Jeremy Butterfield's Blog, page 31

August 4, 2014

World War I – Centenary of declaration of war

For me, this poem by Philip Larkin perfectly describes the mood of those young men who volunteered to fight, little realising the horrors of what lay in store, and the sadness inherent in their innocence.

MCMXIV

Those long uneven lines

Standing as patiently

As if they were stretched outside

The Oval or Villa Park,

The crowns of hats, the sun

On moustached archaic faces

Grinning as if it were all

An August Bank Holiday lark;

And the shut shops, the bleached

Established names on the sunblinds,

The farthings and sovereigns,

And dark-clothed children at play

Called after kings and queens,

The tin advertisements

For cocoa and twist, and the pubs

Wide open all day;

And the countryside not caring:

The place-names all hazed over

With flowering grasses, and fields

Shadowing Domesday lines

Under wheat’s restless silence;

The differently-dressed servants

With tiny rooms in huge houses,

The dust behind limousines;

Never such innocence,

Never before or since,

As changed itself to past

Without a word — the men

Leaving the gardens tidy,

The thousands of marriages

Lasting a little while longer:

Never such innocence again.

From The Whitsun Weddings, 1964.

Filed under: Poetry Tagged: Philip Larkin, World War 1

July 19, 2014

Like lemmings to the slaughter?

One of the mysteries of English is why this diminutive creature has become a byword for impulsive herdlike behaviour, even mass hysteria. These appealing northern rodents are the victims of a bad press—or at least a very inaccurate one.

Not a computer game…

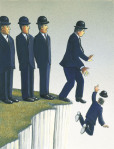

For many people the word will first bring to mind a computer game created in 1991 and as unstoppably addictive as such games easily become. The aim was to save the critters in their headlong rush to mass self-destruction. Their supposed suicidal urges were also the inspiration for a 1985 advertisement launching Apple Macintosh’s Office. Suited businesspeople were shown walking blindfolded and in single file up to a cliff edge, from which they hurled themselves into the abyss, until the last in the line took off his blindfold to the voiceover, “You can look into it. Or you can go on with business as usual.”

A potent urban myth

That lemmings deliberately self-destruct en masse is a complete myth, but one that has a powerful hold on the popular imagination. It is one of those many mistaken things that we all “know” (in the same way that we “know” that Eskimos have dozens of words for snow). And it is a myth firmly embedded in English as a way of symbolizing people who unthinkingly follow what the crowd are doing, often with dangerous, if not downright fatal, consequences.

Where did the myth originate?

I remember being struck by a compelling sequence from a 1958 Walt Disney short nature film entitled White Wilderness. It purported to show wave after wave of lemmings plummeting unstoppably over precipitous cliffs into the Arctic Ocean. Accompanied by a portentous commentary and melodramatic music, that film helped sear the idea of rodents with an unquenchable deathwish into the public’s consciousness. It was, however, a cruel fake. Clever camera angles and good editing made it look real, but the (actually rather few) lemmings were cascading into a river, not into the sea, and they were, it seems, being launched from a rotating turntable. If you watch that footage—which now looks very much of its era—you will understand immediately why lemmings became such a powerful metaphor for unthinking, self-destructive mass behaviour.

“The science bit”

Lemming describes twenty species subdivided into six genera and belonging to the same superfamily as rats, mice, gerbils and hamsters. They are widespread in the cooler north of Eurasia and North America and range from three to six inches in length. Far from succumbing to suicidal groupthink, these creatures live solitary, hermitic lives, only associating with others, as they must, for mating purposes. Unlike other rodents, which have inconspicuous coats, their pelts are variegated. They are also aggressive towards predators. The Norwegian lemming, Lemmus lemmus, travels considerable distances in its migrations.

Populations fluctuate wildly

Lemming populations fluctuate wildly for reasons not fully understood, and when population density reaches a critical level, they migrate collectively. Since they can swim, they may attempt to cross stretches of water that are beyond their natatorial abilities, and consequently drown.

History of a simile

The OED gives the first example of the metaphorical use from a 1959 book (“Home-going office workers…potent in mass as a lemming migration“), but Google Ngrams throws up an example from the 1930s: “…logicians fling themselves headlong in hordes, like lemmings; and suicidally discuss the import of ‘propositions’ such as ‘The King of Utopia died last Sunday…,” from The Principles of Art by the British philosopher R.G. Collingwood.

On a more pedestrian level, but more dramatically, Life of 5 January 1942 reported that “Men and Women are swarming out of the Navy Building, the War Department, Labor, Interior, Commerce, not with the orderliness of ants but like lemmings swarming blindly toward the Baltic.”

These examples predate the Disney film, and suggest that the myth was current well before it.

How the simile works

Typically, an explicit comparison is made using the preposition like. Tendentiously, as in:

At present, all countries of the world are marching like lemmings over the philosophical precipice to collectivism.

Financial Sense Online, Editorials 2005.

Or slightly naughtily, as in:

…the run of articles about how being tall and good looking and banging Playmates who line up like lemmings ready to fall over his penis made Michael Bay…

The Hot Button, 2002.

In the first the reference to cliffs is explicit, in the second it is (punningly?) implicit. In a minority of examples with like, the word cliff actually appears in the context:

Sky One’s audience has been deserting it, disappearing like lemmings over a cliff, according to Dawn Airey, the managing director of Sky Networks.

Sunday Times, 19 September 2004.

The comparison is also lexicalized in the adjective lemming-like:

After the Diana nonsense, when complete strangers lemming-like threw themselves into publicity-driven grief, through Charles and Camilla’s redemption, we are now spoon-fed the William and Kate Show.

Daily Telegraph, 2012, quoting MSP Christine Grahame.

Like lemmings to the slaughter

As I was writing this, I wondered, “Has anyone changed ‘like lambs to the slaughter’ to ‘like lemmings to the slaughter’”. And, sure enough, they have, but the phrase is not terribly common. A google for those exact phrases throws up under 3,000 for the rodent one, but over 650,000 for the ovine one. The one with lemmings seems slightly odd, since they are not exactly slaughtered by another agent, but it’s an interesting example of a blend of two phrases. Pedants might consider it a sort of malapropism (or it might be a sort of phrasal eggcorn). However, the examples seem to suggest that it is different from “lambs to the slaughter”. Whereas the latter emphasizes that the victims go meekly into a situation of whose dangers they are unaware, the lemmings simile foregrounds the idea of people blindly rushing to do something foolish or dangerous.

In one example it’s the heading to a blog (spamdalot) that continues as shown: “Like Lemmings To The Slaughter. One thing I’ve noticed about Portland is that the pedestrians here have a deathwish…“. In another it’s also a heading, this time in a post on an investment website (Stanford Brown): “Like lemmings to the slaughter………at our April Insight we highlighted that individuals make such poor investors principally because of our insatiable appetite to buy high and sell low. The exact same pattern is happening again“.

Not the only myth

But the suicide myth is not the only one that has attached to lemmings. For a long time they were thought to fall from the sky. In 1555 the Swedish Catholic cleric Olaus Magnus, then exiled in Rome, published in Latin his History of the Northern Peoples (Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus), detailing Swedish history and customs.

About lemmings he wrote: “Quod…in Noruegia…euenit, scilicet vt bestiolæ quadrupedes, Lemmar, vel Lemmus dictæ, magnitudine soricis, pelle varia, per tempestates & repentinos imbres è cœlo decidant“.

(Translation) “Which…happens in Norway, namely that little four-footed creatures, called Lemmar or Lemmus, of the size of shrewmice, with variegated hide, fall from the sky through storms and sudden showers.”

This account was repeated almost verbatim at the word’s first appearance in English, in The historie of four-footed beastes, by Edward Topsell, who was, it seems, much given to plagiarism:

There are certaine little Foure-footed-beastes called Lemmar, or Lemmus, which in tempestuous and rainy weather, do seeme to fall downe from the cloudes.

So, where does the word come from?

The word lemming is, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, borrowed straight from Norwegian, and has not been modified in English. Swedish and Lapp have similar words — lemmel and luomek — and it is possible that the word is related to words meaning “to bark”, such as Latin lātrāre and Lithuanian lōti. Certainly, when they are angry one of the noises they make sounds not dissimilar to the bark of a small dog, as you can hear here.

Other Norwegian loanwords

Lemming is not the most common word English has borrowed from Norwegian. Leaving aside the obvious fjord, that honour must surely go to ski, first recorded as a noun in 1755, and as a verb only as late as 1893.

It is interesting that in Norwegian the sk is pronounced sh, the pronunciation reflected in Italian sciare. It was also the English pronunciation Fowler recommended in his 1926 Dictionary of Modern English Usage. Norwegian has also given the skiing world the term slalom, the downhill race, from slalåm, (from sla sloping + låm track).

The Kraken Wakes

The lemming myth mixes fact and fiction, but another Norwegian loanword (1775) plunges us into the world of entirely mythical and terrifying sea creatures: the kraken. This creature was reputedly so enormous that when it dived it created a whirlpool big enough to engulf even the largest ship. Its most famous English incarnation is probably in the title of the 1953 sci-fi novel The Kraken Wakes, by John Wyndham.

It also found its place in 19th century poetry in a sonnet by Tennyson that is somewhat unusual in having fifteen lines rather than the normal fourteen.

Below the thunders of the upper deep;

Far, far beneath in the abysmal sea,

His ancient, dreamless, uninvaded sleep

The Kraken sleepeth: faintest sunlights flee

About his shadowy sides: above him swell

Huge sponges of millennial growth and height;

And far away into the sickly light,

From many a wondrous grot and secret cell

Unnumbered and enormous polypi

Winnow with giant arms the slumbering green.

There hath he lain for ages and will lie

Battening upon huge sea-worms in his sleep,

Until the latter fire shall heat the deep;

Then once by man and angels to be seen,

In roaring he shall rise and on the surface die.

Finally, those who in Scotland are bitten by vicious clegs (i.e. horseflies) will be gratified to know that they have been wounded by an Old Norse beast, kleggi, or klegg in Modern Norwegian.

Filed under: eggcorns, Loanwords, OED, Word Histories Tagged: Lemmings, Norwegian words in English, Urban myths

May 21, 2014

Beyond Traffic: Three Stats You Should Check Today

Originally posted on WordPress.com News:

Originally posted on WordPress.com News:

When you hear “stats,” most bloggers think “traffic,” and that makes sense. Many of us care about the number of views our posts receive, and want to see them grow. Blogging is never solely about numbers, though — it’s about making your voice heard, fostering relationships with others, and building a sense of community.

Approaching these goals with a data-informed mindset can get you closer to achieving them. Here are three stats that can help you make smart decisions when it comes to planning your posts and finding and engaging your readers. Whether you blog from a computer, a tablet, or your phone, take a few seconds to explore these on your own blog’s Stats tab.

A quarterly review

When reviewing your stats, it’s tempting to focus on the here and now: how did I do today? How many views did yesterday’s post get overnight? Periodically, though, it’s wise to fight…

View original 529 more words

Filed under: Advice for writers, Wordpress skills Tagged: wordpress stats

May 20, 2014

Lovely Lady Mondegreen

How often do we ask someone to repeat something we didn’t quite catch? Then sometimes we don’t ask and we get hold of the wrong end of the stick. It must have happened to everyone at some point. An extreme example is when someone is hard of hearing. A contributor to an online forum mentioned her somewhat deaf father’s hilarious mishearings: asked for a passage from scripture he understood a boa constrictor.

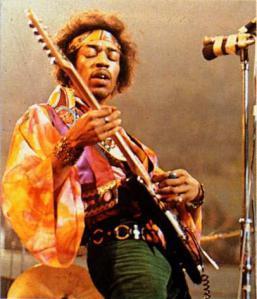

One form of language that is easy to mishear or misinterpret is songs, hymns, and anthems. The often-quoted classic example is Jimi Hendrix’s Purple Haze ‘Scuse me while I kiss the sky being understood as ‘Scuse me while I kiss this guy. Wikipedia suggests that Jimi knew about this mishearing and played up to it.

Another example, possibly mythical, is Gladly, the cross-eyed bear for Gladly my cross I’ll bear from a late nineteenth-century hymn.

Another example, possibly mythical, is Gladly, the cross-eyed bear for Gladly my cross I’ll bear from a late nineteenth-century hymn.

Keep Thou my all, O Lord, hide my life in Thine;

O let Thy sacred light over my pathway shine;

Kept by Thy tender care, gladly the cross I’ll bear;

Hear Thou and grant my prayer, hide my life in Thine.

From Keep Thou My Way, Fanny Crosby, 1894.

Kids often do it

We always want to make sense of what we hear. So if the sounds that reach our ears don’t make sense to our brains, we reinterpret them or fill in the gaps with words we do know. Adults don’t have to do that too often, because they know a lot. Children know less about the world, and fewer words. That’s why they can interpret words new to them in strange ways.

Mother:

What did you learn at school today?

Girl:

I know a song about rabbits!

Mother:

Oh? Can you sing it…?

Girl:

Oh yes! it goes – Speed, bunny boat, like a bird on the wing…!

A special name for slips of the ear

Slips of the ear of this kind are known as mondegreens. The American writer Sylvia Wright coined the word in 1954, and she explained why:

“When I was a child, my mother used to read aloud to me from Percy’s Reliques, and one of my favorite poems began, as I remember: ‘Ye Highlands and ye Lowlands, Oh, where hae ye been? They hae slain the Earl Amurray, And Lady Mondegreen'”. But the exact words of the ballad are (in the closest I can find to the original Scots):

YE highlands, and ye lawlands, Oh! quhair hae ye been? They hae slaine the Earl of Murray, And hae laid him on the green.

Her mishearing of “laid him on the green” as “Lady Mondegreen” illustrates the mistaken analysis of word boundaries that is typical of mondegreens. Technically, it is known as metanalysis. Historically, metanalysis has produced an adder from a nadder and a newt from an ewt. Ultimately, it gave us an orange from the Arabic nāranj.

Perhaps Lady Mondegreen looked as sad as this when she lost her Earl of Murray.

The celebrated columnnist William Safire commented on mondegreens and similar here. I blogged previously about the similar phenomenon of eggcorns.

Filed under: Meaning of words, Spelling, Word Histories Tagged: Jimi Hendrix, Mondegreens

May 18, 2014

An epicene protest

Originally posted on Arnold Zwicky's Blog:

Originally posted on Arnold Zwicky's Blog:

In a bizarre response to the winning of the Eurovision Song Contest by a bearded drag queen, Conchita Wurst singing “Rise Like a Phoenix” (reported in almost every media outlet), some Russian men have taken to shaving off their beards (if they had them). The position seems to be that Wurst’s beard so poisons beards as a symbol of masculinity that real men have no way to protest except by going beardless. (The idea here seems to some degree to be similar to the position that same-sex marriage diminishes and debases opposite-sex marriage — except that in the Wurst case, the threat comes from a single case: just one, though admittedly very visible, bearded man in a dress.)

The result is paradoxical.

View original 345 more words

Filed under: Dictionaries & Lexicography, Meaning of words