Jeremy Butterfield's Blog, page 28

December 4, 2014

Ascribe to or subscribe to?: 20 words not to confuse (15-16)

(If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!)

[15-16 of 20 words good writers shouldn’t confuse]

Quick takeaway points

Using the construction ascribe to a view, idea, etc. in the way shown in the examples under the next heading is generally considered a mistake.

It appears from comments on the Merriam-Webster website that some people were taught at school that this construction is in fact correct.

The use of the correct subscribe to (= support, endorse), derives clearly and logically from that word’s earliest use of putting your signature to something, as explained at 4 below.

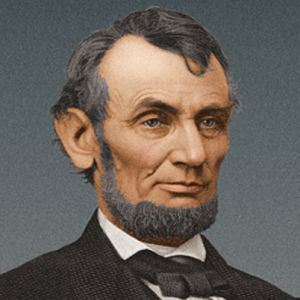

Lincoln used ascribe to in his inaugural presidential address. See 6.2.

1. What is the issue?

Take a sentence such as this from a 2006 issue of the Globe and Mail (Canada)

“In the twisted minds of those who ascribe to this militant ideology, Canada has become fair game.”

Or this:

“He doesn’t necessarily ascribe to the philosophy of ‘bigger is better’ or featuring loud colors or ‘sale’ logos to attract attention.”

Art Business News, 2003

The correct verb in both cases is subscribe.

“Yes, we know,” you may say: “you’re teaching your grandmother to suck eggs“. Nevertheless,  enough people commit the mistake to make it worth highlighting.

enough people commit the mistake to make it worth highlighting.

In fact, from a few comments on the Merriam-Webster online site, it seems that some people were actively taught by their schoolteachers that ascribe to is correct in this context, and that subscribe to is wrong.

2. 1 What is the correct use of ascribe to?

As Cobuild defines it, the word nowadays has three core meanings. Note that they all require the preposition to, and have a direct object and an obligatory prepositional object. In other words, you cannot say he *ascribed his success. [Most examples are from the Online Oxford Dictionary].

If you ascribe an event or condition to a particular cause, you say or consider that it was caused by that thing:

He ascribed Jane’s short temper to her upset stomach;

He ascribed the poor results to poverty and the lack of resources at most schools.

(Attribute works as a synonym for this (and the next meanings) or give the credit to, if it is a good thing, such as success.)

If you ascribe something such as a quotation or a work of art to someone (my amendment: or to some period) you say that they said it or created it, (my amendment: or that it was said or created in that period):

a quotation ascribed to Thomas Cooper;

He mistakenly ascribes the expression ‘survival of the fittest’ to Charles Darwin.

if you ascribe a quality to someone, you consider that they possess it:

Tough-mindedness is a quality commonly ascribed to top bosses;

I don’t want to ascribe human reactions to my dog, because that spoils the joy of seeing things from a dog perspective.

(See 6.2 for other, historical examples)

2.2 With which meaning of subscribe is ascribe confused?

Subscribe has many meanings, but the one in question is meaning 2 in the Online Oxford Dictionary:

(subscribe to) Express or feel agreement with (an idea or proposal):

Or maybe he subscribes to the postmodern idea that truth is a social construct;

We prefer to subscribe to an alternative explanation.

Closish synonyms for this meaning are agree with, support, back, accept, believe in and endorse.

3. What do usage guides say?

There is no mention of it in the excellent Merriam-Webster Concise Dictionary of English Usage, nor in the equally excellent Cambridge Guide to English Usage. The current (3rd) edition of Fowler’s Modern English Usage does not include it either, but I have added it to my revision for the 4th edition.

4. Can etymology help?

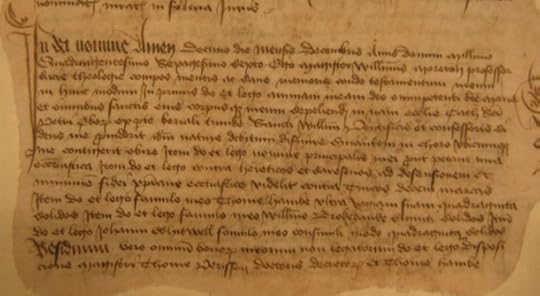

Rather obviously, both words contain the element -scribe, meaning “write”, imported ultimately from Latin, and all around us in words such as describe, inscribe, and so forth. The sub- element is the Latin for “under”, as in submarine, sub-editor, etc. So, literally, if you subscribe something, you put your name under it. The word was directly borrowed from Latin, and its first recorded use is as just described:

This is my last Will, subscribed with my own Hand, R.H.—1415

That meaning is defined by the OED as follows: “To put one’s signature or other identifying mark upon (a document), esp. at the end or foot, typically to signify consent or agreement, or to declare that one is a witness; to signify assent to or compliance with (something), by signing one’s name; to attest (a particular viewpoint or position) by one’s signature”.

If you want a mnemonic for which of the two words under discussion is appropriate in which context, it may help to remember support, which—ultimately, in Latin—contains the same prefix—sub, i.e. “under”—as subscribe. If you subscribe to a view, theory, etc., you do indeed support it.

5. How often does the mistake happen?

[Skip this if you don’t want the “science” bit]

It is true that it is not the commonest of mistakes, but then neither verb is particularly frequent in its own right. Subscribe (the specific form, not the lemma) just scrapes into the seven thousand most frequent words in English (in the Oxford English Corpus), which make up 90% of all texts: it occurs just under 7 times per million words of texts; ascribed (again, the token, not the lemma) comes in as the 12,200th most common form in English, occurring less than 3 times per million words.

Since the mistake most often occurs in collocation with words such as view and theory, and others in their lexical field, the only measure I can easily produce for its frequency is to compare the collocations subscribe to…theory and ascribe to…theory (within a five-word frame to the right). The first occurs 471 times in the OEC, the second 18 – i.e. in under 4 per cent of cases.

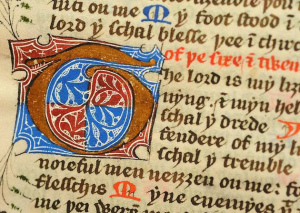

6.1 Biblical and Lincolnian uses

Many people on the Merriam-Webster website looked up the word because it is used in Psalm 29 in some versions of the Bible:

1 Ascribe to the Lord, O heavenly beings, ascribe to the Lord glory and strength.

2 Ascribe to the Lord the glory of his name; worship the Lord in holy splendor

New Oxford Annotated Bible

(It is worth noting that the Authorized Version (King James) does not use ascribe in this context, but the more Anglo-Saxon Give unto the Lord, O ye mighty, etc.

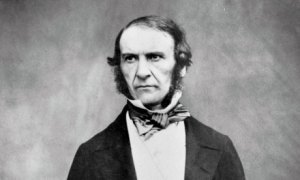

Abraham Lincoln also used it in his first inaugural address (March 4, 1861):

If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through his appointed time, he now wills to remove, and that he gives to both North and South this terrible war, as the woe due to those by whom the offense came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to him?

6.2 Other historical examples

The OED subdivides ascribe into 11 senses, of which six were already labelled obsolete as long ago as 1885, when the entry was compiled.

It was first used in English in the Wycliffite Bible, and is among  the earliest ten per cent of words the OED records.

the earliest ten per cent of words the OED records.

On its first appearance it was used broadly in the first meaning discussed above:

Lest…to my name the victorie be ascrived—2 Sam. xii. 28, before 1382

(The spelling with v mirrors the Old French form from which it was borrowed. In the 16th century it was Latinized to a letter b.)

Other examples in this use, as shown below, range from Sir Thomas More to Samuel Johnson:

Al which miracles al those blessed saintes do ascribe vnto the worke of god.—Thomas More, Heresyes IV, in Wks. 286/2, 1528

The same Græcians did often ascribe madnesse to the operation of the Eumenides.—Hobbes, Leviathan I. viii, 37, 1651

This Speech is…the finest that is ascribed to Satan in the whole Poem.—J. Addison, Spectator No. 321. ¶6, 1711

We usually ascribe good, but impute evil.—Johnson, The Plan of a Dictionary of the English Language 25, 1746

Filed under: Advice for writers, Confusable words, Dictionaries & Lexicography, Grammar, Meaning of words, OED Tagged: 20 confusable words

November 26, 2014

To decry or descry an evil? 20 words not to confuse (13-14)

If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

[13-14 of 20 words good writers shouldn’t confuse]

A rare confusion

Only one letter separates these two not particularly frequent words, so perhaps it is hardly surprising that they are very occasionally confused.

Though distantly related in origin (see further down) they now have widely different meanings. If you remove the prefix de- of decry, you are left with cry. And in fact that prefix has historically been interpreted as “down”. So, if it helps to distinguish the two words, think of decrying something as crying it down.

A profile of decry

Of the two, decry is by far the commoner, but even so it only occurs about 2.6 times in every million words of texts in the massive Oxford English Corpus (OEC). (For comparison, criticize occurs 40 times every million.)

If you decry something, you publicly express your severe disapproval of it.

As part of its semantic profile, typical objects are the lack or absence of something, the decline in something, the evils of something, and generally disparaged vices, attitudes and facts such as racism, greed, inequality, hypocrisy.

Typical subjects are critics, purists, feminists, pundits, liberals and conservatives. Approximate synonyms are denounce and condemn, which could replace it in some of the examples below, all of which are authentic (i.e. not made up) and from written texts, mostly in the OEC :

They decried human rights abuses.—Oxford Dictionary Online

She decries the spread of tower blocks and the failure to turn derelict sites into green spaces.—Evening Standard, 2007

The Archbishop will also decry the lack of moral vision displayed by MPs compared to the likes of William Wilberforce, who was instrumental in the abolition of the slave trade 200 years ago.—The Telegraph, 2007

Feminists have long decried psychology’s devaluing of women’s voices in treatment decisions.— Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 2002

#CameronMustGo: Twitter users decry Cameron’s record.—Guardian, 24 November, 2014

Descry

If you descry something or someone, you catch a glimpse of them, or catch sight of them, often from a distance, or with difficulty. It occurs in a ratio roughly of 1:40 to decry, and is typical of formal, journalistic or literary registers. (Some of the occurrences of the form descried are actually typos for described)

To meet Albert, whom I descried coming towards us.—Queen Victoria’s Journal, 1868

Her thoughts were brought to an abrupt end, as she descried two figures on their way up the path—J. Ashe, 1993

While he clearly indicates productions he considers successful, I would be hard-pressed to descry a pattern among them.—OEC, 2000.

Peering over his shoulder, I descried that he was studying “Malley’s” 16th poem, “Petit Testament,” with its reference to – “Quick. Watson,” he cried.

“The Shakespeare!” I sprang to the bookshelves.—Jacket Magazine, 2002

“The Shakespeare!” I sprang to the bookshelves.—Jacket Magazine, 2002Through the murk of battle, the fog of US and British military communiques and the more deftly presented Iraqi bulletins, we can begin to descry the shape of things to come.—Sunday Business Post, 2003

The two should not be confused, as has happened in the next example:

X I have some sympathy with people who descry this, and who argue that society’s easy tolerance of single mothers…

is actually fostering moral irresponsibility.—OEC, 2005

Fascinating origins: decry

Decry was first used in the early 17th century in the sense “decrease the value of coins by royal proclamation” — in other words, a form of devaluation. Its etymology is de- “down” + cry, from the French décrier , to “cry down”.

The OED first records it in a quotation from the catchily titled 1617 work of the extraordinary Elizabethan traveller and writer Fynes Moryson (of whom more below): An itinerary…containing his ten yeeres travell through the twelve dominions of Germany, Bohmerland [sc. modern Czech Republic], Sweitzerland, Netherland, Denmarke, Poland, Italy, Turky, France, England, Scotland, and Ireland. Divided into three parts.

(it appears that the OED contains nearly 1,400 quotations from this work.)

Having a singular Art to draw all forraine coynes when they want them, by raising the value, and in like sort to put them away, when they haue got abundance thereof, by decrying the value.—I. III. vi. 289

And here is a later example of the same meaning, by the famous diarist John Evelyn:

Many others [sc. medals of Elagabalus] decried and call’d in for his Infamous Life.—Numismata, vi. 204, 1697

It is quite easy to see how this sense had given rise by 1641 to the metaphorical one of disparaging or condemning something, as in this example from Pepys’ diary for 27 November 1665:

The Goldsmiths do decry the new Act.

Descry

Like decry later on, descry came into Middle English from across the Channel, from Old French descrier to “publish, proclaim”. The OED suggests that it was influenced by or confused with the obsolete spelling descry meaning “describe”, and states that in some contexts it is impossible to know which is meant.

One of its earliest, and now obsolete, meanings was “to proclaim as a herald”, and it has had several other meanings, but at its first appearance in 1440 it already had more or less its modern meaning, as the OED defines it, “to catch sight of, esp. from a distance, as the scout or watchman who is ready to announce the enemy’s approach”. It appears in the classic Middle English text Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (c1400):

Þe comlokest [lady] [sc. comeliest] to discrye.

A truly adventurous life

Fynes Morison spent several years travelling through Europe and the Near East, as well as serving on the staff of the English army in Ireland. He seems also to have been a master of disguise, and a polyglot. As the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography writes:

“Moryson was well equipped to write his Itinerary. By his own account he was fluent in German, Italian, Dutch, and French, and his linguistic ability served him well in regions where an Englishman might expect to meet hostility: he generally posed as German or Dutch in the more dangerous states in Italy, adopting a second cover as a Frenchman when visiting Cardinal Bellarmine at the Jesuit college in Rome; he dressed as a down-at-heel Bohemian servant to avoid Spanish troops in Friesland; he passed himself off as a Pole when entering France; and he was got up as a German serving-man when a party of disbanded French soldiers robbed him near Châlons. Travelling without substantial funds or official protection, he survived at various times by adopting a deferential posture, avoiding eye contact, attaching himself to other parties of travellers, concealing a reserve of cash, and keeping his religious convictions to himself, as when he used ‘honest dissembling’ to pass as an English Catholic when lodging with French friars in Jerusalem.”

Filed under: Advice for writers, Confusable words, Grammar, Writing Skills Tagged: 20 confusable words

November 21, 2014

20 Words good writers shouldn’t confuse

As you can see, they’re a mixed bag. They are not of the obvious affect/effect type, because they are not as frequently used. Some of them are more literary or formal–which means that they will appear in the kind of writing where they will stand out like a sore thumb to informed readers.

adverse to / averse to

cache / cachet

coruscating / excoriating

flaunt / flout

home in on / hone in on

veracious / voracious

Those I’ve yet to blog fully about are below (examples from or adapted from, Oxford Online Dictionary)

decry / descry

If you decry something, you express your disapproval of it:

e.g. They decried human rights abuses.

If you descry something or someone, you catch a glimpse of them, often from a distance and with difficulty:

e.g. She descried two figures approaching.

defuse / diffuse

You defuse an explosive device, and as a metaphor, a tense or explosive situation:

e.g. The situation was defused by quick-thinking American officers.

If something diffuses it spreads, and if you diffuse it, you spread it:

e.g. technologies diffuse rapidly;

the problem is how to diffuse power without creating anarchy.

elusive / illusive

Something elusive is difficult to find or get; it eludes you.

e.g. Success will become ever more elusive;

Happiness is an elusive concept, rather like love.

Something illusive is an illusion. However, the word is almost always used by mistake for elusive:

e.g. X Sharks up to forty feet are quite common, although when Helen was there they proved to be illusive.

(Should be elusive.)

subscribe to / ascribe to

If you subscribe to an idea or a suggestion, you believe in it or agree with it. (In other words, you “sign up” to that idea, in the same way as you subscribe to online news or to a magazine.)

e.g We prefer to subscribe to an alternative explanation.

If you ascribe something to a particular event or situation, you believe that event or situation caused it:

e.g He ascribed Jane’s short temper to her upset stomach.

And if you ascribe a quality to someone, you believe that they have that quality:

e.g. Tough-mindedness is a quality commonly ascribed to top bosses.

Filed under: Advice for writers, Business Writing Skills, Confusable words, Grammar, Meaning of words, Oxford Online Dictionary Tagged: 20 confusable words

20 Words Good Writers Shouldn’t Confuse

As you can see, they’re a mixed bag. They are not of the obvious affect/effect type, because they are not as frequently used. Some of them are more literary or formal–which means that they will appear in the kind of writing where they will stand out like a sore thumb to informed readers.

adverse to / averse to

cache / cachet

coruscating / excoriating

flaunt / flout

home in on / hone in on

veracious / voracious

Those I’ve yet to blog fully about are below (examples from or adapted from, Oxford Online Dictionary)

decry / descry

If you decry something, you express your disapproval of it:

e.g. They decried human rights abuses.

If you descry something or someone, you catch a glimpse of them, often from a distance and with difficulty:

e.g. She descried two figures approaching.

defuse / diffuse

You defuse an explosive device, and as a metaphor, a tense or explosive situation:

e.g. The situation was defused by quick-thinking American officers.

If something diffuses it spreads, and if you diffuse it, you spread it:

e.g. technologies diffuse rapidly;

the problem is how to diffuse power without creating anarchy.

elusive / illusive

Something elusive is difficult to find or get; it eludes you.

e.g. Success will become ever more elusive;

Happiness is an elusive concept, rather like love.

Something illusive is an illusion. However, the word is almost always used by mistake for elusive:

e.g. X Sharks up to forty feet are quite common, although when Helen was there they proved to be illusive.

(Should be elusive.)

subscribe to / ascribe to

If you subscribe to an idea or a suggestion, you believe in it or agree with it. (In other words, you “sign up” to that idea, in the same way as you subscribe to online news or to a magazine.)

e.g We prefer to subscribe to an alternative explanation.

If you ascribe something to a particular event or situation, you believe that event or situation caused it:

e.g He ascribed Jane’s short temper to her upset stomach.

And if you ascribe a quality to someone, you believe that they have that quality:

e.g. Tough-mindedness is a quality commonly ascribed to top bosses.

Filed under: Advice for writers, Business Writing Skills, Confusable words, Grammar, Meaning of words, Oxford Online Dictionary Tagged: 20 confusable words

A cache of arms not a cachet: 20 words not to confuse (11-12)

People sometimes use cachet when cache is required. Despite having five letters in common, and coming ultimately from the same French verb (cacher), in English they are completely unrelated. A cache of something is a “collection of items of the same type stored in a hidden place” such as an arms cache or a cache of gold and rhymes with cash.

Cachet is “prestige, high status; the quality of being respected or admired” and rhymes with sachet. The next two examples show the words being used correctly:

Several inmates seized a cache of grenades and other weapons and killed six security officers, including a high-ranking counterterrorism official;

The department stores knew they had to offer something different, something perceived to have more cachet.

In the next one, cachet is wrong, and cache would be correct: Egyptian excavators this week chanced upon a cachet of limestone reliefs.

Filed under: Advice for writers, Confusable words, Grammar, Meaning of words, Writing Skills Tagged: 20 confusable words

November 18, 2014

Charlotte Bronte���s last love letter

Fascinating piece of literary detection.

Originally posted on Rereading Jane Eyre :

Originally posted on Rereading Jane Eyre :

���To forbid me to write to you, to refuse to answer me, would be to tear from me from my only joy on earth, to deprive me of my last privilege _ a privilege I shall never consent willingly to surrender. Believe me, my master, in writing to me it is a good deed that you will do. So long as I believe you are pleased with me, so long as I have hope of receiving news from you, I can be at rest and not too sad.���

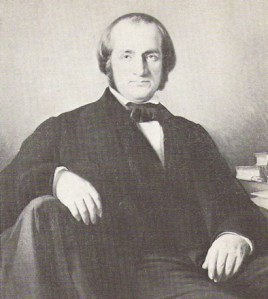

The last known love letter Charlotte Bronte wrote to her ���master���, the man she fell madly in love with in her early twenties, her Belgian professor, Constantin H��ger, was written on 18th November 1845,exactly 169 years ago, tomorrow.

[image error]

M H��ger

What do we know of the love life of the woman who penned one of the greatest love stories ever written?���

View original 1,039 more words

Filed under: Uncategorized

Charlotte Bronte’s last love letter

Fascinating piece of literary detection.

Originally posted on Rereading Jane Eyre :

Originally posted on Rereading Jane Eyre :

‘To forbid me to write to you, to refuse to answer me, would be to tear from me from my only joy on earth, to deprive me of my last privilege _ a privilege I shall never consent willingly to surrender. Believe me, my master, in writing to me it is a good deed that you will do. So long as I believe you are pleased with me, so long as I have hope of receiving news from you, I can be at rest and not too sad.’

The last known love letter Charlotte Bronte wrote to her ‘master’, the man she fell madly in love with in her early twenties, her Belgian professor, Constantin Héger, was written on 18th November 1845,exactly 169 years ago, tomorrow.

M Héger

What do we know of the love life of the woman who penned one of the greatest love stories ever written?…

View original 1,039 more words

Filed under: Uncategorized

Antidisestablishmentarianism: the longest word in English (or not?). History of an enigma.

1 The longest word?

1 The longest word?Everyone knows that it’s “the longest word in English”, with its 28 letters. Actually, it isn’t. The “longest word in any dictionary” depends on the dictionary: in the Oxford Dictionary Online it is pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis, which weighs in at 45 letters; that word is not in Merriam-Webster Online (though it is in their Unabridged), nor is antidisestablishmentarianism.

2 Has it always been “the longest word”?

I can’t say when antidisestablishmentarianism acquired its mythical status (but see 3 below for some evidence).

However, a search of Google Ngrams shows that in 1901, in an issue of the Writer, A Monthly Magazine for Literary Workers, founded by two Boston Globe journalists, it was the four-letters-shorter disestablishmentarianism that was cited as the longest word in English.  (The magazine is still going strong). And in Current Advertising of the same year, there is the following quote: “If anybody really wants to know, it may be authoritatively stated that the longest legitimate word is disestablishmentarianism. Don’t let the fact that it isn’t in the dictionary worry you. The word was coined and used by the late Mr. Gladstone…” (that attribution is probably apocryphal).

(The magazine is still going strong). And in Current Advertising of the same year, there is the following quote: “If anybody really wants to know, it may be authoritatively stated that the longest legitimate word is disestablishmentarianism. Don’t let the fact that it isn’t in the dictionary worry you. The word was coined and used by the late Mr. Gladstone…” (that attribution is probably apocryphal).

3 Is it a “real” word?

3.1 Yes, as I think this blog will demonstrate. However, a bit like the running machine that sits, rarely or never switched on, in some people’s homes, it is more exciting as an idea than in reality: it is more talked about and discussed qua longest word than ever actively used. Merriam-Webster goes so far as to say that “Merriam-Webster doesn’t enter antidisestablishmentarianism in any of its dictionaries because the evidence indicates that the word is almost never used anymore”.

It is not, of course, actively used, because the circumstances that gave rise to it no longer exist. It is a treasured fossil, a curiosity.

3.2 Interestingly, the first OED entry for antidisestablishmentarianism is from Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable of 1923, at the entry for long words. However, the Bulletin of the Grosvenor Library, Buffalo (Volumes 1-4, p. 168), has this from 1918: “I can go this one better, with a word which I have been told, ever since childhood, was the longest in the English language, it is antidisestablishmentarianism, containing 28 letters, and meaning, of course, the doctrine of those who did not wish…” The “this” apparently refers to an earlier claim in the same publication that anthropomorphologically (23 letters) was the longest.

3.3  And a 1919 edition of Everyland: A Magazine of World Friendship for Girls and Boys has this: “Dorothy Knudson says it is “antitransubstantiationalistically” : Alison Bryant, Rose Gibson, Lucretia Ilsley, and Isabel Weedon say it is antidisestablishmentarianism.” (Vol 10, Issues 7-12, p. 336.)

And a 1919 edition of Everyland: A Magazine of World Friendship for Girls and Boys has this: “Dorothy Knudson says it is “antitransubstantiationalistically” : Alison Bryant, Rose Gibson, Lucretia Ilsley, and Isabel Weedon say it is antidisestablishmentarianism.” (Vol 10, Issues 7-12, p. 336.)

From which it is clear that by that date several readers of the magazine took anti…ism to be the longest. As regards the even longer, 33-word contender, antitransubstantiationalistically, that it was ever actually used looks extremely dubious.

4 Why is it known as the longest word?

Partly, I suggest, because it consists of familiar individual parts that make it possible to remember, unlike, say, the monster mentioned at 3.3 above. It also has, to my mind at least, a distinct personality.

I can remember being told about it as a child. Its eleven (or twelve, depending) syllables with their repeated i and s sounds had an amazing dynamism, like a choo-choo building up steam towards the main stress on the eighth. And its two negative prefixes, anti- and dis-, seemed bafflingly at loggerheads with one another, creating a strange double negative. It had all the magical, talismanic power that words can have for young children. Once heard, it can never be unremembered.

5 What do all the different bits mean?

It is also a remarkable example of how prefixes and suffixes can be coupled together, a bit like railway carriages. If you uncouple them, what do you get? anti-dis-establish-ment-arian-ism. In other words, the locomotive of this word is the verb establish. Why is that?

6 It’s all to do with politics and religion

In England, the Church of England is “established”. This means it is the official Church, and has several links with the State. For instance, the monarch is its head, and any measures passed by the Church’s governing body have to be approved by Parliament. (In the US, in contrast, no Church has this constitutionally privileged role).

Historically, this dominance of the Church of England has been disputed—and in some circles still is. Those in favour of maintaining it as the established Church were called establishmentarians…

6. 1 Establishmentarian

The OED records this word as a noun from 1846, and as an adjective from 1847: “Those who, like myself, are called High Churchmen, have little or no sympathy with mere Establishmentarians.”—Hook, 1846.

It seems that Gladstone did not much care for the word: in the Contemporary Review of June 1875 he wrote “The prosecutors…are strongly (to use a barbarous word) establishmentarian.”

(It is worth remembering that Gladstone was a considerable classical scholar, and will no doubt have had firm views on what were barbarous—that is questionably formed from an etymological point of view—words).

6.2 Establishmentarianism

And the philosophy upheld by establishmentarians is of course…establishmentarianism. In 1873 the noted philologist Fitzedward Hall wrote of Richard Chenevix Trench  (the admirer of female rowing crews and original inspiration for the creation of the OED) that “Establishmentarianism was wont to roll over the prelatial [Abp. Trench's] tongue“. Chenevix Trench was in fact Archbishop of Dublin when the C of E was disestablished in Ireland, in 1871.

(the admirer of female rowing crews and original inspiration for the creation of the OED) that “Establishmentarianism was wont to roll over the prelatial [Abp. Trench's] tongue“. Chenevix Trench was in fact Archbishop of Dublin when the C of E was disestablished in Ireland, in 1871.

6.3 A secondary, more modern meaning

The adjective cum noun establishmentarian also has a more modern meaning, as the OED defines it: “Pertaining to or characteristic of the establishment; supportive of or favouring the establishment and its values; establishment-minded, conservative”. First recorded, it seems, in the economist J.K. Galbraith’s journal in early 1962. A more recent example is: In 1976 , he left the abortion rights league, in part because he believed it was becoming too establishmentarian” (NYT, 2006).

6.4 Disestablishmentarian

Those in favour of disestablishing the Church were, naturally, disestablishmentarians, first recorded from 1885 in the unrevised OED entry, but traceable in Google Ngrams at least as far back as The Church Herald of 1874: “…no public event has done more mischief as regards turning men’s minds into a Disestbalishmentarian channel than the recent policy of the Bishops’ Bench as expounded by the two Primates.”

And their philosophy is disestablishmentarianism (OED, 1897).

6.5 Antidisestablishmentarian(ism)

Those opposed to disestablishment are, inevitably, antidisestablishmentarians. If you knocked off the first two prefixes, you would get back to establishmentarian, which would not, however, mean exactly the same thing. The first OED entry for antidisestablishmentarian is from the journal Notes and Queries of 1900. And for antidisestablishmentarianism from 1923, as previously mentioned, which takes us full circle

Filed under: Dictionaries & Lexicography, Grammar, Meaning of words, OED, Oxford Online Dictionary, Word Histories

November 11, 2014

The longest word in the English Dictionary

When I was growing up, antidisestablishmentarianism was quoted by masters at school as the longest word in English. But at a mere 28 characters it is something of a pygmy in comparison with, pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis, an invented, pseudo-scientific term for a type of lung disease, with its 45 letters.

When I was growing up, antidisestablishmentarianism was quoted by masters at school as the longest word in English. But at a mere 28 characters it is something of a pygmy in comparison with, pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis, an invented, pseudo-scientific term for a type of lung disease, with its 45 letters.

So, what really is the longest word in English, and which is the longest word in “the dictionary”? Those questions can only be answered satisfactorily by first posing and then answering some prior questions that they raise.

What is a word?

What do you class as a word for these purposes?

Can you include names, such as the legendary Welsh place name Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch?

Do you count invented words such as supercalifragilisticexpialidocious, made famous by the film Mary Poppins?

Or do you only include words that have been created by actual usage? If so, antidisestablishmentarianism might be a better candidate than some.

Do you include scientific names, such as that ne plus ultra of sesquipedalianism, the scientific name for the protein titin, which starts Methionyl… and goes on for another 189,910 letters (yes, that’s right, you didn’t misread it: one hundred and eighty-nine thousand, nine hundred and ten).

What does “in the dictionary” mean?

The first question is: which dictionary? Not all dictionaries are equal. The Oxford English Dictionary and the Oxford Dictionary Online both include the supercali… word; Collins, Merriam-Webster online, and Macquarie do not. The two Oxford dictionaries, and Macquarie include floccinaucinihilpilification; Collins and M-W do not.

Technical or non-technical?

Broadly speaking, the dictionaries mentioned above are, apart from the OED, general dictionaries that anyone might readily consult. But in scientific areas, only specialists in the discipline concerned will consult such volumes as, for example, the Royal Society of Chemistry’s Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry (known as the “Red Book”), which states the rules for naming inorganic compounds.

And do you include words that appear in dictionaries of foreign languages, and have been translated or transliterated into English? If so, you might give some thought to the 183 letters of the Classical Greek

“Lopadotemachoselachogaleokranioleipsanodrimhypotrimmatosil

phioparabomelitokatakechymenokichlepikossyphophattoperistera

lektryonoptekephalliokigklopeleiolagoiosiraiobaphetraganopterygon“.

This is a transliteration of a comical word coined by the Greek playwright Aristophanes to describe a fictional dish that is defined by Liddell & Scott as “compounded of all kinds of dainties, fish, flesh, fowl, and sauces”. Since the dish never existed, we need not be put off by its rebarbative mixture of fish, meat, seafood, fowl, and birds.

What is interesting is that the fascination with long words is clearly not just a modern curiosity, the result of printing and universal literacy. The Aristophanic word suggests that it is clearly ancient. It makes you wonder just how often Greeks in the Classical Age asked themselves: “I wonder what the longest word is…”

Filed under: Dictionaries & Lexicography, Grammar, OED, Oxford Online Dictionary Tagged: Longest word

November 5, 2014

Averse to adverse to: 20 words not to confuse (9-10)

[9-10 of 20 words good writers shouldn’t confuse]

1. Takeaways – in a nutshell

Using “to be adverse to something” to mean “to dislike something” is considered a mistake by many people, dictionaries, and usage guides.

It has been suggested that this use may be more common in American English than in British English.

Beware of incorrectly using x averse in phrases such as “to have an adverse reaction to something”.

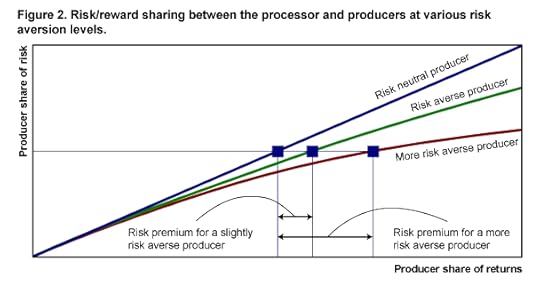

Conversely, beware of using adverse in compound adjectives formed with averse: risk-averse, not x risk-adverse.

2. In detail

2.1 Averse

How many times have you seen sentences such as “He was not adverse to compromising himself politically for the sake of his career” or “Are Scottish people adverse to a little sex in their movies?”

They seem to confuse two words that are almost identically spelled but have rather different meanings.

The standard construction to suggest that a person has a strong dislike of or antipathy towards something is averse to, often used with negation:

Examples (from Oxford Dictionary Online)

• Strong and aggressive, he is not averse to a bit of shirt pulling and uses his arms effectively to hold off defenders.

• Now some of you may know that if an opportunity arises of a little fun with a person of the opposite sex I’m not averse, rare as it is.

• I also stand to see the value of my property increase, which I’m not averse to.

• I am a recent alumna of the University of Waterloo and do not consider myself in any way averse to liberal writing.

• I’ve noticed I’m becoming more and more averse to what I call overt luxury.

As in all but one of the examples above-and note how most of them are first person statements-, averse in negative contexts is often a form of ironic understatement, or litotes: “I’m not averse to” means something like “I’m really rather keen on” (though perhaps reluctant to admit it). All the examples above also show averse being used in the structure to be averse to, i.e. predicatively.

Averse is also often used as the second part of a compound adjective, such as risk-averse, change-averse and so forth.  Occasionally NOUN-adverse is wrongly used, as in this article on the use of “guys”.

Occasionally NOUN-adverse is wrongly used, as in this article on the use of “guys”.

2.2 Adverse

Adverse, broadly speaking, means: “unfavourable” (an adverse balance of trade, adverse circumstances, adverse weather conditions); “hostile” (adverse criticism, an adverse reaction); or “harmful” (adverse effects)

Examples (from Oxford Dictionary Online/Oxford English Corpus)

• From 1997 to 2000, the combination of adverse weather and declining sales led to retrenchment by any cooperatives.

• A series of meetings at the department after the leak of cabinet papers and the widespread adverse reaction to the government’s plans has led ministers to slow the process.

• Such events promote Belfast’s image and go some considerable way to countering the adverse publicity the city has often received over the years.

• The trials had been cancelled after the drug was found to cause an adverse reaction.

• Roadworks on three of the routes in and out of Skipton are having an adverse effect on local businesses.

In contrast to averse, in these examples adverse modifies a following noun (in other words, it is attributive).

3. Can the word’s origins help?

Without falling into the etymological fallacy, (the notion that a word’s original meaning, or its meaning in the language from which it derives, is its only true meaning) examining these two words’ origins may help clarify the distinction between them.

Both come from Latin, and contain the Latin verb vertere, “to turn”, found in so many other verbs and adjectives, (convert, divert, extrovert, invert, pervert, etc).

The late 16th century averse comes from Latin aversus ”turned away from”, past participle of avertere. The a- part gives it the meaning “away from”. The old-fashioned phrase “avert your gaze” means “turn your gaze away”, in other words “look away”. Remembering that, and the related noun aversion, may help to crystallize the distinction.

In contrast, adverse from Latin adversus “against, opposite”, suggests the notion of one thing being in opposition to another, and therefore hostile or unfavourable to it. Its related noun is adversity, a synonym for misfortune or difficulty.

4. adverse to: a complication

To be adverse to mirrors averse to structurally in certain phrases, particularly in legal contexts, e.g. “…‘adverse party’ includes every party whose interest on the case is adverse to the interests of the appellant…”–Wisconsin Statutes, 1947; “…the whole parliamentary tradition as built up in this country…is adverse to it“–Winston Churchill, 1942. But in this meaning it refers to things, to external circumstances, whereas, as we have seen, averse to refers to someone’s personal tastes and inclinations.

5. What do usage guides say?

The Oxford Dictionary Online has a note that calls e.g. “He is not adverse to making a profit” a mistake. The AP Style Guide and the British Guardian Style Guide draw an absolute distinction between the two words, as does Fowler.  Merriam-Webster’s Concise English Usage has a long, scholarly, slightly non-committal discussion pointing to potential overlaps between the two words. The grammar checker in Microsoft’s Word will flag up “not adverse to” as a mistake-which is helpful for many people, but could cause problems for those–often, but not necessarily, lawyers–who are using it correctly.

Merriam-Webster’s Concise English Usage has a long, scholarly, slightly non-committal discussion pointing to potential overlaps between the two words. The grammar checker in Microsoft’s Word will flag up “not adverse to” as a mistake-which is helpful for many people, but could cause problems for those–often, but not necessarily, lawyers–who are using it correctly.

A quick scan of Google Ngrams for “not averse to” and “not adverse to” suggests that while “not adverse to” was previously often confined to legal contexts of the kind mentioned at 4. above, recent decades show an increase in its use as a substitute for the preferred “not averse to”.

In the Oxford English Corpus, a simple search for “adverse to” shows that in British English 60 per cent of examples are in legal contexts, and therefore assumed to be correct, but in American English that figure is less than 1 per cent.

However, it cannot automatically be inferred that the use of the phrase in non-legal contexts is wrong. In fact, in AmE only one third of those non-legal uses were of the criticized use, while in BrE it was over two thirds. If one compares the number of times averse to was actually used with approximate estimates of how often adverse to was used for it by mistake, the figures are as follows: BrE 730/92; AmE 662/81 giving ratios of around 8:1 for both. This evidence does not suggest that the mistake is more frequent in AmE than in BrE.

Filed under: Advice for writers, Confusable words, Fowler's Modern English Usage, Grammar, Meaning of words, Oxford Online Dictionary, Writing Skills Tagged: 20 confusable words