) what a homophone, as opposed to a homophobe, is: quite simply, it is a word pronounced identically to another one that has a different spelling. The classic case is, of course, the dreaded their/there/they’re.

(For those who wish to pursue the topic, here’s a link to a Grauniad list of homophone confusions.)

Why this eggcorn makes sense

The OED definition misses out a crucial feature of eggcorns: they are not arbitrary or random (in the older sense of that word). The change has to be semantically and grammatically justified — at least in the mind of the eggcorner. So, to take “lorded” being used instead of “lauded”, as in the quoted example: a) the verb to lord exists as part of the phrasal verb to lord it over and is probably part of most people’s vocabulary, so it is a spelling waiting to be appropriated for the “laud” meaning; b) if you use lord as a transitive verb, presumably you are “making someone a lord”, i.e. you are putting them in an exalted position, so that makes sense semantically, and explains the eggcorn. But, was it a hapax? The answer is no.

If you are enjoying this blog, and finding it useful or interesting, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column, above the Twitter feed) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging semi-(ir)regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

I like being lauded. Who doesn’t?

First, I looked in the Oxford English Corpus. It throws up 1,699 occurrences of lord as a verb. If you filter out the word over in a five-word window either side (on the assumption that, if used with over, lord couldn’t be an eggcorn for laud) that reduces the number by about half (to 841), but a quick scan of those remaining citations did not reveal any as an eggcorn for lauded.

However, a search on Google for be lorded minus “over” (to filter out the passive use of “to lord it over someone”) does throw up a few echt eggcornisms, such as:

“Like many organizational processes, socialization and prestart training may simply be lorded as positive features of the organizations [sic] human resource …”

And in a comment on a Bradford Herald & Argus article of 27 July 2015 about new investment in the city centre:

“Any other city in the country this would be lorded as a big investment and showing confidence in the city.”

So, while rare, this eggcorn is not unique [2].

Don’t laud it over me!

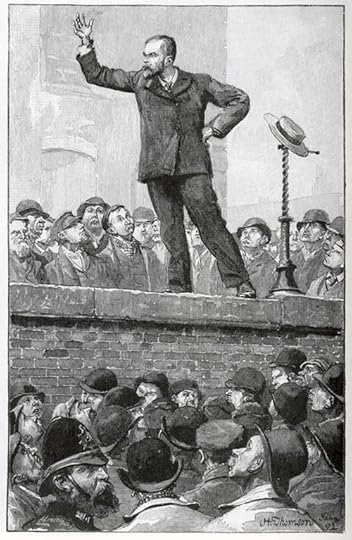

A demagogue attempting to “laud” it over a crowd, but not seeming to have much success.

What surprised me, however, is that in the OEC data laud appears to be more often used for lord than the other way round. A search for laud as verb followed immediately by it produced 77 examples, of which 7 were eggcorns, e.g.:

“So confident was Blair of this that he lauded it over his critics , sneering before parliament…”

A Google Ngrams search unearths plentiful examples of the eggcorn this way round, in a wide range of texts, including novels by Catherine Cookson and Barbara Taylor Bradford.

More surprising to me was that this form goes back to the nineteenth century, often appearing in religious tracts of various kinds:

“…that ambitious and seditious demagogues might laud it over the throne, and the aristocracy; and bow the neck of the lordly and the mighty to their unhallowed yolk.”

Truth’s Advocate against Popery and Fanaticism, 1822.

“What has become of your self-complacency? Where the pride and the lauding it over your poor fellow-sinner?”

The Gospel magazine, and theological review. Ser. 5. Vol. 3, no. 1 July 1874

The only explanation I can think of for laud it over in those days is this, but hope someone can supply a better one:

Laud meaning praise is a word used principally in religious contexts;

People in the nineteenth century would have been familiar with it in that context;

If they heard but never read “lord it over”, they would learn it as an idiom, a gestalt, and slot the word they knew – laud – in;

For US writers, lord referring to the aristocracy might not be in their active vocabulary, and this might have helped block that analysis of the phrase.

Convinced? I’m not, but it’s as good a guess as any.

(On the eggcorns forum, a wag has suggested that “perhaps the person ‘lauding it over’ me is singing his own praises so loudly that he can’t hear me?”)

All glory, Lord, and honour

The correct version is, of course, All glory, laud, and honour, to thee, Redeemer, King.

I remember first singing this, with its simple, stirring tune at school. But I have to confess that if I hadn’t been learning Latin and hadn’t seen the words written down, I would have interpreted it as “Lord”. And that is what many people do, as a Google search will quickly show [3].

Lauds

From the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. In Books of Hours, a portrayal of the Virgin being visited by her cousin Elizabeth was often placed at the beginning of the section on Lauds.

Lauds is “A service of morning prayer in the Divine Office of the Western Christian Church, traditionally said or chanted at daybreak, though historically it was often held with matins on the previous night.” It is one of the parts of the daily round of prayer: matins, lauds, prime, terce, sext, none, vespers, compline. Auden wrote a sequence of poems about each one (excluding matins) including Lauds, with its sing-song echoic stanza pattern, based on the medieval poetic form, the cossante.

Among the leaves the small birds sing;

The crow of the cock commands awaking:

In solitude, for company.

Bright shines the sun on creatures mortal;

Men of their neighbours become sensible:

In solitude, for company.

The crow of the cock commands awaking;

Already the mass-bell goes dong-ding:

In solitude, for company.

Men of their neighbours become sensible;

God bless the Realm, God bless the People:

In solitude, for company.

Already the mass-bell goes dong-ding;

The dripping mill-wheel is again turning:

In solitude, for company.

God bless the Realm, God bless the People;

God bless this green world temporal:

In solitude, for company.

The dripping mill-wheel is again turning;

Among the leaves the small birds sing:

In solitude, for company.

1 As a transitive verb, to lord can mean to make someone a lord, though this use is archaic.

2 I sometimes wonder if there any totally unique [please don’t tell me I can’t qualify “unique”] eggcorns.

3 Google also showed me a version titled “All glory, praise, and honour”, presumably because laud is such an archaic word.

Filed under: Advice for writers, Confusable words, eggcorns, Grammar, Meaning of words, Poetry, Spelling Tagged: easily confused words, W.H. Auden

April 16, 2016

Damp Squid

I’m relieved to know I’m not a “racist OED lapdog.” A splendid review of my little “Damp Squid.”

Daniel Cassidy did no original research at all. His idea of research was to abstract information from dictionaries, then sneer at the people who had done the work for him. His main targets were the Oxford English Dictionary and Merriam-Webster, who he misrepresented as a clique of WASP bigots. Cassidy called these bastions of the linguistic establishment ‘the dictionary dudes’. In reality, of course, there is more of an implied criticism of the main dictionary-makers in the Irish language in Cassidy’s work, as none of Cassidy’s insane phrases like pá lae sámh and béal ónna are mentioned in any of the Irish dictionaries. It is also interesting that when Cassidy was confronted with a real Irish person who knew some Irish and could clearly see that Cassidy knew nothing about the subject, Cassidy was quite happy to hide behind the authority of the OED. This happened in an RTÉ radio…

View original post 603 more words

Filed under: Uncategorized

March 15, 2016

Like lemmings to the slaughter? Like lemmings to the sea? A Norwegian word in English.

One of the curiosities of English is why this diminutive creature has become a byword for impulsive herdlike behaviour, even mass hysteria. These appealing northern rodents are the victims of a bad press—or at least a very inaccurate one.

A computer game and a TVad

For many people the word will bring to mind an unstoppably addictive computer game created in 1991. Lemmings’ supposed suicidal urges were also the inspiration for a 1985 TV advertisement launching Apple Macintosh’s Office. Suited businesspeople were shown walking blindfolded and in single file up to a cliff edge, from which they hurled themselves into the abyss, until the last in the line took off his blindfold to the voiceover, “You can look into it. Or you can go on with business as usual.”

A potent urban myth

That lemmings deliberately self-destruct en masse is a complete myth, but one that has a powerful hold on the popular imagination. It is one of those many mistaken things that we all “know” (in the same way that we “know” that Eskimos have dozens of words for snow). And it is a myth firmly embedded in English as a way of symbolizing people who unthinkingly follow what the crowd are doing, often with dangerous, if not downright fatal, consequences.

Where did the myth originate?

A compelling sequence from a 1958 Walt Disney short nature film entitled White Wilderness has a lot to do with it. It purported to show wave after wave of lemmings plummeting over precipitous cliffs into the Arctic Ocean. Accompanied by portentous commentary and melodramatic music, that film helped sear the idea of rodents with a death wish into the public’s consciousness. It was, however, a cruel fake. Clever camera angles and good editing made it look real, but the (actually rather few) lemmings were cascading into a river, not into the sea, and they were, it seems, being launched from a rotating turntable. If you watch that footage—which now looks very much of its era—you will understand how the use of lemmings as a powerful metaphor for unthinking, self-destructive mass behaviour took off.

“The science bit”

Lemming describes twenty species subdivided into six genera and belonging to the same superfamily as rats, mice, gerbils and hamsters. They are widespread in the cooler north of Eurasia and North America and range from three to six inches in length. Far from succumbing to suicidal groupthink, these creatures live solitary, hermitic lives, only associating with others, as they must, for mating purposes. Unlike other rodents, which have inconspicuous coats, their pelts are variegated. They are also aggressive towards predators. The Norwegian lemming, Lemmus lemmus, travels considerable distances in its migrations.

Populations fluctuate wildly

Lemming populations fluctuate wildly for reasons not fully understood, and when population density reaches a critical level, they migrate collectively. Since they can swim, they may attempt to cross stretches of water that are beyond their abilities and consequently drown.

History of a simile

The OED gives the first example of the metaphorical use from a 1959 book (“Home-going office workers…potent in mass as a lemming migration“), but Google Ngrams throws up an example from the 1930s: “…logicians fling themselves headlong in hordes, like lemmings; and suicidally discuss the import of ‘propositions’ such as ‘The King of Utopia died last Sunday…,” from The Principles of Art by the British philosopher R.G. Collingwood.

On a more pedestrian level, but more dramatically, Life of 5 January 1942 reported that “Men and Women are swarming out of the Navy Building, the War Department, Labor, Interior, Commerce, not with the orderliness of ants but like lemmings swarming blindly toward the Baltic.”

These examples predate the Disney film and suggest that the myth was current well before the film appeared.

How the simile works

Typically, an explicit comparison is made using the preposition like. Tendentiously, as in:

At present, all countries of the world are marching like lemmings over the philosophical precipice to collectivism.

Financial Sense Online, Editorials 2005.

Or slightly naughtily, as in:

…the run of articles about how being tall and good looking and banging Playmates who line up like lemmings ready to fall over his penis made Michael Bay…

The Hot Button, 2002.

In the first the reference to cliffs is explicit, in the second it is punningly implicit. In a minority of examples with like, the word cliff actually appears in the context:

Sky One’s audience has been deserting it, disappearing like lemmings over a cliff, according to Dawn Airey, the managing director of Sky Networks.

Sunday Times, 19 September 2004.

The set phrase “like lemmings to the sea” seems to have emerged in the 1950s. The first Ngrams example I can find is from 1952:

He walked from Grand Central to Eighth Street, kids hitting New York go downtown like lemmings to the sea, and he was a confirmed New Yorker by Thirty-fourth.

The Time and the Place, (a novel), Robert Paul Smith, 1952.

The comparison is also lexicalized in the adjective lemming-like:

After the Diana nonsense, when complete strangers lemming-like threw themselves into publicity-driven grief, through Charles and Camilla’s redemption, we are now spoon-fed the William and Kate Show.

Daily Telegraph, 2012, quoting MSP Christine Grahame.

Like lemmings to the slaughter

As I was writing this, I wondered, “Has anyone changed ‘like lambs to the slaughter’ to ‘like lemmings to the slaughter’”. And, sure enough, they have, but the phrase is not terribly common. A google for those exact phrases throws up under 3,000 for the rodent one, but over 650,000 for the ovine one. The one with lemmings seems slightly odd, since they are not exactly slaughtered by another agent, but it’s an interesting example of a blend of two phrases. Pedants might consider it a sort of malapropism (or it might be a sort of phrasal eggcorn). However, the examples seem to suggest that it is different from “lambs to the slaughter”. Whereas the latter emphasizes that the victims go meekly into a situation of whose dangers they are unaware, the lemmings simile foregrounds the idea of people blindly rushing to do something foolish or dangerous.

In one example it’s the heading to a blog (spamdalot) that continues as shown: “Like Lemmings To The Slaughter. One thing I’ve noticed about Portland is that the pedestrians here have a deathwish…“. In another it’s also a heading, this time in a post on an investment website (Stanford Brown): “Like lemmings to the slaughter………at our April Insight we highlighted that individuals make such poor investors principally because of our insatiable appetite to buy high and sell low. The exact same pattern is happening again“.

Not the only myth

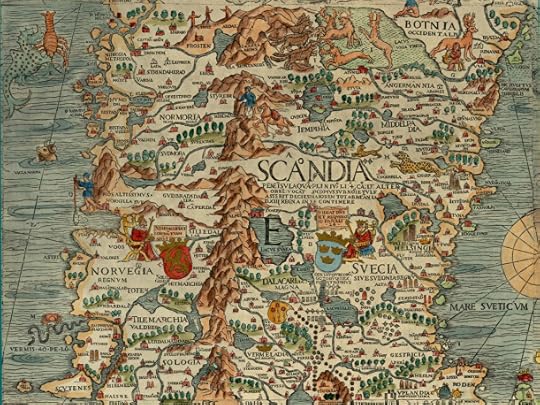

But the suicide myth is not the only one that has attached to lemmings. For a long time they were thought to fall from the sky. In 1555 the Swedish Catholic cleric Olaus Magnus, then exiled in Rome, published in Latin his History of the Northern Peoples (Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus), detailing Swedish history and customs.

About lemmings he wrote: “Quod…in Noruegia…euenit, scilicet vt bestiolæ quadrupedes, Lemmar, vel Lemmus dictæ, magnitudine soricis, pelle varia, per tempestates & repentinos imbres è cœlo decidant“.

(Translation) “Which…happens in Norway, namely that little four-footed creatures, called Lemmar or Lemmus, of the size of shrewmice, with variegated hide, fall from the sky through storms and sudden showers.”

This account was repeated almost verbatim at the word’s first appearance in English, in The historie of four-footed beastes, by Edward Topsell, who was, it seems, much given to plagiarism:

There are certaine little Foure-footed-beastes called Lemmar, or Lemmus, which in tempestuous and rainy weather, do seeme to fall downe from the cloudes.

So, where does the word come from?

The word lemming is, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, borrowed straight from Norwegian, and has not been modified in English. Swedish and Lapp have similar words — lemmel and luomek — and it is possible that the word is related to words meaning “to bark”, such as Latin lātrāre and Lithuanian lōti. Certainly, when they are angry one of the noises they make sounds not dissimilar to the bark of a small dog.

Other Norwegian loanwords

Lemming is not the most common word English has borrowed from Norwegian. Leaving aside the obvious fjord, that honour must surely go to ski, first recorded as a noun in 1755, and as a verb only as late as 1893.

It is interesting that in Norwegian the sk is pronounced sh, the pronunciation reflected in Italian sciare. It was also the English pronunciation Fowler recommended in his 1926 Dictionary of Modern English Usage. Norwegian has also given the skiing world the term slalom, the downhill race, from slalåm, (from sla sloping + låm track).

The Kraken Wakes

The lemming myth mixes fact and fiction, but another Norwegian loanword (1775) plunges us into the world of entirely mythical and terrifying sea creatures: the kraken. This creature was reputedly so enormous that when it dived it created a whirlpool big enough to engulf even the largest ship. Its most famous English incarnation is probably in the title of the 1953 sci-fi novel The Kraken Wakes, by John Wyndham.

It also found its place in 19th century poetry in a sonnet by Tennyson that is somewhat unusual in having fifteen lines rather than the normal fourteen.

Below the thunders of the upper deep;

Far, far beneath in the abysmal sea,

His ancient, dreamless, uninvaded sleep

The Kraken sleepeth: faintest sunlights flee

About his shadowy sides: above him swell

Huge sponges of millennial growth and height;

And far away into the sickly light,

From many a wondrous grot and secret cell

Unnumbered and enormous polypi

Winnow with giant arms the slumbering green.

There hath he lain for ages and will lie

Battening upon huge sea-worms in his sleep,

Until the latter fire shall heat the deep;

Then once by man and angels to be seen,

In roaring he shall rise and on the surface die.

Ouch!

Finally, those who in Scotland are bitten by vicious clegs (i.e. horseflies) will be gratified to know that they have been wounded by an Old Norse beast, kleggi, or klegg in Modern Norwegian.

Filed under: Loanwords, Word origins Tagged: Around the world in 80 words, Norwegian words in English

March 4, 2016

National Grammar Day 2016: Things 7 need about know to you grammar

You mean you didn’t know‽ (I hope that shows up as an interrobang). Well, neither did I, until Twitter alerted me a couple of years ago. Actually, it’s more an American than a British “thang”, started in 2008, by Martha Brockenbrough, founder of The Society for the Promotion of Good Grammar.

What are we supposed to be celebrating?

Before you decide to run into the street dressed as a proper noun, abolish capitals forever like e.e. cummings, or construct grandiose, hugely baroque Dickensian periods for your blog, let’s consider exactly what different groups of people mean by the word “grammar”.

The people who get most animated about National Grammar Day usually think “grammar” is going to the dogs.

What do people mean by “grammar”? What do you mean?

There is a lot of misunderstanding (and occasional antagonism) between people who describe language as it is (i.e. “descriptive” people, especially linguists) and members of the general public who dislike a specific feature of language (e.g. so-called split infinitives, ending a sentence with a preposition).

Some of that misunderstanding is, in my view, simply due to a radically different interpretation of the word “grammar”. Linguists follow a definition that runs something like this:

“The whole system and structure of a language or of languages in general, usually taken as consisting of syntax and morphology (including inflections) and sometimes also phonology and semantics.”

Everyone else follows one that, I suggest, goes something like this:

“A set of actual or presumed prescriptive notions about correct use of a language.”

Interpreted in that way, the word becomes little more than a ragbag into which people can stuff any and every use of language which they object to (or should that be “to which they object”?).

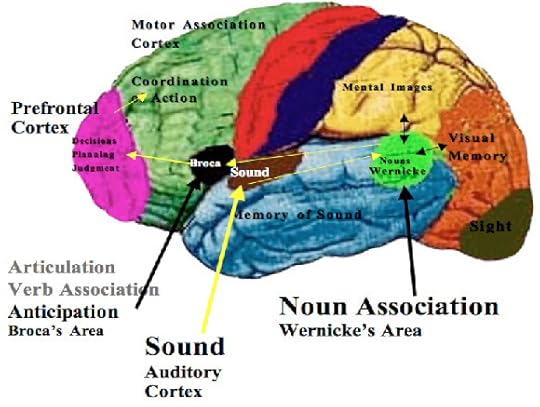

In its technical sense, “grammar” often narrows down to the rules governing how you combine words to make meaningful sentences, the inflections of words (e.g. is the past tense of dive dived or dove?, is the plural of consortium consortia or consortiums?), how verbs behave, what adverbials are, and the like, as illustrated in the graphic above.

You will not find the writers of such eminently readable and practical tomes as the Collins Cobuild English Grammar sneering at someone’s spelling mistake and calling it a “grammatical” error.

The linguistic and technical definition of “grammar”, in fact, excludes most of the things that raise people’s blood pressure.

If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column, above the Twitter feed) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

A tortured grammarian pondering end of sentence prepositions. Well, St Jerome, actually, but he’ll do.

Things 7 need about know to you grammar

You already know enough grammar [i.e. syntax] to untangle that heading. Congratulations!

Feeling that words ending in -ize are taking over the language, or objecting to “verbing” nouns is not “grammar”. Looked at charitably, it is a stylistic choice; uncharitably, it is paranoid prejudice.

Mispelling [sic] a word is not “grammer” [sic]. It is a spelling mistake, which might — or might not — reflect someone’s generally not good spelling. But which of us doesn’t make a spelling mistake from time to time, or have to look up how a word is spelled.

If someone from Yorkshire says “it were”, or someone from anywhere says “I done”, it is not “bad grammar.” It is “non-standard”, but that’s not the same thing.

New words and phrases are neither good nor bad. You can like them or loathe them, but they have nothing to do with “grammar”.

When someone interprets nonplussed to mean “not fussed or bothered”, that too has nothing to do with “grammar”. It is an example of a word being reinterpreted by some speakers, and thus changing its meaning.

If someone pronounces a word in a way you dislike, you dislike it, that’s all. Again, “grammar” doesn’t come into it.

Prescriptive grammar

This broad and non-technical interpretation of “grammar” as being about what people should and shouldn’t do has developed over centuries for many reasons, including as a way of marking social and group identity; of separating in-groups from out-groups.

A quotation from 1892 about aitch-dropping shows how rigorous such demarcations could–and can–be:

“A very fine young man, but evidently a nobody, inasmuch as he dropped his aitches and so on.”

from the Australian novelist “Ralph Boldrewood’s” (real name Thomas Alexander Browne) 1892 Nevermore, . ii. 41.

But, as Terry Eagleton says:

“Dropping your aitches in Knightsbridge probably counts as a deviation, whereas it is normative in parts of Lancashire.”

How to Read a Poem, 2007.

This splendid-looking geezer was never invited to the smartest parties because ‘e dropped ‘is aitches something ruthless. Perhaps that explains the slightly affronted look.

It is reflected in the name of a slightly fascistic current book title “I judge you when you use poor grammar“, which also has a Facebook group. In fact, most of the mistakes its members glote [sic] over are spelling mistakes or choices of the wrong word. This is also true of the Society for the Promotion of Good Grammar website, where we are implicitly invited to sneer at someone who wrote “distinguished the fire” instead of “extinguished the fire“, and similar catachreses (now, there’s a splendid word!). Sadly, this kind of pseudo-grammatical anality is on a par with the prejudices of those Southern Englishers who think that people with, for example, a Yorkshire accent are devoid of grey matter.

A healthful diet is good for you

To illustrate the arbitrariness of some alleged grammar rules, let’s look at just one example of a use which– strangely, at least for a British audience–can give some American copy editors the screaming abdabs. Is it “good grammar” to talk of food, a diet, a lifestyle, as being healthy? Some intransigents and diehards insist that the correct word in those contexts is healthful.

Health-giving turnips offering themselves invitingly to the discerning palate.

The (false) reasoning behind this seems to be that if you define healthy as “in good health” it must, by definition, apply only to people. A turnip cannot–as far as we know, but then we don’t so far speak “turnip”, though perhaps HRH Prince Charles could interpret for us–enjoy rude good health, and therefore another word is required to denote “conducive to good health”. Enter healthful.

In fact, though healthful is the older word, healthy has been used to mean “conducive to good health” since the 16th century. The ban on it dates only to 1881, and has been passed down as an editorial meme ever since then. (Go here to hear the dulcet-toned Emily Brewster of Merriam-Webster setting the record straight.)

The prescription totally ignores a productive feature of English: the transferred epithet , which makes it possible, for example, to apply the word sad not merely to people who feel miserable, but also to the events which give them the blues in the first place. Countless other words behave in the same way; to make an exception of healthy is nonsensical and fetishistic. More to the point, and less emotively, it ignores real English.

The sage of Walden Pond

Back to “grammar”. As regards the second definition I mentioned, it’s worth quoting Thoreau, writing in 1862, when prescriptive grammar held sway:

When I read some of the rules for speaking and writing the English language correctly … I think –

Any fool can make a rule

And every fool will mind it.

When it comes to the specific definition of grammar as our whole language system, we should certainly be celebrating the wonderful ingenuity of human and animal brains in developing it in the first place, and the thousands of ways in which it enriches our experience.

We should also celebrate the fact that all mother-tongue speakers know the grammar of their language, and use it correctly every time they utter, even if they can’t formulate its rules.

Filed under: Grammar, Meaning of words, Topical

March 1, 2016

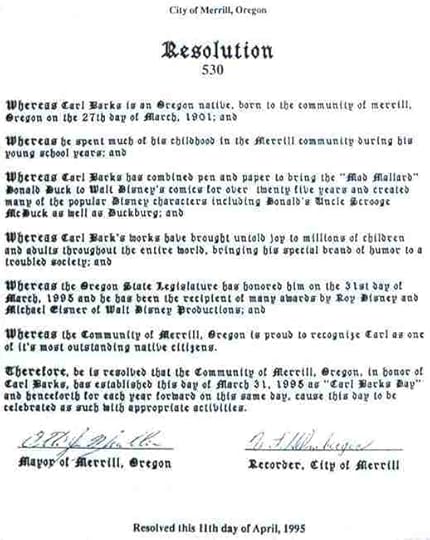

Whereas or where as? One word or two? Commonly confused words (27-28)

Where as???

A while ago, when reading The Times, I was struck by this sentence: “He was apolitical. He [sc. Haider al-Abadi, Iraqi PM] never mentioned Iraq where as some students were vociferous.” Aug 16 2014.

I blogged about it at the time. Since then, that page has become one of the most visited, so I thought I’d update it.

Is it correct to write whereas as two words nowadays?

Short (and long) answer: no.

It had never occurred to me that whereas might be written as two words.

Of course, it could easily be, since it is a simple combination of where and as.

Several “words” are sometimes written as one unit and sometimes as two, for example under way and underway, any more and anymore, and so forth. Sometimes whether you write then one way or the other is simply a matter of house style or regional or personal preference; at other times, the difference can be grammatical, e.g. anymore.

But whereas is not one of those: no current dictionary that I know of accepts the two-word spelling.

A quick check in the Oxford English Corpus (OEC) shows that whereas whereas as a single word appears over 100,000 times—as two words, it’s in the hundreds.

It is impossible to give an exact figure for the latter, because searching for the string where as also finds sentences such as “Wolfowitz joined the bank in 2005 after working at the Pentagon, where as deputy defense secretary he was…”

What is clear, however, is that where as is unusual, i.e. less than one per cent of cases. The OEC data also suggests that it occurs often in news and blog sources (come back subs, all is forgiven!).

Was it ever two words?

Historically, it was originally two words. The earliest OED example is from The Paston Letters (1426-7), in the meaning now largely confined to legal writing, “taking into consideration the fact that”:

Where as þe seyd William Paston, by assignement and commaundement of þe seyd Duk of Norffolk…was þe styward of þe seyd Duc of Norffolk.

(As you will no doubt have worked out, the þ symbol stands for the ‘th’ sound. It was used in Old English, is still used in Icelandic, and is called a thorn since it begins that word.)

In its principal modern meaning (“in contrast”), it first appears in Coverdale’s Bible (1535), also as two words:

There are layed vp for vs dwellynges of health & fredome, where as we haue lyued euell.

(From Book 2 of Esdras, not included in the AV.)

The first OED citation for it as one word is in Shakespeare, Henry VI, Part 1 (written before 1616).

I deriued am From Lionel Duke of Clarence…; whereas hee, From Iohn of Gaunt doth bring his Pedigree.

So, while there are historical precedents for the two-word spelling, whereas is one of those words that current spelling convention decrees should not be sundered.

If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

We’ve seen whereas above used to contrast clauses …

And — as in the Paston Letter quotation earlier — it is often used, especially in US laws, to introduce a clause, or usually several clauses, setting out the reasons for something.

The town of Merrill, Oregon, institutes a Carl Barks day, to honour a Donald Duck cartoonist.

Does it have other meanings?

Yes.

1. Historically, it was used to mean simply “where”, but that use died out long ago, except as a poetic archaism, as illustrated in the second quotation below from the Arts & Crafts designer and writer William Morris:

That..oure heartes maye surely there bee fixed, where as true ioyes are to be founde.

Bk. Common Prayer (STC 16267) Celebr. Holye Communion f. lxiiiiv, 1549.

And quickly too he gat | Unto the place whereas the Lady sat.

W. Morris Earthly Paradise ii. 655, 1868.

2. Whereas is also a noun.

It can mean “A statement introduced by ‘whereas’; the preamble of a formal document.”

While the contrary remains unproved, such a Whereas must be a most inadequate ground for the present Bill.

S. T. Coleridge Plot Discovered 23, 1795.

The rule seems to be that if a candidate can recite half a dozen policy positions by rote and name some foreign nations and leaders, one shouldn’t point out that he sure seems a few whereases shy of an executive order.

Slate.com, 2000.

As a further historical footnote, it is interesting that the legalistic, ritual use of whereas as a preamble to legal documents led to its being used as a noun, defined as follows in the Urban Dictionary of its day, Grose’s 1796 Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue:

To follow a whereas; to become a bankrupt…: the notice given in the Gazette that a commission of bankruptcy is issued out against any trader, always beginning with the word whereas.

Tom Rakewell, from Hogarth’s The Rake’s Progress, narrowly escapes arrest for debt while on his way to Queen Caroline’s birthday party.

Filed under: Advice for writers, Confusable words, Grammar, One word or two?, Spelling Tagged: easily confused words, Hogarth

February 23, 2016

We will not waver, we will not tire. Waver or waiver? Commonly confused words (25-26)

We will not waver; we will not tire; we will not falter; and we will not fail. Peace and freedom will prevail.

With those stirring, rhetorically honed words, President George W. Bush concluded his Address to the Nation on 7 October, 2001, launching Operation Enduring Freedom, in response to the attack on the World Trade Center.

If you search for them on Google, you will often come across “waiver” instead of waver, which highlights the common confusion of the two words.

waiver, waver; waive, wave

Quick “takeaways”

These four words can cause considerable confusion.

To waver is most commonly a verb.

A waiver is a noun, but is quite often wrongly used as a verb.

Occasionally the spelling waver is wrongly used instead of waiver for the noun.

The verbs wave and waive also sometimes get muddled up.

What follows are definitions of these words, and examples with correct or mistaken spelling.

1 waiver vs waver

Definitions & examples

1.1 to waver

If something such as flame or a flag wavers, it quivers or flutters in the air. Related to that idea, but recorded earlier in the OED, is its meaning with regard to people’s feelings, “to be indecisive”, and mental states “to fluctuate; to falter.” Things that typically waver are abstract nouns such as faith, loyalty, concentration, confidence and physical attributes such as voices and smiles. People also waver in or from sentiments like loyalty, determination, beliefs, etc.

TIP: If you think of someone or something wavering, they are as unsteady or changeable as a wave. Or, as the Bible (Authorized Version/King James) puts it:

But let him ask in faith, nothing wavering. For he that wavereth is like a wave of the sea driven with the wind and tossed.

James i. 6

1.1.1 Examples

…a video sequence of candles burning is particularly effective, as it is only when the flame occasionally wavers that the onlooker realises it is a moving image at all.

Architecture Australia (magazine).

Smith’s concentration wavered just enough in the following over.

Times of India.

The House came to a hushed standstill as Burke – voice wavering – told MPs to give it a rest.

The Age, (Austr.).

Despite the problems cited in the assessment, Mr. Karzai has not wavered in his determination to complete the transition by spring, said several officials.

NYT.

1.2 a waiver

A waiver relates to the verb to waive (see 2.1 below) and, according to the Collins English Dictionary, means:

a) the voluntary relinquishment, expressly or by implication, of some claim or right

b) the act or an instance of relinquishing a claim or right

c) a formal statement in writing of such relinquishment

TIP: a waiver is ultimately related to the word waif, as in poor waif, and waifs and strays.

1.2.1 Examples

However, immigration officers have been told they have the discretion to grant a character waiver in cases where it would be “unduly harsh” to decline a visa.

NZ Herald.

The form contained a waiver of parental rights with respect to children resulting from any retrieved eggs.

Findlaw.com, (US).

1.3.1 waiver wrongly used as a verb for waver

The one stakeholder, in fact the largest stakeholder, whose support for strong action on climate change has not X waivered [read “wavered”], is young people, who have the most to lose from inaction. The Age, (Austr.).

“I have been saying for years that many charities are ripe for exploitation due to lack of professionalism and X waivering [read “wavering”] from asking hard questions, and this proves it,” she says. Telegraph.

Andrew Sullivan of “The Daily Dish,” says Clinton will have pleased her supporters but I doubt she will have won over any X waiverers [read “waverers”] or doubters. CNN transcripts.

This misspelling also applies to the derivative waver, i.e. someone who waves a flag.

I’m a third-generation flag X waiver [read “waver”] and a second-generation military brat. Airman (magazine), (US).

1.3.2 waver for waiver

I believe that the US and the European Union have a visa X waver [read “waiver”] agreement. Oz Report.

2 to waive / to wave

Definitions & examples

2.1 to waive

If you waive something such as a fee, a right, privilege or a requirement, you decide not to impose it on someone else, or to make use of it yourself.

2.1.1 Examples

I feel that Amazon should waive the return fee and give me back my inventory.

StartUp Nation, (US).

But there are plenty of examples, plenty of precedents where White House officials have gone to testify before Congress. They have waived that executive branch privilege, if you will.

CNN Transcripts.

Mr Wilson’s interview meant that he had waived his legal confidentiality as a former client of the firm.

Blog, (NZ)

2.2 to wave

It hardly needs saying that to wave generally means to move your hand, or an object held in your hand, to convey a signal or message. Typical things you wave are hands, fingers, flags, placards, banners, handkerchiefs, magic wands, sticks, and swords. You can also wave goodbye or farewell.

TIP: A well-known example from poetry is Stevie Smith’s Not Waving but Drowning, whose first verse runs:

Nobody heard him, the dead man,

But still he lay moaning:

I was much further out than you thought

And not waving but drowning.

Hands reaching above water — Image by © G. Baden/Corbis

2.2.1 Examples

It was his usual rhetorical trick: framing any call to act or lead as a demand to wave a magic wand that he does not have.

Telegraph.

Benedict XVI confidently climbed the stairs of the aircraft, steady enough to not need the handrail, and turned to wave a final farewell to Great Britain.

Guardian.

Haji Mohammad Naim testified in his native Pashto through an interpreter, speaking loudly and quickly and frequently waving a finger in the air.

Telegraph.

2.3.1 waive wrongly used for wave and vice versa

Sometimes people use waive for wave:

… an ocean of Ahmadinejad supporters X waiving [read “waving”] Iranians flags and traditional Shia banners. Guardian, Comment is Free.

More commonly, the mistake is the other way round.

Digital wallet Coinbase is also X waving [read “waiving”] all fees on Black Friday so that Bitcoin users can buy, sell, send and receive Bitcoins all day. Telegraph.

But after finding out that his team had lost, he decided to X wave [read “waive”] his exemption, and stand equal with his other losing team mates. Blog, (Brit.)

3 waver as a noun, and other derivatives of waver

waver can be a noun with some meanings of the verb:

Before Vince came to visit he asked, with a slight waver in his voice, if he’d be meeting my parents this time around. Philadelphia Weekly.

A person who wavers is a waverer (an uncommon word):

Call them the waverers or, worse for Mr. Obama, the drifters: people who provided his comfortable margin of victory in 2008 but are now overcome by doubts about his presidency … NYT.

Other even less frequent derivatives are waveringly, and wavery:

The accrued biographical experience that produces place attachment…appears to help produce such hope (sometimes expressed waveringly by respondents) about a place that is always at risk to disaster. Reconstruction, (US).

… possibly the prettiest song Chernoff has written yet, with his wavery and unsteady vocals rising above a background of acoustic guitar, violin, haunting back-up vocals, … Stylus (magazine), (US).

Origins

To wave comes from the Old English verb wafian, whose Germanic base also gives rise to waver, and is first recorded c. 1000. (The unrelated noun wave, relating to water, is a sixteenth-century adaptation of the earlier form waw or waȝe).

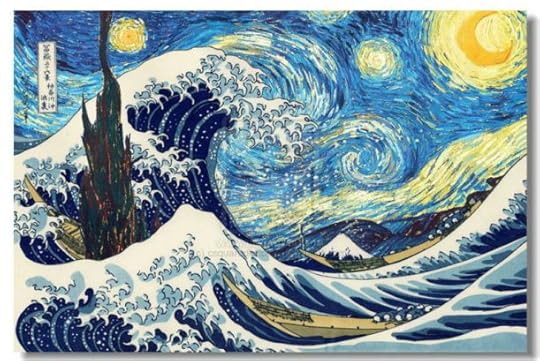

Hokusai, The Great Wave at Kanagawa, from 36 views of Mount Fuji, c. 1829, combined with Van Gogh’s The Starry Night, 1889.

Wave as a noun, meaning an action of waving, is derived from the verb and is first recorded from 1688.

To waive comes from the Anglo-Norman verb weyver, a variant of Old French guesver, “to allow to become a waif, to abandon”, probably of Scandinavian origin.

The noun waiver is either a version of that weyver infinitive used as a noun, or a combination of the verb waive + the -er suffix.

To waver comes from Middle English waver, wever, related to Old English wǣfre, “restless”.

As a final verbal image for wave — though not the wave we’ve been talking about so far, so this is a bit of a cheat — here are some lines from Matthew Arnold’s Dover Beach (1867)

Listen! you hear the grating roar

Of pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling,

At their return, up the high strand,

Begin, and cease, and then again begin,

With tremulous cadence slow, and bring

The eternal note of sadness in.

William Dyce (1806-1864) Pegwell Bay, Kent – a Recollection of October 5th 1858. (?1858-60). Tate Britain.

Filed under: Advice for writers, Confusable words, Meaning of words, Poetry Tagged: President Bush

February 6, 2016

home in or hone in? Both right? Commonly confused words (3-4)

Which of these two sentences do you think is correct?

A teaching style which homes in on what is important for each pupil.

Or

A teaching style which hones in on what is important for each pupil.

Where you live in the English-speaking world will affect your opinion.

Which also means that whichever version you use, someone somewhere is likely to consider it wrong. (And if they are of the “grammar” pedantry persuasion, to take great delight in doing so.)

(But if you are not a British English speaker, the chances are that you’ll plump for the second one.)

A handful of examples

Home

Once again the media homed in on Tyrannosaurus.

American Scientist

DRUG dealers were today warned that the police were homing in on them after a man caught with drugs worth £26,000 was sentenced to six-and-a-half years in jail.

Bolton Evening News (UK)

Unfortunately, many Twitter users homed in on an Alan Joyce of Stanford, California. The American acquired more than 300 extra Twitter followers in the past 24 hours after tweeters confused him with the Qantas boss.

New Zealand Herald.

Hone

The writer Malcolm Hulke really seems to be honing in on the anxieties of the time, by focusing on the pollution of the planet and leaving the earth uninhabitable.

The Independent blog (UK).

Yes, they had those rhetorically brilliant 1858 debates, but the election of 1860, waged in a fiercely divided country, also honed in on the candidates’ appearances [sic].

Boston Globe.

Therefore, we hope to initially hone in on some sightings of Raja [sc. an animal] by villagers of the area.

Sunday Times (Sri Lanka).

Tapas menu

Hone in seems to be as widely used as home in, if not more widely.

If you use it, you are in the majority, but several reputable sources view it as a mistake.

For many people, however, it is the only correct version, and makes sense semantically.

Both phrasal verbs can be seen as “skunked”, i.e. they will offend someone’s linguistic sense of smell, so they might be best avoided.

There is an argument that hone in is a separate development, not a mistake.

Users of each version can easily find justifications for them – specious or otherwise, selon votre goût.

À la carte menu

Read on …

Take Our Poll

Worldwide, more people use hone in than home in.

A US copywriter spotted “home in” in a blog of mine, and kindly pointed out what she thought was a typo. She was surprised when I told her it was intentional. In a straw poll in her office – this was in the US, remember – everyone agreed hone was the only correct version.

Mrs Malaprop, looking rather splendid.

That surprised me. I was familiar with the “home in” version, whose meaning has always seemed self-evident to me: I think of a homing pigeon returning to a specific place, or a missile homing in on its target, and therefore to home in on something is to target it or pinpoint it (or, as the ODO definition goes, “Move or be aimed towards (a target or destination) with great accuracy“).

Consequently, as a British English speaker, I have occasionally winced when, for example, British HR-obots talked about “honing in on” a particular point or issue. Shurely shome mishtake, I thought, a misinterpretation, a malapropism, an eggcorn.

I first posted on this topic about 18 months ago, and since then, having looked at more data, I am obliged to change my mind. For it seems that the home in version is a) less frequent across all varieties of English and b) shows signs of being ousted even in British English by the hone in version.

Some figures

The figures I mention do not show exactly the same picture. Nevertheless …

1 I looked in the Oxford English Corpus (OEC), which consists of about 2.6 billion words of data from US, British and several other varieties of English. (Or, to indicate its vast size another way, over 112 million sentences of English.)

I looked for in + on after the lemmas home and hone (i.e. all forms, home, homes, homed, homing). Overall, hone in on is slightly more frequent, with 700 instances against 655.

Looking at regional variation within those figures gives us this table:

Regional variety

home in on

hone in on

British English

283

67

American English

254

419

unknown

57

69

Australian English

16

37

Irish English

13

47

South African English

8

6

New Zealand English

6

12

East Asian English

6

8

Canadian English

5

30

Indian English

4

3

Caribbean English

3

2

TOTALS

655

700

Only in British (and three other varieties, with very low figures, also italicized) is home commoner. The ratio in BrE of home: hone is 80.9:19.1%.

Outside US and Canadian English, the highest ratio of hone: home is in Irish English (78.3:21.7%).

For the US, the ratio is 62.3:37.7%, and for Canada it is 85.7:14.3%.

2 Looking at the Global Corpus of Web-Based English (GloWbE, pronounced “globe”, 1.9 billion words from 1.8 millon web pages) produces rather different results.

Across all 20 varieties of English covered, hone greatly outnumbers home: 786 vs 283 instances.

The figures below show figures for US, Canadian and British English.

All

US

CAN

GB

HOMING IN ON

122

29

3

45

HOMED IN ON

115

20

7

37

HOMES IN ON

29

3

1

13

HOME IN ON

17

2

1

8

TOTAL

283

54

12

103

ALL

US

CA

GB

HONE IN ON

411

124

42

73

HONING IN ON

154

42

20

31

HONED IN ON

145

43

14

27

HONES IN ON

76

20

5

12

TOTAL

786

229

81

143

The ratio of hone:home for the US is higher still than in the OEC (81:19%), while for Canada it is very similar. For Britain, however, the figures are completely reversed in favour of hone: 58.1:41.9%.

In all other varieties, hone wins.

3 Google books Ngrams shows the lemma home + in on as more frequent than hone + in on, e.g. for the string home in on 10 occurrences per million words in 2000 vs 3 per million in 1999 for hone in on. It also shows a steep rise from the 1970s onwards.

(If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column above the Twitter feed) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!)

But hone in on just doesn’t make sense! It’s obviously a crass mistake!!

Mmmmm. It clearly does make sense to very many people, including George Bush.**

For it to be a mistake, it would have to be clear that home in on was well established before the arrival of hone in on . That is not indisputably so, as Mark Liberman suggested in some detail a while ago.

The sense development of home in on is fairly clear (see OED citations at the end), but what of hone in on ? After all, the core meaning of hone is “to sharpen a blade” (1788), so what has that got to do with “focussing on something”?

Showing the word’s metaphorical extension, the second OED definition of hone is “To refine or practise (a skill, technique, etc.); to make more effective or intense.” The first example in this category is from 1914, but then the next one is from 1955, and the OED notes “Before the mid 20th cent. usu. as part of an extended metaphor”. This is only ten years before the first appearance of hone in.

Well, as regards going from “sharpening” to “focussing”, Grammarist suggests this: “Hone means to sharpen or to perfect, and we can think of homing in as a sharpening of focus or a perfecting of one’s trajectory toward a target. So while it might not make strict logical sense, extending hone this way is not a huge leap.”

Judging by some online comments, some people even see a meaning distinction between the two forms: “’home in’ and ‘hone in’ do not mean the same thing. They have similar but distinct meanings. ‘Home in’ means to get closer to like a missile homing in on its target, while ‘hone in’ means to pay close attention to or listen to something.”

Mark Liberman suggests in detail a development I shall summarize like this:

hone (down) X = “improve X by sharpening focus on the essentials and eliminating or ignoring extraneous materials” –> hone in on Y = “reach Y by a process of successively sharpening focus while eliminating extraneous material.”

What do dictionaries and usage guides say?

A couple of dictionaries list hone in on with no comment, but several others consider it a mistake.

Several style guides take that same view; some set great store by the physical meaning of hone, in a way that comes close to being the etymological fallacy.

Oxford Dictionaries Online in both World English and US versions notes at home in on that hone is quite common in mainstream US writing, but that many people still consider it a mistake, as do Collins and freedictionary.com. Macmillan lists it with no comment.

The OED makes no bones about calling hone in the result of “folk etymology”.

My revised (4th) edition of Fowler’s Modern English Usage covers similar territory to this blog more briefly, but suggests avoiding either word altogether.

Merriam-Webster notes the existence of hone in and suggests that it “seems to have become established in American usage”. The American Heritage College Dictionary (2004) gives “to direct one’s attention; focus” as a meaning of hone in.

Garner’s Dictionary of Legal Usage, however, considers it unequivocally wrong.

The Guardian style guide notes, somewhat acidly, “home in on, not hone in on, which suggests you need to hone your writing skills.” Neither The Economist nor The Telegraph guides mentions it.

The Chicago Manual of Style, 16th edn, notes: home in. This phrase is frequently misrendered hone in. (Hone means “to sharpen.”) Home in refers to what homing pigeons do; the meaning is “to come closer and closer to a target.”

The Merriam-Webster Concise Dictionary of English Usage charts the development of hone in on, but notes that “If you use it, you should be aware that some people will think that you have made a mistake.”

Various online grammar sites also castigate hone in on as a mistake for home in on. One site (Grammarist), which is more permissive, attracted 57 tetchy and not so tetchy comments, mostly against hone in on.

So…? What should I do?

The hone in variant has been around for half a century. It is used in many parts of the Anglosphere. As discussed, some dictionaries list it without comment, while others warn against it, as do many usage and style manuals.

If you use it, you are unlikely to be misunderstood. However, if you do use it, bear in mind that some people will consider it a mistake, and therefore conclude that you can’t use English “correctly”. And others will come to the same conclusion if you use home in.

To steer clear of the problem, why not use focus on, concentrate on, zero in on, or any other synonym that suits your context?

** From Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary of English Usage. “An issue looming on the usage horizon is the propriety of the phrase hone in on. George Bush’s use of this phrase in the 1980 presidential campaign (he talked of ‘honing in on the issues’) caught the critical eye of political columnist Mary McCrory, and her comments on it were noted, approved, and expanded by William Safire. Safire observed that hone in on is a confused variant of home in on, and there seems to be little doubt that he was right. . . . Our first example of home in on is from 1951, in a context having to do with aviation. Our earliest record of its figurative use is from 1956. We did not encounter hone in on until George Bush used it in 1980. . . .”

*** OED definitions / earliest citations. (Italics in examples mine.)

HOME

a. intr. Of a homing pigeon: to fly back to its ‘home’ or loft after being released at a distant point; to arrive at the loft at the end of such a flight. Hence of any animal: to return to some specific territory or spot after having left it or having been removed from it. Freq. with to.

1854 Poultry Chron. 1 573/2 It is generally considered that a cock [pigeon] homes quickest when driving to nest, and a hen when she is feeding squabs.

…

intr a. Of a vessel, aircraft, missile, etc.: to move or be guided to a target or destination by use of a landmark or by means of a radio signal, detection of a heat signature, etc. Usu. with in on, or less commonly on, on to, or towards. Cf. hone v.4

1920 Wireless World Mar. 728/2 The pilot can detect instantly from the signals, especially if ‘homing’ towards a beacon.

1947 J. G. Crowther & R. Whiddington Sci. at War 119 Torpedoes and bombs that follow or ‘home’ on to their targets.

1968 Galaxy Mag. Nov. 107/1 The only way another ship could get here would be to home in on the drone that our Line ship homed in on.

…

NB: the previous version of the entry had a 1956 US citation for home in on, in the physical sense.

b. fig.To make something the sole object of one’s attention; to focus intently on something. Cf.hone v.4

1955 C. M. Kornbluth Mindworm 53 That was near. He crossed the street and it was nearer. He homed on the thought.

1971 New Scientist 16 Sept. 629/1 Mexico’s Professor S. F. Beltran homed in on education as a critical need.

…

HONE4

It should be noted that this is a new 3rd edn entry from 2004, which treats hone here as a homograph of hone3 with its meaning of “to sharpen.” I think previously both were grouped under the same headword.

Etymology: Apparently a variant or alteration of another lexical item. Etymons: home v.

Apparently an alteration of home v. (see home v. 5a), probably arising by folk-etymological association with hone v.3

orig. U.S.

intr. to hone in: to head directly for something; to turn one’s attention intently towards something. Usu. with on. Cf. home v. 5a.

1965 G. Plimpton Paper Lion vii. 62 Then he’d fly on past or off at an angle, his hands splayed out wide, looking back for the ball honing into intercept his line of flight.

1967 N.Y. Times 5 Nov. iii. 10/1 A few who know the wearer well recognize that something is different without honing in on the hairpiece.

…

Filed under: Advice for writers, Confusable words, eggcorns, Grammar Tagged: American Writing, easily confused words

January 31, 2016

A coruscating attack, review, etc. Or excoriating? Commonly confused words (1-2)

If you read that so-and-so-A has made a “coruscating attack” on so-and-so-B (or so-and-so-B’s work), what do you take it to mean?

For instance:

The report is a coruscating attack on the Government’s welfare reforms and those of its coalition predecessor.

Sunday Express, 29 December 2015.

These three options suggest themselves: a) search me, guv; b) oh, A is tearing into B like nobody’s business; c) A is an ignoramus, and what they actually meant was “an excoriating attack”.

A while back, The Guardian’s Corrections and clarifications column plumped firmly for option c):

“In the following article, Terry Eagleton’s ‘corruscating [sic] review’ of Richard Dawkins’s book The God Delusion may have been withering or possibly even acidulous.”

The Guardian style guide is categorical about the matter:

“coruscating means sparkling, or emitting flashes of light; people seem to think, wrongly, that it means the same as excoriating”.

The Economist style guide notes (with bold items as shown) that: This means sparkle or throw off flashes of light, not wither, devastate, or reduce to wrinkles (that’s corrugate).

You’re unlikely to hear either word in everyday conversation, far less down the pub (unless it’s a pub frequented by lexicographers, journalists, or usage pundits). Both are rare, and typical of arty or journalistic writing.

“Takeaways”

Coruscating is occasionally used in a small number of phrases in what looks like confusion with excoriating.

The lemma to excoriate and its derivatives are about five times more frequent than coruscate.

Coruscating as an adjective is more frequent in British English than elsewhere, as are its collocations with attack and semantically similar words.

A Google search for “coruscating attack” and “excoriating attack” shows the second – the “correct” one – in a ratio of 4.7:1 to the first.

coruscating

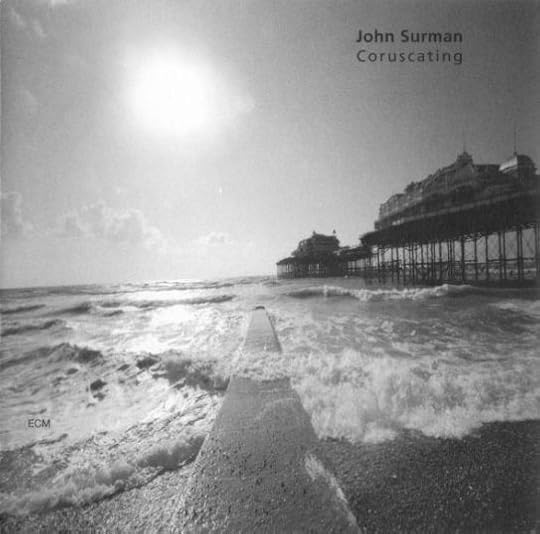

Album cover for jazz giant John Surman. Copyright ECM or original graphic artist

Meaning and examples

Coruscating can be a bit of a journalistic trap. British hacks in particular sometimes light on it in order to embellish their prose, occasionally with scant regard for its meaning.

It derives from the Latin coruscāre in its meaning of “to flash, glitter, gleam”.

“Glittering” or “sparkling”, literally or metaphorically, is what it usually means in English. Merriam-Webster has a pithy definition for the metaphorical use: “to be brilliant or showy in technique or style.”

Coruscating is the participial form of the verb to coruscate, but the verb itself is rather rare. (In fact, according to the OED, the word was first recorded in this participial form, in 1705.)

The Oxford Online Dictionary labels the verb as literary, and includes the following example:

Finally, as the blazing star appeared high over the island, the glow coruscated into incredible brilliance and began the nightly display.

Nouns typically described as coruscating are wit, brilliance, a review, a performance, a display, and an attack.

The Oxford English Corpus data suggests that it occurs with less than expected frequency in US English, and with higher than expected frequency in BrE.**

She preserves the steely delicacy and coruscating wit of Wilde’s writing.

Sunday Times.

… a complete understanding of the resources of the instrument and an acute ear for contrast allowed Liszt to produce a quasi-orchestral palette of tone-colours, lending a coruscating brilliance and variety to both his original music and his transcriptions.

Oxford Companion to Music.

Oops, did I chose the wrong word?

Examples like the previous reflect the core meaning of the word, but what are we to make of its use in these examples?

… the anthropologist and writer John Ryle wrote a coruscating review essay in the Times Literary Supplement , documenting numerous inaccuracies , exaggerations and mythifications in Kapuscinski’s writing on Africa. Guardian, Comment is Free.

Departing SNP leader John Swinney yesterday delivered a coruscating attack on the tormentors within his own party who he claimed had made it impossible for him to continue in office. Scotland on Sunday.

In those contexts it is obviously intended to mean “scathing”, “ferocious” and the like. They seem to be a mistake for the less rare but equally Latinate adjective excoriating.

(If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!)

excoriate / excoriating

Origins, meanings, examples

While the verb has been used in English to mean “to strip the skin off someone”, i.e. flay them, it has a specific modern medical meaning, “to damage or remove part of the surface of the skin” (images for which I’m too squeamish to show).

It comes from the Latin excoriāre to strip off the hide, ex- out + corium hide>, and the OED*** dates its first occurrence to 1497, in a work published by Wynkyn de Worde.

The flaying of St. Bartholomew. Rome. 3rd quarter 16th century, cutting from a collectar. In the style of a Croatian artist – which may explain why the Romans look curiously oriental, with their splendid mustachios.

Clearly, if you can excoriate someone physically, that is, flay them, you can also do so metaphorically (lambast similarly developed from physical to figurative, and think of “to roast someone or something” in a figurative sense, e.g. This is a movie whose brain belongs in its pants, and which deserves to be roasted for the turkey it truly is.)

The OED defines this non-physical meaning of to excoriate as “upbraid scathingly, decry, revile” and dates its first occurrence to 1882:

How he [sc. Jackson] would excoriate Tilden for his copperheadism.

NY Tribune, 15 March 1882.

Here are current examples of the verb:

Critics excoriating him for other aspects of his film show an equal lack of sensitivity to the challenges that come with highly structured storytelling.

Bright Lights Film Journal, (US).

Talk shows were excoriated in the media and featured in countless political cartoons of the period.

Art Journal, (US).

Excoriating … is the participial adjective from the verb. The adjective typically qualifies attack(s), a crique, a report, criticism, or an editorial.

Throughout the second world war, Aneurin Bevan subjected the line of the Churchill coalition government to excoriating criticism and withering examination …

Sydney Morning Herald Web Diary.

Two coroners launched an excoriating attack on the lack of basic equipment in the Armed Forces yesterday, blaming poor resources for contributing to the deaths of three soldiers in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Telegraph.

Although E. P. Thompson has not been alone in objecting to the work of Louis Althusser, it is nonetheless within his excoriating critique in The Poverty of Theory that one witnesses a prolonged attack on the perceived errors of the French intellectual’s abstract structuralism.

Capital and Class, (US).

A British English issue?

It is worth noting that of those collocations listed above for excoriating, over three-quarters are British English (78%). In other words, those collocations are possibly better known in BrE than elsewhere. That might explain why the confused coruscating ?attack and ?review seem also to be peculiarly British: 80% of examples.

Is this a recent phenomenon?

It seems not. Good ol’ Ngrams throws up an example of coruscating attack from a 1961 Report to the Fellows, Pierpoint Morgan Library, p. 59. However, it also shows a vertiginous rise in frequency of that collocation between 1981 and 2000.

Why are the two confused?

I don’t know, but here are some thoughts. If one were to be uncharitable, “Ignorance, Madam, pure ignorance” as Dr Johnson is reported to have said, would be the reason. Viewed in that light, “coruscating” becomes a malapropism of the “allegory on the banks of the Nile” kind.

But that won’t entirely do: the alternation cannot be arbitrary or random.

First, though clearly miles away from being homophones, they share both an -ating element and a Latinate sound –but, admittedly, not the same number of syllables.

Second, if someone has seen the phrase “coruscating review”, but not read the review in question, how would they know what the phrase meant? Reviews are often negative, so assigning a negative meaning to coruscating as a word to describe a review does not seem unreasonable. In any case, for many reviewers, the bitchier the review the more brilliant it is, at which point coruscating and excoriating easily begin to merge.

Google Ngrams also brings a tantalizing clue to the origin of the crossover – on the basis of sounds.

I could only retrieve this fragment:

On the basis of shared sounds, I had associated ‘coruscating’ with ‘corrosive’ and ‘excoriate’ when it means to flash, like lightning. Hence a coruscating review will be brilliant, but not necessarily cutting.

Australian Book Review, Issues 108-117, 1989.

Overall, it might be worth considering using a synonym to replace either word – there’s no shortage of them –, such as blistering, devastating, scathing, withering, savage, caustic, vitriolic, and whatever else your thesaurus suggests.

A “skunked term” is Bryan Garner’s phrase for a word or phrase whose alleged misuse will annoy purists. I suspect that for a (rather small) number of people, “coruscating” for “excoriating” will indeed exude the rank smell of error.

** GloWbE (The Corpus of Global Web-Based English) tends to confirm this. While average frequency across 20 countries is 0.06 occurrences per million words, in US English that figure is 0.03, but in British it is 0.14.

*** Interestingly, this meaning of “mercilessly criticize” was not recorded by the original OED editors in their 1894 entry. The 1993 draft revisions show the verb first used in the “attack” meaning in 1882, and the adjective in 1884. Presumably it was, therefore, too recent to have attracted the attention of the original compilers

**** “When a word undergoes a marked change from one use to another–a phase that might take ten years or a hundred–it’s likely to be the subject of dispute. Some people (Group 1) insist on the traditional use; others (Group 2) embrace the new use, even if it originated purely as the result of word-swapping or slipshod extension. Group 1 comprises various members of the literati, ranging from language aficionados to hard-core purists; Group 2 comprises linguistic liberals and those who don’t concern themselves much with language. As time goes by, Group 1 dwindles; meanwhile, Group 2 swells (even without an increase among the linguistic liberals).

“A word is most hotly disputed in the middle part of this process: any use of it is likely to distract some readers. The new use seems illiterate to Group 1; the old use seems odd to Group 2. The word has become ‘skunked.’ . . .

“To the writer or speaker for whom credibility is important, it’s a good idea to avoid distracting any readers or listeners–whether they’re in Group 1 or Group 2. Thus, in this view … is now unusable: some members of Group 1 continue to stigmatize the newer meaning, and any member of Group 2 would find the old meaning peculiar.”

Bryan A. Garner, Oxford Dictionary of American Usage and Style, 2002.

Filed under: Advice for writers, Confusable words, Meaning of words Tagged: easily confused words

January 11, 2016

peek, peak or pique. It piqued my interest or peaked my interest? Take a peek or peak? Commonly confused words (23-24)

Since all three words sound the same and all work both as nouns and verbs, it is perhaps inevitable that people sometimes muddle them up.

Quick definitions & examples

peak

A peak is the highest point of something, either physically or metaphorically, and if something peaks, it reaches its highest point:

Colors feel appropriate as well, from the brilliant white of snow-capped peaks to the deep blues in shots of water.

DVD Verdict.

Urban renewal has been in practice in the industrialized nations since the 1800s, but it hit its peak in the 1940s and 1950s.

Blog.

In the Nielsen poll, Mr Abbott’s personal popularity peaked more than two years ago and the longer-term trend has been down.

The Age (Aus).

peek

A peek means “a quick or furtive look” and if you peek, you “look quickly or furtively into or at something”. By extension, if something peeks out of something, it emerges or pokes out from it.

Security is tight and few are prepared to let outsiders peek inside.

Scotland on Sunday.

She gets her hair cut at the Muslim-owned beauty shop upstairs; she hands candy to the Somalian children who peek shyly in her store.

Boston Globe.

She noticed snowdrops peeking up through the grass beneath the trees, and pussy willows furring the hedge.

Source unknown.

“They’d push them across the table and say, ‘You might want to take a peek at this,'” he said.

NYT.

pique

Pique is a feeling of irritation or sulkiness resulting from a perceived slight, and, more rarely, means a quarrel; if something piques your curiosity, interest, appetite, and the like, it arouses it, and if you feel piqued, you feel resentful. In a rarer meaning, if you pique yourself on something, you take pride in it.

Among those in the audience was Ed Miliband, whose intellectual curiosity was piqued.

New Statesman.

“You don’t have to lecture us, Lizzy “, Kitty said, somewhat piqued.

Date & source unknown.

Yet right and left alike pique themselves on this imbecile prejudice.

Guardian, Comment is Free.

At the same time—and perhaps not illogically—she piqued herself on her talent for bedroom diplomacy , working hard to persuade the President to place women in important posts.

Telegraph.

…the Champ, after all, had once hurled his Olympic gold medal into the Ohio River, in a fit of pique at some alleged racial insult in Louisville.

Believer Magazine.

Is the Attorney-General motivated by pique rather than by principle, and has she seriously considered her motives in bringing this case forward?

New Zealand Parliamentary Debates, 2004.

Linguistic explanations?

Probably, deep down in our mental lexicons we have all stored this knowledge about these words, but in writing it is all too easy to bang down the wrong one.

Some cases may be eggcorns. For example, as the eggcorn database points out, a phrase such as “to peak someone’s interest” can be interpreted as a causative use of peak, that is, it means “to cause someone’s interest to peak”, just as “to walk the dog” means “to cause the dog to walk.” Similarly, if the “sun peaks over the horizon”, the image could plausibly be of the sun moving towards its zenith.

That said, however, editors and alert readers will still regard the use of one spelling for the other as a mistake, and such use is not legitimized by dictionaries. The Merriam-Webster Concise Dictionary of English Usage sagely advises:

“A writer needs to keep the meaning in mind and match it to the correct spelling.”

And in some cases, e.g. “peek someone’s interest”, it is difficult to think of a convincing semantic explanation.

Peak wrongly used

The main villain of the piece seems to be peak, perhaps because it is the most common lemma of the three. It often replaces peek (noun) in the collocations to have a peek, to sneak a peek, to take a peek.

A Google search for “take a peek” in inverted commas throws up 14,600,000 results. It often seems to be used as a trite advertising trope, to titillate, tease, and tantalize the reader (That’s enough alliteration! – Ed) and make them imagine they are enjoying the privilege of an advance or exclusive look at something special, e.g. “Take a peek into the life of a nanny to the super rich / into X’s exclusive Chelsea Home/ into the new [fill in as appropriate]”. (Pass the sick bag, please.)

Searching for “take a peak” also throws up vast numbers. Some are deliberate puns (e.g. “Take a peak: fun new places to stay in European ski resorts”), but many are instead of the peek spelling: “Take a peak through the keyhole of three beautiful festive homes” [read “peek”] (This appeared in the online version of a newspaper on 18 December.)

Other examples from the Oxford English Corpus include:

That means no sneaking a peak [read “peek”] at work emails from outside the office, even if they are expecting non-work messages. Telegraph.

While one distracts a guard’s attention, the second – while pretending to be on the phone – can take a peak [read “peek”] at the guest list and get some names which they can then use. Telegraph, 2009.

With the verb such substitution seems less frequent, but does occasionally happen, e.g. I kept peaking [read “peeking”] at my watch. Blog.

Peak as a verb is also used where pique is correct, as in the next two examples.

It peaked [read “piqued”] my curiosity enough to buy the CD today during lunch. Blog.

Two aspects of Hox genes have peaked [read “piqued”] the interest of phylogeneticists. American Zoologist.

TIP: A good grammar/spellchecker should pick up these confusions.

TIP: If you’re British, think of the Peak District, i.e. an area of high summits. (You will also find this spelled wrong, but it is not very common.)

History

Peak…

as a noun has an immensely convoluted etymology, as the OED explains, deriving ultimately from the Old English word piic, meaning a pickaxe, or pick for breaking up the ground. It was first used to refer to the pointed summit of a mountain in the early 17th century. Its metaphorical use to refer to the zenith or highest point of something is late-18th century. The verb use “to reach a peak or highest point”, e.g. prices, floods, etc., is modern: the first OED citation is from 1937.

peek

This started life as a verb in the 14th century (the OED defines it as “To look through a narrow opening; to look into or out of an enclosed or concealed space; (also) to glance or look furtively at, to pry.”), and possibly derives from the word of similar meaning to keek.

(The OED points out the similarity of peek to peep and peer, words with the same/similar meanings Remembering that might help with spelling).

It became a noun by the common process of conversion, i.e. using an existing word in a different part of speech category, a use first recorded by the OED from 1636.

pique

attributed to Hans Holbein the Younger, watercolour and bodycolour on vellum, circa 1532-1533

As its spelling might suggest, this word comes from French: from the Middle French word pique, meaning “quarrel, resentment”, which in turn comes from the verb piquer, “to prick, pierce, sting”.

The OED first records the noun in a letter of 1532 by Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII’s chief minister. (This portrait makes it look as if an expression of slight pique was natural for him.)

The verb is first recorded in 1664.

(You will also find the spelling pique for piqué, a type of stiff cotton fabric.)

The three words discussed become incestuously entangled in all sorts of ways, as the following examples demonstrate. If you want to try correcting them, the answers are shown at the end.