Jeremy Butterfield's Blog, page 22

September 16, 2016

Guerrilla or gorilla? What is “guerrilla marketing”? And where does “guerrilla” come from?

Do you puzzle over whether it is “guerrilla marketing” or “gorilla marketing”?

And if you write guerrilla, do you have to check how many r’s it has? (If you don’t, you’re a better speller than me.)

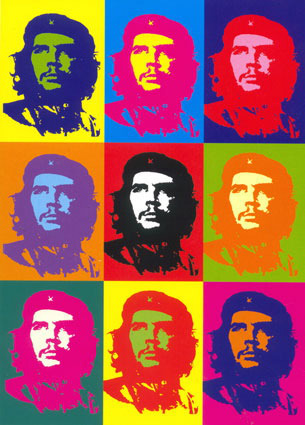

Warhol’s icon of Che Guevara, a legendary guerrilla.

In English it can be either guerrilla or guerilla, according to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) — mind you, the spelling with two r‘s is much more usual.

It’s not just English speakers who can’t decide how many r’s; some Spanish speakers have the same problem, even though it is a current Spanish word, and clearly must have two r’s for reasons we’ll go into in a minute.

And that uncertainty can get right under some people’s skin.

This hideous tattoo should read “Dios bendice mi familia” “God blesses my family”: b and v sound identical in Spanish.

In 2016, the official language body in Colombia launched a hashtag campaign offering the services – gratis — of professional tattooists to retattoo (makes my flesh crawl) misspellings shown on photos of their own tattoos that people were invited to submit. One of the orthographically challenged tattoos bore the misspelling – in Spanish, that is – guerilla, with a solitary letter r.

Why “guerrila marketing”, etc.?

Like so many loanwords in English, guerrilla has taken on a life all of its own.

In warfare, guerrillas use unconventional tactics, fight alone or in small groups, do not recognize authority, and can pop up anywhere without warning. Since the late 20th century, the word has been freely used to apply those very characteristics to actions in peaceful spheres that flout established social norms.

Take guerrilla marketing or advertising, that is, marketing/advertising aimed at achieving maximum exposure at minimum cost, using innovative techniques and avoiding traditional media.

(The first citation for guerrilla advertising, in 1888, is a lot older than you might expect, but then the word seems to have gone quiet for nearly 80 years.)

I don’t see how you can get much more guerilla than this…

Guerrilla marketing…involving the dispatch of streakers or nearly-nude nutcases to high profile events with the company’s web address tattooed on bare skin.

Independent, 7 June 2005

New to me is guerrilla gardening:

Landless residents…decided to plant trees and other food crops on public land. Fortunately, the council did not object to this growing trend that is known as guerrilla gardening.

BBC ‘Countryfile’, Feb. 12, 2010

And if I could knit, I might be tempted by guerrilla knitting:

The woolly displays are part of the wider trend of guerrilla knitting, a type of benign vandalism in which enthusiasts leave knitted creations on lampposts, railings and road signs.

“Benign vandalism” is such a lovely oxymoron, don’t you think?

Also known as “yarn bombing.” Very pretty, but does it harm the trees?

Of course, thanks to that tricksy old sound the schwa, guerilla sounds exactly like…gorilla. If you don’t believe me, in phonetic notation they are both /ɡəˈrɪlə/. (That letter e doing a Yogic headstand is the schwa, and stands for the unstressed “uh” sound.)

Because they sound the same, people sometimes mistakenly write gorilla marketing. As a British online wag quipped: “Is that when you have King Kong promote your product?”

A Manchester-based (UK) SEO company punningly has the misspelling as its name, a gorilla as its logo, and the strapline “It’s a jungle out there.”

Koko, the “talking” gorilla, with her pet kitten.

Guerrilla: the word’s backstory

The word guer(r)illa has become so “English” that it is easy to overlook its Iberian origins, which date to the time of the Peninsular War (1808–1814) against Napoleon.

In 1808, Napoleon turned on Spain, previously his ally, an event which ushered in a prolonged period of violent and prolonged national and nationalist struggle against the French. In some ways, that period can be viewed as the first modern war of national liberation.

The central administration of the Spanish State was in complete disarray, and local juntas (another Spanish word) took it upon themselves to help organize resistance. That resistance was largely in the hands of civilians, loosely organized in militias, who avoided pitched battles and either harassed French troops on the march or fiercely defended cities under siege.

“The Defence of Saragossa”, Sir David Wilkie, 1828, The Royal Collection.

Those militias were known as guerrillas. Their heroic defence of their homeland (la patria), notably in the legendary siege of Saragossa, really captured the British public’s imagination.1

At the request of three of the juntas, the British sent troops under the command of the then Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Wellesley,

Wellesley bedecked with medals, painted by Goya, and looking hesitant and untriumphal (1812-1814, National Gallery, London).

better known to us as the Duke of Wellington . It is in his dispatches of 1809, according to the OED (which gives only the year, not the month or day) that the word makes its first appearance in English.

I have recommended to the Junta to set…the Guerrillas to work towards Madrid.

The meaning here as defined by the Oxford Dictionary Online is “A member of a small independent group taking part in irregular fighting, typically against larger regular forces.”

“little war”

The word for “war” in Spanish is guerra (ignore the u, and pronounce the vowels as in guess). Adding –illo or –illa, classed as a “diminutive suffix”, to a word often implies smallness or littleness, so guerrilla is in very literal terms a “little war.”

According to the Spanish Royal Academy’s historical corpus, the word first appears in the classic account of the Spanish conquest of the Americas, Fray Bartolomé de las Casas’ History of the Indies meaning precisely, and somewhat disparagingly, a “little war”, for example:

“They had some little wars about the borders and boundaries of their lands and dominions, but all of them were like children’s games and were easily calmed.”2

A traditional Spanish dish makes use of the same suffix: gambas al ajillo, succulent prawns in a tangy garlicky sauce. Ajo is the word for “garlic”, and ajillo refers to chopped garlic and the sauce made from it. And of course, just about any British tapas restaurant is bound to offer Spanish omelette, tortilla, which adds –illa to the word torta.

Gambas al ajillo. Yum!

1The Scottish Sir David Wilkie, who was the “Royal Limner” (i.e. painter) in Scotland, was one of the first professional artists to visit Spain after the War of Independence, and was deeply influenced by seeing the paintings of Velázquez and Murillo.

2Algunas guerrillas tenían sobre los límites y términos de sus tierras y señoríos, pero todas ellas eran como juegos de niños y fácilmente se aplacaban.

Filed under: Confusable Words, Learning Spanish, Meaning of words Tagged: Spanish words in English, Zen to Aardvark

September 14, 2016

Thirty commonly confused words in English

Dozens of words are all too easy to confuse. Their’s [sic] the notorious case of its’s/its, not to mention there/they’re/their, your/you’re, and other obvious spelling mistakes caused by two words sounding the same, that is, being homophones as they’re known in the trade.

But then there are a host of others which are less frequently used, or are used mostly in formal or literary writing and in journalism. Since some readers of those genres undoubtedly love to pounce on any mistakes, it could be embarrassing to write one instead of the other.

If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

“All the evidence suggests…”

This is not a list of my subjective bugbears and personal tics. (How very dare you suggest that I have any such thing!) Far from it. It is based on what I’ve noticed in reading or editing over the years, and on what I’ve heard/hear. I have corroborated that observation/listening in the first place by seeing how often these pairs are discussed in online editorial forums and how often questions about them are entered as Google searches.

Second, for many of these posts I have looked at corpus data — chiefly from the Oxford English Corpus, but also from other corpora — to get an idea of how widespread the phenomenon of — let’s call it “meaning swapping” — is, and what its geographical spread might be.

Looking at data not only counterbalances the “frequency effect” (i.e. once we’ve noticed and mentally noted a linguistic occurrence, we see it everywhere), it can also produce surprising results: what BrE speaker would have thunk that, as far as I can see, hone in is now the “norm”, not only in US English but in nearly all varieties?

Apart from looking at corpus evidence, I have also often noted what dictionaries and usage guides say about the question so that you, gentle reader, can make up your own mind.

Why bother?

You mean, “Wotevah! Why bovver, whichever version people use?”

Lots of people have that laissez-faire attitude, but quite a few people are bovvered — sometimes very, very bovvered. And people, such as editors and proofreaders, whose business it is to “correct” others’ writing, earn their living by being bothered.

Those people who Google questions about these pairs may not be particularly bothered, but they are, at the least, curious to find an unequivocal answer. In fact, after — sigh, “what is the first word in the dictionary” — the most common search terms that bring people to this site are “whereas or where as”, “defuse or diffuse” and “ascribe to or subscribe to.”

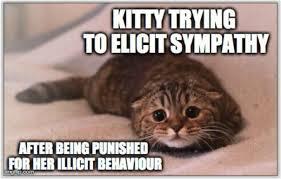

Here’s a feline-themed homophone.

As you can see, they’re a very mixed bag as regards meaning. What links nearly all of them, though — with the exception of coruscating/excoriating — is the very close similarity between the member of the pair. In some cases, just like they’re/their/there, but depending to an extent on accent, they are true homophones, e.g. veracious/voracious, illusive/elusive.

Here’s the complete list in alpha order:

adverse to / averse to

ascribe to / subscribe to

cache / cachet

coruscating / excoriating

decry / descry

defuse / diffuse

elicit/illicit

elusive / illusive (illusory / allusive)

flaunt / flout

home in on / hone in on

peek / peak / pique

veracious / voracious

wave / waive / waiver

whereas / where as

There are plenty of others; I may add them to the list as time goes on.

phase / faze (verbs)

Yet another homophone glitch. If something is phased, it is done in stages (i.e. phases) over a period of time:

Yet another homophone glitch. If something is phased, it is done in stages (i.e. phases) over a period of time:

e.g. the work is being phased over a number of years;

a phased withdrawal of troops.

If something fazes you, it disconcerts you in such a way that you do not know how to react:

e.g. She’s been on the stage since the age of three so nothing fazes her at all.

In the next example, the wrong one has been used:

Cox is unlikely to be X phased by the prospect of going for gold in Athens , having been a record breaker at the tender age of 11–BBCi Sport, 2004 Olympics.

exasperate / exacerbate

Not homophones this time, but similar enough in sound to cause confusion. If someone or something exasperates you, they annoy you greatly and make you feel frustrated

e.g. Speed bumps definitely do make you slow down, and taxi drivers take sadistic pleasure in exasperating their passengers by coming almost to a halt in front of them;

But speculation that he may quit Britain for America exasperates him.

If something exacerbates a situation or a problem, it makes it worse. It’s a rather formal word.

e.g. rising inflation was exacerbated by the collapse of oil prices;

At least the government is trying to find an actual solution, rather than exacerbating the problem.

Recently, I’ve noticed quite a few examples of exasperate being used instead of the collocationally more standard exacerbate.

More than half of households living in council or housing association homes…live in one that is not at all, or not very suitable. The Bedroom Tax has exasperated this problem—Big Issue, No. 1018, December 2014.

Given the history of exasperate, and its multiple meanings other than the most common one of “to annoy”, it might, arguably, be difficult to maintain that it is wrong in that context.

This is an updated version of the page with which I first introduced this series of 30 easily confused words.

Filed under: Business Writing Skills, Confusable Words, Help for writers & editors Tagged: 30 easily confused words

September 10, 2016

Spanish colour words: meaning and grammar (2/4) “Red and yellow and pink and green…”

This it the second part of an overview of basic colour words in Spanish, illustrating what they mean, their grammar, and how they relate — or don’t — to English.

celeste. “sky-blue, pale blue”. “Blue eyes” can be ojos celestes or ojos azules, depending, presumably, on the depth and intensity of the blue. In parts of Mexico and Central America, masks (máscaras) play a central part in elaborate dances and rituals, some of which re-enact la conquista, the conquest by Spain of those countries. The masks for the conquistadores often have piercing blue eyes and blond (rubio) hair and beards, as in the image above. Those features hardly match the northern European stereotype of a Spaniard, but the original inhabitants (habitantes) were clearly struck by the relative lightness of the Spaniards’ complexion (la tez) and hair (pelo) compared to their own.

Azul and celeste don’t seem to be rigidly demarcated. For example, the blue of the Argentine flag is often referred to as azul celeste, which, if translated literally – “sky-blue blue” – sounds like what linguists call a tautology, or saying the same thing twice. It puts me in mind of that delightful phrase sky-blue pink to describe a non-existent or fanciful colour; I first heard it from my parents as a child, and it is the kind of paradox or linguistic riddle that children tend to find fascinating.

La bandera argentina.

There is a Spanish proverb or saying (un refrán) based on celeste: El que quiera azul celeste, que le cueste. Literally, “Whoever wants sky-blue, let it cost him”, meaning that it takes hard work to achieve your ambitions.1

If you want a mental link with English, think celestial meaning “relating to the sky or heavens”. Both the English and Spanish words derive ultimately from the Latin word for “heaven”, caelum.

violeta. My route home from school used to take me past a confectioner’s, the window of which often enticed me in, with its elegantly tiered displays of delicately perfumed violet creams, their crystallized flowers sitting voluptuously atop a seductive chocolate crescent.

My mistake: that’s purple, not violet, prose. Which illustrates the fact that I’m personally somewhat hazy about the boundaries of this colour, yet sceptical about some of the online illustrations for it: they seem far too garish and too close to fuchsia (fucsia) to resemble even remotely the colour of the sweets or the flowers. “Roses are red and violets are blue”, after all.

I digress.

Spanish speakers (hispanohablantes) may not agree (estar de acuerdo) on what they classify as violeta. Linguistically, however, they agree that slapping on a la violeta after a word that describes someone’s views or profession is a bit of a put-down: un socialista a la violeta is a “would-be“, “pseudo-” or even “armchair socialist.”

Like naranja, mentioned in an earlier blog, violeta never changes to match the noun it goes with.

marrón. “brown”. Grammatically, marrón is a bit odd: unlike other adjectives ending in -ón, such as mandón/-ona (“bossy”), it has no feminine form, but it does have the plural marrones (notice how the written accent falls off in the plural).

Rather more Spaniards have ojos marrones than have ojos azules, and Northern Europeans would probably stereotype all Spaniards as having ojos marrones. It seems, however, that in fact more than half the population (más de la mitad de la población) have eyes in the spectrum verde–avellana (“green-hazel”).

In Spain, marrón as a noun means a difficult or embarrassing situation that you put yourself in or that someone else puts you in.

¡Vaya marrón en que me ha metido mi prima! “What a fix my cousin has got me into!”

Lush castañas glaseadas topped with what looks like a violeta glaseada.

Like English maroon, marrón comes from the French word for “chestnut”, as in those moreish marrons glacés (castañas glaseadas) that are popular at Christmas. But linguistic history has determined that the two words denote different colours.

Autotest

For which colour adjectives from this and the previous blog are these the anagrams? (The forms shown might be singular/plural, masculine/feminine.)

luesaz

deerv

smoalrali

osajr

aaajrnn

nmraór

teviola

1El que quiera azul celeste, que le cueste. Both quiera and cueste are subjunctive verb forms (from querer and costar). It is standard to use such forms after words or phrases indicating “indefiniteness”, such as el que (“Whoever”, literally “the one who”), which is why it is quiera. The form cueste is subjunctive because it is effectively part of an order, preceded by the conjunction que.

Filed under: Learning Spanish

Spanish colour words: meaning and grammar (2/3) “Red and yellow and pink and green…”

This it the second part of an overview of basic colour words in Spanish, illustrating what they mean, their grammar, and how they relate — or don’t — to English.

celeste. “sky-blue, pale blue”. “Blue eyes” can be ojos celestes or ojos azules, depending, presumably, on the depth and intensity of the blue. In parts of Mexico and Central America, masks (máscaras) play a central part in elaborate dances and rituals, some of which re-enact la conquista, the conquest by Spain of those countries. The masks for the conquistadores often have piercing blue eyes and blond (rubio) hair and beards, as in the image above. Those features hardly match the northern European stereotype of a Spaniard, but the original inhabitants (habitantes) were clearly struck by the relative lightness of the Spaniards’ complexion (la tez) and hair (pelo) compared to their own.

Azul and celeste don’t seem to be rigidly demarcated. For example, the blue of the Argentine flag is often referred to as azul celeste, which, if translated literally – “sky-blue blue” – sounds like what linguists call a tautology, or saying the same thing twice. It puts me in mind of that delightful phrase sky-blue pink to describe a non-existent or fanciful colour; I first heard it from my parents as a child, and it is the kind of paradox or linguistic riddle that children tend to find fascinating.

La bandera argentina.

There is a Spanish proverb or saying (un refrán) based on celeste: El que quiera azul celeste, que le cueste. Literally, “Whoever wants sky-blue, let it cost him”, meaning that it takes hard work to achieve your ambitions.1

If you want a mental link with English, think celestial meaning “relating to the sky or heavens”. Both the English and Spanish words derive ultimately from the Latin word for “heaven”, caelum.

violeta. My route home from school used to take me past a confectioner’s, the window of which often enticed me in, with its elegantly tiered displays of delicately perfumed violet creams, their crystallized flowers sitting voluptuously atop a seductive chocolate crescent.

My mistake: that’s purple, not violet, prose. Which illustrates the fact that I’m personally somewhat hazy about the boundaries of this colour, yet sceptical about some of the online illustrations for it: they seem far too garish and too close to fuchsia (fucsia) to resemble even remotely the colour of the sweets or the flowers. “Roses are red and violets are blue”, after all.

I digress.

Spanish speakers (hispanohablantes) may not agree (estar de acuerdo) on what they classify as violeta. Linguistically, however, they agree that slapping on a la violeta after a word that describes someone’s views or profession is a bit of a put-down: un socialista a la violeta is a “would-be“, “pseudo-” or even “armchair socialist.”

Like naranja, mentioned in an earlier blog, violeta never changes to match the noun it goes with.

marrón. “brown”. Grammatically, marrón is a bit odd: unlike other adjectives ending in -ón, such as mandón/-ona (“bossy”), it has no feminine form, but it does have the plural marrones (notice how the written accent falls off in the plural).

Rather more Spaniards have ojos marrones than have ojos azules, and Northern Europeans would probably stereotype all Spaniards as having ojos marrones. It seems, however, that in fact more than half the population (más de la mitad de la población) have eyes in the spectrum verde–avellana (“green-hazel”).

In Spain, marrón as a noun means a difficult or embarrassing situation that you put yourself in or that someone else puts you in.

¡Vaya marrón en que me ha metido mi prima! “What a fix my cousin has got me into!”

Lush castañas glaseadas topped with what looks like a violeta glaseada.

Like English maroon, marrón comes from the French word for “chestnut”, as in those moreish marrons glacés (castañas glaseadas) that are popular at Christmas. But linguistic history has determined that the two words denote different colours.

Autotest

For which colour adjectives from this and the previous blog are these the anagrams? (The forms shown might be singular/plural, masculine/feminine.)

luesaz

deerv

smoalrali

osajr

aaajrnn

nmraór

teviola

1El que quiera azul celeste, que le cueste. Both quiera and cueste are subjunctive verb forms (from querer and costar). It is standard to use such forms after words or phrases indicating “indefiniteness”, such as el que (“Whoever”, literally “the one who”), which is why it is quiera. The form cueste is subjunctive because it is effectively part of an order, preceded by the conjunction que.

Filed under: Learning Spanish

September 6, 2016

“Red and yellow and pink and green…” Spanish colour words, meaning & grammar (1/4)

An overview of some basic colour words in Spanish, showing what they mean and how they work.

(Skip to after the first picture, if you’re in a hurry. If you’re into “slow reading”, please read on…)

The last Plantagenet English monarch, Richard III, suffered multiple indignities after being slain at the Battle of Bosworth: stripped of its armour, his naked body (cuerpo desnudo) was slung unceremoniously across the back of a horse, and then some peasant stabbed him in the bum (culo) with a dagger (un puñal) as a final insult. (The Age of Chivalry, ¡Un jamón!)

Worse still, when they got him to Leicester, he was buried in an anonymous car park, before being cartoon-villained by Shakespeare, who at least spared him the indignity of mentioning his rather downmarket and very unregal municipal last resting place.

Pedro Pablo Rubens, Paisaje con arco iris (h. 1636, Wallace Collection, Londres).

However, Ricardo found posthumous redemption of a sort by being immortalized centuries later (siglos después) in a schoolboy mnemonic for the colours of the rainbow (el arco iris):

Richard

Of

York

Gave

Battle

In

Vain

red

orange

yellow

green

blue

indigo

violet

There is no analogous mnemonic in Spanish, and in any case “indigo” is not a colour (un color) much in use. But the corresponding colours that are more or less useful go like this:

red

orange

yellow

green

blue

violet

rojo

naranja

amarillo

verde

azul

violeta

It’s an obvious fact of language that colours do not necessarily have the same symbolic meaning (significado) or connotations in every language: for English speakers red means danger (peligro), for Chinese speakers it means good fortune (la suerte). What follows highlights some of the similarities and differences between Spanish and English when it comes to the most common colour words. And there’s an ever so easy self-test at the end.

Rojo shares the consonant r and many associations with English red. For example,  someone with pelo rojo has red hair, and the two words combine to make un pelirrojo / una pelirroja, “a redhead.” If you’re finding it hard to visualize a pelirrojo, think of that famous royal bachelor (soltero) Prince Harry (el príncipe Henrique).

someone with pelo rojo has red hair, and the two words combine to make un pelirrojo / una pelirroja, “a redhead.” If you’re finding it hard to visualize a pelirrojo, think of that famous royal bachelor (soltero) Prince Harry (el príncipe Henrique).

During the Cold War (la Guerra Fría), Soviets, communists, and sympathizers might be referred to colloquially as rojos, which was also the term Francoists used during the Civil War to demonize Republicans.

Someone who is extremely embarrassed turns red “as a tomato”, not a beetroot:

Basta1 mirarle2 para que3 se le ponga4 la cara5 como6 un tomate7. “You’ve only got to look at him and he goes as red as a beetroot”.1

And beware: for wine you use a different word: red wine is vino tinto.

Naranja. As in English, you use the same word for the citrus fruit orange and the colour, but a fruit is una naranja whereas the colour is el naranja, because all colours are masculine. Both the English and Spanish words ultimately come from Arabic nāranj , but the n at the beginning dropped off somewhere on the way to English, while Spanish kept it.

Certain colours adjectives like naranja never change to match the noun they go with: un pantalón naranja, una blusa naranja, dos blusas naranja. Such “invariable” adjectives can be used on their own, but are just as often preceded by color or de color: una camisa color naranja/beige, una camisa de color naranja/beige.

Amarillo. Unlike the previous two, there seems nothing to connect this word and English yellow. Perhaps the double ll in both might help you to make the connection. In Spanish, you talk about the la prensa amarilla, literally the “yellow press”, meaning “the gutter press.” Amarillo also has a negative meaning – just like English yellow = “cowardly” – when talking about “yellow unions” that represent employers’ rather than workers’ interests, los sindicatos amarillos.

To say the word, put the song “Is this the Way to Amarillo” right out of your mind. You pronounce that double ll as a sort of y, to give a-ma-ree-yo.

Verde. Apart from being the title of a famous Lorca poem, “Verde que te quiero verde”, startlingly, for English speakers, you use the word for green in the phrase un viejo verde, “a dirty old man” and un chiste verde, “a dirty joke”. The association of verde / green with ecology is the same in both languages, as is the link with jealousy: estar verde de invidia “to be green with envy”. If you want a connection with English, think verdant.

Verde ends with an –e. Adjectives ending in any vowel other than –o have no feminine form, but they do have a plural, i.e. verdes. There is a famous flamenco song or copla about a woman who spends a night of passion with a man with green eyes:

Ojos verdes, verdes como la albahaca. Green eyes, green like basil.

Verdes como el trigo verde Green like unripe corn

y el verde, verde limón. And green, green lemons.

Ojos verdes, verdes, con brillo de faca Green green eyes, that gleam like a knife

que estan clavaito en mi corazón. And have stuck in my heart.

And here’s the renowned flamenco singer the late Rocío Jurado giving a wonderfully over-the-top theatrical (teatral) rendition. Not for nothing was she nicknamed La más grande (“The Greatest”).

El Greco, La Trinidad (detalle), 1577-1579, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid. I don’t think you can get much more “azul” than that.

Azul. Just as in English, aristocrats are supposed to have blue blood: veinte familias de sangre azul “twenty aristocratic families” (literally “families of blue blood”). Presumably in the same vein, someone’s príncipe azul is their “Prince Charming” or “knight in shining armour,” or even “Mr Right.”

As a cynic blogged: Las mujeres se pasan la mitad de su vida buscando a su príncipe azul, para terminar casándose con un amable fontanero.

“Women spend half their lives looking for Mr Right only to end up marrying a nice plumber.”

Just like verde, azul is one of those unreconstructed chauvinist adjectives that have no feminine, but do change for the plural, e.g. Scandinavians stereotypically have ojos azules.

This rule about adjectives not having a feminine but having a plural applies to almost all adjectives ending, like azul, in a consonant, e.g. un chico/una chica joven, un trabajo/una pregunta fácil, “a young boy/girl”, “an easy job/question”.

1The word-for-word translation is: “It is enough1 to look at him2 so that3 it to him becomes4 the face5 like6 a tomato7”.

Autotest

1. Match the Spanish phrase to the English.

a. The Red Planet

los Verdes

b. A red alert

de sangre azul

c. blue-blooded

el Planeta Rojo

d. an orange shirt

El Ángel Azul

e. the Greens

una camisa naranja

f. The Blue Angel

una alerta roja

2. ¿Verdadero o falso?

a. The English word orange is from Dutch.

b. All adjectives in Spanish change to match the noun they go with.

c. “Red wine” is vino tinto.

d. “Amarillo” as sung in “Is this the way to Amarillo” is the correct Spanish pronunciation.

e. All Spanish colour words are masculine.

f. The feminine of verde is verda.

Filed under: Learning Spanish

“Red and yellow and pink and green…” Spanish colour words, meaning & grammar (1/3)

An overview of some basic colour words in Spanish, showing what they mean and how they work.

(Skip to after the first picture, if you’re in a hurry. If you’re into “slow reading”, please read on…)

The last Plantagenet English monarch, Richard III, suffered multiple indignities after being slain at the Battle of Bosworth: stripped of its armour, his naked body (cuerpo desnudo) was slung unceremoniously across the back of a horse, and then some peasant stabbed him in the bum (culo) with a dagger (un puñal) as a final insult. (The Age of Chivalry, ¡Un jamón!)

Worse still, when they got him to Leicester, he was buried in an anonymous car park, before being cartoon-villained by Shakespeare, who at least spared him the indignity of mentioning his rather downmarket and very unregal municipal last resting place.

Pedro Pablo Rubens, Paisaje con arco iris (h. 1636, Wallace Collection, Londres).

However, Ricardo found posthumous redemption of a sort by being immortalized centuries later (siglos después) in a schoolboy mnemonic for the colours of the rainbow (el arco iris):

Richard

Of

York

Gave

Battle

In

Vain

red

orange

yellow

green

blue

indigo

violet

There is no analogous mnemonic in Spanish, and in any case “indigo” is not a colour (un color) much in use. But the corresponding colours that are more or less useful go like this:

red

orange

yellow

green

blue

violet

rojo

naranja

amarillo

verde

azul

violeta

It’s an obvious fact of language that colours do not necessarily have the same symbolic meaning (significado) or connotations in every language: for English speakers red means danger (peligro), for Chinese speakers it means good fortune (la suerte). What follows highlights some of the similarities and differences between Spanish and English when it comes to the most common colour words. And there’s an ever so easy self-test at the end.

Rojo shares the consonant r and many associations with English red. For example,  someone with pelo rojo has red hair, and the two words combine to make un pelirrojo / una pelirroja, “a redhead.” If you’re finding it hard to visualize a pelirrojo, think of that famous royal bachelor (soltero) Prince Harry (el príncipe Henrique).

someone with pelo rojo has red hair, and the two words combine to make un pelirrojo / una pelirroja, “a redhead.” If you’re finding it hard to visualize a pelirrojo, think of that famous royal bachelor (soltero) Prince Harry (el príncipe Henrique).

During the Cold War (la Guerra Fría), Soviets, communists, and sympathizers might be referred to colloquially as rojos, which was also the term Francoists used during the Civil War to demonize Republicans.

Someone who is extremely embarrassed turns red “as a tomato”, not a beetroot:

Basta1 mirarle2 para que3 se le ponga4 la cara5 como6 un tomate7. “You’ve only got to look at him and he goes as red as a beetroot”.1

And beware: for wine you use a different word: red wine is vino tinto.

Naranja. As in English, you use the same word for the citrus fruit orange and the colour, but a fruit is una naranja whereas the colour is el naranja, because all colours are masculine. Both the English and Spanish words ultimately come from Arabic nāranj , but the n at the beginning dropped off somewhere on the way to English, while Spanish kept it.

Certain colours adjectives like naranja never change to match the noun they go with: un pantalón naranja, una blusa naranja, dos blusas naranja. Such “invariable” adjectives can be used on their own, but are just as often preceded by color or de color: una camisa color naranja/beige, una camisa de color naranja/beige.

Amarillo. Unlike the previous two, there seems nothing to connect this word and English yellow. Perhaps the double ll in both might help you to make the connection. In Spanish, you talk about the la prensa amarilla, literally the “yellow press”, meaning “the gutter press.” Amarillo also has a negative meaning – just like English yellow = “cowardly” – when talking about “yellow unions” that represent employers’ rather than workers’ interests, los sindicatos amarillos.

To say the word, put the song “Is this the Way to Amarillo” right out of your mind. You pronounce that double ll as a sort of y, to give a-ma-ree-yo.

Verde. Apart from being the title of a famous Lorca poem, “Verde que te quiero verde”, startlingly, for English speakers, you use the word for green in the phrase un viejo verde, “a dirty old man” and un chiste verde, “a dirty joke”. The association of verde / green with ecology is the same in both languages, as is the link with jealousy: estar verde de invidia “to be green with envy”. If you want a connection with English, think verdant.

Verde ends with an –e. Adjectives ending in any vowel other than –o have no feminine form, but they do have a plural, i.e. verdes. There is a famous flamenco song or copla about a woman who spends a night of passion with a man with green eyes:

Ojos verdes, verdes como la albahaca. Green eyes, green like basil.

Verdes como el trigo verde Green like unripe corn

y el verde, verde limón. And green, green lemons.

Ojos verdes, verdes, con brillo de faca Green green eyes, that gleam like a knife

que estan clavaito en mi corazón. And have stuck in my heart.

And here’s the renowned flamenco singer the late Rocío Jurado giving a wonderfully over-the-top theatrical (teatral) rendition. Not for nothing was she nicknamed La más grande (“The Greatest”).

El Greco, La Trinidad (detalle), 1577-1579, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid. I don’t think you can get much more “azul” than that.

Azul. Just as in English, aristocrats are supposed to have blue blood: veinte familias de sangre azul “twenty aristocratic families” (literally “families of blue blood”). Presumably in the same vein, someone’s príncipe azul is their “Prince Charming” or “knight in shining armour,” or even “Mr Right.”

As a cynic blogged: Las mujeres se pasan la mitad de su vida buscando a su príncipe azul, para terminar casándose con un amable fontanero.

“Women spend half their lives looking for Mr Right only to end up marrying a nice plumber.”

Just like verde, azul is one of those unreconstructed chauvinist adjectives that have no feminine, but do change for the plural, e.g. Scandinavians stereotypically have ojos azules.

This rule about adjectives not having a feminine but having a plural applies to almost all adjectives ending, like azul, in a consonant, e.g. un chico/una chica joven, un trabajo/una pregunta fácil, “a young boy/girl”, “an easy job/question”.

1The word-for-word translation is: “It is enough1 to look at him2 so that3 it to him becomes4 the face5 like6 a tomato7”.

Autotest

1. Match the Spanish phrase to the English.

a. The Red Planet

los Verdes

b. A red alert

de sangre azul

c. blue-blooded

el Planeta Rojo

d. an orange shirt

El Ángel Azul

e. the Greens

una camisa naranja

f. The Blue Angel

una alerta roja

2. ¿Verdadero o falso?

a. The English word orange is from Dutch.

b. All adjectives in Spanish change to match the noun they go with.

c. “Red wine” is vino tinto.

d. “Amarillo” as sung in “Is this the way to Amarillo” is the correct Spanish pronunciation.

e. All Spanish colour words are masculine.

f. The feminine of verde is verda.

Filed under: Learning Spanish

“Red and yellow and pink and green…” Spanish colour words, meaning & grammar (1/1)

An overview of some basic colour words in Spanish, showing what they mean and how they work.

(Skip to after the first picture, if you’re in a hurry. If you’re into “slow reading”, please read on…)

The last Plantagenet English monarch, Richard III, suffered multiple indignities after being slain at the Battle of Bosworth: stripped of its armour, his naked body (cuerpo desnudo) was slung unceremoniously across the back of a horse, and then some peasant stabbed him in the bum (culo) with a dagger (un puñal) as a final insult. (The Age of Chivalry, ¡Un jamón!)

Worse still, when they got him to Leicester, he was buried in an anonymous car park, before being cartoon-villained by Shakespeare, who at least spared him the indignity of mentioning his rather downmarket and very unregal municipal last resting place.

Pedro Pablo Rubens, Paisaje con arco iris (h. 1636, Wallace Collection, Londres).

However, Ricardo found posthumous redemption of a sort by being immortalized centuries later (siglos después) in a schoolboy mnemonic for the colours of the rainbow (el arco iris):

Richard

Of

York

Gave

Battle

In

Vain

red

orange

yellow

green

blue

indigo

violet

There is no analogous mnemonic in Spanish, and in any case “indigo” is not a colour (un color) much in use. But the corresponding colours that are more or less useful go like this:

red

orange

yellow

green

blue

violet

rojo

naranja

amarillo

verde

azul

violeta

It’s an obvious fact of language that colours do not necessarily have the same symbolic meaning (significado) or connotations in every language: for English speakers red means danger (peligro), for Chinese speakers it means good fortune (la suerte). What follows highlights some of the similarities and differences between Spanish and English when it comes to the most common colour words. And there’s an ever s0 easy self-test at the end.

Rojo shares the consonant r and many associations with English red. For example,  someone with pelo rojo has red hair, and the two words combine to make un pelirrojo / una pelirroja, “a redhead.” If you’re finding it hard to visualize a pelirrojo, think of that famous royal bachelor (soltero) Prince Harry (el príncipe Henrique).

someone with pelo rojo has red hair, and the two words combine to make un pelirrojo / una pelirroja, “a redhead.” If you’re finding it hard to visualize a pelirrojo, think of that famous royal bachelor (soltero) Prince Harry (el príncipe Henrique).

During the Cold War (la Guerra Fría), Soviets, communists, and sympathizers might be referred to colloquially as rojos, which was also the term Francoists used during the Civil War to demonize Republicans.

Someone who is extremely embarrassed turns red “as a tomato”, not a beetroot:

Basta1 mirarle2 para que3 se le ponga4 la cara5 como6 un tomate7. “You’ve only got to look at him and he goes as red as a beetroot”.1

And beware: for wine you use a different word: red wine is vino tinto.

Naranja. As in English, you use the same word for the citrus fruit orange and the colour, but a fruit is una naranja whereas the colour is el naranja, because all colours are masculine. Also, adjectives like naranja that don’t end in -o never change: un pantalón naranja, una blusa naranja, dos blusas naranja. Both the English and Spanish words ultimately come from Arabic nāranj , but the n at the beginning dropped off somewhere on the way to English, while Spanish kept it.

Amarillo. Unlike the previous two, there seems nothing to connect this word and English yellow. Perhaps the double ll in both might help you to make the connection. In Spanish, you talk about the la prensa amarilla, literally the “yellow press”, meaning “the gutter press.” Amarillo also has a negative meaning – just like English yellow = “cowardly” – when talking about “yellow unions” that represent employers’ rather than workers’ interests, los sindicatos amarillos.

To say the word, put the song “Is this the Way to Amarillo” right out of your mind. You pronounce that double ll as a sort of y, to give a-ma-ree-yo.

Verde. Apart from being the title of a famous Lorca poem, “Verde que te quiero verde”, startlingly, for English speakers, you use the word for green in the phrase un viejo verde, “a dirty old man” and un chiste verde, “a dirty joke”. The association of verde / green with ecology is the same in both languages, as is the link with jealousy: estar verde de invidia “to be green with envy”. If you want a connection with English, think verdant.

El Greco, La Trinidad (detalle), 1577-1579, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid. I don’t think you can get much more “azul” than that.

Azul. Just as in English, aristocrats are supposed to have blue blood: veinte familias de sangre azul “twenty aristocratic families” (literally “families of blue blood”). Presumably in the same vein, someone’s príncipe azul is their “Prince Charming” or “knight in shining armour,” or even “Mr Right.”

As a cynic blogged: Las mujeres se pasan la mitad de su vida buscando a su príncipe azul, para terminar casándose con un amable fontanero.

Women spend half their lives looking for Mr Right only to end up marrying a nice plumber.

1The word-for-word translation is: “It is enough1 to look at him2 so that3 it to him becomes4 the face5 like6 a tomato7”.

Autotest

1. Match the Spanish phrase to the English.

a. The Red Planet

los Verdes

b. A red alert

de sangre azul

c. blue-blooded

el Planeta Rojo

d. an orange shirt

El Ángel Azul

e. the Greens

una camisa naranja

f. The Blue Angel

una alerta roja

2. ¿Verdadero o falso?

a. The English word orange is from Dutch.

b. All adjectives in Spanish change to match the noun they go with.

c. “Red wine” is vino tinto.

d. “Amarillo” as sung in “Is this the way to Amarillo” is the correct Spanish pronunciation.

e. All Spanish colour words are masculine.

Filed under: Learning Spanish

September 3, 2016

Mean while or meanwhile? In the mean while or in the meanwhile? One word or two?

Short answer: one word. To write two words will nowadays be considered a mistake. But it wasn’t always so…

(I think that should be “Meanwhile, in Scotland”, don’t you?)

Rules iz rules…but rules can change.

To write several analogous pairs (a while, any more, etc.) as one word or two is a matter of convention, and conventions can, and do, change over time.1

I was forcefully reminded of this while reading Matthew Lewis’s The Monk (1796), a Gothic classic that keeps making me visualize a sort of Ken Russell – if not Hammer horror – film before its time, or “avant la lettre”, if I wish to be flowery, which I often do.

The narrator falls into the hands of murderous outlaws who want to drug him – and a baroness who has also fallen into their clutches – by giving them a spiked drink (or a sleeping draught, in more trad language).

“In the mean while our host [Baptiste, a bandit] had drawn the cork, and, filling two of the goblets, offered them to the lady and myself. She at first made some objections, but the instances of Baptiste were so urgent, that she was obliged to comply. Fearing to excite suspicion, I hesitated not to take the goblet presented to me. By its smell and colour, I guessed it to be champagne; but some grains of powder floating upon the top convinced me that it was not unadulterated.”

(Fret not: the hero does manage to avoid drinking the potion, and then feigns sleep. Tales of his derring-do fill at least another hundred pages.)

Note that “In the mean while” at the start of the extract.

Some history…

As the revised (2001) OED entry notes: “The one-word form (first found in the 16th cent.) has become steadily more frequent since the early 19th cent., and has been the standard form since the end of the 19th cent.”

Modern meanwhile has simply obliterated the space that manifests its etymology. It is, quite simply, a combination of “mean” the adjective and “while” the noun. That adjectival meaning is defined by the OED as “Intermediate in time; coming or occurring between two points of time or two events” and gave rise to the now obsolete adverbs the mean season and mean space, both meaning, um…, “meanwhile.”

Mean[ ]while itself, is first recorded as a noun from some time before 1375:

Boþe partiȝes…made hem alle merie in þe mene while.

(Both parties…all made merry in the meanwhile.)

William of Palerne.

and as an adverb in the first English-Latin dictionary, the Promptorium Parvulorum (“Storehouse for Children” or “Little Egbert’s Crib Sheet”) of 1440:

Mene whyle, interim.

Annoyingly, the OED doesn’t present a single-word example from the sixteenth century: its first “solid” example is:

Upon this subject I will in my next Number make an appeal… In the meanwhile let me pride myself a little on the circumstance [etc.].

Cobbett’s Weekly Polit. Reg. 33 101, 1818.

In the Bard’s work too…

Shakespeare used the word(s), e.g.

Let the lawes of Rome determine all,

Meane while am I possest of that is mine.

Titus Andronicus i. i. 405, 1594.

but much more often he used (in the) meantime, as when Portia says:

For never shall you lie by Portia’s side

With an unquiet soul. You shall have gold

To pay the petty debt twenty times over:

When it is paid, bring your true friend along.

My maid Nerissa and myself meantime

Will live as maids and widows. Come, away!

For you shall hence upon your wedding-day:

Merchant of Venice, iii. ii. 318 ff., 1600.

Modern usage follows Shakespeare. In the GloWbE corpus (Global Web-based English), in the meantime is 20 times more frequent than in the meanwhile.

Two poetic “meanwhiles”

And, as I was writing this, the last words of Auden’s Friday’s Child, in memory of the German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, floated into my head:

Meanwhile, a silence on the cross,

As dead as we shall ever be,

Speaks of some total gain or loss,

And you and I are free

To guess from the insulted face

Just what Appearances He saves

By suffering in a public place

A death reserved for slaves.

And then a “virtual” colleague made this comment, which I had to add:

“One of my favourite lines from the great Flann O’Brien, where the narrator in The Third Policeman describes his mother: ‘She was always making tea to pass the time, and singing snatches of old songs to pass the meantime.'”

1Witness the kerfuffle* when, in 2013, Associated Press (AP) changed its ruling about “under way” being two words in most contexts to “underway” in all contexts. Editors can be an OCDish lot – after all, part of their job consists in weeding out and correcting things that most people don’t even notice – and one such editor tweeted “I can’t be the only one who is outraged that AP is changing its style from ‘under way’ to ‘underway,’ am I?”

Copy-editing, it could be argued, is a profession whose motto invalidates the old Latin motto de minimis non est curandum (“Don’t sweat the small stuff” or, literally, “It is not to be worried about trivia”).

Whether that be true or not, conventions iz conventions, and the fact that most people abide by them makes them worth sticking to.

* An originally Scottish word, spelt curfuffle.

Filed under: One word or two?, Spelling Tagged: Shakespeare, W.H. Auden

August 26, 2016

“Keep/stay abreast of” or “keep/stay abreast with”? (2/2)

Previously, I talked about how editing papers by non-mother tongue speakers can sometimes severely test my native speaker intuitions about English. I mentioned slightly atypical word choice as one recurrent issue, and odd collocation as another.

Quick takeaways

There is considerable variation in global English between abreast of /with. With seems to be commoner in countries where English, while an official or second language, is less used than elsewhere.

Analogy and history suggest that it is impossible to say that one version is “correct ” in all circumstances.

Use of one or the other form seems to depend not only on where in the English-speaking world you are, but also on the register. In some academic writing, “with” is standard.

Abreast with?!?!?!

I came across abreast with in an academic paper and it caused me some head-scratching.

The complete phrase was: “He distinguished five dimensions related to Organizational Citizenship Behaviour: civic virtue (keeping abreast with important organizational affairs)…”

“(Shome mishtake, shurely? Ed),” thought I to myself, “abreast of is canonical and abreast with a mistake”. On the other hand, I did not amend it and decided to check.

Analogy is such a powerful factor in language: many synonyms of abreast in this meaning take with as their preposition. The Oxford Online Dictionary offers ten synonyms, of which eight take with, e.g. up to date with.

It seemed clear to me that non-mother tongue speakers would find it logical to use with, as the standard linking preposition. Moreover, they would probably have come across some of those synonyms rather more often than the less frequent abreast of , with its seemingly anomalous preposition.

The usage guides I normally use were of no help, and there was little discussion online, so I consulted corpora.

The first was the Oxford English Corpus.

Shock! Horror!

In the February 2014 release, abreast of appeared only seven times, while abreast with came up well over 100 times, e.g.

She said because technology keeps changing, her company would not want to remain behind but to keep updating their network so as to keep abreast with the latest communication technology.

Reviewing those examples raised in me the suspicion that the figure was high because of regional variation combined with journalistic preference. First, abreast with occurs with far greater than expected frequency in South African, Indian and Caribbean sources; second, in each of those segments its use is confined to a handful of newspapers, e.g. The Times of Zambia, The Hindu, etc.

But my surprise was even greater when I checked in the Oxford Corpus of Academic English, journals, of June 2015: stay / keep abreast with = 48; abreast of = 2.

Does the choice of preposition depend on register and domain then, as well as region?

It would seem so.

It also depends on where in the English-speaking world you are from

I checked in four other corpora: The Corpus of Historical American, The Corpus of Contemporary American, the NOW Corpus, and the Corpus of Global Web-based English. To simplify matters, I searched for the lemmas of KEEP and STAY only. The figures are these:

CORPUS (size)

dates

keep abreast of

keep abreast with

stay abreast of

stay abreast with

COHA (400 mill.)

1810s–2000s

202 (93.5%)

14 (6.5%)

15 (100%)

0

COCA (520 mill.)

1990–2015

195 (97.5%)

5 (2.5%)

86 (96.6%)

3 (3.4%)

NOW (2.8 bill.) 20 countries

2010–yesterday

1252 (83.3%)

251 (16.7%)

488 (92.6%)

39 (7.4%)

GloWbE (1.9 bill.) 20 countries

2012–2013

969 (83.6%)

188 (16.4%)

333 (92%)

29 (8%)

What strikes me is the difference between keep abreast of in data from a single country (COHA, COCA) and from 20 countries.

Moreover, doing a less focused search for abreast + 1 – which brings in verb variants such as REMAIN, BE, MAINTAIN, etc. – reveals discrepancies between different varieties of English.

For example, while the percentage for of in US English is 93.7%, in Indian English it is 70.2%, in Malaysian English 58.4%, and in Ghanaian English a mere 33.8%.

Grouping the 20 varieties of English in GloWbE gives this intriguing result for of:

Grouping the 20 varieties of English in GloWbE gives this intriguing result for of:

(In descending order within each grouping)

100–90%: Canada, US, Ireland, Australia, Hong Kong, Jamaica, GB

80–90%: NZ, Zambia, Bangladesh, Singapore, Sri Lanka

70–80%: Tanzania, Pakistan, Philippines, Nigeria, Kenya, India

60–70%

50–60% Malaysia

40–50%

30–40% Ghana

Dictionaries

Of the eight dictionaries I consulted (both native-speaker and learners dictionaries), only the Oxford Advanced Learners (OALD) had an example showing with:”It’s important to keep abreast with the latest legislation.” In addition, the Collins English Dictionary, while containing no examples at all, did mark the relevant meaning as (followed by of or with). Seven dictionaries had examples also for the literal meaning – to be alongside or level with someone or something – all exclusively with of.

The long view: historically speaking

A search in the revised (2009) OED, however, reveals several interesting things. For the physical meaning:

it gives the phrase as abreast of (also with );

the first citation for that meaning (1635) has with ;

of 11 citations (dated 1635–1994), four have with.

The metaphorical meaning is category b) of the phrase as laid out above, with the additional note “Freq[uently]. to keep abreast of:

of 11 citations for that meaning (spanning 1644–2005), seven are with;

they range from 1644 through the 19th and 20th centuries

(There are choice examples at the end, for the really keen.)

Conclusion? And the moral is…?

For this editor, the moral of the story is: don’t jump to conclusions.

Given that the authors of the article which was my starting point were from the Gulf University of Science and Technology in Kuwait, and that the medium was an academic article, leaving with seems the correct decision to me.

Second, it shows that even something as apparently simple as a compound preposition admits of perfectly legitimate variation. It may not be part of my (or your) idiolect, but that doesn’t matter.

Third, as is not unusual, the alternatives are not a “modern invention”, but instead have a long history.

To insist that the version one prefers is the only correct one, in the face of global variation, is to bury one’s head in the sand and be a linguistic martinet.

And last of all, at the risk of stating the obvious, any editor working on international material needs to be aware that there are variations other than the oft-raised British vs US English.

PS

The interweb being what it is, images for “keeping abreast of ” were as you might imagine. As I like my images, this will have to do instead.

Examples: literal

The three next men behind him, move forwards to the left of each other; untill they ranke even a brest with their file-leader.

W. Barriffe, Military Discipline xxxvii. 104, 1635.

Facing about, he march’d up abreast with her to the sopha.

Sterne, Tristram Shandy IX. xxv. 101, 1767.

He is abreast of the white man, who has paused.

W. Faulkner, As I lay Dying lii. 155, 1930.

metaphorical

Though some conceive him to be as much beneath a Poet, as above a Rhimer, in my opinion his Verses may go abreast with any of that age.

T. Fuller Worthies (1662) Shrop. 9, a1661.

The compromises by which they endeavoured to keep themselves abreast of the current of the day.

Scott Redgauntlet (new ed.) I. p. xxi, 1832.

I had written my diary so far, and simply read it off to them as the best means of letting them get abreast of my own information.

B. Stoker Dracula xx. 274, 1897.

Like so many Italian composers, Verdi regarded himself primarily as a craftsman whose duty it was to keep himself abreast with the times.

Musical Times 71 559/1, 1930.

Filed under: Grammar, Help for writers & editors

“Keep abreast of” or “keep abreast with”? An editor’s dilemma (2/2)

Previously, I talked about how editing papers by non-mother tongue speakers can sometimes severely test my native speaker intuitions about English. I mentioned slightly atypical word choice as one recurrent issue, and odd collocation as another.

Quick carry-oots

(That’s the Scottish for “takeaway”, but it doesn’t seem to work quite so well. This can only be due to machinations by the Westminster elite. I jest, of course.)

There is considerable variation in global English between abreast of /with. With seems to be commoner in countries where English, while an official or second language, is less used than elsewhere.

Analogy and history suggest that it is impossible to say that one version is “correct ” in all circumstances.

Use of one or the other form seems to depend not only on where in the English-speaking world you are, but also on the register. In some academic writing, “with” is standard.

Abreast with?!?!?!

I came across abreast with in an academic paper and it caused me some head-scratching.

The complete phrase was: “He distinguished five dimensions related to Organizational Citizenship Behaviour: civic virtue (keeping abreast with important organizational affairs)…”

“(Shome mishtake, shurely? Ed),” thought I to myself, “abreast of is canonical and abreast with a mistake”. On the other hand, I did not amend it and decided to check.

Analogy is such a powerful factor in language: many synonyms of abreast in this meaning take with as their preposition. The Oxford Online Dictionary offers ten synonyms, of which eight take with, e.g. up to date with.

It seemed clear to me that non-mother tongue speakers would find it logical to use with, as the standard linking preposition. Moreover, they would probably have come across some of those synonyms rather more often than the less frequent abreast of , with its seemingly anomalous preposition.

The usage guides I normally use were of no help, and there was little discussion online, so I consulted corpora.

The first was the Oxford English Corpus.

Shock! Horror!

In the February 2014 release, abreast of appeared only seven times, while abreast with came up well over 100 times, e.g.

She said because technology keeps changing, her company would not want to remain behind but to keep updating their network so as to keep abreast with the latest communication technology.

Reviewing those examples raised in me the suspicion that the figure was high because of regional variation combined with journalistic preference. First, abreast with occurs with far greater than expected frequency in South African, Indian and Caribbean sources; second, in each of those segments its use is confined to a handful of newspapers, e.g. The Times of Zambia, The Hindu, etc.

But my surprise was even greater when I checked in the Oxford Corpus of Academic English, journals, of June 2015: stay / keep abreast with = 48; abreast of = 2.

Does the choice of preposition depend on register and domain then, as well as region?

It would seem so.

It also depends on where in the English-speaking world you are from

I checked in four other corpora: The Corpus of Historical American, The Corpus of Contemporary American, the NOW Corpus, and the Corpus of Global Web-based English. To simplify matters, I searched for the lemmas of KEEP and STAY only. The figures are these:

CORPUS (size)

dates

keep abreast of

keep abreast with

stay abreast of

stay abreast with

COHA (400 mill.)

1810s–2000s

202 (93.5%)

14 (6.5%)

15 (100%)

0

COCA (520 mill.)

1990–2015

195 (97.5%)

5 (2.5%)

86 (96.6%)

3 (3.4%)

NOW (2.8 bill.) 20 countries

2010–yesterday

1252 (83.3%)

251 (16.7%)

488 (92.6%)

39 (7.4%)

GloWbE (1.9 bill.) 20 countries

2012–2013

969 (83.6%)

188 (16.4%)

333 (92%)

29 (8%)

What strikes me is the difference between keep abreast of in data from a single country (COHA, COCA) and from 20 countries.

Moreover, doing a less focused search for abreast + 1 – which brings in verb variants such as REMAIN, BE, MAINTAIN, etc. – reveals discrepancies between different varieties of English.

For example, while the percentage for of in US English is 93.7%, in Indian English it is 70.2%, in Malaysian English 58.4%, and in Ghanaian English a mere 33.8%.

Grouping the 20 varieties of English in GloWbE gives this intriguing result for of:

Grouping the 20 varieties of English in GloWbE gives this intriguing result for of:

(In descending order within each grouping)

100–90%: Canada, US, Ireland, Australia, Hong Kong, Jamaica, GB

80–90%: NZ, Zambia, Bangladesh, Singapore, Sri Lanka

70–80%: Tanzania, Pakistan, Philippines, Nigeria, Kenya, India

60–70%

50–60% Malaysia

40–50%

30–40% Ghana

Dictionaries

Of the eight dictionaries I consulted (both native-speaker and learners dictionaries), only the Oxford Advanced Learners (OALD) had an example showing with:”It’s important to keep abreast with the latest legislation.” In addition, the Collins English Dictionary, while containing no examples at all, did mark the relevant meaning as (followed by of or with). Seven dictionaries had examples also for the literal meaning – to be alongside or level with someone or something – all exclusively with of.

The long view: historically speaking

A search in the revised (2009) OED, however, reveals several interesting things. For the physical meaning:

it gives the phrase as abreast of (also with );

the first citation for that meaning (1635) has with ;

of 11 citations (dated 1635–1994), four have with.

The metaphorical meaning is category b) of the phrase as laid out above, with the additional note “Freq[uently]. to keep abreast of:

of 11 citations for that meaning (spanning 1644–2005), seven are with;

they range from 1644 through the 19th and 20th centuries

(There are choice examples at the end, for the really keen.)

Conclusion? And the moral is…?

For this editor, the moral of the story is: don’t jump to conclusions.

Given that the authors of the article which was my starting point were from the Gulf University of Science and Technology in Kuwait, and that the medium was an academic article, leaving with was the correct decision.

Second, it shows that even something as apparently simple as a compound preposition admits of perfectly legitimate variation. It may not be part of my (or your) idiolect, but that doesn’t matter.

Third, as is not unusual, the alternatives are not a “modern invention”, but instead have a long history.

To insist that the version one prefers is the only correct one, in the face of global variation, is to bury one’s head in the sand and be a linguistic martinet.

And last of all, at the risk of stating the obvious, any editor working on international material needs to be aware that there are variations other than the oft-raised British vs US English.

PS

The interweb being what it is, images for “keeping abreast of ” were as you might imagine. As I like my images, this will have to do instead.

Examples: literal

The three next men behind him, move forwards to the left of each other; untill they ranke even a brest with their file-leader.

W. Barriffe, Military Discipline xxxvii. 104, 1635.

Facing about, he march’d up abreast with her to the sopha.

Sterne, Tristram Shandy IX. xxv. 101, 1767.

He is abreast of the white man, who has paused.

W. Faulkner, As I lay Dying lii. 155, 1930.

metaphorical

Though some conceive him to be as much beneath a Poet, as above a Rhimer, in my opinion his Verses may go abreast with any of that age.

T. Fuller Worthies (1662) Shrop. 9, a1661.

The compromises by which they endeavoured to keep themselves abreast of the current of the day.

Scott Redgauntlet (new ed.) I. p. xxi, 1832.

I had written my diary so far, and simply read it off to them as the best means of letting them get abreast of my own information.

B. Stoker Dracula xx. 274, 1897.

Like so many Italian composers, Verdi regarded himself primarily as a craftsman whose duty it was to keep himself abreast with the times.

Musical Times 71 559/1, 1930

Filed under: Grammar, Help for writers & editors