Jeremy Butterfield's Blog, page 27

March 7, 2015

“Suffice it to say” or “suffice to say”?

The plot makes twists and turns like a snake writhing in the desert. To tell would be to spoil, but suffice to say, writer, director and cast have colluded brilliantly.

Fraser’s scenes are painfully boring to watch���suffice it to say,��he’s not a master of physical comedy.

Take Our Poll

An editor in an online editorial group recently raised the question of which version is correct, and her query elicited more than 80 comments. Many people swore that suffice to say was the correct and only version, and that suffice it to say was a ���hairy mutant���. People in the other camp lambasted their opponents, and resorted to dictionaries to prove beyond a doubt that the four-word version was gospel. What is the truth of the matter?

Quick takeaways

Both forms are in use (see more detail at Frequency below).

Suffice it to say was formerly considered standard, and is still seen by many people as the only correct formulation.

However, possibly because of its puzzling syntax, it is often “regularized” to suffice to say.

The traditional formula is still widely used, and useful, despite being considered pompous or old-fashioned by some.

There are strange variations on it, such as sufficed to say and the eggcornish surface it to say.

Below, I look in more detail at the grammar, frequency and history of this phrase, which the Oxford Dictionary Online aptly defines as “Used to indicate that one is saying enough to make one���s meaning clear while withholding something for reasons of discretion or brevity.”

Syntax

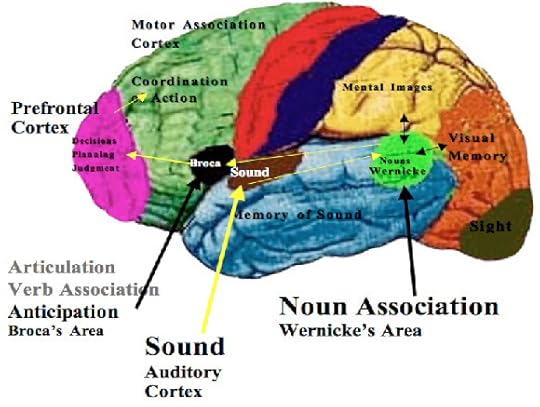

Three things are worth mentioning about suffice it to say. First, the subject of the sentence is the ���dummy��� or impersonal it. Second, the verb form is subjunctive���the absence of the normal third person singular -s shows this, i.e. suffice, rather than suffices. Third, there is subject-verb inversion.

The phrase thus belongs to that very small group of ���fossilized��� phrases in which the subjunctive is used: God save the Queen!��far be it from me to…, Perish the thought! All of them could be rewritten as ���Let + subject + verb��� i.e. let God save the Queen, let it suffice to say, etc.

However, the fact that such subjunctive phrases are rare and on the fringes of most people���s grammar means, I believe, that they have difficulty analyzing the ���suffice it to say��� form, and therefore attempt to regularize it to “suffice to say”. The inversion of subject and verb presents a further block to analysis.

���Suffice to say���, however, while sounding superficially like a second person imperative���stand up, wake up, pay attention, etc.���is as anomalous as the four-word form. Who is being addressed in this imperative?

Current situation

Frequency

The Oxford English Corpus��(OEC) has slightly more examples of the string ���suffice to say��� than of “suffice it to say”: 952: 937 (and each occurs less than once per million words of text.) However, filtering out ���suffice to say��� as a zero infinitive, e.g. in phrases such as let it suffice to say, it should suffice to say, etc., reduces its total to well below 900, and therefore less frequent than the longer form.

Though the shorter form is used in all varieties of English, its use does seem to be particularly marked in Australian English, at least in the OEC data.

In the Corpus of Contemporary American, the distribution is very different: 376 occurrences of the longer version against 97 for the shorter. It is noticeable that in academic writing the longer form occurs in a ratio of 6:1.

A Google Ngrams comparison of “suffice to say” and “suffice it to say” suggests a decline in the use of both phrases over the last century, However, “suffice to say” is often the zero infinitive mentioned previously, so it would be too time-consuming to compare the frequency of the two forms over time. For the period 1960-2000 (i.e., the latest period covered) “suffice it to say” is the more frequent of the two forms.

Dictionaries

Both the Oxford Online Dictionary and Macquarie bracket the it: suffice (it) to say, indicating clearly that they accept it as optional. Merriam-Webster Online notes “often used with an impersonal it Collins shows only the complete phrase.

History

The unrevised entry in the OED heads the relevant sense with the following rubric: ���Const[ruction] inf[initive] or clause with, or (formerly) without, anticipatory dummy subject it. Now chiefly in the subjunctive, suffice it , sometimes short for suffice it to say .”

The first OED citation of this impersonal use is from the Middle English (1390) Confessio Amantis:

to studie upon the worldes lore Sufficeth now withoute more.

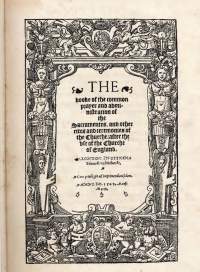

There is one more citation before  the Book of Common Prayer on Publyke Baptisme��f. iiii*v (1549)

the Book of Common Prayer on Publyke Baptisme��f. iiii*v (1549)

If the childe be weake, it shall suffice to powre water vpon it.

However, the first citation for the exact phrase ���suffice it to say��� does not appear until a 1779 edition of the periodical The Mirror:

Suffice it to say, that my parting with the Dervise was very tender.

An earlier citation,(1692), however has:

It suffices to say, That Xantippus becoming the manager of affairs, altered extreamly the Carthaginian Army.

In the��Corpus of Historical American, the string “suffice to say” is mainly of the zero infinitive type mentioned above. However, the earliest citation of it independently is in 1815, in the drama by Edward Hitchcock the Emancipation of Europe, or The Downfall of Bonaparte: Marshal Ney, no less, replies to a question from Talleyrand, no less, about how a battle went:

Oh most murderous! Too horrid to relate. Suffice to say Our troops are overwhelmed in toto.

The next example is from Around the Tea-Table (1847), by T. De Witt Talmage (now, there’s a moniker for you!), author, as his title page proclaims, of “Crumbs Swept Up,” “Abominations of Modern Society,” “Old Wells Dug Out,” Etc.

Perhaps it was gout, although his active habits and a sparse diet throw doubt on the supposition. Suffice to say it was a thorn — that is, it stuck him. It was sharp.

Five O���Clock Tea by American painter Julius LeBlanc Stewart (1855 ��� 1919)

“Suffice to Say”—a long-forgotten hit

Googling in connection with this topic, I discovered a 1977 hit by a band called The Yachts. Here are some of the lyrics:

Although the rhyming’s not that hot | It’s quite a snappy little tune | I’m sure you’ll like the chorus too | It’s short and sweet and to the point | It even says that I love you | Just after this: Suffice to say you love me | Can’t say that I blame you | Suffice to say I love you too

Clearly, leaving out it was necessary on rhythmical grounds. And if you want to relive your Punk days with this little ditty, here it is:

Filed under: Advice for writers, Confusable words, Meaning of words, Word origins Tagged: Subjunctive

March 3, 2015

National Grammar Day 2015

You mean you didn���t know?!? Well, neither did I, until Twitter alerted me a couple of years ago. Actually, it���s more an American than a British “thang”, started in 2008, by Martha Brockenbrough, founder of The Society for the Promotion of Good Grammar.

If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column, above the Twitter feed) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

What are we supposed to be celebrating?

Before you decide to run into the street dressed as a proper noun, abolish capitals forever like e.e. cummings, or construct grandiose, hugely baroque Dickensian periods��for your blog, it might be worth considering exactly what people mean by the word “grammar”. After all, it���s not a word that passes people���s lips that often. And those who do use it usually think it is going to the dogs.

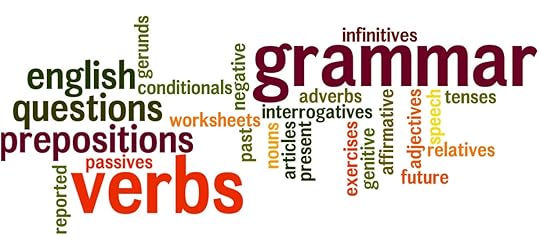

A technical definition

For linguists and grammarians, grammar is, broadly speaking, “the whole system and structure of a language“. Specifically, grammar usually narrows down to the rules governing how you combine words to make meaningful sentences, the inflections of words (e.g. is the past tense of dive dived or dove?, is the plural of consortium consortia or consortiums?), how verbs behave, what adverbials are, and the like, as illustrated in the graphic above. You will not find the writers of such eminently readable and practical tomes as the Collins Cobuild English Grammar sneering at someone’s spelling mistake and calling it a grammatical error.

A tortured grammarian pondering end-of-sentence prepositions. Well, St Jerome, actually, but he’ll do.

But for lay people (non-linguists), the term grammar is far from technical. Rather, it is just a ragbag into which they stuff any and every use of language which they object to (or should that be “to which they object”?).

What grammar is not

Most people cleave to the following definition of grammar: “A set of actual or presumed prescriptive notions about correct use of a language”.

And this definition seems to hold true for some editors and copy editors, whose livelihood, after all, depends on following and applying certain rules���sometimes regardless of whether those rules have any validity. Rules such as “which can only be used in non-defining relative clauses” or “it is incorrect to use they referring back to everyone“.

The linguistic definition of grammar, in fact, excludes most of the things that raise people���s blood pressure:

word choice

punctuation

capitalization

spelling

neologisms

slang

clich��

pronunciation

None of those are (is?) grammar.

Prescriptive grammar

The idea that they come under the umbrella of grammar corresponds to the different dictionary definition mentioned previously: “a set of actual or presumed prescriptive notions about correct use of a language”.

This interpretation of grammar as being about prescription has ��developed over centuries for many reasons, including as a way of marking social and group identity; of separating in-groups from out-groups.

A quotation from 1892 about aitch-dropping shows how rigorous such demarcations could–and can–be:

A very fine young man, but evidently a nobody, inasmuch as he dropped his aitches and so on.

This splendid-looking geezer was never invited to the smartest parties because ‘e dropped ‘is aitches something ruthless. Perhaps that explains the slightly affronted look.

It is reflected in the name of a slightly fascistic current book title��“I judge you when you use poor grammar“, which also has a Facebook group. In fact, most of the mistakes its members glote [sic] ��over are spelling mistakes or choices of the wrong word. This is also true of the Society for the Promotion of Good Grammar website, where we are implicitly invited to sneer at someone who wrote “distinguished the fire” instead of “extinguished the fire“, and similar catachreses (now, there’s a splendid word!). Sadly, this kind of ��pseudo-grammatical anality is on a par with the prejudices of those Southern Englishers who think that people with, for example, a Yorkshire accent are devoid of grey matter.

A healthful diet is good for you

To illustrate the arbitrary nature of some alleged grammar rules, let���s look at just one example of a use which– strangely, at least for a British audience–can give some American copy editors the screaming abdabs. Is it “good grammar” to talk of food, a diet, a lifestyle, as being healthy? Some intransigents and diehards insist that the correct word in those contexts is healthful.

The (false) reasoning behind this seems to be that if you define healthy as “in good health” it must, by definition, apply only to people. A turnip cannot–as far as we know, but then we don’t so far speak “turnip”, though perhaps HRH Prince Charles could interpret for us–enjoy rude good health, and therefore another word is required to denote “conducive to good health”. Enter healthful.

In fact, though healthful is the older word, healthy has been used to mean “conducive to good health” since the 16th century. The ban on it dates only to 1881, and has been passed down as an editorial meme ever since then. (Go here to hear the dulcet-toned Emily Brewster of ��Merriam-Webster��setting the record straight.)

The prescription totally ignores a productive feature of English: the transferred epithet��, which makes it possible, for example, to apply the word sad not merely to people who feel miserable, but also to the events which give them the blues in the first place. Countless other words behave in the same way; to make an exception of healthy is nonsensical and fetishistic. More to the point, and less emotively, it actually ignores the real “grammar” of English.��

The sage of Walden Pond

Back to grammar. As regards the second definition I mentioned, it���s worth quoting Thoreau, writing in 1862, when prescriptive grammar held sway:

When I read some of the rules for speaking and writing the English language correctly ��� I think ���

Any fool can make a rule

And every fool will mind it.

When it comes to the broader definition of “grammar” as our whole language system, we should certainly be celebrating the wonderful ingenuity of human and animal brains in developing it in the first place, and the thousands of ways in which it enriches our experience.

We should also celebrate the fact that all mother-tongue speakers know the grammar of their language, and use it correctly every time they utter, even if they can’t formulate its rules.

Filed under: Grammar, Meaning of words, Topical

February 21, 2015

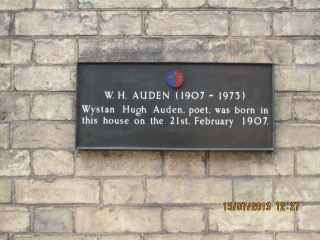

W.H. Auden: Happy (108th) Birthday!

As the great man was born on this day, 108 years ago, I couldn’t resist posting one of my favourite poems from his work.

I still remember how startled I was all those years ago – the early 1970s – when I turned a corner in Oxford and almost bumped into the owner of that famously lined reptilian face (“like a wedding cake left out in the rain”). He was going from the High Street into Radcliffe Square behind the University Church, shuffling along in his carpet slippers, his skin a spectral shade of grey. It must have been when Christ Church were putting him up, and therefore not that long before his death.

Mus��e des Beaux Arts

About suffering they were never wrong,

The old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position: how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along;

How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waiting

For the miraculous birth, there always must be

Children who did not specially want it to happen, skating

On a pond at the edge of the wood:

They never forgot

That even the dreadful martyrdom must run its course

Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot

Where the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer’s horse

Scratches its innocent behind on a tree.

In Breughel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

In a rather nice touch, York City Council commissioned a spiral pavement outside their headquarters in the converted old railway station, with the opening words of “As I walked out one evening…” on it.

The only image I can find online is this one, of its being built, and it doesn’t really do it justice. You look down on it from the pavement from where this photo must have been taken, and the words are easily legible. When I briefly stayed in York I used to walk past it practically every day, and it never failed to delight me.

And for a slightly chilling, unsettling experience, here is a recording of him reading and an animation of his face.

If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column, above the Twitter feed) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

Filed under: Poetry Tagged: W.H. Auden

February 16, 2015

Pancake Day: a pancake recipe linguistic

Butter…eggs…milk…flour…water…sugar…lemon. Those are the basic ingredients of and garnish for a pancake (thanks Delia!).

Simple, everyday words, but ones with complex histories that illustrate why English is such a succulent concoction of so many other languages.

If we look at where those words ultimately come from–simplifying considerably–what do we discover?

��� butter (Greek)

��� eggs (Old Norse)

��� milk, water (Germanic, Indo-European)

��� sugar, lemon (Arabic)

And if you also use syrup, that’s another word from Arabic.

Each has a curious story to tell.

(Flour��has too, but it���s a different tale: it���s a specialized spelling of flower.)

Let���s look at a couple of these words in more detail.

Fine words butter no parsnips

…but butter is essential to make the pancake batter (from French, btw).

How on earth did “butter” come all the way from Ancient Greece?

Like this. The Ancient Greeks seem not to have used butter for cooking, but they knew of its existence. The fifth-century (BCE) historian Herodotus wrote the earliest account, describing how ���the Scythians��poured the milk of mares into wooden vessels, caused it to be violently stirred or shaken  by their blind slaves, and thus separated the part that arose to the surface, which they considered more valuable and more delicious than that which was collected below it���.

by their blind slaves, and thus separated the part that arose to the surface, which they considered more valuable and more delicious than that which was collected below it���.

Hippocrates, the ���father of medicine���, he of the Hippocratic oath, also mentioned butter several times, and prescribed it externally as a medicine. He too described the Scythians making it, and wrote that they called it ���������������� (bouturon).

Folk etymology or loanword?

The 1888 OED entry states that this ���Greek [word] is usually supposed to be ��������� [bous] ox or cow + ���������� [turos] cheese, but is perhaps of Scythian or other barbarous origin.��� In other words, the derivation from Greek might be a folk etymology, and the Greek word might in fact be a loanword.

If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

What the Romans did with butter

Alma-Tadema’s soft porn masquerading as classicism. Exquisitely painted, though!

Greek ���������������� was borrowed by the Romans as butyrum. They, like the Greeks, did not use it in cooking either, but as an ointment in baths (yuck!) or for medicinal purposes, such as mixing it with honey to rub on mouth ulcers or to ease the pain suffered by teething infants.

Finally, the word reaches Britain

Old English had borrowed it at least by the year 1000 CE, when it appears in Anglo-Saxon medicine in the form butere as a remedy for swellings or boils, mixed (if I���ve translated correctly) with pounded yarrow.

English is technically a ���West Germanic��� language, and its cousins German, Frisian and Dutch all also borrowed the word for “butter” from Latin, which is why the modern German is butter, and the Dutch boter.

Beware of Vikings bearing eggs

Another of the ingredients of current English is Old Norse words brought over by the Vikings during their incursions (I choose my word carefully) ��into the British Isles and Ireland from the late eighth century onwards.

Many of them are basic to our vocabulary: words to do with the body, such as ankle, calf, freckle, scab and skin; or basic verbs such as get, give, take and want. These words often replaced earlier Old English words, and **egg is a Norse interloper��(the -loper part of which is from Dutch).

The older word was **ey, (plural eyren) derived from Old English ��g. It seems that the two different words were used concurrently, but by people from different parts of Britain.

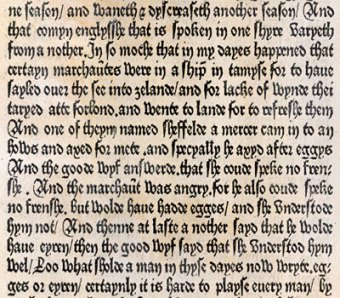

One of the best-known illustrations (or “iconic moments“, if you want to be kitschy) of the history of English concerns these lexical twins.

In his prologue to his translation of The boke yf Eneydos… translated oute of latyne in to frenshe, and oute of frenshe reduced in to Englysshe by me Wyllm Caxton (i.e. a paraphrase of what we know as Virgil���s Aeneid), Caxton wrote:

Loo, what sholde a man in thyse dayes now wryte, egges or eyren? Certaynly it is harde to playse every man by cause of dyversite & chaunge of langage.

(What should a man in these days now write, egges or eyren? Certainly it is hard to please every man because of the diversity of and change in language.)

Caxton was echoing the uncertainty about how to write words at a time when English spelling was becoming a very pressing issue because of the spread of printed books. Dialects within Britain varied far more than they do today, and for Caxton it was important to choose words and spellings that would be understood by as many people as possible.

His remark follows a piquant story

Some merchants–presumably from the north of England, since one is called Sheffield–being becalmed on the Thames and unable to set sail for Holland, want to have something to eat and try to buy eggs from a woman dahn sahf (down south).

The merchants use the Norse and northern English version egges; she uses the southern version eyren. She either was unable to understand, or, like a typical southerner today, decided to wind up the northerner by pretending not to. She added insult to injury by taking him for that worst of all things…a Frenchman!

And that comyn Englysshe that is spoken in one shyre varyeth from a nother…And specyally he axyed after eggys. And the good wyf answerde that she coude speke no frenshe. And the marchaunt was angry for he also coude speke no frenshe but wold haue hadde egges and she understode hym not. And thenne at laste a nother sayd that he wolde haue eyren. Then the good wyf sayd that she understood hym wel.

(Modern English version at the end of the blog.)

What about pancake?

Simples! It���s a straightforward, Middle English combination of pan (related to German Pfanne, and perhaps also ultimately from Latin) + cake (again, like egg, from Scandinavia).

**The Old Norse is echoed in the modern Scandinavian languages: Icelandic & Norwegian egg, Swedish ��gg, Danish ��g; the Middle English ey(e) in modern German and Dutch ei.

In present day English:

“And that common English that is spoken on one shire differs from another…And he asked specifically for eggs, and the good woman said that she spoke no French, and the merchant got angry for he could not speak French either, but he wanted eggs and she could not understand him. And then at last another person said that he wanted “eyren”. Then the good woman said that she understood him well.”

Filed under: Dictionaries & Lexicography, Meaning of words, OED, Word Histories Tagged: Around the world in 80 words

February 9, 2015

National umbrella day: a Latin word borrowed by English

Every February 10 marks this ���national day��� that probably passes most people by. But it���s a useful opportunity for umbrella manufacturers, wholesalers and retailers (umbrellists?) to market their wares and trumpet their amazing usefulness.

If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

In Britain, and even more so in Scotland, where I live, an umbrella is an absolute necessity–preferably a golf umbrella, or one of the same size. But even they often buckle or blow inside out when the cruel Scottish wind gets into a temper.

Never mind. It���s remarkable how the word for this everyday object, to which we probably don���t give too much thought as long as it functions effectively, goes all the way back to one of the languages from which, more than almost any other, English has ���borrowed���, namely Latin.

How so?

As concisely and accurately as I can tell it, the story goes something like this:

The Latin word for ���shade��� or ���shadow��� is umbra.

(That���s the word, incidentally, from which ultimately we also get the expression ���to take umbrage���. Not to mention the botanical umbels, the shadowy��penumbra, and the highly formal verb to adumbrate.)

Allium umbels

But, lest I’m tempted to digress further, let���s get back to the main plot.

The diminutive form of umbra in Latin was umbella, meaning a parasol or sunshade, and the word was already in existence in the 1st century CE. (It���s only our dreich climate that makes us inevitably associate umbrellas with rain rather than sun; think magnificent Indian rajahs riding an elephant and protected by a sunshade).

In Late Latin, the letter r of the base word umbra was reinserted into um[]bella to give umbrella.

Meanwhile, Latin umbra became **ombra in Italian, which, together with the diminutive suffix, became ombrella or ombrello.

From there it passed into French, which is, apparently, the language from which we most immediately borrowed it, in the early 17th century.

(Which leaves me wondering what people did before then; life must have been so utterly miserable when it rained).

(I’ve also blogged about English words borrowed from Spanish, Norwegian, Afrikaans and Egyptian.)

Some delightful early quotes

The OED lists several spellings, as almost invariably happens with loanwords. The main variants are the one that has become standard, umbrella (1609), umbrello (1611) and ombrella (before 1630).

I’ve put below some quotes in the OED that caught my eye:

From an early bilingual lexicographer, Randle Cotgrave, in his dictionarie of the French and English tongues (1611):

Ombrelle, an Vmbrello; a (fashion of) round and broad fanne, wherwith the Indians (and from them our great ones) preserue themselues from the heat of a scorching Sunne.

From the remarkable Somersetian writer and traveller Thomas Coryate, responsible, according to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, for the first use of the word in English literature, here describing how Italians shielded themselves from the sun in his Crudities (which means here “undigested snippets”; 1611):

Many of them doe carry other fine things…, which they commonly call in the Italian tongue vmbrellaes…These are made of leather something answerable to the forme of a little cannopy & hooped in the inside with diuers little wooden hoopes that extend the vmbrella in a prety large compasse.

And John Donne, using the word as a metaphor, written in 1609, but not published until 1633:

We have an earthly cave, our bodies to go into by consideration, & coole our selves: and…wee have within us a torch, a soule, lighter and warmer then any without: we are therefore our owne umbrellas, and our owne Suns.

Then poet John Gay, he of The Beggar���s Opera, from Trivia (1716):

Good houswives…underneath th’Umbrella’s oily Shed,

Safe thro’ the wet on clinking Pattens tread.

Finally, from the ���Sage of Concord���, Emerson, commenting on those strange people, the English, in English Traits (1856):

An Englishman walks in a pouring rain, swinging his closed umbrella like a walking-stick.

Keeping dry in other languages

The modern French for umbrella is parapluie, the first part being borrowed from Italian words, and conveying the idea of protection, the second being the word for…rain. A similar combination of ideas gives German Regenschirm (literally ���rain screen��� ). The modern Greek is simply ��������������, (transliterated letter by letter = omprela).

From Mary Poppins to Rihanna

[image error](or should that read from innocence to sexperience?)

Squeaky clean Mary Poppins��� miraculous flying umbrella had a parrot-head handle. Rihanna���s does not, but what she does with the umbrella could certainly make your head spin.

It���s noticeable, by the way, how she gives the word four syllables ��� um-buh-rel-luh ��� for the sake of the rhyme, in a linguistic process that goes by the name of anaptyxis.

Happy umbrella day! ��I hope nobody rains on your parade. Or, that if they do, you have an umbrella to hand.

(If you’d prefer something a bit more melodic on the theme of shade, you might like Handel’s celebrated and sublime aria Ombra mai fu, sung by the sublime Janet Baker.)

** Early in Canto I of the Inferno, as he starts on his journey, Dante asks Virgil who he is, using the word ombra:

Quando vidi costui nel gran diserto,

��Miserere di me��, gridai a lui,

��qual che tu sii, od ombra od omo certo!��.

Rispuosemi: ��Non omo, omo gi�� fui,

e li parenti miei furon lombardi,

mantoani per patr��a ambedui.��

When I beheld him in the desert vast,

“Have pity on me,” unto him I cried,

“Whiche’er thou art, or shade or real man!”

He answered me: “Not man; man once I was,

And both my parents were of Lombardy,

And Mantuans by country both of them.���

(I don’t know who this translation is by so can’t credit is as I should.)

Filed under: Dictionaries & Lexicography, Meaning of words, OED, Word Histories Tagged: Around the world in 80 words, Latin

February 5, 2015

Forecast or forecasted? Broadcast or broadcasted?

(that���s Scots for takeaway).

Both are correct, but the irregular form is much more common than the regular one; ��the regular form forecasted seems to be more often used in American English than in other varieties.

If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

The other day I was checking my fuel bills online, thanks to the wonders of the Interweb (I live in Scotland; it���s cold, and heating bills are painfully high). One of the graphs helpfully provided by the energy supplier contrasts “forecasted usage” with actual usage. That���s right, forecasted��usage.

That set me thinking about that minuscule set of verbs whose past tense forms (simple past and participle) can be either regular or irregular:

��� broadcast(ed)

��� forecast(ed)

��� input(ted)

��� output(ted)

��� offset(ted)

��� podcast(ed)[image error]

(I’ve left out cast and cost, which raise different issues).

In online forums (or fora, if you���d prefer; I certainly don���t), people ask which is the correct form, i.e. forecast or forecasted. This is one of those fairly rare instances in English verb morphology��to which the answer is ���both���.

But, as usual when it comes to English usage, there are some ifs and buts.

Before we look at those ifs and buts, though, it might be worth trying to find out why these two different options exist in the first place.

Take Our Poll

New verbs are always regular

Of course, many of the most common verbs in English are irregular (e.g. bring, forget). But regular verbs far outnumber them, though they may not outweigh them in frequency.

(Just to remind ourselves, regular verbs just add -ed or -d to their base form, e.g. talk => talked, for past tense forms, sometimes with spelling modifications, e.g. try => tried.)

Any newly invented verb should��automatically follow this pattern. Lewis Carroll famously made use of this rule in Jabberwocky with the word he invented that is now part of English:

���And hast thou slain the Jabberwock?

Come to my arms, my beamish boy!

O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay!���

He chortled in his joy.

(He also playfully invented an irregular verb as well, but that���s another story: ���Twas brillig, and the slithy toves | Did gyre and gimble in the wabe: | All mimsy were the borogoves, | And the mome raths outgrabe (from to outgribe).

Verbs from nouns always…

follow the regular pattern almost without exception, in the process known as verbing (the possible and controversial exception being text).

Stephen Pinker (The Language Instinct, p. 380 ) states, having ��proved it experimentally, ��that verbs derived from nouns are filed in a different part of the mental lexicon from verbs derived from verbs; contrast outshone [from verb] with grandstanded [from noun, and not *grandstood]).

In fact, this pattern is so firmly imprinted in our internal grammars as a basic process that if I were now to ask you to make the invented noun flixxle (= a panicky attack of fidgeting) into a verb, you would automatically know how to do so. Ditto for verbing the noun bafflegab���but don���t forget to double the final -b!

The verbs we���re looking at can be irregular or regular

All, obviously, contain an irregular verb as their second element: cast, put, and set.

Their alternative forms reflect two different and conflicting analyses. If we mentally analyse them as deriving from a noun, they are regular; but if we analyse them as based on the irregular verb within them, their past tense forms will also be irregular. On the whole, the influence of their verb affix prevails.

People subconsciously analyse them in different ways, which explains online bewilderment such as:

“I am having a problem with the word offset. This is what I’m going to type to my vendor:

If we do not receive your Statement of Account by 30 Mar ’12, all payments will be ‘offsetted’.

Is it OK to use offsetted in this sentence?”

Most dictionaries show both forms for most of these verbs; Collins is the only one I know of to show podcasted. Incidentally, the WordPress spellchecker flags up the -ed forms.

As long ago as 1926, Fowler in Modern English Usage made the verb from verb/verb from noun distinction with forecast, but brought in historical etymology to justify his aesthetic preference: “Whether we are to say forecast or forecasted…depends on whether we regard the verb or the noun as the original from which the other is formed…The verb is in fact recorded 150 years earlier than the noun, & we may therefore thankfully rid ourselves of the ugly forecasted ; it may be hoped that we should do so even if history were against us, but this time it is kind.”

Conclusion

You can’t go wrong if you use the irregular (i.e. shorter) form in all contexts. If you use the regular form, some people may find it rather odd, question it, or even dismiss it as “wrong”.

Ifs and buts

(if you want some more analysis)

I wondered if different forms might be used with different syntax and/or meaning, e.g. attributive vs predicative, or past tense vs past participle.

I suppose there is no obvious reason for these verbs all to behave in the same way, and a brief analysis of three of them shows that indeed they don���t.

A rough-and-ready analysis of the March 2013 build of the Oxford English Corpus provides the following figures:

broadcast vs broadcasted : as the past tense 2,160 vs 465, or 82% vs 18% of all occurrences of the past tense. That means that broadcasted occurs more often in percentage terms compared to broadcast than forecasted does to forecast.

When it comes to the past participle, the tagging of the data meant that broadcasted could not be retrieved in its own right. However, the string BE + broadcasted within a five-word span, in other words passive use of the verb, accounted for roughly 40% of all occurrences of the form broadcasted. In contrast, there was not one single occurrence of broadcast in a passive construction. This suggests that there could be a marked syntactic differentiation between the two forms of the participle. The figures do not suggest that this passive use is specifically American.

As regards offset , the corpus yielded only two occurrences of offsetted against 461 of offset as past and past participle.

However, a Google search reveals (apart from dictionary entries and queries over which is the correct form) that offsetted appears mostly in contexts of geometric modelling and accounting, and occasionally in relation to emissions offsetting, e.g. Leaving on a carbon-offsetted jetplane! (obviously referring to the well-known song).

Finally, forecast vs forecasted for all uses = 3,394 vs 360, or 90% vs 10% with roughly the same relative distribution of the forms applying both to past tense and participle.

The data also suggests that forecasted may be more common in American English than in British, particularly as a past participle.

Unlike broadcasted, however, there are very few passive uses of forecasted.

Filed under: Advice for writers, Dictionaries & Lexicography, Grammar, Writing Skills

January 23, 2015

Iconic: is totemic the new iconic?

Totemic might be a modish choice to replace the overused and much maligned iconic, but it is still rather rare in comparison.

(If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!)

Iconic: a massively overused word?

On 20 January, that universal pundit Stephen Fry tweeted: ���How would it be if there were a media-wide moratorium on the use of the word ���iconic��� for the next ten years? Just a suggestion.���

I���m sure many would second his suggestion.

But in any case, it seems that a minority are voting with their tongues and using a different mot du jour instead: totemic.

(I’ll deal with whether they mean the same in a future blog.)

Totems and totemic

A Facebook friend alerted me a few months ago to what he thought was the irresistible rise of this adjective and the noun it derives from, totem.

So, it was perhaps unsurprising to find, amid the typical luvvie blether so aptly parodied in Private Eye, Benedict Cumberbatch���s description (Radio Times, 15-21 November 2014) of the martyred Alan Turing:

“He wasn���t someone who purposefully [sic] put himself in the way of things as a protest ��� he was just a great role model for anyone who���s different or feels different…And even as his body was morphing he was doing work on how the environment causes cellular structures to change. I mean, God knows, he probably would be celebrated as someone like Bill Gates. Without a doubt, he would be held as a totem of the modern world.”

Not just an icon, mark you, oh, no, sirree! A very totem. And then, blow me, if in Melvyn Bragg���s recent (and very informative) programme about the legacy of Magna Carta on January 8, 2015 the two words, the jaded, raddled clich�� and the not-yet-but-give-it-time-and-it-will-be clich�� were metaphorically squaring up to each other in a sort of modern logomachy.

(See further down for a transcript of the relevant sections: totem / totemic / icon / iconic each appear once).

Totemic may be on the rise: only time will tell. However, for the moment it is still rather unusual. In the Oxford English Corpus it is outnumbered getting on for 20 times by iconic. And in fact they share only two noun collocations: status and figure (in ratios of 53:1 and 14:1 respectively). Also, totemic figure [image error]as often refers literally to artistic works having some affinity with totems as it does metaphorically to people who symbolize something.

On Google, a comparison of the exact string ���iconic figure��� accentuates the difference in numbers: 643,000 against 11,000. And again, totemic figure is often literal.

Totemic, then, looks like a word to watch: it has not yet been adulterated by massive overuse, but, by the same token, is still nowhere near to being as often used as its rival.

Transcripts

On the one hand, the noble Lord referred to Magna Carta as follows (about 2 minutes in):

���…It is radical in the way it has been used in innumerable rebellions, uprisings and movements to demand freedom…The original was stuffed with laws about fisheries in the Thames, about foreign immigrants and widows��� rights. At first sight it seems strange that such a document could turn into the great totem of individual liberty.���

Responding to Lord B���s introduction, Professor Nicholas Vincent, a leading Magna Carta scholar from the University of East Anglia (UEA), then says:

���A lot of it increasingly became rather archaic…financial stipulations don���t really bear much relation to reality even by the late thirteenth century. But those totemic clauses, the clauses about sale of justice, denial of justice, right to free judgement, right to judgement by the law of the land, all of those retain their significance.���

Later in the programme, another scholar, Professor Justin Champion, of Royal Holloway, of the University of London, uses the i-word.

Lord B (9.50 minutes in):

“It���s been suggested…There are 63 chapters or statutes or clauses in the original Magna Carta and only a couple are still on the statute book, and therefore its significance is, in today���s world, largely symbolic. What���s your view on that, Justin?”

Professor Champion:

“I think the word symbolic is somehow a bit weak. It���s [slight pause] it���s iconic. And in one respect it doesn���t really matter that precise elements of the clauses have been suspended or transcended because the core principles are concepts, they���re ideas…���

And then further in, the word icon makes an appearance on the lips of journalist and MEP Daniel Hannan (about 17.30 minutes in):

“It became very fashionable in Britain in the twentieth century to debunk all historical icons, and to say ‘Oh, this is all reinvented’, and so on. US historiography didn’t go through that to anything like the same extent.”

(For a bit of light relief, go to about 26.45 minutes in to hear Tony Hancock���s take on Magna Carta.)

Filed under: Dictionaries & Lexicography, Meaning of words, Word Histories Tagged: Benedict Cumberbatch

December 11, 2014

Elusive or illusive or allusive?: 20 words not to confuse (17-18)

Beware of accidentally writing illusive when you mean that something or someone is hard to find, pin down, or define. The correct word and spelling are��elusive.

Correct: Yet happiness is an elusive concept, rather like love.���OEC, 2002;

Incorrect: Sharks up to forty feet are quite common, although when Helen was there they proved to be X��illusive.���OEC, 2005.

If you use Word, the spelling and grammar check will come to your rescue by querying��illusive.��

If you want to suggest that something is an illusion, illusory is much more frequent than illusive, and a safer choice (readers will be in no doubt about what you mean to say):

Correct: …a Buddhist monk advised him, ���You must first realize the illusory nature of your own body���.���OEC, 2003.

In written texts, X illusive is more often used by mistake than in its true meaning, though many examples are ambiguous.

The word allusive is also occasionally used by mistake for elusive.

If you feel confident that you already know all this, why not try the fun test at the bottom of the blog?

For more detail, read on…

(If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!)

Why does the mistake happen?

The reason is obvious: the words sound exactly the same: i-l(y)oo-siv (/����l(j)u��s��v/.) If you don���t edit your writing carefully the mistake could slip through, because, depending on your spellchecker, it might accept illusive as a legitimate word. Which it is, but, very often, probably not the one you meant!

What is the difference?

Elusive…

relates to the verb ���to elude���. So, something elusive eludes or escapes you, is difficult to grasp physically or mentally.

A classic example is from that golden oldie by Bob Lind, Elusive Butterfly:

Across my dreams, with nets of wonder,

I chase the bright, elusive butterfly of love.

Things that tend to be elusive are creatures, foes, beasts…and Justin Timberlake.  If people describe him as elusive, that means he is hard to track down and photograph or interview; if they were chasing the��illusive Justin Timberlake, they would presumably be implying something about his very existence, or about his skill at creating illusions.

If people describe him as elusive, that means he is hard to track down and photograph or interview; if they were chasing the��illusive Justin Timberlake, they would presumably be implying something about his very existence, or about his skill at creating illusions.

If people describe a concept as elusive, they mean it is hard to pin down, explain, or define; if they describe it as X illusive, they may possibly mean that it is indeed an illusion, but as often as not it seems to be an inappropriate word choice. In the next example the appropriate word has been used:

If the situation in western Pakistan continues to deteriorate, success will be elusive and very difficult to achieve.���OEC, 2009.

What about illusive?

It means, as the Collins Dictionary puts it, ���producing, produced by, or based on illusion; deceptive or unreal���. [image error]It has a rather literary ring to it, as in Sir Walter Scott���s:

���Tis now a��vain illusive show,

That melts whene’er the sunbeams glow.

Modern examples include:

…a film essay about the real and illusive nature of motion pictures.���Senses of Cinema, 2002

(after all, films produce an illusion in the mind of the viewer);

Gaskell [i.e. Mrs Gaskell, the novelist] did not sentimentalize or yield to the illusive attractions of the English pastoral idyll.���Criticism, 2000

(the attractions were indeed an illusion, since country life was harsh and poverty-stricken).

Illusive by mistake

However, the data in the Oxford English Corpus demonstrate how often illusive appears by mistake for elusive. A roughly 10-per cent sample (50 examples) of all occurrences contained 23 in which illusive was clearly a mistake:

…but even after a decade, his [i.e. Ricardo Chailly���s] musical character remains strangely X illusive and lacking any special definition.���New York Metro, 2004

(the intended meaning must be ���hard to define��� and therefore should be��elusive);

During the long period we spent waiting for this X��illusive good weather, there was also tragedy on the mountain���Everest Expedition dispatches, 2003

(my reading is that the good weather came only sporadically, but the sentence is conceivably ambiguous).

Of the other 28 examples, only 12 unequivocally used���at least by my reading���the true meaning of the word:

The New World Order thus created a common interest binding the ruling classes all over the world. With distressing rapidity, through misperception, deception, corruption, or with coercion, this illusive common interest, this notion of shared stakes encompassed the whole world and large majorities in almost every society .���Free India Media, 2004

(the left-leaning nature of the text suggests that common interest between the ruling classes and the ruled is indeed an illusion).

But 15 were ambiguous to me, and in some cases it was impossible to work out quite what the writer intended:

After a troubled season at Arsenal, Bergkamp was his illusive best on Friday night, dropping off Kluivert and playing a part in almost all of Holland’s better moments.���Sunday Herald, 2000

Was Bergkamp hard to pin down and tackle, or a master of illusion through feints?

illusive/illusory

Illusory has the same definition as illusive. According to the OED, it was first recorded in a letter of 1599 by no less a personage than Elizabeth I (though it looks like a noun),  and then by John Donne.

and then by John Donne.

To trust him uppon pledges is a meare illusorye.���1599

A false, an illusory, and a sinfull comfort.���Sermons, X.51, before 1631

Illusive appeared nearly a century later (1679) according to the OED, in the blood-curdlingly titled The narrative of Robert Jenison, containing 1. A further discovery and confirmation of the late popish plot. 2. The names of the four ruffians, designed to have murthered the king…

Which is it better to use?

If you really mean to convey the idea that something is an illusion, I’d be tempted to go for illusory, as the more common word, and in order to dispel any suspicion that you meant elusive. In the OEC it is roughly eight times more frequent that illusive:

���…they give the Palestinians the illusory feeling that via a unilateral strategy and parliamentary resolutions they can obtain their political aspirations,��� foreign ministry spokesman Emanuel Nachshon told The Irish Times���10 December, 2014.

So that���s that all sorted out, then

If only… Another word (a near homophone) sometimes gets snarled up in this tangle of meaning. It is allusive, the adjective corresponding to ���allusion��� and used mainly by literary critics, film critics, and the like. Some poetry, such as T.S. Eliot���s The Waste Land, is highly allusive, since it constantly alludes (i.e. refers indirectly) to other texts, poetic or otherwise.

Although there is no question that Ulysses provided a supreme example of the allusive method in action, deployed on a breathtaking scale, Eliot���s almost insatiable appetite for allusion sprang from other sources as well.���T.S. Eliot: The Modernist in History, ed. Ronald Bush, 1991

But people occasionally use it by mistake. I heard the pronunciation ���allusive��� referring to whales in a recent BBC trailer for a nature programme. And if you search for ���The Allusive Butterfly of Love��� online you will find quite a few examples.

More mistaken examples:

Picking up a taxi from Epping tube station, it was another half an hour finding the X allusive final destination.���Ideas Factory, 2004

Give John Kerry this. He’s maddeningly X allusive ���OEC, 2004

Given the prevailing muddle over the meaning of these words, it is perhaps not surprising that one has to turn to literary titans to see them used with absolute precision: at a conference in August 2004, Vikram Seth memorably and alliteratively defined writing as ���allusive, elusive and illusive���.

Fun test

Choose between allusive, elusive, and illusory:

Although his restless experimentation and complex,��_________��style often prove difficult on first reading, his novels possess a complexity and depth that reward the demands he makes upon his readers.

Dylan is notoriously��_________; as he wrote on the album notes to Highway 61 Revisited , “there is no I���there is only a series of mouths .”

The hint that the possibility exists for real and not _________ happiness and love appears fleetingly in a few of Sirk’s earlier Universal-International films.

...the Convention is interpreted and applied in a manner which renders its rights practical and effective, not theoretical and _________.

But in one area, success is��_________: The city’s rats remain as bold and showy as ever, darting through well-lighted subway stations as…

1. allusive 2. elusive 3. illusory 4. illusory 5. elusive

Filed under: Advice for writers, Confusable words, Dictionaries & Lexicography, Grammar, Meaning of words, Writing Skills

elusive or illusive or allusive?: 20 words not to confuse (17-18)

Beware of accidentally writing illusive when you mean that something or someone is hard to find, pin down, or define. The correct word and spelling are elusive.

Correct: Yet happiness is an elusive concept, rather like love.—OEC, 2002;

Incorrect: Sharks up to forty feet are quite common, although when Helen was there they proved to be X illusive.—OEC, 2005.

If you use Word, the spelling and grammar check will come to your rescue by querying illusive.

If you want to suggest that something is an illusion, illusory is much more frequent than illusive, and a safer choice (readers will be in no doubt about what you mean to say):

Correct: …a Buddhist monk advised him, “You must first realize the illusory nature of your own body”.—OEC, 2003.

In written texts, X illusive is more often used by mistake than in its true meaning, though many examples are ambiguous.

The word allusive is also occasionally used by mistake for elusive.

If you feel confident that you already know all this, why not try the fun test at the bottom of the blog?

For more detail, read on…

(If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!)

Why does the mistake happen?

The reason is obvious: the words sound exactly the same: i-l(y)oo-siv (/ɪˈl(j)uːsɪv/.) If you don’t edit your writing carefully the mistake could slip through, because, depending on your spellchecker, it might accept illusive as a legitimate word. Which it is, but, very often, probably not the one you meant!

What is the difference?

Elusive…

relates to the verb “to elude”. So, something elusive eludes or escapes you, is difficult to grasp physically or mentally.

A classic example is from that golden oldie by Bob Lind, Elusive Butterfly:

Across my dreams, with nets of wonder,

I chase the bright, elusive butterfly of love.

Things that tend to be elusive are creatures, foes, beasts…and Justin Timberlake.  If people describe him as elusive, that means he is hard to track down and photograph or interview; if they were chasing the illusive Justin Timberlake, they would presumably be implying something about his very existence, or about his skill at creating illusions.

If people describe him as elusive, that means he is hard to track down and photograph or interview; if they were chasing the illusive Justin Timberlake, they would presumably be implying something about his very existence, or about his skill at creating illusions.

If people describe a concept as elusive, they mean it is hard to pin down, explain, or define; if they describe it as X illusive, they may possibly mean that it is indeed an illusion, but as often as not it seems to be an inappropriate word choice. In the next example the appropriate word has been used:

If the situation in western Pakistan continues to deteriorate, success will be elusive and very difficult to achieve.—OEC, 2009.

What about illusive?

It means, as the Collins Dictionary puts it, “producing, produced by, or based on illusion; deceptive or unreal”.  It has a rather literary ring to it, as in Sir Walter Scott’s:

It has a rather literary ring to it, as in Sir Walter Scott’s:

’Tis now a vain illusive show,

That melts whene’er the sunbeams glow.

Modern examples include:

…a film essay about the real and illusive nature of motion pictures.—Senses of Cinema, 2002

(after all, films produce an illusion in the mind of the viewer);

Gaskell [i.e. Mrs Gaskell, the novelist] did not sentimentalize or yield to the illusive attractions of the English pastoral idyll.—Criticism, 2000

(the attractions were indeed an illusion, since country life was harsh and poverty-stricken).

Illusive by mistake

However, the data in the Oxford English Corpus demonstrate how often illusive appears by mistake for elusive. A roughly 10-per cent sample (50 examples) of all occurrences contained 23 in which illusive was clearly a mistake:

…but even after a decade, his [i.e. Ricardo Chailly’s] musical character remains strangely X illusive and lacking any special definition.—New York Metro, 2004

(the intended meaning must be “hard to define” and therefore should be elusive);

During the long period we spent waiting for this X illusive good weather, there was also tragedy on the mountain—Everest Expedition dispatches, 2003

(my reading is that the good weather came only sporadically, but the sentence is conceivably ambiguous).

Of the other 28 examples, only 12 unequivocally used—at least by my reading—the true meaning of the word:

The New World Order thus created a common interest binding the ruling classes all over the world. With distressing rapidity, through misperception, deception, corruption, or with coercion, this illusive common interest, this notion of shared stakes encompassed the whole world and large majorities in almost every society .—Free India Media, 2004

(the left-leaning nature of the text suggests that common interest between the ruling classes and the ruled is indeed an illusion).

But 15 were ambiguous to me, and in some cases it was impossible to work out quite what the writer intended:

After a troubled season at Arsenal, Bergkamp was his illusive best on Friday night , dropping off Kluivert and playing a part in almost all of Holland ‘s better moments.—Sunday Herald, 2000

Was Bergkamp hard to pin down and tackle, or a master of illusion through feints?

illusive/illusory

Illusory has the same definition as illusive. According to the OED, it was first recorded in a letter of 1599 by no less a personage than Elizabeth I (though it looks like a noun),  and then by John Donne.

and then by John Donne.

To trust him uppon pledges is a meare illusorye.—1599

A false, an illusory, and a sinfull comfort.—Sermons, X.51, before 1631

Illusive appeared nearly a century later (1679) according to the OED, in the blood-curdlingly titled The narrative of Robert Jenison, containing 1. A further discovery and confirmation of the late popish plot. 2. The names of the four ruffians, designed to have murthered the king…

Which is it better to use?

If you really mean to convey the idea that something is an illusion, I’d be tempted to go for illusory, as the more common word, and in order to dispel any suspicion that you meant elusive. In the OEC it is roughly eight times more frequent that illusive:

“…they give the Palestinians the illusory feeling that via a unilateral strategy and parliamentary resolutions they can obtain their political aspirations,” foreign ministry spokesman Emanuel Nachshon told The Irish Times—10 December, 2014.

So that’s that all sorted out, then

If only… Another word (a near homophone) sometimes gets snarled up in this tangle of meaning. It is allusive, the adjective corresponding to “allusion” and used mainly by literary critics, film critics, and the like. Some poetry, such as T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, is highly allusive, since it constantly alludes (i.e. refers indirectly) to other texts, poetic or otherwise.

Although there is no question that Ulysses provided a supreme example of the allusive method in action, deployed on a breathtaking scale, Eliot’s almost insatiable appetite for allusion sprang from other sources as well.—T.S. Eliot: The Modernist in History, ed. Ronald Bush, 1991

But people occasionally use it by mistake. I heard the pronunciation “allusive” referring to whales in a recent BBC trailer for a nature programme. And if you search for “The Allusive Butterfly of Love” online you will find quite a few examples.

More mistaken examples:

Picking up a taxi from Epping tube station, it was another half an hour finding the X allusive final destination.—Ideas Factory, 2004

Give John Kerry this. He’s maddeningly X allusive —OEC, 2004

Given the prevailing muddle over the meaning of these words, it is perhaps not surprising that one has to turn to literary titans to see them used with absolute precision: at a conference in August 2004, Vikram Seth memorably and alliteratively defined writing as “allusive, elusive and illusive”.

Fun test

Choose between allusive, elusive, and illusory:

Although his restless experimentation and complex, _________ style often prove difficult on first reading, his novels possess a complexity and depth that reward the demands he makes upon his readers.

Dylan is notoriously _________; as he wrote on the album notes to Highway 61 Revisited , “there is no I—there is only a series of mouths .”

The hint that the possibility exists for real and not _________ happiness and love appears fleetingly in a few of Sirk’s earlier Universal-International films.

...the Convention is interpreted and applied in a manner which renders its rights practical and effective, not theoretical and _________.

But in one area, success is _________: The city’s rats remain as bold and showy as ever, darting through well-lighted subway stations as…

1. allusive 2. elusive 3. illusory 4. illusory 5. elusive

Filed under: Advice for writers, Confusable words, Dictionaries & Lexicography, Grammar, Meaning of words, Uncategorized, Writing Skills

December 8, 2014

To defuse or diffuse a situation?: 20 words not to confuse (19-20)

[19-20 of 20 words good writers shouldn���t confuse]

Poll results as of 29 December:

Leave as is=7

Change to defuse=41

Consult writer=8

Use another verb=7

Wouldn’t notice it as issue=2

What���s the issue?

In a sentence such as

She is coping because she has learned that forgiveness is the only way to diffuse ire and hatred

Birmingham Evening Mail, 2007

is diffuse a mistake for defuse?

Most dictionaries do not accept this use of diffuse, but Cobuild does, presumably, as an impeccably corpus-based venture, after having examined the evidence of actual use.

The Online Oxford Dictionary has a usage note (discussed later on); and the Cambridge Guide to Modern English Usage considers that when it comes to emotions (for example, as in the sample sentence above), the two distinct verbs overlap and converge.

(If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!)

What does each word ���mean���?

defuse: literally

In its literal meaning (sort of obviously, because it consists of the prefix de- + fuse (noun)), defuse means ���to remove the fuse of an explosive device in order to prevent it from exploding���:

Explosives specialists tried to defuse the grenade;

The device was defused by police bomb disposal experts.

…and metaphorically

in its literal sense, according to the OED, it’s a relative newcomer (1943). As a metaphor (1958), it refers to making a situation less dangerous or volatile. In other words, a situation is conceived of as something explosive, like a bomb. Things that people typically defuse (noun objects of the verb) are situation(s), crisis/crises, tension(s), anger, conflict(s), row(s):

With a joke and a smile he was able to defuse many a tense situation and his presence in any room was unmistakable;

Now he is trying to defuse the crisis that the warmongers have created;

Their diplomacy has been aimed at defusing conflict between the North and the South [sc. Korea].

But defuse has a near-homophone. It is, of course, the verb diffuse. The only thing that distinguishes it from defuse in speech is that its first vowel is a short i /d����fju��z/ contrasting with the long i of /di:��fju��z/, rhyming with tea.

Are they synonyms?

In their core meanings, it seems hard to argue that they are.

diffuse: core meanings

Simplifying its meanings considerably (I hope you���ll allow the unattached participle), if something diffuses, it spreads, and if you diffuse it, you spread it, e.g. information diffuses and you can diffuse it.

(Because the subject of the intransitive use can be the object of the transitive, it falls into the class of verbs classified as ergative. The fullest explanation of the verb���s syntax is in the Cobuild Dictionary).

What diffuses / is diffused can be abstract or concrete, and in the latter case it has a specific physical meaning when light is involved: “to cause light��to spread evenly��to reduce glare��and harsh��shadows”, e.g. The morning light was diffused to a mucky orange by the pollution of the shuddering city.

Further examples

(From Cobuild and the Online Oxford Dictionary)

Intransitive

His heart sank, fear spread and diffused through his body;

Technologies diffuse rapidly.

Transitive

The problem is how to diffuse power without creating anarchy;

an attempt to diffuse new ideas;

It works efficiently to create and diffuse purchasing power throughout the economy and disseminate liquidity throughout the financial system.

Where is the overlap?

One quite often comes across sentences using diffuse with nouns which seem more appropriate to defuse, both in its literal���bomb, explosive���and metaphorical meanings���crisis, situation, tension, anger, conflict. Are these mistakes, or legitimate extensions of meaning and collocation?

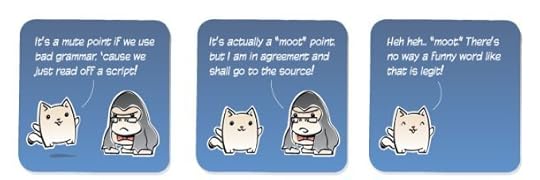

It is a moot point.  Cobuild recognizes it, but Collins, Macquarie and Merriam-Webster do not. Nor is it to be found in most dictionaries for learners of English, such as Cambridge, Macmillan, and the Oxford Advanced Learner���s. This suggests to me the possibility that, whereas the Cobuild editors acknowledged the weight of usage that is tending to legitimize what many people would still consider a mistake, the editors of dictionaries for learners prefer to discourage students from muddling up the two words. (It is also worth pointing out, incidentally, that the WordPress spellchecker flags diffuse ire and diffuse tension in this blog, and asks if I meant defuse.)

Cobuild recognizes it, but Collins, Macquarie and Merriam-Webster do not. Nor is it to be found in most dictionaries for learners of English, such as Cambridge, Macmillan, and the Oxford Advanced Learner���s. This suggests to me the possibility that, whereas the Cobuild editors acknowledged the weight of usage that is tending to legitimize what many people would still consider a mistake, the editors of dictionaries for learners prefer to discourage students from muddling up the two words. (It is also worth pointing out, incidentally, that the WordPress spellchecker flags diffuse ire and diffuse tension in this blog, and asks if I meant defuse.)

diffuse=defuse? Definition

Cobuild defines the contentious use of diffuse as follows:

“To diffuse a feeling, especially an undesirable one, means to cause it to weaken and lose its power to affect people”: The arrival of letters from the Pope did nothing to diffuse the tension.

The Oxford Online Dictionary does not include the meaning in its definition of diffuse;��instead it has a usage note:

“Diffuse means, broadly, ���disperse���, while the non-literal meaning of defuse is ���reduce the danger or tension in���. Thus sentences such as Cooper successfully diffused the situation are regarded as incorrect, while Cooper successfully defused the situation would be correct. However, such uses of diffuse are widespread, and can make sense: the image in, for example, “only peaceful dialogue between the two countries could diffuse tension” is not of making a bomb safe but of reducing something dangerous to particles and dispersing them harmlessly.

In two minds?

I find myself considerably (if one can be, linguistically speaking) in (or of, in the US) two minds. On the one hand, since this form is especially common in newspapers and transcripts, I suspect that urgent deadlines are often responsible, not to mention a certain amount of journalistic sloppiness. If I���m being over-literal, to my mind diffuse = “to spread”, and therefore diffusing tension spreads it rather than dissipating it.

A legitimate extension of meaning?

However, “spreading” is not the only meaning of to diffuse, and it is here that its physical meaning of “dispersing” light comes into play. Light that is diffused is made softer and less intense,��so I suppose that diffusing ��tension disperses it and thereby renders it less potent. I follow the logic of the Oxford editor’s argument, even though it still reads like special pleading to this old fuddy-duddy��(what a wonderful word that is!).

It also worth noting that both Cobuild and the Oxford note reproduced above have the same noun object collocate: tension.

So, I can see that there may well be a shift in collocational primings going on. In other words, more and more people are psychologically primed by their experience of the word diffuse to associate it with the semantic set of tension, crisis, etc, and to associate that set withdiffuse rather than defuse.

However, that collocational shift still raises problems for me. If diffuse is “correct” when used metaphorically, and in specific collocations, e.g. tension / row / controversy / crisis, why would it not be “correct” ��when applied literally (i.e. ?he diffused the device). But, even though diffuse turns up several times��with��bomb��and words in that set, it still feels completely wrong, at least to me.

Conclusions

There seem to me to be three ways of looking at this issue in “correct usage” terms:

At the strict, i.e. “prescriptive”, end of the spectrum, the only correct verb for the contexts discussed above is defuse.

At the other, i.e. “descriptive”,��end, one could take the view that diffuse is correct in all collocations that match those of defuse, i.e. including its literal use with bombs, etc. Though that use��must, surely, have started out as a homophone mistake, we accept that it is now part of standard usage, and therefore applicable in all circumstances.

We adopt a sort of Buddhist “middle way” approach and say that the two words are synonyms in some contexts, but not in others. Thus diffuse tension would be correct, but diffuse a bomb would not. There is nothing linguistically perverse about this, since synonymy operates with meanings, not words, and therefore works with some collocates but not others: a tax bill can be large or hefty, a building can only be large. However, this “middle way” would probably lead to a lot of borderline cases.

Further examples, facts & figures

In the OEC, these two lemmas do not differ much in frequency: they occur just over twice in every million words of text (compared to, say, “big”, which occurs nearly 400 times per million).

Their collocations overlap very little: apart from noun objects, as shown below, the adverb quickly and the verbs try and attempt.

There are eight noun objects with which they both collocate. They are listed in descending order, according to the ratio of occurrences of defuse to diffuse: situation, anger, confrontation, standoff, tension, row, crisis, bomb. The ratios range from just under 3:1 for situation to nearly 12:1 for bomb. In other words, for the most literal meaning, diffuse encroaches far less on defuse than it does with less literal meanings.

In absolute rank order as collocates of diffuse, the above nouns are: situation, tension, crisis, bomb, anger, row, confrontation, standoff.

Nevertheless, the dispute over the islands will continue to cause political and economic headaches for China and Japan, with neither acting to defuse the tensions���Business Insider, 2013;

Yet the frenzied days and sleepless nights seem to have averted a major embarrassment for the administration and defused a crisis that threatened to upend relations between the two countries���NYT, 2012;

The Scott report is a time-bomb stealthy politicians and officials are trying to diffuse���Guardian, 1995;

Meanwhile, the European Union is trying to diffuse the controversy by calling for a voluntary media code of conduct.���CNN transcripts, 2006.

Filed under: Advice for writers, Confusable words, Dictionaries & Lexicography, Grammar, Meaning of words, Writing Skills Tagged: 20 confusable words