Jeremy Butterfield's Blog, page 23

August 20, 2016

“Keep/stay abreast of” or “keep/stay abreast with”? (1/2)

For my sins, one of the things I do is “quality-check” the work of other editors. I do this for an organization that pays editors to copy-edit academic papers written by non-native speakers.

(I also copy-edit such papers myself, which is often extremely interesting as it opens up whole new worlds never dreamt of in my philosophy, from Game Theory applied to the Torah to assessing the quality of new housing for flood victims in the Philippines.)

Actually, I say “for my sins”, but mostly it is really rather enjoyable: the editors generally do an excellent job, and I only have to make a minimum of changes.

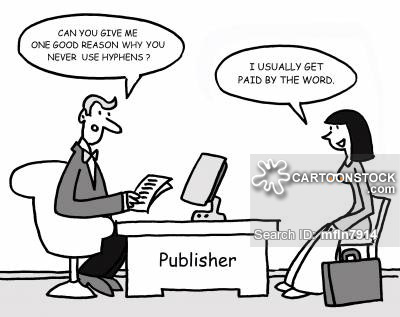

If you take hyphens seriously, you will surely go mad

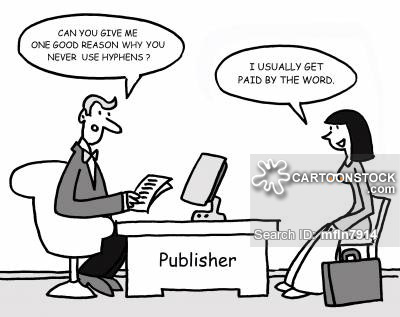

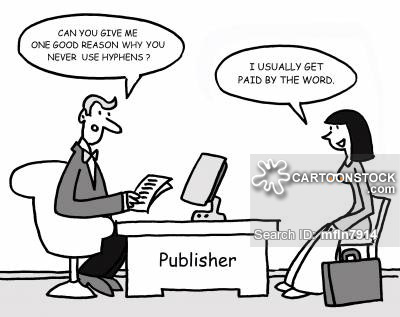

“I get paid by the word.”

That phrase is attributed, I believe, to an OUP editor. In my quality-checking role I have to take them seriously: of my sanity, only my friends and family can give you an unbiased opinion.

Two recurring issues in what I check are hyphenation and defining vs non-defining relative clauses. On the first, editors often leave out essential hyphens, e.g. “low-level” as a compound attributive adjective. With relative clauses, they often leave out the comma before a non-defining clause, an omission which often changes the meaning significantly.

‘I’ll agree to a fifty-fifty split, but I get the hyphen.’

One of the other things that editing papers by non-mother tongue (now, should there be a hyphen between “mother” and “tongue”? Opinions differ.) speakers is that it tests my English to the limit, if not to destruction.

Sometimes it’s quite clear to me how I should reword; at others, I’m unsure either of whether my native-speaker intuition is going a bit wonky, or of whether I’m being unnecessarily picky. But then, as a lexicographer and translator by training, I’m preternaturally sensitive to the aura of individual words (how pretentious is that phrase?).

Usually, it’s not a question of grammar in the sense of basic word order (though placement of adverbial phrases can be an issue), verb agreement, or use of tenses (though that is a problem for speakers of some languages). Much more often difficulties arise either a) because a word with the wrong connotations is used, or b) because there is an incongruous combinations of words, a pairing that on the surface is as unlikely as Charles and Diana.

It’s all Dutch to me

When I come across a), I sometimes wonder whether the author has used either a not very good dictionary or a thesaurus. However, that cannot be true of one particular author, a Dutch academic – and very few nations are as good at English as the Dutch.

When they wrote “…were subject to the composer’s artistic ambition, and never on the receiving end of his gifts and affection” it is probably clear to most people what is wrong: you are usually “on the receiving end” of something unpleasant, so there is an obvious linguistic dissonance here, unless the intention was ironic, which is not what the surrounding context suggested.

The phrase has what is known in some circles as a “negative semantic prosody”. In confirmation of that, the Oxford online dictionary defines it thus:

to be the (unfortunate) recipient of some action, event, etc.; to be subjected to something unpleasant.

When the author wrote “In other words, both narratives testify to the common disposition to either sentimentalize or ridicule creativity…”, it was the word disposition that caught my eye. However, this is not such a cut-and-dried case.

It is perfectly correct in that it is a synonym for “tendency, inclination”, so what was wrong with it? I replaced it with tendency without second thoughts. You could say that was unnecessary, but I would maintain that in the interests of idiomatic English it was at least desirable.

Man proposes, God disposes

Sir Edwin Landseer’s painting of the same title, commemorating the disastrous 1845 expedition to explore the Northwest passage in which all crew members died.

Now, coming back to it, it strikes me that it does not work for several reasons.

Meaning

First, the key difference is that semantically disposition seems usually to be something individual rather than collective.

The handful of examples in the online Oxford Dictionary tend to confirm its being an individual property:

the Prime Minister has shown a disposition to alter policies

the judge’s disposition to clemency

Subsequent lapses in devotion or attitude do not alter God’s disposition to save the individual.

True, the terms of entry were not clearly canvassed, but we may assume a clear disposition to favour New Zealand entry.

Religious reawakening was needed to strengthen people’s innate disposition to distinguish right from wrong.

The actors in the first three examples, dear old God included, are single individuals.

In the fourth, the actor is not specified, but we can assume that they were either a country or an institution viewed as an “honorary” person.

In the fifth example, the actor is a singular noun with a collective meaning.

There is also something else to do with the meaning which I can’t exactly define, but it’s along the lines of a disposition being something psychologically inherent, possibly innate. That idea is supported by the type of discourse in which the word typically occurs.

Register/domain

From its usually being a property of individuals it follows that a disposition is unlikely to be “common”, as in the quotation by the Dutch academic.

In fact, in the corpus I consulted (the Oxford English Corpus, OEC), the collocation “common disposition” occurs only three times. One of them is in a quotation from a translation of On The Duty of Man and Citizen According to the Natural Law (1673) by Samuel von Pufendorf, a German Enlightenment philosopher:

…so if we have examined the common disposition of men and their condition, it will be readily apparent upon what laws their welfare depends.

Book 1, Cap. 3, 1

That quotation has the weightiness of political philosophy. In the OEC, well over 60 per cent of the citations for disposition followed by an infinitive were from the Philosophy domain. Another 30 per cent were from Science or the Social Sciences. The preponderance of those contexts for the word provides another post hoc explanation of my decision.

So much for nuances of meaning. But what about odd collocations?

The interweb being what it is, images for “keeping abreast of ” were as you might imagine. As I like my images, this will have to do instead.

In a paper I edited recently I was struck by the phrase “to keep abreast with…” With? My reaction was (Shome mishtake, shurely? Ed), as Private Eye would put it.

It’s abreast of, isn’t it? Pondering whether to change “with” to “of”, I had to be sure and checked in my corpus. You could ov knockt me down with a feather when I discovered that abreast of in the relevant meaning cropped up only 7 times, but abreast with well over 100 times. I started to investigate further. While other corpora showed that the ratio above was far from representative, they also showed that there seem to be major regional differences in the use of the two collocations. This is something I will explore in the next blog.

Filed under: Grammar, Help for writers & editors

“Keep abreast of” or “keep abreast with”? An editor’s dilemma (1/2)

For my sins, one of the things I do is “quality-check” the work of other editors. I do this for an organization that pays editors to copy-edit academic papers written by non-native speakers.

(I also copy-edit such papers myself, which is often extremely interesting as it opens up whole new worlds never dreamt of in my philosophy, from Game Theory applied to the Torah to assessing the quality of new housing for flood victims in the Philippines.)

Actually, I say “for my sins”, but mostly it is really rather enjoyable: the editors generally do an excellent job, and I only have to make a minimum of changes.

If you take hyphens seriously, you will surely go mad

“I get paid by the word.”

That phrase is attributed, I believe, to an OUP editor. In my quality-checking role I have to take them seriously: of my sanity, only my friends and family can give you an unbiased opinion.

Two recurring issues in what I check are hyphenation and defining vs non-defining relative clauses. On the first, editors often leave out essential hyphens, e.g. “low-level” as a compound attributive adjective. With relative clauses, they often leave out the comma before a non-defining clause, an omission which often changes the meaning significantly.

‘I’ll agree to a fifty-fifty split, but I get the hyphen.’

One of the other things that editing papers by non-mother tongue (now, should there be a hyphen between “mother” and “tongue”? Opinions differ.) speakers is that it tests my English to the limit, if not to destruction.

Sometimes it’s quite clear to me how I should reword; at others, I’m unsure either of whether my native-speaker intuition is going a bit wonky, or of whether I’m being unnecessarily picky. But then, as a lexicographer and translator by training, I’m preternaturally sensitive to the aura of individual words (how pretentious is that phrase?).

Usually, it’s not a question of grammar in the sense of basic word order (though placement of adverbial phrases can be an issue), verb agreement, or use of tenses (though that is a problem for speakers of some languages). Much more often difficulties arise either a) because a word with the wrong connotations is used, or b) because there is an incongruous combinations of words, a pairing that on the surface is as unlikely as Charles and Diana.

It’s all Dutch to me

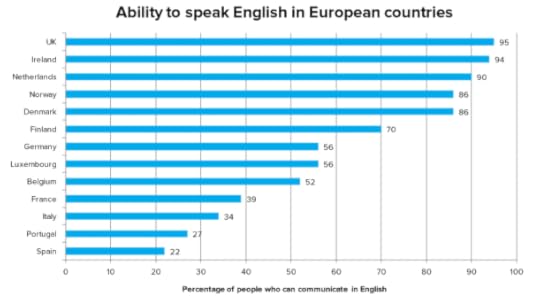

When I come across a), I sometimes wonder whether the author has used either a not very good dictionary or a thesaurus. However, that cannot be true of one particular author, a Dutch academic – and very few nations are as good at English as the Dutch.

When they wrote “…were subject to the composer’s artistic ambition, and never on the receiving end of his gifts and affection” it is probably clear to most people what is wrong: you are usually “on the receiving end” of something unpleasant, so there is an obvious linguistic dissonance here, unless the intention was ironic, which is not what the surrounding context suggested.

The phrase has what is known in some circles as a “negative semantic prosody”. In confirmation of that, the Oxford online dictionary defines it thus:

to be the (unfortunate) recipient of some action, event, etc.; to be subjected to something unpleasant.

When the author wrote “In other words, both narratives testify to the common disposition to either sentimentalize or ridicule creativity…”, it was the word disposition that caught my eye. However, this is not such a cut-and-dried case.

It is perfectly correct in that it is a synonym for “tendency, inclination”, so what was wrong with it? I replaced it with tendency without second thoughts. You could say that was unnecessary, but I would maintain that in the interests of idiomatic English it was at least desirable.

Man proposes, God disposes

Sir Edwin Landseer’s painting of the same title, commemorating the disastrous 1845 expedition to explore the Northwest passage in which all crew members died.

Now, coming back to it, it strikes me that it does not work for several reasons.

Meaning

First, the key difference is that semantically disposition seems usually to be something individual rather than collective.

The handful of examples in the online Oxford Dictionary tend to confirm its being an individual property:

the Prime Minister has shown a disposition to alter policies

the judge’s disposition to clemency

Subsequent lapses in devotion or attitude do not alter God’s disposition to save the individual.

True, the terms of entry were not clearly canvassed, but we may assume a clear disposition to favour New Zealand entry.

Religious reawakening was needed to strengthen people’s innate disposition to distinguish right from wrong.

The actors in the first three examples, dear old God included, are single individuals.

In the fourth, the actor is not specified, but we can assume that they were either a country or an institution viewed as an “honorary” person.

In the fifth example, the actor is a singular noun with a collective meaning.

There is also something else to do with the meaning which I can’t exactly define, but it’s along the lines of a disposition being something psychologically inherent, possibly innate. That idea is supported by the type of discourse in which the word typically occurs.

Register/domain

From its usually being a property of individuals it follows that a disposition is unlikely to be “common”, as in the quotation by the Dutch academic.

In fact, in the corpus I consulted (the Oxford English Corpus, OEC), the collocation “common disposition” occurs only three times. One of them is in a quotation from a translation of On The Duty of Man and Citizen According to the Natural Law (1673) by Samuel von Pufendorf, a German Enlightenment philosopher:

…so if we have examined the common disposition of men and their condition, it will be readily apparent upon what laws their welfare depends.

Book 1, Cap. 3, 1

That quotation has the weightiness of political philosophy. In the OEC, well over 60 per cent of the citations for disposition followed by an infinitive were from the Philosophy domain. Another 30 per cent were from Science or the Social Sciences. The preponderance of those contexts for the word provides another post hoc explanation of my decision.

So much for nuances of meaning. But what about odd collocations?

The interweb being what it is, images for “keeping abreast of ” were as you might imagine. As I like my images, this will have to do instead.

In a paper I edited recently I was struck by the phrase “to keep abreast with…” With? My reaction was (Shome mishtake, shurely? Ed), as Private Eye would put it.

It’s abreast of, isn’t it? Pondering whether to change “with” to “of”, I had to be sure and checked in my corpus. You could ov knockt me down with a feather when I discovered that abreast of in the relevant meaning cropped up only 7 times, but abreast with well over 100 times. I started to investigate further. While other corpora showed that the ratio above was far from representative, they also showed that there seem to be major regional differences in the use of the two collocations. This is something I will explore in the next blog.

Filed under: Grammar, Help for writers & editors

“Abreast of” or “abreast with”? An editor’s dilemma (1/2)

For my sins, one of the things I do is “quality-check” the work of other editors. I do this for an organization that pays editors to copy-edit academic papers written by non-native speakers.

(I also copy-edit such papers myself, which is often extremely interesting as it opens up whole new worlds never dreamt of in my philosophy, from Game Theory applied to the Torah to assessing the quality of new housing for flood victims in the Philippines.)

Actually, I say “for my sins”, but mostly it is really rather enjoyable: the editors generally do an excellent job, and I only have to make a minimum of changes.

If you take hyphens seriously, you will surely go mad

“I get paid by the word.”

That phrase is attributed, I believe, to an OUP editor. In my quality-checking role I have to take them seriously: of my sanity, only my friends and family can give you an unbiased opinion.

Two recurring issues in what I check are hyphenation and defining vs non-defining relative clauses. On the first, editors often leave out essential hyphens, e.g. “low-level” as a compound attributive adjective. With relative clauses, they often leave out the comma before a non-defining clause, an omission which often changes the meaning significantly.

‘I’ll agree to a fifty-fifty split, but I get the hyphen.’

One of the other things that editing papers by non-mother tongue (now, should there be a hyphen between “mother” and “tongue”? Opinions differ.) speakers is that it tests my English to the limit, if not to destruction.

Sometimes it’s quite clear to me how I should reword; at others, I’m unsure either of whether my native-speaker intuition is going a bit wonky, or of whether I’m being unnecessarily picky. But then, as a lexicographer and translator by training, I’m preternaturally sensitive to the aura of individual words (how pretentious is that phrase?).

Usually, it’s not a question of grammar in the sense of basic word order (though placement of adverbial phrases can be an issue), verb agreement, or use of tenses (though that is a problem for speakers of some languages). Much more often difficulties arise either a) because a word with the wrong connotations is used, or b) because there is an incongruous combinations of words, a pairing that on the surface is as unlikely as Charles and Diana.

It’s all Dutch to me

When I come across a), I sometimes wonder whether the author has used either a not very good dictionary or a thesaurus. However, that cannot be true of one particular author, a Dutch academic – and very few nations are as good at English as the Dutch.

When they wrote “…were subject to the composer’s artistic ambition, and never on the receiving end of his gifts and affection” it is probably clear to most people what is wrong: you are usually “on the receiving end” of something unpleasant, so there is an obvious linguistic dissonance here, unless the intention was ironic, which is not what the surrounding context suggested.

The phrase has what is known in some circles as a “negative semantic prosody”. In confirmation of that, the Oxford online dictionary defines it thus:

to be the (unfortunate) recipient of some action, event, etc.; to be subjected to something unpleasant.

When the author wrote “In other words, both narratives testify to the common disposition to either sentimentalize or ridicule creativity…”, it was the word disposition that caught my eye. However, this is not such a cut-and-dried case.

It is perfectly correct in that it is a synonym for “tendency, inclination”, so what was wrong with it? I replaced it with tendency without second thoughts. You could say that was unnecessary, but I would maintain that in the interests of idiomatic English it was at least desirable.

Man proposes, God disposes

Sir Edwin Landseer’s painting of the same title, commemorating the disastrous 1845 expedition to explore the Northwest passage in which all crew members died.

Now, coming back to it, it strikes me that it does not work for several reasons.

Meaning

First, the key difference is that semantically disposition seems usually to be something individual rather than collective.

The handful of examples in the online Oxford Dictionary tend to confirm its being an individual property:

the Prime Minister has shown a disposition to alter policies

the judge’s disposition to clemency

Subsequent lapses in devotion or attitude do not alter God’s disposition to save the individual.

True, the terms of entry were not clearly canvassed, but we may assume a clear disposition to favour New Zealand entry.

Religious reawakening was needed to strengthen people’s innate disposition to distinguish right from wrong.

The actors in the first three examples, dear old God included, are single individuals.

In the fourth, the actor is not specified, but we can assume that they were either a country or an institution viewed as an “honorary” person.

In the fifth example, the actor is a singular noun with a collective meaning.

There is also something else to do with the meaning which I can’t exactly define, but it’s along the lines of a disposition being something psychologically inherent, possibly innate. That idea is supported by the type of discourse in which the word typically occurs.

Register/domain

From its usually being a property of individuals it follows that a disposition is unlikely to be “common”, as in the quotation by the Dutch academic.

In fact, in the corpus I consulted (the Oxford English Corpus, OEC), the collocation “common disposition” occurs only three times. One of them is in a quotation from a translation of On The Duty of Man and Citizen According to the Natural Law (1673) by Samuel von Pufendorf, a German Enlightenment philosopher:

…so if we have examined the common disposition of men and their condition, it will be readily apparent upon what laws their welfare depends.

Book 1, Cap. 3, 1

That quotation has the weightiness of political philosophy. In the OEC, well over 60 per cent of the citations for disposition followed by an infinitive were from the Philosophy domain. Another 30 per cent were from Science or the Social Sciences. The preponderance of those contexts for the word provides another post hoc explanation of my decision.

So much for nuances of meaning. But what about odd collocations?

The interweb being what it is, images for “keeping abreast of ” were as you might imagine. As I like my images, this will have to do instead.

In a paper I edited recently I was struck by the phrase “to keep abreast with…” With? My reaction was (Shome mishtake, shurely? Ed), as Private Eye would put it.

It’s abreast of, isn’t it? Pondering whether to change “with” to “of”, I had to be sure and checked in my corpus. You could ov knockt me down with a feather when I discovered that abreast of in the relevant meaning cropped up only 7 times, but abreast with well over 100 times. I started to investigate further. While other corpora showed that the ratio above was far from representative, they also showed that there seem to be major regional differences in the use of the two collocations. This is something I will explore in the next blog.

Filed under: Grammar, Help for writers & editors

August 12, 2016

Elusive or illusive or allusive? Commonly confused words (17-18)

Beware of writing illusive when you mean that something or someone is hard to find, pin down, or define. The correct word and spelling are elusive .

Correct: Yet happiness is an elusive concept, rather like love.—OEC, 2002;

Incorrect: Sharks up to forty feet are quite common, although when Helen was there they proved to be X illusive.—OEC, 2005.

If you use Word, the spelling and grammar check will query illusive.

If you want to suggest that something is an illusion, illusory is much more frequent than illusive, and a safer choice (readers will be in no doubt about what you mean):

Correct: …a Buddhist monk advised him, “You must first realize the illusory nature of your own body”.—OEC, 2003.

In written texts, X illusive is more often used by mistake than in its true meaning, though many examples are ambiguous.

The word allusive is also occasionally used by mistake for elusive.

The blog gives plenty of examples of appropriate and mistaken use.

If you feel confident that you already know all this, why not try the self-test at the bottom of the blog?

For the full story, read on…

(If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column, above the Twitter feed) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!)

Why does the mistake happen?

The reason seems pretty obvious: the words sound the same: i-l(y)oo-siv (/ɪˈl(j)uːsɪv/.) If you don’t edit your writing carefully the mistake could slip through, because your spellchecker might accept illusive as a legitimate word. Which it is, but, very often, probably not the one you meant!

What is the difference?

Elusive…

relates to the verb “to elude”. So, something elusive eludes or escapes you, is difficult to grasp physically or mentally.

A classic example is from that golden oldie by Bob Lind, Elusive Butterfly:

Across my dreams, with nets of wonder,

I chase the bright, elusive butterfly of love.

Justin Timberlake trying to be elusive.

Things that are often elusive are creatures, foes, beasts…and Justin Timberlake. If people describe him as elusive, that means he is hard to track down and photograph or interview; if they were chasing the illusive Justin Timberlake, they would be implying something about his very existence, or about his skill at creating illusions.

If people describe a concept as elusive, they mean it is hard to pin down, explain, or define; if they describe it as X illusive, they may possibly mean that it is indeed an illusion, but as often as not it is the wrong word choice. In the next example the appropriate word has been used:

If the situation in western Pakistan continues to deteriorate, success will be elusive and very difficult to achieve.—OEC, 2009.

What about illusive?

A superb Raeburn portrait of Sir Walter Scott with his dogs.

It means, as the Collins Dictionary puts it, “producing, produced by, or based on illusion; deceptive or unreal”. It has a rather literary ring to it, as in Sir Walter Scott’s:

’Tis now a vain illusive show,

That melts whene’er the sunbeams glow.

Modern examples include:

…a film essay about the real and illusive nature of motion pictures.—Senses of Cinema, 2002

(after all, films produce an illusion in the mind of the viewer);

Gaskell [i.e. Mrs Gaskell, the novelist] did not sentimentalize or yield to the illusive attractions of the English pastoral idyll.—Criticism, 2000

(the attractions were indeed an illusion, since country life was harsh and poverty-stricken).

Illusive by mistake

However, the data in the Oxford English Corpus demonstrate how often illusive appears by mistake for elusive. A roughly 10-per cent sample (50 examples) of all occurrences contained 23 in which illusive was clearly a mistake:

…but even after a decade, his [i.e. Ricardo Chailly’s] musical character remains strangely X illusive and lacking any special definition.—New York Metro, 2004

(the intended meaning must be “hard to define” and therefore should be elusive);

During the long period we spent waiting for this X illusive good weather, there was also tragedy on the mountain—Everest Expedition dispatches, 2003

(my reading is that the good weather came only sporadically, but the sentence is conceivably ambiguous).

Of the other 28 examples, only 12 unequivocally used—at least by my reading—the true meaning of the word:

…this illusive common interest, this notion of shared stakes encompassed the whole world and large majorities in almost every society .—Free India Media, 2004

(the left-leaning nature of the text suggests that common interest between the ruling classes and the ruled is indeed an illusion).

But 15 were ambiguous to me, and in some cases it was impossible to work out quite what the writer intended:

After a troubled season at Arsenal, Bergkamp was his illusive best on Friday night, dropping off Kluivert and playing a part in almost all of Holland’s better moments.—Sunday Herald, 2000

Was Bergkamp hard to pin down and tackle, or a master of illusion through feints?

The Corpus of Web-Based Global English (GloWbE) presents a similar picture. For example, a search for illusive and any words following within three spaces yields this top ten:

man, quality, power, concept, nature, dream, leopard, creatures, happiness, desire.

Nearly all the quotations for man are for the “Illusive Man” in a video game. I have no idea whether the word is a deliberate pun in this context.

Of the remainder, quality, concept, leopard, and creatures self-evidently match elusive. Dream and desire similarly correspond to illusive; power, nature, and happiness could go with either, but in the GloWbE contexts are appropriately described as illusive.

illusive/illusory

Illusory has the same definition as illusive. According to the OED, it was first recorded in a letter of 1599 by no less a personage than Elizabeth I (though it looks like a noun),  and then by John Donne.

and then by John Donne.

To trust him uppon pledges is a meare illusorye.—1599

A false, an illusory, and a sinfull comfort.—Sermons, X. 51, before 1631

Illusive appeared nearly a century later (1679) according to the OED, in the blood-curdlingly titled The narrative of Robert Jenison, containing 1. A further discovery and confirmation of the late popish plot. 2. The names of the four ruffians, designed to have murthered the king…

Which is it better to use?

If you really mean to convey the idea that something is an illusion, I’d be tempted to go for illusory, as the more common word, and in order to dispel any suspicion that you meant elusive. In the OEC it is roughly eight times more frequent than illusive:

“…they give the Palestinians the illusory feeling that via a unilateral strategy and parliamentary resolutions they can obtain their political aspirations,” foreign ministry spokesman Emanuel Nachshon told The Irish Times.—10 December, 2014.

So that’s that all sorted out, then

If only… Another word (a near homophone) sometimes gets snarled up in this tangle of meaning. It is allusive, the adjective corresponding to “allusion” and used mainly by literary critics, film critics, and the like. Some poetry, such as T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, is highly allusive, since it constantly alludes (i.e. refers indirectly) to other texts, poetic or otherwise.

Although there is no question that Ulysses provided a supreme example of the allusive method in action, deployed on a breathtaking scale, Eliot’s almost insatiable appetite for allusion sprang from other sources as well.—T.S. Eliot: The Modernist in History, ed. Ronald Bush, 1991

But people occasionally use it by mistake. I heard the pronunciation “allusive” referring to whales in a recent BBC trailer for a nature programme. And if you search for “The Allusive Butterfly of Love” online you will find quite a few examples.

More mistaken examples:

Picking up a taxi from Epping tube station, it was another half an hour finding the X allusive final destination.—Ideas Factory, 2004

Give John Kerry this. He’s maddeningly X allusive—OEC, 2004

Given the prevailing muddle over the meaning of these words, it is perhaps not surprising that one has to turn to literary titans to see them used with absolute precision: at a conference in August 2004, Vikram Seth memorably and alliteratively defined writing as “allusive, elusive and illusive”.

Fun test

Choose between allusive, elusive, and illusory:

Although his restless experimentation and complex, _________ style often prove difficult on first reading, his novels possess a complexity and depth that reward the demands he makes upon his readers.

Dylan is notoriously _________; as he wrote on the album notes to Highway 61 Revisited , “there is no I—there is only a series of mouths .”

The hint that the possibility exists for real and not _________ happiness and love appears fleetingly in a few of Sirk’s earlier Universal-International films.

...the Convention is interpreted and applied in a manner which renders its rights practical and effective, not theoretical and _________.

But in one area, success is _________: The city’s rats remain as bold and showy as ever, darting through well-lighted subway stations as…

1. allusive 2. elusive 3. illusory 4. illusory 5. elusive

Filed under: Advice for writers, Confusable words Tagged: easily confused words

July 15, 2016

“All of a sudden” or “all of the sudden”? And “out of the sudden”?

Ain’t English wonderful!

Or, more truthfully, ain’t its speakers wonderful!

Despite all attempts to confine the language, some speakers will always manage to wriggle out of any straitjacket. Here’s a case in point: there’s a standard adverbial all of a sudden. But there’s also a minority variant, ?all of the sudden. And then there’s ?out of the sudden.

Actually, while all of a sudden trips naturally off the tongue or the keyboard (to coin a phrase), its grammar is mildly interesting for the reasons given at the end of this blog. But back to the topic in hand…

Quick takeaways

All of the sudden is used – by a minority of speakers, possibly younger speakers.

Most people will consider it wrong.

Historically, there has been a lot of a/the variation in the slot “of – sudden”, but not with all of a sudden .

Contrary to rumour, the Bard of Avon did not coin the phrase all of a sudden (see citations lower down).

Take Our Poll

All of the sudden

“Don’t be daft!” I hear you say. “Nobody says that, do they?” (“Pshaw and fiddlesticks. Pig ignorance, I call it!”)

We can’t tell exactly how many people say it, but it does occur in written corpus sources. In the Corpus of Contemporary American (COCA), all of the sudden occurs 294 times, compared to all of a sudden’s whopping 6,836 occurrences.

What’s noticeable, first, is that the biggest chunk is in the spoken segment (58%). In the academic segment there is just one example.

Second, frequency, though still very low, seems to be increasing over time: from 0.3 per million (1990–1995) to 0.67 (2010–2015).

Third, the percentage in COCA of all of the sudden out of the totals of both versions is 4.1%, so it’s very much a minority phrasing – at the moment. Similarly small percentages are reflected in the data in the Global Corpus of Web-Based English (GloWbE) and in the NOW (News on the Web) corpus – 5.3% and 3.7%.

Fourth – and many British speakers will sigh, shake their heads, and tut-tut at this point – all of the sudden is chiefly US and Canadian: in NOW it is seven times more frequent per million words in US English than in British English.

Out of the sudden

You what? Yessiree!

If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column, above the Twitter feed) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

I heard an American witness to the horrific events in Nice using the phrase. It was completely new to me, so I thought I’d check it out. A Google “…” search throws up 169,000 results. I skimmed the first few pages. Of course, many of them are not a set phrase at all, but rather out of the sudden + N, e.g. “…when we stepped into the lively, warm, candlelit bar out of the sudden April downpour, it was a welcome sight.”

But many of them are the set phrase, e.g.

Yesterday I played a bit with the setup, enjoyed some games on FBA and then out of the sudden, the hotkey has no function anymore.

What is one to make of this? It looks like a combination of out of the (blue) + (all of a/the) sudden.

It’s not really a standard eggcorn: there is no obvious homophone link — all of a/out of the are hard to confuse, aren’t they?; there is no clear meaning re-interpretation, because the change is largely syntactic; and it affects more than a single word. But, hey presto, there’s a potential term for it: a blidiom, i.e. an idiom blend.

Perhaps it is very much a spoken phrase, which then ends up being written online and thereby picked up by Google. That would explain why Google has so many examples despite the phrases rarity in both GloWbE and NOW. In the first, the string out of the sudden occurs 20 times, but only 13 are the set phrase, the other seven having a noun following; in NOW, only one out of six is the set phrase, which might just possibly reflect the fact that NOW consists of news sites, whereas GloWbE consists 60 per cent of informal blogs.

Is there any reason why it has to be all of A sudden?

Idiom, dear boy, idiom. As Fowler said “that is idiomatic which it is natural for a normal Englishman to say or write ; … ; grammar & idiom are independent categories”.

It’s the current majority convention, but it wasn’t always so.

Historically, there has been a lot of see-sawing, not only between the indefinite/definite article, but also with the preposition: variations – without the word all – are of/on/upon/at/in + a/the + sudden.

Is it possible That loue should of a sodaine take such hold?

The Taming of the Shrew, before 1616, i. i. 145

As he gazed, he saw of a sudden a man steal forth from the wood.

Conan Doyle, White Company, 1890.

My Crop promis’d very well, when on a sudden I found I was in Danger of losing it all again.

Defoe, Robinson Crusoe, 1719

The earliest OED (1558) citation of the phrase is in the form of the sudden:

To be…done…for more reasonable hier in hope of present payment then can be had or done upon the soden.

in A. Feuillerat Documents Office of Revels Queen Elizabeth, (1908) 17

The first citation of the “canonical” form is this, nearly 130 years later than the first, 1558, citation:

All of a sudden, and without any…previous Instructions, they were heard to speak…in the fifteen several Tongues of fifteen several Nations.

J. Scott, Christian Life: Pt. IIII. vii. 601, 1686

A sad song in Bahasa, with translation.

Do usage guides say anything?

There was some discussion a while back on Stack Exchange. A specious suggestion that all of the sudden might be logical when referring back to an event already mentioned, thereby justifying the specificity of the definite article, received the memorably aphoristic reply: “Idiom trumps logic.” Fowler would undoubtedly have concurred.

Paul Brians’ Errors in English Usage notes it, while the Phrase Finder mentions it, attributes it wrongly to Shakespeare, and suggests it is preferred by “the young”.

Oh, and the WordPress spell checker ain’t having none of all of the sudden.

Some grammar points

Sudden is primarily an adjective, but here it’s being used as a noun. There’s nothing too unusual about that in itself: “out of the blue” similarly turns an adjective into a noun.

Before searching in COCA, I had expected all of a to be immediately followed by a singular noun in most cases. In contrast, nearly all examples are for the set phrase all of a sudden . The very few examples with a noun are all of the type all of a + SG N’S + SG/PL N” as in “all of a cell’s DNA/a hospital’s procedures”.

The only other set phrase that crops up in COCA is all of a piece, e.g. “The aim of American movies in the thirties…was to appear seamless, all of a piece…”.

All is being used here as an intensifying adverb, as in “She’s come over all shy”, a use marked in Oxford online as informal. Another example given by Oxford is “He was all of a dither.”

Filed under: Grammar, Meaning of words, Style

July 1, 2016

“Suffice it to say” or “suffice to say”?

The plot makes twists and turns like a snake writhing in the desert. To tell would be to spoil, but suffice to say, writer, director and cast have colluded brilliantly.

Fraser’s scenes are painfully boring to watch—suffice it to say, he’s not a master of physical comedy.

Take Our Poll

An editor in an online editorial group raised the question of which version is correct, and her query elicited more than 80 comments. Many people swore that suffice to say was the correct and only version, and that suffice it to say was a “hairy mutant”. People in the other camp lambasted their opponents, and resorted to dictionaries to prove beyond a doubt that the four-word version was gospel. What is the truth of the matter?

Quick takeaways

Both forms are in use (see more detail at Frequency below).

Suffice it to say is slightly more frequent in a British corpus, and much more frequent in an American one.

Suffice it to say was formerly considered standard, and is still seen by many people as the only correct formulation.

However, possibly because of its puzzling syntax, it is often “regularized” to suffice to say.

The traditional formula is still widely used, and useful, despite being considered pompous or old-fashioned by some.

There are strange variations on it, such as sufficed to say and the eggcornish surface it to say.

Below, I look in more detail at the grammar, frequency and history of this phrase, which the Oxford Dictionary Online aptly defines as “Used to indicate that one is saying enough to make one’s meaning clear while withholding something for reasons of discretion or brevity.”

Meanwhile, the results of the poll embedded in this blog show that the option with most votes is that both versions are ‘correct’. Which you use is likely to depend on where you’re from, how you first heard or used the phrase, and how you parse it, among other things.

If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column, above the Twitter feed) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

Syntax

Three things are worth mentioning about suffice it to say. First, the subject of the sentence is the “dummy” or impersonal it. Second, the verb form is subjunctive—the absence of the normal third person singular –s shows this, i.e. suffice, rather than suffices. Third, there is subject-verb inversion.

The phrase thus belongs to that very small group of “fossilized” phrases in which the subjunctive is used: God save the Queen! far be it from me to…, Perish the thought! All of them could be rewritten as “Let + subject + verb” i.e. let God save the Queen, let it suffice to say, etc. In particular, far be it from me displays the same subject-verb inversion.

However, the fact that such subjunctive phrases are rare and on the fringes of most people’s grammar means, I believe, that they have difficulty analyzing the “suffice it to say” form, and therefore attempt to regularize it to “suffice to say”. The inversion of subject and verb presents a further block to analysis.

It has also become clear to me, from discussion of this issue in online editorial forums—or fora, if you really, absolutely must—that some people interpret the it as the object of the verb suffice. As a result, they reject it, correctly, in so far as they perceive suffice to be intransitive in this use, but incorrectly if one analyses the phrase as having subject-verb inversion.

“Suffice to say”, however, while sounding superficially like a second person imperative—stand up, wake up, pay attention, etc.—is as anomalous as the four-word form. Who is being addressed in this imperative?

Current situation

Frequency

The Oxford English Corpus (OEC) has slightly more examples of the string “suffice to say” than of “suffice it to say”: 952:937 (and each occurs less than once per million words of text.) However, filtering out “suffice to say” as a zero infinitive, i.e. in phrases such as let it suffice to say, it should suffice to say, etc., reduces its total to well below 900, making it, therefore, less frequent than the longer form.

Though the shorter form is used in all varieties of English, its use does seem to be particularly marked in Australian English, at least in the OEC data.

In the Corpus of Contemporary American the distribution is very different: 376 occurrences of the longer version against 97 for the shorter. It is particularly noticeable that in academic writing the longer form occurs in an even higher ratio of 6:1.

A Google Ngrams comparison of “suffice to say” and “suffice it to say” suggests a decline in the use of both phrases over the last century, However, “suffice to say” is often the zero infinitive mentioned previously, and it would be too time-consuming to compare the frequency of the two phrases in detail over time. For the period 1960-2000 (i.e., the latest period covered by Ngrams) “suffice it to say” is the more frequent of the two strings.

Dictionaries

Both the Oxford Online Dictionary and Macquarie bracket the it: suffice (it) to say, indicating clearly that they accept it as optional. Merriam-Webster Online notes “often used with an impersonal it Collins shows only the complete phrase.

History

The earliest use of the verb suffice recorded in the unrevised OED (1915) entry is from 1325:

The OED‘s first example of an impersonal use is from the Wycliffite version of the Bible:

He cam the thridde tyme, and seith to hem, Slepe ȝe nowe, and reste ȝe; sothli it sufficith.

Mark xiv. 41

There is then a separate category with the following rubric:

“Const[ruction] inf[initive] or clause with, or (formerly) without, anticipatory dummy subject it. Now chiefly in the subjunctive, suffice it, sometimes short for suffice it to say.”

The first OED citation of this use is from the Middle English (1390) Confessio Amantis, showing an infinitive as the subject of the verb:

to studie upon the worldes lore Sufficeth now withoute more.

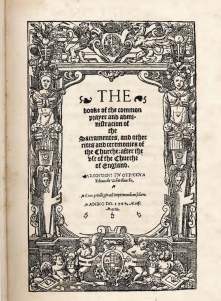

There is one more citation before  the Book of Common Prayer on Publyke Baptisme f. iiii*v (1549) showing a similar infinitive construction.

the Book of Common Prayer on Publyke Baptisme f. iiii*v (1549) showing a similar infinitive construction.

If the childe be weake, it shall suffice to powre water vpon it.

However, the first citation for the exact phrase “suffice it to say” does not appear until a 1779 edition of the periodical The Mirror:

Suffice it to say, that my parting with the Dervise was very tender.

An earlier citation (1692), however, has:

It suffices to say, That Xantippus becoming the manager of affairs, altered extreamly the Carthaginian Army.

In the Corpus of Historical American (COHA), the string “suffice to say” is mainly of the zero infinitive type mentioned above. However, the earliest citation of it independently is in 1815, in the drama by Edward Hitchcock the Emancipation of Europe, or The Downfall of Bonaparte: Marshal Ney, no less, replies to a question from Talleyrand, no less, about how a battle went:

Oh most murderous! Too horrid to relate. Suffice to say Our troops are overwhelmed in toto.

The next example from COHA is from Around the Tea-Table (1847), by T. De Witt Talmage (now, there’s a moniker for you!), author, as his title page proclaims, of “Crumbs Swept Up,” “Abominations of Modern Society,” “Old Wells Dug Out,” Etc.

Perhaps it was gout, although his active habits and a sparse diet throw doubt on the supposition. Suffice to say it was a thorn — that is, it stuck him. It was sharp.

Five O’Clock Tea by American painter Julius LeBlanc Stewart (1855 – 1919)

“Suffice to Say”—a long-forgotten hit

Googling in connection with this topic, I discovered a 1977 hit by a band called The Yachts. Here are some of the lyrics:

Although the rhyming’s not that hot | It’s quite a snappy little tune | I’m sure you’ll like the chorus too | It’s short and sweet and to the point | It even says that I love you | Just after this: Suffice to say you love me | Can’t say that I blame you | Suffice to say I love you too

Clearly, leaving out it was necessary on rhythmical grounds. And if you want to relive your on-the-fringes-of-Punk days with this little ditty, here it is:

Filed under: Advice for writers, Confusable words, Grammar, Meaning of words, Word origins Tagged: Subjunctive

June 1, 2016

Putting The Kibosh On Cassidy

An interesting investigation into an idiom that has been claimed to be Irish. The OED (1901) notes ‘origin obscure: It has been stated to be Yiddish or Anglo-Hebraic’.

In Daniel Cassidy’s worthless book of fake etymology, he claimed that the word kibosh or kybosh is of Irish origin. Cassidy was certainly not the first to claim this and his sole authority for saying it was a website called Cork Slang Online. The usual claim in relation to its supposed Irish origin is that it comes from caidhp bháis or caidhp an bháis or caip bháis, meaning a cap or cape of death. Some sources also mention cie báis, but cie is not a possible word in Irish orthography.

While caidhp bháis is given as the name of a fungus in Irish dictionaries (the death cap), there is no evidence that this is an ancient expression and it may have been composed on the pattern of the English phrase death cap in the 20th century.

There are various explanations for the meaning of caidhp bháis as…

View original post 570 more words

Filed under: Uncategorized

May 19, 2016

No problemo! What kind of Spanish is that?

Is this a sham marriage?

Troy:

Sure, baby. Is that a problemo?

Troy from The Simpsons uses problemo on its own, as a noun, but it’s usually part of “no problemo” – famously used in the Terminator movies by Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Where does it come from?

Where does this little phrase come from? It’s been around since 1985 and I had thought it was now rather passé, but Google Ngrams and the Oxford Twitter corpus suggest it is still going strong.

Originally a creation of US English, it is now used in British English and elsewhere. It features in several dictionaries, including the Oxford English Dictionary (OED).

People use it broadly in two ways: to show that they are willing to do or can do what someone asks (“I can pick you up, no problemo.”), and, when being thanked for doing something, to say that it was “no trouble.”

But it also has other, often sarcastic, overtones.

Sometimes, it’s an exclamation: “Well of course ignorance of the law is no excuse but this is Hillary Clinton – so, no problemo!”

At other times, it’s a kind of adverbial, as in this online restaurant review: “We had a lot of leftovers (SO not normal with Thai. I am a Thai addict and can polish off 6 entrees no problemo).”

Sometimes, it’s a noun: “In arguments on Arizona voting law, Scalia sees “’no problemo’ for state requirements“.

Is it Italian, Spanish, Esperanto, or what?

It’s a sort of spoof Spanish translation of the earlier (1955) English “no problem”, which has been Spanglishized by having an-o tacked on, to create a (reassuring or irritating, according to taste) little jingle.

Adding that little -o is part of a long tradition of creating cod Spanish nouns such as el creepo for a creep and El Smoggo or El Stinko as nicknames for El Paso, Texas.

To say that something was no trouble, i.e. “you’re welcome”, the traditional Spanish phrases are ¡De nada! (literally “of nothing”) and, rather more formally, ¡No hay de qué! (literally “there is not that for which [to thank me]”). People might also say ¡Un placer! or Es un placer.

A very masculine problem

Now, if a Spanish noun ends in –o, it’s a reasonable assumption that it refers to something or someone “masculine”. A cynic might say that, since men create most of the world’s problems, it seems appropriate that the Spanish word for “problem” should be masculine. And in fact it is.

But there’s a problem: the real Spanish word is el problemA. The el shows you unambiguously that it’s got cojones, yet it ends in an –a. How come?

It is true that most Spanish nouns ending in –a are feminine. But not all of them. Common exceptions include:

el clima = the climate

un cura = a priest

un día = a day

el idioma (inglés) = the (English) language

el mapa = the map

un problema = a problem (and many other scientific or technical words ending in -ma, e.g. el plasma, el programa, el sistema)

el tema = the topic

There’s a kind of commonsensical yet false assumption that in Romance languages that have the –o /-a alternation (Portuguese, Italian, Spanish) any noun ending in –a must be feminine. It’s an easy mistake to make, and one I’ve made myself.

Recently arrived in Argentina, and with only embryonic Spanish, I earned extra money by giving private English lessons, mostly to ladies who lunched – and lunched rather splendidly, at that. A prospective student asked me over the phone how I was going to find my way to her house, I caused great amusement by saying that I would use *la mapa. It then became a kind of catchphrase that she could tease me with whenever I made a mistake in Spanish. Of course, I never made that particular blunder again.

English speakers, assuming that all nouns ending in –a are feminine, often sex-change the correct ¡BuenOs días! to *¡Buenas días!

Conversely, they sometimes say *¡Buenos tardes! and *¡Buenos noches! instead of ¡Buenas—.

Both la tarde and la noche are feminine.

Artists, athletes, and astronauts

Some other “masculine” nouns ending in –a denote a rather select group of professions: el artista, el atleta, el astronauta, el espía, el guía. Actually, these nouns are androgynous. You use exactly the same form for men and women, changing the “article” and other words relating to the noun as appropriate:

El famoso artista español Pablo Picasso / La famosa artista mexicana Frida Kahlo

Mata Hari es una de las espías más famosas de la historia.

In a quote that includes two of our masculine –a words, el artista Picasso wrote

“Todo niño es un artista. El problema es cómo seguir siendo artista cuando uno crece.”

(“Every child is an artist. The problem is how to carry on being an artist when you grow up.”)

Self-test 1

There is a mistake in the Spanish of this quotation from Selina Scott’s book about her life in Majorca, A Walk in the High Hills. Can you spot it?

“A woman is telling him how the greenery will enhance the village, but Sancho is having none of it. ‘Problemas, muchas problemas,’ he says, shaking his head.”

Self-test 2

Can you supply the correct missing ending in these phrases that use the words discussed above?

El artista antes conocid_ como Prince.

El clima económic_ actual no es muy favorable para la gente joven.

Hombres armados dispararon el miércoles a un cur_ italian_ , hiriéndolo de gravedad.

Era un día espléndid_ de fiesta y de luz.

Vocabulario

actual = current

dispararon = shot

hiriéndolo = wounding him

la luz = light

Filed under: Meaning of words, Spanish, Word origins

May 16, 2016

The rain in Spain … mainly on the … ; What does it mean and where’s it from?

Everyone knows the saying “the rain in Spain…”, but where does it come from and what does it mean?

Let’s get one thing straight, first: the exact original wording of this phrase that has taken root so strongly in English. Is it:

Take Our Poll

I had always assumed that it came from the 1964 film of the musical My Fair Lady, starring Audrey Hepburn and Rex Harrison (or “Sexy Rexy”, as my mother and other devoted fans used to call him). It is, it seems, several decades older: it first appeared in the 1938 film version of George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion. That play was notorious for the phrase “Not bloody likely”, the first use of the b***** word on the British stage (how times have changed!), and the film retained it, thereby becoming the first film in which it appeared. The film spawned a stage play (1956) which begat My Fair Lady (1964).

It has, of course, no connection with the realities of Spanish hydrology. Instead, it is an elocution exercise – one that even today some pronunciation Nazis might approve of. Being a nineteenth-century cockney, Eliza Doolittle, the heroine of both play and musical, habitually made rain sound like the river Rhine, and thus, by not using the standard or prestige pronunciation, immediately identified herself as socially suspect. “The rain in Spain stays mainly in the plain” was the remedial drill imposed on her by her mentor, Professor Higgins – or, as she would call him, ’Iggins.

Generally misquoted

It’s interesting that most people in the small sample I’ve got from the poll on this blog, and from Twitter, think of the phrase as “The rain in Spanish falls mainly on the plain.” The change is logical. What does rain generally do? It falls. And where does it fall? On (or onto) something. The changes to the original show speakers amending it to fit their knowledge of English. In that way, they are rather like eggcorns.

This earwormy phrase has been translated into languages as disparate as Estonian, Icelandic, and Farsi, and many others besides. Translating the English word for word into another language has scant chance of producing anything remotely catchy, so each language makes use of its own rhythmic and rhyming resources.

Thus, the Danish version translates back into English as “A snail on the road is a sign of rain in Spain”, the Italian as “The frog in Spain croaks in the country”, while the Portuguese completely removes any mention of Spain: “Behind the train, the troops come trotting” [1]. (Even from the English, you can see that words beginning with tr are what holds it together.)

If you are enjoying this blog, and finding it useful or interesting, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column, above the Twitter feed) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging semi-(ir)regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

Spanish has played with it in at least three versions, two of which include the word for “rain”. It should be easy to work out what that is.

1 “La lluvia en Sevilla es una pura maravilla.”

2 “El juez jugó en Jerez al ajedrez.”

3 “La lluvia en España bellos valles baña.”

Versions 1 and 3, rhyme, as you’ll hear if you say them out loud. They also contain the double ll, which is nowadays generally pronounced similarly to the English y of yes, or, in some parts of Latin America, like the j of judge.

So, rewriting the words with double ll in 1) to show their pronunciation gives us something very approximately like yoovia, seviya, and maraviya.

Verson 2 is a bit of a tongue-twister (un trabalenguas) for those whose mother tongue isn’t Spanish. It translates as “The judge played chess in Jerez”, Jerez being, incidentally, the city that gave English the word sherry.

Version 3 (“The rain in Spain bathes beautiful valleys”) includes the word bello. Unlike Italian bello, which is commonly used in everyday language, Spanish bello is rather more refined and literary. The everyday word to say that something is beautiful is hermoso.

So, where does the real rain in Spain fall? As Andrew Eames memorably put it: “The rain in Spain doesn’t really fall upon the plain at all; on the contrary, it favours the country’s rocky, steep northwestern corner, where Iberia headbutts the Atlantic. Galicia, in fact.” [2]

[1]

Dansk: En snegl på vejen er tegn på regn i Spanien

italiano La rana in Spagna gracida in campagna

português Atrás do trem as tropas vêm trotando

[2]

Something Different for the Weekend, p. 143: Bradt Travel Guides, Chalfont St Peter, England.

Filed under: Meaning of words, Spanish, Word origins Tagged: My Fair Lady

The rain in Spain … mainly… ; What does it mean and where’s it from?

Everyone knows the saying “the rain in Spain…”, but where does it come from and what does it mean?

Let’s get one thing straight, first: the exact original wording of this phrase that has taken root so strongly in English. Is it:

Take Our Poll

I had always assumed that it came from the 1964 film of the musical My Fair Lady, starring Audrey Hepburn and Rex Harrison (or “Sexy Rexy”, as my mother and other devoted fans used to call him). It is, it seems, several decades older: it first appeared in the 1938 film version of George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion. That play was notorious for the phrase “Not bloody likely”, the first use of the b***** word on the British stage (how times have changed!), and the film retained it, thereby becoming the first film in which it appeared. The film spawned a stage play (1956) which begat My Fair Lady (1964).

It has, of course, no connection with the realities of Spanish hydrology. Instead, it is an elocution exercise – one that even today some pronunciation Nazis might approve of. Being a nineteenth-century cockney, Eliza Doolittle, the heroine of both play and musical, habitually made rain sound like the river Rhine, and thus, by not using the standard or prestige pronunciation, immediately identified herself as socially suspect. “The rain in Spain stays mainly in the plain” was the remedial drill imposed on her by her mentor, Professor Higgins – or, as she would call him, ’Iggins.

This earwormy phrase has been translated into languages as disparate as Estonian, Icelandic, and Farsi, and many others besides. Translating the English word for word into another language has scant chance of producing anything remotely catchy, so each language makes use of its own rhythmic and rhyming resources.

Thus, the Danish version translates back into English as “A snail on the road is a sign of rain in Spain”, the Italian as “The frog in Spain croaks in the country”, while the Portuguese completely removes any mention of Spain: “Behind the train, the troops come trotting” [1]. (Even from the English, you can see that words beginning with tr are what holds it together.)

If you are enjoying this blog, and finding it useful or interesting, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column, above the Twitter feed) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging semi-(ir)regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

Spanish has played with it in at least three versions, two of which include the word for “rain”. It should be easy to work out what that is.

1 “La lluvia en Sevilla es una pura maravilla.”

2 “El juez jugó en Jerez al ajedrez.”

3 “La lluvia en España bellos valles baña.”

Versions 1 and 3, rhyme, as you’ll hear if you say them out loud. They also contain the double ll, which is nowadays generally pronounced similarly to the English y of yes, or, in some parts of Latin America, like the j of judge.

So rewriting the words with double ll in 1) to show their pronunciation gives us something very approximately like yoovia, seviya, and maraviya.

Verson 2 is a bit of a tongue-twister (un trabalenguas) for those whose mother tongue isn’t Spanish. It translates as “The judge played chess in Jerez”, Jerez being, incidentally, the city that gave English the word sherry.

Version 3 (“The rain in Spain bathes beautiful valleys”) includes the word bello. Unlike Italian bello, which is commonly used in everyday language, Spanish bello is rather more refined and literary. The everyday word to say that something is beautiful is hermoso.

So, where does the real rain in Spain fall? As Andrew Eames memorably put it: “The rain in Spain doesn’t really fall upon the plain at all; on the contrary, it favours the country’s rocky, steep northwestern corner, where Iberia headbutts the Atlantic. Galicia, in fact.” [2]

Dansk: En snegl på vejen er tegn på regn i Spanien

italiano La rana in Spagna gracida in campagna

português Atrás do trem as tropas vêm trotando

Something Different for the Weekend, p. 143: Bradt Travel Guides, Chalfont St Peter, England.

Filed under: Meaning of words, Spanish, Word origins Tagged: My Fair Lady