Jeremy Butterfield's Blog, page 30

October 12, 2014

English Language Day 2014: Let the Bells ring out.

English Language Day was inaugurated by The English Project in 2009 as a way of celebrating this quirky and wonderful language of ours. As their site says, the Project ‘promotes awareness and understanding of the unfolding global story of the English language in all its varieties’.

Why today?

Because of a nice little historical anecdote. It was on 13 October 1362 that the English Parliament was opened for the first time by a speech in English.

A language layer cake?

Where does English come from? One way to think of English is as a layer cake. The bottom layer, which gives us many of our most basic everyday words, is Old-English, also known as Anglo-Saxon (1). On top of that are luscious thick layers of French, Latin, and Greek words, and then the icing on the cake is made up of words borrowed from dozens and dozens of other languages, from Welsh (corgi) to Chinese (kowtow), and Inuit (anorak) to Hawaiian (wiki-).

Where does English come from? One way to think of English is as a layer cake. The bottom layer, which gives us many of our most basic everyday words, is Old-English, also known as Anglo-Saxon (1). On top of that are luscious thick layers of French, Latin, and Greek words, and then the icing on the cake is made up of words borrowed from dozens and dozens of other languages, from Welsh (corgi) to Chinese (kowtow), and Inuit (anorak) to Hawaiian (wiki-).

The Latin layer.

(Or stratum, to use a Latin word.)

Latin has given us much of our abstract and literary vocabulary. As today is Sunday, and the bells of York Minster have been tolling clangorously in the background as I blog, I want to look at one that could hardly be more literary: tintinnabulation. Not a word you’ll come across every day, admittedly, but an interesting one all the same.

It means, as the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) defines it: “A ringing of a bell or bells, bell-ringing; the sound or music so produced”.

It is a combination of the Latin tintinnābulum “tinkling bell” and the suffix -ation (which is itself from Latin). Tintinnābulum sounds rather like what it means (“tinkling bell”): in other words, it is onomatopoeic (a Greek word). Its onomatopoeia (note the difficult -oeia spelling) is not surprising, since it in turn comes from the Latin tintinnāre (“to ring, jingle”), which is what is called a “reduplication” (2) of tinnīre, the Latin verb also meaning to ring (from which comes the name of the medical condition tinnitus.)

Who first used the word?

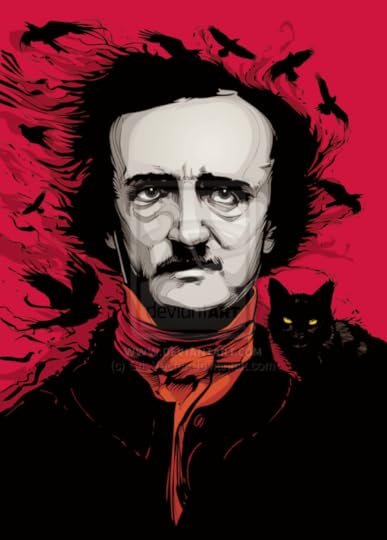

According to the OED, the word first appeared in print in Poe’s poem The Bells, which is about as onomatopoeic or echoic as it gets, with its almost manic repetitions of “inkle” and “el” sounds, and of the long “i” sound of icy, night, etc.

The Bells!

Hear the sledges with the bells -

Silver bells!

What a world of merriment their melody foretells!

How they tinkle, tinkle, tinkle,

In the icy air of night!

While the stars that oversprinkle

All the heavens seem to twinkle

With a crystalline delight;

Keeping time, time, time,

In a sort of Runic rhyme,

To the tintinnabulation that so musically wells

From the bells, bells, bells, bells,

Bells, bells, bells -

From the jingling and the tinkling of the bells.

The words does not, for obvious reasons, get too many outings. However, it was a key notion for “Holy Minimalist” composer Arvo Pärt at a certain stage of his musical development which gave birth to pieces such as Für Alina and the hypnotically serene Spiegel im Spiegel.

‘Tintinnabulation,’ the composer explains,’is an area I sometimes wander into when I am searching for answers—in my life, my music, my work…Traces of this perfect thing appear in many guises—and everything that is unimportant falls away. Tintinnabulation is like this. Here, I am alone with silence. I have discovered that it is enough when a single note is beautifully played…I work with very few elements—with one voice, with two voices. I build with the most primitive materials—with the triad, with one specific tonality. The three notes of a triad are like bells. And that is why I call it tintinnabulation.’

(1)The only words in that paragraph not from Old English are: cake (Scandinavian), basic (ultimately Latin), luscious (probably from delicious, therefore French, as are language and dozen).

(2) Reduplication is a repetition of (a syllable or other linguistic element) exactly or with a slight change. English is full of these reduplications, e.g. hocus-pocus, hurly-burly, pitter-patter, see-saw, willy-nilly).

Filed under: Dictionaries & Lexicography, Meaning of words, OED, Word Histories

October 1, 2014

Spanish loanwords borrowed by English: alligators and cockroaches

BOTH ARE LOANWORDS

What is a loanword? It sort of does what it says on the tin. It is a word one language loans or lends to another (though the lender doesn’t usually get it back, and no interest is paid). And the word loanword is itself a loan translation, purloined from German Lehnwort.

English is full of loanwords, as are most, if not all, European languages.

BOTH ARE FROM SPANISH

Our alligator combines the Spanish word for “lizard” lagarto, and the Spanish definite article el “the”. So, if you run the two together you get elligarto, which eventually was standardized as alligator, though previously spelt in at least a dozen different ways.

The word first appeared in its Spanish form lagarto in translations into English in the second half of the 16th century.  It made an early appearance in Romeo and Juliet, when Romeo is describing an impecunious apothecary’s shop:

It made an early appearance in Romeo and Juliet, when Romeo is describing an impecunious apothecary’s shop:

And in his needie shop a tortoyes hung, An allegater stuft, and other skins Of ill shapte fishes, and about his shelves…

That is the spelling in the 1599 Quarto; in the 1597 Quarto it is Aligarta, which illustrates just how indeterminate the spelling originally was.

In the first half of the 17th century we find Sir Walter Raleigh  and Ben Jonson still using the more Spanish spelling: Alegartos and Alligarta respectively. So why did the letters rt of that final -arto or -arta get swapped round to -ator? The OED suggests that it was by association with the agent suffix -ator, found in administrator, imitator, and so on.

and Ben Jonson still using the more Spanish spelling: Alegartos and Alligarta respectively. So why did the letters rt of that final -arto or -arta get swapped round to -ator? The OED suggests that it was by association with the agent suffix -ator, found in administrator, imitator, and so on.

This change of form suggests the influence of folk etymology: the process by which people change the shape of a strange, unfamiliar word to make it fit in with a more familiar word or pattern.

A CACAROOTCH

The ultimate shape of the word alligator suggests the influence of folk etymology on a mere suffix. With cockroach, the process transformed both elements of another Spanish word, cucaracha, into recognizable English ones: cock + roach. Many people will know the original word from the popular Mexican song:

La cucaracha, la cucaracha,

ya no puede caminar

porque no tiene,

porque le falta

las dos patitas de atrás.

(The cockroach, the cockroach

Can’t walk anymore

Because it hasn’t

Because it’s missing

Its two rear leglets.)

The unpleasant bug first appeared in print in 1624 in The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles by John Smith, a picaresque character, soldier, and Virginia’s first colonial governor:

A certaine India Bug, called by the Spaniards a Cacarootch, the which creeping into Chests they eat and defile with their ill-sented dung.

Its spelling, like that of alligator, inevitably went through several mutations, before folk etymology pinned it down to its modern shape. For a long time it was hyphenated, and appears as Cock-roach in Darwin’s Origin of Species (1859).

CHAISE LOUNGES

A more recent example of folk etymology in action is chaise lounge, adapted from the French chaise longue. The word longue looks odd in English (a rare parallel is tongue), but a chaise longue is ideal for lounging; the alteration therefore seems quite logical. (Some are more for show than serious lounging, like Le Corbusier’s iconic creation.)  While chaise lounge is predominantly American, and not recognized as a British spelling, the OED shows it first in an impeccably British source: an edition of The Times of 1807.

While chaise lounge is predominantly American, and not recognized as a British spelling, the OED shows it first in an impeccably British source: an edition of The Times of 1807.

Filed under: Dictionaries & Lexicography, Folk etymology, Loanwords, OED, Word Histories Tagged: Around the world in 80 words, Spanish words in English

Alligators and cockroaches: what do they have in common?

BOTH ARE LOANWORDS

What is a loanword? It sort of does what it says on the tin. It is a word one language loans or lends to another (though the lender doesn’t usually get it back, and no interest is paid). And the word loanword is itself a loan translation, purloined from German Lehnwort.

English is full of loanwords, as are most, if not all, European languages.

BOTH ARE FROM SPANISH

Our alligator combines the Spanish word for “lizard” lagarto, and the Spanish definite article el “the”. So, if you run the two together you get elligarto, which eventually was standardized as alligator, though previously spelt in at least a dozen different ways.

The word first appeared in its Spanish form lagarto in translations into English in the second half of the 16th century.  It made an early appearance in Romeo and Juliet, when Romeo is describing an impecunious apothecary’s shop:

It made an early appearance in Romeo and Juliet, when Romeo is describing an impecunious apothecary’s shop:

And in his needie shop a tortoyes hung, An allegater stuft, and other skins Of ill shapte fishes, and about his shelves…

That is the spelling in the 1599 Quarto; in the 1597 Quarto it is Aligarta, which illustrates just how indeterminate the spelling originally was.

In the first half of the 17th century we find Sir Walter Raleigh  and Ben Jonson still using the more Spanish spelling: Alegartos and Alligarta respectively. So why did the letters rt of that final -arto or -arta get swapped round to -ator? The OED suggests that it was by association with the agent suffix -ator, found in administrator, imitator, and so on.

and Ben Jonson still using the more Spanish spelling: Alegartos and Alligarta respectively. So why did the letters rt of that final -arto or -arta get swapped round to -ator? The OED suggests that it was by association with the agent suffix -ator, found in administrator, imitator, and so on.

This change of form suggests the influence of folk etymology: the process by which people change the shape of a strange, unfamiliar word to make it fit in with a more familiar word or pattern.

A CACAROOTCH

The ultimate shape of the word alligator suggests the influence of folk etymology on a mere suffix. With cockroach, the process transformed both elements of another Spanish word, cucaracha, into recognizable English ones: cock + roach. Many people will know the original word from the popular Mexican song:

La cucaracha, la cucaracha,

ya no puede caminar

porque no tiene,

porque le falta

las dos patitas de atrás.

(The cockroach, the cockroach

Can’t walk anymore

Because it hasn’t

Because it’s missing

Its two rear leglets.)

The unpleasant bug first appeared in print in 1624 in The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles by John Smith, a picaresque character, soldier, and Virginia’s first colonial governor:

A certaine India Bug, called by the Spaniards a Cacarootch, the which creeping into Chests they eat and defile with their ill-sented dung.

Its spelling, like that of alligator, inevitably went through several mutations, before folk etymology pinned it down to its modern shape. For a long time it was hyphenated, and appears as Cock-roach in Darwin’s Origin of Species (1859).

CHAISE LOUNGES

A more recent example of folk etymology in action is chaise lounge, adapted from the French chaise longue. The word longue looks odd in English (a rare parallel is tongue), but a chaise longue is ideal for lounging; the alteration therefore seems quite logical. (Some are more for show than serious lounging, like Le Corbusier’s iconic creation.)  While chaise lounge is predominantly American, and not recognized as a British spelling, the OED shows it first in an impeccably British source: an edition of The Times of 1807.

While chaise lounge is predominantly American, and not recognized as a British spelling, the OED shows it first in an impeccably British source: an edition of The Times of 1807.

Filed under: Dictionaries & Lexicography, Folk etymology, Loanwords, OED, Word Histories Tagged: Spanish words in English

September 18, 2014

An Egyptian word borrowed by English: Chewing gum and pharaohs

One of life’s minor irritations is having to prise a half-solidified wad of chewing gum off the sole of your shoe because some unthinking slob spat it onto the pavement. This scourge of the street could be avoided if other governments were as draconian as the Singaporean authorities: they allow the import solely of medicinal gum, which has to be prescribed by a doctor, and impose a hefty ban for spitting gum out on the street.

One of life’s minor irritations is having to prise a half-solidified wad of chewing gum off the sole of your shoe because some unthinking slob spat it onto the pavement. This scourge of the street could be avoided if other governments were as draconian as the Singaporean authorities: they allow the import solely of medicinal gum, which has to be prescribed by a doctor, and impose a hefty ban for spitting gum out on the street.

But the habit of chewing resin or gum of some kind goes back several millennia. In 1993 archaeologists in Sweden found three gobbets of 9,000-year-old sweetened birch resin that had clearly been chewed by a human—in fact, by a teenager. And the word gum itself can be traced all the way back to ancient Egypt.

It started its journey to English in the form we would write as kemai.

(That first syllable kem- already shows a connection with the modern masticatory habit: the g of our gum and the k of kemai can be considered phonetically two sides of the same coin: g is the “voiced” counterpart of k. Try saying the /k/sound of came on its own and then the /g/ sound of game to appreciate their connectedness.)

But before it knuckled down to its role in modern English, kemai did a lot of travelling: its gap year turned into several centuries.

First, the Greeks adopted it in the form kommi (κόμμι), retaining the k sound of the Egyptian.  Pre-classical Greeks were profoundly influenced by Egyptian civilization, borrowing, among other things, some of their sculptural conventions in the “Archaic” period, before they achieved the extraordinary naturalism that we associate with their greatest sculptures.

Pre-classical Greeks were profoundly influenced by Egyptian civilization, borrowing, among other things, some of their sculptural conventions in the “Archaic” period, before they achieved the extraordinary naturalism that we associate with their greatest sculptures.

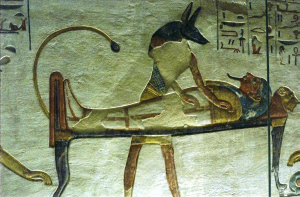

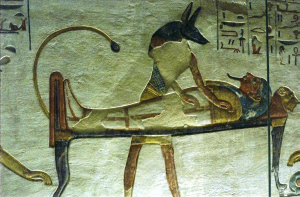

The historian Herodotus mentions kommi in his description of how the Egyptians embalmed bodies: “and when the seventy days have passed, they wash the body and wrap the whole of it in bandages of fine linen cloth, anointed with gum, which the Egyptians mostly use instead of glue”.

This is how the pharaohs would have been embalmed too.

From Greek it passed into Latin in the form cummi or gummi (classical Latin spelling, it seems, generally avoided the letter k). In late Latin the word changed to gumma, and was taken into Old French in the form gome. Thence it came into Middle English, in the prologue to Chaucer’s c1385 Legend of Good Women: “As for to speke of gomme or erbe or tre”. It makes another 14th century appearance, in the Wycliffite translation (before 1382) of the biblical Book of Jeremiah “Whether gumme is not in Galaad, or a leche is not there?”

That passage is better known nowadays in the King James wording: “Is there no balm in Gilead? Is there no physician there?”, balm being a resin with medicinal properties, and thus an image for something that heals spiritually.

That image found powerful expression in the African American spiritual, the chorus of which is:

There is a balm in Gilead, To make the wounded whole;

There is a balm in Gilead, To heal the sin-sick soul.

Gum in English referred originally to “a viscous secretion of some trees and shrubs that hardens on drying but is soluble in water, and from which adhesives and other products are made”. (In that sense, it contrasts with resin, which is insoluble in water).

From the 15th century onwards, it developed several meanings as a verb, including the modern one of “fastening with gum or glue”, which led to the further image in the phrasal verb gum up of clogging something up.

That meaning seems first to have developed in the US: the OED’s first quote is from an 1874 report by an American mining engineer. Nearly 50 years later, another US quote encloses it in quotation marks to indicate the writer’s doubts about its uncertain status, as novelty or slang.

The US has also given us two words for different kinds of footwear incorporating gum in the sense of “India rubber”. Gumboots (1850) are rubber boots or wellington boots; the word seems to be rarely used in British and US English nowadays, but is still going strong in Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa.

Much more evocative is the word gumshoes (1863), meaning galoshes. It first appeared in 1906 in relation to detective work in A.H. Lewis’s Confessions of a Detective: “You’re d’gum-shoe guy I was waitin’ fer… It was Inspector Val tells me to lay for you“.

Nowadays of course, gum generally means chewing gum, an industry apparently worth 19 billion dollars a year. That shorthand use goes back as far as 1842: “[She] asked me if I didn’t want A piece of gum to chaw”. At that time the gum would have been spruce gum.

It was not until 1871 that gum developed in its modern form, using chicle, a natural gum from various types of Central-American trees. (Chicle is the Spanish the word for chewing gum.) In Argentine Spanish the English chewing gum has been phonetically adapted as chuenga (pronounced chwenga) to mean a kind of sweet that stuck like a limpet to your teeth.

Filed under: Dictionaries & Lexicography, Loanwords, OED, Word Histories Tagged: Around the world in 80 words, chewing gum, Egyptian words in English

Chewing gum and pharaohs

One of life’s minor irritations is having to prise a half-solidified wad of chewing gum off the sole of your shoe because some unthinking slob spat it onto the pavement. This scourge of the street could be avoided if other governments were as draconian as the Singaporean authorities: they allow the import solely of medicinal gum, which has to be prescribed by a doctor, and impose a hefty ban for spitting gum out on the street.

One of life’s minor irritations is having to prise a half-solidified wad of chewing gum off the sole of your shoe because some unthinking slob spat it onto the pavement. This scourge of the street could be avoided if other governments were as draconian as the Singaporean authorities: they allow the import solely of medicinal gum, which has to be prescribed by a doctor, and impose a hefty ban for spitting gum out on the street.

But the habit of chewing resin or gum of some kind goes back several millennia. In 1993 archaeologists in Sweden found three gobbets of 9,000-year-old sweetened birch resin that had clearly been chewed by a human—in fact, by a teenager. And the word gum itself can be traced all the way back to ancient Egypt.

It started its journey to English in the form we would write as kemai.

(That first syllable kem- already shows a connection with the modern masticatory habit: the g of our gum and the k of kemai can be considered phonetically two sides of the same coin: g is the “voiced” counterpart of k. Try saying the /k/sound of came on its own and then the /g/ sound of game to appreciate their connectedness.)

But before it knuckled down to its role in modern English, kemai did a lot of travelling: its gap year turned into several centuries.

First, the Greeks adopted it in the form kommi (κόμμι), retaining the k sound of the Egyptian.  Pre-classical Greeks were profoundly influenced by Egyptian civilization, borrowing, among other things, some of their sculptural conventions in the “Archaic” period, before they achieved the extraordinary naturalism that we associate with their greatest sculptures.

Pre-classical Greeks were profoundly influenced by Egyptian civilization, borrowing, among other things, some of their sculptural conventions in the “Archaic” period, before they achieved the extraordinary naturalism that we associate with their greatest sculptures.

The historian Herodotus mentions kommi in his description of how the Egyptians embalmed bodies: “and when the seventy days have passed, they wash the body and wrap the whole of it in bandages of fine linen cloth, anointed with gum, which the Egyptians mostly use instead of glue”.

This is how the pharaohs would have been embalmed too.

From Greek it passed into Latin in the form cummi or gummi (classical Latin spelling, it seems, generally avoided the letter k). In late Latin the word changed to gumma, and was taken into Old French in the form gome. Thence it came into Middle English, in the prologue to Chaucer’s c1385 Legend of Good Women: “As for to speke of gomme or erbe or tre”. It makes another 14th century appearance, in the Wycliffite translation (before 1382) of the biblical Book of Jeremiah “Whether gumme is not in Galaad, or a leche is not there?”

That passage is better known nowadays in the King James wording: “Is there no balm in Gilead? Is there no physician there?”, balm being a resin with medicinal properties, and thus an image for something that heals spiritually.

That image found powerful expression in the African American spiritual, the chorus of which is:

There is a balm in Gilead, To make the wounded whole;

There is a balm in Gilead, To heal the sin-sick soul.

Gum in English referred originally to “a viscous secretion of some trees and shrubs that hardens on drying but is soluble in water, and from which adhesives and other products are made”. (In that sense, it contrasts with resin, which is insoluble in water).

From the 15th century onwards, it developed several meanings as a verb, including the modern one of “fastening with gum or glue”, which led to the further image in the phrasal verb gum up of clogging something up.

That meaning seems first to have developed in the US: the OED’s first quote is from an 1874 report by an American mining engineer. Nearly 50 years later, another US quote encloses it in quotation marks to indicate the writer’s doubts about its uncertain status, as novelty or slang.

The US has also given us two words for different kinds of footwear incorporating gum in the sense of “India rubber”. Gumboots (1850) are rubber boots or wellington boots; the word seems to be rarely used in British and US English nowadays, but is still going strong in Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa.

Much more evocative is the word gumshoes (1863), meaning galoshes. It first appeared in 1906 in relation to detective work in A.H. Lewis’s Confessions of a Detective: “You’re d’gum-shoe guy I was waitin’ fer… It was Inspector Val tells me to lay for you“.

Nowadays of course, gum generally means chewing gum, an industry apparently worth 19 billion dollars a year. That shorthand use goes back as far as 1842: “[She] asked me if I didn’t want A piece of gum to chaw”. At that time the gum would have been spruce gum.

It was not until 1871 that gum developed in its modern form, using chicle, a natural gum from various types of Central-American trees. (Chicle is the Spanish the word for chewing gum.) In Argentine Spanish the English chewing gum has been phonetically adapted as chuenga (pronounced chwenga) to mean a kind of sweet that stuck like a limpet to your teeth.

Filed under: Dictionaries & Lexicography, Loanwords, OED, Word Histories Tagged: chewing gum

September 11, 2014

Scottish Independence: Scaremongering versus dream-mongering

“Scaremongering”: a rhetorical ruse

“Scaremongering, scaremongering”. Whenever anyone tried to confront the Scottish king-this-side-of-the-water with the hard facts of reality, that was his, or the SNP’s, answer. It’s a tried-and-tested way of discrediting whatever the other person is saying, of “terminating the argument with extreme prejudice”. It is hard not to admit, though, that he is very good at rhetoric and verbal prestidigitation. His use of the word “scaremongering” is a case in point: he was artfully making use of an imbalance in the English language (I mean “English” in the sense of the language, not the nationality, in case anyone was wondering). It has no opposite, but in order to counter certain delirious imaginings it really ought to have, in order to fill what linguists call a “lexical gap”. I suggest “dream-mongering” or even “fantasy-mongering“. Please use either freely and often.

What’s a monger when it’s at home?

The noun monger is as ancient as the English (British?) language itself. It goes back to Old English and has cognates in Old Icelandic and Old High German. It means basically “a trader or dealer in a specified commodity”, and is best known to ordinary folk nowadays in its compounds fishmonger, ironmonger, and, for foodies, cheesemonger. Apart from those humdrum and innocuous words, however, -monger as a suffix has a long history, generally in the lexicon of abuse: foolmonger (1593), “one who trades on the credulity of fools” (how appropriate); mass-monger (1550), a disparaging term for a Roman Catholic; ballad-monger (1598), “one who writes in cheap or slanderous verse”.

Monger, monger on the wa’, whae’s the sleekitest o’ theim a’?

It was not until 1928, however, that monger morphed into an independent verb (though scaremongering is older–1907). Looking at a major online database of current English, I find that the verbal form -mongering occurs most often in the following combinations (ignore the inconsistent hyphenation): warmongering, fear-mongering, scare-mongering, doom-mongering, hate-mongering (the “Yes” campaign did a lot of that), rumour-mongering, conspiracy-mongering, panic-mongering.

So, full rhetorical marks to the ex-First Minister and his acolytes for using a word that gets a gut reaction (or even lower down for some people). It just sounds nasty and unappetizing, rhyming or half-rhyming as it does with hunger and fungus. And its definition is just as negative: “spreading frightening or ominous reports or rumours”. But what if the reports are likely to be true, or at least plausible, as they often are in this debate? It is as if the SNP are claiming the unique ability to unerringly see into the future, which is a rare gift indeed. In any case, the word scaremongering is so tainted by its negative associations that, unwittingly, people have an emotional reaction and automatically discard as untrue whatever is so described.

Filed under: Dictionaries & Lexicography, Meaning of words, Word Histories Tagged: scaremongering, Scottish independence

Scaremongering and dream-mongering for Scottish independence

“Scaremongering”: a rhetorical ruse

“Scaremongering, scaremongering”. Whenever anyone tries to confront the Scottish king-this-side-of-the-water with the hard facts of reality, that is his, or the SNP’s, answer. It’s a tried-and-tested way of discrediting, whatever the other person is saying, of “terminating the argument with extreme prejudice”. It is hard not to admit, though, that he is very good at rhetoric and verbal prestidigitation. His use of the word “scaremongering” is a case in point: he is artfully making use of an imbalance in the English language (I mean “English” in the sense of the language, not the nationality, in case anyone was wondering). It has no opposite, but in order to counter certain delirious imaginings it really ought to have, in order to fill what linguists call a “lexical gap”. I suggest “dream-mongering” or even “fantasy-mongering“. Please use either freely and often.

What’s a monger when it’s at home?

The noun monger is as ancient as the English (British?) language itself. It goes back to Old English and has cognates in Old Icelandic and Old High German. It means basically “a trader or dealer in a specified commodity”, and is best known to ordinary folk nowadays in its compounds fishmonger, ironmonger, and, for foodies, cheesemonger. Apart from those humdrum and innocuous words, however, -monger as a suffix has a long history, generally in the lexicon of abuse: foolmonger (1593), “one who trades on the credulity of fools” (how appropriate); mass-monger (1550), a disparaging term for a Roman Catholic; ballad-monger (1598), “one who writes in cheap or slanderous verse”.

Monger, monger on the wa’, whae’s the sleekitest o’ theim a’?

It was not until 1928, however, that monger morphed into an independent verb (though scaremongering is older–1907). Looking at a major online database of current English, I find that the verbal form -mongering occurs most often in the following combinations (ignore the inconsistent hyphenation): warmongering, fear-mongering, scare-mongering, doom-mongering, hate-mongering (the “Yes” campaign are doing a lot of that), rumour-mongering, conspiracy-mongering, panic-mongering.

So, full rhetorical marks to the First Minister and his acolytes for using a word that gets a gut reaction (or even lower down for some people). It just sounds nasty and unappetizing, rhyming or half-rhyming as it does with hunger and fungus. And its definition is just as negative: “spreading frightening or ominous reports or rumours”. But what if the reports are likely to be true, or at least plausible, as they often are in this debate? It is as if the SNP is claiming the unique ability to unerringly see into the future, which is a rare gift indeed. In any case, the word scaremongering is so tainted by its negative associations that, unwittingly, people have an emotional reaction and automatically discard as untrue whatever is so described.

Filed under: Dictionaries & Lexicography, Meaning of words, Word Histories Tagged: scaremongering, Scottish independence

September 6, 2014

Eggcorns: On tenterhooks or on tenderhooks?

What does it mean?

As we all know, it is to have that butterflies-in-the-stomach feeling, being totally wrought up because we don’t know how something important is going to turn out, whether some news will be as bad as we feared, be it A-level results, a job application, a medical test: “Britain’s farmers have been on tenterhooks since a vet found lesions–possible signs of foot and mouth disease–in the mouths of two sheep at the farm on Tuesday.”

Where does it come from?

Why tenterhooks? Most people absorb the phrase as a whole (or Gestalt, if we want to be pretentious): they grasp the meaning without analysing its constituents. Others grasp the meaning but change the form to tenderhooks. That change is understandable, because who on earth knows what a tenterhook is?

Well, it’s all to do with tenters—who are not people who have anything to do with tents or camping. In fact, they are not people at all. (There is a word tenter meaning someone who lives in a tent, but that’s a different word.)

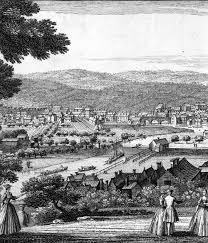

The tenter we’re interested in is, according to the OED, “a wooden framework on which cloth is stretched after being milled, so that it may set or dry evenly and without shrinking”. The OED also points out that tenters once stood in the open air in tenter-fields or grounds, and were a prominent feature in cloth-manufacturing districts.

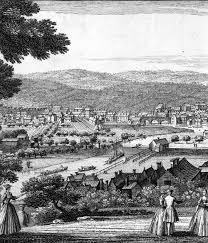

And in some antique panoramas of cities before or during industrialization the surrounding fields are filled with white waves of cloth suspended on tenters.

In the image here of Leeds in the 18th century (undated, but mid-, I guess, though I’m no costume expert) rows of tenters in some of the fields can just about be made out.

The origin of the word tenter, again according to the OED, is not certain, but may have to do with the Latin for stretching (tendĕre) or with the French for dye (teint).

And tenterhooks are?

As the OED puts it: “one of the hooks or bent nails set in a close row along the upper and lower bar of a tenter, by which the edges of the cloth are firmly held; a hooked or right-angled nail or spike; dial. a metal hook upon which anything is hung”.

How old is the word?

Tenters is first recorded in its literal sense from the 1300s (“Whon þe Iewes hedden þus nayled Criston þe cros as men doþ cloþ on a tey[n]tur”, Modern English: “When the Jews had thus nailed Christ on the cross as men doth cloth on a tenter“), while the last OED citation is from Charlotte Bronte’s Shirley (1849).

Tenterhooks makes its first OED appearance in a citation from the 1480 wardrobe accounts of King Edward IV. Another sartorial context (1579) is provided by the Office of the revels of Queen Elizabeth I. You could buy a lot of them very cheap (by today’s standards): “Tainter Hookes at viiid the c.“.

How old is the metaphor?

Very. Tenters was used in several phrases such as to put or stretch on the tenters in the 16th century. The next two quotations suggest by their visual immediacy how much tenters must have been part of everyday life. From the author of that jewel of our language The Book of Common Prayer, and Protestant martyr, Thomas Cranmer (1551): “But the Papistes haue set Christes wordes vppon the tenters and stretched them owt so farre, that they make his wordes to signyfy as pleaseth them, not as he ment”, (not a sentiment calculated to endear him to Queen Mary).

And in this simile by the Elizabethan dramatist Thomas Dekker (1602): “O Night, that…like a cloth of cloudes dost stretch thy limbes; Vpon the windy Tenters of the Ayre“.

Tenterhooks was used throughout the 16th and 17th centuries and beyond in various metaphors suggesting something causing suffering, and also the idea of stretching something beyond its proper bounds, as in this Isaac Disraeli (the Prime Minister’s dad) quote: “Honest men…sometimes strain truth on the tenter-hooks of fiction” (or, as we’d say nowadays, “are economical with the truth”).

However, according to the OED, the phrase to be on (the) tentherhooks meaning “to be in suspense” that has since become fossilized is first recorded only in 1748 in Smollett, and in its canonical form not until 1812, in the diary of soldier and diplomat Sir Robert Thomas Wilson: “Until I reach the imperial headquarters I shall be on tenter-hooks“.

Byron used the spelling “tender” – or did he?

The line from Don Juan runs as follows:

[It] keeps the atrocious reader in suspense; The surest way for ladies and for books To bait their tender or their tenter-hooks.

Does tender here go with hooks? Or is it used in the meaning of “offering”?

How frequent is the eggcorn version?

To be on tenderhooks is relatively well known among eggcornisti, and seems to me to be part of the “eggcorn canon”. But, actually, how frequent is it? I’ve looked at various sources, such as the Oxford English Corpus, the Corpus of Contemporary American, of Historical American, and Google books (US), which all suggest that it isn’t at all frequent, at least in written sources. For instance, in the GloWbE (the Corpus of Global Web-Based English) it occurs 3 times against 241 for the correct version. Similarly in Google US books (155 billion words) the figures are 57 to 8,238.

Dictionaries don’t accept the eggcorn, and judging by relative frequency are unlikely to for a long time.

Filed under: Advice for writers, Confusable words, Dictionaries & Lexicography, eggcorns, Grammar, Meaning of words, OED, Spelling, Word Histories Tagged: Byron

On tenterhooks or on tenderhooks?

What does it mean?

As we all know, it is to have that butterflies-in-the-stomach feeling, being totally wrought up because we don’t know how something important is going to turn out, whether some news will be as bad as we feared, be it A-level results, a job application, a medical test: “Britain’s farmers have been on tenterhooks since a vet found lesions–possible signs of foot and mouth disease–in the mouths of two sheep at the farm on Tuesday.”

Where does it come from?

Why tenterhooks? Most people absorb the phrase as a whole (or Gestalt, if we want to be pretentious): they grasp the meaning without analysing its constituents. Others grasp the meaning but change the form to tenderhooks. That change is understandable, because who on earth knows what a tenterhook is?

Well, it’s all to do with tenters—who are not people who have anything to do with tents or camping. In fact, they are not people at all. (There is a word tenter meaning someone who lives in a tent, but that’s a different word.)

The tenter we’re interested in is, according to the OED, “a wooden framework on which cloth is stretched after being milled, so that it may set or dry evenly and without shrinking”. The OED also points out that tenters once stood in the open air in tenter-fields or grounds, and were a prominent feature in cloth-manufacturing districts.

And in some antique panoramas of cities before or during industrialization the surrounding fields are filled with white waves of cloth suspended on tenters.

In the image here of Leeds in the 18th century (undated, but mid-, I guess, though I’m no costume expert) rows of tenters in some of the fields can just about be made out.

The origin of the word tenter, again according to the OED, is not certain, but may have to do with the Latin for stretching (tendĕre) or with the French for dye (teint).

And tenterhooks are?

As the OED puts it: “one of the hooks or bent nails set in a close row along the upper and lower bar of a tenter, by which the edges of the cloth are firmly held; a hooked or right-angled nail or spike; dial. a metal hook upon which anything is hung”.

How old is the word?

Tenters is first recorded in its literal sense from the 1300s (“Whon þe Iewes hedden þus nayled Criston þe cros as men doþ cloþ on a tey[n]tur”, Modern English: “When the Jews had thus nailed Christ on the cross as men doth cloth on a tenter“), while the last OED citation is from Charlotte Bronte’s Shirley (1849).

Tenterhooks makes its first OED appearance in a citation from the 1480 wardrobe accounts of King Edward IV. Another sartorial context (1579) is provided by the Office of the revels of Queen Elizabeth I. You could buy a lot of them very cheap (by today’s standards): “Tainter Hookes at viiid the c.“.

How old is the metaphor?

Very. Tenters was used in several phrases such as to put or stretch on the tenters in the 16th century. The next two quotations suggest by their visual immediacy how much tenters must have been part of everyday life. From the author of that jewel of our language The Book of Common Prayer, and Protestant martyr, Thomas Cranmer (1551): “But the Papistes haue set Christes wordes vppon the tenters and stretched them owt so farre, that they make his wordes to signyfy as pleaseth them, not as he ment”, (not a sentiment calculated to endear him to Queen Mary).

And in this simile by the Elizabethan dramatist Thomas Dekker (1602): “O Night, that…like a cloth of cloudes dost stretch thy limbes; Vpon the windy Tenters of the Ayre“.

Tenterhooks was used throughout the 16th and 17th centuries and beyond in various metaphors suggesting something causing suffering, and also the idea of stretching something beyond its proper bounds, as in this Isaac Disraeli (the Prime Minister’s dad) quote: “Honest men…sometimes strain truth on the tenter-hooks of fiction” (or, as we’d say nowadays, “are economical with the truth”).

However, according to the OED, the phrase to be on (the) tentherhooks meaning “to be in suspense” that has since become fossilized is first recorded only in 1748 in Smollett, and in its canonical form not until 1812, in the diary of soldier and diplomat Sir Robert Thomas Wilson: “Until I reach the imperial headquarters I shall be on tenter-hooks“.

Byron used the spelling “tender” – or did he?

The line from Don Juan runs as follows:

[It] keeps the atrocious reader in suspense; The surest way for ladies and for books To bait their tender or their tenter-hooks.

Does tender here go with hooks? Or is it used in the meaning of “offering”?

How frequent is the eggcorn version?

To be on tenderhooks is relatively well known among eggcornisti, and seems to me to be part of the “eggcorn canon”. But, actually, how frequent is it? I’ve looked at various sources, such as the Oxford English Corpus, the Corpus of Contemporary American, of Historical American, and Google books (US), which all suggest that it isn’t at all frequent, at least in written sources. For instance, in the GloWbE (the Corpus of Global Web-Based English) it occurs 3 times against 241 for the correct version. Similarly in Google US books (155 billion words) the figures are 57 to 8,238.

Dictionaries don’t accept the eggcorn, and judging by relative frequency are unlikely to for a long time.

Filed under: Dictionaries & Lexicography, eggcorns, Grammar, Meaning of words, OED, Spelling, Word Histories Tagged: Byron

August 30, 2014

One word or two? Whereas or where as?

Reading The Times recently I was struck by the following sentence: “He was apolitical. He [sc. Haider al-Abadi, Iraqi PM] never mentioned Iraq where as some students were vociferous”, Aug 16 2014.

It had never occurred to me that whereas might be written as two words, though it could easily be, since it is just a combination. There are several “words” which are sometimes written as one unit and sometimes as two, for example under way and underway, any more and anymore, and so forth. But whereas is not one of those: no current dictionary that I know of accepts the two-word spelling.

A quick check in the Oxford English Corpus (OEC) shows that whereas whereas as a single word appears over 100,000 times—as two words it’s in the hundreds.

It is impossible to give an exact figure, because searching for the string where as also finds sentences such as “Wolfowitz joined the bank in 2005 after working at the Pentagon, where as deputy defense secretary he was…”. What is clear, however, is that it is unusual, i.e. less than one per cent of cases. The OEC data also suggests that it occurs often in news and blog sources (come back subs, all is forgiven!).

Historically, it was originally two words. The earliest OED example is from The Paston Letters (1426-7), in the meaning now largely confined to legal writing, ‘taking into consideration the fact that’:

Where as þe seyd William Paston, by assignement and commaundement of þe seyd Duk of Norffolk…was þe styward of þe seyd Duc of Norffolk.

In its principal modern meaning (“in contrast”) it first appears in Coverdale’s Bible (1535), also as two words:

There are layed vp for vs dwellynges of health & fredome, where as we haue lyued euell.

(From Book 2 of Esdras, not included in the AV.)

The first OED citation for it as one word is in Shakespeare, Henry VI, Part 1 (written before 1616).

I deriued am From Lionel Duke of Clarence…; whereas hee, From Iohn of Gaunt doth bring his Pedigree.

So, while there are historical precedents for the two-word spelling, whereas is one of those words that current spelling convention decrees should not be sundered.

As a historical footnote, it is interesting that the legalistic, ritual use of whereas as a preamble to legal documents led to its being used as a noun, defined as follows in the Urban Dictionary of its day, Grose’s 1796 Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue “To follow a whereas; to become a bankrupt…: the notice given in the Gazette that a commission of bankruptcy is issued out against any trader, always beginning with the word whereas.”

Filed under: Dictionaries & Lexicography, Grammar, OED, One word or two?, Spelling, Word Histories Tagged: whereas