Jeremy Butterfield's Blog, page 26

July 31, 2015

A “swarm of people”, i.e. migrants. Politically incorrect or harmless metaphor?

Is an orderly queue a swarm?

The brouhaha over the Prime Minister’s use of the phrase “swarm of people” referring to migrants has, understandably, been intense. (A fuller record of the context in which he said it is at the end of the blog). Notably, Harriet Harman stated that “he should remember he is talking about people and not insects”, while Jeremy Corbyn described his language as “inflammatory, incendiary and unbecoming of a prime minister.”

Standing back a little from this highly charged debate over a deplorable situation for all concerned (above all, please remember, for the people trying to reach the UK, but also for the people of Calais, lorry drivers, holiday makers, etc., etc.), I said to myself: hang on, isn’t Harriet Harman’s comment rather literalistic? It is, surely, perfectly possible to refer to groups of people as swarms. (Jump to the Conclusion, if you want to skip the lexicography bit.)

What can dictionaries tell us?

For what it’s worth, dictionaries certainly include this meaning.

Collins (3rd meaning): “a throng or mass, esp when moving or in turmoil”;

Merrian-Webster does not separate the human swarm from others, but has as meaning 2 a: “a large number of animate or inanimate things massed together and usually in motion: throng swarms of sightseers a swarm of locusts a swarm of meteors”;

Oxford online (meaning 1.2) has: “(a swarm/swarms of) A large number of people or things: a swarm of journalists“.

It is interesting that none of those three comments on the connotations of the word, as lexicographers often do, with labels such as “offensive” or “derogatory”.

In fact, only the OED does so: “A very large or dense body or collection; a crowd, throng, multitude. (Often contemptuous.)”

But the first meaning all of them give can be summarized either as “a very large number of insects moving together” (Merriam-Webster) or (Oxford online) “A large number of honeybees that leave a hive en masse with a newly fertilized queen in order to establish a new colony”.

(The bee meaning goes back at least to 725, and the word is echoed in Modern German, Dutch, Swedish, etc., as well as being probably related to Sanskrit.)

A slumbering metaphor?

The application to people can be considered a metaphor, which raises the question of whether that metaphor is alive, dormant, or dead. The current debate suggests that it was dormant, but has been rudely reawakened.

Connotations

I think it’s fair to say that the connotations (semantic features) of the word are necessarily:

a large group;

a compact group;

a group in energetic motion;

(perhaps optionally) confused motion; and

the group is undesirable.

Referring to people, is it inevitably pejorative?

Let’s look briefly at its history. That use, according to the OED, dates back to an early fifteenth-century poem (the Kingis Quair, the King’s Book) by James 1  of Scotland (himself an enforced “migrant” in an English prison) in one of the stanzas describing people on Fortune’s wheel:

of Scotland (himself an enforced “migrant” in an English prison) in one of the stanzas describing people on Fortune’s wheel:

And ever I sawe a new swarm abound

That thoght to clymbe upward upon the quhele (wheel)

In stede of thame that myght no langer rele. (spin)

While that particular use seems neutral – he is just referring to masses of people – more than half the subsequent OED citations have a negative tinge (many in theological contexts): swarm(s) of Antichrist, bishops, false ministers, sects.

What can Google and corpus tell us?

If you search in Google Ngrams (a ginormous database of books published between 1800 and 2012) for the string swarm of followed by a wildcard, the string swarm of these is the seventh most common, after different insects. My survey (15 citations, with some duplication) of what follows “these” for 1800-1810, shows that all three cases (which include Gibbon and Goldsmith) mentioning people are negative, e.g. “England is already, unfortunately for native talent, cursed with a swarm of these exotic ‘artists’.” This tends to confirm what was said above about the OED citations: the negative association of the word when applied to groups of people is of long standing.

Furthermore, most of the insects referred to in Ngrams as a swarm are a nuisance, or undesirable; locusts, flies, ants, gnats (but Ngrams only gives you the first ten collocations.)

One question that I asked myself was whether you could refer to “desirable” or beautiful insects as a swarm and the Oxford English Corpus suggests that you can: dragonflies, fireflies, grasshoppers and even butterflies.

However, the first human group in that same list is paparazzi – almost universally regarded as a pest.

It all depends on the context

The OEC data shows that swarm of (within a window of three to the right) collocates with groups of humans: people; angry youth/bloggers/media; reporters.

Swarm of people

Of the 32 examples of swarm of people from the OEC about half seem to be neutral, as far as one can gather from the limited context available: for example (from a news site): “Whistles and drums will echo through Lancaster as a swarm of people parade through the streets in a bid to save a nursery.”

That contrasts with contexts such as “Suddenly Bradson was centre of a swarm of people , all staring at him , pressing close , addressing him in a language he could not comprehend“, where the swarm is clearly perceived as threatening.

Looking at the plural swarms of people in Google Ngrams suggests a similar contrast, even among the earliest citations it throws up. On the one hand, there is Addison’s neutral “… trade and merchandise, that had filled the Thames with such crowds of ships, and covered the shore with such swarms of people” (The Freeholder, Vol. 4, No. 47).

On the other, there is Malthus’s “... in the midst of that mighty hive which had sent out such swarms of people, as to keep the Roman world in perpetual dread, …” (An Essay on the Principle of Population, Book 1, ch. 6, 1798).

Other swarms

While “swarm of people” can arguably merely highlight the numbers involved, the other kinds of swarm mentioned — angry youth, etc. — are all unfavourable.

Another collocation is with who, where 12 of the 30 collocations seem neutral, but the remainder are negative, ranging from mere Marxists to “a swarm of those bloodsuckers who are always on the watch for public calamities” and “a swarm of crusading bureaucrats who relentlessly raid our private lives“.

If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column, above the Twitter feed) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

Conclusion

The overriding conclusion must be that when referring to people, swarm is highly likely to be negative (or to have a negative “semantic prosody” as some linguists have termed it, though the concept has been challenged).

As confirmation of that, if one looks at the synonyms dictionaries give for swarm, several are as unfavourable as it, or more so (horde, gang, mob, etc.).

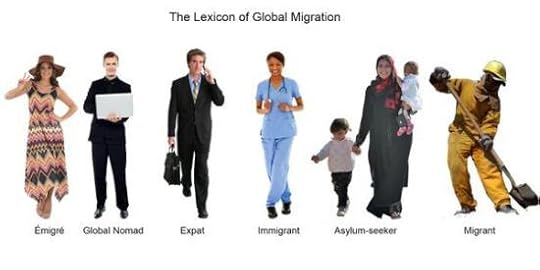

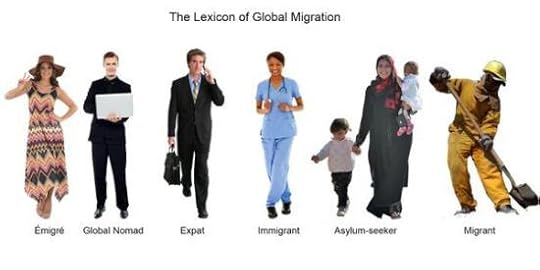

The combination swarm of people when referring to migrants is particularly unfortunate, since the latter is in any case a highly charged and politicized word and concept. (As the Washington Post has commented, to be described as a migrant immediately puts you on the bottom rung of a hierarchy of status and desirability. Aren’t so-called “economic migrants” as much refugees as political refugees?)

What would have been wrong with the neutral “large groups”?

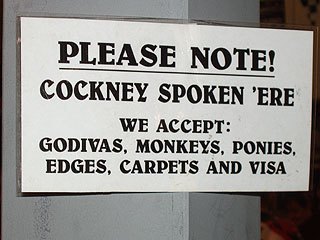

Image courtesy of Karl Sharro, tweeting as @KarlreMarks

On an uncharitable reading, by using the phrase “swarm of people”, Mr Cameron was either giving unwitting vent to his inner xenophobe (though that seems unlikely for such a fluent, soundbite politician) and/or playing to the gallery, by reinforcing the narrative of Britain as an island of prosperity besieged by trillions of invading would-be scroungers.

(The fact that one of these desperate people was recently killed in the attempt, and that others repeatedly suffer severe hand injuries is ignored.

And it seems to me that people who have the courage to make the incredibly dangerous and draining journey from wherever they set out are displaying a degree of courage and determination that is admirable.

Here is a sober analysis of the numbers involved, showing how few Britain has accepted compared to other EU countries).

On the other hand, his using the word could be justified by the neutral use of swarm referring to people as previously detailed. That fits in with Downing Street’s justification that “The point he was making is that there are tens of thousands of people moving across Africa and trying to get to Europe.”

From that perspective, it would not be unreasonable to argue that he was merely using a standard, colourful collocation of English, which his critics and the thought police have pounced on in order to make political capital.

Against that, it can be argued that because the larger verbal contexts in which swarm of tends to occur are so often negative, people are attuned to that negativity, and will therefore tinge supposedly neutral contexts with that negativity. Furthermore, since the larger, social context is the whole British debate about migrants, which is generally negative, it is hard to disagree with critics of what Cameron said.

Mr Cameron’s words

(From the Guardian, 30 July 2015) Speaking to ITV News in Vietnam, Cameron vowed to do more to protect Britain’s borders. He said: “We have to deal with the problem at source and that is stopping so many people from travelling across the Mediterranean in search of a better life. That means trying to stabilise the countries from which they come, it also means breaking the link between travelling and getting the right to stay in Europe.

This is very testing, I accept that, because you have got a swarm of people coming across the Mediterranean seeking a better life, wanting to come to Britain because Britain has got jobs, it’s got a growing economy, it’s an incredible place to live. But we need to protect our borders by working hand in glove with our neighbours, the French, and that is exactly what we are doing.”

Filed under: Meaning of words, Topical, Word origins

A swarm of migrants. Politically incorrect or harmless metaphor?

Is an orderly queue a swarm?

The brouhaha over the Prime Minister’s use of the phrase “swarm of migrants” has, understandably, been intense. (A fuller record of the context in which he said it is at the end of the blog). Notably, Harriet Harman stated that “he should remember he is talking about people and not insects”, while Jeremy Corbyn described his language as “inflammatory, incendiary and unbecoming of a prime minister.”

Standing back a little from this highly charged debate over a deplorable situation for all concerned (above all, please remember, for the people trying to reach the UK, but also for the people of Calais, lorry drivers, holiday makers, etc., etc.), I said to myself: hang on, isn’t Harriet Harman’s comment rather literalistic? It is, surely, perfectly possible to refer to groups of people as swarms. (Jump to the Conclusion, if you want to skip the lexicography bit.)

What can dictionaries tell us?

For what it’s worth, dictionaries certainly include this meaning.

Collins (3rd meaning): “a throng or mass, esp when moving or in turmoil”;

Merrian-Webster does not separate the human swarm from others, but has as meaning 2 a: “a large number of animate or inanimate things massed together and usually in motion: throng swarms of sightseers a swarm of locusts a swarm of meteors”;

Oxford online (meaning 1.2) has: “(a swarm/swarms of) A large number of people or things: a swarm of journalists“.

It is interesting that none of those three comments on the connotations of the word, as lexicographers often do, with labels such as “offensive” or “derogatory”.

In fact, only the OED does so: “A very large or dense body or collection; a crowd, throng, multitude. (Often contemptuous.)”

But the first meaning all of them give can be summarized either as “a very large number of insects moving together” (Merriam-Webster) or (Oxford online) “A large number of honeybees that leave a hive en masse with a newly fertilized queen in order to establish a new colony”.

(The bee meaning goes back at least to 725, and the word is echoed in Modern German, Dutch, Swedish, etc., as well as being probably related to Sanskrit.)

A slumbering metaphor?

The application to people can be considered a metaphor, which raises the question of whether that metaphor is alive, dormant, or dead. The current debate suggests that it was dormant, but has been rudely reawakened.

Connotations

I think it’s fair to say that the connotations (semantic features) of the word are necessarily:

a large group;

a compact group;

a group in energetic motion;

(perhaps optionally) confused motion; and

the group is undesirable.

Referring to people, is it inevitably pejorative?

Let’s look briefly at its history. That use, according to the OED, dates back to an early fifteenth-century poem (the Kingis Quair, the King’s Book) by James 1  of Scotland (himself an enforced “migrant” in an English prison) in one of the stanzas describing people on Fortune’s wheel:

of Scotland (himself an enforced “migrant” in an English prison) in one of the stanzas describing people on Fortune’s wheel:

And ever I sawe a new swarm abound

That thoght to clymbe upward upon the quhele (wheel)

In stede of thame that myght no langer rele. (spin)

While that particular use seems neutral – he is just referring to masses of people – more than half the subsequent OED citations have a negative tinge (many in theological contexts): swarm(s) of Antichrist, bishops, false ministers, sects.

What can Google and corpus tell us?

If you search in Google Ngrams (a ginormous database of books published between 1800 and 2012) for the string swarm of followed by a wildcard, the string swarm of these is the seventh most common, after different insects. My survey (15 citations, with some duplication) of what follows “these” for 1800-1810, shows that all three cases (which include Gibbon and Goldsmith) mentioning people are negative, e.g. “England is already, unfortunately for native talent, cursed with a swarm of these exotic ‘artists’.” This tends to confirm what was said above about the OED citations: the negative association of the word when applied to people is of long standing.

Furthermore, most of the insects referred to in Ngrams as a swarm are a nuisance, or undesirable; locusts, flies, ants, gnats (but Ngrams only gives you the first ten collocations.)

One question that I asked myself was whether you could refer to “desirable” or beautiful insects as a swarm and the Oxford English Corpus suggests that you can: dragonflies, fireflies, grasshoppers and even butterflies.

However, the first human group in that same list is paparazzi – almost universally regarded as a pest.

It all depends on the context

The OEC data shows that swarm of (within a window of three to the right) collocates with groups of humans: people; angry youth/bloggers/media; reporters.

While “swarm of people” arguably merely highlights the numbers involved, the others mentioned are all unfavourable.

Another collocation is with who, where 12 of the 30 collocations seem neutral, but the remainder are negative, ranging from mere Marxists to “a swarm of those bloodsuckers who are always on the watch for public calamities” and “a swarm of crusading bureaucrats who relentlessly raid our private lives“.

If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column, above the Twitter feed) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

Conclusion

The overriding conclusion must be that when referring to people, swarm is highly likely to be negative (or to have a negative “semantic prosody” as some linguists have termed it, though the concept has been challenged).

As confirmation of that, if one looks at the synonyms dictionaries give for swarm, several are as unfavourable as it, or more so (horde, gang, mob, etc.).

The combination of swarm with migrant is particularly unfortunate, since the latter is in any case a highly charged and politicized word. (As the Washington Post has commented, to be described as a migrant immediately puts you on the bottom rung of a hierarchy of status and desirability.)

What would have been wrong with the more or less neutral “large groups”? Or not mentioning numbers and just referring to “migrants”, tainted though that word itself? (Aren’t so-called “economic migrants” as much refugees as political refugees?)

Image courtesy of Karl Sharro, tweeting as @KarlreMarks

Clearly, by using the phrase “swarm of migrants”, Mr Cameron was either giving unwitting vent to his inner xenophobe (though that seems unlikely for such a glib, soundbite politician) and/or playing to the gallery, by reinforcing the narrative of Britain as an island of prosperity besieged by trillions of invading would-be scroungers.

The fact that one of these desperate people was recently killed in the attempt, and that others repeatedly suffer severe hand injuries is ignored.

And it seems to me that people who have the courage to make the incredibly dangerous and draining journey from wherever they set out are displaying a degree of courage and determination that is admirable.

(Here is a sober analysis of the numbers involved, showing how few Britain has accepted compared to other EU countries).

Mr Cameron’s words

(From the Guardian, 30 July 2015) Speaking to ITV News in Vietnam, Cameron vowed to do more to protect Britain’s borders. He said: “We have to deal with the problem at source and that is stopping so many people from travelling across the Mediterranean in search of a better life. That means trying to stabilise the countries from which they come, it also means breaking the link between travelling and getting the right to stay in Europe.

This is very testing, I accept that, because you have got a swarm of people coming across the Mediterranean seeking a better life, wanting to come to Britain because Britain has got jobs, it’s got a growing economy, it’s an incredible place to live. But we need to protect our borders by working hand in glove with our neighbours, the French, and that is exactly what we are doing.”

Filed under: Meaning of words, Topical, Word origins

June 30, 2015

‘To have another think coming’ or ‘another thing coming’?

The other day, the chirruping bird alerted me to an issue that I hadn’t previously given much thought to. Is it to have (got) another think coming or another thing?

A tweet for English learners referred to the idiom as ‘another thing coming’, and pointed people to a Judas Priest song titled You’ve Got Another Thing Comin’, the second verse of which goes like this:

If you think I’ll sit around as the world goes by

You’re thinkin’ like a fool cause it’s a case of do or die

Out there is a fortune waiting to be had

If you think I’ll let you go you’re mad

You’ve got another thing comin’

You’ve got another thing comin’

Conversely, a British English speaker, sought to correct a tweet by a British politician that contained the wording ‘another thing coming’.

Metalheads will already know the song. If you don’t, and you want your ear wax blown out, or wish to indulge in some private moshing or headbanging, you can listen to the original version here:

If you prefer a more mellow approach, here’s the link to veteran smoothie Pat Boone’s version — which kinda proves that heavy metal is non-transferable.

The ‘thing’ spelling is repeated, for example, in:

“If they think I’m going to be a Labrador and roll over they’ve got another thing coming,” he says of the [Conservative] party.

Daily Telegraph (British), 2013.

But the ‘think’ spelling is used here:

In the first instance it sounds good, but if people think those big international companies are here for the benefit of New Zealand, they really have another think coming.

New Zealand Parliamentary debates, 2005.

Since both quotations transcribe what people said, it is impossible to know what form of the phrase the original speakers had in mind.

Stewie says ‘another thing’, and he’s a bit of a stickler.

Quick facts

Speakers use both another thing coming and another think coming. and both are part of World English, although only a few varieties of English use either phrase frequently.

Which version you use may depend partly on which variety of English you speak, and which variant you have been most exposed to—and, possibly, on how much of a ‘prescriptivist’ you are.

Whichever version you use, someone somewhere may consider it wrong, but British speakers are probably more likely to consider another thing coming wrong.

The Oxford English Corpus (OEC) and the Global Web-Based English Corpus (GloWbE) both show another thing coming to be more frequent in data for all varieties of English taken as a whole.

In US English, data suggests a marked preference for another thing. In British English, the two forms compete more evenly.

Other data on frequency is slightly contradictory (see further details at end of blog).

All the above suggests to me that, if you’re editing someone else’s work and feel tempted to change this phrase, you might want to have a bit of a think about it.

If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column, above the Twitter feed) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

Where is the phrase from?

In its original form, according to the OED, it was to have another think coming, and it is American in origin:

Conroy lives in Troy and thinks he is a corning fighter. This gentleman has another think coming.

Syracuse (N.Y.) Standard, 21 May, 1898.

But note that Language Log has a citation from a year earlier, from the Washington Post of April 29, 1897, in the title of an article, and in inverted commas.

It’s worth mentioning that think as a noun is merely a nineteenth-century ‘invention’ (1838), despite the antiquity of the verb (Old English). From discussion in the blogosphere, it seems that some people find it rather odd for think to be used as a noun, which would reinforce their use of thing. (It turns out from figures given below that this noun use of think is indeed rare in US and Canadian English.)

The OED’s first example of another thing coming is from only a few years later, from a book published in New York in 1906:

Now if we should try and think up some one person who is satisfied with the existing order of things.., we would most likely have thought that we should find him in the editor of the Wall Street Journal. But if we did, then we have another thing [1904 Wilshire’s Mag. think] coming.

Wilshire Editorials, G. Wilshire.

(Notice how the OED shows the 1904 rendition of the phrase with ‘think’.)

Is anyone bovvered?

Online searches suggest that, rather than caring deeply about which version is correct, many people are simply puzzled when they come across whichever of the two alternatives is not part of their idiolect.

For example, in my idiolect think is correct, and makes sense meaningwise: it means ‘to think again, to change one’s mind, to have second thoughts’, and that meaning is primed for me by the fact that the phrase often follows a clause introduced by ‘if you/he/she, etc. think(s), e.g., And if you think I ‘m letting you get your hands on my crystals you’ve got another think coming.

Moreover, there are analogous uses of think as a noun—to have a think about something, after a bit of a think, and so on.

However, this noun use of think seems to be rather more common in British and Australian English than in American English, according to the OEC data. GloWbE confirms this: of its 440 examples, 370 are from British/Australian/New Zealand/Irish English, and only 30 from US/Canadian.

Similarly, another thing coming makes perfect sense to the people who use it. In that form, the phrase can be interpreted along the lines of ‘something different from what you expect is going to happen to you’. This makes sense too, since both versions of the phrase are a sort of warning, if not a veiled threat.

And while sentences containing another thing coming also often start with ‘if you/he/she, etc. think(s), that doesn’t appear to deter people from using the thing spelling.

Here is an interpretation from a site on which users raise questions about English usage (englishstackexchange.com):

I also grew up with another thing and I still don’t believe think is original. My thoughts are along the following lines. Ehhmm, Ready?? Lots of people, when laying out the list of arguments for their cause will follow that list with, “… And another thing… ” and go on to list more arguments. This was the origin of the phrase in my mind. Think, I reasoned, was then just someone’s clever pun.

And from comments on a Guardian blog on this topic, it is clear that many people are absolutely adamant about which version is ‘correct’. (There is the usual split in comments between the ‘English is going to the dogs’ and the ‘variation is a fact of language’ brigades.)

Why the alternation?

In simple terms, because the sound at the end of think and the beginning of coming is identical or similar, i.e. /θɪŋk/ and /k-/, it is hardly surprising that word boundaries have been re-analysed as sort of /θɪŋ/ /k-/, which produces another thing coming.

Such re-drawings of word boundaries have historically given English words such as adder, apron, nickname, and umpire.

In practice, the phonetic picture is rather more complex, and it is virtually impossible to tell if a speaker is saying ‘think’ or ‘thing’. (For an exhaustive and illuminating phonetic description of what exactly is going on when someone says the phrase, complete with audio clips, see this Language Log blog.)

What do dictionaries and style guides say?

Neither the Merriam-Webster Concise Dictionary of English Usage nor The Cambridge Guide to English Usage covers it. Burchfield included it in his 1996 edition of Fowler’s Modern English Usage, and I have modified it in my edition. The OED describes to have another thing coming as ‘arising from misapprehension’ of “another think coming”’, but the Oxford Dictionary Online (which is not the OED, but a shorter, more modern dictionary) has no note, and does not include to have another thing coming; nor do Merriam-Webster online, the Collins online dictionary, and the Macmillan dictionary.

Facts & figures

Perhaps dictionaries should look at the issue again; no doubt in time they will.

Google

A simple Google for ‘another thing/think coming’ shows them practically neck and neck. However, if you exclude ‘Judas Tree’ from each search, the balance shifts towards ‘another think coming’: (roughly 170 million vs 71 million.) I’m dubious, however, about how useful such a simple search is.

OEC

(February 2014 release; 2.14 billion words)

‘another thing’ = 124

US = 56 (45%)

Brit. = 28 (22%)

unknown = 15 (12.1%)

Can. = 7 (5.6%)

Oz = 6 (4.8%)

Remainder (India, Ireland, etc.) = 12

‘another think’ = 94

Brit. = 35 (37%)

US = 29 (30%)

unknown = 11 (11.7%)

NZ = 9 (9.6%)

Oz = 2 (2.1%)

Can. = 1 (1.1%)

Remainder (South Africa, India, etc.) = 10

As regards British English vs US English, in the OEC both variants are used in both varieties, but for American English the ratio of think:thing is 29:56, while for British English it is 35:28.

GloWbE

(1.9 billion words)

‘another thing’ = 119

US = 33 (27.7%%)

Brit. = 32 (26.9%%)

Irish = 12 (10.1%)

Oz = 8 (6.7%%)

Philippines = 5 (4.2%)

Remainder (15 countries) = 29

‘another think’ = 66

Brit. = 26 (39.4%)

US = 18 (27.3%)

Nigeria = 4 (6.1%)

Philippines = 3 (4.5%)

Irish = 2 (3%)

Oz = 1 (1.5%)

Remainder (14 countries) = 12

Corpus of Contemporary American

(450 million words; 1990–2012

another thing:another think 20:23

Google Ngrams

Data here suggests that the exact string ‘got another think coming’ is still more frequent, but that ‘got another thing coming’ has been increasing since the 1960s, while ‘think’ has been declining since the 1980s. The picture is similar for English data as a whole, and for US and British English data individually.

Filed under: Advice for writers, Confusable words, Grammar, Meaning of words, Spelling, Word origins

June 1, 2015

Greengages and other words named after people

We probably all know that the wellies we might wear to go on walks through muddy fields are named after the Duke of Wellington, the “Iron Duke”. Perhaps less well known is the link between the mac – in British English, at any rate – that we might also wear and its inventor, the deviser of the waterproof cloth from which macs are made, Charles Macintosh (1766–1843), the Scottish inventor who patented the cloth. Many units of scientific measurement, both everyday and more specialized, are named after their discoverers: the Italian physicist Count Alessandro Volta gave us volts, the Scottish engineer James Watt gave us, er, … watts, and the Belfast-born Lord Kelvin gave his name to the units in which absolute temperature is measured.

Such words, derived from someone’s name, are technically called eponyms, a word created in the 19th century from the Greek epōnumos “given as a name, giving one’s name to someone or something”, from epi “upon” + onoma “name” (ἐπώνυμος; ἐπί + ὄνομα, Aeolic ὄνυμα name). The same Greek word for “name” has given English also anonymous and synonym(ous). And when people refer to the eponymous hero of such and such a novel, e.g. Fielding’s Tom Jones, they mean that the title of the novel is its protagonist’s name. In modern Greek, επώνυμο (eponimo) is the word for “surname”.

greengage – This is a type of greenish or yellow-green plum, beloved of jam-makers. As the OED defines it, “The small oval fruit of a cultivated variety of plum, Prunus domestica subsp. italica, which has yellow to green skin and very sweet juicy flesh, and is used for eating and for making desserts and preserves”.

No less an authority than the BBC Gardeners’ World praises greengages lip-smackingly:

If your standard Victoria plum is good plonk, then a perfectly ripe greengage is a fine wine in a vintage year.

The word apparently combines the colour of the fruit with the name of the botanist and cricket enthusiast Sir William Gage (1695-1744) who, around 1725, first introduced it to Britain.

If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column, above the Twitter feed) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

The first citation in the OED of the fruit being called “green-gage” (hyphenated) is from 1718, in the work of the cleric John Laurence, a sort of Monty Don with a dog collar who, to judge by his literary output, must have spent more time tending his garden than writing sermons.

The Clergyman’s Recreation, Shewing the Pleasure and Profit of the Art of Gardening (1714) was his first venture into publishing. His third book in this genre, The Fruit-Garden Kalendar (1718), contains the relevant citation:

We are also now presented with some of the most excellent Plums, viz. the Blue and White Perdigrans, the Sheen, or Fotheringa …, the Green Gage, the Muscle, and the Orleance.

(A plum called a Muscle? No wonder it didn’t catch on.)

It was not until some time before 1768, again according to the OED, that the connection between Sir William and the fruit was made explicit, in an 1843 book by Lewis Weston Dillwyn, cataloguing the plants of an earlier horticulturist: Hortus Collinsonianus: an account of the plants cultivated by the late Peter Collinson, Esq., F.R.S., arranged alphabetically according to their modern names, from the catalogue of his garden,… :

I was on a visit to Sir William Gage..; he told me that..in compliment to him the Plum was called the Green Gage; this was about the year 1725.

A fruit fit for a queen

The common or garden Victoria plum, damned with faint praise by the Gardeners’ World horticultural savants, was named after Queen Victoria. But it is not the only variety of plum with a royal connection.

Queen Claude, portrayed 30 years after her death in Catherine de Médicis’ Book of Hours

In French a greengage is une reine-Claude (Queen Claude) after Claude (1499-1524), the wife of Francis 1 of France

According to the OED, “it was common in early modern France for noteworthy varieties of fruit to be named in honour of queens and other members of the nobility.”

The French name was also borrowed by other European languages: Dutch reine-claude (1763), German Reineclaude, now usually Germanized as die Reneklode (17th cent.), Swedish renklo (1835; earlier as †reine claude (1770), †reinklo (1825)), Danish reineclaude (1802 as †ræneklode; also reneklode), and Italian susina Regina Claudia “Queen Claudia Plum”.

All of which makes greengage a sort of multilingual eponym.

At the entry for greengage, the OED cross-refers to Reine Claude, which it defines as “A cultivated variety of plum; esp. the greengage.”

That word first appears in John Evelyn (the diarist)’s Kalendarium hortense: or, The gard’ners almanac · 8th ed., with … additions., 1691.

A Guardian quotation from 20 January, 1971 unites the two names:

It is the land of … the honeyed Reine-Claude greengages.

The long-established British nursery Thomson & Morgan sells “greengages Reine Claude”.

And a translated French history of food from (1992) has this:

Greengages are called after the eighteenth century Sir William Gage, who brought the French Reine-Claude over to England, where it acquired a new English name.

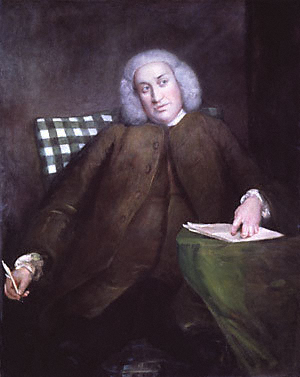

Dr Johnson wondering what apophthegm will adequately convey his contempt for froggy words.

Whether the greengage and the reine-Claude are now exactly the same only a horticulturist could tell me. (The Thomson and Morgan catalogue entry suggests to me that greengage is generic and reine-Claude specific.) I am left wondering if Sir William changed the name because it was easier to pronounce. Or was it because of anti-French sentiment? We’ll probably never know.

But the notion brings to my mind Dr Johnson’s disparaging remarks in his 1755 Dictionary about certain French words being used in English, e.g. “ruse: a French word neither elegant nor necessary”.

For whatever reason, he found the word’s “trick” meaning objectionable, despite its going back to the sixteenth century and despite his using a quotation from the eminently respectable John Ray’s 1722 The Wisdom of God Manifested in the Works of the Creation.

Apples and pears and greengages

Back in the twentieth century, greengage became part of rhyming slang (though I don’t know how actively used it now is). The OED gives it two meanings: “the stage” (1931) and, as the plural greengages, “wages” (1932), and includes a quote from Orwell’s Collected Essays (written before 1950), the fuller text of which is as follows:

Rhyming slang. I thought this was extinct, but it is far from it. The hop-pickers used these expressions freely: A dig in the grave, meaning a shave. The hot cross bun meaning the sun. Greengages, meaning wages. They also use the abbreviated rhyming slang, e.g. ‘Use your twopenny’ for ‘Use your head.’ This is arrived at like this: Head, loaf of bread, loaf, twopenny loaf, twopenny.

Hop-pickers at the start of the 1948 picking season, Kent. Note the age range.

Hop-pickers were often East End families (i.e. from the home of Cockney) who mass-migrated to Kent for the hop-picking season.

Filed under: Word origins,

April 14, 2015

Paparazzi and other words named after people

We probably all know that the wellies we might wear to go on walks through muddy fields are named after the Duke of Wellington, the “Iron Duke”. Perhaps less well known is the link between the mac ��� in British English, at any rate ��� that we might also wear and its inventor, the deviser of the waterproof cloth from which macs are made, Charles Macintosh (1766���1843), the Scottish inventor who patented the cloth. Many units of scientific measurement, both everyday and more specialized, are named after their discoverers: the Italian physicist Count Alessandro Volta gave us volts, the Scottish engineer James Watt gave us, er, ��� watts, and the British Lord Kelvin gave his name to the units in which absolute temperature is measured.

Such words, derived from someone���s name, are technically called eponyms, a word created in the 19th century from the Greek ep��numos “given as a name, giving one’s name to someone or something”, from epi “upon” + onoma “name” (�����������������; ������� + �����������, Aeolic ����������� name). The same Greek word for ���name��� has given English also anonymous and synonym(ous). And when people refer to the eponymous hero of such and such a novel, e.g. Fielding’s��Tom Jones, they mean that the title of the novel is its protagonist’s name.

Phwoooar! (That’s enough!–Ed.)

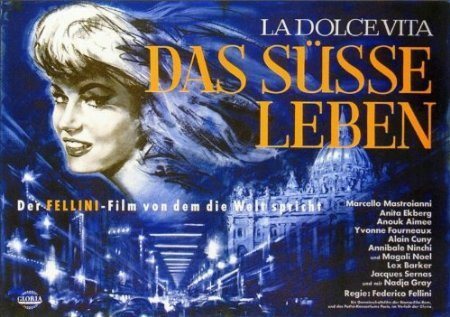

paparazzo�������a freelance photographer who pursues celebrities to take and then sell photographs of them. It may be a bit of a surprise that this word is an eponym; as in the case of knickers, the character who gave us the name is fictional. In Italian film director Federico Fellini���s classic 1959 La Dolce Vita, Paparazzo is the surname of a photographer who works with gossip columnist Marcello Mastroianni. The character is based on a real-life Roman celeb-snapper of the era, a certain Tazio Secchiaroli.

If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column, above the Twitter feed) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

As with some other Italian words (graffiti, spaghetti, panini), English does not always respect (and why should it?) the singular/plural distinction of the original Italian: 1 paparazzo, 2 paparazzi. Because paparazzi generally hunt in packs, the plural form paparazzi is much more frequent than the singular in any case, and is quite often used as a singular, instead of the technically “correct”��paparazzo.

The Scottish guy I met who moved here to be��a paparazzi��has moved elsewhere.

Montreal Mirror, 2004.

He published the photographs – taken by��a paparazzo��who gatecrashed the wedding – to defend the economic interests of his magazine, he added.

Yorkshire Post Today, 2003

��Occasionally paparazzi seems to be interpreted, as far as I can judge, as a collective noun, and accordingly is used with the singular verb agreement obligatory for collective nouns in American English:

I was actually thinking that Michelle Obama will be the one that the paparazzi takes the most pictures of, you know, detailing, you know, her every outfit.

CNN (transcripts), 2008.

Filed under:

Leotards and other words named after people

We probably all know that the wellies we might wear to go on walks through muddy fields are named after the Duke of Wellington, the “Iron Duke”.  Perhaps less well known is the link between the mac ��� in British English, at any rate ��� that we might also wear and its inventor, the deviser of the waterproof cloth from which macs are made, Charles Macintosh (1766���1843), the Scottish inventor who patented the cloth. Many units of scientific measurement, both everyday and more specialized, are named after their discoverers: the Italian physicist Count Alessandro Volta gave us volts, the Scottish engineer James Watt gave us, er, ��� watts, and the British Lord Kelvin gave his name to the units in which absolute temperature is measured.

Perhaps less well known is the link between the mac ��� in British English, at any rate ��� that we might also wear and its inventor, the deviser of the waterproof cloth from which macs are made, Charles Macintosh (1766���1843), the Scottish inventor who patented the cloth. Many units of scientific measurement, both everyday and more specialized, are named after their discoverers: the Italian physicist Count Alessandro Volta gave us volts, the Scottish engineer James Watt gave us, er, ��� watts, and the British Lord Kelvin gave his name to the units in which absolute temperature is measured.

Such words, derived from someone���s name, are technically called eponyms, a word created in the 19th century from the Greek ep��numos “given as a name, giving one’s name to someone or something”, from epi “upon” + onoma “name” (�����������������; ������� + �����������, Aeolic ����������� name). The same Greek word for ���name��� has given English also anonymous and synonym(ous). And when people refer to the eponymous hero of such and such a novel, e.g. Fielding’s Tom Jones, they mean that the title of the novel is its protagonist’s name. In modern Greek, �������������� (eponimo) is the word for “surname”.

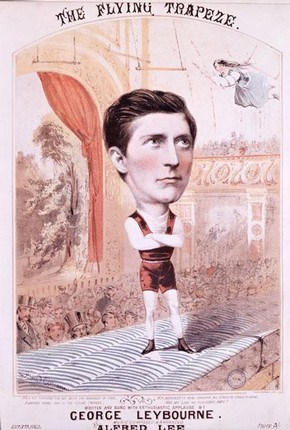

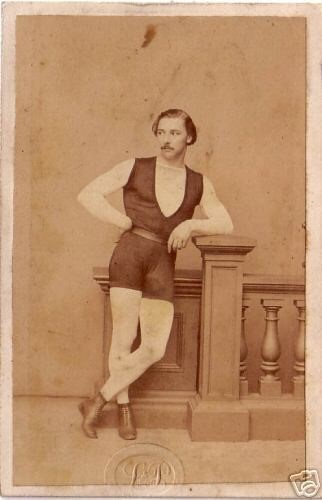

leotard ��� The word for this figure-hugging one-piece garment, made of stretchy materials and donned by ballet dancers for practice and other people doing various forms of exercise, is written without an accent. But if you add the acute accent, you get the name of its inventor, Jules L��otard, a remarkable French acrobat.

Jules contriving to look butch in a fetching miniskirt.

In 1859 ��� ��the same year that his compatriot Blondin crossed the Niagara Falls on a tightrope ��� he performed the world’s first aerial somersault and leapt from trapeze to trapeze. That provided the inspiration for the popular music-hall song That Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze. Sadly, his career was short-lived: he died at the age of twenty-eight in 1870.

The narrator tells the story of his lost love.

Once I was happy, but now I’m forlorn

Like an old coat that is tattered and torn;

Left on this world to fret and to mourn,

Betrayed by a maid in her teens.

The girl that I loved she was handsome;

I tried all I knew her to please

But I could not please her one quarter so well

As the man upon the trapeze.

He’d fly through the air with the greatest of ease,

That daring young man on the flying trapeze.

His movements were graceful, all girls he could please

And my love he purloined away.

Some further verses chronicle how she fell in love with the trapezist and then eloped with him, before …

Some months after this I went to the Hall;

Was greatly surprised to see on the wall

A bill in red letters, which did my heart gall,

That she was appearing with him.

He’d taught her gymnastics and dressed her in tights,

To help him live at his ease,

And made her assume a masculine name,

And now she goes on the trapeze.

She’d fly through the air with the greatest of ease,

You’d think her the man young man on the flying trapeze.

Her movements were graceful, all girls she could please,

And that was the end of my love.

Am I the only one who is puzzled by the hint of sapphism in the last verse? Or is the word “girls” used because to replace it with “men” would be far too saucy?

Anyway, this photo highlights the effect on Victorian sensibilities that Jules L. must have had when he chose not to wear his modesty-preserving miniskirt. “Wardrobe malfunction” hardly does it justice.

I’m really quite pleased with my merguez and pickled lemons.

And here’s a sort of hillbilly version of the song, from the 1934 film It Happened one Night, starring Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert (“together for the first time”!). Note the American pronunciation of “trapeze” at the beginning, with a full /a/ not a schwa.

Filed under: Word origins,

April 13, 2015

Knickers and other words named after people

We probably all know that the wellies we might wear to go on walks through muddy fields are named after the Duke of Wellington, the “Iron Duke”. Perhaps less well known is the link between the mac – in British English, at any rate – that we might also wear and its inventor, the deviser of the waterproof cloth from which macs are made, Charles Macintosh (1766–1843), the Scottish inventor who patented the cloth. Many units of scientific measurement, both everyday and more specialized, are named after their discoverers: the Italian physicist Count Alessandro Volta gave us volts, the Scottish engineer James Watt gave us, er, … watts, and the British Lord Kelvin gave his name to the units in which absolute temperature is measured.

Such words, derived from someone’s name, are technically called eponyms, a word created in the 19th century from the Greek epōnumos “given as a name, giving one’s name to someone or something”, from epi “upon” + onoma “name” (ἐπώνυμος; ἐπί + ὄνομα, Aeolic ὄνυμα name). The same Greek word for “name” has given English also anonymous and synonym(ous). And when people refer to the eponymous hero of such and such a novel, e.g. Fielding’s Tom Jones, they mean that the title of the novel is its protagonist’s name. In modern Greek, επώνυμο (eponimo) is the word for “surname”.

If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column, above the Twitter feed) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

Knickers!

What the word refers to …

In British English, it refers exclusively to an item of underclothing for girls and women, defined as “A woman’s or girl’s undergarment, covering the body from the waist or hips to the top of the thighs and having two holes for the legs”. In American English it also refers to loose-fitting breeches that are gathered at the knee, known in full as knickerbockers.

Men in baggy knickers! Sooo hot!

That explains why in this quote, Bobby [a boy] is not, as might appear to British readers, indulging an unhealthy fetish for ladies underwear:

Bobby was wearing new lace-up shoes and knickers with long, thick socks like most of the boys in my school.

Hudson Review, Autumn 2004.

In BrE it is also a very mild exclamation of irritation or contempt: “Oh, knickers to the lot of them!”

And it is used in many varieties of English in the idiom “to get one’s knickers in a twist” or variations on that theme, meaning to become angry, upset, or agitated, as in:

The Tories have really got their knickers in a twist over this.

“Knickers” is short for “knickerbockers”.

In 1809, the American novelist Washington Irvine published a History of New York, under the pseudonym of and purporting to be by one Diedrich Knickerbocker. The surname Knickerbocker, and close spelling variants, is Dutch and goes back to the earliest days of New York as a Dutch colony (New Amsterdam), and the word originally meant a descendant of the original Dutch settlers of the New Netherlands in America, hence, a New Yorker.

The dreadful Knickerbocker custom of calling on everybody.

Longfellow, Journal, 1 Jan, 1856

And nowadays it is still occasionally used to refer to New Yorkers (marked in the Oxford Dictionary Online as “informal”, but in Merriam-Webster as “broadly”):

Sex and the City unfolds in an elite New York that Edith Wharton or Nelson Rockefeller wouldn’t recognize. In this city, merit, not pedigree, rules. Unlike the old Knickerbocker establishment, where birth and breeding gave social standing, in this democratic meritocracy it is the prestige of your job that tells us where you are in the social order.

City Journal (New York), autumn 2003.

An edition of the book was illustrated by George Cruikshank (who also illustrated some of Dickens’s work, most notably Oliver Twist), and in it the eponymous hero is shown wearing knee breeches. Soon the word became popular to refer to this kind of trousers, and also to a ladies undergarment, which similarly extended as far as the knee, but has over time become shortened to its modern size–somewhat like the word itself.

These look like bloomers or drawers to me, but I’m no expert.

The two earliest OED examples for those meanings are:

1881 R. Jefferies Wood Magic I. i. 15 It was not in that pocket , … nor in his knickers.

(British, but the OED marks this use as “now U.S.”)

1882 Queen 7 Oct. 328/3, I recommend … flannel knickers in preference to flannel petticoat.

(British)

The OED also includes an amusing citation from Shaw:

Laws … are amended and amended and amended like a child’s knickers until there is hardly a shred of the first stuff left.

G. B. Shaw The Intelligent Woman’s Guide Socialism i. 2, 1928.

Do only Brits wear “knickers”?

The Oxford Dictionary Online labels them “British”, while Merriam-Webster labels this meaning “chiefly British”. The Oxford English Corpus (March 2013 data) paints a different picture, illustrating yet again how the boundaries between different varieties of English are fuzzy.

The total for the string “knickers” in the corpus is 2,827. Filtering out variations on “to get one’s knickers in a twist” leaves 2,526.

Of those, 1,658 (65.6%) are British, 221 (8.7%) American, and 118 (4.7%) Australian. While several of the American English examples refer to knickerbockers, some mirror the British English meaning. Clearly, in the following light-hearted example, the word is used as part of a repertoire of synonyms:

Firstly, Deb is organizing Operation Panty Drop, delivering brand-spankin’-new underpants to people in Houston who’ve been displaced and dispossessed by the hurricane. Send new knickers only, please — seriously, how would you feel if someone handed you a pair of used panties? Well, okay, it depends on the panties, I KNOW THAT, but pretend you don’t get turned on by things like that and just mail her a couple of new pairs of Hanes or something.

Blog (written by a woman), 2005.

Don’t you just love the name of the appeal!

An emergency undergarment drop.

Before I get branded as a paid-up member of the dirty mac brigade, I think I’ll sign off, since this blog is one of a series about eponyms. But I’ll come back to the idiom “knickers in a twist” another time.

Filed under: Word origins,

Derricks and other words named after people

We probably all know that the wellies we might wear to go on walks through muddy fields are named after the Duke of Wellington, the “Iron Duke”. Perhaps less well known is the link between the mac ��� in British English, at any rate ��� that we might also wear and its inventor, the deviser of the waterproof cloth from which macs are made, Charles Macintosh (1766���1843), the Scottish inventor who patented the cloth. Many units of scientific measurement, both everyday and more specialized, are named after their discoverers: the Italian physicist Count Alessandro Volta gave us volts, the Scottish engineer James Watt gave us, er, ��� watts, and the British Lord Kelvin gave his name to the units in which absolute temperature is measured.

If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column, above the Twitter feed) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

Such words, derived from someone���s name, are technically called eponyms, a word created in the 19th century from the Greek ep��numos “given as a name, giving one’s name to someone or something”, from epi “upon” + onoma “name” (�����������������; ������� + �����������, Aeolic ����������� name). The same Greek word for ���name��� has given English also anonymous and synonym(ous). And when people refer to the eponymous hero of such and such a novel, e.g. Fielding’s��Tom Jones, they mean that the title of the novel is its protagonist’s name.

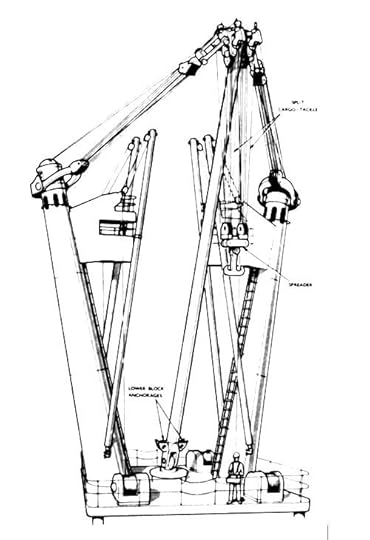

derrick ��� Not a misspelling of the Christian name Derek, but a word for a type of crane with a movable pivoted arm for moving heavy weights, especially on a ship (see the image below); and, perhaps more commonly these days, the framework over an oil well or similar boring, holding the drilling machinery.

This seemingly innocent, mechanical word conceals a rather grisly story, for derrick was originally a nickname for a hangman, and not just any old hangman. The man whose surname was Der(r)ick served under the Elizabethan magnifico��Robert Devereux, the second Earl of Essex, who was a great favourite of Queen Elizabeth.

At the siege of Cadiz, Der(r)ick committed rape and was sentenced to death, but was pardoned by the earl when he agreed to become the hangman at Tyburn, the place of execution of criminals (not far from present-day Marble Arch in London). He is said to have invented a more advanced and reliable��method of hanging that involved a beam and pulleys, and the word for it was then applied by analogy to similarly constructed cranes. This eponym therefore displays a semantic shift, unlike many others, whose referent stays the same.

A historical irony is that Der(r)ick ended up executing his own saviour, the Earl of Essex. The first citation for derrick��in the OED is dated circa 1600 and is from a lengthy “lamentable ditty”����� a ballad����� bewailing the execution of the earl,��on 25 February, 1601, for treason . (However, the version that I have been able to access online��wrongly dates his execution to 1603.)

Sweet Englands pride is gone,

Which makes her sigh and groan,

Evermore still,

He did her fame advance in Ireland Spain and France,

And by a sad mischance,

Is from us tane. [taken]

…

Derick, thou know’st at Cales I sav’d

Thy life lost for a rape there done,

As thou thyself can’st testifie,

Thine own hand three and twenty hung,

But now thou seest my self is come

By chance into thy hands I light,

Strike out thy blow that I may know

Thou ever loved at his good night.

…

But to Christ who for my sins did dye,

Trickling with salt tears in his sight

Spreading my arms to God on high,

Lord Jesus receive my soul this night.

The 2nd Earl of Essex; miniature attrib. to Nicolas Hilliard.

Apparently, it took three blows to sever his head����� well, he was well known for his brass neck����� and when the Queen was informed, she momentarily stopped playing the virginals, and then played on.

Filed under: Word origins,

April 3, 2015

Achingly astute: my latest linguistic hero

Praise from an unexpected quarter. Thanks, Kamahl.

Originally posted on In Praise of the Written Word:

Originally posted on In Praise of the Written Word:

First, I must tip my hat to my Al Jazeera Engish colleague Bernard Smith for emailing this link out to our whole newsroom. ��I hope everyone reads it.

Until today I���d never heard of Jeremy Butterfield. ��He is (seeing as you asked) the editor of Fowler���s Dictionary of Modern English Usage, and has written a brilliant��Comment is Free��article in today���s��Guardian newspaper:

http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/apr/03/bad-language-bugs-me

Jeremy is, I believe, a little bit like me. ��Slightly pedantic, occasionally furious, but always passionate about defending��the English language. ��The examples he gives in his article are things I see creeping into journalism all the time ��� even TV journalism, which is supposed to be all about simplicity and speaking normally.

Jeremy �����whether it���s the linguist���s hat or tinfoil hat you occasionally forget to don*,��I���m glad you do. ��English will of course evolve, as it must. ��But isn���t��it��equally, if not more important���

View original 26 more words

Filed under: Uncategorized

March 29, 2015

Biros, bics, and other words named after people

What’s in a name?

We all know that the wellies we might wear to go on walks through muddy fields are named after the first Duke of Wellington, the “Iron Duke”. Perhaps less well known is the link between the mac ��� in British English, at any rate ��� that we might also wear and its inventor, the deviser of the waterproof cloth from which macs are made, Charles Macintosh (1766���1843), the Scottish inventor who patented the cloth. Many units of scientific measurement, both everyday and more specialized, are named after their discoverers: the Italian physicist Count Alessandro Volta gave us volts, the Scottish engineer James Watt gave us, er, ��� watts, and the British Lord Kelvin gave his name to the units in which absolute temperature is measured.

Such words, derived from someone���s name, are technically called eponyms, a word created in the 19th century from the Greek ep��numos “given as a name, giving one’s name to someone or something”, from epi “upon” + onoma “name” (�����������������; ������� + �����������, Aeolic ����������� name). The same Greek word for ���name��� has given English also anonymous and synonym(ous). And when people refer to the eponymous hero of such and such a novel, e.g. Fielding’s��Tom Jones, they mean that the title of the novel is its protagonist’s name.

If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column, above the Twitter feed) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

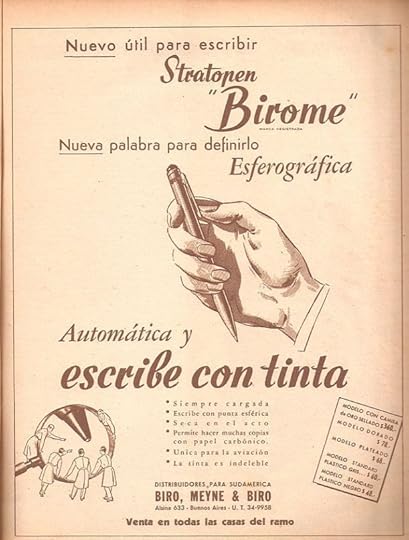

biro ��� the Hungarian inventor L��szl�� J��zsef B��r�� wanted to develop a pen with ink that dried quicker than that from a fountain pen, and, after earlier experiments, in 1938 patented his idea for what is known in British English as a biro (elsewhere ballpoint pen is the standard).

As a Jew, he was forced to flee Hungary after the Nazi occupation, and went to Argentina, where a biro is still known, in honour of him, as a birome. Elsewhere in the Spanish-speaking world it is known as un bol��grafo, because of the ball (bola) that controls the flow of ink (bol��grafo is also shortened to boli). Marcel Bich bought the patent from B��r����for production in France for the company which became BIC, and that is the name that biros are known by in French���in other words, they are also a French eponym.

Filed under: