Jeremy Butterfield's Blog, page 25

January 7, 2016

elicit vs illicit. What’s the difference? Easily confused words (21-22)

Quick “takeaways”

Elicit and illicit do not mean the same thing at all. Elicit is a verb only**, illicit is solely an adjective.

Beware of accidentally using illicit as a verb when you want to talk about evoking a reaction or extracting information.

Correct: He used good actors who are capable of eliciting genuine sympathy from the audience.

Incorrect: It’s likely to X illicit a collective groan.

Beware of using elicit as an adjective.

Correct: The Grenadines, with their many uninhabited islets, are a transhipment point for illicit drugs from South America to the United States.

Incorrect: It was hard to imagine why his wife should believe that there were women just waiting to entice him into an X elicit liaison.

Self-test

Having warmed up with the above, you might like to try some verbal gymnastics.

A word is missing from these authentic (i.e. not made up by me) sentences. If you’re game, to complete the meaning choose one of the alternatives shown.

The detective involved was reprimanded for ______ false confessions. a) illiciting; b) eliciting.

Heavy drinking or ______ drug use make treatment ineffective. a) elicit; b) illicit.

That remark ______ friendly laughter from the audience. a) elicited; b) illicited.

It is a rare film that can ______ that response from me. a) illicit; b) elicit.

These are things that, like Greene’s ______ liaisons , remain to be forgiven. a) illicit; b) elicit.

(Answers at the end.)

If you got them all right, you probably know all you need to know about illicit vs. elicit.

If not, what follows may help you to avoid confusing them.

Why are they confused?

Simples! They sound identical, as their phonetic representation shows:

elicit /ɪˈlɪsɪt/

illicit /ɪˈlɪsɪt/

So, they are examples of what are called homophones: words that sound exactly the same but have different spellings and meanings.

A crucial distinction between them is that elicit is a verb. It can therefore have all the verb parts, i.e. elicits, eliciting, elicited.

Illicit is an adjective and has only the one form as an adjective. Its derivatives are illicitly and illicitness.

TIP: Because of the above, if you come across X illiciting, for example, or if you find yourself writing it, you will know that it is a mistake. (An automatic spellchecker would pick it up as a mistake in any case.)

TIP: Something illicit borders on being illegal, so remembering the ill– element in both may help. If you elicit a reaction, you evoke it, so remembering the e- prefix (meaning “out”) may help.

(If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!)

Meanings and origins

Meaning

The verb elicit means “to evoke or draw out (a reaction, answer, or fact) from someone”. The kinds of thing that you can elicit include reactions and responses; physical reactions such as applause, laughter, chuckles, giggles; and emotional reactions such as emotion, admiration, sympathy, and pity. You can also elicit information, confessions, and testimony.

The Yorkshire Gazette recorded how he “elicited unbounded applause, and sent his audience home delighted with their evening’s amusement”.

Subsequent staff letters to the college administration, inviting discussion of remaining issues, have not elicited a reply.

Illicit is an adjective, meaning “forbidden by law, rules, or custom”.

Things that are typically illicit include drugs, substances, liquor, opium, trade and trafficking, on the one hand, and liaisons, trysts, affairs, and sex, on the other.

Less easily influenced is the illicit trade in armaments around the globe.

South Africans don’t tend to dump their illicit sex lives in tacky red-light districts.

The connection of illicit with sex or romance was highlighted in the 1931 film Illicit, in which the heroine, played by Barbara Stanwyck, lives together with her boyfriend “out of wedlock”, and so the film must have been pretty racy for its time.

Origins

They may look at first glance as if they are related, but they come from two different Latin roots.

Elicit comes from the past participle of the Classical Latin ēlicĕre “to draw or entice (someone) out”.

According to the OED, it was first used in 1641.

Illicit comes from French illicite, which comes from the Latin adjective illicitus, a combination of the negative prefix il- and licitus, past participle of the impersonal verb licēre “to be allowed”. The same verb is the root of licence, licit, and leisure.

It was first used in English in 1606.

Its derivatives are illicitly and illictness.

How often are they confused?

Without substantial research, it’s impossible to give figures. However, a scan of Oxford English Corpus data suggests that perhaps illicit is more often wrongly used as a verb than elicit is as an adjective.

The following examples are typical of the “accidents that will occur in the best-regulated”… newspapers, journals, and even High Court transcripts:

The Prince of Wales and his charities have a growing property portfolio, but there is one notable building that is unlikely to X illicit a bid from the heir to the throne. Telegraph, 2011

X Elicitly gathering information is a step too far. Guardian, 2012

Raise it for debate in the pub and it’s likely to X illicit a collective groan, but in boardrooms and dressing rooms it has greater currency. Scotland on Sunday, 2005

…the cost is high and the prospects of any helpful information being X illicited by the independent analysis, remote. England and Wales High Court Decisions, 2003

…such confessions of diabolic sexual attack were merely excuses to cover up the evidence of masturbation or X elicit affairs. Folklore, 2003.

ANSWERS:

1. b); 2. b); 3. a); 4. b); 5. a).

** There is also an obsolete adjective elicit, defined by the OED as “Of an act: Evolved immediately from an active power or quality; opposed to imperate.”

Filed under: Advice for writers, Confusable words, Meaning of words Tagged: easily confused words

December 14, 2015

Portuguese words in English: marmalade, mangoes, and maracas

It’s not on the list of 100 English icons voted for by the public, but a full English Breakfast is.

And without marmalade, a full English Breakfast would, to my mind, be, um, well, half empty.

It turns out that even D. H. Lawrence — that writer of the “not very British” lubricious poem about figs — made it, as emerges from what sounds like a WI motivational quote (“I got the blues thinking of the future, so I left off and made some marmalade. It’s amazing how it cheers one up to shred oranges and scrub the floor.”)

Naturalized Brit Ruby Wax said, “I once did an on-line interview where I had to write the answers to the questions. I never speak that slowly. It was like having sex in marmalade.”

Noel Coward opined that

“Wit ought to be a glorious treat like caviar; never spread it about like marmalade.”

Virginia Woolf’s husband listed it as one of the ingredients of, presumably, a highly nourishing tea:

A spread of boiled haddock, apple tart, tea, toast, butter, marmalade, & cake in front of a huge fire awaited us.

L. Woolf , Let. 30 Nov., 1917

Yes, all in all, it’s a very British institution, but it’s also one of those thousands of words English has borrowed from other languages – Portuguese in this instance.

So British is it, in fact, that it first appeared in English (1480, in the form marmelate) a full sixty years before its appearance in any other European language.

Words from Portuguese

Portuguese loanwords in English cannot compete numerically with those from the other Western Romance languages (French, Spanish, Italian). Nevertheless, the OED lists 398 (compared, for instance, to more than four times that number for Spanish, at 1748).

English borrowed them from Portuguese, but Portuguese borrowed them too.

A handful of these 398 words derive(d) from existing Portuguese words, e.g. lambada (from lambar, “to beat, to whip”). But most draw on the many languages with which Portuguese merchants, explorers and seamen came into contact during Portugal’s history as a seafaring and colonizing power. (In fact, Portugal was the last European colonizer to relinquish a colony, when East Timor achieved independence in 2002.)

‘Vasco da Gama’ (circa 1460-1524), oil on canvass by Antonio Manuel da Fonseca, 1838. In the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

Because of this rich colonial history, Portuguese has one of the highest number of mother-tongue speakers in the world: ranking sixth, according to the Ethnologue, below Arabic and above Bengali.

An exotic cornucopia

In their search for the fabled spices of the East and other precious commodities, the Portuguese traded in much of the known world, particularly Africa and the Far East, and, of course, Brazil (now the country with the largest number of Portuguese speakers). Many of the words Portuguese has given to English reflect encounters with local flora and fauna, e.g. cougar, jaguar, macaw, mongoose, and mango. Others describe artefacts encountered in indigenous cultures, e.g. fetish, marimba, and maracas.

We first encounter many of these Portuguese loanwords in late-sixteenth- or seventeenth-century English translations of foreign explorers’ descriptions of the lands they visited, translations that vividly convey contemporary fascination with the “new worlds” being opened up to Europeans.

Varied origins of Portuguese loanwords

As varied as the meanings of those words are their origins. While Portuguese was the immediate vehicle for transmission into English, the Portuguese language itself often “borrowed” them from other languages, including Arabic, Indian subcontinent languages such as Malayalam and Marathi, and African and South American languages. Mango and maraca illustrate that; the first is probably immediately either from Malayalam māṅṅa, a Dravidian Indian language related to Tamil, or from Malay mangga, and before that in either case from Tamil mankay, from man “mango tree” + kay “fruit”; the second is from Tupi or Guaraní, both South American languages.

If you are enjoying this blog, and finding it useful or interesting, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column, above the Twitter feed) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging semi-(ir)regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

But marmalade has a longer, European history

…if you go back far enough.

The immediate source is the Portuguese word for “quince”, marmelo + the suffix -ada (= -ade).

By Brigitte E.M. Daniel, 2000.

As the OED explains, originally marmalade referred to “a preserve consisting of a sweet, solid, quince jelly resembling chare de quince [= “quince flesh”] but with the spices replaced by flavourings of rose water and musk or ambergris, and cut into squares for eating”.

It must therefore have been similar to the luscious, toothsome quince jelly that is now fashionable as an accompaniment to cheese. Often, it is the imported Spanish delicacy dulce de membrillo (literally, “sweet of quince”, the Spanish word membrillo deriving, like the Portuguese, from Latin.)

That quince jelly (chare de quince) is mentioned in the Paston Letters:

I pray yow that ye wol send me a booke wyth chardeqweyns that I may have of in the mo[r]nyngges, for the eyeres be not holsom in this town.

1451, M. Paston in Paston Lett. & Papers (2004) I. 247,

(I assume that “booke” here reflects this OED meaning: “A packet of some other commodity bound together for ease of handling or dispensing”.)

Later, as the OED explains: “Subsequently: a conserve made by boiling fruits (now usually oranges and other citrus fruits) in water…typically containing embedded shreds of rind…Often with the name of the fruit or other dominant ingredient prefixed, as apricot…onion…quince When none is specified, orange marmalade is now usually meant.”

Which explains why onion marmalade is so called, though it seems a long way from jentacular marmalade.

[I wanted an adjective relating to breakfast that isn’t breakfast used attributively , and jentacular is it — such a shame it is obsolete.]

Where does the word marmelo come from?

It didn’t descend angelically out of thin air.

In etymology, the “less than” < symbol is used to show the source language on the right, and the receiving language on the left, e.g. English < French. But, as we read from left to right, I think it’s easier to reverse the direction and the symbols, which gives us this for the long road marmalade has travelled.

Classical Greek μῆλον mēlon (= apple), μέλι meli = (honey)

> Hellenistic Greek μελίμηλον melímēlon (summer-apple, apple grafted on quince)

> classical Latin mēlomeli (honey flavoured with quinces) + melimēla (plural) (a variety of sweet apple)

> post-classical Latin malomellum (quince or sweet apple).

> Portuguese marmelo (1527) but marmeleira (quince orchard, 973).

As the OED suggests, “Close medieval trading relations between England and Portugal may account for the very early borrowing of the Portuguese word in English.”

So there we have it: a word for a quintessentially British preserve whose roots can ultimately be traced back, if you like, to Homer and beyond.

many a tall tree did he uproot and cast upon the ground,

aye, root and apple blossom therewith.

πολλὰ δ᾽ ὅ γε προθέλυμνα χαμαὶ βάλε δένδρεα μακρὰ

αὐτῇσιν ῥίζῃσι καὶ αὐτοῖς ἄνθεσι μήλων.

Homer, Iliad, Bk 9, l. 542.

I don’t have a sweet tooth, really. I think I’ll go and have some Marmite on toast.

Filed under: Loanwords, Word origins Tagged: Around the world in 80 words, Portuguese loanwords in English

Marmalade, mangoes and maracas: Portuguese words in English

It’s not on the list of 100 English icons voted for by the public, but a full English Breakfast is.

And without marmalade, a full English Breakfast would, to my mind, be, um, well, half empty.

It turns out that even D. H. Lawrence — that writer of the “not very British” lubricious poem about figs — made it, as emerges from what sounds like a WI motivational quote (“I got the blues thinking of the future, so I left off and made some marmalade. It’s amazing how it cheers one up to shred oranges and scrub the floor.”)

Naturalized Brit Ruby Wax said, “I once did an on-line interview where I had to write the answers to the questions. I never speak that slowly. It was like having sex in marmalade.”

Noel Coward opined that

“Wit ought to be a glorious treat like caviar; never spread it about like marmalade.”

Virginia Woolf’s husband listed it as one of the ingredients of, presumably, a highly nourishing tea:

A spread of boiled haddock, apple tart, tea, toast, butter, marmalade, & cake in front of a huge fire awaited us.

L. Woolf , Let. 30 Nov., 1917

Yes, all in all, it’s a very British institution, but it’s also one of those thousands of words English has borrowed from other languages – Portuguese in this instance.

So British is it, in fact, that it first appeared in English (1480, in the form marmelate) a full sixty years before its appearance in any other European language.

Words from Portuguese

Portuguese loanwords in English cannot compete numerically with those from the other Western Romance languages (French, Spanish, Italian). Nevertheless, the OED lists 398 (compared, for instance, to more than four times that number for Spanish, at 1748).

English borrowed them from Portuguese, but Portuguese borrowed them too.

A handful of these 398 words derive(d) from existing Portuguese words, e.g. lambada (from lambar, “to beat, to whip”). But most draw on the many languages with which Portuguese merchants, explorers and seamen came into contact during Portugal’s history as a seafaring and colonizing power. (In fact, Portugal was the last European colonizer to relinquish a colony, when East Timor achieved independence in 2002.)

‘Vasco da Gama’ (circa 1460-1524), oil on canvass by antonio Manuel da Fonseca, 1838. In the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

Because of this rich colonial history, Portuguese has one of the highest number of mother-tongue speakers in the world: ranking sixth, according to the Ethnologue, below Arabic and above Bengali.

An exotic cornucopia

In their search for the fabled spices of the East and other precious commodities, the Portuguese traded in much of the known world, particularly Africa and the Far East, and, of course, Brazil (now the country with the largest number of Portuguese speakers). Many of the words Portuguese has given to English reflect encounters with local flora and fauna, e.g. cougar, jaguar, macaw, mongoose, and mango. Others describe artefacts encountered in indigenous cultures, e.g. fetish, marimba, and maracas.

We first encounter many of these Portuguese loanwords in late-sixteenth- or seventeenth-century English translations of foreign explorers’ descriptions of the lands they visited, translations that vividly convey contemporary fascination with the “new worlds” being opened up to Europeans.

Varied origins of Portuguese loanwords

As varied as the meanings of those words are their origins. While Portuguese was the immediate vehicle for transmission into English, the Portuguese language itself often “borrowed” them from other languages, including Arabic, Indian subcontinent languages such as Malayalam and Marathi, and African and South American languages. Mango and maraca illustrate that; the first is from Malayalam, a Dravidian Indian language related to Tamil; the second is from Tupi or Guaraní, both South American languages.

But marmalade has a longer, European history

…if you go back far enough.

The immediate source is the Portuguese word for “quince”, marmelo + the suffix -ada (= -ade).

By Brigitte E.M. Daniel, 2000.

As the OED explains, originally marmalade referred to “a preserve consisting of a sweet, solid, quince jelly resembling chare de quince [= “quince flesh”] but with the spices replaced by flavourings of rose water and musk or ambergris, and cut into squares for eating”.

It must therefore have been similar to the luscious, toothsome quince jelly that is now fashionable as an accompaniment to cheese. Often it is the imported Spanish delicacy dulce de membrillo (literally, “sweet of quince”, the Spanish word membrillo deriving, like the Portuguese, from Latin.)

That quince jelly (chare de quince) is mentioned in the Paston Letters:

I pray yow that ye wol send me a booke wyth chardeqweyns that I may have of in the mo[r]nyngges, for the eyeres be not holsom in this town.

1451, M. Paston in Paston Lett. & Papers (2004) I. 247,

(I assume that “booke” here reflects this OED meaning: “A packet of some other commodity bound together for ease of handling or dispensing”.)

Later, as the OED explains: “Subsequently: a conserve made by boiling fruits (now usually oranges and other citrus fruits) in water…typically containing embedded shreds of rind…Often with the name of the fruit or other dominant ingredient prefixed, as apricot…onion…quince When none is specified, orange marmalade is now usually meant.”

Which explains why onion marmalade is so called, though it seems a long way from jentacular marmalade.

[I wanted an adjective relating to breakfast that isn’t breakfast used attributively , and jentacular is it — such a shame it is obsolete.]

Where does the word marmelo come from?

It didn’t descend angelically out of thin air.

In etymology, the “less than” < symbol is used to show the source language on the right, and the receiving language on the left, e.g. English < French. But, as we read from left to right, I think it’s easier to reverse the direction and the symbols, which gives us this for the long road marmalade has travelled.

Classical Greek μῆλον mēlon (= apple), μέλι meli = (honey)

> Hellenistic Greek μελίμηλον melímēlon (summer-apple, apple grafted on quince)

> classical Latin mēlomeli (honey flavoured with quinces) + melimēla (plural) (a variety of sweet apple)

> post-classical Latin malomellum (quince or sweet apple).

Portuguesemarmelo (1527) but marmeleira (quince orchard, 973).

As the OED suggests, “Close medieval trading relations between England and Portugal may account for the very early borrowing of the Portuguese word in English.”

So there we have it: a word for a quintessentially British preserve whose roots can ultimately be traced back, if you like, to Homer and beyond.

many a tall tree did he uproot and cast upon the ground,

aye, root and apple blossom therewith.

πολλὰ δ᾽ ὅ γε προθέλυμνα χαμαὶ βάλε δένδρεα μακρὰ

αὐτῇσιν ῥίζῃσι καὶ αὐτοῖς ἄνθεσι μήλων.

I don’t have a sweet tooth, really. I think I’ll go and have some Marmite on toast.

Filed under: Loanwords, Word origins Tagged: Around the world in 80 words, Portuguese loanwords in English

December 9, 2015

“A while” or “awhile”; “for a while” or “for awhile”?

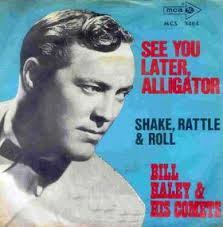

This catchphrase of the 1950s greatly amused my brother and me when very young.  Saying goodbye, you would gigglingly go “See you later, alligator” and the other person would reply “In awhile, crocodile.”

Saying goodbye, you would gigglingly go “See you later, alligator” and the other person would reply “In awhile, crocodile.”

Or should that be “In a while”?

If you google “In awhile, crocodile”, Google wags its finger at you and asks if you mean “in a while”.

That question goes straight to the crux. Is it “in a while” or “in awhile” (not to mention “after a while/awhile” “once in a while/awhile”, etc., etc.)

The spelling variation happens because there are two distinct “words”: the noun while, meaning “a period of time” and the adverb awhile, meaning “for a short time”.

The noun we use now descends from the Old English noun hwíl, first recorded in King Alfred’s translation of Boethius’ The Consolation of Philosophy, before 888, and is related to the modern German die Weile, meaning “while”.

The adverb awhile was, ironically, not written as two words until the thirteenth century and is a combination of the noun to give áne hwíle “(for) a while”. It is first recorded in Beowulf.

Summary

Following a preposition (e.g. after awhile), awhile is accepted in some US sources, but not in British ones, and is more common in North American English, though not unknown in British. (2.2, 3.2, 4.1-2)

Possible overgeneralization of the statement that “awhile is an adverb” means it is used in cases where most people would write “a while”. (2.3)

In many contexts there are two possible grammatical interpretations. (2.1, 4.3)

The verb used with the word/phrase can heavily influence the spelling as one word or two.

Is there a rule?

Various online grammar sites propose rules that can be summarized as follows:

1.1 Awhile is an adverb. Being an adverb, it modifies a verb. It means “for a short time”. Therefore, if you can replace it with the phrase “for a short time”, you are using it correctly:

We lingered awhile by the pool –> We lingered by the pool for a short time.

(The unspoken corollary of this is that after any verb awhile should be used, which is not true, as explained at 2.1 below).

1.2 If you cannot replace awhile with “for a short time”, you should write the two words separately. Therefore, “I’ll be with you in a while” is correct because otherwise you would have “in for a short time”, i.e. with two incompatible prepositions.

1.3 “A while” should be written as two words when it is is a noun phrase. Online examples given are a) “We have a while left to wait” (have requires a direct object, which ought to make it clear that while functions as a noun here), and b) “I saw her a while ago”.

1.4 As an adverb, awhile cannot follow a preposition, therefore “in awhile” is incorrect.

Such rules attempt to give simple, straightforward explanations. However, they can be somewhat circular. Write it as two words if it’s a noun – but how do you recognize it as a noun in the first place? Apart from the circularity, they do not seem to allow for:

2.1 It is not only words classed as adverbs that fulfil adverbial functions. You can also use noun phrases as adjuncts (of time duration), in which case certain prepositions are optional, e.g. l stayed there for a week/month/year, etc. Accordingly, it would be quite reasonable to interpret the sentence in 1.1 above as of this kind, i.e. “We lingered for a while by the pool”.

(The Oxford Online Dictionary recognizes this in its category 1.1 of while, with examples such as “Can I keep it a while?”)

2.2 Second, a sizeable minority of English speakers do in fact write “for/in/after/ etc. awhile”.

This use is recognized, for example, in the Merriam-Webster online usage note: “Although considered a solecism by many commentators, awhile, like several other adverbs of time and place, is often used as the object of a preposition awhile there is a silence — Lord Dunsany>.”

2.3 Third, adhering blindly to, or misinterpreting, the rule “if it modifies a verb”, often leads to uses like this, which many people would regard as wrong:

Conversely, “a while” as two words is often used following verbs, where the rule at 1.1 above states that it should be one word.

If you happen to walk down your local high street today, pause a Proustian moment by the open doorway of Greggs and linger a while.

Daily Telegraph, 2012

(For the benefit of non-UK readers, Greggs is a chain of food outlets selling economically priced sandwiches, cakes, etc. Hence the irony of the quotation.)

2.4 Certain adverbs can and do follow prepositions, e.g. since yesterday, for once.

Holy mackerel! So what do I write when, please!

3.1 You could test that you are dealing with a noun phrase. Try substituting another “duration” noun phrase in your sentence. In the example in the image above: “It just took me | some time / a few minutes / several hours / etc. to get loose and calm down”.

Using that substitution works for the sentences at 1.2 and 1.3: “I’ll be with you in| a while / a few minutes / seconds / etc. ”

“We have| a while / an hour / several hours / etc. left to wait”

“I saw her| a while / an hour / a day or two / etc. ago”

3.2 When it comes to prepositions, usage varies. To write “in awhile, for awhile, once in awhile” etc. is more frequent in American English than in British English. (See 4 for a few figures.)

The Merriam-Webster Concise Dictionary of English Usage gives it its blessing, and quotes several examples, e.g. …he had dosed it for awhile with an elm compress soaked in whiskey. Garrison Keillor, WLT: A Radio Romance, 1991.

In contrast, the OED (admittedly, the unrevised entry of 1885) categorically proclaims: “Improperly written together, when there is no unification of sense, and while is purely a n.”

You have been warned!

Its first quotation, from Caxton, in 1489, shows, however, that said “impropriety” has been around a very long time.

It was doon but awhyle agoon.

tr. C. de Pisan Bk. Fayttes of Armes i. xxiii. 72

Do usage and style guides help?

Neither the Economist, nor the Telegraph, nor the Guardian style guide mentions the issue.

The Chicago Manual of Style (16th edn) says, echoing online advice, but disagreeing with Merriam-Webster:

“awhile; a while. The one-word version is adverbial {let’s stop here awhile}. The two-word version is a noun phrase that follows the preposition for or in {she worked for a while before beginning graduate studies}.”

The M-W Concise Dictionary of English Usage allows for preposition + awhile, quoting examples with “for/after/once in awhile” and justifying this by referring to a comment in Quirk et al., 1985 that “some adverbs of time and place do occur after prepositions” (see 5).

The Cambridge Guide to English Usage, under the entry awhile, says that “More of its uses are sanctioned in the US” and concludes by saying that “Separating awhile into a while may seem to make too much of what is – after all – a vague time period.”

I suspect many editors would disagree.

Conclusion

For most people, the distinction probably doesn’t matter a tinker’s cuss. In contrast, many editors and writers will no doubt have firm views on the matter.

Although a while as two words far outnumbers awhile in the Oxford English Corpus, a minority use it in contexts where most people prefer the two-word form.

There are some contexts in which it seems impossible to come down firmly in favour of one spelling over the other (see 4.3)

4 A few facts and figures

From the Oxford English Corpus (March 2013 release)

4.1 As simple strings

awhile = 11,520 (10.4% of total occurrences)

a while = 98, 770 (89.6%)

Of those 11,520 awhile examples, 7,745 (67.2%) are North American (US, Canada) and 801 (7%) are British English.

Conversely, of the a while examples, 44,060 (44.6%) are North American, and 22,998 (23.3%) are British.

Taking all examples of both spellings, there is a marked difference: the North American percentage ratio of a while:awhile is 85:15% while the British is 96.6:3.4%

4.2 After certain prepositions

The combinations for/in/after a while/awhile broadly reflect the overall percentages, with the single-word spelling hovering round the ten per cent mark.

Turning to specific collocations, of the 4,874 examples of “for awhile”, 3,317 (68%) are North American and 270 (5.5%) British English. With “for a while”, this changes to 20,173 (42%) and 12,096 (25%).

The percentage ratios are therefore 85.9:14.1% for N. Amer. English and 99.4:0.6% for British English, i.e. even more marked for British English than for the overall ratio of the two forms.

4.3 In my mental lexicon at least, awhile still has a sub-poetic or quaint ring, collocating with verbs such as tarry, linger, and the like, or in rare set phrases such as not yet awhile.

However, in the Oxford English Corpus it collocates – though in fairly small numbers – with a range of verbs related to speech (chat, talk), relaxed states (rest, chill, sleep) and mental activity (muse, meditate). Its two most common verb collocates are wait and take.

For most of these verbs, it looks to me like a moot (British English meaning, i.e. debatable) point whether to interpret the combination as verb + adverb or verb + noun phrase used adverbially: people clearly do both.

Browsers take awhile to catch up to state-of-the-art from scratch.

The Mac Observer, 2012.

In this case, awhile as an adverb of duration could be compared with forever (though that’s the only one I can think of).

The results are impressive. The problem is that it can take a while to process the shot.

The Mac Observer, 2011.

In this case, a while could be replaced by another noun phrase, such as some time, quite some time, a few minutes, etc.

I can see no meaning difference between the two. Perhaps a wiser head than mine can. However, as 4.4 illustrates, the choice of verb does seem to have a marked effect on spelling.

4.4 The collocates of a while and awhile for all parts of speech are very similar, and similar in relative frequency, in a span of two preceding and one following word. When it comes to verbs, there are many overlaps but also some interesting differences.

4.4.1 The most frequent verb lemma with both is TAKE. It accounts for 47% of all verb collocations with awhile, whereas with a while the figure is 62%, which might suggest that TAKE exerts a strong influence on the two-word spelling, in line with while being interpreted here as its noun object. (See examples at 4.3.)

With SPEND, a while has 292 (96.4%) examples, awhile a mere 11, illustrating an even stronger influence than for take.

This is on page 99, at which point he’s spent a while seeking to disprove that god exists (no capital g for Him).

Daily Telegraph, 2013

This was after she spent awhile attacking me, of course.

Canadian English blog, 2004.

4.4.2 With the lemma WAIT, the percentage ratio of a while:awhile is 85.2:14:8%, i.e. a higher percentage of awhile than in the overall figures at 4.1.

We had planned on doing another mile or so by the River Hull but here the grasses on the floodbank were rank and it was like walking in knee-high snow. One can’t whinge, and this route can wait a while until the powerful herd of 25 creamy cattle have eaten their way through.

The Press (York, UK), 2005

But I suspect that Hillary Clinton will wait awhile until more of these precincts have reported.

CNN transcripts, 2008.

4.4.3 In contrast, with the lemma STAY, the ratio of a while:awhile is 56.4:43.6%, suggesting that STAY exerts a strong attraction for the single-word form.

4.4.4 Finally, with REST the split comes even closer to being 50:50, with 63 (52.5%) examples for a while and 57 (47.5%) for awhile, suggesting a very strong influence by the verb on the single-word form.

There is always something happening in a Glazunov symphony, even if you do feel that he could do with resting a while and taking stock.

Scotland on Sunday, 2004

Time to rest awhile before regaining strength ready for next week.

Boris Johnson, blog, 2005

4.5 In all the following examples, taken from grammarist.com, it seems to me that either spelling could be used, depending on where you are, and personal preference. However, the spellings shown reflect the tendencies previously described.

But if they give him The Tonight Show back, maybe it ends up all right after a while.

Starlings foray across the land and rest awhile on the sunlit twigs of ash.

After a while, Rawls came in to let another set of children have a chance.

Crazy Horse watched this awhile and then rode down the river where some men were going out to repair the talking wires.

We’ve been talking for a while when Baroness Campbell of Surbiton suddenly cuts to the chase, and leaves me speechless.

Beyond the bar, soft white leather booths beckon you to sit, take off your coat and stay awhile.

5 Quirk et al., 1985, 5.64, p. 282.

“A number of adverbs signifying time and place function as complement of a preposition.”

Because for and after often co-occur with a while, relevant examples taken from Quirk et al. are after| then/today/yesterday/now, and for| today/always/ever/once.

And here are Bill Haley and his Comets with the original song.

Filed under: Advice for writers, Business Writing Skills, Confusable words, One word or two?, Spelling Tagged: American Spelling, US & British usage

November 20, 2015

Bloody Mary and bloody Marys; why ‘bloody’, why ‘Mary’?

We all know that the wellies we might wear to go on walks through muddy fields are named after the first Duke of Wellington, the “Iron Duke”. Perhaps less well known is the link between the mac – in British English, at any rate – that we might also wear and its inventor, the deviser of the waterproof cloth from which macs are made, Charles Macintosh (1766–1843), the Scottish inventor who patented the cloth. Many units of scientific measurement, both everyday and more specialized, are named after their discoverers: the Italian physicist Count Alessandro Volta gave us volts, the Scottish engineer James Watt gaves us, er, … watts, and the Belfast-born Lord Kelvin gave his name to the units in which absolute temperature is measured.

Such words, derived from someone’s name, are technically called eponyms, a word created in the 19th century from the Greek epōnumos “given as a name, giving one’s name to someone or something”, from epi “upon” + onoma “name” (ἐπώνυμος; ἐπί + ὄνομα, Aeolic ὄνυμα name). The same Greek word for “name” has given English also anonymous and synonym(ous). And when people refer to the eponymous hero of such and such a novel, e.g. Fielding’s Tom Jones, they mean that the title of the novel is its protagonist’s name.

Bloody Mary

My favourite cocktail

If that image doesn’t make you thirsty, you’re a better person than me.

When I used to travel and be stuck in airport lounges in the evening, a Bloody Mary was often a little pick-me-up before the tedium of the flight home. Now I make them at home – very occasionally, you understand –, which is what set me thinking about the name.

Who is this Mary, anyway?

Frankly, it had never occurred to me that the Bloody Mary in question could be anyone other than Queen Mary (Tudor), whose brief reign (1553-1558) was proverbially “bloody”. During her campaign to re-establish Catholicism in Britain, some 300 people were burnt at the stake for heresy (including a few already buried who were dug up.)

Latimer & Ridley burnt at the stake, from Foxe’s 1563 1st edn. “Be of good comfort, and play the man, Master Ridley; we shall this day light such a candle, by God’s grace, in England, as I trust shall never be put out.”

(In fairness, in the reigns of her father, brother, and sister, human barbecuing was not unknown, but only on a minor scale in comparison.)

However, such is Mary’s notoriety that her sobriquet is translated into other languages, e.g. Marie la sanglante, Maria la Sangrienta, Marie die Blutige.

Wikipedia lists other pretenders to the name, including the silent-era Hollywood actress Mary Pickford and a waitress called Mary, but itsh true originsh sheem to be losht in the alcohol-shrouded mishtsh of time. Sho, I shall shtick with royalty.

If you are enjoying this blog, and finding it useful or interesting, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column, above the Twitter feed) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging semi-(ir)regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

When was Queen Mary first called “bloody”?

Mary’s portrait in the Prado, by Antonio Moro.

The first citation (1657) for “bloody Mary” in the OED comes from well after her reign. It appears in an Epistle Perambulation by the possibly somewhat demented millenarian John Rogers (b. 1627) to the curiously modern-sounding Time of End, by J. Canne, a non-conformist cleric.

We see it [sc. government] and feel it every day to be of the Beast, and more bruitish then those that have gone before; bloody Mary her self abhorring to make it Treason for words as they have done.

The OED also shows that “bloody Queen Mary” had earlier been used by the same John Rogers in 1654, in Sagrir or Doomes-Day Drawing Nigh:

Which Tyranny and accursed cruelty of theirs is condemned by bloody Queen Mary her selfe.

(The claim in the Wikipedia entry on the drink that it was in Foxe’s Actes and Monuments (“Book of Martyrs”) that Mary was first called “bloody” cannot be true, otherwise the recently revised OED entries mentioned above would have mentioned it. A search of the online editions, however, does reveal, for example, references to “the bloudy regiment of Queene Mary” (regiment here = rule, government, or reign).

The OED entry for bloody has no fewer than 15 senses (excluding its use as an intensifier) and bloody Queen Mary is cited bloodthirstily under meaning 4: “Of a person or animal: addicted to bloodshed, bloodthirsty; cruel”, a use that goes back to Old English.

What about the drink, then?

The OED’s first citation is from the N.Y. Herald Tribune for 2 December 1939. At that stage it seems to have been a simple half-and-half mixture:

George Jessel’s newest pick-me-up which is receiving attention from the town’s paragraphers is called a Bloody Mary: half tomato juice, half vodka.

If the OED is anything to go by, the drink took some time to cross the Atlantic – or at least to appear in print this side of the pond:

Those two…are eating raw steaks and drinking Bloody Marys.

Punch, 15 Aug., 1956.

Since the early days, Bloody Marys have become more complicated. The OED defines the drink as “A cocktail containing vodka, tomato juice, and other (usually pungent) flavourings, typically served with a celery stalk or similar garnish.”

Nowadays there are trillions of variations, with different alcohols, such as Tequila, and all manner of flavourings and garnish, from horseradish to olives, wasabi to bacon strips (personally, yuck!), oysters to clam broth.

Forgive me, but I like to keep mine simple at home: vodka, good tomato juice, celery salt, a teeny pinch of garlic salt, black pepper, Worcestershire sauce, Tabasco, a splosh of dry sherry, ice, and a slice of lime. (I’m too mean to buy the obligatory celery just for a drink!)

Mmmm, perhaps not that simple after all.

A Virgin Mary…

is the punningly alcohol-free version. The OED first records it from 1976, labels it “chiefly US”, and defines it as merely a glass of tomato juice. Later citations, however, show clearly that it’s a detoxicated Bloody Mary:

A waitress approached the table. ‘A Virgin Mary… A Bloody Mary without the vodka.’

Five Roads to Death, J. Philips, 1977.

This quote from a title published in England in London in 1981 conveys a certain British snobbishness about the name:

Crombie ordered himself a straight tomato juice with…Worcester. The Colonel did not, Bognor noted with approval, refer to the drink as ‘a Virgin Mary’.

Murder at Moose Jaw, T. Heald, 1981

Btw, the plural of Mary is Marys, not Maries.

It’s a standard spelling convention that if a common noun ends in a consonant plus the letter -y, you pluralize it like berry -> berries. However, most grammars agree that proper nouns are an exception; you just tack on an -s for the plural. For that reason, you write the Kennedys, the two Germanys, he has won six Tonys, etc. (although the alternatives spellings Kennedies, Germanies, etc. are also used.)

[In Scottish history, the four Marys are the girls of noble birth (the Marys Beaton, Seaton, Fleming, and Livingston) who accompanied Mary to France in 1548.]

by Hans Eworth, oil on panel, 1554

Bloody Mary has been vilified down the centuries. The Horrible Histories/Kate Bush parody redeems Mary from her ghastly reputation with tongue-in-cheek humour. The complete lyrics are below the link.

King Henry 8th my father hoped I’d have some Tudor brothers.

Mum had no sons,

So rather I got plenty of stepmothers.

When at last prince Ed was born,

The crown I bid adieu;

I said as king he must be sworn,

Boys go first in the queue.

But there’s no need to worry if at first you don’t succeed,

When Ed died

I swept aside the rest and was decreed…

Mary the first, that’s me,

Tudor lady and queen of England, not to be confused

With Mary Queen of Scots.

Not the same, see,

Though, weirdly, she’s a cousin to me.

Some tried to say Lady Jane Grey

Should be queen after Ed,

But England wanted me, hooray,

So poor Jane lost her head.

The Protestants were saying

That my ruling made them sick,

‘Cause when it came to praying,

My tastes were Catholic.

They revolted, challenged me, fuelled my great desire

To tie 300 to a stake,

Light touch paper then retire.

Mary the first, that’s me,

Called the bloody queen of England.

Not what I intended,

Tried to be

Good, you see,

But history only remembers

I was a catastrophe.

This magnificent classicizing bust of Mary’s husband Philip II does its best to disguise his inbred prognathous Hapsburg chin .

Married Philip king of Spain,

Who then left me.

England thought he was a pain,

Especially

‘Cause he told me

To attack France with troops

and when the French advanced

We lost Calais. Oops!

Throughout my reign it rained and rained,

It poured upon the poor,

The harvest failed, no food remained,

And flu killed many more.

Burned Protestants and wed a fool,

Led armies to defeat.

Burned more Prots, I say my rule

Was short but not that sweet.

I had no kids,

Named half-sis Liz

As big Queen Bess to be,

So long as she would rule the land

As a catholic queen like me.

Lizzie didn’t listen,

She made the country Protestant,

Meaning my legacy was ruined.

See everything I tried to achieve

Went down the swanny

Bit embarrassing really!

Filed under: Word origins,

November 6, 2015

Anymore or any more? Does anybody write anymore any more any more?

While Annie Lennox was keening ‘Don’t ask me why’ and lamenting lost or unachievable love, the question in this word geek’s mind (and perhaps in a few others’) was: is that ‘anymore’ or ‘any more’?

I don’t love you any|more

I don’t think I ever did.

And if you ever had

Any kind of love for me

You kept it all so well hid

One of my most often consulted blogs is about whereas as one word or two, so I thought it would be interesting to look at another case of split personality: any more and anymore.

What’s the problem?

When you want to convey the meaning ‘not … any longer’, e.g. ‘I don’t love you any more’ should you write any more or anymore?

In which uses of any more is it better to write the two words separately?

Quick answers

Whether you write ‘I don’t love you anymore’ or ‘any more’ largely depends on geography. The dataset (details later on) from the Oxford English Corpus that I used suggests that in British English there is a 2:1 preference for ‘any more’. In North American (i.e. US and Canadian) English, the one-word form ‘anymore’ is used in over 80 per cent of cases.

TIP: if you can replace ‘any|more’ with ‘any longer’, ‘again’ or some other paraphrase with a similar meaning, then it is safe to write it as one word if that is your preference. Also, look for the preceding verb that any|more relates to.

Any more should be written as separate words when you are using the phrase in one of six possible ways in comparative clauses – explained in detail below – where its grammatical function and meaning are different from those in ‘I don’t love you anymore’.

TIP: if the word than is in the near context of any more, it’s a fair bet that you should write the words separately, e.g.

…the book is very well written and does not assume any more than a basic knowledge of biology

The data suggests that, instinctively, most people separate the two words in such contexts, but occasionally they put them together.

There’s a separate, exclusively American meaning of anymore = ‘nowadays’ that will have to be the topic for another blog, sometime.

Menu

1 When two become one

2 Any|more as time adverbial

2.1 Examples

2.2 Regional preferences (Table)

2.3 Online dictionaries say…

2.4 Usage guides say…

3 Any + more: examples and explanation

3.1 Non-standard as single word

4 Dataset details

1 When two become one, or the urge to merge

While recently reading Fanny Burney’s Evelina (1778), for example, I couldn’t help noticing how often ‘any body’ and ‘every body’ appeared as two words.  Here is Evelina (Letter XXIII, completed text & images here) describing her visit to a concert at the Pantheon, a concert hall:

Here is Evelina (Letter XXIII, completed text & images here) describing her visit to a concert at the Pantheon, a concert hall:

There was an exceeding good concert, but too much talking to hear it well. Indeed I am quite astonished to find how little music is attended to in silence; for, though every body seems to admire, hardly any body listens.

To state the obvious, spelling is not fixed forever (or is that for ever?)

Some of the words we routinely write as one word nowadays, e.g. everybody, anybody as just mentioned, were regularly written as two at one time. The OED comments on anybody ‘formerly written as two words’ and has this quote from Disraeli that couples those two words: ‘Every body was there—who is any body.’ Vivian Grey, 1826.

To take a more current example, quite a few people write alot. Dictionaries do not yet accept this, but perhaps one day – presumably far in the future – they would, if it were to become the dominant spelling.

2 any|more as time adverbial

The OED (3rd edn) entry dates this use back to before 1338, but the earliest documentary evidence is from the Wycfliffite Bible Jer. iii. 1 If a man schal leue his wijf & she… wedde anoþer man, wheþer shal she turnen aȝeen any more to hym?.

The word(s), whether written as one or two, are a time adverbial meaning ‘to no further extent; not any longer’. You have to use them in (implicitly or explicitly) negative, or (negative) interrogative, clauses, and they are the equivalent of a clause containing ‘no…longer’.

The OED does give anymore as an alternative spelling, but the earliest citation of it in writing is in the ‘American’ meaning of ‘from now on, currently’: We’ll squeeze Michael a bit. He’ll chip in anymore. (1971)

2.1 Modern examples of the alternative spellings

I think these are good people trapped in a very difficult if not terrible situation with a process that they’re not even using anymore. CNN Your Money, transcripts, 2013 (US)

It’s such a shame that people don’t seem to have any common sense anymore. Daily Telegraph, 2013 (BrE)

The principle being that the Tories scuppered our reform of the Lords, and so waaaah, boo hoo, you horrid rotters, we’re not playing with you any more, we’re going home and we’re taking our ball with us. Daily Telegraph, 2013 (BrE)

Using the slogan, “We’re mad as cows and we’re not going to take it any more,” the group has collected more than 2,000 signatures of the 4,500 needed by July 7…’ The New Farm, 2004 (US)

2.2 Regional preferences

This table shows the percentages for the varieties of English available in the Oxford English Corpus. As you can see, the highest preference for ‘anymore’ is in American-continent varieties (US, Can., Carib.), followed by Asian & S. Afr. Englishes. Irish is more or less evenly balanced, and the variety which least favours ‘anymore’ is New Zealand.

Variety of English

ANY MORE

ANYMORE

ANY MORE (%)

ANYMORE (%)

RANKING BY ‘ANYMORE/ANY MORE’ PREFERENCE

British

1,600

892

64.2%

35.8%

10

unknown

890

1,198

42.6%

57.4%

7

American

794

4,065

16.3%

83.7%

2

Australian

339

273

55.3%

44.7%

9

New Zealand

229

71

76.8%

23.2%

11

Irish

132

147

47.3%

52.7%

8

Indian

113

214

34.6%

65.4%

5

East Asian

73

237

23.5%

76.5%

4

Canadian

51

312

14%

86%

1

South African

48

72

40%

60%

6

Caribbean

14

55

20.3%

79.7%

3

2.3 Online dictionaries say…

The Oxford Online Dictionary, British & World English version, gives the two-word form under any, with the alternative ‘anymore’. But if you look up anymore as a solid, it is labelled ‘Chiefly N Amer variant of any more’.

If you use the US version of that dictionary, and enter ‘any more’ the entry you will find is anymore with the variant (also any more).

The UK-based Collins, in its British English version, gives you ‘any more or (especially US) anymore’, but if you look up ‘any more’ in the US version, the same thing happens as with Oxford: you are directed to the entry anymore, with ‘any more’ as a variant.

With Merriam-Webster online, if you enter the two-word form, you are immediately taken to the single-word one. In addition, there is a note stating: “Although both anymore and any more are found in written use, in the 20th century anymore is the more common styling. Anymore is regularly used in negative anymore — May Sarton>, interrogative anymore?>, and conditional anymore, I’ll leave> contexts and in certain positive constructions anymore in solutions — Russell Baker>.

2.4 Style & usage guides say…

Telegraph style book: any more/anymore: we do not want any more errors in the newspaper; we will not put up with this anymore

Guardian Style Guide: Please do not say “anymore” any more

The Economist does not cover it, nor does the Chicago Manual of Style (though its page on Good usage versus common usage has single-word anymore in an unrelated entry, thereby, presumably, endorsing it).

The Merriam-Webster Concise Guide to English Usage does not mention it, but Pam Peters does, in her Cambridge Guide to English Usage. She comments on the US/British difference and says ‘But anymore (as adverb) tends to be replaced by the spaced any more in formal British style.’

3 Any + more as two words

Any + more as two words is appropriate in a range of comparative clauses, either followed explicitly by than, or with an implied comparison.

TIP: It’s a fair be that if you’re writing something and follow any more with than in the next few words, writing it as two words is correct.

Similarly, if you follow any more with of as in 2) below, or an adjective, an adjective plus noun, or an adverb + adjective + noun as in 4-5) below, it should be two words.

In all cases, any is being used as a ‘submodifier’, comparable to other words such as, e.g. she is far/considerably/much/vastly + more + adjective, e.g. talented/sophisticated/wealthy, etc + (than)…

The cases in which any + more is two separate words are:

1 more as a determiner (i.e. followed by an uncount or plural count noun, according to the usual rules for more):

My place is wherever America’s enemies are, to kill them before they kill any more Americans on our own soil. Empire of the Ants, 2004 (US)

…nothing that points directly at Chris Christie as having any more involvement than he said he did. The Situation Room, CNN Transcripts, 2014

…vertical integration takes place only for reasons of technological efficiency because it does not involve any more or less monopolization than what existed in the preintegration period. Jrnl of Agricultural and Applied Economics, 2005 (US)

This Cambridge Dictionary link explains this basic point.

2 more as pronoun – often followed by of:

Overall, the book is very well written and does not assume any more than a basic knowledge of biology. NACTA Jrnl, 2005 (US)

He took it upon himself to say ‘I am not going to stand any more of this messing about’. Irish Examiner, 2002

The changes do not make this opera any more of a masterpiece; Bizet ‘s music is still linked to a profoundly unsatisfactory libretto. MV Daily, 2003 (US)

3 any more as adjunct:

Mass production and high levels of craft detail do not usually go together, any more than low-budget buildings are tolerant of too many non-standard details. The Architectural Review, 2000 (AmE)

It still seems necessary to tell the country ‘s history, but the politics will not adhere to the art any more than it did for Wolfflin. Art Bulletin, 2000. (US)

4 more modifying adjective:

a) as subject/object complement

This activity did not make me feel any more despondent than usual, nor did I experience a loss of appetite or a tingling sensation in my lower extremities. Weekly Eye, 2003 (Canada)

Good designers may not be any more talented than you, they are just more aware of their surroundings. Art Business News, 2001 (US)

4 b) premodifying noun group

There can’t be any more horrifying images than the aftermath of Hiroshima or the mass slaughter of Chilean civilians under Pinochet. Senses of Cinema, 2003 (Austr.)

I really have not given it any more detailed consideration than that because I did not see it as relevant to the point. High Court of Australia transcripts (2001)

This work , informal and more up to date in concept than anything conceived by such established sculptors as Rysbrack or Scheemakers, was not immediately followed by any more large works. Oxford Companion to Western Art, 2001 (BrE)

5 any more modifying adverb

…the subjugation [ ] of music’s powers of expression results in a poignant intensity not to be realised by any more overtly pathetic means.’ Musical Times, 2004 (US)

3.1 Non-standard uses of anymore

Yow! I will not be giving them anymore business. Blog, 2004 (Carib.) [see Examples 1 above]

I forgot in my thanks that I had decided not to use anymore bottles of bought water. Blog, 2007 (Austr.) [See Examples 1]

But the scandals and controversy do not overwhelm this Carroll saga anymore than it did the Carrolls themselves. Economic History Services, 2001 (US) [See Examples 3]

But this did not seem to help anymore than a cigarette or a glass of wine would have. Namibia Economist, 2003 (SAfr.) [see Examples 3]

4 Dataset details

The dataset I used for the figures given earlier does not cover all possible cases of any|more as a time adverbial – life’s too short – but it does cover a very frequent use of it, amounting to almost 12,000 examples. Using the Oxford English Corpus of 2.5 billion words (i.e. tokens), I carried out a fairly crude search for the word NOT + 1-4 words + ANY MORE and separately ANYMORE.

I then filtered out certain some obvious elements, such as than, or any more + adjective. The remaining examples were not 100% time adverbials, but nearly all of them were, and I’m happy that, since I applied the same filters to both searches, the proportion of irrelevant sentences for each search should in principle be the same.

Obviously, choosing not rather than the contracted forms is likely to extract more formal language. However, a quick check using -n’t suggests very similar figures.

Filed under: Business Writing Skills, One word or two?, Spelling Tagged: American Spelling, US & British usage

September 26, 2015

Lording it over – or lauding it? All glory, laud, and honour

Quick takeaways

If you laud someone, you praise them.

If you lord it over someone, you treat them arrogantly and in a domineering way.

Very occasionally, lorded seems to be used for lauded.

Conversely, and rather more often, laud (in all inflections) seems to be used for lord, which I find more difficult to explain semantically. However, this eggcorn goes back at least to the 19th century.

Perhaps someone can help.

You should be lorded because…

(No, the above is not from a conversation between a member of the government and a Tory party donor.[1])

In a recent Daily Express online article (ok, I know, I know, an organ that is not necessarily the guardian of the nation’s orthography), my eye was caught by the juxtaposition of a standard spelling and an eggcorn.

In the body of the article, someone was quoted as saying “You should be lauded because you’re wearing uniform, you should be celebrated for wearing uniform.” But the summary box at the side (I don’t know what you call that; somebody will no doubt enlighten me) had “You should be lorded because you’re wearing uniform.”

(Interestingly, when I looked again after a few hours, the mistake had been corrected, possibly by a vigilant sub-editor, if such people still exist)

Inevitably, this set me wondering whether this was a complete one-off, or a more widespread homophone eggcorn. I couldn’t find it in the main online eggcorn database, so I decided to do a bit of my own linguistic gumshoeing.

Remind us. What’s an eggcorn, again?

In case any gentle readers have forgotten what an eggcorn is, here’s the OED definition: “An alteration of a word or phrase through the mishearing or reinterpretation of one or more of its elements as a similar-sounding word.”

And for those who have forgotten (wake up, you at the back!) what a homophone, as opposed to a homophobe, is: quite simply, it is a word pronounced identically to another one that has a different spelling. The classic case is, of course, the dreaded their/there/they’re.

(For those who wish to pursue the topic, here’s a link to a Grauniad list of homophone confusions.)

Why this eggcorn makes sense

The OED definition misses out a crucial feature of eggcorns: they are not arbitrary or random (in the older sense of that word). The change has to be semantically and grammatically justified — at least in the mind of the eggcorner. As for ‘lorded’, a) if you use lord as a transitive verb, as in the current example, you make someone a lord, i.e. you are putting them in an exalted position, so that makes sense; b) the verb to lord exists, though it is nowadays intransitive, and is probably a part of most people’s vocabulary. All in all, this eggcorn makes perfect sense. But, is it truly a hapax? The answer is no.

I like being lorded. Who doesn’t?

First, I looked in the Oxford English Corpus. It throws up 1,699 occurrences of lord as a verb. If you filter out the word over in a five-word window either side (on the assumption that if used with over it couldn’t be an eggcorn for laud) that reduces the number by about half (to 841), but a quick scan of those remaining citations did not reveal any as an eggcorn for lauded.

However, a search on Google for be lorded minus ‘over’ (to filter out the passive use of ‘to lord it over someone’) does throw up a few echt eggcornisms, such as:

“Like many organizational processes, socialization and prestart training may simply be lorded as positive features of the organizations [sic] human resource …”

And in a comment on a Bradford Herald & Argus article of 27 July 2015 about new investment in the city centre:

“Any other city in the country this would be lorded as a big investment and showing confidence in the city.”

So, while rare, this eggcorn is not unique [2].

Don’t laud it over me!

What surprised me, however, is that in the OEC data laud appears to be more often used for lord than the other way round. A search for laud as verb followed immediately by it produced 77 examples, of which 7 were eggcorns, e.g.:

“So confident was Blair of this that he lauded it over his critics , sneering before parliament…”

A Google Ngrams search unearths plentiful examples of the eggcorn this way round, in a wide range of texts, including novels by Catherine Cookson and Barbara Taylor Bradford.

More surprising to me was that this form goes back to the nineteenth century, often appearing in religious tracts of various kinds:

A demagogue trying to “laud” it, but not seeming to have much success.

“…that ambitious and seditious demagogues might laud it over the throne, and the aristocracy; and bow the neck of the lordly and the mighty to their unhallowed yolk.”

Truth’s Advocate against Popery and Fanaticism, 1822.

“What has become of your self-complacency? Where the pride and the lauding it over your poor fellow-sinner?”

The Gospel magazine, and theological review. Ser. 5. Vol. 3, no. 1 July 1874

The only explanation I can think of for laud it over in those days is this, but hope someone can supply a better one.

Laud meaning praise is a word used principally in religious contexts;

People in the nineteenth century would have been familiar with it in that context;

If they heard but never read ‘lord it over’, they would learn it as an idiom, a gestalt, and slot the word they knew – laud – in;

For US writers, lord referring to the aristocracy would not be in their active vocabulary, and this might have helped block that analysis of the phrase.

Convinced? I’m not, but it’s as good a guess as any.

All glory, Lord, and honour

The correct version is, of course, All glory, laud, and honour, to thee, Redeemer, King.

I remember first singing this, with its simple, stirring tune at school. But I have to confess that if I hadn’t been learning Latin and hadn’t seen the words written down, I would have interpreted it as ‘Lord’. And that is what many people do, as a Google search will quickly show [3].

Lauds

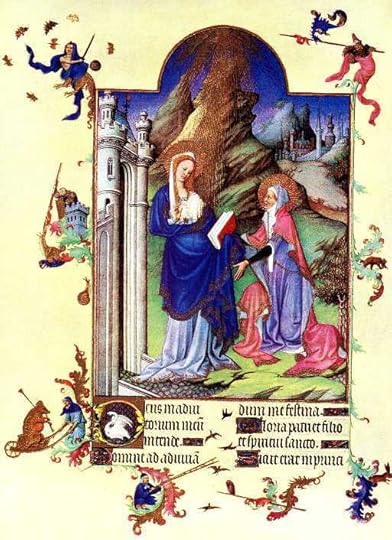

From the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. In Books of Hours, a portrayal of the Virgin being visited by her cousin Elizabeth was often placed at the beginning of the section on Lauds.

Lauds is “A service of morning prayer in the Divine Office of the Western Christian Church, traditionally said or chanted at daybreak, though historically it was often held with matins on the previous night”. It is one of the parts of the daily round of prayer: matins, lauds, prime, terce, sext, none, vespers, compline. Auden wrote a sequence of poems about each one (excluding matins) including Lauds, with its echoic stanza pattern and unusual serpent-biting-its-tail ending.

Among the leaves the small birds sing;

The crow of the cock commands awaking:

In solitude, for company.

Bright shines the sun on creatures mortal;

Men of their neighbours become sensible:

In solitude, for company.

The crow of the cock commands awaking;

Already the mass-bell goes dong-ding:

In solitude, for company.

Men of their neighbours become sensible;

God bless the Realm, God bless the People:

In solitude, for company.

Already the mass-bell goes dong-ding;

The dripping mill-wheel is again turning:

In solitude, for company.

God bless the Realm, God bless the People;

God bless this green world temporal:

In solitude, for company.

The dripping mill-wheel is again turning;

Among the leaves the small birds sing:

In solitude, for company.

1 As a transitive verb, to lord can mean to make someone a lord, though this use is archaic.

2 I sometimes wonder if there any totally unique [please don’t tell me I can’t qualify ‘unique’] eggcorns.

3 Google also showed me a version titled ‘All glory, praise, and honour’, presumably because laud is such an archaic word.

Filed under: Advice for writers, Confusable words, eggcorns, Spelling, Word origins Tagged: Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, Sir John Tenniel, W.H. Auden

September 6, 2015

Alice bands and Alice in Wonderland

We all know that the wellies we might wear to go on walks through muddy fields are named after the first Duke of Wellington, the “Iron Duke”.  Perhaps less well known is the link between the mac – in British English, at any rate – that we might also wear and its inventor, the deviser of the waterproof cloth from which macs are made, Charles Macintosh (1766–1843), the Scottish inventor who patented the cloth. Many units of scientific measurement, both everyday and more specialized, are named after their discoverers: the Italian physicist Count Alessandro Volta gave us volts, the Scottish engineer James Watt gave us, er, … watts, and the Belfast-born Lord Kelvin gave his name to the units in which absolute temperature is measured.

Perhaps less well known is the link between the mac – in British English, at any rate – that we might also wear and its inventor, the deviser of the waterproof cloth from which macs are made, Charles Macintosh (1766–1843), the Scottish inventor who patented the cloth. Many units of scientific measurement, both everyday and more specialized, are named after their discoverers: the Italian physicist Count Alessandro Volta gave us volts, the Scottish engineer James Watt gave us, er, … watts, and the Belfast-born Lord Kelvin gave his name to the units in which absolute temperature is measured.

Such words, derived from someone’s name, are technically called eponyms, a word created in the 19th century from the Greek epōnumos “given as a name, giving one’s name to someone or something”, from epi “upon” + onoma “name” (ἐπώνυμος; ἐπί + ὄνομα, Aeolic ὄνυμα name). The same Greek word for “name” has given English also anonymous and synonym(ous). And when people refer to the eponymous hero of such and such a novel, e.g. Fielding’s Tom Jones, they mean that the title of the novel is its protagonist’s name.

A male-dominated field

As in so many areas, when it comes to items of apparel [*] or ornament there is a severe gender imbalance. While the list of male-named clothes includes wellies, cardigans, knickers, leotards, raglan sleeves, Nehru jackets, Mao collars, Van Dyke collars, Prince Alberts, etc., the roll call of those named after women is rather shorter. One that easily springs to mind is Alice band.

Alice band – a flexible hairband of cloth, elastic, plastic, or other material that women and girls wear to keep their hair in place.

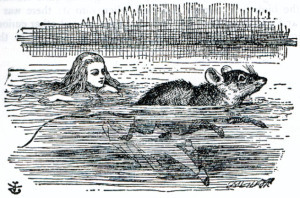

The Alice in question is the protagonist of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) [AAIW] and Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found there [TL-G] 1871. The term was obviously inspired by (Sir John) Tenniel’s (1820-1914) illustrations, but was first recorded only as late as 1944, at least according to the OED.

Now you see it, now you don’t.

Alice in Wonderland vs Through the Looking Glass

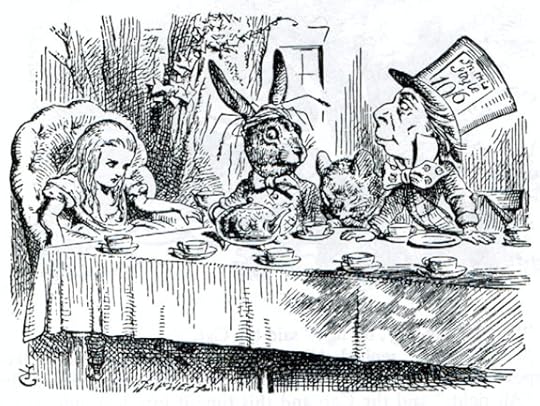

In Tenniel’s illustrations (woodblock engravings) for AAIW, Alice is not once portrayed wearing anything in her hair. In the whole text the word hair is only mentioned seven times, including at the Mad Tea-Party (often known as the “Mad Hatter’s Tea Party”, though Carroll did not use the phrase “mad hatter”)

“Your hair wants cutting,”

said the Hatter. He had been looking at Alice for some time with great curiosity, and this was his first speech.

“You should learn not to make personal remarks,”

Alice said with some severity;

“it’s very rude.”

The Hatter opened his eyes very wide on hearing this; but all he said was,

“Why is a raven like a writing-desk?”

[**]

Nearly at the very end of the story, Alice’s older sister (who is nameless) also falls into a dream, in which “she could hear the very tones of her [Alice’s] voice, and see that queer little toss of her head to keep back the wandering hair that would always get into her eyes”.

In TL-G, where Alice’s hair plays a more important role,  Alice is uniformly presented as having her formerly unruly hair kept in place by what looks like a broad ribbon tied in a neat bow. Such a hairstyle seems to have been standard for Victorian girls at the time.

Alice is uniformly presented as having her formerly unruly hair kept in place by what looks like a broad ribbon tied in a neat bow. Such a hairstyle seems to have been standard for Victorian girls at the time.

In 1890, Tenniel selected, adapted and added colour to 20 of his original illustrations from AAIW for a nursery version (complete set of images at the British Library: here). Perhaps by this stage Alice’s ribbon or headband had become an integral part of her image: at any rate, Tenniel added one, which the original illustration lacked, as well as making changes to Alice’s dress. [***]

Illustration from The Nursery Alice.

Illustration from AAIW.

A male accessory?

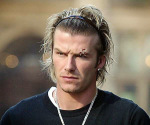

But Alice bands are not worn only by women or girls. Footballers with long hair also wear them to keep their locks out of their faces when playing the beautiful game. The first sleb footballer to have worn one seems to have been uber-metrosexual David Beckham  . Others have emulated him, including Ronaldo. But the fashion is still hardly mainstream: when Gareth Bale wore one, it was newsworthy enough – at least in the eyes of the journo who wrote it – to merit comment on The Independent’s website.

. Others have emulated him, including Ronaldo. But the fashion is still hardly mainstream: when Gareth Bale wore one, it was newsworthy enough – at least in the eyes of the journo who wrote it – to merit comment on The Independent’s website.

Tangentially, there is also a question of definition: when does an “Alice band” become a “headband”? It must be all to do with the width of the band, as in this photo of Nadal.

After all, what man is going to buy an Alice band when he can buy a headband?

[*] Another of those myriad British/US English differences. Apparel sounds quaint & poetic in BrE, but is a standard word in US English used by shops where BrE would use “clothing”: a sale on summer apparel for women. There is even a verb: a designer who regularly apparels several of the presenters at the Oscar ceremonies. (Both examples from Merriam-Webster online.)

[**] Answer to the Hatter’s riddle: Lewis Carroll’s Author’s Note: Christmas, 1896. “Enquiries have so often been addressed to me, as to whether any answer to the Hatter’s Riddle … can be imagined, that I may as well put on record here what seems to me to be a fairly appropriate answer, viz. ‘Because it can produce a few notes, though they are very flat ; and it is never put with the wrong end in front!’ This, however, is merely an after-thought : the Riddle, as originally invented, had no answer at all.”

[***] It seems that Carroll gave Tenniel very precise instructions about the illustrations. Until I did some online digging for this blog, I was unfamiliar with Carroll’s own illustrations for the forerunner of AAIW, Alice’s Adventures under Ground. Many of them foreshadow the better-known Tenniel versions, as here, and illustrate how a great graphic artist can turn a rough sketch into a compelling image:

Lewis Carroll’s sketch.

Tenniel’s version.

Filed under:

August 29, 2015

dryly or drily, slyly or slily? A spelling conundrum

A young Zambian girl and boy smiling shyly.

What’s the issue?

The other day I was writing this sentence: “The exotically handsome man in the corner lowered his Arabic newspaper and smiled shyly at her.”

I had to pause to think about the spelling of “shyly”. Was that right, or should it be “shily”?

But the second one looked very, very odd to me. A quick check in the Oxford online dictionary (British & World English) confirmed that the -yly spelling was indeed correct.

How many words are affected?

That set me thinking, though, about which other adverbs were affected. The obvious one – well, perhaps not that obvious, because none of these words are/is particularly frequent – was dryly/drily, and the only other one I could think of off the top of my head was slyly/(slily?).

The OED has since come to my aid by adding wryly to those. It also lists two opposites (unshyly and unslyly) as well as some curiosities. (I’ve put a couple at the end. As so often happens, the OED citations suggest some delightful [to me, at any rate] historical asides.)

OK, aren’t I fussing about superminutiae, you might ask. Yes and no. There is a generalizable spelling rule that piqued my curiosity, and, apart from anything else, I wanted to refresh my understanding of it.

What’s the spelling rule?

That spelling rule, as formulated in the Oxford A-Z of Spelling, is:

“When adding suffixes to words that end with a consonant plus -y, change the final y to i (unless the suffix already begins with an i).”

Using its examples, that gives us pretty -> prettier -> prettiest

ready -> readily

beauty -> beautiful

The rules also apply to the inflectional verb morphemes -s, -ed, -ing added to verbs ending in -y, thus giving us, on the one hand, defy -> defies, defied, deny -> denies, denied, and on the other defying, denying.

Them be the rules. But there is a certain fuzziness affecting a few words apart from the adverbs already mentioned: dryer vs drier and flyer vs flier come to mind. And American and British usage seem to be different, as dictionaries illustrate below. So, it constitutes yet another of those trillions of subtle differences between American and British English that can flummox the unwary.

So, why are shyly, slyly, etc. exceptions to the rule?

The final letter -y of many adjectives – pretty, crazy, noisy, etc. – represents a ‘short’ unstressed i sound, i.e. /ˈprɪti/. When the adverb suffix is added, it changes slightly to /ˈprɪtɪli/ but it’s still an i sound. But the -y in shy, sly, etc. represents a different /ʌɪ/ sound, e.g. /ʃʌɪ/. The more common pattern for adverbs is the first (around 500 examples in the OED), which presumably sets up the expectation that the spelling -ily is to be pronounced /-ɪli/. And that just jars with what we know about the pronunciation of dry, etc. as an adjective by suggesting the anomalous /drɪli/.

If you are enjoying this blog, and finding it useful or interesting, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column, above the Twitter feed) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging semi-(ir)regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

What do dictionaries say?

Oxford online (UK): drily (also dryly); shyly; slyly; wryly

Oxford online (US): dryly (also drily); as above

Collins online (UK): drily or dryly; shyly; slyly, slily; wryly

Collins online (US): dryly; shyly; slyly; wryly

Merriam-Webster online: drily or dryly; shyly; slyly also slily; wryly

OED unupdated entries give: dryly | drily and slyly | slily as alternative headwords; shyly (also shily); wryly (also 15-16 [i.e. 1500s, 1600s] wrily)

The Oxford Canadian dictionary gives dryly (also drily), whereas its Australian companion gives drily (also dryly).

(NB: there are also differences in what dictionaries show for comparatives and superlatives of adjectives, e.g. shyer/shier, shyest/shiest, but I’m trying to keep this short(ish), though I inevitably end up being prolix.)

Historically, it looks as if writers have for a long time wavered between the two spellings. For example, the 14 OED citations for dryly/drily divide into dryly (5), drily (7), driely (1), dryely (1).

Take Our Poll

Corpus to the rescue